Navigating trade-offs on conservation: the use of participatory mapping in maritime spatial planning

Introduction

Over the years, the debate on maritime spatial planning (MSP) and its characteristics has broadened to include other authoritative, participatory, ecosystem-based, integrated, future-oriented, and adaptive features of MSP1. UNESCO defines MSP as: “the public process of analysing and allocating the spatial and temporal distribution of human activities to achieve ecological, economic, and social objectives usually specified through a political process”2.

MSP constitutes a shift away from conventional single-sector planning, aiming for a more holistic strategy in sea planning3. As such, a fundamental aspect of MSP is its functionality, which involves incorporating diverse sectors, societal requirements, values, and objectives into the planning process4.

Thus, MSP needs to find a balance between increasing maritime use and the sustainable development of these activities within the natural limits of the ecosystem. This is an ecosystem-based approach (EBA)5. EBA is intended to balance the multiple interrelated dimensions of ecological integrity and human well-being6. In this approach, the concept of ecosystem services (ES) is therefore important to operationalise EBA.ES can be defined as the benefits which nature provides to people, or the direct and indirect contributions from ecosystems to human well-being7. ES can be divided into provisioning services (such as food and fresh water), regulation and maintenance services support (such as climate regulation and water regulation), supporting services (such as nutrient cycling and primary production), and cultural services (such as recreation and tourism)7,8,9; these services are not independent of one other and have often complex interactions10.

Also, “win-win solutions” in spatial planning are as rare as they are in the real world, so trade-offs and choices must be made11. A trade-off in the context of MSP refers to the compromise or exchange between different objectives, interests, or uses of marine resources and space12. The decision-making process must weigh the potential benefits and costs of various uses or management options, considering ecological, social, and economic factors. Trade-offs in MSP require careful consideration and balancing of these different factors and interests12. It should be noted that “trade-offs can occur spatially or temporally and may or may not be reversible”13. White et al.10 highlight that “making trade-offs explicit improves transparency in decision-making, helps avoid unnecessary conflicts attributable to perceived but weak trade-offs, and focuses debate on finding the most efficient solutions to mitigate real trade-offs and maximise sector values”.

Therefore, a relationship exists between trade-offs and the concept of ES in MSP and environmental management in general10. This relationship between ES and trade-offs is important to understand how to minimise inequalities and inequities. Nevertheless, ES, and particularly the relations between ES, could be difficult to assess and constitutes a challenge for ecologists, decision-makers, planners, etc.14.

First, a clarification of the different concepts and reasoning of the methodology was grounded on an exploration of the scientific literature. The aim was also to understand the various trade-offs that can occur in MSP and, in parallel, develop a portfolio summarising the various arguments to be used in these trade-offs. This step proved to be important as the literature on trade-offs, in this context, is scarce and often not grounded in practice. In order to have as much coverage as possible of different perspectives, the literature review went beyond the maritime theme, and an extended search on the use of trade-offs in decision-making was performed. In that review, the analysis of common features, steps and concepts laid the ground for the first methodological approach to a much-needed organised method of practice.

Recognising that ES is vital for guiding sustainable resource management, preserving biodiversity and ensuring a sustainable future12,15, a literature review of mapping ES was also carried out. Assessing the impact of human activities on ecosystem ES involves quantifying the contributions of ecosystems to human welfare and mapping these services. Visual representation through mapping is crucial for analysing, interpreting, and communicating data related to supply, demand, trends, and connections with land use or threats16.

To achieve the goal of mapping the ES, two methods were identified and proposed to the stakeholders: criteria overlay and information “hotspots” (concentrated hub). The first overlays each criterion related to the ES. This method is based on multi-criteria analysis, a method to structure and formalise decision-making processes frequently employed to assess ES, as demonstrated in previous studies17,18,19. The second method is to explore the areas where most information (on the components of the ecosystem) is available to be aggregated and explore the areas with the most potential ES20,21.

Another subject needing further exploration is the arguments used in a trade-off process (in the negotiation conversations). A portfolio of arguments (Supplementary Material 01) containing an organised list of arguments was developed to support decisions during the negotiation of trade-offs. The portfolio of arguments explores trade-offs in marine spatial MSP, highlighting conflicts between various stakeholder interests. Key trade-offs include balancing marine conservation and economic development (e.g., fishing and tourism), ecological and cultural values (e.g., coastal infrastructure development versus heritage preservation), short-term and long-term benefits (e.g., immediate economic gains versus sustainable resource management), ecological integrity and human uses (e.g., establishing MPAs), and exclusive versus shared uses of marine space (e.g., balancing shipping needs with recreational activities), and local versus global interests (e.g., reconciling local economic needs with global climate change mitigation). The document details these conflicts through examples, management measures, and financing mechanisms for marine conservation, including government allocations, private sector contributions, and innovative funding approaches like user fees and conservation easements. Compensatory measures are also discussed, emphasising a hierarchy from addressing impacts at the same location to comparable ecological functions in different locations. Ultimately, effective MSP necessitates careful consideration of these complex trade-offs to achieve sustainable and equitable outcomes22 (Supplementary Material 01_ Portfolio of arguments to support).

These arguments for the purpose of this paper have been arranged in five types: trade-offs between marine conservation and economic development, where MSP must balance the need to protect marine ecosystems while supporting economic activities such as fishing, shipping, and tourism23; short-term and long-term benefits, in which MSP must balance the immediate benefits of certain activities with the long-term benefits of protecting marine ecosystems24; exclusive uses and shared uses, when decisions about the allocation of marine space may involve trade-offs between exclusive use for a specific activity or multiple shared uses in the same space or with the same resource25; local and global interests, wherein MSP can benefit local communities through economic development and job creation and must also consider the impact of human activities on the global ocean ecosystem26; and specific stakeholder interests, in which different stakeholders may have different priorities and objectives27. Although these typologies can be shaped with further discussion, this is not the aim of the present article, and they are accepted as valuable to inform validation in test sites.

An emerging concept is communities of practice (CoPs), where different stakeholders involved in MSP are grouped. CoPs are defined as “groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly”28. CoPs foster individual and group knowledge within a social learning system29. They promote knowledge sharing, improved decision-making, collaboration between stakeholders, adaptation to change and capacity building, thus contributing to more effective and sustainable MSP30,31.

The MSP4BIO project, financed by the European Union, aims to “develop an integrated and modular Ecological-Socio-Economic (ESE) management framework for protecting and restoring marine ecosystems, within its more general objectives of promoting sustainable blue growth and integrating maritime policies. The ESE looks at the compatibility between maritime/coastal uses and protection measures”22. MSP4BIO is being carried out in six test sites: Atlantic 1 (the Bay of Cádiz), Atlantic 2 (the Azores), the Baltic Sea, the Black Sea, the North Sea, and the North-West Mediterranean Sea (1). Hereafter, when case sites are referred to, this means MSP4BIO case sites.

The MSP4BIO CoP engaged key stakeholders from various sectors, including MSP planners, MPA managers, environmental NGOs, and representatives from key industries such as fisheries and energy. Established in the project’s fourth month, the CoP aimed to foster collaboration and ensure the effective implementation of methodologies developed by MSP4BIO. Each test site selected between five and eight main and alternative members based on their decision-making authority and relevant expertise. Interaction within the CoP was ongoing, focusing on identifying gaps and opportunities, facilitating feedback integration into decision-making processes, implementing trade-off exercises and enhancing the adaptability of the ESE framework to local contexts throughout the project lifecycle. This collaborative approach ensured that stakeholder insights contributed significantly to the project’s outcomes32. The objectives of this article are to: develop and test a module of an integrated socio-economic-ecological management framework; use the trade-offs scenario approach; take spatial and strategic protection and restoration measures into consideration; make it readily available for further use by planners and managers; and showcase that the method is test-proof through its application in a diversity of case sites. For the purpose of this paper, trade-offs are used, based on MPAs’ experience of the case sites on Project MSP4BIO. It is assumed that trade-offs in this context represent a valuable example of the integration of a given sector in MSP.

In this study, a mixed-methods approach is employed, combining quantitative data analysis with qualitative interviews to gain a comprehensive understanding of the subject. The quantitative data was collected through structured surveys, while the qualitative insights were gathered from in-depth interviews with key stakeholders within the scope of the case sites CoP.

Results

The methodology was applied at six test sites (Baltic Sea, Mediterranean, Atlantic (Azores), Atlantic (Bay of Cádiz), Black Sea and North Sea). It should be noted that each test site has tailored the methodology to fit their local context and objectives as advised.

Cádiz Bay had as a goal to address conflicts within the nominal MPA of the Bay of Cádiz. Despite strategic objectives, the MPA lacked effective implementation, leading to challenges in achieving consensus on solutions among stakeholders from various sectors. Trade-offs, such as that between marine conservation and economic development, highlighted the need for a robust governance framework. The workshop emphasised the importance of examining past initiatives, enhancing surveillance, and starting with more straightforward issues. SeaSketch, a participatory mapping tool, showed promise in the context of the growing blue economy but faced challenges in small MPAs. The overall experience underscored the vital role of effective governance and strategic planning for successful MSP in the region.

The Azores involved representatives from various sectors aiming to support the creation of a new protected area. Utilising the SeaSketch tool, participants identified conflicts, potential uses, and perceptions related to climate change. Trade-offs were discussed, including conflicts between marine conservation and economic development, highlighting the importance of integrating new members into the CoP and the need for more resources for effective participatory mapping in the growing blue economy.

The Belgian test site had two objectives: proposing a marine reserve in the Belgian part of the North Sea and addressing trade-offs and considerations for pelagic biodiversity protection. The workshop successfully facilitated trade-offs, ecological protection, and discussions on coastal management. Challenges included tool applicability and potential stakeholder fatigue. Challenges involved the dynamic nature of the maritime decision-making system, but the workshop provided valuable insights and highlighted the importance of addressing uncertainties in planning.

The Western Mediterranean test site concentrated on marine mammal conservation, aiming to extend the network of strictly protected areas (SPAs). The workshop used various environmental features and ecosystem service layers, identifying challenges related to large cetacean species, maritime traffic, and collision risks. Recommendations included relying on existing initiatives, developing criteria for SPA design, and recognising the complexity of marine mammal protection.

In the Black Sea test site, the CoP workshops explored conflicts and potential uses in the Bulgarian test site, focusing on extended MPAs and offshore wind farm development. Trade-offs involving marine conservation, economic development, and ecological integrity were discussed. Challenges included defining clear trade-off arguments, and recommendations emphasised the need for integrated MSP, improved planning measures, and transnational/cross-border MSP.

In the Baltic Sea test site, the CoP workshops focused on identifying and analysing conflict areas for expanding MPAs in Gdansk Bay, Poland. Participatory mapping highlighted conflict areas, with tourism expansion posing challenges. Insights underscored the importance of data availability, stakeholder knowledge, and leveraging existing research for informed decision-making. Challenges included the lack of data on the impact of tourism, suggesting a need for further research.

In the context of the case site results, the term ‘highlight’ indicates that the trade-off was a central topic in discussions among stakeholders

Involvement of the stakeholders

In the context of MSP, as defined by ref. 33, “stakeholders are individuals, groups, or organisations that are (or will be) affected, involved or interested (positively or negatively) by MSP measures or actions in various ways”. Stakeholder analysis is one of the essential components of effective MSP, facilitating sustained stakeholder engagement in a manner that promotes long-term exchanges34. These exchanges are central to clarifying the arguments that each stakeholder is willing to discuss and trade-off (trade-off arguments are analysed in detail in section Analysis of trade-off arguments below).

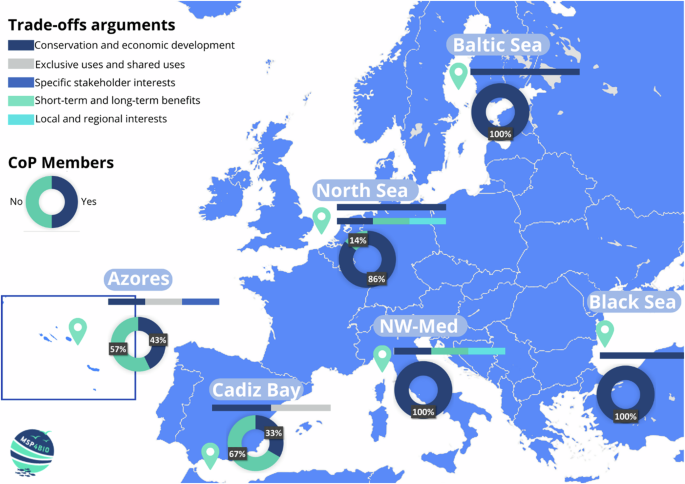

First, the individuals involved in the study were active members of established CoPs. However, certain case studies, as illustrated in 1, adopted a more inclusive strategy, as exemplified by Cádiz, which extended its participation to additional stakeholders interested in the region. This broader approach was driven by Cádiz’s goal of gathering fundamental information and establishing a framework. For the Azores and the North Sea test sites, new members were incorporated into the CoP. In the other case studies, CoP members were predominantly present at the meetings, with only a few notable absences.

This highlights the diversity of approaches taken by different case studies regarding stakeholder participation. The proposed methodology holds the potential to enhance stakeholder interest and participation, facilitating collaborative development of the ecological-socio-economic (ESE) framework.

Even if the process takes time and resources, the stakeholders’ participation is crucial as it encourages social acceptance, reduces conflicts and increases trust between the partners35. The decisions concerning the MSP also address one of the uncertainties in planning: ambiguity. Ambiguity is defined by multiple knowledge frames or different but (equally) sensible interpretations of the same phenomenon, problem, or situation36. Ambiguity is often led by vague legal/policy formulation37.

Furthermore, Pomeroy et al.34 highlight that “stakeholders must be defined broadly to capture a wide range of groups and individuals, it is important to note they are also often dangerously simplified, suggesting that interests, experiences, needs and expectations are homogenous among a given group of people”.

Nevertheless, some test sites highlighted the risk of stakeholder fatigue and work duplicated. Furthermore, some CoP members express the need for more time to prepare and discuss results, citing low digital skills and difficulties organising online or hybrid events. Indeed, as Zaucha et al.35 highlight, stakeholder participation has costs. For these authors, the main ones are the need for larger financial and human resource capacities, a longer preparation period for planning solutions, the risk of losing control over the MSP process by the authorities, and the risk of the process being dominated by the government or by private interests.

Ecosystem services map

While the methodology proved consistent and applicable, only the Baltic Sea test site chose ecosystem service mapping due to existing geo-referenced data. In the Western Mediterranean, criteria and indicators were employed for discussion. One reason for this choice was the time available. Since the assistance for ecosystem service mapping was not initially included in the project’s scope, support from the UAc team only became available in October.

Furthermore, the lack of training in various test sites also contributed to the non-utilisation of the ES map, as it requires advanced geomatic skills and spatial data manipulation. Additionally, inadequate data, including geo-referenced, high-resolution, quantitative, and bio-physical data, posed challenges for efficient ES mapping, especially in marine environments. The incomplete knowledge and uncertainties about planning stem from this data deficiency, as highlighted by Ounanian et al.36. Lastly, understanding the concept of ES is crucial, with Bitoun et al.38 emphasising that challenges arise from a lack of comprehension, particularly when adopting recent ES concepts.

This involves mapping the biophysical characteristics of ecosystems that contribute to the provision of ES. To create this type of ES mapping, all available information on the components of the ecosystem is aggregated. This method will aggregate the binary assessment of the contribution of the ES for each ecosystem component. In this binary scale, 0 represents no or negligible contribution of the ecosystem component to the ES, while 1 corresponds to a situation where the ecosystem component contributes to the service in an important way. This method will, therefore, highlight the areas with the most potential ES 20,21.

This method has the advantage of being simple to use and requires limited human and time resources. However, the disadvantage is that it is not robust. Indeed, it only considers the presence or the absence of information about the ecosystem to produce the map. In addition, each component of the map is considered to be equal, which means that the accuracy of the information represented is reduced 20,21. Furthermore, this method will only represent biophysical aspects and will not represent the socio-economic criteria of ES.

Definition of goals

This Section serves to ensure that clear objectives are establish in all case sites or Trade offs Processes. The various testing locations share common goals, albeit with some variations. In terms of similarities, all sites have a common concern for conflict mapping, aiming to identify areas where human activities conflict with marine conservation objectives. Additionally, each site involves diverse stakeholders, ranging from regional governments and NGOs to industry representatives, fishermen, and tourism agents. This inclusive approach seeks to integrate a variety of perspectives into the decision-making process.

Overall, most sites have goals related to marine conservation, whether through the creation of new protected areas, extension of existing networks, or resolution of conflicts to ensure sustainable ecosystem management. As highlighted by Halpern et al.23, one of the main objectives of conservation is to identify optimal allocations of actions in space, but also in time. It is therefore logical that the main objectives are related to conservation and areas that minimise conflict between conservation and human activities.

However, notable differences exist among the testing sites. In Cádiz, the emphasis is on strategic goals, such as placing the MPA on the political agenda, while other sites focus more on operational goals, such as creating or extending protected areas.

In the Western Mediterranean region, there is a specific focus on the conservation of marine mammals and their interactions with maritime traffic. Indeed, as the aim of MSP is to deliver sustainable development in the marine environment, and as the impact of maritime traffic is an anthropogenic threat to the marine mammals in the Western Mediterranean region, MSP therefore allows human activities and protection of cetaceans to be linked 39,40.

The Azores give particular attention to perceptions of climate change, illustrating a specific concern for long-term environmental impacts. Understanding the perception of the stakeholders allows an understanding of political realities that may not be published in the academic literature. Furthermore, it will also help to provide best practice advice for decision-makers in future design, monitoring, and management 41,42.

The Black Sea (Bulgarian) site is distinguished by its examining of potential conflicts related to offshore wind farm development, highlighting specific considerations related to renewable energy. Indeed, renewable energies, as one of the fastest-growing new uses of the ocean, can be used as a catalyst for the MSP process10.

Finally, the Belgian North Sea carried out two distinct trade-off analyses with distinct focuses, one emphasising the creation of marine reserves and the other prioritising pelagic biodiversity and marine habitat management.

In summary, while all testing locations share common concerns about marine conservation and conflict resolution, each project tailors its approach specifically to its region’s unique characteristics and challenges, reflecting a personalised and contextualised approach to sustainable marine management.

Data layers used

Each test site undertook the task of describing the used data layers for: (a) the actual area – an existing/established MPA or other area-based management protection measure, (b) the proposed area – an area with biodiversity needing protection, and (c) climate change – areas with environmental future characteristics similar to (a) and/or (b).

As highlighted by Ehler & Douvere (2009)33, gathering and organising spatially-specific databases typically constitute the most time-intensive phase of planning and management endeavours. Different types of sources for these data can be used: scientific literature, expert scientific opinion, government sources, local knowledge and direct field measurement33.

Two distinct approaches were observed for the actual area layers. Cádiz Bay and the Azores employed a participatory method, with sectors or users identifying crucial areas. This approach using local knowledge can promote adaptability in decision-making, support environmental justice, reduce governance rigidity, and improve acceptance and uptake43. In contrast, other sites, including the North Sea, utilised existing environmental/ecosystem layers and marine space usage.

Examining conflict areas in the proposed zones involved stakeholders’ input, with West-Med employing specific criteria through Important Marine Mammal Areas (IMMAs) data analysis. The participatory mapping of conflict clarifies the conflict condition, generates spatial data, and produces solutions to facilitate consensus-building44.

Climate change will provoke changes in ocean conditions, while the structure and functioning of marine ecosystems will lead to changes in the distribution and intensity of ocean-related human uses45. Indeed, ocean ecosystems are particularly vulnerable to climate change46. Therefore, integrating climate change is necessary to “contribute to ocean sustainability, anticipating future changes in marine social-ecological systems, ameliorating negative consequences for societies, lessening anthropogenic impacts on ecosystems, and promoting the equitable flow of benefits”47.

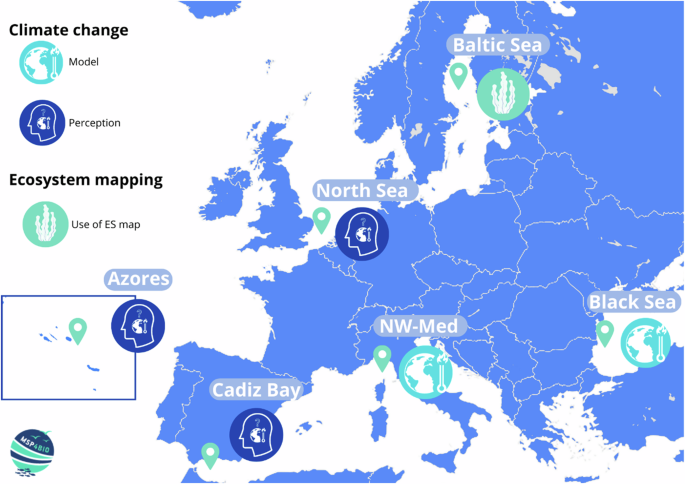

The different test sites, therefore, add climate change in their participatory survey. Two methods could be distinguished: the use of climate models, used by NW Med, Black Sea and the use of perception, used by Cádiz Bay, Azores, and the first survey of the North Sea, while the Baltic Sea did not include such layers (2). Cádiz Bay focused on identifying sensitive areas based on risks to population, infrastructure, sector activities, and environmental conservation. Azores assessed climate change through questions on likelihood, impact, and effects on ES. The North Sea spatialised the impact of climate change.

Choosing the climate change modelling approach allows the estimation of alterations in marine ecosystems and human uses resulting from climate change and is helpful for MSP design45. Nevertheless, one challenge of this method is the lack of consistent databases, climate change models, and the corresponding validation of simulated results for all sectors studied41.

Addressing the perception of climate change is important as the perceptions of the impacts depend on the socio-economic context. Furthermore, it allows an understanding of stakeholders’ feelings, their knowledge of the subject, and their knowledge of the local context that is not in the scientific literature 41,42.

Analysis of trade-off arguments

With finite marine and coastal resources, MSP faces the challenge of allocating space and usage efficiently among competing sectors such as shipping, fisheries, aquaculture, biodiversity conservation, and renewable energy. The trade-off analysis can therefore navigate conflicting objectives and strike a balance that optimises resource utilisation while minimising negative impacts12,38. As highlighted by Zuercher et al.48, “trade-offs are an inevitable, yet complex, reality of any multi-sector, multi-objective planning process”.

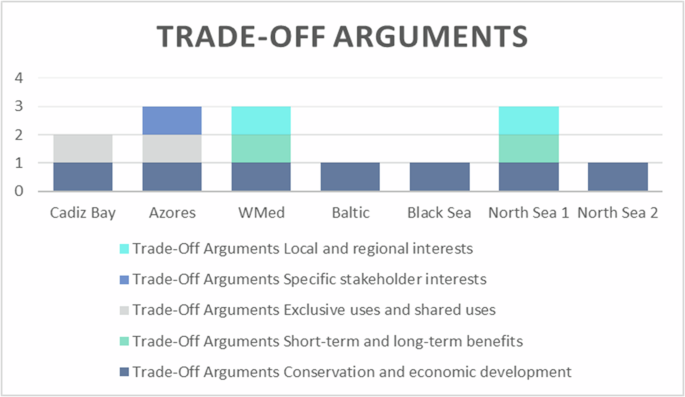

To complete the trade-off analysis, each test site had to describe the arguments used for the established trade-offs offered in the partners guidelines (Fig. 1)22. Trade-off analysis can help evaluate activities that share common resources, enabling the exploration of various configurations for the planning and distribution of marine activities49. This argument portfolio was used to provide the different arguments, as well as a common definition so that each test site would have the same frame of reference Fig. 2.

Use of trade-off arguments and constitution of the discussion group for each test site extracted from deliverable 4.3 MSP4BIO.

Climate change consideration (perceptions of models) and the use of ecosystem mapping for MSP4BIO test sites extracted from deliverable 4.3 MSP4BIO.

The management of the trade-offs begins when it is not possible to compromise with objectives from very different dimensions, such as economic, social, and environmental, etc. Trades-offs occur between these different dimensions, but also inside the dimensions themselves50. As highlighted by Lester et al.12, it “can reveal inferior management options, demonstrate the benefits of comprehensive planning for multiple, interacting services, and identify ‘compatible’ services that provide win-win management options”.

Figure 3 shows that every test site has one argument in common: conservation and economic development. This trade-off means finding the right balance between sustainable practices and allowing economic growth while minimising environmental harm. The fact that this trade-off is common in every test site is logical. Indeed, dealing between conservation and economic goals is one of the main objectives of MSP and conservation23.

Trade-offs arguments extracted from deliverable 4.3 MSP4BIO.

The West-Med and North Sea 1 highlighted two arguments: trade-offs between short-term and long-term benefits, and trade-offs between local and regional interests. Opting for short-term benefits can provide immediate gratification or economic advantages but may come at the expense of long-term consequences24. In the case of the West-Med, mitigation measures to minimise ships’ impact on mammals could consist of traffic deviation or speed limitation. These measures could have an important economic impact on the sector and there are few arguments to lower or compensate for it. A cetacean presence alert broadcast could be a way to lower the economic impact by enforcing mitigation measures only when it is needed.

Concerning the second argument, the two test sites agree with the fact that it may be more interesting to think on a larger, transnational scale to be efficient. Indeed, many issues and sea uses are not found only within national borders51.

About the trade-off between exclusive uses and shared uses, Cádiz Bay and the Azores highlighted this argument. The trade-off between exclusive uses and shared uses relates to the allocation of resources or spaces and the choice between restricting access to a select few or opening them up for the broader group. The challenge is to create policies that reconcile exclusive and shared use, serving the interests of diverse stakeholders.

Only the Azores choose specific stakeholders. Each stakeholder has specific interests and needs in marine spaces, and managing these competing interests requires careful consideration and trade-offs. Indeed, the interests of recreational boaters and tourists can come into conflict with conservation interests. This access can be managed by conditioning how it is done, making it less devastating for the marine ecosystem.

The Bay of Cádiz highlighted that the difficulty of this exercise also concerns illegal activities, because even if they are not authorised, they are accepted, and therefore do not give the impression that there are any conflicts. This proves, as highlighted by Turkelboom et al.11, that the analysis of trade-offs argument shifts from formal scientific data to informal and implicit knowledge possessed by the stakeholders.

Even if there are some trade-offs in common with each test site, this exercise highlights the difference in trade-offs analysed between the test sites. As highlighted by Lester et al.12, trade-offs are context-specific and depend on the particular circumstances of each MSP process.

Discussion

The recommendations (Table 1) were made based on the results received from the various test sites and by looking at them through the lens of the three-step method developed by De Magalhães et al.50: early decisions, acceptable and negotiable aspects, and decision-making process support. De Magalhães et al.50 separated these three principles as a guideline for trade-off management.

These recommendations not only serve as a guide for future MSP endeavours but also underscore the importance of continuous improvement, innovation, and adaptation in the dynamic field of MSP.

In conclusion, the participatory development of integrated trade-off scenarios, as outlined in the methodology, provides a valuable framework for maritime spatial planning (MSP) and MPA design. The application of this methodology across six test sites of the MSP4BIO project underscores the importance of stakeholder involvement and the adaptability of the approach to local contexts. The shared and unique goals across these sites emphasise the multifaceted nature of marine conservation efforts.

The analysis of challenges and successes in implementing the methodology, including the use of ecosystem service mapping, goal identification, and consideration of climate change, provides practical insights. The identification of commonalities and differences among the test sites highlights the flexibility of the methodology to address specific regional concerns.

Nevertheless, even if a method to map ES was proposed, no test sites decided to use it for different reasons (lack of training, data, time, etc.). However, the authors consider that highlighting ES by identifying and mapping them can support better management of human activities to minimise negative impacts on the ecosystems while maximising benefits for society. This aspect should be reflected in the future of an MSP/MPA integration.

The recommendations derived from the findings offer practical insights for future MSP initiatives. From early decisions to decision-making process support, the recommendations address key aspects such as stakeholder engagement, addressing illegal activities, and improving coherent policies.

In summary, the aim to contribute to advancing methodologies and practices in the MSP and MPA integration process is now a step further along, although not fully completed. The lessons learned and recommendations provided aim to guide future MSP endeavours, emphasising the importance of continuous improvement, innovation, and adaptation in the dynamic field of MSP for sustainable marine management and conservation.

Methodology

This methodology was initially developed by the authors as a guideline exercise and validated collaboratively (stakeholders involved in the CoP of the test sites and the entire group of experts composing the partnership of the project) in the third CoP interaction of the MSP4BIO Project22. The aim is to provide methodological guidelines for applying trade-off methodology for MPA design. More precisely, these guidelines will develop participatory-based trade-off scenarios to weigh the impacts of the multi-objective spatial and strategic management measures. The development of this methodology of participatory-based trade-off scenarios is described in the following process and adapted from Calado et al.52,53.

Guiding the application of trade-offs in test sites

The University of the Azores developed the guidelines for the trade-off exercise with the community of practice (CoP). These were subsequently applied and tested by MSP4BIO partners during their collaborative interactions22.

A guideline document for the MSP4BIO test sites was developed to explain the different concepts (MSP, trade-offs analysis, ES, how to map ES, etc.) and to obtain insights from the partner’s expertise. Furthermore, the methodology was detailed in these guidelines to help the responsible partner of the test sites to tailor the method to achieve their specific goals.

These guidelines were divided into different parts: the definition of the concepts (trade-offs, ES and trade-offs analysis in MSP, methodology to map ES participatory mapping) and the step-by-step methodology for the practice of trade-offs.

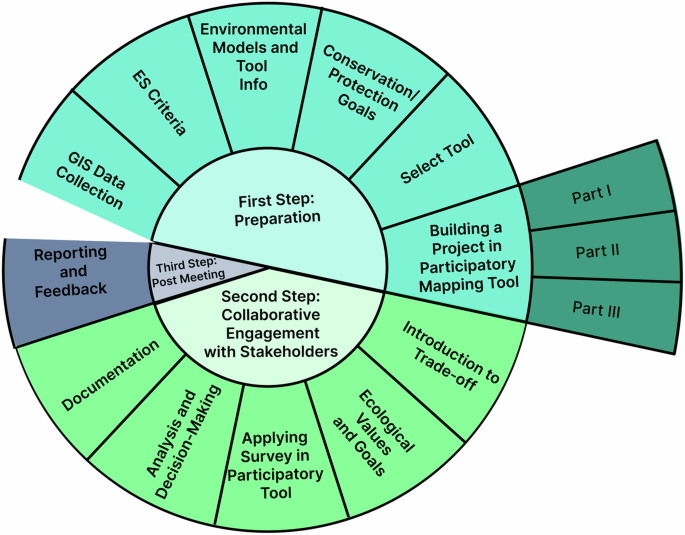

Training in using the participatory mapping tool

The aim was to develop a survey for participatory mapping on interested test sites22. A learning moment on how to use the participatory tool was needed. To this end, a training session was organised with the various test sites. The tool used by the partners was SeaSketch, an online participatory mapping platform. It is specifically designed to facilitate interaction between planners and stakeholders involved in MSP processes. The tool can be tailored to accommodate projects of varying scales, incorporating features such as data sharing, scenario planning, message boards, analytical functions, and other methods of engagement. The primary goal of the tool is to offer a user-friendly interface for accessing maps and map data pertinent to MSP52.

Participatory mapping, particularly with tools like SeaSketch, enhances the trade-off process by actively engaging stakeholders in visualising spatial data and shared perspectives. This fosters collaboration, improves transparency, and facilitates more informed decision-making that reflects the diverse interests and values of the community involved. By adopting participatory mapping, others can ensure that all relevant voices are included, leading to more equitable outcomes and a more thorough understanding of the potential impacts and trade-offs associated with MSP decisions.

Communities of practice

The methodology was tested within the CoPs of the project’s test site, aligned with the project’s aim of creating a collaborative development framework. The methodology was refined by engaging stakeholders in different regions to ensure it works effectively across diverse marine areas on different scales. This testing process helped create a robust framework incorporating input from various stakeholders, making it a valuable methodology in real-world planning. Workshops were organised at each test site to discuss the various scenarios with the stakeholders. The aim of these workshops was to map and negotiate the scenarios and carry out the climate change analysis.

Trade-off methodology/process for implementation of MPA (and other effective area-based conservation measures OECM)

The methodology to achieve the participatory development of integrated trade-off scenarios can be divided into three main steps (Fig. 4): preparation, which involves the initial groundwork to organise the workshop to be done within collaborative discussion; collaborative engagement with stakeholders, where insights, expertise, and perspectives are gathered through interactive workshops and discussions to drive consensus; and post meetings, aimed at synthesising the outcomes, reflecting on insights gained, and formulating actionable recommendations to enhance decision-making processes.

Trade-offs methodology for MPA design.

The aim of the trade-offs methodology is to be a guide for the conservation community (official agents, planners, decision-makers and MPA/MSP engagement teams). These steps should be considered whenever a change in the actual status of MPAs is envisaged (either in area dimension, re-allocation, new areas, new management measures or other changes with significant impacts on the initial agreed conservation goals). The detail of the trade-off methodology testing for MPA design is presented in Table 2.

Responses