Non-pharmacological interventions of intermittent fasting and pulsed radiofrequency energy (PRFE) combination therapy promote diabetic wound healing

Introduction

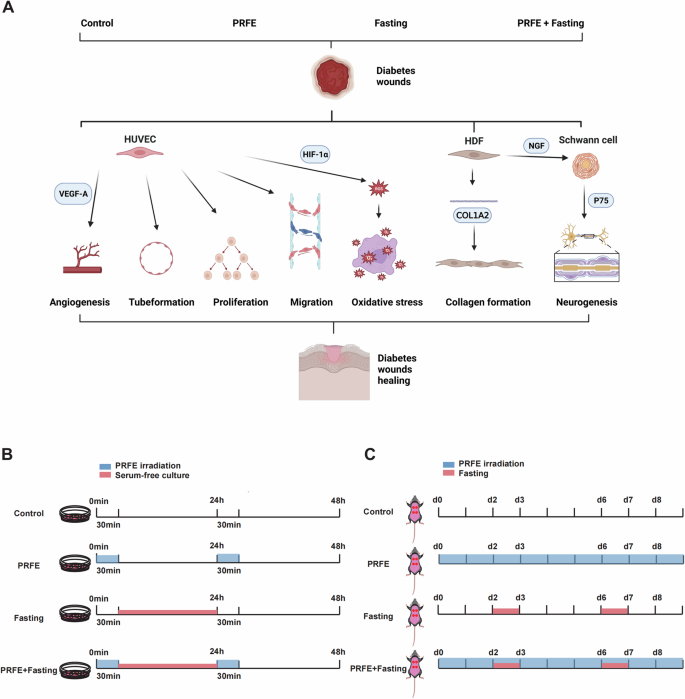

The global prevalence of diabetes is increasing, leading to a widespread and intricate issue of impaired wound healing among individuals with diabetes [1]. Due to the impact of diabetes on both glycemic control and microvascular circulation, these patients frequently encounter difficulties in achieving effective wound healing [2]. Hence, the search for novel and effective therapeutic strategies is of paramount importance for improving wound healing in diabetic patients. PRFE represents an emerging therapeutic approach, utilizing a non-ionizing and non-thermal radiofrequency emission system to deliver low-energy electromagnetic signals. Clinical research has underscored pulsed radiofrequency energy (PRFE)’s potential in augmenting wound healing and complex diabetic foot Wounds [3]. Our preliminary investigations have unveiled that PRFE treatment has the capability to enhance the healing of diabetic mouse wounds by stimulating fibroblast proliferation and the synthesis of type I collagen, yet without substantial enhancement of angiogenesis [4]. Conversely, intermittent fasting has been shown to promote endothelial vascular generation and subsequently foster angiogenesis, thereby aiding diabetic wound healing [5]. These findings sparked our minds. Considering that both PRFE and intermittent fasting are categorized as non-conventional medical interventions, with PRFE being a form of physical therapy and intermittent fasting involving dietary manipulation, our objective is to integrate these two methods, seeking to leverage their respective strengths and synergize their benefits. Given the limited exploration of intermittent fasting’s mechanisms of action beyond angiogenesis in diabetic wound healing [5], this research aims to conduct a more comprehensive analysis of the underlying mechanisms responsible for the synergistic outcomes of the combined therapy in improving diabetic wound healing. This multidimensional approach involves creating high-glucose models of vascular endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and Schwann cells (SCs), along with a diabetic animal model, to investigate mechanisms encompassing proliferation, tube formation, angiogenesis, migration, oxidative stress, fibrogenesis, and sensory nerve growth (Fig. 1A).

A Exploration of the mechanisms of Intermittent Fasting and PRFE in promoting diabetic wound healing. B Cellular experimental model illustrations for the Control group, PRFE group, Fasting group, and PRFE+Fasting group. C Animal experimental model illustrations for control group, PRFE group, Fasting group, and PRFE+Fasting group.

Vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) exhibits potent pro-angiogenic activity both in vitro and in vivo [6]. Consequently, we utilized VEGFA as a molecular indicator to explore the mechanisms governing angiogenesis. It is widely acknowledged that elevated oxidative stress within the wound microenvironment can hinder angiogenesis, compromise endothelial function, and consequently impede the timely healing of wounds [7]. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α (HIF-1α) serves as a pivotal transcription factor in regulating the adaptive response to hypoxia. Previous studies have substantiated the suppressive impact of elevated blood glucose levels on HIF-1α [8]. Simultaneously, a hierarchical association exists between HIF-1α and VEGFA, known as the HIF-1α/VEGFA signaling pathway [9]. Following our investigation into the impact of combination therapy on VEGFA, we aim to examine the potential of the therapy in mitigating the detrimental effects induced by oxidative stress via the HIF-1 pathway. Subsequent to HIF-1α, we identified the presence of the neurotrophic factor receptor p75. Literature indicates that HIF-1α is a primary target of p75. p75 possesses the capability to establish a favorable feed-forward mechanism contributing to the oxygen-dependent stabilization of HIF-1α [10]. Heightened p75 expression has the potential to induce the transformation of astrocytes into reactive astrocyte phenotypes, whereas the absence of p75 hinders the molecular interactions linking cellular constituents [11]. This holds paramount significance for neural growth. The essential function of p75 in sustaining the viability and operational efficiency of sensory neurons is well-established. Mice lacking the p75 gene exhibit a marked decrease in sensory cutaneous nerve innervation [12]. Notably, the excessive expression of nerve growth factor (NGF), a ligand for p75, in the skin has the potential to lead to an increased density of sensory nerve distribution [13].

This investigation aims to assess the clinical viability of the combined therapy involving intermittent fasting and PRFE in a comprehensive manner. By elucidation of outcomes across diverse phenotypic dimensions and exploring the underlying mechanisms, this research endeavors to establish a theoretical foundation and innovative methodology for non-conventional medical interventions dedicated to improving wound healing in diabetic patients.

Materials and methods

Animals

This study received approval from the Ethics Committee the Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology. Male C57BL/6 J mice (Vital River Laboratories, China) were housed in a specific pathogen-free environment at Tongji Medical College Animal Center. After a 4-week high-fat diet, mice underwent an overnight fast. Streptozotocin (STZ) (Biosharp, China) was dissolved in citrate buffer (0.1 mmol/L citric acid: 0.1 mmol/L sodium citrate at a 1:1.32 ratio) to form a 0.01 mg/μL solution (Prepared immediately before use). Mice received a single intraperitoneal injection of STZ based on weight (0.1 mg/g) to induce a type 2 diabetes mouse model. On the fourth day, we measured fasting blood glucose levels, consistently exceeding 11.1 mM, indicating successful modeling [14, 15].

To establish a murine model of diabetes with full-thickness skin incisions, we anesthetized STZ mice (50 mg/kg) using 1% pentobarbital, removed the dorsal hair, and disinfected the corresponding skin area with 75% alcohol. After delineating two 6mm-diameter-circular areas on each side of the back, we used the iris to remove the skin and subcutaneous tissue, creating a full-thickness skin wound on the dorsal area. Post-surgery, the wounds were cleansed with sterile physiological saline solution, thereby completing the modeling process. To investigate the effects of intermittent fasting and PRFE on diabetic wound healing, STZ mice were randomly divided into four groups based on body weight, each containing 10 mice: 1) Control group: Diabetic wounds received no specific treatment; 2) PRFE group: Mice received PRFE treatment alone, twice daily, with each session lasting 30 min; 3) Intermittent fasting group: Mice fasted for 24 h on the 2nd and 6th days post-wound creation; 4) Intermittent fasting and PRFE group: Mice fasted for 24 h on the 2nd and 6th days post-wound creation, while also receiving PRFE treatment twice daily, with each session lasting 30 min.

After wound creation, photographs of the wound were captured on days 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 to document the healing progress. The wound closure was calculated using Image J and subjected to statistical analysis.

On the 8th day, skin samples were obtained from the modeled region. Half of the tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for histopathological analysis, while the remaining half were promptly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for subsequent experiments involving western blotting (WB) and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR).

Cell culture and treatments

HUVECs (ATCC, USA) and rat SCs (China Center for Type Culture Collection, China) were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, PM150210, Procell, China) supplemented with 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin Solution (PB180120, Procell, China) and 10% premium fetal bovine serum (164210, Procell, China). HDFs (ScienCell, USA) were cultured in Fibroblast Medium (2301, ScienCell, USA) with 25 mM D-Anhydrous Glucose (BS099, Biosharp, China). All cells were cultured at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

In order to assess the mechanistic impact of combined intermittent fasting and PRFE therapy on skin cells, we partitioned the cells into four distinct groups: 1) Control group: Cells were cultured in high-glucose medium with serum for 48 h; 2) PRFE group: Cells were cultured in high-glucose medium with serum for 48 h and received 30 min of PRFE treatment every 24 h; 3) Intermittent fasting group: Cells were cultured in serum-free high-glucose medium for 24 h followed by culture in high-glucose medium with serum for another 24 h; 4) Intermittent fasting and PRFE group: Cells were cultured in serum-free high-glucose medium for 24 h followed by culture in high-glucose medium with serum for another 24 h. Additionally, cells in this group received 30 min of PRFE treatment every 24 h. Following the principle of synchronizing with animal experiments, PRFE treatment was administered prior to changing the culture medium.

Histological and immunohistochemical staining

After fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde, the skin tissue was subsequently embedded in paraffin and sectioned into 4 μm-thick slices for further histological and IHC staining.

The purpose of HE staining is to observe the tissue structure of the wound and measure epidermal thickness and scar width using the Slideviewer software. The steps for HE staining involve staining dewaxed sections with hematoxylin and eosin, followed by dehydration and mounting. Masson’s staining involves deparaffinization and rehydration of the sections, overnight fixation in Bouin’s solution, staining with iron hematoxylin, acid fuchsin staining, treatment with phosphomolybdic acid, and finally countersinking with aniline blue before dehydration and slide mounting. The primary objective of Masson’s staining is to visualize the presence of fibrous tissue in the examined samples. Image J software was used to measure the relative integrated optical density (IOD) of each wound site view on the stained sections.

For IHC, the procedure involved deparaffinization and rehydration of the sections, antigen retrieval, endogenous peroxidase and biotin blocking, serum blocking, primary antibody incubation, secondary antibody incubation with horseradish peroxidase conjugate, 3,3’-Diaminobenzidine staining, counterstaining with hematoxylin, dehydration and clearing, and finally slide mounting. The primary antibodies used in this study including anti-CD31 (1:2000, 28083-1-AP, Proteintech, China), anti-CGRP (1:900, A5328, Abclone, China), anti-HIF1A (1:200, 20960-1-AP, Proteintech, China), and anti-Ki67 (1:400, 9129, Cell Signaling Technology, USA). CD31 is employed for assessing angiogenesis and tube formation. CGRP is utilized to investigate sensory nerve growth. HIF1A is used to detect oxidative stress-related markers. And Ki67 is employed to ascertain proliferation. Ultimately, we performed relative IOD measurements using Image J software at the wound site view on each section.

All the aforementioned sections were scanned using a white-light scanner (3DHISTECH, PANNORAMIC SCAN, China).

Immunofluorescent staining

Immunofluorescence (IF) staining was conducted on HDFs and SCs cells. Cells were initially seeded onto coverslips in a 12-well plate. After 48 h of treatment according to the designated groups, they were removed from the incubator, washed with Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100, and subsequently blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin. Following this, they incubated in primary antibody (anti-COL1A2, 1:1000, 14695-1-AP, Proteintech, China; anti-P75, 1:100, Abclone, China) overnight, followed by secondary antibody staining with Alexa 488 (Proteintech, China). Finally, the cells were stained with 4’,6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole The samples were then washed and observed under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX73; Olympus Corp., Japan). Lastly, we performed mean intensity analysis using Image J software by selecting three random fields of view on each coverslip.

Reactive oxygen species assay

To ascertain the antioxidant capacity of intermittent fasting and PRFE combined therapy, HUVECs were cultured in a 24-well plate. After 48 h of treatment according to the assigned groups, the 24-well plate was removed from the incubator and washed with PBS. The cells were then co-incubated with the DCFH-DA probe (1:1000, S0033S, Beyotime, China) and Hochest stain (C1022, Beyotime, China). Following washing, the samples were observed using fluorescence microscopy (Olympus IX73; Olympus Corp., Japan). The image J software was utilized to measure the mean intensity of ROS.

Tube formation assay

The HUVECs, treated according to the assigned groups, were seeded at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well onto a pre-coated 96-well plate containing 60 μL of matrix gel (356234, Coring, USA), and incubate the plate in 37 °C for 6 h. Subsequently, three random fields of view were observed for each well using microscopy (Olympus IX73; Olympus Corp., Japan). We use Image J software to assess tube formation efficacy [16].

CCK-8 assay

In the CCK-8 assay, HUVECs were detached from the various groups and seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 103 cells per well, with 5 replicate wells per group. The cells were cultured in serum-free medium for 0 to 24 h. Subsequently, 10 μL of CCK-8 reagent (BS350A, Biosharp, China) was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 1h30min. The absorbance was then measured at 450 nm using a Multiskan FC microplate reader (ThermoFisher, USA). Finally, we utilized the absorbance growth rate as a substitute for cell proliferation rate to quantify the results.

Absorbance growth rate = (Absorbance at the specified time point – Mean absorbance of blank wells) / The mean absorbance of the previous time point after correction with the absorbance of the blank well of previous time point * 100%.

Scratch wound healing assay

For scratch wound healing assay, HUVECs were uniformly seeded into a 6-well plate and treated according to the specified groups. After the the treatment is completed and cell reach 95% confluency, a sterile pipette tip (1 mL) was utilized to create a straight scratch across the center of each well. Subsequently, the wells were rinsed with PBS and supplemented with serum-free medium for appropriate culture. Microscopic images of the cells were captured at 0-, 24-, and 48-hours post-scratch using an Olympus IX73 microscope (Olympus Corp., Japan). The closed area was quantified using Image J software. The rate of cell migration was determined using the formula:

qRT-PCR analysis

According to the protocol, we used Trizol (R411-01, Vazyme, China) to extract the total RNA of respective cells and tissues. For the extraction of total RNA from skin tissue, we weigh and use 20 mg of skin tissue which stays in a 1.5 ml EP tube and add 1 ml of Trizol and grinding beads. The mix is then ground using a homogenizer until the tissue is completely dissolved. The extracted mRNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using HiScript III RT SuperMix for qPCR (#R323, Vazyme, China). qRT-PCR analysis was performed using HiScript II One Step qRT-PCR SYBR Green Kit (Q221-01, Vazyme, China) on the T100 Thermal Cycler (BIO-RAD, USA) detection system. The normalization of mRNA expression was accomplished through the utilization of the housekeeping gene Tubulin. Analysis was conducted using the 2^-ΔΔCT method. The purpose of this experiment was to investigate the impact of intermittent fasting and PRFE on the gene expression level. The primer sequences used are provided in Table 1.

Western blotting

Protein samples were extracted from the corresponding groups of cells and skin tissue using RIPA lysis buffer (BL504A, Biosharp, China) containing Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (G2008-1ML, Servicebio, China) and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (HY-K0010, MCE, USA), as protocol. For the extraction of total protein from skin tissue, we take 30 mg of skin tissue, use 300 µl of lysis buffer in a 1.5 ml EP tube, add a steel grinding ball, and grind it for 20 min using a grinder set at 70 Hz. The extracted protein samples were separated using 10% or 12.5% SDS-PAGE gel (PG112, epizyme, China), then transferred onto PVDF membranes (IPVH00005, Millipore, USA). The membrane was blocked at room temperature for 1 h using NcmBlot blocking buffer (P30500, NCM, China), followed by overnight incubation with the appropriate primary antibody at 4 °C. The primary antibody includes antibodies targeting VEGFA (1:1000, A12303, Abclone, China), COL1A2 (1: 2000, 14695-1-AP, Proteintech, China), HIF1A (1:1000, HY-P80704, MCE, USA), CGRP (1:1000, A5542, Abclone, China), P75 (1:1000, A19127, Abclone, China), α-Tubulin (1:10000, A19127, Abclone, China). After washing with Washing with Tris Buffered Saline (G0001-2L, Servicebio, China) containing 0.1% Tween-20 (GC204002, Servicebio, China) (TBST), the membrane was incubated at room temperature with the corresponding rabbit or mouse secondary antibody (Proteintech, China) for 1 h. Following another round of TBST washing, the membrane was immersed in an ECL chemiluminescence substrate (BL520A, Biosharp, China) and observed using the ChemiDoc XRS+ System (BIO-RAD, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software, and calculations were based on at least three independent experiments. All data are presented as mean ± SD. Four-group comparisons were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. Statistical significance was denoted as follows: P < 0.05 indicated by *, #, or †; P < 0.01 indicated by **, ##, or ††; P < 0.001 indicated by ***, ###, or †††; P < 0.0001 indicated by ****, ####, or ††††.

Results

Intermittent fasting and PRFE combination therapy promotes diabetic wound healing

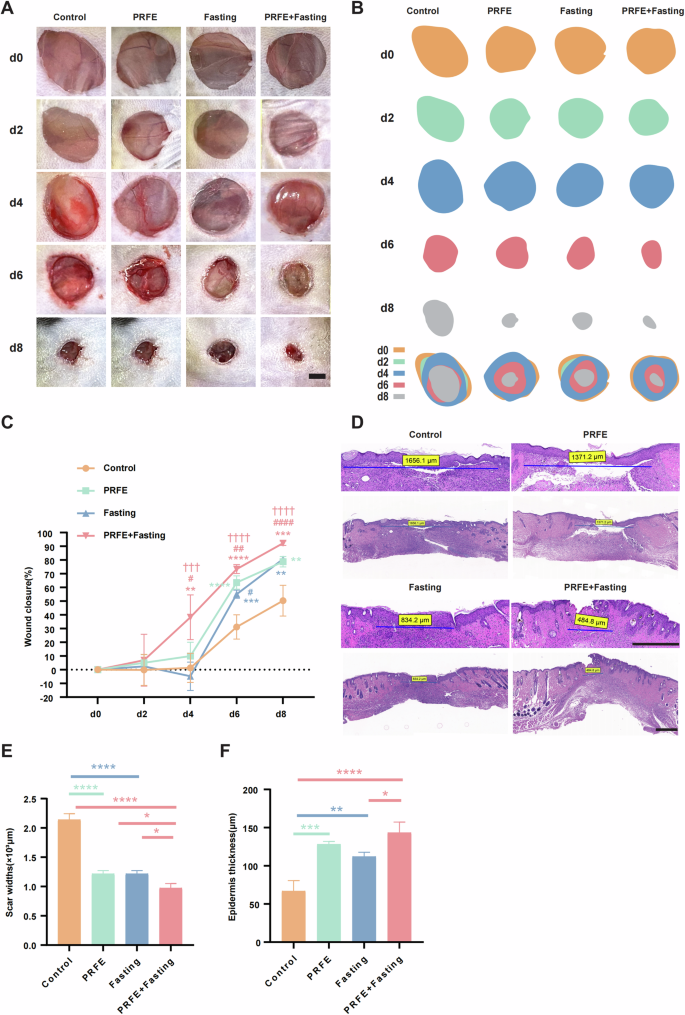

To evaluate the impact of Intermittent Fasting and PRFE Combination Therapy on diabetic wound healing, and further compare its efficacy with individual therapy to highlight the superiority of the combined therapy, we divided diabetic mice into four groups after creating wounds: Control group, PRFE group, Fasting group, and PRFE+Fasting group (Fig. 1C). From representative wound healing images of each group, it is apparent that the wound area noticeable decreased compared to the Control group at day 8, irrespective of the therapy employed (Fig. 2A). By extracting and superimposition individual wound images, we gain a more intuitive understanding of the varying degrees of wound healing among the therapy groups (Fig. 2B). To facilitate a fair comparison among the different therapy groups, we computed wound closure rates. In Fig. 2C, starting from day 4, the PRFE+Fasting group demonstrated a statistically significant disparity in wound closure rates compared to any other group. The PRFE group exhibited a swifter wound closure rate than the Fasting group from day 4 to day 8. However, on day 8, both groups reached nearly identical closure rates.

A Representative gross images of diabetic wounds in mice from Control group, PRFE group, Fasting group and PRFE+Fasting group at days 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8. Scale bar = 2 mm. B Illustrations depicting the wound healing process in A. C Wound healing rates in each group at different time points. n = 7 per group. D H&E staining of diabetic wound at day 8. Scale bar = 500 μm. E Widths of scars and F thickness of the epidermis. n = 3 per group. C Two-way ANOVA combined with Bonferroni post hoc test. E, F One-way ANOVA combined with Bonferroni post hoc test. Data are plotted as mean ± SD. C *P < 0.05 vs. Control group, #P < 0.05 vs. PRFE group, †P < 0.05 vs. PRFE+Fasting group. C, E, F: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

To ascertain the reliability of wound width measurements, we obtained histological sections tangent to the wound area. Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE) staining revealed that all therapy approaches were effective in reducing scar widths compared to the Control group. Notably, the combination therapy exhibited a significantly stronger effect relative to any individual therapy (Fig. 2D). Through measuring the re-epithelialization thickness in the scar tissue region, we observed a substantial impact of the combination therapy, followed by the PRFE group, and lastly the Fasting group, all of which showed significant differences compared to the Control group (Fig. 2E, F).

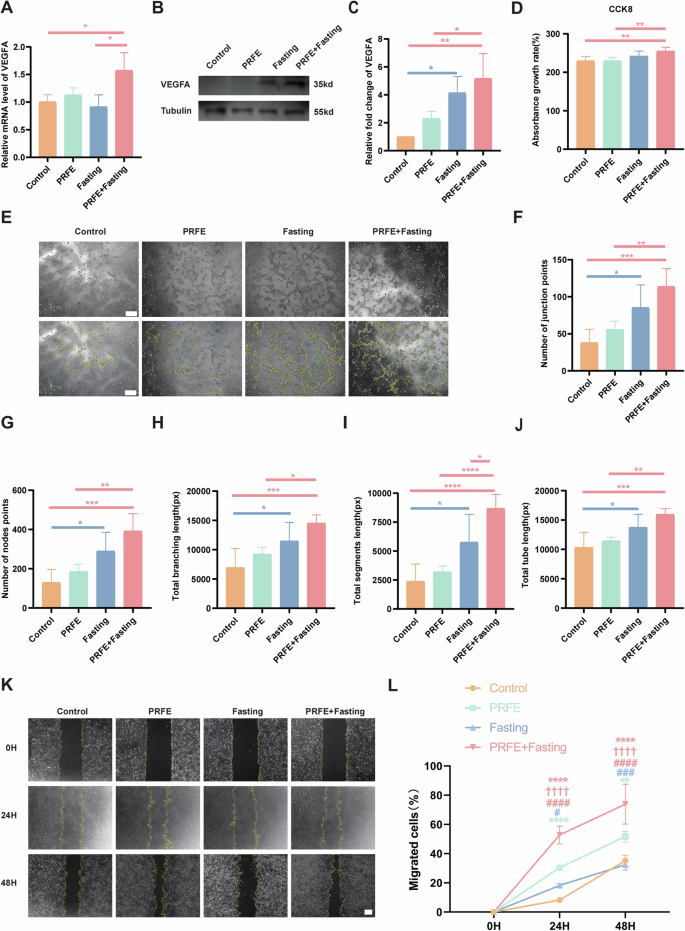

Intermittent fasting and PRFE combination therapy promote proliferation, tube formation, angiogenesis, and migration of endothelial cells

At the cellular level, we conducted grouping into control, PRFE, Fasting, and PRFE+Fasting, as well (Fig. 1B). For further investigation, We selected VEGFA, a classical pro-angiogenic gene, and utilized qRT-PCR to reveal significant upregulation of VEGFA in the combination therapy (Fig. 3A) [17]. WB further confirmed the increased expression of VEGFA at the protein level through the combination therapy (Fig. 3B, C). The Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay revealed a significant enhancement in the proliferation of Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) when subjected to combination therapy, surpassing the PRFE treatment alone. Conversely, individual therapy applied to HUVECs did not yield noteworthy variations compared to the Control group (Fig. 3D).

A qRT-PCR analysis of the expression levels of VEGFA target gene in HUVECs in Control group, PRFE group, Fasting group and PRFE+Fasting group. n = 3 per group. B Representative western blotting and C relative quantitative analysis of VEGFA in HUVECs in each group. The densitometric are normalized by α-tubulin. n = 3 per group. D CCK-8 analysis of the proliferation of HUVECs at 24 h subjected to the specified groups. n = 5 per group. E Tube formation assay of HUVECs in different groups. Scale bar = 100 μm. Semi-quantification analysis of F number of junction points, G number of nodes points, H total branching length, I total segments length, and J total tube length in different groups. n = 5 per group. K Representative images of scratch wound healing assay of HUVECs in different treatment groups and L the percentages of migration areas. Scale bar = 200 μm. n = 3 per group. A, C, D, F–J One-way ANOVA combined with Bonferroni post hoc test. L Two-way ANOVA combined with Bonferroni post hoc test. Data are plotted as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 vs. Control group, #P < 0.05 vs. PRFE group, †P < 0.05 vs. PRFE+Fasting group. For (A, C, D, F–J, L): *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

The Fasting group and the PRFE+Fasting group demonstrated notable development of multiple tube-like formations within HUVECs, indicative of angiogenesis initiation. The observed level of significance in the PRFE+Fasting group compared to the Control group is significantly higher than that observed in the Fasting group compared to the Control group. Additionally, consistent with our previous research, the standalone PRFE irradiation did not contribute to angiogenesis. These conclusions are evident from both representative images of tube formation and quantitative data relating to the number, length, and branching points of tubes (Fig. 3E–J).

In the scratch wound healing assay, both the PRFE group and the PRFE+Fasting group demonstrated notably increased migration when compared to the Control group at 24 h. Importantly, the PRFE+Fasting group exhibited migration levels surpassing those of the remaining three groups. Nevertheless, the Fasting group did not exhibit a noteworthy benefit in terms of migration. The observed trend in the PRFE and PRFE+Fasting group at 48 h exhibited similarity to that observed at 24 h. Moreover, it was noted that the PRFE group displayed a significant rise in migration in contrast to the Fasting group at this specific juncture (Fig. 3K, L).

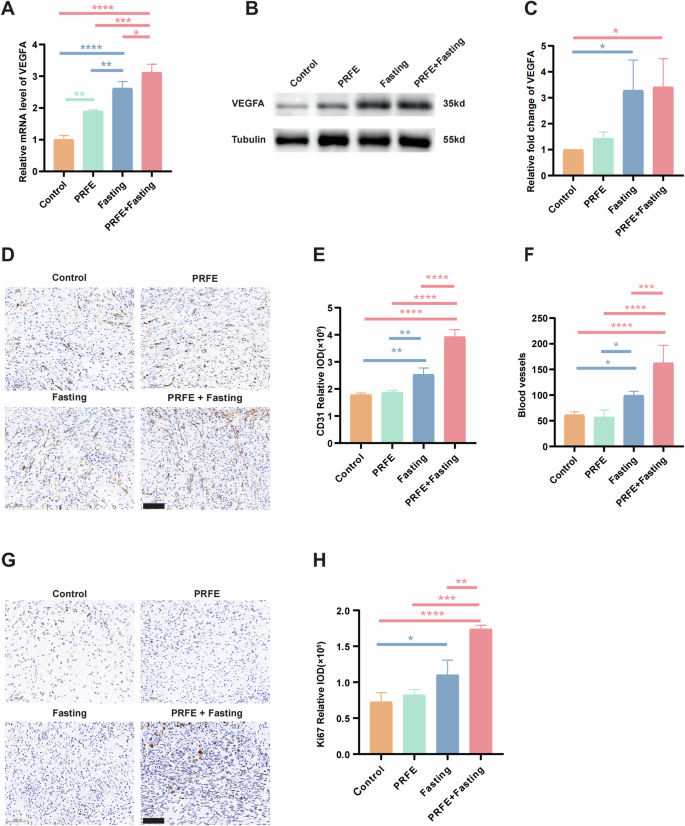

Intermittent fasting and PRFE combination therapy promotes proliferation, tube formation, and angiogenesis in the wound areas

Subsequently, we tested the effects of intermittent fasting and PRFE treatment on proliferation and tube formation in the wound areas of diabetic mice. Likewise, this part of the study commenced with the utilization of qRT-PCR to unveil the gene expression of VEGFA in the skin tissues of mice. The graph illustrates notable distinctions between the PRFE group and the Control group, with even more particularly evident in the comparison of the Fasting group and PRFE+Fasting group to the Control group individually. Upon comparing the three therapy groups, the Fasting group displayed a more substantial increase in gene expression compared to the PRFE group. Remarkably, the PRFE+Fasting group demonstrated a significantly greater enhancement than the PRFE group, representing the most prominent effect (Fig. 4A). Afterword, WB were undertaken to evaluate the influence of various therapy on the protein-level expression of VEGFA. The figure provides a visual depiction indicating that both the Fasting group and the PRFE+Fasting group exhibited a comparable upregulation in VEGFA protein expression, whereas the distinctiveness of the PRFE group was no longer discernible (Fig. 4B, C). To further validate the angiogenesis-promoting capability of VEGFA in our combined therapy in promoting angiogenesis, we utilized inhibitors to antagonize VEGFR2. By reducing the active receptors of VEGFA [18], we explored the regulatory role it plays in enhancing angiogenesis in the combined therapy. The administration of a VEGFR2 inhibitor(SU5408, HY-103002, MCE, USA) within the dual therapy group led to a significant decrease in tube formation abilities (please refer to Supplementary Fig. 1A–F). This reaffirms the role our combined therapy plays in promoting angiogenesis through the VEGF signaling pathway.

A qRT-PCR analysis of the expression levels of VEGFA target gene in mice wounds in Control group, PRFE group, Fasting group and PRFE+Fasting group. n = 3 per group. B Representative western blotting and C relative quantitative analysis of VEGFA in whole-cell protein extracts from mice wounds in different treatment groups. The densitometric are normalized by α-tubulin. n = 3 per group. D Representative immunohistochemical CD31 staining images and E relative IOD of CD31 expressions of mice wounds in different treatment groups. Scale bar = 100 μm. n = 3 per group. F The quantification of CD31-stained blood vessels in the wound sites. n = 5 per group. G Representative immunohistochemical staining images and H The relative IOD of Ki67 expressions of mice wounds in different treatment groups. Scale bar = 100 μm. n = 3 per group. A, C, E, F, H One-way ANOVA combined with Bonferroni post hoc test. Data are plotted as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Evidently, an increase in CD31-positive cells was macroscopically observed in the Fasting group and PRFE+Fasting group (Fig. 4D). Quantitatively, the PRFE+Fasting group exhibited a considerably higher expression of CD31-positive cells relative to any other group, followed closely by the Fasting group. Conversely, the PRFE group exhibited no noticeable discrepancy (Fig. 4E). Regarding the quantification of blood vessels formation, the prominent hierarchy among these four groups remained unchanged. However, the level of statistical significance among the groups slightly decreased (Fig. 4F).

In the context of tissue level in mice, both the Fasting group and PRFE+ fasting group demonstrated a higher occurrence of proliferating cells at the wound sites in comparison to the remaining two groups. The PRFE+Fasting group elicited a more markedly elevated level of proliferation in cutaneous cells (Fig. 4G, H).

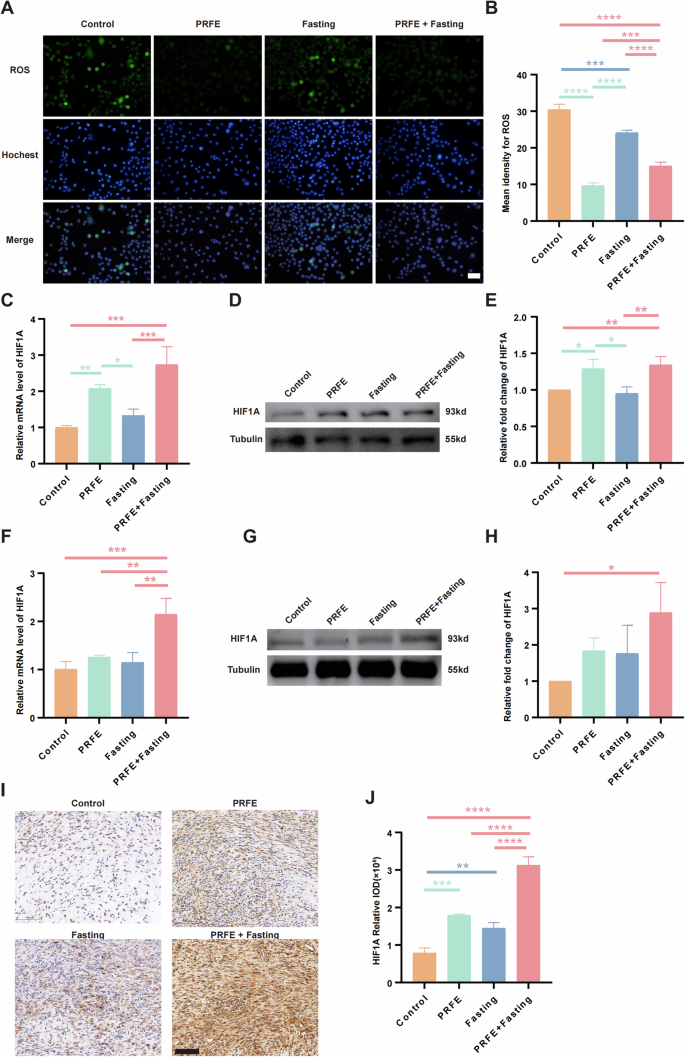

Intermittent fasting and PRFE combination therapy suppresses oxidative stress response in diabetic wounds by enhancing the expression of HIF1a

We employed the 2’,7’-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) probe to assess the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within HUVECs across the various therapy groups. The outcomes were quantified by determining the mean intensity. HUVECs treated with PRFE exhibited a significant decrease in mean fluorescence intensity, indicating a decrease in ROS presence. Similarly, intermittent fasting intervention resulted in a decline in ROS levels. The combination therapy showcased a ROS diminishment level that lay within the spectrum between the separate impacts of PRFE and intermittent fasting (Fig. 5A, B).

A Representative fluorescence images and B quantification showing local ROS levels of HUVECs in the Control group, PRFE group, Fasting group, and PRFE+Fasting group. Scale bar = 100 μm. C qRT-PCR analysis of the expression levels of HIF1A target gene in HUVECs in different groups. n = 3 per group. D Representative western blotting and E relative quantitative analysis of HIF1A in HUVECs in each group. The densitometric are normalized by α-tubulin. n = 3 per group. F qRT-PCR analysis of the expression levels of HIF1A target gene in mice wounds in each group. n = 3 per group. G Representative western blotting and H relative quantitative analysis of HIF1A in whole-cell protein extracts from mice wounds in different treatment groups. The densitometric are normalized by α-tubulin. n = 3 per group. I Representative immunohistochemical staining images and J the relative IOD of HIF1A expressions of mice wounds in different treatment groups. Scale bar = 100 μm. n = 3 per group. B, C, E, F, H, J One-way ANOVA combined with Bonferroni post hoc test. Data are plotted as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

The PRFE+Fasting group demonstrated pronounced upregulation of HIF1A expression at both the genetic and protein levels, regardless of whether the experiments were conducted in vitro or in vivo. In contrast, the PRFE group only showed appreciable enhancement solely in vitro conditions, whereas discernible variations were absent in the Fasting group. Upon isolated examination, focusing on HUVECs, the utilization of qRT-PCR and WB unveiled noteworthy distinctions in both the PRFE group and PRFE+Fasting group as compared to the other two groups, yet the degree of upregulation in the PRFE group appeared a slightly reduced magnitude when juxtaposed against the combination therapy (Fig. 5C–E). By evaluating cutaneous wound sites in diabetic mice, the PRFE+Fasting group exhibited a substantial increase in gene expression when compared to the other three groups (Fig. 5F), while at the protein level, significant enhancement was evident only relative to the Control group (Fig. 5G, H). IHC staining of HIF1A at the wound site further confirmed an elevation in HIF1A expression through treatment (Fig. 5I, J).

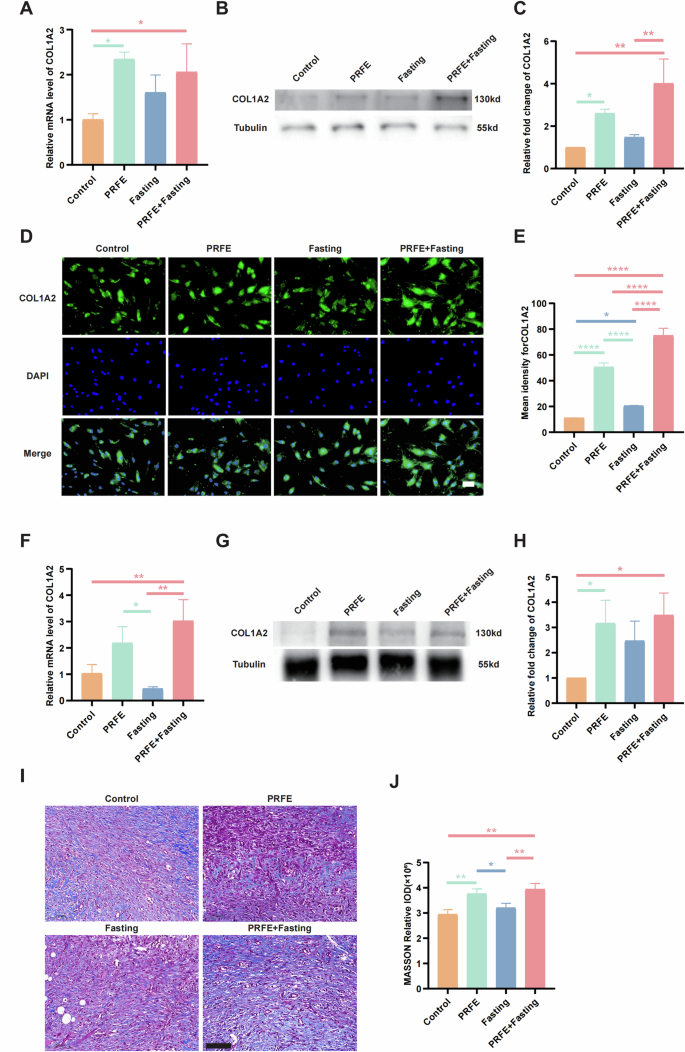

Intermittent fasting and PRFE combination therapy promote type I collagen expression to enhance fibrous formation in diabetic wounds

The process of fibrogenesis plays a pivotal role in the discussion surrounding wound healing in individuals with diabetes. We investigated the gene and protein expression of collagen type I alpha 2 (COL1A2) in human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs). We used IF staining to visually illustrate the effects of intermittent fasting and PRFE treatment on this phenotype. Gene expression analysis via qRT-PCR revealed a noteworthy increase in COL1A2 in both the PRFE group and the PRFE+Fasting group (Fig. 6A). Correspondingly, WB yielded comparable statistical differences, with the PRFE+Fasting group demonstrating higher levels of protein expression and a clear distinction from the Fasting group (Fig. 6B, C). In the IF images, there was even a discernible increase in the Fasting group relative to the Control group. Overall, the expression of COL1A2 in the PRFE+Fasting group surpassed all other groups, followed by the PRFE group, while the Fasting group only showed improvement over the Control group (Fig. 6D, E).

A qRT-PCR analysis of the expression levels of COL1A2 target gene in HDFs in Control group, PRFE group, Fasting group, and PRFE+Fasting group. n = 3 per group. B Representative western blotting and C relative quantitative analysis of COL1A2 in HDFs in each group. n = 3 per group. D Representative immunofluorescent staining for COL1A2 in HDFs in each group and E the mean intensity for COL1A2-positive areas. Scale bar = 100 μm. n = 3 per group. F qRT-PCR analysis of the expression levels of COL1A2 target gene in mice wounds in each group. n = 3 per group. G Representative western blotting and H relative quantitative analysis of COL1A2 in whole-cell protein extracts from mice wounds in different treatment groups. n = 3 per group. I Representative immunohistochemical staining images and J the relative IOD of COL1A2 expressions of mice wounds in different treatment groups. Scale bar = 100 μm. n = 3 per group. C, H The densitometric are normalized by α-tubulin. A, C, E, F, H, J One-way ANOVA combined with Bonferroni post hoc test. Data are plotted as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Analogous investigations were conducted in diabetic mouse wound regions to assess variations at the genetic and protein levels, showing parallels with observations in HDFs (Fig. 6F–H). Additionally, Masson’s trichrome staining was employed to evaluate collagen deposition density and distribution in wound tissues, revealing enhanced uniformity and density of collagen fibers in both the PRFE group and PRFE+Fasting group in contradistinction to the Control and Fasting groups (Fig. 6I, J). Our findings in the PRFE group align seamlessly with previous experiments conducted by our team [4].

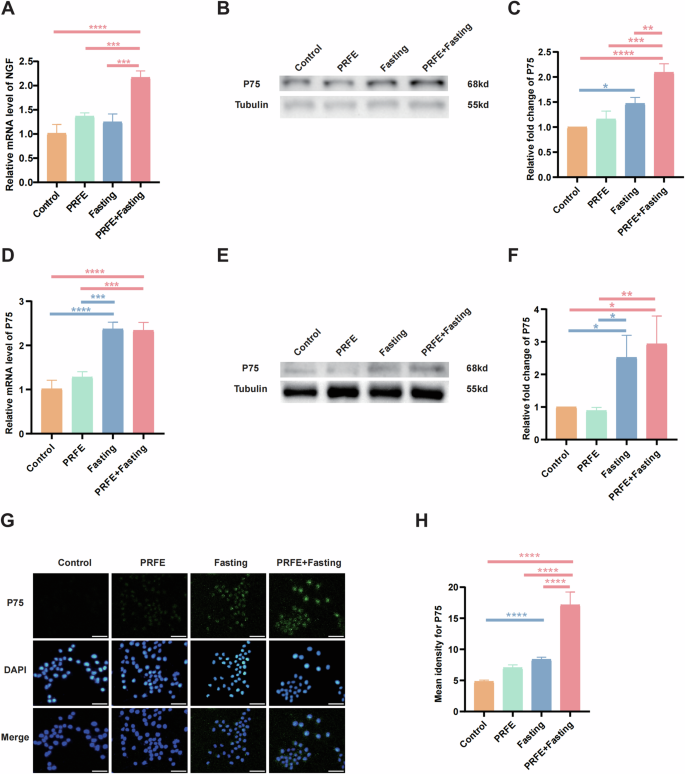

Intermittent fasting and PRFE combination therapy promote the expression of NGF and P75 in vitro

We observed a robust rise in NGF gene expression in the HDFs of the PRFE+Fasting group (Fig. 7A). Subsequently, we investigated the expression of P75 in SCs. The gene expression of P75 in mice was found to be elevated in the Fasting group and PRFE+Fasting group, in comparison to the Control group and PRFE group (Fig. 7D). Via WB analyses, discernible elevation in protein expression was observed in both the PRFE+Fasting and Fasting groups, evident in both SCs and diabetic mice wound sites (Fig. 7B, E). The PRFE+Fasting group demonstrated markedly higher levels in SCs compared to all other groups, while in the skin tissues of diabetic mice, the statistical significance of PRFE+Fasting group was only evident for Control and PRFE group. Instead, the Fasting group exhibited statistical differences only relative to the Control group in SCs, but in diabetic mouse skin, it showed significant differences compared to both the Control and PRFE groups (Fig. 7C, F). To delve further into the phenotype, we conducted IF staining of P75 on SCs, and the staining results corroborated the inter-group disparities observed in WB (Fig. 7G).

A qRT-PCR analysis of the expression levels of NGF target gene in HDFs in Control group, PRFE group, Fasting group, and PRFE+Fasting group. n = 3 per group. B Representative western blotting and C relative quantitative analysis of P75 in SCs in each group. D qRT-PCR analysis of the expression levels of P75 target gene in mice wounds in each group. n = 3 per group. E Representative western blotting and F relative quantitative analysis of P75 in mice wounds in different treatment groups. n = 3 per group. G Representative immunofluorescent staining for P75 in HDFs in each group and H the mean intensity for P75-positive areas. Scale bar = 50 μm. n = 3 per group. C, F The densitometric are normalized by α-tubulin. A, C, D, F, H One-way ANOVA combined with Bonferroni post hoc test. Data are plotted as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

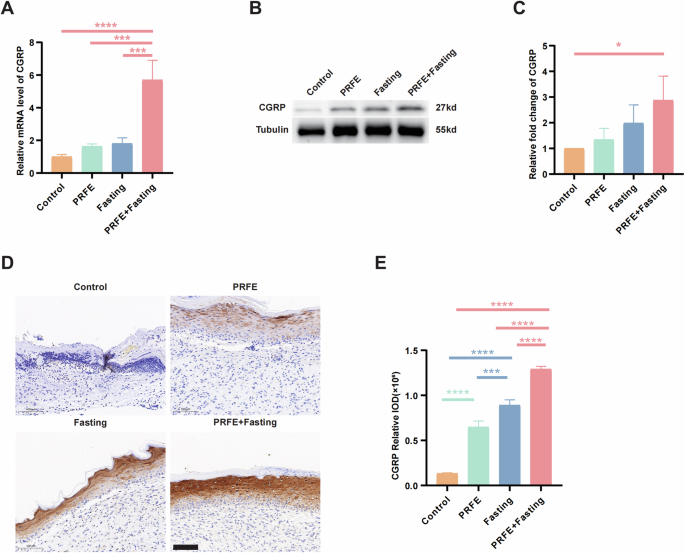

Intermittent fasting and PRFE combination therapy promotes sensory nerve growth in vivo

To assess the effectiveness of intermittent fasting and PRFE in promoting the development of sensory nerves, we extracted RNA and protein from the wounds of diabetic mice for further examination. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) functions as a biomarker for sensory nerve presence [19]. Through qRT-PCR analysis, it was observed that the PRFE+Fasting group displayed notably elevated CGRP expression levels surpassing the other three groups (Fig. 8A). Likewise, in WB, this group consistently exhibited the highest expression levels (Fig. 8B, C). IHC staining of CGRP indicated that sensory nerves are predominantly localized in the superficial layers of the wound healing region (Fig. 8D). The PRFE group showed a discernible augmentation compared to the Control group, whereas the Fasting group existed more pronounced levels, and the PRFE+Fasting group demonstrated the most elevated expression (Fig. 8E).

A qRT-PCR analysis of the expression levels of CGRP target gene in mice wounds in Control group, PRFE group, Fasting group, and PRFE+Fasting group. n = 3 per group. B Representative western blotting and C relative quantitative analysis of CGRP in whole-cell protein extracts from mice wounds in different treatment groups. The densitometric are normalized by α-tubulin. n = 3 per group. D Representative immunohistochemical staining images and E the relative IOD of CGRP expressions of mice wounds in different groups. Scale bar= 100 μm. n = 3 per group. A, C, E One-way ANOVA combined with Bonferroni post hoc test. Data are plotted as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Conclusion

The contribution of intermittent fasting, PRFE, and their synergistic application serves to enhance diabetic wound healing. This research delved into mechanisms for promoting wound healing across seven aspects: proliferation, tube formation, angiogenesis, migration, oxidative stress, fibrogenesis, and sensory nerve growth (Table 2). When evaluating the same phenotype, if the statistical disparities demonstrate comparable general trends but vary in terms of significance, priority is given to the outcomes obtained from animal experiments, as they provide a closer representation of the authentic physiological conditions of the organism. Intermittent fasting exhibited advantages over the PRFE treatment in enhancing proliferation, tube formation, angiogenesis, and sensory nerve growth. Conversely, PRFE excelled in facilitating migration, attenuating oxidative stress, and augmenting fibrogenesis.

The intermittent fasting and PRFE combination therapy yielded greater efficacy in enhancing diabetic wound healing when compared to therapy in isolation. The combined treatment leveraged the strengths of both individual treatments in promoting migration, inhibiting oxidative stress, and enhancing fibrogenesis. Additionally, It manifested a synergistic effect, surpassing the additive effect of the individual treatments, in promoting proliferation and facilitating the formation of blood vessels and sensory nerve growth.

Discussion

This study focuses on investigating non-pharmaceutical and non-invasive therapeutic approaches for promoting diabetic wound healing and avoiding the potential adverse effects of medication. The research provides an objective and robust demonstration that the combined therapy of intermittent fasting and PRFE substantially improves diabetic wound healing from the perspectives of angiogenesis, fibrogenesis, and sensory nerve growth. The combined therapy addresses the limitations of individual therapies and amplifies their advantages, thus representing a valuable complementary therapeutic strategy.

PRFE is recognized as a physical therapeutic modality that can enhance wound healing, as supported by clinical evidence indicating its efficacy in promoting wound closure, particularly in recalcitrant wounds [3]. Its application shows potential benefits for diabetic foot ulcers [20]. In the context of diabetic wounds, based on prior research within our group, PRFE can be characterized by predefined waveform parameters that are adjustable to ensure consistent delivery while treating wounds without the need for dressing removal. The primary mechanisms through which PRFE operates involve the stimulation of cellular proliferation, granulation tissue formation, and collagen deposition, all contributing to the advancement of wound healing at injury sites [4]. However, its impact on angiogenesis is negligible, posing a significant challenge. Without a robust angiogenic response, the facilitated healing process may be superficial and lack the essential vascular support necessary for comprehensive wound healing. This study addresses the limitations of PRFE therapy and enhances its therapeutic efficacy.

Previous research on intermittent fasting has demonstrated its notable impact on diabetic wound healing. It can enhance re-epithelialization and dermal regeneration while reducing scar formation. Additionally, it stimulates the growth of new blood vessels in the vicinity of the wound by activating resident endothelial cells [5]. Other research indicates that intermittent fasting can also improve insulin sensitivity, the responsiveness of β-cells, blood pressure, oxidative stress, and appetite [21]. Moreover, it has been observed to improve blood glucose levels in diabetic rodents [22]. In terms of neural implications, intermittent fasting has been shown to alleviate diabetes-induced cognitive impairments [23]. Nevertheless, despite the abundance of evidence associating intermittent fasting with diabetes, existing research on wound healing in diabetic individuals still exhibits certain constraints. Specifically, there is a conspicuous dearth of studies investigating the precise impacts of intermittent fasting on facilitating wound healing, particularly within the realm of neurogenesis.

This article consists of two logical threads: macroscopic comparisons and pathway exploration. In the aspect of macroscopic comparisons, we not only formed a treatment group that received combined therapy but also established separate therapy groups to facilitate a comparative evaluation of treatment outcomes. This methodology played a pivotal role in elucidating the indispensability of the combined treatment, showcasing its efficacy beyond mere additive effects and, instead, mutually augmenting to attain an elevated level of wound healing. Regarding pathway exploration, we delved into the potential mechanisms of the combined therapy through the P75/HIF1A/VEGFA pathway, with the incorporation of neuronal factors into our study. Our research began with an examination of the performance of combination therapy in promoting diabetic wound healing in the realms of angiogenesis, oxidative stress, and nerve growth. In investigating angiogenesis, we found elevated expression of VEGFA in endothelial cells—an essential actor in vessel formation. Its overexpression in specific situations may indicate enhanced potential for vessel formation—a crucial process for wound healing [6]. Simultaneously, in phenotype checking for oxidative stress, we detected an increased expression of HIF-1α, a crucial player in oxidative stress response, in the HUVECs. Previous studies have substantiated the suppressive impact of elevated blood glucose levels on HIF-1α [8]. HIF-1α, one of its key roles is to stimulate the production of VEGFA [9]. Thus, it’s plausible that HIF-1α could provoke the upregulation of VEGFA. Interestingly, while studying nerve growth, we noticed an increase in the expression of P75, a neurotrophin receptor, within SCs. P75 holds the role of sustaining the vitality of sensory neurons [12]. Literature indicates that HIF-1α is a primary target of p75 [10], thus, we may postulate that P75 regulates the HIF-1A/ VEGFA pathway. This points towards a possible mechanistic pathway beginning with overexpression of p75 in SCs, potentially triggering upregulation of HIF-1A, consequently leading to overexpression of VEGFA in endothelial cells. This process may suggest the presence of a neuron-enhanced pathway for vessel formation. The association between the nervous system and oxidative stress is indicated by the linkage from P75 to HIF1A, while the connection from HIF1A to VEGF signifies the relationship between oxidative stress and angiogenesis [24, 25]. Existing research has indicated the inseparable relationship between nerves and blood vessels [26]. The relationship between nerves and blood vessels is fundamentally intertwined due to their common characteristics and the manner in which they interact within the body. This interaction becomes quite manifest in their development and when the body must respond to injury or illness. For example, during angiogenesis, nerves often grow alongside these new structures, demonstrating their interconnected relationship [27]. Similarly, in response to injury, an increase in signals from the nervous system can stimulate the dilation and formation of blood vessels to provide necessary nutrients for healing and repair. For instance, in the superior cervical ganglia of newborn rats, capillary sprouting is promoted by NGF via the release of VEGF [28]. Additionally, vascular conditions substantially influence neural physiology, for example, a decrease in blood flow or ischemia can directly affect the conduction speed and integrity of the peripheral nervous system [29]. The upregulation of P75 expression is positively correlated with HIF1A [30], which was consistently observed in our experiments. Furthermore, we assessed the levels of NGF, a factor that interacts with the P75 receptor and contributes to re-innervation [31]. Previous studies have already demonstrated that modulating the HIF1A/VEGFA signaling pathway accelerates the healing of diabetic foot ulcers [32]. We further substantiated that the combined therapy of intermittent fasting and PRFE can effectively augment the healing process of diabetic wounds by activating this particular mechanism. This inclusion highlights a potential avenue for exploring the role of neurogenic angiogenesis. Considering the complex intercellular communication observed, our subsequent logical progression involves co-culturing diverse cell types to delve deeper into the molecular interactions. This approach would establish a comprehensive framework encompassing the cells and pathways, enhancing the rigor and coherence of this research.

It is worth mentioning that during the experimental procedure, we encountered three intriguing phenomena. During the modeling process, we noticed that the wound area of the Control and Fasting groups expanded on day 4, surpassing the initial wound size. Following the creation of the wounds and adherence to sterile conditions, we applied surgical dressings. By day 4, a majority of these dressings had spontaneously detached. Consequently, owing to the robust elasticity of mouse skin, the surrounding tissues may have stretched the wound area. Meanwhile, the wound-healing process might have lagged behind the degree of stretching, leading to the occurrence of this phenomenon.

The variation in gene and protein expression levels at a specific molecule, such as VEGFA, can be ascribed to inherent disparities in the translational mechanism. Moreover, the differentiation in gene and protein expression between murine and cell models can be attributed to the coexistence of diverse cellular constituents within cutaneous tissues rather than a single-cell type. This divergence accounts for the differences between in vivo and in vitro experiments.

Intermittent fasting and PRFE radiation therapies each have strengths and limitations. Our data indicates that intermittent fasting has no effects on alleviating oxidative stress and promoting fibrogenesis, contrary to combinational therapy, demonstrating its superior potential to compensate for and even counteract the deficiencies of individual therapies.

Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of our experiments. We are unable to identify specific cell subtypes and rare cell populations and investigate processes such as cell state transitions and development. To address this constraint, we plan to conduct single-cell sequencing on the processed samples in subsequent experiments [33]. This methodology entails high-throughput sequencing of the transcriptomes of individual cells, unveiling the diversity and heterogeneity of gene expression levels among different cell types. Through this approach, we anticipate further elucidating the mechanisms underlying the combined therapy’s impact on diabetic wound healing. This will not only offer additional targets for future research but also provide valuable insights. Furthermore, the utilization of primary cells extracted directly from animal skin tissue, as opposed to cell lines used in our in vitro experiments, would provide a more direct and accurate observation of the mechanisms responsible for the enhanced diabetic wound healing effect of the combined therapy [34]. However, our experimental approach’s advantage lies in its non-species-specific nature, implying that the combined treatment method is broadly applicable and its mechanisms are likely universally present. In our research, we use male mice, consistent with previous literature because some studies have shown that male C57BL/6 mice are more prone to high-fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance [35,36,37], which are key factors in the occurrence of type 2 diabetes. Therefore, for scientific reasons, we used C57BL/6 male mice for this research. However, this decision does not exclude the importance of considering gender differences in future research.

The close relationship between intermittent fasting and metabolism has been established through various studies which demonstrate that intermittent fasting can reduce weight gain [38], lower fasting blood glucose [39], and decrease fat content in the body [40], indicating the significant impact of intermittent fasting on ketosis and glucose states [41]. The interaction between fasting and the metabolic network is an important direction for future research.

In conclusion, our study underscores that the combined therapy of intermittent fasting and PRFE exerts a synergistic effect on diabetic wound healing, primarily by enhancing angiogenesis, fibrogenesis, neurogenesis, and attenuating oxidative stress. The evident involvement of the P75/HIF1A/VEGFA axis in mediating these effects further supports our findings.

Responses