Methylstat sensitizes ovarian cancer cells to PARP-inhibition by targeting the histone demethylases JMJD1B/C

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death among gynecological malignancies [1]. As early disease is mostly symptom-free, about 75% of ovarian cancer patients are diagnosed at advanced stages. Standard treatment of advanced ovarian cancer consists of radical debulking surgery, aiming at macroscopic complete tumor resection and platinum/paclitaxel-based chemotherapy, in addition to maintenance treatment with antiangiogenic bevacizumab [2,3,4]. In patients with homologous recombination (HR) deficiency (HRD), defined by either genomic instability and/or a pathogenic breast cancer 1/2, early onset (BRCA1/2) mutation, a combination of bevacizumab and the poly ADP ribose polymerase inhibitor (PARPi) olaparib has been approved as maintenance therapy after response to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy [5]. Moreover, part of standard treatment is (i) olaparib and bevacizumab in HRD positive patients (ii) olaparib monotherapy in patients with BRCA1/2 mutation or (iii) niraparib independently of HRD-status [6, 7]. In the platinum-sensitive recurrent setting, the PARPis olaparib, niraparib and rucaparib can be used as maintenance therapy, regardless of HRD in high grade serious ovarian cancer [8,9,10,11]. Nevertheless, the majority of patients with recurrent ovarian cancer develop PARPi resistance, resulting in poor overall prognosis. Therefore, uncovering the genetic basis of PARPi response is of high clinical interest, in order to guide the design of innovative targeted therapy approaches for ovarian cancer patients.

We have previously established an in vitro model of PARPi-resistant ovarian cancer by long-term exposure of BRCA1-deficient UWB1.289 ovarian cancer cell lines to olaparib [12]. The resulting derivative cell-line (Olres-UWB1.289) exhibited an EMT-like phenotype and was characterized by a broad spectrum of cross-resistance toward other clinically relevant PARPis and chemotherapeutic drugs. Using a dual-fluorescence clonal competition assay, we demonstrated that Olres-UWB1.289 cells mirror typical dynamics of therapy resistance, shaped by their strong positive selection under olaparib treatment, their abilility to outcompete PARPi-sensitive cells in co-culture, and their “fitness penalty” under drug-free conditions [12].

Loss-of-function genetic screening by CRISPR/Cas9 has been proven as powerful tool for exploring the genetic basis of various disease-related processes [13, 14], including PARPi response in cancer [15,16,17,18,19]. However, the repertoire of genes, involved in PARPi-resistant ovarian cancer, has incompletely been studied and its clinical translation remains elusive. Therefore, using our previously established model system of acquired PARPi-resistance [12], we aimed at identifying genetic determinants of PARPi response. To this end, we performed a CRISPR-Cas9 mediated loss-of-function screening with a focused sgRNA library, targeting 1.572 human genes, including kinases, cell surface proteins and epigenetic regulators. Identified gene candidates were finally used to design and experimentally validate an optimal pharmacological strategy for PARPi sensitization in ovarian cancer.

Material and Methods

Cell Culture

All cell lines were maintained in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Detailed information on the composition of culture media, is summarized in Supplementary Table 1. The cell lines were tested regularly for mycoplasm by a commercial in-house service.

Generation of PARPi-resistant cell lines

PARPi-resistant Olres-UWB1.289 and Olres-UWB1.289+BRCA1 were generated as described previously [12]. Briefly, parental UWB1.289 or UWB1.289+BRCA1 cells had been cultured under continuous exposure to incrementally ascending olaparib concentrations for 11 months, beginning from 10 nM. Final olaparib maintenance level for PARPi-resistant derivative cell lines was adjusted, according to the inherent olaparib sensitivity of the parental cell lines, resulting in 10 µM or 60 µM, respectively [12]. PARPi-resistant Igrov-1, KB1P and KB1P+BRCA1 cells were generated in analogy to our previous model, with final maintenance levels of 60 µM, 4 µM or 60 µM olaparib, respectively.

Drugs

Olaparib (AZD2281; #S1060, PARP1) [20], 1-Napthyl-PP1 (#S2642, target: ABL1) [21, 22], Imatinib (#S2475, target: ABL1) [23,24,25,26,27], Dasatinib (#S1021, target: ABL1) [25, 28,29,30], Sodium orthovanadate (#S2000, target: ATP1A3) [31, 32], Remodelin hydrobromide (#S7641, target: NAT10) [33], Entrectinib (#S7998, target: PAN3-NTRK2 fusion, TRIM24-NTRK2 fusion) [34, 35], Larotrectinib (#S5860, target: PAN3-NTRK2 fusion, TRIM24-NTRK2 fusion) [34, 36], Dorsomorphin dihydrochloride (#S7306, target: AMPK and its subunit PRKAB2) [37], Selumetinib (#S1008, target: STK35-BRAF fusion, TRIM24-BRAF fusion) [38], Stattic (#S7024; target: STAT3, upstream of STK35) [39, 40], PFI-90 (#S9882; JMJD1B) [41], GSK-J1 (#S7581, KDM6A, KDM6B) [42,43,44], IOX-1 (#S7234, target: JMJD1A, KDM4C, KDM6B, KDM2A, KDM4E, KDM5C, PHD2, ALKBH5) [45, 46], GSK-LSD1 2HCl (#S7574, target: LSD1) [47, 48] were purchased from Selleckchem (Munich, Germany). Methylstat (#SML0343; selective inhibitor of Jumonji C domain-containing histone demethylases, including JMJD1B, JMJD1C) [49] was purchased from Sigma Aldrich and Metformin (#317240-5 G, target: SP1) [50] from EMD Millipore.

CRISPR-Cas9 library design

The sgRNA library was designed to cover six protein classes, i.e., kinases, cell surface proteins [51], nuclear receptors, epigenetic factors, transcription factors and uncharacterized genes (Supplementary Table 2). Each gene was targeted with 3-12 different sgRNAs, selected to specifically bind to either the first exon, an early splicing site or the functional domain of the protein. All sgRNAs were chosen to fulfill the criteria defined by Doench et al. [52]. The complete library consisted of 10,722 sgRNAs targeting 1572 genes. 636 sgRNAs were included to target 45 essential and 47 non-essential control genes [53] (Supplementary Table 2). Oligonucleotides with sgRNA sequences were ordered as arrayed synthesis from CustomArray Inc. and PCR amplified (primer, forward: 5′-GATATTGCAACGTCTCACACC-3′, reverse: 5′-GTCGCGTACGTCTCGAAAC-3′). The resulting PCR product was cloned into the lentiviral vector pL.CRISPR.EFS.tRFP (Addgene; #57819) using the Esp3I restriction sites. The vector contained a modified tracr sequence (5′-GTTTAAGAGCTATGCTGGAAACAGCATAGCAAGTTTAAATAAGGCTAGTCCGTTATCAACTTGAAAAAGTGGCACCGAGTCGGTGCTTTTTTT-3′), as described previously [54].

Lentiviral CRISPR-Cas9 loss-of-function screen

Lentivirus production was adapted from our previously described protocol [12, 55]. HEK293T cells were transfected with a three-plasmid split-genome packaging system. Per viral transduction of 0.5 × 106 Olres-UWB1.289 target cells, 12 µg of the pL.CRISPR.EFS.tRFP transfer vector (Addgene, 57818) DNA, encoding for Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 and a sgRNA from the library, respectively, was mixed with 12 µg psPAX2 DNA (Addgene, 12260), 6 µg pMD2.G DNA (Addgene, 12259) and 62 µl of 2 M CaCl2 in a final volume of 500 µl. Subsequently 500 µl of 2x HBS phosphate buffer was dropwise added to the mixture and incubated for 10 min at room temperature (RT). The 1 ml transfection mixture was then added to 50% confluent HEK293T cells, seeded the day before into a 10 mm dish. Cells were incubated for 16 h (37 °C and 5% CO2) and the medium was changed to remove remaining transfection reagent. Lentiviral-supernatants were collected 36 h post-transfection and for each infection, 3 ml supernatant containing 4 mg/ml polybrene was immediately used to infect Olres-UWB1.289 cells [12], seeded the day before in 10 mm dishes to reach around 50% confluency at infection. Infected cells were incubated for 24 h, followed by a medium change to remove virus particles. Six days after infection, transduction efficiency was determined by flow cytometric tRFP analysis, followed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) of tRFP-positive cells using a BD FACSAria™ Fusion cell sorter. According to titration experiments, viral supernatant from HEK293T cells was 10-fold diluted with culture medium to result in 30% transduction efficacy. In order to enable a representative projection of the CRISPR-Cas9 library on target cells, a total of 2.25 × 107 Olres-UWB1.289 cells were transduced, followed by sorting of 2.4 million tRFP-positive cells and a 19-day neutral expansion period. For recording baseline library composition, genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from five million cells using the QiAmp DNA blood kit (Qiagen, 51104). The remaining population was maintained in culture. Finally, two parallel sets of library-transduced tRFP-positive cells were seeded (5 million each, T75 flask format) for i) growth under drug-free conditions and ii) growth under 4 µM olaparib selection pressure. After eight days, gDNA was extracted from both conditions.

Isolated gDNA samples were used to amplify sgRNA sequences by two rounds of PCR, with the second-round primers containing adaptors for Illumina sequencing (PCR 1, forward 5′-GTAATAATTTCTTGGGTAGTTTGCA-3′, reverse 5′-ATTGTGGATGAATACTGCCATTTG-3′; PCR 2, forward 5′-ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTGGCTTTATATATCTTGTGGAAAGG-3′, reverse 5′- GTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTCAAGTTGATAACGGACTAGCC-3′). After targeted PCR amplification, the samples were indexed for NGS sequencing in a successive PCR enrichment followed by purification and capillary electrophoresis (Fragment Analyzer, Agilent). The resulting libraries were sequenced with single-end reads on a NextSeq 500. The sequence reads were mapped to sgRNA sequences using PatMaN [56], a rapid short sequence aligner. As a set of query patterns, we used sgRNA sequences flanked by 5′-GACGAAACACCG-3′ and 5′-GTTTAAGAGCTA-3′ on the termini, respectively, and allowed two mismatches during the alignment step. For each read, the best matching gRNA sequence was picked. In case of ties, the read was discarded as ambiguous. For each sample, counts of reads, mapped to each sgRNA from the library, were calculated.

Generation of CRISPR/Cas9 knockout cell lines

For targeted gene knockout, sgRNAs against the respective gene of interest were designed (Supplementary Table 4). As control, a sgRNA targeting a gene desert site in the genome, referred to as safe target (STC3)-control or a non-targeting sgRNA with no homologies to the human genome (nt-control) was used. For lentiviral transduction, the same basic protocol was used as described above. A total of 0.4 × 106 Olres-UWB1.289 were transduced with 0.7-fold diluted viral supernatant, resulting in transduction efficacies below 80% (range 29.4–76.2%) in order to avoid off-target effects, due to excessive integration events in the target cells. After a culture period of two weeks, genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated from the transfected cells using the QiAmp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, 51104). Subsequently, the gRNA binding region was amplified by PCR and subjected to Sanger sequencing. The indel rates were analyzed using the Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE) Analysis Tool (Performance Analysis, ICE Analysis, 2019, V3.0, Synthego). In case of a polyclonal knockout efficiency <70%, cell lines were subjected to single cell sorting and monoclonal expansion.

Photometric Cell Viability Assay

Cell viability assays were performed as described previously [12, 57]. Briefly, cells were seeded on 6-well plates and cultured in standard medium for 24 h to allow adherence. Subsequently, drug treatment was performed for 6 days. On day 7, cells were fixed with 0.1% methanol and stained with 0.1% crystal violet solution. For viability readouts, the cell-bound violet dye fraction was dissolved by 10% acetic acid and photometrically quantified using the Tecan Reader (Infinite M200, Männedorf, Switzerland, Software Magellan Version 7.2). IC50 values were determined by non-linear regression using Prism Version 10.0 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA).

Drug interaction analysis

For drug interaction analysis of the PARPi olaparib with the respective small molecule inhibitor, a series of drug combination treatments at equipotent molar concentrations were performed (IC6.25, IC12.5, IC25, IC50 and IC100 [58]). Drug interaction was classified, according to photometric cell viability assays and the combination index (CI) method [57, 58]. For each equipotent combination, a CI-value was calculated using CalcuSyn Version 2.11 (Biosoft, Cambridge, UK). A CI-value < 0.9 indicates a synergistic interaction [58]. Synergyfinder2.0, calculating the Bliss and HSA synergy scores, were used as independent reference models for the classification of drug interactions. A score >10 indicates synergy.

Dual-fluorescence clonal competition assay

The effect of methylstat treatment on the clonal dynamics of PARPi-resistant cells was analyzed, as described previously [12]. Briefly, a mixture of 7,000 cells/well (50% UWB1.289-pWPXL-tdTomato and 50% Olres-UWB1.289-pWPXL-eGFP or 50% UWB+BRCA1-pWPXL-eGFP) were seeded into a black 96-well plate (costar®; Corning Incorporated, 3603) and treated one day later with 10 µM olaparib or the combination of 10 µM olaparib and 3 µM methylstat. eGFP and tdTomato fluorescent cells were counted using the CeligoS Image Cytometer (Nexcelom Bioscience Ltd, Lawrence, MA, USA).

γH2AX Western Blot analysis

From treated cell lines, 20 µg protein per sample was subjected to a NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris protein gel (Invitrogen by Thermo Fisher Scientific; #NP0321BOX) and transferred onto nitrocellulose (NC) membranes (0.45 µm NC, Thermo Fisher Scientific; #88018). Subsequently, (dissected) NC-membranes were incubated with Anti-ß-Actin (clone AC-74; mouse; Sigma-Aldrich, #A5316; 1:100000) and Anti-phospho-histone H2A.X (Ser139; clone JBW301; mouse; Sigma-Aldrich, #05-636; 1:1000) antibodies. Membranes were incubated for detection with secondary antibodies, raised against mouse (Peroxidase-conjugated AffiniPure Goat anti-Mouse IgG, HRP linked; Jackson ImmunoResearch; #115-035-003). Detection was performed with Amersham™ ECL™ Prime Western Blotting Detection reagent (Cytiva, Freiburg, Germany; #RPN2232). The quantification was performed using the Fiji Software and results were visualized by Prism 10.2.3 (GraphPad Software).

Statistics

Basic statistical analysis was performed using Prism 10.2.3 (GraphPad Software). Viability assays were analysed by nested t-test and the IC50 was determined with nonlinear regression. Drug interaction was assessed using CI-value calculation, Calcusyn 2.11 (Biosoft) and the Bliss/HSA model based on the Synergyfinder2.0 software. For more than two comparisons within selected datasets, the one-way ANOVA test with post-hoc Tukey, Dunnet or Šídák correction was used.

Results

CRISPR-Cas9 loss-of-function screen for the identification of genetic determinants of PARPi response

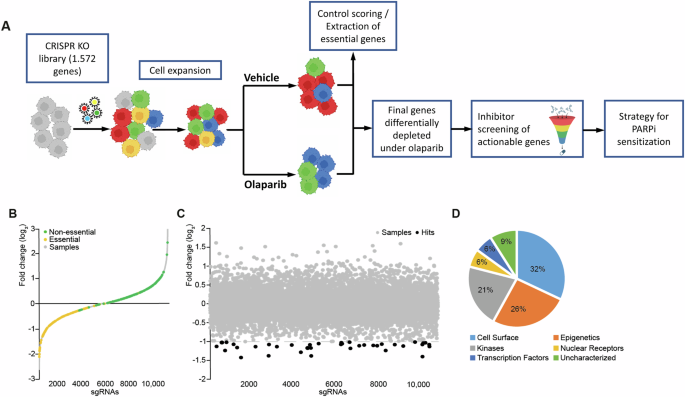

We performed a lentiviral pooled loss-of-function screen in PARPi-resistant Olres-UWB1.289 cells [12] using Cas9 from S. pyogenes. The screen was based on a tailor-made sgRNA library targeting 1572 human candidate genes that cover a pre-selection of various protein classes including kinases, epigenetic regulators and cell surface proteins (Supplementary Table 2). As a first step, we confirmed appropriate control scoring of our CRISPR-Cas9 setup. To this end, lentiviral delivery of the sgRNA library to Olres-UWB1.289 was performed. Changes in the composition of the pre-defined control sgRNA sequences (n = 636) [53] were determined by deep sequencing after neutral expansion of cells for eight days under drug-free conditions (Fig. 1A). While 38 of 45 (84%) essential control genes for cell homeostasis, were depleted (log2 <-0.5; Fig. 1B), 283 of 326 sgRNAs (87%) targeting non-essential control genes were increased or only mildly depleted (log2 > -0.5; Fig. 1B). This confirmed technical validity of our CRISPR-Cas9 platform and showed that the library composition is accurately mirroring the expected negative or positive selection effects of control knockout genotypes.

A Schematic overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 loss-of-function screen and its translation into a pharmacological strategy for PARPi sensitization. PARPi-resistant Olres-UWB1.289 cells were transduced with a sgRNA library in order to identify genes, negatively selected under olaparib treatment. Pharmacological inhibitors targeting hit genes were screened for a synergistic interaction with olaparib. B sgRNA frequencies (log2 of fold change) normalized to baseline after gene knockout and cell expansion. Fold changes of sgRNA are shown in gray and highlighted for essential (yellow) and non-essential (green) control genes. C Fold changes in the sgRNA pool composition (log2) after treatment with olaparib normalized to the vehicle control. sgRNA frequencies (gray) of depleted genes (dashed line) are shown; hit genes (black, red), JMJD1B/C (red) are highlighted. D Protein class distribution of hit genes.

As a second step, we excluded additional target genes from our library, whose sgRNA sequences were depleted under the above-mentioned drug-free growth period (log2 < -0.5), as they were essential for cell homeostasis and not specifically involved in PARPi response (Fig. 1B). Lastly, we filtered for a cleaned set of hit genes, whose sgRNA sequences were differentially depleted under seven days of olaparib selection pressure by at least two-fold (Fig. 1B–D, Supplementary Table 3). The majority of hit genes were transcription factors (32%), followed by epigenetic regulators (26%) and kinases (21%; Fig. 1D).

Conclusively, we identified a final set of 34 candidate genes, promoting PARPi resistance in Olres-UWB1.289 cells (Fig. 1C, Supplementary Table 3).

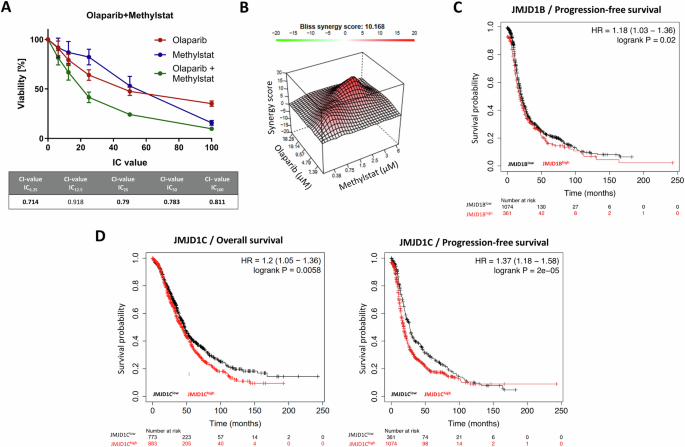

Translation of the CRISPR-Cas9 screening results into a pharmacological strategy for PARPi sensitization

We reasoned that pharmacological targeting of the above-identified genetic determinants of PARPi resistance will result in PARPi (re-)sensitization in Olres-UWB1.289 cells. For 12 of 34 identified candidate genes, commercially available inhibitors on protein level were available (Table 1). For orthogonal validation of the CRISPR-Cas9 screening results, we tested each inhibitor for a potential synergistic interaction with olaparib in Olres-UWB1.289 cells [12], using the combination index (CI) method [58] (Supplementary Fig. 1). Most of the inhibitors, particularly dorsomorphin (targeting PRKAB2 [37]), imatinib (targeting ABL1 [23,24,25,26,27]) or larotrectinib (targeting PAN3, TRIM24 [34, 36]), exhibited mostly antagonistic or additive interaction with olaparib, indicated by CI-values > 0.9 (Table 1; Supplementary Fig. 1). Methylstat, a small molecule inhibitor of Jumonji C domain-containing histone demethylases (JMJD) [49], targeting JMJD1B and JMJD1C proteins, was the drug with the most consistent synergistic interaction with olaparib across the total dosage range (CI = 0.71–0.81; Table 1; Fig. 2A), suggesting it as candidate drug for PARPi sensitization in ovarian cancer. A synergistic interaction of methylstat and olaparib was confirmed by independent reference models (Bliss/HSA synergy score; Fig. 2B, Supplementary Fig. 2). According to public databases (TCGA), we inferred that high expression of either JMJD1B or JMJD1C indicates poor prognosis in ovarian cancer patients, corroborating their pro-tumorigenic function in ovarian cancer (Fig. 2C, D).

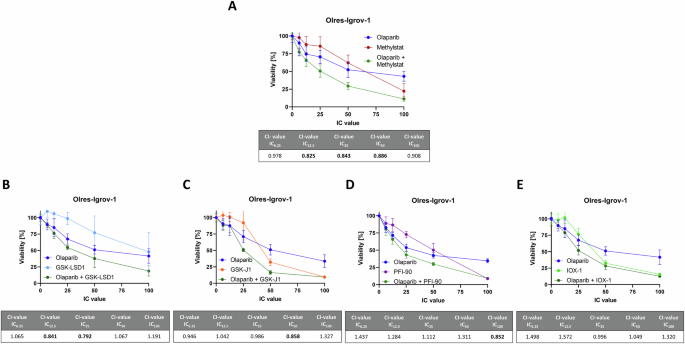

A Drug interaction analysis of methylstat and olaparib according to the combination index (CI) method. Drugs were combined at a broad range of equipotent molar concentrations, according to the indicated IC100, IC50, IC25, IC12.5, IC6,25. Standard deviation from three independent experiments is indicated by error bars. Resulting CI-values are indicated in the table. A drug interaction with a CI-value < 1.0 is classified as synergistic (bold numbers). B Drug interaction analysis of methylstat and olaparib according to Bliss synergy score calculation. A score >10 indicates synergy. Results were derived from three independent biological replicates. Kaplan-Meier analysis showing prognostic relevance of (C) JMJD1B and (D) JMJD1C according to the publicly available Kaplan-Meier plotter tool. PFS progression-free survival, OS overall survival.

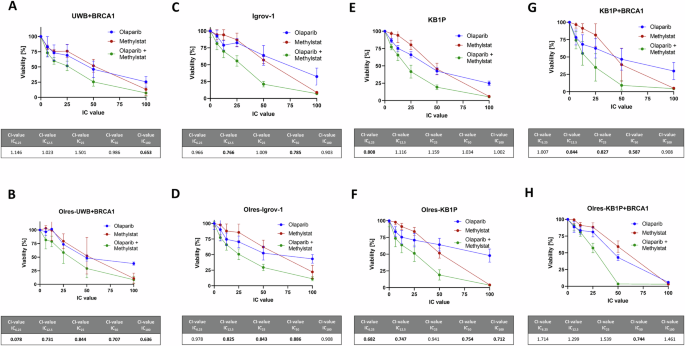

The PARPi sensitizing effect of methylstat could be further validated by independent in vitro models of PARPi-resistance according to human ovarian cancer (Supplementary Fig. 3A; Fig. 3A–D) or murine breast cancer (Supplementary Fig. 3B-C; Fig. 3E–H). In this context, methylstat treatment resulted in a broad spectrum of olaparib sensitization among PARPi-resistant (Olres-UWB+BRCA1, Olres-Igrov-1, Olres-KB1P, Olres-KB1P+BRCA1; Fig. 3B, D, F, H) and PARPi-sensitive (UWB+BRCA1, Igrov-1, KB1P, KB1P+BRCA1; Fig. 3A, C, E, G) cell lines. This effect was independent from the BRCA1 mutational status of the cells, as we observed a synergistic interaction between methylstat and olaparib among isogenic pairs of BRCA1-proficient vs. BRCA1-deficient cell lines (Fig. 3A, B, E, F, G, H). Interestingly, the most efficient PARPi sensitization effect by methylstat was observed in the cell line with the lowest inherent PARPi response (BRCA1-proficient/PARPi-resistant Olres-KB1P cells), already resulting in a complete eradication of cells, when both drugs were combined at the IC50 (Fig. 3H).

Drug interaction analysis of methylstat and olaparib according to the combination index (CI) method with the indicated cell lines (A–H). Drugs were combined at a broad range of equipotent molar concentrations, according to the indicated IC100, IC50, IC25, IC12.5, IC6,25. Standard deviation from three independent experiments is indicated by error bars. Resulting CI-values are indicated in the table. A drug interaction with a CI-value < 1.0 is classified as synergistic (bold values). Results were derived from three independent biological replicates.

Taken together, we provide several lines of evidence that pharmacological targeting of the histone demethylases JMJD1B/C by the inhibitor methylstat results in an efficient PARPi sensitization in ovarian cancer cells, independently of the inherent PARPi-resistance status or the BRCA1 mutational background.

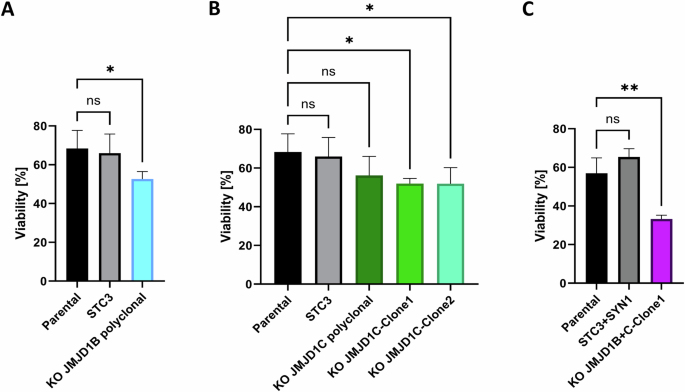

Effect of JMJD1B/C genetic depletion on PARPi sensitivity

To verify the functional contribution of JMJD1B/C in PARPi response, we performed genetic depletion of the JMJD1B gene by CRISPR-Cas9 in PARPi-resistant Olres-UWB1.384 cells. This resulted in a polyclonal derivative cell line with 72% JMJD1B knockout efficiency, showing a mild but significantly increased olaparib sensitivity compared to parental cells or the STC3 control knockout (difference 15.77%, padj = 0.04; Fig. 4A, Supplementary Table 5). Upon JMJD1C knockout, while olaparib response was not altered at a polyclonal knockout efficiency of 67%, monoclonal expansion resulted in two homozygous JMJD1C knockout clones with mildly decreased olaparib sensitivity (difference 16.4%, padj=0.04; 16.5%, padj = 0.03, respectively; Fig. 4B, Supplementary Table 5). Assuming that the histone demethylases JMJD1B/C cooperatively promote PARPi resistance in an additive manner, we subsequently generated homozygous monoclonal JMJD1B and JMJD1C knockout cells. Interestingly, the double knockout strongly increased olaparib sensitivity (difference 23.69%, padj=0.0039; Fig. 4C, Supplementary Table 5).

Viability of monoclonal or polyclonal PARPi-resistant Olres-UWB1.289 knockout cell lines for (A) JMJD1B (B) JMJD1C or (C) JMJD1B + C compared the control sgRNA-knockout (STC3/SYN1) or parental Olres-UWB1.289 is shown. P-values according to the one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey test are indicated; * padj < 0.05; ** padj < 0.01. Results were derived from three independent biological replicates.

Conclusively, genetic depletion of JMJD1B and JMJD1C phenocopied the PARPi sensitizing effect of methylstat in an additive manner, indicating a central role of these genes in promoting PARPi resistance.

Methylstat outperforms common demethylase inhibitors in their PARPi sensitization capacity

Using the Igrov-1 model of PARPi-resistant ovarian cancer, we compared the PARPi sensitizing effect of methylstat with commercially available DNA histone demethylases, including JMJD-specific inhibitors GSK-J1 (JMJD3, KDM6A) [42,43,44] and PFI-90 (JMJD1B) [41] and GSK-LSD1 [47, 48], a non-JMJD demethylase LSD1 inhibitor. Moreover, we tested the pan-demethylase inhibitor IOX1, targeting JMJD and non-JMJD demethylases [45, 46].

Among the total concentration range tested, GSK-LSD1 showed two synergistic interactions at IC12.5 and IC25, whereas GSK-J1, IOX-1 and PFI-90 showed only additive or a maximum of one synergistic interaction with olaparib. Most of the tested inhibitors showed PARPi sensitizing effect to certain degrees, however, they were clearly outperformed by the effect of methylstat, which provided synergistic interactions at IC12.5, IC25 and IC50 concentration levels (Fig. 5).

Drug interaction analysis of the indicated histone demethylase inhibitors with olaparib according to the combination index (CI) method with the indicated cell lines (A–E). Drugs were combined at a broad range of equipotent molar concentrations, according to the indicated inhibitory concentration (IC)100, IC50, IC25, IC12.5, IC6,25. Standard deviation from three independent experiments is indicated by error bars. Resulting CI-values are indicated in the table. A drug interaction with a CI-value < 0.9 is classified as synergistic (bold numbers). Results were derived from three independent biological replicates.

We conclude that methylstat is the most efficient PARPi sensitizer among the tested JMJD and non-JMJD histone demethylase inhibitors GSK-LSD1, GSK-J1 and PFI-90, as well as the pan-demethylase inhibitor IOX1.

Methylstat modulates clonal dynamics of PARPi-resistant or BRCA1-proficient ovarian cancer cells under olaparib selection pressure

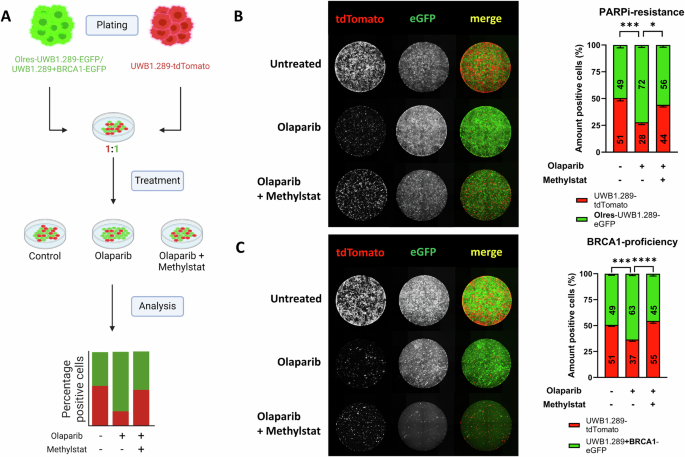

Taking advantage of our previously established dual-fluorescence clonal competition assay [12], we were interested in the effect of methylstat on the clonal dynamics of PARPi-resistant cells (Fig. 6A). Using lentiviral transduction, we color-coded PARPi-resistant (Olres-UWB1.289) with a green (eGFP) and parental PARPi-sensitive cells (UWB1.289) with a red (tdTomato) fluorescent marker protein [12]. After 14 days in co-culture under olaparib selection pressure, we observed a strong positive selection of PARPi-resistant compared to PARPi-sensitive cells (Fig. 6B; padj=0.0003). According to the previously described synergistic interaction between olaparib and methylstat, combined treatment with both drugs resulted in a strong reduction of overall cell numbers. Interestingly, methylstat mitigated the positive selection of PARPi-resistant cells, indicated by a stabilization of the ratio between resistant and sensitive cells towards a 50/50 proportion (Fig. 6B; padj=0.014).

A Schematic overview of a dual-fluorescence clonal competition model. Part of the scheme has been created with Biorender.com. Fluorescent microscopy images of (B) PARPi-resistant Olres-UWB1.289-EGFP vs. PARPi sensitive UWB1.289-tdTomato and (C) BRCA1-deficient UWB1.289-tdTomato vs. BRCA1-proficient UWB1.289+BRCA1-EGFP cell lines, co-cultured in the presence of drug-free medium, olaparib or methylstat+olaparib. P-values according to the one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey HSD test are indicated; * padj < 0.05; ** padj < 0.01; *** padj < 0.001. Results were derived from three independent biological replicates.

We subsequently investigated the effect of methylstat in a further co-culture model without acquired PARPi resistance, including parental BRCA1-deficient cells (UWB1.289+BRCA1) and their BRCA1-proficient isogenic counterparts (UWB1.289+BRCA1). Due to their inherently lower PARPi sensitivity, olaparib monotreatment resulted in a strong positive selection of BRCA1-proficient cells (Fig. 6C; padj=0.0007), which was mitigated by combined treatment with olaparib and methylstat (Fig. 6C; padj<0.0001).

Taken together, we demonstrate that methylstat mitigates positive selection of either PARPi-resistant or BRCA1-proficient ovarian cancer cells under olaparib treatment.

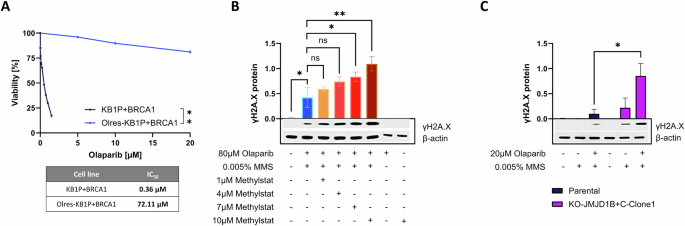

Methylstat increases susceptibility towards olaparib induced DNA double strand break formation

It is widely accepted that the increased formation of DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) is one of the presumed mechanisms of PARPi associated toxicity in cancer cells with HRD [59]. Using phosphorylated histone H2AX (yH2AX) as a marker for DSBs [59], we were interested in the effect of methylstat on olaparib induced DSBs. For this purpose, we used Olres-KB1P-G3 + BRCA1 cells with the lowest inherent PARPi response among our in vitro models, due to their BRCA1-proficient background and their experimentally acquired PARPi resistance (IC50 = 72 µM; Fig. 7A). Consistent with this phenotype, short-term treatment of 80 µM olaparib did not yet result in any detectable γ-H2AX signal. However, olaparib, combined with a low dose of the alkylating agent methyl methanesulfonate (MMS; 0.005%), lead to a moderate γ-H2AX induction, providing a cellular model of PARPi-associated DSBs (Fig. 7B). Interestingly, while methylstat alone did not have any effect on γ-H2AX, it potentiated olaparib/MMS induced γ-H2AX induction in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7A, B).

A Olaparib dose-response curves according to 6-day photometric viability assays of BRCA1-proficient KB1P murine breast cancer cells in comparison to their respective isogenic derivative cell lines with experimentally acquired PARPi-resistance. IC50 values are indicated according to non-linear regression analysis of normalized drug response. p-value levels were calculated according to nested t-test of dose-response curves. γH2AX response of (B) Olres-KB1P+BRCA1 cells and (C) paired Olres-UWB1.289/Olres-UWB1.289-JMJD1B/JMJD1C double knockout cells, treated with the indicated drug combinations. Representative Western Blot images including densitometric analysis from three independent biological replicates are shown. P-value levels were calculated according to one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Dunnet (B) or Šídák (C) correction. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

We moreover showed that Olres-UWB1.289 JMJD1B/JMJD1C double knockout cells were characterized by an inherently higher γ-H2AX response to combined olaparib/MMS treatment, compared to parental Olres-UWB1.289 cells. This indicates that the methylstat effect on DNA-damage response is likely mediated by the JMJD1B/JMJD1C demethylases (Fig. 7C).

Conclusively, we demonstrate that methylstat increases susceptibility to olaparib-induced DSBs in PARPi-resistant ovarian cancer cells with a BRCA1-proficient background.

Discussion

Understanding the cellular and genetic determinants of PARPi response is one of the key priorities for clinical translation. Consequently, there has been considerable interest for investigating the hallmarks of PARPi mechanisms via CRISPR screens in cells with diverse genetic backgrounds [15,16,17,18,19]. In our study, we leveraged a well-characterized model of human PARPi-resistant ovarian cancer [12] and conducted a CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening to systematically explore genetic determinants of PARPi response. Our screen has been conducted on a restricted set of genes, primarily chosen by their categorization into specific protein classes. However, we identified various hit genes for downstream analysis. Although our control scoring showed a high reliability, we cannot exclude that some PARPi-related genes remained undetected, because Cas9-mediated gene editing exhibits notable variability, contingent upon specific genomic target sites [52]. Additionally, our screen has demonstrated a relatively limited dynamic range, preventing a phenotypic ranking of these hit genes from the available dataset. Nevertheless, we have identified and orthogonally validated the histone demethylases JMJD1B/C as negative genetic regulators for PARPi response. Regarding clinical translation, we showed that JMJD1B/C targeting methylstat efficiently (re-)sensitized PARPi-resistant Olres-UWB1.289 cells to olaparib.

Exploiting collateral sensitivities of resistant cancer cells can be a useful strategy for designing targeted therapy approaches. In a preclinical study on breast cancer cells with acquired CDK4/6 inhibitor (CDK4/6i) resistance, authors discovered a collateral sensitivity towards the Wee-1 inhibitor adavosertib, which specifically depleted only CDK4/6i-resistant but not CDK4/6i-sensitive cells in a co-culture setting [60]. Consequently, combined treatment with CDK4/6i and adavosertib allowed tumor control by simultaneously targeting sensitive and resistant breast cancer cells [60]. In contrast, we show that methylstat alone had cytotoxic effects on both, PARPi-sensitive and PARPi-resistant ovarian cancer cells, while additionally potentiating the effect of olaparib among PARPi-resistant, PARPi-sensitive and BRCA1-proficient cell lines. This indicates that methylstat targets basic mechanisms of PARPi response, that are shared between PARPi-resistant and sensitive cells. Therefore, the effect of methylstat is not exclusively based on a selective vulnerability of PARPi-resistant cells.

Consistent with this finding, we demonstrated that methylstat increased susceptibility of DSB formation in ovarian cancer cells under olaparib treatment. Moreover, PARPi sensitization was particularly strong in cell lines with a BRCA1-proficient background, suggesting that methylstat promotes a pharmacologically induced state of HRD, also referred to as “BRCAness”, which results in synthetic lethality under olaparib treatment [61]. This hypothesis is partially corroborated by previous work, demonstrating that JMJD1C orchestrates chromatin response to DSBs and selectively promotes RAP80-BRCA1-mediated HR [62]. However, in this study, JMJD1C was shown to restrict the formation of RAD51 repair foci, and JMJD1C depletion caused resistance to ionizing radiation or PARPis. This is in contrast to our results could be attributed to the use of another cell line in this study (U2OS sarcoma cells), thus complicating a direct comparison between studies. Interestingly, the JMJD1C-mediated response to DSBs was supposed to result from JMJD1C-mediated demethylation of the non-histone protein MDC1 and not by the canonical histone DNA demethylation, suggesting that JMJD demethylases may control HR by a spectrum of non-canonical and yet unexplored target proteins [62,63,64]. Nevertheless, methylstat also sensitized ovarian cancer cell lines with a BRCA1-deficient background. JMJD1C/B are epigenetic regulators, that control a variety of biological functions in normal tissues and tumors [63] and their inhibition by methylstat likely interferes with additional cancer associated pathways and DNA-repair routes, awaiting further investigation. In acute myeloid leukemia, methylstat was reported to induce synergistic interactions with doxorubicin or the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib [65, 66]. This indicates divers and context-dependent phenotypes upon pharmacological inhibition of JMJD histone demethylases in cancer cells.

In the platinum-sensitive recurrent setting, the PARPis olaparib, niraparib and rucaparib can be clinically used as maintenance therapy in ovarian cancer patients, regardless of the HRD status. However, patients without BRCA1/2 mutations still have inferior response to PARPi, compared to patients with BRCA1/2 mutations [8,9,10,11]. Therefore, methylstat could be used for enhancing therapeutic efficacy of PARPi beyond BRCA1/2-deficiency. Furthermore, combined PARPi and methylstat treatment could be an ideal strategy for overcoming PARPi resistance in ovarian cancer. Lastly, we propose that methylstat could increase the efficacy of PARPi rechallenge in patients, which so far provided only modest PFS benefits [67].

We showed that high JMJD1B or JMJD1C expression indicates poor prognosis in ovarian cancer patients, which has also been reported for breast cancer patients [68] and therefore corroborates a pro-tumorigenic role of these epigenetic regulators. Moreover, combined genetic depletion of JMJD1C/B phenocopied the PARPi sensitizing effect of methylstat in an additive manner. Methylstat is a JMJD histone demethylases inhibitor, which is not entirely specific for JMJD1B/C [49]. It is possible that combined depletion of JMJD1B/C still does not phenocopy the full extent of the methylstat effect, since JMJD histone demethylases built a complex functional network in cancer [63]. Further members of this family, not targeted by our sgRNA library but inhibited by methylstat, may additionally contribute to PARPi resistance. Moreover, a contribution of histone demethylases beyond the JMJD family to PARPi resistance seems likely, because we showed that GSK-LSD1, targeting lysine specific demethylase 1 (LSD1), also provided a mild PARPi sensitizing effect. Pharmacological LSD1 inhibition has already been reported to confer anti-tumor activity in pre-clinical studies, to sensitize for chemotherapy, and to enhance anti-tumor immune response [69, 70]. Moreover, it has been investigated in a clinical trial on acute myeloid leukemia or lung cancer (NCT02177812, NCT02034123). Nevertheless, methylstat provided the most efficient PARPi sensitizing effect among all tested inhibitors of JMJD family and non-JMJD family members, potentially qualifying this drug for a preferred clinical use in ovarian cancer.

Conclusion

We propose that pharmacological targeting of the demethylase JMJD1B/C by the inhibitor methylstat sensitizes ovarian cancer cells to PARPi. Our findings are of high clinical-translational relevance, as they (i) provide a novel concept for increasing efficacy of PARPi inhibitors in ovarian cancer beyond HRD and (ii) pave the way for an alternative treatment option in patients with acquired PARPi resistance.

Responses