Non-replicative herpes simplex virus genomic and amplicon vectors for gene therapy – an update

Introduction

HSV-1 is a widespread neurotropic enveloped human pathogen with a worldwide prevalence of about 67% [1] that can establish two very different types of infections. Lytic, or productive infection of wildtype (wt) HSV-1 takes place most generally in epithelial cells, while latent, persistent infection, generally occurs in sensory neurons, although the virus can also establish latency in neurons of the autonomic nerve system [2, 3]. It should be noted however that productive infection can also take place in sensory neurons, for example during reactivation from latency. Two types of vectors can be derived from HSV-1: defective, non-replicative HSV-1 vectors, generally used in gene therapy of hereditary or acquired diseases, and attenuated, replication-selective vectors, commonly used as oncolytic vectors, or cancer virotherapy [4]. Both vector types are non-integrative and have already reached the clinic. Non-replicative vectors can be further subdivided into two classes: non-replicative HSV-1 genomic vectors (nrHSV-1), which carry a modified virus genome and are deleted in at least one essential immediate-early gene, and amplicon vectors, or amplicons, the genomes of which do not carry any viral lytic genes and are therefore helper genome-dependent vectors [5]. This review will focus on the main features of both types of non-replicative vectors. After a long lapse with important preclinical developments but without clinical trials, this situation has recently changed, at least with nrHSV-1 vectors, and clinical trials have resumed. Although there have not been any clinical trials yet with amplicons, these vectors deserve attention because they possess exceptional features that potentially make them a vector system of choice with unique properties for numerous gene therapy or cancer applications [6], once the difficulty of producing helper-free amplicons in large quantities and with cGMP compliant procedures, can be resolved.

HSV-1 molecular and cell biology

First, it is useful to briefly summarize the main aspects concerning the molecular and cellular biology of HSV-1. The viral genome is a linear double-stranded DNA molecule with a size of about 152 kbp that encodes more than 80 genes and several miRNAs [7]. This genome is contained in an icosahedral capsid, which is coated with tegument, a layer of at least 20 proteins important for gene expression and virion assembly, and a lipid envelope acquired from the infected host cell and studded with a dozen different virus-encoded glycoproteins [7]. The envelope glycoproteins are involved in cell attachment and virus entry, as well as in virus spread and immune evasion. Several of them (gB, gD, gH, and gL), are necessary for infection, interacting with Nectin1, the main cellular receptor, and inducing fusion of virus and cellular membranes [8, 9]. It may be noted however that the virus can use other cellular receptors for entry, such as HVEM, even in neurons [10]. Following fusion, the outer tegument proteins and capsid dissociate, with the capsid being retrogradely transported via microtubule-associated motor proteins coupled with some inner tegument proteins [11] to the nuclear membrane, from where the viral genome is released from the capsids to enter the nucleus [12]. Tegument proteins of incoming virus particles exert their effects immediately following entry. Some of them, such as infected cell protein (ICP) 0, counteract cellular antiviral intrinsic or innate defenses while others, such as ICP4 or the virion protein (VP) 16, promote gene expression [13, 14] while also serving a structural role in virus morphogenesis in the case of VP16. Other tegument proteins participate in the retrograde transport of the viral capsids, such as the protein encoded by gene UL37 [11]. Following the injection of the large linear viral DNA genome into the cell nucleus, the DNA takes a circular configuration. Then, depending on the type of infected cell, the HSV-1 life cycle will establish either a lytic or a latent infection.

During a lytic productive infection in epithelial cells, a temporal cascade of gene expression occurs, characterized by the successive synthesis of immediate-early (IE or α), early (E or β), and late (L or γ) viral proteins [3, 7]. Most IE proteins (ICP0, ICP4, ICP22, and ICP27), the expression of which is induced by VP16, are regulatory proteins that counteract the innate cellular defenses and activate the expression of the early and late genes. VP16 forms a ternary complex with a cellular protein known as host cell factor (HCF) and the transcription factor octamer-binding protein 1 (OCT1). This ternary complex binds to IE promoters and recruits transcription factors that activate IE gene expression [15]. ICP4 is the major viral transactivator, required for all subsequent viral gene expression through its association with cellular transcription factors and adapter proteins [16,17,18]. ICP0 is an E3-ubiquitine ligase that marks cellular proteins for proteolysis. It increases the expression of viral genes both by inducing the degradation of cellular proteins involved in the inhibition of viral genes, such as PML and other ND10-associated proteins [19] and by inhibiting chromatin-interacting proteins that participate in epigenetic silencing of the virus genome, such as histone deacetylases (HDACs) [20] and the Rest/coRest-HDAC repressor complex [21, 22]. ICP27 regulates viral gene expression through several mechanisms, including splicing, 3′ processing, and mRNA export [23,24,25]. It plays a critical role in mediating host shutoff [26] and is required for the efficient incorporation of ICP0 and ICP4 into virions [27]. ICP22 plays several roles in the virus life cycle, including downregulation of cellular gene expression, upregulation of late viral gene expression, and inhibition of apoptosis [28]. Another IE protein, ICP47, also induced by VP16, is an inhibitor of human transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP), blocking MHC I antigen presentation and facilitating escape from adaptive immune responses [29]. Early proteins include the virus DNA polymerase, helicase/primase, virus origin DNA binding protein, and other proteins required for replication and packaging of the virus genome. The late proteins are structural proteins (capsid, tegument, envelope) involved in virion morphogenesis and cell exit [7], which is accompanied by cell death, generally between 12- and 20-h post-infection, depending on the multiplicity of infection (MOI) and the susceptibility of the infected cells.

In contrast to lytic/productive infection, following infection of sensory neurons through the neuron terminals and retrograde transport of virus capsids to the neuron nucleus in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) or the trigeminal ganglia (TG), the circularized virus genome will generally establish a latent infection. In this case, no IE proteins will be expressed or have a reduced half-life [30]. In the absence of IE proteins, the virus cannot counteract genome silencing nor induce expression of early and late genes, so that the expression cascade is not triggered, the virus genome will be epigenetically repressed by heterochromatin and will remain as a non-integrated silent nuclear extrachromosomal episome [31]. Only the LAT locus of the virus genome, which expresses a polyadenylated non-coding transcript approximately 8.3 kb in length, known as the primary latency-associated transcript (LAT), remains transcriptionally active during latency [32]. This is so likely because this region is bordered by two DNA insulator sequences that preserve this locus from DNA silencing [33] but also because this locus contains an enhancer in the 5′ end of the LAT transcript (the LAP2/LTE region) [34]. This region is enriched in hyperacetylated histone H3 during latency in DRG neurons and likely contributes to long-term expression [35].

Latency is in fact a very heterogeneous phenotype. A large series of observations have shown that following peripheral infection only a minority of neurons in the corresponding DRG contain nuclear virus episomes and that no more than 30% of these neurons express the LATs. Moreover, we know that in some neurons the virus can initiate a lytic infection, as demonstrated by the expression of lytic antigens, and that a fully latent phenotype is established only 2–3 weeks post-infection, with the extinction of the expression of virus antigens, coincident with the development of adaptative immune responses [3, 7, 31, 36]. Host immune responses and T-cell responses help to establish and regulate viral latency and reactivation [37, 38]. Deeper aspects of neuron infection have been investigated in recent years, leading to a better comprehension of fundamental aspects of latency, including the fact that different types of sensory neurons (Aδ, Aβ, C-type neurons) can vary in their susceptibility to infection and their abilities to stably express the LATs [39, 40]. Other studies have shown that the number of nuclear episomes can significantly vary in different neurons (from 1 to more than 100) [41] and that they can localize and establish interactions with different nuclear proteins and substructures, such as the ND10 bodies and centromeres, perhaps determining in part which episomes will be able to express the LATs and which will be fully silenced by association with repressive heterochromatin [42].

It is becoming increasingly clear that the above observations rely, at least in part, on the innate immune responses elicited not only by the infected neurons but also by the infected epithelial cells or fibroblasts that are innervated by the peripheral axon termini of sensory neurons. Following infection, the virus establishes an acute infection in epithelial cells or fibroblasts, where it undergoes productive replication, prompting a robust innate immune response [43]. Secretion of interferon (IFN) and other inflammatory cytokines by these cells have an impact on the fate of the virus genome in the innervating peripheral neurons which, although they express only low-level IFN, can sense and respond to immunostimulatory molecules [43, 44]. Given the abundance of immune signaling molecules, the differential response to infection even between neuronal subtypes, and the links between IFN and molecules such as PML or SP100, which form part of ND10 bodies, it is likely that innate and intrinsic antiviral cellular responses contribute to heterogeneity in HSV latency. For a recent review article on the connection between latency and innate immune responses, see [45].

Unfortunately, these topics have not been thoroughly investigated in the case of non-replicative HSV-1 vectors and we do not know precisely how they can impact on transgene expression in neurons. Moreover, the above observations are critical in designing vectors able to establish latent-like infection in non-neuronal cells without the deleterious effects of leaky lytic expression.

Non-replicative HSV-1 genomic vectors

Both nrHSV-1 and amplicon vectors inherit many of the features of the wildtype virus and leverage them to achieve their therapeutic goals. NrHSV-1 vectors are deficient in at least one essential function and can be efficiently produced only in complementing cells expressing the missing function(s). First-generation nrHSV-1 vectors were rendered non-replicative by eliminating the expression of the essential IE ICP4 protein. However, they displayed cytotoxicity in dividing cells due to the expression of other IE functions, mainly ICP0 and ICP27 [46]. These early studies introduced the notion that nrHSV-1 vectors could be cytotoxic and inflammatory, an outdated view that has persisted despite further engineering that progressively deleted other IE genes finally resulting in vectors functionally deficient in the expression of the whole set of IE genes [47, 48]. These last-generation vectors are fully non-toxic in infected cultured cells yet preserve robust and durable transgene expression when driven by adequate regulatory sequences and are protected from epigenetic silencing by DNA insulators. Moreover, these new-generation vectors show no evidence of cell toxicity or induction of inflammatory cell infiltrates following injection in animal models in vivo, including the CNS [47, 49]. It should be noted that the use of current complementing cell lines consistently results in a drop in vector titer, as compared with wtHSV-1. This is a major problem in the production of vectors, whether they be genomic or amplicon vectors, and efforts are being devoted in several laboratories to generate better-complementing cell lines.

Since HSV-1 is a true neurotropic virus, it is natural that first attempts to perform gene therapies using nrHSV-1 vectors, mainly in preclinical settings, addressed diseases or aberrant gene expression of peripheral neurons, thereby exploiting the many outstanding adaptations of HSV-1 to these neurons. These include (a) a high density of Nectin1 or other cellular receptors [10, 50], favoring vector infection and thus allowing for limited vector doses to reach efficacy, (b) the presence of tegument and capsid viral proteins that interact with microtubule-associated proteins [51, 52], allowing the capsids to be very efficiently and rapidly retrogradely transported along the axons up to the neuron nucleus, and (c) the natural establishment of latent infection in sensory neurons [2, 3], a condition in which, as above quoted, the vector genome is maintained as an extrachromosomal episome, with no insertional mutagenesis, and in which the full set of viral lytic genes expressing lytic functions is epigenetically repressed. Only some short regions of the virus genome, such as the LAT region, which are surrounded by neuron-specific DNA insulator motifs, and express no virus proteins, remain transcriptionally open and can be used to accommodate foreign transgenic DNA, providing long-term expression if adequate regulatory sequences are used [53]. Two other outstanding features of HSV-1 vectors are (d) the large DNA cargo that can be delivered by these vectors (more than 30-kbp for nrHSV-1 and up to about 150 kbp for amplicons) [4,5,6], and (e) the fact that the immune reactions against the virus are low since they are efficiently counteracted by incoming tegument viral proteins delivered into the cells [54]. This results in no rejection of virus particles or infected cells, no significant modification in the immune status of the receiving patient, no immune reaction precluding transgene expression, and above all, the possibility of redosing the vector several times at the same or different anatomic place [55, 56].

Gene therapy using nrHSV-1

Several nrHSV-1 vectors have intended to exploit one or more of these features, resulting in non-toxic vectors that can express transgenes in peripheral neurons in the long term. At the preclinical level, such vectors were used to successfully treat experimental animal models of neurogenic bladder overactivity [57, 58], neuropathic and inflammatory pain [59, 60], or neuropathies [61, 62]. Previous work also demonstrated that various PNS neuronal subtype promoters could drive transgene expression in the corresponding subset of DRGs following nrHSV injection into the bladder wall [63]. Based on these and other observations, one vector prototype (termed NP2) was used 15 years ago for the first clinical trial, to treat intractable cancer-related pain [64].

Gene therapy for cancer-related pain

This first clinical trial exploited the ability of HSV-1 vectors to express transgenes after establishing a quasi-latent infection in the DRG. A dose-escalating, phase 1 clinical trial of NP2 (NCT00804076), a nrHSV-1 vector expressing human proenkephalin (PENK) under the control of the strong but transient HCMV promoter inserted in both ICP4 loci, was conducted in terminal cancer patients with intractable focal pain [64]. NP2 was injected into the affected dermatomes, with the virus taken up by nerve terminals and transported to the DRG, where the vector institutes a persistent, quasi-latent state with PENK expression. No treatment-related serious adverse events were reported and no subject was seroconverted [64]. Pain relief was reported for the middle and high doses (10E8-10E9 plaque-forming units (pfu) per individual). This clinical trial showed for the first time that a nrHSV-1 vector expressing a therapeutic function from a quasi-latent genome in DRG could be safely and efficiently used in humans, which were the most important outcomes of this trial. A phase II trial (NCT01291901) was unfortunately discontinued for financial reasons.

Gene therapy for bladder diseases

We have previously demonstrated that an amplicon vector expressing the light chain of botulinum neurotoxin F (BoNT-F LC) was able to cleave the vesicular-associated membrane protein 2 (Vamp2) thereby inhibiting the secretion of vesicular-associated neurotransmitters [65]. Based on this and previous observations [57, 58], we generated a nrHSV-1 vector expressing BoNT-F LC, driven by the human version of the C-type sensory neuron-specific CGRP promoter (hCGRP), the EG110A vector. Following inoculation in the rat bladder wall, vector particles were retrogradely transported to the nucleus of C-type sensory neurons located in L6/S1 DRG, from where expression of BoNT-F LC transgene ablated synaptic activity of these neurons thereby inhibiting the abnormal reflex arc that is generated following spinal cord injury (SCI) or bladder irritation by capsaicin. This results in a decrease in the frequency of aberrant non-voiding bladder contractions in two models of rat bladder dysfunction, neurogenic detrusor overactivity (NDO) caused by SCI, and overactive bladder (OB), induced by capsaicin, without impacting on normal micturition or any other physiological parameter. Our EG110A vector received clearance from the FDA in June 2024 and an open-label phase 1b/2a clinical trial in SCI patients who suffer NDO is ongoing (NCT06596291). This trial therefore represents the first model leveraging the ability of nrHSV-1 vectors to stably express a transgene from a latent genome in the long term.

Gene therapy for severe skin diseases

Recently, an nrHSV-1 vector known as B-VEC (beremagene geperpavec, Vyjuvek™, or KB103) that expresses two copies of the COL7A1 gene driven by the strong HCMV promoter, was developed to treat recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB), a shattering skin disease resulting from collagen VII (C7) mutations impairing anchoring fibrils [66, 67]. Repeated doses of B-VEC were topically administered to freshly renewed skin in an attempt to treat the symptoms albeit without curing the disease. Unlike the NP2 or the EG110A studies, this trial exploited the ability of B-VEC to strongly express transgenes in superficial layers of the skin and to be readministered as many times as required due to the low immunogenicity of the vector. This trial is unprecedented and innovative in that the vector does not address the peripheral nerve system. Latency is therefore irrelevant in this trial and the fact that B-VEC expresses some toxic IE functions, such as ICP0 and ICP27, is well tolerated since skin cells are constantly being renewed. B-VEC also expresses IE ICP47, which inhibits antigen presentation and reduces immune recognition [67], facilitating multiple administrations [66].

A randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial (NCT03536143), matching wounds from RDEB patients receiving topical B-VEC or placebo repeatedly over 12 weeks, met primary and secondary objectives [66]. No grade 2 or above B-VEC-related adverse events, vector shedding, or skin immune reactions were noted [66]. A phase 3, double-blind, intra-patient randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of weekly applications of B-VEC gel in RDEB patients (NCT04491604) was completed with similar results for safety and lack of significant immune responses [67]. The primary endpoint was complete wound healing at 6 months, reached in 67% of wounds and significantly better than the placebo 22%. Six of eight seronegative patients seroconverted, and 13 of 18 developed antibodies to C7 without significant immunologic reaction, and no association between HSV-1 serostatus or C7 seroconversion [67]. Based on this, B-VEC was the first nrHSV-1 vector and the first topical gene therapy approved in the US, in 2023 [68]. The ease of topical application has advantages over invasive procedures, but more data is necessary to confirm long-term efficacy [69].

Following a similar approach, KB105, a nrHSV-1 vector encoding human transglutaminase I (TGM1), was developed to treat autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis (ARCI) [70]. Preclinical studies demonstrated that repeated topical administration induced TGM1 protein in the target epidermal layer only at the dose site, without fibrosis, necrosis, or acute inflammation [70]. A phase I clinical trial has recently begun (NCT04047732).

Overall, these trials clearly demonstrated the safety of non-replicative HSV-1 genomic vectors, while displaying varying levels of efficacy. Importantly, in no case did vector administration or transgene expression result in immune reactions strong enough to prevent treatment efficacy, independently of pre-existing HSV-1 exposure. For a recent review on HSV-1 vector safety and immune responses, see [71].

Safe and stable long-term expression of nrHSV-1

The above-described trials have demonstrated that nrHSV-1 vectors can be used for stable transgene expression from latently infected DRG neurons [64] or for strong and transient, although renewable, expression in epithelial cells [66, 67]. NrHSV-1 vectors have so far not yet been used in more mainstream gene therapy applications in other cell types, such as in diabetes, liver diseases, muscular dystrophies, or even in the CNS for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. For this, the prerequisite would be the establishment of a stable latent-like infection in cells other than peripheral neurons, a condition that would require not only the complete suppression of the expression of toxic virus genes but also to prevent the epigenetic silencing of the vector genome that has been described to take place in the absence of IE proteins, particularly ICP0, in cells other than PNS neurons. While these goals seem ambitious, recent results suggest that we are not that far from reaching them.

Firstly, and as quoted above, last-generation nrHSV-1 vectors, expressing no IE proteins in non-neuronal cells, are non-toxic and elicit no or only very low levels of inflammatory reactions, even in vivo in CNS [47, 49]. However, in nrHSV vectors the removal of IE regulatory genes results in genomes that not only adopt a latent-like state but also undergo heterochromatin shutdown of transgene expression. How to deal with the epigenetic repression of the virus genome, including the transgene locus, that occurs when the full set of IE genes is silenced or deleted is being increasingly understood [72, 73]. As above quoted, one of the main characteristics of the HSV-1 genome lies in its ability to establish two distinct gene expression programs depending on the infected cell types. In epithelial cells, lytic genes are accessible and expressed allowing for viral replication. However, in DRG and TG neurons, HSV-1 establishes a latent infection in which the lytic genes are heterochromatinized and repressed, while euchromatin marks are present on the LAT promoter allowing its continued expression.

Chromatin insulators are DNA sequences known to serve as barriers against heterochromatin spreading and allow the expression of genes located downstream of one insulator or surrounded by a pair of insulators. For a review on chromatin insulators, see [74]. CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) is one of the main insulator proteins that binds chromatin insulators to regulate 3D-chromatin architecture, creating a barrier between heterochromatin and euchromatin. Seven conserved chromatin insulator regions containing reiterated CTCF-binding motifs have been identified in the latent HSV-1 genome [34, 35]. The LAT regulatory region is surrounded by two chromatin insulators, called CTCF-repeat long 1 and 2 (CTRL1 and CTRL2), permitting its expression compared to the repressed lytic genes [75, 76]. Interestingly, IE gene regions are also flanked by such reiterated CTCF-binding motifs, where for example the ICP4 locus is flanked by CTCF-repeat short 3 (CTRS3) at the 5’ end and by the three insulators CTRS1, CTRS2, and CTCF-pac (CTa’m) at the 3’ end. The CTCF occupancy at these seven sites is differentially regulated during HSV-1 lytic infection, latency, and reactivation [77,78,79,80], highlighting the crucial role of such chromatin insulators in HSV-1 gene expression during different types of infections.

NrHSV-1 vectors that aim to express a specific transgene are not an exception to the rule and must be properly optimized with the insertion of chromatin insulators to protect the transgene locus from heterochromatin spreading. A nrHSV-1 vector lacking expression of all the 5 IE genes and bearing a transgene driven by a strong ubiquitous promoter displays higher and longer transgene expression in a variety of infected primary human non-neuronal cell types when the transgene is inserted between the CTRL1 and CTRL2 insulators of the LAT region compared to insertion between lytic genes without chromatin insulators [34, 47]. The same authors showed that both the CTRL1 insulator element and the LAP2 regulatory element, which acts as a position-independent long-term expression/enhancer element, play an important role in promoting this transgene expression. While CTRL2 possesses silencing activity [33] and acts to block enhancers [81], it seems to have less impact on transgene expression in these targeted cells at least by using this nrHSV-1 vector and its specific modifications.

A transgene inserted in the ICP4 locus and surrounded by CTRS3 and CTa’m insulators, where CTRS1 and CTRS2 have been deleted, is expressed in neuronal cells for a long term, whereas this same transgene is repressed in human dermal fibroblasts, suggesting a cell type-specific influence of these viral chromatin insulators on transgene expression [49, 82]. While the ICP4 genomic region is normally transcriptionally silent in neurons, the deletion of the CTRS1 and CTRS2 insulator sequences downstream of the ICP4 locus could have disorganized the 3D-chromatin structure of the episome, making this genomic region accessible in neuronal cells. CTCF also plays a plethora of roles in 3D-nuclear organization, regulating chromosome subnuclear position, 3D-chromosome structure, as well as short and long-range spatial chromatin interactions bringing distal regulatory elements near to finely regulated gene expression [83]. It is reasonable to hypothesize that such CTCF roles are conserved during HSV-1 infections and that alternative and specific HSV-1 episome subnuclear locations, 3D structures, and chromatin loops are dynamically established between HSV-1 lytic, latent, and reactivation states, to control IE gene expression.

The addition of non-HSV insulator sequences, surrounding or near a transgene inserted between the lytic genes UL50 and UL51, has been found to increase transgene expression [73], paving the way for the use of cellular regulatory elements to overcome the transcriptional repression of transgenes from nrHSV-1 vectors. While chromatin insulators are crucial for transgene expression from nrHSV-1 vectors, the level of defectiveness of these vectors seems also to have an impact on the transgene expression [82, 84].

Altogether these observations must be analyzed in a full context where transgene expression can be dependent on (a) its insertion position in the HSV-1 genome, (b) its protection from silencing by the chromatin insulators, (c) the promoter used, (d) the defectiveness of the vector, as well as (e) the targeted cell type. These elements are currently better understood facilitating the production and use of these vectors in clinical trials. Further understanding of how to deal with these genetic elements would represent important progress toward uncovering the full therapeutic potential of nrHSV-1 vectors. In addition, progress in the understanding of these topics is also pertinent regarding the production and use of amplicon vectors.

HSV-1-derived amplicon vectors

The concept of HSV-1 amplicons was created by Niza Frenkel and coworkers as the culmination of a series of fundamental studies aimed at identifying and characterizing the origins of virus DNA replication, the packaging signals, and the packaging mechanisms of the HSV-1 genome [85]. Classically, the genome of an amplicon vector is a concatemeric DNA composed of multiple copies in tandem of a sequence derived from a plasmid, known as the amplicon plasmid, which carries one origin of DNA replication (generally oriS) and one packaging signal (“pac”) from HSV-1 [86]. In addition, the amplicon plasmid carries the transgenic transcription cassette of interest and frequently includes a gene expressing a reporter protein for counting the amplicon particles. Conventional amplicon plasmids also contain standard bacterial sequences required for growing in E. coli. However, last-generation amplicons frequently derive from minicircles devoid of bacterial sequences and can contain eukaryotic sequences that help avoid dilution of the vector genome in dividing cells and DNA insulators that allow long-term expression, as will be described below (Fig. 1). Replication of the amplicon genome in eukaryotic cells proceeds like a rolling circle, generating long concatemers that are cleaved and packaged as DNA segments of approximately 150 kb, the size of wtHSV-1 genomes [86]. This makes amplicons a very versatile vector system since they can deliver different numbers of transgene copies, depending on the size of the seed amplicon plasmid or minicircle, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

The genome of conventional amplicon vectors derives from a plasmid (the amplicon plasmid) that, in addition to the sequences required for growth in E. coli (ColE1 origin of replication and a gene conferring resistance to an antibiotic such as AmpR) carries an origin of viral DNA replication, generally oriS, and a packaging sequence (“pac”) from HSV-1. This plasmid carries the transgene and, although not mandatory, a gene expressing a reporter protein that facilitates scoring the number of amplicon particles. Current amplicon minicircles are devoid of bacterial DNA and can carry DNA insulators (INS) to provide long-term transgene expression, and DNA sequences that allow the vector genome to be maintained in dividing cells (EPI). After being produced in bacteria, the bacterial sequences of minicircles are excised by restriction/ligation or by site-specific recombination in eukaryotic cells.

Functional HSV-1 particles contain about 150 kbp of DNA, disregarding the content of this DNA. This means that the number of transgenic copies that an amplicon vector will carry as tandem repeats depends on the size of the seed amplicon plasmid or minicircle. In the case of a small plasmid or minicircle of about 5 kbp, the capsids will carry some 30 copies, thus allowing very strong transgene expression, while if the seed plasmid or minicircle is about 150 kbp in size, that vector will contain a single transgene copy, that can include a complete human genomic locus. The amplicon genome always starts and ends by a “pac” sequence.

The amplicon plasmid or minicircle lacks most or all viral genes and depends therefore on an HSV-1 helper genome to provide the functions required for replication and packaging [86], similar to the manner that AAV vectors depend on a helper genome, derived either from HSV-1 or Adenovirus. First-generation amplicons were contaminated with a variable, but significant, amount of helper virus particles that, even if defective, contributed to potential toxicity and immune responses. Consequently, a large part of amplicon research and development in the following years was devoted to the generation of helper-free amplicon vectors.

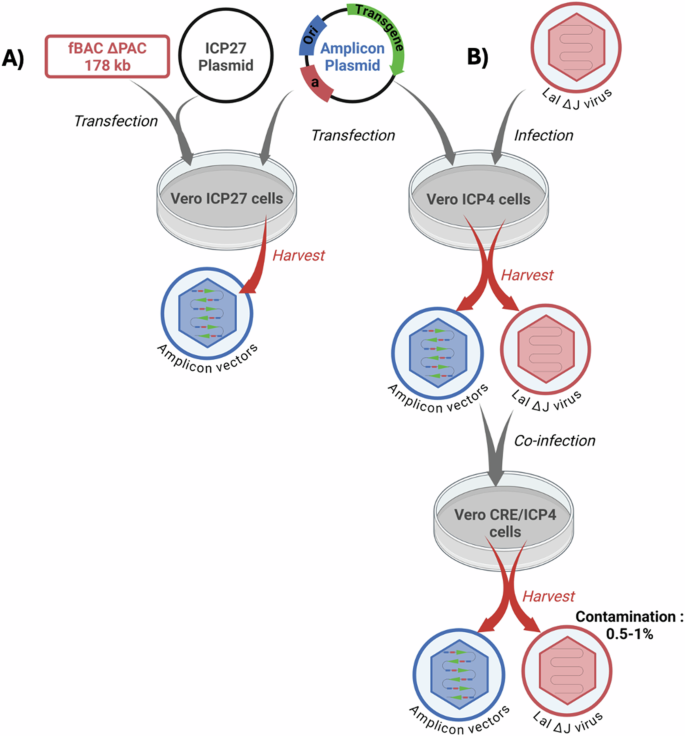

Amplicon and wtHSV-1 particles are identical from the structural, physical, immunological, and host-range points of view and cannot be separated once produced. This implies that the only way to prepare helper-free vector stocks is to eliminate the potentially contaminating helper particles during vector production. At the beginning of this century, critical improvements in amplicon vector technology permitted a very significant decrease of contaminant defective helper particles (Fig. 3). One of these methods consisted of co-transfecting eukaryotic cells with the amplicon plasmid and a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) containing a defective HSV-1 genome deleted for the “pac” sequences and the ICP27 gene (known as fHSVΔpacΔ27 0+) that can express all viral functions in ICP27 complementing cells but cannot be packaged due to the deletion of the “pac” sequences [87]. This system did result in the production of pure, helper-free amplicons, but only in limited amounts, due to the difficulty of transfecting significant amounts of large BACs into eukaryotic cells and also because this is a one-hit strategy, since the helper-free produced amplicon vectors cannot be further amplified.

There are currently two different systems to produce amplicon vectors. A first one (A) is based on the cotransfection of the amplicon plasmid together with a BAC containing a non-packageable helper HSV-1 genome deleted of one essential gene, such as ICP27, and devoid of “pac” sequences (fHSVΔpacΔ27 0+). The defective virus genome contains additional sequences, including ICP0, to make the virus genome oversized, thus adding a supplementary anti-packaging security element. When cotransfected into transcomplementing eukaryotic cells expressing ICP27 the system will produce helper-free amplicon vectors, although in limited amounts. A plasmid expressing ICP27 can be also cotransfected to further complement the ICP27 minus genome. B The second system is based on the conditional deletion of the “pac” sequences of the helper virus genome by site-specific recombination. The helper virus (HSV-1 LaLDJ) lacks the essential ICP4 gene and contains a unique “pac” sequence surrounded by two loxP1 sites in parallel orientation, making this virus Cre-sensitive. This virus can grow normally in ICP4-expressing cells but not in cells simultaneously expressing both ICP4 and Cre, due to the deletion of the “pac” signals, although all the lytic virus genes are normally expressed. In ICP4-expressing cells previously transfected with the amplicon plasmid, superinfection with HSV-1 LaLDJ will produce helper-contaminated stocks of amplicons. At this point, the stock of mixed particles can be serially passed on to ICP4-expressing cells as many times as required to produce large amounts of contaminated amplicon stocks. When aliquots of this stock are however used to infect ICP4/Cre-expressing cells, most of the helper genomes will lose the “pac” signals and will not be packaged thus producing amplicon stocks only slightly contaminated by helper genomes that have escaped site-specific recombination (0.5–1% of particles). This system thus allows to produce large quantities of amplicon vectors only marginally contaminated with otherwise non-replicative HSV-1 helper particles.

The second method is based on the conditional deletion of packaging signals in the helper genome using a site-specific recombinant system. This approach uses as helper an nrHSV-1 mutant (HSV-1 LaLΔJ) that lacks ICP4 and carries a unique and ectopic “pac” signal flanked by two loxP sites in parallel orientation [88]. This helper virus can normally be grown in ICP4 complementing cells but since it is Cre-sensitive it cannot be packaged in Cre-expressing cells, even if they express ICP4, due to excision of the “pac” signals. Therefore, upon introduction of the amplicon genome into cells simultaneously expressing Cre and ICP4, infection with HSV-1-LaLΔJ helper virus will supply the required virus proteins to generate amplicon stocks but, since most helper genomes will lose their packaging signals in these cells, they will not be packaged and the vector stocks will be only marginally contaminated (0.5–1.0%) with helper virus particles, which are otherwise non-replicative and nonpathogenic. Since the HSV-1-LaLΔJ helper-based amplicon production system relies on infection, instead of transfection procedures, it allows serial passages of the vector stocks by adding the helper virus at each passage, and a protocol has been developed to prepare as much amplicons as required [88], before eliminating the helper particles in the last step (Fig. 3). Although this system is well suited for large-scale production of amplicon vectors it needs further improvements since the presence of contaminant helper virus, even if marginal, could be problematic and add a potentially regulatory issue.

HSV-1-derived amplicons have many appealing features that make them a vector of choice, provided that the difficulties of producing large amounts of helper-free vectors are resolved. These features include (a) a very large cargo capacity, up to about 150 kb, (b) negligible toxicity with minimized immunogenicity due to the lack of expressed virus proteins, even at trace levels, (c) the preservation of most of the HSV-1 adaptations to the nervous system and (d) the versatility of this system, that allows delivery of cargos ranging from several copies of a short transcription unit, thereby resulting in strong transgene expression, up to a single copy of about 150-kbp transgenic transcription unit [6] (Fig. 2).

Long-term expression of amplicons and cellular repressor mechanisms

Expression from conventional amplicons, although variable in different cell types, has a limited duration. Different lines of research strongly indicate that the reasons underlying this shortcoming can be explained by the combined action of innate antiviral responses directed against the vector itself, silencing responses induced by the bacterial component of amplicons, and the inability of amplicon vectors to counteract these cellular responses. A first series of studies clearly demonstrated the implication of innate responses involving the signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) transcription factor, since in the absence of this factor amplicon expression is higher and longer, thereby implicating type I IFN and IFN-regulatory factors (IRF) in the inhibition of amplicon expression [89,90,91]. Experiments performed in STAT1-knockout mice showed 10-fold higher transgene (luciferase) expression than in wildtype mice, and luciferase expression remained detectable during at least 80 days, whereas in wildtype mice luciferase expression became undetectable after 2 weeks post-infection [89]. Additional studies using fibroblasts derived from wildtype and STAT1-knockout mice confirmed the significance of STAT1 signaling in transcriptional silencing of the amplicon-encoded transgene in vitro, indicating that type I IFN induced by systemic delivery of amplicons may initiate a cascade of immune responses that suppress transgene expression at the transcriptional level [89]. Another study showed that amplicon infection of cultured human fetal foreskin fibroblasts results in the induction of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3)-dependent antiviral response, characterized by upregulation of interferon-stimulated genes (ISG) ISG54, ISG56, IRF7, toll-like receptor 3, and by low levels of ß-IFN secretion. These responses lead to the establishment of an antiviral state in the amplicon-infected cells, which become refractory to subsequent infection with vesicular stomatitis virus [91].

In addition to the induction of STAT1 and IRF3-dependent innate antiviral responses, a second line of research strongly indicated the occurrence of an intrinsic antiviral response that can block HSV-1 expression very early after infection [92,93,94], even before induction of IFN. As amplicons do not express ICP0, a key virus protein that counteracts intrinsic cellular responses, this antiviral response may also be responsible for the silencing observed in some cell types. This has been demonstrated in several studies, but perhaps the clearest are two studies that were directly intended to test the hypothesis that expression of ICP0 could overcome silencing of encoded transgenes, using amplicons expressing ICP0. In the first, it was shown that amplicons expressing GFP under the control of the IE4/5 HSV-1 promoter and wildtype ICP0 driven by the HCMV promoter expressed higher levels of GFP in human primary fibroblasts, cultured rat cardiomyocytes, and rat neonatal cultured brain cells, than control amplicons lacking ICP0 or carrying a mutated inactive form of ICP0 [93]. In the second study, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)/PCR analysis revealed that conventional amplicon DNA became associated with HDAC1, a protein associated with transcriptional repression, immediately after infection. In contrast, with ICP0-expressing amplicons the vector DNA remained relatively unbound by HDAC1 for at least 72H post-infection. Mice inoculated systemically with amplicons expressing ICP0 exhibited significantly higher and more sustained transgene expression in their livers than those receiving conventional amplicons [94]. These results add further support to the notion that amplicon expression is subject to silencing and that ICP0 can restore normal expression or at least decrease transgene silencing. In support of this hypothesis, the reduction of particle-associated ICP0 levels that results from packaging the amplicon genome in the presence of the transcriptional regulator hexamethylene bis(acetamide) also reduces transgene expression [95], an observation that provides further evidence for the role of ICP0 in suppressing silencing mechanisms. Together, these data suggest that both the intrinsic and the induced innate antiviral responses can contribute to the silencing of amplicon-mediated transgene expression. For a review of innate responses in amplicon-infected cells, see [96].

Probably related to the above-quoted observations, it has also been shown that the bacterial DNA sequences present in conventional amplicon vectors cause rapid transgene silencing by forming inactive chromatin in normal human fibroblasts [97]. Bacterial sequences are specifically silenced through DNA methylation, inducing heterochromatic modifications that could spread to the whole genome. Infection with amplicons devoid of bacterial sequences (Fig. 1) induced some 20-fold higher transgene expression, and quantitative analysis of levels of transgenic mRNA showed that the increase in transgene expression was at the transcription level. In addition, nude mice injected with minicircle-based amplicons exhibited 10-fold higher luciferase expression than mice injected with plasmid-based amplicons. Furthermore, luciferase expression from conventional amplicons was undetectable 21 days after injection, whereas, with the minicircle amplicons, expression was detectable up to at least 28 days post-infection [97].

Not only do conventional amplicons lack ICP0, but they also lack DNA insulators. In other words, conventional amplicons are defenseless vectors. In support of this concept, it has recently been shown that adding adenine and thymine residues associated with DNA insulator-like sequences helps to protect a minicircle vector genome from heterochromatinization and silencing. Following delivery of this amplicon in the rat brain, long-term transgene expression, up to six months, was observed [98]. This important observation indicates that silencing of the amplicon genome can be overcome and open new avenues to strategies using these vectors for long-term expression both in neurons and in non-neuronal cells.

Large delivering capacity

The large packaging capacity remains one of the best advantages of amplicon vectors. Since the amplicon genome does not contain HSV-1 genes, very large insertions, up to about 150 kb, can be incorporated. Thanks to this outstanding feature, amplicons can potentially be used to deliver complete human genomic DNA loci, or DNA sequences that regulate chromatin structure and function or subnuclear localization. This may prove useful to design improved gene therapy vectors with advantages such as prolonged, physiological, and tissue-specific expression, generation of multiple splice variants from primary genomic transcripts, or synthesis of the full set of proteins required to assemble complex structures as well as metabolic or signaling pathways. Some of these very important goals have been already achieved several years ago. Thus, amplicons were used to deliver a 135-kbp fragment carrying the human low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) into human fibroblasts derived from patients with familial hypercholesterolemia (FH). The amplicon-borne LDLR gene was shown to express physiological levels in these cells [99]. Furthermore, this same locus was maintained within a replicating episomal amplicon vector carrying the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) latent replicon, composed of EBNA1 and oriP sequences, and expressed for 3 months at physiological levels following infectious delivery to CHO cells [99]. Amplicons were also used to deliver a 132-kbp sequence of genomic DNA comprising the CDKN2A/CDKN2B region, and it was demonstrated that this locus was correctly expressed, allowing the synthesis of three cell-cycle regulatory proteins derived from overlapping genes, utilizing alternative splicing and promoter usage [100]. Lastly, an amplicon delivering the 135-kbp human frataxin genomic locus was used to complement Friedreich’s ataxia deficiency in human cells [101]. These exciting experiments illustrate the outstanding potential of amplicons as genomic transfer vectors.

Stable maintenance in dividing cells

Two strategies have been developed to convert the amplicon genome into a replication-competent extrachromosomal element, thus increasing its stability in dividing cells. The first one uses the replication/segregation properties of scaffold/matrix attachment region (S/MAR) sequences, whereas the second uses technology based on human artificial chromosomes (HACs). A high-capacity episomal vector system carrying human S/MARs sequences was generated to provide vector maintenance and regulated gene expression through the delivery of a genomic DNA locus using amplicons. This system was used to deliver and maintain a 135-kbp genomic DNA insert carrying the human low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) genomic DNA locus at high efficiency in CHO clonal cells not expressing this receptor (ldlr/a7 cells) [102]. Long-term studies on CHO ldlr/a7 clonal cell lines carrying the S/MAR–LDLR amplicons showed episomal retention of one to four vector copies per cell, as estimated by Southern blots, and episomal stability of the vectors for more than 100 cell generations without selection. Expression studies of these cells showed that LDLR function was restored to physiological levels. This vector thus seems to simultaneously overcome the major problems of vector loss and unregulated transgene expression [102].

An alternative approach to confer stability on episomal amplicons is to convert the amplicon genomes into HACs. HACs are linear or circular DNA molecules that contain human alphoid centromeric DNA sequences carrying repeated centromeric protein B binding motifs, which can confer segregation and retention to transduced DNA during the division of human cells. Traditional methods to deliver HACs involve laborious procedures with low effectiveness that usually result in HACs shearing and degradation. By introducing alphoid sequences of different lengths into an amplicon plasmid, a series of HAC amplicon vectors were used to transduce different human cell lines, including glioma, lung fibroblasts, and kidney HEK 293T human cells, with an efficacy much higher than transfection-based methods [103]. In fibrosarcoma cells, a HAC amplicon expressing hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl-transferase (HPRT) successfully complemented the HPRT deficiency. It was also shown that the length of expression of the HAC was cell type dependent. Although in HEK 293T cells and in primary fibroblasts HACs were rapidly lost, in selected fibrosarcoma and glioma cells HACs were stable for more than 3 months. Although many improvements to this system are certainly required, this study describes a very significant advance in amplicon technology [103]. As above quoted, the episomal retention mechanism of EBV (EBNA1 and oriP) could also be used for stabilizing the amplicon genome [99], however, due to the potential role in the oncogenicity of EBNA1, this approach has regulatory issues.

Amplicon vectors as a tool. From pathophysiology to proof of concept

Even though HSV-1-derived amplicon vectors have not yet reached a clinical stage, they remain a very appealing tool for investigating pathophysiology. Indeed, amplicons were used to overexpress three types of vomeronasal receptor genes and to characterize cell responses to their proposed ligands in a rodent model [104]. In a recent very interesting study, an amplicon tracer system was developed for rapid and efficient monosynaptic anterograde neural circuit tracing [105]. This application could help to dissect neuronal connectomes or deliver transgenes into second-order neurons, to better understand physiological or pathophysiological processes.

In another example, amplicons were used to rapidly screen potential therapeutic transgene activity, by expressing different light chains of botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) serotypes under the control of an HCMV promoter. This permitted to compare the inhibition of CGRP release in transduced primary cultures of embryonic rat DRG neurons, thereby allowing the identification of the most potent BoNT in this system [65]. In a complementary study, a family of amplicons carried dual expression cassettes, coding for firefly luciferase (FLuc) driven by different sensory neuron promoter candidates and Renilla luciferase (RLuc) driven by the IE4/5 viral promoter [106]. This family of amplicons enabled rapid evaluation of the strength and selectivity of the different promoter candidates in organotypic cultures of excised adult DRG, as well as in sympathetic and parasympathetic ganglia from both control and SCI rats, based on the FLuc/Rluc ratio. This screening permitted the identification of the best promoter candidate to selectively express a transgene in DRG neurons [106].

In recent years, amplicons have been used in preclinical studies to demonstrate proof of concept of potential therapeutic approaches addressing cancer [107], epilepsy [108], or neuropathic pain [109], amongst many others. All these studies further underline the usefulness of amplicon vectors and the need to overcome the difficulties related to vector production.

Concluding remarks

Recombinant HSV-1 genomic vectors and amplicons are a remarkable pair of gene transfer tools for several reasons, but mainly because of their large gene delivery capacity, their low immunogenicity, which allows them to be readministered as many times as required, and their multiple adaptations to neurons, particularly non-integrative latency. However, despite these shared properties, they also differ in important respects, which are due in part to the different procedures of vector production (helper-dependent vs helper-independent) but also because of the different nature of the vector genome (single vs multiple transgene copies) and of important differences in the very early interaction they establish with infected cells. Due to these differences, during years these vectors have developed following parallel avenues, independently of each other. Now this seems to be changing and we are seeing a sort of confluence or unification of the conceptual and practical universes of both vector types. On the one hand, the deletion or inactivation of the whole set of immediately early genes brings the nrHSV-1 vectors closer to the amplicon model while, on the other hand, the protection from silencing of transgene expression by the introduction of DNA insulators in the amplicon genome is bringing these vectors closer to the nrHSV-1 genomic model. Moreover, results observed in both systems in the regulation of intrinsic and innate cellular responses, including silencing through repressive heterochromatin, are remarkably consistent and add a further layer of uniformity, which ensures that the growing knowledge in the two systems will feed each other.

Over the past years, significant breakthroughs in vector design, genetic engineering, and vector biology have accelerated the development of nrHSV-1 vectors. Their low immunogenicity and enhanced safety profiles have allowed the successful translation of these vectors into clinical trials, and no doubt this will increase in the next years. This is not yet the case with amplicons. Recent advances in amplicon vector biology are helping to resolve major challenges, including a better understanding of factors controlling long-term expression and the avoidance of vector dilution in dividing cells, and demonstrated their outstanding potential in preclinical gene therapy models. Despite these advances, however, we remain unable to produce helper-free amplicons in sufficient quantity to use them in clinical trials. Reaching this critical goal will be the most important future step in the development of HSV-1 vectors able to deliver genomic therapeutic transgenes driven by tissue-specific and physiologically controlled regulatory sequences, thus ensuring the precise quantitative, spatial, and temporal parameters defining efficient and safe therapeutic gene expression.

Responses