Opportunities and challenges for patient-derived models of brain tumors in functional precision medicine

Introduction

The past two decades of central nervous system (CNS) tumor research have unveiled insights into cancer biology, tumor cells of origin, and molecular landscapes to produce a more precise reclassification of CNS tumors1. These biological insights have fueled the era of precision oncology, where tumor-specific molecular aberrations can be paired with targeted drugs designed specifically for that alteration. Unfortunately, the majority of CNS tumor patients have not benefited from this precision oncology paradigm. Between 2006 and 2020, when there was a massive emergence of novel targeted small molecule inhibitors, patient eligibility for targeted therapeutics increased modestly from 5% to 13% and the response to those drugs remained low, rising only from 3% to 7%2. In the NCI-MATCH trial, researchers studied the activity of 27 different genomically targeted therapies applied to 765 subjects with matching cancer genes, demonstrating an overall response rate of just 10.3% (79/765)3. Together, this highlights major limitations in the genomics-based precision oncology approach: (1) not all tumors contain an actionable mutation; (2) the actionable mutation seeming to drive a tumor may occur simultaneously alongside other redundant or even contradictory mutations; and (3) even molecularly identical tumors may have highly variable responses to the same drug. These limitations call for a paradigm shift toward functional testing, which evaluates therapeutic efficacy by directly treating individuals’ living patient tissue outside their body to gauge patient–specific activity and response.

Personalized functional testing using patient-derived models has great potential to guide care within the clinical setting and has already begun to be applied as enrollment criteria within clinical trials for many cancer indications. Acanda De La Rocha et al. implemented functional precision medicine (FPM) by enrolling patients with relapsed or refractory solid and hematological malignancies: using short-term patient-derived tumor cultures, they conducted drug sensitivity testing and genomic profiling to inform treatment recommendations. 83% of patients who received FPM-guided therapies achieved progression free survival (PFS) improvement exceeding 1.3-fold when compared to their previous treatments. Notably, patients who received FPM-guided recommendations showed a significant increase in both PFS and objective response rates compared to those who did not receive such guidance4. Several ongoing prospective clinical trials are aiming to achieve comparable results, including patient-tailored therapy for colorectal peritoneal metastases (NCT06057298), sarcoma and melanoma (NCT04986748), and breast cancer (NCT05177432)5. The EXALT trial, which uses patient-derived models to predict response in hematologic malignancies, demonstrated 1.3-fold longer progression free survival when using functional precision medicine (FPM)-guided care6. Co-clinical trials, where models undergo the same procedures and analyses in parallel with human trials have even been run on mice7. Both of these studies are underscored by the belief that correct treatment selection as early as possible can help prolong survival and improve overall outcomes, potentially at a much-reduced cost and less human impact.

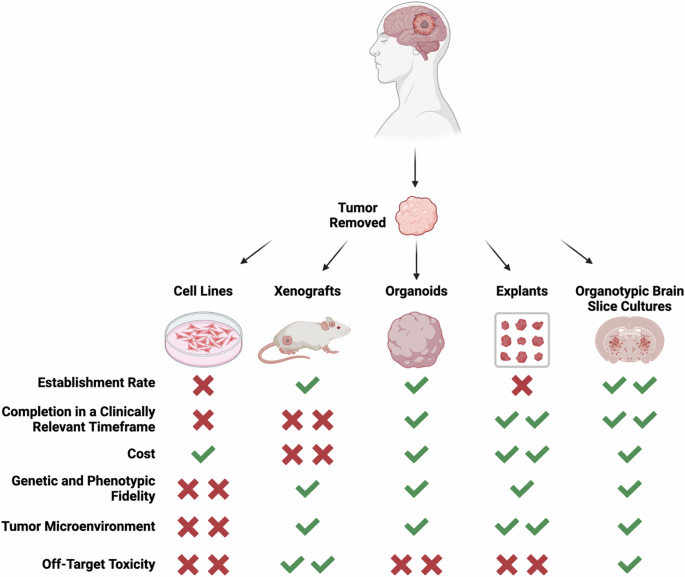

Within this review, we focus on FPM using patient-derived models of central nervous system tumors (PDMCTs), an indication that has been less explored compared to hematological malignancies and tumors which can provide an abundance of tissue such as ovarian cancers. The ability of FPM to effectively guide care is reliant on the quality of each model, and here, we have identified several key aspects necessary for a clinically informative model, including the establishment rate of tumors within each model, the time to establish tumors and perform the required assays, cost, genetic fidelity, the ability of each model to capture the diverse tumor environment, and whether each model can provide an assessment of off-target toxicity. Using these criteria, we analyze the strengths and weaknesses of each model, discuss their advantages and disadvantages, evaluate their utility, and propose aspects of each that can inform the next generation of precision oncology.

Patient-derived models of CNS tumors

The ideal PDMCT to support FPM would closely resemble an individual patient’s tumor and accurately predict their response to treatment. Developing such a model involves a unique set of requirements, distinct from those for drug development. No model will perfectly recapitulate all aspects of the in-situ tumor, so as scientists continuously improve existing models and generate new ideas, they must understand the strengths and limitations of each model. Next, we discuss several important criteria for a successful PDMCT.

-

(1)

Establishment Rate: A high rate of patient tumor tissue establishment into the PDMCT is fundamental for an effective PDMCT. Ex vivo maintenance is easier for aggressive cancers such as GBM, resulting in higher establishment rates within some PDMCTs. On the opposite end of the spectrum, lower-grade tumors pose challenges for reproducible ex vivo maintenance. For many different PDMCTs, the establishment rate is directly correlated with the grade and aggressiveness of a given tumor8,9,10. As a result, the establishment rate for a given PDMCT can be highly variable depending on characteristics of the parent tumor. Throughout this review, we provide examples of establishment rates for several different tumor subtypes within each PDMCT to capture this inherent variability. As the end goal of a functional model is to predict patient response before treatment of the patient themselves, a successfully ‘established’ functional model is a model that can, at minimum, be maintained throughout the necessary period of initial manipulation and drug testing and is able to produce a measurable response to treatment. If a patient’s tumor cannot be established ex vivo, that patient will not be a candidate for FPM. Importantly, here, we will not focus on establishment rates of models derived from other models, such as patient-derived xenografts generated from patient-derived cell lines or organoids; we only focus on models directly generated from resected, uncultured patient CNS tumor tissue.

-

(2)

Time: For PDMCTs to provide a clinically actionable output, they must do so in a clinically meaningful timeframe. Typically, the time between diagnostic surgery for a brain tumor and initiation of adjuvant treatment is only weeks. As a result, PDMCTs need to return results within this narrow timeframe—and the earlier the better11. Because each model is personalized, this timeframe includes both the time to establish the tumor for functional testing and the time required to complete the functional assays.

-

(3)

Cost: Not long ago, molecular profiling of cancers was too expensive to inform widespread precision oncology-based treatment decisions. As the costs of these assays have decreased, molecular profiling has become a standard diagnostic piece of the clinical treatment workflow. A PDMCT that can inform functional precision oncology-based treatment decisions will have to meet a similar metric, with assay costs low enough to allow wide accessibility12.

-

(4)

Genetic Fidelity: To have the best chance of predicting personalized treatment outcomes, PDMCTs must accurately model the parent tumor by maintaining its genetic profile and intratumoral heterogeneity. In general, fidelity refers to the capacity of the model to recapitulate the initially resected tumor; however, because genetic drift away from the initially resected tumor can occur both in the PDMCT as well as in the residual tumor left in the body, some PDMCTs can be designed to predict how the residual tumor may change over time and drift alongside the residual tumor. This longitudinal drift prediction is difficult to execute and verify, so throughout this review, maintenance of genetic fidelity compared to the parent tumor is considered. The PDMCT should therefore ideally maintain the bulk of the resected tumor as close to the original state as possible. Many models preferentially maintain specific populations, resulting in a biased cell selection that does not fully recapitulate the whole tumor. Additionally, genetic drift of the captured tumor in the model over time is an active concern in PDMCTs. Many models have undergone rigorous protocol optimization specifically targeting drift minimization. Frequently, models need to be tested promptly to accurately recapitulate the tumor and prevent genetic alterations. Furthermore, cellular states have been shown to drive malignant glioblastoma cell heterogeneity13. Understanding the underlying genetics and genetic drift has implications on the ability to maintain inherent heterogeneity13.

-

(5)

Tumor Environment Capture: Brain tumors encompass more than just tumor cells within their microenvironment including endothelial cells, neurons, glial cells, and immune cells14. Macrophages alone may comprise anywhere from 4 to 78% of human brain tumors with an average of 45% in glioblastomas, 44% in meningiomas, and 6% in medulloblastomas15. These are not innocent bystanders, as tumor behavior has been correlated with the interactions between different cell populations in the microenvironment16 and has also been the target for different therapeutics17. Additionally, the TME has been implicated in treatment resistance, an essential part of assessing a patient’s treatment sensitivity18. It is crucial to understand which, if any, of these connections and interactions the new model captures. Furthermore, some PDMCTs engraft tumor tissue into a system with a living environment that can form new connections and interactions between different cell populations. The microenvironment has been shown to influence the frequency of different cellular states in glioblastoma, having implications on tumor heterogeneity13. A PDMCT designed for functional testing should capture these diverse tumor elements and facilitate their interactions.

-

(6)

Assessing Off-Target Toxicity: While tumor-killing efficacy is a crucial aspect of potential treatments, assessing selective tumor kill and off-target toxicity is also critical. As the potencies of different drugs will vary, so will the harmful side effects. An intact external environment separate from the tumor microenvironment also allows for assessing on- and off-target toxicity at local, organ-specific, and/or systemic levels. The ability of a PDMCT to assess these different aspects of toxicity balances the efficacy of the treatment with the harmful side effects.

Currently, researchers are examining the ability of patient-derived cell lines, xenografts, organoids, explants, and tumors engrafted onto organotypic brain slice cultures to meet these metrics (Fig. 1).

Large strength denoted by two checkmarks, moderate strength denoted by one checkmark, moderate weakness denoted by one x, and large weaknesses denoted by two x’s. Schematic created with BioRender.com.

Patient-derived cell lines

Immortalized cell lines are a mainstay in preclinical testing for novel therapeutics19,20. Cell culture assay-based testing can be quickly repeated to demonstrate reproducibility, enabling patient-derived cell lines to play a crucial role in drug development. Research has firmly established that many immortalized cell lines diverge from their parent tumor over years of repeated passaging21. In fact, many immortalized cell lines no longer accurately represent the tumor type they originated from, let alone the individual patient22. To address this limitation, researchers have worked to enhance the genetic integrity of cell lines using improved culture methods21.

Patient-derived cell lines are isolated from minced pieces of patient tissue collected during resection and grown in a variety of different culture media. Yet, unlike immortalized cell lines purchased from repositories such as the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), establishing new patient-derived cell lines is a cumbersome process23. While individual protocols to establish these cell lines may vary, several key components remain consistent. Tumors are often received shortly after surgical resection with many protocols stating time from resection to laboratory processing of under two hours24,25. Even Chew et al., who were able to establish cell lines with samples up to 48 hours post resection, noted that time from surgical resection to laboratory processing is a determining factor in the establishment of new patient-derived cell lines26. Laboratory processing involves at least one of, but sometimes both, mechanical and enzymatic digestion to break up the original tissue into smaller fragments24,25,26. Following dissociation, the remaining tissue fragments are then moved to media and given time to establish. No one media is universally used, though a move away from serum-based media and towards DMEM or neurobasal media was seen following the finding that serum-based media can lead to significant drift from the parent tumor21. A variety of different supplements are added to medias with hopes of maintaining as much of the original tumor as possible; most commonly a combination of EGF, FGF, and/or PDGF27.

Given the ease of use of these models and the relatively established protocols, patient-derived cell lines remain one of the most highly used patient-derived models of CNS tumors. As a result, a multitude of established characterization protocols have been developed for patient-derived cell lines with some of the most common listed below. Flow cytometric analysis, immunofluorescence, and immunohistochemistry can be used to study marker expression22,24,25,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. Western blotting can be used for protein identification, protein quantification, and verification of gene expression29,32,36,37. LC-MS can be used for histone modification identification and quantification and metabolite quantification36,38. RNA sequencing can be used for gene expression profiling19,24,32,36,37,39,40,41,42. DNA sequencing can be used for identifying genetic variants, copy numbers, and methylome profiling19,24,25,29,30,33,34,35,36,39,41,42,43,44. Whole genome sequencing can be used to identify somatic mutations and pathogenic germline mutations42,43,44. PCR can be used to look for specific brain tumor associated genes29,34,44,45,46. Microphotography can be used for phenotypic characterization22,30. These different established methods enable deep levels of characterization of novel patient-derived cell lines.

Establishment rate

The success rates for the establishment of patient-derived cell lines can vary dramatically based on the tumor grade and subtype. As patient-derived cell lines are among the most common models, their establishment success is abundantly documented. High-grade cancers, such as glioblastoma (GBM), can establish more easily, while lower-grade tumors like low-grade glioma (LGG), tend to establish less successfully due to their slow growth22,41,47,48,49. Consequently, the establishment rate, which refers to the ability to proliferate continuously and be passaged repeatedly, of this model type is highly variable (Table 1). Grube et al. found that 47% of their IDH-mutant glioblastoma cell lines can undergo multiple passages when grown in serum-based media22. Xie et al. achieved similar success with glioblastoma cell lines initially cultured in serum-free media, allowing for over 8 passages at a 54% success rate41. In contrast, lower-grade tumors had markedly lower success rates. When Xie et al. attempted to expand to other tumor types using the same protocol, they successfully established only one grade III tumor out of 13, and zero grade II tumors (they did not even attempt grade 1 tumors)41. This finding underscores the strong positive correlation between tumor grade and the ability to establish a cell line41. The lack of success in establishing LGG cell lines negatively impacts research diversity and clinical relevance19,44,50 (Table 1).

While many groups derived cell lines from fresh tissue, creating new cell lines from cryopreserved tissue enhances tissue availability and eases workflow. Mullens et al. observed a 59% establishment success rate from cryopreserved tissue and 63% from fresh tissue when cultured in serum-based media for glioblastoma cell lines30. This cryopreservation and storage of tissue enhances access to patient tissue without significantly decreasing its viability.

Pediatric cases also tend to have lower establishment rates29,31,32,33,37,42,43,48,49,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58. Xu et al. documented their efforts over an 8-year period during which they procured 161 pediatric tumor samples48. Out of 161 samples, only 5 cell lines were successfully established, and among those, only 3 grew over multiple passages—a strikingly low success rate of less than 2%48. Similar to adult tumors, higher-grade pediatric tumors tend to be easier to grow and are thus overrepresented. The majority of pediatric patient-derived cell lines represent medulloblastoma31,42,48, although recent surgical improvement, enabling core biopsies of a once inoperable tumor, has led to an increase in the number of DIPG and DMG cell lines29,32,37,43,49,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59. Despite this, the way to obtain large tumor samples from DIPG and DMG tumors remains from autopsies43,52. Considering the demand for representative models, several pediatric brain cancer cell line resources have been established including the Children’s Brain Tumor Network, Seattle Children’s Brain Tumor Resource Lab, and St Jude’s Pediatric Brain Tumor Portal60,61,62.

Time

Grube et al. reported that IDH-mutant glioblastoma cell lines establish within an average of 22 days, with a doubling time ranging between 2 and 14 days22. Researchers commonly conduct drug sensitivity analysis using various well-established assays, including (3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) (MTT) and propidium iodide assays, obtaining results within 48 to 96 hours. Grube et al.’s method allows completion within the clinically relevant timeframe, from the establishment to functional assay completion. However, lower-grade cell lines, which establish less readily and have significantly prolonged generation times, may prevent completing functional testing within the same relevant timeframe.

Cost

After establishment, maintaining a cell line becomes cost-efficient, requiring only a specialized cocktail of growth factors and supplements. Patient-derived cell lines, once established, exhibit high throughput capabilities compared to other patient-derived models, further reducing costs20,43,46,63,64,65,66,67 (Table 1).

Genetic fidelity

Patient-derived cell lines raise a major concern regarding their genetic fidelity as significant cell selection can occur when tumor cells adapt to growing in a plastic dish. This has prompted many researchers to investigate what genetically remains conserved from the original tissue9,19,21,22,30,32,33,37,38,41,43,44,45,46,47,49,50,55,57,58,68,69 (Table 1). Grube et al. found that prolonged passaging leads to genetic changes, including loss of GFAP expression22. Efforts to mitigate genetic drift resulting from clonal expansion involve researchers limiting cell culture passage to maintain cell lines that better represent the original tumor70,71. Furthermore, researchers associate the use of serum-based media with genomic and transcriptomic alterations, resulting in the loss of stem-cell-like cancer cells21. Consequently, researchers now propagate many patient-derived cell lines in serum-free conditions.

Despite these precautions, propagation remains favorable only in select tumor sub-populations, leading to reduced tumor heterogeneity and the loss of the original microenvironment with continued passage37,43,44,47,54,57,58,69,72 (Table 1). Xie et al. profiled the gene expression of 48 glioblastoma cell lines and found that over 50% of them differed in subtyping from their original host. This difference could have occurred for a multitude of reasons, but the authors attributed it to the loss of intra-tumoral heterogeneity and clonal selection41.

Tumor environment capture

Patient-derived cell lines are unable to capture any inherent microenvironment from the original tumor. Nonmalignant cells resected alongside tumor cells are much less suited for ex vivo culture, and clonal expansion of mostly rapidly proliferating malignant cells will occur when exposed to optimized medias, such as Grube et al.’s serum-based media22 and other serum-free media formulations21. As a result, patient-derived cell lines consist almost solely of tumor cells, even though macrophages alone can make up to 78% of the parent tumor15. This does not allow for the assessment of any interactions between tumor cells and non-tumor cells that are present in the tumor microenvironment. Additionally, patient-derived cell lines lack an external environment to study new interactions between the tumor cells and a non-native microenvironment. To understand the effect that an external microenvironment has, patient-derived cell lines must be paired with another model.

Assessing off-target toxicity

Patient-derived cell lines have no inherent way of assessing off-target toxicity. To assess off-target toxicity, patient-derived cell lines must be paired with another model.

In summary

Patient-derived cell lines face many challenges in representing their original patient tumor. Their resemblance to the matched patient is limited, even at low passages. Vast improvements have refined protocols and media compositions, aiming to establish cell lines that better recapitulate clinical observations. Despite these improvements and subtype-specific media, high-grade tumors still dominate, leaving a scarcity of low-grade tumor models. Additionally, this model is unable to capture the tumor microenvironment or provide a way to assess toxicity. Although drug sensitivity assays are straightforward and well-optimized once models are established, patient-derived cell lines still face challenges in becoming functional brain cancer models.

Patient-derived xenografts

In contrast to other patient-derived models, researchers establish patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) within living animals. PDXs most commonly involve engrafting fresh patient tumor tissue into immunocompromised mice73. This can be done either subcutaneously or orthotopically73. Beyond that, there are fewer deviations in protocols as compared to that of cell lines. In the context of this review, we are only looking at PDX models which are directly derived from patient tissue, not cell lines or organoids. Tissue undergoes either mechanical or enzymatic digestion rapidly after surgery74,75. This dissociated tissue is then injected into the mice. Several different solutions can be used to resuspend and inject the tumor tissue, such as Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution, Matrigel, and PBS76,77. These varieties are often due to preferences in how to increase the establishment rate. Matrigel is commonly used to increase establishment rate, though the translational aspects and impact on tumor biology are not known78. The largest variation in PDX development comes from mouse strain choice. A few commonly used strains include NOG, NSG, immunodeficient BALB/c nude mice, athymic nude, and J:NU mice74,75,76,77,79. Depending on the host animal’s immune system and where the tumor is engrafted, these animal models may capture some of the tumor microenvironment, which cell line models lack73. Additionally, the host environment enables recapitulation of anatomical characteristics of brain tumors such as angiogenesis, invasiveness, hypercellularity, and necrosis47,80.

As with patient-derived cell lines, novel PDX models can undergo significant characterization. Flow cytometric analysis, immunofluorescence, H&E, and immunohistochemistry can be used to study marker expression42,43,74,75,76,79,81,82,83,84. Western blotting can be used for protein identification, protein quantification, and verification of gene expression77. RNA sequencing can be used for gene expression profiling42,43,74,77,79,82,83. DNA sequencing can be used for identifying genetic variants, copy numbers, and methylome profiling42,43,74,75,76,79,82. Whole genome sequencing can be used to identify somatic mutations and pathogenic germline mutations42,43,74,79,82,83,84. PCR can be used to look for specific brain tumor associated genes75,76. Given the higher complexity of the model, more clinically relevant characterization such as MRIs can also be completed.

PDX models have become mainstays of preclinical testing. Several consortia efforts have worked to expand access to PDXs, including initiatives by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and EurOPDX85. This model is both time- and cost-intensive, which impacts the feasibility of completing functional testing within a clinically meaningful timeframe.

Establishment rate

In xenografts, the successful establishment is defined as the prolonged persistence and growth of the tumor over time. Although widely used, PDX establishment rates are less commonly reported than those of patient-derived cell lines. Similar to other PDMCTs, the success rate of establishing xenografts directly correlates with the grade of the primary tumor8,40,42,43,74,75,76,77,79,82,86,87,88,89 (Table 2). In gliomas of varying degrees, Zeng et al. reported success rates of 33.3% for grade II, 60.0% for grade III, and 87.5% for grade IV gliomas8. Notably, the PDX generation success rate for pediatric brain tumors is similar to lower grade tumors at only 30%42,43,74,82,89 (Table 2). These establishment rates are much higher than patient-derived cell lines.

Time

The establishment process alone for xenografts can take several months to over a year8,40,42,43,77,84,86,89,90,91,92. Even in tumor types with high success rates such as glioblastoma, tumor onset post-transplantation can be over 4 months86. Functional response in xenografts is commonly assessed through tumor size and survival studies. Once the tumors are established, the completion of functional testing in PDX models may last weeks to months. This timeframe puts PDX models well beyond the clinically relevant window of 4-8 weeks.

Cost

Generating PDX models is expensive, with commercial companies charging over $5000 for the testing of a single therapy in a cohort of animals93. The expenses for animal acquisition and maintenance accumulate rapidly. These costs impact sample size and experiment replication capacity in studies, making xenografts a challenging model for high-throughput testing.

Genetic fidelity

The implantation of fresh patient tissue can occur at various anatomical locations, most commonly subcutaneous or orthotopic (PDOX). It has been shown that both the cell origins and implantation site influence phenotypic and genetic similarity to human GBM73. Recent findings suggest that PDXs undergo murine-specific tumor evolution characterized by changes in copy number alterations—resulting in genetic differences from the patient’s original tumor94. Consequently, there is considerable variability among biological replicates in the composition of tumors observed in PDXs. Although this heterogeneity may be advantageous because it models patient population diversity, it also poses challenges for experimental standardization and reproducibility needed in individualized functional testing40,43,72,73,79,82,90.

Tumor environment capture

PDXs have been shown to better maintain non-tumor cells, including immune and stromal cells, than patient-derived cell lines95. These cells have however been shown to be replaced by murine cells over time, limiting the ability to study their interactions96.

An advantage of PDX is the presence of a new microenvironment which can be assessed to understand the interactions of tumor cells with new non-tumor cells. While the tumor microenvironment in this model is somewhat intact, it is of rodent origin. Researchers must account for the differences between human TME and rodent TME, both molecularly and anatomically97. Subcutaneous PDXs of CNS tumors, while technically simpler to inject, fail to fully replicate the original tumor microenvironment. In contrast, orthotopic PDXs (PDOXs), where the tumor is implanted in its natural organ, enhance tumor fidelity90. Golebiewska et al. showed that intracranial tumor implantation to form a PDOX recapitulates angiogenesis and invasiveness associated with GBM90.

PDXs are often generated in immunodeficient strains of mice to avoid tumor rejection. Therefore, how a therapeutic interacts with the adaptive immune system cannot be modeled by PDXs. Recent efforts to overcome this barrier and aid with the testing of immunotherapies involve the use of humanized mice98. However, this emerging trend is still primarily conducted using cell lines rather than fresh patient tissue98,99 and can be quite costly.

Assessing off-target toxicity

PDX models are well-positioned to inform healthy tissue toxicity and maximum tolerated doses. The biodistribution of a drug throughout the rodent body can be assessed, along with its effects on other organs100,101,102,103. This approach has even been used to recommend combination therapies based on toxicity in leukemia PDXs indicating a new avenue to explore in brain PDX’s104. This enables PDX models to be used to assess toxicity at the local, organ, and systemic levels.

In summary

PDXs are an incredibly valuable PDMCT insofar as they can support fresh human tumor tissue in their natural location, with some degree of intact microenvironment, and be used to understand tumor behavior and response to a wide variety of drugs. A major limiting factor, however, is the time and cost associated with this model, which significantly limits its applicability for functional testing (Table 2). While PDOXs offer the advantages of including components of the tumor microenvironment and assessing the toxicity to healthy tissue, the lengthy generation time limits PDXs in providing timely insight for an individual patient. Additionally, the low success rate, high cost, and absence of a fully intact immune system further constrain the applicability of PDXs as a widely implemented and accessible model.

Patient-derived organoids

Organoids are increasingly being developed and used for brain tumor investigations. Initially termed organotypic tumor spheroids, organoids represent “self-organized, three dimensional (3D) organotypic structures, recapitulating the original organ-like composition in vitro” 97. In contrast, spheroids refer to 3D serum-free cultures97. The most common protocol for establishing organoids involves mechanically cutting fresh patient tissue and growing it in specialized media97. Organoids can more effectively capture cell-to-cell interactions in a native 3D orientation. Furthermore, researchers can derive organoids in a brain-region-specific fashion, closely resembling the region in the brain from which the tumor originated105,106.

Development of patient-derived organoids begins with flask preparation. Several different modifications to standard cell culture flasks may be done such as plating with agar or ultra-low- or non-attachment plates12,107. When patient tissue is received107, unlike in cell line or PDX models, manual digestion is the primary tumor dissociation method107. The media and growth factors in which the organoids are cultured can lead to region-specific similarities, allowing them to better reflect the anatomical region the tumor was removed from108. As a result, this leads to appropriate media and growth factor selection being essential for accurate model development. Organoids are then propagated by manual mincing of large organoids into smaller pieces to avoid necrosis at the center12,109. Additionally, organoids are often cultured on a shaker as compared to the standard static method used in most cell culture12. In histological studies, organoids have been shown to maintain cellular and nuclear atypia and vasculature12. In particular, cellular morphological characteristics are conserved between parental tumors and organoids12. Many different patient-derived cell line characterization protocols have been adapted for their use in organoids with some of the most common listed below. Flow cytometric analysis, immunofluorescence, and immunohistochemistry can be used to study marker expression12,110,111,112,113,114,115,116. Western blotting can be used for protein identification, protein quantification, and verification of gene expression116. RNA sequencing can be used for gene expression profiling12,110,111,112,115,116,117. DNA sequencing can be used for identifying genetic variants, copy numbers, and methylome profiling110,116. Whole exome sequencing can be used to identify somatic mutations and pathogenic germline mutations12,111,114,116. PCR can be used to look for specific brain tumor associated genes12,111,115. Confocal Microscopy can be used for phenotypic characterization12. These different established methods enable deep levels of characterization of novel patient derived organoids. Their strength as a functional model lies in their ability to establish and undergo functional testing within a clinically meaningful timeframe. Despite this, their applications are still limited due to high cost, variability, and tissue heterogeneity105,118.

Establishment rate

Successful organoid establishment involves tissue fragments self-organizing into their 3D structure while necrotic areas die out97. As seen in other models, the success rate for generating organoids varies vastly in a subtype-specific and grade-dependent fashion40,90,111,119,120 (Table 3). Jacob et al. reported an overall success rate of 91.4% for GBM organoids, but the success rates dropped to 66.7% for IDH-mutant gliomas and 75% for recurrent tumors12. This establishment rate is comparable to that of PDXs and higher than cell lines. These findings highlight the necessity of tailored protocols for individual tumor types to improve success across all CNS tumors.

Additionally, there are practical applications of adding cryopreservation into the manufacturing pipeline. For diseases that are scarce, such as sarcoma, explant cryopreservation can make available primary, patient-derived material for a wide array of sequential studies including personalized medicine and linkage studies121. Cryopreserving and storing tissue also improves access, as it can be shipped and/or accessed at a later time point.

Time

GBM organoids can be generated more rapidly than cell lines. Organoids are often ready for functional drug testing within a timeframe of 1-2 weeks40,90,111,112,114,120,122,123,124(Table 3). Abdullah et al. were able to successfully establish LGG organoids though it took significantly longer with the testing only available after a minimum of four weeks119. Researchers can analyze the functional response of organoids through a variety of different methods, including Cell Titer Glo assays and single-cell sequencing90,112,120. With drug testing lasting less than a week, this enables functional testing on organoids to be completed within a clinically meaningful timeframe.

While patient-derived organoids have decreased high-throughput drug screening capabilities compared to cell lines due to the technical complexity of culturing, they can still be screened on a large scale90,125 (Table 3). For instance, Bian et al. modified brain cancer organoids to simultaneously screen 5 different drugs over a 40-day time period126. Although Bian et al. derived the organoids from a human embryonic stem cell culture and genetically modified to resemble different subtypes of brain tumors, this finding indicates the scalability of patient-derived organoids for drug screening126.

Cost

Currently, organoids are more expensive than cell lines because generating and maintaining them requires specialized expertise, resulting in higher costs and a more labor-intensive process97. However, organoids are more scalable than PDXs, enabling medium throughput screening, given their decreased cost and reduced size.

Genetic fidelity

One advantage that patient-derived organoids can have over patient-derived cell lines is their maintenance of genetic features observed in the parent tumor12,40,90,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,119,120,122,125,127,128,129,130,131 (Table 3). Organoids can be cultured once or continuously passaged, with the organoids being manually cut between passages. Golebiewska et al. investigated the effects of organoid culturing on a genetic level. Their study demonstrated that their organoids largely preserved copy number alterations and genetic variants observed in matched patient tissue90. However, they also identified significant genetic discrepancies between their organoids and the original patient tumors. Occasionally, these discrepancies varied among organoids from the same patient, possibly due to tissue sampling bias and specific subclone selection upon engraftment90.

GBM, IDH-mutant organoids can exhibit similar tissue architecture, cellular morphologies, transcriptomic signatures, somatic variants, and cell populations seen in parent tumors12. However, the composition of cell types can drift over time, indicating the importance of using organoids as early as possible to minimize drift. Several groups recommend using only the original organoid without passaging to reduce genetic drift12.

Tumor environment capture

Jacob et al. successfully recapitulated aspects of the microenvironment, including hypoxia gradients, microvasculature, and immune cell populations within organoids12. This allows for the assessment of native tumoral interactions. However, these morphologies diverged over time, further supporting the use of organoids in early passages. As organoids do not introduce a new microenvironment, there is no way to assess novel interactions.

Assessing off-target toxicity

Similar to cell lines, tumor organoids do not include an external environment. They would need to be coupled with another model to assess any off-target toxicity. Researchers have established healthy human cerebral organoids, also known as ‘mini-brains,’ from pluripotent stem cell-derived embryonic bodies132. These organoids have recently been used to assess drug toxicity, indicating they would pair well with tumor organoids133.

In summary

Overall, organoids have gained popularity as a patient-derived model and have already been utilized as a drug screening platform12,40,90,109,110,112,113,114,116,117,120,123,125,129,131,134,135 (Table 3). Protocol improvements have enabled organoids to better maintain aspects of tumor heterogeneity and the tumor microenvironment. With no intact external environment, this necessitates generating separate “healthy” organoids to assess off-target toxicity. However, patient-derived organoids are associated with a higher inherent cost and a more limited ability for high throughput screening compared to patient-derived cell lines. Improved protocols that capture the full spectrum of CNS tumors position organoids as a promising model for FPM.

Patient-derived explants

Patient-derived explant models (PDEs) are ex vivo cultured pieces of patient tissue that conserve the original histology. Researchers develop them from surgically resected solid tumors without tumor deconstruction136. PDEs are commonly generated by creating slices of the original tumor sample using either a vibratome or a tissue chopper, resulting in minimal changes to the tumor’s spatial composition137,138,139. These explants have been used to screen drugs for non-CNS tumors, accurately predicting drug resistance in over 85% of cases for colon, gastric, and colorectal cancers136. In a correlative clinical trial, researchers assessed the chemosensitivity of over 200 patients using the Histoculture Drug Response Assay (HDRA), an explant-based assay, against mitomycin C, doxorubicin, 5-fluorouracil, and cisplatin, showing a high correlation between HDRA results and clinical response140. Promisingly, researchers can establish and test brain tumor PDEs within a short timeframe, requiring only a few weeks. As a result, there are fewer established protocols, though they follow the same general concepts. Tissue is first embedded in a low melt agarose in PBS141. It is sliced using a vibratome, resulting in explants between 300 and 750 uM thick141,142,143. These are typically cultured on top of transwell membranes with a neurobasal-based media underneath141. This protocol enables the maintenance of original anatomical features from the site of origin. Further protocol optimization of these models is needed to fully assess clinical translatability.

Additionally, there are fewer established protocols that exist for model characterization. Flow cytometry, immunofluorescence, and immunohistochemistry can be used to study marker expression84,137,141,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152. Western blotting can be used for protein identification, protein quantification, and verification of gene expression142,148. RNA sequencing can be used for gene expression profiling84,137,143,151,153. DNA sequencing can be used for identifying genetic variants, copy numbers, and methylome profiling84,143,148,152,153. LC-MS can be used for metabolite monitoring147. Whole genome and exome sequencing can be used to identify somatic mutations and pathogenic germline mutations137. Confocal imaging to monitor phenotypic changes142,144,149. PCR can be used to look for specific brain tumor-associated genes143,146,148,150. In CNS models, however, their application has been limited due to low establishment rates and high complexity of culturing.

Establishment rate

Though not as broadly used, PDEs have been established from many different CNS tumor types including adult high-grade tumors137,138,139,142,143,144,145,147,148,149,150,151,152,154, adult low-grade tumors142,149,150, adult metastatic tumors84,153, and pediatric high-grade tumors150 (Table 4). Davenport and McKeever emphasize that success depends on the quality of the received tissue; for example, necrotic tissue or burnt tissue should be removed before PDE generation139. This practice has become a mainstay in explant development protocols. Successful establishment of CNS PDEs occurs when cells start migrating from the explant and form the “sun shape”155. Using this technique, Souberan and Tchoghandjian showed an establishment rate of around 50% for GBM155. This success rate is slightly lower than patient-derived cell lines but significantly lower than both xenografts and organoids, especially for aggressive HGGs. Since the number of established PDEs depends directly on the size of the original tumor, functional testing with PDEs may be limited for brain tumors. To address this limitation, Horowitz et al. combined their GBM explants with a microfluidics device to enable the testing of more therapies within individual explants141.

Time

PDEs offer an advantage in terms of speed: PDEs offer some of the fastest drug sensitivity measurements among patient-derived models84,138,142,143,144,145,147,148,151,152,153,154 (Table 4). Researchers can assess PDE treatment response through histological assessment or RNA sequencing151. Haehnel et al. established GBM PDEs, treated them with temozolomide and radiation, and assessed the effects on the tissue within 14 days151. This rapid turnaround makes PDEs well-suited to provide information in a clinically meaningful timeframe.

Cost

Overall, this approach incurs costs similar to organoids. Specialized growth factors and culture media are needed for explant survival. Like organoids, they can be optimized for medium throughput screening.

Genetic fidelity

In a GBM PDE model, the maintenance of transcriptional heterogeneity observed in matched parental tissues is evident137. Brain tumors are known to have high intratumoral heterogeneity which is replicated by PDEs137,139,142,144,147,151,152 (Table 4). However, this significantly restricts the reproducibility of explant experiments and complicates translation. Therefore, researchers must use multiple explants from different tumor regions to accurately capture the entire tumor response, even though this reduces the number of different drug sensitivities that can be assessed per tumor.

Tumor environment capture

PDEs closely resemble tumor architecture and inherent microenvironment observed in the patient. The histopathology of GBM PDEs is conserved over a 16-day time period138. ScRNA-seq analysis reveals that GBM PDEs contain immune cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts, and oligodendrocytes, enabling the study of existing tumor-microenvironment interactions ex vivo137. However, explants lack infiltrating cells ex vivo, which limits their ability to model adaptive immune responses and limits the ability to assess new interactions.

Assessing off-target toxicity

Importantly, PDEs contain only patient tumor tissue, lacking healthy tissue for assessing off-target toxicity or effects on other organs.

In summary

Although PDEs offer rapid functional results—critical for FPM models—they have not gained widespread traction compared to other models. This discrepancy may partially result from the lower establishment rate seen in high-grade gliomas compared to patient-derived xenografts and organoids. Additionally, creating and maintaining explants is challenging, and each explant is derived from a unique region of often heterogeneous tumors, furthering the complexity and difficulty of this model. Enhancing protocol development to improve PDE establishment rates would increase its value as a FPM tool.

Patient-derived organotypic brain slice cultures

Organotypic brain slice cultures (OBSCs) are an emerging patient-derived model of brain cancer. Although researchers have used OBSCs in various neurodegenerative diseases, their recent prominence stems from their application as a model for brain cancer92,156,157,158. OBSCs, derived from rodent brains, provide an intact microenvironment onto which patient-derived tissue is implanted. Source material can consist of cell lines, freshly resected patient tissue, or cryopreserved patient tissue92,157,158,159,160,161. Patient-derived models are developed using a combination of patient tissue and rat brains. Rat brains from 8-day old pups are sliced using a vibratome creating 300 uM thick slices92. Freshly or cryopreserved patient tissue is then manually dissociated, transfected with lentivirus, and seeded on top of OBSCs resulting in reproducibly engrafted microtumors92. This protocol does not maintain the original anatomical regions within each tumor.

With fewer existing models, characterization is limited. Immunohistochemistry can be used to study marker expression and whole exome sequencing can be used to identify somatic mutations and mutations92. Further characterization is needed to understand clinical translatability. OBSCs with patient tissue have an establishment rate of 100% across all tumor grades or subtypes. Their rapid assay speed fits well within the clinical timeline, holding promise for FPM. Yet, the rodent-origin microenvironment on which the tumor is seeded lacks an adaptive immune response, limiting its applicability to immunotherapies.

Establishment rate

The establishment of patient tissue on OBSCs is defined by quantifiable tumor persistence four days after engraftment. Recent studies confirmed the successful seeding of tissues from 10 different patients with various tumor subtypes onto OBSCs, achieving a 100% success rate92. These tumors included both low-grade and high-grade tumors, such as meningioma and GBM92. This significantly contrasts with other patient-derived models, where success rates strongly correlate with tumor grade (Table 5). Among the discussed PDMCTs, OBSCs exhibit the highest establishment rate.

Time

One of the key advantages of this patient-derived model lies in its speed. Tumor response is assessed via bioluminescent signaling from transfected patient tissue92. Patient tumor tissue persisted and was poised for drug screening for 8 days after engraftment, aligning with the existing clinical timeframe between resection surgery and treatment selection92. Slightly faster than even PDEs, OBSCs can support both engraftment and functional response within 5 days.

Cost

The ability to generate 12-15 OBSCs from a single rat pup reduces costs compared to xenografts, aligning more closely with organoids and explants. The use of animals adds to the existing cost, but unlike PDX models each animal results in an n of 12 to 15. Additionally, OBSCs can be readily scaled for medium throughput capabilities92.

Genetic fidelity

Studies have demonstrated that OBSCs with patient tumor tissue more accurately reflect the original tumor than patient-derived cell lines from the same tumor92. Additionally, the use of OBSCs as a functional drug screening platform has been supported by transcriptomic profiles158. Like all other models, any sampling error inherent to the biopsy specimen to misrepresent the entire intratumoral heterogeneity will impact the OBSC model. Processing fresh patient tumor tissue and then subdividing it into separate tumor aliquots results in a mixture of all cell populations present, ensuring reproducibility across different replicates92.

Tumor environment capture

Researchers generate OBSCs from rodent tissue due to a lack of access to healthy human tissue. Consequently, the microenvironment where patient tissue is seeded originates from a different species. Nevertheless, this tumor-OBSC microenvironment accurately replicates tumor growth, invasion, and cellular interactions observed in vivo157. IHC staining reveals microenvironment interactions with patient tumor tissue, including the formation of reactive astrocytes in its presence92. This results in activated microglia and astrocytes supporting tumor maintenance and growth. There is however no existing adaptive immune system within this model.

Assessing off-target toxicity

Importantly, the living tissue substrate on which the patient tumor is seeded contains neurons and astrocytes, providing a substrate of “normal” brain tissue159. This healthy tissue allows off-target toxicity assessment of various drug treatments on non-tumor brain tissue, enabling comparisons of different drugs regardless of their potencies92 (Table 5). This model enables the assessment of toxicity at a local level but still lacks a method to assess toxicity at an organ or systemic level.

In summary

OBSCs represent an emerging patient-derived model with excellent promise. Unlike other models, the establishment success rate of OBSCs is not tied to tumor type or grade, making them applicable to all CNS tumor types. Yet, the current major limitations are the non-human origin of the provided microenvironment and the lack of an adaptive immune system. Positively, OBSCs combine scalability and speed, making them feasible within clinically relevant timeframes, and highlighting their potential for FPM.

Cultured patient tissue models

To realize a move toward functional precision oncology, patients’ own tumors must be tested ex vivo using high-fidelity PDMCTs. A multitude of new and highly complex models have been developed to conduct functional drug sensitivity assays; this review focuses on models that directly leverage the living patient tumor. Some models take already existing PDMCTs and develop a new model from them, such as bioprinted material established from patient-derived cell lines162 and organotypic cultures established from patient-derived xenografts163. Other models, such as brain-on-a-chip models, are still undergoing development before they can be applied to living patient tissue164. As these models require the prior culture of patient tissue before model development, they fall outside of the scope of the models discussed here. These models could one-day leverage uncultured patient tissue.

Future perspective

Advances in PDMCTs continue to be made in several tumor indications outside of the CNS. A patient-derived tumor organoid model has been shown to accurately predict responses to chemotherapy in stage IV colorectal cancer, as described by Wang et al. 165. Sachs et al. have created over 100 primary and metastatic breast cancer organoids with matching histopathology, hormone receptor status, HER2 status, and DNA copy number variations. Remarkably, the organoid in vitro drug screens were consistent between in vivo xeno-transplantations and patient response166. This important work has moved to commercial development as well. Several companies are now conducting FPM studies using organoids, with the majority directed towards cancer treatment. Vivia biotech, Crown Bio, and 2CureX are examples of companies with current commercial efforts, with locations spanning from Spain, to the United States, to Denmark167.

In order to see the same advancements in CNS tumor PDMCTs as we have seen in other challenging tumor indications, studies must account for the dynamic and adaptive CNS tumor environment as well as advancing treatment regimens and produce results within a timely manner. One example of this is the work Logun et al. have done with patient derived glioblastoma organoids treated with autologous CAR-T cells in a phase 1 study168. Treatment response of the patient derived glioblastoma organoids correlated treatment response of patients, highlighting a remarkable advancement in CNS development of functional precision oncology.

The future of functional testing will not only offer a wide range of assays to guide patient care via direct treatment of PDMCTs, but could also provide more accurate and clinically relevant models to develop new therapeutics. As the field’s ability to develop, maintain, and store human CNS tumor tissues as PDMCTs for functional testing continues to improve, the increased abundance of fully characterized cell lines, organoids, and other PDMCTs is already allowing these invaluable models to impact clinical drug development6. Significant efforts to establish and fully characterize models for preclinical use are already underway: the NIH recently initiated a multi-million dollar effort to improve and disseminate high-quality, characterized, and validated cancer models for preclinical testing, many of which may now be purchased through ATCC169. For example, many clonally expanded cell lines harboring wild-type BRAF or BRAFV600E+ mutations are currently used for preclinical drug development. While response rates of these cell lines to MAPK inhibitors are directly tied to mutational status170,171., response rates of BRAFV600E+ pediatric low-grade gliomas to newly approved MEK inhibitors is only 47%172. More robust, heterogeneous PDMCTs available to screen novel therapeutics during preclinical development could greatly improve the quality of novel therapies entering clinical trials.

Valid PDMCTs play a critical role in ushering in the next phase of functional precision oncology. Each of the existing models described above requires further development, which in turn will require more primary CNS tumor specimens. This task involves close coordination among multiple parties such as neurosurgeons, neuropathologists, neurooncologists, clinical research staff, operating room staff, and institutional tissue procurement groups. Because of this, hospitals and facilities performing CNS tumor surgeries need the capability and resources to process tissue or transport specimens to a suitable facility. Given that many CNS tumors require rapid post-surgery treatment decisions, the speed at which these models provide clinically useful data is crucial. Additionally, substantial research and clinical trials are necessary before clinicians widely accept such a platform for informing treatment decisions.

Summary

PDMCTs are the next step needed to stratify care and improve patient outcomes. FPM can provide clinicians with more upfront information to guide treatment decisions. Given the unique needs of FPM platforms, there are three models poised to fill the existing gap: organoids, explants, and organotypic brain slice cultures. These models all strike a balance between a high establishment rate, fast speed, low cost, maintained fidelity, and microenvironment presence. Organoids and explants, despite limitations in tumor type-specific success rates and tumor heterogeneity, closely mimic the original tumor and its structure. Despite the absence of the original tumor structure and the non-human microenvironment where tumors are seeded, organotypic brain slice cultures can address the establishment rate and tumor heterogeneity limitations that affect organoids and explants while mimicking the original tumor. Researchers are examining the clinical applicability and predictive accuracy of all three models. Within FPM, certain models may be more suitable for specific applications. For instance, a model designed for assessing immunotherapies requires a robust and responsive immune system, whereas a model focusing on microenvironment changes needs a well-established local microenvironment. Consequently, models may need further characterization before being used in specific applications. With several models entering preclinical and clinical testing, the clinical use of FPM is just beginning.

Responses