Molecular mechanism of culinary herb Artemisia argyi in promoting lifespan and stress tolerance

Results

Effects of AALE on lifespan, body size, motility, and lipofuscin of C. elegans

A total of 22 flavonoid compounds were identified in AALE. Among them, the major flavonoids were kaempferol, L-epicatechin, apigenin, catechin, quercetin, luteolin, formononetin, and naringenin (Table 1). These flavonoids could provide health-promoting activity individually or synergistically. However, the effects and mechanism of Artemisia argyi on these health benefits have not been well understood.

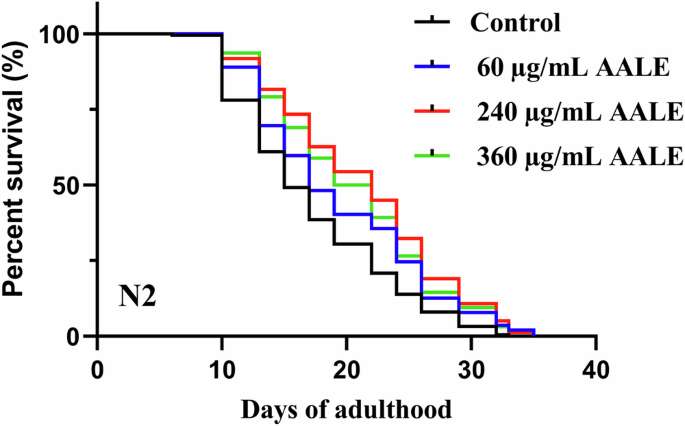

The survival curves of C. elegans (wild-type N2 worms) in control and treated with different concentrations are shown in Fig. 1. The mean lifespan of each treatment group was significantly higher than control (Table 2), while the survival rate of C. elegans in the treatment group with 240 μg/mL was the highest after two weeks. The C. elegans with AALE at 60, 240, and 360 μg/mL treatments significantly prolonged the mean lifespan by 12.06% (p-value 0.0013), 23.19% (p < 0.0001), and 19.07% (p < 0.0001), respectively. Compared with a similar study of evaluating flavonoids-rich mung bean coat extract, AALE had higher lifespan, especially at lower dosage16. However, the mean lifespans of 240 and 360 μg/mL were not significantly different. It indicated that there might be an optimal range of dosage for AALE in extending the lifespan.

Effects of AALE on the lifespan of C. elegans exposed to AALE at 0, 60, 240, and 360 μg/mL. *The log-rank (Kaplan–Meier) test was utilized for statistical analysis.

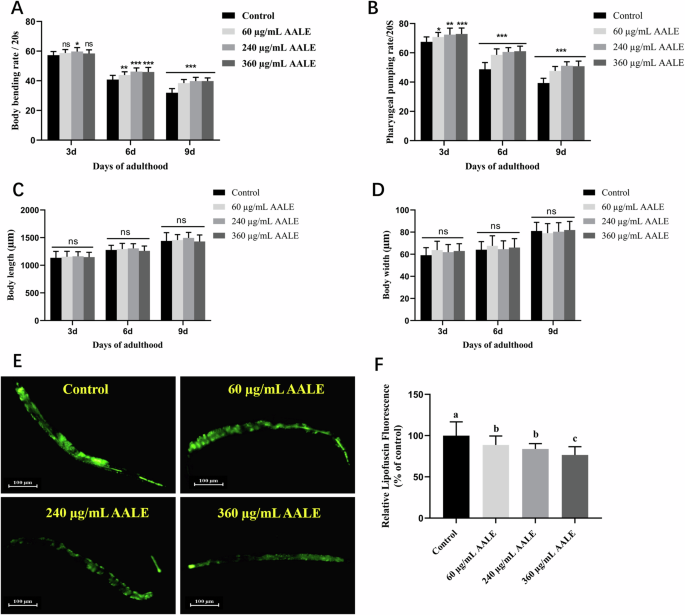

The fitness indices including (A) body bending rates, (B) pharyngeal pumping rates, (C) body length and (D) body width of C. elegans in the control and treatment groups are shown in Fig. 2. As illustrated in Fig. 2A, B, AALE-treated worms exhibited significantly higher levels of both body bending and pharyngeal pumping in comparison to the control at each tested stage. Meanwhile there were no significant differences in the body length and body width between AALE-treated worms and control worms (Fig. 2C, D). It suggested that AALE improved the motility of C. elegans without change of its body size. The change of body size of C. elegans is usually associated with the toxicity in their diets17.

A Body bending rates, (B) Pharyngeal pumping rates, (C) Body length, and (D) Body width of N2 worms treated with 60, 240, 360 μg/mL AALE or control on the days 3, 6, 9 of adulthood. E Images of intestinal autofluorescence from lipofuscin of worms on the day 10 of adulthood. F Relative fluorescence intensity of lipofuscin. *The images were analyzed with ImageJ software and numerical data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA. Data were represented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. ns., no significance.

AALE treatment significantly declined the lipofuscin accumulation level of worms by 11.31%, 16.18%, and 23.38% at doses of 60, 240, 360 μg/mL, respectively (Fig. 2E, F). The reduction of lipofuscin accumulation delays the aging process of C. elegans18. These results demonstrated AALE significantly prolonged the youthfulness and promoted healthiness in aging of C. elegans.

AALE enhanced the stress resistance of C. elegans

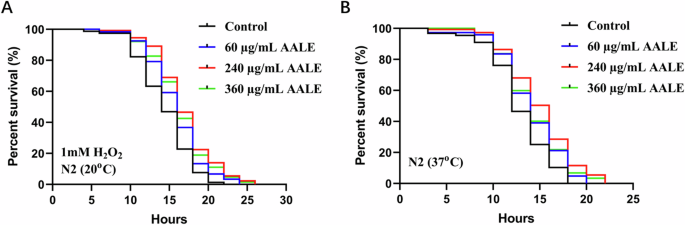

As shown in Fig. 3A, AALE treatments prolonged the lifespan of worms under oxidative stress induced by 1 mM hydrogen peroxide (p < 0.01) with increases of mean lifespan by 9.76%, 17.35%, and 13.80% at concentrations of 60, 240, and 360 μg/mL, respectively. In the thermo-resistance at 37 °C, the mean lifespans of worms treated with 60, 240, and 360 μg/mL of AALE were increased by 8.84%, 16.65%, and 11.26%, respectively (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3B, Table S2). Similar to the survival rates without induced stress (Fig. 1), the survival rate of worm treated with 240 μg/mL of AALE was the highest, while the rate of worm treated with 360 μg/mL of AALE which was the highest dosage used in this study was the second among the four group. Therefore, based on the results of assays, concentration of 240 μg/mL AALE was selected and used in the subsequent experiments.

A Survival curves of N2 nematodes under oxidative stress. B Survival curves of the N2 nematodes under thermal stress.*Survival rates were analyzed by the log-rank (Kaplan–Meier) test using GraphPad Prism 9.0.

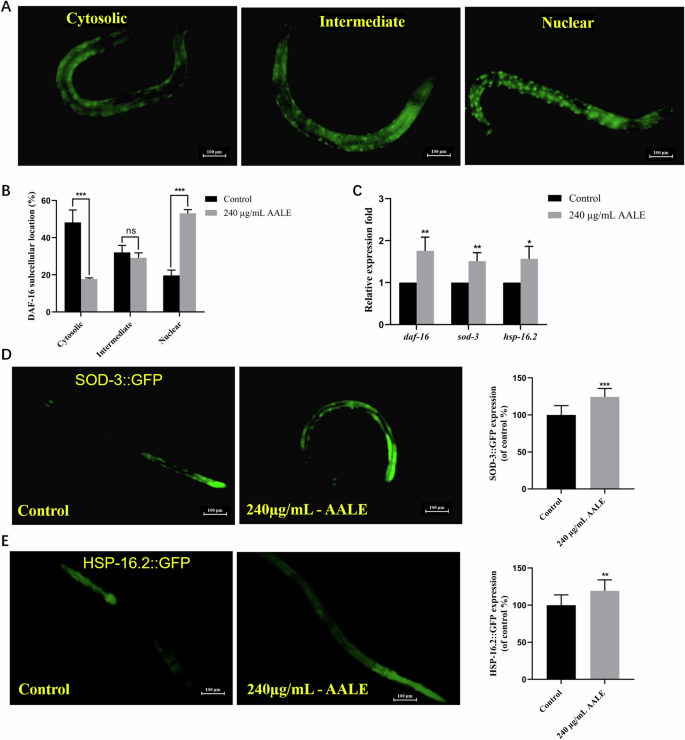

AALE prolonged lifespan by activating transcription factor DAF-16/FOXO

The mammalian FOXO (Forkhead box O transcription factor) orthologue DAF-16 was reported to mediate longevity, lipogenesis, heat shock survival and oxidative stress responses in C. elegans19. The nuclear localizations of DAF-16 in TJ356 strains treated with and without AALE were examined. The nuclear proportion of DAF-16 was enhanced from 19.69% to 53.13% (p < 0.001), while the fraction in cytoplasm declined from 48.21% to 17.71% (p < 0.001) after the strain treated with 240 μg/mL AALE compared with the strain in control group (Fig. 4A, B). The mRNA expression levels of daf-16 and its downstream target genes, sod-3 (superoxide dismutase) and hsp-16.2 (heat shock protein), were obviously up-regulated in AALE- treated worms (Fig. 4C, p < 0.05). In C. elegans, the heat shock proteins (HSPs) are closely associated with thermo-tolerance and can serve as a biomarker of aging20. It is in agreement with our results that AALE-treated worms exhibited higher fluorescence intensity of HSP-16.2::GFP than that in control group. The expression levels of SOD-3::GFP and HSP-16.2::GFP were significantly improved by 24.37% and 19.31% in CF1553 and CL2070 strains treated with AALE, respectively (Fig. 4D, E, p < 0.01). Therefore, it indicated that the AALE-mediated longevity promotion was also dependent on the activation of DAF-16.

A Distribution of DAF-16::GFP in TJ356: cytosolic, intermediate, and nuclear(fluorescence images of DAF-16::GFP expression in AALE-treated and untreated TJ356 strains were present in figure S1). B Quantification of DAF-16::GFP location. C The mRNA expression of daf-16 and its downstream genes. D The images and quantification of fluorescence intensity in CF1553 strain. E The images and quantification of fluorescence intensity in CL2070 strain. Data were represented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 by student’s t-test. ns. no significance.

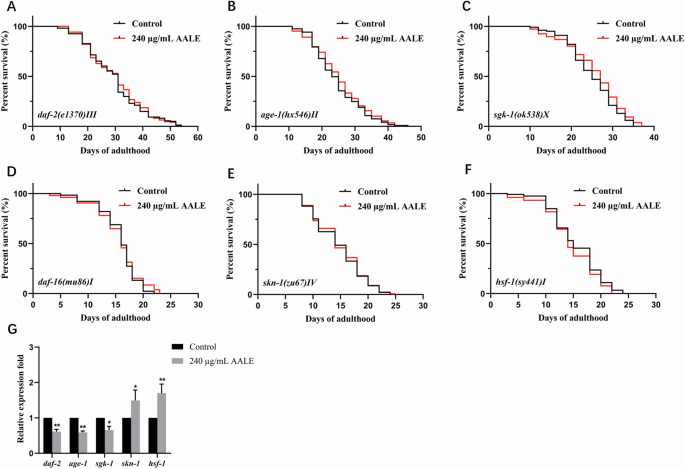

AALE-induced longevity was dependent on IIS pathway

Considering that AALE extended the lifespan by activating DAF-16 which is a central transcription factor of IIS pathway, AALE might extend the lifespan through the IIS pathway21. Our study showed that AALE failed to extend the lifespans of the loss of function mutants including daf-2, age-1, sgk-1, daf-16, skn-1, and hsf-1 mutants (Fig. 5A–F, Table S3, p > 0.05). It was confirmed that the IIS pathway was crucial to AALE-mediated lifespan for C. elegans. Furthermore, AALE significantly downregulated the expressions of daf-2, age-1, and sgk-1, while upregulated the expressions of skn-1 and hsf-1(Fig. 5G, p < 0.05). Therefore, AALE extended the lifespan of C. elegans by regulating the IIS pathway and activating DAF-16/FOXO. This is consistent with a previous finding that flavonoid-rich Gastrodia elata extract extended lifespan and reduced oxidative stress by regulating the IIS pathway as well22.

Survival curves of (A) daf-2 (e1370) mutants, (B) age-1(hx546) mutants, (C) sgk-1 (ok538) mutants, (D) daf-16(mu86) mutants, (E) skn-1(zu67) mutants, and (F) hsf-1 (sy441) mutants treated with 240 μg/mL AALE and control. G The mRNA expression of daf-2, age-1, sgk-1, skn-1 and hsf-1. *Survival rates were analyzed by the log-rank (Kaplan–Meier) test using GraphPad Prism 9.0.

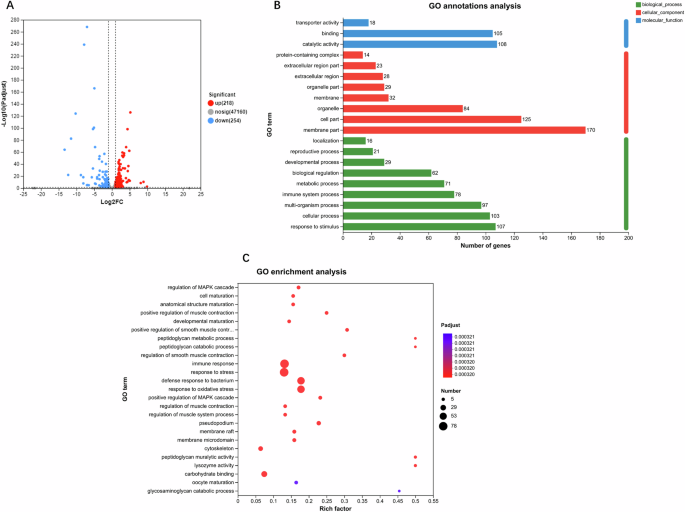

Differential expressed genes identification and functional distribution

RNA-sequencing analysis was conducted on the 3rd day of N2 worms treated with or without AALE. As shown in Fig. 6A, there were 218 upregulated and 254 downregulated genes based on the criteria of fold change ≥ 2 and p ≤ 0.05. Moreover, annotations and enrichment of GO (gene ontology) pathway were analyzed based on the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of AALE-treated worms. The results showed that molecular functions primarily include transporter activity, binding, and catalytic activity. The cellular components mainly consist of membrane part, cell part, organelle, membrane, and extracellular regions. The biological processes primarily involved in response to stimulus, cellular process, multi-organism process, immune system process, metabolic process, biological regulation, and developmental process (Fig. 6B). The GO enrichment analysis of DEGs was conducted by Goatools and the enrichment results of top 25 are shown according to the degree of significance (Fig. 6C, p < 0.05). It exhibited that the DEGs in AALE-treated worms were mainly enriched in regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade. The MAPK cascade includes the responses to oxidative stress, cell maturation, developmental maturation, immune reaction, and stress. All of them involve in the regulation of aging, stress resistance, and development of C. elegans. In C. elegans, MAPK cascade regulates cellular adaptive response to environmental changes and SKN-1 has been considered as a key factor for the p38 MAPK pathway to exert stress-resistance function23. It was found that AALE failed to extend the lifespan of skn-1 null mutants, suggesting that the lifespan extension effect of AALE also relied on skn-1.

A differential expression volcano plot – the blue dots represent downregulated differentially expressed genes, red dots represent upregulated differentially expressed genes, and gray dots represent genes with no change, (B) GO annotations analysis of differentially expressed genes – the horizontal coordinate is the number of genes, and the vertical coordinate is the GO classification, and (C) GO enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes – the horizontal coordinate is the ratio of the genes of interest annotated in the entry to the number of all differentially expressed genes and the vertical coordinate is each GO annotation entry. The size of the dots represents the number of differentially expressed genes in the GO annotation entry, and the color of the dots represents the p-adjust of the hypergeometric test.

In summary, the above results further confirmed that AALE promoted longevity mainly by regulating the MAPK pathway. It was further supported the capability of AALE in enhancing lifespan, healthy aging, and stress resistance of C. elegans by the molecular genetic results.

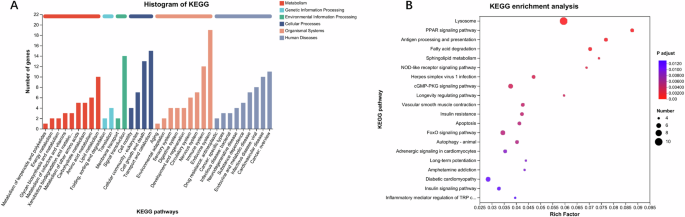

KEGG analysis and validation of DEGs

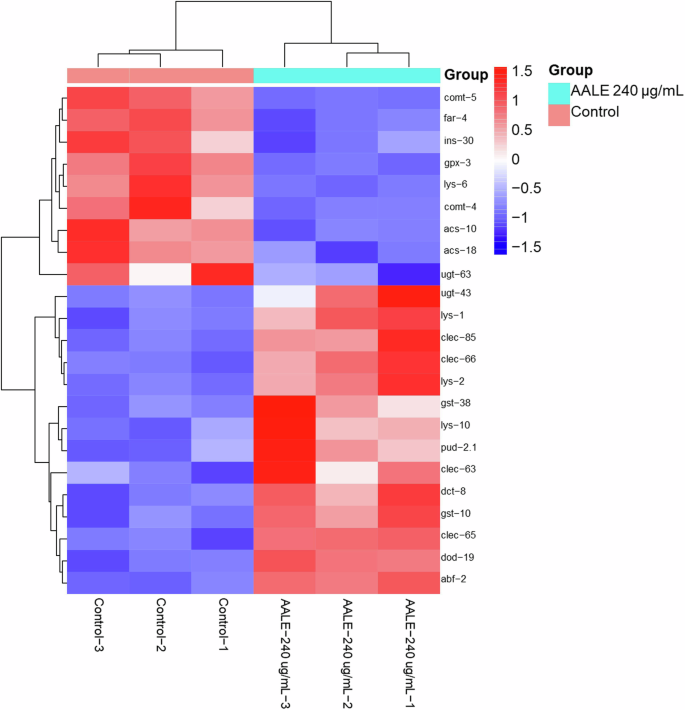

To systematically analyze gene function and explore the relationship between genomic information and functional information, KEGG function annotation was performed on DEGs. The results showed that DEGs of AALE-treated worms were mainly related to lipid and amino acid metabolism, signal transduction, transport and catabolism, aging, nervous and immune system, neurodegenerative disease, and cancer (Fig. 7A). The related representative DEGs were summarized in a heatmap format (Fig. 8). Furthermore, the results of KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that DEGs were mainly enriched in the lysosome, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) signaling pathway, fatty acid degradation, longevity regulation pathway, FOXO signaling pathway, autophagy, and insulin resistance (Fig. 7B). The results were in accordance with that AALE activated the DAF-16 and regulated the IIS pathway.

A KEGG functional annotations of differentially expressed genes – the horizontal coordinate is the name of the KEGG annotations classification, and the vertical coordinate is the number of genes, (B) KEGG enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes – the horizontal coordinate is the ratio of the genes of interest annotated in the entry to the number of all differentially expressed genes, and the vertical coordinate is each KEGG pathway – the size of the dots represents the number of differentially expressed genes annotated in the pathway, and the color of the dots represents the p-adjust of the hypergeometric test.

Heat map illustrates the differential gene expression profile with horizontal axis representing samples and vertical axis representing genes. Colors indicate varying expression levels, progressing from blue (low expression) through white to red (high expression), where red means high expression genes and dark blue represents low-expression genes.

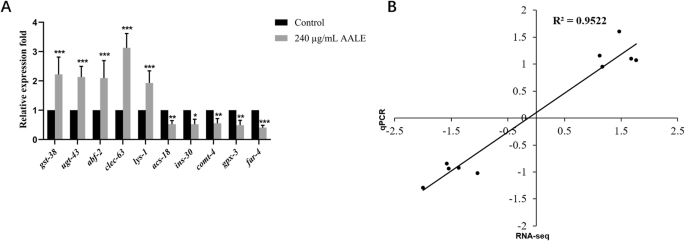

The GO and KEGG enrichment analysis aforementioned revealed that DEGs mainly involved in lipid and amino acid metabolism, signal transduction, aging, immune reaction, stress resistance, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) signaling pathway, fatty acid degradation, longevity regulation pathway. Thus, ten differentially expressed genes related to antioxidant response, antimicrobial activity, immune response, locomotory behaviors, insulin secretion and fatty acid metabolism were selected to measure their expression levels by qPCR to support the RNA-seq results. The results showed that AALE significantly increased the expressions of gst-38 (Glutathione S-Transferase), ugt-43 (UDP-Glucuronosyl Transferase), abf-2 (Antibacterial factor-related peptide 2), clec-63 (C-type LECtin), and lys-1(Lysozyme-like protein 1) (Fig. 9A, p < 0.05). AALE decreased the expressions of acs-18 (AMP-binding domain-containing protein), ins-30 (INSulin related), comt-4 (Catechol-O-Methyl Transferase family), gpx-3 (Glutathione peroxidase 3), and far-4 (Fatty Acid/Retinol binding protein) (Fig. 9A, p < 0.05). These findings were in agreement with the RNA-seq results. Moreover, the results showed that the correlation coefficient (R2) between the log2FC values of qRT-PCR and those of RNA-sequencing results was 0.95, which verified the reliability of RNA sequencing data (Fig. 9B).

A The mRNA expression of several differentially expressed genes. Data were represented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 by student’s t-test. B Correlation analysis of qRT-PCR log2FoldChange results and RNA-sequencing data log2FoldChange of selected 10 DE mRNAs.

Discussion

Several studies reported that Artemisia argyi demonstrates a variety of beneficial bioactivities, including antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotection activities due to its abundant flavonoids24,25,26. However, the effects of Artemisia argyi on the health-promoting and longevity promotion have been rarely reported. Herein, a genetic system of C. elegans was established to evaluate the longevity-promoting effect of AALE. Our results suggested that AALE, rich in flavonoids, significantly extended the lifespan and promoted the health of C. elegans accompanied by the prevention of age-associated declines of body bending and pharyngeal pumping rates as well as reduced lipofuscin accumulation.

In C. elegans, their low resistance against external stress sharply declines their lifespan27. Most of the observed lifespan extension phenotypes are associated with increased stress resistance such as thermal and oxidative stresses28. In the current study, AALE was found to significantly promote oxidative stress resistance. Meanwhile, AALE effectively upregulated the expression of antioxidant enzymes sod-3 as well as SOD-3::GFP, which is consistent with a previous report where AALE exhibited high DPPH scavenging ability29. Besides, AALE also increased the survival rate of worms under thermal stress condition. In C. elegans, the heat shock proteins (HSPs) are thought to be closely associated with thermotolerance and can serve as a biomarker of aging20,30. This was supported by the observation that AALE-treated worms exhibited higher fluorescence intensity of HSP-16.2::GFP than the control group. Taken together, it is conceivable that the protective effect under stress may confer the lifespan extension effect of AALE.

It is well-known that the insulin/IGF-1 signaling (IIS) pathway is highly conserved and involved in metabolism, growth, development and longevity31. In C. elegans, the insulin-like receptor DAF-2 signals through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt kinase pathway to culminate the regulation of DAF-16/FOXO, which governs most of the functions of this pathway32. According to our results, AALE induced translocation of DAF-16 protein from cytoplasm to nucleus and increased the expression of daf-16, suggesting that AALE activated the function of DAF-16. This was supported by the fact that AALE significantly upregulated the expression of its downstream genes, sod-3 and hsp-16.2. Besides, the results showed that the loss of function mutants daf-2(e1370)III, age-1(hx546)II, sgk-1(ok538)X, daf-16 (mu86)I, skn-1 (zu67)IV, and hsf-1 (sy441)I suppressed the effect of AALE on lifespan extension, indicating that the longevity promotion effect of AALE was depended on the IIS pathway. Taken together, these results demonstrated that AALE extended the lifespan of C. elegans by regulating the IIS pathway and activating DAF-16/FOXO.

To thoroughly clarify the mechanism of AALE-induced healthspan and lifespan extension, the RNA-sequencing method was employed. The results showed that there were 218 upregulated and 254 downregulated genes in AALE-treated worms. In C. elegans, gst-38 and ugt-43 are related to glutathione metabolism and phase II detoxification, respectively33,34. In C. elegans, gst-38 and ugt-43 are related to glutathione metabolism and phase II detoxification, respectively33. Thus, AALE significantly upregulated the expression of gst-38 and ugt-43 to enhance the anti-oxidant activity and oxidative stress resistance of worms. The genes lys-1, abf-2, and clec-63 which were remarkably upregulated in AALE-treated worms contribute to the antimicrobial activity and immune response as well35,36. A previous study suggested that Artemisia argyi exerted antimicrobial effect in goldfish and Candida albicans models37. However, the results of antimicrobial experiments showed that AALE had no toxic effect on the growth of E. coli OP50 at concentrations of 60, 240, 360 μg/mL (Fig. S2). It suggested that that the levels of AALE used in this study had no influence on the growth of E. coli OP50. Our results showed that AALE significantly downregulated comt-4, which might be beneficial to the enhancement of the body bending and pharyngeal pumping rates in AALE-treated worms. Similar to the results, it was reported that inhibition of comt-4 could decrease the dopamine levels and promote locomotory behaviors of nematodes38. Moreover, the significantly decreased expressions of ins-3, acs-18, and far-4 by AALE were associated with insulin secretion and fatty acid metabolism39. Based on the results, it was suggested that AALE may mediate glycolipid metabolism in nematodes by influencing the activity of key metabolic enzymes and synthesis, catabolism, and oxidation of fatty acids.

Our current results suggested that AALE acted through multiple targets in extending lifespan and well-being, which involved its various biological functions including antioxidant, immunomodulatory, antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties. Thus, Artemisia argyi has great potential to become a new natural source for treating the age-related diseases and prolonging healthy lifespan.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

5-Fluoro-2-deoxyuridine (FUdR 98%) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A). The strains used in this study including N2, EU1 skn-1 (zu67) IV, CF1038 daf-16 (mu86) I, VC345 sgk-1(ok538)X, TJ1052 age-1(hx546)II, CB1370 daf-2(e1370)III, PS3551 hsf-1(sy441) I, CL2070 (dvIs70 [hsp-16.2p::GFP + rol-6(su1006)]), TJ356 (zIs356IV[daf-16p::daf-16a/b::GFP+rol-6(su1006)]), and CF1553 (muIs84 [(pAD76)sod-3p::GFP+ rol-6(su1006)]) were purchased from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center at the University of Minnesota (MN, USA). Artemisia argyi (Qiyou No.1) leaves were obtained from Qichun Qiaikang Material Medical Technology Co., Ltd (Hubei, China). The accession number of Artemisia argyi was Hubei Tasting Medicine 2023-003.

Preparation of AALE

Artemisia argyi Lévl. leaf extract (AALE) was prepared according to a previous method40. Dried Artemisia argyi leaves were extracted twice with 50% ethanol at 50 °C for 2 h. After evaporating the solvent, the extract was loaded onto a column packed with resin AB-8 (Yuan Ye Biological Technology Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China) for further purification. The eluted fraction with 50% ethanol was collected and then concentrated and lyophilized to obtain final dried AALE. The AALE was dissolved in DMSO to obtain an AALE stock solution at concentration of 60 mg/mL and stored at −80 °C.

Identification and quantification of major flavonoids in AALE using HPLC-MS/MS

AALE was analyzed by an HPLC system with a column (HSS T3 C18, pore size 1.8 μm, length 2.1 × 100 mm). Mobile phase A and B were 0.04% acetic acid and acetonitrile with 0.04% acetic acid, respectively. The gradient program of mobile phase was 5% B at 0 min, ramped 95% B in 12.0 min and maintained 5% B from 12.1 min to 15.0 min with a constant flowrate of 0.35 mL/min. The Full-Scan mode by Q Exactive Focus Orbitrap LC-MS/MS (Thermo Scientific, USA) was applied. The ESI source operation parameters were as follows: nebulizing gas flow, 3 L/min; heating gas flow, 10 L/min; interface temperature, 550 °C; DL temperature, 250 °C; heat block temperature, 400 °C; drying gas flow, 10 L/min. Parent ions and base fragment ions were used to carry out identification and quantification.

Worm maintenance, lifespan, body size, motility, lipofuscin, and stress resistance assays

The C. elegans strains used in this work were raised on NGM (nematode growth medium) plates seeded with E. coli OP50 for a spawning period at 20 °C. Age-synchronized nematodes were obtained by hypochlorite–sodium hydroxide bleaching and then cultured in M9 buffer at 20 °C. The lifespan assays were conducted according to the methods previously described41. All lifespan assays were carried out at 20 °C. Age-synchronized L4 larvae were transferred to a new 96-well plate (10–15 worms per well) containing liquid S-completed medium treated with 0.6% DMSO (control) or the appropriate doses of AALE (60, 240, and 360 μg/mL). FUdR (150 μM) was also added to inhibit the growth of progeny. The survival rates of worms were recorded every other day until all worms died. Furthermore, the effects of AALE on the growth of E. coli OP50 were conducted as follows. The absorbances of culture solutions containing E. coli OP50 and AALE were determined at 600 nm.

Worms were cultured as outlined above. On the 3, 6, and 9 day of adulthood, the body size, pharyngeal pumping rates, and body bending rates of worms were determined according to our previous report42. For lipofuscin determination, on the 10th day of adulthood, the worms were paralyzed with sodium azide (2%) and photographed by a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan) with excitation and emission wavelengths at 485 nm and 528 nm, respectively. The fluorescence intensity of each worm was quantified using ImageJ software.

For oxidative stress assay, the day 7 adult worms were transferred to a fresh 96-well plate containing 1 mM hydrogen peroxide and incubated at 20 °C43. For the thermal stress assay, the worms were transferred to a pre-heated 96-well plate on the 7th day of adulthood and then subjected to the heat stress at 37 °C43. The survivals were recorded every 2 h until all the worms died.

DAF-16::GFP subcellular localization assay

Synchronized L4 larvae of strain TJ356 (a GFP reporter for DAF-16) were treated with 240 μg/mL AALE or 0.6% DMSO for 1 h, and then observed and photographed using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan). “cytosolic”, “intermediate” and “nuclear” were utilized to identify the expression patterns of DAF-16::GFP44,45. The worms were counted and analyzed to express as percentages in each group.

Fluorescence measurements in transgenic strains

Age-synchronized L1 larvae of CF1553 (SOD-3 fused GFP protein) were cultured with AALE (240 μg/mL) or 0.6% DMSO for 72 h. The worms were anesthetized with 2% sodium azide and imaged with a fluorescence microscope46. Prior to microscopy observation, the young adult mutants of CL2070 (HSP-16.2 fused GFP protein) were exposed to heat shock at 37 °C for 2 h and allowed to recover at 20 °C for 4 h47. The GFP fluorescence intensity per worm was analyzed by ImageJ software.

RNA sequencing analysis

Worms were collected on the 3rd day of adulthood and washed with M9 buffer to remove E. coli OP50. RNA sequencing experiment was performed through Majorbio BioTech Co. (Shanghai, China) using the Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform following the manufacturer’s recommendations48. One μg of RNA per sample was used as input material for the RNA sample preparation. The reference genome used for analysis was as follows (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/taxonomy/6239). Transcripts with an adjusted p value ≤ 0.05 and fold change ≥ 2 were considered significantly differential expression.

Gene expression analysis by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Age-synchronized L4 larvae of wild-type worms were treated with or without 240 μg/mL AALE for 72 h at 20 °C. Total RNA was extracted according to the standard protocols (Tiangen Biotech, China) and converted to cDNA using reverse transcription kit (Vazyme Biotech, China). Afterwards, the qRT-PCR reaction was carried out in a QuantStudio 3.0 PCR system (ABI, USA) along with SYBR Green PCR PreMix (Tiangen Biotech, China). Actin-1 was chosen as reference gene and gene expression was analyzed using the 2-ΔΔCT method.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted utilizing Graph Pad Prism version 9.0 (San Diego, CA, U.S.A) and SPSS 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Statistical significance was evaluated by ANOVA or t-tests, and significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Responses