Motor cortex stimulation ameliorates parkinsonian locomotor deficits: effectual and mechanistic differences from subthalamic modulation

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disease ascribable to dopaminergic neuron loss1,2,3. Clinically, PD is primarily characterized by apparent movement disorders, including both hypokinetic (e.g. akinetic rigidity) and hyperkinetic (e.g. tremor/propulsion) symptoms as the classic nomenclature “paralysis agitans” has already implicated. Electrophysiological abnormalities and consequent dysfunctional operations in the cortico-basal ganglia network for motor control constitute the core symptomatic pathogenesis in PD4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Among them, the subthalamic nucleus (STN) and the striatum have received much attention as they are the major targets of both midbrain dopaminergic13,14,15,16,17 and motor cortical18,19,20,21,22 outputs and show prominent electrophysiological derangements in PD23,24,25,26,27,28,29.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) comprises passage of electric currents into the key sites in the cortico-basal ganglia network such as STN30,31. The recent success of DBS in amelioration of parkinsonian locomotor deficits has lent a strong support for the view that PD is a disorder of neural dysrhythmias. After dopaminergic deprivation, which tends to hyperpolarize STN neurons to facilitate the burst mode of discharges32,33,34, STN neurons show excessive and inflexibly prolonged burst discharges7,25,26,35,36. The excessive STN bursts are not just an associate but have a direct causal relation with the symptomatic pathogenesis in PD23,24,25,37,38,39,40,41. Different in situ physical and chemical techniques suppressing burst discharges in STN, including DBS with sustained depolarizing currents (extracellular delivery of constant negative currents or negative DC), T-type Ca2+ channel blockers, or hERG channel inhibitors, would effectively ameliorate the locomotor deficits in PD23,24,25,26,39,41. In contrast, hyperpolarization of the STN neurons by extracellular application of positive currents increases burst discharges in STN and leads to locomotor deficits in a normal animal with intact dopaminergic supply24,38,41. In other words, charging/discharging of membrane capacitor may play a central role in the effect of STN DBS, although the other mechanistic elements may also be involved42,43,44.

STN burst discharges are not mainly driven by h-currents40,45 and thus not fully autonomous from a cellular point of view. Instead, they require the glutamatergic drive from the motor cortex (MC) to be generated25,40. The “relay burst” discharges of STN are therefore responsible for the information relay directly from MC via the “hyperdirect” pathway, which conducts a negative feedback to MC in the cortico-subcortical re-entrant loops to control motor execution25,40. Optogenetic random overdrive of the corticosubthalamic fibers thus results in parkinsonian locomotor deficits in normal animals37, demonstrating a crucial role of MC in control of STN burst discharges and consequently locomotor deficits in PD. MC takes the strategic coalescing point of the pyramidal and extrapyramidal systems, and is the principal origin of the motor pathways descending to the brainstem and spinal cord. MC is also a target of dopaminergic innervation from SNpc, although the local dopamine concentrations could be lower than that in the striatum46,47,48. There are reports on the changes of MC neuronal activities, such as an increase in mean firing rates or burst discharges, after experimental dopaminergic deprivation49,50. Moreover, the time-dependent variations in MC discharges during movement seem to be reduced in PD, implying less efficient peri-movement cortical motor programming51. We have recently reported higher MC activities but inadequate spatiotemporal changes upon movement, in addition to excessive as well as inflexibly prolonged STN burst discharges in PD26. Neuroimaging data also support alterations in MC activities at rest or during voluntary movement in PD patients52,53,54,55. MC therefore could be a potential target for neuromodulatory therapy for PD or even other movement disorders. Therapeutic trials with transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) or transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) have been exercised, but the results are variable and no rationale-based protocols are available at present56,57,58,59,60,61,62. We investigated the electrophysiological and behavioral consequences of MC stimulation (MCS) in normal and 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-induced hemiparkinsonian rats (hereafter referred to as PD rats). Although application of large current to a region anterior to primary MC (e.g. secondary motor areas) may also elicit movements in rodents63,64,65, a large part of the effect is likely made through primary MC64,66,67. Also, we have demonstrated that the effect of STN DBS on membrane potential (e.g. depolarization or hyperpolarization) and discharge patterns is closely correlated with the polarity and the amount of extracellularly delivered charges with multiple lines of in-vitro and in-vivo evidence24,25,26,38,41. We therefore investigated the action of epidural primary MC stimulation (MCS) with sustained currents for simplicity. We found that extracellular delivery of sustained constant positive and negative currents in MC slices causes hyperpolarization and depolarization of MC neurons, respectively, and results in corresponding discharge pattern changes in a dose (current amplitude)-dependent manner. In contrast to the depolarizing STN DBS (extracellular application of negative currents), which may ameliorate parkinsonian locomotor deficits but induce more behavioral “restlessness” by indiscriminately decreasing peri-movement STN burst discharges (the “brakes”)26, hyperpolarizing MCS enhances locomotor behaviors with better preservation of interim pauses between motor activities. A delicate tuning and/or combination of MCS and subcortical (e.g. STN) DBS based on mechanistic considerations and individualized clinical features may provide a better therapeutic approach for PD.

Results

Motor cortex stimulation enhances locomotor activities in parkinsonian rats

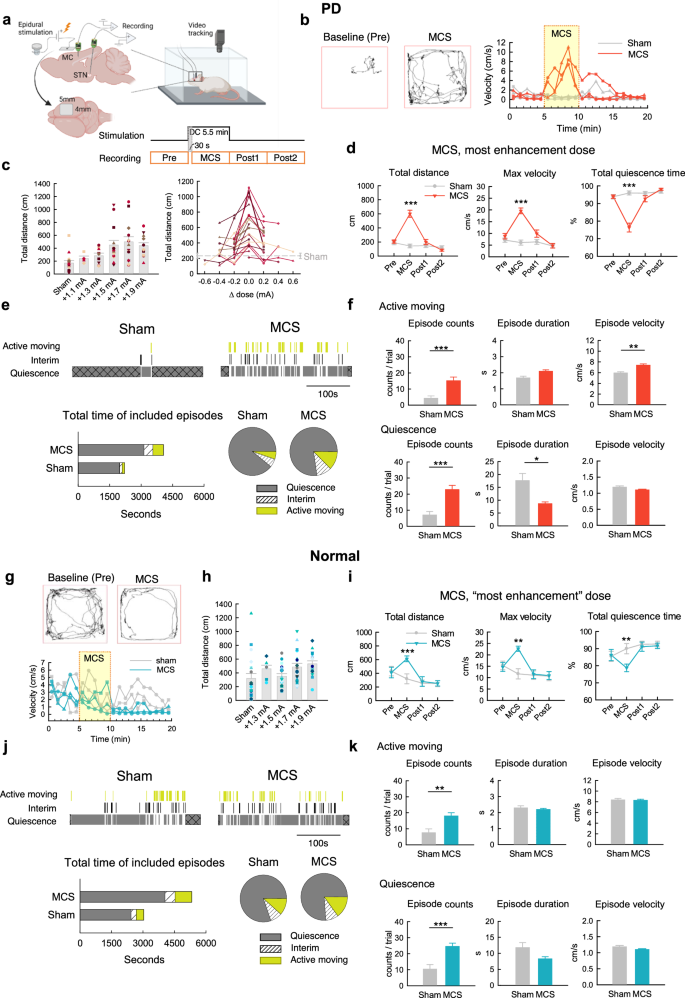

Because ictogenic effects may be induced by pulsatile cortical stimulation over a very wide range of pulse frequencies (e.g. 5–500 Hz)68, we have focused on motor cortex stimulation (MCS) with constant currents. We found that MCS with finely tuned extracellular delivery of sustained positive currents may have a prominent ameliorating effect on locomotor deficits in open field tests (OFT) in parkinsonian or PD rats (Fig. 1a–d). The increase in total moving distance is in general current “dose”-dependent from +1.1 to 1.5 mA, and then “saturated” from +1.5 to 1.9 mA. A close look of the effect in each rat further demonstrates that the dose dependence is not monophasic, and there could be a decrease in moving distance if higher currents are applied beyond the “optimal” dosage (Fig. 1c). Moreover, propulsive movement similar to that happens in PD patients may appear particularly with excessive stimulation PD rats (Supplementary Fig. 1), suggesting that the hyperpolarizing stimulation does not work by simplistic inhibition of MC activities. We analyzed the gross effect of MCS on locomotor activities with division of the behaviors during MCS into quiescent and active moving episodes according to the moving velocity (Fig. 1c–f). The total moving distance and maximal velocity, together with the count and mean duration of active moving episodes, are increased by MCS with the “most enhancement” dose. The quiescence episodes are also increased, but the mean duration of quiescence episodes are markedly decreased. In contrast to the case in PD rats, similar MCS applied to control (normal) rats shows a different and less consistent effect on locomotor activities. There is no definite turning point or dose-dependent effect on total moving distance with a MCS range from +1.3 to 1.9 mA in normal rats (Fig. 1g, h), despite a positive effect (smaller than that on PD rats) on total moving distance, maximal velocity, and total quiescence time with MCS at the most enhancement dose (Fig. 1i). The relatively small and inconsistent positive effects of MCS on normal subjects may chiefly arise from the less increase in active moving velocity and decrease in quiescence duration (Fig. 1j, k). There is also an increase in propulsive tendency with MCS in normal subjects, but in much smaller scale (Supplementary Fig. 1). The amelioration of locomotor deficits by MCS in PD rats thus most likely involves a resumption of “agility” demonstrated by the increased of both moving episodes (with higher speed) and quiescence episodes (with shorter duration). On the other hand, propulsion could still be induced by excessive MCS especially in a dopamine-deprived system.

a Illustration of experimental design (created in BioRender). Each trial is composed of four 5-min epochs in the open field test (OFT) for data analysis. The results obtained at the first 0.5 min of MCS are omitted for accuracy (see Methods). Parts (b–f): PD rats. Parts (g–k): normal rats. b Sample trajectory and velocity-time maps in response to MCS. c Total moving distance with MCS or sham stimulation is plotted against the absolute MCS amplitude or “dose” (n = 4–23 rats, left) or the difference from the most enhancement dose (which is ~+1.7 mA, right). Each symbol and/or line marks the data from an individual rat. d Locomotor parameters with the most enhancement dose are compared (n = 23 rats). e Top, The over-time changes in behavior episodes, which are defined by the moving velocity (see Methods). The first and the last episodes (cross marks) in the 5-min recording epoch are excluded from analysis because the exact duration of the two episodes cannot be defined. Bottom, The cumulative time (stacked bars) and the proportion of time spent in different behavior states (pie graphs) (n = 112, 100, and 68 episodes with sham stimulation, and 364, 318, and 242 episodes with MCS, from 16 PD rats in the states of quiescence, interim, and active moving, respectively). f The MCS effect on the properties of behavior episodes (n = 112 and 364 episodes of quiescence, and n = 68 and 242 episodes of active moving, from 16 PD rats with sham and MCS, respectively). The trials where the propulsive turning behaviors occur (in 7 PD rats, see Methods and Supplementary Fig. 1) are excluded from analysis. g–k Similar experiments and analyses to those in (b–f) are performed in normal rats. h: n = 7–20. i: n = 20. j, k: n = 207, 212, and 151 episodes with sham stimulation, and n = 490, 392, and 362 episodes with MCS, from 20 rats in the states of quiescence, interim, and active moving, respectively. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, Mann-Whitney U tests.

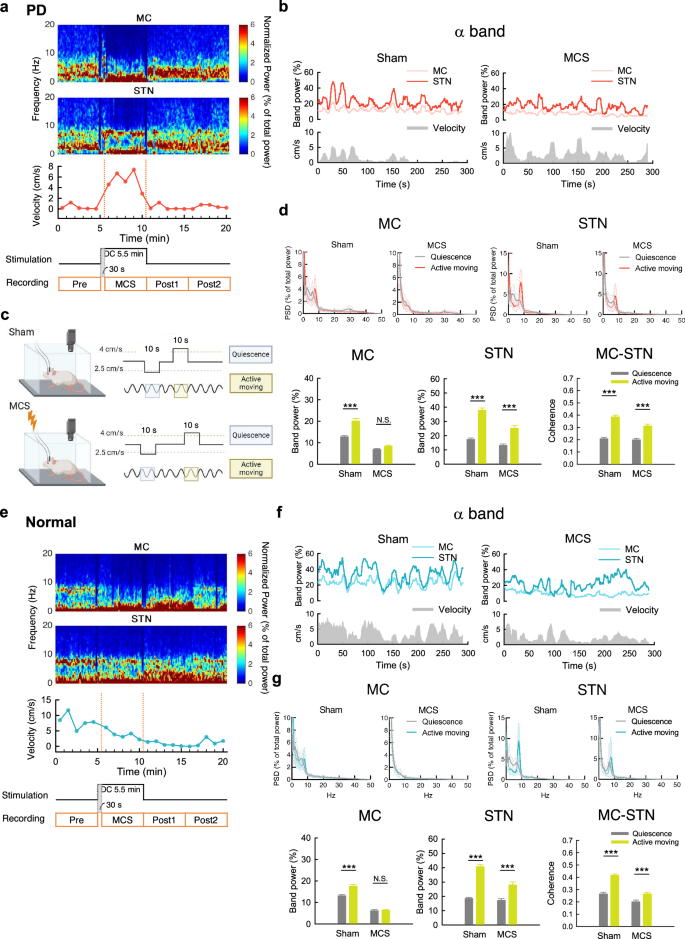

Motor cortex stimulation decreases the α augmentation but preserves the α coherence upon active moving

We have reported a marked increase of α power (“α augmentation” or “prokinetic α “) in local field potentials (LFP) in the motor cortex (MC) as well as the subthalamic nucleus (STN) from quiescence to active moving26, as if α augmentation signals a harmonic or effective operation in the cortico-subcortical re-entrant loops for active moving. With MCS, the α augmentation in MC is very much attenuated while that in STN is preserved in both PD (Fig. 2a–d) and normal rats (Fig. 2e–g). The augmented MC-STN α coherence upon active moving is also preserved. MCS thus directly modifies MC activities, but well preserves the cortical-subcortical association. The similar MCS modification on electrophysiological activities in MC but the dissimilar locomotor behavioral outcomes in normal and PD subjects then underscores the crucial roles of different subcortical processings. In any case, the MCS-altered MC activities seem to transcend the parkinsonian derangements in the cortico-subcortical re-entrant frameworks to resume locomotor activities, well consistent with the position of MC as the origin of final common pathway of descending motor control.

a Time-frequency power plot in MC and STN (upper two panels), aligned with moving velocity (lower panel), before, during, and after MCS (lower two panels). Note the increase in moving velocity and α power in STN but not MC. b Sample recordings of time-varying relative α band power and moving velocity reveals a positive correlation between α power in either MC or STN and moving velocity with sham stimulation. The correlation is present only in STN but not MC during MCS. c Electrophysiological data in specific locomotor behavior states are deliberately selected and analyzed (created in BioRender). d Power spectral density plot (left) and band power analysis in α band frequency (7–10 Hz) (right). The STN α augmentation (increase in α power) from quiescence to active moving (see Methods) and the augmented MC-STN α coherence upon active moving are preserved with MCS, which markedly attenuates the α augmentation in MC (n = 39 from 13 rats and 34 from 14 rats for sham and MCS, respectively). e–g Similar experiments and analyses to that in part (a–d), but in normal rats (n = 43 from 14 rats and 53 from 19 rats, sham and MCS, respectively). Once again, the α augmentation from quiescence to active moving is preserved in STN but abolished in MC. The augmented MC-STN α coherence upon active moving is also preserved. ***p < 0.001, N.S. nonsignificant, Mann-Whitney U tests.

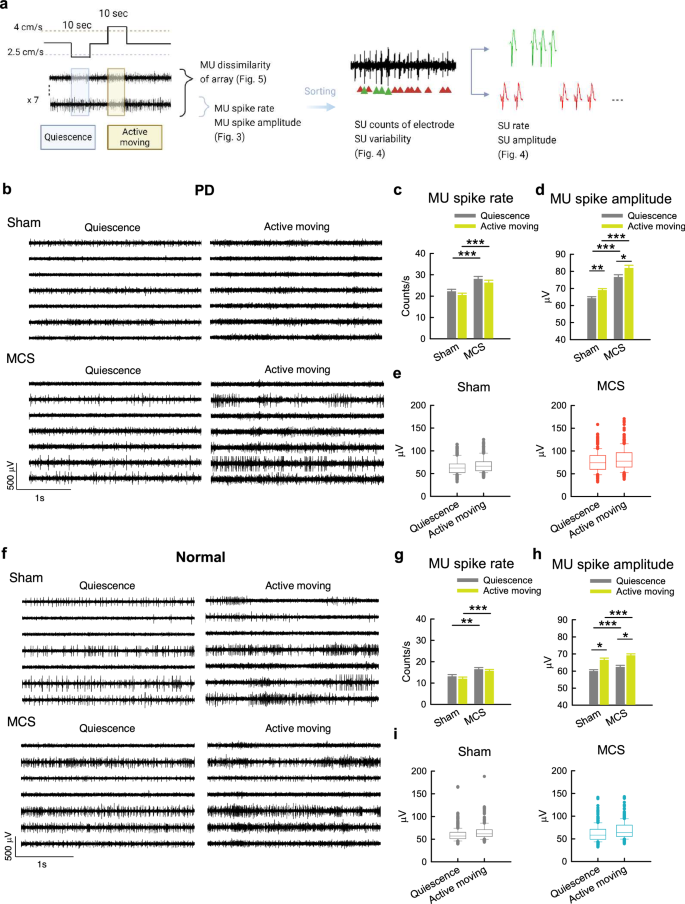

Motor cortex stimulation increases multi-unit spike amplitude and overall spike rates in the motor cortex

We turned to investigate the electrophysiological activities in MC with multi-unit (MU) recordings. In general, there are higher spike rates and much lower variability in spike amplitude in PD than normal rats26. MCS markedly increases the spike rates, the spike amplitude, and the variability of spike amplitude in PD rats during either quiescence or active moving states (Fig. 3a–e). MCS also increases the spike rates and spike amplitude but not the variability of spike amplitude in normal rats (Fig. 3f–i). It is thus interesting to note that the variability of spike amplitude in PD is “restored” by MCS to the level of that in normal subjects with sham stimulation.

a Illustration of MU and SU analysis methods in Figs. 3 to 5. The effects of MCS on MU activities in PD rats are shown in (b–e), and those in normal rats in (f–i) in this figure. b Sample sweeps of MU activities in MC of PD rat in quiescent or active moving states upon sham stimulation or MCS. c, d There is an evident increase in MU spike rates (c) and amplitude (d) during MCS if compared to sham in PD rats. However, there is no definite change of spike rates (c) or just a small increase of spike amplitude (d) from quiescence to active moving in spike rate both during sham (n = 273 MU segments from 13 rats) and MCS (n = 238 MU segments from 14 rats). e Box plots including the lower and upper quartiles and the median show the data distribution from part (d). The whiskers mark the 10th and 90th values of the dataset to display the range of outliers. The MU spike amplitude is skewed upward, suggesting a wider distribution of spike amplitude with an increase of larger spikes with MCS in PD. In contrast, the MU spike amplitude shows a much narrower distribution (or much higher homogeneity) at baseline in all recording site. f–i Similar experiments and analyses are done in normal rats. There is just a small increase in MU spike rate and spike amplitude with MCS. There is also a small increase of spike amplitude from quiescence to active moving with both sham stimulation (n = 301 MU segments from 14 rats) and MCS (371 MU segments from 19 rats). The distribution of MU spike amplitude, however, do not show an obvious change with MCS in normal subjects. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, Student’s t tests or simple main effects from 2*2 independent-model ANOVA (see Methods).

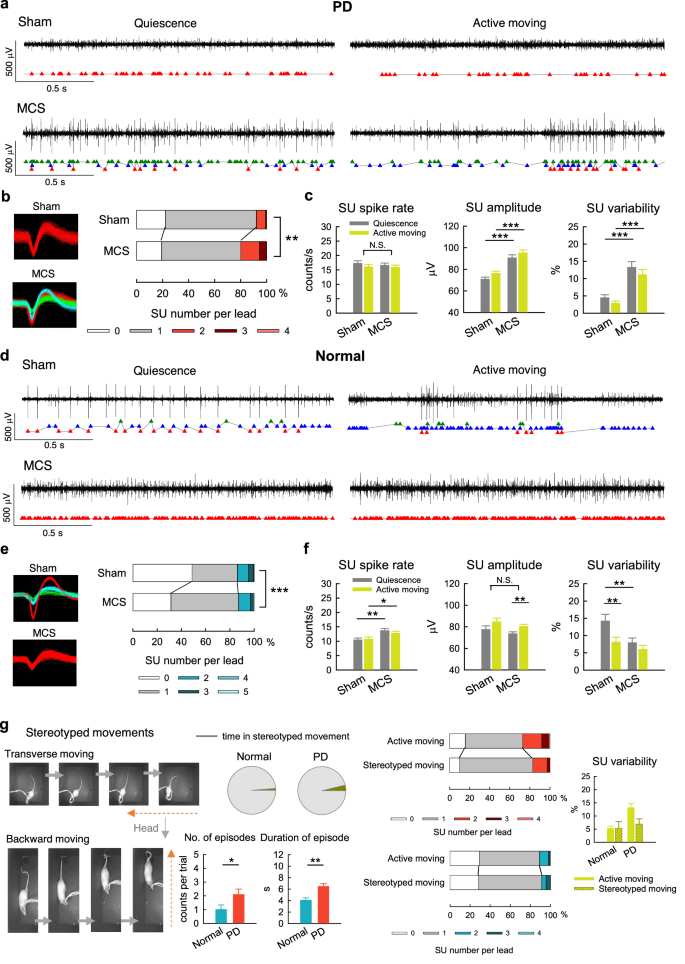

Motor cortex stimulation increases the variability of single-unit spike configuration in the motor cortex of parkinsonian but not normal rats

We further dissected the basis underlying MU spike variability changes by sorting MU into single-unit (SU) spikes according to a combination of different parameters in spike configurations (Fig. 4a, b). While the overall spike counts are increased, the variability of SU spike configuration is decreased in PD (Fig. 4b, c) than in normal rats (Fig. 4d–f) with sham stimulation, implying that the unit discharges are more similar in amplitude and configuration with dopaminergic deprivation. MCS increases the amplitude, types, and especially the temporal variability of SU spikes, but does not change the SU spike rates, in PD (Fig. 4b and c). In contrast, MCS increases the rate but not the amplitude, and decreases the types of SU spikes in normal rats, together with a decrease in the temporal variability of SU spikes (Fig. 4, e and f). It is interesting to note, once again, that the SU variability in PD is “restored” by MCS to the level of that in normal subjects with sham stimulation. On the other hand, MCS may result in an increase of stereotyped behaviors including continuous backward steppings or transverse moving in normal and especially in PD rats (Fig. 4g). While SU variability is in general increased in PD with MCS, the variability is markedly decreased during the stereotyped movement as if similar engrams are repeatedly executed. This scenario may be related to the higher likelihood of burst-like MC discharges with hyperpolarizing MCS (Fig. S2)69,70,71,72,73. The changes in MC discharge pattern, and the consequential effects on MC SU spike amplitude, variability, as well as behavioral presentations are different between PD and normal subjects because of the deranged subcortical processings in the former but not the latter (see Discussion).

a After spike sorting (see Fig. 3a), there is just one type of SU activities at baseline (sham, indicated by red squares below the sweeps) but multiple types of SU activities during MCS (red, blue, and green triangles) in quiescence and active moving episodes in PD rats. There is also higher spike variability (see Methods) during MCS than sham. b The percentage of leads with 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 SU cluster(s) detected from 10 s recordings in PD rats. There are more SU clusters during MCS (n = 406 SU clusters) than sham (n = 546 SU clusters; 0 cluster vs 1 cluster vs >1 cluster, chi square test, χ2(2) = 29.97, p < 0.001). c SU parameters during MCS (compared to sham) in PD rats (n = 228–238, 221–234, 193–284, and 194–278 SU clusters for quiescence/sham, active-moving/sham, quiescence/MCS, and active-moving/MCS groups, respectively). d–f Experiments and analyses similar to those in (a–c) are obtained from normal rats (n = 602 and 742 SU clusters for sham and MCS, respectively; 0 cluster vs 1 cluster vs >1 cluster, chi square test, χ2(2) = 48.45, p < 0.001). SU parameters: n = 155–226, 153–196, 230–287, and 248–296 SU clusters for quiescence/sham, active-moving/sham, quiescence/MCS, and active-moving/MCS groups, respectively. g More prominent stereotyped movements (i.e. more episodes and longer episode duration) during MCS in PD than in normal rats. During stereotyped movement, there is also a tendency of increase in the percentage of leads with single SU and lower SU variability than during active moving with MCS in PD rats (SU clusters in each leads: n = 50 and 248 in normal, and n = 63 and 194 in PD, during stereotyped moving and active moving, respectively, chi square test; SU variability: n = 70 and 371 in normal, and n = 70 and 203 in PD, during stereotyped moving and active moving, respectively, Mann-Whitney U tests). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, N.S., nonsignificant, Student’s t tests (lines) or simple main effects (lines)/main effects (brackets) from 2*2 independent-model ANOVA (see Methods).

Motor cortex stimulation increases the spatiotemporal changes in cortical activities in the parkinsonian but not normal rats

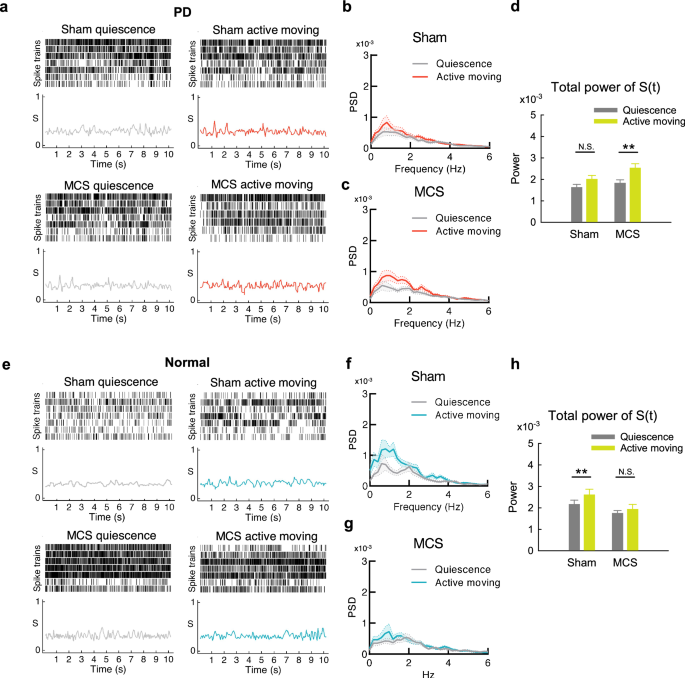

We have seen that MCS increases locomotor activities in PD by increase of the duration, velocity, and especially episodes of active moving (Fig. 1). In the meanwhile, the duration of quiescence is markedly shortened, as if the animal is much prone to move with MCS. Accordingly, the SU types and the temporal changes of SU discharges are increased in PD with MCS at either active moving or quiescence states (Fig. 4). This suggests general escalation of the “agility” of cortical engram changes. We further investigated the changes in cortical activities between active moving and quiescence states. From quiescence to active moving in normal rats, MC MU activities are not necessarily increased (Fig. 3f). However, the temporal changes in the same electrode, and the spatial changes among different electrodes are increased26. Such an enhancement of spatiotemporal changes of MC MU activities associated with movement in normal subjects, however, is decreased in PD rats (Fig. 5 a and b)26. With MCS, the spatiotemporal changes of MC MU activities associated with movement are restored in PD rats (Fig. 5c, d) but decreased in normal rats (Fig. 5, e to h). This is consistent with the findings in Fig. 4 that the SU spike variability in temporal sequence is increased in PD but decreased in normal rat with MCS.

a Sample raster plots of multi-unit spikes from 7 MC leads and concomitant dissimilarity score (S) of the 7 leads, from a segment at quiescence (upper) and the other one during active moving (lower) at baseline (left) and during MCS (right) in a PD rat. b and c The average power-frequency spectra of the whole temporal profile of S (S(t)) in all segments in part A show an increase in MC spatiotemporal changes from quiescence to active moving with MCS (if compared to that with sham) (n = 27 and 26, sham and MCS, respectively). d The total powers (1-100 Hz) of the spectral analyses in parts B and C show a significant increase of spatiotemporal changes from quiescence to active moving with MCS but not at baseline in PD rats. e Sample raster plots of multi-unit spikes from 7 MC leads and concomitant dissimilarity score (S) of the 7 leads, from a segment at rest (upper) and the other one during movement (lower) at baseline (left) and during MCS (right) in a normal rat. f and g The average power-frequency spectra of the whole temporal profile of S (S(t)) in part E show a decrease in MC spatiotemporal change from quiescence to active moving with MCS (if compared to that with sham) (n = 16 and 17, sham and MCS, respectively). h The total powers (1-100 Hz) of the spectral analyses from segments in parts f and g show a significant increase of spatiotemporal changes from quiescence to active moving at baseline but not during MCS in normal rats. **p < 0.01, N.S., nonsignificant, Mann-Whitney U tests.

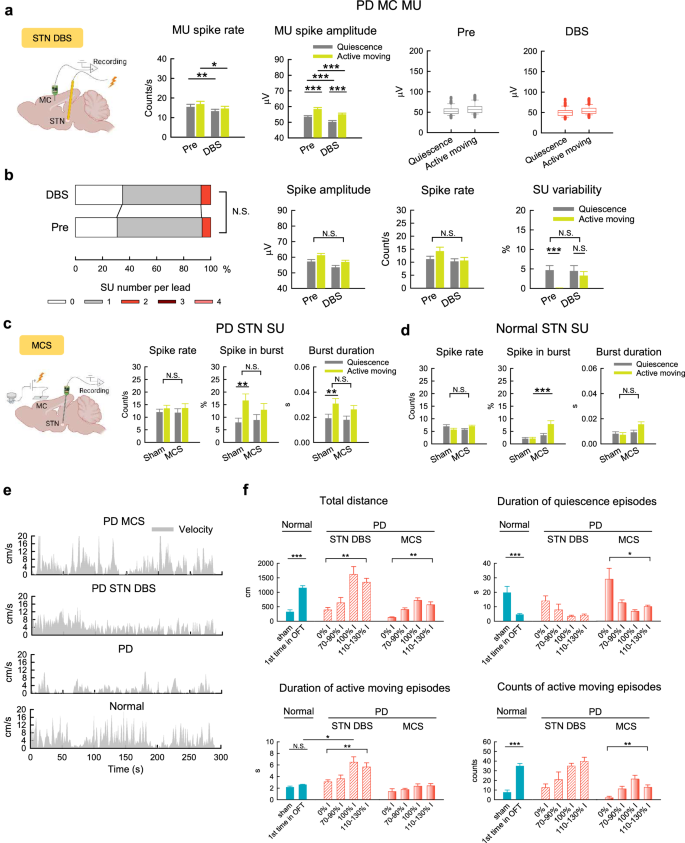

Motor cortex stimulation shows an effect distinct from subthalamic deep brain stimulation

Subthalamic deep brain stimulation (STN DBS) is a common practice effectively ameliorating locomotor activities in PD, and we have shown that STN DBS works by decrease of STN burst discharges23,24,25,26,38,41. We have also investigated the effect of STN DBS on MC activities in PD rats, and found that the increase of MC MU spikes (the “noisy cortex”) could be partly rectified, with an increase of spatiotemporal changes upon movement26. The decrease in SU types or the less-variable MU amplitude distribution in MC in PD rats (Figs. 3e and 4b), however, is not effectively normalized by STN DBS (Fig. 6a, b). The other parameters of MC activities also show no definite changes by STN DBS (Fig. 6b and S2). On the other hand, the pathognomonic excessive STN burst discharges in PD are not rectified by MCS (Fig. 6c). In contrast, there is an increase of STN burst discharges with MCS in normal subjects, especially during active moving (Fig. 6d). We have previously shown that STN burst discharges are “relay” bursts which are dependent on the amount of glutamatergic input from MC25,40. Although stimulation of corticosubthalamic fibers could induce parkinsonian locomotor deficits37,38,40, MC activities induced by MCS may have an opposite effect. The effect of MCS in PD, therefore, may involve the corticostriatal pathway, the other major output from MC in addition to the hyperdirect (corticosubthalamic) pathway (see Discussion). Behaviorally, MCS is apparently less effective than STN DBS for PD in terms of the total distance traveled in the open field free-moving test (Fig. 6e, f). MCS, however, leads to a ceiling effect on behavior close to that in normal (sham). In contrast, the ceiling effect of STN DBS is close to or even goes beyond the level of first time in OFT, a phenomenally hyperactive state. Specifically, MCS shows short pauses intermixed in the movement period very similar to normal, whereas STN DBS dose-dependently prolongs the movement period even to an extent of apparent “restlessness” (Fig. 6e, f). MCS thus could have a more assured “normalization” effect with higher safety in terms of fewer adverse events associated with inadvertent overdrive.

a, b MU (a, n = 133 MU segments from 7 rats) and SU (b, sorted from a) activities in MC before (Pre) and during DBS at STN (STN DBS) in PD rats. In (b), n = 147 SU clusters; 0 cluster vs 1 cluster vs >1 cluster, chi square test, χ2(2) = 1.33, p > 0.05 (left), and n = 91-129, 93-113, 83-109, and 90-117 SU clusters for quiescence/before DBS, active-moving/ before DBS, quiescence/during DBS, and active-moving/during DBS, respectively. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, N.S., nonsignificant, Student’s t tests (lines) or simple main effects (lines)/main effects (brackets) from 2*2 ANOVA (see Methods). c, d SU activities in STN with MCS in PD rats (c, n = 48, 50, 53, and 50 SU clusters from 10 rats for quiescence/sham, active-moving/sham, quiescence/MCS, and active-moving/MCS groups, respectively) and normal rats (d, n = 79, 71, 108, and 106 SU clusters from 8 rats, respectively). e Continuous recordings of moving velocity in OFT over time in representative PD and normal rats. f Dose-dependent effects on behavioral parameters with STN DBS and MCS in PD rats (DBS: n = 6 rats, the current intensity with the maximal total moving distance without propulsive turning or restless turning is defined as 100% I; MCS: n = 6 rats, 100% I is the most enhancement dose without propulsive turning). The data of sham stimulation (sham) and of the first run in OFT from each normal rat (1st time in OFT) are also documented for comparison (from the same rats in Fig. 1i). The normal rats usually show “vigorous” onset of locomotor activities without lengthening the active moving episode for the first run. In contrast, STN DBS in PD rats induces significant changes in the duration of active moving episode, while MCS does not have similar effects. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, N.S., nonsignificant, Friedman tests (data with 4 groups) or Mann-Whitney U tests (data with 2 groups). The illustrations in a and c are created in BioRender.

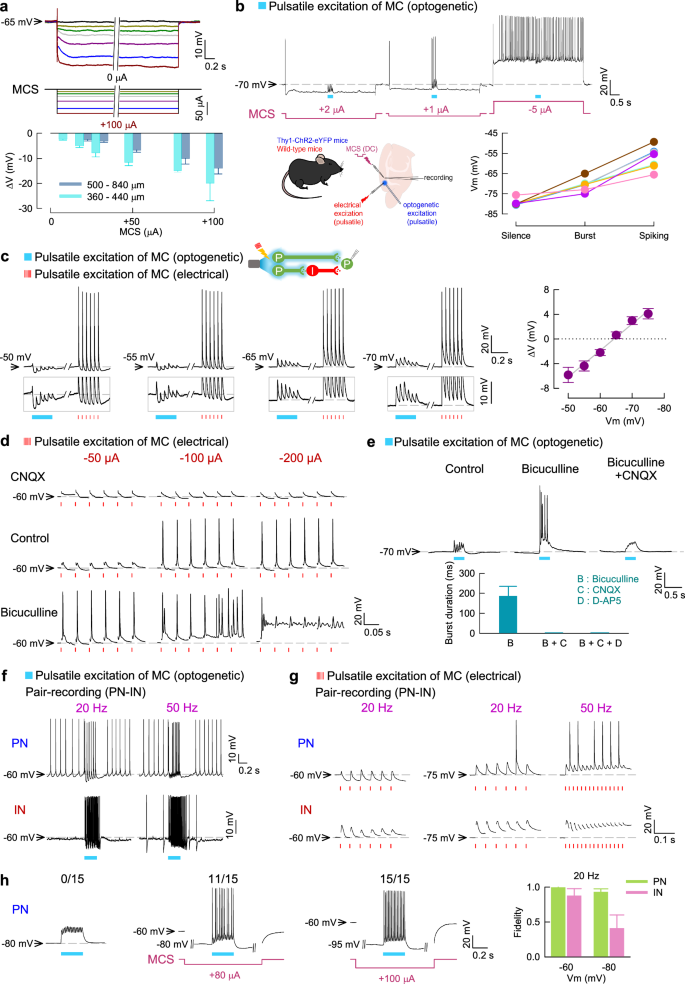

Hyperpolarizing stimulation of motor cortex causes disinhibition of pyramidal neurons on a silenced background

Cellular and local network responses to MCS were further dissected in acute MC slices, where pyramidal neurons (PN) and fast-spiking interneurons (IN) can be identified by their morphology and electrophysiological properties (Supplementary Fig. 3a–c). We showed that neuronal membrane potential is proportionally altered according to the amplitude of extracellularly applied currents (or “MCS”) as well as the distance between the stimulation site and the neuron (Fig. 7a). Moreover, neuronal membrane hyperpolarization and depolarization are determined by the polarity of the extracellularly applied currents (Fig. 7b). The “sag” potential is small upon current injection and the “rebound burst” upon switching off the hyperpolarizing pulse is rarely observed (Supplementary Fig. 3b–d), suggesting that MC neurons contain functionally inadequate h-currents for autonomously repeated burst discharges. Hyperpolarizing current pulses would not elicit neuronal discharges, consistent with a silencing effect of hyperpolarizing MCS. On the other hand, neuronal discharges may occur upon depolarizing pulses, with IN activities more steeply dependent on the amplitude of current injection than PN activities (Supplementary Fig. 3d). MC neuronal activities thus seem to be dependent more on extrinsic depolarizing drive rather than intrinsic oscillating cellular elements. Hyperpolarizing MCS would make a more silent background, and extrinsic glutamatergic input of adequate magnitude from the network is necessary to elicit neuronal activities (Fig. 7b, Supplementary Fig. 3e). The pattern of elicited discharges is also dependent on the membrane potential, which is tunable by MCS (Fig. 7b). Interestingly, the discharges in PN (the principal neurons in MC) are under a very tight recurrent (presumably feedforward and/or feedback) GABAergic control from IN. Excitatory glutamatergic input to PN, triggered by either electrical or optogenetic (PN-selective) stimulation of the network, is associated with feedforward inhibition which is most likely GABAergic as the postsynaptic currents are reversed at the reversal potential of GABAA receptors (Fig. 7c). Without GABAergic control (e.g. in the presence of GABAA receptor antagonists), glutamatergic input would then trigger prominent burst discharges and even depolarization block that outlasts external pacing (excitatory drive) in PN (Fig. 7d, e). Pair recording of a PN and an IN in MC further shows that the glutamatergic drive from the network simultaneously elicits discharges in both neurons, with a silent period in PN following IN bursts (Fig. 7f). The discharges in both PN and IN therefore carry strong “relay” rather than autonomous features, and are tightly controlled by glutamate-GABA interplay. Hyperpolarizing MCS applied to the network may alter the membrane potential and decrease the activities of both PN and IN. However, with the same hyperpolarization and the same extrinsic pacings, there is a tendency of more elicited (relayed) spikes in PN than in IN (Fig. 7g). This could be ascribable to the different (steeper) dependence on membrane potential for IN discharges (Supplementary Fig. 3d). Again, an intense feedforward GABAergic control in PN does not seem to appear in IN (see the leftmost panels in Fig. 7g). Appropriately adjusted hyperpolarizing MCS may thus selectively suppress GABAergic control of the network and cause overall disinhibition of PN on a more silent background of the network activities. PN may then be more active in relaying discharges from the network (Fig. 7h), leading to changes in spatiotemporal patterns of MC activities and behavioral presentations (see Discussion).

a The membrane potential of MC PN is tunable by extracellularly-applied constant currents (MCS). Synaptic transmission is inhibited by CNQX, D-AP5, bicuculline, and CGP-35348. The voltage changes (∆V) are proportional to the hyperpolarizing (positive) MCS amplitude and the distance from the stimulating electrode (n = 3–11, wild-type or Thy1-ChR2-eYFP mice). b Selective photoexcitation (1.7 mW, 20 Hz, 300 ms, blue) of MC triggers glutamate release and elicits PN discharges according to the membrane potential (Vm) adjusted by MCS (n = 7, Thy1-ChR2-eYFP mice). c Electrical and optogenetic excitatory stimulation on MC (pulsatile, 20 Hz) similarly elicits EPSPs and putatively GABA-mediated responses (reversed at ~-65 mV) in the same PN. The change in baseline membrane potential (∆V) measured at 100 ms after light application is plotted against Vm before light (right, n = 11, Thy1-ChR2-eYFP mice). The line is a linear regression. d The responses of a representative PN to electrical stimulation on MC (20 Hz at different intensities) are altered by CNQX and bicuculline. e Selective photoexcitation (as that in b) induces GABA- and glutamate-dependent burst discharges in PN, where Vm is set at −70 mV by MCS (n = 11 bursts from 3 neurons). Burst duration is measured as the time interval between the first and the last spikes. f, g Paired recording of PN and IN shows that both neurons respond to excitatory inputs from MC (induced by optogenetic (f) or electrical (g) stimulation, see c) but PN is under more prominent GABAergic control. h Left, Hyperpolarizing MCS may increase the fidelity of PN relay (postsynaptic spike number/15 light pulses applied at 50 Hz on MC). Right, The fidelity of response (postsynaptic spike number/6 light pulses applied at 20 Hz on MC) is more decreased in IN than PN at a hyperpolarized membrane potential. Each n = 6 from Thy1-ChR2-eYFP mice. The drug concentration used: 10 μM CNQX, 20 μM D-AP5, 20 μM bicuculline, and 20 μM CGP-35348.

Discussion

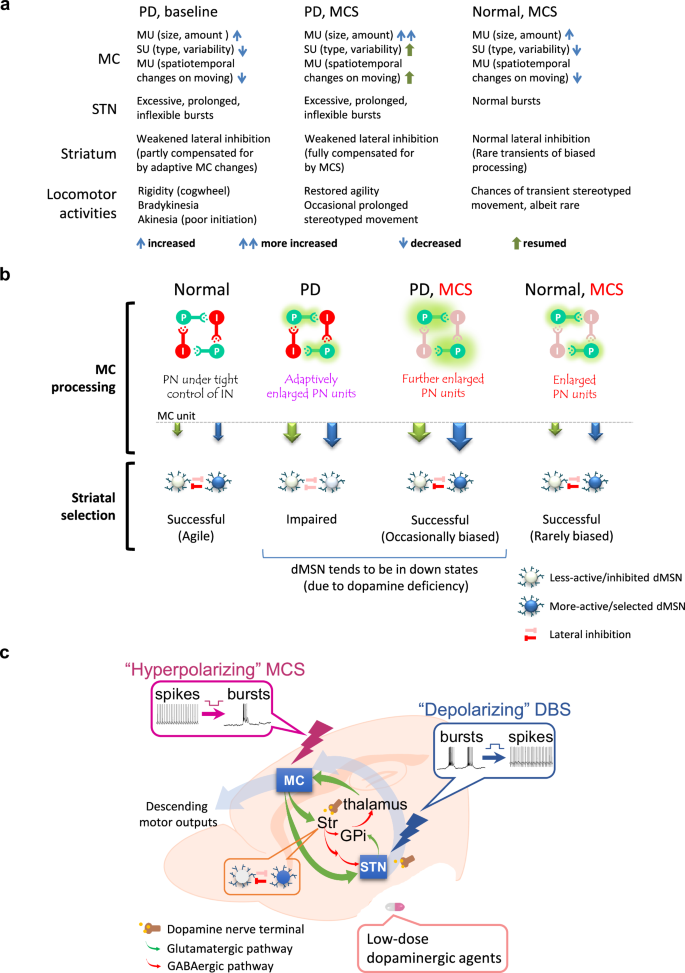

The two cardinal electrophysiological derangements in PD are excessive, prolonged and inflexible burst discharges in STN23,24,25,26 and enhanced down states of the medium spiny neurons for the direct pathway (dMSNs) in the striatum27,28,29 (see Fig. 8 for schematic models). Interestingly, STN and the striatum also are the two principal subcortical structures innervated by not only MC but also the dopaminergic fibers from the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc)74. We have previously proposed that the major functional role of STN is timely electrophysiological and mechanical “cancellation” of MC activities, so that the gross execution of premature motions is prohibited25. The excessive and inflexible STN bursts in PD lead to inappropriate cancellation, and thus residual or surplus MC activities which could induce next inappropriate STN bursts. These secondary errors lead to enhanced “oscillating” MC discharges, and thus the “noisy” MC (Fig. 3) and parkinsonian locomotor deficits26. The noisier MC may be at most distantly related to the well-known β augmentation, or enhancement of the β power, in PD. A tight association is unlikely, as β oscillation develops evidently later than the increase of STN bursts75. Also, β augmentation shows a rather high variability, and is present bilaterally after unilateral dopaminergic deprivation75. On the other hand, the enlarged MC MU amplitude but decreased SU variability in PD (Figs. 3 and 4)26,49,51,76 may be ascribable to dopamine deficiency-induced enhancement of down states and thus impaired lateral inhibition of dMSNs that are responsible for modification/selection of motor engrams27,28,29. Mechanistically, the recorded unit activities result from represent phasic local current flow and thus regionally synchronous neuronal discharges. Delivery of extracellular positive currents leads to dose-dependent membrane hyperpolarization of cortical neurons (Fig. 7). More glutamatergic currents are then needed to depolarize the neurons to the threshold of firing. The requirement on timely spatiotemporal summation of inputs is thus more stringent with general inhibition of MC PN and IN (i.e. a decrease of background “noise”). On the other hand, PN may also be partly “relieved” from the tight control of IN. MC units are thus increased both in number and amplitude with hyperpolarizing MCS, compensating for the enhanced down state in dMSNs and weakened striatal lateral inhibition. Smooth selections and transitions of MC units or engrams are thus restored and parkinsonian locomotor deficits ameliorated by hyperpolarizing MCS, most likely at the expense of accuracy of the engram itself (Fig. 8). This is probably true for all brain stimulation therapies so far, namely a minor electrophysiological or subclinical expense for a major behavioral or clinical benefit.

a A table summarizing the experimental findings on the MC activities, together with the presumed subcortical (subthalamic and striatal) mechanisms, for the making of behavioral consequences in normal and PD animals with or without MCS. The enlarged MU units are probably adaptive changes for the impaired striatal lateral inhibition in PD. More cortical input to striatum may then partly compensate for the enhanced down state in medium spiny neurons (of direct pathways, dMSNs) to restore the impaired striatal lateral inhibition due to dopaminergic deprivation. MCS further enlarges MU units to enhance the compensation and thus even smoother flow of motor commands and behavioral agility. b Schematic drawings depicting the effect of MCS. Different MC units (or motor engrams in a broad sense) are shown in arrows of different colors, with the size denoting the amplitude. The “automatic” serial changes in MC engrams are consequences of subcortical processing including striatal lateral inhibition, which is impaired in PD. With the adaptively larger MC units in PD, striatal lateral inhibition is partially restored, but MC engrams and flow of engram changes may still be deformed or ineffective, leading to decreased MU spatiotemporal changes upon movement (and decrease in varieties as well as speed of movement). MCS further enlarges MC units and compensates for the impaired lateral inhibition to restore “effective” engram changes leading to agile and adequate locomotor activities (although the engrams may still be somewhat distorted or “incorrect”). However, propulsive movement may occasionally occur because of the decreased likelihood of modification by the other units due to the subnormal striatal lateral inhibition. Propulsion could also rarely happen with MCS in normal subjects, but with smaller extent and shorter duration because of the intact striatal lateral inhibition. c The locomotor deficits in PD could be effectively rectified by hyperpolarizing MCS and depolarizing STN DBS, which increase MC and decrease STN burst discharges, respectively. A delicate tuning and/or combination of MCS and STN DBS as well as low-dose pharmacotherapies based on mechanistic considerations and key clinical parameters may provide a better practice to achieve the spirit of individualized and precision medicine for PD.

STN DBS decreases the excessive and inflexible STN bursts, one of the cardinal electrophysiological abnormalities in PD. Despite different proposals on the mechanisms underlying STN DBS, such as activation of inhibitory afferents to STN42, activation of STN neurons or axons43, or modulation of oscillatory patterns44, depolarization of STN neurons seems to play a critical role23,24,26,32,41. STN burst discharges are “relay bursts” driven by MC via the hyperdirect pathway25,40. Depolarizing STN DBS may restore the responsiveness of STN to cortical drive and subsequent timely feedback from STN to MC for proper motor execution in PD. STN DBS thus also partly rectifies noisy MC and resumes the spatiotemporal changes in MC activities as well locomotor functions (Fig. 6a)26,49. However, STN DBS is at a risk of inducing “restlessness”26, namely a prolonged moving period in a fixed direction without interim pauses (Fig. 6f). Excessive depolarization of STN neurons may result in inadequate burst discharges for the “brake” of motor commanding. This is in line with the report of better clinical effects with strong anodic STN DBS (which may overly hyperpolarize STN neurons to decrease burst discharges)77. MCS dose not decrease STN bursts in PD (Fig. 6c), but does alter MC information relay to STN (Fig. 3b−d). Although STN abnormalities may persist with MCS, the deranged STN processing seems to be “overruled” at the cortical level (see also the changes in prokinetic α augmentation in Fig. 2) as MC is both “upstream” and especially “downstream” of STN in motor control circuitries (Fig. 8). There may not be a prominent locomotor deficits in PD until dopaminergic neuronal loss up to 80%, but motor inaccuracy may be found in the “presymptomatic” stage78,79,80,81,82. It is plausible that the enhanced MC unit activities partly compensate for the weakened striatal lateral inhibition with dopaminergic deprivation83,84,85 to facilitate flow of motor engrams (at the expense of accuracy of the engrams). MCS may serve as an artificially extended form of natural compensatory maneuver, bringing back the presymptomatic or early symptomatic stages to PD patients. In this regard, MCS also offers more opportunities of fine tuning of cortical modules to make up for the inappropriate parkinsonian striatal funneling and to lead to more “normalized” motor behaviors in specific aspects (Fig. 6e, f).

Although DBS (e.g., at STN or GPi) has demonstrated a remarkable success in PD therapy, the treatment usually does not lead to full restoration of motor functions in all domains. Even for the most responsive PD symptoms such as rigidity and bradykinesia, fluctuating or mixed therapeutic effects on different domains are encountered with STN or GPi DBS86,87,88. In other words, DBS focused on one particular subcortical structure could only have a partial effect on the multifaceted electrophysiological derangements in PD. MC is the immediate origin of final common pathway for descending motor commands, and thus potentially a more “comprehensive” therapeutic target for parkinsonian motor deficits. Anodal or positive-current transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) has been proposed to enhance cortical activities and thus have a positive effect on hypoactive MC and PD symptoms56,57,89. However, there are reports of an increase of MC neuronal activities in PD or dopaminergic deprivation26,49,50,90. The low stimulation currents (~1 to 2 mA) and thus a weak electric field less than 1 mV/mm in the cortex from the extracranial route91,92 may also contribute to the highly uncertain therapeutic effects56,57. Epidural MCS, which assures a lack of direct cortical injury, seems to circumvent or overrule the complicated derangements in subcortical circuitries more assuredly to ameliorate locomotor deficits with more “normalized” behavioral patterns than STN DBS (Fig. 6e, f). It would be thus desirable to investigate the effect of MCS on axial and speech symptoms, such as impaired postural control and dysarthria, which are in general less improved with STN or GPi DBS93,94,95,96. Impaired postural control in PD has been mostly ascribed to dopaminergic deprivation of the pedunculopontine nucleus (PPN). PPN DBS thus has been exercised, but again showed inconsistent results97,98,99. The beneficial effect of rationally designed epidural MCS on axial symptoms, if established, may not only make a better clinical choice than the technically more complicated PPN or STN DBS, but also shed light on the physiological principles of postural control. In addition, direct stimulation of the motor cortex may have chances to avoid cognitive derangements associated with STN or PPN DBS100 and have higher safety with implantation of epidural than deep electrodes. On the other hand, we have seen that overly hyperpolarizing MCS may result in adverse effect such as stereotyped behaviors more than STN DBS because of its direct interferences with the competing cortical elements in the presence of deranged subcortical processing (Fig. 8). A combination of finely tuned MCS and/or DBS (at STN or the other sites) as well as low-dose pharmacotherapies (e.g., dopaminergic agents) based on in-depth mechanistic understandings may provide a promising future direction of individualized brain stimulation therapy for PD and other neural dysrhythmias.

Methods

Animals

All experiments using animals were conducted in compliance with the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of National Taiwan University College of Medicine and College of Public Health (the approval numbers: 20201039, 20201189, and 20220009), and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chang Gung University (the approval numbers: CGU109-119, CGU109-196, CGU111-122, and CGU113-011), Taiwan. Wistar rats and wild-type C57BL/6 mice were purchased from BioLASCO Taiwan Co., Ltd., Taiwan. Thy1-ChR2-eYFP (#007612) transgenic mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory, U.S.A. We used 23 rats for the PD with MCS group, 20 rats for the normal with MCS group, and 18 rats for the PD with STN DBS group. A total of 54 C57BL/6 mice (including 33 Thy1-ChR2-eYFP transgenic and 21 wild-type mice) were used for brain slice recording.

The hemiparkinsonian rat model

We applied adult male Wistar rats at 8–10 weeks of age weighted 250-400 g who were held under standard housing conditions at constant temperature, humidity, and 12 h light-dark cycle, and had food and water ad libitum. The rats were randomly assigned to a control (normal) or parkinsonian (PD) group. For the PD group, a total volume of 4 μl of 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA, 2 mg/ml) in 0.02% ascorbic acid was slowly infused at a fixed velocity of 0.5 μl/min into medial forebrain bundle or MFB (AP −2.4 mm, ML 2.2 mm, DV 8.0 mm from bregma) via a stainless steel cannula according to the stereotactic brain atlas101. Before injection of 6-OHDA, the rats were treated with desipramine (25 mg/kg) intraperitoneally. On the 7th (the first attempt) or 14th (the second attempt) day after surgery, the 6-OHDA lesioned rats received subcutaneous injection of apomorphine (0.05 mg/kg). All rats achieved more than 25 rotations contralateral to the lesion side in 5 min in the first (36 out of 41 rats) or the second (5 out of 41 rats) attempts and were included into the PD group for further experiments. There were no rats excluded due to improper lesion.

Electrode implantation for stimulation and in vivo electrophysiology recording

For motor cortex stimulation (MCS), a 4 mm × 5 mm platinum plate welded with a sliver wire was placed on the dura meter of motor cortical region (AP: 0–5 mm, ML: 0–4 mm) as the stimulation electrode. The other electrode is connected to a screw on the nasal bone (AP: 7–7.5 mm, ML: 2 mm) for unipolar stimulation. For in vivo electrophysiology recording, arrays of 7 separated insulated tungsten microwires (diameter 0.0015 inch (38 μm), California Fine Wire Company) on a 10-pin connector (Omnetics Connector Corporation) were inserted into layer V-VI of M1 (AP: 0 mm, ML: 2 mm from bregma, and DV: 1–1.3 mm from cortical surface), and STN (AP: −3.8 mm, ML: 2.4 mm, DV: −7.5 mm). Tungsten microwires were connected to stainless steel screws on the skull bone above contralateral hemisphere as the reference ground. The location of STN electrodes was confirmed with the unique firing pattern during implantation38. For deep brain stimulation in STN, a two-channel connector with insulated stainless steel electrode (diameter 0.008 inch (203 μm), Plastics One) was used. One electrode was placed into STN at AP −3.8 mm, ML 2.4 mm, and DV −7.5 to −7.8 from the bregma ipsilateral to the 6-OHDA lesion side, and the other electrode was connected to a stainless steel screw on the skull of occipital bone. The recording tungsten microwires were pre-fixed at 0.3 mm anterior to the stimulation electrode before implantation for simultaneous stimulation and recording at STN.

In vivo electrophysiological recordings analysis

The electrophysiological signals were obtained from free moving rats during the open field test, with simultaneous video recording. The signals were sampled at 25000 Hz, amplified 1000x, and digitized with the recording system (A-M system). We further processed the signals with band-pass filters below 100 Hz for local field potential (LFP) and 300–3000 Hz for multi-unit or single-unit activities offline (Sciworks 10.0, Datawave Technology). The segments contaminated with muscle or mechanical artifacts during movement or high-voltage spindles at rest were not included for further analysis. The movement or mechanical artifacts were typically defined by: (1) waveforms with amplitude larger than ± 2 mV synchronously occurring in all electrodes in MC or STN, (2) waveforms with similar morphology synchronously occurring in all electrodes in MC or STN and associated with rat behaviors (e.g., bruxing, grooming, or licking), (3) known environmental artifacts marked during experiment26.

Local field potential analysis

For local field potential (LFP) analysis, the electrophysiological signals were down-sampled to 500 Hz by Sciworks software. Power spectral density (PSD) and time-frequency spectrum of LFP were derived from fast Fourier transform of the recordings using Welch’s method with hanning window, 1/2 overlap, and 0.5 Hz frequency resolution using pwelch function from signal processing toolbox in MATLAB (MATLAB R2018b, MathWorks). Average band power was computed by integration of the PSD estimates in specific frequency bands. PSD and band power were then normalized to the total power (1–100 Hz) and presented as the percentages of total to avoid influences by the variations of total power during the recordings.

Multi-unit and single-unit analysis

Recordings for multi- and single-unit analysis were processed offline by a spike detection software (Sciworks 10.0, Datawave Technology). We set the spike detection threshold at 4x of the estimate median absolute deviation of signals, σ (({rm{sigma }}=frac{{rm{median}}left(left|{rm{signals}}right|right)}{0.6745}) (1))102. For multi-unit (MU) analysis, all detects were included as spikes into a single cluster from each lead (electrode) in each segment. For single-unit (SU) analysis, detects from each lead were sorted into clusters with a Gaussian clustering algorithm according to the variation of spike waveform calculated by principle component analysis (PCA) in the Sciworks software. The minimal spike numbers in each cluster was 10. The clusters were also examined and confirmed visually by plotting in PC1-PC2 axes. Each detected spike was tagged with the cluster that it belongs to and aligned in time sequence (Fig. 4a, d). The SU spike variability in time sequence was calculated as: counts of change in the tag of cluster/spike count. The single-unit cluster number of spikes in each lead was counted. Spike amplitude was calculated by the valley voltage from zero using the “Parameter extraction” function of Sciworks software. The time-stamps of spike train were extracted from the Sciworks software and analyzed in the NeuroExplorer software (NeuroExplorer 5, Tex Technologies). Burst activities of SU in STN were defined as 4 consecutive spikes with an interspike interval less than 20 ms24.

Spike spatial dissimilarity analysis of multi-unit activities

We analyzed the spatiotemporal change of MU spike trains from the array of recording electrodes in MC by calculating the SPIKE-distance (S), a time-resolved measure of spike train dissimilarity, obtained by SPIKY, a MATLAB-based program developed by Kreuz et al. 103. The temporal profile of S (S(t)) was calculated by averaging the S(t) of all pairwise electrodes of the array. Only the leads with spike rate ≥ 5 Hz were included and only the segments with ≥ 5 included leads were included for dissimilarity analysis26. We extracted SPIKE-distance (S) from SPIKY and re-sampled the temporal profile of S (S(t)) forming a 500 Hz time series of data with interpolation method and the average were set to zero. The powers in frequency spectrum of S(t) were calculated by fast Fourier transform using Welch’s method with hanning window, 1/2 overlap, and 0.2 Hz frequency resolution in MATLAB. The total power of frequency spectrum of S(t) was computed by integration of all the PSD estimates and their corresponding frequencies.

Analysis of the locomotor activities in open field tests

A black Plexiglas box with 45 × 45 cm floor and 30 cm wall was applied as open field area. The area was equipped with a video recording and tracking system (Smart 3.0, Panlab Harvard Apparatus), surrounded by a black-out cloth and a Faraday cage to achieve a dark, noise-free environment. The variables from transient moving velocity were calculated by changes of the rat’s center of mass in the coordinates of each video frame at 16 fps captured by the Smart tracking software (Smart 3.0, Panlab Harvard Apparatus) into 1-second bins using MATLAB codes (MATLAB R2018b, MathWorks). Total distance of activities was defined as the total coordinate changes in a 5-min epoch of OFT (Fig. 1b–g and left upper of 6f). The total quiescent time was defined as the total time with transient moving velocity less than 2.5 cm/s (Fig. 1d, i). The propulsive behavior was defined as 3 continuous turns to the contralateral stimulation as well as the lesioned side during MCS viewed by visual inspection (Supplementary Fig. 1). The propulsive tendency was defined as 0.5 to 3 turns during MCS. Only the recordings not during propulsive behaviors were included for further analyses, so that the confounding effect from propulsive behaviors is excluded. In Fig. 1f, k, and Fig. 6f, contiguous bins with transient moving velocity ≤ 2.5 cm/s or > 4 cm/s with both start and end within in the 5 min epoch of OFT were collected into a quiescent or active moving episode, respectively. The minimal duration of each quiescent or active moving episode was set as 1 s. Duration and velocity of each episode, and counts of quiescent or active moving episodes in the 5 min epoch of OFT were also documented by MATLAB. For simultaneous behavioral and electrophysiological analysis (Figs. 2–6), we collected matched 10-second segments with continuous behaviorally “quiescent” (rest) or “active moving” (move) state by video inspection26. The whole recordings during MCS in a trial of OFT were examined, and the nearest segments with quiescent or active moving state were included as a pair for comparison. All pairs in a trial from each rat were included for analysis. The segments were further confirmed by velocity criteria calculated by video tracking system. Only those segments with average moving velocity > 4 cm/s (active moving) and ≤ 2.5 cm/s (quiescent) are included for further analyses. For stereotyped movement analysis, transverse and backward moving were defined as that the rat’s moving direction was vertical or reversed to the head’s direction, respectively. Transverse or backward moving for more than 2 steps was counted as a stereotyped movement. To analyze the electrophysiological recordings in stereotyped movement, 10-second segments of transverse or backward moving without interruptions of different movement were collected by visual inspection (Fig. 4g).

Motor cortex stimulation protocols

To evaluate the global effect on locomotor activities of MCS, we applied open field tests. To avoid epileptogenesis and stimulation-induced electrophysiological and behavioral noises, we applied DC current stimulation. We chose the unipolar configuration to assure an adequate and general coverage on the motor cortex. We tested from DC +1.1 to 1.9 mA with increment of 0.2 mA each time to find the threshold range, and found that there is a turning point with maximal total moving distance in open field tests (OFT) in the range of +1.5 to 1.9 mA in PD rats. In the following studies, we tested from +1.5 mA to 1.9 mA, and the DC current that induced the maximal total moving distance was defined as the most enhancement dose in PD rats. If +1.5 mA was the maximal dose, we also tested +1.3 mA in the subject. DC current larger than +2 mA was not applied considering animal health and safety. A total of 23, 4, 9, 23, 23, 21 trials for sham, +1.1, +1.3, +1.5, +1.7, and +1.9 mA were done in 23 PD rats. The average of the most enhancement doses is +1.7 ± 0.08 mA (mean ± 95% CI, n = 23 rats). In normal rats, there was no definite dose dependent effect from +1.3 to +1.9 mA. The “most enhancement dose” in normal rats was tested between +1.3 and +1.9 mA. Trials of OFT without noise in video tracking were included for analysis. A total of 20, 7, 19, 19, 16 trials for sham, +1.1, +1.3, +1.5, +1.7, and +1.9 mA were done in 20 normal rats. Each trial of OFT for MCS was constructed with 4 sequential 5-minute epochs. MCS was given for 5.5 min, but the results obtained at the first 0.5 min of MCS were not included for analysis (and thus skipped in figures) to prevent the interference with transient forelimb tremor-like movement or other artificial shocked response upon MCS. The four epochs are otherwise consecutive ones and are designated as “pre” (before stimulation), “MCS” (during stimulation), “post1” (0–5 min after stimulation), and “post2” (5–10 min after stimulation) (Refer to schematic drawings in Fig. 1a). Each normal or PD rat received at least one pre-test trial, followed by a series of trials with DC and sham stimulations of MCS. All trials were performed in the evening upon light-dark transition time, with an inter-trial interval of at least 24 h to avoid carry-over effect. Half of rats received sham stimulation before series of trials with MCS, and the other half of rats received sham stimulation after MCS.

Deep brain stimulation at the subthalamic nucleus

Unipolar deep brain stimulation at the subthalamic nucleus (STN DBS) with DC −200 to −300 μA was given to avoid the stimulating artifacts and assures an adequate and general coverage at STN in 12 PD rats (Fig. 6a, b)23,24. In the OFT, STN DBS was given in the 2nd epoch of the trials with the same procedures given with MCS (see above). The trials with the “most enhancement dose” (usually −250 to −300 μA) or the dose inducing maximal total moving distance in OFT were included for further analysis (Supplementary Fig. 4). For studies of dose-dependent effect of STN DBS (Fig. 6f), pulsatile stimulation at 100 Hz (pulse width: 100 µs) was given to simulate clinical settings in 6 PD rats. We tested the stimulating dose from −100 μA with 20 to 50 μA stepwise increments until the appearance of continuous turning in PD rats. The dose with maximal effect of STN DBS (100% I in Fig. 6f) in each rat was defined as the current that induces the maximal total movement distance but not continuous turning behaviors in OFT. Larger doses of STN DBS (e.g. 110–130% I) would usually induce more continuous turning behaviors but shorter total movement distance than 100% I. Lower doses of STN DBS (e.g. 70–90% I) would have a smaller effect on the locomotor activities in OFT. Only the rats tested with a complete dose range (~70–130% I) were included for analysis of dose-dependent effects. The first epoch of the first pre-test trial in OFT (1st time in OFT), and the epoch during sham stimulation (sham) of each normal rat were also included for comparison (e.g., Figure 6e, f).

Histological and immunohistochemical verification of the implanted electrodes and dopaminergic neurodegeneration

Rats were anesthetized with overdosed urethane (2 g/kg i.p., Sigma-Aldrich) and 5 ~ 10 mA of currents were given from recording electrodes for electrode coagulation to mark the recording site. The brain was then removed after transcardial perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The whole brain was immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 8 hours, and dehydrated with 20% sucrose at 4 °C for at least 2 days. Specimens containing MC, STN, SNc and the striatum were sliced coronally into thickness of 30 μm by a frozen microtome. The slices were stained with crystal violet (Nissl stain) for confirmation of the location of recording electrodes at MC and STN. The slices for immunostaining were washed with PBS, followed by a suppression procedure in 3% fetal bovine serum in 0.1% Triton. To confirm the neurodegeneration in SNc and the striatum by 6-OHDA, the slices were incubated with anti-tyrosine hydroxylase antibody (dilution 1:500, Sigma-Aldrich) overnight at 4 °C, followed by secondary fluorescent antibody (goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) highly cross-adsorbed secondary antibody, dilution 1:800, Invitrogen). The slices containing MC under the stimulating platinum plate were incubated with anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) antibody (dilution 1:500, Sigma-Aldrich) overnight at 4 °C, followed by secondary fluorescent antibody (goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) highly cross-adsorbed secondary antibody, dilution 1:800, Invitrogen) to evaluate possible local injuries from MCS. Images were taken using fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axiomager, M1) (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Electrophysiological recording in brain slices with electrical or optogenetic stimulation

Acute brain slices that preserve the majority of cortico-basal ganglia networks were prepared and recorded based on our previous works26,39,40. Briefly, the whole brain was taken from a wild-type C57BL/6 mouse or a Thy1-ChR2-eYFP transgenic mouse selectively expressing channelrhodopsin in glutamatergic neurons (aged postnatal days of 19–47). Parasagittal slices (270–300 μm thick) were prepared on a vibratome (Leica VT1200S; Leica, Nussloch) with an ice-cold choline-based cutting solution (in mM, containing 87 NaCl, 37.5 choline chloride, 25 NaHCO3, 25 glucose, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 7 MgCl2, and 0.5 CaCl2) equilibrated with 5% CO2 and 95% O2. The slices were incubated in the oxygenated cutting solution for 25 min at 30 °C and then transferred into an oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) solution (in mM, containing 125 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 25 glucose, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1 MgCl2, and 2 CaCl2) for 25 min at 30 °C before electrophysiological recordings. The primary motor cortex (MC) layer 5B, where pyramidal neurons and fast-spiking interneurons were identified based on the morphology and electrophysiological properties (refer to Supplementary Fig. 3 for details), was recognized according to the Allen Brain Atlas and the literatures104,105,106. Whole-cell current-clamp recordings from MC layer 5B neurons were performed using glass pipettes (2–5 MΩ) filled with the internal solution (in mM): 116 KMeSO4, 6 KCl, 2 NaCl, 20 HEPES, 0.5 EGTA, 4 MgATP, 0.3NaGTP, 10 NaPO4creatine, and pH 7.25 adjusted with KOH. The intranuclear stimulation was done with a pair of glass electrodes filled with ACSF, one being inserted into, and the other one placed above, the MC layer 5. Stimulation pulses were adjusted from 50 to 300 μA (pulse width: 0.4 msec) and delivered by a stimulus isolator (A356 or A360, World Precision Instruments, U.S.A.). Extracellular constant currents were delivered by another pair of stimulating electrodes filled with ACSF and placed near the recorded neuron. The stimulation was applied at a frequency of at least 0.04 Hz. For optical stimulation, the 470 nm light (1–3.5 mW, pulse width of 1 ms) was emitted by a solid-state laser diode (Newdoon Inc., China or Plexon Inc., U.S.A.) through an optical fiber (200 μm, NA = 0.22) placed onto the MC layer 5 and 500–800 μm away from the recorded neuron in Thy1-ChR2-eYFP mouse brain slices. Data were acquired using an Multiclamp 700B amplifier (MDS Analytical Technologies, U.S.A.) filtered at 1 kHz and digitized at 10–20 kHz by a Digidata-1440 analog/digital interface (MDS Analytical Technologies, U.S.A.). Constant bath flow of oxygenated ACSF with and without pharmacological agents (purchased from Tocris Bioscience, U.K. or Sigma-Aldrich, U.S.A.) during recording were controlled at a flow rate of ~5 ml/min by a peristaltic perfusion pump (Gilson MedicalElectric, Middleton, U.S.A.). The sample size denotes the number of neurons (with each neuron usually from a different mouse).

Statistics

Numerical data and statistical analyses were managed with SigmaPlot (Systat Software), Microsoft Excel (Microsoft), and SPSS 19.0 (IBM). Mann-Whitney U tests were applied for comparison of two groups between baseline (sham or pre) and stimulation (MCS or DBS), between different behavioral states (e.g. quiescence vs. active moving), and between normal and PD groups (Figs. 1, 2, 4g, 5, Supplementary Fig. 1, and Supplementary Fig. 6). To analyze both effects from baseline (sham or pre)/stimulation (MCS or DBS) and quiescence/active moving simultaneously, we applied 2 ×2 ANOVA followed by simple main effect tests with a significant interaction in main effects. When there is no interaction in main effects, we applied Student’s t test for comparing each level within the factors (Figs. 3, 4c, f, and 6a–d). For MU signals, dependent models and independent models of ANOVA analysis were applied for comparison between pre- and post-DBS and that between sham and MCS, respectively. For SU signals, independent models of ANOVA analysis were used. For comparison of single unit cluster number of each lead, we classified the cluster number into 3 groups (0, 1 and > 1), combing the segments of quiescence and active moving for the baseline (sham or pre) and stimulation (MCS or DBS) groups, and chi-squared tests were applied (Figs. 4b, e, g, 6b, and Supplementary Fig. 6b). In Fig. 6f, Friedman tests were applied in paired data in each subject with different stimulating doses for the dose-dependent effect within the groups of STN DBS and MCS. Comparison between control and STN DBS in PD rats was tested by Mann-Whitney U tests. Individual data from the dataset were present in Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8. All data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean (S.E.M.).

Responses