One-step Cre-loxP organism creation by TAx9

Introduction

The Cre-loxP system is a potent tool that is used in an array of life science fields to address molecular and cellular mechanisms in heredity, development, physiology, disease, and more. Cre is a bacteriophage 38-kDa recombinase that targets a set of 34 bp DNA elements, named loxP, and depending on the orientation of the loxP sequence, researchers can use it to study deletions, inversions, or the translocation of a DNA site flanked by loxP elements (floxed site) in the genomes of organisms1,2. To tactically drive Cre activation in spatial-temporal experiments in eukaryotes, researchers have turned to inducible Cre, such as CreER1,2,3,4. In this system, Cre is fused with a modified human estrogen receptor (ER) protein, which is temporarily activated by the administration of a selective estrogen receptor agonist, tamoxifen (or its active metabolite, 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT)), allowing ER to translocate Cre linked to ER from the cytoplasm to the nucleus across the nuclear envelope in eukaryotes3. Here, CreER expression is also spatially controlled by a tissue-specific promoter3. On the other hand, ER has no role in bacteria, since they are prokaryotes that do not have a nuclear envelope.

It is common practice during the creation of a Cre-loxP organism to develop a tissue-specific Cre-driver strain and a loxP reporter strain. Both strains can then be bred to obtain a target line. However, in organisms that require a long time to achieve sexual maturation or a generational change, this poses a great challenge, not only to the cost of their production but also to their maintenance until experimentation. Ideally, plasmids containing both a Cre gene and a floxed site would facilitate the production of genetically modified organisms. However, most attempts to synthesize Cre-loxP single plasmids would fail since Cre-mediated recombination occurs in Escherichia coli bacterial cells, resulting in the loss of the floxed site from the plasmids5,6. This undesired Cre-mediated recombination in E. coli is known to occur not only with Cre and CreER but also with a eukaryotic promoter adjacent to the 5′ end of the Cre gene5,6. The possibility that Cre is weakly expressed in E. coli has been discussed, although the mechanism is still unclear5,6. In a typical E. coli culture for plasmid production, Cre-mediated recombination does not occur in all copies of plasmids. However, this phenomenon is serious from a practical standpoint because it not only reduces the productivity of Cre-loxP cells/organisms by transfection/transgenesis but also results in the loss of the Cre-loxP single plasmid due to the accumulation of recombined plasmids each time the E. coli culture is repeated. To overcome this technical hurdle, CREM, a modified version of Cre, was developed5. In this system, the DNA construct encoding Cre contains an altered 5′ region and an intron, which does not allow the expression of functional Cre in E. coli cells but allows proper Cre expression in mammalian cells, such as CHO-K1 and PC-3 cells5. However, since this system is dependent on the species and cell types for which post-transcriptional regulation of the intron is warranted, a more versatile technology is still needed.

To address this Cre-loxP single plasmid issue, in this study, we investigated artificial TA/AT repeat DNA elements inspired by a genomic region of the frog Xenopus laevis, and finally discovered TATATATATATATATATA, named TAx9, an element that offered protection against Cre-mediated recombination in E. coli cells when positioned next to the upstream side of the tissue-specific Cre-driver site. We eventually developed tamoxifen-inducible retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cell-labeled newts and skeletal muscle fiber (SMF) cell-labeled mice, demonstrating that the Cre-loxP plasmids synthesized with the TAx9 technology could allow the efficient creation of genetically modified individuals in a variety of animal species.

Results

TAx9 is an optimal solution for the synthesis of complete Cre-loxP single plasmids in E. coli cells

We found in our extended studies of newt body part regeneration that the 2627 bp genomic region (∆CarA) upstream of the cardiac actin promoter in X. laevis contained a TA/AT repeat-rich region (867 bp) that protected Cre-loxP single plasmids against Cre-mediated recombination in E. coli cells (see “Attaining the TA repeat sequences” in Supplementary Information; Supplementary Figs. 1–7). Our results suggest that the TA repeat sequences are similar to the E. coli LexA repressor binding motif (also referred to as the SOS box)7,8, and could be candidate protective elements. In this study, we focused on screening the optimal TA repeat elements for practical use.

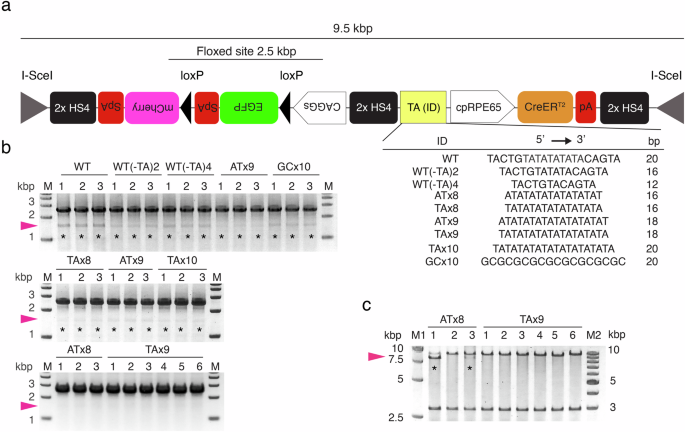

Here we define TA/AT as direct repeat sequences with only adenine and thymine residues, in an alternating pattern (i.e., TATATA or ATATAT). To investigate whether these TA repeat elements had any possible shielding effect against Cre-mediated recombination of the floxed site, we designed a plasmid pmCherry[EGFP]<CAGGs-TA(ID)-cpRPE65>CreERT2(I-SceI) (Fig. 1a). Here, the newt cpRPE65 promoter9 was introduced upstream of the CreERT2 gene (encoding a Cre fused with a T2 version of ER1). This plasmid allowed us to insert a variable TA repeat element into the TA(ID) region located next to the upstream end of the cpRPE65 promoter. We note that this plasmid was devoid of any elements of ΔCarA.

a The plasmid used to optimize the TA repeat element. Each of the DNA elements listed with their ID was inserted into the TA(ID) site to examine its shielding effect on Cre-mediated recombination in E. coli cells. Here, WT is the E. coli LexA binding motif, i.e., the SOS box. To detect deletion of the floxed site due to Cre-mediated recombination, PCR primers were set on the CAGGs promoter and the site adjacent to the mCherry 5′ region to amplify a 2.5 kbp (intact) or 1.5 kbp (recombined) region. 2× HS4: a double core of the HS4 insulator9. Each of the EGFP, mCherry, and CreERT2 gene cassettes was attached with an eukaryotic terminal polyadenylation signal sequence on its 3′ end. pA: rabbit β-globin polyadenylation signal; SpA: SV40 polyadenylation signal. b Evaluation of recombination in the primary E. coli cells following transformation. Colony PCR was carried out using single colonies that were randomly selected from an LB plate cultured at 30 °C for 18 h. Lane numbers indicate colony ID. Cre-mediated recombination occurred in all colonies except for those of ATx8 and TAx9 (asterisks). Pink arrowheads: 1.5 kbp (recombined). M: size marker. c Integrity of the plasmids after the culture of E. coli cells in LB medium. Here, the E. coli cells containing the plasmids with ATx8 (clone ID: 1–3 in b) and those with TAx9 (clone ID: 1–6 in b) were further cultured in three and six tubes, respectively, for 18 h at 30 °C. The plasmids were purified from the cultures and digested with the I-SceI. The sizes of the I-SceI-flanked region and the plasmid backbone were 9.5 kbp and 2.9 kbp, respectively. Lane numbers indicate tube ID. Cre-mediated recombination (8.5 kbp; arrowheads) was detected with ATx8 (asterisks) but was never detected with TAx9. Note that the band of recombined plasmids in lane #3 of ATx8 was faint compared to that in lane #1. M1 and M2: size markers.

We tested TA repeat elements of different lengths and orientations (ATx8, TAx8, ATx9, TAx9, TAx10) as well as the LexA repressor binding motif (wild type: WT)7,8, WT variants (WT(-TA)2, WT(-TA)4), and GC repeats (Fig. 1a). To our surprise, for all these elements, including WT, Cre-mediated recombination was detected in all primary E. coli transformants grown as colonies on agarose plates (n = 3 each), except for ATx8 (n = 3) and TAx9 (n = 6) (Fig. 1b). In a comparison between ATx8 and TAx9, the latter perfectly blocked Cre-mediated recombination or preserved the plasmid’s integrity (n = 6), even after culturing E. coli cells in medium to obtain a sufficient number of plasmids for practical use (Fig. 1c). Thus, we conclude that TAx9 is the minimal element sufficient for Cre-loxP single plasmid production.

Since TAx9 suppressed recombination better than WT (i.e., LexA repressor binding motif), we examined in vitro whether the binding affinity of LexA for TAx9 was higher than that for WT. Interestingly, although LexA is bound to TAx9, the binding affinity of LexA for TAx9 was considerably lower than that for WT (Fig. 2).

A gel shift assay was performed to examine the binding affinity of LexA proteins to the TAx9 element in comparison to the LexA binding motif (WT). a In the presence of WT oligonucleotides (duplex DNA) at a concentration of 10 pmol, synthetic LexA proteins formed complexes with them at 5 pmol and above. On the other hand, in the presence of 10 pmol of TAx9 oligonucleotides (lower panel), synthetic LexA proteins formed complexes with them at 20 pmol. b Increasing the concentration of TAx9 oligonucleotides to 20 pmol resulted in a more distinct band of complexes at 20 pmol of the synthetic LexA proteins. Note that in both conditions (a, b), free TAx9 oligonucleotides decreased as the concentration of synthetic LexA protein increased; the data using GCx10 oligonucleotides is shown as a negative control (lower panel in b). Taken together, these results indicate that under the current experimental conditions, LexA proteins bind to TAx9 oligonucleotides, although the binding affinity of LexA proteins to TAx9 oligonucleotides is much lower than that to WT oligonucleotides. Black arrowheads indicate the location of complexes.

TAx9 technology enables the creation of Cre-loxP animals in the F0 generation

Next, we demonstrate that our TAx9 technology facilitates the creation of Cre-loxP organisms. In this study, we attempted to create inducible Cre-loxP RPE cell-labeled newts and SMF cell-labeled mice in the F0 generation.

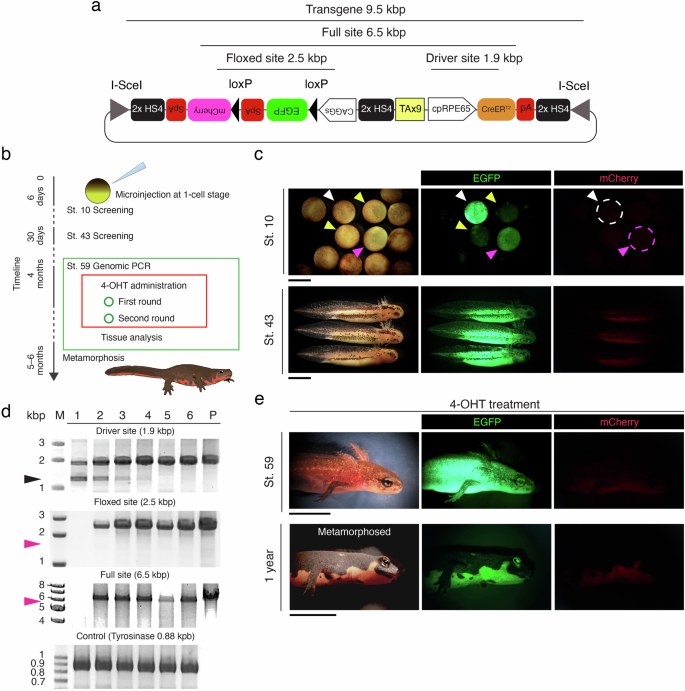

Newts

We applied the above-analyzed plasmid pmCherry[EGFP]<CAGGs-TAx9-cpRPE65>CreERT2(I-SceI) (Fig. 3a) to create transgenic C. pyrrhogaster newts with the I-SceI technique10 (Fig. 3b). We obtained a total of 40 individuals that exhibited EGFP+/mCherry– by screening their fluorescence at an early blastula stage (St. 10) and at the larval stage (St. 43) (Fig. 3c), as well as by genomic PCR at the swimming larval stage just before metamorphosis (St. 59) (Fig. 3d). At St. 59, swimming larvae were treated with either 4-OHT or a solvent (DMSO) alone (Fig. 3e). Some of the larvae were subjected to an immunohistochemical analysis (Fig. 4). In the eyeballs, mCherry immunoreactivity was detected along the RPE layer, but not in other ocular tissues, as early as 48 h after 4-OHT administration (Fig. 4a, b). On the other hand, in the control condition with DMSO alone, mCherry immunoreactivity was not detected (Fig. 4a). These results were as expected, with 4-OHT inducing Cre-mediated recombination specifically in RPE cells. The other 4-OHT-treated F0 individuals (n = 10) allowed development beyond metamorphosis. All of the larvae grew normally, exceeding one year of age (Fig. 3e).

a Schematic diagram showing the plasmid pmCherry[EGFP]<CAGGs-TAx9-cpRPE65>CreERT2(I-SceI). b Outline of the transgenic protocols. 4-OHT: 4-OH tamoxifen. c Screening by fluorescence at an early blastula stage (St. 10) and at the larval stage (St. 43). Individuals never exhibited mCherry fluorescence, and instead emitted EGFP fluorescence. The differential intensity of EGFP fluorescence is thought to be caused by the number of transgene cassettes inserted in the genome, or their location. In St. 10, white, pink, and yellow arrows indicate strong, average, and weak EGFP fluorescence, respectively. Embryos exhibiting strong (white broken circle) or average (pink broken circle) EGFP fluorescence were screened. d Screening by genomic PCR at the swimming larval stage (St. 59). Lane numbers indicate the ID of the individual. P: plasmid DNA (control). M: size marker. The full site (6.5 kbp), driver site (1.9 kbp), and floxed site (2.5 kbp) were examined (see a). A 0.88 kbp site of the tyrosinase gene was also examined as the positive control. Black arrowhead: nonspecific band. Pink arrowhead: 1.5 kbp or 5.5 kbp, the size of the band that would be detected if Cre-mediated recombination had occurred. In this group, all larvae were screened as positive, except for the ID#1 individual, whose full and floxed sites were not amplified by PCR. Undesired Cre-mediated recombination was never recognized. e Fluorescence after 4-OHT administration. Individuals at St. 59, just before metamorphosis, were treated twice with 4 µM 4-OHT (see b). mCherry fluorescence was never detected, at least not on the surface of the body, at 48 h post-treatment (upper panels) or even beyond metamorphosis (lower panels). All of the metamorphosed individuals (n = 10) grew normally, beyond 1 year. Scale bars: c 2 mm for St. 10, 2 mm for St. 43; e 0.5 cm for St. 59, 1 cm for 1 year.

a Representative images showing 4-OHT-dependent induction of mCherry expression in RPE cells. Larvae at St. 59 were treated with either 4-OHT (+4-OHT) or the solvent (DMSO alone) (−4-OHT) at 48 h before obtaining eyeballs (three larvae for each group). Here, to visualize immunoreactivity in the RPE layer, the ABC-DAB method was applied and melanin pigments were bleached. Arrowheads point to mCherry-immunoreactive cells along the RPE layer. b Representative images showing the double labeling of RPE65 and mCherry in RPE cells by antibodies (three larvae). DAPI: nuclear stain. The lower panels are enlarged views of the area enclosed by the dashed rectangles in the upper panels. In the lower panels, dashed lines highlight the RPE layer. White arrowheads point to the RPE cells with both RPE65- and mCherry-immunoreactivity. GCL: ganglion cell layer; INL: inner nuclear layer; ONL: outer nuclear layer. Scale bars: a, 100 μm; b, 200 µm for upper panels, 100 µm for lower panels.

Mice

We constructed a plasmid pmCherry[EGFP]<CAGGs-TAx9-hACTA1>CreERT2(ROSA26 Arms) in E. coli cells (Fig. 5a and see Supplementary Fig. 8). Here, the human ACTA1 promoter (hACTA1) was used to specifically drive expression of the CreERT2 gene in mouse mature SMF cells4. ROSA26 left and right homologous arms11,12 were placed at both ends of the transgene cassette to transfer it to the ROSA26 safe harbor site in the mouse genome. Using this plasmid vector, we carried out CRISPR-Cas9 knock-in (KI)13 with 283 mouse embryos and obtained 79 neonates (29%) from which 76 individuals (96%) survived beyond the post-weaning period. We examined these individuals by genomic PCR, and finally screened nine individuals (11.8%) that carried the intact transgene cassette in the ROSA26 locus (Fig. 5b–d). In this screening process, PCR bands were never found at either 4.2 kbp for the 5′ arm crossing site (Fig. 5c), 1.5 kbp for the floxed site (Fig. 5d), or 6.5 kbp for the full site (Fig. 5d), indicating that undesired Cre-mediated recombination hardly occurs until this stage.

a Schematic diagram showing the plasmid pmCherry[EGFP]<CAGGs-TAx9-hACTA1>CreERT2(ROSA26 Arms) designed to create SMF cell-labeled mice by the CRISPR-Cas9 knock-in (KI) protocol targeting the ROSA26 locus11,12 (also see Supplementary Fig. 8). The sites amplified by genomic PCR are noted. b–d Screening of KI individuals by genomic PCR. Here, a total of 76 one-month-old individuals who survived beyond the weaning period were examined. Lane numbers indicate the ID of the individual. P: plasmid DNA (control). M: size marker. The first PCR for the 3′ arm crossing site (3.3 kbp) (b) followed by the second PCR for the 5′ arm crossing site (5.2 kbp) (c) screened nine individuals as positive candidates (white asterisks). Individuals with ID#s 13, 22, 30, 37, 43, 44, 59, and 60 are considered to be individuals with DNA fragments containing the 3′ arm crossing site but not the 5′ arm crossing site, that were inserted randomly into the genome. KI of the single Cre-loxP construct in all these candidates was confirmed by the last PCR for the driver site (2.9 kbp), the floxed site (2.5 kbp), and the full site (7.5 kbp) (d). e Fluorescence of the tail tip of KI-positive (#7, #8, #9) and KI-negative (#6) individuals. All of the KI-positive individuals showed EGFP fluorescence but not mCherry fluorescence, indicating that Cre-mediated recombination had not occurred. Pink arrowhead: 4.2 kbp (c), 1.5 kbp (d), or 6.5 kbp (d), indicating the size of the band that would be detected if Cre-mediated recombination had occurred. Scale bar: 5 mm.

Thus, we successfully obtained Cre-loxP mice in the F0 generation. However, more individuals were needed to investigate the induction of SMF cell-specific recombination by tamoxifen. Therefore, we crossed F0 individuals with wild-type mice to obtain F1 individuals. Then, we obtained heterozygous F1 individuals using the same methods that were used for the F0 generation, i.e., screening by fluorescence and genomic PCR. Using these F1 individuals, we tested the effect of tamoxifen administration on SMF cell-specific recombination (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 9). Genomic PCR analysis revealed that recombination of the floxed site occurred in a tamoxifen dose-dependent manner, with the probability of recombination increasing as the number of doses increased (Fig. 6a). Microscopic analysis of limb tissue sections revealed that mCherry expression was specifically induced in muscle fibers after the administration of tamoxifen (TAM+, n = 3; Fig. 6b, c), but not after the administration of the solvent corn oil alone (TAM–, n = 3; Fig. 6d, e) (also see Supplementary Fig. 9).

a Genomic PCR for the floxed site in F1 heterozygous KI mice (intact, 2.5 kbp; recombined, 1.5 kbp). These mice were injected with three doses (3D) or six doses (6D) of tamoxifen or the solvent corn oil alone (TAM−) two weeks before limb sample collection (n = 3 each). Lane numbers indicate the ID of the individual. WT: genomic DNA of a wild-type C57BL/6J mouse. P: plasmid DNA (control). M: size marker. Pink arrowheads: 1.5 kbp (recombined). b−e Representative images showing tamoxifen-dependent induction of mCherry expression in SMF cells (n = 3 for each). F1 heterozygous KI mice were injected with either six doses of tamoxifen (TAM+) or the solvent corn oil alone (TAM−). The limb samples were cross-sectioned in the middle of the zeugopod (20 µm thick). mCherry fluorescence was detected in the TAM+ mice (b, c) but not in the TAM− mice (d, e). Note that EGFP fluorescence in the TAM+ mice was weaker than in the TAM− mice, suggesting recombination of the floxed site. The optical sections (1.3–2.0 µm thick) of the boxed areas of the merged images in (b) and (d), acquired by laser confocal microscopy, are shown in (c) and (e), respectively. Scale bars: b and d 1 mm for upper panels, 200 µm for lower panel; c and e 100 µm.

Discussion

The synthesis of Cre-loxP single plasmids using E. coli bacterial cells has been limited because the Cre gene on the plasmid is spontaneously expressed in E. coli cells, regardless of the presence of adjacent eukaryotic promoters, and recombination of the floxed site occurs even when using inducible Cre5,6. Therefore, researchers have developed thus far a tissue-specific Cre-driver strain and a loxP reporter strain separately and bred them to obtain a target Cre-loxP organism. If Cre-loxP single plasmids can be synthesized, the efficiency of the development of Cre-loxP organisms can be improved in terms of funds, time, space, and other limiting factors, particularly when studying gene function in animals with long reproductive cycles or small numbers of offspring.

We previously found that a certain genomic region of X. laevis (ΔCarA), when present adjacent to the upstream portion of the Cre-driver cassette, suppressed Cre expression in E. coli cells, allowing the synthesis of a Cre-loxP single plasmid. ΔCarA contained a region rich in TA/AT repeat sites, similar to the LexA repressor binding motif (or the SOS box)7,8 of E. coli. In this study, based on that knowledge, we searched for practical TA/AT repeat elements and demonstrated that TAx9 is an optimal solution. However, it is important to note here that the 115 bp region at the 3′ end of ΔCarA, which alone showed a protective effect against Cre-mediated recombination, did not contain TAx9 but instead contained TAx8/ATx8 (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 7). Since it is unlikely that both TAx8 and ATx8 have a complete shielding effect (Fig. 1b, c), it is possible that adjacent DNA structures of TAx8/ATx8 in ΔCarA have some complementary effect.

Regarding TAx9, since a synthetic LexA repressor protein can bind to TAx9 duplex DNA (Fig. 2), it is thought that Cre expression in E. coli cells is suppressed by LexA repressor binding to TAx9, which inhibits the activity of the adjacent promoter. However, importantly, the binding affinity of LexA repressor for TAx9 was considerably lower than for the LexA repressor binding motif (Fig. 2a), although the inhibitory effect of TAx9 on Cre-mediated recombination was higher and more complete than that of the LexA repressor binding motif (Fig. 1). In the future, it will be necessary to investigate the possibility that the interaction between LexA and TAx9 (or between LexA and the LexA binding motif) is altered in E. coli cells, as opposed to in vitro. An alternative explanation may lie in the structural nature of the AT/TA sequences. Studies have found that the dodecamer d(ATATATATATAT) sequences form very stable coiled coils14,15. This coiling nature of AT/TA, when positioned upstream of a promoter, may act as a coiled barrier that prevents the transcription of Cre16. However, this mechanism cannot explain why other AT/TA elements, such as ATx9 or TAx10, had no barrier effects (Fig. 1b).

Using the TAx9 technology, we synthetized single Cre-loxP plasmids in E. coli cells, and succeeded in creating inducible Cre-loxP transgenic newts (RPE cell-labeled) and CRISPR-Cas9 KI mice (SMF cell-labeled) in the F0 generation. In both animals, TAx9 did not affect normal development and growth. In addition, Cre-mediated recombination in the target cell type was induced by treatment with 4-OHT or tamoxifen, indicating that there is no spontaneous recombination at the floxed site and, unlike in E. coli cells, TAx9 does not seriously affect the activity of the Cre-driver cassette. For newts, F0 individuals could be used directly in retinal regeneration studies by carefully evaluating the specificity of the expression regions. For mice, however, although F0 individuals were obtained in this study, recombination was evaluated in F1 individuals due to a limited number of individuals. In KI mice, researchers generally perform multiple backcrosses with wild-type mice to eliminate the possibility that transgene constructs have been randomly inserted into non-target regions of the genome, thereby establishing a strain. Under these circumstances, our technology will contribute to the ability to efficiently establish mouse lineages (Supplementary Fig. 10). If the Cre and loxP cassettes are separate, mating could cause each cassette to segregate into different offspring, but if a single plasmid is used to create KI mice, the Cre-loxP cassette can be maintained at a single locus, avoiding this problem. Moreover, the fact that the Cre-loxP cassette is at a single locus facilitates strain maintenance with a single genotyping protocol.

In principle, TAx9 technology can be applied not only to standard and inducible Cre-loxP systems but also to a variety of conditional gene modification tools such as Flp-frt17,18 and Dre-rox18,19. These technologies can be combined with RNA interference20 or CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing tools21, thereby enabling not only forced gene expression but also gene knockdown/knockout in spatially and temporally restricted ways. Moreover, TAx9 technology is versatile because it is likely independent of animal species and cell types. Of course, more research is needed to demonstrate that TAx9 does not have any effect on any type of promoter or on the expression of any recombinase gene in any animal (or any organism) or cell type. Through these validations, TAx9 technology will contribute to various fields of life science in the future.

Methods

All experiments reported herein were performed at the University of Tsukuba, in accordance with its guidelines and regulations. All protocols with animals were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Tsukuba (approval numbers: for newts, 170110 and 220125; for mice, 23–310 and 24–167). All genetic modification experiments were approved by the Genetic Modification Safety Committee of the University of Tsukuba (approval numbers: 170110, 220124, and 220125). Moreover, all methods were reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines 2.022.

Animals

We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use.

Adult C. pyrrhogaster newts (total body length: males, ∼9 cm; females, 11–12 cm) of the Toride-Imori line23 were used to obtain fertilized eggs for transgenesis. They were originally captured by a provider (Mr. Kazuo Ohuchi, Misato, Saitama, 341-0037 Japan; http://kaeru-kerokero.la.coocan.jp/index.html) within a ∼25 km diameter around the Miyayama area (35.130013, 140.013842) in Kamogawa city, Chiba prefecture, Japan. No specific permissions were required for the location of capture. Newts were reared for longer than one year in the laboratory (University of Tsukuba) by keeping them in plastic containers in which a shallow layer of water (∼3 cm deep) and a resting island were placed, at 18°C and in natural light, as was previously described24. In this study, 30 females and 10 males were kept in separate containers for 60 days until the transgenic experiments began. Both of them were fed frozen mosquito larvae (Akamushi; Kyorin Co., Ltd., Hyogo, Japan) three times a week. Containers were kept clean. To obtain fertilized eggs at the 1-cell stage (F0), adult newts were maintained according to a previously established protocol10. Using fertilized eggs (n = 84), transgenesis was carried out (see below), and embryos and larvae were staged according to established criteria24. A total of 10 transgenic individuals were finally screened and their recombination was examined without distinguishing between sexes (see the “Induction of Cre-mediated recombination” section).

Adult C57BL/6J mice (Strain #: 000664; RRID: IMSR_JAX:000664) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory Japan Inc. (Kanagawa, Japan)11 and kept in the Laboratory Animal Resource Center in the Transborder Medical Research Center. They were housed with a 14-h light: 10-h dark cycle. Air quality was maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions (23.5 °C ± 2.5 °C and 52.5% ± 12.5% relative humidity)11. They were fed a commercial diet (MF diet; Oriental Yeast Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and could drink filtered water, both of which were freely accessible. For CRISPR-Cas9 KI, a total of 283 embryos were used, a total of 76 individuals (males: 39; females: 37) survived beyond the post-weaning period, and a total of nine individuals (males: two; females: seven) were finally screened as F0. For experiments with F1 to F4, a total of 117 individuals (males: 57; females: 60) were used. In the recombination experiments in Fig. 6, three males and three females were used for the test (for 3D, one male, two females; for 6D, two males, one female) while one male and two females were used for the control (TAM−) (see the “Induction of Cre-mediated recombination” section).

Only skilled researchers handled both the newts and mice. There were no unexpected adverse events.

Plasmid construction

All plasmids used herein were constructed and synthesized by standard molecular cloning techniques. In brief, to screen for optimal DNA elements to protect Cre-loxP single plasmids from Cre-mediated recombination in E. coli cells, a region containing CarA>CreERT2 was removed from the plasmid pmCherry[EGFP]<CAGGs-CarA>CreERT2 (I-SceI)25 with the restriction enzymes, BspEI and Ajul, and then a fragment BspEI-PpuMI-I-PpoI>CreERT2 was inserted back in, creating a new intermediate plasmid pmCherry[EGFP]<CAGGs-BspEI-PpuMI-I-PpoI>CreERT2 (I-SceI). The I-PpoI restriction enzyme recognition site was used to insert a promoter to drive the expression of CreERT2. In this study, a 1.1 kbp fragment containing the cpRPE65 promoter and its 5′ UTR region9 were inserted. The BspEI-PpuMI site was referred to as TA(ID), which was used to insert a candidate protective DNA element indicated in Fig. 1a.

To create inducible Cre-loxP RPE cell-labeled newts, the plasmid pmCherry[EGFP]<CAGGs-TAx9-cpRPE65>CreERT2 (I-SceI) was constructed (Fig. 3a). Here, TAx9 was inserted at the TA(ID) site. The transgene cassette was flanked by the I-SceI meganuclease recognition sites. The chicken β-globin HS4 2× core insulators (a gift from Dr. Gary Felsenfeld at the National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) were placed at both ends of the Cre-driver cassette and the floxed reporter cassette to reduce the positional genomic effects and cis interactions within the transgene. Each of the EGFP, mCherry, and CreERT2 gene cassettes was followed by an eukaryotic terminal polyadenylation signal sequence (for details, see Fig. 1).

To create inducible Cre-loxP SMF cell-labeled mice, the plasmid pmCherry[EGFP]<CAGGs-TAx9-hACTA1>CreERT2(ROSA26 Arms) was constructed (Fig. 5a and see Supplementary Fig. 8). At first, the human ACTA1 skeletal muscle promoter4 fragment (−1919 to +156 in exon 1) was inserted at the I-PpoI site in the plasmid pmCherry[EGFP]<CAGGs-TAx9-I-PpoI>CreERT2 (I-SceI), creating the plasmid pmCherry[EGFP]<CAGGs-TAx9-hACTA1>CreERT2 (I-SceI). Next, the entire transgene cassette was released by I-SceI digestion and inserted into a ROSA26 targeting vector11,12, so that the transgene cassette had the homologous arms targeting the ROSA26 locus adjacent to both ends of the cassette (1.1 kbp at the 5′ side and 2.8 kbp at the 3′ side)11,12. This cassette also contained three sets of the chicken β-globin HS4 2× core insulators.

For all plasmids, E. coli cells of the NEB stable strain (C3040I; New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) were transformed and cultured on LB plates at 30°C for 18 h. Colonies on the plates were individually examined by PCR for Cre-mediated recombination in plasmids, and cultured in LB medium for an additional 18 h at 30°C. The plasmids synthesized in the E. coli cell culture were purified using the GeneJET Plasmid Miniprep Kit (K0502; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Tokyo, Japan) or the PureLink HiPure Plasmid Filter Midiprep Kit (K210014, Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Exceptionally, as explained in the “Attaining the TA repeat sequences” section of the Supplementary Information, insert DNA was obtained by PCR and ligated into plasmids using the In-Fusion method (Z9649N; In-Fusion® HD Cloning Kit, Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. E. coli cells used for transformation and culture were the Stbl3 strain (One Shot™ Stbl3™ Chemically Competent E. coli; C737303, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). The culture conditions were the same as those for the NEB stable strain mentioned above. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 7, inserts containing TA/AT-rich sites were amplified using Tks Gflex DNA Polymerase (R060A; Takara Bio Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In the experiments to evaluate Cre gene expression in E. coli cells (Supplementary Fig. 5), total RNA was purified using the SV Total RNA Isolation System (Z3100; Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and amplified using the One Step RNA PCR Kit (AMV) (RR024A; Takara Bio Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Gene modification

For transgenic newts, an I-SceI protocol we established for C. pyrrhogaster10 was applied. Briefly, fertilized eggs (one-cell stage embryos) were individually micro-injected with 100 pg of plasmid DNA and 2.0 × 10-3 U of I-SceI, which were dissolved in 1× I-SceI buffer. For CRISPR-Cas9 KI mice, a protocol we established11,12,13 was applied with a guide RNA targeting 5′-CCAGTCTTTCTAGAAGATGGGCG-3′ in the ROSA26 locus (chr6: qE3). Preparation of crRNA, tracrRNA, Cas9, and donor DNA, micro-injection into mouse zygotes, and embryo transfer into pseudopregnant mice were all performed using the same methods as in our previous papers11,12,13.

Anesthesia

Larval newts (St. 59) were anesthetized with FA100 (4-allyl-2-methoxyphenol; DS Pharma Animal Health, Osaka, Japan) dissolved to 0.05% (v/v) in filtered tap water at 18 °C; for image capture, 30 min; for tail tip sampling, 30 min; for head collection or euthanasia for culling, deep anesthesia as long as 60 min (the larvae remain in an upside down position and do not respond to cutaneous pinching with forceps) followed by decapitation. Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of a mixture of ketamine and xylazine; for tail tip sampling, 80 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine (10 min); for forelimb collection or euthanasia for culling, an overdose of the anesthetics (triple the dosage; 15–20 min) followed by cervical dislocation. In both conditions, we confirmed that the mice were unresponsive to pinching of their legs and tails.

Genomic PCR

Genomic DNA was obtained from the tail tips of larval newts (St. 59) and mice (1 month old) with a Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (A1120; Promega). For mice, limb muscles were also used (see below). The genomic DNA solution was aliquoted to 10 ng/µL and kept at 4 °C. PCR was carried out using Tks Gflex DNA Polymerase (R060A; Takara Bio Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primer sets are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Induction of Cre-mediated recombination

For larval newts (St. 59), the method we established26 was applied. In brief, larvae were incubated in filtered tap water containing 4 μM 4-OHT ((Z)-4-hydroxytamoxifen, H7904-5MG; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and 0.8% (v/v) dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO; 045-07216; FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) for 24 h at 22 °C in the dark (first round). They were immediately transferred into fresh 4-OHT-containing water and incubated for an additional 24 h in the same conditions (second round). For control, larvae were incubated in filtered tap water containing DMSO alone.

For mice (1 month old), a standard peritoneal injection protocol was applied. In brief, tamoxifen (T5648-1G, Sigma-Aldrich; Merck) was dissolved in corn oil (032-17016, Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) at a concentration of 20 mg/mL for 1 h at 65 °C in the dark and vortexed, and the liquid was divided into 1 mL aliquots and stored at 4 °C (it was used within 1 week). Just before injections, aliquots were prewarmed for 10 min at 65 °C, cooled to room temperature, and then injected with a 27-gauge needle (NN-2719S; Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) to achieve 150 mg/kg body weight. Injections were given once a day for three consecutive days, followed by a four-day interval, and then again for three consecutive days (six doses in total). Following the last injection, mice were allowed to rest for 2 weeks. For the control, corn oil alone was injected.

Tissue preparation

In this study, a fixative, 3% glyoxal27,28 (078-00905, FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) and 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA; Catalog 26126-25; Nacalai Tesque, Inc., Kyoto, Japan) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.0, adjusted with acetic acid) was prepared, stored in an amber-colored glass bottle at 4°C, and used within 1 month.

Heads of larval newts (St. 59) were collected in PBS on ice, and immediately transferred into the fixative and incubated at 4 °C for 8 h. The samples were washed several times for 3 h each in PBS at 4 °C, decalcified in 10% ethylenediamine-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EDTA) in PBS (pH 7.0, adjusted with NaOH) for 48 h at 4°C, rinsed in PBS, and then transferred to 30% sucrose in PBS at 4 °C.

Forelimbs of mice (1 month old) were collected in PBS on ice following cervical dislocation, their skin was removed, and they were trimmed to obtain a portion from the wrist to the distal end of the humerus. Limb muscles for genomic DNA were sampled at this time. The deskinned forelimb samples were immediately fixed at 4 °C for 18 h, washed several times for 3 h each in PBS at 4 °C, and incubated in a decalcifying solution (10% EDTA in PBS (pH 7.0, adjusted with NaOH)) for 72 h at 4 °C, rinsed in PBS, and then transferred to 30% sucrose in PBS at 4 °C.

Following the equilibration process in sucrose solution, newt head and mouse forelimb samples were embedded into an O.C.T compound (45833; Sakura Finetech, Tokyo, Japan) and sectioned to 20 µm thickness using a cryotome (CM1860 UV, Leica Biosystems, Tokyo, Japan). Frozen sections were air dried in the dark for 24 h before proceeding to the direct observation of their fluorescence or immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry

Primary antibodies were mouse monoclonal anti-RPE65 antibody (1:500; MAB5428; EMD Millipore, Burlington, CA, USA), and rabbit polyclonal anti-RFP antibody (for mCherry; 1:500; 600-401-379; Rockland Immunochemicals, Pottstown, PA, USA). Secondary antibodies were Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) antibody (1:500; A11001; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.); rhodamine (TRITC)-conjugated affiniPure goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) antibody (1:500; Code: 111-025-003; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA), and biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:250; BA-1000; Vector Laboratories, Inc., Newark, CA, USA). Immunohistochemistry was performed as in a previous paper26, with some modifications. In brief, for immunofluorescence labeling, tissue sections were washed (PBS, 15 min; 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS, 15 min; and PBS, 15 min), incubated with blocking solution (2% normal goat serum (S-1000; Vector Laboratories), 50% animal free blocker (SP-5035-100, Vector Laboratories) and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 2 h, and then incubated with primary antibody diluted in blocking solution overnight at 4 °C. The sections were washed and then incubated with a secondary antibody diluted in a blocking solution for 4 h. After washing, the sections were counterstained with 4,6-diaminodino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1: 50,000; D1306; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.).

For immunoperoxidase labeling, tissue sections were washed, and incubated in a blocking solution mixed with Avidin D (1:50; Avidin/Biotin Blocking kit; SP-2001; Vector Laboratories Inc.) for 2 h, washed with PBS, then incubated in primary antibody diluted with blocking solution containing biotin (1:50; Avidin/Biotin Blocking kit) overnight at 4 °C. The sections were washed, incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody in blocking solution for 4 h, washed, incubated with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS containing avidin and biotin complex (1:50 each; Vectastain ABC Elite kit; PK-6100; Vector Laboratories Inc.) for 2 h, washed, then treated with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution (DAB substrate kit; SK-4100; Vector Laboratories Inc.). Following labeling, the sections were washed and counterstained with DAPI. For ocular sections of newt larvae, melanin pigments of the RPE layer were bleached with PBS containing 3% H2O2 and 1.5% sodium azide26.

Gel shift assay

The WT (LexA binding element), TAx9, and GCx10 (negative control) containing single-strand oligonucleotides were self-annealed using conventional molecular cloning techniques to form duplex DNAs. In brief, the forward and reverse single-strand oligos of equal concentration (Supplementary Table 2) were heated at 95 °C for 3 min, incubated at 85 °C for 1 min, and then subjected to the same treatment until a total of 60 steps, where the annealing temperature was lowered by 1 °C in each successive step. Complexes of the E. coli LexA recombinant protein (01-005; Cosmo Bio, Tokyo, Japan) with each duplex DNA were formed according to established optimized methods for the WT (i.e., the SOS box) duplex DNA7. The protein-DNA reaction products (10 μL) were electrophoresed on 3.2% agarose gels (Agarose 21; 313-03242; Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan) in 0.5x TBE (45 mM Tris-borate, 1 mM EDTA) buffer at 4 °C and 100 V for 70 min.

Statistics and reproducibility

For E. coli, mice, and newts, at least three samples (experimental unit: a bacterial colony or a single animal) were analyzed per examination. No statistical comparisons of means or variances among multiple groups were made in this study. No data were excluded from the analyses. A minimum of three biological replicates were used in each evaluation since we employed only already established techniques in this study. In the case of recombination experiments, CreERT2–loxP animals were randomly separated into two groups before tamoxifen (test group) or DMSO/corn oil (control group) administration. There was no need for blind grouping because CreERT2–loxP animals with similar EGFP fluorescence were used. Data were evaluated independently by several authors. Potential confounders were not considered.

Microscopy and image analysis

Fluorescence of living newts and tail tips of mice were observed under a fluorescence dissecting microscope (M165 FC; Leica Microsystems, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with filter sets for EGFP (Leica GFP-Plant; exciter: 470/40 nm; emitter: 525/50 nm) and mCherry (exciter: XF1044, 575DF25; emitter: XF3402, 645OM75; Opto Science, Tokyo, Japan), which were designed to minimize bleed-through artifacts. Images were captured with a digital camera system (EOS Kiss x7i; Canon, Tokyo, Japan) attached to the microscope. Tissue sections were observed on a fluorescence microscope (BX50; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with the same filter sets for EGFP and mCherry as well as that for DAPI. Images were captured with a charge-coupled device camera system (DP73; cellSens Standard 1.6; Olympus) attached to the BX50 microscope. For mouse limb sections, a laser confocal microscope system (LSM700; ZEN 2009, ver. 6.0.0.303; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) with filter sets for EGFP (Diode 488 Laser; emitter: BP 515–565 nm) and mCherry (Diode 555 Laser; emitter: BP 575–640 nm) was used. Images were analyzed with the software of the image acquisition systems and the functions of Adobe Photoshop 25.11.0 (Adobe, San Jose, CA, USA). The brightness, contrast, and sharpness of images were adjusted according to the journal’s guidelines using Photoshop 25.11.0. All gel electrophoresis data employed in this study are images of a single uncut gel containing size markers (for raw data, see Supplementary Fig. 11). Some images were inverted (Figs. 1–3 and Supplementary Fig. 5). Panels and Figures were prepared using Illustrator 27.4.1 graphics software (Adobe).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses