Metal–phenolic coating on membrane for ultrafast antibiotics adsorptive removal from water

Introduction

Antibiotics, prevalent in pharmaceutical compounds, have garnered widespread global attention for their efficacy in combatting microbial infectious diseases across humans, animals, aquaculture, and livestock domains1,2. Ciprofloxacin (CIP), as a typical fluoroquinolone antibiotic, has been widely used in the treatment of bacterial infections because of its potent bactericidal properties3. While their discovery has undeniably revolutionized human health and productivity4, their intricate molecular structures, robustness, slow degradation kinetics, and bioactive metabolites contribute to considerable water pollution upon release into aquatic ecosystems, posing profound risks to both environmental integrity and public health5,6. Prolonged exposure to CIP in natural environments engenders the proliferation of antibiotic-resistance genes (ARGs) and antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB), escalating the global threat of CIP resistance and undermining the resilience of ecosystems and human well-being7,8. Moreover, the production and application of CIP yield copious volumes of wastewater rich in antibiotic residues, exacerbating aquatic pollution and exacerbating environmental degradation9,10. Thus, the exigency to efficaciously remove CIP from contaminated waters, with swift removal kinetics and economic viability, is paramount.

Some representative technologies, such as advanced oxidation, ion exchange, adsorption, coagulation, and membrane separation, have been widely exploited to treat antibiotic-contaminated water11,12. Notably, membrane separation technology presents a compelling solution, offering exceptional separation selectivity, minimal energy consumption, reduced reliance on additional chemicals, scalability, and the potential for continuous operation13. However, the wide pore size distribution faded the commercial polymeric membrane for antibiotic removal, as most of the membrane separation performance is frequently determined by the physio-chemical characteristics of the system and the size exclusion parameter14. Hence, many pioneering manufacturing protocols, utilizing filling and reducing the membrane’s pore, have been developed to enhance the ability to remove antibiotics15. There remains an open state to produce advanced membranes characterized by elevated selectivity, permeance, renewability, economic feasibility, and environmental sustainability for wastewater treatment.

Adsorptive membranes, which integrate adsorption and filtration processes, have gained much attention for antibiotic removal due to their design versatility and ease of fabrication16. A suitable adsorbent loading or bounding onto the membrane could selectively capture contaminants while allowing the solvent to permeate, simultaneously satisfying the selectivity and permeance of membrane separation requirement17. Many emerging nanomaterials, such as activated carbon, layered double hydroxide, graphene oxide, metal-organic frameworks, and metal oxides, were selected as adsorbents to enhance membrane modification for the removal of antibiotics in aquatic environments18,19,20. Nevertheless, numerous preparation steps, elevated costs, regeneration requirements, and high operating pressures further constrain the applicability of adsorptive membranes for the removal of antibiotics21. Therefore, researchers endeavor to identify the optimal adsorbent to improve the commercial membrane and maximize the separation and permeance efficiency of the adsorptive membrane.

The harnessing of biomass for fabricating value-added functional materials in sustainable environmental contexts has emerged as a focal area of inquiry, heralding a paradigm shift away from petrochemical-derived precursors and hazardous substances22,23. Polyphenols, ubiquitous in diverse plant biomass, historically employed as natural dyes and tanning agents, serve as promising foundational elements for the construction of metal–phenolic coating, self-assembled supramolecular architectures synthesized through the in-situ polymerization of polyphenol building blocks and metal ions via reversible coordination bonds, showcasing immense potential across energy and environmental domains24,25,26. Notably, metal–phenolic coating has been effectively deployed to modify conventional microporous membranes, facilitating ultrafast antibiotic removal in flow-through purification systems and demonstrating remarkable adsorptive efficiency towards cationic organic contaminants within wastewater treatment plant effluents27,28. Leveraging the innate adhesive properties of polyphenol building blocks onto diverse substrates facilitates the precise deposition, heralding a transformative shift towards practical, real-world applications29. As polyphenols have exhibited utility in cleansing contaminated wastewater, the systematic exploration of metal–phenolic coating onto commercial membranes for antibiotic removal represents a pivotal stride toward tangible application in real-world scenarios30.

In this study, we embarked on developing a metal–phenolic coating on a commercial membrane (MCM) platform, employing commercially available plant-based tannic acid (TA) to effectuate the efficient removal of antibiotics from simulated wastewater. Our findings underscore the remarkable separation efficacy exhibited in the removal of representative antibiotics, including tetracycline (TET), oxytetracycline dihydrate (OXY), doxycycline hydrochloride (DOX), chlortetracycline hydrochloride (CHL), and ciprofloxacin hydrochloride (CIP). Additionally, we established pivotal metrics such as fabrication simplicity, enhanced cleaning efficacy, and membrane recyclability. This study heralds a novel, eco-centric approach toward developing active membranes for energy-efficient water treatment.

Results and discussion

Preparation and characterization of the MCM membrane

The fabrication procedure of the MCM is delineated in Fig. 1. The selection of nylon as the supporting membrane substrate is based on its robust structural stability under both acidic and alkaline conditions31. Moreover, the nylon membrane (Fig. 1a) possesses a substantial pore size of 0.2 μm, which is conducive to achieving high permeance in the resulting MCM. The nylon membrane was soaked in a tannic acid solution to form the nylon/TA composite (Fig. 1b), which was then immersed in a FeCl3 solution for a predetermined duration to synthesize the MCM (Fig. 1c). Optical imaging reveals that metal–phenolic networks (MPN) formed promptly, bestowing a characteristic black hue upon the MCM, with the degree of blackening varying according to the soaking duration (Supplementary Fig. 1). Notably, a brief soaking time of merely two minutes was sufficient to achieve TA-Fe coating coverage across the nylon substrate, while prolonged soaking durations contributed to enhanced stabilization of the MPN on the MCM. The MCM underwent three successive immersions in deionized water following fabrication to eliminate any residual precursors.

a Pristine nylon membrane. b Nylon-TA membrane. The left downside is a photograph of the prepared Nylon-TA membrane. c MCM membrane. The right downside is a photograph of the prepared MCM membrane.

Figure 2 illustrates the scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of the pristine nylon membrane, the nylon/TA composite, and the MCM membranes. The hydrophilic nature of the nylon substrate inherently facilitates the adsorption of tannic acid molecules, thus promoting the in-situ polymerization of polyphenolic building blocks and metal ions via reversible coordination bonds. Following this process, MCM nanoparticles are dispersed across the nylon substrate, with a proclivity to occupy the membrane pores contingent upon the duration and concentration parameters of the polymerization process. In comparison to the smooth surfaces’ characteristic of the pristine nylon and nylon/TA membranes, the MCM membrane displays a markedly roughened interface, a consequence of the stochastic deposition of MCM nanoparticles (Fig. 2a–c). Water contact angle (WCA) analysis showed that the insertion of TA-Fe into the nylon matrix (Supplementary Fig. 2) greatly improved the hydrophilicity of the MCM-60 (26.92°), due to the formation of stable complexes between tannic acid and Fe3+, thus improving the wettability and roughness of the membrane14. To elucidate the elemental composition of the MCM membrane, SEM-EDS mapping was conducted across all samples. Elemental mapping revealed a homogeneous distribution of carbon, oxygen, and iron throughout the surface of the MCM-60 membrane (Fig. 2d–g). EDS spectra further substantiated the presence of iron, corroborating the successful deposition of TA-Fe nanoparticles on the nylon substrate across varying temporal scales (Fig. 2h). Additionally, atomic force microscopy (AFM) imaging (Fig. 2i) demonstrated a uniform assembly of metal-phenolic networks (MPN) on the nylon membrane, with a dense pore structure that aligns with SEM observations. Furthermore, SEM revealed that TA-Fe on the nylon membrane exhibited a rough surface, attributed to the presence of distinct TA/Fe composite particles (Fig. 2c), which corresponded with the high roughness observed in the AFM image (Fig. 2i). These findings underscore the successful fabrication of a TA-Fe nanoparticle coating on the commercial nylon membrane, establishing a stable and efficacious active site for removing pollutants.

a SEM image of pristine nylon. b SEM image of nylon-TA. c SEM image of TA-Fe on nylon membrane. d SEM-EDS mapping of MCM-60 and its elemental mapping of (e) carbon, (f) oxygen, and (g) iron. (h) The iron content for each sample. i AFM image of the MCM-60.

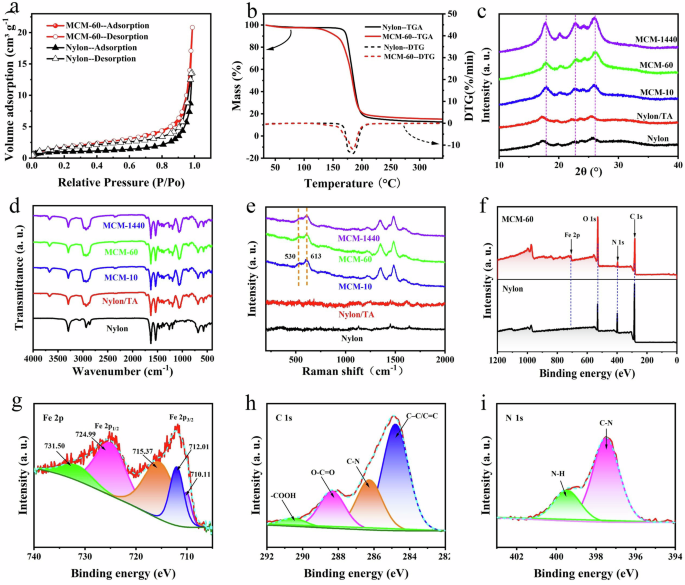

The fundamental structural characteristics of the TA-Fe nanoparticles coating on the membrane were systematically examined to evaluate their potential for enhanced adsorption and removal of antibiotics. The specific surface area, as determined by the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method (Fig. 3a), was found to be 7.0 m2 g−1 for the MCM-60, exceeding that of the pristine nylon membrane (3.7 m2 g−1). This increased surface area indicates a greater density of active sites resulting from the loading of TA-Fe nanoparticles, which facilitates enhanced interaction and adsorption of contaminants onto the MCM membranes32. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential thermogravimetry (DTG) were employed to assess the thermal stability of the TA-Fe nanoparticles on the MCM membrane (Fig. 3b). The MCM-60 sample exhibited increased thermal sensitivity below 200 °C compared to the pure nylon membrane, attributable to the hydrophilic nature of the TA-Fe nanoparticles, which preferentially adsorb water vapor33. Above 200 °C, MCM exhibits less weight loss due to the formation of tannic acid and iron complexes, giving MCM greater thermal stability14. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (Fig. 3c) confirmed the formation of an amorphous phase of TA-Fe nanoparticles, indicative of a self-assembly process facilitated by kinetic trapping34. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Fig. 3d) identified an absorption peak at 1710 cm−1, corresponding to C = O stretching, suggesting TA molecules’ presence on the modified membranes. Bands observed at 1618 cm−1 and 1403 cm−1 were attributed to C = C stretching vibrations of the aromatic ring, while the band at 1072 cm⁻¹ indicated phenolic C–O stretching vibrations in the C–OH aliphatic hydroxyl groups35,36,37. The appearance of these new spectral features confirms the successful adsorption of TA onto the nylon substrate, thereby validating the effective formation of metal-phenolic networks (MPN) on the membrane. Raman spectroscopy (Fig. 3e) further elucidated the MCM membrane’s structure, revealing Fe−O vibrations within the 650−400 cm−1 range38. Additionally, bands at 1570 cm−1 (asymmetric, νas) and 1428 cm−1 (symmetric, νs) were indicative of carboxylate (−COO)/Fe interactions39. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (Fig. 3f–i) provided insight into the surface chemical composition of the MCM membrane, showing Fe 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 signals at 712 and 725 eV, respectively, which confirm the predominance of Fe3+ in the MPN membrane (Fig. 3g)14. This result was consistent with EDS images (Fig. 2d–g), which confirmed the presence of elemental iron due to the facial soaking process. Collectively, these chemical analyses substantiate the successful deposition of TA-Fe nanoparticles onto the nylon membrane, thereby establishing it as an effective adsorptive medium for the removal of antibiotics.

a–f Nitrogen sorption isotherms (a), TGA analysis and DTG curve (c), XRD patterns (b), ATR-FTIR spectra (d), Raman spectra (e), and XPS survey scan (f) of nylon and MCM membrane. g–i High-resolution XPS spectra of MCM membrane: Fe 2p (g), C 1 s (h), N 1 s (i).

Adsorption performance of MCM membrane

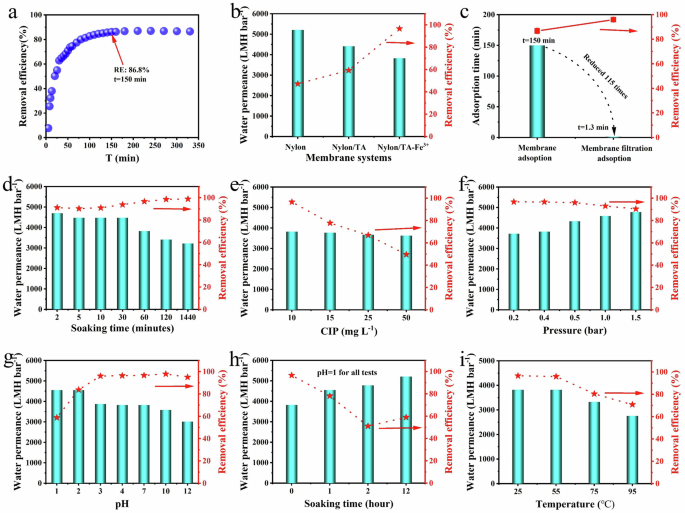

The MCM-60 membrane was initially immersed in 40 mL of ciprofloxacin hydrochloride (CIP, 10 mg L−¹) to assess its adsorption capacity over time. Experiments were conducted at 10-min intervals up to 350 min to ensure equilibrium was reached (Fig. 4a). The maximum removal efficiency of 86.8% was achieved after 150 min of immersion, following which the efficiency plateaued. This phenomenon can be ascribed to the saturation of active sites and the establishment of equilibrium, wherein adsorption and desorption equilibrate as the concentration gradient diminishes34. Therefore, the MCM membrane demonstrated consistent removal performance for CIP over extended contact times.

a CIP removal of MCM-60 in suspension system. [CIP] = 10 mg L−1. b Separation of CIP molecules with commercial nylon membrane, tannins-modified nylon membrane, and MCM-60 membrane. c Comparative analysis of adsorption time among the MCM-60 membrane adsorption and membrane filtration. d Separation of CIP molecules with the MCM-60 membranes versus the soaking time in FeCl3 solutions ranged from 2 to 1440 min. e Separation of CIP molecules with the MCM-60 membranes versus the concentration of CIP solutions ranging from 10 to 50 mg L−1. f Pressure-dependent flux and removal of CIP molecules of MCM-60 membrane under different pressures ranging from 0.2 to 1.5 bar. The five-pointed star curve denotes the removal rate of CIP during the pressure-loading process. [CIP] = 10 mg L−1. g Water permeance and CIP removal efficiency of MCM-60 membrane at different pH values. h Water permeance and CIP removal efficiency of MCM-60 membrane immersed in an acidic solution with different times. i Water permeance and CIP removal efficiency of MCM-60 membrane at different temperatures.

The membrane absorption and separation removal performance of MCM-60 for antibiotic removal from simulated wastewater was evaluated through a dead-end filtration experiment (Supplementary Fig. 3). The feed solution volume was maintained at 100 mL, with 40 mL collected as permeate to minimize concentration polarization effects on the MCM-60 surface. Prior to the detailed assessment, the impact of various MCM preparation parameters—including treatment agents applied to the commercial nylon membrane substrate, soaking duration, and operating pressure—on membrane performance was examined using a CIP solution (10 mg L−¹) as the feed. The pristine nylon membrane demonstrated insufficient CIP removal, obtaining a clearance rate of less than 50% (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 5). Immersion in a tannic acid solution (4 g L−1) for 2 h increased the removal rate to approximately 60%; however, this remained inadequate for effective CIP removal. In contrast, modification of the nylon membrane with FeCl3 solution (1.0 g L−1) following tannic acid treatment yielded the MCM-60 membrane, which demonstrated a remarkable CIP removal rate of 96.7% and permeance of 3815 L m−2 h−1 bar−1 (L m−2 h−1 bar−1, denoted as LMH bar−1)—almost two orders of magnitude greater than commercially available membranes and 2D nanosheets with comparable separation performance40,41. Notably, the filtration process with MCM required only 1.3 min, which is 115 times faster than the soaking process (Fig. 4c). The in situ formation of metal-phenolic networks on the MCM-60 effectively separated CIP molecules from simulated wastewater, providing a cost-effective solution for large-scale membrane production and practical applications.

Figure 4d illustrates that MCM-60 effectively removed CIP molecules from simulated wastewater, with removal rates varying with the soaking time in FeCl3 solution (Supplementary Fig. 6). Extending the soaking time from 2 to 1440 min resulted in a progressive increase in removal rate from 91.2% to 99.3%, accompanied by a decrease in permeance from 4680 to 3210 LMH bar−1. Notably, even with a short soaking time of 2 min, MCM-2 achieved a removal rate of 91.2%, underscoring the substantial role of metal-phenolic networks in antibiotic removal. Removal rates continued to increase with a soaking time of up to 60 min, after which further improvements were limited, and permeance declined. Therefore, a soaking time of 60 min was deemed optimal for MCM fabrication.

The outstanding CIP separation performance prompted an evaluation of concentration polarization effects on MCM-60, revealing a significant impact on membrane performance (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Fig. 7). The removal rate decreased from 96.7% to 50% as CIP concentration increased from 10 to 50 mg L−1, although permeance remained relatively stable despite decreased removal rates. Figure 4f demonstrates the effect of applied pressure on MCM-60 separation performance. Removal rates remained stable at approximately 96% for CIP removal at pressures ranging from 0.2 to 0.5 bar, but decreased slightly at 1 bar and 1.5 bar (Supplementary Fig. 8). The observed reduction in removal rates at pressures exceeding 0.5 bar may be due to physical defects, while permeance increased up to 4750 LMH bar−1. This characteristic presents a straightforward method to dynamically enhance MCM separation properties through applied pressure.

A high-performance separation membrane should exhibit high flux, high removal rates, and robustness under varying environmental conditions. To assess membrane robustness, MCM was immersed in solutions with pH values ranging from 1 to 12 for one hour, followed by permeation tests (Fig. 4g, Supplementary Fig. 11, Supplementary Fig. 12). The MCM membrane maintained a high flux of approximately 3800 LMH bar−1 and a > 96% removal rate for CIP after immersion in solutions with pH values from 3 to 7, demonstrating its excellent stability attributed to the chemical resilience of the metal-phenolic networks under weak acidic and neutral pH conditions. However, in basic solutions, MCM-60 exhibited decreased removal and permeance values due to Fe(OH)3 precipitation42. Additionally, significant decreases in removal performance were observed in highly acidic solutions due to the protonation of polyphenol moieties, which disrupted CIP-phenolic complexation. Supplementary Fig. 4 demonstrates that the MCM-60 membrane exhibited a negative charge without an isoelectric point. Within the pH range of 3 to 10, the surface zeta potential shifts to a more negative value as pH increases, varying from −12 to −24 mV. The outcome aligns with the preservation of enhanced permeance and adsorption efficiency across a pH range of 3 to 12 (Fig. 4g).

Motivated by the impact of protonation and disruption of CIP-phenolic complexation, MCM-60 was immersed in an acidic solution with pH = 1 to dismantle the metal–phenolic network (Fig. 4h, Supplementary Fig. 13). After two hours of immersion, the MCM membrane lost its CIP removal performance, resembling that of the pristine commercial nylon membrane. Nevertheless, after 12 h, the MCM membrane exhibited improved CIP separation capability, potentially due to the reloading of polyphenol-related compounds onto the membrane surface.

Membrane stability is critical for sustained operational effectiveness. CIP separation experiments conducted after MCM-60 immersion in water at various temperatures (Fig. 4i, Supplementary Fig. 9, Supplementary Fig. 10) showed comparable CIP removal rates with thermal treatments up to 55 °C for one hour. Treatment at 55 °C achieved a removal rate of 96.3%, comparable to that at 25 °C, indicating the MCM-60 retains stability for CIP separation at temperatures up to 55 °C. However, higher thermal treatments resulted in reduced removal performance and permeance. Treatment at 95 °C resulted in a diminished separation performance of 70% and a lowered permeance of 2750 LMH bar−1, owing to the decomposition of tannic acid at high temperatures, leading to the disintegration of metal-phenolic networks (MPNs) and membrane blockage33. Consequently, the thermal stability of MCM is constrained by the stability of tannic acid, with stable separation performance observed below 55 °C.

Stability of MCM membrane

The protonated MCM membrane was subjected to treatment with tannic acid and FeCl3 solutions to evaluate its performance over multiple filtration cycles (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. 14). The MCM-60 membrane was initially soaked in 0.1 M HCl for 1 h to remove the TA and Fe adhered to the membrane, as well as the CIP adsorbed on it, and later washed with deionized water. Then, we reloaded the TA/Fe complex in the tannic acid and FeCl3 solution to assess its adsorption performance (Supplementary Fig. 15). Filtration experiments over ten cycles revealed that the MCM-60 membrane exhibited varying CIP removal efficiencies in the initial five cycles, ranging from 91.7% to 98.1%. Nonetheless, the membrane maintained a high removal efficiency of 99.4% after ten cycles, indicating its robust performance in antibiotic removal. However, a reduction in flux was observed, attributable to residual nanoparticles remaining on the membrane, with flux decreasing from 3815 LMH bar−1 in the first cycle to 2615 LMH bar−1 in the tenth cycle. These observations suggest that the micropores within the membrane remain effective even after prolonged operation.

a Regeneration for cycle test of the MCM-60. Note: CIP (10 mg L−1), gas pressure of 0.4 bar. b Variation of flux and rejection of MPN membranes loading on commercial PTFE, MCE, and PES substrate. c Variation of flux and rejection of MPN membranes operated for CHL, TET, OXY, and DOX removal tests. d Tensile strength of the MPN modified composite membranes with different treating times with FeCl3. The inset shows the fracture of MCM-60. Note: Values are mean (n = 3) ± standard deviation. e Comparison for the MPN-modified composite membranes in this study with other membranes (water permeance vs. removal efficiency)43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52.

The broader applicability of this strategy for antibiotic elimination was further demonstrated using commercial PTFE, MCE, and PES membranes, all exhibiting a comparable pore size distribution of 200 nm (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 16, Supplementary Fig. 17). The loading of metal-phenolic coating onto MCE and PES substrates resulted in comparable CIP removal efficiencies, with rates of 93.0% and 93.2%, respectively. MCE and PES membranes exhibited higher permeance compared to nylon, highlighting nylon’s significance due to its lower cost and extensive applicability. The stability of the nylon membrane across various solutions and environmental conditions underscores its potential for practical applications.

To assess the versatility of MCM in antibiotic removal, the MCM-60 membrane was tested for the removal of chloramphenicol (CHL), tetracycline (TET), oxytetracycline (OXY), and doxycycline (DOX) (Fig. 5c). At a concentration of 10 mg L−¹, MCM-60 demonstrated improved removal rates for CHL (45.5%), TET (46.8%), OXY (52.0%), DOX (67.5%), and CIP (96.7%), compared to the nylon membrane’s lower removal rates for CHL (15.5%), TET (18.1%), OXY (33.2%), DOX (13.3%), and CIP (24.3%) (Supplementary Fig. 18,19). The enhanced removal rates for these antibiotics may be attributed to their molecular size, surface charge, and microstructure.

For practical applications, membrane materials must possess adequate mechanical strength. Figure 5d illustrates the tensile strength of MPN-modified composite membranes (5 mm × 10 mm) exposed to different durations of FeCl3 solution treatment. An increase in FeCl3 treatment duration resulted in a corresponding enhancement in the mechanical strength of the MCM. Extended soaking in FeCl3 promotes the localization and stabilization of MPN on the nylon substrate, thereby improving the mechanical strength of the MCM (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Fig. 20). Notably, MCM-60 exhibited a mechanical strength of 35.5 ± 6 MPa, comparable to that of conventional polymeric membranes. Tannic acid functions as an interlocking agent, forming robust hydrogen bonds between iron ions and nylon, thereby establishing active sites for MCM without compromising mechanical integrity. Although MCM-1440 exhibited the highest strength, it required a longer fabrication period. These results underscore the satisfactory mechanical stability of the prepared MCM, enhancing its practical utility.

In terms of separation performance, the permeance of MCM-60 is approximately two orders of magnitude higher than that of other reported nanofiltration membranes with comparable antibiotic removal efficiencies (Fig. 5e, Supplementary Table 1)43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52. MCM-60 even surpasses MXene and graphene-based membranes in performance. The elevated permeance is due to the membrane’s intricate structure and extensive pore size distribution, while the evenly deposited MPN on the membrane surface dramatically enhances antibiotic elimination capacity.

The outstanding performance of the adsorptive membrane for antibiotic removal from aqueous environments can be attributed to four key factors. First, the hydrophilic properties of the MCM-X membranes facilitate the effective absorption of antibiotic molecules from water, enabled by the deposition of TA-Fe nanoparticles on the nylon substrate. The dendritic and porous nature of the nylon substrate provides an optimal platform for the in-situ polymerization of TA-Fe nanoparticles through reversible coordination bonds, which minimizes local aggregation40. This is confirmed by SEM, WCA, XPS, FTIR, Raman, and XRD investigations, validating the effective synthesis of TA-Fe nanoparticle coatings on the nylon surface, enhancing the adsorption affinity for antibiotics. Second, due to the presence of phenolic groups, the TA-Fe nanoparticles significantly contribute to interfacial interactions during the adsorption of antibiotic molecules onto the MCM membrane. The adsorption process is governed by hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, and π-π stacking between the antibiotic molecules and TA-Fe nanoparticles. The π-conjugated aromatic rings of both the antibiotics and tannic acid facilitate these interactions, while the negatively charged TA-Fe nanoparticles attract the positively charged groups of ciprofloxacin through electrostatic forces14. Thus, the structural characteristics of TA-Fe nanoparticles facilitate specific adsorption of antibiotics onto the MCM membranes. Third, the stability and performance of the protonated MCM membrane during cyclic tests underscore its suitability for practical applications. The TA-Fe nanoparticles exhibit stability across a broad pH range, demonstrating the membrane’s potential for real-world applications. However, the membrane’s adsorptive capacity significantly diminishes in solutions with a pH below 2. Notably, the membrane’s adsorptive performance can be restored by dismantling the antibiotics-TA-Fe complex through treatment with an acidic solution. The membrane’s remarkable regeneration capability and sustained adsorptive performance significantly extend its operational lifespan, thereby reducing overall costs. Fourth, the porous structure of the nylon substrate facilitates a rapid filtration process. Although the deposition of TA-Fe nanoparticles partially occludes the pores and results in a slight reduction in water flux, the inherent porosity of the nylon substrate promotes the effective growth of TA-Fe nanoparticles on its surface. Consequently, the MCM membrane exhibits a significantly shorter removal time compared to most reported nanofiltration membranes while maintaining comparable efficiency in antibiotic removal.

In summary, this study introduces a novel, straightforward methodology for fabricating cost-effective and highly efficient adsorption and separation membranes by integrating metal-phenolic coatings onto commercially available membrane substrates. This process yields a distinctive metal-phenolic composite membrane (MCM). The coatings are synthesized through the in-situ polymerization of polyphenol building blocks and metal ions via reversible coordination bonds, which ensures robust stability in aqueous environments. The MCM membranes exhibit markedly enhanced performance in antibiotic removal from aquatic systems under applied pressure, significantly outperforming uncoated membranes. Specifically, these membranes demonstrate impressive permeance in aqueous solutions, achieving a high antibiotic ciprofloxacin hydrochloride removal efficiency of 3815 LMH bar−1 with a 96.7% removal ratio from simulated wastewater. These results suggest that the MCM membrane offers a promising solution for efficient antibiotic removal and consistent resource purification.

Methods

Materials

Titanic acid was procured from Macklin, while FeCl3·6H2O was obtained from Aladdin. Ciprofloxacin Hydrochloride (CIP, C17H19ClFN3O3, 367.802 g mol−1) was obtained from Bide Pharmatech. Tetracycline (TET, C22H24N2O8, 444.44 g mol−1) was purchased from Macklin. Oxytetracycline dihydrate (OXY, C22H24N2O9·2H2O, 496.46 g mol−1), doxycycline hydrochloride (DOX, C22H24N2O8·HCl, 480.9 g mol−1), chlortetracycline hydrochloride (C22H24Cl2N2O8, 515.341 g mol−1), and potassium chloride (KCl) were acquired from Aladdin. Hydrochloric acid (HCl) was obtained from Xilong Scientific. All chemicals were utilized as received. Commercial nylon and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membranes were bought from Zhejiang Yibo Separator Company. Polyethersulfone (PES) membranes were bought from Titan, while mixed cellulose ester (MCE) membranes were obtained from Jinteng. All selected commercial membranes have an average pore size of 0.22 μm.

Fabrication of the MCM membranes

The MCM membranes were prepared by alternately soaking the commercial membrane in tannic acid (4 g L−1) and FeCl3·6H2O solution (1 g L−1). Commercial substrates were selected due to the robust structural stability under both acidic and alkaline conditions. The nylon membrane was initially immersed in a tannic acid solution for 2 h, ensuring complete wetting and the thorough adsorption of tannic acid molecules, forming the nylon/TA composite. This composite was then immersed in a FeCl3 solution for a predetermined duration to synthesize the MCM. The membranes produced are designated as MCM-X, where X corresponds to the soaking duration in minutes during fabrication. The MCM underwent three successive immersions in deionized water following fabrication to eliminate any residual precursors.

Characterization

XRD analysis was performed using a Bruker D8 Advance (Cu Kα radiation source, λ = 1.5406 Å) with the 2θ ranging from 5 to 60° with intervals of 0.02°. The FTIR spectra were measured on a Thermofisher Nicolet IS50 infrared spectrometer (USA). The membrane morphologies were observed by using an S-4800 scanning electron microscope (Hitachi, Japan) with an accelerating voltage of 3 kV. AFM images were collected on an Asylum research MFP3D microscope. The UV-Vis absorption spectra were conducted by a UV-2550 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan). XPS spectra were obtained with an ESCALAB 250XI photoelectron spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). Raman spectra were collected on a LabRAM HR Evolution confocal laser Raman spectrometer (Horiba Jobin Yvon, France). Contact angle tests were conducted by using a GR001PC130D contact angle tester (Jinzhitang, China).

Antibiotic removal performance evaluation

The antibiotic removal performance of the membrane was assessed using a dead-end filtration device, employing a testing solution volume of 100 mL. To mitigate the concentration polarization effect, 40 mL solutions were passed through the membrane to control polarization, particularly for separating antibiotic molecules. The effective filtration area of the membrane was 10.75 cm2. Before testing, all membranes were initially filtrated with pure water until constant fluxes were achieved. A fixed transmembrane pressure of 0.4 bar was applied. The concentration of feed, permeate, and retentate solutions were determined using a UV-vis spectrophotometer.

The permeance J (L m−2 h−1 bar−1) and removal efficiency (R, %) were collected and calculated according to the following equation:

where V is the permeated volume of solvent (L), A is the effective filtration area of the membrane (m2), Δt is the filtration time (h), ΔP is the pressure applied (0.4 bar), C0 is the concentration of antibiotics in the feed, and C is the concentration of antibiotics in the permeate.

Soaking adsorption experiments

To study the adsorption kinetics of antibiotics ciprofloxacin hydrochloride removal from water, the modified membrane with the same amount of metal–phenolic networks was soaked into a 40 mL solution with a concentration of 10 mg L−1. Samples were collected at a specified time, and UV absorption was subsequently measured. The adsorption test was allowed to reach adsorption equilibrium for 24 h. Then, the retention concentration of antibiotics ciprofloxacin hydrochloride was determined to calculate the equilibrium adsorption capacity.

Zeta potentials measurements of the membrane

Zeta potentials measurement was made using the SurPASS electrokinetic analyzer (Anton Paar surpass 3, Austria). We performed a pH titration at room temperature, ranging from pH 3 to 10, using a 0.001 M KCl solution. The solution pH was adjusted by adding KOH or HCl.

Responses