New methods collection to identify the building and decoration stones provenance

Introduction

The investigation of historical building stones often involves the question of identifying the original material provenance. Archival research is not always sufficient; applicable sources are completely missing, especially for earlier periods. The aim of our research was to determine the provenance of the historic building stone using completely non-destructive methods. There are a number of methods for petrographic rock identification, determining its mineralogical or chemical composition, but matching a particular sample to its source locality poses a considerable problem. During our collaboration on research on historic objects, we have found that it is possible to combine different seemingly unrelated disciplines, humanities, natural sciences and engineering, to obtain much more accurate results. We have used this multidisciplinary approach in our case study aimed at determining the provenance of historic building stone using completely non-destructive methods.

There are a number of laboratory methods that are useful in determining the provenance of a historic stone. The choice of method is not always straightforward, and there is no single methodology to reliably assign a place of origin to a given petrographic rock type. In addition, in most cases a combination of several methods is used, e.g.1,2,3,4,5,6,7, the choice of which depends not only on the rock type, but also on the expertise of the researcher and his laboratory equipment. Petrographic analysis is the most widely used method and still has its place among modern analytical methods8,9, but, like other methods, it has its limitations. The determination of the provenance by petrographic analysis depends on the petrologist’s experience and is often complicated by the absence or incompleteness of databases with available petrographic data for comparison of the studied sample with the one considered. There are database systems around the world for the purpose of identifying the stone’s provenance, usually including other supporting geochemical data, as petrographic analysis alone is not sufficient, e.g.10,11,12.

The development of modern analytical methods allows detailed investigation of differences in the mineralogical or elemental composition of rocks. Most of the analytical methods used to identify the provenance of stones are destructive in nature. However, in the case of historic stone research, it is often not possible or desirable to allow the taking of a representative sample to carry out the necessary analyses. Dealing with this issue is often very complicated, and it is therefore necessary to focus on non-destructive in situ research methods. For example, spectroscopic methods, which can be both destructive and non-destructive, have great potential in research. Hopkinson et al.13 used, among other things, destructive visible and infrared spectroscopy to identify the building stone provenance. Based on the petrographic analysis of the rock sample from historical masonry and rock samples from quarries, they identified four possible limestone locations in a specific quarry and, comparing them to the spectroscopy results, they identified one stratigraphic horizon with the most resembling rock material. In conclusion, they refer to the high potential for the use of these modern research methods to determine the provenance and selection of the substitute building stone. Burg et al.14 provided evidence of the high potential for the use of the portable XRF spectrometry to specify the provenance of granites used in the production of Maya stone artefacts.

There are studies dealing with the analysis of building materials without special interest in historical stone using SWIR spectroscopy Fernández-Carrasco et al.15 explains how infrared spectroscopy is used in the analysis of building and construction materials such as cement and the influence of various additive materials. Ilehag et al.16 created a specific spectral library consisting of building materials where some sandstone samples are presented, but without specific information about the place of origin. Ferrer-Julia et al.17 uses VNIR-SWIR reflectance spectroscopy for the compositional determination of archaeological talc samples and Defrasne et al.18 studies hyperspectral imaging in rock art studies. In addition, among the geological applications of reflectance spectroscopy within remote sensing, we can mention the study of Chaudhuri et al.19, who, among others, used this method to characterise different fossils for the purpose of understanding the peleoecology and depositional history of the study area. The high potential of NIR spectroscopy for sandstone identification was demonstrated by Bowitz and Ehling20.

Each rock has specific properties, including optical qualities, reflecting its provenance and formation. Therefore, near- and mid-infrared spectrum reflectance spectroscopy (1000-2500 nm) was applied for the non-destructive identification of the stone provenance, as a very effective in situ tool. A unique spectral reflectance curve can be defined for each material and subsequently compared with the existing spectra in the pre-prepared spectra library that were measured on samples of active and former quarries, petrographic collections and lithoteques to find the one most resembling the investigated sample to determine the material. Within our research of historical building and decoration stones, this method, developed primarily for remote sensing, was applied experimentally during the investigation of historical masonry in St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague, Czech Republic.

For the purpose of our research, it was necessary to specify the age of the investigated stone elements. Refinement of the age of the stone elements helped us reduce the set of considered building stone sources to a specific historical period. Apart from art historical analyses of the building, a suitable tool for determining the age of a historic stone is traceological analysis of its surface21. Based on our previous research, we found a correlation between the type of stonemason tool used and the time when the stone element was crafted22. Finally, we improved the interpretation of the results on the basis of archival research. This comprehensive approach allowed us to determine the probable provenance of the stone used in a completely non-destructive way.

In the context of the use of a complex set of methods, art-historical and archival research is of great explanatory value. Art-historical analysis by means of a building-historical survey, together with a formal analysis of the building or its parts, helps to determine the sites or architectonical details on which the survey will be carried out. This is particularly important for architecture and interior furnishings of the medieval and early modern periods, whose original character has often been obscured by 19th-century alterations. If a spectroscopic analysis of the historic stone and a reference sample from the library can determine the possible origin of the stone in a particular quarry, the survey of archival materials will support and refine this finding. A database of spectra supported by art-historical and archival research thus becomes a relevant and relatively accurate source of information on the origin of the stone. The resulting database can thus be used even in cases where the source base that would tell about the original stone quarries in the Middle Ages and early modern period is very limited or completely missing.

Material and methods

Three criteria were set for the selection of materials for this application case study and for further research: (A) material relevance for the study goals, (B) the solution possibilities of art historical research specific issues, and (C) art historical and general contextual importance of the researched monument to strengthen the impact of the research results. A selection of artworks from the interior of St. Vitus Cathedral at Prague Castle and the structure itself were evaluated as ideal research material. The cathedral is one of the most prominent architectural monuments in the Czech milieu, broadly reflected in earlier and recent literature23,24,25,26, a spiritual centre of Czech statehood, and the necropolis of the Bohemian kings as well as the church and court elites. The most illustrious architects contributed to the cathedral’s erection, and the furnishings were commissioned from notable artists working for the royal court. St. Vitus Cathedral and its relics have earned the attention of experts in the Central European context as well. Nevertheless, an array of unanswered questions has remained despite the traditionally strong interest of researchers. This study deals with the exploration of the Wohlmut Choir masonry, investigating ten sandstone ashlars. First, the traceology analysis of the worked surface was conducted on all elements to determine their approximate age. Second, reflectance spectroscopy was applied on all stone elements to determine the provenance. Last, archival and literary research of available sources was carried out and achieved results were compared to discovered facts. The known place of the stone provenance, with great certainty, was the common denominator of the studied elements, in this case, based on the relatively provable visual petrographic analysis (e.g.27). To a limited extent, archival research contributed to the findings, see the section Brief History and Rock Types Used.

Brief history and rock types used

The present three-aisled Cathedral of Sts. Vitus, Wenceslas, Adalbert and the Virgin Mary (Fig. 1) is situated on the site of earlier sanctuaries, the pre-Romanesque St. Vitus Rotunda from c. 920s, later replaced by a Romanesque basilica built during the years 1060–1098. Regarding the material, the remains of these structures uncovered during archaeological research can be accessed only fragmentarily in a superposition under today’s structure whose construction began in 1344. The first architect was Matthias of Arras, born in France (perhaps Avignon). Following his death in 1352, an unknown master supervised the construction. In 1356, the young German architect Peter Parler from Schwabisch Gmünd assumed the work on the incomplete cathedral. After his death in 1399, and to some point perhaps even earlier, his sons and future builders took over the building lodge. The construction was halted, and the structure was partly damaged during the Hussite Era in the first half of the 15th century. Despite the efforts to continue the construction in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, it remained incomplete. The cathedral was severely damaged by the great fire of Prague Castle in 1541 and later, in 1757, by the Prussian bombing of Prague. Apart from the repairs of the damaged parts, the construction was focused on partial renovation. The Renaissance, Baroque, and 19th century were more considerably manifested in the interior furnishings, also strongly influenced by the iconoclasm under the Calvinist administration during 1619–1620. Following the renovation of the old part in the 1860s, the cathedral was only completed during 1873–1929, under the successive supervision of the architects Josef Kranner, Josef Mocker, and Kamil Hilbert.

St. Vitus Cathedral.

The Neo-Gothic western part next to the Great Tower was added during this period. The particularly complex and extended building development of the cathedral was further reflected in the material of the structure and related stone artworks. The use of specific materials depended not only on the time-changing preferences of the St. Vitus building lodge, architects, artists, and founders, but also on the logistic and financial possibilities of the material extraction from then operating localities. Following the first testing phase of research, one of the cathedral interior dominants was selected to clearly illustrate the material complexity and time changeability – a two-storeyed organ choir (Fig. 2) built by the German-born court architect Bonifac Wohlmut (1510–1579), a builder of the most significant Renaissance structures in Bohemia of the 1550–1570s who worked at the Prague court from 1556 to 1570. Dating from 1557–1561, the choir was built during the cathedral repair after the 1541 fire, and it fitted closely along the nave’s width to the interim western façade. The façade was torn down during the definitive completion of the cathedral in the 20th century when the new structure was joined with the old one.

Wholmut’s choir, 1557-1561, now situated in the northern arm of the transept of St. Vitus Cathedral.

In the years 1924–1925, the choir was dismantled and transposed, as well as rotated by 90°, to its current position into the northern arm of the transept (Fig. 3). It is a monumental two-storeyed Renaissance structure with a classicising order on the façade, yet with intentionally applied residues of the domestic building tradition manifested in the still principally Gothic interior vaulting. Such an architectural approach was rather common in Central Europe and was rated among plentifully used mannerist principles. In this case, the design was highly appreciated by the ruler Ferdinand I who had refused the purely Renaissance solution of the competing Italian architect Giovanni de Campione. The choir was renovated in the 18th century and during its transposition in the 1920s.

Wohlmut’s choir, 1557–1561, originally situated in the western part of St. Vitus Cathedral, photo from 1870.

The changed position of the choir and its various modifications had an impact on its material heterogeneity. The choir has not been submitted to modern building history nor restoration research – except for its Renaissance painting. Information about the material composition can only be drawn from visual petrographic analysis and a few written sources which, however, do not always provide any specific evidence27. Following the choir’s relocation, the original Hloubětín sandstone basis, substantiated in written reports28, was expanded by elements from the period favoured Mšeno sandstone. In addition to its availability and price, the technical properties (coarse graining) reducing the threat of silicosis posed to stonemasons played a significant role. Additionally, elements made of sandstone from Dvůr Králové and other materials, including reinforced concrete, were used29. Although some historical sources30 reveal orders for specific materials for specific parts of the cathedral, no records remained for the Wohlmut Choir. An available decoration stone database31, which served as a valuable source of information for the research project, provides a general picture of the types of rock used throughout the cathedral. Rybařík27 states Hořice sandstone had been used for the cathedral renovation since 1875, further specifying the sandstone from Hořice and Podhorní Újezd which was the only sandstone type used in the cathedral construction during 1893 and 1917. Further sandstone types, applied to various parts of the cathedral since the construction of the Wohlmut choir, include those of Boháňka, Kuks, Nehvizdy, Niedergrund (the Elbe), Nučice, and Žehrovice31. The material identification is slightly complicated by paintings and coatings of masonry from various periods, or the residues after their removal. Reflectance spectroscopy not only seeks to gain a more precise range of materials used for specific parts, but also to detail the use of a specific method in a hard-to-access research environment that will be transferrable to other cases of this type.

Applied traceology

The approximate age of the surveyed stone elements must at least be determined to verify our possible determination of the provenance. Studying the written and information sources e.g.31,32 disclosed that certain rock types began to be used only at a certain point, not throughout the entire cathedral construction. The approximate age of the stone ashlars was obtained from the analysis and identification of their surface working. Applied traceology was used for these purposes. This stage of research aimed to identify the surface originality. In our case, the goal was to differentiate the later renovation from the original 16th-century building stage. The applied methods included an examination of the tool traces, reconstruction of these tools, and indication of their practical use.

The tool marks examination utilises 3D sources and therefore requires a 3D model of the surveyed object, for which multi-image photogrammetry was used. The benefit of this method is seen in marking the object by the coordinates X, Y, Z instead of returning to the object repeatedly. The method lies in spatial analytical geometry using the selected coordinate system. First, the main points on the photographed object are focused on. These points are determined by trigonometric calculations in a polar coordinate system. The angle of elevation azimuth is acquired by the camera, where the software from the given point position on the reading device calculates both angles. The determination of the unknown position of the camera is consequently significant information. It can be calculated additionally by software when producing a continuous band of photographs with the minimum overlap of 50%. After acquiring all the required data, a finer structure made of a triangular network can be constructed from the basic point cloud. It is the basic approximation of the object’s shape. Subsequently, this network can be replaced by relevant cut-outs in the photograph33.

The 3D models of traces can be subjected to analysis that detects the dynamics of the strike, the dimensions of the grass or the volume of the cut-out material22. The previous survey revealed that each historical period is unique and shows an inimitable craftsmanship; therefore, the craftsman’s procedure allows one to determine the period of the identified ashlar origin21. Figure 4 shows an example of working and the identification of a craftsman’s treatment of the stone element no. 1. This surface area was first defined by a perimeter path and then aligned with a chisel with a wide straight edge (approx. 10 cm wide). The surface is aligned in irregular horizontal rows. This essentially rough style is typical for the 20th century22. The profile of the tool used is sketched in both longitudinal (a) and transverse (b) sections. The trace widens (white) due to the double repercussion of the chisel blade. Unlike the original surface finishing, which was also worked with a chisel about 5 cm wide, the final surface finishing was done by grinding. The working is thus only visible in fragments.

The stonemason first defined the area by a perimeter path (1) and later with a parallel irregular grid of rows (2); the profiling of the tool edge in longitudinal (a) and transverse (b) profiles.

Reflectance spectroscopy

The reflectance spectroscopy method was chosen to determine the provenance of the selected stone elements. Reflectance spectroscopy is, in general, a broad term involving the methods that study and record the interaction of electromagnetic radiation with matter. Clark34, for example, describes the principles of reflectance spectroscopy in more detail. Given that each material reflects and absorbs electromagnetic radiation differently depending on the changing chemical composition and texture, this method can help identify the physical and chemical properties of materials35. Specifically, Parish and Werra36 and Parish37 used this method to study archaeological sources.

Although the application of reflectance spectroscopy and hyperspectral imaging in remote sensing is standard, it is primarily used for the survey of mineral deposits38. For example, the United States Geological Service39 and NASA40 have databases with spectral reflectance curves of minerals, rocks, and other materials. These libraries primarily serve the analysis of the remote sensing data, but some (e.g. minerals) theoretically can be partly utilised for our purposes as well. However, the problem is that the libraries contain information about North American rocks and materials that can differ significantly from those of Central Europe. Therefore, the libraries must be used with caution, considering thoroughly the location of collecting the data for analyses.

There are possible software solutions for the spectral data analysis in the world, most of which are found in the existing software solutions for remote sensing. Nonetheless, these software solutions are unsuitable for the measured data processing because they lack the calculations of the diameter, the median for the multiple measurement of one sample, its statistical characteristics, etc.; moreover, they are largely used to process imaging data and their price is rather high. Currently, there is no user-friendly software solution for reflectance spectroscopy data analysis. In most cases, the data are processed by free script programmes e.g. R41 or custom programming languages e.g. Python42. Commercial programmes, e.g. Matlab43 can be used for customised solutions.

The non-invasive measurement of selected ashlars was performed with the OceanOptics NIR Quest 512 spectrometer (Fig. 5). The NIRQuest512-2, 5 from Ocean Optics/Ocean Insight44, works in the 900–2500 nm spectral range. In this range 512 spectral bands are detectable. The spectrometer is equipped with an InGaAs detector and cooling that is a necessity when using these detectors. Illumination of the object of interest is done by using fibre optics. An external illumination source Cool Red provides an adequate light source for the 900 – 2500 nm spectral range. An optic fibre then transfers the light into the scanning probe. A spectroscopic measuring device besides mentioned consists of a laptop with control software, fibre optics and a measuring probe. The probe is composed of an optical fibre, that transfers information into the spectrometer as well as fibres bringing illumination from an external source, the ferrule diameter is 3175 mm and an acceptance angle of 24,8°. The spectrometer probe has a diameter of 2 mm. All samples are measured at least 10 times at different locations. Each measurement consists of 10 measurements; this means that the final spectral reflectance curve is the average of 100 measurements. The averaging is done via the operating software. Outlying data are manually excluded within the measurements and data processing itself.

St. Vitus Cathedral – in situ material research using reflectance spectroscopy.

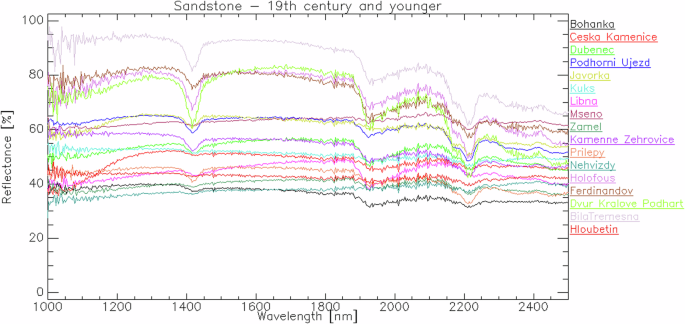

Two sets of spectral reflectance curves have been created to identify stone elements, representing sandstone samples available to us which can either be evidenced in Prague or at least reasonably assumed (Fig. 6). For the purpose of creating the spectra library, samples from the collections of the Department of Geotechnics of the Faculty of Civil Engineering CTU, the lithotheque of the Stone and Aggregate Test Lab in Hořice, the petrographic collections of the National Museum and from our own collections obtained during our field activities were measured. At the moment the library contains 49 reflectance spectra of Czech sandstones and 18 opokas. The acquired data was compared with the data from these libraries. The age of the stone elements was determined based on the traceological analysis (see the section Applied Traceology).

Spectral reflectance curves of selected Czech sandstones quarried from 19th century.

The analysis of the investigated samples uses mathematical algorithms to compare, in various ways, an ’unknown’ curve with those in the library to find the best congruence. The selection of the algorithm is crucial because of the high similarity of the sandstone curves in the library made by us (see Fig. 6). As it turns out, the Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM)45 is the best algorithm for our purposes because it calculates the spectral angle between two curves. It threats measured data as vector in a multi-dimensional space, where each dimension corresponds to a spectral band. The algorithm then calculates the angle between the vector and a vector of the reference spectra stored in the created spectral library. The smaller the angle, the more similar the curves are. The analyses were conducted in the Matlab and ENVI 5.6 programmes.

In the Short-Wave Infrared (SWIR) region (1000 – 2500 nm) sandstones exhibit several distinct spectral features that are primarily influenced by its mineral composition. These absorption bands are associated with the occurrence of various chemical bonds such as OH, H2O, Al-OH and Mg/FeOH, which are typical for the minerals commonly found in sandstones in different amounts. Absorption Al-OH band is around 2200 nm and is typically associated with clay minerals like kaolinite and illite. Absorption Mg/FeOH band is around 2300 nm and 2350 nm and indicates the presence of chlorite and/or serpentine. The possible presence of gypsum and anhydrite is demonstrated by the absorption band of SO42- around 2100 and 2200 nm. Finally, calcite and dolomite may be identified thanks to the CO32- absorption band around 2300 nm20,46,47.

For illustrative purposes, Fig. 7 shows the spectral reflectance curves of sample No. 8 and the Mšeno sandstone, assessed as the most similar using the SAM algorithm. In addition to quartz (90%), Mšeno sandstone is composed of a groundmass in which muscovite and illite are present. Occasionally limonite pigment is present48. The composition is in accordance with the measured spectra.

Spectral reflectance curves of Mšeno sandstone (blue) and smaple No. 8 (red).

Results and discussion

The age of stone elements

The surveyed stone elements were subjected to surface working traceological analysis based on which they can be divided into two groups: original 16th and 20th century elements. Sixteenth-century elements show a typical smooth surface without any indications of the initial working stage. The clean and smooth surface was made by perfectly grinding the facing area, most likely by a stone trowel. The stone elements worked in the 20th century feature facing areas fully levelled by a flat chisel (in this case c. 5 to 6 cm wide) in overlapping parallel lines. A circumferential line of about 1 cm shows through from the initial working stage. The previous stages remain illegible. An irregularity of parallel lines and overall re-smoothing of the facing area are typical signs of this period. The original stone elements that can be dated from the 16th century therefore include samples 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, and the central pilaster (Fig. 8). Samples 1, 4, 8, and the plinth (Figs. 9–10) date from the 20th century. Further detailed characteristics of the stone elements are found in the table below (Table 1).

Original worked ashlar typical for 16th century, central pilaster.

Worked ashlar typical for 19th century, sample 4.

Worked ashlar typical for 19th century, sample 8.

Stone elements provenance

Using the selected algorithm for data evaluation, the sandstone provenance of most of the surveyed elements, except sample 2, has been sufficiently identified, or the most likely provenance of the first three visually most similar rock types was determined. The results are shown in Tables 2,3, where the most similar rock types are marked and those that can still be considered based on visual similarities and archival research results. Furthermore, some in the first positions show a SAM value that is identical or very similar. The higher the SAM value, the greater the similarity of the samples. Value 1 corresponds to identical curves. The most likely place can subsequently be detailed by the results obtained by the traceological analysis, as well as archival and art historical research. This procedure enabled us to verify the applicability of the given method for the given purposes. The achieved results are discussed in detail below.

Based on the traceological analysis, the investigated central pilaster ashlar and samples 2, 3, 5, 6 and 7 were identified as authentic, i.e. dating from the Wohlmut Choir construction in the 16th century. The evaluation of the spectral reflectance curves and the analysis of archival and written sources suggests that the given stone elements were made of Hloubětín or Miletice sandstone (see Table 2).

Samples 1, 4, 8, and the plinth were dated to the 19th to the 20th century, and sandstones originating in Kuks, Boháňka, or Mšené-lázně seem to be the most likely (see Table 3). The stone elements standings are presented and commented on in the following.

Stone Elements Provenance, 16th Century

Based on research of written sources27,28, the central pilaster was made of Hloubětín sandstone which in our case turned out to be the most similar sandstone type. Since the ashlar can be identified as originally based on the traceological analysis, the results obtained can be verified.

With respect to the approximate traceological datation, sample 2 can be assumed to be made of sandstone originating in Kamenné Žehrovice, Přílepy, Prague – Bílá Hora, and sandstone from Miletice and Hloubětín. The first two types can be eliminated because of the clear visual difference from the examined stone element. Both types are arkosic sandstones of medium to coarse grain arkose. The sandstone from Prague – Bílá Hora cannot be fully excluded, nor can it be confirmed based on the study of written sources. With a maximum likelihood, the sandstone comes from Miletice. Although no records of its use in the construction of the Wohlmut Choir have remained, it is documented that architect Wohlmut used the same sandstone type for the construction of Queen Anne’s Summer Palace about the same time31 which is situated about 700 m from St. Vitus Cathedral. The summer palace was built in two stages starting in 153849. In 1541, after the Prague Castle fire, the elevation of the structure by one storey was considered. Bonifac Wohlmut contributed to this reconstruction which was conducted during 1554-1565. Using the same stone for the choir in St. Vitus Cathedral’s interior would thus support Wohlmut as the architect of the completion, which is sometimes questioned49. Similarly, the use of Hloubětín sandstone cannot be fully rejected either, although it shows a less convincing visual analogy. The standings of Miletice or Hloubětín sandstone on the 4th and 5th places regarding visual similarities can be explained by the residues of the surface working of the masonry that was ’marbled’ in the past (see Chapter 2.1)24. While the ashlar masonry surface was cleansed and marbling was removed in the past, some stone surfaces reveal that cleansing was rather ineffective and traces of marbling are still rather obvious. An incomplete database of spectral reflectance curves of sandstones used in the past is another possible reason for this ambiguous identification of stone ashlar. Naturally, this fact cannot be ignored; however, the residues of surface adjustments would be distorted even if the database was complete.

Based on dating, sample 3 can also be associated with the Miletice sandstone, which takes the 2nd place in the curve standings. The first sandstone from Kamenné Žehrovice can be excluded unequivocally because of its typical different appearance (see above). In the case of Kamenné Žehrovice, it is a coarse-grained arkosic sandstone to arkose with a higher amount of feldspars of Carboniferous age. This clearly distinguishes it from Cretaceous sandstones which include other sandstones under consideration31.

Sample 5 can be identified based on the spectral reflectance curve analysis as Hloubětín sandstone, showing the greatest visual similarity. Based on the surface traceological analysis, this stone element can be regarded as an original from the time of the Wohlmut Choir construction, just like the central pilaster. Moreover, both elements show great visual similarities (see Figs. 8 and 11).

Worked surface of sample 5.

For samples 6 and 7, the spectral reflectance curve analysis placed the most likely sandstone in the 1st place, and it can be associated with Miletice sandstone. Since both the samples can be regarded as original, it cannot be excluded that in addition to using it for Queen Anne’s Summer Palace, the architect Wohlmut also applied it here. Hloubětín sandstone, used for the choir’s construction in the 16th century and placed 2nd in visual resemblance, can be considered for sample 7 as well. Yet, a classical petrographic analysis of samples would have to prove or disprove this statement. In this case, however, it is a destructive method, the implementation of which is very difficult in view of the undesirable damage to the unique monument.

Stone Elements Provenance, 20th Century

Sandstone from Kuks was identified as the most similar to that used for the Wolhmut Choir plinth. This finding corresponds with the information acquired from available written sources27 inter alia stating that the plinth was made of Dvůr Králové sandstone. It marks a wider group of sandstones quarried near Dvůr Králové nad Labem in the past. Kuks sandstone can ’geographically’ be labelled as Dvůr Králové sandstone, as its deposit is found less than 8 km from Dvůr Králové nad Labem. A similar result can be found in sample 4 as well.

The results of sample 1 are far from this clear. Leaving aside the sandstone from Kamenné Žehrovice which shows the greatest optical analogies, though in fact it is utterly different and cannot be considered, then in addition to sandstone from Kuks in the 3rd place, the one from Boháňka must be considered. Moreover, it is placed in the first three positions for the plinth as well as sample 4. It is interesting that this locality cannot be theoretically eliminated because this sandstone was used, for example, for the new part of St. Vitus Cathedral, specifically the balustrade of six chapels during 1920–192231, and along with sandstone from Podhorní Újzed, Mšeno, Dvůr Králové nad Labem, and Stanovice near Kuks was delivered for the completion of the cathedral beginning in the 1920s27. Nevertheless, the choir was dismantled and reconstructed as late as 1924–1925, but this theoretic possibility cannot be fully excluded. Yet, based on the written sources about the stone material for the Wohlmut Choir plinth and from the visual similarities of samples (Fig. 12 and e.g. fig. 9), the sandstone from Kuks appears to be the most likely.

Worked surface of sample 1.

The stone ashlar in the choir’s crown (sample 8, see Fig. 10) was identified as Mšeno sandstone based on the spectral reflectance curve analysis. It placed second in the visual similarities order. The datation acquired from the traceological analysis supports the achieved results that further correspond with the results of our archival research (see Chapter 2.1).

Reflectance spectroscopy limitations

As emerges from above, reflectance spectroscopy for the identification of the building and decoration stone provenance has high potential. As any other method, this has limits, mostly in the cleanliness of the surveyed surface. Impurities, surface crusts, and surface adjustments performed influence the spectral reflectance curves (see Fig. 13), and thus complicate stone identification. As visible in the following graph, the natural colour of the given rock, owing to the spectral range (1000–2500 nm), plays a less significant role in identification.

An illustration of the stone impurity influence on spectral reflectance curves, St. Vitus Cathedral, southern staircase.

Furthermore, results can be influenced by ongoing erosion processes that can produce changes in rock mineral composition, e.g.50. The sandstone structure very often contains, for example, halite and gypsum salt crystals, the typical products of weathering processes51,52. This negative effect cannot be fully eliminated; however, it can be partially influenced by restoration treatment grounded in masonry desalination, e.g.53,54. Similarly, prior to provenance identification by reflectance spectroscopy, restorers can remove mechanical impurities and crusts from the surface by laser55. However, the impact of weathering processes, impurities, and crusts on the surface is often insignificant in the interiors of historical buildings or stone collections. Finally, one must consider the possible negative impact of restoration treatments, such as the application of consolidation alkoxysilane coatings whose application, by ageing, produces silicon dioxide and silica gel56. The presence of these silicon phases impacts the character of the spectral reflectance curve and, thereby, considerably complicates or prevents the original stone from identification. Frequently used lime-based coatings can impede the determination of the stone provenance in a similar way, as they produce calcium carbonate when ageing57; its presence affects the character of the given spectral reflectance curve. It is reasonable to expect that other means of restoration that produce new mineralogical phases in the stone structure have a similar effect. From this perspective, it is necessary to know the ’history’ of the surveyed stone when subjecting it to reflectance spectroscopy, which unfortunately is often impossible.

Conclusion

Reflectance spectroscopy is a highly promising method to determine stone provenance in historical buildings or artefacts made of it. Yet, the use of the method is not fully sufficient with current knowledge, and other non-destructive methods should be used for precision. In this respect, an interdisciplinary approach and the knowledge of experts from various disciplines, including natural sciences, technology, and historical sciences, is highly recommended.

The non-destructive character is the greatest benefit of our approach and applied methods. Reflectance spectroscopy and applied traceology are simple in situ methods, although the data generated from both are difficult to process. In reflectance spectroscopy, it is the exacting and qualified comparison of spectral reflectance curves by available software and the possible ambiguity of the results obtained caused by small reflectance differences of particular rock types in the given spectral range. This fact can be partially eliminated in practice by using the relevant content of the spectral reflectance curves library, i.e. curves from the given period of time that can be identified by a traceological analysis. By this, potentially ’useless’ similar rock types are eliminated. However, this procedure can only be applied with sufficient knowledge of the historical stone sources from the given periods.

An interdisciplinary collaboration with experts investigating the use of stone, building history research, archival research, art history, archaeology, heritage care, and restoration is essential to achieve the most precise results. Their knowledge and findings about the use, extraction, working, and maintenance of natural stone in the given historical periods for specific works and buildings can help to choose the right rock from the ones with the most similar reflectance. The mentioned disciplines shall then form the most significant group of commissioners and recipients of the reflectance spectroscopy application. With regard to the art history perspective, it is a considerable progress in the possibilities of understanding the development of architecture of a given building that can be applied to other stone monuments. In this way, the knowledge about the building and decoration stone provenance available from literature and archival research have been verified, supported, and expanded by new interpretation possibilities.

In conclusion, it can be stated that the selected multidisciplinary procedure enabled us to verify the applicability of the given methods for the given purposes. Expanding the spectral library by the spectrums of all rocks used in every period is certainly desirable for a more precise identification of all stone elements. Further research possibilities are the development of new, more suitable algorithms for the comparison of spectral reflectance curves.

Responses