Medical foundation large language models for comprehensive text analysis and beyond

Introduction

Large language models (LLMs) have shown great potential in improving medical applications such as clinical documentation, diagnostic accuracy, and patient care management1,2,3. However, general-domain LLMs often lack specialized medical knowledge because they are primarily trained on non-medical datasets4, limiting their effectiveness in healthcare settings. Although commercial LLMs, such as ChatGPT and GPT-44, offer advanced capabilities, their closed-source nature restricts the flexible customization and accessibility required for medical use. This limitation has spurred the research towards developing open-source LLMs such as LLaMA5,6; Yet these models still fall short due to their general-domain training7,8,9.

To address these challenges, researchers have explored strategies to develop domain-specific LLMs for the medical domain. Instruction fine-tuning of general-domain models, as seen in MedAlpaca3, ChatDoctor10, and AlpaCare11, attempts to enhance medical capabilities but is limited by the base models’ lack of specialized knowledge; instruction fine-tuning alone cannot compensate for this deficiency. Training models from scratch using medical corpora, exemplified by GatorTronGPT8, overcomes this limitation but demands substantial computational resources and time. A more cost-effective alternative is continual pretraining, enabling models to acquire specialized medical knowledge while leveraging existing model architectures; notable examples include PMC-LLaMA2, Meditron9, and Clinical LLaMA12.

Despite these advances, existing LLMs of continual pretraining in the medical domain exhibit notable limitations: (1) Although both domain knowledge and instruction-following capabilities are crucial, only PMC-LLaMA2 has combined continual pretraining with instruction fine-tuning, revealing a gap in leveraging the synergy between these two aspects. (2) Only one model (Clinical LLaMA) used clinical notes from electronic health records, which is crucial for real-world clinical applications as it provides context-specific information from direct patient care. None of the existing models used both biomedical literature and clinical notes, which is one of the goals of this project. (3) Due to the limited medical datasets utilized for model development, these models still lack essential domain knowledge, which hampers their effectiveness. By combining biomedical literature and clinical notes, we generated the largest biomedical pre-training dataset (129B tokens), compared to the previous efforts (i.e., 79B tokens in PMC-LLaMA as the highest). (4) Evaluations have predominantly centered on medical question-answering (QA) tasks, lacking comprehensive assessments on the generalizability of those foundation models across diverse medical tasks.

To overcome these limitations, we present Me-LLaMA, a novel family of open-source medical large language models that uniquely integrate extensive domain-specific knowledge with robust instruction-following capabilities. Me-LLaMA comprises foundation models (Me-LLaMA 13B and 70B) and their chat-enhanced versions, developed through comprehensive continual pretraining and instruction tuning of LLaMA26 models. Leveraging an extensive medical dataset—combining 129 billion pretraining tokens and 214,000 instruction samples from scientific literature, clinical guidelines, and electronic health record clinical notes—Me-LLaMA excels across a wide spectrum of medical text analysis and real-world clinical tasks. Prior studies2,3,7,8,9,10,11,12 have primarily focused on evaluating the QA task. For example, PMC-LLaMA2 and Meditron9 evaluated their model performance on medical QA tasks derived from domain-specific literature, while MedAlpaca3 and ChatDoctor10 focused on conversational QA. In contrast, we conduct a comprehensive evaluation covering six critical tasks — question answering, relation extraction, named entity recognition, text classification, text summarization, and natural language inference—across twelve datasets from both biomedical and clinical domains. Our results demonstrate that Me-LLaMA not only surpasses existing open-source medical LLMs in both zero-shot and supervised settings but also, with task-specific instruction tuning, outperforms leading commercial LLMs such as ChatGPT on seven out of eight datasets and GPT-4 on five out of eight datasets. Furthermore, to evaluate Me-LLaMA’s potential clinical utility, we assessed the models on complex clinical case diagnosis tasks, comparing their performance with other commercial LLMs using both automatic and human evaluations. Our findings indicate that Me-LLaMA’s performance is comparable to that of ChatGPT and GPT-4, despite their substantially larger model sizes.

Our findings underscore the importance of combining domain-specific continual pretraining with instruction tuning to develop effective large language models for the medical domain. Recognizing the significant resources required, we have publicly released our Me-LLaMA models on PhysioNet under appropriate Data Use Agreements (DUAs) to lower barriers and foster innovation within the medical AI community. Alongside the models, we provide benchmarks and evaluation scripts on GitHub to facilitate further development. We anticipate that these contributions will benefit researchers and practitioners alike, advancing this critical field toward more effective and accessible medical AI applications.

Results

Overall performance of medical text analysis

Table 1 compares the performance of our Me-LLaMA 13/70B foundation models against other open LLMs in the supervised setting. The performance of Meditron 70B on the PubMedQA, MedQA, and MedMCQA datasets is cited from the meditron paper to have a fair comparison. We can observe that the Me-LLaMA 13B model surpassed the similar-sized medical foundation model PMC-LLaMA 13B on 11 out of 12 datasets and outperformed the general foundation model LLaMA2 13B on 10 out of 12 datasets. Moreover, it is noticed that the Me-LLaMA 13B model was competitive with LLaMA2 70B and Meditron 70B, which have significantly larger parameter sizes, on 8 out of 12 datasets. As for 70B models, Me-LLaMA 70B achieved the best performance on 9 out of 12 datasets, when benchmarked against LLaMA2 70B and Meditron 70B.

Table 2 shows the zero-shot performance of Me-LLaMA chat models and other instruction-tuned open LLMs with chat ability on various tasks. Among 13B models, Me-LLaMA 13B-chat outperformed LLaMA2 13B-chat, PMC-LLaMA-chat, Medalpaca 13B in almost all 12 datasets. Me-LLaMA outperformed AlpaCare-13B in 9 out of 12 datasets. Among models with 70B parameters, Me-LLaMA 70B-chat consistently outperformed LLaMA2-70B-chat on 11 out of 12 datasets. It is worth noting that Me-LLaMA13B-chat showed better performance than LLaMA2-70B-chat—a model with a significantly larger parameter size—on 6 out of 12 datasets and was competitive with the LLaMA2-70B-chat in 3 out of 6 remaining datasets.

Figure 1 further compares the performance of Me-LLaMA models in the zero-shot and supervised learning setting, against ChatGPT and GPT-4. Due to privacy concerns, which preclude the transmission of clinical datasets with patient information to ChatGPT and GPT-4, we conducted our comparison across 8 datasets that are not subject to these limitations. The results of ChatGPT and GPT-4 on three QA datasets are referenced from the OpenAI’s paper1. We compared the Rouge-113 score for the summarization dataset PubMed, the accuracy score for three QA datasets, and the Macro-F1 score for the remaining datasets. With task-specific supervised fine-tuning, Me-LLaMA models surpassed ChatGPT on 7 out of 8 datasets and excelled GPT-4 on 5 out of 8 datasets. In the zero-shot setting, Me-LLaMA models outperformed ChatGPT on 5 datasets; but it fell short on 7 datasets, when compared with GPT-4. It’s crucial to highlight that Me-LLaMA’s model size is significantly smaller—13/70B parameters versus at least 175B for ChatGPT and GPT-4. Despite this size discrepancy, Me-LLaMA models have showcased an impressive performance and a strong ability for supervised learning and zero-shot learning across a broad spectrum of medical tasks, underscoring its efficiency and potential in the field.

The figure presents the zero-shot performance of Me-LLaMA (Me-LLaMA zero-shot) alongside its supervised learning performance (Me-LLaMA task-specific), compared against the zero-shot performance of ChatGPT and GPT-4 across 8 datasets.

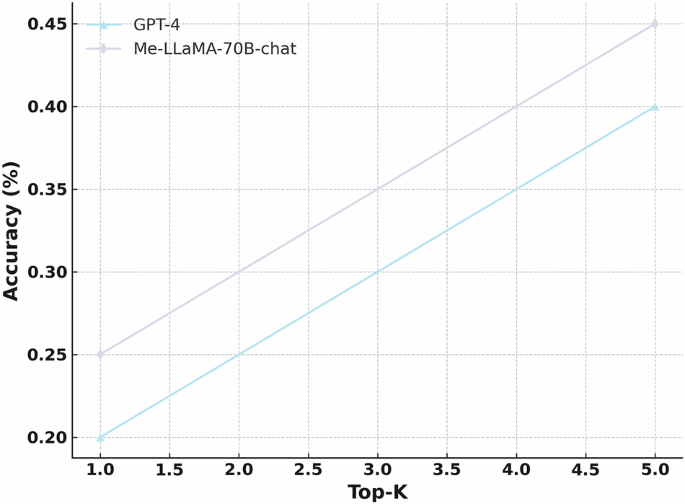

Performance of complex clinical case diagnosis

Figure 2 shows the top-K (1 ≤ K ≤ 5) accuracy of Me-LLaMA-70B-chat, ChatGPT, GPT-4, and LLaMA2-70B-chat, in the complex clinical case diagnosis task. We can see Me-LLaMA-70B-chat model achieved comparable performance with GPT-4 and ChatGPT and significantly outperforms LLaMA2-70B-chat. The human evaluation result in Fig. 3 again shows that Me-LLaMA-70B-chat outperformed GPT-4 in both top-1 and top-5 accuracy. These results demonstrated the potential of Me-LLaMA models for challenging clinical applications.

The figure presents the top-K accuracy (where 1 ≤ K ≤ 5) of Me-LLaMA-70B-chat, ChatGPT, GPT-4, and LLaMA2-70B-chat on a complex clinical case diagnosis task, evaluated automatically.

The figure shows the top-1 and top-5 accuracy of Me-LLaMA/-70B-chat and GPT-4 in a complex clinical case diagnosis task, evaluated through human assessment.

Impact of continual pretraining and instruction tuning

Table 3 demonstrates the impact of continual pre-training and instruction tuning on zero-shot performance across medical NLP tasks. It clearly demonstrates that both continual pre-training and instruction tuning significantly enhanced the zero-shot capabilities of models. Instruction tuning alone provides significant performance improvements over the base LLaMA2 models, as seen in LLaMA2 13B, where accuracy on PubMedQA increases from 0.216 to 0.436. This suggests that instruction tuning is highly effective in enhancing the model’s ability to follow task-specific prompts. In contrast, continual pre-training on medical data yields relatively modest improvements, particularly for smaller models. Me-LLaMA 13B shows only slight gains over LLaMA2 13B, likely due to the smaller scale of domain-specific pre-training data compared to LLaMA2’s original training corpus, which exceeds 2 T tokens. Additionally, continual pre-training may not provide as strong of a task-specific signal as instruction tuning, limiting its impact in zero-shot settings. However, for larger models like Me-LLaMA 70B, continual pre-training results in more notable improvements, with performance gains ranging from 2.1% to 55% across various datasets, demonstrating its value in capturing specialized domain knowledge. The best results are consistently achieved when both continual pre-training and instruction tuning are applied together, as seen in Me-LLaMA-70B-chat, which outperforms all other configurations. This indicates that while instruction tuning is the most efficient approach for improving task performance, continual pre-training provides a complementary boost, particularly for larger models where additional domain adaptation enhances overall effectiveness.

Discussion

We introduced a novel medical LLM family including, Me-LLaMA 13B and Me-LLaMA 70B, which encode comprehensive medical knowledge, along with their chat-optimized variants: Me-LLaMA-13/70B-chat, with strong zero-shot learning ability, for medical applications. These models were developed through the continual pre-training and instruction tuning of LLaMA2 models, using the largest and most comprehensive biomedical and clinical data. Compared to existing studies, we perform the most comprehensive evaluation, covering six critical text analysis tasks. Our evaluations reveal that Me-LLaMA models outperform existing open-source medical LLMs in various learning scenarios, showing less susceptibility to catastrophic forgetting and achieving competitive results against major commercial models including ChatGPT and GPT-4. Our work paves the way for more accurate, reliable, and comprehensive medical LLMs, and underscores the potential of LLMs on medical applications.

Despite these strengths, we observed certain challenges in specific tasks, such as NER and RE14,15, where even advanced models like GPT-4 exhibited low performance. When compared with other NLP tasks with higher performance, we noticed that one of the main reasons for low performance is that LLMs’ responses often lacked the conciseness and precision expected, with instances of missing outputs noted. The unexpected outputs also cause significant challenges to automatic evaluation metrics. Therefore, more investigation is needed to further improve medical LLMs’ performance across tasks in the zero-shot setting and enhance the automatic assessment of these medical LLMs’ zero-shot capabilities. For the complex clinical case diagnosis, the Me-LLaMA-chat model had competitive performance and even outperformed GPT-4 in human evaluation. Existing studies have demonstrated GPT-4 is arguably one of the strongest LLMs in this task16. The robust performance of Me-LLaMA showed potential in assisting challenging clinical applications. It is noticed that variations in test sizes and evaluation methods across different studies contribute to the observed differences in performance between GPT-4 in our paper and other studies. We also noted that both the Me-LLaMA-chat model and GPT-4 faced difficulties identifying the correct diagnosis within the top ranks, underscoring the difficulty of this task. Additionally, while the NEJM CPCs offer a rigorous test for these models, they do not encompass the full range of a physician’s duties or broader clinical competence. Therefore, complex clinical diagnosis remains a challenging area that demands more effective models and improved evaluation benchmarks to better capture the complexities of real-world clinical scenarios.

Our results also emphasize the importance of data diversity during model development. Our empirical results revealed that the PMC-LLaMA 13B model, which employed a data mix ratio of 19:1 between medical and general domain data, exhibited around 2.7% performance drop across both general and biomedical tasks. On the other hand, the Meditron models, 7B, and 70B, with a 99:1 mix ratio, demonstrated improvements in biomedical tasks, yet they still saw around 1% declines in the performance of general tasks. In contrast, our models, which adopt a 4:1 ratio, have shown enhancements in their performance for both general and medical tasks. This suggests that the integration of general domain data plays a vital role in mitigating the knowledge-forgetting issue during pre-training2,9. However, determining the optimal balance between general domain data and specialized medical data is nontrivial, requiring careful empirical analysis. Future studies should examine methods to better determine the optimal ratio.

The cost-effectiveness of instruction tuning is another important consideration. Pre-training, exemplified by the LLaMA2 70B model, is notably resource-heavy, requiring about 160*700 GPU hours per epoch. Conversely, instruction tuning is far less resource-demanding, needing roughly 8*70 GPU hours per epoch, making it much more affordable than pre-training. While continual pre-training aims to incorporate specialized medical knowledge into the model, the observed performance improvements, particularly for smaller models like Me-LLaMA 13B, are relatively modest. This limited improvement can be attributed to several factors. First, the amount of domain-specific pre-training data used is significantly smaller compared to the original pre-training data of LLaMA2, which exceeds 2 T tokens. This discrepancy suggests that larger amounts of domain-specific data may be required to fully activate the model’s potential. Second, the continual pre-training strategy itself could be optimized further. As noted earlier, the process faces challenges such as catastrophic forgetting, where the model loses general-domain knowledge during adaptation to specialized data. Despite this, models trained only with the instruction tuning demonstrate that instruction tuning alone can significantly enhance performance at a fraction of the computational cost. This highlights instruction tuning as a practical and cost-effective alternative, particularly in scenarios where computational resources are limited.

The Me-LLaMA models, available in both 13B and 70B sizes, as well as in base and chat-optimized versions, enable a wide array of medical applications, guided by the crucial balance between model size and resource availability. The base models provide a strong foundation for supervised fine-tuning on specialized tasks, while the chat-optimized versions excel in instruction-following and zero-shot scenarios. Larger models, like the 70B, deliver superior reasoning capabilities but require significant computational resources, making the 13B models a practical alternative for broader accessibility. Notably, the Me-LLaMA 13B model achieves performance comparable to its 70B counterpart across most datasets, demonstrating its utility for diverse medical tasks in resource-limited settings. These features suggest that Me-LLaMA models could be explored for various medical applications. Potential areas of use include: (1) clinical decision support, where these models might assist in analyzing patient records, generating differential diagnoses, and synthesizing medical literature to support evidence-based decision-making; (2) medical education, where chat-optimized versions could serve as interactive tools for teaching medical students and trainees by providing explanations for complex medical topics and simulating diagnostic reasoning; and (3) administrative tasks, where these models may help streamline workflows by summarizing clinical notes and generating discharge summaries, potentially reducing the documentation burden on clinicians. Further research and evaluation are warranted to assess Me-LLaMA’s real-world effectiveness and limitations in these clinical application settings.

Despite these advancements, it is crucial to acknowledge the current Me-LLaMA models still have certain limitations that require further attention. Like all existing LLMs, they are susceptible to generating information with factual errors or biased information. To mitigate this, future studies could incorporate methodologies like reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF)17. This approach could align the models’ responses more closely with human values and ensure they are grounded in factual medical knowledge. Another limitation is the current token handling capacity, capped at 4096 tokens, which is a constraint inherited from the backbone LLaMA2 model. Addressing this limitation could involve extending the models’ capability to handle longer contexts. This could be achieved by integrating advanced attention techniques, such as sparse local attention18, that are able to handle extensive contexts.

Additionally, while MIMIC is the largest publicly available EHR dataset, its size is still relatively small compared to other data sources, which may impact Me LLaMA’s generalizability on real-world scenarios. This limitation stems primarily from privacy concerns surrounding clinical data, which significantly restrict the availability of large-scale EHR datasets. In this study, we included only MIMIC in the training of Me LLaMA because it is readily available for public dissemination through the established MIMIC data access procedures. Moving forward, we plan to train Me LLaMA on much larger proprietary clinical datasets, such as EHRs from Yale New Haven Health and the University of Florida Health. However, the terms of distribution and dissemination for models trained on such proprietary data will need to be carefully negotiated with our institutions’ data governance committees to ensure the safety and confidentiality of clinical data.

Methods

We utilized LLaMA26 as the backbone model and developed Me-LLaMA through the process of continual pre-training and instruction tuning of LLaMA2, using 129B tokens and 214 K instruction tuning samples from general, biomedical, and clinical domains. Figure 4 shows an overview of our study. Table 4 presents the comparison of Me-LLaMA models and existing open source medical LLMs.

Our study has three main components including pre-training, instruction fine-tuning and evaluation. Pre-training: we first developed the Me-LLaMA base models by continual pre-training LLaMA2 with 129 billion tokens from mixed pre-training text data. Instruction fine-tuning: Me-LLaMA-chat models were further developed by instruction-tuning Me-LLaMA base models with 214 K instructions. Evaluation: Finally, we evaluated the Me-LLaMA base models in a supervised learning setting across six text analysis tasks, and the Me-LLaMA-chat models in a zero-shot setting on both text analysis tasks and a clinical diagnosis task.

Continual pre-training data

To effectively adapt backbone LLaMA2 models for the medical domain through continual pre-training, we developed a mixed continual pre-training dataset, comprised of biomedical literature, clinical notes, and general domain data. Our dataset integrates a vast collection of biomedical literature from PubMed Central and PubMed Abstracts, sourced from the Pile dataset19. The PubMed Central subset includes 3,098,931 biomedical articles, and the PubMed Abstracts section encompasses abstracts from 15,518,009 documents. This comprehensive biomedical dataset provides a rich source of medical knowledge and research findings. To incorporate real-world clinical scenarios and reasoning, we included de-identified free-text clinical notes from MIMIC-III20, MIMIC-IV21, and MIMIC-CXR22. MIMIC-III contains 112,000 clinical reports records. MIMIC-IV contains 331,794 de-identified discharge summaries and 2,321,355 radiology reports. MIMIC-CXR adds further depth with 227,835 radiology reports for radiographic studies. Moreover, to prevent the model from forgetting acquired general knowledge, we incorporated a subset from the RedPajama23 dataset, a replication of LLaMA2’s pre-training data. This dataset is composed of diverse data slices, including processed CommonCrawl dumps, GitHub data, scientific articles from arXiv, a subset of Wikipedia pages, and popular websites from StackExchange. Our dataset was structured with a 15:1:4 ratio of biomedical, clinical, to general domain data and contains a total of 129 billion tokens, making it the largest pre-training dataset in the medical domain currently available.

Medical instruction tuning data

To enhance our model’s ability to follow instructions and generalize across diverse medical tasks, we further developed a novel medical instruction tuning dataset with 214,595 high-quality samples from a wide array of data sources. This dataset stands out from those used in existing medical LLMs due to its comprehensive coverage of both biomedical and clinical domains. Our data sources included biomedical literature, clinical notes, clinical guidelines, wikidoc, knowledge graphs, and general domain data, as shown in Table 5. The diverse tasks aim to refine the model’s ability to process and respond to medical information accurately and contextually. Detailed prompts for each data and the data example are shown in the Supplementary Information, Supplementary Table 1.

Training details

As shown in Fig. 3, we developed the Me-LLaMA 13B and 70B base models by continually pre-training the LLaMA2 13B and 70B models. These base models were then instruction-tuned to create the Me-LLaMA-13B-chat and Me-LLaMA-70B-chat models.

The first phase aims to develop Me-LLaMA base models, and adapt LLaMA2 models to better understand and generate text relevant to the medical context using the pre-training datasets we constructed. The objective is to enhance the model’s ability to understand and generate domain-specific text by optimizing it to predict the next word in a sequence based on the preceding context. This training was executed on the University of Florida’s HiPerGator AI supercomputer with 160 A100 80GB GPUs. We employed the AdamW optimizer with hyperparameters set to ({beta }_{1}) to 0.9 and ({beta }_{2}) to 0.95, alongside a weight decay of 0.00001 and a learning rate of 8e-6. We used a cosine learning rate scheduler with a 0.05 warmup ratio for gradual adaptation to training complexity and bf16 precision for computational efficiency. Gradient accumulation was set to 16 steps, and training was limited to one epoch. We utilized DeepSpeed24 for model parallelism.

We further fine-tuned Me-LLaMA base models to develop Me-LLaMA chat models, using the developed 214k instruction samples. In this phase, the models are trained to produce accurate and contextually appropriate responses to specific input instructions. Executed using 8 A100 GPUs, the fine-tuning process was set to run for 3 epochs with a learning rate of 1e-5. We used a weight decay of 0.00001 and a warmup ratio of 0.01 for regularization and gradual learning rate increase. We utilized LoRA-based25 parameter-efficient fine-tuning.

Evaluation benchmark

Existing studies2,3,9 in the medical domain have primarily focused on evaluating the QA task. In this study, we build an extensive medical evaluation benchmark (MIBE), encompassing six critical text analysis tasks: QA, NER, RE, Text Classification, Text Summarization and NLI. These tasks collectively involve 12 datasets meticulously sourced from biomedical, and clinical domains as shown in Table 6.

We further assessed the effectiveness of Me-LLaMA in diagnosing complex clinical cases, a critical task given the increasing burden of diseases and the need for timely and accurate diagnosis to support clinicians. Recent studies demonstrate that LLMs have the potential to address this challenge26. Specifically, we evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of Me-LLaMA on 70 challenging medical cases from the New England Journal of Medicine clinicopathologic conferences (NEJM CPCs) published between January 2021 and December 2022, as collected from an existing study27. The NEJM CPCs are well-known for their unique and intricate clinical cases, which have long been used as benchmarks for evaluating challenging medical scenarios. In line with previous research26,27, we employed automatic evaluations based on top-K (where k = 1,2,3,4,5) accuracy, defined as the percentage of cases where the correct diagnosis appeared within the top-K positions of the differential diagnosis list predicted by the assessed models. We utilized GPT-4o, a state-of-the-art (SOTA) LLM, to automatically assess whether each diagnosis from the model’s differential diagnosis list matched the gold standard final diagnosis, consistent with these prior studies. Existing studies27 have shown that LLM-based automatic calculation of top-K accuracy is comparable to human evaluation. Besides automatic evaluation, we had a clinician specializing in internal medicine perform a manual evaluation of top-k accuracy (k = 1, 5). For more details on data processing, automatic evaluation, and human evaluation, see the Supplementary Information.

Evaluation settings

We evaluated Me-LLaMA at two evaluation settings including zero-shot and supervised learning to evaluate their performance and generalization ability across various tasks compared to baseline models.

Supervised learning

In the supervised learning setting, we evaluated Me-LLaMA 13/70B base models’ performances adapted to downstream tasks. We conducted the task-specific finetuning on Me-LLaMA base models (Me-LLaMA task-specific) with each training set of assessed datasets in Table 6, and then assessed the performance of Me-LLaMA task-specific models on test datasets. We employed the AdamW optimizer. For datasets with fewer than 10,000 training samples, we fine-tuned the models for 5 epochs, while for larger datasets, the fine-tuning was conducted for 3 epochs. A uniform learning rate of 1e-5 was used across all datasets. Our baseline models including LLaMA2 Models (7B/13B/70B)6: they are open-sourced LLMs released by Meta AI. PMC-LLaMA 13B2 is a biomedical LLM continually pre-trained on biomedical papers and medical books. Meditron7B/70B9: these are medical LLMs based on LLaMA2-7B/70B, continually pre-trained with a mix of clinical guidelines, medical papers and abstracts.

Zero-shot Learning

We assessed our Me-LLaMA 13/70B-chat models’ zero-shot learning capabilities, which are key for new task understanding and response without specific prior training. We compared our models and baseline models’ zero-shot, using standardized prompts (detailed in the Supplementary Information, Supplementary Table 2) for each test dataset from Table 2. We compared Me-LLaMA 13/70B-chat models with the following baseline models: ChatGPT/GPT-44: SOTA commercialized LLMs. We used the version of “gpt-3.5-turbo-0301” for ChatGPT, and the version of “gpt-4-0314” for GPT-4. LLaMA2-7B/13B/70B-chat6 models were adaptations of the LLaMA2 series, optimized for dialogue and conversational scenarios. Medalpaca-7B/13B3 models were based on LLaMA-7B/13B, specifically fine-tuned for tasks in the medical domain. The PMC-LLaMA-13B-chat2 model is an instruction-tuned medical LLM based on PMC-LLaMA-13B. The AlpaCare-13B11 model is specifically tailored for clinical tasks based on LLaMA-2 13B by instruction tuning. Meditron 70B9 is a medical LLM, continually pre-trained with a mix of clinical guidelines, biomedical papers, and abstracts based on LLaMA2 70B.

Responses