Multiscale perspectives for advancing sustainability in fiber reinforced ultra-high performance concrete

Introduction

Concrete, a widely employed construction material, exhibits inherent limitations such as low tensile strength, brittleness, insufficient strain capacity and strain capacity1,2,3. To address these concerns, the reinforcement of concrete with diverse fibers, including metallic, synthetic, carbon, and mineral fibers, has been pursued to augment its toughness. In response to the growing demand for high-strength and durable concrete, a type of advanced fiber-reinforced concrete was developed in the mid-1990s that has been titled ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC)4. UHPC features the high-density microstructure and mechanical properties which possess compressive strength above 150 MPa and flexural strength over 50 MPa5,6,7. UHPC also demonstrates exceptional hardened and durability properties, including remarkable self-compactness properties, enhanced structural ductility, pseudo-strain hardening behaviors, bond strength, as well as superior resistance to aggressive environmental conditions than normal concrete8,9,10,11. UHPC consists of a large volume of cement, silica fume, fibers, superplasticizers and other supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs), which formulation aims to improve toughness, durability, homogeneity, and reduce porosity12,13,14. Different from normal FRC, UHPC is designed by the dense packing theory of solid materials, involves a high cement content with the low water-to-binder (w/b) ratio, and micro-scale fibers14. Given UHPC’s efficient resource utilization and reduced maintenance requirements, it emerges as a plausible strategy for mitigating the adverse effects associated with conventional construction methods. Although the energy and economic costs of UHPC are high, the high initial investment would be offset by the reduction of maintenance costs as UHPC has better properties than conventional concrete and a longer service life15,16. Given UHPC’s exceptional strength-to-weight ratio, it emerges as an economically viable choice for the design and construction of new concrete structures17. This characteristic enables the reduction in the size of structural members and the increased spacing between them, as well as the potential for the restoration of pre-existing buildings18. Hence, the overall cement consumption during construction is reduced. Reducing cement usage in UHPC not only significantly contributes to cost and CO2 emission reductions but also promotes sustainability in the construction sector by minimizing environmental impacts and providing eco-efficient construction materials19.

Enhancing the performance and managing costs of UHPC has long been a focal point of existing studies. The pursuit of performance improvement involves the removal of coarse aggregates, incorporating advanced additives, using high-range water-reducing admixtures, and optimizing mix proportions and the granular matrix. These efforts are aimed at improving the mechanical properties, durability, and sustainability of UHPC, thereby expanding its potential applications in various structural and infrastructure projects. Moreover, the broader utilization of UHPC in the construction industry has been limited by its relatively high initial cost. Ongoing investigations are actively addressing knowledge gaps and paving the way for the development of innovative UHPC formulations that offer reduced initial costs. Concurrently, the elevated cost of UHPC raw materials and the intricate curing process involving steam or extreme heating necessitate substantial energy consumption. This notable energy demand significantly contributes to the higher price associated with industrial manufacturing of UHPC compared to water curing. Therefore, extensive efforts are required to address these challenges, starting from the optimization of UHPC’s composition and concluding with the development of energy-efficient and cost-effective production processes for UHPC to improve its sustainability and durability.

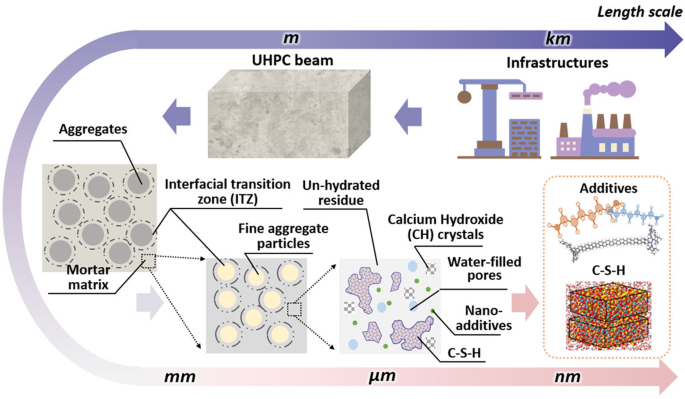

The development of multiscale mechanical theories and modeling techniques specific to UHPC is crucial and foundational for advancing UHPC towards greater sophistication, sustainability, and environmental friendliness20,21. The performance of UHPC is closely related to the content, properties, distribution patterns, and interface characteristics of its various components22. With the advancement of manufacturing techniques and the development of nanotechnology23,24, the introduction of micro- and nano-scale components has further enhanced the performance of UHPC, while simultaneously enriching its composition and increasing the complexity of its hierarchical structure as shown in Fig. 1. For such complex cementitious composite materials, the conventional continuum mechanics theory struggles to account for their intricate features, while the suitable range of scales for applying the micromechanics approach remains to be explored25,26. Therefore, the efficient and accurate prediction of the macroscopic performance of UHPC based on its micro- and nano-scale information, as well as the design and optimization of its micro- and nano-structure according to the required macroscopic performance for practical applications27, has become a pivotal topic in UHPC-related research. Hence, it is imperative to have multiscale perspective in the investigation of the sustainability and durability of UHPC, aiming to establish quantitative relationships between its macroscopic performance and the nano-, micro-, and other hierarchical structures. Multiscale mechanics methods rely on the microscopic structural information of materials. Currently, the available methods for mechanical analysis at the microscopic scale include first-principles calculations and Molecular Dynamics (MD). Among them, MD is a nanoscale simulation method based on interatomic interactions28,29. Extensive research has demonstrated that MD simulations can effectively elucidate deformation and failure mechanisms of materials30,31,32,33,34, thereby establishing a crucial physical foundation for cross-scale mechanical analysis35. For bridging atomistic scale to continuum scale, the quasi-continuum method36, the handshake method37, and the coarse-grained (CG) method38 are widely employed.

UHPC is a representative heterogeneous material, exhibits distinctive structural characteristics under different length scale.

We systematically review the recent progress in advancing sustainability in UHPC under multiscale perspectives, with an emphasis on how multiscale theories and modeling techniques address the challenges in the ecological considerations of UHPC. We first summarize the fundamentals of UHPC and discuss the influence of fiber types (i.e. steel, carbon, mineral, cellulose, synthetic) and geometric characteristics (i.e. length, shapes, distributions, and orientations of fibers) on the properties of UHPC39. Based on the peculiarities of the sustainability of UHPC, special attention has been given to the applications of multiscale theories and modeling techniques in emerging low-carbon strategies and sustainable design. Finally, we identify areas in which multiscale techniques have the potential for accelerating sustainable research and consider the ecological developments of UHPC in practical applications.

Fundamentals of fiber-reinforced UHPC

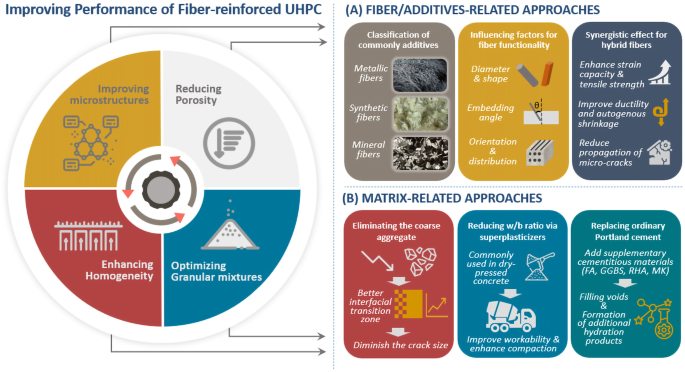

Basic principles for improving performance

Significant advancements and refinements have been made in the fundamental principles of UHPC architecture over the past few decades, laying a solid foundation for its further development4,40. With the continuous advancement of relevant research, UHPC is widely applied due to its exceptional performance and the versatility of additives that can be utilized to enhance UHPC properties and overcome its limitations. The fundamental philosophy of enhancing its performance encompasses reducing the porosity, improving the microstructures, enhancing homogeneity and optimizing granular mixtures, as shown in Fig. 241,42. These factors are highly dependent on the raw materials and mixture design of UHPC.

A Fiber/additives-related approaches; B Matrix-related approaches. To reduce the porosity and improve the microstructure of UHPC, optimal mixture proportion designs should be developed, including application of fibers and mineral additives. To enhance homogeneity and optimize granular mixtures, approaches include eliminating the coarse aggregate, reducing the w/b ratio via superplasticizers, as well as replacing ordinary Portland cement with supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs).

To reduce the porosity and improve the microstructure of UHPC, optimal mixture proportion designs should be developed43,44. The commonly used strategy involves relies on application of fibers and mineral additives, which can create the matrix with low porosity, higher strength, better failure behavior, and improve compressive strength of UHPC to 150–200 MPa29,45,46,47,48. The used fibers for the development of UHPC are summarized in Table 1, which evaluates the tensile strength and Young’s modulus of different fibers employed in concrete, providing a comparative analysis49,50,51. Although dozens of different fibers are used in UHPC, they can generally be divided into three types based on texture: metallic fibers (i.e. steel fibers), synthetic fibers, and mineral fibers52. Among those, steel, polyethylene (PE), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polypropylene (PP), carbon, and basalt are the prevailing fiber types employed in UHPC. In metallic fibers, steel fibers are regarded as the optimal choice for reinforcing UHPC, which exhibit exceptional stability under ambient temperature coupled with high Young’s modulus and tensile strength53. Synthetic fibers, including PVA fiber, PP fiber, and PE fiber, exhibit lower tensile strength than steel fibers, thereby limiting their efficacy in enhancing tensile and compressive strength of UHPC54. Nevertheless, they have the capability to enhance volume stability55 and fire resistance56 of UHPC. With the superior Young’s modulus and tensile strength, carbon fibers are able to enhance the mechanical characteristics of concrete while mitigating autogenous shrinkage57. This improvement can be achieved with a minimal dosage of carbon fibers57,58,59. The incorporation of 0.3 vol% carbon fibers resulted in a notable enhancement in the tensile strength and energy absorption capacity of UHPC in the existing study. Specifically, tensile strength of UHPC has increased 54.9 % from 5.87 MPa, along with an improvement of 108.9 % from 3.82 J regarding the energy absorption capacity57. Detailed discussions on the effect of different fibers will be provided in Sections “Basic principles for improving performance” and “Influencing factors for fiber functionality”.

To enhance homogeneity and optimize granular mixtures, several methods should be considered which include eliminating the coarse aggregate, reducing the w/b ratio via superplasticizers, as well as replacing ordinary Portland cement with SCMs (e.g., fly ash (FA), ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS), rice husk ash (RHA), metakaolin (MK))60,61,62. The mechanical and thermal characteristics of the cementitious matrix and aggregates in the conventional concrete are different, resulting in varying tensile and shear stresses within the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) and subsequently leading to microscopic cracks that are proportional to aggregate sizes1,63. Therefore, reducing the size of aggregates in UHPC can diminish the crack size64. This observation highlights an increase in the homogeneity of UHPC mixtures. Besides, the addition of SCMs contributes to the refinement of the UHPC microstructure by filling the voids between cement particles and acting as nucleation sites for the formation of additional hydration products65. This leads to a denser and more compact microstructure, resulting in improved mechanical properties. By reducing water demand, SCMs also enhance workability and cohesiveness, while their reaction with calcium hydroxide forms additional cementitious compounds, resulting in improved strength and durability60,61,62.

Influencing factors for fiber functionality

As discussed above, the mechanical strength of UHPC can be improved by using fibers. These fibers bridge cracks and transfer stress between fiber and matrix, which capacity of fibers can be determined by bonding properties between fiber and matrix66,67,68. The fiber/matrix bonding performance can be quantitatively determined by peak load measured in the single fiber pull-out test69,70. During the pullout process, three resistance mechanisms are summarized that contains chemical adhesion, friction resistance, and mechanical anchorage, which is influenced by the diameter and shape of fibers71,72,73. Specifically, the behavior of straight steel fibers during pullout can be divided into three stages: (1) initial load development without relative slip, (2) partial debonding resulting in a peak pullout load due to static friction and chemical adhesion, and (3) complete debonding and slip caused by dynamic friction. The pullout load decreases as displacement increases until complete separation, with friction resistance being the primary factor. Compared to straight fibers, hooked-end fibers exhibit an ongoing increase in pullout load by providing mechanical anchorage when passing through matrix. Consequently, mechanical anchorage and friction resistance emerge as two critical mechanisms that determine the pullout behavior of the hooked-end fibers74,75. Regarding the inconsistent resistance mechanism of fibers with different shapes, bond strength of steel fibers can be categorized as follows: straight fibers exhibit the lowest bond strength at 6 MPa, while half-hook end fibers show a strength of 12.5 MPa, hook-end fibers demonstrate a range of 20.6 MPa to 23.5 MPa, corrugated fibers reach 33.3 MPa, and twisted fibers exhibit a strength range of 19.9 MPa to 47 MPa76,77.

The bonding strength between fiber and matrix in UHPC is also influenced by the fiber embedding angle and the matrix curing method. To balance synergistic effect of snubbing, matrix spalling, as well as fiber slip capacity, the maximum average bond strength was observed when an embedded angle ranging from 30° to 45° was employed78,79,80. In addition, experimental observations revealed that under standard curing conditions, UHPC exhibited smooth fiber surfaces76. However, in UHPC cured in autoclaves, residual cement paste adhered to the fiber surfaces, indicating an enhancement in chemical adhesion at fiber/matrix interface when UHPC cures under higher temperatures81,82,83. For straight steel fibers, the bonding strength can be increased from 5.4 MPa to 14 MPa76.

Optimizing the orientation and distribution of fibers can improve mechanical behavior of UHPC84,85,86. The researchers have noted a 65% increase in bond strength when angle of fiber orientation angle varied from 0 ° to 45 °, due to supplementary frictional shear resistance provided by the inclined filaments87. By employing a 3D orientation analysis method utilizing X-ray CT techniques, researchers have established a robust linear correlation between the flexural strength of UHPC, the fiber orientation factor, and fiber quantities present at crack surfaces, which are closely tied to fiber distribution88. Fiber orientation analysis allows estimation of degree of fiber alignment along tension direction; higher fiber orientation indicates more fibers aligned in tension direction. This alignment effectively restrains crack propagation, resulting in increased strength14,85,89.

Synergistic effect for hybrid fibers

Different fiber types have different enhancement effects and mechanisms on the various properties of UHPC. Even if steel fibers are the most widely applied fibers, other types of fibers have also been extensively utilized in UHPC to address the limitations of steel fibers (i.e., the potential for corrosion, increased density leading to additional load, and higher costs)14,90,91,92. Carbon-based additives are promising materials for reinforcing UHPC, which possess elastic modulus, excellent tensile strength and electrical conductivity93,94,95. The commonly used carbon-based additives include carbon fiber, carbon nanotube (CNT), as well as graphite nanoplatelet57,58,96,97. It has been proved that the enhanced connection between the fiber and matrix is facilitated by rough surface of carbon fibers96. The utilization of CNT provides fiber bridging effects, filler effects, and nanoscale effects, thereby establishing the denser microstructure inside UHPC27,35,66. In addition to carbon-based additives, synthetic fibers have also been shown to provide a significant increase in ductility of concrete. However, due to their hydrophobic nature, both PE fibers and PP fibers restrict the ingress of water into the internal spaces of the concrete matrix, consequently attracting more air bubbles to adhere to the fiber surfaces, thereby forming a porous ITZ98,99. As a result, the mechanical properties of UHPC with the addition of synthetic fibers are lower than those of UHPC with the addition of steel fibers. PVA fibers exhibit hydrophilic characteristics and possess high chemical adhesion. However, within the UHPC matrix, their fracture becomes more severe as the strength of the surrounding matrix is sufficient to cause synthetic fiber breakage, thereby suppressing the increase in multiple cracking behavior and strain capacity100. Additionally, poor dispersibility of synthetic fibers due to their high aspect ratio can lead to reduced workability, as longer fiber length may result in fiber agglomeration, leading to localized softening and the formation of weak zones101. Nevertheless, the addition of synthetic fibers can have beneficial effects on fire resistance, thereby enhancing the durability of UHPC. Pioneering studies have indicated that the incorporation of PP fibers can reduce the weight loss of UHPC exposed to temperatures exceeding 200 °C102. Simultaneously, the melting and expansion of synthetic fibers under elevated temperatures result in formation of micro-cracks and tunnels within the aggregate, thereby creating an interconnected network that significantly enhances the permeability of UHPC102,103. This is an advantage not achievable with steel fibers. Furthermore, the utilization of mineral fibers (e.g., wollastonite and basalt fibers) not only enhances mechanical performance of UHPC but also offers the advantage of lower cost and corrosion resistance when compared to steel fibers. Basalt fibers are natural volcanic materials with a high melting temperature of 1450–1500 °C104,105. Wollastonite fibers are natural silicate fibers containing SiO2, CaO and Al2O3106,107. Mineral fibers possess a similar constituent to cementitious materials, helping to resist deformation of matrix and resulting in a stronger fiber/matrix bond105,108. Furthermore, cellulose fibers which are natural polymer made from wood, were used as internal curing materials to limit shrinkage of UHPC109,110,111. Cellulose fibers exhibit the advantages of abundant availability, ease of production, and substantial ecological value, while also serving to restrict width of crack and enhance durability of concrete112. After presenting an overview of these fibers and their respective application effects, a crucial inquiry arises: can the simultaneous addition of these fibers along with steel fibers in UHPC result in advantageous synergistic enhancements?

The goal of incorporating hybrid fibers is to obtain synergistic effects of various fibers regarding the applications of UHPC113,114. While in most studies, the substitution of steel fibers with hybrid fibers has shown limited improvement in compressive strength of UHPC, which it can even have a negative impact. However, the utilization of hybrid fibers can significantly enhance strain capacity and tensile strength of UHPC. Furthermore, utilization of hybrid fibers can have beneficial effects on the ductility115 and autogenous shrinkage116,117 of concrete. The application of hybrid fibers reduces propagation of micro-cracks within UHPC, resulting in decreased pore size and ultimately improving the microstructure of UHPC. Moreover, some studies have shown that the hybrid utilization of steel fibers and PP fibers in concrete exhibits the synergistic effect on crack initiation, which mechanism behind involves the integration of the pull-out behavior of steel fiber and disruptions caused by PP fibers118. Additionally, chloride ion permeability of UHPC can be significantly reduced by this type of combination (i.e, steel fibers and PP fibers), which reduced the sensitivity of UHPC to corrosive environments119. These findings suggest that using hybrid fibers holds promising potential for improving the durability and sustainability of UHPC.

Research progress in multiscale mechanics

Multiscale characteristics of UHPC

UHPC, as a representative heterogeneous material, exhibits distinctive multi-scale structural characteristics. Its constituents primarily encompass cement, fly ash, blast furnace slag, silica powder, water, fine aggregates and additives. In particular, to enhance the sustainability of UHPC, the global academic community is concerned with reducing the use of cement without compromising its performance. The incorporation of nanomaterials as additives in cementitious materials has emerged as a popular approach to address this challenge. When extending investigation from macro scale to micro scale, the crystal core effect and electrical properties of materials surface is continuously changing, thereby giving rise to novel properties such as the micro-size effect and surface-related phenomena that remain unattainable at macro scale. By capitalizing on the unique attributes exhibited by nanomaterials, it becomes possible to manipulate the hydration process of cement, subsequently influencing the mechanical properties and long-term durability of the hardened paste120,121,122. Hence, nanoadditives can be a substitute for cement in UHPC, reducing CO2 emissions and improving its performance, and they can even add new properties. In this case, UHPC exhibits both compositional heterogeneity and spatial discontinuity, possessing discrete characteristics at the nanoscale (i.e., spatial discontinuity) as well as compositional heterogeneity. At the microscale and mesoscale, due to the incorporation of a significant amount of ultrafine cementitious materials and the utilization of the low w/b ratio, UHPC typically exhibits a denser microstructure compared to ordinary concrete123,124. The crucial constituents in the microstructure of UHPC encompass quartz powder, hydration materials (e.g., gelatinous calcium silicate hydrate gel), and unhydrated cement clinker. These components hold significant relevance in the meticulous assessment of UHPC’s microstructural characteristics. Compared to conventional concrete, ITZ in UHPC is less porous, lighter and significantly denser, as maximum calcium hydroxide crystals are converted into thick hydrated calcium silicate (C-S-H) gels due to low w/b ratio and pozzolanic reactions between calcium hydroxide and reaction admixtures98,99,125. With its distinctive microstructure, UHPC demonstrates an innovative composition resulting from the enhanced ITZ and the tightly packed arrangement of solid particles. Therefore, the investigation of the mechanical properties of UHPC requires additional effort to take into account its unique material characteristics.

Due to the complementary and synergistic effects achievable by incorporating different types of fibers, hybrid fiber-reinforced UHPC represents a cutting-edge direction regarding its advancement126. Currently, research on hybrid fibers in terms of fiber selection and understanding their reinforcement mechanisms heavily relies on empirical experimentation, leading to resource wastage and a lack of systematicity in studies related to hybrid fiber-reinforced UHPC127,128. Therefore, a multi-scale analysis is necessary to thoroughly investigate the mechanisms of performance enhancement and cross-effects of different fibers in concrete. Through simulations and experimental data, based on parameters such as strength, stiffness, and fiber reinforcement at various scales, it is essential to establish a comprehensive and systematic fiber matching principle129,130. This will provide a solid foundation for fiber selection in hybrid fiber-reinforced UHPC, reducing resource wastage and offering theoretical support and research methods for the development of novel high-performance UHPC.

Multiscale theoretical methods

The comprehensive study of multiscale mechanics of UHPC requires a holistic consideration of its structural characteristics at macroscopic, mesoscopic, and microscopic scales63,131,132,133. By employing multi-scale analysis methods, it is crucial to investigate the relationships between the compositional distribution, micro-nano features, and mechanical properties of UHPC. It aims to establish quantitative relationships between the macroscopic performance of cementitious composites and the properties of their constituent materials, as well as the various structural characteristics at different scales. Furthermore, it seeks to elucidate the underlying mechanisms by which different organizational forms at each scale contribute to the disparate macroscopic performance exhibited by the materials20.

Regarding the multiscale analysis of concrete, the approaches principally encompass two distinct methodologies: hierarchical and concurrent methods. Table 2 presents a compilation of commonly employed theoretical and simulation methods in multi-scale analysis134,135,136. Hierarchical methods decompose the practical problem into multiple levels based on different temporal or spatial scales137. Subsequently, appropriate parameters are selected to forge connections across these disparate levels. The analysis can either proceed from microscopic to macroscopic properties through a step-by-step equivalence and inversion or optimize the material’s structure from macroscopic requirements, employing theoretical or numerical methods to link performance across scales138. Effective use of hierarchical approaches demands a deep understanding of the analysis process and material properties to choose key parameters accurately and ensure analysis precision. Concurrent method simultaneously addresses multiple scales in a single experiment139. It integrates mesoscopic, microscopic, and nanoscale regions within a continuum model’s computational domain, using mathematical relationships for scale coupling140,141. Typically employing a continuum model, it resorts to molecular or quantum mechanics models for critical areas like crack tips. This method facilitates parallel multiscale computation, reducing complexity while preserving accuracy142,143, aiming for achieving universally applicable full-scale simulations panning the nanoscale, microscale, mesoscale, and macroscale144,145. Concurrent methods are primarily applicable to numerical simulations, which will be further discussed in Section “Multiscale modeling methods”. To date, the authors’ review reveals an absence of any unified mechanical theories that adequately span all length scales required for concurrent multiscale analysis.

For heterogeneous composite materials such as UHPC, resolving the interfaces between distinct components is a critical aspect of hierarchical theoretical approaches, aimed at enhancing the understanding of their mechanical responses under load, the transfer of load between components, and the resultant alterations in material structure. Among these, the cohesive zone model (CZM) stands as one of the frequently utilized methodologies for analyzing load transfer issues at the interfaces of concrete and other composite materials. With CZM, localized damage in materials can be effectively captured and modeled through nonlinear springs that denotes the major physical variables. CZM surpasses linear elastic fracture mechanics by incorporating microscale details and the fracture processing zone, thus enabling a comprehensive analysis of failure mechanisms and energy dissipation. Moreover, CZM integrates crack initiation and growth into a unified framework, facilitating its straightforward formulation and application in numerical simulations. CZM stands out among models addressing concrete fractures, primarily due to its optimal balance between conceptual simplicity, computational ease, and predictive precision.

Recently, CZM has experienced considerable advancement in its application. CZM can be applied to simulate the fiber reinforced polymer (FRP)-concrete interface debonding under different loading conditions (e.g. mix-mode)146,147. Utilizing a mode-independent traction-separation law, the shear and peel responses of interface can be modeled. Analytical expressions for normal and shear stresses at the interface, as well as axial load of FRP plate, are derived for various stages of debonding, thereby integrating initiation and progression of debonding into a singular framework. CZM can also be applied to coupling with thermal flux-separation relation and diffusion flux-separation relation in multiscale modeling, enabling the prediction of temperature and humidity jump across cohesive cracks148. In this model, the meso-structure of concrete is characterized by randomly distributed aggregates embedded within the cement paste, complemented by zero-thickness interface elements that represent ITZ between cement and aggregates. CZM is applied to model the debonding at the ITZ. Additionally, the development of the mixed-mode CZM is grounded in strength models rather than traction laws149. It facilitates the independent choice of models for each direction, offering benefits for simulations under mixed-mode conditions and highlighting constraints in approaches reliant on effective displacements. With this advancement, the traction-separation law and or strength model150 in CZM can be combined with micromechanically motivated thermal and diffusion flux-separation relation to accurately describe ITZ between cement and aggregates on concrete’s mechanical, thermal, and diffusion characteristics.

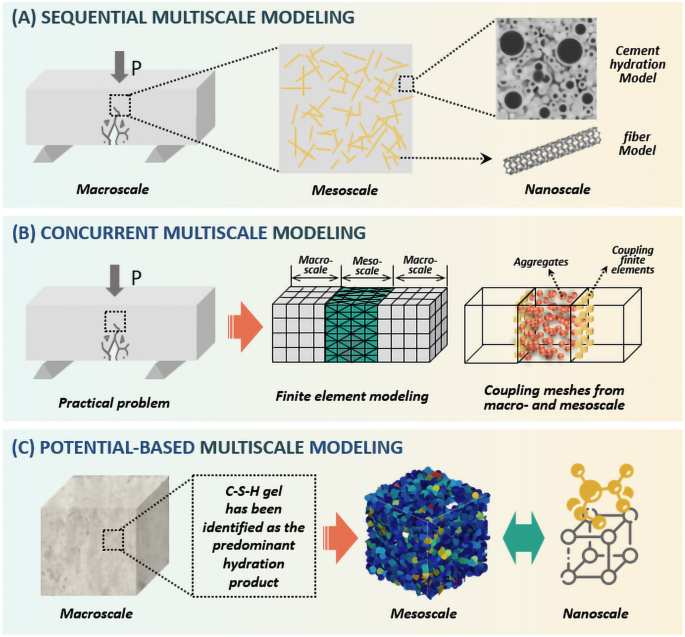

Multiscale modeling methods

UHPC exhibits complex compositions and its material interior possesses discontinuous spatial distribution, showcasing typical characteristics of a discrete body151. Notably, in UHPC with the addition of reinforcing phases, the material remains discontinuous at the nanoscale, and the interactions between atoms exhibit significant nonlinearity152. Therefore, the inclusion of nanoscale analysis is necessary within the multi-scale framework. This entails establishing a relationship between the interactions among atoms and the parameters of the continuum medium153. Simulation methods that encompass atomic and quantum scales, such as first-principles and MD simulations, offer precise modeling of atomic and quantum phenomena154. Yet, due to computational limitations, the capacities of these atomistic scale methods fall significantly short of the requirements for simulating practical problems155,156. Therefore, multiscale simulations have emerged as the primary approach to address the coupling problems between the nanoscale and macroscopic scales. As shown in Fig. 3, currently the multi-scale simulation approaches involving discrete bodies can be categorized into the following categories:

A Sequential multiscale modeling: how to investigate the mechanical properties and fracture behavior of fiber-reinforced concrete158; B Concurrent multiscale modeling: how the handshake coupling method could be applied to the crack predicting for concrete176; C Potential-based multiscale modeling: example of coarse-grained cementitious materials97.

The first approach is the sequential multiscale modeling, includes decoupling the scales and employing corresponding methods for analysis at each scale sequentially29,97. In atomistic scale, the atomic configuration and interatomic interactions are monitored through first principles and MD simulations66,67,68,157. The mesoscale modeling requires the information obtained from representative volume elements (RVE) that applied equivalent properties from the atomistic results. Then, through finite element and continuum simulation methods, macroscopic constitutive relationships are established. These relationships are subsequently applied to address practical problems. For instance, in the investigation of the mechanical properties and fracture behavior of CNT-reinforced concrete, at least three scales are defined158,159. MD simulation is applied to simulate the tensile behavior of CNT at the nanoscale, from its mechanical properties that are scaled up to the microscale. Then, a hydration model determines the chemical composition of cement, leading to the construction of RVE based on hydration results. Subsequently, FEM assuming isotropic damage across all phases, assesses the mechanical and damage characteristics of bulk material. This microscale homogenized response is then elevated to the macroscale using the extended finite element method (XFEM) for damage analysis, aiming to forecast damage patterns in three-point bending tests and mixed-mode crack growth. This case study also illustrates that the complexity of multiscale analysis renders real-time coupling techniques a challenge within the framework of sequential multiscale modeling160. It also underscores that possessing a deep and comprehensive understanding of mechanical processes is crucial for selecting key parameters, so as to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of modeling161.

The second approach is the concurrent multiscale simulation method that directly couples atomistic simulations with continuum simulations162. In multi-scale simulations that combine atomistic simulations with finite element methods, the computational domain is typically divided into a continuum region, an atomistic region, and a transitional region. The key to successful cross-scale simulation lies in effectively handling the interface or transitional region between the continuum and atomistic domains. A more direct approach to address this is by gradually refining the finite element mesh in the transitional region to the scale of atomic lattice. At the interface, the mesh nodes are directly associated with individual atoms, maintaining a one-to-one correspondence at the interface between two scales throughout the deformation process163. This method is referred to as the interface coupling method. Currently, commonly used interface coupling methods include the Finite-Element combined with Atomistic modeling (FEAt) method164, the coupled atomistic and discrete dislocation (CADD) method165,166, the Meta-Surface Antenna Array Decoupling (MAAD) method167,168, and the AFEM/FEM method16,169,170,171. However, in interface coupling methods, reducing the finite element mesh size in the transitional region to the scale of atomic lattice poses modeling challenges and may introduce computational errors. Therefore, other coupling multi-scale methods have been proposed referred to as handshake coupling methods. In handshake coupling methods, when dealing with the transitional region (or coupling region), the finite element mesh nodes are no longer directly tied to individual atoms. Instead, macroscopic mechanical quantities and microscopic mechanical quantities are related through averaging, superposition, and other methods. Currently, the main weak coupling methods include the continuum-molecular dynamics overlap method172, the bridging scale method (BSM)173, the bridging domain method (BDM)174, and the micro-macro molecular dynamics method (MMMD)175. For instance, the handshake coupling method could be applied to the crack prediction for concrete176. In elastic regions of concrete, a macroscopic model utilizing uniform elastic parameters is employed. For zones anticipated to develop cracks, a mesoscopic approach employing mesh fragmentation considers concrete as a diverse three-phase material, including mortar matrix, coarse aggregates, and ITZ. Then, coupling finite elements are applied for coupling non-matching meshes between macro and mesoscale. The crack initiation and propagation process in concrete is monitored through the mesh fragmentation technique.

The third category of methods is the multi-scale approach based on interatomic potential functions, which couples the concepts of discrete bodies and continua by utilizing potential energy functions140,141. This approach enables multi-scale simulations within a unified algorithmic framework177. Among them, typical representative methods include the quasi-continuum method (QC)178, coarse-grained (CG) modeling97,143,179, and molecular statistical thermodynamics (MST)180. For cementitious materials, some pioneering studies have developed CG models. Among those, C-S-H gel has been identified as the predominant hydration product, constituting over 50% of the volume fraction and serving as the primary binding agent in cement matrices181. It has been extensively adopted in MD simulations and CG models for studying cement-based composites182,183. C-S-H particles are utilized to simulate CNT-reinforced cementitious composites, modeled as polydisperse spherical particles with interactions governed by a modified Lennard-Jones potential97,184. These models involve grid partitioning of the computational domain and derive motion equations from molecular dynamics equations of motion. Additionally, they derive mass and stiffness matrices from interatomic potential functions and establish constitutive relationships that are specific to the grid size. The entire computational domain lacks an interface between the continuum and atomic systems, enabling seamless connection across different scales. Compared to the quasi-continuum method, CG modeling can account for a larger-range of temperatures and is suitable for studying dynamic phenomena such as material fracture, interfacial debonding mechanism and crack propagation185.

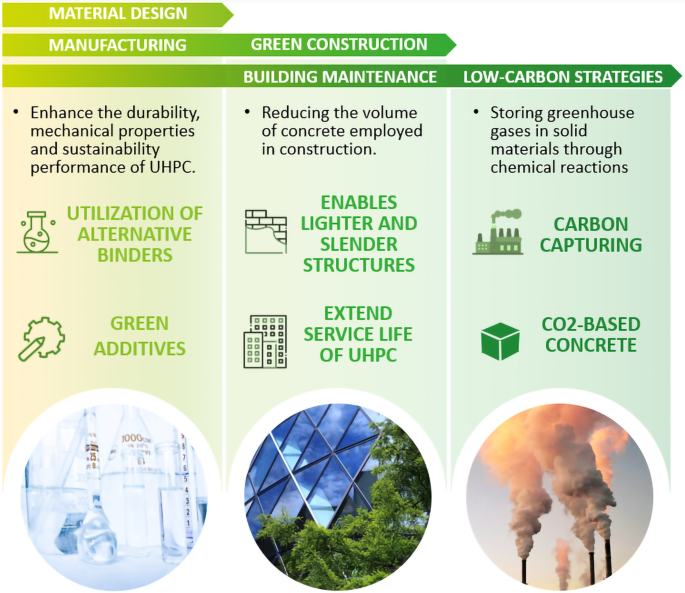

Ecological considerations in practical applications

The greenhouse effect is a major global environmental concern, poses a critical challenge to achieving sustainable development in the modern era. Previous research has indicated that cement production contributes approximately 5% of the overall carbon dioxide emissions186. The significant responsibility of the construction industry to reduce emissions arises from the high emission rate associated with concrete. Consequently, it is critical to make significant progress in terms of ecological and sustainable development in material manufacturing, green construction, and building maintenance187. Here we present the overview of the strategies to enhance the sustainability and environmental friendliness of UHPC in Fig. 4. While UHPC typically exhibits higher cement content compared to conventional concrete that releases more energy-related CO213, it allows for the design of thin and lightweight structures188,189. This, in turn, leads to a reduction in the amount of concrete used during construction and decreases emissions associated with material transportation. Moreover, numerous studies have been conducted to reduce the cement content of UHPC without compromising its performance. Additionally, sustainable UHPC is capable of withstanding harsh environments that can effectively reduce carbon emissions in building maintenance, making it an effective approach to enhancing building sustainability190.

The framework commences with sustainable design, highlighting the utilization of alternative binders and green additives. Subsequently, it transitions to green construction techniques, illustrating UHPC’s role in fostering sustainable progress in structural endeavors. The depiction culminates with an overview of pioneering low-carbon approaches, signifying a forward-looking commitment to reducing the carbon footprint in UHPC.

Sustainable design

To enhance the sustainability performance of UHPC, the utilization of alternative binders and green additives and proves to be an effective approach. Based on carbon footprint assessment, the developed eco-UHPC that incorporates dehydrated cementitious powder (DCP) in the matrix can be regarded as a sustainable and environmentally friendly product. From a sustainability perspective, increasing the dosage of DCP is beneficial to further improve UHPC performance190. It has been indicated that CO2 emissions from per unit of sustainable UHPC and the ratio of CO2 emissions/compressive strength decrease with the increase of DCP content191, which shows that green UHPC exhibits better utilization of cement. Moreover, the CO2 emissions during UHPC production also can be greatly decreased with the addition of DCP192. According to measurements, a conventional UHPC composed solely of pure cement necessitates 377 kg of CO2 per unit volume. With a 25% increase in DCP content, the emissions can be reduced to 298 kg, which reduces 21% of the initial CO2 emission191.

The utilization of green additives, such as by-products from the power sector like fly ash, enables UHPC to further advance towards sustainable development by incorporating materials that would otherwise be discarded. Serval solid waste resources can serve as substitutes and have been incorporated into concrete and mortar to enhance their properties and conserve energy, including construction and demolition waste193,194, fly ash21, metakaolin195, silica fume196, waste glass47,48,197, plastic waste198, marble waste199 and rock waste200. However, it has been reported that the utilization of green additives in UHPC concrete may possess a negative effect on fresh and mechanical properties, necessitating early consideration in roadways and structural applications to ensure optimal performance65.

Evaluating the effectiveness of alternative binders and additives involves assessing their impact on UHPC’s mechanical properties, environmental benefits, economic viability, chemical and physical compatibility, and compliance with regulatory standards. Materials such as fly ash, silica fume, ground granulated blast furnace slag, and rice husk ash have shown promise in enhancing UHPC’s performance, offering improved compressive strength, durability, and workability. The sustainable design of UHPC using waste materials not only addresses the environmental impact of construction by reducing CO2 emissions and virgin raw material consumption but also contributes to waste reduction. The challenge lies in balancing performance, sustainability, and cost, necessitating ongoing research to optimize the formulation of UHPC with waste materials for a greener construction industry. Currently, the selection of alternative binders and additives for UHPC remains limited and relies primarily on experimental and empirical approaches. The lack of mechanistic understanding hinders the determination of optimal additive proportions. Thus, it is crucial to employ a multiscale mechanics approach for establishing quantifiable correlations between the categorization of UHPC compositions, additive content, and macroscopic performance201.

Green construction

The enhanced mechanical strength of UHPC enables the construction of lighter and slender structures, consequently reducing the volume of concrete employed in construction13,202. Specifically, the exceptional strength of UHPC enables the construction of slender structures, resulting in a reduction in the self-weight of the structures. UHPC structural elements with reduced cross-sectional dimensions also free up valuable architectural space18. Moreover, with its exceptional strength-to-unit weight ratio, low permeability, and compact microstructure, UHPC showcases excellent resistance to both fire and explosive spalling at elevated temperatures71,102,105,108,203. These superior properties extend the length of service life of UHPC significantly, leading to a reduction in demolition waste, transportation demands, and environmental pressures.

Regarding materials, the microstructural and macroscopic characteristics of UHPC mixtures have been investigated, aiming to enhance these properties by substituting valuable, limited, or unavailable traditional components to achieve maximum practical density96,99. UHPC combines the advantages of fiber-reinforced concrete, high-strength concrete and self-compaction concrete41. The compressive strength is measured at 150 MPa, coupling with flexural and tensile strength of 30 MPa and 5 MPa respectively. It is estimated that replacing ordinary concrete with UHPC can reduce the total aggregate content (including fine and coarse particles) used in structural components by 30%. The 100% proportion of coarse aggregates can be reduced96, resulting in a reduction in the consumption of concrete raw materials.

Regarding structural application, the environmental benefits of UHPC have been confirmed through practical case studies in the construction industry. An evaluation is conducted to assess the energy consumption and life cost of a bridge design that incorporates both timber and UHPC204. The UHPC components used in the bridge deck require negligible maintenance over 100 years or more. This extended maintenance-free lifespan, coupled with reduced maintenance work and the use of fewer materials in the design, contributes to an exceptionally low annual CO2 emission. It is also reported that three distinct UHPC bridges were constructed in diverse locations for comparison205. Comparisons have been made between the greenhouse gas emissions of highway bridges constructed using UHPC and those of standard concrete highway bridges206. It was observed that when considering only concrete emissions, the CO2 emissions were reduced by 50%205. A study has been conducted to model the repair of highway bridges, which includes three different repair material systems: traditional concrete (using waterproof membrane), UHPC, and eco-UHPC207. Regarding eco-UHPC system, the environmental impact of cement is notably diminished compared to UHPC system, achieved through the substitution of 50% of cement with limestone filler. Negative environmental impact of repair solutions with both UHPC and eco-UHPC is significantly lower compared to that of standard solutions, which enable reductions of 60% and 72%, respectively207. Global warming potential has decreased 42% in comparison with eco-UHPC with the typical UHPC mixture207. These studies demonstrate carbon footprint and cost-effectiveness of using UHPC have significantly improved the ecological benefits of construction207, also showing the potential of UHPC and promoting its widespread use to mitigate environmental impacts13.

Low-carbon strategies

Carbon capturing is a technology that stores greenhouse gases in solid materials through chemical reactions. It addresses climate change by reducing emissions and utilizing the advantages of ecological raw materials, while creating commercially viable and sustainable products13,208. CO2-based concrete provides an alternative and ecological approach for carbon capturing. Concrete has the capacity to accommodate the CO2 generated by cement production facilities. Concrete can undergo carbonation, capturing CO2 through the rapid carbonation of its constituent minerals, carbonation during hydration, and the overall carbon capturing process. The collected CO2 from cement manufacturers can be pumped into UHPC, facilitating a reaction with calcium-rich hydration products such as C-S-H and calcium hydroxide to produce calcium carbonate (CaCO3)209. The exceptional durability of UHPC manifests in its resistance to carbonation, corrosion, and transport capacity, contributing to the formation of a dense and uniform matrix characterized by an extraordinarily low porosity. The significantly low permeability and lower water-to-cement ratio endow UHPC with remarkable resistance to carbonation188. The results of the rapid chloride permeability test (RCPT) conducted on UHPC specimens are consistent with the findings of the surface resistivity test, demonstrating a significantly high energy passing range of 3000–10,000 Coulombs across various non-proprietary mixtures210.

However, carbon capturing technology for UHPC still faces challenges. It is reported that the compressive strength of carbon capture concrete (CCU) can be reduced through CO2 curing211. Under such circumstances, CCU requires a higher ordinary Portland cement content to attain comparable compressive strength as conventional concrete. The carbon emissions from the production of ordinary Portland cement play a notable role in terms of CO2 output. Heightening the ordinary Portland cement proportion in concrete mixtures leads to amplified CO2 emissions during the upstream cement manufacturing process, potentially nullifying the advantages derived from CO2 capture and utilization in concrete production. Therefore, during the development of carbon capturing technologies, conducting a multiscale pre-assessment of carbon capture in UHPC can aid in identifying the most effective research strategies to address the issue of greenhouse gases.

Challenges and perspectives

Despite the exceptional mechanical and durability properties of UHPC, which enhance its application in resilient and sustainable reinforced concrete structures212, its widespread deployment still faces certain challenges. In terms of the design for sustainable UHPC, the substitution of cement with alternative binder materials (e.g., fly ash, slag, and silica fume) poses challenges in achieving early-age mechanical performance in UHPC. As coal-fired power plants shift towards natural gas plants, traditional supply chain management becomes increasingly limited. Hence, further research is also required to explore sustainable SCMs14. For UHPC with added nano-additives, achieving a uniform dispersion of nanomaterials within the concrete matrix remains challenging. Consequently, the proportion of nano-particles substituting cement in UHPC remains relatively low. Further research is needed to explore the dispersion of nanomaterials and maintain their effectiveness at higher dosages in UHPC120. This can be achieved through the application of multiscale mechanical analysis methods. Furthermore, the mechanism behind the seeding effect, which constitutes a fundamental role of nanomaterials in UHPC, remains unclear. Employing finite element techniques can shed light on this phenomenon. Consequently, there is a need for additional research to explore the impact of varying nanomaterial sizes on the performance of UHPC120.

The production aspect of UHPC materials is equally confronted with challenges. Due to its elevated packing density and absence of coarse aggregate, UHPC exhibits a higher homogeneity compared to conventional concrete as its higher packing density and without coarse aggregate which also causes straight-line cracks. Enhancing the ductility and tensile strength of UHPC can be achieved through the incorporation of fibers that effectively impede crack propagation213. However, the low w/b ratio, addition of fibers, and reduced workability of UHPC lead to challenges during the casting process of UHPC. Moreover, the orientation, distribution, and type of fibers have an impact on the macroscopic properties of UHPC84,86. Therefore, the casting of slender UHPC elements still requires an effective method to ensure the proper distribution and orientation of fibers within the cementitious matrix. Additionally, high-energy mixers are necessary for processing UHPC due to its low w/b ratio17.

Numerous challenges are also encountered in the practical applications of UHPC. UHPC constructions present deviations from conventional reinforced concrete practices, necessitating a proficient workforce comprising builders, engineers, and specialists who possess expertise in UHPC technology and design considerations. However, the availability of qualified personnel in this domain remains limited, emphasizing the need for teams well-versed in UHPC methodologies and design intricacies41. In the establishment of regulations within the construction industry, it is crucial to develop fair and accurate strategies for the optimization of UHPC components and mix designs. Relying solely on experimental blends is insufficient, necessitating the utilization of multiscale analytical methods20. In the formulation of UHPC design and construction criteria, a comprehensive approach that incorporates field experience, empirical analysis, and scientific calculations is vital. The complexities of establishing international guidelines arise from the diverse experiences with UHPC across different countries41. Efforts have been made by China, France, Germany, Japan, and Switzerland to standardize UHPC, aiming to facilitate its widespread adoption. France took a significant step in 2016 by announcing its inaugural UHPC standard214.

Despite facing challenges, UHPC has undergone several decades of development and continues to be a promising and sustainable construction material. As discussed extensively in Section “Fundamentals of Fiber-reinforced UHPC”, the rapid advancements in multiscale mechanics hold great potential for invigorating the material design of UHPC. Meanwhile, the integration of AI with construction materials and the Industry 4.0 framework can also achieve the intelligent design and application of UHPC215. This innovation process integration process is based on computer science, starting from the digitization of building materials, developing towards advanced manufacturing, and ultimately reaching the level of intelligent application and operation of UHPC buildings216,217. Nowadays, innovative work in additive manufacturing (3D printing) provides promising technologies for various fields including UHPC218,219. In principle, the use of a printing machine for concrete extrusion offers a straightforward and expeditious approach to constructing intricate three-dimensional structures220,221. Several recent studies have demonstrated the feasibility of using UHPC in 3D printing222,223,224, indicating that 3D printing developed using UHPC-related materials has better shape retention than using traditional cast UHPC. However, there is still a lack of implementation records for 3D printing based on UHPC projects, due to technical limitations in 3D printing process and configuration (i.e., pumping rules, addition of fibers, flow rate, and nozzle design)225. Although there have been cases of UHPC 3D-related printing, current attempts are limited to low-complexity 3D printing. Present investigations call for the design and fabrication of 3D-printed UHPC materials endowed with pumpability, constructability, and extrusion capabilities, thus highlighting the remarkable prospects in the development of UHPC 3D printing technology226.

Responses