Navigating the landscape of AI literacy education: insights from a decade of research (2014–2024)

Literature review

AI literacy

AI is a multidisciplinary technology that integrates cognition, machine learning, emotion recognition, human-computer interaction, data storage, and decision-making (Zhang & Lu, 2021). This complex field enables computers to understand and imitate human interactions and behaviors, allowing them to think, react, and perform tasks like humans (Haleem et al., 2022). AI’s emergence has significantly transformed how people live and learn, impacting various fields such as education, healthcare, and finance. Five key AI technologies—complex algorithms, visualization, XR (virtual/augmented/mixed reality), wearable technology, and neuroscience—are widely used in education (Zhai et al., 2021). Due to the adaptability of machine learning algorithms, course content can be customized and personalized according to students’ needs, enhancing their learning experience and quality (Chen et al., 2020). In the pharmaceutical industry, AI can reduce health risks associated with clinical trials, improve the success rate of drug design, and significantly lower costs (Sahu et al., 2022). AI-driven digital marketing is revolutionizing content creation, customer experience management, and consumer conversion strategies (Van Esch, Black, 2021).

To ensure fair integration in the digital environment and promote fairness and respect in professional and personal spheres, every learner must possess “intelligent literacy” (Zhao et al., 2022). Consequently, AI literacy has become a prominent focus in digital literacy education. AI literacy encompasses a set of abilities that enable individuals to critically evaluate AI technologies, communicate and collaborate effectively with AI, and utilize AI as a tool both online and offline (Long & Magerko, 2020). Key aspects of AI literacy include recognizing and understanding AI, using and applying AI, evaluating and creating AI, and understanding AI ethics (Kong et al., 2021; Ng et al., 2021a). Additionally, AI literacy involves ethical understanding and the ethical use of AI (Long & Magerko, 2020). Recently, Kong et al. (2023a) proposed a three-dimensional framework encompassing cognitive, affective, and sociocultural dimensions, acknowledging the broader social impact of AI literacy.

In recent years, research on AI literacy has expanded from primary, secondary, and higher education to include early childhood education. Lee et al. (2021) reported that an online summer course not only enhanced students’ engagement and understanding of AI concepts but also catalyzed changes in attitudes toward AI, fostering future-oriented AI perspectives. Kong et al. (2023a) explored high school students’ acquisition of machine learning and deep learning concepts and examined ethical dilemmas in project-based learning. This study aims to determine whether high school students can be adequately prepared for a future where AI is ubiquitous through tailored AI literacy education. Meanwhile, Su & Yang (2023) evaluated the impact of an eight-week AI literacy program on young children, measuring AI literacy, AI-related creativity, and participants’ perceptions of the AI4KG program. Despite early challenges in shaping an AI instructional framework for young children, it is evident that AI literacy education offers powerful opportunities to develop AI literacy through concepts, practices, and perspectives (Su et al., 2023).

Review studies of AI literacy education

Over the past three years, several literature reviews have been conducted to explore AI literacy education. These reviews encompass students from early childhood education and K-12 schooling to higher education and adult learning. Su et al. (2023) conducted a scoping review analyzing 16 empirical papers published between 2016 and 2022, focusing on AI literacy in early childhood education. Their study addressed curriculum design, use of AI tools, teaching methods, research frameworks, assessment models, and research findings. Similarly, Casal-Otero et al. (2023) conducted a systematic literature review using Scopus to examine 179 papers on AI literacy in K-12 education. They categorize AI literacy into two main areas: learning experiences and theoretical perspectives. Su et al. (2022) derived a series of implications for innovative teaching design in K-12 education, including educational standards, curriculum design, formal/non-formal education, student learning outcomes, teacher professional development, and learning progress. Laupichler et al. (2022) conducted a scoping review of 30 studies, revealing thematic focuses for AI literacy research in higher education and adult education, such as education, AI, K-12, healthcare, and AI ethics.

In AI literacy discourse, academic thinking extends beyond defining AI literacy to include comprehensive research at various educational levels. Based on 30 peer-reviewed articles, Ng et al. (2021b) proposed a comprehensive AI literacy framework with four key dimensions: awareness and understanding, use and application, evaluation and creation, and ethical considerations. Tenório et al., (2023) traced the evolution of AI literacy publications through quantitative analysis, focusing on authorship, geographic distribution, institutional affiliations, publishing channels, collaborative networks, and emerging trends.

Teaching models, tools, and challenges in AI literacy are also important. Before 2021, AI teaching mainly focused on computer science education at the university level. Recently, it has shifted to interdisciplinary designs, often using project-based collaborative learning methods to measure students’ learning outcomes across emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and moral dimensions (Ng et al., 2023a; Ng et al., 2023b). Olari et al. (2022) analyzed 31 cases of AI literacy in schools, categorizing AI teaching practices into competence areas, pedagogical approaches, and contexts and formats. AI literacy education significantly enhances children’s understanding of AI, machine learning, computer science, and robotics, as well as other skills like creativity, emotional control, collaborative inquiry, literacy, and computational thinking (Su & Yang, 2022).

Numerous literature reviews have explored AI literacy education across various educational levels, from early childhood to adult learning. These reviews highlight aspects such as curriculum design, teaching methods, and research findings, suggesting that AI literacy education enhances understanding of AI and skills like creativity and computational thinking. While existing reviews have provided valuable insights into AI literacy education, the increasing amount of scholarly work highlights the need for mapping the current state of the field of AI literacy education. Comprehensive reviews using bibliometric analysis are needed to identify key and emerging research themes and patterns in AI literacy. Bibliometric analysis systematically and quantitatively assesses the literature, uncovering emerging topics and research gaps, and guiding future studies and policy-making (Donthu et al., 2021; Trinidad et al., 2021). Bibliometric analysis complements traditional reviews, offering a robust framework to understand the evolution and current state of AI literacy research, and informing educational practices and policies.

The present study

This study aimed to use bibliometric analysis to examine a collection of studies on AI literacy education, identifying prevailing research trends and themes in the domain while also projecting potential avenues for future research. A thorough review of 335 articles on AI literacy education published between 2014 and 2024 was conducted, sourced from the Web of Science Core Collection, Scopus, and Science Direct databases. The study addressed the following research questions:

-

(1)

What is the overarching pattern in AI literacy education research over the specified timeframe? (RQ1)

-

(2)

What are the research development paths of AI literacy education research in the past decade? (RQ2)

-

(3)

What are the most discussed topics of AI literacy education research, and how have they progressed throughout the years? (RQ3)

Methods

Overview of research method

This study used a bibliometric analytical approach to identify trends in the research on AI literacy education. A research trend signifies a collective focus within the research community, directing significant attention toward a specific scientific topic (Mazov et al., 2020). This phenomenon commonly arises when the scholarly community’s interests align with ongoing scientific developments. Bibliometric analysis employs mathematical and statistical techniques to quantitatively examine the bibliographic attributes within a body of literature (Hawkins, 2001; Pritchard, 1969). It is recognized as a robust method for unveiling patterns and trends within the accumulated knowledge in a specific research domain (Donthu et al., 2021; Trinidad et al., 2021). Specifically, bibliometric analysis visualizes various research characteristics and trends, including subject domains, keywords, thematic focuses, and contributors across geographic dimensions such as countries, regions, institutions, and authors (Aktoprak & Hursen, 2022; Zou et al., 2022).

Bibliometric analysis has been widely applied in various fields, including business research (Donthu et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2021) and education (Rashid et al., 2021; Rojas-Sánchez et al., 2023). For our analysis, we used CiteSpace, one of the frequently utilized tools for bibliometric analysis (e.g., VOSviewer, Gephi, Leximancer). CiteSpace stands out as a robust and widely embraced tool (Rawat & Sood, 2021). Developed by Chen (2004), CiteSpace is a potent instrument for visualizing and dissecting trends and patterns within a knowledge domain. Its capabilities include identifying research frontiers, tracing knowledge advancement, and unraveling the development of collaboration and citation networks (Chen, 2004). CiteSpace has been used in several review studies (Chen et al., 2023; Chu et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2022; Rashid et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2024; Yin et al., 2023).

Data selection process

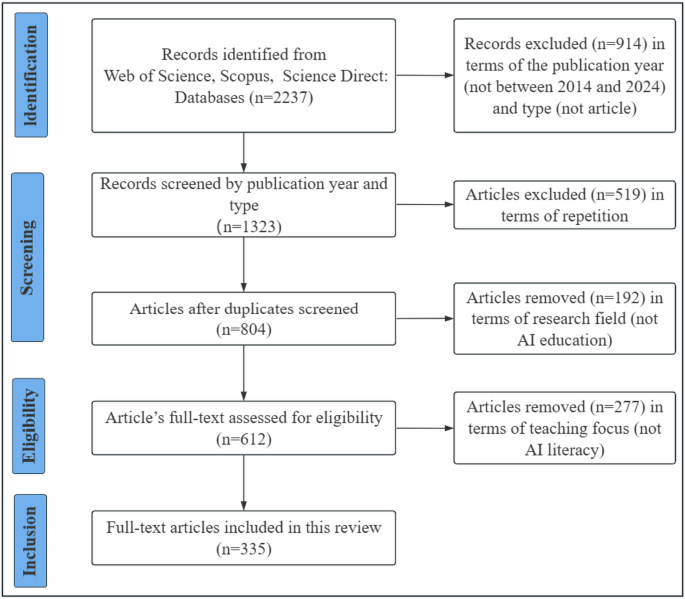

This study utilized the Web of Science Core Collection, Scopus, and Science Direct databases as data sources. The identification of studies for subsequent bibliometric analysis followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines, using the flowchart developed by Page et al. (2021), as shown in Fig. 1. Key steps in this process included such as establishing clear criteria for study inclusion and exclusion, systematically searching the literature based on these criteria, conducting an initial screening of retrieved records by titles and abstracts, reviewing the full text of selected studies post-initial screening, and further screening them based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data were then analyzed and synthesized to identify significant themes and patterns to address the research questions.

The procedure of selecting studies for the review.

In searching articles in the three databases, different search formulas were used. In the Web of Science Core Collection database, Query 1 was employed: (((AB = AI) OR (AB= “artificial intelligence”) OR (AB = ML) OR (AB= “machine learning”) OR (AB= “data science”) OR (AB= “robotics “)) AND (AB= literacy)). Similarly, the Scopus database was searched using Query 2: (ABS (AI OR “artificial intelligence” OR ml OR “machine learning” OR “data science” OR “robotics”) AND ABS (literacy)). Lastly, the Science Direct database was searched using Query 3: ((AI OR “artificial intelligence” OR ml OR “machine learning” OR “data science” OR “robotics”) AND (literacy)).

A total of 2237 records were retrieved from the three databases. Before starting screening, the criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies were clearly defined. These criteria should be used for literature identification, preliminary screening (based on article type and publication time), and full-text screening to assess eligibility. The inclusion criteria were: (1) empirical articles (excluding review articles, proceeding papers, and editorial materials); (2) articles published between 2014 and 2024; (3) articles in the field of AI literacy in education (non-medical, financial, etc.); and (4) articles focusing on the cultivation of AI literacy among learners.

In the screening phase, the publication year and type of articles in each of the three databases were defined, resulting in 1,323 articles. After removing duplicates, 804 unique records remained. Then, the abstracts and titles of these articles were reviewed, excluding 192 that were unrelated to AI education. Finally, the full texts of the remaining 612 articles were read, excluding 277 that were not focused on AI literacy, resulting in 335 valid documents.

Data analysis

The study primarily used CiteSpace 6.2.R2 (advanced) to analyze 335 identified studies. CiteSpace is a key tool in bibliometric analysis, particularly for visualizing data through co-occurrence knowledge mapping, which illustrates the relationships between different knowledge areas, documents, or authors (Chen, 2004). To analyze the studies, we first manually inputted data from annual publications and citations in the three databases into Excel, and then created a graphical trend chart to display the distribution of annual publications and citations. Next, we used CiteSpace’s diverse data representation modes to visually portray the trends and interconnectedness in the data.

Overarching pattern in AI literacy education research

To investigate the overarching pattern in AI literacy education research over the specified timeframe (RQ1), we conducted a citation analysis on 335 identified articles. We exported the number of publications for each year and created annual line graphs using Excel, including data labels. This approach allowed us to observe the overall development pattern of AI literacy research from 2014 to 2023, helping to identify periods of increased attention and emerging research hotspots.

Next, we used Excel’s trendline feature to perform exponential function fitting on the annual publication volume trendline. We presented the resulting fitted exponential function formulas and R² values, which indicated the degree of fit between the trendline and the exponential function. This provided additional insights into the developmental trajectory of AI literacy research.

Development paths of AI literacy education research

To explore the research development paths of AI literacy education research over the past decade (RQ2), we used keyword-based co-occurrence knowledge mapping. This method helped depict the developmental trajectories within AI literacy research. Keywords serve as concise summaries of an article’s core essence, and their frequency often correlates with their popularity. Thus, analyzing high-frequency keywords can quickly reveal predominant research themes and focal points (Pei et al., 2021).

CiteSpace constructs a co-occurrence matrix by counting keyword frequencies and recording their co-occurrence occurrences, then builds a network based on this matrix. In this network, keywords are nodes, and connections are formed between nodes whose co-occurrence frequency exceeds a set threshold (Chen, 2006). The network diagram uses line thickness to represent co-occurrence frequency, signifying the strength of the relationship between keywords. Thicker lines correspond to higher co-occurrence rates, indicating a stronger association.

We identified four development paths based on the centrality and closeness of keywords. We exported the article details (including title, author, keyword, and abstract) for each keyword node to an Excel table (please see it in the supplementary file) and summarized the development paths accordingly. In this study, the software settings defined “Node Types” as keywords, with a “Top N” setting of 50. The pruning strategy employed “Pruning Slice Network” and “minimum spanning tree” to produce the co-occurrence map of keywords.

Prevailing research themes and their progression of AI literacy education research

To examine the most discussed topics of AI literacy education research, and how they progressed throughout the years (RQ3), our analysis involved a two-step process. We first used the clustering function of CiteSpace V to discern prevailing themes in AI literacy education research. This technique effectively categorized frequently occurring keywords, facilitating their arrangement into distinct themes. Subsequently, visual representations in the form of clustered maps were generated for easy interpretation. To precisely capture the thematic essence of each cluster, we initiated the process by importing both titles and abstracts of all articles associated with the keywords within each cluster into an Excel database (please see it in the supplementary file). Next, we condensed the information contained in each article, amalgamating and refining these condensed versions. This approach ensured the formation of comprehensive summaries that encapsulate the core ideas of the individual articles. Furthermore, to construct a broader framework, our aim is to create a module that encapsulates the overarching sub-themes within each cluster. This strategic approach enabled a more lucid dissection of the distinct contents harbored within each grouping.

Next, we used the Timeline View function within CiteSpace to trace the evolution of AI literacy education research across specific themes. This approach provided valuable insights into the developmental trajectory (Rosvall & Bergstrom, 2010; Song & Wang, 2020), illuminating how the research has evolved over time. This examination of a research domain’s evolutionary path not only enhances comprehension of its context but also aids in predicting future research trends.

Results

The overarching pattern in AI literacy education research between 2014 to 2023 (RQ1)

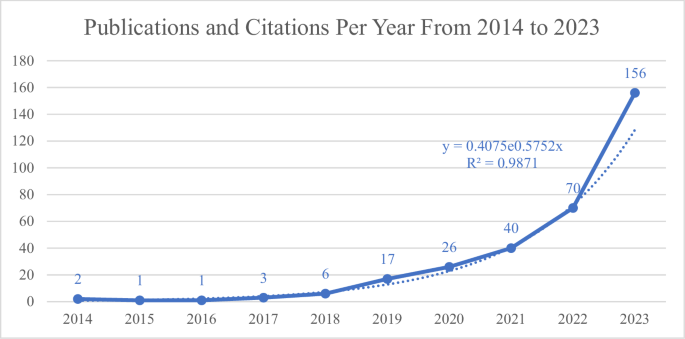

Figure 2 illustrates the temporal distribution of AI literacy education publications over time during the period 2014–2023 (Because there are so few articles published in 2024, they are not shown in the chart). As can be seen from the figure, the research literature on AI literacy education in the past ten years can be divided into two stages: the initial exploration stage and the rapid development stage. Specifically, the period from 2014 to 2017 was the initial exploration stage. During this stage, a total of 7 articles were published, and the average number of articles published per year was about 2 articles. Research had entered a stage of rapid development from 2018 to 2023. The total number of articles published in this stage reached 315, and the average number of articles published per year was about 53, which exceeds 94% of the total number of sample documents. Notably, the number of publications in 2023 alone reached 156, accounting for 46% of the total sample, indicating a significant surge in scholarly interest in this field.

The temporal distribution of publications and citations of the research on AI literacy from 2014 to 2023.

In Fig. 2, exponential function fitting (y = ex) was applied to the number of articles published from 2014 to 2023, revealing an R² value of 0.9871. This high R² value indicated that the growth in AI literacy education research closely followed an exponential trend. The exponential increase in the number of publications suggested that AI literacy education was becoming increasingly impactful in academic fields, and this growth trend was expected to continue in the future, highlighting the field’s enduring and expanding influence.

Developmental paths in AI literacy education research (RQ2)

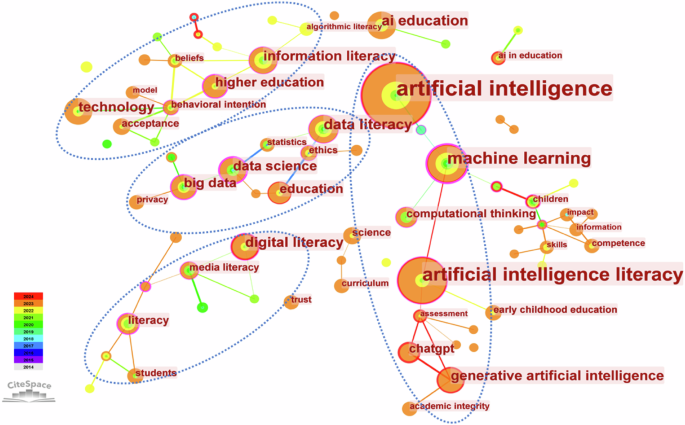

Figure 3 presents the co-occurrence diagram of keyword-based AI literacy education research from 2014 to 2024. In Fig. 3, each circular node represents a different keyword, with the size of the node proportional to the frequency of its occurrence. Larger nodes indicate higher frequencies, thus highlighting key research hotspots within the field. The thickness of the lines connecting nodes reflects the strength of the relationship between keywords; thicker lines signify more frequent co-occurrence in the literature.

Keyword-based co-occurrence knowledge map of AI literacy research from 2014 to 2024.

The diagram clearly shows that “artificial intelligence” (AI) was the most prominent keyword, underscoring the substantial focus of research on this topic. Following closely was “artificial intelligence literacy,” “machine learning,” “data literacy,” and “AI education,” which have emerged as significant research areas. Notably, these keywords collectively represent the primary academic hotspots within AI literacy research. A temporal analysis of high-frequency keywords revealed emerging concepts such as “ChatGPT,” “generative artificial intelligence,” and “digital literacy,” which have gained prominence in recent years. This trend indicated their growing significance in contemporary AI literacy education research.

Figure 3 also revealed four different research paths in A I literacy education research. The first path was artificial intelligence—machine learning—computational thinking—artificial intelligence literacy—assessment—ChatGPT—generative artificial intelligence—academic integrity. This research path mainly focused on the integration and impact of AI in various fields, especially in the field of education. In particular, students’ attitudes toward the application of generative AI in education have been favored by many scholars in recent years, as evidenced in studies such as Cardon et al. (2023), Chai et al. (2021), and Relmasira et al. (2023). In addition, curriculum development for developing AI literacy was also a focus of research as studied by Kong et al. (2022) and Kong et al. (2023b).

The second research path was the algorithmic literacy—information literacy—higher education—behavioral intention—technology—acceptance. This path mainly focused on algorithmic literacy, including the definition and importance of structural algorithmic literacy, as studied by Shin (2022) and Shin et al. (2022). In particular, Ridley, Pawlick-Potts (2021) found that algorithmic literacy can help users navigate the impacts of AI and exploit it responsibly. Additionally, this path focused on the measurement of AI literacy and its importance to students’ higher-order thinking and information literacy development, as revealed by Smith & Matteson (2018) and Wang et al. (2023a, 2023b).

The third research path was data literacy-ethics-education-data science-statistics-big data-privacy. This path investigated the interplay between data literacy, ethics, education, data science, statistics, big data, and privacy. It underscored the growing importance of data literacy and the integration of AI and data science across various educational and professional fields. Gray et al. (2018) and Markham (2020) emphasized the urgent need to enhance public data literacy to enable critical analysis of social life and well-being in an era of rapid data growth and evolving infrastructure. The rise of a data-driven culture had particularly highlighted the need to improve data literacy among primary and secondary school students and their teachers, as explored by Gould (2021), and Loftus and Madden (2020).

The fourth research path was digital literacy—media literacy—literacy—students. This path examined the effectiveness of digital literacy and media literacy on the development of AI technologies in the Internet era and the mechanisms through which AI technologies developed, as studied by Hwang et al. (2023), and Kozyreva et al. (2020). This path also emphasized the importance of cultivating AI literacy which played a key role in the innovation work and improving core competencies in the AI era (Santoso et al., 2019).

Furthermore, Table 1 presents the high-frequency keywords (occurring more than 10 times) from Fig. 3, emphasizing the significant variations in keyword frequency. Notably, many of these high-frequency keywords had emerged in the past five years, underscoring the rapid and steady development of the AI literacy education field in a relatively short period. This surge highlighted the growing importance and interest in AI literacy education research.

The most discussed topics of AI literacy education research and their progression (RQ3)

Research themes in AI literacy education research between 2014 and 2024

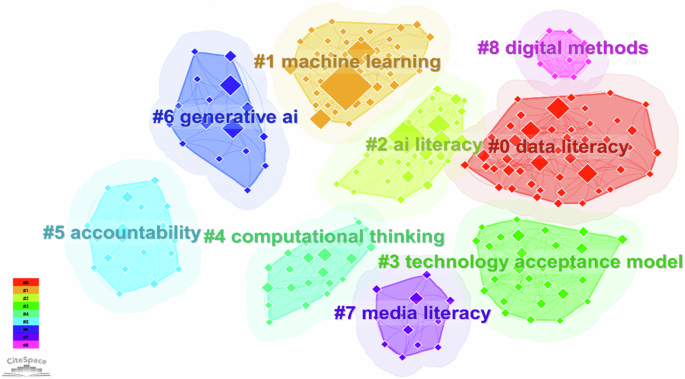

Figure 4 illustrates the co-occurrence map of themes in AI literacy research from 2014 to 2024. Table 2 provides an overview of the main themes and keywords identified during this period. The keyword clustering graph includes 283 nodes (N = 283) and 832 connections (E = 832). CiteSpace offers two metrics for evaluating clustering quality: the modularity Q-value and the silhouette S-value. The modularity index (Q = 0.6506) exceeds the threshold of 0.3, and the silhouette index (S = 0.8592) surpasses 0.7, indicating a stable and cohesive cluster structure. Figure 4 shows nice distinct research themes.

Theme-based co-occurrence knowledge map of AI Literacy research from 2014 to 2024.

Cluster #0 (data literacy)

This was the largest cluster, encompassing 47 keywords with a silhouette value of 0.781. It centered on the interplay between big data and AI, emphasizing the role of AI in enhancing data literacy within education. This cluster highlighted AI’s potential to improve data literacy among teachers and students, advocating for effective strategies to advance data literacy, as studied by Emery et al. (2021), Li et al. (2022), Li et al. (2023), Loftus and Madden (2020), McCosker (2022), and Williams et al. (2023). Key recurring terms included data literacy, data science, big data, education, and science.

Cluster #1 (machine learning)

Comprising 45 keywords and a silhouette value of 0.889, this cluster focused on the integration and application of machine learning in various educational disciplines, including medicine and languages (Arastoopour Irgens et al., 2023; Hockly, 2023; Rad et al., 2023; Teng et al., 2022). It also addressed the importance of AI literacy for the sustainable development of teaching professions (Chai et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2022). Recurrent keywords were AI, machine learning, technology, and students.

Cluster #2 (AI literacy)

This cluster, with 32 keywords and a silhouette value of 0.807, focused on the role of generative AI in education and the framework for developing AI literacy, such as studies done by Allen and Kendeou (2023), Pretorius, (2023), and Relmasira et al. (2023). It covered AI literacy across various educational levels, including K-12 and higher education, such as studies done by Lin et al. (2023), and Ng et al. (2023c). Common keywords were AI intelligence, AI education, higher education, literacy, early childhood education.

Cluster #3 (technology acceptance model)

Containing 28 keywords with a silhouette value of 0.858, this cluster examined students’ behavioral intentions towards AI learning and development. It explored dimensions such as AI knowledge, autonomy, self-efficacy, and learning resources, referring studies by Chai et al. (2021), Chai et al. (2022), and Chen et al. (2022). Key terms were acceptance, behavioral intention, knowledge, and trust.

Cluster #4 (computational thinking)

Featuring 23 keywords and a silhouette value of 0.835, this cluster highlighted the relationship between computational thinking and AI literacy. It discussed the impact of ICT access on AI use and provided an analysis of computational thinking’s key dimensions, such as studies done by Celik, 2023, Li et al. (2021), and Tykhonova and Koshkina (2021). Recurring keywords included computational thinking, competence, information, impact, skills.

Cluster #5 (accountability)

This cluster, with 19 keywords and a silhouette value of 0.987, explored the interaction between information literacy and data literacy in the digital age. It focused on information awareness, ethics, technology, and capabilities of college educators and students (Lund et al., 2023; de Vega-Martín et al., 2022; Li, 2022). Key terms were information literacy, algorithmic literacy, and data science applications in education.

Cluster #6 (generative AI)

Comprising 16 keywords and a silhouette value of 0.892, this cluster primarily examined the impact and challenges posed by the emergence of generative AI in various fields such as education, psychology, and scientific research (Dai et al., 2023; Rasul et al., 2023; Spallek et al., 2023). Within education, it specifically examined the influence of generative AI on teaching different subjects, including mathematics, English, and writing, and how to use AI, evidenced by studies such as Alexander et al. (2023), Dianova and Schultz (2023), and Kim (2023). Additionally, this cluster addresses students’ attitudes towards generative AI and their willingness to use it, refereeing studies by Chan and Lee (2023), and Firat (2023). Common keywords associated with this cluster included digital literacy, generative AI, ChatGPT, and academic integrity.

Cluster #7 (media literacy)

This cluster, with 12 keywords and a silhouette value of 0.885, focuses on the key dimensions of media literacy in the age of artificial intelligence, as well as the role of AI in various stages of information retrieval and creation (Lin, 2021; Tiernan et al., 2023). Recurring keywords in this cluster included media literacy, fake news, digital competencies, media education, and social media.

Cluster #8 (digital methods)

Featuring 10 keywords and a silhouette value of 0.991, this cluster considers data literacy initiatives and their impact on data science, data politics, and public engagement with digital data infrastructures (Gray et al., 2018). Recurring keywords included critique, digital methods, and data activism.

Overall, these clusters illustrated the diverse and evolving nature of AI literacy education research, with emerging themes reflecting advancements in AI technology and its integration into various educational and professional contexts.

Progression of research themes in AI literacy education between 2014 and 2024

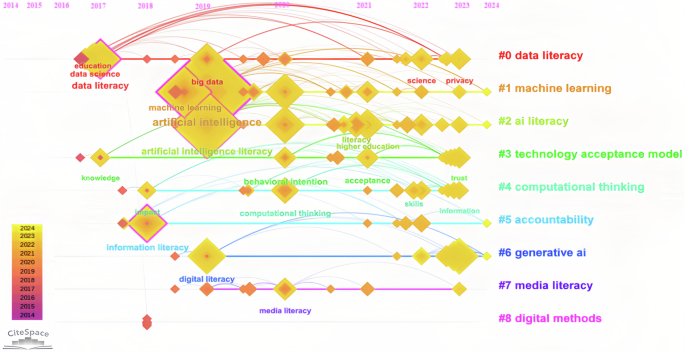

Figure 5 illustrates the progression and visualization of research themes identified in Fig. 4. The number of plot axes in Fig. 5 corresponds to the number of clusters, with each cluster encompassing closely related keywords. By examining the evolutionary trajectory of specific research fields, we gained a clearer understanding of the development and progression of AI literacy education research. This analysis also aided in forecasting future research trends in the field.

Theme-based progression analysis and visualization of AI literacy research from 2014–2024.

From Fig. 5, it was evident that Clusters #0 and #3 were the earliest and longest-lasting clusters. Subsequently, Clusters #4, #5, and #8 emerged in succession, followed by the more recent appearance of Clusters #1, #2, #6, and #7. Notably, the duration of Clusters #1, #2, #5, and #6 extended into 2024, suggesting that these clusters would continue to evolve and maintain their prominence as key research areas.

The term “AI literacy” first appeared in Cluster #2 in 2019. Prior to this, the focus was on related concepts such as data literacy in Cluster #0 and information literacy in Cluster #5. This shift indicated that while AI literacy has gained attention, scholars initially concentrated on data and information literacy. Loftus and Madden (2020) argued that to become proficient professionals in the IoT field and develop future systems, students must cultivate critical digital and data literacy. Lund et al. (2023) offered a comprehensive analysis of the interplay between information literacy, data literacy, and privacy literacy in the digital age. The rise of machine learning had heightened the demands for information literacy among educators, students, and professionals (Li, 2022; Smith & Matteson, 2018). To effectively engage with AI technologies, such as ChatGPT, and address associated ethical issues, individuals needed a broad range of AI-related knowledge and skills (Celik, 2023). The knowledge and skills encompassed by AI literacy overlap significantly with those of data and information literacy (Gould, 2021; Wang et al., 2023a), highlighting that AI literacy builds upon these foundational literacies.

Discussion and implications

As the integration of AI across various fields accelerates, fostering AI literacy among learners has become increasingly crucial. Despite its rising significance, there is a notable absence of comprehensive assessments that provide a clear overview of the current state of AI literacy education research. The concurrent review aimed to address this gap by elucidating the current status, tracking evolutionary trajectories, and identifying recurring themes and focal points through a bibliometric analysis of AI literacy education research from 2014 to 2024. We begin by summarizing key findings, followed by a discussion of their implications and the limitations of this study.

Summary of the key results

Overarching pattern in AI literacy education research

An analysis of annual publication volume statistics revealed a clear trajectory in the evolution of AI literacy education research. The period from 2014 to 2017 represented a phase of initial exploration, while from 2018 to 2023, the field experienced rapid expansion. During this latter period, AI literacy education emerged as a prominent research focus, evidenced by an exponential increase in scholarly publications. This upward trajectory was expected to continue, maintaining its appeal to scholars and researchers. These observations were consistent with previous studies highlighting a growing scholarly interest in the topics of AI literacy and its’ cultivation across various domains (Casal-Otero et al., 2023).

Developmental paths of AI literacy education research

An analysis of the developmental paths in AI literacy education research from 2014 to 2024 revealed its multifaceted nature. Four distinct pathways had emerged, underscoring the interdisciplinary character of the field and reflecting broader trends in education and technology research. These pathways highlighted the intersections between education, technology, and other domains, illustrating an increased awareness of AI’s extensive impact. Additionally, the analysis revealed the strong interconnection between AI literacy and related fields such as information literacy, digital literacy, and algorithm literacy. These results were in line with prior research highlighting AI’s integration into education and diverse sectors, endorsing interdisciplinary collaboration and emphasizing its dynamic evolution across disciplines (Zhai et al., 2021).

Prevailing research themes and their progression in AI literacy education research

Keyword-based co-occurrence mapping provides valuable insights into prevailing themes and emerging trends in AI literacy research. Key research areas included data literacy, machine learning, AI literacy, the technology acceptance model, and computational thinking. The extensive use of machine learning algorithms and the increasing emphasis on interdisciplinary data literacy reflected the expanding role of AI in various fields, particularly in education. The evolution of keywords within clusters indicated shifts in research focus, demonstrating a clear correlation between AI literacy, data literacy, and information literacy. Additionally, the temporal progression of these clusters explains the sustained relevance of machine learning, AI literacy, accountability, and generative AI as central research themes. Empirical research highlights that incorporating ethics into AI education not only deepens students’ comprehension of AI concepts but also cultivates ethical awareness. The effectiveness of this integration is supported by studies such as Lin et al. (2021) and by models proposed by Zhang et al. (2022) and Williams et al. (2023). Consequently, future research should prioritize the ethical aspects of AI literacy education, with a focus on embedding AI ethics and critical thinking exercises within educational frameworks to enhance AI literacy.

Implications of the results for educational practices, research, and policymakers

The study’s findings have several implications for educational practices, research, and policymakers that focus on fostering learners’ AI literacy. Regarding implications for educational practices for developing learners’ AI literacy, first, educators should work together to create an integrated curriculum that incorporates AI-related content, skills, ethical dimensions, and societal implications into educational curricula across various levels, and to design corresponding integrated learning experiences that introduce students to AI concepts, their applications, ethical considerations and societal implications. In this way, we can cultivate a solid foundation of AI literacy for the learners and thus empower them to navigate the AI-driven landscape effectively. Second, educational practices should provide students opportunities to work as active agents, such as involvement in AI-driven simulations, project-based assignments, and coding exercises, and help them engage in hands-on activities and real-world applications that enhance learners’ ability to apply AI concepts in their lives and future careers. Third, educators should create opportunities that incorporate digital literacy skills and ethical AI use in their daily learning and thus help students develop responsible and informed AI users.

There are three implications for research in AI literacy education. First, AI literacy research spans various age groups, ranging from early childhood education to K-12 education and higher education. Notably, early childhood education and higher education have emerged as pivotal focal points within this field. Moving forward, an increasing imperative lies in directing more attention towards augmenting the AI literacy of adults, especially those closely engaged with AI technology, such as professionals in specialized sectors. Second, the domains of education and media have garnered substantial attention from scholars in the context of AI literacy. As the path of AI technology unfolds, there is a hopeful anticipation that professionals across diverse fields will recognize the pivotal importance of AI literacy, and researchers from varied disciplines should be more actively involved. Third, researchers from diverse fields should work together to address challenges in AI literacy research, such as the assessment of and promotion of AI literacy among students of varying ages.

Three are three implications for policymakers for enhancing learners’ AI literacy. First, it is necessary for policymakers to integrate AI literacy into curricular standards. They should work together with subject matter experts and educators to define age-appropriate AI literacy competencies and integrate them into the curriculum. Second, it is crucial for policymakers to develop opportunities to facilitate international collaboration and enhance AI literacy initiatives across diverse contexts to promote learners’ AI literacy.

Research limitations and future directions

This study has several limitations. First, it utilized the CiteSpace tool for a detailed visual analysis of the evolving research landscape and trends in AI literacy education. It is important to note that the cooperative networks and clusters generated by CiteSpace are influenced by parameters such as the number of slices, Top N keywords, and clustering functions. Consequently, while the study provides valuable insights, its conclusions are subject to limitations inherent in the chosen parameter settings. Future research should address this by performing sensitivity analyses with various parameter configurations to identify stable and consistent themes in AI literacy research.

Second, this study relies on data from Web of Science, Scopus, and ScienceDirect databases as primary sources of literature. Although these databases encompass a significant portion of AI literacy research, some relevant articles may be excluded. Thus, while the findings offer a preliminary overview of the research landscape, they may not fully capture the entire field. Future studies should incorporate additional academic databases and diverse platforms to ensure a more comprehensive representation of AI literacy research.

Third, this study primarily used bibliometric analysis to shed light on the current landscape of AI literacy education research, trace its evolution over time, uncover key themes, and identify important research priorities. This method provides a robust framework for understanding the evolution and current landscape of AI literacy education research, thereby informing educational practices and policies. However, bibliometric analysis is inherently quantitative, resulting in predominantly quantitative findings. In this study, we supplemented our approach with qualitative analysis to offer more meaningful interpretations of the results presented in the figures. Nonetheless, the depth of our qualitative analysis was not as extensive as that typically found in traditional reviews focused on qualitative methods. Therefore, future review studies should consider focusing on in-depth qualitative analyses of AI literacy education research and integrating both bibliometric analysis and comprehensive qualitative analysis.

Responses