Mechanistic links between intense volcanism and the transient oxygenation of the Archean atmosphere

Introduction

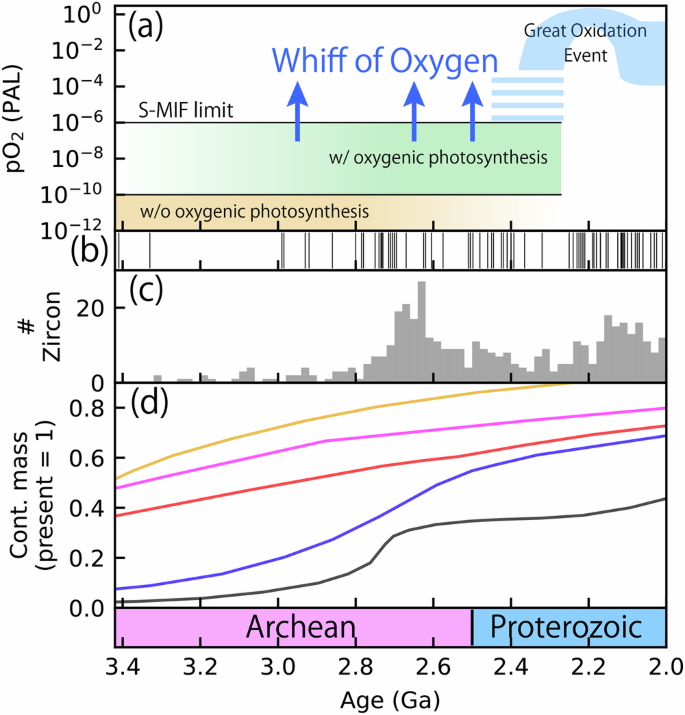

The evolution of the Earth’s atmosphere plays a crucial role in maintaining long-term habitability and shaping the coupled evolution of life and its environments. One of the most important aspects of the evolution of Earth’s atmosphere was the first substantial increase in the partial pressure of atmospheric oxygen (pO2) at ~2.5–2.2 Ga, known as the Great Oxidation Event (GOE) (Fig. 1a)1,2,3. Before the GOE, the atmospheric pO2 was much lower than the present atmospheric level (<10–6 PAL), as constrained by geological records of mass-independent isotope fractionation of sulfur (S-MIF)1,2,4,5. Across the GOE, atmospheric pO2 rose to ~10–4–10–1 PAL (Fig. 1a)1,6,7,8,9,10.

a The evolution of the atmospheric oxygen levels during the Archean and Paleoproterozoic. The blue-hatched area is the evolution model1,44. The blue arrows represent the timing of the whiff of oxygen11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. b Age distribution of the known large igneous provinces32. c Histogram of the U/Pb age of zircon particles72. d Estimated evolutionary models of the mass of the continent (red: Belousova et al.74; blue: Taylor and McLennan68; black: Condie and Aster73; orange: Pujol et al.75; pink: Dhuime et al.76).

Despite the protracted reducing conditions before the GOE, redox-sensitive element, and isotope records indicate the occurrence of transient oxygenation events in the ocean–atmosphere system, known as whiffs of oxygen events11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23 (Fig. 1). The most well-studied whiff is recorded in Mt. McRae Shale (Hamersley Basin, Australia) deposited at ~2.5 Ga (Fig. S1)11. Enrichment of molybdenum (Mo) and rhenium (Re) in the shale indicates a transient increase in atmospheric pO2 because Mo and Re are sourced from the oxidative weathering of continental sulfide minerals11,21. This view is further supported by the enrichment of selenium (Se), which also indicates the oxidative weathering of continental crusts19. During the whiff intervals, the marine sulfate (SO42–) concentrations likely increased owing to the oxidative weathering of sulfide minerals, promoting the development of local euxinia on continental margins23,24. Additionally, the osmium isotopic records in Mt. McRae Shale indicate a transient increase in oxidative weathering rate of continental sediments21. This whiff event would have persisted for several millions years to ~11 Myr (Fig. S1)11,23. During this event, a positive shift in δ15N suggests that the ocean was at least locally oxygenated18,23,25. Although the occurrence of whiffs is subject to vigorous debate26,27,28, the whiff event recorded in Mt. McRae Shale was also coeval with redox-sensitive elements enrichment in the Klein Naute Formation (South Africa)23,29, reinforcing the idea of the whiff of oxygen. Furthermore, recent phylogenic estimates place the emergence of oxygen-utilizing enzymes long before the GOE, supporting the presence of O2 during the late Archean30.

Large igneous provinces (LIPs), voluminous volcanic rocks formed by massive volcanic events, are a potential driver of global transient changes in the biogeochemistry of the ocean–atmosphere system31. The activity of LIPs is linked to upwelling mantle plumes that cause the extensive emplacement of magma32, leading to global warming through the release of vast amounts of greenhouse gases (e.g., CO2) into the atmosphere. It has been discussed that global warming associated with LIP eruptions during the Phanerozoic caused oceanic eutrophication by elevating the riverine input rate of nutrients. This, in turn, would have promoted primary productivity and O2 production in the euphotic zone, leading to excess organic matter production. The subsequent decomposition of organic matter would have caused oceanic deoxygenation due to the elevated oxygen demand33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40. Finally, the excess organic matter that was not decomposed in the water column would be buried in marine sediments, which is equivalent to the net oxygen production in the geological timescale, possibly causing the oxygenation of the atmosphere. This sequence of events is thought to have occurred repeatedly throughout the Phanerozoic (~0.54–0 Ga), sometimes causing biotic crises41.

Given the increase in biological productivity and O2 production in the euphotic zone during oceanic eutrophication, repeated LIP eruptions during the late Archean32 may have contributed to the occurrence of whiffs (Fig. 1b). The timing of the period of intense subaerial volcanism and the interval of the whiff22,42,43, together with the abundance of mercury (Hg) and its isotopic signatures, suggest that subaerial volcanism preceded the interval of the whiff22, implying close association between these phenomena. However, the biogeochemical consequences of LIP volcanism on the reducing environment on Archean Earth and its mechanistic link to the whiffs occurrence remain ambiguous due to the lack of a quantitative framework that allows for a comprehensive investigation of the coupled dynamics of the ocean–atmosphere–biosphere–climate during the Archean. Additionally, the impact of the long-term evolution of the Archean environment (e.g., continental growth) on the frequency and magnitude of the whiffs remains elusive.

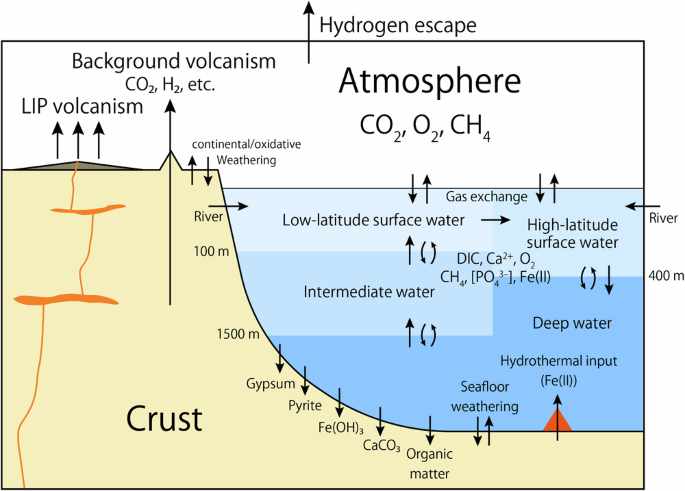

Here, we developed a theoretical model of the global C–P–S–Fe–O2–Ca biogeochemical cycles (Fig. 2; see Materials and Methods) to support the hypothesis that whiffs could be reasonably explained as the result of LIP eruptions. This model was based on the model used in the previous study44, in which we introduced the dynamical S cycles and C and S isotopes (δ13C and δ34S). The ocean–atmosphere system is represented by an atmospheric box, four ocean boxes, and a pore-space water box in oceanic crust (Fig. 2), with the marine S cycle represented by a single ocean box. The model simulates variations in atmospheric pCO2, pCH4, and pO2. In the ocean boxes, oceanic levels of dissolved inorganic C (DIC), carbonate alkalinity (Alkc), [PO43–], [SO42–], [Fe2+], [Ca2+], dissolved O2, and dissolved CH4. The behavior of DIC, Alkc, and [Ca2+] are also considered in the pore-space water box. Using this model, we simulate a transient response of the system to the injection of CO2 and reducing gases into the atmosphere assuming intense LIP-induced volcanism. Although the box modeling approach does not resolve spatial heterogeneity within the ocean for elements with short residence times, it is sufficient to simulate the long-term response of the biogeochemical cycle to the LIP-induced volcanism. This model was also used to quantify the conditions suitable for whiff occurrence on Archean Earth. The results demonstrate that the susceptibility of atmospheric O2 levels to LIP eruptions is closely related to continental growth.

The model consists of an atmospheric box, four ocean boxes, and a box representing the pore space in the oceanic crust.

Results

Eruption of a LIP causes a whiff of oxygen

To assess the biogeochemical impacts of LIP eruptions on the Archean Earth system, we ran the model under LIP eruptions with different total C influxes (Fig. S2). The maximum total C influx was set based on the case of intense volcanism that formed the Ontong Java Plateau, which is the largest Phanerozoic LIP known to have erupted in the Pacific Ocean during the Cretaceous. The eruption of the Ontong Java Plateau is known to have caused oceanic eutrophication and anoxia, and thus such a large-scale LIP eruption would potentially cause a whiff. We adopted a maximum estimate of the total CO2 influx from the Ontong Java Plateau45 as the maximum total C influx. We cannot rule out the possibility that the total C influxes from Archean LIPs were higher than this value. Nevertheless, we consider it unlikely that higher influx scenarios would dramatically alter our overarching conclusions. The intense volcanism is assumed to have continued for a period of 400 kyr in the standard case, which is also based on the estimated value for the case of the Ontong Java Plateau36, while the sensitivity of the results to different values of the duration of the volcanism (100–1000 kyr) is also tested. We also assumed a subaerial LIP eruption (i.e., CO2 and reducing gasses are injected directly into the atmosphere). Although a submarine eruption would have been more likely to occur during the Archean43, this assumption has only a minor impact on the results because the timescale for reaching equilibrium of gas exchange between the ocean and the atmosphere would be at most the timescale of the oceanic circulation (<~1000 years), which is sufficiently short.

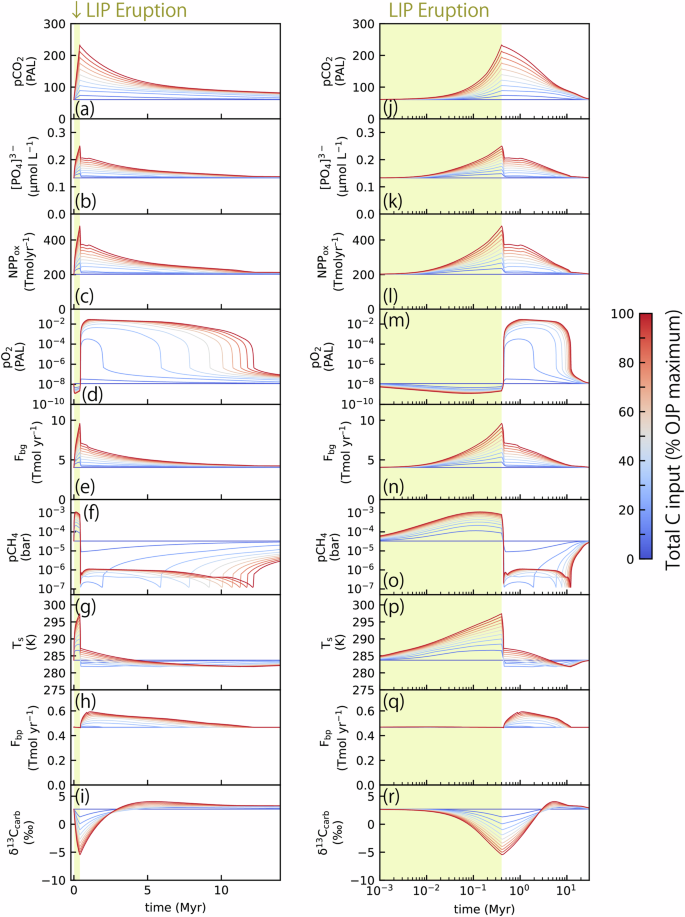

The result demonstrates that during LIP eruptions (yellow-hatched region in Fig. 3d), atmospheric pO2 levels slightly decrease from their initial values (pO2 ~ 10–8 PAL) owing to the influx of reducing gases into the atmosphere. After the cessation of LIP volcanism, atmospheric pO2 begins to increase as oceanic primary productivity increases. With a sufficient influx of total C, atmospheric pO2 exceeds the threshold value necessary for Mo supply from oxidative weathering (10–6.9 PAL), which corresponds to whiffs46. Specifically, when the total C influx is larger than ~20% of the maximum value, atmospheric pO2 exceeds the S-MIF limit and reaches ~10–4–10–2 PAL, which persists for several to ten million years (Fig. 3d). The atmospheric pO2 increases rapidly to this level owing to positive feedback caused by the self-shielding effect of O2 by its byproduct O347. This atmospheric pO2 is also beyond the threshold value necessary for oxidative weathering (10–6.9 PAL), which would sufficiently explain the enrichment of redox-sensitive elements that are hosted in sulfides during the whiffs interval12,24,46. The primary productivity required to trigger the whiffs (pO2 > 10–6.9 PAL) is ~270 Tmol C yr–1 (Fig. 3c), which is comparable to estimates required for triggering the GOE44,48. Increases in primary productivity are driven by elevated marine P concentration caused by enhanced supply of riverine P due to intensified continental weathering (Fig. 3b).

a Atmospheric pCO2, b [PO43–] in the deep ocean, c net primary production of oxygenic photoautotrophs (NPPox), d atmospheric pO2, e burial rate of organic carbon (Fbg), f atmospheric pCH4, g surface temperature (Ts), h burial rate of pyrite (Fbp), and i carbon isotope ratio of the burying carbonate (δ13Ccarb). The yellow-hatched region represents the interval of the eruption of LIPs. Different lines represent the different total C, H2, and S influxes given to the model (see Fig. S2). j–r Same as (a–i) but shown with the log-scaled x axis.

For the case with maximum C influx (red line in Fig. 3), atmospheric pCO2 level increases to ~230 PAL during intense volcanism. Following the cessation of volcanism, pCO2 gradually decreases over a period of >10 Myr. This timescale is relatively long compared with the perturbations caused by LIP eruptions during the Phanerozoic, which typically cease within several million years36,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60. This difference is caused by the low terrestrial weatherability during the Archean, i.e., the absence of land plants and small continental areas diminished the continental weathering efficiency61,62. In the Archean, weathering of seafloor basalt was likely the primary driver of climatic adjustment via carbonate–silicate geochemical cycles62,63,64,65. Despite the slow recovery of atmospheric pCO2, the surface temperature declines soon after the cessation of the LIP volcanism owing to the marked reduction in atmospheric pCH4 during the interval of whiffs. Following the cessation of LIP volcanism, marine P concentrations also decrease sharply, because the whiff of oxygen and oceanic oxygenation suppress the recycling of P from marine sediments (Fig. 3b). Marine P concentration then gradually declines following its removal via deposition of organic matter. Once marine P concentration falls below a critical value required for atmospheric oxygenation, atmospheric pO2 level decreases rapidly, returning to the Archean-like levels, consistent with predictions from a photochemical model66.

The duration of whiffs triggered by the LIP eruption typically spans several to ten million years (Fig. 3d). This timescale is primarily controlled by the timescale of the removal of atmospheric pCO2 via weatherings of continental and oceanic crusts. Because of the low terrestrial weatherability during the Archean, the residence time of CO2 was long, and CO2 injected from the intense volcanism was removed from the atmosphere via weatherings over a period of 1–10 Myr. Consequently, the rate of riverine P supply, marine P concentrations, and oxygen production rate to the atmosphere remain elevated over this timescale. The timescale for oxygen loss in the atmosphere during the whiffs would be shorter than the timescale of the excess oxygen production because it would be much shorter than the present-day residence time of ~1 Myr. Therefore, the timescale of the whiffs follows that of the P accumulation in the ocean after the LIP eruption.

Conditions for a whiff of oxygen

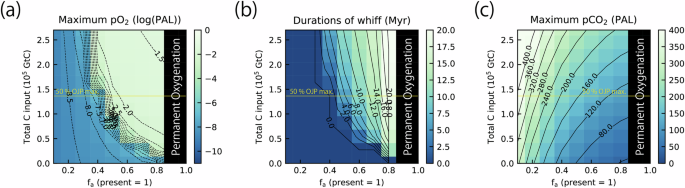

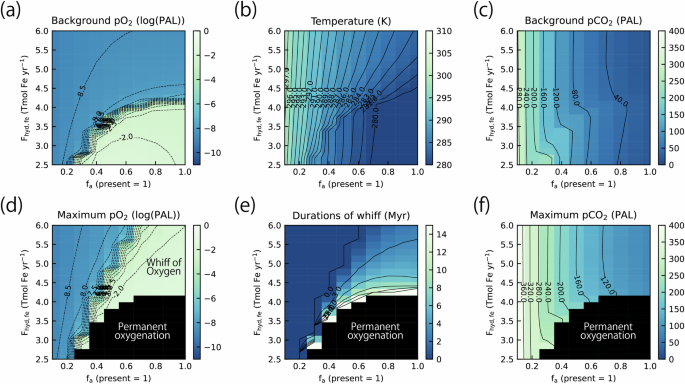

Our results indicate that whiffs can be triggered by the accumulation of P in the ocean following LIP volcanism, and therefore factors influencing the rate of riverine P supply would impact the conditions necessary for a whiff. The most critical factor is the areal fraction of the continent, as in the conditions of the GOE62,64, because it is a primary factor that affects the terrestrial weatherability in the absence of land plants. Results obtained using various continental areas and total C influxes are shown in Fig. 4. With a small continental area relative to that of the present (fa), the steady-state atmospheric pCO2 is ~290 PAL (Fig. S3a). With high total C input, atmospheric pCO2 increases to ~500 PAL after LIP eruptions. Despite this increase, marine P concentration changes only slightly due to low continental weathering rates, preventing whiff occurrence (Fig. 4a). As fa increases, the total C influx from the LIP eruptions required to trigger the whiffs becomes lower, making whiffs more likely than with the standard fa. Both the maximum pO2 achieved following LIP eruptions and the duration of the whiff increase with increasing fa. When fa is sufficiently large, background atmospheric pO2 level exceeds the S-MIF limit, corresponding to the GOE. The conditions for the GOE are affected by multiple factors, including fa and the influx of reducing power into the system44,48,62,64,67 (Fig. 5a).

The response of the maximum atmospheric pO2 (a), duration of the oxygenation (defined as duration with atmospheric pO2 over the minimum value for Mo supply from oxidative weathering (10–6.9 PAL)) (b), and the maximum atmospheric pCO2 (c) after the eruption of LIP as a function of the continental area relative to the present value (fa) and the total C input from the LIP volcanism (Exp2D_fa_TCO2 in Table S5). The yellow line represents the total C input of 50% of the maximum value for the Ontong Java Plateau (OJP).

The background atmospheric pO2 (a), surface temperature (b), the atmospheric pCO2 (c) at a steady state and the response of the maximum atmospheric pO2 (d), duration of the oxygenation (e), and the maximum atmospheric pCO2 (f) after the eruption of LIP as a function of the continental area and the hydrothermal input rate of Fe(II) (Exp2D_fa_Fhydfe in Table S5). The black-hatched area represents the condition for the permanent oxidation of the atmosphere (i.e., the GOE).

The conditions for whiffs are also affected by other factors controlling the global redox budget. The required influxes of hydrothermal Fe(II) and reducing gases from volcanoes for the whiffs are summarized in Fig. 5d and Fig. S4, respectively. This result also demonstrates that as fa increases, the range of the influx of reducing materials that allow whiff occurrence extends (Fig. 5a, b). When influxes of reducing materials decrease sufficiently, the GOE occurs. Therefore, whiffs likely indicate a gradual shift toward more oxidizing conditions in the ocean-atmosphere system during the Archean. Influxes of reducing materials from LIPs, however, do not strongly affect the conditions for whiffs (Figs. S5 and S6) because the timescale for the loss of the reducing gases from LIPs is shorter than the duration of the LIP eruptions (Fig. 3d). The condition for whiffs occurrence is also dependent on the duration of LIP eruptions (Fig. S7), but the dependence is considerably weak compared with that of the total C input because the timescale for the responses of oceanic eutrophication and the whiff of oxygen are longer than that of the LIP eruption. In summary, our results demonstrate that the total C influx from LIPs, continental area (fa), and the influx of reducing power (i.e., Fe(II) and reducing gases) are the critical factors for triggering whiffs.

Discussion

In this study, we assessed the impact of LIP volcanism on Archean biogeochemical cycles. The results demonstrated that intense volcanism associated with LIP emplacement could have caused transient oxygenation of the atmosphere lasting ~1–10 Myr. This timescale is consistent with the value of the Mt. McRae shale (<~11 Myr)11,23, which was estimated assuming a typical shale accumulation rate11, as well as the estimated maximum value of ~50 Myr for the whiff in the Jeerinah Formation, Australia, at ~2.66 Ga16. Our model also indicated that higher fa increases the susceptibility of the system to a whiff by increasing the P supply rate during the period with elevated atmospheric pCO2 caused by CO2 accumulation after LIP volcanism. During the mid-late Archean (3.5–2.5 Ga), the continental crust mass would have increased (Fig. 1d)68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78. This might have provided the backdrop to the transient oxygenation events in the late Archean, which would have ultimately contributed to the GOE44,62,64,70,79,80,81. The evolution of the continental crust was likely a critical step for the evolution of the atmosphere and biosphere during the late Archean and early Paleoproterozoic.

Even if the atmospheric pO2 exceeds the S-MIF limit transiently, it does not necessarily mean the disappearance of the S-MIF in geological records because S compounds with S-MIF signals would be continuously transported from the continental crust until it is completely lost, which is called the crustal memory effect82. When a whiff occurs, our model estimates that atmospheric pO2 level increases and could readily exceed ~10–4 PAL owing to positive feedback among atmospheric O2, O3, and CH447,83. In the Mt. McRae shale, on the other hand, negative S-MIF signals are observed during the interval of whiffs84, which seems not to be consistent with the high atmospheric pO2 simulated in our model. However, this inconsistency would be explained by the crustal memory effect because both physical and chemical weathering would have been very intense to transport the crustal S-MIF signals to the ocean under the conditions with elevated atmospheric pCO2 that followed the LIP volcanism. The impact of the crustal memory effect following LIP volcanism should be investigated to better constrain the maximum level of atmospheric pO2 during the whiffs. Alternatively, the S-MIF signals in the Mt. McRae shale may actually indicate that the atmospheric pO2 level might not have exceeded the S-MIF limit. This interpretation might not necessarily be inconsistent because some records suggest an increase in the rate of oxidative weathering, even with a level of atmospheric pO2 below the S-MIF limit28,46. This can still be explained by LIP eruptions with small total CO2 influxes, because the time required for returning to the background level of atmospheric pO2 following the LIP eruptions is very long (>10 Myr) even if a maximum level of pO2 is lower than the S-MIF limit owing to the low terrestrial weatherability as discussed above.

Although there is as yet no clear evidence linking LIP eruptions to whiffs of oxygen, the age distribution of known LIPs suggests that such eruptions were common during the late Archean (e.g., BLIP-1 at 2.505 Ga, Crystal Springs at 2.510 Ga, and Mistassini-Ptarmigan-Irsuaq at 2.51–2.50 Ga)32 (Fig. 1b). Additionally, Hg isotope signatures in the lower Mt. McRae Shale, which precedes the whiff in the upper Mt. McRae Shale, provide a temporal link between the whiff and the LIP volcanism22. The stratigraphic separation of these two signals is at least 20 m, most of which is covered by silicified ferroan carbonate22. The average sedimentation rate of the carbonate-bearing rocks in the Hamersley group is assumed to be 12 m Myr–1 22,85. With this assumption, the time lag between these two signals is ~1.7 Myr. This time lag could be explained if the timescale for the eruption of a LIP is comparably long because the supply of reducing gases from a LIP prohibits the occurrence of the whiff until the end of the eruption of a LIP.

The timing of both the onset of the GOE and the permanent oxygenation of the atmosphere has been actively discussed based on the presence or absence of S-MIF signals in geological records82,86,87,88. Indeed, there were LIP eruptions during the period of the GOE (Fig. 1b). Therefore, our result indicates that LIP eruptions could deviate the timing of the onset and the end of the GOE by causing whiffs of oxygen82,87,88,89. In other words, the occurrence of whiffs during the late Archean indicates that the redox budget of the ocean–atmosphere system was close to the tipping point for the GOE, beyond which the abrupt rise in atmospheric pO2 would take place.

As the system approaches the GOE tipping point, it becomes more vulnerable to environmental perturbations and variations. Consequently, transient oxidation may also result from natural fluctuations unrelated to LIP eruptions. For example, the global biogeochemical cycles can be fluctuated by variations of the orbital parameters as discussed in various ages of the Phanerozoic90,91,92,93,94 and/or a bolide impact event95,96. Although these potential perturbations may have contributed to causing the whiffs, these processes typically operate on timescales shorter than 1 Myr. In this light, the LIP eruption events have an advantage in explaining the long timescale of the whiffs inferred from the geological records.

When a whiff of oxygen occurs following LIP volcanism, our model expects a negative carbon isotope excursion (CIE), followed by a longer positive CIE due to oceanic eutrophication and extensive organic C burial in the ocean. This behavior is consistent with CIEs observed after the Phanerozoic LIP eruptions36,97. When the duration of LIP volcanism is relatively short (e.g., 400 kyr), the negative CIE caused by C accumulation during the LIP eruption would be more pronounced than the positive CIE (Fig. S7). A gradual transition to higher δ13C values after the whiff is recorded in the Mt. McRae shale, consistent with the model, although no clear negative CIE is observed. This can be explained by a prolonged LIP eruption, which would diminish the negative CIE while maintaining a similar positive CIE magnitude (Fig. S7). Additionally, carbonate and TOC records in the Mt. McRae shale exhibit characteristics similar to responses to Phanerozoic LIPs, suggesting global C cycle variations similar to those associated with Phanerozoic LIPs (Fig. S8). Our model further demonstrated that marine SO42– concentration increases when a whiff occurs after the LIP eruption because the oxidative weathering rate increased (Fig. S9c). Concurrently, [ΣH2S] also increases due to the enhanced microbial sulfate reduction (MSR) (Fig. S9d). Although our box model does not resolve local euxinic environments near continental margins, this is consistent with geological observations23. The model also demonstrated that S isotope excursions would be unlikely to be observed during the interval of a whiff caused by LIP volcanism because marine SO42– concentration during the whiff remains too low for the burial of gypsum (Fig. S9e). Our model also expects that increases in organic C and reactive P abundances would also be recorded during and after LIP eruptions. Further examination of these abundances during the whiffs would provide better verification of the link between LIP eruptions and whiffs occurrences expected based on this study.

The timing of the emergence of oxygenic photoautotrophs (OP), which would be a prerequisite for atmospheric oxygenation, is a subject of active debate. Some studies suggest that the emergence of OPs would have been immediately before the GOE26,98,99, inferring that the records of redox-sensitive elements during the whiff intervals may not reflect true atmospheric oxygenation. Although the present study does not rule out this possibility, the theoretical link between LIP eruptions and whiffs of oxygen supports transient atmospheric oxygenation11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19 and the emergence of OPs more than several hundred million years earlier than the GOE30. The transient atmospheric oxygenation might also have stimulated the evolution of life, including O2 detoxification mechanisms, which might have been a critical step in adapting to the increase in the atmospheric pO2 level across the GOE. Further investigation into the coevolution of the atmosphere, biosphere, and solid Earth during the late Archean and Paleoproterozoic would be fruitful for phylogenic, geological, and theoretical research.

Conclusion

Under a reasonable parameter set, our biogeochemical model indicates that a whiff of oxygen—a transient oxygenation event of the atmosphere during the late Archean—could have been triggered by intense volcanism caused by LIP emplacement. Our model explains the observed increases in atmospheric pO2 levels during the whiff intervals, as documented in geological records. The duration of a whiff is estimated at ~1–10 Myr, primarily influenced by the total amount of C supplied from LIPs and the extent of the continental area. The evolution of the continental crust during the Archean likely enhanced P supply following LIP eruptions, consistent with the occurrence of the whiffs during the late Archean. This suggests that the occurrence of the whiffs indicates that the late Archean Earth system was approaching the tipping point for a permanent rise in atmospheric pO2. The coupled dynamics of the atmosphere, biosphere, and continents, as recorded in the whiffs, would have been a fundamental step for the onset of the oxygenated world of early Earth.

Methods

Biogeochemical box model

We developed a biogeochemical box model that considers the biogeochemical cycles of C, P, S, Fe, O2, and Ca in the ocean–atmosphere system, which is an improved version of the previous study44. More specifically, the original model was improved by including the dynamical S cycles and C and S isotopes (δ13C and δ34S). The new model considers the dynamical responses of atmospheric CO2, CH4, and O2 concentrations, oceanic levels of DIC, carbonate alkalinity (Alkc), [PO43–], [SO42–], [Fe2+], [Ca2+], dissolved O2, and dissolved CH4, and DIC, Alkc, and [Ca2+] in the pore spaces of oceanic crust. Atmospheric budgets of O2, CH4, and CO2 via photochemical reactions are calculated using a parameterization created in the previous study47. The surface temperature is calculated using the temperature parameterization of Watanabe and Tajika64, which accounts for the greenhouse effects of CO2, H2O, CH4, and C2H6 based on the results of the radiative-convective climate models100,101. The atmospheric CO2 is removed via the weathering of the continental crust and the gas exchange with the ocean44.

The ocean is divided into a low-latitude surface ocean box (<100 m depth and 90% of the oceanic area), a high-latitude surface ocean box (<400 m depth and 10% of the oceanic area), an intermediate ocean box (100–1500 m depth below the low-latitude surface ocean box), and a deep ocean box44. The oceanic DIC is removed via the deposition of organic matter in the sediments and calcium carbonate in sediments and in the pore spaces of the oceanic crust. Marine phosphate is supplied via rivers and removed from the ocean via the deposition of organic matter and adsorption to Fe-bearing minerals and Ca-bound P burial. Marine Fe(II) is supplied via rivers and hydrothermal systems and removed from the ocean via the deposition of Fe(III) hydroxide and pyrite in sediments. The primary production in the ocean is driven by OP and Fe-(II)-based anoxygenic photoautotrophs (AP). O2 is produced in surface oceans by OPs and is partly consumed by methanotrophs and the oxidation of Fe(II), with the remaining O2 being outgassed into the atmosphere. CH4 is generated by the decomposition of organic matter through methanogenesis and is partly consumed by methanotrophs, with the remainder outgassed into the atmosphere. In this model, the activities of H2-based photoautotrophs and/or H2-/CO-consuming chemoautotrophs are not considered. Their activities would increase the primary productivity of APs under low atmospheric pO2 conditions48,102,103. If their activities are considered, the atmospheric pCH4 and the surface temperature under Archean-like low atmospheric pO2 conditions would likely increase. However, this would not strongly alter the fundamental behavior of the atmosphere–biosphere interactions after the eruption of LIPs and whiffs.

Carbon isotopes

The budget of 13C of the atmospheric CO2 and CH4 are represented as follows:

where μ is the number of moles in the present atmosphere (μ = 1.773 × 1020 mol); f13 represents the abundance of 13C relative to total C; f13,vc is f13 of the CO2 outgassing from the interior of the Earth; f13,wog is f13 of the sedimentary organic matter; the subscripts ↑ and ↓ represent the upward and downward counterpart, respectively; Foa,co2 is the gas exchange rate between the ocean and atmosphere; Fvc is the volcanic outgassing rate of CO2; Fwog is the oxidative weathering rate of sedimentary organic matters; Foxi is the oxidation rate of atmospheric CH4 to form CO2; Fesc is the consumption rate of atmospheric CH4 via H2 escape; and Fws and Fwc are the terrestrial continental weathering rate of silicates and carbonates. The budgets of 13C of the oceanic and pore-space DIC are represented as follows:

where the subscripts → and ← represent the fluxes from the low-latitude surface ocean box to the high-latitude surface ocean box and vice versa, respectively; farea is the areal fraction of the surface ocean box in total oceanic area; V is the volume of each ocean box; f13,borg and f13,pc are f13 of the organic matter and carbonate depositing in the ocean, respectively; f13,sedc is f13 of the terrestrial carbonates; f13,methano is f13 of CH4 produced via fermentation and methanogenesis; f13,bpyrsdc is f13 of the OC decomposed during the formation of pyrite in sediments; αm and αsd is the transfer efficiency of organic matter in the intermediate water box and deep ocean box below the low-latitude surface ocean box, respectively; Fdif and Fadv are the water exchange rate between ocean boxes via diffusion and advection; Fmet is the oxidation rate of CH4 by methanotrophs; Fdgc is the decomposition rate of organic matter in each ocean box; Fpc and Fdc are the formation and dissolution rates of CaCO3 in each ocean box; Fpo is the export production rate; Fbo is the burial rate of organic matter from each ocean box; FAOM is the abiotic oxidation rate of methane by marine sulfate; Fbpyr,sd,c is the rate of OC decomposition during the formation of pyrite in sediments. The budgets of 13C of the oceanic CH4 are represented as follows:

where Fdgch4 is the production rate of CH4 by methanogenesis.

Global sulfur cycle

We introduced the dynamical S cycle to the biogeochemical box model. The budgets of marine sulfate (SO42–), marine hydrogen sulfide (ΣH2S), crustal pyrite (Spyr), and crustal gypsum (Sgyp) are represented as follows:

where Fdpyr and Fdgyp are the outgassing rates of S from volcanos via metamorphic decompositions of pyrite and gypsum, respectively; Fwpyr is the oxidative weathering rate of sedimentary pyrite; Fwgyp is the weathering rate of sedimentary gypsum; Fdg,S is the decomposition rate of organic C by marine sulfate; FAOM is the rate of abiotic oxidation of methane (AOM) by marine sulfate; Foxhs is the oxidation rate of ΣH2S; Fbgyp and Fbpyr are the gypsum and pyrite burial fluxes from the ocean, respectively. The budgets of 34S are represented as follows:

where f34 represents the abundance of 34S relative to total S; and f34,bpyr represents f34 of pyrite formed in the ocean, respectively.

The burial of gypsum from the water column is assumed to occur in the low-latitude surface ocean box, as follows104,105,106:

where [SO42–]0 and [Ca2+]0 are the present oceanic concentration of sulfate and calcium ions, respectively, and kbgyp,0 is the rate constant for the burial of sedimentary gypsum. The buried gypsum enters the sedimentary gypsum reservoir. The sedimentary gypsum experiences metamorphism volcanism and provides S to the ocean–atmosphere system:

where rsp is the seafloor spreading rate relative to present, and kdgyp is the rate constant for the pyrite degassing. The weathering rate of sedimentary gypsum is represented as follows:

where Fwgyp,0 and Fws,0 are the present sedimentary gypsum and continental silicate weathering fluxes, and Sgyp,0 is the present sedimentary gypsum reservoir size.

The burial of pyrite is assumed to occur in the water column (Fbpyr,wc) and sediment (Fbpyr,sd):

The stoichiometric reaction for the pyrite formation in the water column is represented as follows:

The burial of pyrite from the water column (Fbpyr,wc) is estimated as follows107:

where kbpyr,wc is the rate constant for the burial of pyrite from the water column. For pyrite burial in sediments, on the other hand, we assumed that part of H2S originating from MSR in sediments deposits is pyrite. The stoichiometric reaction for pyrite formation in sediments is represented as follows:

The burial of pyrite in sediments is represented as follows:

where kbpyr,sd is the rate constant for the burial of pyrite in sediments and KMSR is the half-saturation constant for MSR. The net production rate of O2 via deposition of pyrite in the water column and sediments via the production of H2 can be represented in terms of the budget of O2 as follows:

where the first term of the right-hand side represents the net consumption of O2 via H2 produced by the production of pyrite in the water column via Eq. 24 and the second term represents the production of H2 in sediments via Eq. 26.

The buried pyrite enters the sedimentary pyrite reservoir. The sedimentary pyrite experiences metamorphism volcanism and oxidative weathering, whose rates are given as follows, respectively108:

where kdpyr is the rate constant for pyrite degassing, Fwpyr,0 is the present oxidative weathering flux of sedimentary pyrite, and Spyr,0 is the present sedimentary pyrite reservoir size. The stoichiometric reaction for pyrite degassing and oxidative weathering of pyrite is represented as follows:

The net effect of the metamorphic volcanism and oxidative weathering of pyrite on the global redox budget can be represented in terms of the consumption of O2, as follows:

LIP eruption scenario

For the standard scenario of volcanism after an eruption of LIPs, we assumed an eruption scenario of the Ontong Java Plateau that caused the deoxygenation of the ocean, the so-called ocean anoxic event 1a at ~120 Ma. For this standard scenario, we assumed a period of intense volcanisms of 400 kyr36 and a total C influx of 1021 g CO2 (~2.7 × 105 GtC) which is an estimated maximum value for the eruption of the Ontong Java Plateau45. The volcanic gases are supplied to the atmosphere at a constant rate over the period of the eruption of LIP, assuming the emplacement of LIP on continents. In reality, it is likely that the emplacement on the oceanic crust was more frequent than on continents considering the small mass of the continental crust. Nevertheless, this treatment would be sufficient for representing the response of the system at a timescale longer than the gas exchange between the atmosphere and the ocean. We assumed that the supply rate of reducing gas (represented by H2) relative to C from LIP volcanism (fred,lip) is constant throughout the LIP emplacement. Despite the uncertainty in fred,lip109,110, we set fred,lip to 0.36, which is equal to the relative supply rate of C and H2 in the background steady state of the model44. However, it has been discussed that the different pressure conditions owing to the different locations of the LIP emplacement result in different values of fred,lip43,111,112. The impact of the choice of fred,lip was investigated in Fig. S5 and S6. The supply of Fe(II) from the erupted silicate minerals on continents is not considered because we assumed a continental LIP eruption. Note that the supply of Fe(II) would affect the conditions for the occurrence of LIPs in the case of the marine LIP: however, it is beyond the scope of this study.

Using this model, we estimated the response of the global C–P–S–Fe–O2–Ca biogeochemical cycles to the intense volcanism after the eruption of LIPs under the reducing conditions during the late Archean. We first obtain the Archean-like background steady-state using the set of the standard parameters listed in Table 1. Starting from this background state, we investigate the response of the system to the volcanism assuming the eruption of LIPs. We simulate the response with respect to different background hydrothermal Fe(II) supply rates, fa, background reducing gas outgassing rate, reducing gas outgassing rate from LIPs, total C influx, and duration of LIP (Table S5).

Responses