Myoblast-derived ADAMTS-like 2 promotes skeletal muscle regeneration after injury

Introduction

Regeneration of skeletal muscle microinjuries resulting from daily activities or exercise is a highly efficient process resulting in fully restored muscle function and return to cellular homeostasis1. When muscle injury exceeds a critical size, for instance in traumatic volumetric muscle loss or after cancer resections, endogenous muscle regeneration is insufficient to restore muscle function2,3. Replacement of lost muscle tissue by fibrotic tissue further compromises functional muscle regeneration and limits the mobility of affected muscle groups4. In muscular dystrophies, chronic muscle injuries overwhelm endogenous regeneration over time due to muscle stem cell exhaustion and the buildup of a fibrotic extracellular matrix (ECM)5,6. The rapid decline of muscle function in the most severe muscular dystrophies, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), leaves children wheelchair-bound by age 10-12 and results in mortality in young adulthood7. Therefore, there is a need to fully elucidate the mechanisms that promote muscle regeneration, which may result in innovative therapeutic strategies for acquired and genetic muscle disorders or could be applied to augment skeletal muscle engineering approaches.

Muscle regeneration following acute injury comprises a sequence of cellular events that involve muscle-resident and infiltrating cell populations. Key events include an early influx of immune cells, the activation of quiescent muscle stem cells (i.e. satellite cells), which are differentiating into myoblasts, and the activation of fibroadipogenic progenitors (FAPs), which regulate muscle stem cell differentiation and restore muscle architecture1,8,9. Injury-mediated activation of quiescent PAX7-positive muscle stem cells follows the disruption of their stem cell niche and extrinsic signaling events10,11,12. Muscle stem cells then generate MYOD-positive myoblasts through asymmetric cell division while renewing the muscle stem cell pool13. Myoblasts proliferate and, following cell cycle exit, differentiate into MYOD-positive/MYOG-positive/PAX7-negative myocytes14,15. Myoblast-derived myocytes then express myomaker and myomixer, which allows them to fuse with each other to form new myofibers or to fuse with existing myofibers and restore their contractility14,16,17,18. Myoblast differentiation is regulated by various signaling pathways including WNT- and TGFβ-signaling19,20,21,22. While WNT signaling is thought to promote myoblast differentiation, TGFβ signaling is largely inhibitory. In mice, muscle regeneration is typically completed 3-4 weeks after acute injury23. Regenerating and regenerated myofibers are marked by transient expression of embryonic myosin heavy chain (eMyHC) and the presence of centrally localized nuclei, respectively24,25.

In addition to the restoration of contractile myofibers, muscle regeneration also requires the restoration of its ECM, which separates individual myofibers through a basal lamina, contributes to the muscle stem cell niche, provides structural integrity, and connects muscle to tendon at the myotendinous junction26. The critical role of the ECM for muscle function is underscored by pathogenic variants in ECM proteins that can cause muscular dystrophies or negatively affect their disease progression. For instance, pathogenic variants in laminin α-2 (LAMA2) or collagen type VI chains (COL6A1, COL6A2, COL6A3) can cause merosin-deficient or Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy, respectively27,28,29,30. More recently, a polymorphism in the TGFβ-regulator LTBP4 was associated with accelerated disease progression in a DMD mouse model31. Muscle function can also be compromised in syndromic disorders caused by mutations in ECM proteins manifesting as muscle hypoplasia in Marfan syndrome (FBN1) or apparent muscle hyperplasia (pseudomuscularity) in acromelic dysplasias (ADAMTSL2, ADAMTS10, ADAMTS17, and other ECM genes)32,33,34. One of the genes implicated in acromelic dysplasias is the regulatory ECM protein a disintegrin and metalloprotease with thrombospondin type I motifs-like 2 (ADAMTSL2). Pathogenic variants in ADAMTSL2 cause geleophysic dysplasia, Al Gazali syndrome, or a dominant connective tissue disorder in humans, and Musladin-Lueke syndrome in dogs35,36,37,38. While ADAMTSL2 was described as a negative regulator of TGFβ signaling in skin and cardiac fibroblasts, we recently showed that ADAMTSL2 promoted myoblast differentiation by augmenting WNT signaling19,35,39,40. Conditional inactivation of Adamtsl2 in myogenic progenitor cells resulted in abnormal myofibers and delayed myogenic differentiation of primary myoblasts.

Since myoblast differentiation is also required for muscle regeneration, we hypothesized that ADAMTSL2 is a positive regulator of muscle regeneration after acute injury. We used BaCl2 injection into the mouse tibialis anterior (TA) muscle after Adamtsl2 deletion in myogenic muscle stem cells, as an established model system to induce acute muscle injury. BaCl2 injection causes hyperpolarization and rupture of myofibers, but leaves muscle stem cell populations intact23,41. In this model, we observed delayed muscle regeneration after acute BaCl2 injury, indicated by reduced and persistent eMyHC staining. Delayed regeneration in ADAMTSL2-deficient muscle was rescued by delivery of a recombinant myogenic ADAMTSL2 protein fragment or of ADAMTSL2-expressing myoblasts. Delayed regeneration of ADAMTSL2-deficient muscle could be explained mechanistically by a reduction in the number of committed myoblasts, which are the precursors of myocytes and thus of regenerating myofibers. Together these findings indicate that ADAMTSL2 plays an important role during muscle regeneration, where it regulates the pace of progression of myoblast-to-myocyte differentiation and ultimately the restoration of contractile myofibers.

Results

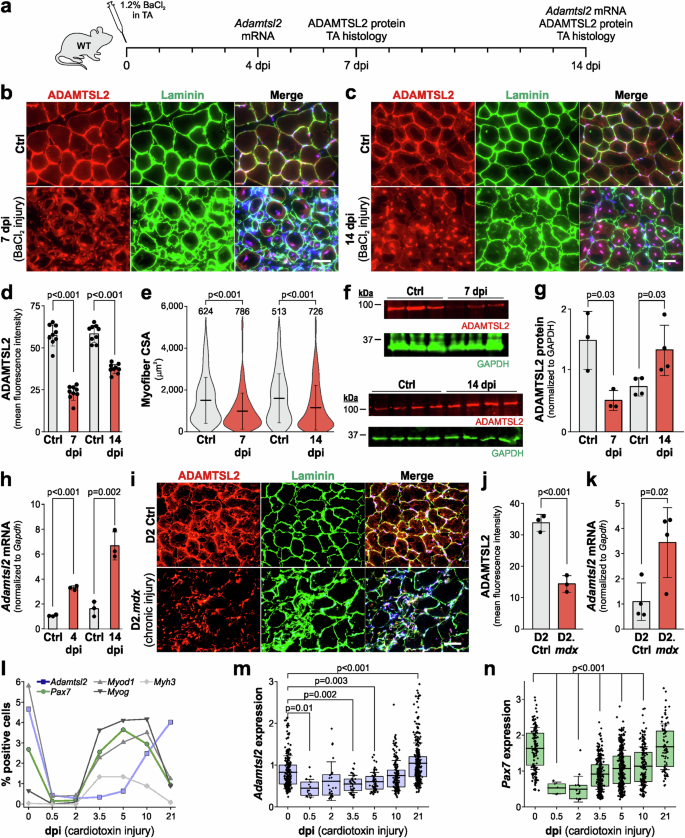

Spatiotemporal regulation of ADAMTSL2 in models of acute and chronic muscle injuries

We previously showed that secreted ADAMTSL2 promoted myoblast differentiation and myotube formation during muscle development and postnatal growth19. Since myoblast differentiation contributes to the restoration of muscle function after injury, we investigated whether ADAMTSL2 plays a role during muscle regeneration. To this end, we first induced muscle injury by BaCl2 injection into the TA muscle and determined the spatiotemporal regulation of ADAMTSL2 expression (Fig. 1a). The TA muscle is frequently used to investigate muscle regeneration after acute injury due to its accessibility and size. In uninjured wild type TA muscle, ADAMTSL2 localized to the endomysium and partially costained with the basement membrane component laminin surrounding individual myofibers and the muscle stem cell niches (Fig. 1b, top). At 7 days post injury (dpi), ADAMTSL2 localization was disrupted, showing a more punctate pattern and little co-staining with laminin (Fig. 1b, bottom). Myofiber cross-sectional area (CSA) was irregular and laminin staining suggested thicker and irregular basement membranes. An increased number of DAPI-positive nuclei resulted from immune cell infiltration and muscle stem cell and myoblast proliferation as part of the injury response. At 14 dpi, ADAMTSL2 continued to be mislocalized in a punctate pattern with significant co-staining in the vicinity of the centrally-localized nuclei, which characterize regenerated myofibers (Fig. 1c, bottom). The endomysium and laminin-staining were partially restored at 14 dpi, myofiber CSA and basement membrane appearance was more regular, and normalization of the number of DAPI-positive cells indicated resolution of muscle regeneration. Quantification of the ADAMTSL2 mean fluorescence intensity showed a 2.4- and 1.6-fold reduction at 7 and 14 dpi, respectively (Fig. 1d). Consistent with prior literature, myofiber CSA of the injured TA muscle was reduced at 7 and 14 dpi compared to the contralateral, uninjured control TA (Fig. 1e). These findings were corroborated by western blot quantification of ADAMTSL2 protein extracted from injured and uninjured TA muscles at 7 dpi, showing a 2.9-fold reduction in total ADAMTSL2 protein (Fig. 1f, g). At 14 dpi, ADAMTSL2 protein in injured TA muscle was increased by 1.8-fold compared to the uninjured control. Adamtsl2 gene expression, however, was induced already by 3.1-fold at 4 dpi and continued to increase to 4.1-fold at 14 dpi (Fig. 1h). Adamtsl2 mRNA expression was consistent with the induction of ADAMTSL2 expression in differentiating mouse and human myoblasts, which we reported previously19.

a Experimental design for BaCl2 injury in wild type (WT) mice. b, c Representative images of cross-sections of uninjured control (Ctrl) and injured tibialis anterior (TA) muscles at 7 (b) and 14 days post injury (dpi) (c). Sections were stained for ADAMTSL2 (red) and laminin (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). d Quantification of ADAMTSL2 mean fluorescence intensity at 7 and 14 dpi (n = 6 mice, 1-2 fields-of-view). e Quantification of myofiber cross-sectional area (CSA) at 7 and 14 dpi (n = 6 mice, number of myofibers indicated). f Western blot detection of ADAMTSL2 and GAPDH in Ctrl and injured TA muscle extracts at 7 and 14 dpi. g Quantification of fluorescence intensities of ADAMTSL2 bands normalized to GAPDH (n = 3-4 mice). h qRT-PCR quantification of Adamtsl2 mRNA at 4 and 14 dpi normalized to Gapdh (n = 3 mice). i Representative images of TA muscles cross-sections of 8-week-old D2 Ctrl and D2.mdx mice. Sections were stained for ADAMTSL2 (red) and laminin (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). j Quantification of ADAMTSL2 mean fluorescence intensities from D2 and D2.mdx TA muscles (n = 3 mice). k qRT-PCR quantification of Adamtsl2 mRNA normalized to Gapdh (n = 4 mice). l Analysis of muscle regeneration after cardiotoxin injury. The percentage of positive cells per gene is shown. Total number of analyzed cells/time point: 0 = 5670, 0.5 dpi = 3510, 2 dpi = 8395, 3.5 dpi = 11251, 5 dpi = 9491, 10 dpi = 6214, 21 dpi = 8662. m, n Expression levels of Adamtsl2 (m) and Pax7 (n) after cardiotoxin injury. Data points represent normalized and scaled mRNA levels from individual cells. Cells with an expression value of 0 are not shown. Bars in d, g, h, j, k represent mean values and whiskers the standard deviation. Boxes in m, n represent 25th – 50th percentile range, whiskers in e, m, n the standard deviation, and horizontal lines the mean value. Statistical significance in d, e, g, h, j, k was calculated using a Student’s t test and in m, n using a one-way ANOVA with posthoc Tukey test. Scale bars in b, c, i = 50 μm. Graphs were generated using CorelDRAW and OriginPro.

In addition to the acute BaCl2 injury model, we also examined ADAMTSL2 localization and gene expression in D2.mdx mice. D2.mdx mice are an established DMD model due to dystrophin deficiency and represent a state of severe chronic muscle injury42. ADAMTSL2 protein localization was disrupted in 8-week-old D2.mdx TA muscles, which correlated with disrupted TA architecture indicated by irregular laminin staining and an increased number of DAPI-positive cells (Fig. 1i). Quantification showed a 2.4-fold reduction in ADAMTSL2 mean fluorescence intensity in D2.mdx mice compared to TA muscles from the wild type D2 strain (DBA/2J) (Fig. 1j). Similar to the induction of Adamtsl2 mRNA expression observed after BaCl2 injury, Adamtsl2 mRNA was increased by 3.2-fold in TA muscles of D2.mdx mice (Fig. 1k). To investigate Adamtsl2 upregulation in the context of other muscle injury models, we mined publicly available single-cell transcriptomics data from a muscle regeneration time course after cardiotoxin injury (GEO dataset GSE138826)43,44. When comparing the percentage of Adamtsl2-positive cells with the dynamic changes of other genes known to be regulated during muscle regeneration, we observed a strong reduction in the percentage of positive cells for all genes shortly after injury (Fig. 1l). From 2 dpi onwards, the percentages of Pax7-, Myod1-, and Myog-positive cells increased strongly until 10 dpi and decreased again by 21 dpi. In contrast, the percentage of Adamtsl2-positive cells started increasing at 5 dpi and were at their highest percentage at 21 dpi, comparable to the percentages in the uninjured muscle. These dynamic changes were also observed when analyzing the expression levels of Adamtsl2 and Pax7 in the respective positive cells during muscle regeneration after cardiotoxin injury (Fig. 1m, n). We performed a similar analysis of Adamtsl2 expression in a bulk RNA-sequencing data set from a muscle regeneration time course after freeze injury (GEO dataset GSE101900), but did not observe regulation of Adamtsl2 expression compared to the uninjured controls, despite a strong induction of Myod1 expression (data not shown)44.

Together, our data show that ADAMTSL2 protein localization was disrupted and reduced in models of acute and chronic skeletal muscle injury, likely as a result of the ECM turnover that is required for muscle regeneration. Adamtsl2 mRNA expression was induced in both models, as well as after cardiotoxin injury, suggesting a role for de-novo synthesized ADAMTSL2 in restoring contractile myofibers during muscle regeneration after injury.

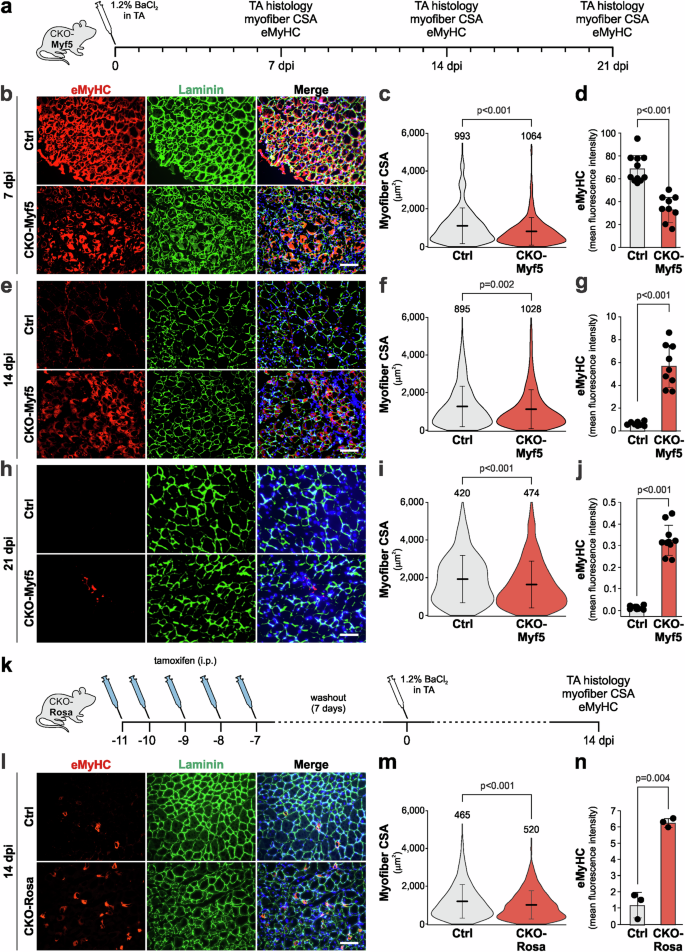

ADAMTSL2 deletion in myoblast precursor cells resulted in delayed muscle regeneration after BaCl2 injury

To directly test the role of myoblast-derived ADAMTSL2 during muscle regeneration following BaCl2 injury, we deleted Adamtsl2 in myogenic precursor cells, which are the source of myoblasts, by cross-breeding a previously validated conditional Adamtsl2 allele with a mouse strain that expresses Cre recombinase under the control of the Myf5 promoter resulting in CKO-Myf5 mice19,45,46. Adamtsl2 was inactivated in the developmental myotomes that form the precursors of axial and appendicular muscles, including myogenic precursor cells and satellite cells and their descendants47. Efficient depletion of ADAMTSL2 mRNA and protein in CKO-Myf5 TA muscles and delayed differentiation of primary CKO-Myf5 myoblasts was demonstrated previously19. We induced BaCl2 injury to CKO-Myf5 TA muscles and followed muscle regeneration over time using myofiber CSA and eMyHC immunostaining, a transient marker for regenerating myofibers (Fig. 2a)24,48. At 7 dpi, myofiber CSA and eMyHC immunostaining were both significantly reduced in injured CKO-Myf5 TA muscles compared to injured controls (Fig. 2b–d). At 14 dpi, myofiber CSA was still reduced in injured CKO-Myf5 TA muscles (Fig. 2e, f). In addition, eMyHC staining persisted in the regenerating CKO-Myf5 TA muscles, resulting in a 5.7-fold increase in eMyHC mean fluorescence intensity compared to injured control TA (Fig. 2e, g). The relative increase was predominantly driven by a sharp decrease in the eMyHC signal from the control TA muscles, which is consistent with previously published data, while in regenerating CKO-Myf5 TA muscles the eMyHC signal declined more modestly between 7 and 14 dpi25. At 21 dpi, we only observed residual staining for eMyHC in the injured Ctrl TA muscles, while eMyHC was still present in regenerating CKO-Myf5 TA muscles and the myofiber CSA was reduced (Fig. 2h–j). However, the eMyHC staining in CKO-Myf5 muscles was decreased by ~ 10-fold compared to the 14 dpi time point (Fig. 2j). This suggested that eMyHC in the regenerating CKO-Myf5 TA muscles may eventually disappear and delayed muscle regeneration may be completed.

a Experimental design for BaCl2 injury in CKO-Myf5 mice. b Representative images of cross-sections of inured control (Ctrl, Adamtsl2flox/flox) and CKO-Myf5 (Adamtsl2flox/flox;Myf5-Cre) TA muscles at 7 dpi. Sections were stained for eMyHC (red) and laminin (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). c Quantification of myofiber CSA at 7 dpi (n = 6 mice, number of measured myofibers indicated). d Quantification of eMyHC mean fluorescence intensity at 7 dpi (n = 6 mice, 1-2 fields-of-view). e Representative images of cross-sections of inured Ctrl and CKO-Myf5 TA muscles at 14 dpi. Sections were stained for eMyHC (red) and laminin (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). f Quantification of myofiber CSA at 14 dpi (n = 6 mice, number of measured myofibers indicated). g Quantification of eMyHC mean fluorescence intensity at 14 dpi (n = 6 mice, 1-2 fields-of-view). h Representative images of cross-sections of injured Ctrl and CKO-Myf5 TA muscles at 21 dpi. Sections were stained for eMyHC (red) and laminin (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). i Quantification of myofiber CSA at 21 dpi (n = 5 mice, number of measured myofibers indicated). j Quantification of eMyHC mean fluorescence intensity at 21 dpi (n = 5 mice, 2 fields-of-view/muscle). k Experimental design for tamoxifen-induced Adamtsl2 ablation in CKO-Rosa mice. l Representative images of cross-sections of injured Ctrl (Adamtsl2flox/flox) and CKO-Rosa (Adamtsl2flox/flox;Rosa-CreERT) TA muscles at 14 dpi. Sections were stained for ADAMTSL2 (red) and laminin (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). m Quantification of myofiber CSA at 14 dpi (n = 3 mice, number of measured myofibers indicated). n Quantification of eMyHC mean fluorescence intensity at 14 dpi (n = 3 mice). Bars in d, g, j, n represent mean values, whiskers the standard deviation. Lines in c, f, i, m represent mean values, and whiskers the standard deviation. Statistical significance in c, d, f, g, i, j, m, n was calculated using a Student’s t-test. Scale bars in b, e, h, l = 100 μm. Graphs were generated using CorelDRAW and OriginPro.

Publicly available single cell transcriptomics data suggest that ADAMTSL2 is also expressed in FAPs, which play an important role during muscle regeneration49,50,51. To investigate, the contributions of ADAMTSL2 from FAPs and other potential cellular sources to muscle regeneration, we cross-bred the conditional Adamtsl2 allele with a tamoxifen-inducible Rosa26-CreERT allele, resulting in CKO-Rosa mice, and thus deleted ADAMTSL2 in all (muscle) cells prior to BaCl2 injury by sequential tamoxifen injection (Fig. 2k). ADAMTSL2-deficient CKO-Rosa TA muscles were then analyzed at 14 dpi when we observed the largest differences in eMyHC staining in CKO-Myf5 regenerating muscle. We observed a significant decrease in myofiber CSA and a significant ~6-fold increase in eMyHC staining in regenerating CKO-Rosa TA muscles compared to injured controls (Fig. 2l–m). The magnitude of the increase in eMyHC was similar to the increase observed in CKO-Myf5 TAs at 14 dpi (5.2-fold), suggesting that the delayed regeneration was predominantly driven by ADAMTSL2 originating from myoblasts.

Altogether, our results suggest that myoblast-derived ADAMTSL2 promotes muscle regeneration after injury, and that in its absence, the magnitude or duration of the regenerative response was delayed.

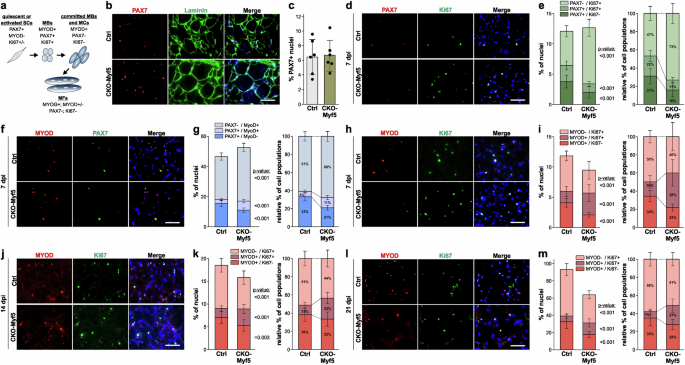

ADAMTSL2 deficiency attenuates myoblast differentiation during muscle regeneration after BaCl2 injury

To elucidate potential mechanisms of how ADAMTSL2-deficiency in myogenic progenitor cells delayed muscle regeneration after BaCl2 injury, we followed myogenic differentiation by comparing the proportions of proliferating and non-proliferating PAX7-positive muscle stem cells and MYOD-positive myoblasts, respectively, over time (Fig. 3a). At baseline, we did not detect a difference in the percentage of PAX7-positive muscle stem cells between control and CKO-Myf5 TA muscles, suggesting that ADAMTSL2 does not regulate the number of muscle stem cells in uninjured muscle (Fig. 3b, c). Next, we determined how ADAMTSL2-deficiency affected PAX7-positive muscle stem cell populations after BaCl2 injury. At 7 dpi, ADAMTSL2-deficiency significantly reduced the number of PAX7-positive cells for both, quiescent (PAX7+/Ki67−) and proliferating (PAX7+/Ki67+) muscle stem cells and increased the number of PAX7-negative proliferating cells (PAX7-/Ki67+), which include proliferating myoblasts, immune cells, and FAPs (Fig. 3d, e). This was most apparent when comparing the relative proportions of the different PAX7-positive cell populations, where the total number of cells was set to 100% (Fig. 3e, right). The proportion of proliferating cells showed a 1.6-fold increase, while the quiescent and proliferating muscle stem cells decreased by 2-fold. In line with these data, we also observed a decrease in the PAX7+/MYOD- population in regenerating CKO-Myf5 muscles at 7 dpi, which represent self-renewing satellite cells and an expansion of the PAX7+/MYOD+ and PAX7-/MYOD+ myoblast population, which represent the myoblast population (Fig. 3f, g)52.

a Cell populations and marker genes during myogenic differentiation. SCs, satellite cells; MBs, myoblasts; MCs, myocytes; MFs, myofibers. b Representative images of cross-sections of uninjured control (Ctrl) and CKO-Myf5 TA stained for PAX7 (red), laminin (green), and nuclei (blue). c Quantification of percentage of PAX7+ nuclei (n = 3, 2 fields-of-view). d Representative images of cross-sections of injured Ctrl or CKO-Myf5 TA at 7 dpi stained for PAX7 (red), Ki67 (green), and nuclei (blue). e Bar graphs representing PAX7+/Ki67+ and PAX7+/Ki67- muscle stem cells as percentage of total nuclei (left) and relative to each other (right) (n = 6 mice, 2-fields-of-view). f Representative images of cross-sections of injured Ctrl or CKO-Myf5 TA at 7 dpi stained for MyoD (red), PAX7 (green), and nuclei (blue). g Bar graphs representing PAX7-/MYOD+, PAX7+/MYOD-, and PAX7+/MYOD- cells as percentage of total nuclei (left) and relative to each other (right) (n = 6 mice, 2 fields-of-view). h Representative images of cross-sections of injured Ctrl or CKO-Myf5 TA at 7 dpi stained for MYOD (red), Ki67 (green), and nuclei (blue). i Bar graphs representing MYOD+/Ki67+ and MYOD+/Ki67- myoblasts as percentage of total nuclei (left) and relative to each other (right) (n = 6 mice, 2 fields-of-view). j Representative images of cross-sections of injured Ctrl or CKO-Myf5 TA at 14 dpi stained for MYOD (red), Ki67 (green), and nuclei (blue). k Bar graphs representing MYOD+/Ki67+ and MYOD+/Ki67- myoblasts as percentage of total nuclei (left) and relative to each other (right) (n = 6 mice, 2 fields-of-view). l Representative images of cross-sections of injured Ctrl or CKO-Myf5 TA at 21 dpi stained for MYOD (red), Ki67 (green), and nuclei (blue). m Bar graphs representing MYOD+/Ki67+ and MYOD+/Ki67- myoblasts as percentage of total nuclei (left) and relative to each other (right) (n = 6 mice, 2 fields of view). Bars in c, e, g, i, k, m represent mean values and whiskers standard deviations. Statistical significance in c, e, g, I, k, m was calculated using a Student’s t-test. Scale bars in b, d, f, h, j, i = 50 μm. Graphs were generated using CorelDRAW and OriginPro.

We then analyzed proliferating and non-proliferating MYOD-positive myoblasts after BaCl2 injury to determine if the differentiation of myoblasts to myocytes, which requires cell cycle exit and thus cessation of proliferation, was compromised15,53. While the number of proliferating cells (MYOD-/Ki67+), such as immune cells or FAPs, was reduced in CKO-Myf5 TA muscles at 7 dpi, the number of proliferating myoblasts (MYOD+/Ki67+) was increased by 2.2-fold at the expense of committed non-proliferating myoblasts (MYOD+/Ki67-), which were decreased by 1.6-fold (Fig. 3h, i). At 14 dpi and 21 dpi, the number of proliferating cells (MYOD-/Ki67+) and committed myoblasts (MYOD+/Ki67-) were both reduced in regenerating CKO-Myf5 muscles and the number of proliferating myoblasts (MYOD+/Ki67+) remained increased (Fig. 3j-m). Together, these findings indicate that ADAMTSL2-deficiency resulted in a shift from committed myoblasts (MYOD+/Ki67-), which excited the cell cycle and could contribute to regenerating myofibers, towards proliferating myoblasts (MYOD+/Ki67+), which were still proliferating and not contributing to myofiber regeneration. The mechanistic observations therefore show that ADAMTSL2 depletion delays myogenic differentiation during muscle regeneration both by reducing the number of muscle stem cells and inhibiting their differentiation towards committed myoblasts and myocytes. The results therefore support the hypothesis that ADAMTSL2 plays a pro-myogenic role during muscle regeneration after BaCl2 injury.

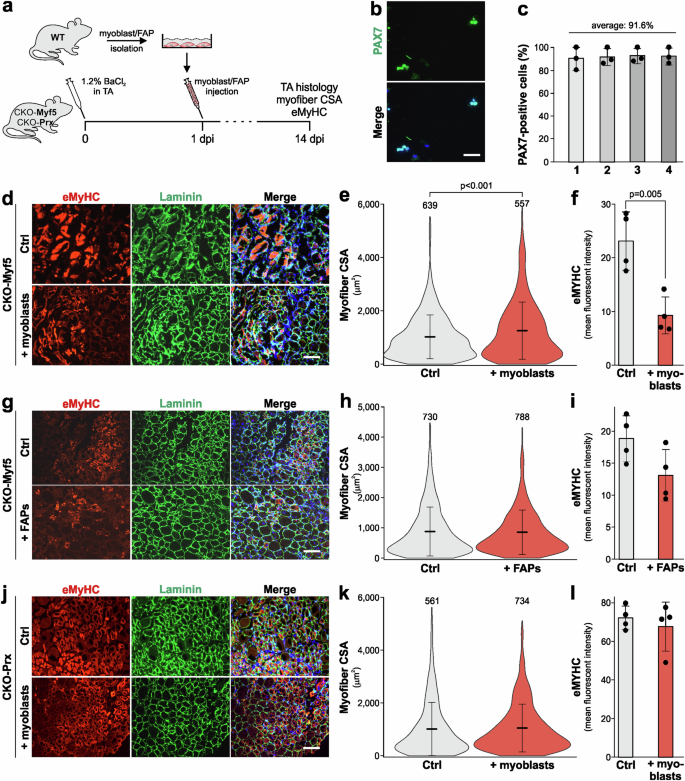

Delivery of ADAMTSL2-expressing myoblasts or recombinant ADAMTSL2 protein domains promoted muscle regeneration after BaCl2 injury

To demonstrate the therapeutic potential of exogenous ADAMTSL2, we delivered ADAMTSL2-expressing myoblasts into BaCl2-injured CKO-Myf5 TA muscles. 1 × 106 freshly isolated primary wild type myoblasts were injected into CKO-Myf5 TA muscles at 1 dpi, and muscle regeneration was analyzed at 14 dpi (Fig. 4a)54,55. Primary myoblasts were isolated via a pre-plating method that yielded a purity of >90% based on PAX7 immunostaining, which labels quiescent and activated satellite cells and myoblasts (Fig. 4b, c). After injection of wild type myoblasts into injured CKO-Myf5 TA muscles, we observed increased myofiber CSA and decreased eMyHC staining at 14 dpi compared to uninjected injured CKO-Myf5 TA controls, indicating accelerated regeneration (Fig. 4d–f). When 1 × 106 wild type FAPs, which also express ADAMTSL2, were injected into injured CKO-Myf5 TA muscles, changes in myofiber CSA or eMyHC staining intensity were not observed (Fig. 4g–i). This suggested that ADAMTSL2 originating from FAPs or other cell types did not compensate for the loss of ADAMTSL2 in myogenic progenitor cells of CKO-Myf5 muscles. In a control experiment, we injected 1 × 106 wild type myoblasts into CKO-Prx TA muscles after BaCl2-injury, a model where ADAMTSL2 was deleted in muscle connective tissue cells, including FAPs, but not in myogenic precursor cells56. Changes in myofiber CSA or eMyHC mean fluorescence intensity compared to uninjected injured control CKO-Prx TA muscles were not observed (Fig. 4j–l). These data indicated that exogenous myoblasts cannot further augment muscle regeneration in the presence of endogenous ADAMTSL2-secreting wild type myoblasts.

a Experimental design for wild type myoblast and FAP injection in CKO-Myf5 and CKO-Prx mice. b Representative images of freshly isolated primary myoblasts stained with for PAX7. c Quantification of PAX7 positive cells from b from n = 4 independent primary myoblast isolations. d Representative images of cross-sections of injured DMEM injected (Ctrl) or myoblast injected CKO-Myf5 TA muscles at 14 dpi. Sections were stained for eMyHC (red) and laminin (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). e Quantification of myofiber CSA at 14 dpi (n = 4 mice, number of measured myofibers indicated). f Quantification of eMyHC mean fluorescence intensity at 7 dpi (n = 4 mice). g Representative images of cross-sections of injured DMEM injected or FAP-injected CKO-Myf5 TA muscles at 14 dpi. Sections were stained for eMyHC (red) and laminin (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). h Quantification of myofiber CSA at 14 dpi (n = 4 mice, number of measured myofibers indicated above the violin plots). i Quantification of eMyHC mean fluorescence intensity at 14 dpi (n = 4 mice). j Representative images of cross-sections of injured DMEM injected (Ctrl) or myoblast injected CKO-Prx TA muscles at 14 dpi. Sections were stained for eMyHC (red) and laminin (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). k Quantification of myofiber CSA at 14 dpi (n = 4 mice, number of measured myofibers indicated). l Quantification of eMyHC mean fluorescence intensity at 14 dpi (n = 4 mice). Horizontal lines in e, h, k represent the mean value and whiskers the standard deviation. Bars in c, f, i, l represent mean values and whiskers the standard deviation. Statistical significance in c, e, f, h, i, k, l was calculated using a Student’s t test. Scale bars in b = 50 μm, in d, g, j = 100 μm. Graphs were generated using CorelDRAW and OriginPro.

Altogether, these data suggest that ADAMTSL2 originating from wild type myoblasts, but not other cell types, rescued muscle regeneration after injury in CKO-Myf5 TA muscles and thus compensated for ADAMTSL2-deficiency in myogenic progenitor cells.

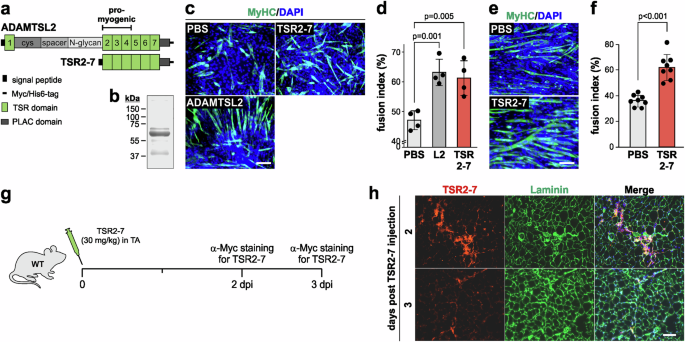

Next, we investigated whether intramuscular delivery of a pro-myogenic recombinant ADAMTSL2 peptide can rescue delayed regeneration in CKO-Myf5 TA and accelerate muscle regeneration in wild type mice after BaCl2 injury. To address this, we purified the ADAMTSL2 TSR2-7 fragment, which contains the previously identified pro-myogenic ADAMTSL2 domains (Fig. 5a, b)19. To confirm that TSR2-7 promoted myoblast differentiation in vitro, C2C12 myoblasts were differentiated in the presence of purified recombinant full-length ADAMTSL2 or TSR2-7 (Fig. 5c, d). The fusion index, which is the percentage of nuclei within myosin heavy chain-positive multinucleated myotubes, was quantified. Both proteins, ADAMTSL2 and TSR2-7 increased the fusion index by 1.3-fold, which agreed with our previously published data (Fig. 5d)19. This indicated that the pro-myogenic activity of ADAMTSL2 is fully contained within the TSR2-7 domains. Differentiating primary mouse myoblasts in the presence of TSR2-7 exhibited an even more pronounced 1.7-fold increase in the fusion index (Fig. 5e, f). ADAMTSL2 bioavailability after intramuscular injection was then determined by following the fate of purified Myc-tagged TSR2-7 after injection of 30 mg/kg into uninjured wild type TA muscle (Fig. 5g). At 2 days after TSR2-7 injection, a robust signal originated from α-Myc immunostaining in TA cross-sections (Fig. 5h, top panels). At 3 days after injection, α-Myc signal intensity in the TA muscle was significantly reduced, suggesting degradation or clearance (Fig. 5f, bottom panels). Collectively, these data show that the ADAMTSL2 TSR2-7 domains promote myoblast differentiation and can be detected in muscle for at least 2 days post injection.

a Domain organization of full-length ADAMTSL2 and recombinant TSR2-7. The location of the pro-myogenic domains is indicated. b Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE after separation of 5 μg purified TSR2-7 (predicted molecular weight: 50.2 kDa). c C2C12 myoblast differentiation in the presence of 100 μg recombinant ADAMTSL2 or TSR2-7 protein. Myotubes were stained for myosin heavy chain (MyHC, green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). d Quantification of the percentage of nuclei within multinucleated MyHC-positive myotubes (fusion index) in c (n = 4 independent experiments). e Differentiation of primary mouse myoblasts in the presence of 100 μg recombinant TSR2-7 protein. Myotubes were stained for MyHC (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). f Quantification of the fusion index from e (n = 4 independent experiments, 2 fields-of-view). g Experimental design for TSR2-7 protein injection in wild type (WT) mice. h Representative images of TA cross-sections at 2 and 3 days after TSR2-7 injection. Sections were stained for the Myc-tag of TSR2-7 (red) and laminin (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Bars in d, f represent mean values and whiskers the standard deviation. Statistical significance in d, f was calculated using a Student’s t-test. Scale bars in c, e, h = 100 μm. Graphs were generated using CorelDRAW and OriginPro.

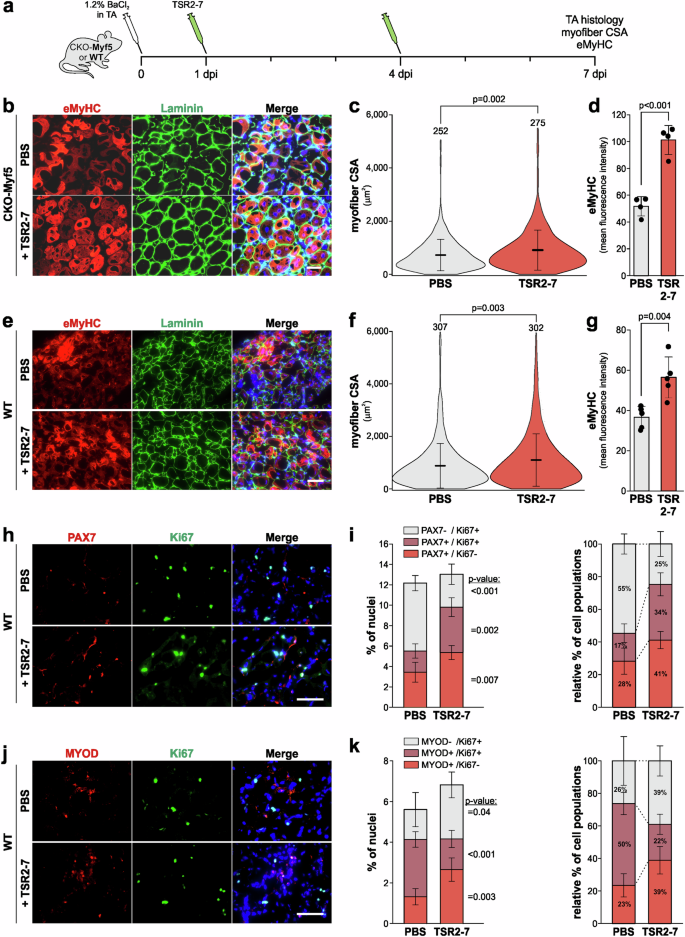

Based on the TSR2-7 bioavailability data shown in Fig. 5, we injected 30 mg/kg TSR2-7 or an equal volume of PBS in BaCl2-injured CKO-Myf5 TA muscle at 1 and 4 dpi for a total of 2 injections and analyzed muscle regeneration at 7 dpi (Fig. 6a). This injection schedule also minimized possible muscle damage due to repeated injections and avoided potential deleterious effects of accumulating TSR2-7 protein in muscle tissue. After TSR2-7 injection, we observed increased myofiber CSA and increased eMyHC mean fluorescence intensity in TRS2-7-injected compared to PBS-injected CKO-Myf5 TA muscles (Fig. 6b–d). In addition, the architecture of the laminin-positive basement membrane that surrounds individual myofibers, was improved when compared to the fragmented appearance in injured CKO-Myf5 TA muscles after PBS injection (Fig. 6b). To determine whether recombinant TSR2-7 can promote muscle regeneration in wild type mice, we used the same experimental design of BaCl2 injury followed by two TSR2-7 injections and analysis of muscle regeneration at 7 dpi (Fig. 6a). Consistent with the results in CKO-Myf5 mice, we observed significantly increased myofiber CSA and eMyHC mean fluorescence intensity after TSR2-7-injection in wild type TA muscles compared to PBS-injected controls (Fig. 6e–g). To explore potential effects of TSR2-7 injection on key PAX7- and MYOD-positive cell populations, we quantified the proportion of proliferating and non-proliferating PAX7- or MYOD-positive cells. After TSR2-7 injection, we observed a 1.6-fold and 2.1-fold increase in quiescent (PAX7+/Ki67-) and proliferating (PAX7+/Ki67+) muscle stem cells, respectively, suggesting increased muscle stem cell activation and proliferation (Fig. 6h, i). In addition, we observed a 2-fold increase in committed myoblasts (MYOD+/Ki67-) and a concomitant 1.9-fold decrease in proliferating myoblasts (MYOD+/Ki67+) indicating that TSR2-7 induced a shift from proliferating to differentiating myoblasts (Fig. 6j, k). Collectively, these data suggest that recombinant TSR2-7 promotes muscle regeneration by inducing the differentiation of myoblasts into myocytes, which subsequently fuse to reinforce existing myofibers or to generate new myofibers.

a Experimental design for TSR2-7 injection in wild type and CKO-Myf5 mice after BaCl2 injury. b Representative images of cross-sections of PBS or TSR2-7 injected CKO-Myf5 TA muscles at 7 dpi. Sections were stained for eMyHC (red) and laminin (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). c Quantification of myofiber CSA at 7 dpi (n = 4 mice, number of measured myofibers indicated). d Quantification of eMyHC mean fluorescence intensity at 7 dpi (n = 4 mice). e Representative images of cross-sections of PBS or TSR2-7 injected wild type TA muscles at 7 dpi. Sections were stained for eMyHC (red) and laminin (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). f Quantification of myofiber CSA at 7 dpi (n = 5 mice, number of measured myofibers indicated). g Quantification of eMyHC mean fluorescence intensity at 7 dpi (n = 5). h Representative images of cross-sections of injured Ctrl or CKO-Myf5 TA muscles at 7 dpi. Sections were stained for PAX7 (red) and Ki67 (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). i Bar graphs representing PAX7+/Ki67+ and PAX7+/Ki67- muscle stem cells as a percentage of total nuclei (left) and relative to each other (right) (n = 3-4 mice, 2 fields of view). j Representative images of cross-sections of injured Ctrl or CKO-Myf5 TA muscles at 7 dpi. Sections were stained for MYOD (red) and Ki67 (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). k Bar graphs representing MYOD+/Ki67+ and MYOD+/Ki67- myoblasts as a percentage of total nuclei (left) and relative to each other (right) (n = 3-4 mice, 2 fields of view). Horizontal lines in c, f represent the mean value and whiskers the standard deviation. Bars in d, g, i, k represent mean values and whiskers the standard deviation. Statistical significance in d, g, i, k was calculated using a Student’s t-test. Scale bars in b, e, h, j = 50 μm. Graphs were generated using CorelDRAW and OriginPro.

Discussion

Skeletal muscle regeneration requires a well-orchestrated sequence of events including the activation of muscle stem cells and their subsequent myogenic differentiation to restore injured or lost myofibers and allow injured muscles to regain their contractility and strength. Secreted ECM proteins and ECM-associated signaling molecules, such as fibronectin, thrombospondins, WNT ligands, or members of the TGFβ family regulate these processes57,58,59,60. Our previous findings have demonstrated that ADAMTSL2, a regulatory ECM protein, modulated WNT signaling to promote myoblast differentiation16. Genetic mutations of ADAMTSL2 are also associated with apparent skeletal muscle hypertrophy in geleophysic dysplasia suggesting a role for ADAMTSL2 in muscle development or homeostasis61. Together, these insights motivated our investigation of the function of ADAMTSL2 during skeletal muscle regeneration, where the differentiation of myoblasts is a critical step. Our results revealed that ADAMTSL2 expression was induced after muscle injury and that ADAMTSL2 inactivation in myogenic progenitor cells, which are the precursors of myoblasts, delayed muscle regeneration. Mechanistically, ADAMTSL2-deficiency resulted in a decrease of committed MYOD-positive myoblasts that have exited the cell cycle and a concomitant increase in proliferating, non-differentiating myoblasts. Such a phenotypic switch may explain the delay in muscle regeneration that we did observe in CKO-Myf5 TA muscles after BaCl2 injury. Finally, we demonstrated the therapeutic potential of the recombinant pro-myogenic ADAMTSL2 TSR2-7 domains, which accelerated muscle regeneration after BaCl2 injury.

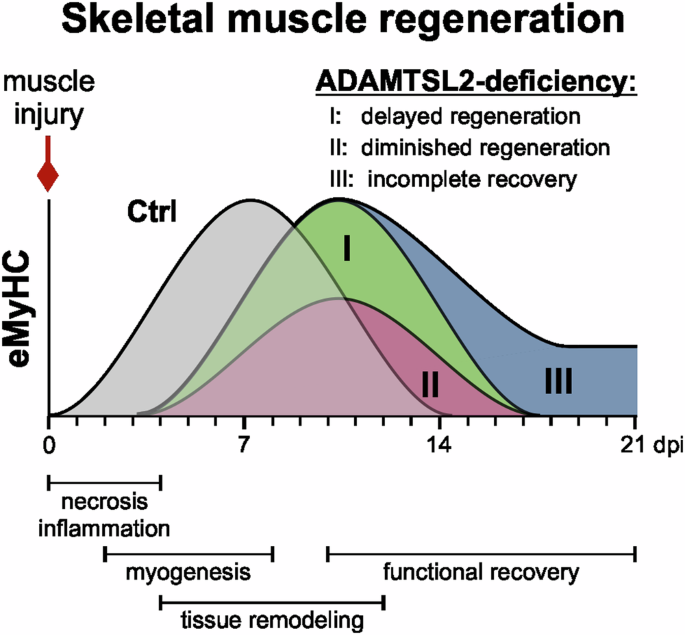

Muscle regeneration after injury follows a sequence of three partially overlapping phases (Fig. 7). A necrotic and inflammatory phase (~0–4 dpi in mice) is followed by the activation of muscle stem cells and their subsequent myogenic differentiation, which results in the regeneration of myofibers (~2–14 dpi)23,62. In the remodeling phase (~4–21 dpi), myofibers mature and activated FAPs contribute to the restoration of muscle architecture and contractile function. When ADAMTSL2 was inactivated in myogenic progenitor cells using Myf5-Cre, we observed a delay in muscle regeneration indicated by reduced expression of transient eMyHC at 7 dpi and persistent eMyHC expression at 14 dpi (Fig. 7, scenario I/II). Further reduction of eMyHC staining in CKO-Myf5 muscles at 21 dpi suggested that muscle regeneration eventually comes to completion, supporting a function for ADAMTSL2 in accelerating muscle regeneration rather than contributing to the recovery phase. Since the number of PAX7-positive muscle stem cells was not altered under homeostatic conditions, the observed delay in muscle regeneration after injury in CKO-Myf5 TA muscles could be caused by reduced activation or proliferation of muscle stem cells, impaired differentiation of myoblasts, or a combination of both. Consistent with these possibilities, the number of proliferating PAX7-positive cells and committed MYOD-positive myoblasts was reduced in regenerating CKO-Myf5 TAs at 7 dpi. Collectively, these changes in myogenic cell populations are predicted to result in fewer myoblasts available for the regeneration of myofibers and would explain the observed delay in muscle regeneration in ADAMTSL2-deficient muscles. While the number of committed myoblasts was decreased, the number of proliferating, non-differentiating myoblasts was increased in regenerating CKO-Myf5 TA muscles. This indicated that ADAMTSL2-deficiency in myogenic progenitor cells may predominantly affect the capability of proliferating MYOD-positive myoblasts to exit the cell cycle, a prerequisite for entering the differentiation trajectory towards myocytes and myofibers. This interpretation aligns with our previous findings, where ADAMTSL2 promoted myoblast-to-myocyte differentiation in a WNT-dependent manner19. We showed that ADAMTSL2-deficient C2C12 and primary myoblasts continued to proliferate even after serum-reduction, which robustly induced cell cycle exit, myoblast differentiation and myotube formation in wild type myoblasts19. Collectively, our data are consistent with ADAMTSL2 promoting myoblast-to-myocyte differentiation, likely at the level of myoblasts exiting the cell cycle or shortly thereafter. Alternatively, a later step in myoblast or myocyte differentiation could be regulated by ADAMTSL2, which negatively feeds back on the capacity of myoblasts to exit the cell cycle. However, such a later function for ADAMTSL2 requires additional experimental evidence. One limitation of our study is the use of a non-inducible Myf5-Cre transgene to inactivate Adamtsl246. In this system, Adamtsl2 was inactivated in the myotomes during embryonic development from which axial and appendicular muscles arise, including myogenic progenitor cells and adult muscle stem cells47. Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility of a developmental role for ADAMTSL2 in muscle formation that could compromise adult muscle regeneration without a direct involvement of ADAMTSL2. However, the fact that we could rescue or promote muscle regeneration with recombinant ADAMTSL2 TSR2-7 protein in CKO-Myf5 and wild type TA muscle, supports a more direct role for adult ADAMTSL2 in regulating muscle regeneration after injury.

ADAMTSL2 regulates muscle regeneration by accelerating myoblast-to-myocyte differentiation, a critical step in the regeneration of contractile myofibers. Our data are consistent with delayed muscle regeneration of ADAMTSL2-deficient muscle compared the regeneration of wild type muscle (scenario I) or with a delayed and diminished regenerative response that still would result in complete muscle regeneration (scenario II). Scenario II is supported by our data since eMyHC staining continued to decline rapidly through 21 dpi in regenerating CKO-Myf5 TA muscles. In an alternative scenario, muscle regeneration would be delayed and does not fully resolve resulting in incomplete “chronic” muscle regeneration (scenario III). Graphics were generated using CorelDRAW and OriginPro.

During skeletal muscle regeneration, FAPs could be an additional source of ADAMTSL2 based on its expression reported in single cell RNA sequencing datasets49,50. However, when we deleted ADAMTSL2 with inducible Rosa26-Cre in all (muscle) cells, including FAPs, we did not observe an exacerbation in the delay in muscle regeneration compared to CKO-Myf5 TA muscles, where ADAMTSL2 was absent only in myogenic progenitor cells. This could suggest that myoblast-derived ADAMTSL2 acts cell autonomously and has a primary role in regulating the dynamics of muscle regeneration. Alternatively, FAP-derived ADAMTSL2 could regulate processes in the remodeling or maturation phase after myogenesis is completed, including the formation of a compliant muscle ECM. Since fibroblast-derived ADAMTSL2 showed anti-fibrotic properties by negatively regulating TGFβ signaling in other tissues, it remains to be established if FAP-derived ADAMTSL2 may play a similar role during the resolution phase of muscle regeneration35,39,63. This is in particular relevant since FAPs contribute to muscle degeneration as a source for adipocytes in fatty infiltrates or fibroblasts in muscle fibrosis. However, BaCl2 injury typically does not induce adipogenic of fibrogenic differentiation of FAPs and is an inadequate model to address the role of FAP-derived ADAMTSL2 during muscle regeneration23. Collectively, our data support the idea that myoblast-derived ADAMTSL2 represents the main pool of ADAMTSL2 that contributes to muscle regeneration after injury.

To determine the therapeutic potential of ADAMTSL2, we delivered myoblast-derived or recombinant ADAMTSL2 and followed muscle regeneration after acute injury over time. Consistent with the delayed regeneration that we have observed in ADAMTSL2-deficient muscle, delivery of a recombinant ADAMTSL2 protein containing the pro-myogenic ADAMTSL2 domains TSR2-4 accelerated muscle regeneration in wild type mice as indicated by increased myofiber CSA and eMyHC-positive (i.e. regenerating) myofibers. This was likely achieved by promoting the differentiation of myoblasts, which increased the number of committed MYOD-positive myoblasts available for further differentiation ultimately supporting the regeneration of myofibers. In addition, injection of the ADAMTSL2 TSR2-7 domains also increased myofiber CSA and eMyHC staining intensity in CKO-Myf5 TA muscles after injury. This apparent phenotypic rescue suggested that ADAMTSL2-deficient muscle stem cells remained differentiation-competent and that the main role of ADAMTSL2 is to accelerate their differentiation. This interpretation is supported by our published findings that highlight the addition of recombinant ADAMTSL2 proteins rescuing differentiation of ADAMTSL2-deficient C2C12 myoblasts and promoting the differentiation of wild type myoblasts19. Consistent with a pro-myogenic role for myoblast-derived ADAMTSL2, we observed accelerated muscle regeneration after injection of primary wild type myoblasts into injured CKO-Myf5 TA muscles as indicated by an increased myofiber CSA and decreased eMyHC staining. This effect could be explained by an increased number of myoblasts due to the injection of exogenous myoblasts or by an increase in the amount of ADAMTSL2 protein originating from differentiating myoblasts, which could have accelerated the differentiation of endogenous ADAMTSL2-deficient myoblasts. Since the injected myoblasts were unlabeled, we were unable to determine myoblast survival and integration into regenerating myofibers. Based on the literature, most myoblasts disappear within hours or days after injection64,65,66. However, a small, highly active myogenic progenitor cell population that persists and contributes to myofiber regeneration has been described64,67.

Cell transplantation may be more advantageous over recombinant protein injections when the endogenous pool of myoblasts is exhausted or their differentiation potential is compromised. In the context of volumetric muscle loss due to blast injuries, accidents, or surgical resection, for example, significant portions of muscle tissue and corresponding muscle stem cells are lost2,68,69. Treatment of these injuries will likely require the delivery of myoblasts and a bioactive scaffold70. To this end, the differentiation of such myoblasts could be accelerated by co-delivery of pro-myogenic ADAMTSL2 protein domains from other ECM proteins with similar functions. In the case of chronic and systemic myopathies, such as DMD, the targeting of multiple muscles, notably the diaphragm to support respiration, is paramount for any successful therapeutic strategy. Such approaches may be best accomplished by systemic delivery of recombinant myogenic proteins, such as ADAMTSL2 and domains thereof, or its systemic expression in skeletal muscle tissue after adeno-associated viruses (AAV) delivery or other gene-delivery modalities71. Here, ADAMTSL2 or its pro-myogenic domains may serve as an adjunct to increase the efficiency of muscle regeneration in combination with approaches to correct the underlying primary genetic defect, such as micro- or mini-dystrophin delivery71. Promising AAV delivery approaches have advanced to clinical trials for DMD, and ADAMTSL2 or its domains would comply with the size range of viral payloads72,73,74.

In summary, our data demonstrate a role for the regulatory ECM protein ADAMTSL2 in promoting skeletal muscle regeneration and provide a proof-of-concept that ADAMTSL2 or ADAMTSL2-derived protein domains may have therapeutic potential as pro-myogenic biologics. In future experiments, we will explore the therapeutic potential of ADAMTSL2 in clinically relevant injury systems, such as volumetric muscle loss or muscular dystrophies and investigate the role of ADAMTSL2 in FAPs.

Methods

Mouse models

For conditional Adamtsl2 inactivation in myogenic progenitor cells, we combined our previously validated Adamtsl2 allele (Adamtsl2flox/flox), in which exon 5 is flanked by loxP sites and can be excised with Cre-recombinase, with a mouse strain were Cre-recombinase expression is controlled by the Myf5 promoter (B6.129S4-Myf5tm3(cre)Sor/J, Jackson Laboratories #007893)19,45,46. We then generated experimental Adamtsl2flox/flox;Myf5-Cre (CKO-Myf5) and Adamtsl2flox/flox control (Ctrl) mice. Excision of exon 5 causes a frame shift resulting in a premature termination codon. ADAMTSL2 mRNA and protein levels were greatly reduced19,45. To inactivate Adamtsl2 in muscle connective tissue cells or tamoxifen-inducible in all cells, we generated Adamtsl2flox/flox;Prx1-Cre (CKO-Prx) and Adamtsl2flox/flox;Rosa26-CreERT (CKO-Rosa) mice by using the B6.Cg-Tg(Prrx1-cre)1Cjt/J (JAX #005584) or B6.129-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(cre/ERT2)Tyj/J (JAX #008463), respectively75,76. To induce Cre-mediated recombination in CKO-Rosa mice (n = 3), we injected tamoxifen (100 mg/kg in corn oil, Sigma #T-5648) intraperitoneally for five consecutive days followed by a one week washout period prior to skeletal muscle injury. 8-week old male D2.mdx mice (D2.B10-Dmdmdx/J, JAX #013141, n = 4) and male DBA/2J control mice (JAX #000671) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Mice were housed in a temperature-controlled facility with free access to food and water on a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Prior to tissue-harvest, mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation, followed by cervical dislocation. All animal procedures were approved by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (PROTO202000259).

Acute muscle injury model

Mice (n = 3–6, 8 weeks of age, males and females) were anesthetized with isoflurane. The tibialis anterior (TA) muscle was identified by palpation and 50 µl of 1.2% barium chloride (BaCl2, Fisher Chemicals #B21-100C) in deionized water were injected intramuscularly into the TA muscle. The contralateral TA muscle was injected with 50 µl deionized water and served as a control in some experiments. TA muscles were harvested at 4, 7, 14, or 21 dpi for analyses. TSR2-7 (30 mg/kg body weight) injections were performed at 1 and 4 dpi and primary myoblasts or FAPs (1 ×106 cells) were injected at 1 dpi. TAs were harvested for analyses at 7 and 14 dpi, respectively.

Preparation of TA muscle cryosections

Dissected TA muscles were partly embedded in 1 g/ml tragacanth powder gum (Alfa Aesar #AI8502), dissolved in deionized water, in a plastic cassette. TA muscles were then submerged in liquid nitrogen-cooled 2-methylbutane (Sigma Aldrich #M32631) for 2 min and in liquid nitrogen for 1 min. Frozen TA muscles where wrapped in aluminum foil and stored at −80 °C. Prior to sectioning, TA muscles were embedded in optimum cutting temperature compound (OCT, Tissue-Tek Sakura #4583) and cooled to −20 °C. 20 μm sections were cut through the TA mid-belly region with a cryostat (Avantik). Cryosections were then mounted on a frosted glass slide and stored at −80 °C until further use.

Immunofluorescence

Frozen sections were fixed with 4% PFA (MP Biomedicals #150146) for 20 min at RT (RT) and rinsed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min. The tissue was permeabilized for 6 min with chilled methanol (Sigma Aldrich #179337) at −20 °C and rinsed for 10 min in PBS. Antigen-retrieval was performed with 0.01 M citric acid (Fisher BioReagents #BP339) in deionized water by submerging the sections in 90 °C-hot citric acid buffer followed by microwaving for 5 × 1 (10 s on and 50 s off). Sections were cooled down to RT in citric acid for 30 min at RT and rinsed with PBS for 15 min. Sections were blocked with 5% BSA in PBS for 2 h and incubated in primary antibodies diluted 1:200 (except stated otherwise) in PBS against laminin (Novus Biologicals #LAM-89, #NB600-883), ADAMTSL2, eMyHC (DHSB, F1.652, 1:50), Myc-tag (Proteintech, #16286-1-AP), Ki67 (CST #D3B5), PAX7 (DSHB, AB-528428), PAX7 (Proteintech, 20570-1-AP), and MYOD (Santa Cruz #sc32758) overnight at 4 °C. Sections were rinsed 3× with PBS and incubated for 1 h at RT with appropriate fluorophore-tagged secondary antibodies (goat-anti mouse or goat-anti rabbit Rhodamine Red #111–295–144 or #115–295–146 and Alexa Fluor #488 115–545–146 or #111–545–144, Jackson Immuno Research,) at 1:500 dilution. Slides were rinsed 3 ×10 min in PBS and mounted with DAPI-containing Fluoroshield mounting solution (Abcam) and observed in Axio Imager Z1 fluorescence microscope (Zeiss). Images for analyses that captured the injured region (based on disorganized laminin staining or centrally localized nuclei) were taken with a 20× or 40× dry objective (laminin, eMyHC, ADAMTSL2 staining) or a 63 oil-immersion objective (MYOD, PAX7, Ki67 staining) and scale bars added using the ZEN blue software from Zeiss.

Western blotting

Freshly dissected TA muscles were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and minced using a Geno/Grinder (Spex SamplePrep). Pulverized TA muscle tissue was lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Scientific #89901) in an Eppendorf tube for 30 min on ice. Using a sonicator, tissue lysates were sonicated for 10 sec on ice. The lysate was cleared of debris by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C and the protein concentration was determined using a Bradford assay. 50 μg of protein from the TA muscle lysate was separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) followed by transfer onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (EMD Millipore #IPFL00010) at 400 mA for 3 h using a MiniTransblot Module (BioRad). After protein transfer, PVDF membranes were blocked for 2 h at RT or overnight at 4 °C with 5% milk (RPI #MI7200) in PBS supplemented with 0.1% Tween-20 (VWR #0777) (PBST). PVDF membranes were rinsed with PBST for 5 min and incubated with the GAPDH (1:1000 dilution) or α-ADAMTSL2 antibody19. PVDF membranes were rinsed 3 ×5 min with PBST and incubated with secondary antibody (1:10,000 dilution, LI-COR, IRDye680RD/800CW) for 1 h at RT. The membrane was rinsed 3 × 5 min with PBST and 1 × 5 min with water and imaged using an Azure600c imaging system (Azure Biosystems).

Quantitative real time-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Injured and uninjured TA muscles were dissected, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and pulverized using a Geno/Grinder (Spex SamplePrep). Pulverized muscle tissue was resuspended in TRIzol (Life Technologies #15596018) and total mRNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The final mRNA pellet was dissolved in nuclease-free water and mRNA concentration and purity were determined with a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). To eliminate traces of genomic DNA, 1 μg of mRNA was digested with DNaseI (Thermo Scientific #EN0521) and reverse transcribed into cDNA using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems #4368814) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. 10 μl of 1:5 (v/v) diluted cDNA was used for qRT-PCR analysis and mixed with SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystem #10977-015) and gene-specific primers for Adamtsl2 (f: 5’-cttcaactcccgtgtgtatgac-3’, r: 5’- tgtaggtcgcatggcttactg-3’) and Gapdh (f: 5’- agcttcggcacatatttcatctg-3’, r: 5’- cgttcactcccatgacaaaca-3’). The following PCR cycle was used: 48 °C for 30 min, 95 °C for 10 min, and 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 sec and 60 °C for 1 min. Gene expression changes were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method.

ADAMTSL2 TSR2-7 cloning and purification

Mouse ADAMTSL2 TSR2-7 was generated by PCR amplification with a Q5 Hot start high fidelity 2× master mix (NEB #M0494S) using forward primer 5’-acaggatcctggaagctctcgtcccacga-3’ and reverse primer 5’- cggctcgagtgcagggctgcagatcacaggc-3’ and full-length mouse Adamtsl2 as template77. The PCR products were amplified with the following cycle: 98 °C for 30 sec, followed by 34 cycles of 98 °C for 10 sec, 55 °C for 30 sec, and 72 °C for 30 sec/kb, with a final extension of 2 min at 72 °C. The PCR products and a pSecTag 2B vector (ThermoFisher Scientific), which contains a signal peptide for secretion, were digested with BamHI (NEB #R3136T) and XhoI (NEB #R0146L) and ligated with T4 DNA ligase (NEB #M0202S) at 16 °C overnight. The ligated product was transformed in DH5α E. coli competent cells (NEB #C2988) and plated on ampicillin containing agar plates. Positive clones were identified by Sanger DNA sequencing. For protein production, the TSR2-7 plasmid was transfected into HEK293T cells (ATCC) in 10 cm cell culture dishes (Corning #430293) using polyethylenimine (Polysciences #23966). Serum-free medium containing secreted TSR2-7 was collected after 24 h and 48 h post transfection and pooled. Pooled medium was concentrated using a KrosFlo KR2i filtration system (Spectrum labs) and affinity-purified using a Ni-NTA column (GE Healthcare #17-1408-01) connected to a NGC Chromatography System (Bio-Rad). Purified TSR2-7 was dialyzed using Dialysis membrane (Thermo Scientific #66380) at 4 °C with two changes of PBS. The final protein concentration was quantified using a Bradford Assay (Thermo Scientific #1863028). 5 µg of TSR2-7 was resolved by SDS PAGE and stained with SimplyBlue SafeStain (Invitrogen #LC6060). TSR2-7 was stored at −20 °C in aliquots.

Myoblast differentiation

C2C12 myoblasts were purchased from ATCC (CRL-1772) and cultured according to ATCC’s recommendations as previously described19. For the differentiation experiments, 50,000 cells/well were seeded on 8-well chamber slides and after reaching confluence, the growth medium was switched to differentiation medium (Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium, supplemented with 2% horse serum, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 units penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin) and 100 μg ADAMTSL2 or TSR2-7 was added. An equal volume of PBS was used in control conditions. After 3 days, cells were fixed with ice-cold methanol, blocked with 5% BSA in PBS Tween and incubated with a MyHC antibody (DSHB, #MF20, 1:200 in PBS) overnight at 4 °C. An Alexa Fluor-488 conjugated goat-anti-mouse secondary antibody (Jackson Immuno Research, 115-545-146, 1:500 in PBST) was then used for detection and nuclei were stained with DAPI as part of the mounting medium (Invitrogen).

Myoblast isolation for injection

Primary myoblasts were isolated by pre-plating as previously described55. In brief, hind limb muscles from 5 C57BL/6J wild type or Ctrl mice (8 weeks of age, both sexes) were dissected and digested with 0.1% pronase in serum-free DMEM to release myoblasts, which were then transferred into 10 cm cell culture dishes. After 90 min the fibroblasts attached to the plate and myoblasts floated in the medium, which was collected. Myoblasts were pelleted and resuspended in DMEM. Myoblasts were then counted and 1 × 106 myoblasts in DMEM were injected into the TA. An equal volume of DMEM was injected as control. To assess the purity of myoblast isolations, we seeded freshly isolated myoblasts on 8-well chamber slides, immunostained for PAX7, and determined the labeling index.

FAP isolation by magnetic assisted cell sorting

FAPs were isolated as described previously from 4-weeks-old C57BL/6J mice (both sexes) by magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS)78,79. Briefly, hind limb muscles were digested with 2.5 U/mL Dispase II (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 0.2% w/v collagenase type II (Worthington), filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer, pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in 0.5% bovine serum albumin, 2 mM EDTA in PBS and filtered through a 35-μm cell strainer. For negative selection, the muscle cell suspension were incubated with biotin anti-mouse CD31 (BioLegend, 1:150), biotin anti-mouse CD45 (BioLegend, 1:150), and biotin anti-integrin α7 (Miltenyi; 1:10) antibodies, followed by incubation with 10 μL/107 cells streptavidin magnetic beads. Labeled cells were retained on a magnetic LD column (Miltenyi). Cells in the flow through were enriched for SCA1-positive cells (FAPs) by incubation with biotin anti-mouse Ly-6A/E (SCA-1) (BioLegend, 1:75) followed by 10 μL streptavidin beads (1:30) and passage through an LS column (Miltenyi). FAPs were then counted and 1 ×106 FAPs in DMEM/TA were injected into the TA. An equal volume of DMEM only was ijected as control.

Data mining of transcriptomics data sets

Single-cell RNA counts data for cardiotoxin-injured TA muscles were extracted from the GEO dataset GSE13882643. RNA counts and sample metadata were extracted from the deposited AnnotatedDataFrame and used to construct a Seurat (v5.1) object in R(v4.4.1). Following log-normalization and scaling of RNA counts, cells with positive expression for Adamtsl2, Pax7, MyoD1, Myog, and Myh3 were used for data analysis and visualization. In addition, bulk RNA counts data from a time course of muscle regeneration following freeze injury were extracted from the GEO dataset GSE10190044. Fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM)-normalized RNA counts for Adamtsl2 and MyoD1 were used for comparisons.

Statistical analyses

To calculate statistical significance of observed differences, we used a two-tailed Student’s t test or a one-way ANOVA with a posthoc Tukey test and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Calculations and graphing were performed with the OriginPro software (OriginLab). The sample size for each experiment is indicated in the figure legend.

Responses