NEIL1 block IFN-β production and enhance vRNP function to facilitate influenza A virus proliferation

Introduction

Influenza A viruses (IAVs) are common contagious pathogens involved in global pandemics and seasonal epidemics that pose a substantial global health burden and are transmitted among humans and animals, including poultry, pigs, dogs, and horses1,2. Due to individual differences in the immune response (susceptibility, duration, and intensity), IAV infection is more severe in some groups than in others, which may be related to host genetic factors affecting viral replication3. Multiple genome-wide screening methods used in different studies have also identified a large number of host factors that may contribute to IAV infection4,5,6. Validation studies have revealed host factors critical for IAV that act at different stages of viral replication, including entry and antiviral responses4. Currently, pathogens have evolved a variety of epigenetic strategies to enhance their survival and proliferation. These strategies include the direct modification of host proteins and chromatin via viral-specific gene products, which in turn reduces the sensitivity of antigen-specific receptors and signaling pathways, and modulates the expression of both immune system activators and suppressors. On the other hand, the host can also overcome pathogen-induced epigenetic changes and continue to mount an effective anti-pathogen immune response7,8.

The innate immune system is the host’s first line of defense against viral infection, and interferons (IFNs) are considered an important component of the innate immune response9,10. Type I IFNs (IFN-I) include IFN-a and β, as well as the less well-characterized IFNs τ and ω. Accumulating evidence suggests IFN-I are required for an antiviral response acting, in part, to prevent viral replication11,12. Recent reports suggest that blocking IFN-I signaling in virus-induced chronic infections reduces immunosuppression and accelerates clearance of persistent infections13,14. Gao et al.15 compared the induction of IFN-β during infection with the IAV strain H5N1 and found that the expression of IFN-I was significantly inhibited in infections with the highly pathogenic H5N1 strain. Therefore, precise regulation of IFN-I production is critical to maintaining host homeostasis. Transcriptional regulation of IFN-I has long been a focus of research due to its unique function in generating an antiviral response16; and IFN-β promoter is one of the most well-characterized and understood promoters of mammalian gene expression. Although it has been demonstrated in recent years that the aforementioned signal transduction and transcription factors (TFs) play a crucial role in IFN production, increasing studies have found that epigenetics also regulates IFN production17,18. Beyond histone posttranslational modifications and regulation of transcription cycle stages, DNA methylation functions in controlling IFN-β transcription15. The discovery of IFN-β-mediated epigenetic modification-associated factors that regulate IAV infection is critical for a comprehensive understanding of the potential role of epigenetic modification enzymes during IAV infection. Here, we performed a high-throughput sgRNA screen of 1041 known epigenetic modification factors to identify their potential roles in IFN-β-mediated inhibition of IAV replication.

This screen allowed us to identify nei endonuclease VIII-like 1 (NEIL1) as a key effector gene that represses IFN-β transcription after IAV infection. NEIL1 is a bifunctional DNA glycosylase of the Fpg/Nei family, which catalyzes the removal of damaged bases and subsequent incision of the newly generated basic sites19,20. NEIL1 is an essential enzyme for protecting genome stability in mammalian cells21. Consistent with this, NEIL1 abnormalities are associated with metabolic syndrome, immune disorders, and carcinogenesis22,23. In addition, several emerging literatures have demonstrated that NEIL1 may have a regulatory role in the active DNA demethylation process24,25.

The role of NEIL1 in immunity and RNA viruses is not described. The mechanism by which NEIL1 regulates IFN-β is also unknown. In this study, we explored the potential molecular mechanisms of NEIL1 to facilitate IAV proliferation. We found that NEIL1 plays a critical role in facilitating IAV replication and reveals that the NEIL1-NP binding interaction is an important innate immunomodulator for the IAV to escape the host defense system.

Results

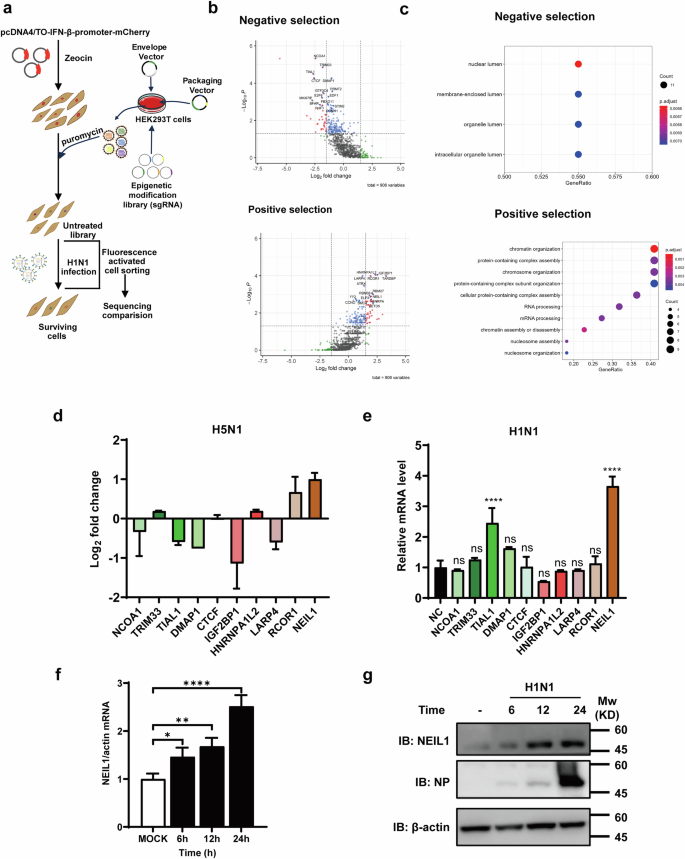

CRISPR-Cas9-based screening to identify epigenetic candidates regulating virus-induced IFN-β production

To explore the epigenetic modifier landscape of influenza virus-induced IFN-β regulation of immune response, we designed a high-throughput screening strategy, which was a genome-wide epigenetic modification enzyme knockout screening based on Lentivirus packaging CRISPR-Cas9 (EmCKO-screen) (Fig. 1a). First, we amplified the upstream 2000 bp promoter of human IFN-β in order to obtain much epigenetic genes involved in the regulation of IFN-β transcription. At the same time, the mCherry screening marker was inserted behind in the promoter region, which was ligated into a pcDNA4/TO vector to construct the pcDNA4/TO-IFN-β-promoter-mCherry plasmid and transfected into A549 cells. Cell lines stably expressing IFN-β-promoter-mCherry were obtained by zeocin screening. The lentiviral library generated from HEK293T cells was subsequently transfected with human epigenetic modifiers library and lentiviral helper plasmid. Overexpressing cell lines were infected with the lentivirus supernatants at a low MOI to ensure that the majority of cells received only one knockdown, and expanded in culture following puromycin selection. The cells expressing the mCherry red fluorescent signal, indicating activation of the IFN-β promoter, were isolated from the mixture by flow sorting after infection with H1N1. Additionally, uninfected H1N1 cells served as negative controls for clonal cell culture experiments (Supplementary Fig. 1). The whole-genome DNA was extracted for DNA sequencing. Using the MAGeCK algorithm, we compared the number of genes targeted by sgRNA in cells infected with or without H1N1, and identified the best candidate genes both positive regulators and negative regulators of IFN-β. We plotted volcanoes for positively and negatively selected genes and depicted the top 15 genes (Fig. 1b). Among these major targets, knockdown of HNRNPA1 and IGF2BP1 was previously reported to promote IFN-I expression26,27, and CTCF has been previously reported to interact with IFN-I28,29, thereby confirming the validity of our screening system. Subsequent functional enrichment analysis of the above candidate genes (Fig. 1c) showed that the positive selection IFN-β was mainly enriched with chromatin organization, protein-containing complex assembly, protein-containing complex subunit organization, and RNA processing, while the negative selection was enriched mainly for nuclear lumen, membrane-enclosed lumen, organelle lumen, and intracellular organelle lumen. To determine the effects of candidate genes on the influenza virus, we performed a secondary screen. Ten genes were selected from positive and negative selection, respectively, and the expression levels of these candidate genes were investigated in highly pathogenic influenza H5N1 (A/Turkey/582/2006). Transcriptomic data (GSE22319) are available in the GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo)30. The transcript level of NEIL1 was significantly upregulated in cells infected with H5N1, whereas the transcript level of IGF2BP1 was downregulated (Fig. 1d). Subsequently, a significant increase in the transcript level of NEIL1 was observed in cells of A549 infected with H1N1 (Fig. 1e). The analysis and whole-genome sequencing suggested that NEIL1 is a strong candidate for playing a role in the process of H1N1 infection. Subsequently, qPCR and Western blot confirmed the reliability of the transcriptomic data. Specifically, NEIL1 mRNA (Fig. 1f) and protein expression (Fig. 1g) gradually increased over time after infection with H1N1. All these data suggest that NEIL1 plays a potent role in IFN-β-mediated influenza virus replication.

a Schematic diagram of the genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 screening. Stable cell lines were obtained by transfection of A549 cells with pcDNA4/TO-IFN-β-promoter-mCherry plasmids and screening with zeocin. Then, a library of CRISPR/Cas9 KO-screened A549 overexpressing cells was infected with PR8 (1 MOI). Cells with different fluorescence signals were subsequently obtained by flow cytometric sorting, and gDNA was extracted for sequence analysis. Genes enriched were then compared with those from uninfected cells. b Volcano plots identifying candidate genes enriched upon positive and negative selection identified. c The bubble diagram of enrichment analysis on gene functions. Candidate genes positive screening: filter candidate genes by pos|rank, pos|p value < 0.05. Candidate genes negative screening: sorted by neg|rank, neg|p value < 0.05 screening candidate genes. And the candidate genes obtained from the screening were enriched and analyzed. d Distribution of differentially expressed genes (positive and negative selection) by log2 foldchange from cells infected with H5N1 from GEO database. e The mRNA expression of different positive and negative selected genes was analyzed by qPCR in cells of A549 infected with PR8 (0.5 MOI). f qPCR analysis of NEIL1 in A549 inoculated without or with PR8 (0.5 MOI) at the indicated times. g A549 were infected without or with PR8 (0.5 MOI) for 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h. The cells were then harvested to detect NEIL1 by western blotting using a rabbit anti-NEIL1 polyclonal antibody. Data were presented as the mean ± SD from three repeated experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001, ns, no significance, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

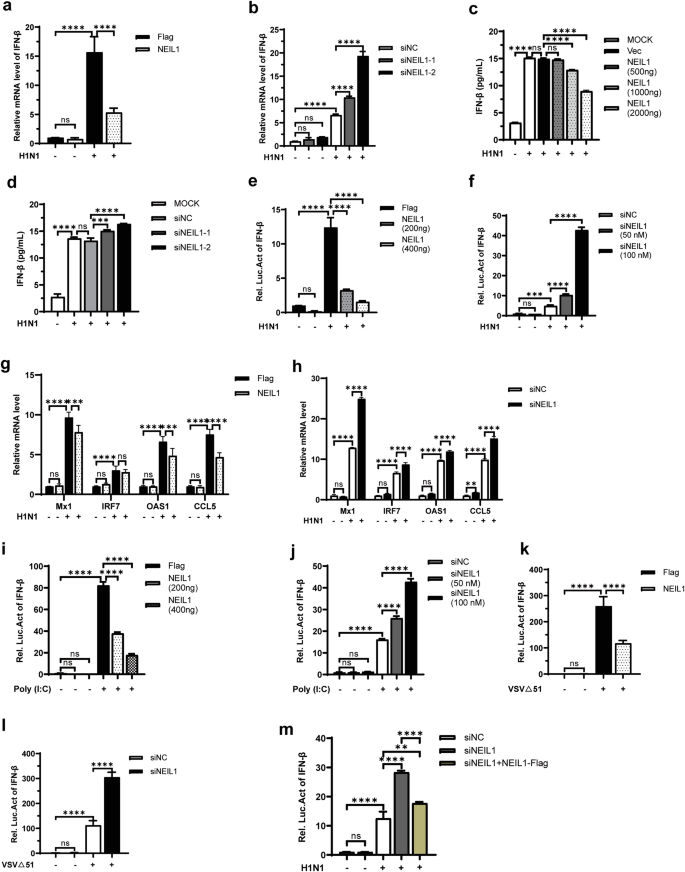

NEIL1 negatively regulates IFN-β and its downstream related gene production caused by RNA virus

We next focused on investigating the effect of NEIL1 on virus-induced IFN-β production. Firstly, the IFN-β mRNA level was investigated after IAV H1N1-inoculated and compared with overexpressing and interfering with NEIL1. The knockdown effects of NEIL1 were analyzed by qRT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Overexpression of NEIL1 significantly inhibited H1N1-induced IFN-β production (Fig. 2a), whereas interference with NEIL1 increased IFN-β expression (Fig. 2b). Moreover, ELISA assay discloses that the secretion of IFN-β from the supernatants of H1N1-infected A549 cells significantly inhibited after overexpression NEIL1 (Fig. 2c), instead, silencing of NEIL1 significantly elevated the secretion in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2d). To investigate the effect of NEIL1 in activation of IFN-β in HEK293T cells, we co-transfected HEK293T cells with NEIL1-Flag, IFN-β-Luc and pRL-TK reporter plasmids, and then infected with H1N1. After 12 h of infection, cell lysates were prepared to assess the luciferase activity driven by IFN-β promoter. Meanwhile, IFN-β-Luc and pRL-TK reporter plasmids were transfected after interfering with NEIL1 in HEK293T, and then infected with H1N1 to detect luciferase activity. The results showed that H1N1-mediated IFN-β promoter activity was inhibited in the presence of NEIL1 (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 2b), whereas interference with NEIL1 significantly increased H1N1-induced IFN-β promoter activity in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 2c). To verify whether the regulation of IFN-β levels by NEIL1 could affect the expression of ISGs, we examined the expression of IFN-stimulating factors (ISG) in A549 cells stimulated by H1N1 using qPCR after NEIL1 overexpression or knockdown. The results showed that NEIL1 overexpression suppressed mRNA expression levels of ISGs (MX1, OAS1, and CCL5) induced by H1N1 (Fig. 2g). On the contrary, NEIL1 knockdown promoted ISGs (MX1, IRF7, OAS1, and CCL5) mRNA expression levels induced by H1N1 compared with controls (Fig. 2h). We next sought to determine the effects of NEIL1 on RNA virus-induced IFN-β production. Further, when the production of IFN-β was induced by treating cells with double-strand RNA (poly (I:C)), mimicking the infection of RNA viruses31, overexpression of NEIL1 significantly inhibited the activation of IFN-β promoter in reported assays (Fig. 2i). In contrast, the poly (I:C)-induced in IFN-β promoter activity was upregulated after interference with NEIL1 (Fig. 2j). The effect of NEIL1 on IFN-β production induced by other RNA viruses was next investigated by stimulating NEIL1-treated HEK293T cells with vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)∆51. Consistent with the above results, we observed a significant decrease in IFN-β promoter activity in the overexpressed NEIL1-treated group relative to the control group post infection with VSV∆51 (Fig. 2k). The IFN-β promoter activity was strengthened after interference with NEIL1 and infection of VSV∆51 (Fig. 2l). Besides, we carried out relevant experiments and found that compensation of NEIL1 in IAV-infected cells attenuated the promotion of IFN-β by NEIL1 knocking down. These above results demonstrated that NEIL1 negatively regulated RNA virus-mediated IFN-β production, which further affects ISG expression.

a, b qPCR was used to analyze the relative mRNA expression level of IFN-β from A549 after overexpression (2 μg) (a) or knockdown (50 nM) (b) of NEIL1 and induced with or without infection by PR8 (0.5 MOI) for 12 h. c, d The protein level of IFN-β in cell supernatants was detected by EILSA after overexpression (c) or interference (d) of NEIL1 and infection of A549 cells with or without PR8 (0.5 MOI) for 12 h. e, f Luciferase activity in HEK293T cells transfected with IFN-β promoter (IFN-β-Luc) and Various concentrations of Flag-NEIL1 (e) or siNEIL1 (f) were detected 12 h post with or without infection by PR8 (0.5 MOI). g, h After NEIL1 (g) or siNEIL1 (h) transfection in A549 cells infected with PR8 (1 MOI), the mRNA levels of Mx1, IRF7, OAS1, and CCL5 were determined by qPCR. i, j At 24 h post-transfection of IFN-β-Luc, NEIL1 (i), or siNEIL1 (j) transfection, HEK293T cells were transfected with or without poly (I:C), and 12 h later the cells were harvested for dual-luciferase reporter assay. k, l Dual-luciferase analysis of IFN-β-Luc in HEK293T cells transfected for 24 h with NEIL1 (k) or siNEIL1 (l), with or without infection by VSV∆51 for another 12 h. m Luciferase activity in HEK293T cells transfected with IFN-β promoter (IFN-β-Luc), siNC, siNEIL1 and siNEIL1 + NEIL1-Flag were detected 12 h post with or without infection by PR8 (0.5 MOI). ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001, ns, no significance, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. Data were one representative of three independent experiments.

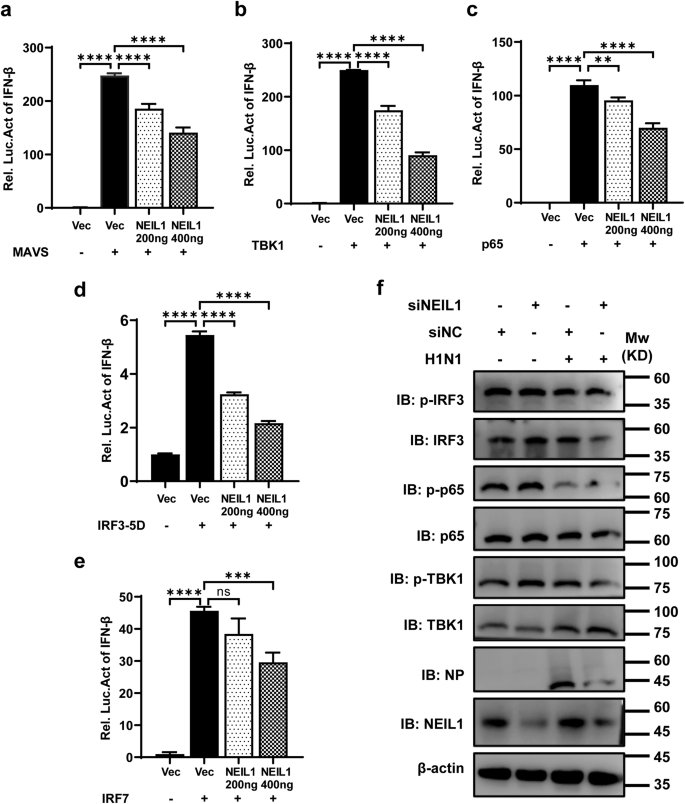

NEIL1 suppressed the transcriptional activation of IFN-β

RIG-I-like receptors recognize cytosolic RNA and then activate MAVS, which physically interact with TBK1 to phosphorylate and activate IRF3 or IRF7, resulting in IFN-I production32,33. We know overexpression of these signal pathway plasmids activate IFN-I production. To elucidate the underlying mechanisms by which NEIL1 reduced the IFN-β production, we tested the effects of NEIL1 on the activation of IFN-β promoter by transfected plasmids related to IFN activation signaling pathway, including proximal regulators (MAVS, TBK1) and key transcriptional factors (p65, IRF3, and IRF7). Overexpression of NEIL1 suppressed IFN-β promoter-reporter activation by MAVS, TBK1, p65, IRF3-5D, and IRF7 in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 3a–e). To test whether NEIL1 uses additional mechanisms to target the IFN-I signaling pathway, we assayed phosphorylated TBK1 (p-TBK1), phosphorylated IRF3 (p-IRF3), and phosphorylated p65 (p-p65) in A549 cells interfering with NEIL1 after H1N1 infection. In contrast to the lower IFN-β expression (Fig. 2a–c), western blotting data indicated that knockdown of NEIL1 did not obviously promote PR8-induced phosphorylation of TBK1, p65, and IRF3 (Fig. 3f). Collectively, our data suggested that NEIL1 inhibited IFN-β transcriptional activation without impacting TBK1-IRF3 activation and that the action target is located in the nucleus. The NEIL1 might function downstream of IRF3/IRF7 and directly acts on the IFN-β locus to impact IFN production.

a–e HEK293T cells were co-transfected with the plasmids encoding IFN-β-Luc, inter-control vector pRL-TK, expression plasmids for MAVS (a), TBK1 (b), p65 (c), IRF3-5D (d) and IRF7 (e), with or without NEIL1. At 24 h post-transfection, luciferase assays were performed with a dual-specific luciferase assay kit and results were normalized by renilla luciferase activity. f Western blotting analysis of indicated protein expression in HEK293T cells interfering with NEIL1 after challenge with or without PR8 (1 MOI) for 12 h. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001, ns, no significance, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. Data were one representative of three independent experiments.

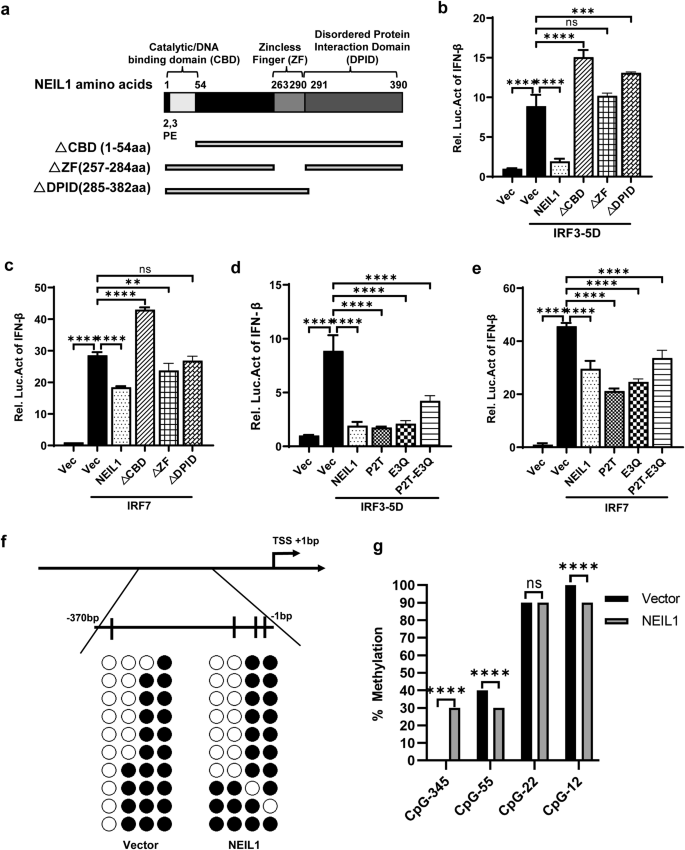

The functional domain of NEIL1 is crucial for the suppression of IFN-β transcription

In addition to histone posttranslational modifications and regulation of the stages of the transcription cycle, DNA methylation can also play a role in controlling IFN-β transcription15. 5-mC is associated with the repression of regulatory DNA and endogenous retro-element repression34. The NEIL glycosylases can excise oxidized cytosines by the BER machinery and may activate demethylation and reactivation of epigenetically silenced genes24. We were surprised to observe that NEIL1 decreased IFN-β production, so we next questioned whether the enzymatic activity of NEIL1 was critical for IFN-β production. To explore the effect of NEIL1 on the function of IFN-β, we designed a truncated plasmid according to the functional domain of NEIL135. A recent study generated NEIL1 with a site-directed mutation in the catalytic N-terminal proline or glutamic acid residues (P2T and E3Q) is inactive35,36. We deployed three different glycosylase activity dead mutants (P2T, E3Q, and double-mutant P2T + E3Q) (Fig. 4a). HEK293T cells vector, wt NEIL1 and the NEIL1 mutants (sit mutants or functional truncation mutants) were overexpressed in HEK293T cells to analyze their suppressive function using an IFN-β luciferase assay stimulated with IRF3-5D or IRF7. Functional truncation35,37 mutants ∆CBD (Catalytic/DNA binding domain), ∆ZF (Zincless Finger), and ∆DPID (Disordered Protein Interaction Domain) could reverse the inhibition of IFN-β by wt NEIL1 to levels comparable to that found in the control vector (Fig. 4b, c and Supplementary Fig. 3b). In contrast, glycosylase-dead mutants of NEIL1 (P2T, E3Q, and P2T + E3Q) inhibited IFN-β luciferase activity induced by IRF3-5D (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 3a) and IRF7 (Fig. 4f) in a manner similar to that of full-length wt NEIL1. All those suggest that each functional domain (CBD, ZF, and DPID) of NEIL1 is critical for IFN-β suppression, but the DNA glycosylase enzymatic activity of NEIL1 is dispensable.

a Domain map of the structure of NEIL1 is displayed. The active site and DNA binding motifs are indicated in the domain map. b, c Effect of NEIL1 structural domain deletion on the IFN promoter. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with t NEIL1 and different NEIL1 deletion mutants plasmids, IFN-β-Luc, pRL-TK, IRF3-5D (b) and IRF7 (c). At 24 h post-transfection, luciferase assays were performed with a dual-specific luciferase assay kit and results were normalized by renilla luciferase activity. d, e Effects of wt NEIL1 and its glycosylase-dead mutants on the IFN promoter. HEK293T cells were transfected with wt NEIL1 and different NEIL1 mutants (P2T, E3Q and P2T + E3Q), IFN-β-Luc, pRL-TK, IRF3-5D (d) and IRF7 (e), and at 24 h post-transfection, luciferase assays were analyzed. f, g Analysis of IFN-β promoter methylation status of HEK293T expressing vector or NEIL1 after infection of PR8 (1 MOI) for 12 h. f Schematic depiction of the IFN-β promoter. Short vertical lines represent the 4 CpG dinucleotides studied. Results are shown of bisulfite genomic PCR (BSP) of 10 individual clones in vector and NEIL1. The presence of a methylated (black circles) or unmethylated (white circles) cytosine is indicated. g Statistics and analysis of methylation status of each CpG site of the IFN-β promoter by BSP. **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001, ns, no significance, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. Data were one representative of three independent experiments.

Furthermore, to examine the methylation level on the IFN-β promoter, we studied, by bisulfite genomic PCR (BSP), the methylation levels of 4 CpG sites located around 350 bp upstream of the translation starting site of the IFN-β promoter. The BSP results showed that the GC site (−345) away from the IFN-β transcription start site (TSS) was unmethylated in untreated cells after infection with the influenza virus, and NEIL1 overexpression significantly increased the methylation level of the IFN-β promoter (Fig. 4f, g). However, neighboring the GC site of the TSS (−55 and −12), NEIL1 treatment slightly reduced (by 10%) IFN-β methylation. Interestingly, sequencing at the specific site (site −22 of the IFN-β TSS)15 revealed that the methylation level of this particular GC site was conserved (90%) with or without NEIL1 treatment (Fig. 4f, g). The above results demonstrate that the functional domain (CBD, ZF, and DPID) of NEIL1 plays a crucial role in the regulation of IFN-β, and NEIL1 may affect the methylation status of IFN-β at different sites to regulate its expression.

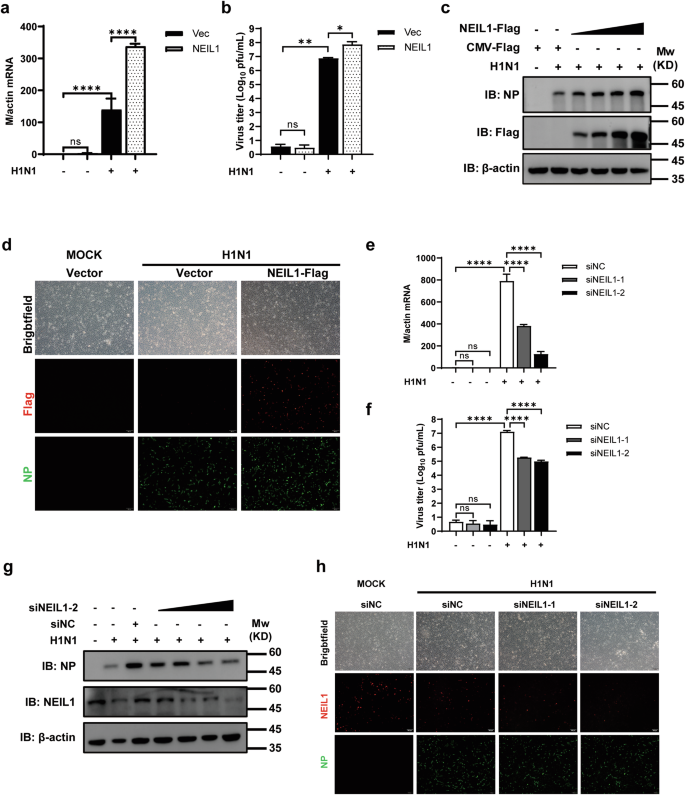

NEIL1 has a positive effect on IAV replication

Based on the above findings, we verified that IAV positively regulated host NEIL1(Fig. 1) and NEIL1 inhibited the expression of IFN-β (Figs. 2 and 3). To validate the role of NEIL1 in IAV replication, the NEIL1-flag plasmid was transfected into A549 cells following IAV infection. QPCR assay data showed that NEIL1 overexpression increased the influenza virus matrix (M) gene relative expression and gene copy numbers (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 4a). Also, the culture supernatant was harvested at 24 h post infection. For titration of infectious virus by using plaque assays, the results showed that overexpression of NEIL1 led to a 2.3-fold increase in viral titers at 24 h post infection (Fig. 5b). Western blotting showed that high-dose overexpression of NEIL1 promoted nucleoprotein (NP) protein of PR8 expression compared with control (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 4b). As expected, NP was increased in NEIL1-expressing A549 cells by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy using a mAb against IAV NP (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 4c). Next, we examined the effect of NEIL1 downregulation on virus replication by using NEIL1 knockdown. The data revealed that NEIL1 knockdown led to a significant decrease in M gene relative expression and gene copy numbers using qPCR assays (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 4d). Meanwhile, the viral titers in two siNEIL1 of A549 cells dropped 2.6- and 5-fold compared to that control A549 cells respectively (Fig. 5f). We also measured the expression levels of viral proteins in A549-NEIL1 knockdown and control cells. Viral NP protein expression was lower in A549 cells transfected with siNEIL1 and in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5g and Supplementary Fig. 4e, f). Besides, NP expression was slightly downregulated in NEIL1 knockdown A549 cells as observed by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy using mAb against IAV NP (Fig. 5h and Supplementary Fig. 4g). Our findings suggest that cellular NEIL1 is essential for positive regulation of IAV infection.

a–c NEIL1-expressing or control A549 cells were infected with or without PR8 (0.5 MOI) for 24 h, and cells and supernatants were collected for qPCR, plaque, and Western blotting. a PR8 M mRNA was detected by qPCR. b PR8 viral titer was determined by plaque assay on MDCK cells. c Western blotting analysis showing the expression of PR8 NP protein by different doses of NEIL1. d Indirect immunofluorescence analysis of A549 cells overexpressing vector or NEIL1 infected with PR8 (5 MOI) using anti-Flag (red) combined with anti-NP (green). Cells were observed under a laser confocal imaging analysis system. e, f Two siRNAs targeting host NEIL1 were designed and transfected into A549 cells, followed by infecting with PR8 (0.5 MOI) for 24 h. The relative expression of the PR8 M gene using qPCR (e) and virus titer testing by plaque assays on MDCK cells (f) were carried out after collecting cells and supernatants. g Western blotting analysis of NP protein in A549 cells were transfecting siNC or siNEIL1-2, followed by infecting with PR8 (0.5 MOI) for 24 h. h Indirect immunofluorescence analysis of A549 cells transfecting siNC or siNEIL1 infected with PR8 (5 MOI) using anti-NEIL1 (red) and anti-NP (green). Cells were observed under a laser confocal imaging analysis system. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001, ns, no significance, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. Data were one representative of three independent experiments.

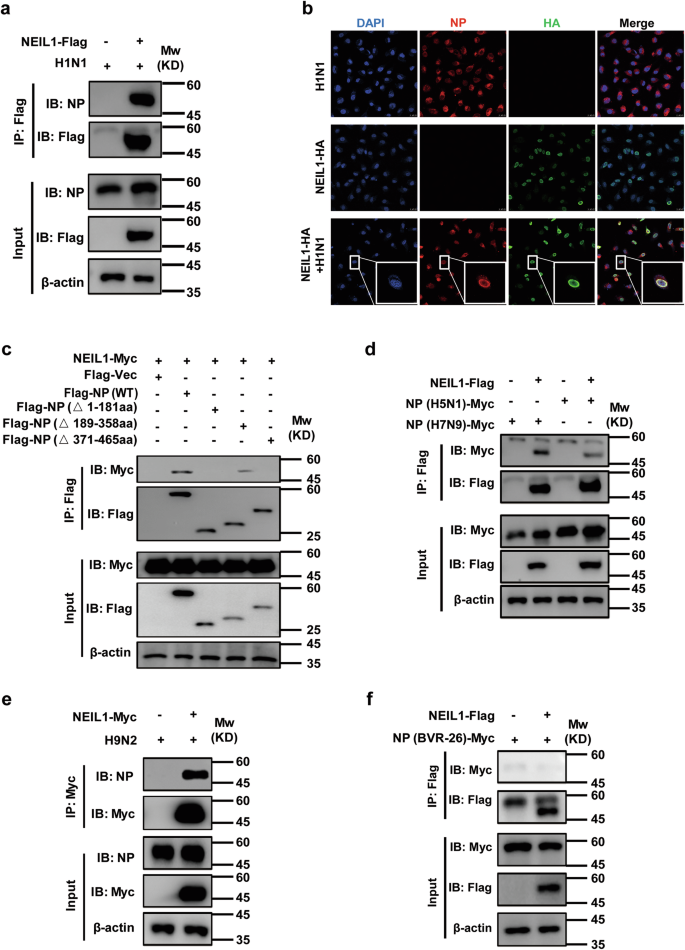

NEIL1 interacts with the NP of IAV

Considering that NEIL1 has a promotion effect on IAV proliferation, we determined whether NEIL1 was directly associated with IAV replication. First, we examined if NEIL1 physically interacts with the viral proteins of IAV. We identified NP as a viral protein potentially interacting with NEIL1 using immunoprecipitation combined with mass spectrometry screening (Supplementary Fig. 5a). To prove our hypothesis, we first checked whether IAV NP protein could interact with NEIL1 in transient-transfection experiments. We performed co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments in HEK293T cells transfected with epitope-tagged NP and NEIL1. As indicated in Supplementary Fig. 5b, epitope-tagged NP and NEIL1 were co-immunoprecipitated in HEK293T cells. To further explore the interaction between NEIL1 and NP during IAV infection, PR8 were incubated with HEK293T cells transfected with or without NEIL1, and then subjected to co-IP of the cell lysates post infection 24 h.

We found that IAV NP efficiently interacted with NEIL1 during virus replication (Fig. 6a). Consistent with this observation, our immunofluorescence staining showed that NEIL1 co-localized with NP in cell nuclei (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 5c). The NP protein, composed of 498 amino acids, is a major component of viral ribonucleoprotein complex (vRNP)38. It contains an RNA-binding region at its N terminus (residues 1–181)39 and two domains, responsible for NP-NP dimer formation at residues 189–358 and 371–46540. In an attempt to map the region of IAV NP responsible for interaction with NEIL1, we created three truncate variants and investigated them in co-immunoprecipitation experiments (Supplementary Fig. 5d). Deletion of the RNA-binding region at N terminus (amino acids 1–181) and NP-NP self-interaction at C-terminus (amino acids 371–465) completely abolished the binding of NP to NEIL1, whereas deletion of NP-NP self-interaction at middle domains did not affect interactions with NEIL1 (Fig. 6c). This suggests that the N- and C-termini of NP are regions essential for interaction with NEIL1.

a, e Co-IP analysis of the interaction of NP with NEIL1 in HEK293T or DF-1 cells transfected with NEIL1 plasmids and infected with PR8 (a) or H9N2 (e) virus (5 MOI) for 24 h. b Co-localization of HA-tagged NEIL1 (green) and NP (red) in PR8 (5 MOI) infected Hela cells. Nuclei stained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bars, 10 μm. c Co-IP analysis of the interaction of NP with NEIL1 and its truncation mutants in HEK293T cells. d Interaction of Myc-tagged H5N1-, H7N9-NP constructed from Tsingke Biotechnology and Flag-tagged NEIL1 in HEK293T cells by using a co-IP assay. f Interaction of Myc-tagged NP from BVR-26 and Flag-tagged NEIL1 in HEK293T cells by a co-IP assay. Data are one representative of three independent experiments.

NP is highly conserved among each type of influenza virus (A and B) and has received significant attention as a good target for universal influenza vaccine41. Next, we evaluated the interactions of NEIL1 with more influenza strains NP. The co-IP results showed that NEIL1 interacted with NP proteins of H5N1, H7N9, and avian H9N2 strains (Fig. 6d, e). However, for the NP proteins of influenza B viruses, no interaction with NEIL1 was found (Fig. 6f). The vRNP complex of AIV is composed of RNA, NP, and the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP: PB2, PB1, and PA)42, thus, we wish to address the specificity of the interaction between NEIL1 and other vRNP subunits. HEK293T cells expressing Flag-tagged NEIL1 were infected with or without H1N1, and we found that NEIL1 only co-immunoprecipitated with NP, but there was no interaction between NEIL1 with PB2, PB1, and PA (Supplementary Fig. 5e). Together, our results indicated that NEIL1 interacts with IAV NP in transiently transfected mammalian cells.

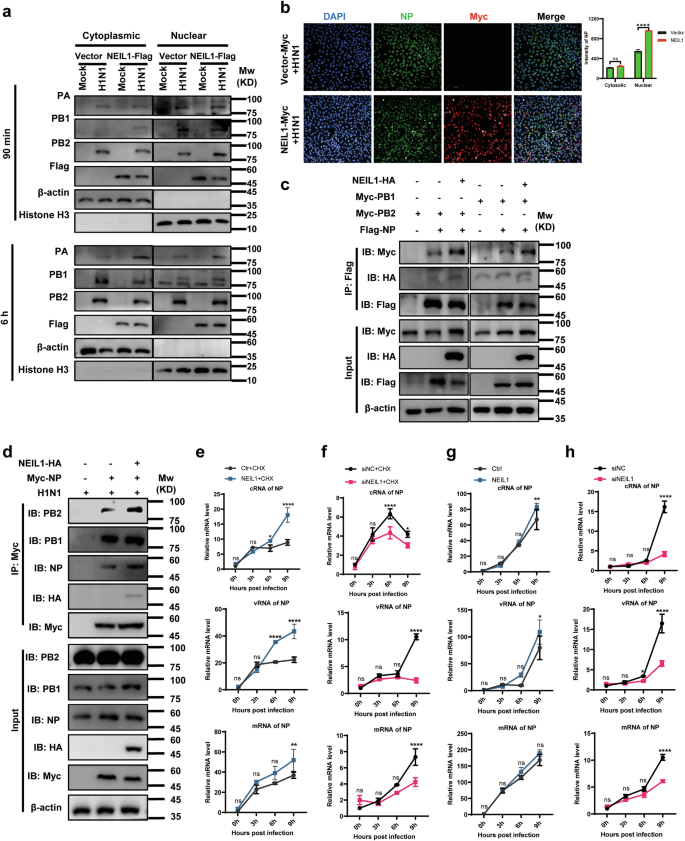

NEIL1 contributes to vRNP nuclear trafficking and efficient influenza viral replication

As previously described NEIL1 is expressed in the nucleus43 and was identified to localize with NP in the nucleus and promote IAV replication by the above assay. In addition to being a structural RNA-binding protein, NP is a key adapter between viral and host cellular processes, as it is essential for nuclear or cytoplasmic trafficking of vRNP44,45,46.

Hence, to test whether NEIL1 inhibits vRNP formation, NEIL1-expressing A549 cells were infected with H1N1, and then nuclei and cytoplasm were fractionated at early time points after infection. At 90 min post infection, levels of H1N1 vRNP-containing proteins in cytoplasmic and nuclear fractionation of mock and NEIL1-expressing cells indicated that the efficiency of viral vRNP nuclear import was slightly higher in NEIL1-expressing cells in A549 (Fig. 7a, top panel). At 6 h post infection, the levels of H1N1 vRNP protein in the cytoplasm of mock and NEIL1-expressing cells were reduced compared to 90 min (Fig. 7a, top panel and Supplementary Fig. 6a). However, vRNP proteins (especially NP and PB2) were significantly more expressed in the nuclei of NEIL1-expressing cells than in controls (Fig. 7a, bottom panel and Supplementary Fig. 6b). Subsequently, we investigated the distribution and expression of NP protein in the cytoplasm and nucleus of Hela cells 12 h post infection using a high-throughput imaging system. The fluorescence intensity of NP in the nucleus was higher than that in the cytoplasm after infection with H1N1, and the fluorescence intensity of NP in the nucleus of NEIL1-expressing Hela was noticeably higher than that in the empty vector group (Fig. 7b). These data further illustrate that NEIL1 promotes vRNP entry into the nucleus.

a A549 expressing vector and NEIL1 cells were infected with PR8 (1 MOI). Following nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation, vRNP components and cellular markers were detected by western blotting. b Image acquisition and nuclear and cytosolic fluorescence intensity analyzed using Operetta high-content imaging system (Perkin Elmer) after infected with PR8 for 6 h. c Co-IP detects the effect of NEIL1 on the interaction of NP with PB2 and PB1. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with plasmids expressing Myc-tagged PB2, PB1, Flag-tagged NP, and HA-tagged vector or NEIL1. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with a mouse anti-Flag mAb. d The effect of NEIL1 on the interaction of NP with PB2 and PB1 during IAV infection by co-IP assays. HEK293T cells were transfected for 24 h to express Myc-tagged NP and HA-tagged NEIL1 and were then infected with PR8 virus (5 MOI). At 24 h post infection, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with a mouse anti-Myc mAb. e, g A549-vector and A549-NEIL1 cells were treated (e) or untreated (g) with 100 μg mL−1 CHX and infected with PR8 (1 MOI) of three RNA species were quantified by a two-step RT-qPCR at indicated time points. f, h A549-siNC and A549-siNEIL1 cells were treated (f) or untreated (h) with 100 μg mL−1 CHX and infected with PR8 (1 MOI) of three vRNA species were quantified by a two-step RT-qPCR at indicated time points. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001, ns, no significance, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. Data were one representative of three independent experiments.

In addition, NP interacted with components of the polymerase protein complex (PB1 and PB2) but not PA44. From the front results, we verified that NEIL1 did not physically interact with PB2 and PB1 (Supplementary Fig. 5e). This made us speculate whether NEIL1 could mediate the interaction between NP and PB2, in turn, affect the stability of the RNA complexes. First, we found addition of NEIL1 resulted in reinforcing interaction of NP with PB2 and PB1 by immunoprecipitation of overexpression of NEIL1 and RNP complexes (Fig. 7c). To investigate whether this effect of NEIL1 is consistent during IAV infection, HEK293T cells were transfected with constructs for the expression of Myc-tagged NP and HA-tagged-vector or NEIL1, followed infecting with H1N1 (PR8). At 24 h post infection, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Myc mAb. The results revealed that NEIL1 significantly promoted the interaction of NP with PB2 in the presence of IAV infection (Fig. 7d). The above results confirm that NEIL1 contributes to the entry of vRNP into the nucleus, which in turn improves the stability of NP with PB2.

The transcription and replication of the lAV genome take place in the nucleus of virus-infected cells47,48, catalyzed by the vRNP49. We next tested whether vRNP replication activity was affected by NEIL1 using qPCR assays to measure viral mRNA, vRNA, and cRNA species at early time points after infection in the presence or absence of cycloheximide (CHX, a translation elongation inhibitor). The inhibitory effect of CHX on protein synthesis results in attenuation and/or inhibition of lAV genome replication activity that is dependent on newly synthesized NP monomers50. In this case, the vRNA level represents the amount of virus initially inoculated. After infection with AIV, the expression levels of mRNA, cRNA and vRNA of the NP gene of AIV were significantly upregulated in cells overexpressing NEIL1 (Fig. 7e), in which the up-regulation levels of cRNA and vRNA were more obvious relative to mRNA, while cRNA was the template for synthesizing RNA of the zygotic virus, and newly synthesized vRNA served as the genome of the zygotic virus. Meanwhile, the knockdown of NEIL1 was able to inhibit vRNA replication of AIV (Fig. 7f). In CHX-untreated cells, viral cRNA, vRNA, and mRNA levels were insensitive to NEIL1 for the first 6 h post infection, but cRNA, vRNA subsequently increased at 9 h (Fig. 7g). Meanwhile, cRNA, vRNA and mRNA accumulation was significantly reduced after 6 h in NEIL1 knockdown cells (Fig. 7h). Collectively, these data indicate that NEIL1 positively affects lAVs mainly at the level of viral genome replication and transcription.

Discussion

After pathogen sensing, rapid and robust induction of IFN is often required to mount an effective antiviral response. IFN is a key component of the innate immune response to exogenous viruses. Type I IFNs (IFN-α and IFN-β) are required for an antiviral response by acting, in part, to prevent viral replication. Owing to the heterogeneity of the IFN-α gene, less is known about their transcriptional regulation51. In this study, we performed a high-throughput screening of epigenetic modifiers by lentivirus-mediated sgRNA to search for the epigenetic factors involving in IFN-β-mediated regulation of influenza response. This approach yielded the discovery and successfully identified that the Nei-like 1 (NEIL1) is a critical effector molecule that negatively regulates IFN-β production. Our data revealed that NEIL1 negatively regulates IFN-β and its downstream related genes (Mx1, IRF7, OAS1, and CCL5) production caused by RNA viruses, including H1N1 and VSV (Fig. 2). RNA viruses promote TBK1 through TLR-mediated signaling or by recruiting TBK1 into mitochondrial antiviral signaling through RIG-I52,53. When TBK1 is activated, it further phosphorylates IRF3 and triggers translocation of the IRF3 homodimer from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Nuclear IRF3 binds to the positive regulatory domain (PRD) region of the IFN-I promoter, and IFN-β is transcribed. Our study confirms the involvement of the epigenetic modifier enzyme NEIL1 in controlling the induction of IFN-β. NEIL1 in the nucleus exerts an inhibitory effect on IFN-β production via the MAVS, TBK1, p65, IRF3-5D, and IRF7 induction, and its transcriptional repression is not dependent on the phosphorylation of TBK1, p65, and IRF3 (Fig. 3). As an important epigenetic regulator factor, NEIL1 contains several structural domains CBD, ZF, and DPID, each of which play an important role, and we found that all functional domain of NEIL1 is critical for IFN-β suppression (Fig. 4).

Previous evidence reveals that epigenetic modifications are involved in antiviral host defense in IAV-infected hosts and these changes in DNA methylation promote the expression of certain pro-inflammatory genes54. Cells infected with pathogenic H1N1 IAV showed a significant reduction in DNA methylation levels on the promoter region. In addition, another study reported different strains of IAV resulted in obvious changes in DNA methylation levels55. During active DNA demethylation, thymine DNA glycosylases (TDG) excise 5fC and 5caC, resulting in base-free (AP) sites and subsequent DNA single-strand damage. They can be finally repaired by the base excision repair (BER) pathway and converted to C bases. Recently, NEIL1 has been recruited by TDG to participate in TET-mediated DNA demethylation37. Previous studies have found that TET2 (tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 2) restrains mitochondrial DNA-mediated IFN signaling in macrophages56, and TET3 (tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 3) inhibits type IFN-I production independent of DNA demethylation57. We found that NEIL1 was able to directly regulate IFN-β transcription (Fig. 2). Moreover, the glycosylase-dead mutant of NEIL1 was capable of suppressing IFN-β transcription to levels similar to those of wt NEIL1. This suggests that NEIL1 regulation of IFN-β expression is independent of enzyme activity. Studies have reported that a specific methylation site in the IFN-β promoter directly contributed to IFN-β transcription15. However, our results found that the methylation of this site (CpG-22) was not altered and regardless with NEIL1 treatment, whereas NEIL1 treatment showed variable results in methylation levels for the other GC sites. NEIL1 treatment caused a mild reduction in methylation levels in the IFN-β promoter region near the TSS (CpG-12 and CpG-55 site). Surprisingly, the GC site (CpG-345 site) in the IFN-β promoter region was significantly methylated (above 30%) after NEIL1 treatment. So, we speculate that CpG-345 is most likely the decisive methylation site for regulating the expression of IFN-β, which deserves further investigation. The methylation levels of different sites in the IFN-β promoter stimulated by NEIL1 suggest other mechanisms are involved in the transcriptional repression of IFN-β by NEIL1. Several studies have demonstrated that host proteins were dependent on the histone deacetylase HDAC1 to negatively regulate IFN-type responses, but not on DNA demethylation57,58. However, HDAC1 is not involved in deacetylating NEIL143,59. Thus, in the following work, we will focus on our research questions on solving whether there are other HDACs involved in the negative regulation of IFN-β by NEIL1.

Indeed, recent studies have demonstrated that the BER pathway plays an essential role in large DNA viruses and DNA glycosylases may play a crucial role in counteract viruses and cancer therapy60,61,62. However, DNA glycosylases have few reported for RNA viruses. Functional inhibition, gene ablation, and posttranslational modification of OGG1 have been described to significantly enhance IFN-λ expression in human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-infected epithelial cells63. Nei-like DNA glycosylase 2 (NEIL2) has been shown to antagonize nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), which acts at the IFN-β promoter, early after infection, thereby limiting gene expression of type I IFN amplification64. Maintaining basal levels of NEIL2 is essential for the host’s protective response to viral infection and disease65. In this paper, we found that NEIL1 was significantly upregulated in IAV-infected A549 cells (Fig. 1), suggesting that NEIL1 may play a role in influenza virus infection. Our further analyses revealed that NEIL1 positively regulates IAV replication (Fig. 5). Another interesting phenomenon in our study is that NEIL1 directly interacted with the NP of several influenza A virus, but not with influenza B virus (Fig. 6a, d–f). In addition, we further demonstrated that NEIL1 interacted with NP containing the N-terminal and C-terminal domain by overexpressing various truncated forms of NP (Fig. 6c). An increasing NEIL1 prompts the expression and nuclear distribution of NP post infection of IAV (Fig. 6). The ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex of influenza virus contains four proteins that are necessary for viral replication: PB1, PB2, PA and NP, those are implicated in the virulence of the influenza viruses66. Furthermore, we revealed that NEIL1 contributes to the entry of vRNP into the nucleus, which improves the stability of NP with PB2 and positively facilitates lAV biosynthesis mainly at the level of viral genome replication and transcription (Fig. 7).

Replication and transcription of influenza viruses depend on the involvement of various host factors in the cell67. Exploring the relationship between viral and host factors will help to understand the characteristics and pathogenic mechanisms of influenza viruses. Here, we show that NEIL1 functions as a pro-replicative agent of IAV by interacting with the NPs of IAV to promote NP entry into the nucleus, further stabilizing the vRNP complex. Furthermore, NEIL1 negatively regulates type I IFN signaling during IAV infection. Most importantly, NEIL1 represses IFN-β transcription and expression through its functional domain by acting directly on the IFN-β promoter and independent of its glycosylase activity. Since most glycosylases mediate IFN-β promoter activation mainly through HDAC1 regulation. However, NEIL1 is not regulated by HDAC159. Whether other HDACs are involved in the mechanism of IFN-β inhibition by NEIL1 needs to be further investigated in the future.

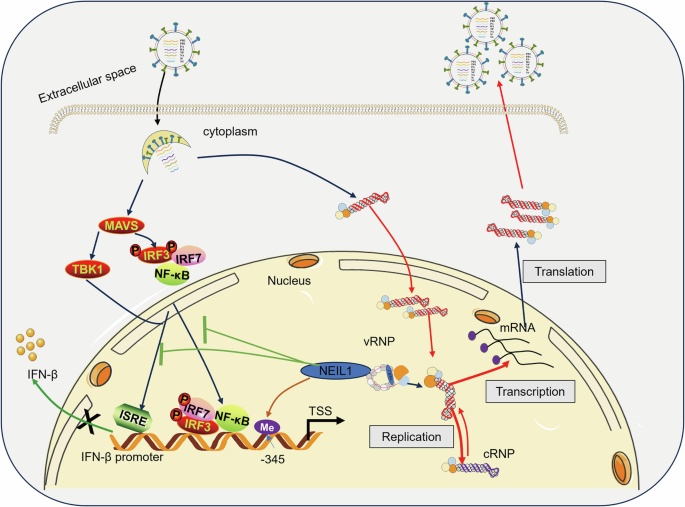

In addition to repairing DNA base damage to maintain genomic integrity, inflammatory responses, and cancer development, our study revealed the regulatory functions of NEIL1 on IAV (Fig. 8). Taken together, our findings provide new insights into the pathogenesis of IAV. The discovery and development of efficient, selective, and stable small molecule inhibitors of NEIL1 against IAV infection, as well as the identification of the relevant regulatory mechanisms of NEIL1, remain important goals for further study.

The schematic model of NEIL1 enhances IAV replication and suppresses the expression of IFN-β. NEIL1 facilitates the nuclear entry of the vRNP complex and its replicative transcriptional activity within the nucleus through interactions with NP proteins, thereby promoting the proliferation of IAV. In addition, NEIL1 is a key effector molecule that negatively regulates IFN-β production and modulates IFN-β expression by regulating the methylation status of multiple sites in the IFN-β promoter region in the nucleus, in particular the GC site located at position −345 upstream of the transcription start site (CpG-345).

Methods

Ethics statements

All cell experiments were performed in the Biosafety Lab of Level-2 of Tianjin University and carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China. (Certificate Number: TJUE-2022-067, Tianjin, China).

Cell culture and virus infection

Human lung epithelial cells (A549), human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293T), the chicken fibroblast cell line cells (DF-1), Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA, 11995065), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Lonsera, Shanghai, China, S711-001), and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA, 15070063) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. A/PuertoRico/8/34 (PR8) and B/Austria/1359417/2021 (BVR-26) were kindly provided by Zhongyianke Biotech Co. (Tianjin, China). A/chicken/Hebei/L1/2006(H9N2) were stored in our laboratory68. VSV∆a51 was stored in our laboratory.

CHX treatment consisted of incubating cells with 100 μg mL−1 for 1 h before infection. The viral inoculum and media used throughout the experiment also contained the same concentration of CHX.

For viral infection, the cell monolayers were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the virus inoculum was diluted in a serum-free medium (multiplicity of infection (MOl) used is specified in the relevant figures). After adsorption for 1 h at 37 °C, the cells were washed with PBS and cultured in DMEM containing 0.5 μg/mL TPCK trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich, #T8802). Generally, cells were infected at the multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01–5.0 plaque-forming units (PFUs) per cell.

Plaque assays

Plaque assays were performed using a modified protocol described previously69. Briefly, MDCK cells were seeded in 12-well plates to 90% confluence to the following day. And viruses were serially tenfold diluted and inoculated onto MDCK cell monolayers for 1.5 h at 37 °C. After incubation at 37 °C for 60 min, the inoculum was removed, and the cells were washed with 1× MEM and overlaid with 1 mL/well of media (2×DMEM (Gibco) containing 2% low melting point agarose (Yeasen, 10214ES08), 0.3% BSA and 0.5 μg/mL TPCK-treated trypsin). After a 48–72 h incubation, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 1 h. The agar layer was then gently removed, and stained with 0.5% crystal violet stain solution (Yeasen, 60506ES60). Plaques and viral titers were calculated as PFU/mL.

Antibodies and reagents

Rabbit anti-NEIL1 pAb (DF4041,1:1000) was purchased from Affinity (Jiangsu, China). Mouse anti-NP mAb (1:1000) was kindly contributed by Prof. Guohua Deng from Harbin Veterinary Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Rabbit anti-PB2 pAb (GTX125926, 1:1000), rabbit anti-PB1 pAb (GTX125923, 1:1000), and rabbit anti-PA pAb (GTX118991, 1:1000) were purchased from GeneTex. Rabbit anti-DYKDDDDK (Flag)-tag mAb (Proteintech, 80010-1-RR, 1:2000), rabbit anti-Myc mAb (16286-1-AP, 1:1000), mouse anti-Myc mAb (60003-2-Ig, 1:1000) and rabbit anti-HA mAb (51064-2-AP, 1:1000) were purchased from Proteintech (Rosemont, IL, USA). Rabbit anti-NF-kB p65/RelA mAb (p65) (A19653, 1:1000), rabbit anti-phospho-NF-κB p65 (Ser536) (p-p65) mAb (RK05776, 1:1000), rabbit anti-TBK1/NAK mAb (TBK1) (A3458, 1:1000), rabbit anti-phospho-TBK1/NAK-S172 mAb (p-TBK1) (AP1418, 1:1000), rabbit anti-IRF3 pAb (IRF3) (A2172, 1:1000) and rabbit anti-phospho-IRF3 mAb (p-IRF3) (RK05793, 1:1000) were purchase from ABclonal (Wuhan, China). Rabbit anti-β-actin pAb (30102ES40, 1:5000), Peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) (33101ES60, 1:5000), Peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) (33201ES60, 1:5000) were purchased from Yeasen Biotech (Shanghai, China). FITC-conjugated donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody (DkxMu-003-FFITC, 1:500) was purchased from ImmunoReagents, Inc. (Shanghai, China). Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) (A-21428, 1:500) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 555, was purchased from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY). Hoechst 33258 Stain solution (C0021, 1:500) and PMSF (100 mM) (P0100) were purchased from Solarbio (Beijing, China). Anti-c-Myc magnetic beads (HY-K0206) were obtained from MedChemExpress (Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA). Anti-FLAG® M2 magnetic beads (M8823) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Plasmids construction and transfection

Standard molecular biology procedures were used for the construction of all plasmids. All expression vectors were constructed by homologous recombination using ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China, C112-01). The mutants were constructed by PCR-based site-directed or deletion mutagenesis using 2× Hieff Canace® PCR Master Mix (Yeasen, Shanghai, China, 10136ES08). The full-length cDNA encoding NEIL1 (AB079068.1) from A549 cloned into pCDNA3.1-Myc-His, pCDNA3.1-Flag-His and pCDNA3.1-HA-His. Viral genes were amplified from the lAV genomes by RT-PCR and were cloned into pCDNA3.1-Myc-His, pCDNA3.1-Flag-His, and pCDNA3.1-HA-His. PB2, PB1, PA and NP-H1N1 were cloned from A/PuertoRico/8/34 (PR8), NP-BVR-26 were cloned from B/Austria/1359417/2021 (BVR-26). The cDNA encoding NP-H5N1 (AB212055.1) and NP-H7N9 (KJ476634.1) were synthesized from Tsingke Biotechnology (Beijing, China). The 2000 bp promoter region in front of the IFN-β CDS region from human A549 cells was cloned into the pcDNA4/TO, followed by the insertion of the mCherry-tagged marker. RIG-I, MAVS, TBK1, p65, IRF3-5D and IRF7 cDNAs were cloned into pcDNA3.1-Flag vector. pRL-TK and IFN-β–luciferase reporter plasmids were purchased from Beyotime. Primer sequences used for cloning are available upon request. According to the manufacturer’s recommendations for transient expression, all constructs were verified by DNA sequencing and were transfected into cells using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, L3000075) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Generation of stable human A549 cell lines conditionally expressing IFN-β-promoter-mCherry

For transfection of the pcDNA4/TO-IFN-β-promoter-mCherry plasmid, A549 cells were seeded in a 10-cm dish. Once 80% confluency was reached, cells were co-transfected with 5 μg pcDNA4/TO-IFN-β-promoter-mCherry by using Lipofectamine 3000. Twenty-four hours later, 100 μg/mL zeocin (Invivogen, ant-zn-05, San Diego, USA) was added to the medium to screen for clones resistant to zeocin. After incubating cells for 10 days, the surviving cells were continued to be cultured with zeocin-resistant media. The stability of the overexpressing cell line was verified by stimulation with H1N1.

Establishment of EmCKO-screen knockout cell lines

A lentivirus epigenetic modification library used for EmCKO-screen (a genome-wide epigenetic modification enzyme knockout screening based on Lentivirus packaging CRISPR-Cas9) was conserved for our laboratory, which contained 5649 unique sgRNAs targeting 1041 human epigenetic modifiers (sequences used for cloning are available upon request) and focused on eighteen domains, including promoter activity, enhancer function, DNA methylation, imprinting, DNA repair, histone variant exchange, etc.

The epigenetic modification library was co-transfected into HEK293T cells with packaging vectors pMD2G and psPAX2. Two days after transfection, the viral supernatant was harvested, the viral titers were determined and stored at −80 °C. A549 cell lines expressing IFN-β-promoter-mCherry were incubated with lentivirus supernatant (8 MOI) containing 8 mg/mL polybrene for 48 h and selected with 1 µg/mL puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA) to generate a stable cell line and eventually amplified into 10-cm dishes, Subsequently, surviving cells were used for high-throughput screening.

High-throughput screening

Cells were harvested using a BD FACSAri flow sorter (BD Bioscience, USA) after being infected with or without PR8 (1 MOI) for 24 h. Genomic DNA (gDNA) of the sorted positive and negative cells was extracted with a DNA isolation kit (Tiangen Biotechnology, China) for whole-genome sequencing.

RNA interference

A549 cells were transfected with small interfering RNA (siNEIL1-1 and siNEIL1-2) using Lipofectamine 3000. All siRNAs are synthesized from GenePharma (Shanghai, China). The knockdown efficiency was confirmed by qPCR and western blotting. Their sequences are as follows: NC (nontargeting) siRNA, 5’-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTTT-3’; siNEIL1-1, 5’-GGGCGCAAGTCCCGCAAAA-3’; siNEIL1-2, 5’-GCTCCCACAGTGCCCAAGATT-3’.

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, total RNA from indicated cells that different treatments were purified using TRIzol Reagent (TaKaRa, Otsu, Shiga, Japan, 9109) and reversed transcribed into cDNA by Hifair® III 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (gDNA digester plus) (Yeasen Biotech, Shanghai, China, 11139ES60). cRNAtag RT, vRNAtag RT, and mRNAtag RT primers were used for reverse transcription of vRNA, cRNA, and mRNA of NP, respectively70. Oligo dT and random primers were used for detecting host genes. The relative qPCR was performed with Hieff® qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Low Rox Plus) (Yeasen Biotech, Shanghai, China, 11202ES08). Applied Biosystems 7500 was used for numerical determination and cDNA quantities were normalized to the β-actin. qPCR primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Western blotting and co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays

Samples were prepared and treated as described above, and cell monolayers were washed with cold PBS and lysed in 400 µl lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, 10% glycerol) containing protease inhibitor cocktail and 1 mM PMSF on ice for 15 min. The protein concentrations were determined by the BCA analysis kit. Protein fractions were used to load an SDS-PAGE gel to perform immunoblotting. The co-lP assay was conducted as previously described with minor modifications71. Briefly, HEK293T cells transfected alone, co-transfected with indicated plasmids, or infected with IAV were lysed with NP-40 lysis buffer after 24 h.

Then the cell lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min. In all, 50 µL supernatant were taken out in a new tube, added 5× protein loading buffer and boiled to make input samples. Subsequently, the rest of the supernatants were incubated with Flag/Myc magnetic beads at 4 °C for 3 h with gentle rotation. The beads were washed with NP-40 lysis buffer five times and boiled in 5× protein loading buffer for 10 min. The samples were then subjected to western blotting assay.

ELISA

The contents of IFN-β in cell supernatants from indicated cells were measured using a human IFN-β ELISA kit (Shanghai Enzyme-linked Biotechnology Co., Ltd. ml027494) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The culture supernatants were harvested and stored at −80 °C until analyzed by ELISA.

Confocal immunofluorescence assay

Hela cells were seeded in 12-well plates (Cellvis, P12-1.5H-N), until the cell density was 40–50%. Depending on the specific experiment, Hela cells were inoculated with IAV or transfected with the plasmid expressing NEIL1, NP, and empty vector. Treated cells in culture plates were first fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature and then permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 min. Then cells were washed three times and blocked with 5% BSA at 37 °C for 1 h before incubating overnight at 4 °C with the indicated primary antibody. Next, cells were rinsed three times with PBST (1× PBS and 0.1% Tween 20) and then incubated with fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies combined with Hoechst for 1 h in the dark. Finally, images were obtained with a Leica SP8 confocal microscope and analyzed using LAS X Software (V3.7.4). Nucleus and cytoplasmic NP proteins were detected and calculated for each group using the high-connotation imaging system (Opera Phenix®; Perkin Elmer) to further analyze the nucleoplasmic ratios of influenza viruses after different treatments.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

At 24 h after transfection, cells were lysed and analyzed by the luciferase assay. HEK293T cells were transfected with a mixture of luciferase reporter(IFN-β-Luc), pRL-TK (Renilla luciferase plasmid), together with indicated plasmids. After 24 h, the cells were treated with VSV∆51, poly (l:C), H1N1, MAVS, TBK1, p65, IRF3-5D, or IRF7 for another 12 h. The cells were lysed with lysis buffer, and the luciferase activity in the lysates was determined with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Yeasen, 11402ES60, Shanghai, China). The Renilla luciferase construct pRL-TK was simultaneously transfected as an internal control. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Nuclear-cytoplasmic fractionation

A549 expressing vector and NEIL1 cells were infected with PR8 (1 MOI) for 90 min or 6 h. The nucleocytoplasmic fractionation assay was conducted as previously described72. Cells were washed in ice-cold PBS and collected by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 5 min. Then, the nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins of A549 cells were separated using a nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extraction kit (Beyotime, China) and subjected to western blotting analysis to identify the nucleoplasmic distribution.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses and graphs were performed using GraphPad Prism software V9.5.0. Data are presented as the mean +SD unless otherwise indicated. Differences between experimental and control groups were determined by the Student’s t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). For all tests, differences between groups were considered significant when the P value was <0.05(*), <0.01(**), <0.001(***), and <0.0001(****). Ns: no significant difference.

Responses