Neoadjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors for hepatocellular carcinoma

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for over 80% of all primary liver cancers and is the fourth leading cause of cancer death worldwide1. HCC’s rise in recent years may be driven by the rise in alcohol use, obesity, and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)/metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH). Approaches to HCC treatment remain challenging as many patients are diagnosed at advanced stages or with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) Staging System stage C disease (that is, with portal vein invasion, distant metastases, and/or an ECOG performance status of 1–2). Many of those with intermediate-stage HCC who are ineligible for, or have disease progression after, locoregional therapies are candidates for systemic therapies but not for curative local treatments, including percutaneous ablation, resection, or transplantation2. In patients diagnosed with early-stage disease, surgical resection has served as the mainstay curative treatment to achieve remission. However, recurrence rates remain as high as 70% within 5 years of surgery3,4. Curative surgical resection outcomes depend on multiple factors, including tumor stage and pathological features such as microvascular invasion and undetectable micrometastatis at the time of resection4,5. The 5-year survival rate is better in early-stage (75%) than intermediate or advanced stage (35%) cases.

There is growing evidence suggesting the use of adjuvant therapy, but neoadjuvant therapy is less explored6. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are emerging as a promising treatment option for HCC, particularly in the neoadjuvant setting. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy can be used to downstage solid tumors, converting locally advanced HCC into resectable disease, and to reduce recurrence by eliminating micrometastatic burden. This paper provides an overview of the current landscape of immunotherapy in the neoadjuvant setting for HCC, highlighting recent advances and ongoing clinical trials.

Neoadjuvant versus adjuvant immunotherapy in HCC

The efficacy of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in the first-line treatment of HCC has prompted researchers to investigate the efficacy and safety of this combination in HCC. The IMBrave 050 trial was designed to assess the efficacy and safety of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab compared to active surveillance in high-risk HCC after curative surgery6. The final analysis of the IMBrave 050 trial revealed that adjuvant atezolizumab plus bevacizumab did not result in improved relapse-free survival (RFS) or overall survival (OS) when compared to active surveillance in high-risk HCC7. A similar outcome was observed in the STORM trial, which failed to demonstrate the efficacy of Sorafenib in the adjuvant setting8. These findings underscore the absence of a proven, prospective, evaluated adjuvant therapy for HCC. The relative ineffectiveness of adjuvant therapy in comparison with the potential benefit of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in HCC remains unclear; however, it can be hypothesized that the presence of a functioning tumor might increase antigen release, which could in turn result in enhanced immunotherapy activity with regard to the elimination of micrometastases. Supporting data for this hypothesis has been found in preclinical models and some prospective trials for different types of solid tumors9. Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis revealed that the incorporation of adjuvant immunotherapy into neoadjuvant immunotherapy in resectable non-small cell lung cancer did not demonstrate enhanced event-free survival (EFS) or OS10. Some researchers hypothesize that micrometastases, which have been observed during both neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment periods, are less immunogenic compared to the primary tumor. This suggests that the timing of the administration of immunotherapy, prior to surgery, may influence T-cell expansion and efficacy in eradicating micrometastases. Therefore, we focus on neoadjuvant immunotherapy approaches in HCC along with pathological, immunological, and biomarker characteristics in this review.

ICIs

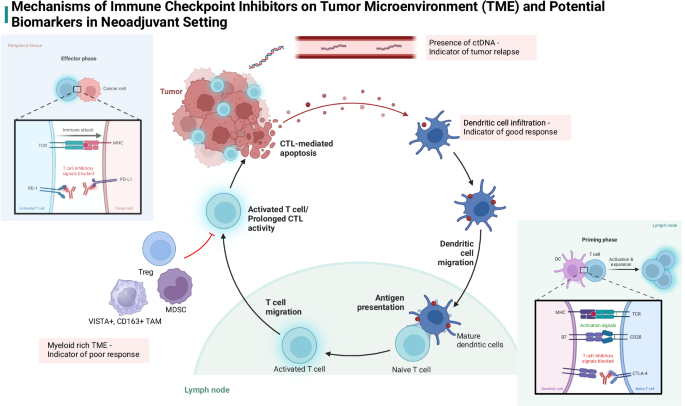

Sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor, was the first systemic therapy approved for HCC and has remained the first-line treatment in advanced HCC for many years. However, response rates in sorafenib are <10%, leading to increased interest in alternative systemic therapies11. ICIs with monoclonal antibodies against programmed death-1/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) inhibitors have gained more attention in the treatment of HCC. The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway acts by attenuating the CTL response, while CTLA-4 downregulates tumor antigen-presenting cells and regulatory T-cell (Treg) enhancement (Fig. 1).

Tumor microenvironments (TME) rich in T-cells and dendritic cells potentiate effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), creating a more robust treatment response. CTLA-4 inhibitors act on the priming phase of T-cell activation while PD-1 inhibitors prevent destruction of activated T-cells. Tumors rich in myeloid-derived suppressor cells have poor response to ICIs. Created in BioRender. Akula, V. (2025) https://BioRender.com/u85l726.

These checkpoint inhibitors were first studied in advanced HCC in the CheckMate and Keynote trials, showing improved clinical outcomes and favorable side effect profiles12,13,14,15,16,17. Reproducible evidence of disease modulation with these therapies has prompted their expanded use in earlier disease stages, particularly in the neoadjuvant setting. Immunotherapy has shown promising results in this setting in early-stage melanoma, early-stage mismatch repair-deficient colon cancer, and bladder cancer, with major pathologic response (MPR) leading to improved survival outcomes in the post-operative period9,18,19,20,21. Early studies of ICIs in the neoadjuvant setting in HCC have also shown promising results, both in monotherapy and combination trials. Neoadjuvant clinical trials provide a unique opportunity to improve patient outcomes in localized and advanced HCC while also allowing us to understand how these therapies work at a pathological level to inform which biomarkers can help identify optimal therapies.

Single-agent therapy

Previously published retrospective cohort studies and case reports have highlighted that neoadjuvant monotherapy with ICIs can reduce both recurrence rates and mortality after surgery, and help patients achieve complete response (CR) or partial response (PR)22. These study results have led investigators to initiate clinical trials to provide stronger evidence for the efficacy and safety of monotherapy with immunotherapeutic agents for neoadjuvant HCC treatment (Tables 1 and 2).

Kaseb et al. conducted a pilot randomized phase 2 trial to evaluate the benefit of neoadjuvant nivolumab in potentially resectable HCC23. Patients were randomized to neoadjuvant treatment with PD-1-targeted monoclonal antibody nivolumab monotherapy or were treated concurrently with the CTLA-4-targeted antibody ipilimumab. The primary endpoints were safety and tolerability, and the secondary endpoint was overall response rate (ORR). Neoadjuvant nivolumab with or without ipilimumab was generally well tolerated with similar pathological response in monotherapy vs. combination therapy (3/9 patients vs. 3/11 patients demonstrating MPR, respectively). However, monotherapy with nivolumab alone showed a better side effect profile (23% with grade 3-4 treatment-related adverse events [TRAEs] vs. 43%). In total, 5 patients were noted to have pCR with 1 who had an MPR ( > 70% necrosis). The pathology of these patients was also associated with a brisk T-cell response.

The patient who experienced MPR did not have a recurrence after median follow-up of 26.8 months. Notably, the recurrence-free survival differed significantly between patients with and without an MPR. Patients treated with neoadjuvant immune checkpoint therapy can achieve MPR with longer recurrence-free survival.

In another clinical trial designed to investigate immunological monotherapy, Marron et al. showed pathological responses in patients with resectable HCC receiving neoadjuvant cemiplimab, an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody. Seven of the 20 patients studied had 50% or greater tumor necrosis, including 3 who had complete tumor necrosis at histopathology24. Importantly, analysis of post-treatment lesions showed increased numbers of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in patients with 50% or greater necrosis compared to those with less than 50% necrosis, with higher CD8 T-cell infiltration in the tumor compared with surrounding tissue24.

Standard therapy for recurrent resectable HCC (rHCC) is repeated hepatectomy; however, recurrence rates are higher than that of primary HCC. Chen et al. explore the role of neoadjuvant immunotherapy with tislelizumab, a PD-1 inhibitor, in recurrent HCC in the phase 2 TALENT trial. Of the 11 patients enrolled, 4 experienced AEs (none were severe). ORR was 18.2% (2/11), with 1 achieving CR and 1 achieving PR; 1 patient experienced disease progression. Two patients had an MPR: 1 with CR and 1 with a > 85% response. Ultimately, 2 patients developed recurrence at 1 year. This trial demonstrates the safety and modest efficacy of neoadjuvant tislelizumab for rHCC patients25.

From these trials, it is evident that anti-PD-1 monotherapy has satisfactory response and safety results, and in some cases provides pCR. Parekh et al. supported the superiority of anti-PD-1 therapy over other options in the neoadjuvant treatment of HCC patients in a meta-analysis. The meta-analysis included 5 phase 1/2 studies with 96 patients. The analysis showed that adding tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy does not improve pathological outcomes or ORR. Further, there was no difference in pCR rates between single anti-PD-1 therapy vs. combination treatment with anti-CTLA-4 immunotherapy26. These clinical trials also further underline the role of CD8 T-cell response in the efficacy of immunological therapies and show how pathological response influences overall clinical outcomes to help guide therapy choices. It is evident that neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 monotherapy can improve survival outcomes in these patients.

Combination therapy

ICIs may also be used in combination with more traditional systemic chemotherapies, such as TKIs; other chemotherapeutic agents, such as platinum-based therapies, purine/pyrimidine analogs, and antimetabolites; and local treatment modalities. This approach aims to leverage the synergistic effects of immunotherapy, targeted therapy, traditional chemotherapy, and local treatments targeting both immune evasion and tumor proliferation pathways. Various clinical trials have been initiated to determine the efficacy of these combinations27.

ICI combinations

PRIME-HCC was a phase 1b clinical trial that aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of combination ipilimumab and nivolumab as neoadjuvant therapy prior to liver resection in patients with early-stage HCC28. The primary objective of the study was to evaluate the safety of combination therapy, while secondary objectives included assessing the response rate, progression-free survival (PFS), and OS. The PRIME-HCC study’s updated data was presented as an abstract at the 2023 ASCO meeting. The data included 25 patients, 21 of whom were assessed for radiological response and underwent surgery. The ORR was 29% (6/21). MPR was observed in 56% (9/16) of evaluable patients. Further, pCR was observed in 38% (6/16) of evaluable patients. The combination was tolerated well with 24% experiencing grade ≥3 AEs. Moreover, the data showed that gut microbiota and immune infiltrate composition can be predictors of the antitumor efficacy of combination ipilimumab and nivolumab28. Although the study is ongoing, interim analysis shows promising efficacy results, warranting further investigation in larger randomized trials.

ICIs with other systemic treatments

A phase 1B study of cabozantinib and nivolumab was conducted for unresectable locally advanced HCC. Combination therapy enabled resection for 12/15 patients, with only 1 patient showing pCR. Additionally, 4 patients had an MPR29. The trial design included 2 weeks of cabozantinib monotherapy, which allowed the authors to examine its effects alone vs. its combination with nivolumab. In samples taken after 2 weeks of cabozantinib monotherapy, the authors observed a 1.5- to 2-fold increase in abundance of both effector and memory T cell subtypes in both CD4+ and CD8 + T-cell populations. Treatment with cabozantinib promoted T-cell differentiation into more pro-immune phenotypes. Analysis of the tumor microenvironment (TME) of samples treated with both cabozantinib and nivolumab showed enriched effector T cells, tertiary lymphoid structures (TLSs), and CD138+ plasma cells, as well as distinct organization of B cells in the responders. This highlights the possibility of synergy between different mechanisms of immune activation in combination therapy.

Lenvatinib has also been studied in combination with toripalimab, another anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody, for surgically resectable HCC in an ongoing phase 1B/2 trial comparing this combination to toripalimab alone30. The primary endpoint was pathological response, and secondary endpoints included safety/tolerability, ORR, disease control rate (DCR), time to operation, and PFS. Of the 18 patients who were enrolled, 16 (88.9%) proceeded with surgical resection as planned. No visible tumor was observed in 1 patient following resection, although the treatment group was not specified. Three patients (20%) experienced an MPR (defined as residual tumor present in <50% of the tumor bed), 2 with monotherapy and 1 with combination therapy. Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis showed an increase in T-cell infiltration in responder tissue compared to non-responder tissue. Grade 3 or higher AEs occurred in 3/18 patients (17%).

In a phase 2 study that enrolled 24 patients, tislelizumab plus lenvatinib was evaluated. The ORR was 54% (13/24). The pCR and MPR were 17.6% (3/17) and 35.3%(6/17), respectively. In addition, 3 patients (13%) had significant tumor shrinkage and refused surgery. No grade ≥3 AEs were observed31.

Anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in combination with vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) TKIs is also currently under investigation as neoadjuvant therapy for HCC. In their single-arm phase 2 clinical trial, Xia et al. enrolled 18 patients with resectable HCC to receive perioperative administration of camrelizumab along with apatinib followed by surgery32. Primary outcomes assessed included MPR, pCR, objective response rate, RFS, and AEs. TMEs were also evaluated following resection. Of the 18 patients who completed neoadjuvant therapy, 3 (16.7%) and 6 (33.3%) patients achieved ORR based on Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) v1.1 and modified RECIST (mRECIST) criteria, respectively. Of the 17 patients who received surgery, 3 (18%) achieved MPR and 1 (6%) achieved pCR. At 1 year, the RFS rate was 53.85%. Grade 3/4 AEs were reported in 3 (17.6%) patients, including rash, hypertension, drug-induced liver injury, and neutropenia in the preoperative phase. TME analysis showed increased dendritic cell infiltration in responders compared to non-responders. Furthermore, patients with circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) after therapy were found to have shorter time to relapse compared to those with no ctDNA. This trial provided further evidence of the efficacy of neoadjuvant combination immunotherapy for resectable HCC and additional insight into possible biomarkers to predict response and relapse. This combination has also been studied with regard to the timing of administration. At the time of publication of their abstract, Bai et al. had enrolled 24 patients in their randomized controlled trial to study perioperative versus postoperative administration of camrelizumab along with apatinib to treat resectable HCC33. Sixty patients were included in the perioperative cohort. Fifty-two of these patients had completed 2 cycles of neoadjuvant therapy, with 24 (46%) achieving MPR. They reported an R0 resection rate of 100% in this group. Nineteen percent of patients experienced grade ≥ 3 TRAEs, the most common of which were increased aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (5.3%), hypertension (5.3%), and increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (3.5%)34. The phase 3 stage of the study is currently ongoing (Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT04521153).

Cui et al. conducted a phase 2 study to evaluate the role of perioperative cemrelizumab plus apatinib in patients with HCC. The data included 26 patients who underwent hepatic resection with a 100% R0 resection rate. The MPR and pCR were 38.5% and 7.7%, respectively. Grade 4 AEs were reported in 7/31 patients (22%); the most common TRAEs were increased AST/ALT, and decreased platelet, hemoglobin, and lymphocyte counts35.

Combination sintilimab (anti-PD-1) and bevacizumab (anti-VEGF) have also shown improved PFS and OS compared to sorafenib when used to treat unresectable and advanced HCC in the ORIENT-32 trial36. It was therefore approved as a first-line treatment for unresectable HCC. Sun et al. assessed the efficacy of this combination as conversion therapy in patients with potentially resectable disease37. In their study, 17 patients with BCLC stage B HCC met the criteria for hepatectomy after treatment with sintilimab/bevacizumab. At the time of their abstract’s publication, 2 patients had pCRs. Median EFS was 13.8 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 10.3-17.3), and the 6-month and 12-month EFS rates were 76% and 60%, respectively. Grade 3 TRAEs occurred in 7 (23.3 %) patients. Nine serious AEs occurred, and 3 of them were treatment associated37.

ICIs with local treatment modalities

Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) in combination with systemic therapy (immunotherapy plus TKI) is being investigated by Zang et al.38. In their clinical trial, 36 patients received camrelizumab, lenvatinib, and HAIC with raltitrexed plus oxaliplatin (RALOX), with the primary endpoint of objective response rate. Patients were followed for a median of 14.2 months, and ORR was found to be 61.1%% and 83.3% per RECIST v1.1 and mRECIST, respectively. Four (11.1%) patients experienced complete radiological response, and grade 3-4 TRAEs occurred in 75% of patients. TRAEs included thrombocytopenia, elevated AST, and leukopenia. No treatment-related deaths were reported38.

The efficacy and safety of the combination of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) plus camrelizumab in the neoadjuvant setting for patients with intermediate-stage HCC, according to China Liver Cancer (CNLC) staging, have been evaluated in a prospective study conducted by Hou et al.39. Patients were treated with TACE plus camrelizumab sequentially, followed by liver resection. The rate of successful downstaging was 63.6%, and CR and ORR rates of 18.2% and 100%, respectively, were observed according to mRECIST. In terms of survival, the 1-year RFS and OS were 77.9% and 80%, respectively. While RFS survival was statistically significantly longer in patients who were downstaged compared to those who were not, OS did not reach statistical significance. There were no deaths or severe TRAEs.

A recent phase 2 study investigated the use of preoperative drug-eluting sintilimab plus TACE in patients with HCC at BCLC stage A exceeding the Milan criteria or BCLC stage B who were ineligible for surgical resection. The primary endpoint was PFS by mRECIST, and secondary endpoints included objective response rate, pathologic response rate, and safety. The objective response rate was 62%, and 51 patients underwent surgery. After a median follow-up of 26.0 months, the median PFS was 30.5 months, and the 12-month PFS rate was 76%. A pCR was achieved in 14% of patients who underwent surgery. The study found that sintilimab plus drug-eluting bead TACE (DEB-TACE) before surgery showed good efficacy and safety in patients with HCC at BCLC stage A exceeding the Milan criteria or BCLC stage B40.

Another retrospective study reported the outcomes of 69 patients with a high risk of recurrence who had received neoadjuvant triple therapy combining TACE with lenvatinib, and an anti-PD-1 agent (sintilimab, camrelizumab, tislelizumab, pembrolizumab, or toripalimab) prior to liver resection, compared to those who underwent surgery alone. Triple therapy resulted in a statistically significant increase in OS and disease-free survival at both 12 and 24 months (100% vs. 73.7% and 85.7% vs. 48.7%, respectively), as well as an ORR of 83.3%, with CR seen in 8 patients. No deaths or severe TRAEs were reported41.

In conclusion, the combination of ICIs with traditional systemic chemotherapies and locoregional therapy (TACE) and other targeted therapies such as TKI holds great promise in the oncology field. Clinical trials exploring these combinations have demonstrated encouraging results in HCC. The synergistic effects of immunotherapy, targeted therapy, and chemotherapy have been observed, targeting both immune evasion and tumor proliferation pathways. These combinations have shown improved outcomes such as increased resection rates, pCRs, and prolonged RFS. Moreover, TME and biomarker analysis has provided insights into potential response and relapse predictors. However, it is important to note that AEs have been reported, underscoring the need for careful monitoring and management of treatment-related toxicities. Further research and ongoing clinical trials will continue to refine and validate these combination approaches, offering new possibilities for future enhanced cancer treatment strategies.

Neoadjuvant cancer vaccine

Although cancer vaccines have been studied for a long time as a treatment option for solid tumors, there is limited data demonstrating sufficient efficacy to warrant a change in clinical practice42. A recent phase 1 study aimed to investigate the efficacy and safety of a vaccine consisting of multi-human leukocyte antigen-binding heat shock protein 70/glypican-3 peptides with a novel adjuvant combination of hLAG-3Ig and poly-ICLC as a perioperative treatment for surgically resectable HCC43. The vaccine was administrated intradermally 6 times before surgery and 10 times after surgery. Of 20 patients enrolled the study, 12 patients’ pathology showed the presence of CD8+ T lymphocytes with target antigen expression. This study demonstrates the safety and potential of novel vaccines as a potentiating agent for immunotherapies.

Mechanisms of immune response

These clinical trials have not only provided evidence of the safety and efficacy of these therapies, but also have elucidated the mechanisms by which immunotherapies confer pathological response. Patients with resectable HCC who have an MPR following treatment with immune checkpoint therapies have been shown to possess favorable TMEs. In contrast, TMEs that are myeloid-rich have been linked to immunosuppression and poor pathological response23. Ho et al. observed enhanced B-cell infiltration, plasma cell infiltration, and TLSs consisting of B cells and T cells in the pathologic responders, suggestive of organized B-cell contribution to antitumor immunity29. IHC analysis in the Kaseb et al. study showed an increase in the percentage of TILs after treatment in patients who experienced MPR23. Post-treatment cytometry by time of flight (CyTOF) tissue analysis of patients with MPR showed an increase in activated effector T-cell clusters, which is known to be essential in T-cell-mediated antitumor immune response. These prospective clinical trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant ICIs for resectable HCC show promising results in reducing the recurrence rate and mortality after surgery by achieving MPR.

Pathological assessment of HCC after neo-adjuvant immunotherapy

RECIST is the gold standard method for measuring therapy response in solid tumors using imaging techniques. In 2009, mRECIST was developed due to the limitations of RECIST for HCC44. However, due to the unique response mechanisms demonstrated by immune-based therapies45, immunotherapy RECIST (iRECIST) criteria were developed to evaluate responses to immunotherapeutics46. Even though the RECIST criteria were designed primarily to standardize clinical trials, not to guide treatment or clinical decisions46, they have been widely studied for the correlation of treatment response and prognosis with contradicting results. Some studies showed that RECIST criteria results are not correlated with therapy response and prognosis47. Additionally, some studies reported that pathological responses after immunotherapy align better with patient survival than RECIST criteria48. While the best method to assess immunotherapy response remains undetermined49, a consistent approach for the pathological assessment of HCC specimens after neoadjuvant therapy is crucial to provide a clearer picture of therapy effects and patient outcomes. This might also provide deeper insights into therapy-induced histopathological changes and response patterns, providing potential new biomarkers for treatment response.

The guidelines from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) lack uniform sampling protocols for the evaluation of HCC resection specimens. On the other hand, Chinese pathological societies have introduced a 7-point sampling method, which has since been widely adopted and refined within China50,51. This method consists of sampling from 7 different regions of the specimen, including a minimum of 4 sections from tumor margins along with adjacent liver tissue, at least 1 section from the core of the tumor for molecular analysis, and 1 section each from the adjacent ( ≤ 1 cm) and distant ( > 1 cm) peritumoral regions. Standardized sampling methods after neoadjuvant immunotherapy exist for other cancers, including breast, lung, pancreatic, gastrointestinal tumors, and melanoma, but not for HCC. However, ambiguity remains for HCC specimens in this context52.

ICI therapy induces notable histopathological changes in both tumors and the liver. ICI-related histopathological changes in the liver do not show specific or pathognomonic findings and can overlap with other liver diseases. Therefore, clinical presentation, laboratory findings, and exclusion of other causes should be considered to confirm the diagnosis. ICI-related histopathological findings are variably reported in different studies including acute hepatitis with lobular inflammation, centrilobular necrosis, periportal activity, acute granulomatous hepatitis, or bile duct injuries53,54,55. The variety of these patterns might also depend on the ICI therapy agent used.

In a comprehensive review, Wang et al. highlighted the histological changes seen in HCC after neoadjuvant immunotherapy52. They identified different patterns of necrosis, including coagulative necrosis with or without retaining the original tumor structure, and liquefactive necrosis marked by neutrophilic infiltration. While the clinical relevance of these necrosis patterns post-ICI therapy remains unclear, one study indicated that HCC exhibiting liquefactive necrosis tends to have a poorer prognosis following TACE treatment56. Wang et al. also reported that the degenerated tumor cells can manifest in 2 ways: either as shrunken tumor cells with pyknotic nuclei with acidophilic cytoplasm or as enlarged tumor cells characterized by nuclear vacuolation and prominent nucleoli. Furthermore, intratumoral stroma can present different features such as fibrosis with inflammation, hemosiderin deposits, ductular reaction, hemorrhage, and foamy macrophages with cholesterol clefts. A recent study revealed that neoadjuvant immunotherapy also induces the formation of intratumoral TLSs57. The study also showed that high TLS density after neoadjuvant therapy is associated with a better pathologic response to immunotherapy treatment and an extended RFS. These findings align with several previous studies that found that the presence of intratumoral TLS indicates a more favorable prognosis29,58.

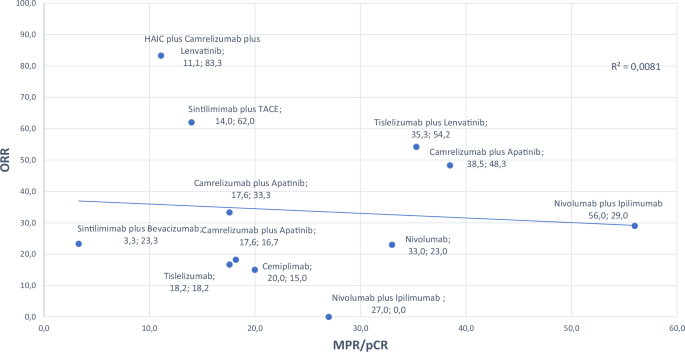

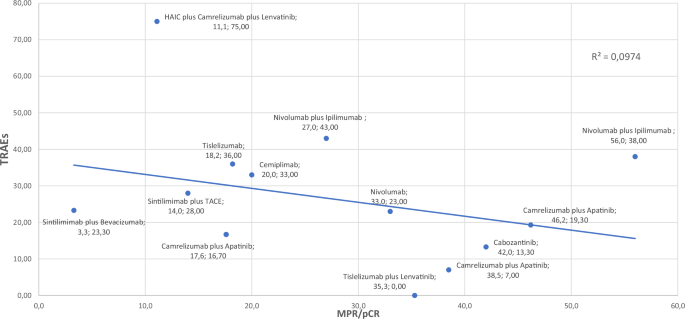

Tumor burden is the key parameter for measuring the pathological response rate in neoadjuvant therapies59,60. pCR and MPR are the 2 commonly used terms to describe the efficiency of therapy. MPR is generally perceived as indicative of a favorable prognosis, indicating the residual tumor cells are below a certain threshold. On the other hand, pCR indicates the absence of viable tumor cells after treatment. The thresholds for MPR vary among studies; while some use 70% as the cutoff, others use 90%61. Determining an optimal threshold is vital for accurate interpretation of study outcomes. Furthermore, although a limited number of studies have presented data on ORR and MPR/pCR, there was a negative correlation between MPR/pCR and ORR, which did not reach statistical significance in our analyses (Fig. 2 [P = 0.656]). Similarly, there was a negative correlation between MPR/pCR and TRAEs, which did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3 [P = 0.579]). In addition to MPR/pCR, a recent post-hoc analysis of IMBrave 150 proposed a new concept—ghost tumors—in patients who had durable response (PR or stable disease, SD) to first-line treatment with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab62. Ghost tumors were defined as radiologically persistent tumors that, upon histopathological examination, lack viable neoplastic cells. These tumors were particularly prevalent in patients with HCC who experienced durable PR to immunotherapy. The authors concluded that approximately half of the durable PR tumors in the real-world setting appeared to be ghost tumors. Histologically, ghost tumors often exhibit variable infiltration of innate immune cells, specifically histiocytes and macrophages, along with a notable presence of fibrous tissue and hyalinization necrosis. Interestingly, there was negligible infiltration of cytotoxic lymphocytes in these tumors. However, identifying ghost tumors through current imaging methods poses significant challenges because there is a marked discrepancy between radiologic and pathologic immunotherapy responses. This underscores the need for more advanced imaging technologies and biomarkers to accurately predict and identify ghost tumors in clinical practice. It is a necessity to perform comprehensive studies and establish standardized guidelines to address these uncertainties, including the methods for evaluating treatment response and consistent specimen sampling in HCC after neoadjuvant therapy.

MPR major pathological response, ORR objective response rate, TACE transarterial chemoembolization.

MPR major pathological response, TACE transarterial chemoembolization, TRAEs treatment related adverse events.

Biomarkers for neoadjuvant immunotherapy response in HCC

While immunotherapy has quickly advanced as a therapeutic option for HCC, it remains non-curative, and around 25% of patients experience grade 3-4 immune-related AEs12,13. It is thus imperative to identify reliable biomarkers that can predict clinical response to such treatments. Notable biomarkers derived from tumor tissues include PD-L1 expression, tissue-infiltrating lymphocytes, tumor mutational burden, and specific immune signatures. Additionally, peripheral blood markers—such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), ctDNA, circulating tumor cells, and immune mediators—along with gut microbiota profiles, have been studied in HCC research63.

Given the predilection for HCC diagnosis via imaging, validation of novel tissue-based biomarkers remains challenging. However, neoadjuvant trials offer a unique platform to investigate the dynamic effects of immunotherapy in vivo while also providing potential clinical advantages. Unlike the scarce biospecimens obtained from metastatic trials, neoadjuvant trials provide access to both pre-treatment and post-treatment (during resection) blood and tissue samples. This accessibility allows for a more detailed assessment of therapeutic impacts and facilitates the discovery of innovative biomarkers64. While neoadjuvant treatments are beneficial, they do carry potential drawbacks. AEs may delay or complicate surgical procedures or even result in tumor progression to an unresectable stage65. Hence, the urgency to develop biomarkers is evident.

Tissue-based biomarkers

Several tissue-specific biomarkers have been explored across various cancers for their potential to predict immunotherapy responsiveness. Among them, tumor PD(L)-1 expression is the most extensively studied in HCC, yet it has yielded inconsistent predictive outcomes63. Multiplex analyses of patients undergoing neoadjuvant treatments with nivolumab and ipilimumab revealed that responders had a significant baseline enrichment of peritumoral CD4+ and CD8+ cells in their tumor biopsies. In addition, there was a marked post-treatment decrease in intratumoral FOXP3 + /CD4+ Tregs within resection samples28. Other studies demonstrated the presence of enhanced dendritic cell infiltration in responders32 and identified myeloid cells, arginase-1-expressing CD163+ macrophages29, and VISTA+ macrophages23 as potential mediators of therapeutic resistance. Of note, in the neoadjuvant context, immunotherapy appears to amplify the response by augmenting tumor-infiltrating immune cells, potentially conferring benefits in early tumor control prior to metastasis23,29.

Growing evidence suggests that gut microbiota composition may modulate immunotherapy efficacy across a range of cancers, hinting at its potential as a predictive biomarker66. While studies on neoadjuvant nivolumab and ipilimumab indicated no significant microbial diversity between responders and non-responders, the genera Alistipes and Collinsella were found in higher proportions in the pre-treatment stool samples of non-responders28. This contrasts with other research linking these genera to positive immunotherapy outcomes in melanoma67.

Blood-based biomarkers

Blood-based biomarkers have gained increased attention because of their low cost, non-invasive nature, and ability to be dynamically monitored. Since a strong link has been established between inflammation and cancer progression, several studies have investigated the role of circulating blood components as potential prognostic and predictive biomarkers68,69. In a retrospective study70, high NLR and PLR have been shown to be associated with poor survival in patients with HCC treated with atezolizumab/bevacizumab. Low NLR has been associated with significantly longer PFS in patients with HCC receiving atezolizumab and bevacizumab, suggesting its potential use as a predictive marker71. A recent meta-analysis showed that elevated pretreatment neutrophil-to-eosinophil ratio (NER) levels were significantly associated with poorer OS and PFS across various cancer types including HCC68.

Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) is one of the most extensively studied biomarkers in HCC. Studies have suggested that dynamic changes in serum AFP levels could serve as a surrogate marker for treatment response. In the IMbrave150 study, a ≥ 75% reduction in AFP levels at 6 weeks demonstrated a sensitivity of 0.59 and specificity of 0.86 for identifying responders14. Another retrospective study showed that an AFP ratio of 1.4 or higher at 3 weeks might be an early predictor of refractoriness to atezolizumab plus bevacizumab therapy72.

Static tumor biopsies are prone to sampling bias, which may affect the accuracy of treatment response predictions. To accurately predict immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) response, capturing tumor heterogeneity is crucial, which is achievable through frequent liquid biopsies measuring markers such asctDNA during treatment and subsequent follow-ups73. Post-operative ctDNA presence was linked to disease recurrence in HCC patients treated with neoadjuvant cemiplimab74. ctDNA-positive patients exhibited a decreased recurrence-free survival compared to their ctDNA-negative counterparts. Remarkably, ctDNA facilitated the early identification of molecular relapse, nearly 5 months prior to detection by imaging74. A similar study on camrelizumab combined with lapatiniblapatinib in the neoadjuvant setting echoed these findings: ctDNA presence post-adjuvant therapy was indicative of diminished RFS32.

Research on biomarkers for neoadjuvant immunotherapy in HCC is still nascent. The pressing need for biomarkers capable of predicting both immunotherapy responses and treatment-associated toxicities, which could potentially delay surgery, remains evident.

Conclusion

Surgery is still the main treatment for patients with resectable HCC, while further exploration into the use of neoadjuvant strategies in HCC resection is still needed. Immunotherapy is an emerging systemic treatment for solid tumors. Targeted drugs plus ICIs can achieve a tumor response rate of 30%74 and provide important treatment options for neoadjuvant therapy. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy-based treatment prior to resection is feasible and is associated with high rates of pathologic responses and longer recurrence-free survival. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy has also been demonstrated to enhance antitumor immunity. Patients who are downstaged with systemic immunotherapies should be considered for resection. Larger randomized studies of neoadjuvant modern systemic therapy are warranted to determine whether this approach can improve HCC outcomes. The combination of immunotherapy and other treatments, such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, still require more evidence to demonstrate efficacy75. Furthermore, examination of the TME following therapy provides valuable insight into mechanisms of response and may provide explanations for disease persistence in non-responders. Biomarker identification through these clinical trials has also given providers new tools to predict response and possibly relapse. This paper provides an objective and comprehensive evaluation of existing studies to evaluate neoadjuvant monotherapy or combined immunotherapy before liver resection or transplantation to decrease the risk of recurrence and convert unresectable disease into resectable disease. Efficacy and safety evaluations of neoadjuvant ICIs for resectable HCC are ongoing and offer promising results for the future development of standard neoadjuvant systemic HCC treatment protocols.

Responses