Mechanochemical activation of metallic lithium for the generation and application of organolithium compounds in air

Main

Over the past decade, mechanochemical synthesis using ball-milling techniques has emerged as a new tool for carrying out organic transformations under minimal-solvent conditions1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. The benefits of this method include reduced solvent waste, shorter reaction times and simple operational procedures under ambient conditions. More recent studies have shown that strong mechanical agitation activates zero-valent metals by removing an unreactive superficial oxide layer and increasing the reactive surface area via this crushing process. These highly reactive in situ–activated metals readily undergo surface reactions with organic halides, resulting in the rapid formation of organometallic species10. Since the synthesis of organobismuth compounds using a direct mechanochemical approach in 2003 (ref. 11), a variety of synthetically useful organometallic species such as Grignard reagents12,13,14,15, as well as organozinc16, organocalcium17 and organomanganese18,19 compounds have been prepared efficiently using mechanochemical activation. However, the direct mechanochemical synthesis of organolithium reagents, which are among the most fundamental and valuable organometallic compounds in organic synthesis, has yet to be explored systematically. Recently, we have demonstrated that ball-milling activation of bulk lithium metal enables highly efficient mechanochemical Birch reduction reactions20. Importantly, unlike in previously reported solution-based methods21, all experimental procedures can be carried out in air. At almost the same time, Itami, Ito and co-workers reported a lithium-mediated mechanochemical cyclodehydrogenation22. These successful results motivated us to systematically investigate the direct generation of organolithium species from lithium metal and their use in organic transformations under mechanochemical conditions.

Since their discovery in 1917 by Schlenk and Holtz, organolithium compounds have been widely used as carbon nucleophiles to construct carbon–carbon and carbon–heteroatom bonds via nucleophilic addition/substitution to electrophiles in both academic and industrial settings23,24,25,26. Therefore, reliable, practical, cost-effective and sustainable methods for the generation of organolithium compounds are in high demand. Among the several established synthetic routes to organolithium nucleophiles, the direct lithiation of organic halides with lithium metal is one of the most straightforward and atom-economical approaches (Fig. 1a)27. However, this route usually requires highly dehydrated conditions, strict temperature control with relatively complex reaction set-ups and large quantities of dry bulk solvents. Additionally, commercially unavailable and/or poorly bench-stable activated lithium sources such as lithium powder or dispersions are often needed for efficient lithiation, especially in the case of relatively unreactive organic halides28,29,30. Another problem with solution-based methods is the inefficiency of the generation of organolithium compounds from poorly soluble organic halides. Unfortunately, these shortcomings continue to present major environmental, economic and practical challenges. In this context, we envisioned that mechanochemistry could provide a simple, powerful and sustainable platform for the generation of organolithium compounds.

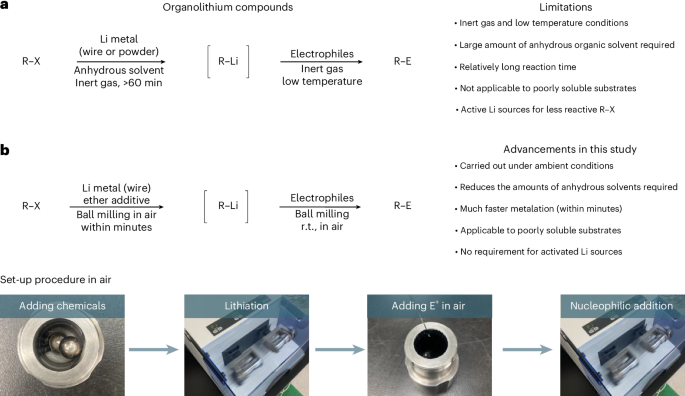

a, Conventional solution-based direct synthesis of organolithium compounds27. b, Direct mechanochemical synthesis of organolithium compounds through ball milling. The photos illustrate the setup procedure for mechanochemical lithiation. R–X refers to an organic halide. E+, electrophile; r.t., room temperature.

In this Article, we report a mechanochemical protocol for the rapid generation of organolithium compounds from readily available lithium metal (lithium wire) and organic halides under ambient conditions at room temperature (Fig. 1b). Our developed method does not require pre-activated metals, bulk quantities of dry organic solvents or complex synthetic procedures with strict temperature control. Furthermore, these rapid reactions are completed within minutes, which could be attributed to the mechanical activation of lithium metal in situ. Importantly, this method is applicable to poorly soluble substrates that are barely reactive under solution-based conditions. These mechanochemically generated lithium-based carbon nucleophiles can be used for nucleophilic additions to carbonyl compounds, silicon- and boron-based electrophiles and nickel-catalysed cross-coupling reactions in a one-pot fashion. The potential of this approach is further highlighted by a gram-scale synthesis, as well as the rapid lithiation of aryl fluorides and alkyl fluorides without using pre-activated lithium sources.

Results

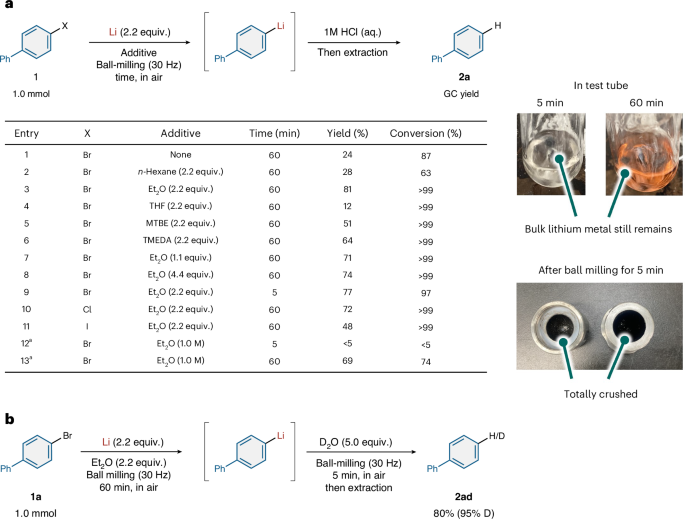

Mechanochemical generation of organolithium compounds in air

We first attempted the generation of organolithium species from biphenyl bromide (1a, 1.0 mmol) and lithium wire (2.2 equiv.), which can be easily handled in air, using a Retsch MM400 mixer mill (10 ml stainless steel milling jar with two stainless steel balls, ball diameter: 10 mm) (Fig. 2a). The mineral oil was removed from the lithium wire by wiping it with paper towels, before the wire was cut into pieces with a length of approximately 4–5 mm. Subsequently, the lithium-metal pieces were weighed and introduced into the jar, before 1a was then added under atmospheric conditions. After ball milling, the mixture was quenched using 1 M HCl (aq.) and the formation of protonation product 2a was verified using gas-chromatography (GC) analysis. Unfortunately, only a 24% yield of 2a was obtained while 87% of 1a was consumed under these conditions (Fig. 2a, entry 1). Accordingly, we next tested the use of liquid additives to facilitate the generation of the organolithium species. While the addition of hexane (2.2 equiv.) did not improve the yield of 2a, ethers and amines promoted the generation of organolithium species (Fig. 2a, entries 2–8). While the reaction using diethyl ether (Et2O, 2.2 equiv.) afforded 2a in 81% yield (Fig. 2a, entry 3), that using tetrahydrofuran (THF) provided 2a in only 12% yield (Fig. 2a, entry 4). The reactions using methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) and tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA) gave some improvement (51 and 64% yield, respectively; Fig. 2a, entries 5 and 6, respectively), but Et2O remained the best additive for this protocol. Both decreasing and increasing the amount of Et2O negatively affected the yield of 2a (71 and 74% yield, respectively; Fig. 2a, entries 7 and 8, respectively). Surprisingly, we found that the conversion into 2a was almost complete within 5 min (77%, Fig. 2a, entry 9). Next, we investigated other halides and found that 2a can be generated from the aryl chloride or iodide (72 and 48% yield, respectively; Fig. 2a, entries 10 and 11, respectively). To confirm the effectiveness of ball milling, we carried out several control experiments using a test tube with a glass stirrer bar under a nitrogen atmosphere. We found that the generation of 2a under solution-based conditions using Et2O (1.0 M) was relatively slow compared to that under ball-milling conditions (5 min: <5% yield; 60 min: 69% yield; Fig. 2a, entries 12 and 13, respectively). In the solution-based reaction, solid pieces of lithium were still present after 60 min. By contrast, no bulk lithium metal was observed after 5 min of ball milling. These results suggest that the ball-milling process facilitates the crushing of the lithium metal in situ and increases the active surface area, which leads to the rapid formation of organolithium species. The formation of the aryllithium nucleophile under ball-milling conditions was confirmed by the nearly quantitative deuteration of the product quenched using D2O (5 equiv.) immediately after opening the jar (Fig. 2b).

a, Optimization study for the formation of organolithium reagents. Conditions: 1 (1.0 mmol), Li (2.2 mmol) and additive (2.2 mmol) in a stainless steel ball-milling jar (10 ml) with two stainless steel balls (10 mm). Gas-chromatography (GC) yields are shown. The photos show that lithium metal was completely pulverized under mechanochemical conditions, while some remains unreacted in the test tube reaction. aReactions were carried out in a test tube with a stirring bar. b, Deuterium-labelling experiment. Conditions: 1 (1.0 mmol), Li (2.2 mmol), Et2O (2.2 mmol) and D2O (5.0 mmol) in a stainless steel ball-milling jar (10 ml) with two stainless steel balls (10 mm). Integrated 1H NMR spectroscopic yields are shown. THF, tetrahydrofuran; MTBE, tert-butyl methyl ether; TMEDA, tetramethylenediamine.

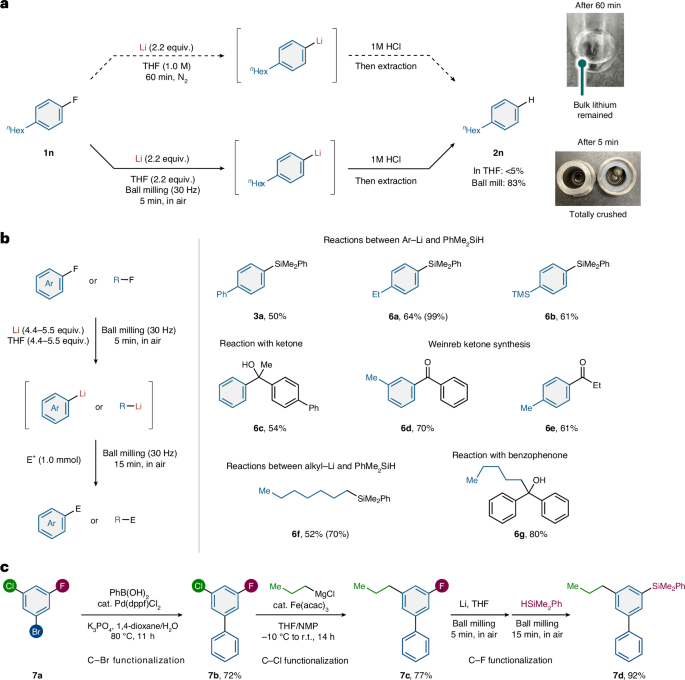

Mechanochemical generation and use of aryllithium compounds

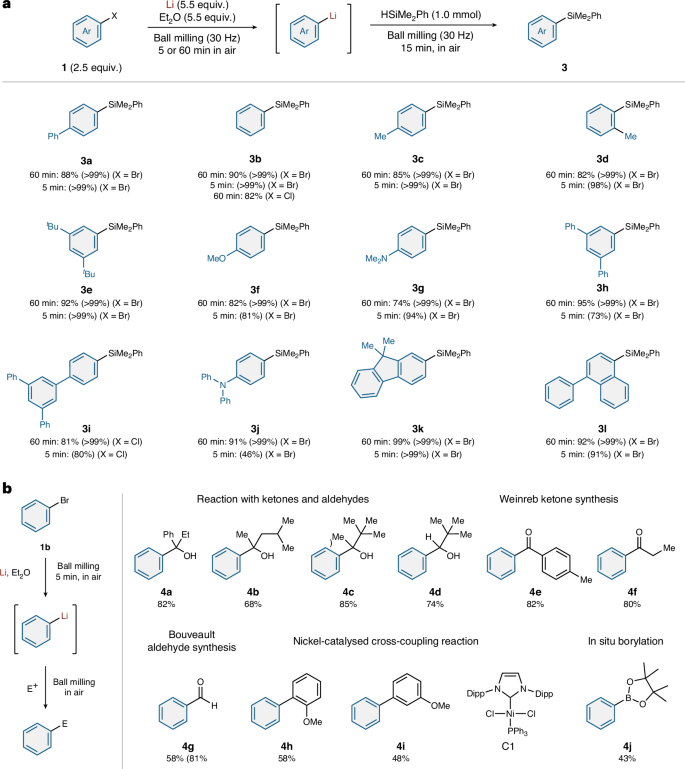

To investigate the scope of accessible aryllithium species, we carried out reactions using a variety of aryl bromides; the resulting mechanochemically generated carbon nucleophiles were trapped using dimethylphenylsilane (PhMe2SiH, Fig. 3a). Specifically, a mixture of 1, lithium metal and Et2O was ball milled for 60 min, before the jar was opened in air and PhMe2SiH was quickly added to the jar. The jar was then closed without purging with an inert gas and further ball milling was carried out for 15 min. Using this protocol, the lithium-based nucleophile generated from biphenyl bromide (1a) reacted smoothly to afford the corresponding silylation product (3a) in 88% yield. Phenyllithium was successfully generated from bromobenzene (1b) or chlorobenzene (1b′) and nucleophilic substitution with PhMe2SiH gave 3b in 90 and 82% yield, respectively. Lithium-based carbon nucleophiles were efficiently generated from alkyl-substituted substrates (1c–1e) and the reactions with PhMe2SiH proceeded in high yield (82–92%). Electron-rich aryl bromides bearing a methoxy group (1f) and a dimethylamino group (1g) afforded the corresponding silylation products (3f and 3g) in 82 and 74% yield, respectively. Polyaromatic halides (1h and 1i) could be used under the optimized conditions, providing the corresponding products (3h and 3i) in 95 and 81%, respectively yield. Furthermore, substrates with a triarylamine structure (1j), a fluorene moiety (1k) or a naphthalene core (1l) provided the corresponding products in excellent yield (91, 99 and 92%, respectively). Moreover, reducing the reaction time for the generation of organolithium species to 5 min did not affect the results in most cases, emphasizing the exceptionally high efficiency of the mechanochemical protocol. Heteroaromatic lithium compounds, including thiophene, furan and pyridine, were also investigated, but the results were poor (see the Supplementary Information for details).

a, Substrate scope of aryl halides and carbon–silicon bond-forming reactions. b, Generation of phenyllithium in minutes and reactions with various electrophiles. Isolated yields are shown. Integrated 1H NMR spectroscopic yields are shown in parentheses. See Supplementary Section 2 for details. Dipp, 2,6-diisopropylphenyl; E+, electrophile.

Next, we carried out a series of one-pot mechanochemical reactions using various electrophiles (Fig. 3b). For that purpose, 1b and lithium metal were ball milled in the presence of Et2O for 5 min and the subsequent nucleophilic addition to ketones afforded the corresponding tertiary alcohols (4a–4c) in good yield (68–85%). Pivalaldehyde also underwent the nucleophilic addition to deliver the desired secondary alcohol (4d) in good yield (74%). Additionally, Weinreb amides reacted with the mechanochemically generated phenyllithium smoothly, providing the corresponding ketones 4e and 4f in 82 and 80% yield, respectively. We also found that the Bouveault aldehyde synthesis is feasible under the mechanochemical conditions. This provided benzaldehyde (4g) in 58% yield through nucleophilic addition to N-formylpiperidine. Furthermore, mechanochemical nickel-catalysed cross-coupling reactions with aryl chlorides using N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC)–nickel complex C1 (ref. 31) afforded the desired coupling products (4h and 4i) in moderate-to-good yield (58 and 48%, respectively). The boron electrophile i-PrO–B(pin) (Pr, propyl; pin, pinacolato) did not interfere with the lithiation step and thus the in situ borylation with lithium metal 1b and i-PrO–B(pin) directly afforded borylation product 4j in 43% yield.

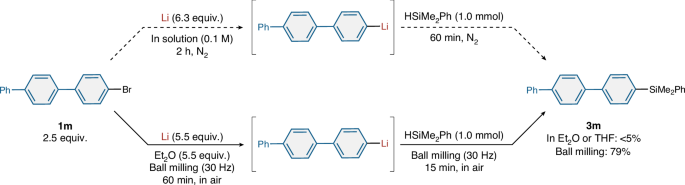

Direct lithiation of poorly soluble aryl halides under traditional solution-based conditions is challenging and often ineffective. Specifically, the solution-based lithiation of poorly soluble 4-bromoterphenyl (1m, solubility in Et2O at 23 °C: 7.2 × 10–2 M) as a slurry in Et2O does not proceed and the formation of silylation product 3m in preparatively substantial amounts was not observed (Fig. 4). The use of THF instead of Et2O as the solvent did not improve the efficiency. We also tested the reaction in the presence of a catalytic amount (5 mol%) of naphthalene, but the formation of 3m was not observed. By contrast, under the mechanochemical conditions developed in this study, the corresponding lithium-based carbon nucleophile from 1m and the desired silylation product (3m) were obtained in high yield (79%) (Fig. 4). These results show the potential of this mechanochemical protocol as an efficient synthetic method to form organolithium reagents from poorly soluble substrates that are not compatible with solution-based direct methods.

Conditions (in Et2O or THF): 1m (2.5 mmol), Li (6.3 mmol), PheMe2SiH (1.0 mmol) and solvent (25 ml). Conditions (ball milling): 1m (2.5 mmol), Li (5.5 mmol), Et2O (5.5 mmol) and PhMe2SiH (1.0 mmol). Isolated yields are shown. Integrated 1H NMR spectroscopic yields are shown in parentheses. THF, tetrahydrofuran.

Generation of alkyllithium and heteroaryllithium compounds

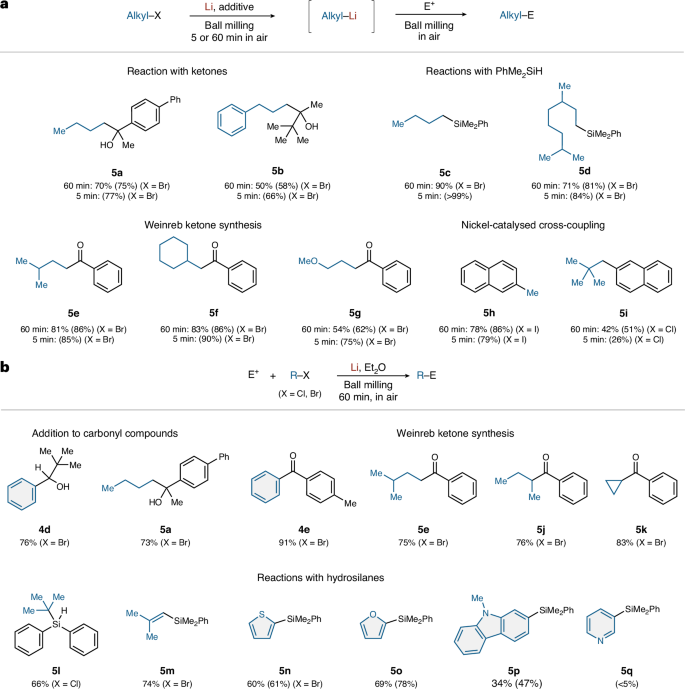

Next, the mechanochemical generation of alkyllithium nucleophiles was explored (Fig. 5a). Primary alkyllithium compounds were generated successfully under the mechanochemical conditions and their nucleophilic addition to ketones afforded the desired tertiary alcohols (5a and 5b) in 70 and 50% yield, respectively. Reactions of mechanochemically generated alkyllithium species with hydrosilanes also proceeded smoothly and the desired silylation products (5c and 5d) were obtained in 90 and 71% yield, respectively. Direct lithiation of aliphatic alkyl bromides and subsequent reactions with a Weinreb amide [PhCON(OMe)Me] smoothly furnished the desired ketone products (5e, 5f and 5g) in 81, 83 and 54% yield, respectively. Furthermore, mechanochemical nickel-catalysed cross-coupling reactions with 2-chloronaphthalene furnished the corresponding alkylation products (5h and 5i) in 78 and 42% yield, respectively. Moreover, the alkyllithium compounds could also be generated in 5 min and reactions with various electrophiles proceeded in comparable yields to those of these compounds obtained using a reaction time of 60 min for their mechanochemical generation.

a, One-pot two-step protocol (primary alkyllithium species). b, Barbier-type reaction (phenyl, primary, secondary and tertiary alkyllithium species, as well as vinyllithium species and heteroaryllithium species). Isolated yields are shown. Integrated 1H NMR spectroscopic yields are shown in parentheses. See Supplementary Section 2 for details. E+, electrophile.

Next, we investigated one-pot Barbier-type reactions to simplify the experimental procedure and to use the highly reactive organolithium compounds that are immediately decomposed during the first mechanochemical lithiation step, albeit that the electrophiles were limited to compounds compatible with highly reducing conditions (Fig. 5b). We found that nucleophilic addition of mechanochemically generated phenyllithium and n-butyllithium to carbonyl compounds afforded the corresponding alcohols (4d and 5a) in 76 and 73% yield, respectively. Furthermore, a Weinreb ketone synthesis using mechanochemically generated phenyllithium and primary alkyllithium compounds afforded the desired ketones (4e and 5e) in 91 and 75% yield, respectively. These results are comparable to those of the one-pot two-step reactions. Unfortunately, secondary and tertiary alkyllithium compounds decomposed immediately during the mechanochemical lithiation step due to their high reactivity, which renders the established two-step procedure inaccessible for these substrates. However, we found that one-step Barbier-type reactions were possible using such alkyllithium reagents, although the electrophiles were limited to compounds compatible with highly reducing conditions (Fig. 5b). The nucleophilic substitution of Weinreb amide [PhCON(OMe)Me] with secondary alkyllithium species afforded the corresponding ketones (5j and 5k) in 76 and 83% yield, respectively. This method is applicable to the generation of tert-BuLi from 2-chloro-2-methylpropane, which was trapped by diphenylsilane (Ph2SiH) to give the silylation product (5l) in 66% yield. A vinyllithium compound was also efficiently generated under mechanochemical conditions and its in situ reaction with PhMe2SiH afforded alkenylsilane 5m in 74% yield. Furthermore, we found that the Barbier-type mechanochemical protocol allows a more efficient silylation of heteroaryl bromides to give the corresponding products (5n, 5o and 5p) in 60, 69 and 34% yield, respectively, while the two-step protocol for these substrates gave poor results (see Supplementary Information for details). However, 3-bromopyridine could not be transformed even by the Barbier-type protocol. Unfortunately, the direct generation of benzylic halides was unsuccessful, except for the reaction with 4-phenylbenzyl halide (see Supplementary Information for details).

Furthermore, we attempted the preparation of lithium diisopropylamide (LDA), an important lithium-containing base, under mechanochemical conditions (Fig. 6). HN(i-Pr)2 was added to the mechanochemically generated n-BuLi in a ball mill and subsequent addition of acetophenone and trimethylsilyl chloride provided the desired silyl enol ether (5r) in 64% yield without producing the nucleophilic addition product (5s). By contrast, addition product 5s was obtained as the major product in the absence of HN(i-Pr)2. This clear product switching strongly suggests that LDA was prepared under mechanochemical conditions.

Integrated 1H NMR spectroscopic yields are shown. See Supplementary Section 5 for details. TMS, trimethylsilyl.

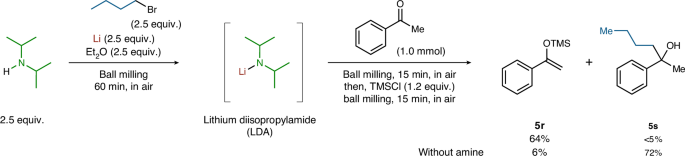

Practical utility

To emphasize the practical utility of our developed mechanochemical protocol, we investigated its use in preparative-scale reactions (Fig. 7a). Phenyllithium was successfully synthesized on a 15-mmol scale and its nucleophilic addition to propiophenone (7.5 mmol) afforded 4a without any decrease in yield (82% yield, 1.301 g) compared to the small-scale synthesis. A gram-scale Barbier reaction with 1-bromo-3-methylbutane (13 mmol, 1.964 g) efficiently furnished 5f in 74% yield. These results underline the practical utility of this method.

a, Gram-scale synthesis. b, Development of a safety-oriented jar and procedure. The photos illustrate the safety-oriented procedure using a jar with a small hole. c, Generation of alkyllithium compounds and reactions with electrophiles using a safety-oriented jar. Isolated yields are shown. See Supplementary Sections 2 and 6 for details. E+, electrophile.

Although we did not encounter any safety issues using the developed mechanochemical procedure, we designed and developed a jar to address potential safety concerns (Fig. 7b,c). In our initial developed procedure, the jar was opened under air after the generation of organolithium compounds, which might present a hazard due to the potential for highly exothermic reactions with moisture in the air. To avoid exposing the synthesized organolithiums to air as much as possible, a small hole was made in the jar through which the electrophiles could be added via syringe; the hole could then be sealed by inserting a screw. We found that this safety-oriented procedure allowed the mechanochemical reactions to be carried out efficiently. The yields of the products were almost identical to those obtained using the initial procedure and even improved in some cases owing to the minimization of the exposure to air.

Generation of organolithium compounds from organic fluorides

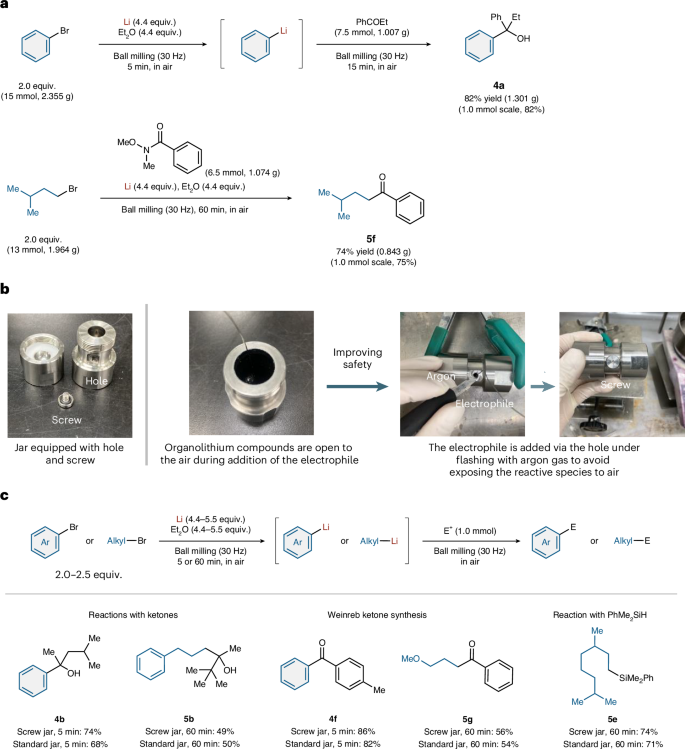

Given the high efficiency of this mechanochemical approach, we wondered whether it would be applicable to generate organolithium compounds from organic fluorides via C–F bond activation. Direct metalations of organofluorine compounds are highly challenging due to the strength of the C–F bond. Although the reduction potential of lithium is sufficient to reduce fluoroarenes (fluorobenzene: Ered° = −2.91 V versus saturated calomel electrode, Li+: Ered° = −3.28 V versus saturated calomel electrode)32, a pre-activated lithium source such as an excess of lithium powder, which is not commercially available, in the presence of naphthalene is required to cleave the C–F bond efficiently33,34. In fact, the solution reaction of fluoroarene (1n) with lithium metal (wire) in THF failed to give the protonated product 2n after quenching with HCl solution, suggesting that the corresponding organolithium compound was not generated (Fig. 8a). Even when adding a catalytic amount (5 mol%) of naphthalene, 2n was not formed. Under these conditions, the bulk lithium metal remained intact. We envisioned that the in situ mechanical activation of lithium metal via ball milling would enable the C–F bond activation. Pleasingly, after 5 min of ball milling with 1n in the presence of lithium metal and THF as an additive, protonated 2n was obtained in 83% yield and no bulk lithium metal was observed after the reaction (Fig. 8a).

a, Mechanochemistry allows efficient C−F bond lithiation with bulk lithium metal. The photos show that lithium metal was completely pulverized under mechanochemical conditions, while some remains unreacted in the test tube reaction. b, Scope of organofluorine compounds. c, Selective stepwise functionalization via late-stage C−F bond lithiation. Isolated yields are shown. Integrated 1H NMR spectroscopic yields are shown in parentheses. dppf, 1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene; acac, acetylacetonate; E+, electrophile; THF, tetrahydrofuran; NMP, N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone; r.t., room temperature. See Supplementary Sections 2 and 8 for details.

Subsequently, we conducted various organic transformations of organofluorine compounds via mechanochemically driven C–F bond lithiation (Fig. 8b). Reactions of PhMe2SiH with mechanochemically generated aryllithium compounds gave the corresponding silylation products (3a, 6a and 6b) in 50, 64 and 60% yield, respectively. Nucleophilic addition to a ketone gave the desired alcohol (6c) in 54% yield. This procedure is also applicable to the Weinreb ketone synthesis and the desired products (6d and 6e) were obtained in 70 and 61% yield, respectively. The mechanochemically driven C–F bond lithiation of alkyl fluorides was also successful and reactions with PhMe2SiH and benzophenone gave the corresponding products (6f and 6g) in 52 and 80% yield, respectively.

Synthetic methods that introduce different groups onto aromatic compounds are important. Most commonly, two different halogen groups with different reactivity tags (Cl versus Br, Cl versus I, Br versus I and so on) are used to achieve the multistep functionalization of aromatic rings35. However, little has been done to take advantage of the different selectivities of the three halogens F, Cl and Br, because the reactivity of F is usually low and thus, it is seldom used as a reactive halogen moiety36. To demonstrate the potential utility of this mechanochemically driven C–F bond lithiation, a selective three-step functionalization was investigated. Starting from a trihaloarene bearing bromo, chloro and fluoro groups (7a), we first carried out a selective Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling of the C–Br bond to afford arylated coupling product 7b in 72% yield (Fig. 8c). Next, an iron-catalysed cross-coupling of the C–Cl bond with n-PrMgCl provided alkylated coupling product 7c in 77% yield37. Finally, our developed mechanochemically driven lithiation allowed a further electrophilic silylation of the resulting inert C–F bond to give 7d in 92% yield. This result suggests that our mechanochemical strategy for facile C–F bond lithiation may enable efficient alternative retrosynthetic approaches in the synthesis of structurally complex molecules.

Discussion

This study has presented a mechanochemical approach for the rapid generation of organolithium compounds, which are essential in organic synthesis. This has been achieved under ambient conditions and without the need for large amounts of dry solvents, special precautions against moisture, temperature control or synthetic techniques associated with the need to use inert gases. Importantly, this process is applicable to the generation of a wide variety of organolithium compounds, including aryllithium and vinyllithium, as well as primary, secondary and tertiary alkyllithium reagents. Furthermore, this method is applicable to poorly soluble substrates that are scarcely reactive under conventional solution-based conditions. The resulting organolithium nucleophiles efficiently react with various electrophiles in a one-pot fashion or in one-step Barbier-type mechanochemical protocols. The present mechanochemical strategy allows the extremely rapid lithiation of organic fluorides within minutes, without requiring pre-activated lithium sources. Given the widespread use of organolithium reagents in modern organic synthesis, we anticipate that this approach will inspire the development of more efficient and sustainable mechanochemical technologies centred on organolithium reagents to complement existing solution-based organic syntheses.

Methods

Representative procedure for the mechanochemical generation of organolithium compounds and reactions with electrophiles

Lithium wire (4.4–5.5 equiv.) was cut into small pieces (diameter approximately 4–5 mm) and weighed in the air after wiping off the mineral oil on it with paper. The wire was then added into a milling jar (10 ml) with two balls (10 mm diameter). An organic halide (2.0–2.5 equiv.) and Et2O or THF (4.4–5.5 equiv.) were added to the jar. After the jar was closed without purging with inert gas, the jar was placed in the ball mill (Retsch MM 400, 30 Hz). After grinding for 5, 15 or 60 min, the jar was opened in air and charged with an electrophile (1.0 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) as quickly as possible. The jar was then closed without purging with inert gas and was placed in the ball mill. After grinding for 15 min, the reaction mixture was quenched with a saturated aqueous solution of NH4Cl and extracted with EtOAc (30 ml × 3). The solution was dried over MgSO4, filtered and evaporated under reduced pressure. The crude yield of the corresponding product was determined by 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis with 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane as the internal standard. The crude material was purified by flash chromatography (SiO2, typically EtOAc/n-hexane, typically 0–10:90) to give the corresponding product.

Representative procedure for the Barbier conditions for generating and using organolithium compounds

Lithium wire (4.4–8.0 equiv.) was cut into small pieces (diameter approximately 4–5 mm) and weighed in air after wiping off the mineral oil on it with paper. The wire was then added into a milling jar (10 ml) with a ball (10 mm diameter). An organic halide (2.0–4.0 equiv.), Et2O (4.4–8.0 equiv.) and an electrophile (1.0 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) were added to the jar. After the jar was closed without purging with inert gas, the jar was placed in the ball mill (Retsch MM 400, 30 Hz). After grinding for 60 min, the reaction mixture was quenched with a saturated aqueous solution of NH4Cl and extracted with EtOAc (30 ml × 3). The solution was dried over MgSO4, filtered and evaporated under reduced pressure. The crude yield of the corresponding product was determined by 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis with 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane as the internal standard. The crude material was purified by flash chromatography (SiO2, typically EtOAc/n-hexane, typically 0–10:90) to give the corresponding product.

Responses