M1 recruitment during interleaved practice is important for encoding, not just consolidation, of skill memory

Methods

Participants

Participants assigned to IP with cathodal stimulation at the right M1, and two sham conditions, each including a separate group of 18 participants, received training in either an RP or IP format. Real (IP-ctDCS) or sham (RP-Sham, IP-Sham) stimulation was applied during the entire 20-min period of practice. Participants were blinded to the stimulation condition. All participants completed an informed written consent approved by Texas A&M University’s Institutional Review Board before any involvement in the experiment.

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS)

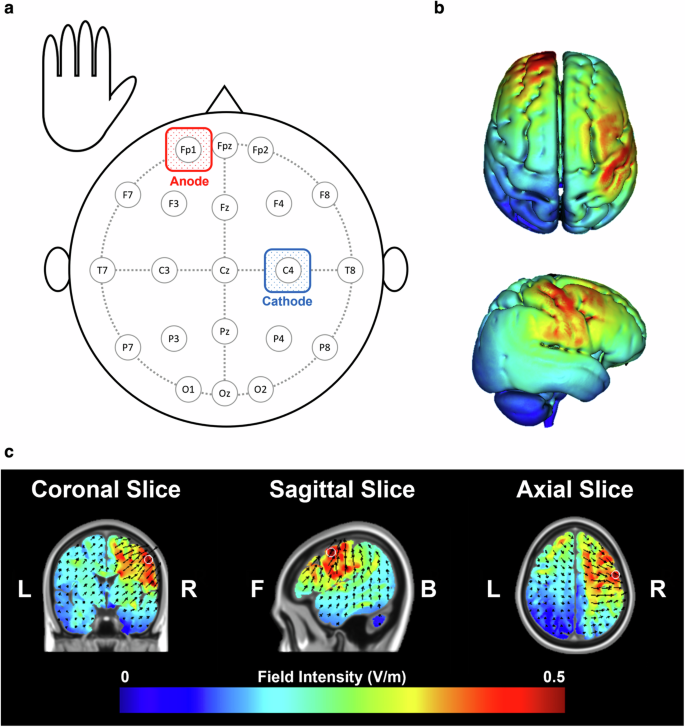

We targeted the right M1 with a 1 (times) 1 tDCS electrode montage. Real stimulation consisted of a 2 mA current applied via a 25 cm2 (5 (times) 5 cm) cathode and a 35 cm2 (5 (times) 7 cm) reference electrode covered by saline-soaked sponges, resulting in a maximum current density of 0.08 mA/cm2 administered using a 9 V battery-driven stimulator (tDCS Stimulator; TCT Research Limited, Hong Kong). The cathode was located at the right M1 (i.e., C4, International 10–20 system) and was paired with a reference electrode above the left supraorbital region.

This placement system has established accuracy for targeting M1, with the current flow simulation shown in Fig. 3. The current flow associated with this electrode montage was modeled using HD-ExploreTM (Soterix Medical Inc., New York, NY) and revealed heightened current flow at regions described as right M1 in the human motor area template33. Participants in sham stimulation conditions (RP-Sham, IP-Sham) involved the same electrode configuration, but stimulation was only delivered for 30-s at the beginning and end of the training period.

a Cathodal stimulation for the interleaved practice, real tDCS condition involved placement of the cathode 20% of the auricular measurement from Cz (determined based on the International 10–20 system) which placed this electrode above C4 with a reference electrode at the left supraorbital region. Participants in sham stimulation conditions (Repetitive-Sham, Interleaved-Sham) involved the same electrode configuration, but stimulation was only delivered for 30-s at the beginning and end of the training period37. b, c The expected field intensity of 2 mA tDCS at C4 and the associated current flow for this electrode montage was modeled using HD-ExploreTM (Soterix Medical Inc., New York, NY). This figure illustrates the right M1, noted with a white circle.

Motor sequence learning task

We employed a motor sequence learning task, specifically, a discrete sequence production task20. To ensure that we studied cortical activity related to motor execution rather than stimulus-response mappings and probabilities34,35, we did not use the four-finger (one per button) design of the traditional serial reaction time task paradigm7. Instead, our participant used only their left index finger for all keys17,18,19, which creates real, non-isometric motor demands in the context of a key pressing task36 (Fig. 1a). A standard keyboard was used. Individuals executed a keypress to a visual signal that was spatially compatible with the position of the key. Once a correct key was pressed, the next visual signal in the sequence was presented. The primary dependent variable assessing motor sequence performance was total response time (TT), which was the interval from the presentation of the first stimulus to the correct execution of the final keypress of the motor sequence.

All individuals completed nine blocks of 21 trials each, totaling 189 trials of practice. These 189 trials were divided between three 6-key motor sequences (63 trials per sequence). The content of each block depended on practice schedule (Fig. 1b). For RP, each block contained 21 repetitions of a single sequence; for IP, each block contained 7 trials of each of the three sequences, presented in counterbalanced order. Test blocks were presented in RP format without stimulation. All participants completed 3 Test blocks at 4 occasions: prior to training (Pre), immediately after training (Post), 5 min, 6 h later, and 24 h later (Fig. 1b).

Statistical analyses

To ensure the normality of the data used in this study, we assessed it using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The test statistic (W) was 0.97, with a corresponding p value of 0.21. As the p-value was greater than 0.05, we failed to reject the null hypothesis that the data were normally distributed; therefore, we used parametric ANOVA for all analyses. In addition, a Bonferroni adjustment was made when conducting post-hoc multiple comparisons. An initial 3 (Group: RP-Sham, IP-Sham, IP-ctDCS) between-subject ANOVA was conducted to assess if individuals assigned to each of the experimental conditions exhibited similar performance during the baseline test block. The evaluation of online performance (during training) was assessed using two separate two-way ANOVAs with repeated measures on the last factor: (1) Group (IP-ctDCS, IP-Sham) (times) Block and (2) Group (IP-Sham, RP-Sham) (times) Block. To determine the effect of ctDCS in M1 and practice structure in offline performance gains, two separate two-way ANOVAs with repeated measures on the last factor were performed: (1) Group (IP-ctDCS, IP-Sham) (times) Time Point (Post5min, Post6h, Post24h) and (2) Group (IP-Sham, RP-Sham) (times) Time Point (Post5min, Post6h, Post24h). This approach, conducting two separate analyses for (1) IP-Sham vs. RP-Sham and (2) IP-Sham vs. IP-ctDCS allowed for a focused examination of the effects of practice schedule and stimulation on M1 on online/offline learning, enhancing clarity in interpretation. If we find significant effects, we used Tukey’s Honest Significant Differences post-hoc assessment to identify differences in means.

Responses