Nighttime phenotype in patients with heart failure: beat-to-beat blood pressure variability predicts prognosis

Blood pressure variability

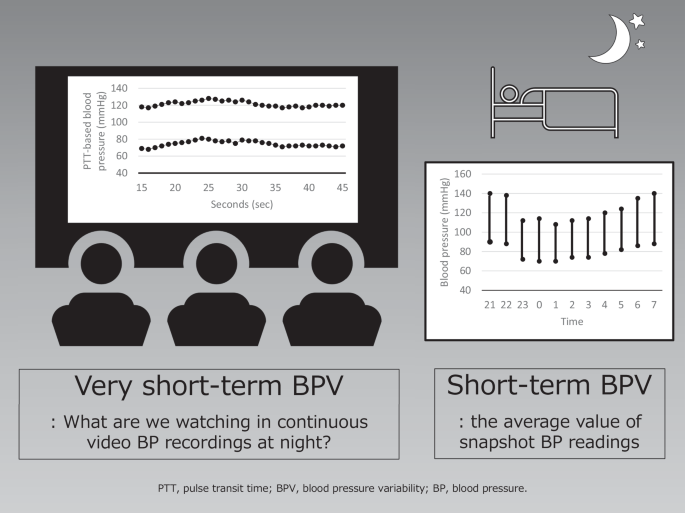

Blood pressure variability (BPV) is classified according to time scale into very short-term (beat-to-beat), short-term (within 24 h, minute-to-minute, hour-to-hour, and day-to-night), mid-term (day-to-day), and long-term (visit-to-visit over weeks, months, seasons, or years) [3]. All classifications of BPV represent complex, dynamic interactions between intrinsic mechanisms and extrinsic factors and are essential for maintaining BP ‘homeostasis’ to ensure adequate vital organ perfusion under varying conditions. One needs to understand that all classifications of BPV have different mechanisms and determinants and therefore different clinical significances and prognoses. The following are some of the current problems with BPV: It is unclear whether BPV has clinical value or adverse prognostic predictive ability that goes beyond the previous method of diagnosing and treating hypertension using average BP levels. BPV parameters and evaluation methods for BPV have also not been established. Furthermore, there are no standard values for evaluating BPV, and evidence has not been established regarding BPV as a treatment goal (Fig. 1).

Nighttime very short-term blood pressure variability (BPV) versus nighttime short-term BPV

Nighttime short-term blood pressure variability (BPV) and nighttime very short-term BPV

During non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, there is an increase in parasympathetic activity and a reduction in cardiac sympathetic activity. By contrast, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep is a state of autonomic instability, which is dominated by remarkable fluctuations between parasympathetic and sympathetic influences. When the circadian rhythm of BP is normal, the short-term BPV in nighttime BP decreases by 10–20% of the daytime level on waking. A report using a cardiopulmonary coupling analysis showed that normotensive subjects had very-short BPV during sleep and that during NREM stage 3, deep sleep, there was a clear decrease in very-short BPV, reflecting suppressed vascular-sympathetic activity and a trend in elevated baroreflex sensitivity [3]. Nighttime very short-term BPV reflects baroreflex sensitivity, autonomic function, and respiratory movement [4]. Patients with HF have increased neurohumoral factors and arterial stiffness compared with normal subjects, and it is expected that these factors would significantly impact the increase in very short-term BPV at night. In a report by Sato et al. [2], there was a very weak but significant correlation between the value of the cardio-ankle vascular index and the coefficient of variation (CoV) for systolic BP and between the value of hemoglobin A1c and CoVs for systolic and diastolic BP. This may have been due to the possibility that the decreased arterial wall distensibility associated with elastic arteriosclerosis and autonomic neuropathy associated with abnormal glucose metabolism caused a decrease in sensitivity and dysfunction of the baroreceptor reflex system, which may have contributed to the increase in very short-term BPV. Arousal is also one of the causes of increased nighttime very short-term BPV. Arousal from sleep can occur through respiratory efforts, limb movement, and spontaneous arousal [5, 6]. Arousal induces autonomic changes, resulting in increases in nighttime BP. In a study by Davies et al., healthy subjects were assessed for very short-term BPV during each sleep stage using beat-to-beat BP monitoring [7]. When arousal occurred, the average systolic BP/diastolic BP rose 10.0/6.1 mmHg during NREM sleep and 6.0/3.7 mmHg during REM sleep, compared with control values, over the 10 s following the application of a stimulus to induce transient arousal [7]. HF patients characterized by increased sympathetic nervous system activity often suffer from sleep problems [8]. The mechanism by which nighttime very short-term BPV increases in HF patients through frequent arousals cannot be ignored.

Although some reports have shown a correlation between an increase in very short-term BPV and organ damage, there is no consensus as to whether very short-term BPV is a cause or a result of organ damage, i.e., whether it can be a therapeutic target or is merely a surrogate marker for organ damage.

Noninvasive nighttime blood pressure measurement

The BPV in nighttime BP is smaller than that in daytime BP. Therefore, if nighttime BP measurement were possible without any burden, nighttime very short-term BPV might make it easier to grasp a subject’s true intrinsic condition because extrinsic stimuli decrease at night. In healthy individuals, even stimuli during sleep that did not cause electroencephalogram arousal increased BP [7]. Cuff-based ambulatory BP machines cause appreciable arousal from sleep and therefore alter the BP that they are trying to record [9]. Although the pulse transit time-based continuous BP monitoring method [10] used in this study has the limitation of requiring frequent calibration, it may be less intrusive and may be useful for measuring nighttime very short-term BPV and short-term BPV.

Responses