Maternal high-fat diet exacerbates atherosclerosis development in offspring through epigenetic memory

Main

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death worldwide despite the availability of risk factor management and interventional therapies1. Atherosclerosis is an important process leading to mortality in CVD. It is a chronic, progressive, inflammatory disease characterized by the formation of plaques, consisting of various vascular cells, lipids and tissue debris, in the arterial intima2.

As early as 1986, David Barker proposed the ‘developmental origins of health and disease’ (DOHaD) theory, which postulates that adverse nutritional environments in the womb can elevate the incidence of chronic diseases, such as CVD, in adult offspring3. In recent years, obesity caused by excessive nutrition or adverse stimulation by lipopolysaccharide during pregnancy has been shown to increase the risk of CVD in the offspring4,5. Earlier studies showed that maternal consumption of a high-cholesterol diet during pregnancy can cause persistent gene expression changes in the aorta of low-density lipoprotein receptor deletion (Ldlr−/−) mice6, and feeding ApoE knockout mice a high-fat diet during gestation and lactation was found to exacerbate atherosclerosis in their adult offspring by enhancing the pro-inflammatory response of thoracic periaortic adipose tissue7. Recent clinical data indicate that maternal plasma total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) levels affect the size of atherosclerotic lesions in the fetal aorta and the methylation status of the fetal SREBP2 gene8. These findings have spurred growing concern about the effects of maternal high-fat diet on offspring atherosclerosis, but the underlying mechanisms have not been fully elucidated.

Epigenetic mechanisms, which alter chromatin accessibility by modifying DNA and nucleosomes, may be central mediators in the occurrence and progression of metabolic diseases and subsequent CVD9,10. The most common epigenetic modifications in mammals include DNA methylation, histone modifications and RNA modifications involving microRNAs and long-intergenic non-coding RNAs. Alterations in chromatin accessibility can increase or decrease the likelihood of interactions between gene regulatory regions and transcriptional machinery, giving rise to changes in gene expression9,11. Macrophages have been reported to play a key role in maternal Western-type diet (WD)-induced atherosclerosis in offspring due to alterations of the epigenetic state of the progeny macrophage genome and changes in macrophage polarization12. However, although atherosclerosis is initiated by endothelium activation, little is known about the specific epigenetic impacts of maternal WD on progeny endothelial function in this disorder.

We hypothesized that maternal WD aggravated the progression of atherosclerosis in offspring through endothelial epigenetic mechanisms. In the present study, we found that maternal WD augmented the area of atherosclerotic plaques in offspring mice re-fed WD began at 8 weeks after birth for 8 weeks. This phenotypic change was due to inflammatory memories created in response to the first stimulus by functionally distinct epigenomic priming mechanisms, which were stably stored in endothelial cells (ECs) at the levels of transcription and chromatin accessibility, making the offspring mice respond more quickly and drastically to the WD stimulus in adulthood. We also found that this distinct reprogramming of chromatin organization in memory ECs was exploited by the transcription factor (TF) activator protein-1 (AP-1) for efficient transcriptional reactivation, and inhibiting its binding to target genes could alleviate the occurrence and development of atherosclerosis. Moreover, our metabolomics, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and CUT&RUN–qPCR analyses indicated that the oxysterol 27-hydroxycholesterol (27-HC) was essential in memory establishment and recall. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that maternal WD accelerates atherosclerotic plaque progression in offspring through epigenetic memory mechanisms, and we identify AP-1 as an epigenetic therapeutic target for preventing atherosclerosis.

Results

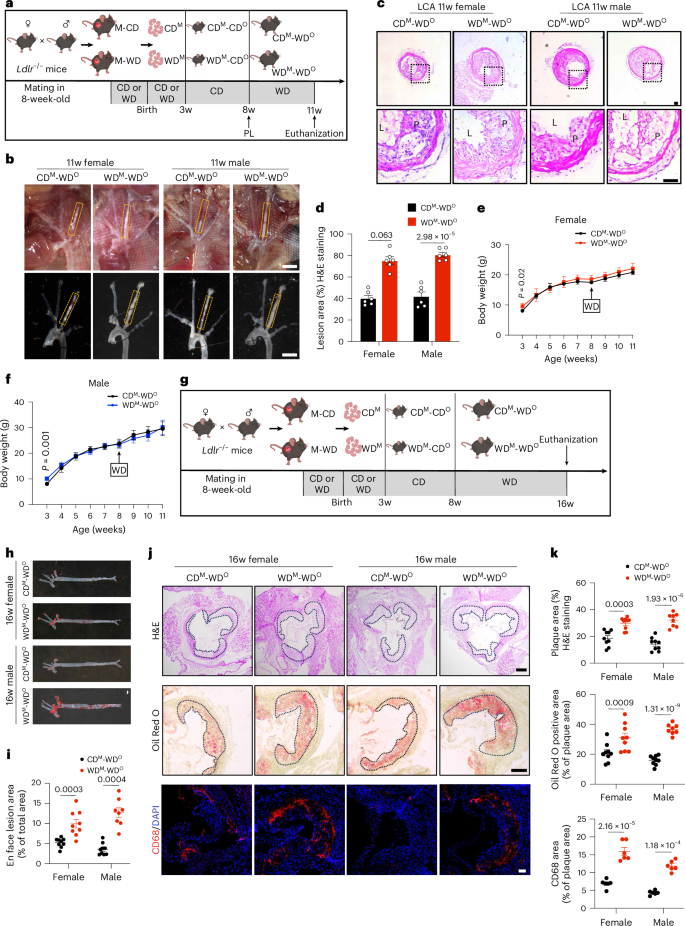

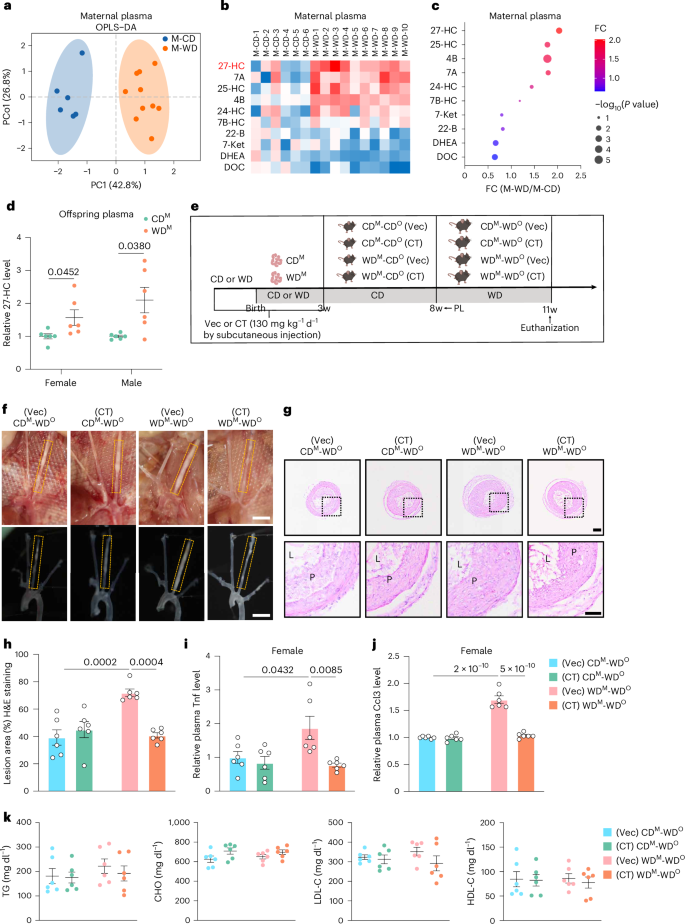

Maternal WD accelerates atherogenesis in offspring

To study the effect on offspring of maternal exposure to WD, we fed maternal Ldlr−/− mice with chow diet (CD) or WD during gestation and lactation, referring to them as M-CD or M-WD mice and referring to their offspring as CDM or WDM mice, respectively. After weaning, these two groups of offspring mice were fed CD until 8 weeks of age, and we referred to these offspring as CDM-CDO or WDM-CDO mice, respectively, during this period. Subsequently, we performed partial ligation of left carotid arteries (LCAs) in CDM-CDO and WDM-CDO mice and subsequently fed them WD for 3 weeks after surgery. During this period, we referred to these offspring as CDM-WDO or WDM-WDO mice (Fig. 1a). Carotid ultrasounds showed successful ligation (Extended Data Fig. 1a). After 3 weeks of WD feeding, the plaque area of ligated LCAs was importantly exacerbated in both the female and male WDM-WDO mice (Fig. 1b–d). We observed that average body weight was higher in the WDM mice than in the CDM mice after weaning, but this difference disappeared after CD recovery and after 3 weeks of WD feeding, irrespective of sex (Fig. 1e,f). The results of the intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) showed a similar blood glucose level (CDM-CDO versus WDM-CDO mice) in both the female and male mice at the timepoints of 15, 30, 60, 90 and 120 minutes after intraperitoneal injection of glucose (Extended Data Fig. 1b,c). Plasma triglyceride (TG), cholesterol (CHO), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and LDL-C levels were similar between the CDM-CDO and WDM-CDO mice as well as the CDM-WDO and WDM-WDO mice, irrespective of sex (Extended Data Fig. 1d–g).

a, Timeline of mouse feeding and schematic of experimental strategy. PL, partial ligation. b, Representative images of arterial tissues isolated to examine atherosclerotic lesions after 3 weeks post-ligation in both female and male mice. Dashed orange boxes represent LCA. Scale bar, 2 mm. c,d, Representative H&E staining images (c) and quantification of lesion areas (d) of ligated LCA sections (n = 6; scale bar, 50 μm). e,f, Body weight (BW) of female (e; n = 9) and male (f; n = 8) offspring mice at the corresponding weeks. g, Timeline of mouse feeding. h,i, Representative images (h) and quantitative analysis (i) of ORO staining of aortas from female and male offspring Ldlr−/− mice fed WD for 8 weeks (n = 9 versus 9 versus 9 versus 8; scale bar, 2 mm). j, Representative images of H&E staining (above; scale bar, 250 μm), ORO staining (middle; scale bar, 250 μm) and CD68 immunofluorescent staining (below; scale bar, 100 μm) of aortic root sections. Black dashed lines demarcate atherosclerotic plaques. k, Quantification of the aortic root lesion area by H&E staining (above; n = 9 versus 9 versus 9 versus 8) and quantification of ORO (middle; n = 9 versus 9 versus 9 versus 8) and CD68+ (below; n = 6) areas in plaques. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (d, i and k) and Welch’s t-test (e and f) were used to determine statistical significance. w, weeks old.

Source data

To further determine the effect of maternal WD feeding on offspring atherosclerosis, we induced atherosclerosis in the offspring mice by feeding them WD for 8 weeks, and we also referred to these offspring as CDM-WDO or WDM-WDO mice during this period (Fig. 1g). After feeding the adult offspring mice WD for 8 weeks, Oil Red O (ORO) staining of whole aortas revealed significantly increased atherosclerotic lesion areas in both the female and male WDM-WDO groups (Fig. 1h,i). We then performed a more detailed analysis of aortic root plaque composition, finding that the plaque area, the ORO-positive area and macrophage infiltration were significantly increased in the atherosclerotic lesions of the female and male WDM-WDO group (Fig. 1j,k). Blood glucose levels and plasma lipid levels were similar between the two groups (Extended Data Fig. 1h–k). These findings indicate that maternal WD accelerates the occurrence and development of atherosclerosis in offspring.

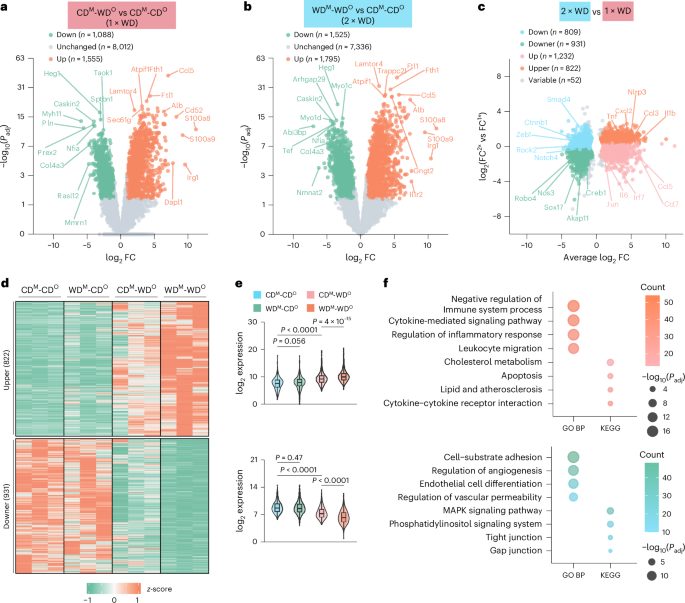

WD exposure enhances the response of offspring ECs to WD

EC dysfunction has been observed in the early stage of atherosclerosis. To identify the molecular mechanisms and affected gene pathways underlying the offspring atherosclerosis induced by maternal WD exposure, we isolated and performed SMART-seq on mouse aortic ECs (MAECs) from mice in the CDM-CDO/WDM-CDO groups and in the CDM-WDO/WDM-WDO groups that were given WD again for 4 weeks (Extended Data Fig. 2a). We explored the effects of WD after 4 weeks of feeding because minimal atherosclerotic lesions could be observed at this early timepoint13. Principal component analysis (PCA) showed the reasonableness of intra-group and inter-group differences (Extended Data Fig. 2b). Consistent with a previous report14, WD altered gene expression in arterial ECs of adult mice (CDM-WDO versus CDM-CDO = 1×WD; Fig. 2a). Interestingly, we observed that the maternal exposure to WD during pregnancy and lactation did not significantly impact on gene expression in ECs of offspring compared to those in the offspring from CD-exposed dams, when they resumed to CD after weaning for 5 weeks (WDM-CDO versus CDM-CDO; Extended Data Fig. 2c). Upon switching to WD for 4 weeks, the offspring from WD-exposed dams exhibited more significant gene expression changes in ECs than those from CD-exposed dams (WDM-WDO versus CDM-CDO = 2×WD), such as Tnf, Nlrp3 and Ccl3 (Fig. 2b,c). To further explore the effect of maternal WD exposure on gene expression in ECs, we next compared the difference between 2×WD and 1×WD. We first classified ‘Up’ or ‘Down’ genes that were upregulated or downregulated at similar levels between 2×WD and 1×WD (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 2d,e). The Up genes were enriched in biological pathways relevant for cytoplasmic translation and oxidative phosphorylation, whereas the Down genes were enriched in endothelium functions such as cell differentiation and proliferation (Extended Data Fig. 2f). These findings indicated that WD exposure during adulthood changed metabolism in ECs of mice, which was not influenced by maternal WD exposure. Next, we identified ‘Upper’ genes that were upregulated more substantially in 2×WD than in 1×WD and ‘Downer’ genes that were correspondingly further downregulated (Fig. 2d–f). Gene Ontology (GO) Biological Process (BP) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses of these Upper and Downer genes revealed that the former showed strong pro-inflammatory, pro-apoptotic and pro-atherosclerotic effects, whereas the latter were enriched in pathways related to angiogenesis and tight junctions, suggesting endothelium dysfunction (Fig. 2f). These data suggest that, although WD dramatically modified gene expression in offspring ECs in adult mice, maternal WD exposure exhibited a specific role in enhancing the inflammatory response of offspring MAECs to cope with challenge again.

a, Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (CDM-WDO versus CDM-CDO = 1×WD). |log2FC| ≥ 1, Padj < 0.05, n = 3. b, Volcano plot of DEGs (WDM-WDO versus CDM-CDO = 2×WD). |log2FC| ≥ 1, Padj < 0.05, n = 3. c, Further grouping of DEGs. Scatter plot shows five different gene sets. Upper, orange; Downer, green; Up, pink; Down, blue; Variable, gray. FC2×WD/FC1×WD > 1.3. Up: DEGs in either 1×WD or 2×WD were upregulated. Down: DEGs in either 1×WD or 2×WD were downregulated. Upper: DEGs in 2×WD were upper than those in 1×WD. Downer: DEGs in 2×WD were lower than those in 1×WD. d, Heatmap showing mRNA levels for genes within the Upper (above) and Downer (below) groups. e, Scaled expression of Upper and Downer genes in each of the four groups. f, Bubble plot showing the enriched GO BPs and KEGG pathways by analyzing the Upper and Downer genes in MAECs. Gene expression is depicted in violin plots, displaying maximal, minimal and median values and the 75th and 25th percentiles (e). Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to determine statistical significance.

Source data

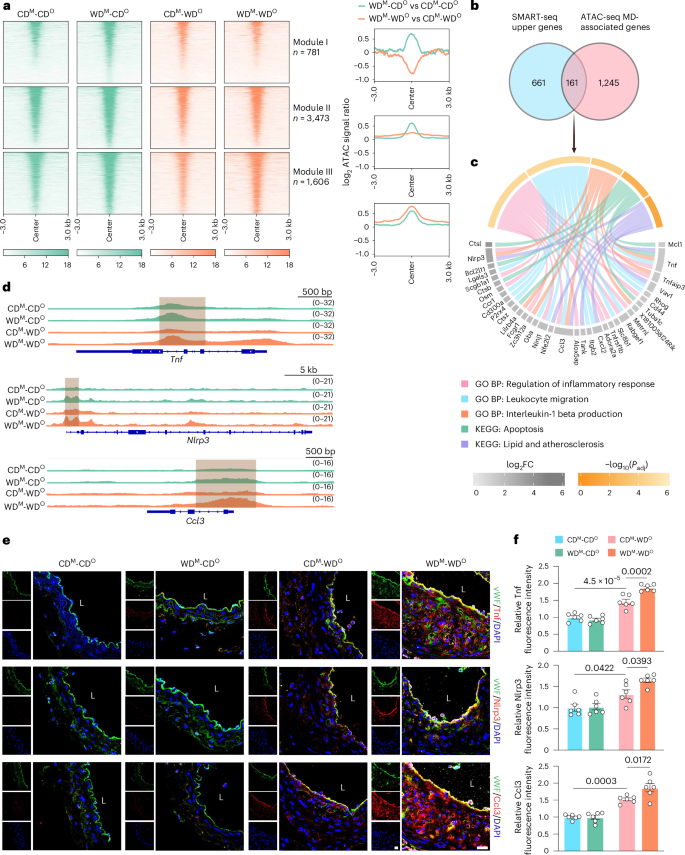

Maternal WD feeding confers inflammatory memory in offspring at the chromatin level

Our previous data suggested that offspring MAECs exhibited a more rapid and amplified pro-inflammatory response to WD feeding in WD-fed versus CD-fed maternal mice. We hypothesized that epigenetic memory was responsible for this difference. The definition of epigenetic memory is that when the cells are first stimulated by inflammation (for example, TNF and lipopolysaccharide), epigenetic changes (for example, histone modifications and changes in chromatin conformation) occur at the chromatin level so that the accessibility of chromatin will increase and continue to maintain this accessibility after the inflammation has subsided15. The chromatin regions with those characteristics are defined as the memory domains (MDs). When the cell is stimulated again, the inflammatory memory is activated, allowing the cell to respond more quickly and strongly to secondary stimuli.

To investigate whether WD exposure altered the chromatin landscape of ECs, we performed assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq) on MAECs from CDM-CDO, WDM-CDO, CDM-WDO and WDM-WDO mice (Extended Data Fig. 3a). From these data, we identified a total of 33,630 open chromatin regions, mainly concentrated in the promoter, exon and intergenic regions and in other DNA functional regulation regions (Extended Data Fig. 3b), and the correlation analysis is shown in Extended Data Fig. 3c. Subsequent differential analysis of these regions revealed massive changes in chromatin accessibility between CDM-CDO and WDM-CDO mice. We defined the 5,860 chromatin regions with higher accessibility in WDM-CDO mice as WD-sensitive domains (Fig. 3a). Of these, the 781 regions of module I that were more closed in WDM-WDO mice relative to CDM-WDO mice; and the 3,473 regions of module II that were slightly more open in WDM-WDO mice relative to CDM-WDO mice; and the 1,606 regions of module III that were significantly more open in WDM-WDO mice relative to CDM-WDO mice were defined as MDs (Fig. 3a). Differential analysis of all peaks also revealed regions of significantly decreased (526 peaks) and unchanged (27,244 peaks) accessibility between WDM-CDO and CDM-CDO mice; we classified them as module IV/V/VI/VII (Extended Data Fig. 3d).

a, Heatmaps (left) showing ATAC signals for each specified peak cluster in the indicated four groups. The signal strengths are denoted by color intensities. Line graphs (right) indicating differences in chromatin accessibility between WDM-CDO versus CDM-CDO and WDM-WDO versus CDM-WDO groups. b, Venn diagram showing the overlap of Upper genes (n = 822) and MD-associated genes (n = 1,406). c, Chord diagram displaying important GO BPs, KEGG pathways and representative genes. d, IGV plots showing normalized ATAC signals at selected gene loci. Gray boxes denote MD-associated regions. e, Representative immunofluorescence staining images of Tnf (upper panels), Nlrp3 (middle panels) and Ccl3 (lower panels) in LCA ECs from CDM-CDO, WDM-CDO, CDM-WDO and WDM-WDO Ldlr−/− mice (Tnf, Nlrp3 and Ccl3, red; vWF, green; scale bar, 40 μm; L, lumen). f, Quantitative analysis of the fluorescence intensities of Tnf (above), Nlrp3 (middle) and Ccl3 (below) in ECs (n = 6). Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to determine statistical significance.

Source data

To gain further insights into the unique properties of these MDs, GO BP analysis of MDs (module III) was performed and revealed terms related to immunity response and cytokine-mediated signaling pathways, indicating that MDs are closely related to inflammation and that re-exposure to the memory-forming stimulus has the potential to accelerate atherosclerotic progression in offspring (Extended Data Fig. 3e).

Therefore, the overlap of Upper genes (n = 822) identified by SMART-seq and MD-associated genes (n = 1,406) from ATAC-seq were subjected to GO BP and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses. These genes still exhibited strong pro-inflammatory and pro-atherosclerotic effects, suggesting that the immune memory of these inflammation-related genes, such as Tnf, Nlrp3 and Ccl3, might play important roles in atherosclerosis in offspring (Fig. 3b–d). Immunofluorescence staining of LCA sections (partial ligation of LCA and WD feeding for 3 weeks) showed that the expression levels of Tnf, Nlrp3 and Ccl3 in MAECs were increased in the CDM-WDO group compared to the CDM-CDO group. Notably, their expression levels were also significantly higher in the WDM-WDO group than in the CDM-WDO group (Fig. 3e,f). These findings indicate that maternal WD feeding imparts epigenetic memory of inflammation in offspring ECs at the chromatin level.

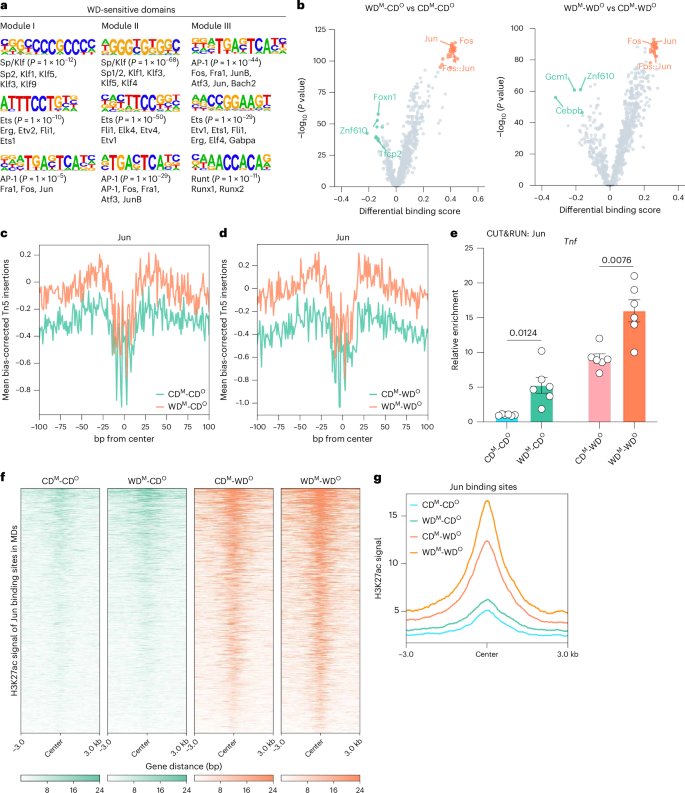

ATAC-seq reveals a putative role for AP-1 in regulating EC chromatin dynamics

We next sought to identify TFs involved in establishing MDs and to explore their molecular mechanisms. We performed motif enrichment analysis on DNA sequences, finding that members of the AP-1 TF family (for example, Jun and Fos) were significantly enriched in MDs (Fig. 4a). Other domains were substantially enriched in Sp/Klf or Ets family (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 4a). We also conducted TF footprint analysis to predict the actual TF binding in the MDs. The binding signal of Fos and Jun was significantly higher in WDM-CDO versus CDM-CDO and WDM-WDO versus CDM-WDO mice (Fig. 4b). When we looked specifically at Jun motifs across all ATAC-seq peaks, we found a significantly greater TF footprint in MAECs isolated from WDM-CDO mice compared to CDM-CDO mice, suggesting that Jun bound to chromatin that was more accessible in WDM-CDO MAECs (Fig. 4c). Notably, the binding signal of Jun was significantly higher in WDM-WDO mice compared to CDM-WDO mice (Fig. 4d). Analogously, CUT&RUN–qPCR was employed to determine whether maternal/offspring WD feeding increased Jun binding specifically on Tnf within its MDs, again finding significant increases in the WDM-CDO versus CDM-CDO and the WDM-WDO versus CDM-WDO mice (Fig. 4e). The expression of Jun was higher in ECs of newly weaned offspring from WD-exposed dams during pregnancy and lactation than those with CD exposure (Extended Data Fig. 4b), whereas it returned to a similar level after another 5 weeks of CD feeding (Extended Data Fig. 4c). Moreover, even when the offspring were fed WD, Jun expression did not change between the two groups (WDM-WDO versus CDM-WDO; Extended Data Fig. 4c). These might imply that the regulation of these inflammatory genes by Jun was not dependent on its self-expression levels but was likely achieved by altering chromatin accessibility.

a, Motif enrichment analysis of MAEC genomic regions in WD-sensitive domains. b, Volcano plot depicting results from TOBIAS. The orange dots depict binding motifs that are enriched and have TF footprints in WDM-CDO or WDM-WDO MAECs, whereas the green dots depict motifs that are enriched and have TF footprints in CDM-CDO or CDM-WDO MAECs. c, Aggregate ATAC-seq footprints of the Jun motif in CDM-CDO (green) and WDM-CDO (orange) MAECs. Negative Tn5 insertions represent protection due to putative protein binding. d, Aggregate ATAC-seq footprints of the Jun motif in CDM-WDO (green) and WDM-WDO (orange) MAECs. Negative Tn5 insertions represent protection due to putative protein binding. e, CUT&RUN–qPCR analysis showing the enrichment of Jun at Tnf in MAECs from all four groups (n = 6). f, Heatmaps showing H3K27ac signals in the indicated four groups. The signal strengths are denoted by color intensities. g, Average plot of H3K27ac signals at Jun binding site in MDs in the indicated four group. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. Unpaired two-tailed subsampling test (b) and Student’s t-test (e) were used to determine statistical significance.

Source data

Histone 3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27ac), a marker that activates and enhances gene transcription, was involved in the formation of memory16,17. To explore the changes of H3K27ac in the MDs regulated by Jun, we found that H3K27ac modification of the Jun binding site increased in accordance with ATAC signal (Fig. 4f,g). These findings suggest that H3K27ac modification may be involved in the maintenance of inflammatory memory and indicate that AP-1 TFs play an important role in the epigenetic memory mediated by maternal WD feeding, affecting phenotypic differences in offspring by regulating the dynamic chromatin activity of offspring MAECs.

27-HC is a key factor in epigenetic memory establishment

Oxysterols, mainly derived from cholesterol-rich foods and the oxidation of cholesterol in the body, are considered to be the key pathogenic factors of atherosclerosis18. We hypothesized that changes in the content of certain oxysterols might be linked to epigenetic memory establishment in response to WD stimulus. We, therefore, performed metabolomic profiling studies targeting oxysterols in the plasma of maternal mice fed CD (M-CD) or WD (M-WD) during pregnancy and lactation. The score plot of the orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) and heatmap on the oxysterol showed significant changes in M-WD versus M-CD mice (Fig. 5a,b). Elevated plasma cholesterol levels in maternal and offspring mice were measured in WD-fed mice (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). The levels of 27-HC showed a greater than two-fold change in the plasma between these two groups (Fig. 5c). Additionally, the plasma content of 27-HC in WDM mice (freshly weaned mice) was significantly higher than in CDM mice (Fig. 5d). In addition, compared to CDM MAECs, the expression of Tnf, Nlrp3 and Ccl3 was significantly increased in WDM MAECs (Extended Data Fig. 5c).

a, OPLS-DA score plot based on targeted oxysterol metabolomic studies of maternal mice fed CD (M-CD, n = 6) and fed WD (M-WD, n = 10). PCo, orthogonal principal component. b, Heatmap showing the relative concentration for various metabolites. Each column represents the relative concentration of plasma metabolites, which is normalized to the mean value of M-CD. Degree of FC is indicated by color/shading. 24-, 25- and 27-HC, 24-, 25- and 27-hydroxycholesterol; 4B, 4β-hydroxycholesterol; 7A, 7α-hydroxycholesterol; 7B-HC, 7β-hydroxycholesterol; 7-Ket, 7-ketocholesterol; 22-B, 22β-kydroxycholesterol; DOC, deoxycorticosterone; DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate. c, Bubble plot showing the FC (M-WD/M-CD) of the specified oxysterols (n = 6 versus 10). d, Relative plasma levels of 27-HC in female and male CDM and WDM mice (n = 6). e, Schematic showing the experimental strategy. f, Representative images of female offspring mice arterial tissues isolated to examine atherosclerotic lesions after 3 weeks post-ligation. Scale bar, 2 mm. g,h, Representative H&E staining images (g) and quantification of lesion areas (h) in ligated LCA sections. Dashed orange boxes represent LCA (n = 6; scale bar, 100 μm). i,j, Relative plasma Tnf (i) and Ccl3 (j) levels in CDM-WDO and WDM-WDO Ldlr−/− mice administered subcutaneously with Vec or CT (n = 6). k, Plasma levels of TG, CHO, LDL-C and HDL-C in female mice at 11 weeks of age for four groups (n = 6). Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (d) and ordinary two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (h–k) were used to determine statistical significance. PC, principal component; w, weeks old.

Source data

To test the effect of 27-HC in this process, a Cyp27A1 inhibitor, CT, was used (Extended Data Fig. 5d). Four groups of mice were subcutaneously administrated either hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin (Vec) or CT (130 mg kg−1 d−1) during pregnancy and lactation (Fig. 5e). CT significantly reversed the WD-induced increase in plasma 27-HC levels in both the dams and their offspring (Extended Data Fig. 5e,f). After 5 weeks of CD feeding, the offspring of dams from the four groups were subjected to partial ligation of the LCA and were fed WD for another 3 weeks after the operation (Fig. 5e). Atherosclerotic lesions and plaque areas were robustly reduced in the LCAs of female and male offspring from WD-exposed dams treated with CT, compared to the observation after Vec treatment, but not in CD-exposed dams (Fig. 5f–h and Extended Data Fig. 5g–i). In addition, the plasma Tnf and Ccl3 contents were significantly decreased (Fig. 5i,j and Extended Data Fig. 5j,k). The plasma TG, CHO, HDL-C and LDL-C levels were similar among the four groups (Fig. 5k and Extended Data Fig. 5l). Taken together, we confirmed that 27-HC plays an important role in the establishment of epigenetic memory and the development of atherosclerosis.

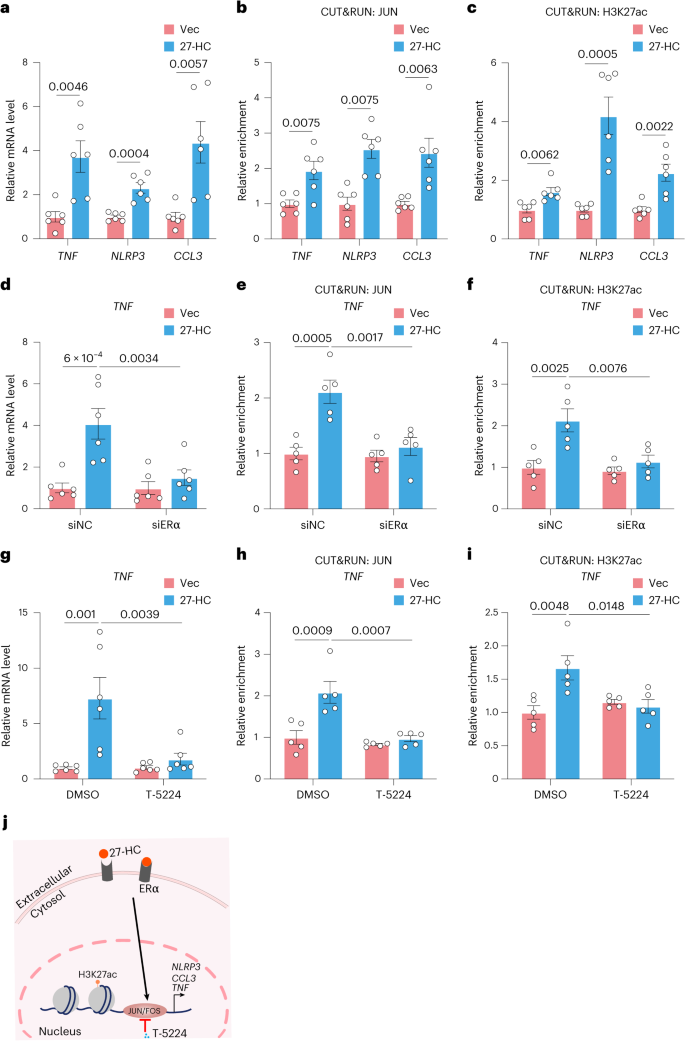

To further explore whether endothelial function is affected by 27-HC stimulation in vitro, we treated human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) with 20 μM 27-HC for 24 hours, finding that the mRNA levels of TNF, NLRP3 and CCL3 were significantly increased (Fig. 6a). JUN binding to TNF, NLRP3 and CCL3 also increased significantly after 27-HC treatment (Fig. 6b). Similarly, 27-HC treatment increased H3K27ac enrichment on the gene bodies of TNF, NLRP3 and CCL3 in HUVECs (Fig. 6c). This suggests that 27-HC may contribute to inflammatory memory, which manifested as the increased binding of AP-1 TF to target genes and H3K27ac modification.

a, Relative mRNA levels of TNF, NLRP3 and CCL3 in HUVECs treated with DMSO (Vec) or 27-HC (20 μM) (n = 6). b, CUT&RUN–qPCR analysis showing the interaction of JUN with the gene bodies of the indicated genes in HUVECs treated with Vec or 27-HC (n = 6). c, CUT&RUN–qPCR analysis showing H3K27ac enrichment at these three genes in HUVECs treated with Vec or 27-HC (n = 6). d, Relative TNF mRNA levels in HUVECs treated with siNC or siERα with or without 27-HC treatment (n = 6). e,f, CUT&RUN–qPCR analyses showing the enrichment of JUN (e) and H3K27ac (f) at TNF in HUVECs treated with siNC or siERα with or without 27-HC treatment (n = 5). g, Relative TNF mRNA levels in HUVECs treated with DMSO or T-5224 (20 μM) with or without 27-HC treatment (n = 6). h,i, CUT&RUN–qPCR analyses showing the enrichment of JUN (h) and H3K27ac (i) at TNF in HUVECs treated with DMSO or T-5224 with or without 27-HC treatment (n = 5). j, Schematic diagram of 27-HC-mediated epigenetic changes via ERα. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (a–c) and ordinary two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (d–i) were used to determine statistical significance.

Source data

Yu et al.19 proposed that 27-HC specifically targets endothelial estrogen receptor α (ERα) in vivo, increasing endothelial activation and atherosclerosis severity. To understand whether ERα was involved in the 27-HC-induced inflammatory memory process, we transfected small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting ERα (siERα) into HUVECs. We confirmed that ERα knockdown in HUVECs blocked the elevated expression of inflammatory cytokines induced by 27-HC (Fig. 6d and Extended Data Fig. 6a). As expected, the enrichment of JUN and H3K27ac on target genes (TNF, NLRP3 and CCL3) was significantly attenuated in ERα-knockdown ECs with 27-HC treatment (Fig. 6e,f and Extended Data Fig. 6b,c).

T-5224, a small non-peptide molecule, can bind to the DNA-binding domain of the FOS–JUN dimer, hindering its binding to DNA and inhibiting its role as a TF20. qPCR and CUT&RUN–qPCR analyses showed that treatment with this AP-1 inhibitor significantly downregulated the 27-HC-induced expression of TNF, NLRP3 and CCL3 and the occupation of JUN and H3K27ac on these three genes (Fig. 6g–i and Extended Data Fig. 6d–f). As shown in Fig. 6j, 27-HC induces AP-1-regulated epigenetic changes in ECs through ERα.

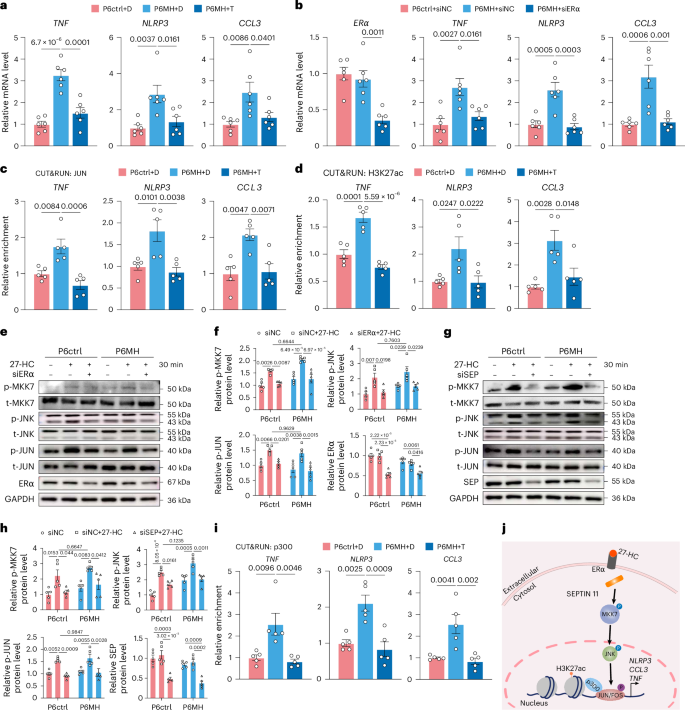

Maternal hyperlipidemia HUVECs possess inflammatory memory

To further explore the influence of maternal WD on offspring in vitro, we isolated ECs from the umbilical cords of pregnant women with or without maternal hyperlipidemia (MH). Clinical characteristics of the controls and patients with MH are shown in Supplementary Table 1. We conducted qPCR analysis at passages 1 and 6. The mRNA levels of TNF, NLRP3 and CCL3 in MH HUVECs at passage 1 (P1MH) were significantly higher than those in control HUVECs (P1ctrl), but, at passage 6 (P6MH), these levels had returned to a baseline similar to P1ctrl and P6ctrl (Extended Data Fig. 7a). However, JUN enrichment at TNF, NLRP3 and CCL3 also increased significantly at both P1MH and P6MH (Extended Data Fig. 7b).

We next sought to test whether 27-HC has an important function in facilitating chromatin remodeling by recalling inflammatory memory. We treated P6ctrl and P6MH with 27-HC, finding that the mRNA levels of TNF, NLRP3 and CCL3 were significantly higher in the treated P6MH than in the controls (Fig. 7a,b). JUN and H3K27ac were also more enriched on the binding motifs of these three genes (Fig. 7c,d and Extended Data Fig. 7c,d). Unsurprisingly, T-5224 treatment or ERα knockdown significantly inhibited 27-HC-induced gene expression and JUN and H3K27ac enrichment at these genes (Fig. 7a–d and Extended Data Fig. 7c,d). These findings were also confirmed at the protein level using ELISA and western blot assays (Extended Data Fig. 7e,f).

a, In the presence of 27-HC, relative mRNA levels of TNF, NLRP3 and CCL3 in Ctrl and MH HUVECs treated with DMSO (D) or T-5224 (T) (n = 6). b, In the presence of 27-HC, relative mRNA levels of TNF, NLRP3 and CCL3 in Ctrl and MH HUVECs treated with siNC or siERα (n = 6). c,d, In the presence of 27-HC, CUT&RUN–qPCR analyses showing the enrichment of JUN (c) and H3K27ac (d) at TNF, NLRP3 and CCL3 in Ctrl and MH HUVECs treated with DMSO (D) or T-5224 (T) (n = 5). e, Representative western blot of p-MKK7, t-MKK7, p-JNK, t-JNK, p-JUN, t-JUN, ERα and GAPDH in Ctrl and MH HUVECs treated with siNC or siERα with or without 27-HC treatment (n = 5). f, Quantification protein levels of p-MKK7 (normalized to t-MKK7), p-JNK (normalized to t-JNK), p-JUN (normalized to t-JUN) and ERα (normalized to GAPDH) in Ctrl and MH HUVECs treated with siNC or siERα with or without 27-HC treatment (n = 5). g, Representative western blot of p-MKK7, t-MKK7, p-JNK, t-JNK, p-JUN, t-JUN, SEPTIN 11 (SEP) and GAPDH in Ctrl and MH HUVECs treated with siNC or siSEPTIN 11 (siSEP) with or without 27-HC treatment (n = 5). h, Quantification protein levels of p-MKK7 (normalized to t-MKK7), p-JNK (normalized to t-JNK), p-JUN (normalized to t-JUN) and SEP (normalized to GAPDH) in Ctrl and MH HUVECs treated with siNC or siSEP with or without 27-HC treatment (n = 5). i, In the presence of 27-HC, CUT&RUN–qPCR analyses showing the enrichment of p300 at TNF, NLRP3 and CCL3 in Ctrl and MH HUVECs treated with DMSO (D) or T-5224 (T) (n = 5). j, Schematic diagram of 27-HC-mediated inflammation via ERα–SEPTIN 11–MKK7–JNK–JUN axis in Ctrl and MH HUVECs. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. Ordinary one-way ANOVA (a–d) and two-way ANOVA (f and h) with Sidak’s multiple comparison test were used to determine statistical significance. Ctrl, control.

Source data

Oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL), a key component in hypercholesterolemic serum, is thought to act as a stimulus in inflammatory memory, driving chromatin landscape remodeling13,21. We, therefore, investigated whether ox-LDL could play the same role as 27-HC in inducing inflammatory memory production. Accordingly, the mRNA levels of TNF, NLRP3 and CCL3 and the enrichment of JUN on these genes were increased more prominently in P6MH after ox-LDL stimulation compared to P6ctrl (Extended Data Fig. 7g,h). We also observed that these elevated TF binding and transcription levels caused by inflammatory memory were significantly repressed by T-5224 treatment (Extended Data Fig. 7g,h).

27-HC activates endothelial inflammation through the dissociation of the cytoplasmic scaffold protein SEPTIN 11 from ERα, which further activates the JNK pathway19. Is this the mechanism by which 27-HC induces inflammatory memory in MH HUVECs? We found that the MKK7-dependent JNK pathway was activated similarly by 27-HC in P6ctrl and P6MH, including the increase in MKK7 phosphorylation, JNK-Thr183/Tyr185 phosphorylation and JUN-Ser63 phosphorylation; moreover, this change was reversed by knockdown of ERα and SEPTIN 11 (Fig. 7e–h). These data suggest that 27-HC activates inflammation by activating the MKK7-dependent JNK–JUN signaling pathway, but this pathway is not associated with inflammation memory in MH HUVECs.

p300 is a classic histone acetyltransferase that catalyzes the acetylation of H3K27 and is an important regulator of EC homeostasis22. Previous reports also show that p300 interacts with JUN23. Our data validated the interaction between p300 and JUN, and this interaction was amplified after treatment with 27-HC (Extended Data Fig. 7i). We also further verified the increased enrichment of p300 in MH HUVECs, which was inhibited by T-5224 (Fig. 7i).

These data validate the existence of inflammatory memory in HUVECs from patients with MH and indicate that a more excessive inflammatory response occurs in these cells when they are given a second stimulus. Moreover, 27-HC mediated inflammation response regulated by the ERα–SEPTIN 11–MKK7–JNK–JUN axis (Fig. 7j).

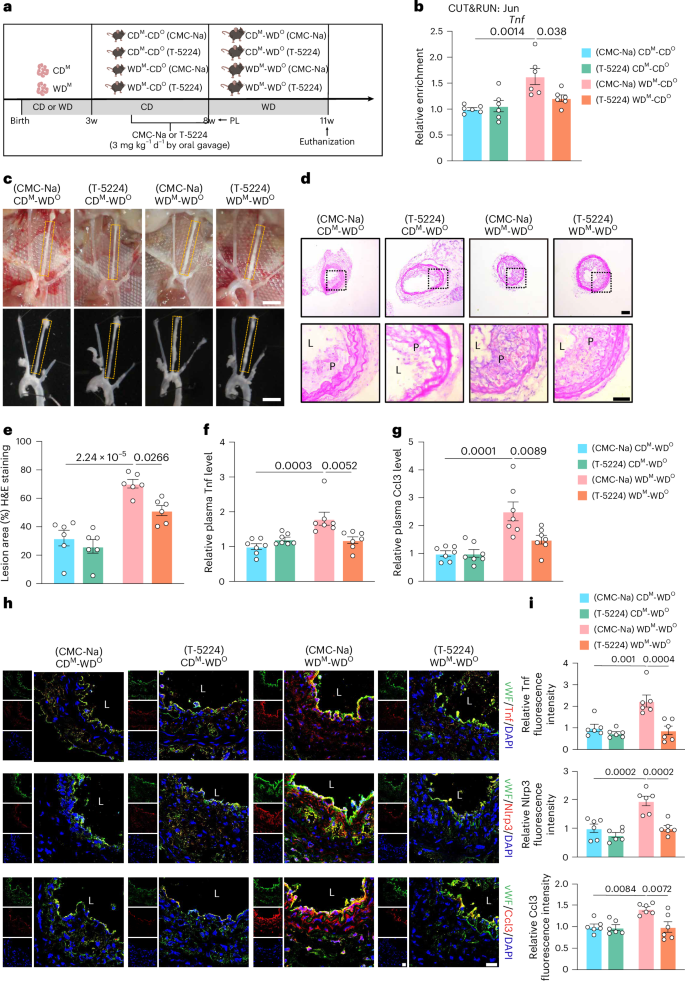

T-5224 impairs epigenetic memory and alleviates atherosclerosis

To further investigate the role of AP-1 TFs in accelerating atherosclerosis in the offspring of maternal WD Ldlr−/− mice, we administered carboxymethyl (CMC)-Na or T-5224 intragastrically to offspring of maternal WD and CD for 4 weeks starting at the age of 4 weeks and isolated MAECs at 8 weeks of age (Fig. 8a). Jun binding on the Tnf chromatin region was significantly lower in T-5224-treated versus CMC-Na-treated WDM-CDO MAECs (Fig. 8b). Plasma Tnf and Ccl3 levels of 8-week-old mice were detected by ELISA, and no significant difference was observed among the four groups (Extended Data Fig. 8a,b).

a, Schematic showing the experimental strategy. b, CUT&RUN–qPCR analysis showing the enrichment of Jun at Tnf in MAECs from CDM-CDO and WDM-CDO mice administered intragastrically with CMC-Na or T-5224 (3 mg kg−1 d−1) (n = 6). c, Representative images of arterial tissues isolated to examine atherosclerotic lesions after 3 weeks post-ligation. Scale bar, 2 mm. d,e, Representative H&E staining images (d) and quantification of lesion areas (e) in ligated LCA sections. Dashed orange boxes represent LCA (n = 6; scale bar, 100 μm). f,g, Relative plasma Tnf (f) and Ccl3 (g) levels in CDM-WDO and WDM-WDO Ldlr−/− mice administered intragastrically with CMC-Na or T-5224 (n = 7). h, Representative immunofluorescence staining of Tnf (upper panels), Nlrp3 (middle panels) and Ccl3 (lower panels) in LCAs from CDM-WDO and WDM-WDO Ldlr−/− mice administered intragastrically with CMC-Na or T-5224 (Tnf, Nlrp3 and Ccl3, red; vWF, green; DAPI, blue; scale bar, 40 μm; L, lumen). i, Quantitative analysis of the fluorescence intensities of Tnf (above), Nlrp3 (middle) and Ccl3 (below) in ECs (n = 6). Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. Ordinary two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test was used to determine statistical significance. w, weeks old.

Source data

We next performed partial ligation of the LCA in the four groups of 8-week-old mice treated by gavage as described above and fed mice with WD for 3 weeks (Fig. 8a), and the degree of atherosclerotic lesions and the plaque area were robustly reduced in the LCAs from T-5224-treated versus CMC-Na-treated WDM-WDO mice (Fig. 8c–e). ELISA analyses also demonstrated significantly lower protein levels of Tnf and Ccl3 in the plasma of T-5224-treated versus CMC-Na-treated WDM-WDO mice (Fig. 8f,g). Plasma TG, CHO, HDL-C and LDL-C levels were similar among the four groups (Extended Data Fig. 8c). Finally, we performed immunofluorescence staining on the LCA sections, finding that T-5224 treatment eliminated the inflammatory memory caused by the increased expression of Tnf, Nlrp3 and Ccl3 induced by maternal WD (Fig. 8h,i). Together, these data provide convincing evidence that the AP-1 inhibitor T-5224 can reduce maternal WD-induced epigenetic memory and mitigate the development of atherosclerosis in offspring.

Discussion

Together, these data show that the intake of WD during gestation and nursing had a lasting influence on the susceptibility of offspring to atherosclerosis, confirming the role of epigenetic inflammatory memory. In this study, we used two methods to induce the atherosclerosis model—namely, LCA partial ligation combined with short-term WD induction24 and long-term WD induction. The phenotypes of these two models were consistent, and both promoted the progression of atherosclerosis in offspring. Through bioinformatics analysis of MAECs, we highlighted that MAECs were endowed with inflammatory memory and pointed to the involvement of the TF AP-1 in the regulation of these memory domains. We also demonstrated that the AP-1 inhibitor T-5224 mitigated the susceptibility of offspring to atherosclerosis by suppressing the DNA binding activity of the Fos–Jun dimer. Notably, oxysterol-targeting metabolomics and ELISA assay demonstrated that 27-HC was involved in memory establishment. Simultaneously, it amplified TNF, NLRP3 and CCL3 expression and raised the deposition of AP-1 and H3K27ac in the binding domain. Reducing 27-HC levels or inhibiting the formation of inflammatory memory offers a potential strategy to mitigate and reverse the harmful effects of maternal WD exposure on offspring (Extended Data Fig. 9a).

Through SMART-seq analysis, we found that gene expression levels in MAECs from WDM-CDO mice were not significantly different from MAECs from CDM-CDO mice. However, when these offspring were re-exposed to WD later in life, the expression levels of genes associated with inflammatory responses, monocyte migration, lipids and atherosclerosis changed more substantially in offspring previously exposed to WD via maternal diet. We speculate that the reason for this stronger response after secondary stimulation is due to the immune memory produced by MAECs. The biological responses to WD and inflammatory memory have been widely reported in a variety of cells, including hematopoietic stem cells, granulocyte/macrophage progenitors21 and myeloid cells13. It has been recognized that immune memory exists not only in the adaptive immunity but also in innate immune cells, such as macrophages, ECs, monocytes and natural killer (NK) cells14,25,26. In our studies, we have focused on deciphering the inflammatory effects of WD in the early, initiation phase of atherosclerosis before significant amounts of plaque have deposited in the vessel walls in Ldlr−/− mice. ox-LDL is known to regulate pro-inflammatory memory via mTOR–HIF1α signaling in human aortic ECs27. Another study28 emphasized the role of the bacterial endotoxin lipopolysaccharide in inducing immune tolerance in HUVECs and the potential use of monophosphoryl lipid A, an endotoxin derivative, to induce training tolerance as a therapeutic to suppress innate immune inflammation. These findings highlight the role of ECs in immune memory and inflammatory responses.

Our analysis showed that WD-exposed MAECs increased the accessibility of many genes that tend to activate ECs more quickly under secondary stimulation. We identified the TF AP-1 as a key mediator of long-term epigenetic memory in MAECs, as indicated by the opening of WD-induced chromatin regions. In addition to regulating transcriptional activation, AP-1 has been linked to many aspects of chromatin biology29,30. Its importance is underscored in epithelial barrier tissues at each step of inflammatory memory—establishment, maintenance and recall17. Consistent with our findings, MDs showed an increased occupation of AP-1 motifs and a strongly enriched differential binding score of the Fos and Jun footprint.

ox-LDLs are rich in oxysterols, the oxidation products of cholesterol. Several oxysterols have been shown to accumulate in atherosclerotic plaques18,31,32 and to play a key role in maintaining the cardiovascular system33. Although the placenta is clearly impermeable to cholesterol-carrying LDL particles, the process of placental cholesterol transport was identified during a specific stage of pregnancy34,35,36. Certainly, our data also confirmed the similar changes in plasma 27-HC content between maternal and fetal in metabolomics analyses of targeted oxysterols and the ELISA assay. 27-HC is one of the most represented oxysterols in the peripheral blood of healthy individuals37. It is produced from cholesterol catalyzed by the sterol hydroxylase CYP27A1 and is abundant in the liver38. Several studies found that ERα mediates the pro-atherogenic effects of 27-HC and that CYP27A1 inhibition causes decreased 27-HC content and retards atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice18,19. In our model, 27-HC is a key metabolite mediating inflammatory memory; deletion of ERα or treatment with T-5224 abrogates AP-1 TF binding to memory domains and, thereby, blocks the process of 27-HC-induced inflammatory memory.

The activating histone marker H3K27ac is deposited during the initial inflammatory response and is often retained at memory domains39, and the acetyltransferase p300 is widely involved in H3K27ac formation40. Masayuki et al.41 suggested that AP-1 drives macrophage reprogramming accompanied by recruitment of p300 to the target gene and significant increased H3K27ac modification, leading to higher activation of transcription. In the present study, we observed that AP-1-promoted inflammatory memory is accompanied by deposition of H3K27ac in MAECs and HUVECs. In vitro, the increased expression of JUN with 27-HC stimulation and the enhanced interaction between p300 and JUN highlight that p300 is involved in this process.

A recent clinical cohort study of children with and without congenital heart disease also highlighted the pathogenic programming effect of MH42. Children with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia who are maternally inherited have higher cardiovascular mortality than those who are paternally inherited, due to in utero exposure to maternal cholesterol levels43. Treatment of hypercholesterolemic mothers with antioxidant or lipid-lowering medications in preclinical models may attenuate maternal diet-induced hypercholesterolemia and reduce the increase in fetal atherosclerotic lesion formation44,45. Considering the side effects of medication during pregnancy, we take another perspective: that prevention of atherosclerosis via targeting of epigenetic inflammatory memory may be an effective way to eliminate memory-induced atherosclerosis exacerbation.

Methods

Human studies

The umbilical cords were obtained from 11 hyperlipidemic and 15 normolipidemic pregnant women. Clinical characteristics of patients are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Written consent was obtained from every patient and from the families of the control donors. The patients consented to the collection of umbilical cords to be used for research purposes; they also consented to the data generated from such research to be published. No participant compensation was provided. The procedure was approved by the Ethics Committee of Experimental Research at Tianjin Medical University General Hospital (IRB2020-KY-102) and Beijing Anzhen Hospital of Capital Medical University (KS2024023).

Animal studies

Ldlr−/− mice (C57BL/6) were purchased from GemPharmatech. Eight-week-old female Ldlr−/− mice were mated with 8-week-old male Ldlr−/− mice. After mating, pregnant dams were housed single or alone with their litter and switched to WD (42% kcal fat, 42.7% kcal carbohydrate, 15.2% kcal protein; Envigo, TD88137) or CD (Beijing Sibeifu Biotechnology, SPF-F02-002) during pregnancy and lactation. The female and male offspring were weaned after 3 weeks, fed a CD until 8 weeks and then fed a WD for the following 8 weeks. As a Cyp27A1 inhibitor, GW273297X is not commercially available46; its analog (R)- 4-((5R, 7R, 8R, 9S, 10S, 13R, 14S, 17R)-7-hydroxy-3, 3-dimethoxy-10,13-dimethylhexadecahydro-1H-cyclopenta [a] phenanthren-17-yl) pentyl 4- methylbenzenesulfonate (named compound TMU; CT) was used to reduce the 27-HC content (Supplementary Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 5d). Mice were kept under a 12-hour light/dark cycle at 23 °C and humidity at 50 ± 15% with ad libitum access to food and water. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Tianjin Medical University (TMUaMEC2021014).

Cell culture

The umbilical cord filled with trypsin was placed in a large beaker containing HEPES buffer and digested at 37 °C for 8 minutes. This cell-containing trypsin solution was mixed with an equal volume of M199 medium and centrifuged at 100g for 5 minutes. Next, the supernatant was discarded, and the cells were re-suspended and cultured in 10-cm dishes coated with collagen (30 μg ml−1) beforehand. HUVECs were isolated from the umbilical cords of pregnant women with or without hyperlipidemia—those with total cholesterol levels greater than 7.17 mmol L−1 in Tianjin Medical University General Hospital and Beijing Anzhen Hospital of Capital Medical University. Relevant patient blood lipid information is shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Atherosclerotic lesion analysis

Eight-week-old male and female offspring with CD or WD during maternal pregnancy and lactation were fed a WD for 8 weeks. We performed ORO staining on the entire aorta that was completely dissected to evaluate lipid accumulation and plaque area. The aortic root lesion area was embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound and immediately frozen. Eight slices of each mouse tissue were cut continuously, and 7-mm slices were prepared and placed on glass slides. Morphological damage analysis was performed by hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) staining; lipid deposition was evaluated by ORO staining; and collagen deposition was evaluated by Massonʼs trichrome staining. For immunostaining, aortic root sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, permeated with membrane permeation solution for 30 minutes and blocked with 5% goat serum for 1 hour at room temperature. The sections were incubated with the primary antibody (anti-CD68) (1:100) at 4 °C overnight. Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (1:200) was added, and images were acquired with a Zeiss LSM 900 laser confocal ultra-high-resolution microscope. ZEN version 2.3 software was used to capture immunfluorescence images. Quantitative analysis was performed using Image-Pro Plus (version 6.0; Media Cybernetics).

Carotid artery partial ligation model

The LCA of mice was partially ligated as previously described47. First, CDM-CDO and WDM-CDO mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (2–3%). A lateral incision (4–5 mm) was created along the left midline of the neck to expose the LCA. The superior thyroid artery was left intact, and the internal carotid, external carotid and occipital arteries were ligated. WD was fed immediately after surgery for 3 weeks.

High-resolution ultrasound measurements

Mice were anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane, and body temperature was maintained on a heated stage. Flow velocity in the carotid artery of the mice was evaluated by B-mode using the Vevo 2100 Imaging System (FUJIFILM VisualSonics). Levels of anesthesia, heart rate, temperature and respiration were continuously monitored during the ultrasound process.

Measurement of plasma lipids

Blood through a heart puncture was placed into heparin-coated tubes. Plasma was stored at −80 °C before analysis. TGs were analyzed by the glycerol-3-phosphate oxidase/phenol and aminophenazone (GPO-PAP) method. The level of total CHO was determined by the cholesterol oxidase/phenol and aminophenone (CHOD-PAP) method. LDL-C levels were determined by the direct surfactant removal method. HDL-C levels were measured using the direct catalase clearance method. All kits were purchased from BioSino Bio-Technology & Science.

IPGTT

Eight-week-old and 16-week-old male and female offspring with CD or WD during maternal pregnancy and lactation were fasted for 6 hours and then challenged with an intraperitoneal injection of glucose (2 g kg−1 body weight). Glucose was assessed at 0, 15, 30, 60, 90 and 120 minutes via tail vein bleeding by a glucometer (Roche Diagnostics, AccuChek Performa Monitor) in a quiet environment.

Isolation of MAECs

CDM-CDO, WDM-CDO, CDM-WDO and WDM-WDO group mice were euthanized, and aortic vessels were dissected. There were six mice in each group. Aortic cells were obtained using an enzymatic solution (125 U ml−1 collagenase type-XI, 60 U ml−1 hyaluronidase type I-s, 60 U ml−1 DNase I and 450 U ml−1 collagenase type-I; all enzymes were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich) at 37 °C for 1 hour and filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer as previously described48. The ECs were isolated by CD31 magnetic beads using MS separation columns (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-042-201) on an OctoMACS Separator (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-042-109).

Isolation and quantification of RNA (RT–qPCR)

Total RNA was obtained from vascular tissue sorting ECs and HUVECs by using the TransZol Up Plus RNA Kit (TransGen Biotech). Total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using EasyScript All-in-One First-Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, AE341-02) for qPCR. The mRNA levels were normalized by 18S and compared with the 2−ΔΔCt method. Gene expression was analyzed using SYBR Green reagent (Vazyme) on an ABI 7900HT Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies). The sequences of gene-specific primers for real-time PCR are shown in Supplementary Table 2.

SMART-seq preparation and analysis

Sorted ECs were added with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and then delivered on ice to LC-Bio Technologies Co., Ltd. for further SMART-seq analysis. The RNA libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform. Samples were quality controlled using FastQC (version 0.12.1) to remove low-quality reads. The adapters of raw reads were removed using Trim Galore (version 0.6.10). Paired-end reads of 150 base pairs (bp) were aligned to the GENCODE Mus musculus reference genome (build GRCm38/mm10) using HISAT2 (version 2.2.1). The SAM files were converted into BAM files by SAMtools (version 1.13). A table of raw read counts was then generated with featureCounts (version 2.0.1). Differential analysis of gene expression was performed using the R package DESeq2 (version 1.40.2), and significant differential genes were chosen based on adjusted P value (Padj) < 0.05 and |log2 fold change (FC)| ≥ 1. The R package ComplexHeatmap (version 2.16.0) was used to generate heatmaps.

ATAC-seq preparation and analysis

Detailed methods for ATAC library preparation were described previously49. In brief, a total of 1 × 105 ECs (cell viability > 80%) were lysed in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1% (v/v) IGPAL CA-630, 10 mM NaCl) for 10 minutes on ice, and the nuclei were applied to transposition with Tn5 transposase (Vazyme, TD501) for 30 minutes at 37 °C. After fragmentation of the product, DNA was purified with VAHTS DNA Clean Beads (Vazyme, N41101) for final library construction and high-throughput sequencing on the Illumina NovaSeq platform.

Samples were quality controlled using FastQC (version 0.12.1) to remove low-quality reads. The adapters of raw reads were removed using Trim Galore (version 0.6.10). Paired-end reads of 150 bp were aligned to the GENCODE Mus musculus reference genome (build GRCm38/mm10) using Bowtie 2 (version 2.4.5). The SAM files were converted into BAM files, and duplicate reads were removed by SAMtools (version 1.13). Mitochondrial genome reads were manually removed.

The genomic region was divided into several 500-bp bins, and the reads of each bin were counted as a table using deepTools (version 3.5.4), and the R package corrplot (version 0.92) was used for correlation analysis between samples. The BAM files with a correlation greater than 0.8 in the same group were merged by SAMtools (version 1.13). Peak detection was made on the merged BAMs using ‘-q 5e-2 -f BAMPE’ by MACS2 (version 2.2.9.1), and the peaks in the ENCODE mm10 blacklist were filtered out. deepTools (version 3.5.4) bamCoverage was used to generate BigWig files with reads per genome coverage (RPGC) normalization and presented by Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV, version 0.12.9) software.

Differential analysis of merged BAMs was performed with HOMER (version 4.11). WD-sensitive domains were ‘-P 0.0001 -F 1’; WD-suppressed domains were filtered by ‘-P 0.0001 -F 1 -rev’ in the WDM-CDO group versus the CDM-CDO group; and the remaining was unchanged domains. WD-sensitive domains were further divided into three clusters in the WDM-WDO group versus the CDM-WDO group, including module I filtered by ‘-P 1 -F 1 -rev’; the remaining was module II; and module III MDs were filtered by ‘-P 0.0001 -F 1.4’. Unchanged domains were also divided into three clusters in the WDM-WDO group versus the CDM-WDO group, including module V filtered by ‘-P 0.0001 -F 1.4 -rev’ and module VII filtered by ‘-P 0.0001 -F 1.4’, and the remaining was module VI.

CUT&TAG preparation and analysis

MAECs were isolated as described above. Then, cells (nuclei) were incubated with concanavalin A (ConA)-coated magnetic beads for 10 minutes. The beads were collected and incubated with primary antibody against H3K27ac (1:50) at 4 °C overnight. Corresponding secondary antibodies and pA/G-transposon (the transposon fused with Protein A/G) that could precisely target the DNA sequence near the target protein were added. When the transposon was cutting, adaptor sequences were added to both ends of the cleaved fragment. After PCR amplification, paired-end multiplexed libraries were sequenced using Illumina NovaSeq. For more details, see the manufacturer’s instructions (Vanzyme, TD903).

Samples were quality controlled using FastQC (version 0.12.1) to remove low-quality reads. The adapters of raw reads were removed using Trim Galore (version 0.6.10). Paired-end reads of 150 bp were aligned to the GENCODE Mus musculus reference genome (build GRCm38/mm10) using Bowtie 2 (version 2.4.5). The SAM files were converted into BAM files, and duplicate reads were removed by SAMtools (version 1.13). Mitochondrial genome reads were manually removed.

Peaks detected using ‘-q 5e-2 -f BAMPE’ by MACS2 (version 2.2.9.1) and the peaks in the ENCODE mm10 blacklist were filtered out. deepTools (version 3.5.4) bamCoverage was used to generate BigWig files with RPGC normalization and presented by IGV (version 0.12.9) software. Histone modification signal graphs were generated using deepTools (version 3.5.4).

Enrichment analysis

GO BP and KEGG pathway analysis were performed using the R package clusterProfiler (version 4.8.2).

Motif analysis

Motif enrichment of each module was performed with HOMER software (version 4.11).

TF footprinting

TF footprints were analyzed using TF occupancy prediction by investigation of ATAC-seq signal (TOBIAS, version 0.12.9). Merged BAMs were corrected for insertion bias of the Tn5 transposase with ‘+4/−5’. MDs were matched to the list of motifs in JASPAR 2022 database (version 0.99.8) with taxonomic group: vertebrates; collection: CORE. The signal plots were generated using the command PlotAggregate with ‘–log-transform–flank 100’. The top 5% and bottom 5% of motifs based on binding differential score and P value were considered significantly different.

CUT&RUN–qPCR

First, cells were bound by ConA Beads Pro. We used the primary antibodies (anti-cJun, anti-H3K27ac and anti-p300) against the target protein and the mediation of Protein G to make the pG-MNase enzyme precisely target the DNA sequence near the target protein, and qPCR was performed on the sequence to obtain the information of the interaction between the target protein and DNA through detection. Primer sequences used in this study are referred to in Supplementary Table 3. See the Hyperactive pG-MNase CUT&RUN Assay Kit for qPCR for detailed experimental procedures (Vazyme, HD101).

Immunofluorescence staining

In brief, LCA sections were fixed for 15 minutes and blocked for 30 minutes at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies (1:100) against CCL3, NLRP3, TNF and vWF. Corresponding Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit IgG and Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-sheep IgG secondary antibodies (1:200) were added, and images were captured using a Zeiss confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM 900).

ELISA

Mice plasma 27-HC levels were detected with a 27-HC ELISA kit (FineTest, EU2632) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Mice plasma Tnf levels were detected by ELISA (Elabscience, E-EL-M3063). Mice plasma Tnf levels were detected by ELISA (Elabscience, E-EL-M0007c). For examining the intracellular levels of TNF and CCL3, HUVECs were seeded in 12-well plates and were treated with 27-HC and T-5224 for 24 hours after serum starvation, after which the ECs were collected with cooled PBS containing protease inhibitors (Roche). The concentration was determined using a commercial ELISA kit (Elabscience, E-EL-H0109c and E-EL-H0021c), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell transfection

HUVECs were transfected with negative control siRNA (siNC), ERα siRNA and SEPTIN 11 siRNA using TransIntro EL Transfection Reagent (TransGen, FT201). siRNAs against negative control and ERα were obtained from Sangon Biotech, and sequences are shown in Supplementary Table 4.

Immunoprecipitation

Maternal control and MH HUVECs at passage 6 were washed with PBS and harvested in non-denatured lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors (Roche), phosphatase inhibitor (Roche, PhosSTOP) and PMSF (Solarbio Life Sciences) on ice. For immunoprecipitation, 500 μg of protein was incubated with 2 μg of specific antibodies against p300 overnight at 4 °C with constant rotation; 20 μl of 50% Protein A/G PLUS-Agarose beads (Invitrogen) was added for incubation at room temperature for 2 hours. Beads were then washed five times with the lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 1% Nonidet-P40, 0.1% SDS and 150 mM NaCl) containing 1% NP-40. After the final wash, the supernatant was centrifuged (2,000g) and discarded, and then the protein extract was mixed with SDS loading buffer, boiled for 5 minutes and subjected to immunoblotting.

Western blot analysis

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare, 10600001), which were incubated with primary antibodies against ERα (1:1,000), SEPTIN 11 (1:1,000), p300 (1:1,000), p-c-JUN (1:1,000), c-JUN (1:1,000), p-MKK7 (1:200), MKK7 (1:1,000), p-JNK (1:500), JNK (1:500), c-FOS (1:500), NLRP3 (1:1,000) and GAPDH (1:8,000) overnight at 4 °C, subsequently with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary goat anti-mouse or rabbit antibodies (1:5,000) for 1 hour at 25 °C. Proteins were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific) by a chemiluminescence system (Tanon).

Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry

Our targeted oxysterols assay in maternal plasma was performed by Shanghai Luming Biological Technology Co., Ltd. In general, 400 μl of methanol–dichloromethane solution (V(methanol):V(dichloromethane) = 65:35), containing 0.05 mmol L−1 BHT and isotope internal standard cholic acid-2,2,4, 4-D4 and [1,2-13C2]-glycine, was added to the appropriate samples. After vortexing for 1 minute, extraction was ultra-sonicated on ice for 10 minutes and rested at −20 °C for 30 minutes. After centrifugation for 10 minutes (13,800g, 4 °C), 400 μl of supernatant was taken and concentrated to dry. Then, the cells were sonicated and centrifuged again (13,800g, 4 °C). Next, 150 μl of the supernatant was sucked by a syringe, filtered using a 0.22-μm organic phase pinhole filter and transferred to liquid chromatography (LC) injection vials. In this experiment, the ultra-performance liquid chromatography with electrospray ionization and tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-ESI-MS/MS) analysis method was used to qualitatively and quantitatively detect the target metabolites. The MS peaks of each metabolite detected in different samples were manually corrected according to the retention time and peak type information of metabolites. The peak area of each chromatographic peak represented the relative content of the corresponding metabolites. MetaboAnalyst 6.0 (http://www.metaboanalyst.ca) was used for OPLS-DA and heatmap analysis. The data were log transformed and auto-scaled before analysis. Relative MS data are shown in Supplementary Data 1.

Statistics and reproducibility

For all experiments, effect sizes were estimated based on preliminary data, and the selected cohort sizes were sufficient to have a power of 0.8 at α = 0.05. Mice were randomized before their assignment to treatment groups. The analyses were performed in a blinded manner. GraphPad Prism (version 9.4.1) and ImageJ (version 2.16) software programs were used for statistical analysis. The Shapiro–Wilk normality test was used for all data with n ≥ 6. For normally distributed data, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to identify statistically significant differences between two groups, and two-way ANOVA or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to compare multiple groups. The Mann–Whitney U-test or the Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test, was used for non-normally distributed data when n < 6, where appropriate. Wherever possible, data are provided for technical replicates and individual mice and are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. Figure legends for each experiment indicate the statistical tests used. All bioinformatics analyses are described in their respective Methods sections.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses