Longitudinal trends in schizophrenia among older adults: a 12-year analysis of prevalence and healthcare utilization in South Korea

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a common, severe, heterogeneous mental disorder characterized by a very diverse array of positive symptoms (such as delusions and hallucinations), negative symptoms (including anhedonia and social withdrawal), and cognitive dysfunctions1. The global lifetime prevalence is 7.2 per 1,000 individuals2. Of all schizophrenia patients, 30–40% are resistant to antipsychotic treatment3. Persistent symptoms often impair social and occupational functioning, with long-lasting (and devastating) effects on patients and their caregivers4.

The global demographic landscape is shifting toward older age; life expectancy is increasing5, particularly in East Asian countries (where the shift is especially rapid)6. Such a trend is also apparent in South Korea. In 2021, 32.0% of the population were aged ≥50 years and 19.3% ≥65 years7. It is projected that South Korea will soon lead the world in terms of life expectancy. The probability that life expectancy at birth for South Korean women will exceed 86.7 years by 2030 is 90%, and the probability that men will live for >80 years 95%8. Therefore, the number and proportion of older patients with schizophrenia will rise significantly.

As a population ages, the physical and mental health of older adults require particular attention. Aging diminishes physiological reserves, in turn weakening the homeostatic mechanisms and increasing vulnerability to disease9. The physiological changes render older individuals at greater risk of medication side-effects than younger adults10. All antipsychotics bear a “black box warning”; the mortality risk increases when such drugs are prescribed for older patients with dementia-related psychosis11. Therefore, older adults with schizophrenia require careful and specialized care12. Such adults have not been extensively researched in the past13, but recent international studies have increasingly emphasized the importance of focusing on such populations, and have described the unique challenges they pose and their needs. One large-scale study in the United States revealed a significantly increased risk of premature mortality, particularly from cardiovascular disease, among adults with schizophrenia14. A French group reported that both the general psychopathology and negative symptoms significantly compromised the quality-of-life in older adults with schizophrenia spectrum disorder, and emphasized the need for targeted interventions15. A Japanese work found that community-based support was essential if older schizophrenia patients were to age successfully16.

The global trends described above underscore the critical need for similar research in South Korea, particularly given the rapidly aging population. However, previous epidemiological studies on schizophrenia patients of South Korea17,18, have not fully addressed age-related considerations. Similarly, reports from psychiatric hospitals did not pay adequate attention to age-related differences in healthcare utilization patterns and the lengths of hospital stays19,20. It is essential to examine comprehensively the schizophrenia prevalence in older South Korean adults, their healthcare utilization patterns, and their unique needs. Clinicians and researchers would then understand the unique requirements of this population, and develop targeted interventions improving their care.

We therefore analyzed changes in the schizophrenia prevalence among older adults, and their healthcare utilization patterns, over the past 12 years. We offer a comprehensive overview of how the proportion of older adults with schizophrenia has changed over time, and how their healthcare needs and utilization patterns differ from those of younger patients.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

This observational study used the Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) database of South Korea. This contains the details of all health insurance claims (medical benefits) processed for approximately 98% of the population; thus almost all South Koreans21. The data were anonymized, and the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital found that our study did not require review and that there was no need for informed patient consent (IRB document 2302-122-1408).

The data collection period, thus the recruitment period for this retrospective study, ran from January 1, 2007, to December 31, 2021. However, the actual study period was from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2021. This 12-year observation period was accompanied by a 3-year look-back period (2007-2009). The look-back period was implemented to ensure complete identification of eligible patients entering the cohort by allowing sufficient time to confirm diagnoses.

Participants

The study population were all South Koreans covered by the national health insurance system, who were otherwise receiving medical aid, or who were eligible for veterans’ benefits. We used claims data from 2007 to 2021 to establish a cohort of individuals with at least one schizophrenia diagnostic code (ICD-10 code F20). The inclusion criteria were schizophrenia as primary or secondary diagnosis in two or more outpatient visits, or one or more inpatient admissions; and at least one antipsychotic prescription. We excluded individuals who had a prescription for cognitive enhancers before or within 12 months after their first antipsychotic prescription. This avoided any potential misdiagnosis of dementia as schizophrenia.

Supplementary Table 1 is a full list of all antipsychotic drugs and cognitive enhancers considered in this study. All medications were identified by their Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) codes. South Korea assigns standard codes to all medical services and medical products. The electronic HIRA claim submissions use these codes22. To facilitate (potential) international comparisons, we also include the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) code for each medication. These were checked using the HIRA drug information service and were cross-referenced employing the ATC/DDD Index of the World Health Organization (WHO) Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology23.

Patient numbers and annual schizophrenia prevalence

The annual schizophrenia prevalence was the number of affected persons as a proportion of the total population. The number of subjects for each year of observation was defined as those with an initial diagnosis of schizophrenia during an outpatient visit before December 31 of the year, who also had at least one medical record after January 1 of the year, regardless of the visit type. The total population in each year of observation was that of the Korean Statistical Information Service (Supplementary Table 2).

We calculated both the overall schizophrenia prevalence and the prevalence by age. Recent research has highlighted the fact that schizophrenia is associated with accelerated aging, including a 10–25-year reduction in life expectancy, earlier admission to nursing homes, and more rapid cognitive decline compared to the general population24. Middle-aged schizophrenia patients (40–49 years) performed worse on age-sensitive cognitive tests than did healthy adults over 70 years of age25. The age used to define older schizophrenia patients is often lower than that for the general population. We therefore defined older schizophrenics as those aged ≥50 years, in line with recent literature suggesting that individuals with schizophrenia begin aging at between 50 and 55 years26. Accordingly, we performed subgroup analyses after adjustment of the subject numbers and schizophrenia prevalence by age; younger adults were aged 15–49 years and older adults were aged 50–99 years. We sought to capture potential differences in schizophrenia prevalence and healthcare utilization patterns between younger and older adults with consideration of the unique aging profile of schizophrenics.

Comorbidity burden assessment

We calculated the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) scores using the ICD-10 coding algorithm developed by Quan et al.27 to assess the physical comorbidity burden. We identified the relevant diagnostic codes from outpatient visits and hospitalizations during each year for each patient. The CCI score was determined annually for each patient to track changes in comorbidity burden over time. We compared the CCI scores between younger and older adults with schizophrenia to evaluate age-related differences in physical comorbidity burden, addressing a critical aspect of accelerated aging in this population.

Annual lengths of hospitalization and healthcare utilization patterns

We evaluated annual hospital admissions, length of hospitalizations, and the types of medical facility utilized. Hospitalizations were categorized into psychiatric and non-psychiatric. Psychiatric hospitalization was defined as hospitalization with a mental disorder (ICD-10 codes starting with F) as either the primary or secondary diagnosis, while non-psychiatric hospitalization was defined as hospitalization without a mental disorder diagnosis. The annual length of hospitalization was the sum of all hospital days. Healthcare facilities were categorized based on bed capacity as defined by the Korean National Health Insurance system: tertiary/general hospitals (>99 beds); hospitals (30–99 beds) and nursing homes; and clinics (<30 beds)28. Tertiary hospital status is designated by the Ministry of Health and Welfare when a general hospital meets specific criteria. Nursing homes, which are long-term care facilities, were grouped with hospitals in the present study. The annual utilization rate for each facility type was the proportion of subjects hospitalized at least once in such a facility of all subjects hospitalized that year.

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics included age, sex, and insurance type. Age was based on the last day of each year, and sex and insurance type by the latest claim record in each year. The descriptive statistics are frequencies and percentages. Linear regression models were used to assess changes in dependent variables over the years within groups.

Given the hierarchical structure of our data with repeated measurements over time (2010–2021) and patients grouped by age and insurance type, we used linear mixed models (LMMs) to examine the time-point differences and patterns of change. LMMs were employed to explore differences in changes across subgroups in terms of patient numbers, the schizophrenia prevalence, the female proportion, the proportion of medical aid beneficiaries, and the utilization rates of different healthcare facilities; and to assess the effects of age group and insurance type on changes in hospitalization length and CCI scores over the years. The covariance structure for all LMM analyses was autoregressive (AR), considering the correlation between repeated measurements over time.

P-values < 0.05 derived via both linear regression and LMM analyses were considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted with the aid of SAS Enterprise ver. 7.1 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Numbers of patients and schizophrenia prevalence

Table 1 lists the demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects. Over the 12-year period from 2010 to 2021, 420,203 schizophrenia patients were identified, of whom 50.9% were female. Of all patients, 63.8% were covered by health insurance, 36.1% were medical aid recipients, and 0.1% were veterans. Table 1 shows the year-wise distribution of initial schizophrenia diagnoses over the years, and the percentages of females; the sex distribution was quite stable over time.

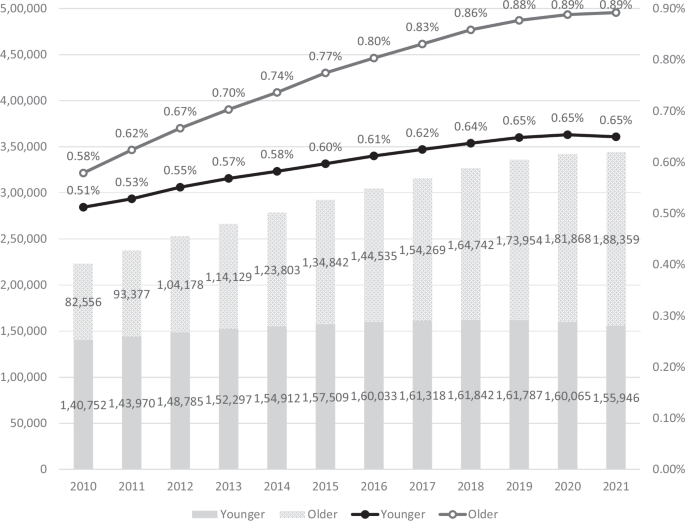

Table 2 lists the numbers of patients, schizophrenia prevalence, and the proportions of medical aid beneficiaries by age group over the years, and the results of linear regression used to analyze changes over the years in each dependent variable for the entire sample, and older and younger adults. The number of patients and the schizophrenia prevalence significantly increased over the years in both age groups, as revealed by linear regression (all p < 0.001). Of younger adults, the number of patients increased from 140,752 in 2010 to 155,946 in 2021; the prevalence rose from 0.51% to 0.65%. The increase was more pronounced in older adults; patient numbers grew from 82,556 to 188,359 and the prevalence increased from 0.58% to 0.89% over the same period. Additionally, the proportion of older schizophrenia patients among all patients significantly increased over the study period (p < 0.001), rising from 37.0% in 2010 to 54.7% in 2021; the age distribution of schizophrenia patients shifted substantially. Figure 1 illustrates these trends, highlighting the differences in the rates of increase between older and younger adults. The LMM data in Table 4 show that the rises in both patient numbers (p < 0.001) and schizophrenia prevalence (p = 0.002) were significantly faster in older than in younger adults.

The annual numbers of schizophrenia patients and the annual schizophrenia prevalence are presented as a bar plot and a line graph respectively. Dark gray bars: numbers of younger patients; light gray bars: numbers of older patients. Black line: prevalence among younger patients; gray line: prevalence among older patients. All subgroups exhibited significant increases in both numbers and prevalence over the years. The linear mixed model (LMM) confirmed that, over the years, the older group exhibited significantly higher increases in both numbers (B = 8.24E + 3, p < 0.001) and prevalence (B = 1.60E−4, p = 0.002) than did the younger group.

Proportion of medical aid beneficiaries

The proportion of medical aid beneficiaries varied over the years between age groups (Tables 2 and 3). A significant decrease from 34.7% to 24.5% (p < 0.001) was observed in younger adults. However, in older adults, the proportion fluctuated little, with the initial (2010) and final (2021) years of the study at 44.9%, and no significant trend was observed over the years (p = 0.529). Table 4 shows a significant difference in the change in the proportion of medical aid beneficiaries between the age groups (p = 0.001), suggesting that older adults with schizophrenia consistently remain beneficiaries compared to younger adults.

Supplementary Table 3 contains detailed information on subject distribution by insurance type (health insurance, medical aid, and veteran assistance) for each year from 2010 to 2021, and also the proportion of medical aid beneficiaries within each age group over the same period. This highlights the changes in insurance status across the different age categories.

Comorbidity burden

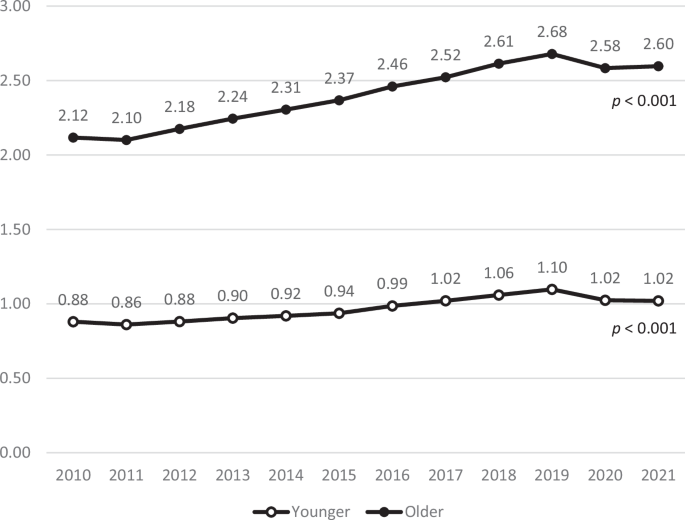

As shown in Fig. 2, the CCI scores in both age groups significantly increased (p < 0.001). The scores in older adults increased from 2.12 to 2.60, while those of younger adults increased from 0.88 to 1.02 during the same period. Notably, the older patient group consistently maintained higher CCI scores than the younger group. As shown in Table 5, there was a significant difference in the change in the CCI score between the age groups (p < 0.001), supporting this widening gap.

The annual average CCI score is presented as a line graph. Black line: CCI scores in older patients; gray line: CCI scores in younger patients. Both age groups showed steady increases in CCI scores over time, with the older group maintaining consistently higher values.

Annual lengths of hospitalization

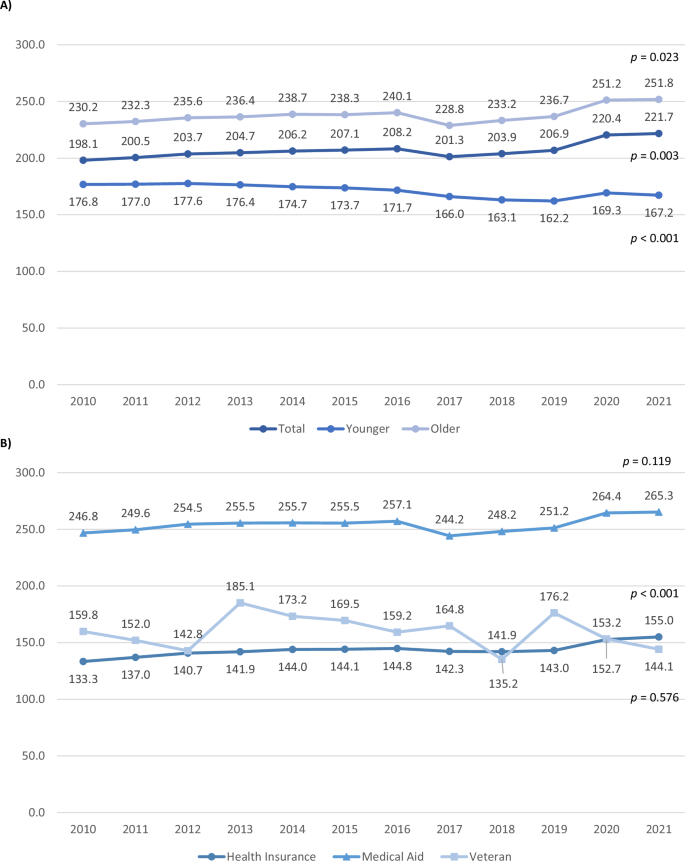

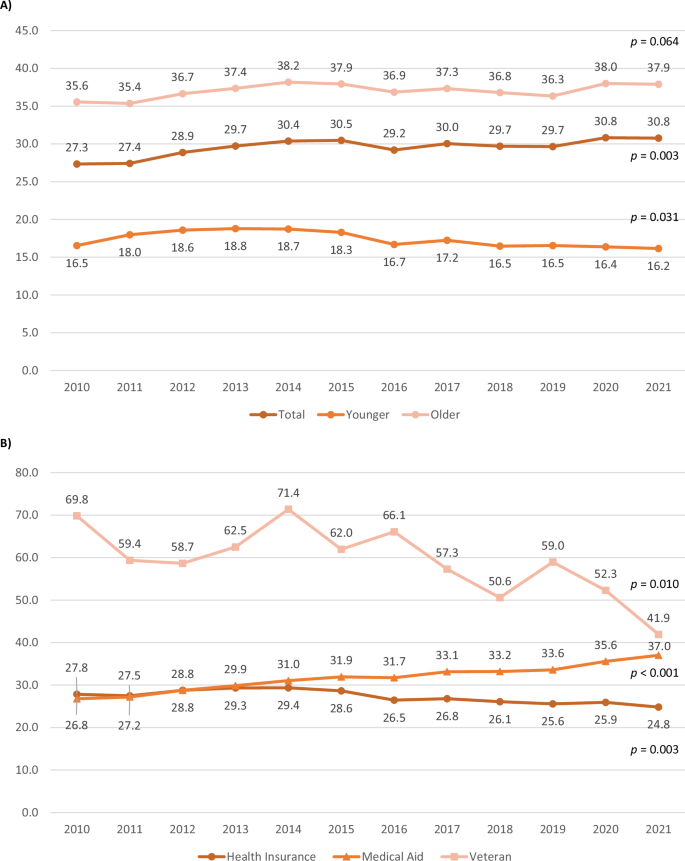

Figures 3 and 4 illustrate the annual average lengths of hospitalization by age group and insurance type, separated into psychiatric and non-psychiatric hospitalizations, respectively.

The annual average length of psychiatric hospitalization by age group and insurance type. A Age group. B Insurance type.

The annual average length of non-psychiatric hospitalization by age group and insurance type. A Age group. B Insurance type.

The overall hospitalization period for psychiatric hospitalizations increased over time, with divergent patterns between age groups: hospitalization significantly increased in older adults from 230.2 days to 251.8 days (p = 0.023), whereas it significantly decreased in younger adults (p < 0.001). Among insurance types, the health insurance group significantly increased from 133.3 days to 155.0 days (p < 0.001), while the medical aid group hospitalization days increased slightly but not significantly (p = 0.119) from 246.8 days to 265.3 days. The veteran group decreased from 159.8 days to 144.1 days with substantial year-to-year fluctuations, although not significant (p = 0.576). Notably, older adults and the medical aid group exhibited a sudden decrease in hospitalization duration between 2016 and 2017.

The overall hospitalization period increased over time (p = 0.003) for non-psychiatric hospitalization with older adults increasing from 35.6 days to 37.9 days and younger adults decreasing from 16.5 days to 16.2 days. The health insurance group significantly decreased from 27.8 days to 24.8 days (p = 0.003), while the medical aid group significantly increased from 26.8 days to 37.0 days (p < 0.001). The veteran group significantly decreased from 69.8 days to 41.9 days (p = 0.010), with substantial year-to-year fluctuations.

Table 6 lists the results of an LMM analysis that examined the effects of year, age group, and insurance type on the annual length of hospitalization for psychiatric and non-psychiatric cases.

Initially, older adults exhibited significantly longer psychiatric hospital stays than younger adults (B = 37.57, p < 0.001). The Year*Age group interaction revealed that older adults experienced a significantly more rapid increase in hospitalization length over time (p < 0.001), indicating a widening gap between age groups that is expected to continue. Compared to the medical aid group (reference), both health insurance and veteran groups initially had significantly shorter hospitalizations (B = −110.39 and −101.55, respectively, both p < 0.001). Over time, the gap between health insurance and medical aid groups narrowed (p < 0.001), while the veteran group did not change significantly (p = 0.962).

Initially, older adults also had significantly longer non-psychiatric hospital stays (B = 17.27, p < 0.001). The Year*Age group interaction indicated a similar widening gap between age groups over time (p < 0.001). Compared to the medical aid group, the health insurance and veteran groups initially had significantly longer hospitalizations (B = 2.85 and 35.40, respectively, both p < 0.001). Hospitalization length significantly decreased in the health insurance and veteran groups (B = −0.94 and −1.86, respectively, both p < 0.001), indicating a converging trend among insurance types.

These LMM results support the trends apparent in Fig. 3 for psychiatric and Fig. 4 for non-psychiatric hospitalizations, providing insights into the relative changes in hospitalization duration among different insurance types and age groups.

Healthcare utilization patterns

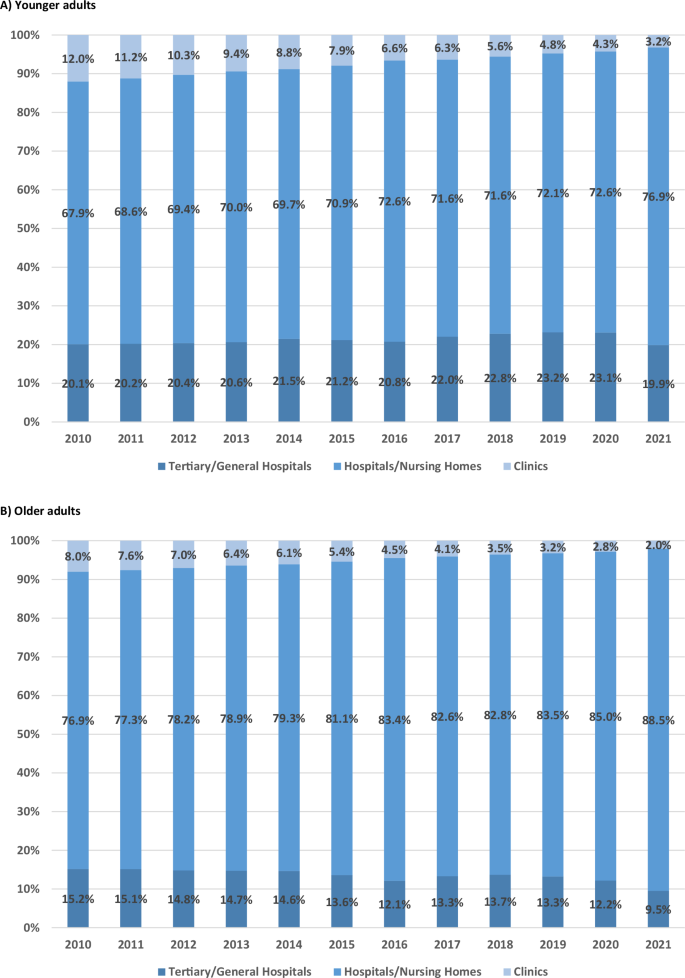

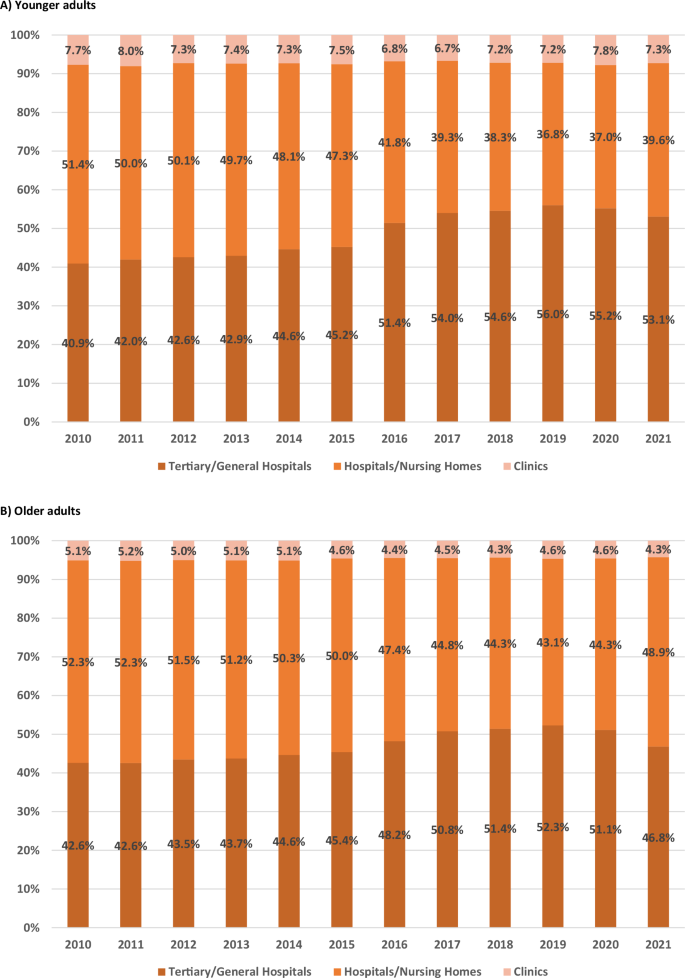

Figures 5 and 6 show the annual proportions of healthcare facilities used by older and younger adults, separated into psychiatric and non-psychiatric hospitalizations. The facilities were tertiary/general hospitals; hospitals/nursing homes; and, clinics. Significant changes in the utilization of healthcare facilities were apparent over time.

A Younger adults. B Older adults.

A Younger adults. B Older adults.

For psychiatric hospitalization, the proportion of tertiary/general hospital users significantly increased among younger adults from 2010 to 2020 (from 20.1% to 23.1%, p = 0.048), with a rate of 19.9% in 2021. The proportion of hospital/nursing home users significantly increased from 67.9% to 76.9% (p < 0.001), and the proportion of clinic users significantly decreased from 12.0% to 3.2% (p < 0.001). Among older adults, the proportion of tertiary/general hospital users significantly decreased from 15.2% to 9.5% (p < 0.001), whereas the proportion of hospital/nursing home users significantly increased from 76.9% to 88.5% (p < 0.001), and the proportion of clinic users decreased from 8.0% to 2.0% (p < 0.001).

For non-psychiatric hospitalization, the proportion of tertiary/general hospital users among younger adults significantly increased from 40.9% to 53.1% (p < 0.001), while the proportion of hospital/nursing home users significantly decreased from 51.4% to 39.6% (p < 0.001). The proportion of clinic users decreased slightly from 7.7% to 7.3% but the change was not significant (p = 0.258). Among older adults, the proportion of tertiary/general hospital users significantly increased from 42.6% to 46.8% (p < 0.001), whereas the proportion of hospital/nursing home users significantly decreased from 52.3% to 48.9% (p = 0.001), and the proportion of clinic users significantly decreased from 5.1% to 4.3% (p < 0.001). Supplementary Table 4 shows the detailed linear regression data for the changes in healthcare facility utilization patterns by age groups.

The LMM data of Supplementary Table 5 reveal trends in healthcare utilization patterns over time and between age groups. For psychiatric hospitalization, tertiary/general hospital utilization showed no significant differences between age groups initially (p = 0.953) or in temporal changes (p = 0.306), with no significant overall change over time (p = 0.952). For hospitals/nursing homes, no initial difference was detected between the age groups (p = 0.887), but utilization significantly increased over time (p = 0.044), with both groups showing similar trends (p = 0.664). Utilization of clinics significantly decreased over time (p < 0.001), older adults showing significantly lower initial utilization (p < 0.001) and a slower decrease in utilization compared to younger adults over time (p < 0.001).

No significant differences for non-psychiatric hospitalization were observed in tertiary/general hospitals and hospitals/nursing homes between the age groups initially (p = 0.083 and p = 0.089, respectively) or in temporal changes (p = 0.410 and p = 0.380), with no significant overall change in utilization (p = 0.991 and p = 0.999). Older adults initially utilized clinics at a significantly lower rate (p < 0.001), but no significant difference in the temporal change was observed between the groups (p = 0.380) or overall utilization pattern (p = 0.338).

These results align with the trends observed in Figs. 5 and 6, demonstrating a shifting pattern in healthcare facility utilization. The hospital/nursing home utilization rates for psychiatric hospitalizations in both age groups significantly increased over time, with older adults consistently exhibiting a higher utilization rate. In contrast, the utilization of tertiary/general hospitals remained stable in both groups, while clinic utilization significantly decreased in both age groups. These patterns contrasted with non-psychiatric hospitalization, which showed relatively higher utilization of tertiary/general hospitals and lower utilization of hospitals/nursing homes.

Discussion

We found a significant increase in both the numbers and prevalence of schizophrenia patients in South Korea from 2010 and 2021; the figures were higher for older adults. In South Korea, the proportion of individuals aged ≥50 years increased from 22.2% (2010) to 32.0% (2021)7. Advances in healthcare29 and medications30 may have extended the lifespans of schizophrenics, explaining the increase in the proportion of older patients. Indeed, we found that the proportion of schizophrenics aged ≥50 years rose from 37.0% in 2010 to 54.7% in 2021. Currently, more than half of all patients with schizophrenia are aged ≥50 years. Older adults with schizophrenia now constitute a significant proportion of the patient population; they require particular attention.

Their economic status and treatments must be reviewed. In South Korea, the extent of national health insurance coverage varies by economic status; low-income individuals receive medical aid31. The proportion of these people among older schizophrenia patients was remarkably high (44.9% in 2021), much higher than that of the general population aged ≥50 years (4.9% in 2021)32. The LMM data indicate that the situation will not change; a high proportion of older schizophrenia patients are of low economic status. This affects treatment. In 2021, the average psychiatric hospitalization length (251.8 days) of older patients significantly exceeded that of younger patients (167.2 days); the difference is expected to widen. Older patients increasingly reside in (principally psychiatric) hospitals or nursing homes, not tertiary or general hospitals; there is trend toward prolonged stays in more affordable healthcare facilities. This is in line with the substantial cost differences across Korean medical institutions.

For example, in 2022, the average daily hospitalization costs incurred by medical aid beneficiaries in tertiary hospitals ($454.22), general hospitals ($231.61), psychiatric hospitals ($49.58), and nursing homes ($67.76) varied significantly; psychiatric hospitals and nursing homes were much less expensive than tertiary and general hospitals33.

Changes in South Korean family dynamics and social structures have significant implications for older adults with schizophrenia and may part-explain the observed trends in healthcare utilization. Family involvement reduces the risk of relapse and helps patients to function34,35. However, the shift toward nuclear family structures in East Asian and Western countries36,37 means that older adults with schizophrenia receive less family care and support. This familial trend is driven by declining birth rates and later marriages, and may part-explain the longer hospital stays and higher utilization rates of hospitals and nursing homes by older patients with schizophrenia. The lack of family caregivers imposes greater reliance on institutional care, potentially explaining the extended hospitalizations and increased use of care facilities.

Our findings reveal significant physical health disparities between age groups, with older adults showing consistently higher CCI scores and longer non-psychiatric hospitalization stays than younger adults. Healthcare utilization patterns also differed between psychiatric and non-psychiatric conditions. For older adults, psychiatric hospitalizations predominantly occurred in hospitals/nursing homes (88.5% in 2021), while non-psychiatric hospitalizations reported higher utilization of tertiary/general hospitals (46.8% in 2021). These contrasting patterns suggest the need for distinct care delivery approaches for psychiatric and non-psychiatric conditions in older adults with schizophrenia. However, the adequacy of physical healthcare remains difficult to evaluate without comparative studies using age-matched controls. This is particularly concerning for those with extended stays in psychiatric facilities, who may face challenges in accessing appropriate specialized care.

It is difficult to manage behavioral issues, such as delusions and hallucinations, in nursing homes, as specialist psychiatric care is not readily available38. Older adults with schizophrenia are at higher risk than others of comorbid conditions, such as cardiovascular disease39,40 and cognitive impairment25,41. They are also more vulnerable to the side-effects of antipsychotic medications42,43,44. These complex care needs highlight the importance of integrating psychiatric and medical services in facilities where older adults with schizophrenia receive long-term care.

Our principal results aside, we made several additional notable findings. We observed a sudden decrease in the psychiatric hospitalization durations of older patients and medical aid beneficiaries from 2016 and 2017. This is probably explained by the 2017 revision of the Mental Health Act, which mandated stricter procedures for involuntary hospitalization and imposed limitations on hospital stays45. Similarly, Go et al. reported that the proportion of involuntary admissions significantly decreased from 64.3% in 2016 to 36.8% in 2017 following implementation of the revised Act46.

To allow meaningful comparisons with other studies, we focused on the schizophrenia prevalence in 2015; this the most recent, common time point across the studies. We found that the total prevalence of schizophrenia in Korea was then 0.67%, which was slightly different from the percentages of Cho et al. (0.50%)17 and Jung et al. (0.44%)18. These differences can be explained by variation in the definition of schizophrenia; to enhance the accuracy and comprehensiveness of our definition, we included patients with at least two outpatient visits or one inpatient admission under the schizophrenia diagnostic code, considering both primary and secondary diagnoses. We also excluded individuals prescribed cognitive enhancers before or within 12 months after their first antipsychotic prescription.

This study adds to previous research on schizophrenia prevalence in Korea. Notably, we focused particularly on patients of older age; this demographic is often overlooked. The Korean population is aging rapidly; our work on the prevalence and characteristics of schizophrenia in older adults is both timely and relevant. Additionally, the extensive observation period (from 2010 to 2021) allowed us to capture both long-term trends and recent changes in schizophrenia prevalence. This ensured a comprehensive view of the disease trajectory and yielded up-to-date information that will greatly improve current healthcare plans.

Despite these strengths, our study had several limitations. Although we tried to define schizophrenia accurately, slight overestimation of schizophrenia prevalence is possible given the diagnostic validity issues inherent in insurance claim data17. Additionally, our regression models did not account for potential confounding factors, such as medication use, detailed physical health conditions, and comprehensive socioeconomic indicators that might affect healthcare utilization patterns. Specifically, we used medical aid status as a proxy socioeconomic factor for low income; we lacked data on other socioeconomic factors and living arrangements that could have afforded a more comprehensive picture of patient circumstances. Future research should link to information on residential status and living arrangements, verify clinical records, and schedule structured diagnostic interviews to ensure accurate case identification and to gain a more comprehensive understanding of individual patient circumstances.

Conclusions

We found significant increases in the schizophrenia numbers and prevalence among South Koreans from 2010 to 2021, particularly among older adults, associated with population aging and improved healthcare. Older schizophrenia patients are more likely than others to be medical aid beneficiaries and require longer hospitalization, often in psychiatric hospitals or nursing homes. These findings highlight the need for tailored healthcare planning and services for older adults with schizophrenia; they have unique medical and socioeconomic needs. Future research should address the limitations of this study by incorporating more comprehensive data on patient clinical, socioeconomic, and living conditions. This would enhance our understanding of this vulnerable population.

Responses