Open problems in synthetic multicellularity

Introduction

Life forms in our biosphere fall into two categories: unicellular (UC) and multicellular (MC). UC organisms act independently, dealing with their environments autonomously, while MC organisms consist of various cell types with division of labor and cooperation1,2. UC complexity is energetically favourable, involving simple replication and minimal life cycles. MC systems exhibit complex traits like developmental programs, self-maintenance, and spatial patterns3.

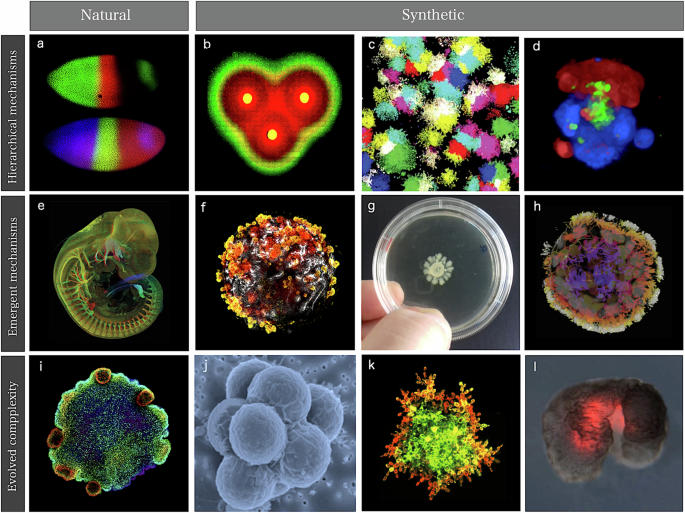

Experimental and comparative methods have traditionally helped the study of MC, while theoretical models and the revolutionary tools provided by molecular phylogenetics4,5,6. These studies have revealed unexpected insights concerning the tempo and mode of MC change and the role played by dynamical patterning modules7,8. However, thinking at the organism level beyond structural patterns, MC also includes other phenomena, such as movement or cognition, both relevant to our understanding of MC evolution. This paper considers the potential insights provided by synthetic alternatives based on diverse approaches to build cellular assemblies, from microbial consortia on a Petri Dish or cell clusters to organoids and living bots. Some examples are displayed in Fig. 1, with three examples from biology (first column) and several synthetic MC case studies with different levels of complexity. Here complexity is not defined in rigorous terms and several quantitative measures have been defined9, and specific choices are usually tied to the nature of the system under consideration.

These case studies include three natural examples (left column) of patterns and processes associated with hierarchical and emergent mechanisms and evolutionary dynamics. A classic example of a top-down mechanism in morphogenesis is the formation of gradients and stripes in Drosophila (a Data from the FlyEx database). These processes can be approached by (b) a synthetic band-pass filter using engineered E. coli138 (image courtesy of Ron Weiss), (c) the generation of multiple coexisting cell fates73 (image courtesy of Michael Elowitz) and (d) programmable symmetry breaking-induced structure formation (from ref. 78, image courtesy of Wendell Lim). Morphogenetic processes are spatially organized through multiscale feedback loops shaping embryos (e; image courtesy of James Sharpe). Synthetic counterparts of the underlying emergent phenomena include (f) kidney organoid development, (g) Turing-like branching morphogenesis of bacteria (g, h) the development of Anthrobots. The simplest, aneural metazoans are exemplified by Placozoans (image courtesy of Sebastian R. Najle, CRG) (i), while evolved cell assemblies emerge under synthetic selection mechanisms, including cell-cell adhesion to escape from predators (j; adapted from ref. 12. with permission), yeast MC aggregates (k; adapted from ref. 156, with permission) and Xenobots (l). The latter were obtained through a combination of in silico evolutionary algorithms and bioengineering.

The first two rows are related to hierarchical and emergent mechanisms of pattern generation10. These correspond to top-down (predictable) versus bottom-up (emergent) mechanisms, respectively, and both are relevant to our understanding (and engineering) of MC systems. Programmable MC synthetic systems shown in Fig. 1(b–d) include gradient-forming microbial consortia and multistable cell fates. On the other hand, many crucial developmental processes shaping embryos (Fig. 1e) include emergent phenomena captured by some synthetic MC systems, including organoids, branching bacterial populations and Anthrobots (Fig. 1f-h). Finally, the third row showcases the use of evolutionary strategies in the design of MC assemblies. The challenge here is to generate simple synthetic organisms, such as Placozoans (Fig. 1i). Successful evolution in vitro of simple multicellular systems11,12 has been achieved (Fig. 1 j, k) and in silico evolutionary algorithms have been used to design reconfigurable organisms13,14.

Multicellular complexity is a tale of multiple scales, and understanding its origins, universal properties, and contingencies inevitably calls for an interdisciplinary picture in which theory has played a crucial role. As pointed out by the late Brian Goodwin15, the traditional, reductionist approach to the problem led to an inadequate view of the nature of organisms. Additionally, feedback loops connecting different levels (such as genes, gene networks and cell-cell interactions) are deeply constrained by the laws governing pattern formation16,17. This includes symmetry breaking18, the structure of attractor landscapes19,20 or collective properties21,22. Synthetic alternatives23 provide a unique opportunity of dissecting MC complexity24,25. Importantly, they allow the study of emergent form, function, and levels of autonomy and agency without an explicit evolutionary history14. Unlike traditional biological model systems, sculpted by aeons of selection, synthetic organisms allow us to observe the plasticity of life’s agential materials as they solve new problems26,27. Adaptive structure and behaviour arise in real-time in novel configurations not previously tested by evolution.

The early days of synthetic biology were primarily dominated by modifying microorganisms, which have become the perfect chassis to build complex cellular circuits capable of sensing and reacting to their environments in complex ways. On the other hand, stem cell technology and new cell culture methods have made it possible to reach new complexity levels associated with tissue or even organs28,29. Because of their relevance in bioengineering and potential biomedical impact, organoids have emerged as a unique opportunity for the study of diseases and as a complement to animal models. Finally, engineering behaviour, motion and self-repair in embodied, motile living systems have provided unexpected insights30,31.

In most case studies, the complexity of synthetic living agents is achieved through a combination of design and self-organization. Far from standard engineering, synthetic MC exploits intrinsic properties of living matter and offers opportunities for predictable design based on computational modelling and evolution in silico. Sometimes, the design principles depart from both natural and human-designed solutions. The current landscape of synthetic MC systems can be roughly decomposed into three (partially overlapping) classes:

-

1.

Synthetic multicellular circuits. This class involves cellular circuits that have been modified or introduced through genetic engineering within living cells, typically used as a chassis32,33,34,35,36. Many designs within this domain rely on a modular approach to circuit complexity based on standard combinatorial circuit design37,38,39. Cellular consortia have been used as MC implementations of all kinds of simple responses, from combining Boolean gates40,41,42,43 to pattern formation44,45. These designs involve strains interacting through chemical signals propagating in a liquid medium or diffusing over short distances on an agar plate.

-

2.

Programmable synthetic assemblies. The next step towards engineering MC systems exploits the predictable properties displayed by adhesion-driven spatial morphodynamics. Again, this bottom-up engineering allows predicting (i. e. programming) the outcome of the final spatial structure. It was early understood that cell sorting due to different adhesion energies could easily explain the self-organized aggregation of a set of randomly mixed cells46,47. Despite the self-organized nature of the process, it is possible to make some predictions concerning the spatial arrangements at steady state.

-

3.

Synthetic morphology and agential materials. One way of moving beyond cell-level engineering involves considering cell collectives as agential materials. These systems exhibit emergent properties at the system level that cannot be understood in terms of the properties of the constituents (genes and cells). This approach takes advantage of higher-order properties of embodied living matter (such as memory, context-sensitive navigation of problem spaces and homeostasis) to perform computations and design morphologies beyond the bottom-up principles of synthetic biology26,48. This class includes organoids and biobots. The latter can be defined as a fully biological agent designed and engineered to perform specific tasks. It is created using living cells, often through computational models that guide their self-organization and assembly into functional structures. Unlike traditional robots, biobots are entirely composed of biological material and can move, adapt, and interact with their environment with some degree of autonomy.

Synthetic multicellular classes

The three domains listed above have contributed to a new wave of exploring biological complexity and interrogating the principles of living systems. They have also provided a great source for novel biomedical research and applications. While some constraints need to be addressed (such as the limits to organoid size), some engineered constructs have revealed unique properties that question some old assumptions concerning the nature of computation or agency. The following section summarises each class’s key features before defining our challenges and open questions.

Synthetic multicellular circuits

While standard engineering design has exploited inert matter, bioengineering constructs are made of molecular and cellular substrates tied to living structures (or their components). What is different? If we compare with physical systems, physicist John Hopfield argued that what makes biology different is its potential to perform computations49. More precisely, biological agents that navigate their environments searching for resources (and thus involving purpose) “compute” incoming information (internal and external) and respond to it in adaptive ways. However, this general connection should not be seen as a claim that cells are machines50. In particular, the distinction between hardware and software that characterizes computer architectures is largely blurred when dealing with living agents.

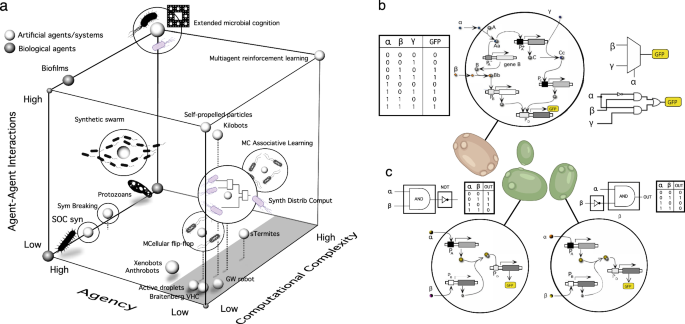

The first (but incomplete) layer to approach this problem from synthetic biology involves building logic circuits, including a whole array of logic gates, oscillators, band-pass filters, sensing-reacting networks and even sophisticated circuits capable of making decisions, such as targeting and killing cancer cells51,52,53,54,55. Complex dynamical states (such as critical states) have also been engineered56. Some of these examples, associated with UC implementations, are depicted on the left lower wall in Fig. 2a., where a space of synthetic biology designs has been depicted. Some case studies from nature, such as protozoans and biofilms, have also been included. They are indicated as small spheres, but a more nuanced view should display them as a more extended domain since they span a broad range of agencies. In this space, one axis introduces the main target of most designs: computational complexity, which describes the diversity of computational tasks performed by each circuit design. A second axis weights the relative role played by interactions between different engineered strains. Moving up, MC designs are represented by swarms57, learning consortia58, or MC computation59. Some examples, such as synthetic swarms, still need to be implemented. In all these examples, cell populations live in a well-mixed medium.

Engineering cells at the gene level have provided a broad range of simple computational circuits, including both unicellular (UC) and multicellular (MC) designs. In (a), a biocomputation space involving implementations based on consortia is shown. Here, the locations are relative to each other. We use three axes in this space: agency, computational complexity and the diversity of network interactions among cells. The bottom left of this cube includes several implementations that use a unicellular chassis, whereas MC consortia are found close to the right wall (grey area). Some designs, such as flip-flop memory devices100 or learning systems58, are obtained using a microbial consortium. However, computational designs can depart from nature and engineering, as shown by synthetic Distributed Computation models41,43,63. An illustration is provided in (b, c). In (b), a single-cell implementation of a multiplexer circuit (MUX), along with the truth table (left) and the corresponding combinatorial circuit (right). A simpler two-cell MUX is shown in (c) and involves much simpler circuits and reusable parts; notice that the two cells are not connected.

As the field advanced, a limitation in engineered design predictability became evident. Circuit design complexity in cells often causes cross-talk: a transcription factor linking genes disrupts other processes. This “wiring problem” arises from the evolved nature of cellular circuits, differing from standard designs due to natural selection and reuse of parts60. This is particularly relevant when comparing computers and living systems regarding hardware and software separation. In living systems, modularity and integration are intertwined. Experiments in evolutionary computation highlight this difference61: in silico evolved circuits perform better and are more reliable than human-made ones, though more challenging to understand.

To address this, a standard approach isolates circuit modules within cellular circuitry, and modularisation has become a design principle62. However, a different MC design allows a combinatorial approach, differing from traditional engineering41,63. We will use this approach to illustrate the potential for non-standard solutions within bioengineered agents. This uses distributed computation logic, creating a cell library with minimal engineering and no connections, producing an OR logic output63. Figure 2b–c illustrates this with a three-input, one-output multiplexer. While the UC design (b) requires several wires to connect the different genes, an MC alternative (c) shows that very simple, reusable constructs can be engineered within two cells, both including a GFP reporter gene and not connected to each other through communication signals. If one of the reporters is expressed, we take the system’s response as one (“ON”), whereas if none does, the output is zero (“OFF”).

We have skipped the third axis of our space in Fig. 2a. It is labelled as “agency” and reconnects us with Hopfield’s conjecture about the nature of living systems. Within the context of cells, agency refers to their ability to sense, respond to, and adapt to their environment through autonomous processes64,65,66. They expend effort to attain specific preferred states, using different degrees of problem-solving competency, learning, and active inference to resist perturbations and autonomously project their actions into new problem spaces. Living systems display agency, and we situate synthetic UC designs on the left wall since the individual agency is not modified by adding an extra genetic construct. Instead, complex circuits generated using cellular consortia (grey area) lack this property due to their disconnected nature and their special implementation, which requires all cellular components to perform the computation but not the interaction as a system with their environments. To incorporate this feature within synthetic MC systems, we must expand the reach of standard biocomputation designs. In this context, a pluralist stance, known as polycomputation31, suggests that living organisms harness various forms of information processing across different scales and contexts to control their development, behaviour, and adaptation. As discussed in the next sections, the embodied nature of MC complexity facilitates such multiscale processing, sometimes in unexpected directions.

Programmable synthetic assemblies

Developing complex multicellular agents requires two crucial features: (1) a mechanism to generate cellular diversity and (2) a predictable spatial organization that allows coherent system-level responses. Increasing cell types displays an evolutionary trend: with the rise of animals, the number of different cellular phenotypes has increased67,68. The current understanding of generating different cell states is grounded on the concept of attractors69,70. By using simple models of gene-gene interactions, it is possible to show that different stable expression states are accessible from different initial conditions. Small two-gene cross-inhibitory networks have achieved this71, and synthetic implementations exist72. But only recently has it been possible to design a circuit that displays many different states73, see Box 1.

How can we build MC systems with a spatial organization that can be predicted from the basic units (genes, molecules and cells) and their interactions? Getting closer to organs, organisms, and embryos implies introducing several extra layers of complexity, and the mapping between these components and the system-level properties is known to be highly nonlinear (Box 2). In other words, the nonlinear dynamics connecting gene network states with the unfolding of cell-cell interactions is far from trivial. This is particularly true with growing systems, where even the boundary conditions change through development. However, there is a domain of predictability given by engineering strategies that exploit some hierarchical cell-cell interactions. The best candidate, which has a long tradition within embryology and theoretical biology, is based on combining adhesion molecules.

Adhesion dynamic and the associated cell displacements occur via energy minimisation46,74. A model can be easily defined by a cell population on a discrete lattice. Cell states (cell types or engineered strains) are indicated as σn ∈ {0, 1, 2, . . . } and cells can move to neighbouring sites. To illustrate how the model works, consider a three-state example: two cell types plus empty space, to be indicated as σ1, σ2 and σ0, respectively.

Different cells have different adhesion strengths. These are defined by means of an adhesion matrix ({bf{{mathcal{W}}}}):

As defined, we have: ω(a, b) = ω(b, a), and ω(σ0, σ0) = 0. An energy function ({mathcal{H}}) that is defined for each lattice site μ i. e.:

where Γμ is the set defined by the nearest neighbours of a cell in position μ each of which occupies a position η, and has a defined state ση. If we try to swap one cell to one of its nearest locations, we first determine the new energy ({mathcal{H}}^{prime}) using the same expression. The energy difference between the original and the chosen location is (Delta {mathcal{H}}={mathcal{H}}^{prime} -{{mathcal{H}}}^{* }). The probability associated to this is given by the so-called Boltzmann rule:

where the parameter T is a noise factor tuning the degree of randomness associated to our model. The Boltzmann factor ({e}^{Delta {mathcal{H}}/T}) acts in such a way that if (Delta {mathcal{H}}=0), the probability of swapping is 1/2. For small T, the probability of swapping rapidly increases when (Delta {mathcal{H}} ,>, 0), whereas is very small when (Delta {mathcal{H}} ,<, 0). The relative weights of the matrix elements induce a hierarchy that allows to predict the kinds of patterns that can result from a given engineering design associated to adhesion properties (see75 for details).

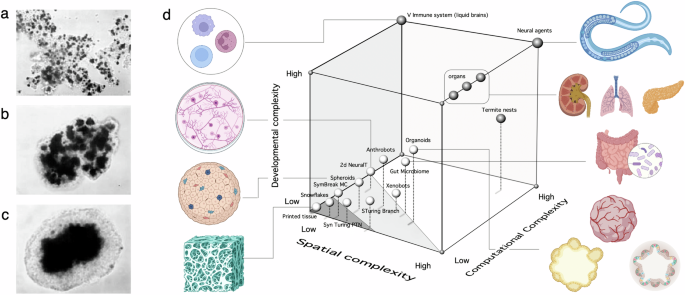

This simple microscopic set of rules provides the causal framework that explains re-aggregation experiments, as shown in the sequence of Fig. 3a–c displaying a set of dissociated cells (two types of retinal cells) evolves to a segregated structure76. Following these basic principles, orthogonal cell adhesion toolboxes have been designed to exploit the weight hierarchy, leading to synthetic programmable morphologies77,78. Furthermore, using a stochastic recombinase genetic switch allows programmable symmetry breaking and commitment to downstream cell fates79. This synthetic induction of SB could be an important step towards inducing differentiation in organoids.

Spatial self-organization (SO) rules associated with cell-cell nonlinear interactions are responsible for SO phenomena such as re-aggregation of tissues (a–c) due to differential adhesion (image adapted from ref. 76). This SO rule is part of the processes shaping MC embodied complexity, captured in (d) using a 3D space for natural (dark spheres) and engineered or artificially evolved multicellular systems (light spheres). Each system is located in terms of its relative positions, not in quantitative terms. Here, the three axes include (a) spatial complexity (how different cells are distributed over space), (b) developmental complexity (the relative relevance of self-organization and hierarchy participates in the building of the agent) and (c) computational complexity axis. The latter aims to capture the complexity of the computational decision-making actions displayed by each system. The current synthetic MC designs occupy the left corner, where synthetic circuits (dark grey) and embodied systems (light grey) are highlighted. A large void on the right reminds us of the large gap between current achievements and the natural counterparts of MC complexity.

The predictable nature of these designs faces challenges when dealing with the reality of more complex cellular aggregates and developmental processes. Along with symmetry breaking, population growth and the role played by physical forces beyond differential adhesion need to be considered, as well as intrinsic properties of cells and tissues as agential materials26.

Synthetic morphology and agential materials

The predictable nature of the previous examples becomes less reliable as we move towards complex MC systems, from organs to full organisms. The lack of predictability is due to the nonlinear nature of the genotype-phenotype mapping (see Box 2). In a formal fashion, it is a mapping Ω between the space of genotypes ({mathcal{G}}) and the space of (possible) phenotypes Φ:

In a nutshell, while the nature of adhesion rules allows programmable designs, living agents are the result of developmental programs that require growth and self-organisation, as well as regeneration, reproduction and behaviour. The information at the level of genes and gene-gene interactions will typically be incomplete in explaining the next complexity layers because the phenotype is not only the result of open-loop emergent complexity, but of directed navigation of anatomical morphospace guided by perception-action loops and setpoints encoded in bioelectrical, biochemical, and biomechanical properties. One crucial but traditionally ignored aspect is the presence of agency, i.e., the capacity for goal-directed changes to one’s self and the environment27,80. Agency itself is not only a general feature of life but also a multiscale property, because living organisms are composed of numerous layers of overlapping cooperating and competing agents which distort the option landscape for their parts and provide abstraction layers of competent subroutines for the systems they in turn comprise (?). Two synthetic counterparts to these MC agents are discussed here: organoids and living robots.

One successful implementation of embodied MC systems is provided by organoids, representing the last part of a timeline starting from re-aggregation experiments81,82. In a nutshell, organoids are in vitro tissue-engineered cell models that can behave as miniature versions of the full-fledged organs they represent. Along with the self-organised component of their development83, we need to use adult stem cells or pluripotent stem cells. The latter, in particular, have been exploited to generate different organoids, bringing the right conditions for a given set of cell types to emerge and get together. Afterwards, cell-cell interactions, both in signalling and mechanic forces, take control of morphodynamics.

Stem cell engineering has been used to study gene circuits and physical cues in morphogenesis. One particularly groundbreaking work was the self-organized emergence of optic cup organoids, later followed by brain organoids with regional identities using soluble compounds83. In all these cases, one major challenge is reproducibility, making organoids scalable and closer to their reference organs, and generating vascular or neural networks for realistic contexts. It is worth noting that improvements in the field have benefited from the emulation of native tissue properties like stiffness and geometry. Similar results in whole embryo models, known as gastruloids, reveal symmetry-breaking mechanisms and axis formation in models of early embryogenesis84,85.

The previous case studies lack two critical components of MC complexity. One is the order for free resulting from intrinsic system properties, which allow the material to exploit its nested multiscale competency. Secondly, two innovations were required for the rise of cognitive complexity in metazoans: movement and sight86. Movement is likely a precondition for the rise of the first multicellular cognitive agents87,88. Perhaps not surprisingly, it has been also suggested that these new classes of MC agents emerged around the Cambrian explosion with the rise of predators and associative learning89,90,91,92. Along with sensors, it allows the existence of behavioural patterns. Can these nontrivial features be implemented in engineered MC agents? Are the synthetic designs necessarily grounded in engineered gene networks or signalling circuits?

Biology features problem-solving at each level of organisation—a kind of agential material with agendas, homeostatic loops, and the ability to maximize or minimize specific goal states with various degrees of robustness despite novel circumstances. This is well-known in neuroscience, where the CNS provides a learning interface that allows simple stimuli, such as reward and punishment, to drive complex internal rearrangements that the trainer could not achieve via micromanaging the molecular details. Numerous examples of learning93, problem-solving, and optimization in biological systems such as molecular networks, cells, and tissues represent highly tractable targets for engineering top-down. The previously discussed examples cannot incorporate many aspects of agency we can find in the living world. The gap in the space of Fig. 2a is a reminder that designed computational circuits and programmable spheroids impose some restrictions on the behavioural repertoire of these constructs. There is a twilight zone that requires extra features capable of exploiting the intrinsic agential properties of cells and tissues.

A novel approach to the previous questions that provides one way to explore the voids in these spaces is provided by Xenobots13 and Anthrobots94, which show that endogenous functional capacities can be reached with no genetic editing or synthetic circuits. Xenobots are constructed from the skin and heart cells of the African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis). These choices allow them to move in predictable ways, pushing objects and working collectively (although their learning capacity and ability to achieve specific ends is only beginning to be investigated). Moreover, because of the chosen cells, they have self-repair properties. Importantly, they were designed using an evolutionary optimization algorithm that explored the space of soft physical shapes that could crawl in (a virtual) space. The optimal shapes were then sculpted in living tissue using microsurgery13,14. Anthrobots, on the other hand, are self-constructed moving spheroids obtained out of human lung cells that allow cilia-driven propulsion. By contrast to Xenobots, they require no evolutionary algorithms, manual sculpting, or embryonic tissues. Instead, they grow and self-organize into three-dimensional, living structures. Through precise biological and chemical cues, the cells naturally assemble into functional forms that can move and interact with their environment.

In both cases, instead of implementing desired functionality explicitly with transcriptional circuits, these living robots featured no genetic editing or synthetic circuits. Their capabilities, such as group reproduction, repair of neural wounds, etc., are endogenous and novel functions controlled by behaviour-shaping, not bottom-up engineering.

Regenerating and developing systems offer numerous examples of biological systems navigating the anatomical morphospace to solve novel problems. This capacity is a highly tractable set of built-in software modules accessible to the bioengineer, in addition to the specific pathways and molecules that are usually targeted. More recently, it has been claimed that living tissue can be understood (and efficiently controlled) as an agential material—a substrate with its own competencies and agendas in transcriptional, anatomical and physiological problem spaces that can be manipulated using the tools of behaviour science, not only biochemistry95. Indeed, work to understand the policies by which the homeodynamic set points scale, from the humble metabolic goals of single cells to the dynamic maintenance of grandiose construction projects such as regenerating limbs, has led to new approaches to combat the failure of this scaling, in the form of cancer96,97.

The three classes of synthetic MC systems reveal a very wide space of possibilities for further exploration. On one hand, the combinatorial nature of genetic circuits and programmable adhesion hierarchies provides a potential source of logic functionalities that can be combined with other features, particularly embodied architectures. On the other hand, the realization that key aspects of agency can be available for free, both in living tissues and in engineered biobots, reveals some unexpected properties of living matter that could be exploited to understand evolutionary constraints to the evolution of MC forms15,16,98 while pushing the boundaries of the possible. In the next section, we propose several open problems regarding this potential for synthetic multicellularity.

Open problems

Synthetic developmental programs: the possible and the actual

The suggestion that there is a universal toolkit defining a finite set of dynamical patterning modules8 could be studied within the synthetic MC framework. The programmable design of MC aggregates using adhesion molecules and symmetry-breaking mechanisms79 would be one example within this validation of the theory. The advantages provided by scalable generation of cell types73 and that can recapitulate the Waddington landscape concept99, combined with using other developmental modules (introducing polarity or dynamic oscillations), could lead to a taxonomy of possible embodied designs.

Embodied memory and learning

Current synthetic designs dealing with memory circuits rely on the standard approach of electronic switches. Synthetic flip-flops have been implemented using MC consortia100, and theoretical models have shown how learning could be implemented using MC consortia58. Can we move beyond these standard metaphors? It has been shown that learning in living systems can occur without a neural substrate93 and that GRNs and pathways can learn with no genetic changes needed101,102. Moreover, memory can also be mediated by electrical, rather than biochemical, signals, as shown recently in bacterial biofilms103. Learning can also be implemented at the global regulatory network level to interpret the nonlinear high-dimensional projection of time-dependent external signals by intracellular recurrent networks of genes and proteins104,105. New MC constructs using organoids or biobots could benefit from memory enhancements grounded in these novel views.

Synthetic collective intelligence

One dominant form of intelligent behaviour that rules the biosphere outside standard brains is based on collective intelligence (CI). In general terms, it refers to the enhanced capacity that emerges from the collective interactions among agents in a group, resulting in solutions that cannot be explained in terms of single individual actions. Insect societies provide the standard example106,107,108,109. It has been conjectured that the conceptual basis for CI can be translated into synthetic CI counterparts57. Moreover, electrical transmission of information in biofilms has shown the unexpected potential110,111 that reminds us of some general principles of neuronal tissue dynamics112. In recent years, collective intelligence has been recognized as a general principle in agential MC systems beyond animal societies22. Moreover, it has been pointed out that multicellular organisms and social insect colonies share fundamental common organizing principles113. Could we use synthetic MC designs to explore this connection? Can we exploit general information-sharing and processing principles in MC agents to build novel forms of embodied CI?

Synthetic neural cognition

Recent advances in microfabrication are allowing the development of precision neuroengineering methods through which neurons in in vitro cultures can be connected to one another in pre-designed ways114. These advances are revealing, for instance, the importance of modularity in the emerging activity of neural networks115, and pave the way for the design of prescribed collective activity in neuronal assemblies. Can they inspire the development of augmented embodied agents to expand the cognitive potential of spheroids, organoids or Xenobots? One obvious possibility is to follow the path of standard synthetic circuit design on a new scale: instead of using single cells as a chassis for engineered circuits, use whole cell assemblies as the chassis for engineered cell types carrying computational circuits.

Synthetic proto-organisms and life cycles

One challenge for synthetic MC designs is the design and development of complex assemblies that can be considered simple forms of organisms, developing from single cells in predictable ways and able to self-replicate themselves. Theoretical and computational models113,116, have shown that a discrete set of life cycles seems possible. What kind of life cycles can be obtained from synthetic designs? A minimal synthetic design should include the growth of a whole assembly from a single cell and the potential for some cells in the assembly to leave it by detaching from other cells, which should then be able to repeat the growth process. A successful example of such a synthetic counterpart of a life cycle is provided by the snowflake yeast model system11, a strain was been engineered to form groups via aggregation or via clonal development, and then evolved over many generations117. The experiments and models give support of clonal development favouring selection at the group rather than the cellular level. Anthrobots, on the other hand, also possess some key components for such a goal: they develop in a predictable way from single stem cells, complete their developmental path into a multicellular spheroid (with variable size), display phenotypic traits (associated with a variable shape), and display simple behavioural patterns including the ability to heal neural wounds. Xenobots, on the other hand, can display a remarkable (and once again, unexpected) property of organismality: self-reproduction118: the Xenobot autonomously constructs copies of itself using available materials in its environment. Is this an indication that there are multiple paths to build autonomous organisms and their life cycles? Further insight concerning the rise of synthetic MC systems is provided by and ecological scaffolding framework in which MC emerges after cells modify the environment that later becomes the scaffold giving rise to MC individuality119.

Building novel organs

The organ level of organization is a missing component of current theories of organismality. Although they are identified as discrete modules within animal bodies, we do not have a systems-level theory that provides predictable insights concerning their expected agency, number, nature and embedding within systems75,120. One possible path towards a better understanding of these mesoscale structures would be the synthesis of novel organs. A proof of concept would require building a stable, self-maintaining structure within a model organism and being able to perform a given functionality. Some inspiration in this context can come from the developmental processes leading to nest construction in social insects121,122,123, where self-organization, broken symmetries and specialised parts emerge (and are maintained and regenerated) out of swarm intelligence.

Multiscale synthetic holobionts

Current and future synthetic biology applications in the biomedical context often involve single UC agents as potential carriers. One major field of research involves the study of synthetic microbes used to repair dysbiotic microbiomes124,125 or even terraforming extant ecosystems126,127. In all these cases, we deal with the holobiont: an organism that contains other organisms, defining an ecological unit128. However, ongoing research reveals that we might need to expand this towards how MC agents can also interact with a context defined by tissues, organs or another organism. This includes the repair behaviour displayed by Anthrobots94 and the swimming microrobots made out of algae and coated with nanoparticles, used to deliver drugs directly to metastatic lung tumours129. Could MC agents persistently coexist (maintaining their individuality) with tissues and organs within organisms, defining a new class of synthetic holobionts?

Synthetic behaviour

Work in minimal animals such as C. elegans has shown that sophisticated experience-dependent behaviour, such as salt attraction or repulsion depending on previous cultivation conditions130,131, is encoded by small protein circuits in a single synapse132. This multiscale simplicity level encourages designing similarly complex behaviours in synthetic minimal animals. Moreover, the study of basal cognition opens new avenues to define behaviour133. Robots have been extensively used to study the evolution of adaptive behaviour134,135 An interesting avenue could be to use Xenobots to study fossil behaviour136 as represented by the tracks or burrows of ancient animals, which has been studied using robot models137. Could living robots with different levels of behavioural complexity recapitulate the taxonomy of fossil traces and help understand their origins?

Predictable designs?

A generic problem, namely, to what extent the predictability of the MC designs is feasible, remains to be addressed138,139. Most synthetic systems, from UC to MC, are built to live under in vitro conditions, and those used to target tissues or organs are used as a chassis for an isolated design that is largely disconnected from the rest of the cellular circuitry. In this context, one central topic within the study of how MC evolves concerns the constraints imposed by organismality on individual cells and their agential nature140,141. What kind of trade-offs are involved in the evolution of MC individuals? One fascinating concept, also to be addressed by synthetic biology, is the presence of a complexity drain, i.e. a loss of functional diversity at the cellular level as functional demands are transferred to the higher MC level142. The dream of understanding this hierarchical complexity under a top-down view, in ways close to standard engineering143 might be limited by the non-standard, tangled nature of cellular circuits and the presence of emergent phenomena. Although emergence is on our side in many ways24, shaping organoids and allowing behaviour out of form, we lack a general picture of the limits of what can be predicted. The voids within the spaces shown in Figs. 2 and 3 are a reminder of the difficulties associated with building MC complexity from scratch without the natural developmental context. Perhaps we must accept that we cannot engineer the way we did so far with passive materials, micromanaging everything from the bottom up. We must collaborate with the materials and take advantage of their basal cognition.

Discussion

What determines the intrinsic complexity of organisms and developmental paths? Morphological complexity results from a highly non-linear mapping between genotype and phenotype144. In this context, self-organization processes beyond the gene level must be considered when dealing with tissue, organ and organismal complexity. In this perspective paper, we have examined the problem of multicellularity under the light of its synthetic counterparts. We have used a broad range of model systems to achieve this goal, including engineered microbial consortia, organoids, and biorobots (Xenobots and Anthrobots). However, the list is not exhaustive, and we have not included some fascinating case studies, such as slime moulds, which occupy an intermediate position at the boundaries between cellular and multicellular systems145,146. Similarly, Physarum polycephalum, another slime mould, is a giant multinucleated but unicellular protist that exhibits multicellular-like traits associated with its morphological complexity147. They are a good reminder that much needs to be explored in terms of the deep connections between UC and MC spaces.

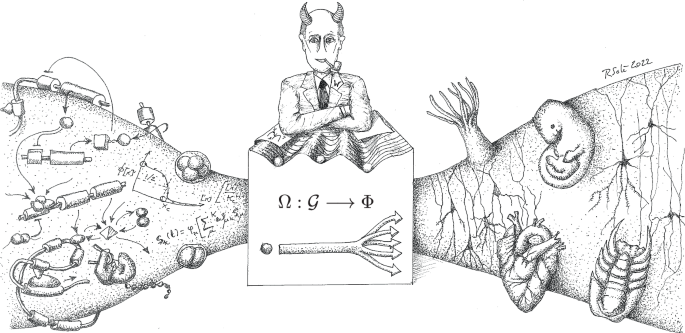

A universal outcome of self-organization is the presence of emergent properties, i.e., qualitative properties exhibited by a system that results from interactions between units but that cannot be reduced to the properties of those units. Recent theoretical and experimental studies have shown that inspiration from the physics of phase transitions might help to deal with these emergent properties and their universal patterns148,149,150. The growing ambitions of bioengineering towards creating artificial macroscopic systems face dealing with emergent patterns, emergent (primitive) cognition and their scalability. All in all, we have a real world where our goal of designing increasingly complex cell assemblies is challenged by the underlying nonlinearities that connect genotypes and phenotypes. Figure 4 summarises these difficulties using a metaphor: Waddington’s Demon. This hypothetical creature is inspired by the famous Laplace’s Demon, proposed by Pierre-Simon Laplace, capable of knowing the precise location and momentum of every atom in the universe. This information could predict the past and future of every particle, demonstrating a deterministic universe where the future is entirely predictable given complete knowledge of the present. Waddington’s demon, on the other hand, using all the available molecular information at the cellular and subcellular scales, tries to predict the outcome of all the microscopic interactions, but now failing to succeed due to the emergent nature of multicellular systems. The uncertainties of this mapping might be reduced by the presence of constraints16,17 and the universal properties associated with pattern-forming mechanisms8. In this context, theoretical and computational models help us test the different levels of uncertainty and how they depend on the presence of modularity and hierarchy151,152,153.

One major challenge for synthetic multicellular designs is associated with the lack of predictability that would be in place if the genotype-phenotype map were simple and different scales reducible to lower-level entities. Here we depict the “Waddington demon”: an idealized entity trying to predict higher-scale structures (organs, embryos or organisms) from the observable microscopic dynamics (genes, gene interactions and early developmental states). This cartoon summarizes the difficulties in predicting multicellular complexity, both within developmental biology and in bioengineering. Because of emergent phenomena, such a prediction might be difficult to achieve unless we use the right scale, ignoring the details on the lower levels (drawing by R. Solé).

Is the emergent nature of MC complexity a sharp obstacle to our understanding of how cells self-organize into tissues, organs or even organisms? Perhaps not. Although predicting precise properties of a given layer in the MC hierarchy from lower-level information might be very difficult or even impossible, some universal features might come to our help. The presence of a set of basic building blocks of developmental complexity, as defined by the developmental toolkit8 points to a potentially limited repertoire of possibilities, matching the pervasive character of evolutionary convergence154,155. Some structural properties of MC complexity might also be universal, including three layers in embryonic development or fundamental body symmetries. Our synthetic alternative to the natural world might be useful to determine if these commonalities (as well as the forbidden solutions) are due to contingencies, optimality or inevitable emergence.

Synthetic biology, stem cell-derived organoids, and the synthesis of living robots allow us to interrogate nature in novel ways, explicitly considering emergent properties that allow experimental validation of hypotheses and formulating models that deal with self-organization and agency. These tools can collectively bridge the gap between cellular- and tissue/organ-level biological models, resulting in a more realistic, functionally meaningful representation of the in vivo tissue spatial structures and the interactions between the cellular and extracellular environments. Organoid designs offer a unique opportunity to analyse the nature of emergence and the limits imposed by context and self-organization on the generative potential of bioengineering, while Xenobots and Anthrobots are the front layers that will help us understand complex biology at the organismal level, from development to behaviour. All the lessons obtained by answering the open problems discussed above will be instrumental to understanding the evolution of complexity and they will also allow the development of new ways to deal with health and disease beyond the molecular and cellular scales. Agential interventions could be used to learn about the state of tissues or to execute repairs.

Responses