Occurrence characteristics and transport processes of riverine microplastics in different connectivity contexts

Introduction

Microplastics, which are plastic particles smaller than 5000 µm, are widely found in aquatic environments1,2. Their persistence and bioaccumulation have raised significant concerns about their impact on aquatic ecosystems and human health through the food chain3,4. Recent studies have even detected microplastics in human blood and organs5,6. In recent years, the focus of microplastic studies has gradually shifted from the oceans to inland river environments7,8. The occurrence characteristics of microplastics have been studied in great detail in many rivers, and it is clear that traces of microplastics have been found even in less visited highland rivers9,10. These traced microplastics were likely transported to the sampling site rather than discharged from it11,12. For this reason, rivers are considered to be the most important transport channels for microplastics in connected water systems13,14. This is especially true for large rivers, which carry 70–80% of terrestrial plastic waste to the oceans15. However, there is still a relatively limited understanding of the occurrence, transport, and fate of riverine microplastics compared to marine microplastics.

River damming is a global phenomenon that can result in reduced river mobility. It is estimated that river damming has not only caused 63% of the world’s longest river have lost their free-flowing status, but has also led to a reduction in mobility for 48% of the world’s rivers16,17,18. Nevertheless, as of January 2024, only 18 out of 750 published studies on riverine microplastics relate to dams, indicating a significant gap in this area of research. Compared to natural rivers, river damming reduces the natural flow dynamics of rivers, which in turn weakens the transport capacity of organic matter, particulate matter, and silt in the river19,20. Microplastics, as typical particulate pollutants, are transported in solid form through rivers, and their environmental behavior is strongly controlled by hydrodynamics21,22. Relevant studies have demonstrated that artificial damming can disrupt river connectivity and potentially further affect the capacity of rivers to transport and retain of microplastics by altering river hydrological processes and environmental factors23,24,25. Given the critical regulatory role of river mobility in riverine substance transport, it is considered that this may also significant impact the spatial distribution, transport behavior, and depositional processes of riverine microplastics12,26,27. Therefore, it is crucial to clarify the differences in the spatial distribution, local hotspot formation, and retention processes of river microplastics in different connectivity contexts, which can provide a scientific basis for achieving source reduction and process retention of microplastics in the river catchment.

This study investigates the occurrence characteristics and transport processes of microplastics in the water column and sediments of three reaches with different connectivity characteristics: multi-dammed river, single-dammed river, and nondammed river. Meanwhile, this study performed a preliminary assessment of riverine microplastic emissions and storage based on the occurrence characteristics of riverine microplastics. This study aims to: (1) to analyze the spatial heterogeneity of microplastics in waters and sediments of rivers with different connectivity; (2) to explore potential sources and drivers of microplastic hotspot formation under different connectivity contexts; (3) to quantify the sequestration and export of riverine microplastics in different connectivity contexts. This study quantifies, for the first time, the formation of microplastic hotspots and their transport processes in rivers under different connectivity contexts based on the variation characteristics of microplastic fluxes and stocks, which provides some new information on the regulation of riverine microplastic transport processes by dams.

Results and discussion

Spatial distribution of riverine microplastic abundance

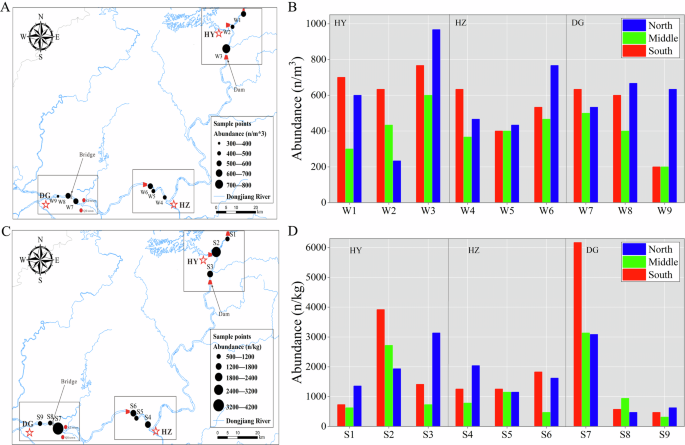

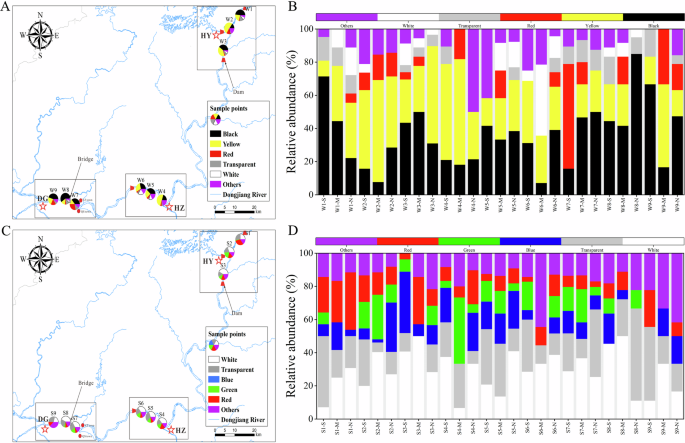

Microplastics were widely detected in water columns and sediments at all sampling sites. The average abundance of microplastic in the water column was 581.48 ± 229.80, 496.30 ± 129.58, and 485.19 ± 181.13 n/m3 in the multi-dammed river (HY), single-dammed river (HZ), and non-dammed river (DG), respectively, while the average abundance of microplastics in the sediments was 1840.82 ± 1179.33, 1283.35 ± 491.04, and 1753.71 ± 1995.10 n/kg, respectively (Fig. 1). The peaks of microplastic abundance in the water column and sediments were found at W3 (777.78 n/m3) in the dam reservoir of HY and S7 (4128.78 n/kg) downstream of the town of DG, respectively. The abundance of microplastics in the waters and sediments of the Dongjiang River was relatively higher compared to rivers in other regions of the world (Supplementary Table 1). In dammed rivers (HY and HZ), microplastics in the water column tend to accumulate in the reservoir area (W3 and W6) with lower flow velocities (Supplementary Table 2). This means that artificial dams can be effective in intercepting river microplastics. On the contrary, the microplastic abundance in the water column decreased gradually during the fluvial process in the non-dammed river (DG)28. Sediments are considered a long-term sink for microplastics in rivers29. In general, microplastic hotspots in sediments are formed adjacent to the pollution source (S2, S4, and S7)11. The abundance of microplastics in sediments gradually decreases as it moves away from the source of contamination13. Notably, the abundance of microplastics in the riverbed S7 of the non-dammed river (DG) has formed a high hotspot, which may be related to the significant reduction in water velocity due to channel widening. Interestingly, in the single-dammed river (HZ), the microplastic abundance was lower in the significantly wider channel S5. One possible explanation is that S5 was located in a meandering section of the river, where river turns resulted in faster water velocities, promoting the discharge of microplastics from the riverbed rather than their sequestration.

A–B Water samples; C–D Sediments.

Riparian zones may also function as potential sinks for riverine microplastics. Microplastic abundance in the central portion of the river water column was lower than on either side of the river in eight of the nine cross-sections and in the central sediment in six of the nine cross-sections. Our data show that flow velocities are generally greater in the middle of the river than on either side of the river (Supplementary Table 2), which could adversely affect the retention of microplastics in the middle of the river. The results demonstrate that microplastics tend to accumulate on both sides of the river at the same cross-section in both dammed and non-dammed rivers. Research indicates that the interaction between riparian zones and river water can result in the formation of reflux or eddy zones along rivers10,30. These zones may serve as hotspots for the aggregation of microplastics in the water column, leading to increased microplastic deposition22,31. Consequently, future research should emphasize the significant role of the riparian zone in the riverine transport of microplastics. It is noteworthy that the microplastic abundance in W2 and S2 decreases progressively from the north to the south side of the river, which may be related to urban microplastic inputs from the north side. This observation indicates that anthropogenic activities remain the primary factor in the formation of microplastic hotspots in urban areas21.

Spatial distribution of riverine microplastic sizes

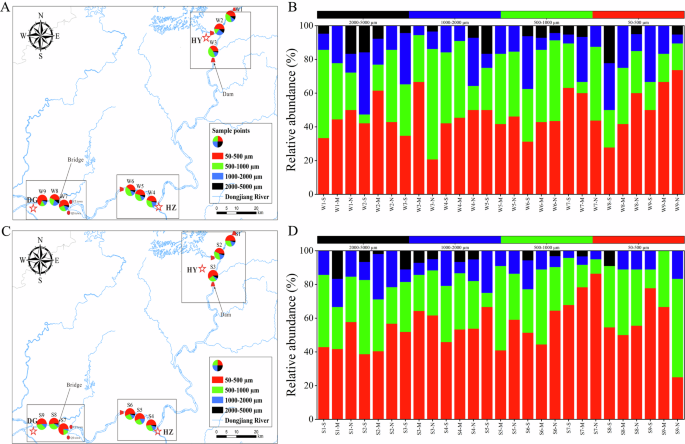

Microplastics in the water column and sediment were predominantly small-sized (50–500 µm) with proportions ranging from 37.14–67.74% and 43.29–75.11%, respectively (Fig. 2). The proportion of small-sized microplastics was generally higher in sediments compared to the water column, particularly in the nondammed river (DG). This phenomenon may be associated with hyporheic exchange at the water-sediment interface8. Turbulence, driven by river topography and the interaction of different water layers, led to substantial hyporheic exchange, which facilitated the retention of small-sized microplastics in streambeds32. The study found that small-sized microplastics were transported like natural sediments22. In dammed rivers (HY and HZ), the proportion of small-sized microplastics in the water column decreased from the upstream (41.67% and 45.45%) to the dammed reservoir (37.14% and 39.62%). In non-dammed rivers (DG), the proportion of small-sized microplastics in the water column instead increased (56.00% to 67.74%). In sediments, the proportion small-sized microplastics in HY and HZ showed gradual accumulation from upstream (50.00% and 51.28%) to dam reservoirs (59.41% and 56.00%), while DG showed a gradual decrease during the fluvial process (75.11% to 51.85%). The results show that small-sized microplastics are more likely to be retained in the riverbed than in the river water, regardless of whether the river is dammed or non-dammed. In addition, the data showed that out of the 9 cross-sections, 5 cross-sections of water and 6 cross-sections of sediment exhibited higher proportions of small-sized microplastics on the northern side of the river, followed by the central region. River centripetal forces may be a key factor contributing to the accumulation of small-sized microplastics on the north side, though this hypothesis requires further validation through additional studie31.

A–B Water samples; C–D Sediments.

Spatial distribution of riverine microplastic shapes

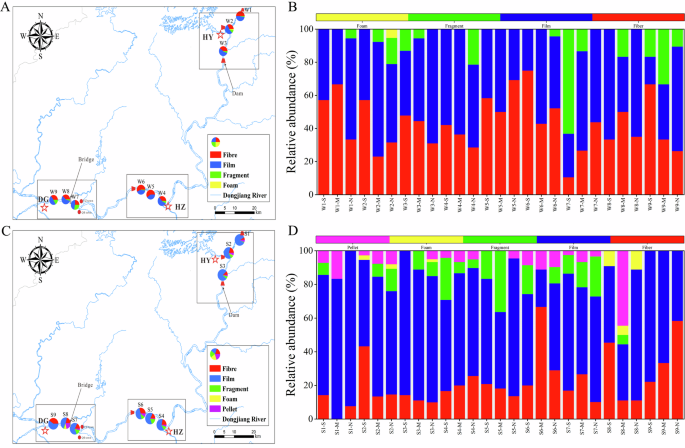

Four microplastic shapes (films, fibers, fragments, and foams) were detected in the water column, and five microplastic shapes (films, fibers, fragments, foams, and particles) were detected in the sediment (Fig. 3). In the water column, the microplastic shapes of HY was dominated by films (52.23%) and fibers (41.40%), while HZ was dominated by fibers (50.75%) and films (46.27%). The microplastics in DG were predominantly films (51.15%) and fibers (32.82%), while the proportion of fragments (16.30%) increased significantly. The results showed that the proportion of film and fiber microplastics in river water was higher in the dammed rivers (HY and HZ) with low river mobility, while the proportion of fragment microplastics was significantly higher in the non-dammed river (DG) with high river mobility. The shape of microplastics is considered to be an important factor influencing environmental behavior. Studies have shown that film and fiber microplastics typically have higher surface tension than fragment microplastics32. As a result, film and fiber microplastics are more easily floated on the river surface, whereas fragment microplastics are more likely to be deposited in the riverbed. In contrast, there was a significant increase in the proportion of fragment microplastics in the river water at the DG reach, which may be related to the high hydraulic disturbance due to the river’s high mobility10. Meanwhile, the high proportion of fiber microplastics in the river water at HY and HZ may also be related to the large discharge of washing wastewater, as HY and HZ are well-known tourist resorts11,20. Additionally, as crucial agricultural production regions, HY and HZ use a large amount of plastic agricultural films in the agricultural production process, which leads to large substantial film microplastic emissions. Although DG was equally dominated by films and fibers, there may have been differences in their origins. Fibers may be sourced from the textile industry, while films may originate from the logistics or packaging industries, as DG is an industrial and textile base12.

A–B Water samples; C–D Sediments.

The microplastic shapes in HY (70.66%), HZ (57.92%), and DG (60.93%) were dominated by films in the sediments. It is noteworthy that the proportion of film (70.66% and 57.92%), fragment (7.26% and 13.57%), and pellet (5.36% and 5.43%) microplastics in sediments was significantly higher in the dammed rivers (HY and HZ) with low river mobility. Lower surface tension and resistance coefficients favor deposition rather than their floating fragment microplastics, and the same is true for particle microplastics32. The increase in the proportion of film microplastics may be related to biofouling because films has a larger specific surface area than other shapes of microplastics33. In addition, the proportion of fiber microplastics in sediments was significantly lower compared to that in the water column, which may be related to their terminal settling velocity. The study showed that the terminal settling velocity of fiber microplastics was, on average, 7 times lower than predicted by the reference law, while the terminal settlement velocity of other shapes of microplastics was on average 3 times lower than predicted by the reference law32. This means that fiber microplastics are more likely to be retained in the water column than to be deposited in streambeds, and predict that fiber microplastics pose a higher ecological risk than other shapes of microplastics due to their strong migratory properties.

Spatial distribution of riverine microplastic types

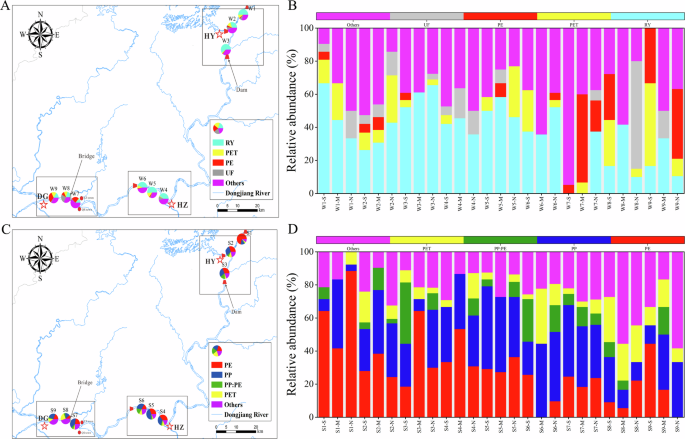

In this study, all particles on the filter membrane were scanned and 1614 particles were studied in detail using micro-infrared (Supplementary Table 3). In the water column, 422 out of 764 particles were identified as microplastics, with a detection rate of 55.24%. In the sediments, 840 out of 850 particles were identified as microplastics with a detection rate of 98.82% (Supplementary Table 4). A total of 33 polymer types were detected in all microplastics, 16 in the water columns, and 33 in sediments. The microplastic types were dominated by RY (49.68%), RY (44.78%), and others (42.75%) followed by PET (35.03%), others (41.04%), and PE (20.61%) in the water column for HY, HZ, and DG, respectively (Fig. 4). The results showed that there were significant differences in microplastic types in the water column of rivers with different connectivity, which may be related to variations in river mobility. Artificial damming can weaken the mobility of rivers as well as potentially lead to further reorganization of microplastic types in the water column. Interestingly, the high proportion of RY in HY and HZ may be closely related to the massive amounts of washing wastewater input. Studies have shown that washing wastewater usually contains large amounts of RY fiber because RY is used widely in everyday life and clothing fashion31,34. The data show that 67.92% of the RY microplastics in the water column were fibers, with 87.96% of RY fibers coming from HY and HZ. This indicates a strong correlation between the high percentage of RY microplastics and washing wastewater. In contrast, DG was dominated by other types of microplastics, likely due to frequent human activities leading to multiple sources of microplastics. DG also found a significant percentage of RY (16.03%), which may have come from dam discharge upstream of HZ. Washing wastewater may also be an important source of RY in DG, a densely populated area and an important textile industrial area. The lower proportion of RY in river water at DG compared to HY and HZ indicates that RY microplastics tend to be retained in river water in the dammed river with low river mobility.

A–B Water samples; C–D Sediments.

The microplastic types were dominated by PE (37.54%), PP (35.75%), and PP (34.77%) followed by PP (27.44%), PE (27.60%), and others (29.47%) in the sediments of HY, HZ and DG, respectively. The compositions of microplastic types in river sediments from different connectivity contexts were consistent, which indicates that the effects of river damming on microplastic types in sediments were relatively small. The high proportion of PE and PP can be attributed to their widespread use worldwide. The proportion of other types of microplastics in DG further increased to 29.47%, consistent with the trend of microplastic types in the water column of DG. This increase is primarily due to the multi-source nature of microplastic inputs from urban areas. Notably, microplastics in the water columns of HY and HZ were dominated by RY, whereas in the water column of DG, they were dominated by others. This is a significant difference from the microplastic types found in the sediments. One possible explanation is that microplastics in the water column may be influenced by hydrological processes and short-term inputs, while sediments may result from long-term accumulation of riverine microplastics11,29. In addition, a large amount of RY was detected in the water column, whereas relatively little RY was detected in the sediment. This further supports the previous hypothesis that RY microplastics are more likely to be floated or suspended in the water column than to be deposited in sediments, especially in a dammed river with low river mobility.

Spatial distribution of riverine microplastic color

There were significant differences in the color of microplastics in the water of rivers with different connectivity, whereas the color differences in sediments were relatively minor. The color of microplastics in river water from HY and HZ was dominated by yellow (37.58% and 35.07%), followed by black (36.31% and 28.36%), respectively (Fig. 5). The color of microplastics in river water from DG was dominated by black (47.33%), followed by yellow (16.03%). Conversely, in the sediments of HY, HZ, and DG, microplastics were predominantly white (29.34%, 29.41%, and 30.13%), followed by clear (17.35%, 20.81%, and 24.50%). The results showed that microplastic color differences in the river water were relatively significant, whereas the color composition in the sediment was very similar. Microplastics in the water column are typically recent additions to the aquatic environment and have retained their original bright colors10. Conversely, microplastics in sediments may gradually fade to white or clear due to long-term physical-biochemical processes. Photo-oxidation can cause plastics to gradually change color to white or transparent when exposed to sunlight or UV radiation13,25. Additionally, the molecular structure of plastic can be altered by aging, pyrolysis, and chemical degradation of microplastics, impacting their color and transparency1,27. It is noteworthy that microplastics in the water column may present a higher ecological risk than those in sediments due to their bright colors, warranting widespread concern. The study indicates that the color of microplastics may lead to accidental ingestion by aquatic organisms, as some visual predators prefer to ingest brightly colored food4.

A–B Water samples; C–D Sediments.

Impact of river mobility on microplastic loading

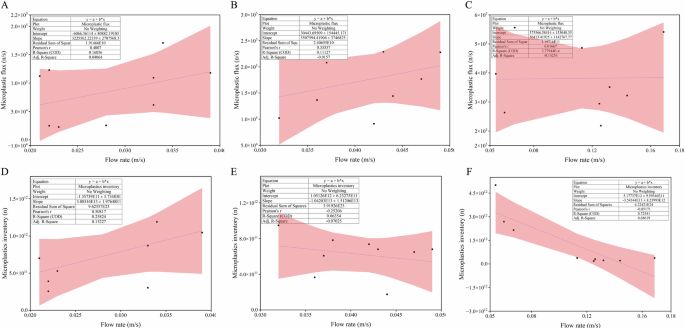

Flow velocity is considered to be a key environmental factor that influences the sequestration and export of microplastics from rivers. Our data show that river flow rates decrease significantly as the number of dams increases. In the dammed rivers (HY and HZ), increased water flow rates favored the retention of microplastics in the river water (Fig. 6A–B). In undammed rivers (DG), the effect of increased water flow rates on the retention of microplastics in river water was not significant (Fig. 6C). This implies that artificial damming can be effective in promoting the retention of microplastics in the water column, and the retention effect may be positively correlated with the number of dams. In contrast, in non-dammed rivers (DG), the amount of microplastics in the streambed was significantly negatively correlated with the water flow rate (R2 = 0.6861). In single-dammed rivers (HZ), microplastics in the riverbed were similarly negatively correlated with water flow rates. Significant differences in the correlation between microplastics and water flow rate in the streambed of single-dammed rivers (HZ) and non-dammed rivers (DG) may be related to the altered hydrodynamic conditions of the rivers due to artificial damming (Fig. 6E–F). Artificial damming impedes material transport in rivers and potentially inhibiting the export of microplastics from riverbeds2,18. Meanwhile, river steering, channel widening, and riverbed raising may also affect river hydrodynamic conditions25,31. However, microplastics in the streambed of multi-dammed rivers (HY) were positively correlated with water flow rates, which may be related to changes in channel characteristics caused by the multiple dams (Fig. 6D). The multi-dammed river (HY) has formed a structure similar to a stormwater pond, which is effective in the retention of microplastics35. Our results demonstrate that artificial damming can weaken river mobility, which in turn favors the retention of riverine microplastics.

A–C Correlation of microplastic flux with flow rate in HY, HZ, and DG reaches; D–F Correlation of microplastic inventory and flow velocity in HY, HZ, and DG reaches.

The correlation between microplastic counts and environmental factors in rivers with different connectivity also differed to some extent (Supplementary Fig. 1). Correlation analyses showed that microplastics in sediments were positively correlated with the water column, suggesting a common source. Microplastics commonly originate from anthropogenic activities. Microplastics from land-based sources enter the water column either floating or suspended and are then gradually deposited on the riverbed during the fluvial processes9,34. The microplastic count in the HY reach was positively correlated with many environmental factors such as conductivity, pH, and dissolved carbon content. Dissolved carbon content can affect the fluidity and mixability of the water column, thereby affecting the transport and dispersion of microplastics in the water column23. The microplastic count in the HZ reach was only positively correlated with conductivity. Conductivity may affect the adsorption and aggregation behavior of microplastics in rivers, and could even influence the degradation process of microplastics1,34. The microplastic count in the DG reach was positively correlated with TP and TN. The presence of nitrogen and phosphorus may be related to human activities, but also to the release of microplastics11,12. In addition, our results indicate that small-sized microplastics (50–500 µm), low-density microplastics (PE), fragmented microplastics, and red microplastics were more likely to show a positive correlation with environmental factors, while other types of microplastics exhibited weaker or possibly negative correlations. This suggests that the abundance of small-sized and medium-sized microplastics, low-density microplastics, and fragmented microplastics in rivers increases with changes in environmental factors such as water temperature, DIC, DTC, and SPC.

Principal component analysis showed that the two components were adequate in explaining the majority of the baseline variation (78.4–84.5%) (Supplementary Fig. 2). The results show that microplastics and natural sediments of different sizes have similar distribution trends (Supplementary Table 5). Based on this, this study hypothesizes that microplastics in sediments may have hydrodynamic properties similar to those of natural sediments. However, there is some degree of variability in the size distribution of microplastic in sediments and natural sediments in different regions, which may be related to variations in river mobility. Of course, given the lower density of microplastics, their shear force to initiate migration may be lower, which in turn may also lead to the size differences between microplastics and natural sediments. This finding emphasizes the importance of physical properties such as size and density, in comprehending the migration behavior of microplastics.

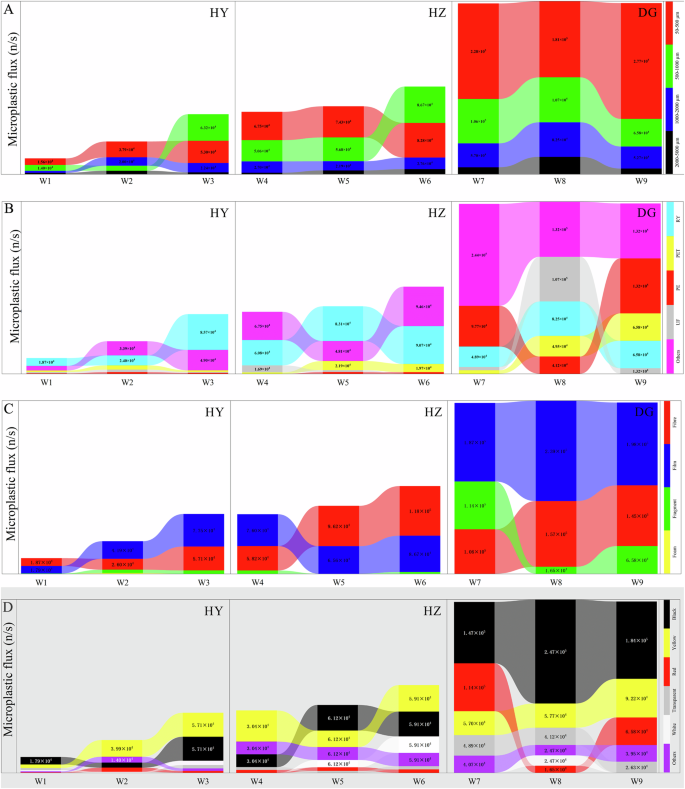

Characteristic changes in riverine microplastic fluxes

There were also significant differences in microplastic fluxes in rivers with different connectivity characteristics. Microplastic fluxes in the dammed rivers (HY and HZ) showed a progressive increase towards the dam reservoirs, while the difference in microplastic flux in the non-dammed river (DG) was smaller. Artificial damming can weaken river mobility, which in turn leads to the formation of microplastic hotspots in rivers. In the multi-dammed river (HY), the microplastic flux in the HY showed a stepwise increase from the upstream W1 to the downstream W3. Microplastic flux was low in W1 mainly due to the upstream being blocked by the dam. The runoff in W1 (70.21 m3/s) was far lower than in W2 (179.66 m3/s) and W3 (183.62 m3/s) due to the lack of incoming water. Low runoff resulted in low microplastic flux, although its microplastic abundance remained at a medium level in this study. Microplastic pollution increases gradually as the river flows through the urban area (W2), reaching a peak in the dam reservoirs31. W4 and W1 are equally located in the upstream area of the reach, but W4 has a significantly higher microplastic flux. Unlike the multi-dammed river (HY), the HZ is a single-dammed river with abundant incoming water from its headwaters. The incoming water carried a huge amount of microplastics. Meanwhile, large inputs of microplastics from upstream urban areas may also increase microplastic pollution at cross-section W4. This means that there is an accumulation of microplastics in river water due to reduced river connectivity. In addition, the microplastic fluxes at the DG river reach were comparable at each cross-section, which may be related to the gradual increase of microplastic inputs from land-based sources as the reach becomes closer to the urban center21,31.

There were equally significant differences in the multi-category fluxes of microplastics from different connectivity rivers. In the dammed rivers (HY and HZ), there was a tendency for microplastics of different sizes in the river water to accumulate in the downstream reservoirs, implying that artificial damming favors the accumulation of microplastics of all sizes. On the contrary, the trends of microplastics of different sizes in the river water of the non-dammed river (DG) were essentially consistent and did not show accumulation. Interestingly, the high flux of 500–1000 µm microplastics in the dammed rivers (HY and HZ) may be related to the high discharge of RY fibers. Our data indicate that the main size of fiber microplastics in HY and HZ waters was 500–1000 µm. Dam reservoirs are also recognized as potential sinks for all types of microplastics (HY and HZ), while others type of microplastic have more potential to form hotspots in peri-urban areas (W2, W4, and W7). RY microplastic fluxes in the HY and HZ gradually increased from upstream to downstream and peaked in the reservoir area. This also shows that RY microplastics are more likely to be retained in the water column in the dammed rivers but not in the non-dammed river. The proportion of fiber and film microplastics was considerably higher in the dammed rivers (HY and HZ) than in the non-dammed river (DG), demonstrating that fiber and film microplastics are more commonly retained in the water column in slow-moving, closed waters. Fragment microplastic contamination was normally higher in water bodies closer to the source of contamination, which may be related to the multi-source nature of urban microplastics. The reduced flux of fragment microplastics in the high flow rate region may be associated with hyporheic exchange processes8. Size analysis showed that 85.29% of the fragment microplastics were smaller than 500 µm and that these small particles are more likely to enter the riverbed through hyporheic exchange. Different colors of microplastics in the river water gradually accumulated towards the dam reservoir in the dammed rivers (HY and HZ), whereas the non-dammed river (DG) did not exhibit a distinctive feature.

The trends in microplastic fluxes were significantly different from those in microplastic abundance. In terms of microplastic abundance, HY was the most contaminated, with an average abundance of 581.48 n/m3, followed by HZ with 496.30 n/m3 and DG with 485.19 n/m3. However, microplastic flux analyses showed that DG was the most contaminated with an average flux of 40.92 × 104 n/s, followed by HZ with 17.31 × 104 n/s and HY with 8.60 × 104 n/s (Fig. 7). If only the abundance of microplastics is considered, HY would be identified as the area with the highest microplastic contamination. In contrast, if microplastic flux results are used as a benchmark, DG is the most contaminated with microplastics. However, reported microplastic studies primarily used microplastic abundance as the main reference indicator for assessing the degree of microplastic contamination, which may have a detrimental effect on the management and assessment of microplastics in catchments and globally2,7,11. It is important to note that microplastic abundance hotspots do not necessarily correspond to microplastic flux hotspots. For example, the microplastic abundance in W1 (533.33 n/m3) in this study was approximately 1.55 times higher than that in W9 (344.44 n/m3), while the microplastic flux in W1 was only 9.17% of that in W9. Microplastics can be retained in localized areas due to various environmental factors during river transport. This can result in the formation of hotspots of microplastic abundance, such as eddies, sewage discharges, and bioaccumulation24,31. In addition, existing studies on microplastics in rivers have mainly considered the abundance of microplastics in surface waters, while studies that consider the microplastic occurrence characteristics of different water layers and regions are still relatively limited10,12. Microplastic fluxes provide insight into the distribution of microplastics throughout the entire river cross-section, offering a more comprehensive understanding of river microplastic pollution.

A Sizes; B Polymer types; C Shapes; D Colors.

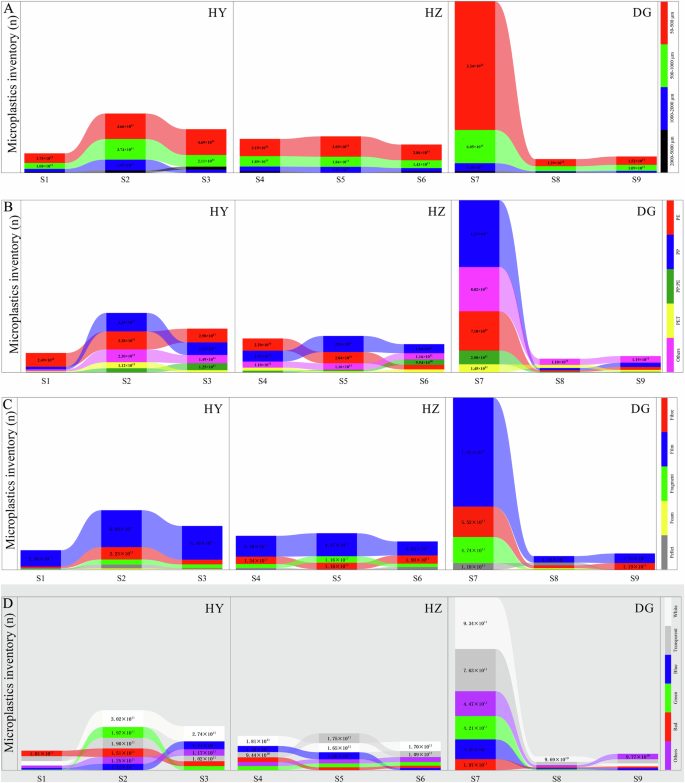

Characteristic changes in riverbed microplastic inventory

The trends in microplastic inventories in riverbeds also reflect the potential of sediments to act as sinks for riverine microplastic. Typically, microplastics from terrestrial sources are preferentially deposited to form hotspots in the riverbed near the pollution source (S2, S4, and S7) after entering the riverine environment. However, the formation of microplastic hotspots (S3 and S6) was also found in the riverbeds of dam reservoirs in dammed rivers (HY and HZ). The results indicate that artificial damming can also contribute to the formation of microplastic hotspots in the riverbed. Notably, the combination of channel widening induced low flow velocities (0.054–0.067 m/s) and urban microplastic inputs led to the formation of a prominent microplastic hotspot at S7. Based on these findings, the low-velocity streambeds of undammed rivers (DG) may also be significant hotspots for microplastic deposition, with inventory up to 10.63–12.71 times higher than those of other riverbeds. The inventory of microplastics at S8 decreased rapidly, which was also associated with the high flow velocities (0.125–0.169 m/s) resulting from channel narrowing. In parallel, the bridge abutments could enhance the hydrodynamic processes of the river by impeding river transport due to S8 is situated downstream of the bridge19. Correlation analysis indicated that the riverbed microplastic inventory was significantly negatively correlated with flow velocity, suggesting that increasing flow velocity favors the export of microplastics from the riverbed. River mobility is the primary factor contributing to the retention of microplastics in rivers. Although both the water column and sediments of dammed rivers can be sinks for riverine microplastics, there are some differences between the two. Microplastics in the water column are more likely to accumulate towards the dam reservoirs, while sediment deposition hotspots are more likely to be close to the source of contamination. Of course, this may also be closely related to the seasonality of the river. During the dry season, mobility in the waters of dammed rivers (HY and HZ) is reduced due to the closure of dams. Low flow velocities facilitate the deposition of microplastics in the water column and the formation of microplastic hotspots in the riverbed close to pollution sources. The dammed rivers can be connected when there is abundant rainfall during rainy seasons. Strong hydraulic flushing may push microplastic hotspots in the riverbed towards downstream reservoirs15. Consequently, future studies should consider the higher temporal resolution and spatial heterogeneity to thoroughly investigate the transport process and retention behavior of microplastics in rivers with different connectivity. This will provide a scientific basis for microplastic management and pollution prevention in the catchments.

There is also some degree of difference between the distribution characteristics of riverbed microplastic inventories and the occurrence characteristics of microplastics. The inventories of small-sized microplastics showed a tendency to increase and then decrease in the dammed rivers (HY and HZ), while the non-dammed river (DG) decreased and then increased, which is the opposite of the results for microplastics sizes. The inventory of film microplastics showed a pattern of increasing and then decreasing in the multi-dammed river (HY), which is also opposed to the shape distribution of microplastics in the region. Meanwhile, large amounts of fragment microplastics were also found in S7, indicating that they are more likely to be deposited in broad riverbeds with slower flow velocities. Interestingly, the area with the highest fragment inventory was S7, followed by S5, which is significantly different from the results of the shape distribution of microplastics. The results show that there are also differences in the characteristic distribution of microplastic inventory in the streambed of rivers with different connectivity, although these differences were much smaller than the microplastic fluxes. Thus, future studies should encourage the quantification of all categories of microplastics in rivers. This is important for a better understanding of microplastic land-sea transport and model simulations.

The inventory and abundance of microplastics in the riverbed exhibited some variability. Both analyses identify microplastic hotspots (S7 and S2) in essentially the same area. However, the results of the two analyses differed somewhat when viewed across different regions. Microplastic abundance analyses showed that HY had the highest concentration of microplastics in the riverbed (1840.82 n/kg), followed by DG (1753.71 n/kg) and HZ (1283.35 n/kg). However, microplastic inventory analyses showed that the DG riverbed had the highest overall amount of microplastics (3.66 × 1012 n), followed by HY (2.22 × 1012 n) and HZ (1.78 × 1012 n). This significant difference was detrimental to the identification of localized hotspots and priority control areas for microplastic contamination in the riverbed (Fig. 8). If the abundance of microplastics is used as a reference indicator, HY would be identified as a priority area for control. Meanwhile, if the results of microplastic abundance identification were used as a baseline to reduce 80% of microplastic pollution in HY riverbeds, the reduction of microplastic pollution in all riverbeds could reach 23.15%. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the inventory of microplastics in the riverbed of HY was only 60.61% of that in DG. If the results of the microplastic inventory identification were used as a baseline to reduce 80% of microplastic contamination in the DG riverbed, its microplastic reduction for all riverbeds would increase to 38.20%. Consequently, it is critical to further consider the variation characteristics of riverbed microplastic inventory as a key to accurately identifying localized hotspots and critical control areas of microplastic pollution, which is essential for watershed comprehensive management and pollution control of microplastics. This is because deposited microplastics can be “remobilized” when hydrodynamic conditions change15,31.

A Sizes; B Polymer types; C Shapes; D Colors.

Methods

Study area

The Dongjiang River is one of the three major water systems in the Pearl River Basin, which is located in the subtropical monsoon humid climate zone, with an average multi-year rainfall of 1500–2400 mm. The Dongjiang River flows from northeast to southwest, with a total length of 562 km, a catchment area of 35340 km2, an average annual runoff of 25.7 billion m3, and a total population of up to 50 million. As the main source of water supply for the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area, the Dongjiang River plays an important role in domestic and industrial water supply. Water resources in the Dongjiang Basin are very scarce, with a per capita water resource of 800 m3, which is only 1/3 of the national per capita water resource23. Despite this, the economy of the Dongjiang Basin is well-developed. In 2022, Dongjiang Water supported a regional GDP of RMB 6.5 trillion, which accounts for approximately 5.40% of the country’s total GDP. This highlights the crucial role of Dongjiang in social and economic development.

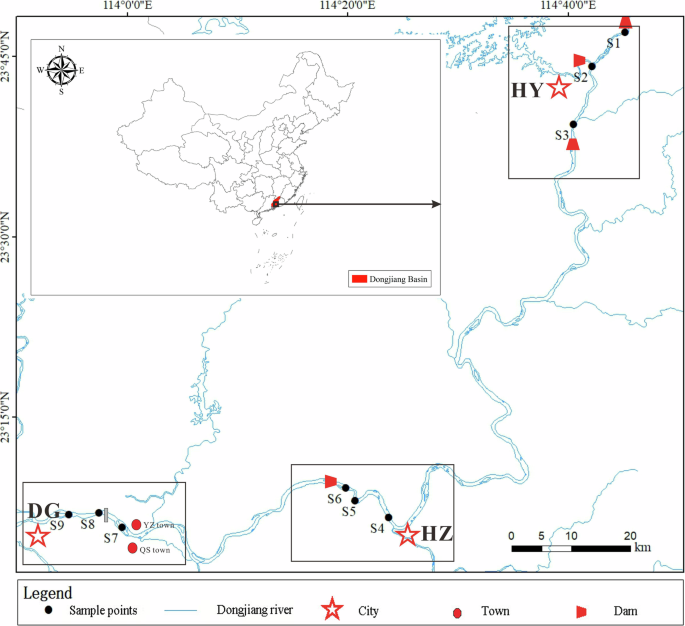

To explore the occurrence characteristics and transport processes of riverine microplastics under different connectivity contexts, three reaches with different channel characteristics in the mainstream of the Dongjiang River were selected for this study, including a multi-dammed river (HY), a single-dammed river (HZ), and a non-dammed river (DG). The upstream and downstream reaches of the multi-dammed river (HY) and its tributaries were all closed by dams. The lower reach of the single-dammed river (HZ) was dammed, while its upper reach remained in its natural flow state. The non-dammed river (DG) is always in a natural flow state (Fig. 9). In this study, one sampling cross-sections was set up in the upper, middle, and lower reaches of each river section, with a total of 9 sampling cross-sections. Sampling points were established at 5 km intervals along the river within the same reach. Then, this study set up one sampling site on the left, center, and right sides of each sampling cross-section, with a total of 27 sampling sites. Within each cross-section, three sampling points (left, center, and right) were positioned at equal intervals based on the cross-sectional width of the river. Sediment and water samples were collected at the same site (Supplementary Table 6). The water samples were labeled “W” and the sediment samples were labeled “S”.

Geographical location and distribution of sampling sites in the Dongjiang River.

Sample collection and pretreatment

The total of 27 river water samples were collected using a column water sampler (5 L, JY-001, Juyi, China). Sub-sample (10 L) was collected from the surface, middle, and bottom layers of each sampling site and the three sub-samples were combined to form a composite river water sample (30 L). River depth was measured using the knotted rope method before sampling. The collected river water samples were concentrated using a stainless steel sieve (50 µm, Lvruo, China). Subsequently, the samples on stainless steel sieves were backwashed with ultrapure water into brown glass bottles (500 ml, Shuniu, China) while 8 ml of formaldehyde solution (AR, Macklin, China) was added to inhibit microbiological growth. The collected water samples were stored in a dedicated refrigerator at 4 °C (180 L, lcers, China).

Sediment samples (approximately 1 kg) were collected from the top 20 cm of the riverbed using a grab bucket (JY-075, Juyi, China). A total of 27 sediment samples were obtained. The sediment samples were wrapped in aluminum foil and subsequently placed in plastic-sealed bags. The plastic bags were stored in a designated refrigerator at 4 °C until they were returned to the laboratory for further processing. In the laboratory, three replicate samples from the same sampling site were placed in the same stainless steel bucket (10 L, TA032, Taia, China) to which 5 L of ultrapure water (8.2 mΩ, Milli-Q Direct 8, Millipore, USA) was added. The sediment mixture was thoroughly stirred with a glass rod for 15 min to ensure homogeneity. The stainless steel bucket was placed in a cool, ventilated area to dry naturally. Following air drying, the top 2 cm of sediment samples were removed to minimize air contamination.

Separation and extraction of microplastics

Water samples were filtered through a stainless steel sieve (5000 µm, Lvruo, China) to remove large plastic fragments. The filtered water samples and the rinsate were collected in 1000 mL beakers. Subsequently, 200 mL of 30% H2O2 solution (AR, Guangzhou Brand, China) was added to the beaker, which was subjected to oxidative digestion at room temperature (19–26 °C) in the absence of light for 24 h to remove organic components from the samples. Upon completion of digestion, the samples were concentrated on glass fiber filter membranes (47 mm diameter, 1.2 µm pore size, GF/B, Whatman, UK) using a vacuum pump. Finally, the filter membrane was placed in an oven (DHG-9015A, Yiheng, China) for continuous drying at 35 °C for 24 h.

Density separation of microplastics in sediments was performed using saturated ZnCl2 solution (AR, Aladdin, China) as the flotation solution29. 20 g of sediment (dry weight) were weighed using an analytical balance and placed in a 1000 mL beaker. Then, 500 mL of saturated zinc chloride solution (1.5–1.6 g/cm3, AR, Aladdin, China) was added to the beaker. The samples were stirred thoroughly for 10-min (200 r/min) using an electric stirrer (JB500-SH, Li-Chen Technology, China). After stirring, the top of the beaker was covered with aluminum foil, and the solution was left to settle for 24 h. When sedimentation was complete, the supernatant was separated. The flotation process was repeated three times to improve the flotation efficiency. The separated supernatant was concentrated on a filter membrane by vacuum filtration. Finally, the filter membrane was dried in an oven at 35 °C for 24 h.

Identification of microplastics

Samples on the filter membrane were observed using an inverted fluorescence microscope (CKX53, Olympus, Japan) with microscope head magnifications of ×10, ×20 and ×40. Adjust the microscope lens to suit the size of the microplastics, and set the light source to bright field mode with an intensity range of 3 to 6. Position the filter membrane under the microscope and begin recording microplastic features after adjusting the lens to ensure a bright and clear image. The size, color, and shape of each suspected microplastic were recorded with Cellsens Dimension software (version 3.22, Germany). Size was based on the maximum length of the particles. All particles were identified for polymer type by micro-infrared spectroscopy (Nicolet IN10, USA) with spectral detection at wavelengths of 400–4000 cm−1, co-adding 128 scans at a resolution of 8 cm−1. Initially, background values were established with a micro-infrared spectrometer using air as the medium. The filter membrane was then positioned under the microscope lens, and each microplastic particle within the frame was scanned individually. The spectra of microplastics obtained from each scan must be subtracted from the corresponding background values to minimize errors. Finally, the acquired spectra were compared against the microplastics database in OMNIC. The type of microplastic was determined when the match rate was greater than 60% (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Estimation of riverine microplastic loads

The average abundance of microplastics in the water body of this study can be representative of the microplastic pollution of the river, as we set up sampling sites in different water layers and regions of each river cross-section (n = 9). The following equations were used to calculate the microplastic fluxes in the river7,9,34:

Where Loadi (n/s) is the number flux of microplastics through cross-section i of the river. Ai is the average abundance of microplastics in the water column at cross-section i of the river (n/m3). Wi is the average width of cross-section i of the river (m). Di is the average depth of cross section i of the river (m). Vi is the average flow rate of cross-section i of the river (m).

Inventory of microplastics in riverbeds

The average abundance of microplastics in the sediments of this study can be representative of the contamination of the riverbed with microplastics, as we deployed sampling sites on the left, center, and right sides of the river (n = 3). This study relied on two assumptions when calculating the inventory of microplastic in riverbed sediment. Firstly, this study assumed that the distribution of natural sediments is flat and uniform throughout the riverbed. Second, this study assumed that the microplastic abundance at each sampling site was representative of the microplastic occurrence in the adjacent riverbed. The microplastic inventory in the surface sediments (0–20 cm) of Dong River was estimated by the following equations:

Where Si is the number of microplastics stored (0–20 cm) in the riverbed in river section i (n). Mi is the average sediment density in river section i (kg/m3) (Supplementary Table 7). Li is the average length of the river channel in river section i (m). Wi is the average width of the river channel in river section i (m). Hi is the depth of the riverbed in river section i (m). Ci is the average abundance of microplastics in the riverbed sediment of river section i (n/kg).

Quality control

In the field, container necks and sediment samples were tightly wrapped in aluminum foil to reduce airborne contamination. Sampling equipment was cleaned several times with ultrapure water before each sample to minimize cross-contamination. In the laboratory, experimenters wore cotton lab coats and disposable nitrile gloves throughout. Experimental equipment was washed with ultrapure water and sealed for backup use. All solutions used in the experiment were prepared in a ready-to-use state and filtered before use. Samples were covered with aluminum foil during the digestion process and the solution was also covered with aluminum foil when not in use. In this study, three standard microplastic samples of polyethylene (0.94 g/cm3), polystyrene (1.05 g/cm3), and polyvinyl chloride (1.38 g/cm3) were selected for the recovery test of microplastics from sediments, and the recovery rates were 98.36%, 95.17%, and 93.48%, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Microsoft Office Excel 2011 (Microsoft, USA), SPSS 19.0 (IBM, USA), Cellsens Dimension (Version 3.22, Germany), and R (R Studio, USA) were used for statistical analysis. The Dongjiang River sampling sites and associated information were mapped using ArcGIS 10.7 (ESRI, USA). The Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn’s post-hoc test were used to test for differences in microplastic abundance among regions due to the non-normality of the data. Pearson’s correlation was used to test the correlation between microplastic abundance and other environmental factors. Pearson’s correlation was used to test the correlation between microplastic flux/inventory and flow rate.

Responses