Menopausal shift on women’s health and microbial niches

Introduction

The United Nations General Assembly has declared the period from 2021–2030 as the Decade of Healthy Aging1. Women’s biology, including hormonal and genetic factors, may offer some protection against age-related diseases. Women also tend to adopt healthier behaviors, such as seeking preventive healthcare and maintaining strong social connections, which positively impact their longevity2. However, despite their longer lifespan, women face unique health challenges as they age. Socioeconomic factors and cultural norms, such as lifestyle and nutrition, also affect their health and aging experiences. Therefore, it is essential to address gender-specific health needs and promote customized healthy aging strategies to improve the well-being and quality of life of aging women.

Menopause is the permanent cessation of spontaneous menstruation for 12 consecutive months resulting from the loss of ovarian follicular activity which typically occurs around age 50 but varies naturally between 40 and 59 years. Common symptoms include mucosal dryness, hot flashes, night sweats, weight changes, sleep and mood disturbances, and increased risks of cardiovascular, autoimmune, and bone disorders3. Additionally, oral health is compromised in menopause by both hypoestrogenism and aging of the oral tissues. It should be considered that the influence of aging, in addition to systemic diseases or medications, on the appearance of oral alterations will increase with age4. Complications arising from dry mouth sensation, temporomandibular dysfunction, and psychosomatic disorders are among the multiple causes of eating disorders observed in some menopausal women5. Alternatively, immunological compromise resulting from aging or estrogen decline may significantly influence the onset of oral infections.

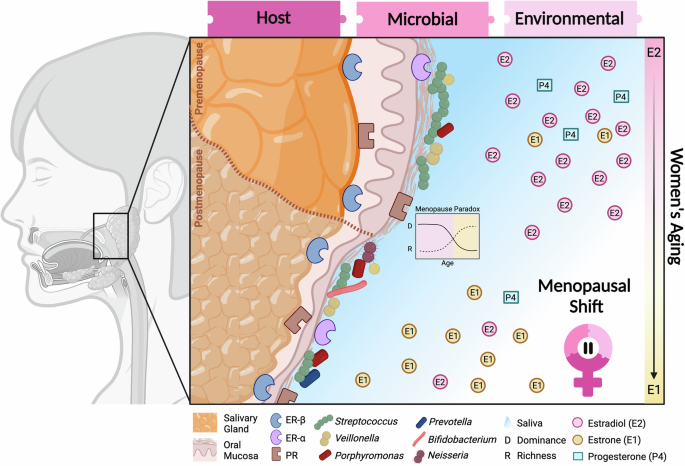

The human body is a complex community composed of host cells and microorganisms that live in symbiosis. Body niches (or human niches) are defined by the interactions between the host and its microbiota, shaped by environmental conditions6. Consequently, the host’s fitness depends on and cannot be seen separately from its microbiota. Although there are distinct human niches, the host must balance all body sites to maintain health. The microbiota loses balance when homeostasis is disrupted, also known as dysbiosis7. The microbiome plays an important role in various aspects of health. During menopause, hormonal changes can influence the composition and function of the microbiome, particularly in regions such as the oral, gut, vagina, and skin. Emerging evidence suggests that certain gastrointestinal microorganisms can directly metabolize sex hormones such as estrogen and progesterone8. In this narrative review, we introduce the concept of menopausal shift, which includes physiological and histological changes in the host, leading to alterations in the composition and metabolism of the resident microbial community due to hormonal changes during the aging of women (Fig. 1). Therefore, exploring the complex interrelation between the microbiome and menopause reveals promising avenues to mitigate menopausal symptoms and improve overall health. Strategies that include diet modifications, probiotics, and personalized microbiome-targeted interventions offer the potential to optimize health outcomes among women’s aging.

Host: Histological changes represented in the salivary gland and oral mucosa could be found at other body sites such as epithelium thinning and tissue atrophy. Hormone receptors can be detected in hormonal/sensitive tissues as the mucosal lining of the gastrointestinal tract, and the female urogenital system. Microbial: Changes in microbiome diversity (distribution of microbial species) and richness (number of species) modified by interaction with host tissues, hormonal metabolism, and environmental changes during menopause. Oral bacteria are not restricted to mucosal niches but also inhabit other oral sites like the gums or tongue. They are considered part of the resident oral microorganism community capable of metabolizing sex steroid hormones. The menopause paradox, characterized by a decrease in microbial dominance but an increase in richness observed in the vaginal niche, may apply to other body sites within the microbiome community. Clinically, changes in microbial fitness can contribute to health problems such as infections. Environmental: Physiological changes include a reduction in salivary fluid. and a shift in the predominant plasma estrogen, from estradiol (produced in the ovary) to estrone (originated by aromatization of adrenal androgens in adipose tissue), accompanied by a marked decrease in progesterone levels during the transition from menopause. Figure created using BioRender.com.

Biological transitions during menopause

Environmental: physiological changes in menopause

Estrogen, primarily in the forms of estradiol and estrone, undergoes significant variations across different stages of life, from puberty to menopause. During reproductive years, estradiol is the most potent and prevalent form of estrogen, exhibiting cyclical fluctuations aligned with the menstrual cycle, peaking at ovulation. This hormone plays a crucial role in reproductive functions, influencing systemic health, maintaining bone density, cardiovascular health, sexual health, mood regulation, and cognitive well-being. However, with the onset of menopause, there is a marked shift in estrogen dynamics. The decrease in ovarian function results in a decrease in estradiol production, leading to estrone becoming the dominant estrogen form. Unlike estradiol, estrone is synthesized in adipose tissue and serves to maintain certain estrogenic activities after cessation of ovulation. However, overall estrogenic activity diminishes during postmenopause (after menopause). Several studies have associated this decline with increased risks of osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and cognitive impairments3. This period reflects the complex interplay of estrogens throughout a woman’s life, with estrone providing a residual, but inadequate, estrogenic effect in the absence of higher estradiol levels. These fluctuations in female hormone levels may be responsible for the physical and psychological symptoms experienced by women during the menopausal transition that compromise their well-being.

Oral fluids naturally contain hormones9. In the oral cavity, salivary and gingival crevicular fluids (GCF) play an important role in maintaining health integrity10. Saliva and GCF share some metabolites and pathways but also have unique compositions. Salivary is primarily composed of water, minerals, electrolytes, hormones, enzymes, immunoglobulins, and cytokines11. The physiological level of saliva is fundamental for oral health since it influences various factors in the oral cavity, such as protection against caries, immunological processes, and digestion12. Saliva has a highly active natural estrogen secreted by the ovary, 17β-estradiol, progesterone, and estrone13,14. The detection of estrogen-β receptors in salivary gland acinar and ductal cells suggests estrogen deficiency as the etiological agent for the variations in salivary secretion and inorganic composition observed in menopausal women. The composition and flow of saliva can also be influenced by certain medications such as antidepressants, antihypertensives, oral antiseptics, and cancer therapies.

Hormonal deficiency could lead to quantitative and qualitative saliva variations, altering oral homeostasis, which affects the oral microbiota and leads to bacterial colonization. Changes in salivary pH and flow rate in postmenopausal women directly contribute to an increase in oral diseases15. However, there is a controversial relationship between salivary pH and age16. The concentration of hydrogen ions increases with age in patients, placing them in more acidic environments. Salivary pH in menopausal women has been reported to have lower values in postmenopausal women compared to premenopausal women, while others have found no significant changes in salivary pH between different groups16,17,18. A case-control study published in 2018 (n = 80) revealed that postmenopausal women (n = 40) showed decreased salivary flow and pH compared to the control group (n = 40)19. Then, hormonal changes during menopause can lead to a more acidic pH in women, increasing the risk of oral tissue damage along with aging. However, other body sites have a pH increase that leads to bacterial infections.

In contrast, the gingival sulcus contains serum-derived gingival crevicular fluid (GCF)20. The gingival fluid contains estradiol and progesterone, and its fluctuation affects the gingival tissues21. Estrogen decreases keratinization, increases epithelial glycogen, and affects fibroblast proliferation and protein production. Progesterone enhances vascular permeability, reduces glycosaminoglycan synthesis, changes collagen production rate and pattern, and inhibits IL6 production. Female steroid hormones exert a pro-inflammatory effect on the gingiva10,22,23. There are periods of gum inflammation such as gingivitis, which in turn is related to an increase in alteration of the microanatomy and the gingival and subgingival bacterial population24. Although estradiol levels decrease drastically during menopause, another estrogen form such as estrone might impact the gingival tissue. As the gingival environment hosts a resident microbial biofilm community and saliva contains a transient planktonic microbiota, both oral environments can influence host-microbial interactions during hormonal fluctuations. Therefore, it is essential to investigate whether oral fluids contain various concentrations of hormones and forms accessible to the microbiota.

Host: histological changes in menopause

Ovarian hormone receptors are found in the mucosa of the nasopharynx, the gastrointestinal tract, and the female urogenital system25. The action of sex hormones influences the tissues of the oral mucosa, gingiva, and salivary gland tissues26. The hormonal variation that occurs in menopause produces a vasomotor alteration that implies changes in vascular permeability and inflammation mediators. Estrogens and progesterone regulate the mucosal barrier and the immune response of the female reproductive tract, which can cause vaginal symptoms if their levels are altered. The most common vaginal symptoms associated with menopause are vaginal dryness due to estrogen deficiency and thinning of the vaginal epithelium, losing its defense elements27,28. Some of the most common pathologies are vulvovaginal atrophy, recurrent urinary tract infections, bacterial vaginosis, and vaginal candidiasis29. As a result, burning, itching, and stinging appear in the vaginal area.

The oral and vaginal epithelium show similarities at the microscopic level, regarding their ultrastructure, distribution of their keratin filaments, permeability to water, and chemical composition. This is particularly noteworthy as the vaginal epithelium undergoes various changes during and after menopause, suggesting potential implications for the oral epithelium30. Furthermore, several studies have found no significant differences between the number of epithelial cell layers of both mucosae. Similarly, the keratinization patterns and the distribution of lipid lamellae in intercellular spaces are similar. All of this suggests that given their microscopic similarities, the changes observed in the vaginal mucosa due to the lack of hormonal stimulation in postmenopausal women can also affect the oral epithelium in the same way27,30. It has been suggested that the composition of the oral, vaginal and intestinal microbiota may be regulated by estrogen levels6. Consequently, a decrease in sex hormones has been found to elicit an increased inflammatory response in the host, potentially precipitating dysregulation in the equilibrium of the oral microbiota31. Therefore, this can result in various gingival pathologies, with menopausal gingivostomatitis being particularly prominent.

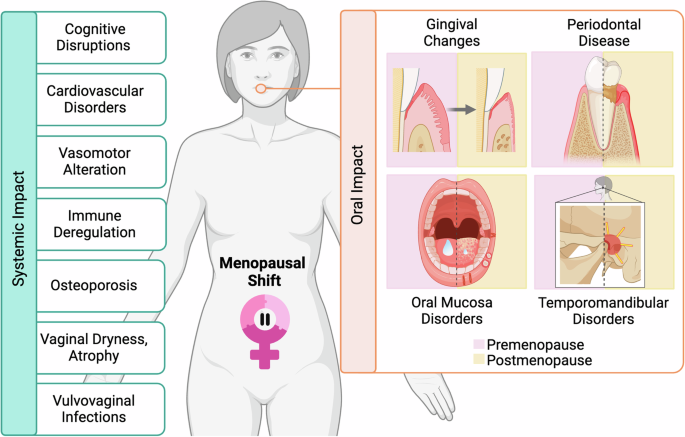

Within the oral cavity, both the gingiva and salivary glands harbor sex steroid receptors that act as mediators of hormonal effects in oral tissues25,26. Salivary glands, like breast glands, express the estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), while ER beta (ERβ) is found specifically in the gingiva32. ER-α is expressed predominantly in the target tissues of classical structures such as the mammary glands and endometrium. In contrast, ER-β is expressed mainly in tissues that have recently been identified as a stress target, such as the oral and colonic epithelium33. Furthermore, progesterone receptors (PR) have been found in salivary glands and gingival fibroblasts34,35,36. Menopausal women may be more susceptible to changes in salivary flow since acinar and ductal cells in the salivary gland have hormonal receptors, especially the minor, parotid, and submandibular glands25. The drastic drop in sex hormone levels after menopause, particularly estrogen levels, has numerous implications for the nervous, cardiovascular, rheumatic, endocrine, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary tract (Fig. 2). In premenopausal women, sex steroid hormones demonstrate direct vasodilatation action via their receptors, signaling their cardiovascular benefits. In younger women, estrogens contribute to cardioprotection, a function that diminishes after menopause37. Another prevalent disease in menopause is osteoporosis, although its etiology is complex3. At this stage, hormonal fluctuations and altered calcium metabolism can lead to increased levels of bone resorption, making this disease more prevalent after menopause.

Main systemic changes (left panel) and oral (right panel) disorders. Figure created using BioRender.com.

Oral impact of menopausal shift

During menopause, a series of physiological changes occur, mainly due to the decline of estrogens, a consequence of female reproductive aging38. This marked hypoestrogenism affects the stomatognathic system and the rest of the systems, generating various general and oral clinical manifestations that compromise the well-being of women (Fig. 2). Numerous studies have explored the association between oral conditions and systemic manifestations during menopause, revealing a positive correlation39.

Periodontal disease is a chronic bacterial-originating inflammatory disease that destroys the supporting dental tissues, ultimately leading to tooth loss. It is a multifactorial etiological pathology caused by the interaction of a necessary but insufficient primary etiological factor, a susceptible host, and environmental factors that influence both40. Sex hormones are considered important modifying factors that can increase host susceptibility to periodontal pathogens and therefore affect the prevalence, progression, and severity of periodontal disease41. Significant fluctuation in sex hormone levels along with characteristic menopausal osteoporosis has led several studies to link menopause and periodontal disease.

Osteoporosis may be responsible for the lower density of the alveolar crest bone per unit volume, which would promote faster bone loss in response to the resorption stimulation provided by periodontal infection42. Based on this hypothesis, a study conducted in postmenopausal women did not correlate a lower systemic mineral density with a greater loss of periodontal attachment in response to oral infection, although it was observed that the association became significant with older age of the patients43. However, subsequent studies have reported a higher prevalence of periodontal disease in postmenopausal women than in premenopausal women and a similar periodontal status between premenopausal women and postmenopausal women who received menopause hormone therapy (MHT)44. Some have even pointed to MHT as a protective factor for dental pain, improved dental mobility, and the depth of the probing of the periodontal pocket45. Recently, the prevalence and associated factors of tooth loss in postmenopausal women have been explored. The main contributing factors are poor oral hygiene and low bone mineral density46. Although some studies suggest a positive correlation between hypoestrogenism-osteoporosis and greater tooth loss, more research is needed to define the relationship between menopause and periodontal disease, considering confounding factors associated with both conditions, such as advanced age, education, chronic diseases, tobacco and alcohol consumption, and especially oral hygiene and diet.

Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) are a group of musculoskeletal disorders that affect the masticatory muscles and the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). The higher incidence of TMD in women than in men and the detection of estrogen and progesterone receptors in the TMJ disc have led to consideration of the role of female sex hormones in the multifactorial etiology of this joint disorder47. Some authors have observed a higher prevalence and severity of TMD in postmenopausal women than in premenopausal women48. In this regard, a study conducted in women with TMD and different menstrual cycle states concluded that the degree of chronic pain related to TMD, masticatory dysfunction, depressive symptoms, and somatization was greater when estrogen levels were lower49. However, other researchers evaluated the presence of TMD in postmenopausal women and their relationship with pain and the use of MHT and found no relationship between TMD and postmenopause, nor between the use of MHT and TMD pain50. These contradictory results require further studies to understand the effects of menopause on TMJ.

Estrogen deficiency could be related to changes in saliva secretion in menopausal women due to altered salivary tissues39,51. Hyposalivation is related to changes in the oral cavity, such as loss of brightness of the oral mucosa, dryness of the mucous membranes, fissures on the back of the tongue, angular cheilitis, thick saliva, increased frequency of oral infections, presence of caries in atypical places, and increase in the size of the main salivary glands52. Postmenopausal women commonly experience oral symptoms, including dryness, burning sensation, mouth pain, taste changes, and tooth loss, often accompanied by difficulties swallowing, phonation, and halitosis53. Dry mouth or xerostomia is the main oral symptom during peri and postmenopause, with most patients reporting a decrease in salivary flow54. Salivary progesterone levels are directly correlated with the sensation of oral dryness in menopause15. However, it remains unclear whether dryness is only associated with a hormonal decrease, as other factors such as medication or aging also influence salivary rate.

The sensation of oral dryness is often accompanied by burning mouth syndrome (BMS), which is also related to fungal infections such as oral candidiasis in postmenopause55. Emotional instability, particularly evident in patients with BMS characterized by pain and burning of the oral mucosa, is related to psychological disorders such as depression or anxiety, underscoring the multifaceted nature of menopausal oral health concerns51. Furthermore, there is an increase in facial, dental, and temporomandibular complaints and ulcerations56. In general, decreased saliva flow leads to other symptoms such as bad or altered taste, dysphagia, viscous saliva, oral mucositis, lichen planus, stomatitis, and pemphigoid. Therefore, it is important to address oral disorders in aging women by creating preventive oral care programs and specific therapeutic interventions tailored to menopause.

Microbial: microbiome in menopause

Oral microbiome

It has specific body sites (or human niches) defined as the host-microbiota interaction shaped by environmental conditions57. Oral microbiomes are complex ecosystems of microorganisms that live in the oral cavity and are in soft and hard tissues, including teeth. Hormonal changes can influence interactions between this microbial community and the host58. The oral microbiome is sensitive to changes in the oral environment, and hormonal fluctuations can create conditions that favor the growth of certain types of bacteria over others. Detecting systemic changes in hormone levels in health and disease by analyzing the oral microbiome could be relevant when hormone changes affect the oral microbiome. Hormonal fluctuations, such as those that occur during puberty, menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause, can affect the oral cavity. For example, hormonal changes can affect saliva production and alter its composition, which can influence the oral microbiome59. In menopause, naturally occurring alterations in hormone levels could also impact the resident microbial community.

Salivary flow and composition have a controversial link to menopause. The AMICA project compared the oral microbiome in saliva of 20 postmenopausal women with the control group (n = 19 women of reproductive age). The study did not find significant differences in the composition of the oral microbiome in saliva between menopausal women and those with a regular menstrual cycle60. The most abundant bacterial genera were those already known to be predominant in healthy individuals, such as Streptococcus, Neisseria, Porphyromonas, Prevotella, and Veillonella60. In contrast, Teles and cols. identified that the dominant families of the study population were Prevotella and Streptococcus61. Specifically, Prevotella copri was significantly higher and Veillonella tobetsuensis decreased after menopause39. Furthermore, women who experience severe hyposalivation have similar bacterial profiles compared to those with normal salivary flows. Significant metabolite changes were identified in postmenopausal women’s saliva, with estradiol levels positively related to unstimulated salivary flow60. Another study identified differences in salivary composition related to hyposalivation within aging women, particularly focusing on the oral microbiome59. The findings suggest that decreased estradiol levels due to reduced salivary flow can cause oral problems in menopause and alter certain oral bacteria. Further investigation with extensive population and longitudinal studies will elucidate the impact of the menopause transition in salivary environments.

Salivary cortisol is a biomarker used to examine the response to human stress62. Psychosomatic head and neck disorders such as aphthous stomatitis, atypical facial pain, oral lichen planus, BMS, and xerostomia have been associated with the menopausal stage. In a clinical trial that included 200 postmenopausal women, saliva cortisol levels were revealed to be statistically significant, demonstrating higher levels in postmenopausal women with psychosomatic disorders62. A recent metatranscriptomics functional analysis on the effect of stress-related cortisol on the oral microbiome identified that members of the Fusobacteria phylum become more active in the presence of cortisol63. Interestingly, Leptotrichia goodfellowii, previously related to gingivitis, was substantially more dynamic. In general, exposure to cortisol in the oral microbiome can change the activity of the entire bacterial community61. Some of these changes include overrepresentation of the host’s immune response against oral bacteria and increase in proteolysis, oligopeptide transport, iron metabolism, and flagella assembly on the bacterial side. These activities have previously been associated with functional dysbiosis and the progression of oral diseases, such as periodontal disease63. This raises the interesting possibility that oral microorganisms may respond directly to the presence of stress hormones.

Biofilm-associated periodontal disease is a common oral disease in aging and menopausal women. The subgingival microbiome of postmenopausal women has been correlated with the presence and severity of periodontal disease. Some of the most characteristic pathogens associated with this disease belong to Bacteroides, Tannerella forsythia, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Spirochetes, Treponema denticola, Bacteroidales, and Fusobacterium24. The interactions between Firmicutes and Bacteroides can be a good indicator of microbial habitat in aging patients. A trend toward a higher proportion of Firmicutes to Bacteroides has been described in menopausal women61,64. Specific species survive within the subgingival microbiome of menopausal women regardless of the existence or severity of periodontal disease. In particular, these include Veillonella dispar, Veillonella parvula, Streptococcus oralis, and Bifidobacterium dentium61. Studies have indicated that the presence of B. dentium can inhibit P. gingivalis proliferation, a notable pathogen implicated in periodontal disease65. This observation may provide insight into why P. gingivalis was detected at relatively low levels in a cohort of aging women without periodontal disease. The oral microbiome changes during menopause, with specific pathogens contributing to periodontal disease in aging women. Despite this, certain species persist in the subgingival microbiome of menopausal women, potentially influencing periodontal health.

The gingival crevicular fluid is a periodontal exudate composed of serum containing various metabolites that interact with the resident periodontal microbiota66. Clinically, increased periodontal inflammation has been associated with hormonal dysregulation situations such as pregnancy and estrogen-dependent diseases such as endometriosis67. Consequently, many subgingival organisms associated with periodontal disease in older women were comparable to the subgingival microbiota observed in studies of young individuals with periodontal disease. A notable exception is the absence of A. actinomycetemcomitans, associated with aggressive periodontitis, which is rare in older adults22. These findings suggest complex dynamics between the oral microbiome and menopause, with implications for research and therapy.

Although previous studies focused on bacterial species, it is essential to recognize the role of commensal fungal populations in the oral microbial’s complexity. During menopause, the proliferation of fungi increases due to aging and hormonal imbalance, leading to dysbiosis and the proliferation of opportunistic species such as Candida albicans, particularly in the postmenopausal stage68. Antibiotics, local or systemic immunosuppression as chronic use of systemic or inhaled steroids, hyposalivation, diabetes mellitus, and smoking contribute to the development of candidiasis.

Chronic candidiasis can cause a burning sensation in the mouth, a characteristic symptom of burning mouth syndrome (BMS), sharing significant factors such as chronic use of medications and the presence of removable prostheses. However, while C. albicans has been detected in 45.16% of postmenopausal women with BMS, but its association with the etiology of the syndrome remains inconclusive51,69. Physiological parameters such as pH and salivary flow did not significantly influence the presence of C. albicans, suggesting a complex interplay of factors in its colonization. Although the distribution of Candida species varied between samples, physiological changes during menopause could contribute to fungal proliferation. Thus, menopause does not directly increase the risk of oral candidiasis70. Although no association was observed between salivary flow and C. albicans invasion in postmenopausal women, the previous literature suggests a potential link, possibly influenced using proton pump inhibitors that affect the oral microbiota. Recent research has identified Candida glabrata as an opportunistic pathogen responsible for mucosal and systemic infections, often found in elderly, immunosuppressed individuals, and settings associated with healthcare71. More research is needed to elucidate the intricate relationship between salivary flow, hormonal changes, and fungal colonization during menopause.

The menopause microbiome beyond the oral niche

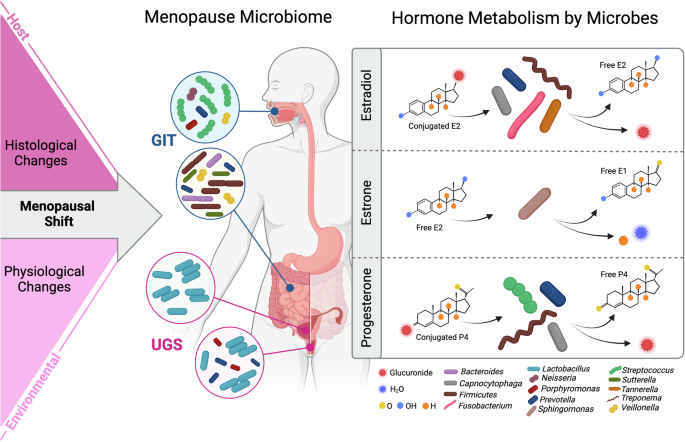

Mucosal receptors for ovarian hormones have been found in the brain, oral cavity, nasopharynx, gastrointestinal tract, and female urogenital system22 (Fig.3). This suggests that the composition of the nervous system, oral, intestinal, vaginal, and bladder microbiome can be regulated systemically by sex hormonal levels72. Although markedly different ecosystems, some bacterial species sensitive to hormonal changes may be present in different tissues, such as those of the oral, intestinal, and genitourinary body sites73 (Fig. 3). For example, some strains of Lactobacillus have been found to colonize the mouth, vagina, and rectum simultaneously and may pass from the intestine to the vagina through the peritoneum74. The hormonal transition to menopause could manifest different host-microbiota interactions at specific body sites.

Hormonal fluctuations induce changes in the characteristics and functions of host tissues and body fluids, altering the environment for microbial communities. Menopause microbial niches include oral and intestinal as gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and female reproductive tract and urinary sites as urogenital system (UGS). Metabolism of sex steroid hormones by resident human microorganisms can influence their availability in the body, potentially leading to alterations in hormonal levels and impacting overall health. Figure created using BioRender.com.

The intestinal microbiome

Emerging evidence suggests that the gut microbiome could significantly contribute to hormone-related alterations observed in women’s aging, particularly during the transition to menopause75. Since the gastrointestinal tract is understood from the oral to the anus, the bacterial communities observed in the intestine may be related to the oral community and vice versa8. The diversity of the microbial community’s α-diversity, determined by the distribution of microbes within a sample, encompasses both the count and the relative abundances of the taxa present. Studies indicate that menopause is associated with alterations in the diversity of the gastrointestinal microbiota due to declining hormone levels76,77. However, contrasting findings suggest that there are no discernible differences between pre- and postmenopausal women27,78,79,80.

The changes suffered in the intestinal microbiome throughout women’s aging are getting attention from researchers. A longitudinal study found that the intestinal microbiome in postmenopausal women (n = 1027) was less diverse than in premenopausal women (n = 295). Furthermore, they found that postmenopausal women had a higher abundance of Bacteroides sp. Ga6A1, Prevotella marshii, Veillonella dispar and Sutterella wadsworthensis76. Genera Prevotella and Sutterella have previously been associated with obesity in other studies81. Similarly, intestinal Bacteroides can have beneficial or harmful effects depending on the relationship with other microbiomes and host factors82. Microorganisms that find the appropriate conditions in the mouth, such as Prevotella, Bacteroides sp, and Firmicutes, produce different types of community at the gastrointestinal level. Furthermore, a lower abundance of Escherichia coli-Shigella spp., Oscillibacter sp. KLE1745, Akkermansia muciniphila, Clostridium lactatifermentans, Firmicutes, Abiotrophia, Parabacteroides johnsonii, and Veillonella seminalis75. It remains unclear whether changes in hormonal levels during the transition to menopause could affect the balance of the intestinal microbiota, potentially resulting in dysbiosis.

Sexual dimorphism in the intestinal microbiome refers to the differences between men and women in microbial composition and diversity. While there is no sex disparity in the intestinal microbiota before puberty, a notable change occurs after puberty, characterized by a general reduction in microbial diversity in men compared to women. Specifically, women exhibit a higher gut microbiome richness and a lower abundance of Prevotella compared to men8,83,84,85. The intestinal microbiota of postmenopausal women exhibited a greater similarity to that of men compared to premenopausal women76,78. However, the impact of Prevotella on human health is conflicting, as its effects vary depending on the specific strains involved.

The community of microorganisms that reside in the digestive tract performs multiple functions, such as metabolism of dietary components, synthesis of lipopolysaccharides from Gram-negative bacteria (involved in inflammation), and metabolism of endogenous components, including female hormones86. After menopause, an increased incidence of autoimmune diseases has been observed87. Ruminococci, of the genus Clostridia, are producers of short-chain fatty acids, as they have neuroactive properties that allow communication of the brain-gut axis, being a beneficial function88,89,90. A reduced abundance of some Ruminococcus species has been observed in patients with Crohn’s disease and systemic Lupus erythematosus91,92. Highlight, a lower abundance of Ruminococcus has been associated with postmenopausal women compared to premenopause78,93,94.

Since cardiovascular disease is one of the leading diseases in aging women, recent research evaluated the role of the gut microbiome in hormone-related cardiovascular protection95. A large postmenopausal cohort collected stool samples and serum levels of 15 sex hormones, finding estrogen associated with higher diversity and abundance of Alistipes, Collinsella, Erysipelotrichia, and Clostridia. Interestingly, they suggested that the connection between estrone and carotid artery plaque may be influenced by the gut microbiome. However, the presence of HIV in 81% of the women included in the study could potentially disrupt the direct correlation between sex hormones and the microbiome. On another note, progesterone reduces immune system activity, leading to increased vulnerability to pathogens96. Progesterone levels decrease concomitantly with estrogen after menopause. Plasma progesterone concentration in postmenopausal women predicted circulating progesterone levels according to the composition of the gut microbiome78. Establishing the specific role of these bacteria in the intestinal microbiome and their relationship to menopause is challenging due to the lack of mechanistic studies. Therefore, the specific health implications of the gut microbiome in the aging of women are not well understood.

Urogenital microbiome

The vaginal microbiome undergoes profound changes during menopause, affecting women’s health and susceptibility to various infections. Specifically, at the vaginal level, this imbalance can trigger chronic inflammation, which could contribute to an elevated risk of certain infectious disorders such as atrophic vaginitis, pelvic vaginitis, bacterial vaginosis, genital candidiasis, sexually transmitted infections, and HIV27. A persistent state of inflammation and associated infections can also increase the likelihood of malignant transformations, thus increasing the risk of carcinogenesis97. This underscores the potential implications of menopausal hormonal changes on vaginal health and associated risks.

Recent studies show that changes in the reproductive microbiome during menopause are linked to higher risk of endometrial cancer (EC). Walsh et al. 98 found that the microbiome becomes more diverse in postmenopausal women, which may increase disease risk98. Specifically, Porphyromonas somerae and Atopobium vaginae were more common in women with EC. Additionally, Porphyromonas gingivalis, associated with Alzheimer’s and periodontal diseases, is closely related to P. somerae suggesting that Porphyromonas species may play a role in disease during menopause.

Microbiome fitness refers to the health and resilience of the microbial community in specific environments like the gut, or oral cavity. A healthy microbiome is diverse, and composed of beneficial microorganisms that support host health, while an imbalanced microbiome may lead to disease. In the healthy vaginal microbiome, Lactobacillus species are typically the predominant bacteria producing lactic acid and creating an acidic environment that helps prevent the overgrowth of harmful bacteria. This dominance is important for maintaining vaginal health and preventing infections.

Menopause paradox contrasting trends observed in the vaginal microbiome between premenopausal and postmenopausal women. The menopause paradox describes a phenomenon in menopausal women characterized by a decrease in Lactobacillus dominance and an increase in microbial richness in the vaginal microbiome. As a result, the vaginal microbiome in postmenopausal women may become more diverse, adapting to a broader spectrum of microbial species within the niche. Host and environmental changes contribute to the paradoxical relationship between dominance and richness in menopausal women, including changes in hormone levels, vaginal pH, and host immune response. From a clinical perspective, this paradox can lead to health issues like infections due to changes in microbial fitness, emphasizing the importance of addressing these microbiome shifts in menopausal women’s healthcare99.

First, hormonal changes associated with menopause can alter the vaginal environment, affecting microbial communities. The decline in estrogen levels during menopause leads to changes in vaginal pH and moisture levels, creating an environment that contributes less to the growth of certain microbial species, particularly Lactobacillus, which are dominant in premenopausal women. The vaginal microbiome is classified into five types of community state (CST), determined by the presence and abundance of Lactobacillus species. CST I is characterized by the predominance of L. crispatus, while CST II, III, and V are dominated by L. gasseri, L. iners, and L. jensenii, respectively. In contrast, CST IV lacks Lactobacillus and includes anaerobic microbes such as Prevotella and Gardnerella Gardnerella100,101.

Postmenopausal women experience reduced Lactobacillus levels, increasing microbial diversity102. However, this may lead to enhanced susceptibility to anaerobic bacterial colonization, associated with infections. When the bacterial diversity increases, the detected species include Prevotella, Porphyromonas, Peptoniphilus, Anaerococcus, Peptostreotococcus, Dialister, Atopobium, Gardnerella, Megasphera, and Bacillus, some are associated with certain vaginal infections, such as bacterial vaginosis (BV)28. Clinical research demonstrates that the anaerobic overgrowth characteristic of BV is related to the microbiota of postmenopausal women compared to premenopausal women. Furthermore, a correlation has been described between a vaginal flora dominated by non-Lactobacillus and vaginal dryness97. Women with more severe signs and symptoms of vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and vaginal pain tend to have a greater diversity of the vaginal microbiota that is not predominantly Lactobacillus. The Prevotella and Porphyromonas species are constituents of the female genital tract and the oral cavity, contributing to polymicrobial infections such as bacterial vaginosis and oral periodontitis103.

Furthermore, differences in immune function and vaginal health between pre- and postmenopausal women can also contribute to the paradox of diversity and richness. Changes in immune response and vaginal epithelial integrity can influence microbial colonization patterns and community structure102. Lactobacillus species protect a woman against invading pathogens by lactic acid fermentation, promoting vaginal and bladder health. The most significant difference between pre- and postmenopause is the decrease in Lactobacillus levels. The main metabolic pathways of Lactobacillus are lactic acid and glycogen. Lactobacillus contributes to microbial equilibrium by eradicating dysbiotic microorganisms and various pathogens through lactic acid, a primary antibacterial agent38. Lactobacillus primarily produces lactic acid, which decreases markedly in postmenopausal vaginal fluid with higher pH compared to premenopausal levels. The lactic acid analysis revealed that the premenopausal group exhibited a lactic acid count of 98%, representing a substantial portion of the total. In contrast, in the postmenopausal group, the lactic acid concentration decreased markedly to 94.2%102. Higher levels of estrogens promote the accumulation of glycogen in the vaginal epithelium, promoting the dominance of Lactobacillus104. Increased free glycogen levels promote a thicker stratified squamous epithelium and a protective mucus layer, which is also correlated with higher Lactobacillus levels105. During premenopause, free glycogen levels in the vaginal mucosa are significantly higher than during postmenopause106. In contrast, estrogen levels drop drastically, so the vaginal microbiota and epithelium could be affected. Postmenopausal women have lower Lactobacillus levels, perhaps due to a decrease in accessible estrogen-dependent glycogen. Furthermore, in women with vaginal atrophy, the bacterial microbiota is absent28.

The genitourinary system is closely related to the vagina. The vaginal microbiome interacts with other microbial communities in the urinary and gastrointestinal systems. Vaginal Lactobacillus may be protective in the urinary tract74. Furthermore, the urinary tract may act as a reservoir for vaginal Lactobacillus and may help recolonize after dysbiosis, produced by some metabolic change or pathology associated with menopause. Among the Lactobacillus species, L. jensenii, also commonly found in the urethra, along with L. iners and L. crispatus, is the most frequently isolated in the vagina107. The correlation between Lactobacillus abundance in the vagina and its presence in the urethra is striking. Consequently, promoting Lactobacillus colonization in the vagina can positively impact its presence in the urinary system, thus playing a vital role in women’s health, especially postmenopause.

Urogenital complications are experienced by one-third of women 50 years or older. The urinary system may also be affected due to mucosal dryness. Genitourinary symptoms such as dyspareunia, dysuria, and recurrent urinary tract infections (UTI) can appear101. There is a pathology called genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) that affects approximately 50% of menopausal women, again affecting the sexual and functional health of women101. Menopause induces changes in the vaginal microbiome that result in vaginal symptoms28. A study in 2021 identified Prevotella and Porphyromonas, which are classical periodontal pathogens, as microorganisms associated with UTIs treated with antibiotic therapy101. A cross-sectional study in 2013 (n = 87) demonstrated that mild or moderate vulvovaginal atrophy shows a greater diversity in the microbiota in the absence of Lactobacillus than in women without vulvovaginal atrophy who showed a microbiota dominated by Lactobacillus crispatus72. Thus, the complexity of vaginal microbiome dynamics and the need for a multifaceted approach to elucidate the underlying mechanisms. Future research should employ longitudinal studies and advanced omics technologies to unravel the intricate interactions between host physiology, microbial composition, and environmental factors in shaping the vaginal microbiome during menopause. By gaining more insight into these dynamics, we can develop targeted interventions to promote vaginal health and mitigate the risk of infections in menopausal women.

Hormone-microbiome crosstalk in women´s aging

Estrogen is the primary sex hormone associated with endocrinological transitions in women, including puberty, pregnancy, and menopause108. Although microbiome diversity decreases as we age, other factors dictate the microevolution of the microbial community at each body site, such as diet, habits, host defenses, and hormonal levels. During the menopause transition, women’s mucosal tissues are thin and dry, leading to dysbiosis in vaginal and oral bacteria that can be mitigated by menopausal hormone therapy60. The microbiome and sex hormones have a dynamic bidirectional interaction that changes with intrinsic factors such as aging (Fig. 3). Estrogen levels in the human body are regulated through a balance between free estrogen, which can be directly utilized by cells and estrogen bound to proteins (conjugated estrogen) with a half-life longer than the former, serving as a reservoir of available estrogen. Estrobolome bacteria can deconjugate estrogen and transform it into its active form, thus able to bind to estrogen receptors and affect all estrogen-dependent processes72,109. This is defined as the collection of microorganisms and their genes capable of metabolizing estrogen. Recently, the ability of gastrointestinal tract bacteria to metabolize protein-bound estrogen has been described using the bacterial enzyme β-glucuronidase105,110. Free estrogen can be transported to many sites, such as the vagina, and promote Lactobacillus dominance in the microbiota72. Therefore, microorganisms metabolizing sex hormones could change host control in availability and, thus, physiological processes related to hormones. However, it remains unclear how the microbial genes interact with the host in aging or hormonal fluctuation at multiple body sites.

Estrogen levels during menopause decrease due to reduced ovarian production. During the menopausal transition period, sex hormones can increase, leading to inflammation of oral tissues and microbial dysbiosis in gingival tissues. Furthermore, in other regions of the gastrointestinal tract, such as the intestine, estrogen levels have a regulatory effect on host-microbiota balance111. The oral-gut-estrobolome axis suggests a connection between systemic estrogens and oral health109. Certain microorganisms in the oral microbiota can also modulate steroid hormone levels by degrading and metabolizing them. Thus, early signs of estrogen-related issues may manifest as oral dysbiosis, highlighting the importance of monitoring oral bacteria. For example, in vitro studies have shown that progesterone has a dose-dependent bacteriostatic or bactericidal effect against Neisseria and Staphylococcus spp, bacteria found in the oral microbiota of humans. Other species such as Treponema denticola use steroids derived from the host as growth factors, a phenomenon that can be related to its virulence112. Similarly, estrogen and progesterone act as replacement growth factors for the K vitamin, an essential nutrient for Bacteroides species such as Prevotella intermedia, Prevotella nigrecens, and Capnocytophaga, which increases in gingival tissue concomitantly with estradiol and progesterone cycles113. A recent study investigated the impact of estradiol, estriol, progesterone, or testosterone on in vitro oral biofilms to induce the expression of virulence factors. The study revealed minimal effects on biofilm formation, microbial composition, and proteolytic activity114. In oral gingival tissues, the gingiva contains a receptor capable of specifically binding estrogen, and its microbiota has β-glucuronidases (GUS) as estrogen-metabolizing enzymes. The GUS atlas derived from the human oral microbiome was associated with 53 unique GUS enzymes. Many of these enzymes were identified in genera commonly associated with periodontal disease, such as Tannerella, Treponema, Prevotella, and Fusobacterium. In particular, the GUS proteins found in the oral microbiome were different from those found in the gastrointestinal tract115. However, the precise mechanisms underpinning the influence of sex hormones in oral niches remain a subject of ongoing exploration.

Estrone is a critical estrogen hormone during menopause, primarily produced by extraovarian tissues as ovarian function reduces75. Its influence on menopausal symptoms, such as hot flashes, urogenital atrophy, and changes in bone density, underscores its significance. In vitro studies have identified the genes OecA, OecB, and OecC that play a pivotal role in the degradation of estrogen within the bacterium Sphingomonas sp. KC8. OecA encodes 3β, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, initiating estrogen breakdown. OecB, which encodes estrone-4-hydroxylase, facilitates the conversion of estrone into an intermediate compound. OecC, responsible for 4-hydroxyestrone 4,5-dioxygenase, further processes these intermediate compounds116. It should be noted that the Sphingomonas strain KC8 was the first genome report of estrogen-degrading bacteria117. However, Sphingomonas is not found to be a resident bacterium in the human microbiome, but rather an opportunistic nosocomial infection.

The discovery of the ability of endogenous steroids to directly trigger alterations in the normal microbiota offers novel insights into the link to oral and general health marked by fluctuations in steroid levels118. Steroid dehydrogenases have been identified in several bacterial genera including Clostridium, Corynebacterium, Bacillus, Mycobacterium, Nocardia, Pseudomonas, and Streptomyces119. It highlights that the inhabitants of oral microbial cells can metabolize progesterone and testosterone through microbial enzymes. Streptococcus mutans possesses both 5α- and 5β-steroid reductases, alongside 3α-, 17β-, and 20α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases, facilitating the metabolism of progesterone and testosterone120. In addition, other oral bacteria found in the gingival sulcus are known to harbor bacterial enzymes involved in steroid conversion. For example, Treponema denticola metabolizes cholesterol, progesterone, and testosterone through 5α-reductase, 3β-, and 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase112. Thus, focusing on the microbial role in hormonal metabolism during the menopausal transition underscores the potential for targeted interventions and sheds light on previously unexplored avenues for the management of menopausal symptoms.

A significant limitation of current menopausal microbiome research is the overrepresentation of Western populations leading to a lack of diversity in the studied groups121,122,123. This bias may limit the generalizability of findings, as the microbiome is known to be influenced by lifestyle, diet, and geographic factors that can vary significantly between populations124. Studies have shown that the gut microbiome, in particular, is shaped by factors such as diet and environment, which can differ drastically between Western and non-Western populations. For example, women in African or Eastern regions may have distinct microbial profiles due to differences in their diets and exposures to environmental factors125. Addressing this gap is crucial. Research that includes more diverse populations, such as those from Africa, Asia, and Latin America, could offer a more comprehensive understanding of how menopause affects the microbiome globally. A more geographically inclusive approach would help reveal variations in microbial communities, allowing for the development of more personalized interventions that are better suited to the needs of diverse groups of menopausal women.

Conclusion

Menopause marks a significant point in the aging process of women, characterized by hormonal shifts and the cessation of menstrual cycles, impacting their health and well-being. Perimenopause represents a prolonged metabolic transition that concerns the interaction between hormones and the microbiome. This phase of a woman’s life, which spans premenopausal hormone levels through the menopausal transition, significantly impacts the composition and dynamics of the microbiome. The gradual decline in hormone levels during perimenopause disrupts the balance of the microbiome, leading to a variety of anatomical conditions and health complications. The microbiome undergoes significant changes impacting various body sites including the oral, intestinal, and urogenital niches. Hormonal fluctuations play a crucial role in shaping these microbial communities, with implications for disease susceptibility. Estrogen influences microbial communities while microbes can metabolize and influence estrogen levels. Thus, the interaction between hormones and the microbiome is complex and bidirectional. Understanding the menopausal shift encompasses how hormonal changes, environmental factors, and microbial dynamics affect menopausal symptoms and women’s health. This insight could drive the development of precise therapies to alleviate symptoms and minimize the risk of related health issues, ultimately enhancing the quality of life for menopausal women.

Responses