Novel fusion protein REA induces robust prime protection against tuberculosis in mice

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a serious respiratory infectious disease, and as a single infectious agent, it caused over 1.3 million deaths worldwide in 20221. The COVID-19 pandemic has negatively impacted TB diagnosis and care, setting back the progress made in the combating against TB1. It is estimated that one-quarter of the world’s population is infected with latent TB. Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) is currently the only licensed TB vaccine available for humans. However, while the BCG vaccine provides protection against disseminated forms of TB in newborns and children, its efficacy against pulmonary tuberculosis in adolescents and adults (0%–80%)—who carry the greatest burden of disease—remains highly variable2. Consequently, the development of improved vaccines that offer consistent protection against TB is urgently needed.

In recent decades, tuberculosis (TB) vaccine research has focused on identifying immunomodulatory elements within Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) to develop effective candidates3. Several TB vaccine candidates that are primarily based on MTB proteins have progressed through clinical trials or are in pre-clinical stages4,5,6. Combining different MTB proteins into multiplex chimeric vaccines has enhanced efficacy and introduced novel functionalities7. ESAT-6 and Ag85B, both potent T cell-stimulating antigens, are the most extensively used proteins with a long-track record in numerous TB chimeric vaccine candidates: Hybrid H1 (Ag85B-ESAT-6)8, H56 (H1 + Rv2660c)9, LT70 (H1 + MPT64 peptide-MTB8.4-Rv2626c)10, H4 (Ag85B-TB10.4)11, H65 (EsxD-EsxC-EsxG-TB10.4-EsxW-EsxV)12, H107 (PPE68-ESAT6-Espl-EspC-EspA-MPT64-MPT70-MPT83)13, and GamTBvac (Ag85A-ESAT6-CFP10)14. These vaccine candidates trigger a potent T cell immune response, despite the extended time required by T cells to reach the site of action, giving the bacillus time to multiply rapidly, or, in certain cases, the T cells are unable to sufficiently lower the bacterial load in animal models15. In addition to T-cell-dominant antigens, anti-mycobacterial proteins that activate dendritic cells (DCs)16 and macrophages17,18,19,20 are attractive targets for the development of novel TB vaccines. MTB survives within macrophages by arresting phagosomal maturation and impairing the maturation of DCs, preventing them from effectively stimulating T cell proliferation21,22. Therefore, the appropriate activation of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and T cells enhancing intracellular bacterial killing is critical to eradicating MTB.

In this study, we developed a Rv2299cD2D3-ESAT-6-Ag85B fusion protein that combines Rv2299c without the N-terminal portion (D1) with ESAT6 and Ag85B. Rv2299c, a molecular chaperone, is a member of the heat shock protein (Hsp) 90 kDa (Hsp90) family, and it is released by MTB in response to stressful conditions23. Owing to its dimeric state and chaperone nature, Rv2299c (also known as HtpGMTB) is crucial in improving the antigenicity, structural stability, and cytotoxicity of other antigens24. Previously, we reported that the combination of Rv2299c with ESAT-6 (Rv2299c-ESAT-6) hampers the cytotoxic nature of ESAT-6 by inducing dimerization, and confers improved and durable protection when used as an M. bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) booster against the hypervirulent strain HN878 in mice18,25. In addition, Hsps are characterized by their ability to bind to surface receptors of antigen-presenting cells, including DCs, followed by antigen internalization, processing, and presentation to exert antimicrobial action26. To this end, we demonstrated that the Rv2299c protein binds to Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) in DCs to elicit strong Th1-type responses. In addition, it serves as a physiological adjuvant and stimulates and links the innate and acquired immune systems18,27. The fusion of Rv2299c to Ag85B-ESAT6 enhances the protective efficacy of the Ag85B-ESAT6 (H1) vaccine in a short-term challenge mouse model by augmenting the protective immune responses of H127. Thus, we hypothesized that Rv2299c could act as an immune enhancer for other components in multi-antigen vaccines. In addition, we recently found that the D1 portion of the N-terminal (D1), central (D2), and C-terminal (D3) domains had no impact on the immunological response28. In this study, we designed a recombinant Rv2299cD2D3-ESAT6-Ag85B (REA) fusion protein, which changed the protein order of the Rv2299c-Ag85B-ESAT6 vaccine27 and removed the non-immunogenic N-terminal D1 domain of Rv2299c. The role of this newly developed vaccine candidate in effectively controlling MTB growth was studied. Additionally, we used mouse models to study the efficacy of REA, in which REA reduced the bacterial burden to undetectable levels in both the lungs and spleen of infected mice and also mounted a pool of long-lasting effector memory and antigen-specific multifunctional T cells.

Results

REA induces the activation of APCs

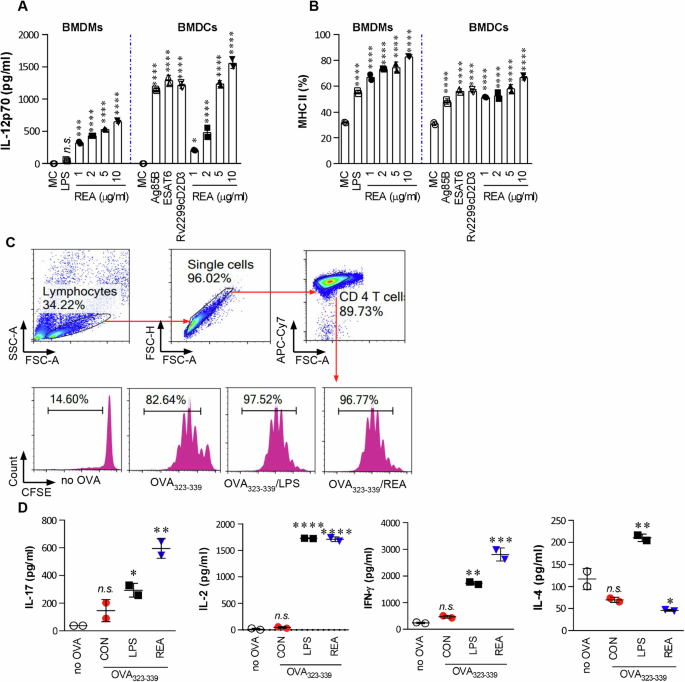

Recombinant REA was purified from the extracts of E. coli BL21 (DE3), which had been transformed with the constructed expression vector, and its purity, cytotoxicity, and endotoxin content (confirmed to be below <0.08 EU/ml by LAL assay) were analyzed (Supplementary Fig. 1). REA stimulated BMDMs and BMDCs to produce IL-12 and TNF-α in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. 2A), with no significant difference in production compared to the REA subcomponents ESAT-6, Ag85B, and Rv2299cD2D3. REA induced substantial IL-10 production, but only at high concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 2A). REA, ESAT-6, and Rv2299cD2D3 markedly upregulated MHC-II, CD80, and CD86 expression in both APCs (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. 2B). A syngeneic in vitro proliferation assay using OT-II TCR transgenic CD4+ T cells demonstrated that REA-matured BMDCs induced significant T-cell proliferation accompanied by production of IL-17, IL-2, and IFN-γ when compared to untreated BMDCs, but comparable to those of LPS-treated BMDCs (Fig. 1C, D). However, LPS-matured BMDCs secreted significantly higher levels of IL-4. These results suggest that REA affects both DCs and macrophage activation and guides naïve T cell proliferation toward Th1 and Th17 phenotypes.

A BMDMs/BMDCs (1 × 105 cells/well) were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml), REA (1, 2, 5, or 10 μg/ml), ESAT-6 (2 μg/ml), Ag85B (5 μg/ml), or Rv2299cD2D3 (5 μg/ml) for 24 h. B Activated BMDMs/BMDCs were stained with anti-MHC class II antibody, and the expression of surface markers was analyzed using flow cytometry. Bar graphs show the percentage (mean ± SEM of five separate experiments) for each surface molecule on Anti-Mo F4/80 BMDMs/CD11c+ BMDCs. The data shown are the mean values ± SD (n = 3). C, D Transgenic OVA-specific CD4 + T cells were isolated from the B6.Cg-Tg(TcraTcrb)425Cbn/J mouse strain, stained with CFSE, co-cultured for 96 h with DCs treated with REA (2 μg/ml) or LPS (100 ng/ml), and then pulsed with OVA323–339 (1 μg/ml) for OVA-specific CD4+ T cells. T cells only and T cells co-cultured with untreated DCs served as controls. The proliferation of OT-II+ T cells was assessed using flow cytometry, and cytokine levels were determined in the culture supernatants. The mean ± SEM is shown for three independent experiments. All cytokines in culture supernatants were determined using ELISA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, or ****P < 0.0001 when compared to untreated or medium controls. n.s.: no significant difference.

Next, we focused on REA activity in macrophages in subsequent experiments because Rv2299c has been shown to be a DC-activating protein through the TLR4 pathway18. REA activated the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways, p38 MAPK and ERK1/2, which are important for gene transcription and immunological responses (Supplementary Fig. 3A). Glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), PI3K, and AKT were phosphorylated in REA-treated BMDMs (Supplementary Fig. 3B, C). REA enhanced IκBα degradation, allowing FITC-tagged P65, an NF-κB particle, to translocate and bind to κB sites in the promoter regions of genes encoding proinflammatory cytokines (Supplementary Fig. 3D, E). Pretreatment with kinase inhibitors significantly impeded both the expression of costimulatory molecules and the production of cytokines (Supplementary Fig. 4).

REA inhibits the intracellular growth of MTB and enhances early endosomal maturation in BMDMs

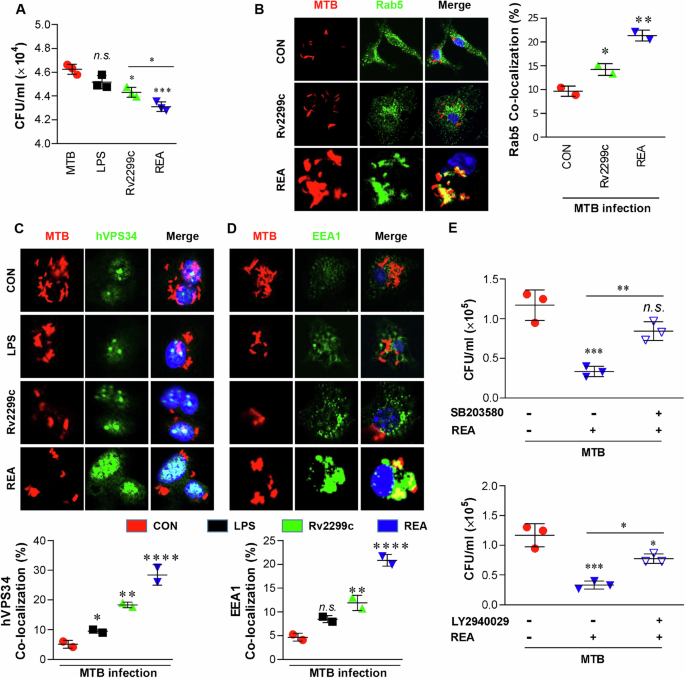

Appropriately activated macrophages control the intracellular bacteria. Intracellular MTB growth was significantly inhibited in REA-treated BMDMs when compared to Rv2299c alone, LPS, or the untreated control (Fig. 2A). In addition, REA or LPS treatment of MTB-infected macrophages augmented the expression of MHC and costimulatory molecules (CD80 and CD86), and the production of proinflammatory cytokines (Supplementary Fig. 5). The MTB-infected macrophages produced considerably more IL-12 when exposed to REA than when treated with LPS alone. MTB subdues the anti-mycobacterial response of the host29. These data suggest that REA overcomes the MTB-induced suppression of macrophages.

A BMDMs (1 × 105 cells/well) were infected with MTB (MOI = 1) for 4 h and treated with kanamycin for an additional 2 h to exterminate extracellular bacilli. After washing three times, the infected BMDMs were incubated with or without Rv2299c or REA (5 μg/ml) and LPS (100 ng/ml) for 72 h, and the colony forming unit (CFU) was measured using the cell lysates on 7H10 agar. B–D BMDMs were infected with red fluorescent protein-labeled MTB H37Rv strain (RFP-MTB) (MOI = 1) for 4 h and treated with LPS (100 mg/ml), Rv2299c (5 µg/ml), or REA (5 µg/ml) for 1 h in microscope cover glasses. Cells were then stained with anti-Rab5 (B), anti-hVPS34 (C), or anti-EEA1 (D) antibodies, and endosomal co-localization was imaged by confocal microscopy. The bar graphs represent the percentage co-localization of each detected protein. Java-based image processing program was used to enumerate the co-localization and intensity of phosphorylation. E REA-mediated MTB growth inhibition in BMDMs with or without pretreatment with SB303580 or LY2940029. CFUs were measured 72 h post-infection. Data obtained from independent experiments (mean ± SD) were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, or ****P < 0.0001 between MC (medium control) and antigen-treated BMDMs or comparison between inhibitor treatment vs untreated cells; n.s.: no significant difference.

Next, we investigated the mechanism underlying the REA-induced anti-mycobactericidal effects by tracking phagosome maturation and related signaling pathways. The localization of RAB5 to RFP-MTB phagosomes was significantly increased in REA-treated BMDMs than in untreated infected controls or Rv2299c alone (Fig. 2B). Phosphorylation of class I PI3K, which allows the recruitment of proteins involved in phagosomal maturation30, was rapidly enhanced 30 min after REA treatment (Supplementary Fig. 6A). The intensity of colocalized hVPS34 (28.44 ± 2.44) into the MTB phagosome in REA-treated BMDMs was significantly higher than in Rv2299c- or LPS-treated cells (Fig. 2C). hVPS34 triggers the cyclic accumulation of PI3P on the phagosome, which is essential for the recruitment of early endosomal antigen 1 (EEA1), and assists the phagosome in acquiring vacuolar-type ATPase (V-ATPase) to initiate acidification. Extensive recruitment of EEA1 to endosomal vesicles in MTB-infected BMDMs was induced by REA treatment compared to Rv2299c or LPS treatment (Fig. 2D). In addition, p38 MAPK phosphorylation was induced by MTB for a short time, but was strongly induced for a longer time in REA-treated BMDMs, regardless of MTB infection (Supplementary Fig. 6A). PI3K phosphorylation was also enhanced by REA treatment in MTB-infected cells. REA-induced P38 phosphorylation was not prominently suppressed by SB203580 (a p38 MAPK inhibitor) and LY2940029 (a PI3K inhibitor), although REA-induced PI3K phosphorylation was inhibited by both the inhibitors in MTB-infected cells (Supplementary Fig. 6B, C). MTB-induced phosphorylation of both the kinases was substantially inhibited by each inhibitor. REA-induced inhibition of MTB growth was prevented by both the inhibitors (Fig. 2E). Thus, the P38-PI3K signaling pathway is important for REA-based phagosomal maturation in BMDMs during MTB infection.

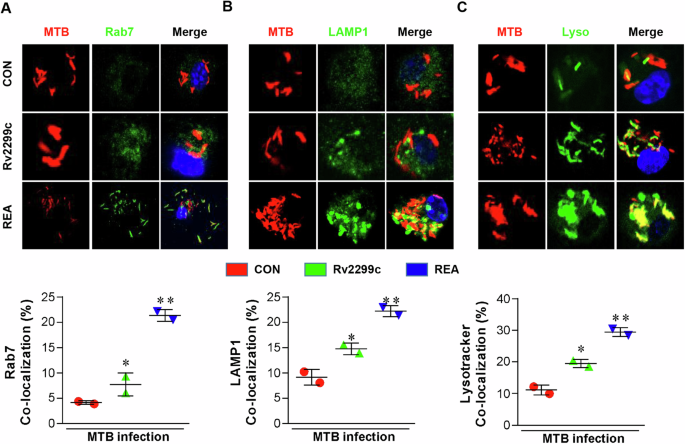

REA enhances phagosomal acidification and lysosomal fusion

Rab7 is a small GTPase associated with late endosomes and lysosomes, and its exclusion leads to bacilli escaping31,32. REA strongly induced the co-localization of Rab7 in MTB-containing phagosomes (Fig. 3A). REA also significantly induced the co-localization of LAMP (Fig. 3B), which was significantly reduced by p38 and PI3K inhibitors (Supplementary Fig. 7A, B). Moreover, we monitored the fusion of MTB-containing late phagosomes with lysosomes using pH-sensitive LysoTracker dye, the intensity of which directly correlates with the acidified lysophagosome milieu33. The acidotropic dye LysoTracker blue, a weak base conjugated to a blue fluorophore, was protonated and remained trapped in the acidified organelles of REA-treated infected BMDMs (Fig. 3C).

A BMDMs (1 × 106 cells/well) were infected with RFP-MTB (MOI: 1) for 4 h and treated with Rv2299c (5 µg/ml) or REA (5 µg/ml) for another 1 h. The cells were then stained with anti-Ras-associated protein 7 (RAB7) (A), and anti-lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1) (B). C LysoTracker™ Green DND-26 and phagosome-containing MTBs were observed using confocal microscopy for co-localization of the indicated marker. *P < 0.05 or **P < 0.01 untreated MTB-infected BMDMs compared to Rv2299c or REA-treated infected BMDMs. Java-based image processing program was used to enumerate the co-localization and intensity of phosphorylation.

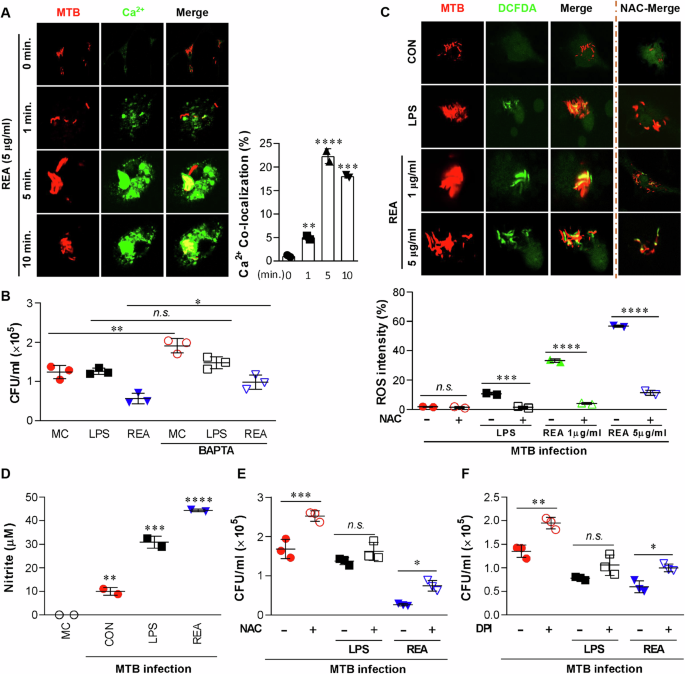

REA increases intracellular calcium and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in MTB-infected BMDMs

Transient alteration of the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration is an essential signaling mechanism in many cellular events, including actin rearrangement, recruitment of PI3K and EEA1, modulation of membrane fusion between phagosomes and lysosomal vesicles, and activation of NADPH oxidase34. Using Fluo-4/AM, a dynamic single-wavelength fluorescent Ca2+ indicator, we initially examined the change in Ca2+ concentration in MTB-infected BMDMs. Following REA treatment, intracellular calcium concentration transiently increased, peaked at 5 min, and then declined (Fig. 4A). Pretreatment with the calcium chelator BAPTA inhibited the REA-induced co-localization of EEA-1 and phosphorylation of PI3K and p38 (Supplementary Fig. 8) in MTB-infected macrophages and abrogated REA-mediated inhibition of MTB growth (Fig. 4B). Stimulation of the PI3K signaling pathway and an increase in intracellular free Ca2+ are important signaling mechanisms for assembling NADPH oxidase on the phagosome membrane, which initiates ROS and NO production35. REA-treated cells showed elevated ROS localization (Fig. 4C) and increased NO production in the cell supernatant (Fig. 4D). The inhibition of NOX enzymes using diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) significantly reduced ROS localization in all groups (Supplementary Fig. 9A). Similarly, treatment with N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC), a ROS scavenger, reduced the co-localization of ROS under all conditions (Fig. 4C). REA-mediated inhibition of intracellular MTB growth was partially abrogated by NAC pretreatment (Fig. 4E). Moreover, the REA-mediated localization of both LAMP1 and LysoTracker in the MTB was significantly reduced by DPI (Supplementary Fig. 9B, C). It has been reported that the intracellular elevation of ROS levels potentiates the activation of PI3K/Akt signaling36. In this study, we found that the inhibition of NOX2 activation or ROS generation significantly affected the phosphorylation of PI3K and p38 (Supplementary Fig. 9D). Similarly, DPI improved the survival of MTB inside host cells (Fig. 4F). These results prove that phagosomal maturation results either from the production of ROS by phagocytic NADPH oxidase, which is recruited early in phagosome biogenesis, or by the fusion of the phagosome with lysosomes.

A In 18 mm coverslips, BMDMs (1 × 106 cells/well) were infected with RFP-MTB (MOI: 1) for 4 h. The cells were then loaded with calcium-sensing Fluo-4/AM for 30 min and treated with REA (5 µg/ml) for the indicated time. The co-localization of calcium was captured using confocal microscopy. The bar graph represents the percentage fluorescence intensity of Fluo-4/AM for infected cells with or without REA. B The intracellular bacterial growth was determined with or without BAPTA/MA 1 h before infection. C Under the same condition as A, the intracellular ROS levels were measured based on dihydrodichlorofluorescein (DCDF, 10 µM) with or without N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC, 10 mM). The bar graph represents the intensity of DCF fluorescence calculated using ImageJ. D The levels of NO were measured in culture supernatants after 72 h of REA or LPS with or without infection. E, F The intracellular bacteria growth was determined with or without NAC or with or without DPI (10 µM) 1 h before infection. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. n.s.: no significant differences.

REA induces extraordinary protective efficacy

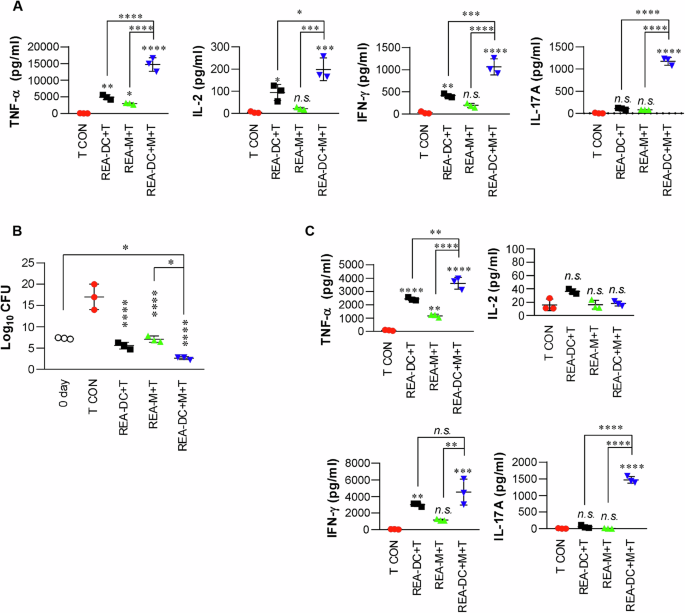

We hypothesized that REA-mediated DC and macrophage activation induce a strong protective response via T cell activation against TB. We initially determined the synergistic effects of both APCs in inducing anti-mycobacterial responses. T-cells activated by the two APCs stimulated with REA exhibited significantly higher cytokine levels (Fig. 5A) and induced more significant bacterial growth inhibition and synergistic production of cytokines, except IL-2, when added to MTB-infected BMDMs (Fig. 5B, C), compared with T cells activated by a single APC. These results suggest that REA-activated DCs and macrophages can effectively activate T cells with bactericidal activity. Next, we determined the cytokines produced by restimulated splenocytes 6 weeks after a single immunization with REA or its components. The splenocytes from REA-immunized mice produced significantly higher levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α in response to each antigen, except for Rv2299c, in comparison to those from mice immunized with each individual component (Supplementary Fig. 10), suggesting an enhanced T-cell response to each antigen due to fusion with Rv2299cD2D3.

A Splenic CD4+ T cells isolated from BCG-vaccinated mice (at 4 weeks post-vaccination) were co-cultured with REA-treated DCs (1 × 105 cells/well), REA-treated macrophages (1 × 105 cells/well), or both REA-treated DCs (5 × 104 cells/well) and macrophages (5 × 104 cells/well) for 72 h at a APCs:T cell ratio of 1:10. The cytokines in the cell supernatants were measured by ELISA. n.s.: not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 compared to T cell only (T). B, C After co-culture for 3 days in the same manner as (A), T cells were harvested and co-cultured with MTB-infected BMDMs for 72 h. Intracellular bacterial growth within BMDMs (B) and cytokines in the culture supernatants (C) were measured. The bar graphs show the mean ± SD (n = 3). n.s.: not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 compared to T cell only.

Next, we compared the vaccine potential of REA with two Rv2299c-based vaccines, Rv2299c-ESAT6 and Rv2299Cd2D3-ESAT6, in a mouse model based on the fact that an avirulent H37Ra strain can be employed to evaluate the vaccine potential of a candidate19,27,37. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 11, the mice were immunized and challenged intra-tracheally with H37Ra. Remarkably, the bacteria were undetectable in the spleen and lungs of mice immunized with REA, except in the case of one lung at 14 weeks post-infection (Supplementary Fig. 11B), which was unprecedented considering REA as a subunit vaccine. However, BCG- or other antigen-immunized mice did not show significant protective efficacy compared to unvaccinated or DDA/MPL-injected mice. Triple-positive CD4+ T cells co-expressing IFN-γ+IL-2+TNF-α+ were significantly elevated after being restimulated with ESAT6 and REA but not Rv2299c in both lung and splenic cells of the REA-immunized group compared to other groups (Supplementary Figs. 11C and 12A, B). In double-positive IL-2+TNF-α+CD4+T cells, REA-specific CD4+T cells were significantly higher in the lungs of REA-immunized mice, and ESAT6-specific CD4+T cells were significantly higher in the lungs of mice immunized with all three antigens compared to BCG or control groups (Supplementary Fig. 11C), but no significant difference in these levels was observed in the spleen (Supplementary Fig. 12B). Production of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, and IL-17 in the restimulated cells of the lung, spleen, and lymph node was higher in the mice immunized with Rv2299c-based vaccines than in BCG-injected or infection-control mice, and in particular, IL-2 and IL-17 productions were prominent in antigen-immunized mice (Supplementary Fig. 12C, D).

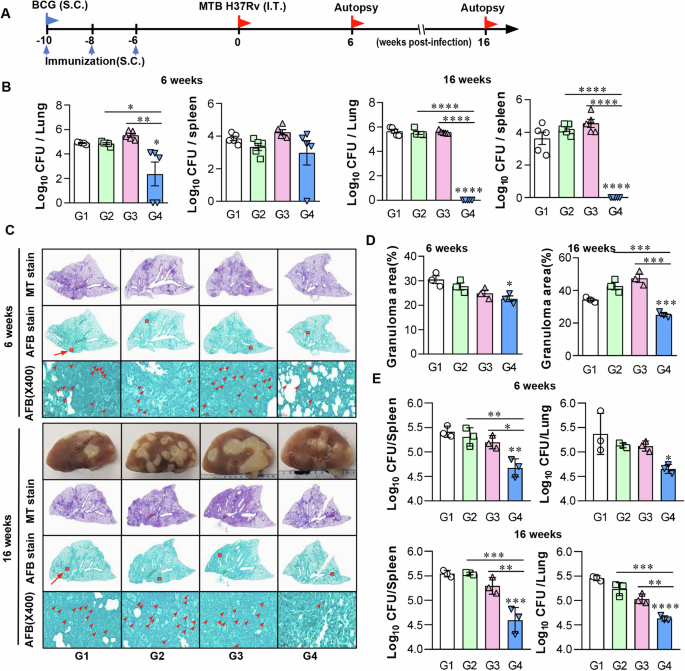

Finally, we confirmed the protective efficacy of REA in a mouse model using the virulent H37Rv strain. All mice were immunized following the same schedule as depicted in Fig. 6A, and bacterial loads were determined twice after challenge (Fig. 6A). At 6 weeks post-infection, bacterial loads were significantly reduced in the lungs and spleen of REA-vaccinated mice than in the adjuvant control (Fig. 6B). Unexpectedly, BCG did not show a protective efficacy 6 weeks after challenge. Surprisingly, at 16 weeks, the bacteria were undetectable in both the lungs and spleen of all mice vaccinated with REA; however, the BCG or the adjuvant alone did not show any significant protective efficacy. Pathological or gross findings of the lung tissues are correlated with the bacterial load (Fig. 6C). In REA-immunized mice, the acid-fat bacillus (AFB) number was significantly reduced at 6 weeks compared to that in other control groups and was hardly observed at 16 weeks post-infection (Fig. 6C). The granuloma area was also significantly reduced in group 4 (Fig. 6D). The lung and spleen cells of REA-immunized mice at 6 weeks post-infection significantly inhibited the growth of MTB within BMDM, and their activity was maintained until 16 weeks post-infection (Fig. 6E).

A Schematic model of the mouse protection assay. C57BL/6 mice were administered REA vaccine subcutaneously (s.c.) three times with 5 µg REA/DDA (250 µg) and MPL (25 µg). Infection-only control mice received three times s.c injections of PBS, while BCG control mice were vaccinated s.c. once with 1 × 105 CFU BCG. Each group of mice was infected with 1 × 104 CFU of MTB (H37Rv) via intra-tracheal (i.t.) route 6 weeks after the final vaccination. Then, mice were sacrificed at 6 or 16 weeks after the challenge for histology and bacterial load analyses. B Differences in bacterial loads in the lung and spleen of each group of mice at 6 or 16 weeks after challenge with MTB are shown. C Representative histology images of the lung lobes of each group of mice with Masson trichrome (MT) and Acid-Fast Bacillus (AFB) staining at 6 or 16 weeks after the challenge. D The granuloma area (%) from the lung section has been plotted. All data are presented as mean ± SD of five mice in each. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 compared with the infection-only or adjuvant-alone group. E MTB-infected BMDMs were co-cultured with lung and spleen cells from 6 or 16 weeks post-infection mice. After 3 days, intracellular MTB growth in the BMDMs was determined. Data are the mean ± SD (n = 3); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, or ****P < 0.0001. n.s.: no significant difference. Group G1: infection only; G2: BCG alone; G3: adjuvant alone (DDA-MPL); G4: REA/DDA-MPL.

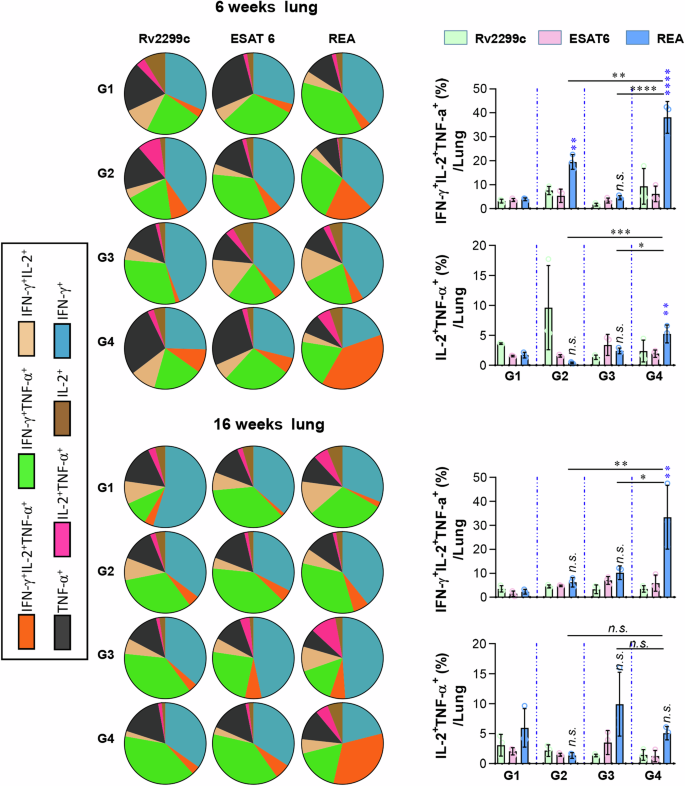

Multifunctional T cell analysis showed that REA-specific IFN-γ+IL-2+ TNF-α+ CD4+ T cells were higher in the lung at 6 weeks and 16 weeks post-infection, and in the spleen at 16 weeks post-infection of REA-immunized mice (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Fig. 13). However, there was no specific correlation with bacterial burden in antigen-specific IL-2+TNF-α+CD4+T cells. The levels of cytokines produced by antigen restimulation were tenfold lower at 16 weeks than at 6 weeks post-infection (Supplementary Fig. 14). Production of IL-2 and IL-17 against REA and/or ESAT6 in the lung and spleen of REA-immunized mice was significantly higher at 6 weeks and 16 weeks post-infection compared to other groups. TNF-α and IFN-γ production showed similar patterns, although other control groups also showed some production according to stimulating antigens (Supplementary Fig. 14). At 16 weeks post-infection, all cytokines in the spleen and IL-2 and IL-17 in the lungs were produced only in the REA-immunized mice (Supplementary Fig. 14).

The cells of the lung obtained from each group of mice at 6 and 16 weeks post-infection were treated with Rv2299c (2 μg/ml), ESAT-6 (2 μg/ml), or REA (2 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 12 h in the presence of GolgiStop. Upon stimulation with each antigen, cell counts of Ag-specific, multifunctional CD4+ T-cells producing IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 in the lung cells were determined using flow cytometry. The data display both the pie chart and bar graph of cell counts from the lung. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD for five mice from each group. n.s.: not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 compared with the REA treatment for each group with the infection group. Group G1: infection only; G2: BCG alone; G3: adjuvant alone (DDA-MPL); G4: REA.

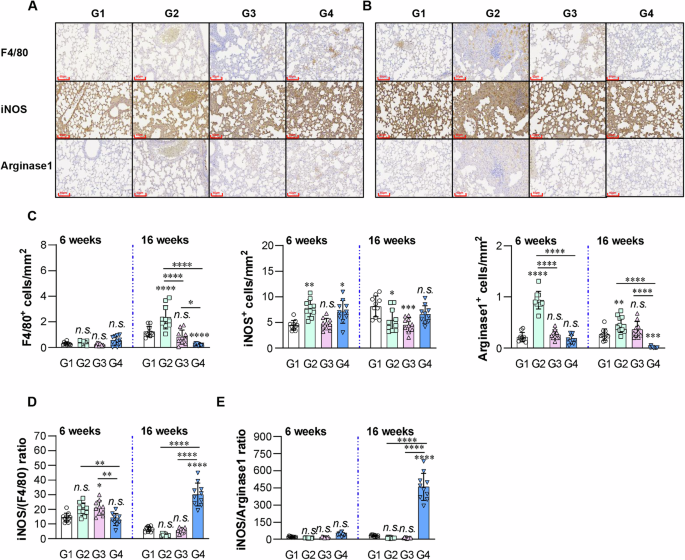

Subsequently, phenotypes of macrophages in the lung tissues were analyzed with an immunohistochemical (IHC) stain. The positive cell numbers in 10 areas/tissue were counted. These antigen-presenting cells (including F4/80+, MHC-II+, or CD11c+) generally decreased in the REA-vaccinated group compared with that in the other groups (Fig. 8A–C and Supplementary Fig. 15A–C). Notably, M2-associated CD163+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 15C) and Arginase+ cells (Fig. 8C) were almost absent at 16 weeks post-infection in the REA-vaccinated group. The ratio of M1/(F4/80 = M), M2/(F4/80 = M), and M1/M2 were measured. The M1(iNOS)/M ratio in REA-vaccinated mice was significantly lower than that of BCG- or adjuvant-injected groups at 6 weeks post-infection but was significantly higher than that at 16 weeks post-infection than that of other groups (Fig. 8D). The M2 (CD163)/M or M2(Arginase)/M ratio in REA-vaccinated mice was significantly lower than that of other groups at 6 weeks, although there was no prominent difference at 16 weeks (Supplementary Fig. 15D). The M1/M2 ratio (iNOS/Arginase and iNOS/CD163) was significantly higher in REA-vaccinated mice than that of the other groups at 16 weeks (Fig. 8E and Supplementary Fig. 15E). These results suggested that REA induced M1 polarization of macrophages that was continuously maintained.

Among the ten randomly selected images, one representative image was chosen for each of the F4/80, iNOS, and Arginase-1 IHC-stained sections of mice lungs at (A) 6 weeks and (B) 16 weeks post-infection. C The integrated optical density quantified with ImageJ software is presented. All data are presented as the mean ± SD of the number of positive cells in 10 regions/tissue. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. n.s.: not significant. D Graph showing the ratio of M1 type macrophages (iNOS+) to total macrophages (F4/80+) or E M2 type macrophages (Arginase-1+). Data are shown as the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001. n.s.: no significant difference. Group G1: infection only; G2: BCG alone; G3: adjuvant alone (DDA-MPL); G4: REA/DDA-MPL.

Taken together, our data suggest that T cells with bactericidal activity, M1 polarization, and long-lasting antigen-specific IL-2 and IL-17 production are involved in inducing REA-mediated protective immunity against TB in mouse models.

Discussion

A number of TB vaccine candidates have been developed, with some advancing to clinical trials38. However, none of these candidates have demonstrated the clearance of infection in a mouse model. Nonetheless, intravenous injection of BCG in a model of non-human primates offers nearly sterilizing protection39. In this study, we elucidated the sequentially induced molecules and related signaling pathways to kill MTB in macrophages activated with REA. The protective efficacy of REA was unexpectedly demonstrated by suppressing MTB growth to undetectable levels in mouse models. Although bactericidal effects induced by REA in macrophages may not be directly related to the underlying mechanism by which the REA vaccine is effective, the appropriate activation of macrophages (along with DCs) may play a critical role in inducing a strong protective effect against TB. In fact, REA activated DCs and macrophages to elicit synergistical T cell responses with bactericidal activity in vitro (Fig. 5) and enhanced T cell responses to its components, ESAT6 and Ag85B, in vivo (Supplementary Fig. 10). It is well-known that a strong induction of Th1 responses does not always correlate with the efficacy of TB vaccines, suggesting that traditional vaccine approaches focused on T cell antigens often overlook the crucial role of macrophages in host defense against MTB, limiting the development of an innovative vaccine. Therefore, our approach represents a paradigm shift in TB vaccine development by targeting both macrophage and DC-mediated immunity.

We found that REA induced Th1 and Th17 responses via DC maturation and potentiated the cells of the innate immune system to effectively control MTB growth by promoting phagosome maturation via activation of the PI3K–p38 MAPK pathway. Here, we focused on understanding the mechanism underlying REA activity in killing MTB in macrophages. REA promotes the co-localization of hVPS34 (Class III PI3K) and EEA1 to facilitate the conversion of Rab5-positive early endosomes to Rab7-positive late endosomes. The application of REA to BMDMs during infection promoted LAMP1 co-localization and fusion with lysosomes and facilitated intracellular bacilli killing, antigen presentation, and proinflammatory cytokine production. MTB is a pathogen that has developed several strategies to suppress phagosomal maturation. Man-LAM, SapM, and protein phosphatases (Ptp A and B) secreted by the bacilli interfere with the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaM kinase II or CaMKII)-PI3K hVPS34 cascade40. Concurrently, TB bacilli inhibit the fusion of lysosomes with phagosomes through selective exclusion of Rab7 GTPase and LAMP1 coupling by retaining Rab5 GTPase on the phagosome membrane. Rab5 proteins, members of the Ras superfamily of low-molecular-weight GTPases, must undergo cycling back to inactive GDP-bound forms and function as molecular switches to promote vesicle fusion41 which otherwise inhibits Rab7 or LAMP1 binding sites or the formation of the new phagosome. Our results suggest that REA interferes with the diverse survival strategies employed by MTB for its survival.

Calcium (Ca2+), the other most important pathway that MTB endeavors to inhabit for intracellular survival, was augmented in REA-treated infected BMDMs. Ca2+ plays a key role in actin rearrangement by stringently controlling the subsequent steps involved in phagosome maturation. The use of MTB coronin1 to block the Ca2+/Ca-binding protein calmodulin pathway limits the transport of lysosomal components to phagosomes via PI3P-dependent pathways42. The application of BAPTA-AM, an intracellular calcium chelator before REA treatment disrupted phosphorylation of P38 and PI3K, and localized EEA1, which inhibited phagolysosome formation. Moreover, the intracellular survival of MTB in REA-treated infected BMDMs doubled after calcium inhibition during phagosomal maturation. These results suggested that REA mediates the regulation of phagosome maturation through cytosolic Ca2+ release in BMDMs. In addition to inhibiting Ca2+ signaling, MTB employs defense mechanisms to shield itself from NADPH oxidase enzyme assembly and produces a respiratory burst (ROS) and ROS–mediated bacterial killing43. PPE2, which belongs to the proline–glutamate/proline–proline–glutamate (PE/PPE) family of MTB, inhibits NADPH oxidase-mediated ROS generation to invade the host immune response44. Application of NAC, a ROS scavenger, in infected BMDMs before REA treatment significantly reduced the intracellular level of ROS and improved the intracellular survival of MTB. NO, an l-arginine-liberated radical catalyzed by NOS, is the principal effector mechanism in activated murine macrophages responsible for killing and inhibiting the growth of virulent MTB45. Thus, the elevation in NO levels following REA treatment, together with an increase in ROS, signifies the translocation of the cytoplasmic component of NADPH oxidase to the membrane, as along with an increase in the catalytic activity of NOS and its role in bacilli killing. Phosphorylation of the cytosolic component of NADPH p40phox in REA-treated BMDMs clearly demonstrates the assembly of NADPH for ROS formation. These results suggest that REA triggers effector molecules involved in phagosome maturation and fusion to kill MTB in macrophages.

DCs and macrophages are essential for initiating and maintaining T-cell activation. REA effectively stimulated the expression of MHC and costimulatory molecules that require T-cell activation in both APCs, suggesting that REA potentiates T-cell responses to its epitopes and has a practical defense function against MTB. T cells activated by both DCs and macrophages stimulated with REA inhibited intracellular MTB growth more effectively than activated DC or macrophages alone (Fig. 5B) and the T cell responses to ESAT-6 or Ag85B were significantly higher in mice immunized with REA than in those immunized with ESAT-6 or A85B alone (Supplementary Fig. 10), indicating that Rv2299cD2D3 effectively can enhanced the protective immune response against fused ESAT6 and Ag85B in vivo. In practical, REA induced unexpected protective efficacy by eliciting an immune response capable of clearing MTB in a mouse model. In contrast, Rv2299c-ESAT6 and Rv2299cD2D3-ESAT6 did not show significant protective efficacy as prime vaccines (Supplementary Fig. 11). There were no prominent differences in antigen-specific Th1 and Th17 responses in the spleen, lymph nodes, or lungs of mice immunized with the three fusion proteins (Supplementary Fig. 12). However, post-challenge, ESAT6- and REA-specific multifunctional IFN-γ+IL-2+TNF-α levels were significantly higher in the lung and spleen of the mice immunized with REA than mice immunized with Rv2299c-ESAT6 or Rv2299cD2D3-ESAT6.

A mouse model using virulent MTB H37Rv also revealed that REA-immunized mice suppressed MTB growth to undetectable levels at 16 weeks post-infection, which was supported by gross and pathological findings and AFB staining of lung tissues. In contrast, the granuloma area in the REA-immunized mice did not dramatically decrease, suggesting that the resolution of the inflamed area progressed slowly. This was supported by significantly decreased number of DCs and macrophages at 16 weeks in REA-immunized mice compared to that in the other groups, indicating that the inflammatory reaction was alleviating. The bactericidal activity of the lung and spleen cells was continuously maintained for 16 weeks post-infection in REA-immunized mice (Fig. 6E). These results suggest that REA-matured DCs and macrophages activate antigen-specific T cells that have bactericidal activity. A deeper analysis of the temporal immune response patterns provides further insight into how this activation translates to long-term protection. Our results showed that REA vaccination led to significant changes in immune cell populations, particularly in the M1/M2 macrophage ratio, which remained elevated at 16 weeks post-infection. This sustained M1 polarization coincided with maintained bacterial clearance. Furthermore, we observed that while overall cytokine levels decreased by 16 weeks, REA-specific multifunctional T cells (IFN-γ + IL-2 + TNF-α + CD4+) remained elevated in both lung and spleen, suggesting their crucial role in long-term protection. The sustained production of IL-2 and IL-17 specifically in REA-immunized mice at 16 weeks, combined with continued bactericidal activity of lung and spleen cells, provides strong evidence for the causal relationship between these immune parameters and protective efficacy. These temporal patterns of immune responses align with the unprecedented bacterial clearance observed in REA-vaccinated mice, suggesting that the combination of sustained M1 polarization, multifunctional T cell responses, and specific cytokine profiles contributes to the robust protective immunity induced by REA. We observed that the factors involved in strong REA-mediated protective immunity are antigen-specific multifunctional IFN-γ+IL-2+TNF-α+CD4+ T cells and long-lasting T cells producing cytokines such as IL-2 and IL-17 in the tissues. A more detailed investigation of the protective mechanism of REA is required to identify the biomarkers correlated with protection. Furthermore, the efficacy of REA has to be determined in other animals. The protective efficacy of the BCG Tokyo strain was not observed in our mouse model system. This observation becomes particularly relevant when considered in the broader context of BCG vaccine efficacy studies. Recent studies using the BCG Pasteur strain have shown varying and sometimes controversial results regarding protective efficacy. While some studies demonstrated significant early protection followed by loss of efficacy at later time points46, others showed minimal protection (0.1–0.3 log reduction) even with standard dosing47. These contrasting findings with the Pasteur strain highlight the complexity of BCG-induced protection, independent of strain differences.

Additionally, our use of the BCG Tokyo strain may have contributed to the limited protection observed. Previous reports with the Tokyo strain have shown variable levels of protection in mouse models challenged with H37Ra48. A comprehensive review comparing different BCG strains has demonstrated that the Tokyo strain generally exhibits lower protective efficacy compared to the Pasteur strain49. Therefore, the limited protection observed in our study likely reflects both the inherent variability in BCG-induced protection and the characteristically lower protective efficacy of the Tokyo strain.

Notably, full-length Rv2299c-Ag85B-ESAT6 showed some protective efficacy as a prime vaccine in the short-term mouse model27, whereas REA changed the antigen order and deleted the N-terminal protein of Rv2299c when compared to Rv2299c-Ag85B-ESAT6; however, the protective efficacy of REA was prominently potentiated, although a direct comparison with the efficacy of the two fusion proteins was not conducted side by side. Based on our unpublished preliminary findings, we observed the vaccine efficacy to be greater when ESAT6 was inserted into the next Rv2299c, rather than when it was inserted at the end of a fusion protein. Molecular weight is an important factor for the commercialization of a subunit vaccine, and the molecular weight of REA was reduced by ~30 kDa compared to that of Rv2299c-Ag85B-ESAT6. This reduction in molecular weight indicates that REA possesses certain advantages in terms of purification.

Based on our unprecedented findings showing complete elimination of MTB in mouse models, REA demonstrates tremendous potential as both a preventive and therapeutic vaccine candidate. The ability of REA to achieve bacterial clearance to undetectable levels, which has not been previously reported for other subunit vaccines, strongly supports its advancement toward clinical trials. While BCG remains the only licensed TB vaccine, its variable efficacy (0%–80% in adults) highlights the urgent need for more effective alternatives. Our study demonstrates that the recombinant REA chimeric protein induces robust Th1 and Th17 responses through dendritic cell maturation and enhances MTB killing in bone marrow-derived macrophages by promoting phagosomal maturation via the PI3K–p38 MAPK-Ca2+-NADPH oxidase pathway. REA vaccination exhibited unprecedented protective efficacy against MTB challenges, suppressing bacterial growth to undetectable levels 16 weeks post-infection. The vaccine’s efficacy mechanism involves T cell activation with potent bactericidal activity, induced by REA-activated dendritic cells and macrophages, as demonstrated both in vivo and in vitro. REA also promotes M1 macrophage polarization and sustained Th1 and Th17 responses in tissues. Its efficacy correlates with antigen-specific multifunctional IFN-γ+IL-2+TNF-α+CD4+ T cells and long-lasting T cells producing IL-2 and IL-17 in tissues. These findings represent a paradigm shift in TB vaccine development by targeting both macrophage and dendritic cell-mediated immunity. REA’s superior protective efficacy compared to BCG in our mouse models, combined with its defined composition as a subunit vaccine and reduced molecular weight that facilitates manufacturing, positions it as a promising candidate to either replace or boost BCG vaccination. While additional studies in different animal models and comprehensive safety assessments will be required before clinical development, the remarkable efficacy demonstrated by REA in eliminating MTB infection provides strong justification for pursuing its development as a next-generation TB vaccine.

Methods

Study design

The objective of this study was to develop a novel MTB fusion protein vaccine against TB. The individual subunits were selected based on their previous track record of immunogenicity and their ability to stimulate the cellular arm of the immune system. To construct and optimize the immunogenicity of recombinant Rv2299cD2D3-ESAT6-Ag85B fusion protein, we changed protein order from Rv2299c-Ag85B-ESAT6 vaccine27 to REA and removed the non-immunogenic N-terminal D1 domain of Rv2299c28.

Ethics statement

For the animal studies, the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chungnam National University, South Korea (Permit Number: CNU-00284) approved the protocol, and all the animal-related experiments were conducted strictly in accordance with the standardized Korean Food and Drug Administration (KFDA) guidelines for animal care and use.

Mice

Specific pathogen-free, 5–6-week-old, female C57BL/6 and C57BL6 OT-II TCR transgenic mice, obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were utilized in this study. All the mouse groups were maintained under barrier conditions in the ABSL-3 facility at the Medical Research Center of Chungnam National University (Daejeon, Korea) with constant temperature (24 °C ± 1 °C) and humidity (50% ± 5%). The animals were fed with a sterile regular diet and ad libitum access to water under standardized light-controlled conditions (12 h light and 12 h dark intervals).

Cell culture

Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) and bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were cultured and prepared as previously described50. Briefly, flushed from the femurs of mice, then RBC were lysed. After washing the cells, the total cells were suspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Welgene Co., Daegu, Korea) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 ng/ml mouse macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF; Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), and 1% antibiotics (Welgene). Finally, cells were plated in 100-mm plates and incubated for 7 days at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were cultured at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2 using Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 media supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% antibiotics (Welgene), 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol, 5 mM HEPES buffer, 1% MEM solution, 20 ng/ml granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and 5 ng/ml IL-4. The nonadherent cells and loosely adherent proliferating DC aggregates were harvested on days 7 or 8 and were used for further experiments.

Bacterial culture

MTB H37Rv (ATCC 27294) and H37Ra (ATCC 25177) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). M. bovis BCG (Tokyo strain) was kindly provided by the Korean Institute of Tuberculosis (KIT). All the mycobacteria were grown in 7H9 medium supplemented with 0.5% glycerol, amphotericin B, 0.05% Tween-80 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), and 10% oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase (OADC; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) cultivation media, harvested and aliquoted into cryovial tube, and frozen at −80 °C freezer for further use. Experiments involving MTB were carried out in a biosafety level 2 (BSL2) laboratory. In addition, the red fluorescent protein (RFP) expressing MTB (RFP-MTB) was constructed in this study as previously described17.

Expression and production of recombinant protein

To produce the REA protein, the corresponding genes (ESAT6, Ag85B, and Rv2299c) were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from the genomic DNA of MTB using specific primers (Table 1). The PCR products were sequentially cloned into pET22b(+) vector (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA) as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1A. The final recombinant plasmid containing REA was transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL21 cells, and the protein was purified using Ni-NTA resin as previously described (33105734). Endotoxin was removed using polymyxin B-agarose, and protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The purity, cytotoxicity, and endotoxin decontamination were validated before subsequent experiments (Supplementary Fig. 1). The amount of residual LPS in the REA preparation was evaluated using the Limulus amoebocyte lysate (LAL) test kit (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cytotoxicity analysis

Cell viability was assessed using Annexin V/PI, CCK-8, and LDH assays according to the manufacturers’ instructions (BD Biosciences, Dojindo Laboratories, and Takara, respectively).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Cytokine levels were measured by sandwich ELISA following manufacturer’s protocols (eBioscience).

Measurement of ROS

The intracellular ROS levels were evaluated by staining the cells with H2DCFDA (Molecular Probes). BMDMs were stimulated with the recombinant REA protein and incubated with 10 μM H2DCFDA in PBS for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark and then washed with PBS. Samples were immediately analyzed on a FACS Canto II cytometer and the data were processed using FlowJo.

In vitro T-cell proliferation assay

Responder T cells were isolated as described above. OVA-specific CD4+ T cells, the responders, were isolated from OT-2 mouse splenocytes, respectively. These T cells were stained using 1 μM CFSE (Invitrogen) as previously described51. BMDCs that had been treated with OVA peptide in the presence of REA for 24 h were co-cultured with CFSE-stained CD4+ T cells at a DC:T cell ratio of 1:10. On the 3rd day of co-culture, each T cell set was stained using PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated anti-CD4 and was analyzed using a flow cytometer. The supernatants were harvested, and the contents of IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-17A, and IL-4 were determined using ELISAs.

Cell surface staining and flow cytometry

Antigen-treated BMDMs or BMDCs with or without infection were harvested, washed, and stained using specifically labeled fluorescent-conjugated Abs (mAbs directed against CD80 (16-10A1), CD86 (GL1), MHC class I (34-1-2S), and MHC class II (I-A/I-E, M5/114.15.2), from eBioscience) and the staining intensity was determined using flow cytometry (NovoCyte) and data were analyzed using FlowJo data analysis software (BD Bioscience). To determine cell surface molecules during infection, BMDMs were infected with MTB H37Rv (1 × 105/well) for 4 h and then treated with antigen stimulant for 72 h.

Treatment of BMDMs with pharmacological inhibitors of signaling pathways

Pharmacological inhibitors (U0126, SB203580, SP600125, and Bay11-7082) were used at optimized concentrations as previously described18. Cell viability was monitored using MTT assay.

Immunoblotting analysis

Activated/inhibited/transfected BMDMs or BMDCs were collected, lysed in RIPA buffer (containing Tris-HCl, EDTA, NaCl, Triton X-100, PMSF, protease, and phosphatase inhibitors), and centrifuged at 13,475 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. Protein concentrations were measured with the Bradford assay. Equal protein amounts were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were blocked in 0.1% TBS/T with 5% non-fat milk, incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Target proteins were detected using chemiluminescent substrates and imaged with a BioRad ChemiDoc system.

Gene silencing by small interfering RNA (siRNA)

PI3K was silenced using specific siRNAs (200 nM) transfected into BMDMs using Lipofectamine 2000 according to manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Scientific).

Intracellular survival of MTB

BMDMs were infected with MTB at a 1:1 ratio for 4 h, then treated with amikacin (200 μg/ml) for 2 h and washed. BMDMs and BMDCs were then treated with REA (5 μg/ml) for 24 h and co-incubated with BCG-vaccinated splenocytes for 3 days. Macrophage cultures were dissolved in 0.1% saponin, and bacterial burden was determined by plating serially diluted supernatants and cell lysates on 7H10 agar with 10% OADC.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

The maturation of MTB-containing phagosomes was tracked by analyzing the co-localization of RAB5, hVPS34, EEA1, RAB7, and LAMP1 as previously described17. Briefly, BMDMs were infected with RFP-H37RV (MOI 1) and treated with LPS, Rv2299c, or REA. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with appropriate primary and secondary antibodies following immunofluorescence protocols17. Lysosomal quantification was performed using LysoTracker Green (Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Images were acquired using a confocal microscope.

Evaluation of vaccine efficacy protocol

Immunization

Six-week-old female C57BL/6 mice (9 mice/group) were injected three times with 0.2 ml of recombinant REA (5 μg) chimeric protein at 2-week intervals using dimethyldioctadecylammonium liposomes (DDA/250 μg; Sigma) containing monophosphoryl lipid-A (MPL/25 μg; Sigma) adjuvant, or 250 μg DDA/ 25 μg MPL mix, or BCG subcutaneously over the shoulders, into the loose skin over the neck. Mouse in BCG (1 × 104 or 1 × 105 CFU) group was received a single dose of BCG.

Challenge

After 6 weeks of the last subcutaneous vaccination, the C57BL/6 mouse in each group was challenged with H37Ra or H37Rv strain of MTB through intra-tracheal installation. Briefly, following anesthetization with 1.2% 2,2,2-tribromoethanol (Avertin; Sigma), each mouse received 50 μL-1 of 1 × 106 CFU MTB H37Ra strain or 1 × 103 CFU MTB H37Rv strain intra-tracheally after small ventral midline cervical incision exposed in the tracheal cartilage rings caudal to the larynx. Immediately after challenge the opened skin was sutured in place to prevent infection. Intra-tracheal route of tuberculosis infections was performed in the Class II type B2 (total exhaust) biological safety cabinet (ESCO, Soule, Korea).

Bacterial enumeration

Mice were euthanized with CO2, and lungs were homogenized. The number of viable bacteria was determined by plating serial dilutions of the organ homogenates onto Middlebrook 7H10 agar (Difco, USA) supplemented with 10% OADC (Difco, USA) and amphotericin B (Sigma Aldrich, USA). Colonies were counted after 4 weeks of incubation at 37 °C.

Intracellular cytokine staining

Single cell suspensions of the lungs and spleens were prepared as previously described50. Briefly, single cell suspensions (1 × 106 cells) from infected or immunized mice were stimulated with REA (2 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 9 h in the presence of GolgiPlug and GolgiStop (BD Biosciences). For phenotypical analysis, single cell suspensions were stained with the following antibodies; ThermoFisher Scientific: Live/Dead Fixable Lime 506; BD Biosciences: anti-CD4 (RM4-5)-BV605, Then, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained intracellularly with following antibodies; BD Biosciences: anti-IFN-γ (XMG1.2)-PE, anti-IL-2 (JES6-5H4)-APC, anti-TNF-α (MP6-XT22)-PE-Cy7.

Histopathology

For histological analysis, lung tissues were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), acid-fast bacilli (AFB), and immunohistochemical methods using specific antibodies (F4/80, iNOS, MHC-II, CD163, Arginase-1, CD11c). The sections were deparaffinized, treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide, and incubated overnight at 4 °C with rabbit antibodies (F4/80, Cell Signaling; D2S9R, iNOS, Invitrogen; PA3-030A, MHC-II, Invitrogen; PA5-116376, CD163, Bioss; Bs-2527R-cy5, Arglnase-1, Invitrogen; PA5-32267, CD11c, Invitrogen; PA5-79537). Envision peroxidase reagent was then applied. Granuloma areas, bacterial counts, and positively stained cells were measured using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Statistical analysis

At least three independent experiments were conducted to obtain an individual result. For statistical analysis, data obtained from independent experiments (mean ± SD) were analyzed using Tukey’s test for post hoc multiple comparison test distribution or two-way repeated measure ANOVA using statistical software (GraphPad Prism Software, version 6; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical significance was indicated as *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001 and not significant (p > 0.05).

Responses