Molecular gene signature of circulating stromal/stem cells

Introduction

Stem cells are clonogenic cells with two remarkable features, the capability of differentiation into multiple mature cell types (multipotency), and replenishment of stem cell pool (self-renewal), that allow them to sustain tissue development and maintenance [1]. Notably, mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (MSCs) have been termed as diverse cell subpopulations of diverse precursor types, heterogeneous in nature and origin, that have been found in the stromal fraction of various adult organs and tissues [2,3,4]. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), the lineage committed cells can fabricate a spectrum of specialized mesenchymal tissues [5], mainly including bone, cartilage, muscle, marrow stroma, tendon, ligament, and fat [6,7,8], are one of the most intensively studied and best-characterized examples of tissue-specific somatic stem cells as a unique source for personalized regenerative therapy.

Besides the most generally defined bone marrow(BM)-derived MSCs [9, 10], increasing evidence suggests peripheral blood (PB) as an alternative source of stromal/stem cells for clinical application besides BM, including hematopoietic stem cells, endothelial progenitor cells and MSCs [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Our knowledge of circulating mesenchymal stem cells, in terms of definition, identity, origin, and function, has evolved over time [19,20,21,22]. To date, PB-derived circulating mesenchymal stem cells have been applied in various therapeutic applications preclinically and clinically [20, 23, 24].

The human skeleton is renewed and regenerated throughout life, by a cellular process known as bone remodeling that consists of cycles of resorption of old bone containing fatigue microfractures by osteoclastic cells, and its replacement with new bone with better biomechanical properties by osteoblastic cells [25]. Under steady state, adult stem cells patrol within peripheral circulation at a very low frequency [26, 27]. However, circulating cell pools of adult stromal/stem cells (also termed as ‘activating or priming MSCs’) within peripheral blood would consistently and dramatically increase upon certain conditions, such as hypoxia, injury signals, or cytokines, or inflammatory cytokines [27,28,29,30].

Results

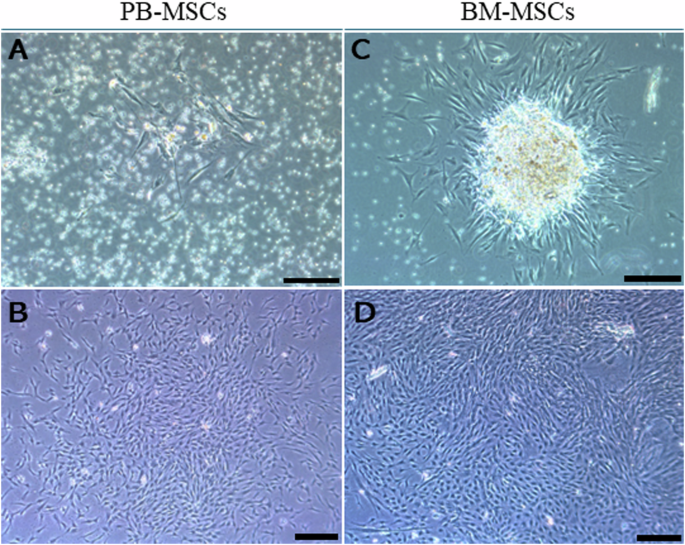

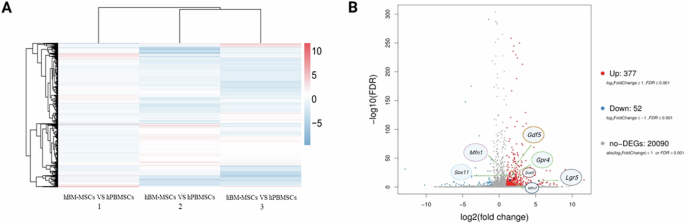

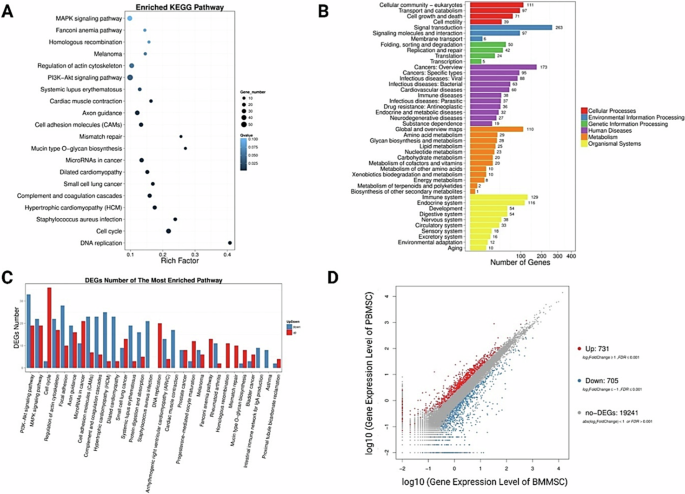

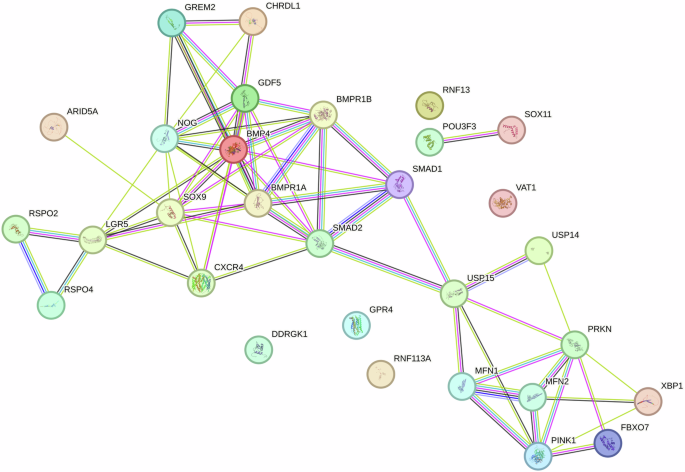

Generally, stem cells within peripheral blood have been regarded activated stem cells with enhanced cell motility and differentiation capacity following stem cell mobilization [31, 32]. Circulating mesenchymal stem cells (PB-MSCs) and bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) both exhibited spindle shape and colony-forming capacity (Fig. 1). Circulating mesenchymal stem cells have been demonstrated to possess distinct gene expression profiling (Fig. 2A) and surface antigen expression compared from the counterparts from bone marrow [20]. Interestingly, a variety of upregulated genes have been identified in circulating PB-MSCs compared with BM-MSCs, mainly including GDF5, SOX11, LGR5, GPR4, MFN1 and MFN2 (Fig. 2B). During this process, various key molecules and signaling pathways have been identified involved (Fig. 2 & Fig. 3). To explore the underlying genetic interactions that regulate cellular function and molecular phenotypes of circulating MSCs, proposed genetic interactions between these key genes have been identified based on STRING database as potential clues for further biological discovery and therapeutic optimization (Fig. 4), which requires further experimental validation.

Cell morphology observation of human peripheral blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells (PB-MSCs), and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs). A, C Day 3 after cell seeding; (B, D) 1 week after seeding

Specific gene expression profiling and molecular gene signatures of circulating mesenchymal stem cells. A Heatmap analysis result suggests differential gene expression profiling between hBM-MSCs and hPB-MSCs. Genome-wide RNA sequencing by RNA-seq analysis indicated differently expressed genes between hBM-MSCs and hPB-MSCs from one certain donor (n = 3). B Upregulated expression of genes (e.g., Sox9, Sox11, Lgr5, Gdf5, Gpr4, Mfn1, Mfn2) identified as unique molecular signatures of circulating mesenchymal stem cells

Identification of differential gene expression and signaling pathways associated with different cellular functions involved in a variety of cellular processes. A Differential signaling pathways in circulating mesenchymal stem cells compared to bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. B Number of differentially expressed genes involved in various cellular processes and functions. C DEGs numbers of the most enriched pathways. D 731 upregulated genes and 705 downregulated genes identified in circulating mesenchymal stem cells compared with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

Schematic illustration of genetic interactions to identify functional association between key genes governing cellular function and molecular phenotype

Growth and differentiation factor 5 (GDF-5), a member of the BMP family [33], has been recently identified as an important factor for skeletal development [34], and regeneration [35], chondrogenesis [36, 37], and increased cell migration and motility [38]. GPR4, a proton-sensing G protein-coupled receptor, has been reported as an essential regulator of cell adhesion [39], pH homeostasis [40], and intracellular Ca2+ mobilization [41].

In mammals, MFN2 (mitofusin-2), also forms complexes that are capable of tethering mitochondria to endoplasmic reticulum (ER), a structural feature essential for mitochondrial energy metabolism, thereby enhancing intra-cellular calcium buffering [42, 43]. Notably, the gene expression of MFN2 (mitofusin-2) is also found elevated in circulating mesenchymal stem cells. Nfat, Calcium buffering, and ER-Mfn2 are critical for the property maintenance of HSC with extensive lymphoid potential [42]. Thus, MFN2 may probably associate with inflammatory signaling and play essential roles for regulation of phenotypes of adult stem cells, as well as potential key factors for metabolic regulation during the switch between quiescence and activation of adult stem cells.

‘Pioneer’ transcription factors are essential for stem-cell pluripotency, cell differentiation and cell reprogramming [44, 45]. The transcription factor SOX11 (SRY-related high-mobility-group (HMG) box 11), a member of the SOXC group, is expressed during embryogenesis but largely absent in most adult differentiated tissues. SOX11 regulates progenitor and stem cell behavior, and often acts together with the other two SOXC group members, SOX4 and SOX12, especially in developmental processes, including neurogenesis and skeleton-genesis [46]. SOX11 regulates MSC osteogenesis and migration via activation activate runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) and CXC chemokine receptor-4 (CXCR4) expression [47]. Also, Wnt7b has been demonstrated to activate the Ca2+-dependent Nfatc1 signaling to directly induce Sox11 transcription, which in turn activates the transcriptions of both proliferation-related transcription factors (CCNB1 and SOX2) and osteogenesis-related factors (RUNX2, SP7) in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells [48]. For efficient chromatin opening, SOX factors cooperate with other transcription factors such as OCT4, KLF4, PAX6, Nanog, BRN2, and PRX11, involved in cell fate regulation [49]. And recent breakthroughs uncovered nucleosome–SOX11 structure, which further shows that binding of SOX11 repositions the N-terminal tail of H4, indicating that SOX11 in essential for chromatin dynamics and accessibility [50]. The transcription factor sex-determining region Y (SRY)-box 9 protein (SOX9) is a member of the SOX family. During embryogenesis, SOX9 is expressed in all osteochondroprogenitor cells and differentiated chondrocytes. In addition to being crucial for mesenchymal condensation and osteochondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) during embryonic skeletal growth, SOX9 also plays a crucial role in cellular metabolic activities, i.e. cell proliferation and cell survival [51, 52] Therefore, SOX11 and SOX9 are critically involved in cell survival, cell fact control and stem cell activation.

Leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein–coupled receptor 5 (LGR5), a Wnt target gene, modulates Wnt signalling strength through binding to its ligand R-spondin [53]. LGR5 is a molecular marker of self-renewing multipotent adult stem cell populations in multiple organs, including the gut, stomach, hair follicle, mammary gland, kidney, muscle, and ovary [54, 55]. Previous studies have demonstrated the increased expression of LGR5 in peripheral blood-derived circulating mesenchymal stem cells comparing to BM-MSCs [14], which is essential for osteogenic differentiation of MSCs [56]. Thus, LGR5 may serve as a sensitive surface biomarker of stem cell activation and mobilization.

GPR4 is a proton-sensing GPCR (pH sensor) that might also sense amino acids, pointing to its role in many intracellular signaling pathways [57, 58]. Alterations in extracellular pH have been reported to induce quiescence of stem cells, as lowering of pH favors quiescence of glioblastoma stem-like cells through the remodeling of Ca2+ signaling [59]. Importantly, microenvironment pH has been well-documented essential for immunomodulation, cell activation, differentiation, and tissue regeneration [60,61,62,63,64,65,66]. Thus, GPR4 may induce activation and mobilization of MSCs in response to alterations of extracellular pH around the niche.

Conclusions

Therefore, circulating MSCs are mobile progenitor/stromal cells with specific gene signatures and enhanced mitochondrial turnover and remodeling, as well as elevated expression of LGR5 and SOX11. A global LGR5-associated genetic interaction network highlights the functional organization of circulating MSCs that discovered in this current study, as well as molecular network in articular cartilage with subchondral bone and synovium of the whole knee joint reported in a recent breakthrough [67], providing potential insights into the intricate biochemical machinery that operates within cells that are essential for tissue homeostasis, signal transduction following tissue injury, pathogenesis, and potential molecular diagnostic biomarker.

Integrated with genome editing technology and standardized current good manufacturing practice (cGMP) compliant conditions (including tissue sourcing, manufacturing, testing, and storage) for optimization of cell property maintenance during ex vivo cell enrichment and cell delivery following transplantation, circulating MSCs-based therapy may serve as a promising personalized strategy for curing a broad spectrum of diseases [68, 69]. Future studies on cytoskeleton architecture, mitochondrial activity and function (oxygen consumption rate, ATP production levels, and mitochondrial membrane potential) of freshly isolated MSCs from different sources deserve further exploitation.

Methods

Cell culture

Peripheral blood and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells were isolated and cultured following previously established protocols [14]. The collection process of peripheral blood and marrow liquid (from 9-year-old female fracture donor, 11-year-old male fracture donor, and 80-year-old female fracture donor experiencing micro-fracture surgery) was approved by the Clinical Research and Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong or Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine. Passage 0 cells (one week after cell seeding) were studied in this current research.

Whole genome-wide RNA sequencing (RNAseq) analysis

Freshly enriched cells (Passage 0) were subjected to RNAseq analysis. TRIzol (Life Technologies, USA) was used for extraction of total RNA from the caput, cauda and corpus of the epididymis. RNA sample quality and quantity were assessed using Nanodrop, agarose gel electrophoresis, and Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent, USA). DNA library preparation was performed using NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). Sequencing was performed on the Illumina Hiseq X Ten at 150 bp paired end reads with 20 M read depth. All samples had Q30 >90%. Both library preparation and sequencing were performed by

BGISEQ-500 platform (Shenzhen Huada Gene Technology Co., Ltd., China). Differential gene analysis was applied via the HISAT2-Cufflinks workflow. Gene ontology enrichment analysis and visualization were performed in http://cbl-gorilla.cs.technion.ac.il/. The online data analysis tool Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) (Qiagen) was used for genes that had a P value of <0.05 and a ≥twofold change (FC) difference between BM-MSCs and PB-MSCs. Core analysis was run on dataset to screen differential expressed genes and signaling pathways between different source-derived cells.

Responses