Low-dose stress promotes sustainable food production

Crop production in changing environments

Sustainable food production faces an unprecedented crisis facilitated by multifaceted challenges such as toxicities induced in plants by air and soil pollutants at a global scale, enhanced activities of plant pests and diseases driven by climate change, and development of resistance of pests to pesticides, among others1,2,3,4. Such challenges suppress plant growth, productivity, and yields, while also downgrading the quality of plant products used for food1,2,3,4. Meanwhile, the population demands for more qualitative foods are increasing, creating an urgent task to manage plant stress, enhance crop performance and yield, and adapt plants and agroecosystems to global changes5,6. Hence, efficient management of plant stress is crucial for sustainable food production and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals achievement in the post-2020 era.

However, much is argued and offered as promising solutions by scientific research over the years, but what can be practically achieved? Potentially applicable and effective solutions at a global scale -including less rich or developed countries- should be cheaper, less technology-demanding, and easily accessible. For instance, breeding and genetic engineering are profoundly important and offer a unique opportunity for improvements, but they are time and technology-demanding, and the net benefit such technologies could offer is restricted by the limits of biological plasticity. That is, plants and other organisms have specific quantitative limits within which their photosynthetic, growth, and yield performance can be increased, and these limits cannot be exceeded. Therefore, instead of applying specific technologies for a limited benefit, a more universal approach would be to efficiently manage universal plant stress, i.e. the total stress induced in plants by the concurrent exposure to a broad range of key environmental challenges together in a specific environment.

The currently prevailed approach has been to target minimizing factors causing abiotic stress in plants (Table 1) and/or eliminate plant stress. Interventions are also applied to enhance crop productivity under abiotic stress and promote agricultural sustainability, including chemical (e.g. exogenous chemical application), genetic (e.g. breeding, gene editing), and microbial (e.g. beneficial microorganisms inoculation) approaches7,8. However, the approach of eliminating plant stress was based on the long-held scientific understanding that stress is harmful to plants and the associated perception stemming from the belief that stress is always bad. This was primarily due to the longstanding assumption that reactive oxygen species (ROS), which modulate plant stress, are harmful, and that plant traits critical to plant fitness and productivity, such as photosynthesis and chlorophylls, are suppressed by oxidative stress. Therefore, plant stress should be eliminated and interventions should be applied to increase plant performance and productivity.

What has changed in the scientific understanding of plant stress

However, in the last few years, it became clear that ROS (e.g. H2O2) not only are not harmful up to species-specific thresholds, but they could also be beneficial, acting as secondary messengers to mediate plant immune responses and improve performance and health (Fig. 1)9,10. Hence, ROS are essential for healthy functioning, and mild increases in ROS induced by stress offer benefits in plants with ROS levels within the optimal range11. This is also true for reactive nitrogen (e.g. NO) and sulfur (e.g. H2S) species, while there is a known molecular crosstalk among reactive oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur species11,12. Further, it has recently emerged that major traits critical to fitness and productivity, such as photosynthesis and chlorophylls, are typically enhanced by doses of stress smaller than the toxicological threshold for damages (subtoxic doses)10,13,14. The latter low-dose stimulations are linked with the mild ROS increment and associated modulation of the electron transport rate and non-photochemical quenching (NPQ), which protects the photosynthetic system from damage by excess light13,15,16. Ecophysiological evidence suggests that these mechanisms appear universally across plants and agents inducing oxidative stress, and act as signals to regulate metabolism and transcription factors and enhance enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants as well as defense hormones (Fig. 1)10,13,14,15,17,18,19. The low-dose stimulation is explained by hormesis, a generalized phenomenon that appears in a vast array of organisms as a biphasic response with restricted low-dose stimulation of commonly <60% and high-dose inhibition, describing the limits of biological plasticity14,20. Such stimulation by low-dose also preconditions (primes) plants and protects against more severe stress that may occur subsequently, whether from the same or different biotic or abiotic stressors17,20,21. Therefore, it is now clear that some stress is essential for improved performance of plants, pointing to the issue of how stress can be better managed to facilitate sustainable food production.

Diagram illustrates possible signaling pathways, processes, and functions affected by ROS. ABA abscisic acid, APX ascorbate peroxidase, AsA ascorbate, AUX auxin, C chloroplast, CAT catalase, CK cytokinin, ET ethylene, ETR electron transport rate, GSH glutathione, H2O2 hydrogen peroxide, JA jasmonic acid, M mitochondria, N nucleus, NPQ non-photochemical quenching of photosynthesis, P peroxisome, POD guaiacol-type peroxidase, PS photosystem, QY photosynthetic quantum yield, SA salicylic acid, SOD superoxide dismutase, V vacuole, VOC volatile organic compound. Created with BioRender.com.

However, a question arising is whether the low-dose stimulation at physiological level may increase fitness in agriculture, promoting sustainable farming that provides resources required to feed the current population while ensuring sustaining future generations at least as efficiently. In agriculture, besides the enhanced plant physiological performance, an indicator of fitness would be the yields and yield quality, and recent studies provide support for such desired outcomes. For instance, the herbicide glyphosate increased common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) productivity in both winter season (7.2 g a.e. ha–1) and wet season (36 and 54 g a.e. ha–1)22. Glyphosate (1.8 g a.e. ha–1) also increased shikimic acid and quinic acid, plant growth, yield, and technological quality of sugarcane (Saccharum spp.), with enhanced Brix% juice, recoverable sugars, pol% cane, tons of pol ha–1, and tons of culms ha–1 23. Moreover, nickel (Ni) increased photosynthetic pigments and photosynthesis and ureides and the number of seeds per pot and yield at 0.5 mg Kg−1 in cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp), whereas it caused adverse effects at 2–3 mg Kg−1 24. Cadmium (Cd) applied at 0. 5 mg Kg−1 also increased medicinal components (flavonoids) and biomass by ~60% and 20% a medicinal plant (Polygonatum cyrtonema Hua) whose tuber is used in traditional Chinese medicine19. Similarly, hexavalent chromium (Cr(VI)) application at a low concentration of 0.5 mg L−1 K2Cr2O7 induced hormesis, evident through increased biomass and larger leaves in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) plants, effects that were opposite from those at elevated application (5–10 mg L−1)11. In addition to chemicals, intermittent UV-B exposure (ambient ±7.2 kJ m−2 d−1) improved the growth of the medicinal plant Eclipta alba L. (Hassak) and the yield of wedelolactone, a promising compound with remarkable pharmacological values25. These selective examples, including replicated field evaluations22,23, indicate the promise of interventions based on low-dose stimulation to increase productivity, yields, and food quality, aiding to achieve food security and combat hunger and malnutrition in recognition of the lag behind meeting Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 for ‘Zero Hunger’ 26. However, revealing whether low-dose stress may increase fitness in agriculture requires integrated cost-benefit analyses in which environmental and economic benefits and impacts, will also be taken into account along with food safety and other risks (see next section for potential low-dose stimulation of crop pests).

Implications for practice

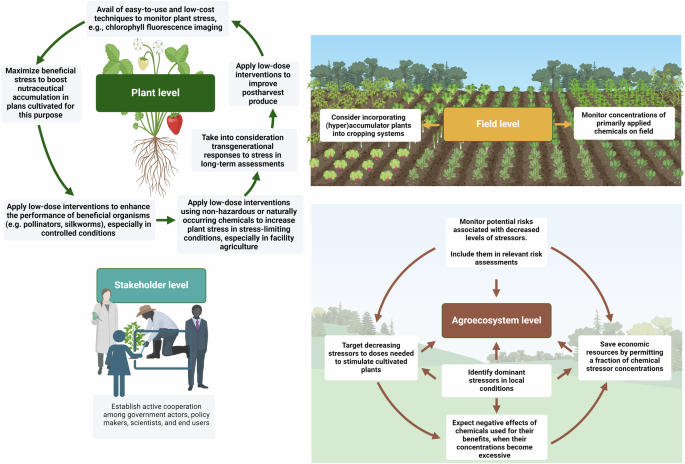

It emerges from the preceding discussion that, instead of applying other technologically demanding interventions to enhance plant performance to a rather limited extent, this could be achieved by producing or allowing an optimum level of stress in plants, especially since the maximum enhancement is restricted by the limits of biological plasticity and would not be exceeded regardless of the intervention. However, the application of the concept in the practice is challenging, and there are various aspects that need to be considered in a roadmap toward the implementation of low-dose stress to facilitate sustainable food production (Fig. 2). It is also important to note that this exposition refers specifically to abiotic stressors as stimulatory agents but does not recommend the use of biotic stressors. That is because the application of biotic stressors is more challenging, due to population and community ecology phenomena (e.g. network complexity, Allee effect), and might unintentionally result in pest outbreak or epidemic27.

Created with BioRender.com.

First, substantial evidence emerged in the last few years showing that various chemicals in the environment induce aforementioned positive effects on many kinds of plants. These include insecticides, fungicides, herbicides, metallic elements, micro/nanoplastics and other particles, human and veterinary pharmaceuticals, and other chemicals10,13,14,15,18. The dominant stress-inducing chemicals under local conditions should be identified. However, environmental standards and (phyto)remediation programs should consider targeting not the complete removal of these stressors, but their decrease to concentrations as needed to induce positive effects. For example, a recent meta-analysis of about 8500 dose responses from the published literature revealed that cerium (Ce), a rare earth element widely applied for its positive effects on plants, commonly increases chlorophylls, stomatal conductance (uptake of air), photosynthesis, and biomass at concentrations from as low as below 0.1 mg L−1 to 25 mg L−1 but suppresses these traits at concentrations over 50 mg L−1 across species18. Importantly, current technological advancements make difficult and considerably expensive the removal of the smallest fraction of such chemicals from the environment, perplexing or making it often practically impossible for the removal of the lowest 10% of the chemicals. Instead, major economic resources and efforts would be saved by allowing the maximum permissible concentrations in the environment (inducing positive effects on plants), assuming these are below the safety limits for environmental and human safety standards.

These new advances in the scientific understanding of chemical-induced dual (hormetic) effects also indicate that the effects of chemicals widely used in the agricultural practice, as is the case of the long history of rare earth element application in China, can turn from positive to negative depending on the concentration. Therefore, care should be exercised that major chemicals applied in the field are maintained at desired levels, avoiding their excessive accumulation and persistence in the environment. To this end, analysis of environmental media every several years (or decadal) to ensure that the concentrations of few major applied chemicals do not exceed specific thresholds would facilitate maximization of the desired effects on plants. This could be incorporated into local farming practices, at a relatively low cost, but would require the existence of specialists providing such analytical services. However, in the realm of biodiversity conservation and SDGs, various types of (hyper)accumulator plants could also be incorporated into the cultivations, for instance as part of a rotation system, in mixed-species cultivation, in specific sub-plots in a cultivation, and/or surrounding a land plot. This would promote diversification, which facilitates SDG 15 ‘life on land’, while also reducing the concentrations of chemicals with hormetic effects, such as heavy metals. Routine incorporation of (hyper)accumulators in cropping systems would also provide other benefits, such as potentially reducing crop herbivory (due to accumulation of chemicals toxic to herbivores), and lowering the need of chemical analyses of environmental media by acting proactively.

Important to note is also that abiotic stress-inducing agents do not need to be environmental contaminants, but in “clean” environments naturally-occurring chemicals and gaseous molecules (e.g. hydrogen peroxide, hydrogen sulfide, nitric oxide, etc) and/or physical agents with no residue in the environment (e.g. radiation, cold, etc) could be applied under controlled conditions to induce stimulatory adaptive responses before seedling transplantation into the field. This approach is also highly relevant and applicable to facility agriculture, such as in greenhouses, where stress-free conditions are commonly targeted. The perspective provided herein indicates that manipulations can easily be applied to create optimum stress conditions. For example, by introducing hormesis-inducing chemicals and maintaining them at optimum stimulatory concentrations, especially in hydroponic cultures where the regulation is relatively easier and straightforward. Moreover, this concept shows promise for practical application to induce the production of nutraceuticals and other plant-producing chemicals that are used to improve human health, as low doses of stress boost the production of such chemicals28. Where plants are cultivated for such use only, plant stress can be maintained up to a level before the nutraceutical levels start decreasing. Besides plants, such techniques (e.g. low-dose radiation) can be applied to organisms that are beneficial for different purposes in the agricultural practice, such as to promote the growth of silkworms29 or the performance of pollinators30 released to facilitate pollination as for example in the controlled cultivation of some vegetables.

Second, the vast majority of scientific research involves one or at best two abiotic stressors concurrently administered to plants, while in reality there are numerous stressors acting together. It is well-known that the responses of plants to mixtures of stressors can differ from those of individual stressors, but the low-dose positive effects were widely induced by mixtures, which requires that at least one component of the mixture inducing stimulatory effects. It is practically infeasible to examine all possible stressors in a given environment, such as a specific crop cultivation area. However, identifying the top 1–3 abiotic stressors based on their levels and potency and regulating their concentrations at levels expected to induce hormesis may provide a fast-forward solution when other concurrent stressors are not manipulated. This would require support by local authorities, which would perform the required environmental monitoring and analyses and develop and adopt relevant policies for the control of the levels of such stressors. Hence, a close cooperation between government actors, policy makers, scientists, industrial stakeholders and end-users (farmers) is needed.

Third, it needs to be understood that, through epigenetic mechanisms, low-dose stimulation of parents can transfer precious information to offspring, which enhances offspring functioning early or later in their life without the offspring be directly exposed to stress yet17. This conditions offspring to perform better when facing stress later on. Therefore, the tolerance of plants to stress under local conditions may change over time and generations31, affecting the concentrations needed to induce and maintain stimulatory effects. This property should be factored in the long-term assessments. Moreover, if low-dose stimulation leads to selection of more resistant individuals within a population as indicated for weeds32,33, evolutionary agroecology suggests that genotypes with intermediate (but not highest) fitness can produce the highest-yielding populations34. Hence, a target for long-term assessments would also be to identify the optimum fitness in low dose-stimulated crop populations up to a point after which the yields start to decrease due to exceeding the degree of fitness that permits highest yields. This natural selection process mediated by low-dose stimulation interventions could further determine the fitness in agriculture and therefore sustainable crop production.

Fourth, there are various ways for detecting plant stress. Among them, chlorophyll fluorescence imaging analysis is a method with great and rapid sensitivity, detecting stress within 15–30 min15. Importantly, it is non-invasive and relatively low-cost, permitting a wider utilization15. A novel efficient index of early stress detection is the proportion of open reaction centers of photosystem II (PSII) (qp)15, which can be used for systematic monitoring of plant stress status. A question of practical relevance that arises is how much dose is considered low dose and how a low level of stress can be managed. Accepting that the target is to stimulate cultivated plants, low doses are those that enhance fitness critical traits (e.g. photosynthesis, chlorophylls, fluorescence quantum yield, qp) and endpoints (e.g. growth, survival, productivity, reproduction). A dose to be low (subtoxic) should not cause biologically negative effects on the cultivated plants, and this can be controlled by monitoring plant health indicators such as quantum yield and qp in order to maintain the stress at desired levels. A low dose would cause stimulation initially, but the enhancement may not persist, requiring re-application of the stressor. Therefore, weekly observations of indicators (e.g. quantum yield, qp) would reveal whether further stressor addition is needed to extend the stimulation as desired. Considering that plants can acclimate to low-dose stress and develop tolerance, a higher dose may be needed over time to sustain stimulation. Despite the dose increases, it is still considered a low dose when it causes no biologically negative effects or even positively affects the cultivated plants. However, if plant stress monitoring indicates tendency for negative effects, the stressor could be minimized or eliminated and allow plant recovery for 1–2 weeks. Considering also the genotypic degrees of susceptibilities, different cultivars or varieties of the same plant species are expected to have different dose requirements. Moreover, care should be exercised when selecting doses to apply doses that do not enhance plant pest populations with the potential for outbreak. Therefore, regular observations of pests are warranted alongside plant stress status monitoring.

Fifth, the lowering of concentrations of contaminants in the environment may introduce risks associated with the low-dose stimulation. For example, recently the European Union proposed to reduce chemical pesticides use and risk by 50% by 2030 (https://food.ec.europa.eu/plants/pesticides/sustainable-use-pesticides_en). However, such a reduction may result in the enhancement of pests, diseases, and weeds of crop cultivations, if the lower concentrations induce unidentified low-dose stimulation in such biotic threats to crops, as well as the development and promotion of pesticide resistance32,35,36. For example, herbicide-resistant weeds show enhanced propagation and spread at doses recommended for application to control weeds, and, even in weed populations that are on average sensitive to herbicides, a subpopulation of ‘stronger’ plants can be favored by hormetic responses32. Moreover, the herbicide glyphosate increased the number of seeds (+114% and +41%) and capitulum (+37%, +48%) per plant in sensitive (at 0.7 and 2.8 g a.e. ha–1) and resistant (at 5.6 and 5.6 g a.e. ha–1) biotypes of the crop weed Conyza sumatrensis31. This indicates increased reproduction of the weed, and suggests potential risks for fitness in agriculture. Similar findings for hormetic stimulation by such chemicals were reported for other crop weeds, commonly with resistant biotypes undergoing stimulation by higher doses compared to susceptible biotypes37. Therefore, the low-dose stimulation should be incorporated in all assessments of effects of and risks introduced by co-occurring organisms that can become harmful to cultivated plants.

Sixth, low-dose stimulation by irradiation and other physical and chemical stressors can be successfully applied in postharvest produce, offering benefits in the secondary metabolites linked with improved human health, facilitating the management of pathogen that downgrade produce quality, and improving the quality of food products and extending their lifespan38. The biological mechanisms explaining these are in line with those explained for plants, and involve ROS modulation38. Hence, low-dose stress can decrease postharvest losses, a major undermining factor of food production, and offer remarkable improvement to postharvest produce.

All in all, it is becoming increasingly evident that low-dose stimulation is of vital importance in food production, and its acknowledgement, understanding, inclusion in relevant research, and study can facilitate sustainable food production. The dual effects of stress present a double-edged sword with various implications for practice, which are summarized herein.

Responses