Mulched drip irrigation: a promising practice for sustainable agriculture in China’s arid region

Introduction

The cotton industry holds economic importance for China’s nationwide welfare and livelihood1. As China’s leading cotton-producing area, Xinjiang achieved a record output of 5.39 million metric tons in 2022, accounting for over 90% of national production and ~20% globally2. Characterized by large-scale, mechanized cultivation, Xinjiang’s concentrated cotton fields are notable for their high yields and consistent quality—critical factors in stabilizing China’s domestic cotton supply and international exports3. With such paramount contributions, ensuring stable cotton cultivation in Xinjiang remains a top priority in safeguarding a reliable supply both within China and globally4. As the primary cotton base satisfies much of worldwide demand, developments in Xinjiang’s agriculture system warrant close monitoring and support to sustain its leading role in cotton production5.

While Xinjiang plays a leading global role in cotton production, its arid oasis agroecosystems present persistent challenges, threatening agricultural sustainability6. The region faces extreme environmental stresses, including water scarcity and soil degradation that all hamper cotton industry7,8. Extensive saline-alkali soils, moreover, require continuous reclamation to increase arable land. Addressing these issues through effective mitigation measures is imperative, as the harsh local conditions endanger stable cotton cultivation9,10,11. Hence, only through systematic approaches addressing the region’s vulnerabilities, the cotton industry can endure environmental pressures and contribute to global demands. Strategies supporting arid-systems sustainable agriculture under such challenging conditions are the core of this research.

Mulched drip irrigation (MDI) was introduced in the 1990s to maintain ecological stability and mitigate soil salinization in cultivated areas of Xinjiang12. MDI offers unique water and salt management through efficient desalination, preventing deep percolation while retaining soil moisture13,14,15. Additionally, the mulch inhibits evaporation beneath its film and facilitates lateral salt movement away from crop roots. Such advantages have led to the widespread adoption of MDI as a cornerstone of ecological revitalization efforts in Xinjiang16,17. While MDI application has significantly improved production efficiency and economic benefits, ongoing debate surrounds its suitability for consecutive use on reclaimed saline-alkali fields18. To address concerns about long-term impacts, further research is needed evaluating MDI’s effects on soil salinity and crop productivity over time in fields reclaimed from saline-alkali land. As continuous MDI implementation expands, understanding its sustainability is essential for balancing agricultural and ecological outcomes in Xinjiang’s vulnerable agroecosystems.

While MDI offers benefits, its widespread adoption necessitates consideration of key long-term challenges. First, drip irrigation effectively supplies water and nutrients to crop roots and desalinizes the rhizosphere but does not fully remediate accumulated soil salt over time19,20. Second, extensive plastic mulch usage has led to rising residual film pollution, disproportionately impacting Xinjiang’s environment21. Third, prolonged drip irrigation may disrupt the plow layer encompassing microbiome communities and soil quality, questioning cotton’s sustained high yields on saline-alkali fields22,23. Thorough research is needed to address these issues and ensure MDI’s sustainable use in vulnerable regions like Xinjiang. Strategies must be developed to prevent soil salinization, mitigate plastic pollution risks, and safeguard microbial habitats and productivity on reclaimed lands. MDI’s role in cotton cultivation resilience could be optimized with careful management of accumulation, pollution, and microbial impacts. However, its widespread promotion necessitates solutions balancing agricultural benefits with ecological protection in sensitive agroecosystems.

Despite the growing implementation of MDI, a comprehensive evaluation of its long-term sustainability for continuous application and widespread promotion is still lacking in the current research field. We conducted an extensive 12-year investigation (from 2009 to 2020) with regular sampling of representative plots, analyzing over 45,000 soil samples. We integrated fundamental soil indicators within MDI cotton fields, focusing on salt, physicochemical properties, and microbial communities. Our study elucidates three critical aspects: (1) Mechanisms governing long-term salt migration patterns under MDI; (2) Successional changes in microbial communities and physicochemical properties of cultivated soils with long-term MDI; (3) Potential for sustainable agriculture in arid regions through MDI. By quantifying these factors, our analysis provides a holistic evaluation of MDI’s sustainability. With over two decades of continuous in-situ observation, this research addresses gaps in understanding impacts over extensive use timeframes. Our findings offer insights to guide appropriate management, ensuring environmental protection alongside agricultural benefits in vulnerable dryland systems.

Methods

Determining experimental domain and soil sampling

From 2009 to 2020, a study was conducted in the 18th regiment of the 121st battalion, situated in Pao Tai Town, Shihezi City, Xinjiang, using a “space-for-time substitution” approach24. Five different cotton fields within a ~2 km2 area were selected based on their initiation years of drip irrigation implementation: 2012, 2008, 2006, 2002, and 1998 (Supplementary Fig. 1). The underground brackish water, with an average salt content of 1.65 g/L, has been served as the irrigation source25; the ionic composition of irrigation water is included in Supplementary Table 1. All plots were originally uncultivated saline lands with similar soil properties. Each plot adopted a mulched drip irrigation (MDI) technology, ensuring uniformity in cotton variety, irrigation, and fertilization practices26. Specifically, the MDI durations for the five plots were 1 to 12 years, 3 to 14 years, 7 to 18 years, and 11 to 22 years, respectively. Consequently, it can be inferred that the MDI durations for these five plots may range from 1 to 22 years. The Google Earth was applied to locate the research plot (https://earth.google.com).

The disturbed soil samples were subjected to systematic sampling from April to February each year from 2009 to 2020, with a frequency of once every mid-month. For each field and during the cotton growth stage (From April to October), three specific points were meticulously selected at depths ranging from 0 to 140 cm below the soil surface: the location of drippers within the membrane, the precise midpoint of the narrow row of cotton plants, and the midpoint between the two outer individual membranes. During the non-growth stage (From November to March next year), soil sampling was conducted at 0 to 200 cm depth in the center and four additional corners of each representative plot. These soil samples were collected to analyze soil salinity.

The 10 cm × 10 cm × 10 cm undisturbed soil samples were collected at 10 cm intervals from 0–40 cm and 0–100 cm annually from 2009 to 2020 for each field (after cotton harvest). This sampling procedure was replicated five times in the center and four corners of the field. The collected soil samples were carefully placed into rigid plastic boxes and transported to the laboratory to determine soil stability, soil physiochemical properties (0–40 cm), and soil microbiome parameters (0–100 cm). Importantly, for the analysis of soil microbiome communities, the soil samples were promptly transferred to a low-temperature incubator immediately after collection and subsequently transported to the laboratory. To preserve the integrity of the samples, we carefully stored them in a refrigerator set at a constant temperature of −80 °C upon arrival at the laboratory.

Soil microhabitat quality data

The collected soil samples underwent a sequential processing protocol. Initially, a soil drying box subjected them to a drying process. Subsequently, the dried samples were further refined by passing them through a 1 mm mesh sieve. The sieved soil was then combined with distilled water at a specific mass ratio of 1:5. Following this, the mixture underwent vigorous agitation and filtration. The resulting extract required an electrical conductivity (EC) assessment employing a DDS-11A digital conductivity meter. To ensure precision in measurements, the EC values were meticulously calibrated using a drying technique and then converted into a mass fraction (g/kg) using the conversion equation: y = 0.008x + 0.876. Here, “y” represents salt storage, and “x” denotes electrical conductivity in micro-siemens per centimeter (µS/cm)27,28.

Soil microbial DNA was extracted from 0.5 g of freshly collected soil samples using the DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN, Düsseldorf, Germany). The quality and quantity of the extracted DNA were assessed with the NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and agarose gel electrophoresis to ensure its integrity for further analysis. For the amplification of the V5–V7 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was employed, utilizing the forward primer 799 F and the reverse primer 1193 R. Similarly, the fungal ITS1 region was amplified by PCR using the forward primer ITS1F and the reverse primer ITS2R. The thermal cycling protocol for amplification of both bacteria and fungi proceeded as follows: an initial denaturation step at 98 °C for 5 min, followed by denaturation at 98 °C for 30 s after 25 cycles, annealing at 53 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 45 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR amplicons were then purified using VazymeVAHTS™ DNA cleaning beads (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) and quantified with Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA reagent kits (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA)29,30.

After quantifying each sample, we pooled the amplicons in equal proportions. For the sequencing process, we utilized the MiSeq platform and MiSeq reagent kits v3, which were sourced from Shanghai Majorbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The sequencing was conducted in an end-to-end manner, resulting in paired-end reads with a length of 250 base pairs in both the forward and reverse directions. To maintain data integrity, the initial sequence data was subjected to a stringent quality filtering procedure using Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME) software (version 1.9.1) to minimize error rates. We also retained only sequences exceeding a length of 200 base pairs and displayed an average quality score of 20 or higher for subsequent analysis to ensure the highest data quality. After customizing primers and barcodes, the UCHIME algorithm was finally applied to identify and eliminate potential chimeric sequences. The superior-quality remaining sequences were processed using Mothur (version 1.21.1) to identify and quantify operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a 97% similarity level, following the methodology outlined by Schloss (2010). Finally, the OTUs were aligned and taxonomically classified using the SILVA Ref databases31.

Soil carbon and nitrogen content were quantified using combustion oxidation and the Dumas combustion methods, respectively. These analyses were performed using a carbon-nitrogen analyzer (CN-802, VELP, Monza, Italy). A similar approach to total carbon content analysis was employed to determine soil organic carbon content. Before analysis, a 2 mol L−1 HCl solution was utilized to eliminate the influence of inorganic carbon on the soil samples. The available phosphorus content was determined using the disodium bicarbonate method32.

Soil porosity was measured using a specialized soil three-phase meter33. Stable mechanical aggregates were further isolated through a quartering method and successive sieving using different hole diameters. The separated aggregates were dried and analyzed for their mean weight diameter (MWD) and geometric mean diameter (GMD) to assess their characteristics as follows34,35:

In the given equation, “xi” represents the average diameter of the ith aggregate (in millimeters), while “wi” denotes the proportion of the ith aggregate’s weight relative to the total weight (expressed as a percentage).

IBM SPSS Statistics 26 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was employed for conducting analyses, including variance (ANOVA), paired t-test, regression analysis, and path analysis. To compare significant differences among different groups, we utilized the least significant difference (LSD) test. Statistical significance was determined at the level of P < 0.05. The alpha-diversity indices of the soil microbial community were computed using QIIME, and distinctions in microbial communities among various samples were assessed through non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) based on the unweighted UniFrac distance, the Chaol index was selected to describe the diversity of the soil microbiome community.

Soil quality determination

To evaluate soil quality, the minimum dataset (MDS) and the total dataset (TDS) were employed36,37. In the first step, a normalization procedure using Eqs. (3) and (4) were implemented. This procedure utilized the max-min normalization technique to standardize the data from both datasets. By employing this normalization method, the soil quality assessments were conducted consistently and comparably.

The normalization procedure determined the membership value after normalization, denoted as Q(Xi), was determined. Here, Xij represented the actual value of the selected soil parameter, while Ximax and Ximin represented the maximum and minimum values within the corresponding group i, respectively. It is important to note that soil parameters such as soil bulk density, total porosity, and salt storage are negatively correlated with soil quality. Hence, these parameters experienced normalization using Eq. (3). Conversely, other soil parameters displayed a positive correlation with soil quality; therefore, their normalization is conducted using Eq. (4).

By conducting principal component analysis (PCA) and correlation analysis, redundant soil quality indicators were identified and subsequently eliminated, resulting in selecting the most informative parameters to form the minimum dataset (MDS). The relative importance of each soil parameter in the total dataset score (TDS) or MDS was determined by calculating its commonality ratio, representing the proportion of its commonality to the sum of commonalities derived from PCA analysis. Utilizing this weighted approach, the soil quality index (SQI) was then computed using Eq. (5), incorporating the relevant parameters from the MDS38.

In the equation, the weight of parameter i, denoted as Wi, is multiplied by the membership value of i, represented by Q(Xi). We then used Figdraw (figdraw.com) to construct our conceptual figures to demonstrate the soil quality evolution.

Results and discussion

Our study focuses on investigating five adjacent cotton fields within an area of ~2 km2. Our initial priority was to assess soil salinity to demonstrate the sustainability of MDI, as elevated salinity in the cultivation layer adversely influences the uptake of nutrients by crop roots39. Subsequently, we examined the response of soil nutrients to successive MDI applications, given that variations in soil nutrient content can significantly impact the microbiome community structure40. Last, we analyzed shifts in soil microbiome composition after the long-term application of MDI. By integrating essential ecological indicators, our study aims to comprehensively evaluate evolutionary trends in soil quality within cotton fields.

Assessment of soil salinity variation

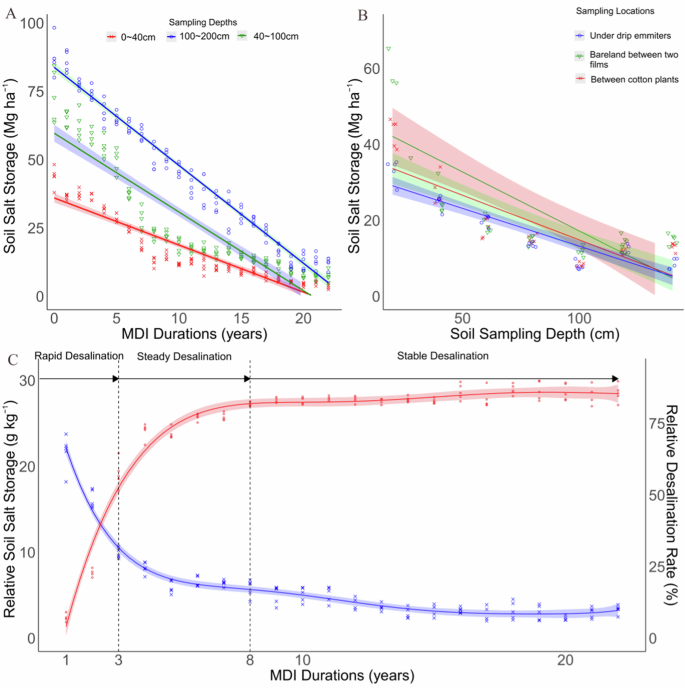

We conducted soil sampling during two distinct periods: from April to October, representing the cotton growth stage, and from December to February of the subsequent year, corresponding to the non-growth stage. The sampling methodology is detailed in the Methods section. Throughout the non-growth period of cotton, a notable reduction in soil salinity was observed across all sampling depths (0–40, 40–100, 100–200 cm), and this decline became more pronounced with the extension of the MDI application year. Interestingly, we observed a gradient of salinity accumulation from the surface toward the deeper soil layers during this stage (Fig. 1A). During the growth stage of cotton using brackish underground water for irrigation25, soil salts migrated toward the wetting front, leading to their vertical movement and the development of a low-salinity environment in the root zone. This process resulted in a progressive vertical displacement of salt distribution into deeper soil layers, exhibiting a noticeable desalination effect from the cotton seedling stage to the cotton boll opening stage. At the same time, salts gradually migrated horizontally toward the two individual films, leading to salt accumulation on the exposed soil surface through evaporation (Fig. 1B). This phenomenon, commonly called “salt surface accumulation,” differs from a secondary salinization process. Instead, it emerged as a direct consequence of salt migration towards the soil-mulch interface.

Spatially, A has depicted the overall distribution patterns of soil salinity during non-fertility (farrow) periods in the cotton fields over the MDI application years; moreover, the migrating patterns during the cotton growth period are demonstrated in (B). Temporally, C shows average relative salt storage in the root zone of cotton plants, which has featured a power function relationship with the increasing duration of drip irrigation, demonstrating a decreasing trend year by year.

Consequently, the mean relative salt storage values under MDI exhibited a power function relationship, characterized by an initial pronounced decrease followed by a gradual decline over time. After three years of MDI, soil salinity decreased significantly compared to the adjacent wasteland, with a desalination rate exceeding 60%, indicating a stage of rapid desalination. From three to eight years of MDI application, the desalination rate displayed a linear increase, reaching a peak of 80%, indicating a period of steady desalination. Beyond eight years up to 22 years of MDI application, the desalination rate stabilized at 80–90% (Fig. 1C). Thus, prolonged MDI application lowered salinity levels in the cotton field, while the extent of salt salinity reduction diminished over time, eventually reaching dynamic equilibrium.

Our study has revealed significant implications of the current MDI system in leaching soil salinity, as evidenced by a gradual decrease in salinity within the cultivated layer (Fig. 1C). The evolution of soil salinity transport from micro-scale to macro-scale was influenced by the spatial heterogeneity in the pore systems of the converted soil under long-term MDI41. Notably, soil salt migration was primarily impacted by soil spatial heterogeneity, mainly through the irrigation quota of MDI42. Therefore, the convective effect of salt migration prominently resulted in shifting longitudinal migration43, with the fastest migration under drip emitters and progressively slower away from them. As spatial and temporal scales enlarged, periodic irrigation under MDI promoted macro-uniformity within the soil pore systems, wherein lateral dispersion increasingly compensated for salt concentration in the horizontal direction44. Consequently, increasing the amount and frequency of drip irrigation can effectively suppress soil salinity, driving it deeper or even rinsing it off. These findings support the feasibility of continuing MDI due to its effective salt-reduction effects.

Proper implementation of MDI is crucial for sustainable agriculture in Xinjiang and other oasis agroecosystems globally. Ongoing research remains essential to understand the effects of MDI-induced soil salinization in regions like Xinjiang, the Middle East, India, and Central Asia, where the enriching rate of salinity surpasses the leaching rate45. Hence, to secure lasting efficiency in water utilization and to manage soil salinity effectively, it is imperative to conduct rigorous field tests across diverse soil and climatic scenarios with consistent application of MDI. These tests ensure the promotion of the long-term sustainability of MDI, thereby fostering sustainable agricultural practices, particularly in regions facing water scarcity.

Evolution of soil physiochemical properties

To assess the long-term sustainability of MDI practices, we thoroughly examined the soil’s physical structure and nutrient composition. During each irrigation year, soil samples were collected at different depths (0–40 and 0–100 cm). This allowed us to evaluate soil stability within the cultivation layer and determine total soil porosity, soil bulk density, and soil nutrient storage after long-term cultivation, tillage operation, and MDI applications.

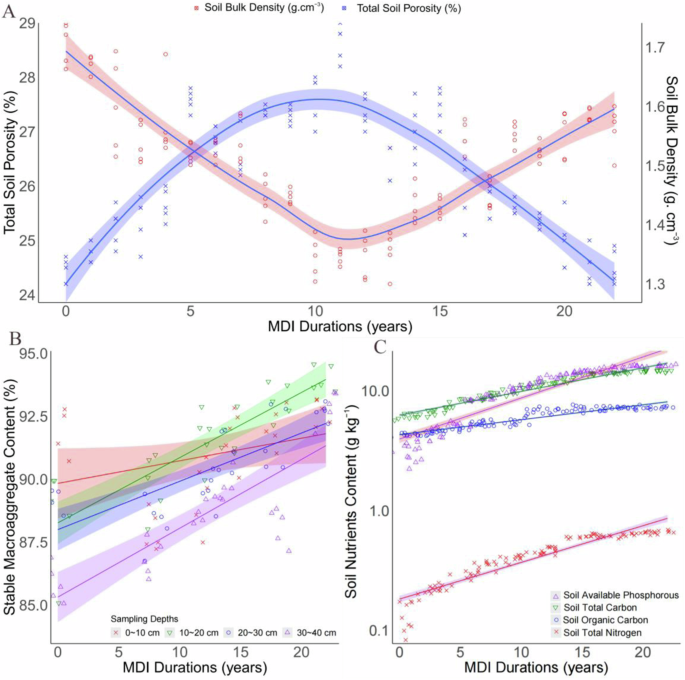

The results indicated that the proportion of large aggregates in cotton fields increased, improving mechanical aggregate stability at all sampling depths (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, although soil bulk density initially decreased after starting MDI, this trend reversed after a decade of MDI practice. Conversely, total porosity displayed an opposite trend (Fig. 2A). Moreover, long-term MDI positively influenced soil nutrient reserves, with the total nitrogen content in the cultivation layer steadily accumulating over the years (Fig. 2C). Additionally, total soil available phosphorus and carbon content in the cultivation layer (0–40 cm) in long-term MDI cotton fields were 2.86–7.66 and 3.81–5.53 times higher, respectively, compared to native soils. Also, soil organic content in cotton fields under MDI ranged from 3.92 to 6.03 g/kg, surpassing that observed in unirrigated soil (3.51 g/kg).

A showcase of how soil total porosity and soil bulk density vary with the consecutive application of MDI. B has presented the increasing soil stability over the MDI applications. We have also found the same augmenting trend of soil nutrient content during constant MDI durations, which will be seen in (C).

Long-term practice of MDI significantly enhanced soil nutrient accumulation and improved the formation of soil aggregates. Machine deep tillage to 40 cm after cotton harvest was crucial in preparing the land for long-term MDI, leading to explicit alterations in soil structure46. Consecutive mechanical operations were primarily responsible for disrupting soil compaction, resulting in a considerable decrease in soil bulk density and an increase in soil total porosity37,47,48. Long-term MDI also increased the soil organic matter content (Fig. 2B). However, soil bulk density exhibited an upward trend after ten years of continuous MDI, possibly due to the accumulation of residual plastic film after long-term mono-cropping practices. The residual plastic film in the continuous MDI cotton field ranged from 121.85 to 352.38 kg ha−1 with an annual increase of 15.69 kg ha−1 at a soil depth of 0–30 cm49.

Fortunately, positive indications were observed regarding the stability of soil aggregates and the proportion of macro-aggregates after long-term MDI, mainly attributed to amendments in irrigation practices. The presence of sodium ions in saline-alkali soils reduces cohesion among soil particles; however, irrigation-induced leaching of sodium ions from the topsoil contributed to enhanced aggregate soil stability50. Furthermore, the proportion of macro-aggregates and the stability of soil aggregates improved, which can be attributed to increased soil organic carbon resulting from long-term fertilization and cropping techniques. The above findings demonstrate that MDI has significantly improved soil stability, enhanced nutrient storage, and overall soil health, making it a promising and sustainable practice for continuous agricultural application.

The successful implementation of MDI in cotton fields has revolutionized the productivity of once barelands, converting them into rich, arable soil. This transformation has notably enhanced the growth of cotton in saline-alkali environments, marking a significant stride in sustainable agriculture practices. Nonetheless, it is crucial to tackle potential risks, including soil compaction, clay particle aggregation, and soil degradation, which are linked to long-term MDI cultivation. Subsequent research must concentrate on mitigating these concerns to ensure sustainable agricultural practices within oasis agriculture systems.

Soil microbiome variations

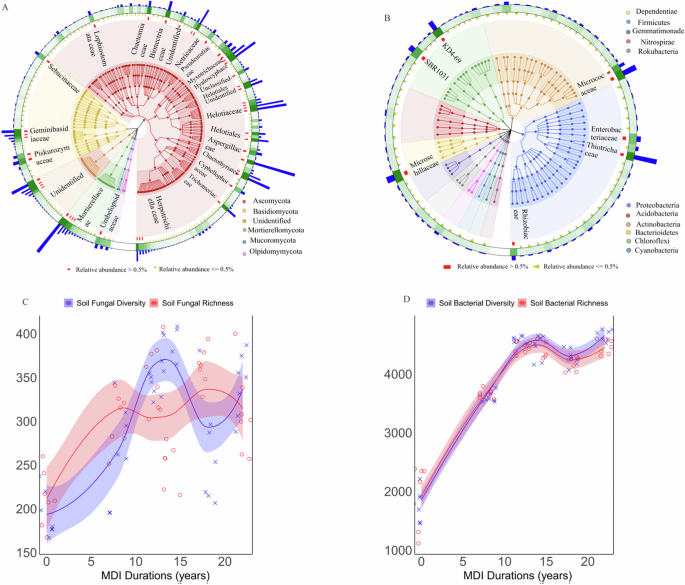

To investigate the evolving characteristics of the soil microbial community under long-term MDI practices, soil samples were collected at a depth of 0–100 cm (see detailed description in the Methods section) and stored in a refrigerator at a constant temperature of −80 °C. The soil bacterial community, comprising 5752 Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs, Supplementary Table 2), exhibited a reduction in sequences from 35,640 (in the saline wasteland) to 26,616 (22 years of MDI application). After 22 years of MDI application, the dominant beneficial bacterial genera (>0.01%) were Gemmatimonadetes (5.83%), Actinobacteria (35.23%), Chloroflexi (24.34%), Proteobacteria (35.92%), and Acidobacteria (6.04–15.13%) (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. 3). Additionally, the average relative abundance of these premium bacterial groups increased. The soil fungal community was classified into 628 OTUs, with sequences ranging from 58,933 (in the saline wasteland) to 57,494 (22 years of MDI application). The main beneficial soil fungal phyla (>0.01%) were identified as Ascomycota (84.84–98.72%), Mortierellomycota (4.24%), and Basidiomycota (4.54%), which remained relatively stable over the study period of long-term MDI practices (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Fig. 2). The average relative abundance of the major fungal species, representing 21.82–68.96% at the genus level, increased by 43.63% with the extension of MDI years. Furthermore, the diversity of soil communities also increased with the continuous durations of MDI (Table S2). Among the bacterial and fungal communities, the Chaol indices demonstrated positive correlations with the years of practicing MDI, reaching a stable stage after ten years of MDI. (Fig. 3C, D).

The composition of soil fungal (A) and bacteria (B) after 22 years of conversion from natural land to cotton fields with long-term MDI application is presented. Notably, the results have been presented exclusively for relative abundances exceeding 0.5%. The full information is available in Supplementary Figs. 2, 3. Moreover, C, D denote the alpha-diversity (Chaol index) and richness of the soil microbial community in response to the prolonged MDI practice.

The prolonged use of MDI has enhanced the microbial communities within field soils. This is primarily attributed to the cumulative impacts of serial MDI applications, which have modified soil structure and concentrated soil nutrients, rendering the cotton field more vulnerable to interactions with the soil microbiome. Yet, after 15 years of MDI application, the richness of the beneficial soil microbial community has stabilized, which may lay on the allelopathic influence of cotton root exudates with increasing MDI implementation33. In addition, the cotton-monocrop system inherently initialized the configuration of self-toxicity, directly affecting the soil fungal diversity indices51. Beyond that, constant agronomic activities, fertilizer input, pesticide and herbicide application, and uninterrupted production also imposed limitations on the development of soil microbial and soil microorganism activities52,53. But in the long run, MDI still has the worthiness of continuous use with the positive function of upgrading the soil moisture-fertilizer-gas conditions in cotton fields.

Furthermore, the observed evolutions were attributed to the rise in crop residues within cotton fields under prolonged MDI54. The soil environment became favorable for mycelia growth as the external environmental conditions were refined and offered additional space for other organisms, increasing competition among fungi for limited resources42. Therefore, the long-term application of MDI can establish a more resilient and stable soil organism community in cotton field soils, supporting sustainable and productive crop production systems.

Long-term adoption of MDI significantly influences soil microbial communities in agricultural fields, affecting their diversity, population structure, and functionality. MDI fosters microbial diversity by providing an optimal soil microhabitat with fractional irrigation, leading to a wider range of microbial species and functional groups. Additionally, MDI selectively shapes the composition and abundance of microbial populations by delivering water and nutrients precisely to the root zone, favoring specific microbial taxa and influencing the overall community structure over time. Moreover, MDI enhances the functional capabilities of soil microbes through improved water and nutrient availability in the root zone, stimulating crucial activities like nutrient cycling, organic matter decomposition, and disease suppression. These beneficial effects enhance soil health, nutrient availability, and ecosystem functioning in agricultural systems. Understanding the microbial responses to MDI offers valuable insights for sustainable soil management and optimizing agricultural practices.

Soil microhabitat quality changes

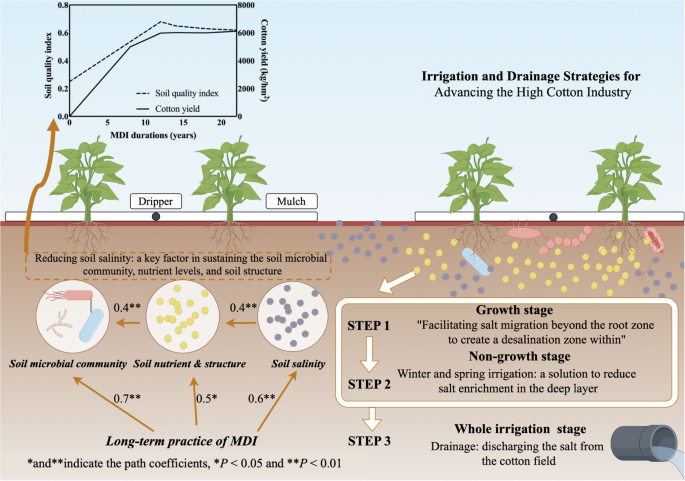

Over an extended period, the soil salinity has decreased, and the soil beneficial microbat and soil nutrients have accumulated, ultimately contributing to a steady and progressive increase in cotton yield (Fig. 4). In the initial phase, encompassing the first 14 years, a progressive amelioration of the soil microhabitat quality was observed. This could be attributed to the establishment and maturation of the MDI system, fostering a more efficient water and nutrient distribution throughout the cotton fields. Consequently, soil fertility was bolstered, providing a favorable environment for root development and crop growth. During the next 14 to 22 years, the soil microhabitat quality stabilized. During this phase, the soil achieved a relatively balanced state, signifying the establishment of a harmonious ecosystem within the cotton fields. The stabilization can be attributed to the soil’s natural adaptation and self-regulation mechanisms, which, over time, adapt to consistent drip-irrigation practices and agronomic management. As a cumulative result of this dynamic evolution in soil microhabitat quality, the cotton yields exhibit a remarkable consistency and gradual increase over the 22 years. The enhanced soil conditions and optimized water and nutrient supply through drip irrigation created an ideal environment for cotton cultivation, yielding bountiful and sustainable crop harvests. In conclusion, the findings underscored the long-term positive impact of MDI on soil microhabitat quality, leading to a persistent and ascending cotton yield. This study sheds light on the critical role of MDI in efficient water management and sustainable agricultural practices in ensuring food security and agricultural productivity on a global scale.

Furthermore, we have proposed an efficient water-saving and salt-control technology system tailored specifically for the cotton industry in arid China comprising three key steps: Step 1 involves optimizing the drip irrigation system to facilitate salt migration away from the root zone, thereby creating a desalination zone for improved nutrient uptake and a thriving microbial community; Step 2 focuses on refining winter and spring irrigation management to mitigate salt accumulation in the deeper plow layer; Step 3 incorporates measures such as covering pipes, open ditches, and shafts to facilitate the discharge of salt from the farmland (This figure is conceptualized and incorporated through Figdraw (figdraw.com)).

In response to the requirements of an increasingly water-scarce environment, we have introduced a novel and highly effective water-saving and salt-control technology system specifically designed to cater to cotton cultivation. Our proposed system represents a significant advancement in sustainable agricultural practices and addresses the continuing concerns about water scarcity and soil salinity. First, the system comprises salt flushing during the cotton growth phase, wherein controlled amounts of water are strategically applied to flush excess salts away from the root zone, thus fostering improved water uptake and nutrient absorption by the cotton plants. Second, our system implements salt leaching techniques during non-growth periods, effectively reducing soil salinity levels and preventing salt accumulation in the root zone. Last, the technology incorporates a meticulously coordinated irrigation and drainage strategy to facilitate salt removal from the fields. By regulating the timing and frequency of irrigation and drainage cycles, we can optimize the balance between soil moisture and salt content, enhancing overall cotton growth and quality. Our water-saving and salt-control technology system represents a pioneering step towards sustainable cotton cultivation, demonstrating environmental responsibility and economic viability. By adopting these innovative practices with MDI practices, cotton producers can contribute to water conservation efforts while ensuring the long-term stability and productivity of cotton production.

The enduring application of MDI technology has positive impacts on agricultural soil environments, which fosters agricultural sustainability by improving water and nutrient efficiency, minimizing soil erosion, enhancing soil structure, boosting water retention capacity, and reducing salinity levels. Significantly, the interdependent and collaborative evolution of these indicators necessitates further research to substantiate our conclusions42. To maintain the continued function of MDI in oasis agriculture, integration with other water management practices is also crucial. Such practices include effective water source management, optimized water distribution systems, and soil management techniques such as conservation tillage and cover cropping. Regular monitoring of soil health indicators is also essential. By combining MDI with these strategies, the sustainable utilization of water resources and soil conservation can be realized, ensuring the long-term viability of oasis agriculture systems.

Further demonstration

While MDI has indeed illustrated effectiveness in water conservation and the consistent enhancement of crop yields in arid oasis regions, the ongoing concerns associated with the accumulation of residual plastic film present significant environmental challenges that must not be neglected55. Notably, these residual films are predominantly distributed within soil depths of 5–15 cm and have been accumulating at an annual rate of 15.69 kg/ha, attributed to continuous mulching practices56. However, our sampling processes primarily centered on soil quality evolutions, with comparatively less emphasis placed on the dynamics of residual film accumulation.

Despite the challenges posed by residual film pollution, soil quality has nonetheless exhibited a positive trend, a testament to the effectiveness of current agricultural practices. Particularly in arid regions like Xinjiang, which serve as pivotal cotton production bases, the film-mulching technique is essential57. This practice plays a critical role during the cotton seeding period, which is crucial for determining the plant’s growth trajectory and eventual yield. Premature seeding, subject to low soil temperatures, can impede seed germination and increase the risk of damage from late frosts. On the other hand, delaying seeding may accelerate seedling emergence but can lead to postponed boll opening and, ultimately, lower yields. Fortunately, mulching techniques have successfully mitigated these issues by enhancing early soil temperatures and the overall heat accumulation, offering a significant advantage over non-mulched fields in the inland northwest cotton production regions.

Efforts to mitigate the impact of residual film pollution have been extensively implemented across Xinjiang and other arid regions57. This comprehensive approach encompasses legislation, the promotion of biodegradable films, and the mechanical recycling of used plastic films as part of a systematic endeavor to address pollution. Furthermore, the adoption of thicker (greater than 0.015 mm), high-strength reinforced films has been advocated to enhance the recyclability of these materials from the outset. In addition, strategies for residual film pollution have been refined, with differentiated treatments being applied based on precise classifications. To enhance the efficiency of these measures, the operation of surface residual film recovery machinery has been optimized, resulting in increased efficiency in removing residual films and a higher operational frequency. As a result of these concerted efforts, Xinjiang now boasts a mulch film recovery rate exceeding 90%, with the recovery rate for topsoil residual film surpassing 20%. Importantly, the complete recovery of residual film from cotton fields has been achieved, ensuring the sustainable use of MDI in the long term.

By discussion of the foregoing, the durable application of MDI has demonstrated multiple positive impacts on soil salinity management, nutrient storage enhancement, soil structure stability, and microbial community composition. Over a period of 0 to 14 years, the soil quality in cotton fields irrigated continuously with MDI has displayed a notable improvement across all these indicators, followed by a sustained trend from 14 to 22 years. Our research aims to alleviate doubts or concerns surrounding the potential for widespread and sustainable implementation of this water-saving technology in arid oasis agricultural areas. We firmly believe that MDI technology holds the potential for sustained and extensive promotion in arid oasis agricultural regions over the long term.

Responses