Meta-correlation of the effect of ketamine and psilocybin induced subjective effects on therapeutic outcome

Introduction

Psychiatric conditions affect millions of people globally. Mainstream antidepressants remain the standard of care and first-line treatment despite limited and delayed efficacy. Consequently, there is a pressing need for alternative pharmaceutical options. Recently, various psychedelics demonstrated efficacy in treating several psychiatric illnesses.1 Psychedelics are a class of psychoactive substances that modulate consciousness, internal and external perception, mood, and various cognitive functions1. They include a variety of pharmacological classes with different modes of action. “Classical psychedelics” act as agonists at serotonin receptors (psilocybin and lysergic acid diethylamide). “Non-classical psychedelics” include those that act on different targets, such as non-serotonergic opioidergic or adrenergic pathways. The non-classical psychedelics include those that antagonize the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor and include substances such as ketamine, esketamine and nitrous oxide, while others act at dopamine (MDMA) or opioid receptors in addition to serotonergic activity (ibogaine)1,2,3. What these drugs have in common is that they induce psychoplastogenic effects, i.e., they cause neurotrophic changes in the brain and promote rapid neural plasticity with rewiring of pathological neurocircuitry2. Still, despite these shared pathways, each of these psychedelics exert unique effects on subjective conscious experience that differ markedly in nature among compounds4. These subjective effects are perceived as meaningful and significant by some users and have been implicates as potential mechanism of therapeutic effect.5

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the use of psychedelics in clinical practice, particularly within psychiatry and pain medicine, for treating various conditions such as therapy-resistant depression, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance use disorder (SUD) and chronic pain6. A significant milestone in this respect was the 2019 approval of intranasal esketamine by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of depression7,8. Regarding treatment of therapy-resistant depression, substantial evidence now indicates that a single or just a few doses of ketamine may lead to a rapid onset of therapeutic effects, unlike conventional antidepressants9,10. Similar findings have been reported for psilocybin, a psychedelic that is also being tested in depression and chronic pain11,12. Ketamine is classified as a dissociative drug with, as recently reiterated by Ballard and Zarate, dissociation defined as the “discontinuity in the normal integration of consciousness, memory, identity, emotion, perception, body representation and behavior”13. The classical psychedelic psilocybin causes subjective effects that encompass mystical experiences and changes in affect, cognition and perception14,15. At low-dose, we observed commonalities in subjective experience across various psychedelic drugs, including a disconnect from reality with signs of altered perception of inner and outer worlds, sometimes accompanied by insights or understanding that could be described as mystical experiences16.

Some studies suggest that the perceived subjective effects of ketamine and psilocybin are crucial for their therapeutic effects, although no mechanistic insight is given in any of these studies,5,14,15 but this hypothesis has recently been discussed and dismissed by Ballard and Zarate13. This is in part based on the inconsistent findings in correlation among the different published studies due to (i) the difference in temporal dynamics between subjective effects and therapeutic outcome, (ii) the use of insensitive tools to measure subjective effects and (iii) apparent absence of dose-response relationships (i.e., higher doses may cause more subjective symptoms but may not cause greater antidepressant effects)13. Still, these authors acknowledge that further work is warranted to explore and better understand this relationship.

We conducted a literature search for published studies on ketamine (racemic and esketamine) and the serotonergic psychedelic (SP) psilocybin that report on the correlation of subjective effects versus therapeutic improvement in depression and SUD. In this initial meta-correlation and systematic review, we focused on ketamine and psilocybin, and refrained from adding other psychedelics. After retrieval of relevant studies that gave quantitative data on the correlation, we next conducted random-model meta-correlation analyses with separate analyses for ketamine and psilocybin. While several narrative reviews are available (see for example refs. 1, 5, 10, 13 and 14), to the best of our knowledge this is the first meta-correlation analysis on the topic. Our main research question was to determine the magnitude of the correlation between ketamine and psilocybin-induced subjective effects and therapeutic improvements and determine whether the two treatments, ketamine and psilocybin, quantitatively differ in magnitude of correlation.

Results

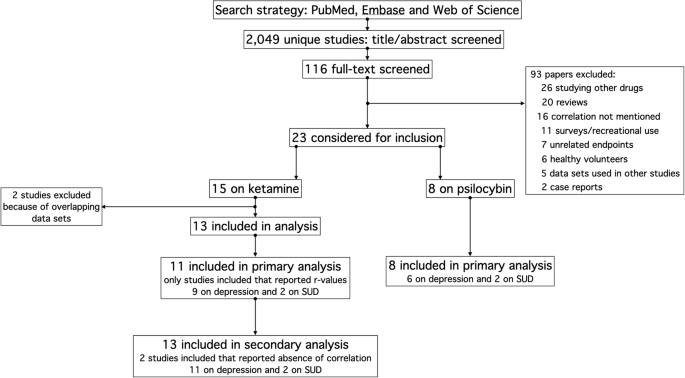

The search strategy resulted in 2049 unique papers (date range: 1959 to 2024) that were screened based on their title. EMABASE and Web of Science did not yield any papers that were not retrieved from PubMed. After removal of duplicates and non-relevant papers, 116 papers were read in full of which we discarded 93 papers because of meeting the exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Of the remaining 23 papers (date range: 2000 to 2024), 15 were on the treatment of ketamine for depression (n = 13)17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 or SUD (n = 2)32,33, and 8 on psilocybin for treatment of depression (n = 6)33,34,35,36,37,38,39 or SUD (n = 2)40,41. Of the 15 ketamine papers, 2 reported that the correlation between subjective effects and treatment efficacy was absent20,27. These studies were not included in the primary analysis, but were used in a sub-analysis, with correlation coefficients set to zero imputated in the meta-analytical data set. Three studies, all on ketamine, included multiple overlapping data sets21,30,31. We included one of these three studies. (Pennybaker et al.21). This resulted in a final data set used in the primary analysis of 11 ketamine studies, 9 on depression and 2 on SUD17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29, and 8 psilocybin studies as mentioned above32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. Two papers included in our analysis reanalyzed multiple data sets; the individual studies are given in the legend of Table 140,41,42,43,44,45,46.

Flow chart of the study search and selection process.

An overview of the all 23 studies included in our primary or secondary analyses with evaluations of risk of bias is given in Table 1. There were 12 RCTs (10 for ketamine, 2 for psilocybin) with either an inactive placebo, active placebo (e.g., niacin) or a waiting-list control. These studies were assumed to have a low risk of bias, not considering an expectation bias that evolved following administration of the intervention due to the occurrence of subjective effects. The other studies were either open-label trials or studies that were a re-analysis of earlier published data sets. Of the latter set of studies most were double-blind randomized trials40,41,42,44,45,46, while one was an open label study43. The open-label studies and retrospective analyses were considered to have a high risk of bias (i.e., high risk of unblinding). When considering the expectation bias, all studies had a moderate or high risk of bias.

Ketamine

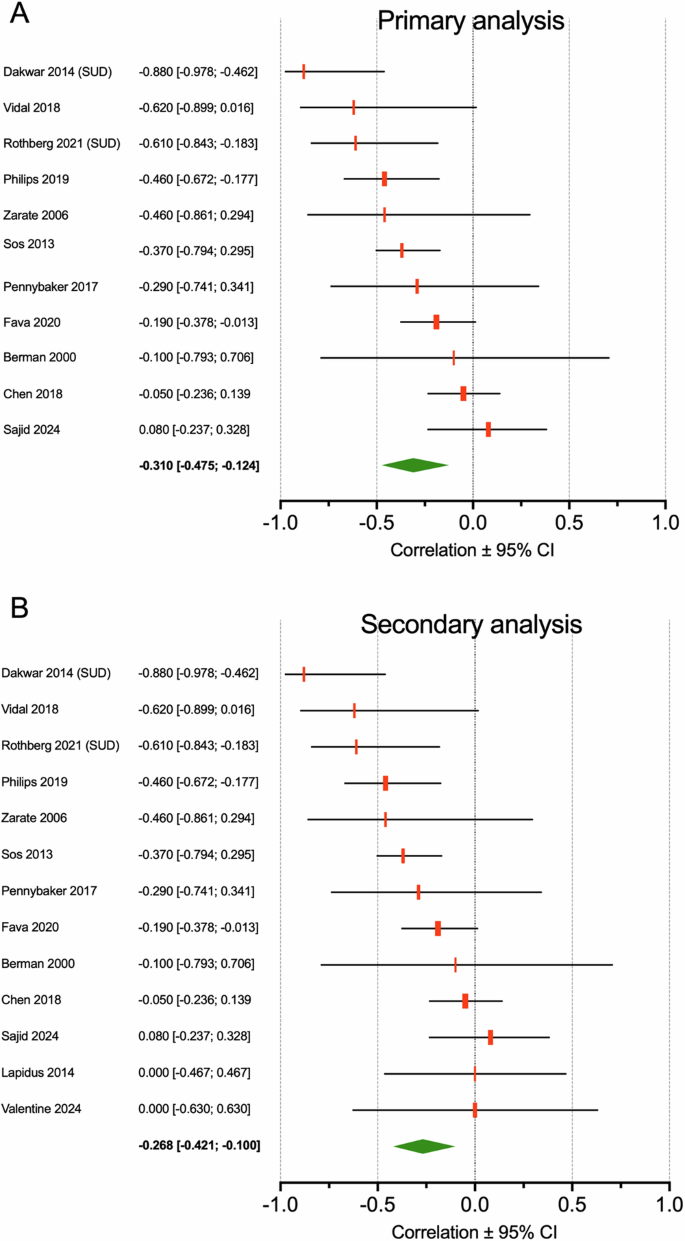

Eleven studies reported on the correlation between subjective effects and treatment efficacy with a total number of treated patients of 443. The pooled effects size ± standard error was –0.310 with a 95% confidence interval of –0.475 to –0.124, (p = 0.001). Across all studies heterogeneity (I2) was 55% (see Fig. 2A for forest plot). The leave-one-out method did not reveal that one study dominated the outcome. Subgroup analysis on just the intravenous ketamine administration (n = 10) yielded a pooled effect size of –0.355 (–0.548 to –0.126, p = 0.003, I2 = 99%). Two studies reported on the effect of intranasal ketamine or esketamine with a pooled effect size of –0.164 (–0.341 to 0.025, p = 0.089, I2 = 0). Nine papers studied ketamine effect in depression with a pooled effect size of –0.201 (–0.344 to –0.050, p = 0.009, I2 = 29%). Two studies were conducted in patients with either alcohol or cocaine use disorder with a pooled effect size of –0.738 (–0.917 to –0.310, p = 0.003, I2 = 39%). RCTs (n = 8) yielded a pooled effect size of –0.357 (−0.556 to −0.118, p = 0.004, I2 = 57%), while open-label studies or studies that included multiple earlier published data sets (n = 3) yielded a pooled effect size of –0.221 (–0.527 to 0.136, p = 0.223, I2 = 40%). Finally, we added the two studies of which the authors reported that no correlation was present and imputated a correlation coefficient of zero in the data set; in these two analyses, there were a total of 28 patients. This yielded an overall effect size of –0.268 (–0.421 to –0.100, p = 0.002, I2 = 48%, n = 13 studies with 471 treated patients; Fig. 2B).

The green diamond depicts the groups size ± 95% confidence interval for all studies that gave correlation coefficients. The gray diamond depicts the total group size ± 95% confidence interval of pooled analysis. A Primary analysis. B Secondary analysis that included 2 studies (Lapidus et al.20 and Valentine et al.27) for which we imputated a zero value for the correlation coefficient.

Psilocybin

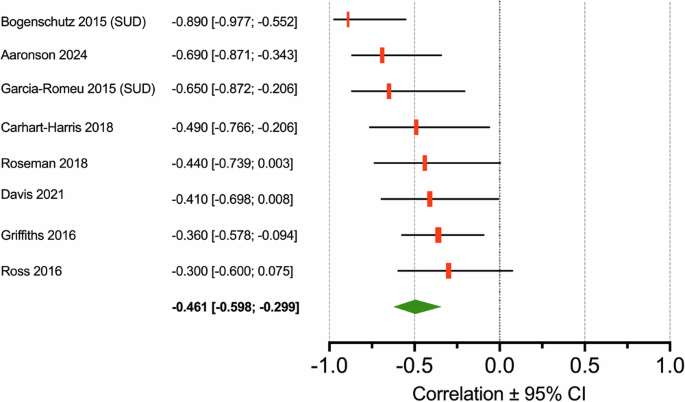

Eight studies were retrieved and included in the meta-correlation analysis with a total of 183 patients treated for depression or SUD. The overall effect size was –0.495 with 95% confidence interval –0.624 to –0.341, p = 0.000, I2 = 28% (Fig. 3). The leave-one-out method did not reveal that one study dominated the outcome. Restricting the analysis to treatment for depression (n = 6) yielded a pooled effect size of –0.426 (–0.550 to –0.284, p = 0.000, I2 = 0) or for SUD (n = 2) of –0.776 (–0.930 to −0.391, p = 0.001, I2 = 40%). RCTs (n = 3) had a pooled effect size –0.355 (–0.517 to –0.169, p = 0.000, I2 = 0), while open-label studies had a pooled effect size of –0.620 (–0.757 to –0.430, p = 0.000, I2 = 17%).

The green diamond depicts the groups size ± 95% confidence interval.

Subgroup analyses

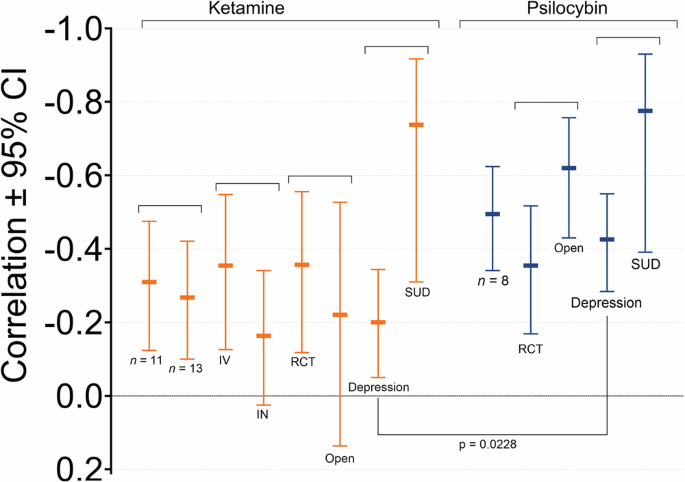

Figure 4 depicts the results of the subgroup analyses. While there is a large overlap in 95% confidence intervals among subgroups for both treatments, the correlation coefficients in individuals with a SUD were larger than those of individuals treated for depression, irrespective of treatment: ketamine in depression correlation coefficient = −0.201 versus SUD −0.738 (ratio = 3.7); psilocybin in depression correlation coefficient = −0.425 versus SUD −0.776 (ratio = 1.8). No statistical comparison between subgroups within treatments was performed due to the small sample sizes.

Ketamine n = 13: meta-analyses including two studies for which we imputated a zero correlation coefficient values; IV studies on intravenous ketamine (n = 9); IN studies on intranasal ketamine (n = 2); RCT randomized controlled trials (n = 8); Open: open-label trials and studies that combined data from multiple studies; Depression: studies on depression treatment (n = 9); SUD: studies on the treatment of substance use disorder (n = 2). Psilocibin n = 8: all included psilocybin studies; RCT randomized controlled trials (n = 6); Open: open-label trials (n = 2); Depression: studies on depression treatment (n = 6); SUD studies on the treatment of substance use disorder (n = 2).

Ketamine versus psilocybin

A significant difference in correlation coefficients between the two treatments groups was not observed for the complete data set (depression versus SUD, n = 19) when excluding the imputated studies: ketamine studies (n = 11) effect size = –0.310 (–0.475 to –0.124) versus psilocybin studies (n = 8) effect size –0.495 (–0.624 to –0.341), p = 0.108. However, including those two studies revealed a significant difference between ketamine and psilocybin: ketamine studies (n = 13) effect size = –0.268 (–0.421 to –0.100) versus psilocybin studies (n = 8) effect size = –0.495 (–0.624 to –0.341), p = 0.040). Furthermore, comparing studies on depression treatments alone, without imputation, showed a significant difference between treatments: ketamine studies (n = 9) effect size = –0.201 (–0.344 to –0.050) versus psilocybin studies (n = 6) effects size = –0.426 (–0.550 to –0.284), p = 0.0228). See Fig. 4.

Substance use disorder

Finally, to get an indication of the effect of subjective effects on treatment efficacy in individuals with a SUD, we pooled the 4 studies (2 ketamine and 2 psilocybin trials with in total 54 patients). The pooled effect size was –0.740 with 95% confidence interval –0.862 to –0.539 and I2 = 12% (p = 0.000).

Discussion

While many psychedelics share central pathways through which they exert their psychoactive and therapeutic effects, much remains unclear about their mechanism of action, particularly the association between subjective and therapeutic effects. We conducted meta-analyses to evaluate the relationship between subjective effects and therapeutic effectiveness induced by ketamine and psilocybin. Our analyses showed that a correlation between subjective symptoms and therapeutic benefit was present for both ketamine and psilocybin in the treatment of depression and SUD. The magnitude of the pooled correlation coefficients was moderate in magnitude for both drugs albeit the correlation was greater for psilocybin than ketamine, particularly in the treatment of depression. Pooled correlations coefficients were –0.310 for ketamine and –0.495 for psilocybin. Converting these values to the coefficient of determination (R2) suggests that subjective effects mediate a modest 10% of the ketamine’s therapeutic effect (5% when including the two studies with imputated zero values for r) and 24% of the psilocybin’s therapeutic effects47,48. There was considerable variability among studies, with in some studies R2-values exceeding 50%, while others found no correlation between subjective effect and therapeutic outcome. In our analyses, we aggregated treatments for depression and SUD. Disentangling these yielded R2-values of 4% (ketamine, excluding imputation), and 18% (psilocybin) for depression treatment, excluding the studies with imputated zero values for r, while much higher values were observed for SUD treatment: 54% (ketamine) and 60% (psilocybin). It is important to note the SUD data were retrieved from just 4 studies, two for each treatment.

Given the heterogeneity among studies and the limited number of studies included in our analysis, we approach our conclusions with caution. Nonetheless, our exploratory study suggests a modest role for subjective effects in mediating therapeutic outcomes, with a greater effect for psilocybin compared to ketamine, particularly when restricting the analysis to depression. Our data further suggest that the mediation of treatment outcome by subjective effects is more pronounced for SUD treatment compared to depression treatment. To fully interpret our results, a detailed discussion of the individual components of our analyses is warranted.

The nature of the subjective effects of different psychedelic drugs vary significantly3. It is our experience that low-dose ketamine effects are well described by dissociation from self and environmental reality, coupled to an intense drug high (spaced out)49,50. These subjective effects are well tolerated and sometimes even sought for when consuming ketamine for pleasure. Typically, dissociation resolves upon termination of ketamine infusion49. Most ketamine studies in our analysis used the Clinician-Administered Dissociative State Scale (CADSS) or the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (Table 1)51,52. The CADSS, first developed for assessing trauma-specific dissociative symptoms in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder, is increasingly used as an instrument to evaluate state dissociation in clinical practice51. Conversely, the BPRS is designed to rapidly assess symptom changes in schizophrenia patients52. We argue that since these tests were not developed for studying ketamine or psilocybin related subjective changes neither test may adequately captures the subtle ketamine-induced changes in consciousness, internal and external perception, mood, or various cognitive functions. In our research with healthy volunteers, we use the Bowdle Visual Analog Scale to quantify ketamine’s subjective effects, which is a 13-question questionnaire, developed to measure the overall psychedelic effects from ketamine, rather than its dissociative effects specifically in healthy volunteers53,54. The use of questionnaires that not fully capture the complete scope of subjective or dissociative ketamine effects (i.e., changes in internal and external perception) may explain the low correlation observed in our analysis. Whether the Bowdle questionnaire adequately captures subject effects in clinical studies and yields more robust correlations than other questionnaires requires further study.

The subjective effects during treatment with psilocybin are clearly distinct from those induced by ketamine. A study in healthy volunteers using language pre-processing described the psilocybin experience with terms like “connection with the universe”, “familial love” and “experience of profound beauty”, indicative of a mystical experience15. Tools such as the Mystical Experience Questionnaire or those measuring oceanic boundlessness55,56, which refers to the spiritual experience during a treatment session, may be more appropriate for capturing the mental state induced by psilocybin than the CADSS and BPRS are for ketamine. This may to some extent explain the stronger correlation observed between subjective effects and therapeutic effects for psilocybin.

For interventions that produce subjective effects such as psychedelic medication, there is a likelihood for unblinding and the possibility of expectation bias. Theoretically, such bias may affect the therapeutic outcome and may occur particularly in open-label studies. We observed that a higher correlation coefficient was observed for open-label psilocybin studies with an R2 of 39%, while a smaller correlation was observed in RCTs (R2 = 13%), whereas the reverse was true for ketamine (RCTs 13%, open-label 5%). The nature of subjective experiences is so specific and distinct from placebo or active comparators that functional blinding is effectively impossible, also in RCTs. However, we do not expect that treatment-naïve patients appreciate such differences in full, but investigators might. We argue that patient unblinding per se does not explain the differences observed in open-label studies and RCTs, and agree with Ballard and Zarate13, that the relationship between subjective symptoms and therapeutic outcome is not a byproduct of unblinding.

Alternative study approaches may be useful for examining the relationship between subjective effects and therapeutic outcomes, possibly with reduced expectation bias. Lii et al.57 studied the effect of ketamine administered during unconsciousness from general anesthesia in patients with a major depressive disorder. In this fully blinded RCT, the antidepressant effect of ketamine and placebo were similar, suggestive that masked treatment allocation reduces ketamine effectiveness. Another approach is to reduce the magnitude of subjective effects and assess the subsequent impact on therapeutic outcome. In a fully-blinded RCT, we investigated the effect of the nitric oxide donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP) on racemic ketamine- and esketamine-induced pain relief in healthy volunteers49,50,58. The study was prompted by several rodent studies showing that nitric oxide can reduce psychotic symptoms from racemic ketamine59,60. We observed that using mathematical modeling, the pain relief and subjective effects, induced by esketamine, were highly correlated with respect to potency and dynamics50, and additionally that SNP reduced racemic ketamine-induced subjective effects by 20 to 40% and simultaneously pain relief by the same amount48,58; subjective effects were quantified using the Bowdle questionnaire. These two blinded studies with a reduced likelihood for unblinding showed that modifying ketamine-induced symptoms may affect outcome (i.e., less perception of subjective effects is associated with lesser therapeutic effect). However, both studies did not replicate the clinical setting, and experimental conditions such as choice of participants and/or specific experimental protocols may have influenced study outcomes. For example, during anesthesia, the antidepressant effects of general anesthetics may have influenced outcome61. Moreover, we cannot exclude that the observed therapeutic and subjective drug effects are scaled in a correlated fashion, but are effects without any causal influence.

A greater correlation observed for psilocybin than ketamine was noted for studies on depression treatment. This may possibly be related to differences in the nature of the subjective effects or the observation that psilocybin’s subjective effects persists for longer episodes beyond the treatment session (hours and possibly days)32,35,37,38. For ketamine, the subjective effects are short-lived, commonly no longer than 30 to 60 min after ending the ketamine infusion49. Interestingly, for treatment of SUD the correlations for both treatments were similarly higher compared to depression treatment. The reason for a difference between SUD and depression remains unknown but may relate to the small number of studies, the noise in the data or the very different nature of the disorders, with possibly SUD-related neuronal pathways more sensitive to a modulatory role of subjective effects the treatment of SUD.

Finally, some methodological items needs further elucidation. The majority of studies that we included report the Pearson correlation coefficient, a dimensionless measure of covariance. This measure assumes a linear relationship between normally distributed, random and continuous variables47. Any deviation from these assumptions requires either data transformation or the use of the Spearman correlation, which is a correlation on ranks47. For example, it may well be that subjective effects are related in a non-linear fashion with therapeutic outcome. We pooled the studies to enhance our data set, but we are aware that different measures to quantify correlation may have affected outcome. In future studies, we suggest to use Spearman’s correlation coefficient.

We tested in our analysis whether subjective effects mediate therapeutic outcome. Still the very different nature of symptoms observed after ketamine and psilocybin and differences in correlation, may suggest that, if a causal relationship exists, this may be exclusively dependent on specific types of subjective effects (e.g., oceanic boundlessness as part of the Altered State of Consciousness questionnaire, Table 1)56. We did not capture this in our analysis and collated all symptoms.

While the majority of the studies included psychotherapy in the treatment of depression or SUD while studying the effect of ketamine or psilocybin, others did not. This may have impacted outcome. Future studies should address the combination of psychedelic therapy without and with psychotherapy on the influence of subjective effects on outcome.

Lastly, our results cannot affirmatively determine causality and given the modest and highly variable correlations, we cannot exclude that psychoactive effects are epiphenomena that arise from activated brain networks with similar pharmacodynamic properties as the therapeutic effects.

Methods

Search strategy

The protocol was registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, PROSPERO, under identifier CRD42024546815 (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/) on May 25, 2024. We systematically searched the electronic literature databases PubMed, EMABASE and Web of Science to identify clinical studies on racemic ketamine, esketamine or psilocybin treatment of depression or SUD. No restrictions were made with respect to publication dates or language. The search strategy was developed in collaboration with information specialists of the Walaeus library of the Leiden University Medical Center. For our PubMed search strategy, see the PROSPERO registration.

The search was performed on May 26, 2024 and June 30, 2024 to search for more recently published papers. After removal of duplicates, studies were selected based on the title/abstract level and thereafter at the full-text level. We also searched relevant articles such as review articles for additional references. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) human studies; (2) available full-text articles; (3) reporting on the effect of treatment on the underlying disease, depression or SUD; (4) reporting on subjective effects from treatment with ketamine or psilocybin; (5) giving the quantitative value of correlation between #3 and #4; (6) randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or open-label studies. Exclusion criteria included case reports, online surveys, review papers, animal studies, diagnoses other than depression or SUD or treatments other than ketamine or psilocybin. In some papers the data from more than one study were collated and the analyses were performed on the combined data sets. Such studies were included, but the original studies were then discarded. Two reviewers independently conducted the selection procedure (JDCD and AD); differences in opinion were resolved by consensus or consultation with the other authors.

Study evaluations

Non-randomized trials were evaluated with the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale62, randomized trials with the revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool63. The focus of the assessments was on performance of independent blind assessment, to determine the risk of unblinding. Risk assessment was performed by two authors (JDCD and AD) and differences in opinion was by consensus or consultation with the other authors.

Data extraction and meta-analysis

We retrieved the Pearson correlation coefficient or Spearman correlation coefficient (both represented here by the letter r) from the results section or figures of the relevant papers and imputated these values together with the number of subjects exposed to active therapy into the meta-analysis program Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software package version 3.0 for Windows (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ). When more than one correlation coefficient was given, e.g. multiple values over time, we used a single value retrieved from the time point closest to treatment. When multiple endpoints were measured for treatment efficacy (such as different questionnaires or measures of antidepressant efficacy), we used the correlation coefficient that was retrieved for the primary endpoint. For each study, the correlation coefficient and 95% confidence intervals were calculated and presented in a forest plot. We analyzed the data with random effects models assuming 2 sources of variance: within-study and between-study error. We present the pooled effect-size per drug separately (ketamine and psilocybin). Direct comparison between ketamine and psilocybin was done by mixed-effects analysis. Additional analyses were performed to determine the effect of single studies (sensitivity analysis using the leave-one-out method) and heterogeneity (visual inspection of the forest plot and the between study inconsistency in the results, I2). Next, we conducted subgroup analyses per disease state (depression, SUD), and trial type (RCT, Open-label/reanalysis of multiple studies that were earlier published) to get an indication of overt differences between disease and study type, and for ketamine, to determine differences between administration forms (intravenous, intranasal). In two studies, it was obvious that no correlation was present but the exact correlation coefficient was not given. After consultation among authors, a separate analysis was performed in which these studies were included in the overall analysis with correlation coefficient of zero imputated in the meta-correlation analysis. All within treatment sub-analyses were purely exploratory given the small number of studies, and possibility of differences in variances between subgroups. The meta-analysis was performed according to published guidelines (PRISMA 2009) and algorithms64,65.

Responses