Longitudinal associations of dietary fiber and its source with 48-week weight loss maintenance, cardiometabolic risk factors and glycemic status under metformin or acarbose treatment: a secondary analysis of the March randomized trial

Introduction

The global prevalence of diabetes has risen sharply, becoming a worldwide public health crisis. The 10th Edition of the International Diabetes Federation report in 2021 estimated that 537 million people aged 20–79 live with diabetes, with 90% of them diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [1]. T2DM, a systemic metabolic disease characterized by insulin resistance, impaired glucose tolerance, persistent hyperglycemia, and hyperinsulinemia, is closely related to multiple comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease (CVD). Without intervention, the number of cases is expected to continue increasing and may exceed 642 million by 2040 [2]. This occurrence will place a huge burden on numerous countries and regions, especially within Asian low- and middle-income countries as a result of rapid socioeconomic development, an upsurge in sedentary lifestyles, and overnutrition [3, 4].

Therapeutic strategies aimed at managing T2DM and preventing comorbidities need to include not only pharmaceutical interventions but also the management of modifiable factors, such as dietary habits, which influence both glycemic control and T2DM-related complications [5, 6]. Resultantly, dietary modification and glucose-lowering drug treatment have become the mainstay of therapy for T2DM [7]. Both treatment approaches act in synergy to achieve the desired therapeutic outcomes. Therefore, there is an urgent need to identify efficacious dietary modifications to be integrated as part of pharmaceutical interventions for patients with T2DM.

To our knowledge, most previous epidemiological studies or clinical trials have only evaluated pharmaceutical interventions or dietary intakes as separate factors without considering their synergistic or interactive effects. Given the current paucity of data in this area, the Metformin and Acarbose in Chinese as the initial Hypoglycemic treatment (MARCH) trial [8] became the first trial to investigate the influence of dietary factors on glycemic control under antidiabetic therapy. Our previous studies have evaluated whether the effects of acarbose and metformin on glycemic control and cardiometabolic risk factors were influenced by dietary intakes of macronutrients [9]. We observed that high carbohydrate intake was significantly and independently associated with higher body mass index (BMI), HbA1c, postprandial plasma glucose (PPG), and area under the curve (AUC) for serum insulin, suggesting that adhering to carbohydrate diet restrictions conferred additional benefits of weight loss and glycemic control. Nevertheless, increasing evidence suggests that the quality of dietary carbohydrates (with a preference for high-fiber and optimal fiber proportion of total carbohydrate intake) is a stronger determinant of the effects of diet on glycemic control and weight maintenance than the amount of carbohydrates in the diet [10]. In this context, dietary fibers hold immense promise as a valuable nutrient for the prevention and management of T2DM.

Reports from epidemiology and clinical intervention trials have indicated that increased consumption of dietary fiber, particularly among individuals with suboptimal intakes, is an effective strategy for alleviating T2DM [11]. A major challenge in reviewing the evidence is the complexity of dietary fiber sources as well as their proportion within the total carbohydrate intake, potentially providing different health benefits owing to these highly diversified fibers that vary in terms of structure and physicochemical properties [12, 13].

Metformin is the first-line treatment option for T2DM. The effects of metformin on glucose homeostasis are mediated through decreases in the intestinal absorption of glucose, inhibition of hepatic gluconeogenesis, and increase in peripheral glucose uptake by increasing insulin sensitivity, mediated by the activation of the AMP-activated protein kinase enzyme [14]. Acarbose is another most commonly prescribed drug for the management of T2DM. As an intestinal amylase inhibitor, acarbose can competitively inhibit amylases in the small intestine, thus effectively preventing increases in PPG after carbohydrate consumption. Notable, the bioavailability of orally administered drugs depends on absorption and plasma clearance, which can be affected by the presence of dietary fibers in the gastrointestinal tract [15]. Therefore, it is imperative to understand the individual responses of patients with T2DM to metformin or acarbose treatments, while also exploring the intricate interplay between these treatments and dietary fiber intake.

The MARCH trial was conducted to compare acarbose with metformin as the initial therapy in Chinese patients who had been newly diagnosed with T2DM. However, previous related investigations were predominantly limited to considering the treatment outcomes of single antidiabetic drugs, and no studies have explored dietary fiber-based combination regimens. Therefore, the current study aimed to investigate longitudinal and dose-dependent associations of dietary fiber from different sources and the proportion of fiber within the total carbohydrate intake. These associations were studied within 48 weeks. The outcome measures included weight loss and glycemic and cardiovascular status after metformin or acarbose treatment in newly diagnosed patients with T2DM in the MARCH trial.

Research design and methods

Study design

The MARCH trial was a 48-week, multicenter (11 clinical sites in China), randomized controlled clinical trial (RCT), which enrolled patients newly diagnosed with T2DM. The study was specifically designed to compare acarbose with metformin as the initial therapy in Chinese patients newly diagnosed with T2DM. The design and methods of the MARCH and details of the acarbose and metformin groups have been described in detail elsewhere [8], including the rationale for the chosen sample size, inclusion/exclusion criteria, the procedures for sample allocation to experimental groups, as well as the randomization and blinding protocols. Eligible MARCH participants were 30–70 years of age, diagnosed within the past 12 months with T2DM based on the 1999 WHO criteria, had a BMI (in kg/m2) of 19–30, had suboptimum glucose control (HbA1c between 7% and 10% and fasting plasma glucose [FPG] ≤ 11.1 mmol/L), and had not received any oral anti-diabetic drug or short-term (1 month) treatment 3 months before enrollment. Patients were assigned to 24 weeks of monotherapy with metformin or acarbose as the initial treatment, followed by a 24-week add-on therapy with insulin secretagogues if predetermined glucose targets were not achieved. The MARCH trial was registered at the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry as ChiCTR-TRC-08000231. All participants provided written informed consent and affirmed their willingness to engage in the study. The research protocol received approval from the ethics committee at each clinical site and was conducted in compliance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

Participants

The original RCT study screened 1099 patients and randomly allocated 788 to the two treatments. Four withdrew consent before drug intervention. 784 patients commenced study drug (393 metformin and 391 acarbose). In this secondary analysis, we further excluded 98 participants in the acarbose group and 107 in the metformin group with insufficient data of diet. Moreover, 10 participants in the acarbose group and 18 in the metformin group with implausible energy intake (<800 kcal/day or >6000 kcal/day for males; <600 kcal/day or >4000 kcal/day for females) were also excluded. Finally, a total of 551participants (286 in the acarbose group and 265 in the metformin group) were included in this study. The flowcharts of the selection process of the study population have been published in our previous study [9].

Dietary assessment

Dietary data were collected at baseline, week 24, and week 48 using a 24-h dietary recall method encompassing 15 food groups (rice, starch, whole grain products, potato/tuber, fruits, vegetables, eggs, milk and milk products, meat, fish, nuts, legumes, sugars, alcohol, and oils) commonly consumed. Study participants were requested to recall their usual frequency of consumption and the estimated portion size by making comparisons with the specified reference portion, as provided by clinical nutritionists and dietitians from the Department of Clinical Nutrition, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing. The quantities of each food group were converted into an average daily consumption. Chinese Food Composition Tables (Institute of Nutrition and Food Safety, China CDC. China Food Composition 2002. Beijing: Peking University Medical Press; 2002) were used to estimate energy and nutrient intake from all food groups. This study evaluated the intakes of total dietary, vegetable, fruit, and legume fibers, as well as the carbohydrate-to-total fiber ratio.

Clinical and biochemical measurements

Primary and secondary endpoint measures were assessed at baseline, week 24, and week 48. The clinical and biochemical measurements obtained at each of the study visits were as follows: (1) glucose metabolism, including HbA1c, FBG, and 2-h PPG (2hPPG); (2) insulin resistance, including fasting insulin, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), homeostatic model assessment of β-cell function (HOMA-β), early insulin secretion index (EISI, delta30-min insulin/delta30-min glucose ratio) [16], AUC of insulin, and whole-body insulin sensitivity index (WBISI, 10,000/square root of [fasting glucose × fasting insulin] × [mean glucose × mean insulin during OGTT]) [17]; (3) hormone secretion, including AUC of glucagon and glucagon-like peptide-1; (4) cardiometabolic risk factors related to obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, including BMI, serum levels of total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and triglycerides, as well as systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure (DBP). The BMI was calculated based on the measured heights and weights (kg/m2).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0 and R 3.5.1. Each dietary measure was expressed as the median and interquartile range because of the skewed distribution of data. Friedman’s two-way analysis of variance by ranks test was used to determine changes in dietary fiber intakes and its sources across three time points (baseline, week 24, and week 48) within two treatment groups. Whenever significance was established via the Friedman’s test at a significance level of P < 0.05, post hoc analyses using Bonferroni adjustment were performed to compare differences at each time point, as appropriate. Considering both metformin and acarbose could potentially interact with dietary fiber, we implemented stratified analyses to estimate the relationships between dietary fiber indices and treatment outcomes in each treatment group. Mixed effect linear and restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression analyses with repeated measurements were used to examine the longitudinal associations between dietary measures (treated as continuous variables) and all outcome variables in each group. Results from linear regression analyses were presented as regression coefficients (β) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). For the RCS regression, four knots were positioned at the 5th, 35th, 65th, and 95th percentiles of the independent variables. In both linear and RCS regression, adjustments were made for fixed effects such as the duration of intervention, duration of diabetes, sex, age, and total energy intake. Additionally, the center and individual were adjusted as random effects. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients who participated in this study. This study was approved by an ethics committee from each clinical site and was implemented in accordance with provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

Results

Changes in dietary measures

The flow of participants selection, participant characteristics comparison and different treatment effects have been previously demonstrated. Here, Table 1 summarized changes of total dietary fiber, vegetable fiber, fruit fiber, legume fiber, whole grain fiber as well as carbohydrate-to-fiber ratio during 48 weeks of intervention in two groups.

In the acarbose group, the Friedman’s analysis revealed a significant effect over time for legume fiber (P = 0.001) and the carbohydrate-to-fiber ratio (P = 0.002). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons revealed statistically significant alterations in both legume fiber and the carbohydrate-to-fiber ratio (adjusted P < 0.05). These findings indicate a substantial reduction in legume fiber intake at week 48 compared to week 24, as well as an elevated carbohydrate-to-fiber ratio at week 48 compared to week 24.

In the metformin group, fruit (P = 0.013) and vegetable fiber (P = 0.002) intakes, as well as the carbohydrate-to-fiber ratio (P = 0.003) were significantly different at the three time points. Notably, vegetable fiber intake was significantly decreased at week 24, and the carbohydrate-to-fiber ratio was significantly elevated at week 48 (adjusted P < 0.05). However, the post hoc analysis failed to establish significance after the Bonferroni correction for fruit fiber.

Longitudinal associations between dietary measures and clinical outcomes

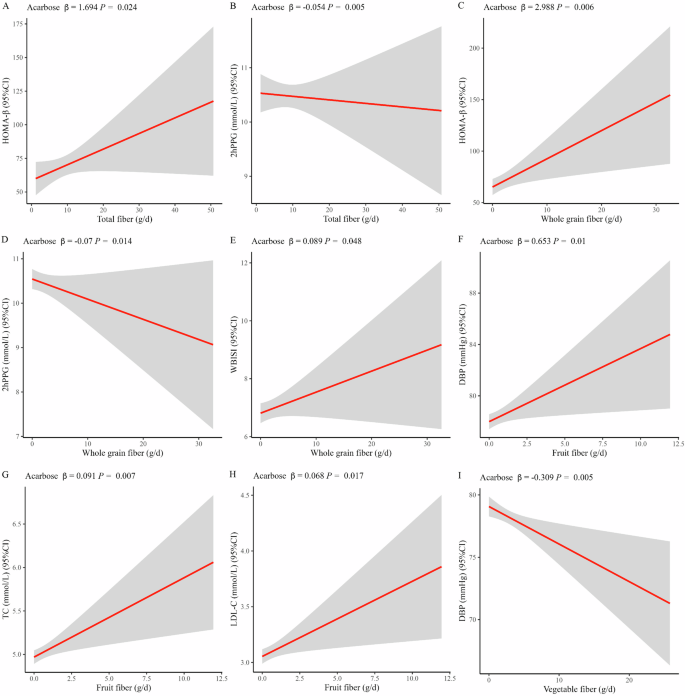

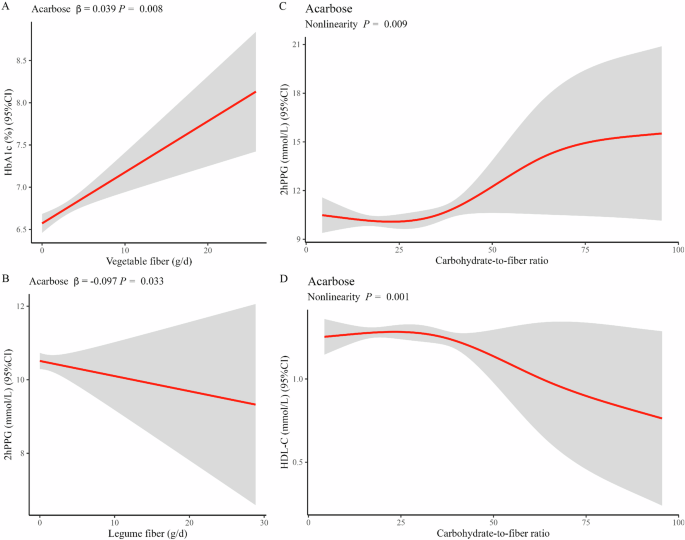

In the acarbose group, the mixed-effects linear models revealed significant associations. A higher intake of total fiber was positively associated with improved β-cell function and postprandial glycemic control, as indicated by a positive association with HOMA-β (β = 1.694, P = 0.024, Fig. 1A) and a negative association with 2hPPG levels (β = −0.054, P = 0.005, Fig. 1B). A similar association pattern was observed for whole grain fiber intake, where higher consumption correlated positively with enhanced HOMA-β (β = 2.988, P = 0.006, Fig. 1C) and reduced 2hPPG levels (β = −0.070, P = 0.014, Fig. 1D). Moreover, a higher intake of whole grain fiber was associated with improved insulin sensitivity, as indicated by positive associations with WBISI (β = 0.089, P = 0.048, Fig. 1E). However, there were only positive correlations between higher fruit fiber intake and DBP (β = 0.653, P = 0.010, Fig. 1F), TC (β = 0.091, P = 0.007, Fig. 1G), and LDL-C (β = 0.068, P = 0.017, Fig. 1H) levels, seemingly contributing to a higher risk of cardiovascular complications. Higher intake of vegetable fiber reduced cardiovascular risk, as indicated by a negative association with DBP (β = −0.309, P = 0.005, Fig. 1I). However, higher vegetable intake had an unfavorable impact on glycemic control, as indicated by a positive association with HbA1c (β = 0.039, P = 0.008, Fig. 2A). Higher intake of legume fiber may also improve postprandial glycemic control, as indicated by a negative association with 2hPPG levels (β = −0.097, P = 0.033, Fig. 2B). In addition, non-linear and dose-response associations were investigated. In the RCS analysis, significant associations were observed between the carbohydrate-to-fiber ratio and two outcome measures: 2hPPG (P for non-linear = 0.009, Fig. 2C) and HDL-C (P for non-linear = 0.001, Fig. 2D). There was an S-shaped association between the carbohydrate-to-fiber ratio and 2hPPG levels, showing a slight decrease until around 25, followed by a substantial increase from 25 to 75, and subsequently maintaining a relatively flat pattern. For the HDL-C levels, the association curve showed a slight increase until around 25 of the carbohydrate-to-fiber ratio, followed by a substantial decrease.

Linear associations of total fiber with HOMA-β (A) and 2hPPG (B); whole grain fiber with HOMA-β (C), 2hPPG (D), and WBISI (E); fruit fiber with DBP (F), TC (G) and LDL-C (H) and vegetable fiber with DBP (I) in acarbose group. Abbreviations: DBP diastolic blood pressure, TC total cholesterol, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, 2hPPG 2-h postprandial plasma glucose, HOMA-β homeostasis model assessment of β cell function, WBISI whole body insulin sensitivity index. For linear regression, adjustments were made for fixed effects such as the duration of intervention, duration of diabetes, sex, age, and total energy intake. Additionally, the center and individual were adjusted as random effects.

Linear associations of vegetable fiber with HbA1c (A); legume fiber with 2hPPG (B); non-linear associations of carbohydrate-to-fiber ratio with 2hPPG (C) and HDL-C (D) in acarbose group. Abbreviations HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; 2hPPG, 2-h postprandial plasma glucose. For both linear and RCS regression, adjustments were made for fixed effects such as the duration of intervention, duration of diabetes, sex, age, and total energy intake. Additionally, the center and individual were adjusted as random effects.

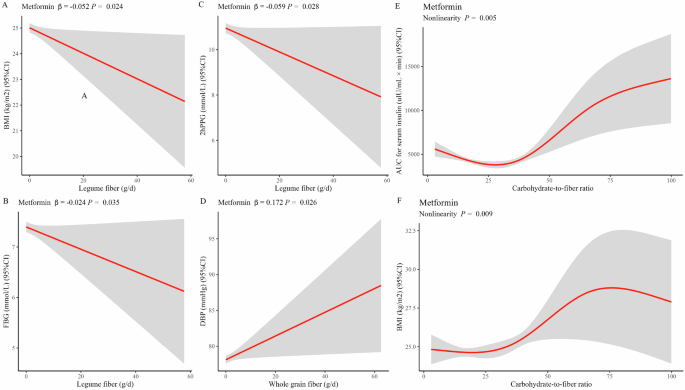

Significant linear associations between dietary fibers and clinical outcomes in the metformin group were much less than that in the acarbose group. Notably, a higher intake of legume fiber played a more beneficial role following metformin treatment. This beneficial effect was observed as weight loss and favorable glycemic control, which were demonstrated by consistently negative associations with BMI (β = −0.052, P = 0.024, Fig. 3A), FBG (β = −0.024, P = 0.035, Fig. 3B), and 2hPPG (β = −0.059, P = 0.028, Fig. 3C). Unexpectedly, a positive association was observed between higher whole grain fiber intake and higher DBP (β = 0.172, P = 0.026, Fig. 3D) in the metformin group. This association suggests whole grain fiber increases cardiovascular risk. Moreover, in the RCS analysis, the carbohydrate-to-fiber ratio was still the only dietary measure that had non-linear associations with the AUC for serum insulin (P for non-linear = 0.005, Fig. 3E) and BMI (P for non-linear =0.009, Fig. 3F). Both clinical measures demonstrated a similar S-shaped curve, observes as a slight decrease until around 25, followed by a substantial increase from 25 to 75. However, a divergent trend emerged subsequently, as evidenced by a continuous increase in AUC for serum insulin and a sharp decrease in BMI.

Linear associations of legume fiber with BMI (A), FBG (B) and 2hPPG (C); whole grain fiber with DBP (D); non-linear associations of carbohydrate-to-fiber ratio with AUC for serum insulin (E) and BMI (F) in metformin group. Abbreviations: BMI body mass index, DBP diastolic blood pressure, TFBG fasting blood glucose, 2hPPG 2-h postprandial plasma glucose, AUC area under the curve. For both linear and RCS regression, adjustments were made for fixed effects such as the duration of intervention, duration of diabetes, sex, age, and total energy intake. Additionally, the center and individual were adjusted as random effects.

Discussion

In this secondary analysis of MARCH study, we observed how different sources of fiber influence treatment outcomes following certain oral antidiabetic drug regimens, suggesting that optimizing drug/dietary fiber combinations may provide greater success than drug targets considered in isolation.

In this clinical trial, high intakes of both total fiber and whole grain fiber were positively associated with improved β‐cell function, insulin sensitivity, and postprandial glycemic control in the acarbose group. Additionally, a high intake of legume fiber was associated with favorable glycemic control in both the acarbose and metformin groups, suggesting that whole grain and legume fibers exert protective effects in T2DM. Several meta-analyses have confirmed this protective role of dietary fibers in T2DM. One meta-analysis of 15 RCTs concluded that dietary fiber intake significantly improves FBG and HbA1c [18]. Another meta-analysis also concluded that the intake of whole grains improves glycemic markers such as FBG, Hb1Ac, and insulin sensitivity (HOMA-IR) [19]. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain these effects, including both direct effects of fiber on gut physiology and indirect effects stemming from alterations in the gut microbiome.

Dietary fiber can be classified as soluble or insoluble based on its solubility in water. Insoluble fiber is the most abundant type of fiber in legumes and is highly dominant in whole grains. Dietary fibers, especially insoluble fibers, mix with intragastric fluids and form a sticky digesta that moves slowly through the gut. The slow passage of the sticky digesta through the gut reduces the absorption rate of nutrients such as glucose, thereby slowing PPG and insulin upsurge. Additionally, the slow passage results in the flattening of the glycemic curve following carbohydrate intake by prolonging the intestinal transit time [20].

In addition to the hypoglycemic effects, a high intake of legume fiber may play a beneficial role following metformin treatment due to positive associations with weight loss. Jovanovski et al. [21] performed a meta-analysis of 62 RCTs with durations ≥4 weeks and observed a similar reduction in body weight and BMI. Mechanistically, low energy intakes contribute to energy balance for weight maintenance. A high fiber intake could reduce the energy density of foods, slow down the rate of food consumption, and initiate satiety by stimulating the release of gut hormones. This cascade ultimately results in a reduction in the number of calories ingested, facilitating weight maintenance [22]. The feeling of satiation can be induced by both soluble and insoluble fibers. Notably, soluble fibers primarily prolong satiety. Soluble fibers include several types of polysaccharides, including hemicellulose, which is abundant in foods such as legumes [23]. European guidelines for the management of T1DM and T2DM have emphasized the benefits of soluble forms of dietary fiber from legumes [24]. This emphasis on dietary fiber sources may be more appropriate for Chinese patients with T2DM who are receiving acarbose or metformin treatment.

Dietary fiber has also been shown to indirectly improve metabolic health and weight loss by modulating the gut microbiome. Humans live in symbiosis with trillions of microbes, most of which are found in the gastrointestinal tract. Prone to fermentation by gut microbes, dietary fibers exert pleiotropic physiological effects on the composition and functionality of the gut microbiota. These effects include nurturing the growth of selected beneficial gut microbes, altering the production of hormones and cytokines, and promoting the fermentation of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) [25]. SCFAs play an important role in maintaining human hosts’ metabolic health [26]. Similar to our results, ref. [27] demonstrated that supplementation with fiber-rich pea, a kind of legume fiber, improves glycemia by inducing changes to the gut microbiota composition and altering the serum SCFA profile in glucose-intolerant rats. Additionally, Kovatcheva-Datchary et al. [28] reported that the gut microbiota becomes enriched in Prevotella copri following a meal of barley kernel-based bread, a kind of whole grain fiber. Both of these studies indicate legume fiber and whole grain fiber-mediated gut microbiota modulation plays a major role in improving glucose metabolism. Moreover, the gut microbiota plays crucial roles in the modulation of drug action. Mounting evidence suggests that the therapeutic and synergistic effects of oral glucose-lowering drugs, such as acarbose or metformin, are mediated, in part, through diverging or overlapping effects on gut microbial composition or functional capacity in individuals with T2DM [29, 30]. Furthermore, the gut microbiota can influence patients’ response to specific oral glucose-lowering drugs by altering the drug’s bioactivity, bioavailability, or toxicity. For example, acarbose could inhibit host glucoamylases to prevent fiber-rich food digestion in the gut, thus reducing PPG levels. Consequently, there is an increase in dietary fiber in the gut, which subsequently serves as food for the gut bacterial community. Other studies investigating metformin-microbiota interactions revealed that metformin can promote an increase in the abundance of mucin-degrading bacteria (e.g., Enterobacteriales and Akkermansia muciniphila). Additionally, metformin has been demonstrated to enhance the production of SCFAs [31]. These effects could work in tandem with dietary fibers, promoting the growth of a multitude of beneficial bacterial genera to yield more pronounced additive or synergetic effects on metabolic health. Pre-clinical animal models [29, 32, 33] or clinical trials [34] have indicated that the addition of dietary fiber to metformin or acarbose monotherapy improves glucose and lipid metabolism. As therapy becomes individualized, the interplay between nutrition, medication, and gut microbiota needs to be taken into consideration to maximize therapeutic benefits and prevent unwanted side effects. However, their interaction is complex, seemingly involving a wide range of undiscovered gut microbes, enzymes, and metabolites. In addition, as research findings accumulate, certain controversies have arisen, occasionally presenting conflicting outcomes [35]. For example, a recent study analyzing the microbiome revealed a positive association between butyrate production and insulin response in β-cells. Conversely, an increase in fecal propionate levels was found to be associated with the incidence of T2DM [36]. Since the current study did not perform gut microbiota sequencing, further investigations are needed to elucidate whether the synergistic benefits of acarbose or metformin and specific dietary fiber are associated with gut microbiota composition and microbiota-derived metabolites. This investigation could provide insight into the potential role of the gut microbiome as a target for improving the therapeutic efficacy of T2DM treatment options.

Notably, positive associations were observed between fruit fiber intake and DBP, TC, and LDL-C levels in the acarbose group. These associations indicated a higher risk of dyslipidemia and cardiovascular complications. Contrary to that, the beneficial health effects of fruit are well-documented. Potential mechanisms for lipid reduction associated with fruit consumption—such as the low energy density of fruit, the production of satiety factors, and the influence of micronutrients on metabolic pathways—exhibit indirect correlations with dyslipidemia-related diseases and fruit intake. However, given the presence of simple sugars in fruit (glucose, fructose, sucrose, etc.), which are well-known contributory factors to dyslipidemia-related diseases, it is reasonable to expect that their consumption should contribute to dyslipidemia rather than metabolic improvement [37]. The EPIC-InterAct study, a nested case-cohort study involving 26,088 adult participants, indicated statistically significant reductions in T2DM risk associated with total fiber, vegetable fiber, and cereal fiber intake but not fruit fiber intake [38]. In particular, children and adolescent might be more sugar-sensitive than adults. An investigation involving 15,000 American children indicated that weight gain in preadolescent and adolescent age groups could be attributed to the consumption of a fruit-rich diet, provided that the total caloric intake was not adjusted to meet their specific nutritional requirements [39]. However, another national cross-sectional study in China including 14,755 children and adolescents aged 5–19 years supports the beneficial health effects of regular, moderate fruit intake on improving lipid profiles in children and adolescents [40]. The contradictory characteristics of fruit in relation to lipid management have prompted us to investigate the specific contributions of various fruit types to lipid regulation. Additionally, the anti-dyslipidemia properties of known fruit constituents require further validation. Consequently, future research should prioritize the identification of anti-dyslipidemia components in fruit as an urgent and significant objective, not only to elucidate the scientific mechanisms underlying dyslipidemia but also to develop strategies for controlling dyslipidemia through optimal fruit consumption.

In addition, a notable observation is the conflicting impact of high vegetable fiber intake. On one hand, it was associated with reduced cardiovascular risk, evident from the negative correlation with DBP. On the other hand, it had adverse effects on glycemic control, as indicated by a positive correlation with HbA1c. Moreover, a positive association was observed between whole grain fiber intake and DBP within the metformin group, suggesting that whole grain fiber intake enhances cardiovascular risk. Contrary to this observation, Du et al. [41] reported that total dietary fiber, vegetable/fruit fiber, and grain fiber are negatively correlated with DBP in middle-aged women. This observation could be attributed to differences in population, food consumption patterns, and sources of dietary fiber. Moreover, the level of dietary fiber intake in our study population was quite low, possibly below the amounts associated with considerable health benefits (corresponding to the current recommended about 25–30 g of dietary fiber per day [42]). This could account for the conflicting associations. Therefore, a more comprehensive understanding of these associations necessitates further studies that can delve into these dynamics in greater detail.

As a component of dietary carbohydrates, the ratio of dietary fiber to total carbohydrate intake is also important for metabolic benefits. Such benefits are often observed when a high proportion of total carbohydrates is derived from foods rich in dietary fiber. In our study, we observed inverse S-shaped associations between the carbohydrate-to-fiber ratio and 2hPPG as well as HDL-C within the acarbose group. Similarly, S-shaped associations were observed between the carbohydrate-to-fiber ratio and AUC for serum insulin as well as BMI within the metformin group. These findings collectively suggest that a diet characterized by a high carbohydrate and low fiber content is associated with poor glycemic control and low HDL-C levels following acarbose treatment. Conversely, such a diet is associated with high insulin sensitivity and weight loss following metformin treatment when compared to a diet characterized by a low carbohydrate and high fiber diet. Consistent with our results, the American Heart Association recommends at least 1.1 g of fiber per 10 g of carbohydrate for protection against CVD [43]. Moreover, Fontanelli et al. [44] reported that grain consumption meeting the <10:1 ratio (1 g of fiber per 10 g of carbohydrate) is associated with high nutritional quality and low cardiometabolic risk. However, we demonstrated the dose-response effect in terms of the relationships between carbohydrate-to-fiber ratio and clinical outcomes following intensive drug therapy in patients with T2DM. We observed that the relationships were not linear, suggesting that the quality of carbohydrates appears to play a more critical role in metabolic health rather than total carbohydrate as a percentage of dietary energy. Given that dietary carbohydrates constitute a heterogeneous class of nutrients, carbohydrate quality index (CQI) was developed as a novel index to offer a more comprehensive assessment of dietary carbohydrate quality, by taking dietary total fiber consumption, dietary glycemic index, whole grains-to-total grains ratio, and the ratio of solid carbohydrates to total carbohydrates into account [45]. Several studies have demonstrated a positive association between CQI and metabolic risk factors; however, the current evidence remains insufficient to draw definitive conclusions [46]. To comprehensively elucidate this association, additional observational and interventional research is required.

The effective management of T2DM requires an integrated approach that takes patient characteristics and available pharmacological options into consideration. It is common to use a combination of medications to optimize treatment outcomes in T2DM. The influence that lifestyle modifications, specifically dietary factors, might have on the action of those oral antidiabetic medications has received much less attention. However, some pioneering clinical trials and animal studies [13, 47] have demonstrated that the coadministration of certain types of fiber with certain drugs could reduce hyperglycemia more than monotherapy of the drug. These observations may be attributed to the interaction between the fibers and the orally administered drugs, potentially modifying the pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic profile of the drug. These interactions could involve the enhancement of the viscosity of gastrointestinal contents, trapping the drugs inside the viscous gel formed, increasing the amount of absorbed drug, and slowing the rate of absorption [15].

Several limitations in our study need to be acknowledged. First, the assessment of dietary fiber consumption was based on a 24-h recall, a method prone to misreporting and probably not representative of the typical diet. Although this method has provided valuable dietary results for several epidemiologic investigations, a more extensive dietary intake data collection would likely have reduced measurement errors. Second, as the current study only included 551 Chinese patients newly diagnosed with T2DM, our findings should be interpreted with caution when generalizing to other populations. Last but not least, the further exclusion of the original participants according to the diet record may bring some concerns about selection bias and further observation studies or clinical trials need to be conducted with full consideration of both drug treatment and dietary consumption.

In conclusion, we demonstrated the additional metabolic benefits of combining metformin or acarbose with dietary fibers from different sources in newly diagnosed patients with T2DM. We observed that consuming high amounts of total fiber and whole grain fiber can positively affect β-cell function, insulin sensitivity, and postprandial glycemic control in those T2DM taking acarbose. Moreover, in both acarbose and metformin groups, a high intake of legume fiber was associated with favorable glycemic control. Therefore, this suggests that whole grain and legume fibers can provide protective effects on glycemic control in newly diagnosed patients with T2DM. In addition, the drugs could act synergistically with certain types of fibers to improve glycemic control, insulin sensitivity, and weight loss. Thus, we predict that optimizing drug/dietary fiber combinations may provide greater success than monotherapy with antidiabetic agents, considering the significant interactions between the dietary fibers and the drugs.

Responses