New thinking is needed to make the most of formerly improved upland pastures

Introduction

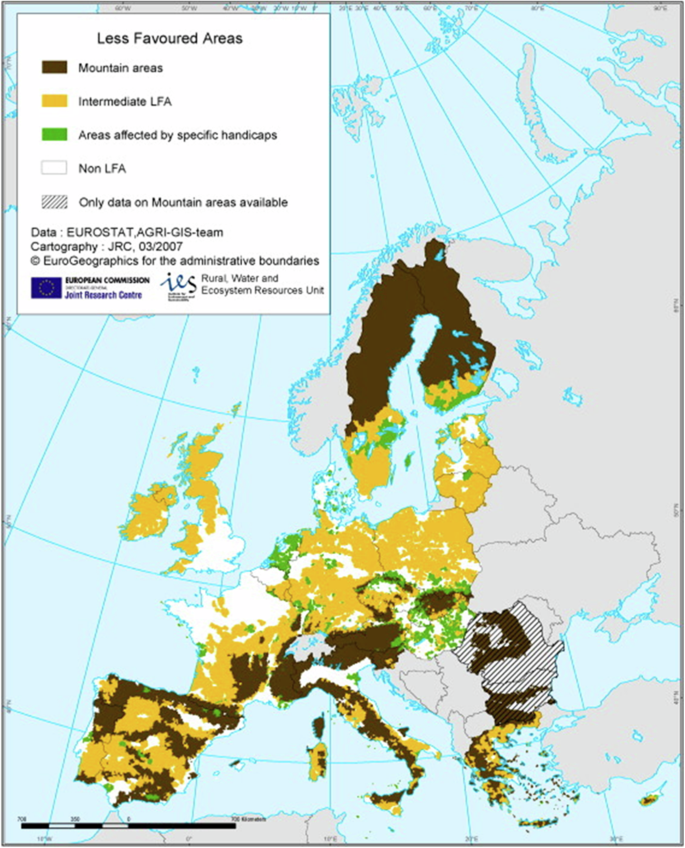

Globally and nationally, non-urban land is increasingly expected to deliver a wide range of potentially competing provisioning, regulating, cultural and supporting ecosystem services. A recent analysis by the Royal Society has highlighted the extent to which the UK’s land is “overpromised”1. Their report estimates that ~1.4 Mha of additional land will be needed by 2030, and a further ~3.0 Mha land by 2050, to meet policy targets to restore peatland, scale up bioenergy production, and protect land for nature (assuming agricultural production, diets and food waste remain unchanged). Clearly it is imperative that we make full, but sustainable, use of the resources we have available. Just under 50% of UK utilised agricultural land was previously eligible for additional support under the EU Less-Favoured Areas (LFA) directive, with the equivalent figure for the EU 36%2,3 (Fig. 1). Such areas are characterised by natural handicaps (e.g. thin, nutrient-poor soils; steep slopes) and are at an associated risk of depopulation, and, within the UK, LFAs have been synonymous with the hills and uplands4.

Classification of less-favoured areas in Europe by category (Eliasson et al.3)

Climatic conditions in upland areas can be extreme and highly variable, with related challenges to plant growth arising from exposure to wind, low temperatures, high rainfall, and frequent winter frosts5. Additional abiotic constraints to plant growth include acidic soils and shortages of available plant nutrients, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus6. Collectively, these factors typically limit farming systems to grassland-based livestock production, and rearing livestock in areas unsuitable for the cultivation of crops offers additional food security while avoiding conflicts associated with the use of arable land to produce animal feed7. Through their symbiotic relationship with rumen microflora and fauna, ruminant livestock turn forages and poor-quality feeds into human-edible products, and research has shown there are benefits for human health from grass-based meat production8. However, there is inevitably an environmental cost in terms of excretion of pollutants including greenhouse gases9, and methane emission intensities (methane emitted per unit of production) rise as concentrations of dietary fibre increase and forage digestibility declines10,11.

Grazed resources within the uplands of the UK can be divided into two categories. The first, rough grazing, consists of semi-natural grasslands and heathlands, and accounts for approximately two-thirds of the corresponding agricultural land area. In recent times these native vegetation communities have been increasingly valued for the provision of public goods such as biodiversity, water management, and carbon storage, and future land use policies are likely to prioritise such deliverables. However, relative to cultivated grasses and forage legumes the nutritional value of the native plant species they consist of is poor12 and their acceptability to stock is low13, leading to low voluntary intakes and poor animal performance. Almost all of the remaining third of upland agricultural land in the UK, around 2.27 Mha, is categorised as ‘improved’ grassland because of historical efforts to enhance productivity in the uplands. This paper explores the history of these pastures, their current limitations, and opportunities and strategies for future developments. We argue there is a pressing need for these sown pastures to undergo a fresh round of intervention to simultaneously deliver sustainable increases in production efficiency plus environmental gains. While the original wave of land improvement was driven exclusively by demands for increased productive output, grasslands today must also play an important role in delivering wider public goods including nature recovery, carbon storage, and water management. Although we focus on the UK and related research and policies, the issues raised are common to many marginal areas across northern Europe (Fig. 1).

The first wave of upland improvement

In the 1930s, Wales was the stage for Sir George Stapledon’s pioneering Cahn Hill Improvement Scheme, which replaced indigenous vegetation with more productive, cultivated swards14,15. Stapledon considered upgrading the uplands vital to increasing agricultural productivity and preserving the disadvantaged rural communities found in these areas, thereby reducing the risk of agricultural abandonment16. He was also mindful of the UK’s reliance on cheap imported animal products, and reasoned that improved upland grasslands could serve as a reservoir of ruminant livestock production, allowing lowland areas to focus on arable production16. Related research focused on approaches to reducing the challenges to the establishment and persistency of improved pasture posed by acidic soils limited in major soil nutrients. Key to achieving the desired improvement in productivity was the introduction of plant species, especially perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) and white clover (Trifolium repens), capable of higher production over a longer growing season than the native grasses being replaced17. These sown species also had a higher feeding value for livestock, and thus, collectively the techniques deployed resulted in a marked increase in the stocking densities possible and the quality of product produced5,18, and, with government support, they were deployed widely both nationally and internationally.

The species and varieties of grasses used for reseeding the hills had been bred in lowland environments, i.e. they were plants that had been selected for superior performance when growing in fertile soils and clement climatic conditions. Thus, high rates of inorganic fertiliser were required to achieve successful establishment and subsequently ensure persistency. While later studies would show that varieties of lesser known grass species such as red fescue (Festuca rubra) were more productive and persistent than perennial ryegrasses under more challenging physical and climatic conditions19,20,21, the corresponding herbage quality and stock performance was poorer22, and thus breeding efforts with such grasses were limited. From the 1950s to the 1970s, research efforts globally extended and refined the techniques pioneered by Stapledon and colleagues5, and by the early 1980s herbage yields were up to five times higher for improved upland swards compared to native grassland21. Such pastures had, by this time, become crucial to the viability of livestock farming in the hills and uplands23. The bulk of the improved upland swards found in the UK today were sown during this period as farmers responded to the sustained policy drive for land improvement heavily promoted in the farming press, and took advantage of the generous government grants covering associated establishment costs. Subsequent and more recent research programmes then focussed on optimising management guidelines for the use of such swards in terms of target sward heights and grazing regimes24,25,26, rather than continued sward innovation. Thus, in terms of botanical composition, these pastures can be considered relics from a different era; specifically, one that focussed almost exclusively on gross productivity.

Improved upland permanent pastures today

Upland farming systems across the UK, EU, and other temperate regions remain heavily reliant on the use of improved permanent pasture to achieve economic sustainability. However, over time, the grasses and legumes that constituted the mixes originally sown have been replaced by unsown species from the seedbank20,27, often leading to a decline in pasture performance. Since the grasses previously introduced were heavily reliant upon substantial nutrient inputs to remain competitive28,29, this process has been exacerbated by ever-decreasing application rates of inorganic fertilisers in response to environmental concerns and rising costs. Table 1 summarises results from a long-term experiment exploring the impact of the withdrawal of nutrients to permanent pasture relative to a control treatment receiving 150 kg N ha−1, which was representative of commercial practice at the time the study commenced (1990)30. Today, large expanses of permanent pasture no longer receive routine applications of lime or fertiliser, and thus the productivity gains once associated with these formerly improved pastures have been further eroded. As a result, even when optimal management guidelines are imposed, post-weaning liveweight gains for prime lambs grazing such pastures are often below 100 g/d26,31. However, growth rates of (a) 200 g/d and (b) 200–300 g/d have been recorded for similar animals finished on (a) reseeds of modern ryegrasses bred for elevated concentrations of water-soluble carbohydrates (‘high sugar’ grasses)32 and (b) the forage legumes red clover (Trifolium pratense) and lotus (Lotus corniculatus)33, grown in similar marginal areas. Carcass weights in relation to liveweight prior to slaughter (killing out percentage) were also increased by grazing red clover33, further improving economic returns and supply chain efficiency, demonstrating sustainable intensification and reducing greenhouse gas emission intensities.

Such findings illustrate the potential for upgraded and updated permanent pastures to make a major contribution to national and international targets for improved agricultural sustainability. More recent research has quantified enteric methane yields and intensities for sheep and cattle offered different grassland types, and confirmed that methane intensities are significantly lower for stock when grazing newly sown swards (<5 years old) compared to permanent pasture34. Delivering improvements in stock performance and nutrient use efficiency and reducing time to slaughter via updated improved pastures would substantially reduce the environmental impact of the associated supply chain, whilst improving traceability through a reduction in the use of supplemental concentrate feeds (mixes of grains, pulses, oil meals etc.) that are frequently imported. It would also increase economic viability in areas heavily reliant upon support payments. Results from annual Farm Business Surveys clearly show that upland farms across the UK remain economically unviable without subsidy support35,36,37,38, a situation echoed in EU countries39, and farming communities have been passionately opposed to reforms in support. Associated land abandonment could result in a serious loss of public goods and services relating to landscape quality, water resources and recreation. Conversely, improving economic returns for upland farmers would support wider rural communities in areas at risk of depopulation, while reduced reliance on agricultural support payments would benefit taxpayers. There is also clear societal value to achieving a resilient food chain with high welfare standards through sustainably increasing yields whilst decreasing the associated environmental footprint. In short, the uplands continue to face many of the challenges which first inspired Stapledon’s programme of improvement.

A new and increasingly urgent additional challenge is adaptation to climate change. Data show that the period 1991–2020 was, on average, 0.9 °C warmer than 1961–1990 in the UK, with warming occurring across all months40. Subsequently, 2022 was the warmest year since 1884 and included a heatwave which exceeded previous records by a considerable margin41. UK summers were, on average, 17% wetter in the decade between 2011–2020 than the decade between 1961–199040, and across the most recent decade (2013–2022) UK winters have been 10% wetter than 1991–2020 and 25% wetter than 1961–199041. Variability in rainfall is also increasing; 2020 included the fifth wettest winter and the fifth driest spring in the UK since 186240 while 2022 included the UK’s eighth wettest February on record as well as the driest summer since 199541. These climatic shifts will have consequences for the frequency and nature of climatic hazards42. Extreme droughts are projected to worsen43, yet the likelihood of intense rainfall events is also increasing44. The greatest impacts will be felt in upland regions, where increased potential evapotranspiration in late spring and early autumn will result in drier soils42. On the other hand, these areas have the potential to play a vital role in terms of water storage and regulation of flows to lower-lying areas and could be instrumental in reducing the risk of flooding if rainfall infiltration can be increased.

The potential for change

Plant breeding has made major advances in the decades since large tracts of the UK uplands were last improved. Selective breeding has produced ryegrass varieties and lines with improved digestibility and higher concentrations of water-soluble carbohydrates; increasing their intake potential for livestock as well as the availability of readily available energy for microbial protein synthesis in the rumen and associated improved nitrogen use efficiency by livestock45. New ryegrass × fescue hybrids (festuloliums) have also been developed. Depending on the specific cross made, these grasses can be characterised by deep rooting systems which provide (i) adaptation to climatic extremes and (ii) the potential to reduce water runoff and related flooding risk46. At the same time, a new generation of forage legume varieties has emerged from breeding efforts to improve yield and reduce susceptibility to pests and diseases47. The ability of temperate forage legumes to fix atmospheric nitrogen has become an essential characteristic for more extensive systems of animal production that can less easily sustain the cost of annual dressings of inorganic nitrogen. There are also sustainability benefits associated with higher voluntary intakes resulting from legumes being more susceptible to particle breakdown during ingestion and rumination, leading to more rapid clearance from the rumen48,49. Higher intake rates are generally correlated with increased liveweight gains, in turn leading to faster finishing times for stock33 and lower methane emission intensities. Forage legumes are also an important source of dietary protein, with red clover and lotus-containing compounds (polyphenol oxidase and condensed tannins, respectively), which have been shown to reduce proteolysis in the rumen, leading to improved nitrogen uptake by the animal45,50. The presence of condensed tannins has also been linked to reductions in methane emissions51, and lower infection rates by intestinal parasites50,52. In terms of soil/plant interactions, it has been reported that legumes can promote soil carbon and nitrogen storage and improve soil structure and drainage through improved soil aggregation (which increases soil porosity and water infiltration)53. Both soil carbon and nitrogen pools are enhanced in the presence of red clover and lotus through reduced losses of carbon from ecosystem respiration, increased soil organic matter content and improved soil structure54. Thus, legumes also have the potential to contribute to flood control in the UK by improving water retention in upland areas, as well as mitigation of climate change through increased soil carbon storage55.

Recent research suggests that sustained climate-driven losses of soil carbon are currently occurring across many ecosystems, including grasslands56. Whether or not a grassland accumulates or loses carbon is a function of input and output, with carbon sequestration occurring when gross primary productivity exceeds respiration. Total soil carbon dioxide emissions, in turn, include contributions from plant roots (autotrophic respiration) as well as microbial respiration of soil organic matter (heterotrophic respiration). The combined effects of grassland type and grazing on soil organic carbon are, however, highly variable due to confounding factors including climate, soil type, sampling depth and species mix57. More research, particularly field-trial data, is needed to reduce uncertainty in predictions of change, but the morphology and function of grassland plant species will inevitably have a crucial role to play in future attempts to maximise sequestration within pasture-based ruminant livestock systems challenged with achieving net zero.

Further developments required

If we are to meet the inter-related challenges outlined above, new research efforts are needed that focus on developing climate-smart multi-functional grassland mixtures based on species and varieties of grass, legumes and additional plant groups adapted to low fertility conditions, as a fundamental shift away from altering soil conditions to suit very productive grass species heavily reliant upon nutrient inputs. The introduction of new species and varieties of grasses and forage legumes could radically improve livestock production yields and efficiencies in marginal areas, while also enhancing ecosystem service provision beyond primary production58,59,60,61. However, to achieve this, grassland agriculture and its wider supply industries will need to reframe their measures of success.

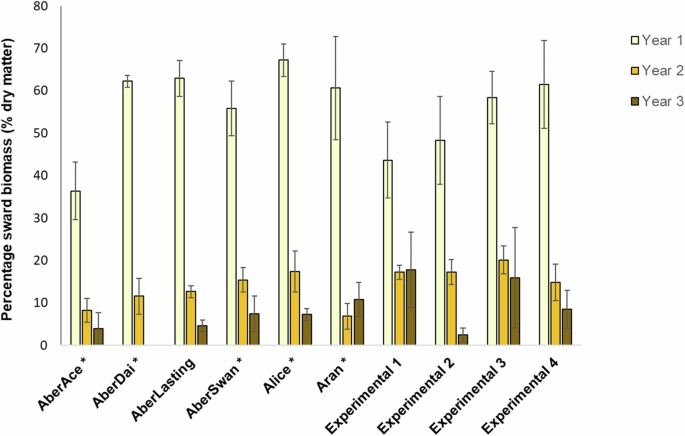

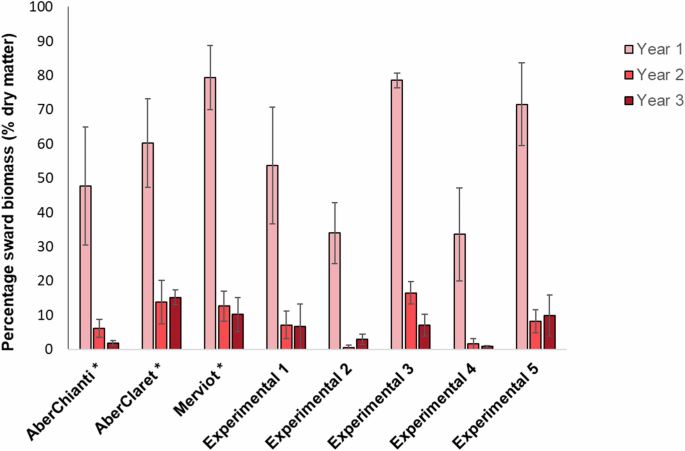

Within the EU, any new variety must be submitted for national list testing before they can be marketed. Booklets of recommended lists are then produced, targeted at farmers and growers and promoted by groups including livestock levy bodies and seed companies. In terms of demonstrating improved “value for cultivation and use” (VCU), grass testing in many countries (plus the UK) is currently limited to quantifying herbage yield, forage digestibility, disease resistance and ground cover62. Testing of red clover and lucerne reports these parameters plus crude protein content62. In all cases, the associated small-scale field trials from which the data are derived are conducted on sheltered, fertile sites with test varieties grown in isolation and receiving generous applications of inorganic fertiliser to ensure genetic yield potential can be realised. Thus, the testing system rewards gross productivity rather than nutrient use efficiency, and inevitably perpetuates poor performance of mainstream varieties in marginal areas. When white clover (Fig. 2) and red clover (Fig. 3) were evaluated under such conditions, the legume component significantly (p < 0.001) decreased from year 1 to year 3, compromising the persistence of the species. The results are from trials where plots of each variety were established in upland conditions on a formerly improved site and managed according to UK National List testing protocols63, and clearly demonstrate the need for varietal testing under alternative growing conditions. In both cases, the specific management guidelines for testing were followed, and the findings reflect the greater environmental challenges that are characteristic of marginal areas. Furthermore, under the testing protocols plots are managed by cutting, which is referred to as simulated grazing. In practice, grazing animals would be expected to selectively consume such forage legumes within a mixed sward64, further reducing the plants’ competitiveness and persistence. The inclusion of new lines and varieties within this experiment indicates there is no immediate prospect of improvement in performance under more marginal conditions. For grasses on the recommended lists the environmental challenges would be further compounded by management and substantially lower rates of nitrogen fertiliser being the industry standard in such areas.

Plots were managed by cutting. Varieties marked with an asterisk were on the 2021/22 Recommended Grass and Clover Lists for England and Wales. Experimental varieties are new varieties currently under development by plant breeders at IBERS, Aberystwyth University.

Plots were managed by cutting. Varieties marked with an asterisk were on the 2021/22 Recommended Grass and Clover Lists for England and Wales. Experimental varieties are new varieties currently under development by plant breeders at IBERS, Aberystwyth University.

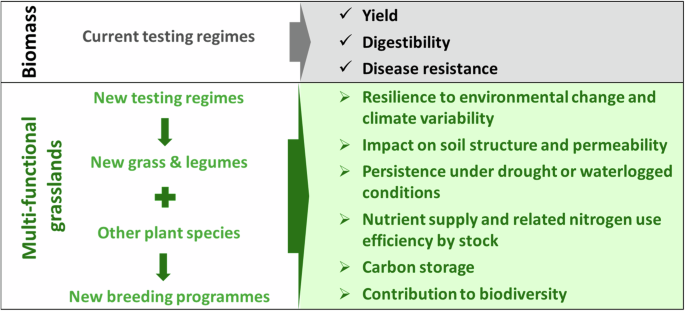

Without a fundamental shift in expectations there will be no impetus to revise the current system of testing. Despite the extent and importance of upland livestock systems (the bulk of the UK beef suckler herd and UK sheep breeding flock are found in these areas), the overall market share of related seed sales is low given the economic challenges and relative infrequency of reseeding. Thus, there is perceived to be no commercial benefit to investing in related research and development. If the assessment criteria were to evolve to consider factors beyond primary productivity, such as future resilience to environmental change and climate variability, impact on soil structure and permeability (to reduce surface water run-off), persistence under drought or waterlogged conditions, nutrient supply and related nitrogen use efficiency by stock, and potential contribution to biodiversity, then innovation would be incentivised within a major national and international land use. This in turn would support the delivery of a range of UK government and industry commitments, including; (i) net zero greenhouse gas emissions from farming by 2040, (ii) conservation of 30% of the UK’s land for nature by 2030 and (iii) maintaining food security and the rural communities underpinning it. However, this would require a fundamental shift away from the current framework for developing and testing new products for inclusion on Recommended Lists (e.g. Fig. 4).

Current (grey) and proposed (green) criteria for inclusion in National List testing of grass and clover varieties.

Such a shift would require substantial investment to research, develop and validate new testing methodologies. It would also require recognition that when choosing species and varieties there may be trade-offs to be made between those best for primary production and those which deliver other public goods and/or sward resilience.

As outlined previously, in past decades policy and related support payments have driven transformative changes in upland farming systems. For the most part, these were to deliver production gains. Given the urgency of the climate emergency and biodiversity loss nationally and globally, is it not again time for policy to intervene? Should a second wave of upland grassland transformation not be supported and promoted in the same way as the original improvement drive, this time creating diverse, multi-functional grasslands delivering multiple public goods? Focussing such a programme on ecologically poor, previously improved upland pasture would, in turn, promote land sparing and protection of indigenous grasslands and heathlands, and thus also support wider environmental and sustainability goals in upland landscapes.

Responses