Opportunities and challenges in modelling ligand adsorption on semiconductor nanocrystals

Introduction

Since their debut in the 1980s, colloidal semiconductor nanocrystals (NCs), or quantum dots (QDs), have demonstrated phenomenal functionality and versatility and have been applied in a growing number of fields, such as electronics and optoelectronics, photovoltaics, photocatalysis, sensing, quantum information, etc1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Many of these applications, if not all, are highly dependent on their sizes, shapes, majorly exposed facets, and hierarchical structures. For example, QDs offer tunable light trapping, which vastly increases the efficiency that thin films cannot achieve in solar cells11. Increased selectivity in photocatalytic reactions can be achieved by purposefully tailoring semiconductor NCs into shapes that dominantly express certain facets over others12. Moreover, superstructures formed via the assembly of NC building blocks exhibit long-range order and properties (e.g., charge carrier mobility) that differ from randomly dispersed and isolated NCs13,14,15. The level of control over the morphology of individual NCs and the pattern of their superstructures required in these applications can be precisely tuned during synthesis with the aid of surface-capping ligands, thus making ligands an indispensable part of the success of semiconductor NCs16.

In the early days, ligands were primarily used to stabilize the NCs from aggregation, and oleic acid (OA) was, and still is, the most prevalent choice for this purpose16. Later studies showed that the chemical identity of ligands is deterministic of the structural outcome17, the success of which has been repeatedly demonstrated in shape-controlled metal NC synthesis18,19,20. Furthermore, it has also been reported that ligands other than OA can be utilized to form core-shell structures with interesting optical properties21, and ligand exchange can facilitate shell outgrowth, enabling photoactive composite materials22,23. Thus, with a burgeoning number of morphology-dependent applications, the demand for discovering new, functional structure-controlling ligands is ever-increasing.

To date, the progress of effective ligand discovery for colloidal semiconductor NCs is still driven by experiments via the Edisonian approach. This trial-and-error strategy is labor-intensive, time-consuming, and economically expensive. Ideally, molecular design is most efficient if theoretical guidance is provided. Such improved efficiency has been manifested in many other fields, such as polymers, biomolecules, colloidal chemistry, and even shape-controlled metal NC synthesis24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. A common feature shared by these fields is the abundance of computational and theoretical studies. These studies are capable of not only predicting structures beyond the resolution of experiments but also helping to gain insights into the working mechanism, a critical piece of fundamental understanding in realizing the rational design of functional materials. While certain aspects and species have been well-attended, such as the binding modes of OA on metal chalcogenide QDs and surface passivation upon ligand adsorption35,36, questions largely remain open, particularly when the spatial scale of interest is large (e.g., assembly37), ligand chemistry becomes complex (e.g., bi-functional linkers38), entropic effect is non-negligible (e.g., ligand exchange21), etc.

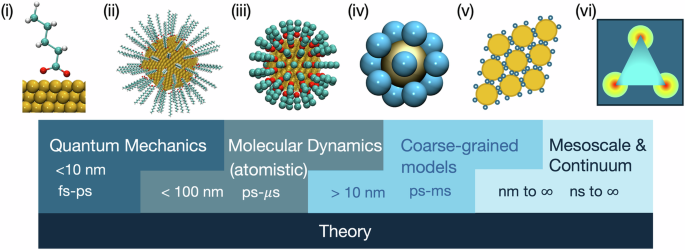

A typical computational study to understand the adsorption and roles of ligands in solid-state NC synthesis, assembly, and functionalization involves one or more methods in the categories of quantum mechanics or ab initio calculations, atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, coarse-grained (CG) MD and Monte Carlo (MC) simulations, and mesoscale and continuum simulations (Fig. 1). Depending on the scope of specific scientific inquiries, one can choose a proper method from the category at the relevant scale and provide physical insights into the workings of these systems. Among these methods, all but ab initio calculations require pre-defined energetic or mechanical property input other than simple atomic structure-related quantities (e.g., mass and electrons). Effective interactions obtained from the left side of the scale can be input into the method on the right and enable simulations at larger spatial and temporal scales. For example, semi-empirical force fields (FFs) fitted against data obtained from ab initio calculations (i.e., leftmost in Fig. 1) allow one to obtain dynamical behaviors of a similar system in atomistic MD simulations with preserved chemical information, such as bond strength and intermolecular interactions. Also, the effective potential between two objects obtained from atomistic MD simulations can be further input into a coarse-grained (CG) model to simulate particle assembly behavior, which can be directly compared to experiments27.

i a typical setup for ligand-adsorption calculation in DFT, (ii) a ligand-coated NC with full atomistic details, (iii) and (iv) CG models with different resolutions, (v) assembly modeled by CG patchy particles, and (vi) finite element analysis in the continuum regime. Overlaps between categories are deliberately shown because a variety of methods fall under each major category, and simulation limits are also highly dependent on hardware capacity146. All methods are supported by theory, which has a blurred boundary of scales (cf. first-principles DFT and classical DFT), and they can be used in lieu of simulations. A careful selection of two or more methods, including theory, in this spectrum constitutes a multiscale framework, which is capable of connecting atomistic details to observables in experiments.

To show the impact of computational and theoretical work on unraveling complex phenomena and guiding experiments, take polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)-assisted Ag nanocube formation in ethylene glycol (EG) solution, for example39. A bare Ag NC enclosed by {100} and {111} facets without surface-adsorbed ligands should adopt a cuboctahedral shape under the Wulff construction since the surface free energy of Ag(100), γAg(100), is higher than that of Ag(111), γAg(111). It was argued that the Ag(100)-favored binding of PVP lowers γAg(100). Thus, the Ag cubes formed with PVP were thermodynamic products. Such facet selectivity was verified using dispersion-corrected density functional theory (DFT) calculations40, but the connection between molecular binding and interfacial free energy could not be established unless the interfacial configurations of PVP were known, which required a larger-scale simulation. To enable MD studies on the Ag-EG-PVP interface, a set of MOMB FF for the Ag-PVP-EG interface was fitted to the adsorption modes and energetics obtained from DFT41. The FF was then fed into atomistic MD simulations, from which γ of PVP-covered Ag(100) and Ag(111) were calculated with thermodynamic integration. The results show that facet selectivity was not strong enough to shift the equilibrium shape from a cuboctahedron to a cube; subsequently, a kinetic-based hypothesis, where PVP was assumed to regulate solution-phase Ag deposition flux to different facets, was explored31. Here, atomistic MD simulations were used again to acquire the potential of mean force (PMF) of an Ag atom along the deposition path. The PMFs were then fed into the Smoluchowski equation from diffusion theory to calculate the mean first-passage times (MFPTs) for a solution-phase Ag to reach the indicated facet, the inverse of which yielded the deposition rate. Finally, the facet-specific deposition rates were integrated into the kinetic Wulff construction and supported the hypothesis that the Ag nanocube formation was kinetically regulated by distinctively different PVP layers on Ag(100) and Ag(111) due to its facet selectivity, contrary to the previously believed thermodynamic influence30,42. Together with other work in this series, the learned principles helped guide several later experiments43,44.

The above approaches that employed simulation methods at two or more scales (see caption of Fig. 1) is called multiscale modeling. The span in space and time allows us to connect simulations and experiments, unravel complex phenomena, and accomplish rational design. It undoubtedly has promising prospects to accelerate the advancement of the nanomaterials field, as demonstrated in the series of studies on shape-controlled metal NC syntheses. These methodologies are not system-specific and, thus, can also be applied to semiconductor systems. Despite the remarkable similarities, computational studies that resolve the roles of ligands in growth and assembly are relatively rare for semiconductor NCs compared to those of metals. Part of the reasons can be attributed to the variety of species of semiconductors and the intrinsic molecular complexity therein. Another important aspect is that atomistic MD studies are greatly lacking due to the inaccessibility of high-quality FFs, which somewhat breaks the connection between the understanding at the bonding level and the continuum regime. In this perspective, we will follow the scales from left to right in Fig. 1 (excluding mesoscale and continuum), starting from ab initio methods and then to atomistic and CG simulations, discuss the promises and challenges in modeling ligand adsorption on semiconductor NCs, elaborate on how simulations are used to understand their roles in crystal growth and assembly and look toward the opportunities in computation-guided inverse design.

Success of ab initio methods

In a generic view, colloidal semiconductor NC systems consist of solvents, inorganic particles (i.e., semiconductor NC core), and solution-phase additives (e.g., precursors, ligands, and salts), where the ligands adopt a standing position and are densely packed on NC surfaces16. The NC-ligand-solvent interface is critical in facilitating phase transition, including crystalization and assembly. Organic ligands are mostly used, although they also exist in other forms45. Two typical families of organic ligands include linear or dendrimeric molecules consisting of a head group and an aliphatic tail and functioning linkers of more complex, diverse chemistry8,35,38,46. For linear and dendrimeric ligands, the head group favors the inorganic NC surface, and the tail heavily interacts with liquid-phase species and other ligands. Therefore, it is often believed that the interactions between the head groups and the NC surfaces dictate the morphology of single NCs, and the tails regulate assembly or alternate the properties of the nanomaterial. Some linkers possess two NC-favoring moieties on both ends, with a middle section primarily serving as a spacer, and thus are used to connect NCs to form superstructures16. In both scenarios, the distinct roles of different segments of the organic ligands allow us to simplify the problem via a “separation of space.”

In the spectrum shown in Fig. 1, both quantum mechanics calculations and MD simulations can be used to reveal molecular details. However, the practice of MD is often restricted by the availability of FF, which is largely missing for semiconductors. Without the need for input other than atomic structure-related quantities, ab initio methods are ideal in this case, on top of their high accuracy35,36,47,48,49,50,51,52. Yet, these calculations can be extremely demanding if all chemical details and solvation effects are considered. Because of the distinct roles of different parts of the ligands in NC growth and assembly postulated above, we can zoom in at the relevant site and consider only the critical chemical species in ab initio calculations. In such a reduced scheme, ab initio methods, particularly the first-principles DFT, have been so far the most adopted methods to study ligand adsorption on semiconductor surfaces. Another common practice to model ligand adsorption is to break down a large molecule and use molecular analogs for the moieties of interest. For example, oleate (OA-), the deprotonated OA that adsorbs on semiconductor NC surfaces, is often approximated by butyrate or acetate to study head group binding.

In addition to system size, another major challenge associated with DFT calculations is incorporating van der Waals (VDW) interactions53. In earlier studies, this was usually overlooked due to technical limitations54. With the method development to account for VDW interaction, we have seen progress moving from suites consisting only of plane wave pseudopotentials (e.g., projector-augmented waves55) and Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) parameterization of the generalized gradient approximation56 to the addition of DFT+U, the Tkatchenko-Scheffler vdW schemes, Grimme’s DFT-D2, DFT-D3 and now DFT-D4, etc57,58,59,60,61. By employing dispersion-corrected DFT, studies have shown that the VDW interaction can dominate physisorption40,62. While the majority of currently studied ligands adsorb on semiconductor surfaces via chemisorption, as we expand the ligand library63, the chemical nature and versatile functions of these ligands could necessitate the need for dispersion-corrected DFT in future studies. Next, we review several notable works based on first-principles DFT.

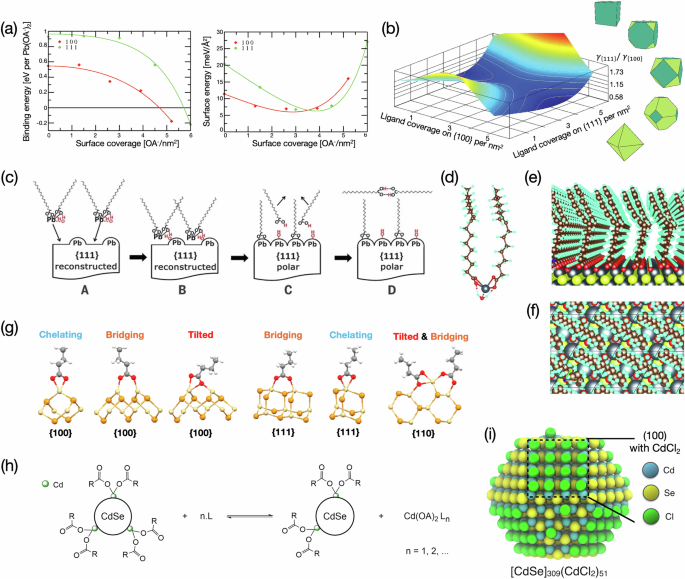

To understand the influence of ligands on NC morphology, Bealing and coworkers constructed a framework that predicts thermodynamic equilibrium shapes of PbSe NCs at various OA- coverage based on binding energies obtained from DFT (see Fig. 2a, b)36. Like any crystalline structure, semiconductor NCs are not always spherical and can exhibit well-defined geometries enclosed by Miller index facets. At equilibrium, the total surface free energy is minimized, and shapes can be determined from the Wulff construction if facet-specific surface free energies are known64. Solution-phase ligands are capable of lowering the surface free energy upon adsorption, thus shifting the equilibrium shapes away from that of bare crystals. Since the stronger the binding affinity is, the more passivated the surface will be, evaluating the head groups-NC interaction is crucial to understanding the thermodynamic roles of ligands.

a The nonlinear dependence of binding energy per ligand on surface ligand coverage, which resulted in a nonlinear correlation between surface energy and coverage. b A structure map as a function of ligand coverages on {100} and {111} facets, with corresponding shapes in the cube-to-octahedron transition at different γ{100}/γ{111} ratios shown in the right. Revised and reprinted with permission from ref. 36, Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society. c A proposed growth mechanism of PbS{111} facets based on energies obtained from DFT. d–f Example structures optimized in DFT that were used to propose the mechanism in (c). Note that both (e) and (f) are shown with periodic images based on the monoclinic cell in (f). Reprinted with permission from AAAS, ref. 47. g Different binding modes of OA- analog on CdSe are examined in ref. 35. Reprinted with permission from ref. 35, Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society. h Illustrative L-type-driven Z-type displacement reaction equation. i The reduced configuration to study L-type-driven Z-type displacement in DFT. Reprinted with permission from ref. 48, Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.

For PbSe, the most stable facets are {100} and reconstructed {111} (R {111}) facets and OA- preferentially bind to R {111} than {100}. For single crystals only enclosed by these two facets, all transition shapes from octahedron to cuboctahedron to cube are accessible under the Wulff construction (see Fig. 2b), and the exact shape is determined by the ratio of their surface free energies, γ{100}/γ{111} (Fig. 2b). The authors used DFT, specifically the projector-augmented wave method and generalized gradient PBE exchange-correlation functional55,56, to calculate binding energy per OA- on the two surfaces and evaluated their values as a function of ligand coverage. The surface energy was then estimated from the ligand coverage and corresponding binding energy per OA- (Fig. 2a). This meticulous work revealed a nonlinear dependence of surface energy on ligand coverage and avoided erroneous results from simple linear extrapolation based on single ligand binding. The authors presented the temperature map in Fig. 2b and correlated shape outcomes with ligand coverage. Although the entropic component from solvation is largely ignored in this work due to the limitation of DFT (cf. free energies should be the input in Wulff construction), it inspired later studies on the influence of ligands on metal NC growth where interfacial free energies were calculated from MD simulations coupled with thermodynamic integration31.

The success has made DFT a credible method for accessing ligand adsorption. Since the 2010s, we have seen an increasing number of studies in which simulation and experiment work collaboratively to investigate the growth mechanisms. In the work of Zherebetskyy et al., the authors proposed reaction intermediates and hypothesized a reaction mechanism to grow PbS(111) based on previous experimental observations (Fig. 2c)47. Then, DFT energy calculations were performed on the proposed initial, intermediate, and final configurations to evaluate the free energy change of the reaction, which included a complex of OA-, Cd, and water (Fig. 2d) and surface-adsorbed OA- (Fig. 2e, f). These theoretical calculations suggested that each PbO precursor reacts with two OAs to form a complex Pb(OA-)2 ⋯ H2O. After being deposited on a vacancy site on reconstructed {111} facet, one OA- gains a proton and returns to the solution phase, leaving an OA- and a hydroxyl group (OH-) attached to PbS(111). The proposed hydroxylation model was first a “surprise” but subsequently supported by experiments, perfectly demonstrating the power of the simulation-guided approach and synergy between simulation and experiment. Furthermore, given the stoichiometry revealed by the reaction mechanism, the authors further optimized packed OA and OA- layer on PbS(100) and PbS(111), respectively. Similar to the work of Bealing et al., knowing the ligand coverage enabled the determination of the shifted equilibrium shape under the Wulff construction. The predicted structure was, again, verified by experiments.

Another critical aspect of understanding ligand binding on semiconductor NCs is to depict the exact coordination structures. This is especially important for deciphering surface termination, binding sites, stoichiometry, chemical reactions associated with the growth stage, and NC property alternation after ligand exchange. The convention of Green’s notation in covalent bond classification has been adopted to describe NC-binding ligands, namely, the L-, X-, and Z-type ligands65. For example, by providing one electron to the NC-ligand bond, carboxylates, including OA, are classified as X-type ligands for metal chalcogenide nanocrystals. Even for the same type of ligands, they may adopt multiple coordination modes on surfaces, and each of them can be observed with a weight statistically related to binding energetics. More work has recently been devoted to distinguishing the subtle differences among multiple coordination modes.

To identify the facet-dependent coordination structure of carboxylate ligands on CdSe NCs, Zhang and coworkers conducted a comprehensive examination of butyrate and acetate adsorption (i.e., both are analogs for OA-) on polar zinc-blende CdSe(100), CdSe(111), and nonpolar zinc-blende CdSe(110) (Fig. 2g)35. Coordination modes optimized included chelating, bringing, and tilted. It was found that the chelating mode constitutes the dominating mode by having the highest binding energy for both {100} and {111} facets, and the optimized structure for nonpolar {110} requires two carboxylates in tilted and bridging modes on a substantially reconstructed surface. In another study, Drijvers and coworkers used DFT to look into a phenomenon called L-type-driven Z-type displacement, which occurs on OA-coated cation-rich NC surfaces (i.e., each additional surface metal cation binds with two OA-) through displacement with L-type ligands (e.g., amines) (Fig. 2h)48. Notably, the authors worked with a 3 nm CdSe cuboctahedron rather than periodic surfaces to explore the dependence of displacement thermodynamics on the sites (i.e., facet, edge, and corner). When working with a whole crystal, the computation cost is drastically higher than periodic slabs. Thus, the authors further simplified OA- from acetate to Cl-, which allowed them to explore multiple sites in a relatively comprehensive configuration setup (Fig. 2i). Thermodynamic stability was assessed by taking the energy difference between the optimized initial and final structures. Note that both studies worked closely with experiments to provide insights while being verified.

Besides binary compound semiconductors, DFT methods have been employed in more complex semiconductors, such as perovskites, and ligands other than OA. For example, Zhao et al. looked into the capability of aromatic head groups, and Quarta et al. explored various amines to stabilize CsPbBr3 based on the energies of structures optimized in DFT49,50.

Lastly, as final words in this section, it is worth pointing out that the ab initio method is not just limited to the DFT level theory and structure optimization. First-principles DFT is generally a popular choice for studying interfacial phenomena associated with semiconductors because of the attainability of electronic structures at reasonable computational efficiency. For systems where dynamics are important but lack FFs to describe at larger spatial and temporal scales, ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) is more suitable, but at extremely high costs49,66. In the next section, we will introduce a few methods to circumvent such difficulties.

Expanding complexity: theory and molecular dynamics simulations

Organic ligands regulate NC morphology and their assembly in forms far beyond ground state configurations. In complex colloidal systems, dynamics and solvation can play important, often essential, roles in ligand adsorption and resulting functions. As previously mentioned, a decoupling of moieties allows us to break down the molecule and approach headgroup binding using DFT. Focusing on the close proximity of the NC-ligand interface allows us to unravel the thermodynamic influence of the ligand on shapes. In a zoomed-out picture, where particle-particle behaviors (e.g., during assembly) and dynamics in and between different regions (e.g., atom deposition from solution phase to interface) are pronounced, the influence of the tails and long-range colloidal interactions becomes significant27,67. Some other cases even involve macromolecules like proteins whose length scale of relevance exceeds DFT capacity45. In these cases, large-scale atomistic MD simulations and CG models are the best computational tools13,68,69,70,71,72,73,74. In addition, for mathematically well-defined systems, such as polymeric ligands, theories can alternatively be used, and they often do not demand intensive computations75,76. Despite all the advantages, we do not see as many studies on semiconductors and ligands using MD as in DFT due to, again, a lack of high-quality FFs. In this section, we will list a few MD and theoretical approaches that can be used to quantitatively evaluate ligand binding and mobility, estimate their structural and energetic profiles, and model reactive events therein. We will also discuss how they can be used as a part of a multiscale framework.

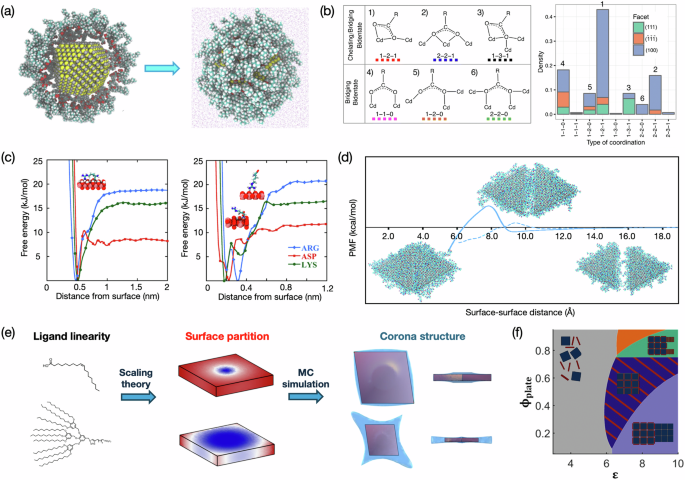

Small NC surfaces contain a high fraction of under-coordinated sites. These high-energy sites are usually unstable and may counteract desired properties. Introducing new ligands via exchange is an emerging strategy to stabilize surfaces, thus significantly pushing the practicality of semiconductor NC applications21. Understanding ligand exchange demands a correct, comprehensive picture of how ligands are distributed on a non-planar structure enclosed by multiple facet types and how their coordination with surface cations/anions influences stability and mobility. In an effort to probe this important aspect, Cosseddu and coworkers used an atomistic MD workflow to systematically assess OA- dynamics on CdSe69. This work utilized the ergodic character of classical MD simulations; that is, thermodynamic properties are statistically reflected by sufficiently long simulations, which, in this case, was 10 μs total. All simulations were performed with a 4 nm cuboctahedron CdSe core. The inorganic atoms are modeled with Lennard-Jones (LJ) potentials and, thus, are allowed to diffuse on the surface. Relaxed NC-ligand structures were obtained from initial configurations where NC and OA- were uncorrelated (Fig. 3a). By performing a statistical analysis on an ensemble of configurations obtained from over 300 independent trials, a binding trend in (100) > (111) > (110) was found, and the preferred binding sites on each facet were identified. This work additionally complemented previous DFT investigations by providing statistics on binding modes other than the ground states, which substantially increased our understanding of how binding modes and configurations can be collectively influenced by affinity, local surface structure, and ligand density (Fig. 3b). Lastly, assuming irreversible adsorption of ligands, that each OA complexes with surface Cd ions, the mobility of ligands on surfaces was evaluated by recording the displacement of surface Cd ions. Despite the success of using a statistical approach to characterize ligand absorption, more information on the complexity of surfaces and ligands could be retrieved if FF other than simple pairwise LJ potential was used.

a Obtaining equilibrated OA-coated CdSe in solution (right) from initial configurations with uncorrelated ligands an NC. b Binding modes found in the MD simulation (left) with the observed occurrence (right). Reprinted with permission from ref. 69, Copyright 2023 Royal Society of Chemistry. c Binding free-energy profiles of amino acids on hydroxylated TiO2 and non-hydroxylated TiO2. Reprinted with permission from ref. 70, Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society. d The PMFs along the path of oriented attachment of two PVP-coated Ag nanoplates, with the solid line indicating attachment on the Ag(100) face and the dashed line indicating attachment on the Ag(111) side. Example configurations of attachment on the side along the path are shown. Reprinted with permission from ref. 85, Copyright 2020 Royal Society of Chemistry. e The multiscale workflow that obtains ligand corona structure from single ligand chemistry. Reprinted with permission from ref. 75, Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society. f The phase diagram predicted with demonstrative assembly patterns shown in the corresponding region. Reprinted with permission from AAAS, ref. 72.

When adsorbed, ligands are free to explore in a configuration space instead of staying still. Each configuration is observable at a weighted probability. If an MD simulation is run sufficiently long, where the desorbed state can also be proportionally sampled, the probabilities along the orthogonal distance between ligand and surface can be inverted to obtain the adsorption free-energy profile or binding free-energy profile. This profile depicts the effective potential, or PMF, between the ligand and the surface along the adsorption path, from which the binding affinity can be calculated77. Further, by correlating the trajectories at each orthogonal distance from the surface (i.e., the x-axis in Fig. 3c) and the relative free energy, we can unravel the complex adsorption mechanism at the molecular level. However, because desorption is a well-known rare event infrequently observed within a typical MD simulation time, enhanced sampling methods are necessary to be used with plain MD simulation to extract adsorption free-energy profiles.

Two commonly used methods in obtaining adsorption free-energy profiles are umbrella sampling and metadynamics (MetaD)78,79. MetaD is more popular for flexible molecules like oligomers and polypeptides80, largely owing to the availability of algorithms to accommodate the degree of freedom and enhance the sampling efficiency. For example, MetaD can be coupled with replica exchange to accelerate the convergence while exploring temperature dependence81. In parallel-bias MetaD, one can bias more than two collective variables, whose limit is often two for umbrella sampling and the original MetaD, to proportionally decrease the computational cost82.

Because of their success in similar systems like biomineralization and metal NC growth, MetaD holds great promise in studying ligand adsorption on semiconductor NCs, and we have started to see efforts in applying it. Sampath and coworkers used well-tempered MetaD (WT-MetaD)83 to reveal the influence of the surface chemistry of metal oxides on amino acid adsorption70. In aqueous solutions, TiO2 surfaces can be hydroxylated. Such surface modifications exert influence on peptide binding, but the origin is unknown. Using MD simulations with WT-MetaD, it was found that surface hydroxylation narrows the adsorption energy well for certain amino acids (e.g., ARG and LYS), not all (e.g., ASP), while maintaining the overall free energy difference (Fig. 3c). Although a sharp energy well stabilizes certain binding structures of single amino acids, it might weaken the overall adsorption free energy of a long-chain peptide, as the limited accessible states of an amino acid on a chain do not necessarily allow it to enter an energetically favored state (i.e., the energy well)77. A change in overall adsorption free energy not only thermodynamically affects surface passivation (i.e., shifts the Wulff shapes) but also alters ligand layer structures (i.e., regulates deposition kinetics), two main factors in controlled NC synthesis. In addition, through proper reweighting and clustering, one can use MetaD to find weighted configurations at each characteristic feature on the free energy profile, such as energy minima and barriers77,84. Therefore, the insights from free energy profiles obtained from MetaD can be very useful in framing the design principles for new, effective ligand structures.

On a larger scale, the effective potential between two coated particles determines the assembly mechanism and assembled structures. Here, the PMFs are better obtained via umbrella sampling due to its robustness and fine control over the collective variable, for example, the distance between the center of mass of two particles (Fig. 3d)85 In a multiscale framework, the effective potentials can be further fed into CG models, either CG MD or Monte Carlo (MC) simulations, to study assembly. Of course, not all information will be preserved during coarse-graining. This makes method selection particularly important since one needs to make sure that the method used can extract the key influencing factor within the scope of the study. By connecting molecular information obtained from atomistic MD simulations and outcomes from CG models that match experiments, simulation-guided inverse materials design can be rationally achieved27,86.

Alternatively, appropriate theory can be used when PMFs from MD simulation are unattainable due to technical difficulties, such as unrealistic computational cost or lack of FFs. With a standing position at a high packing density, surface-grafted ligands share similarities with polymer brushes87. Vo and coworkers developed a framework consisting of scaling theory, MC simulations, and particle-based simulations that predicted ligand corona around anisotropic nanoplates as a function of nonlinearity (i.e., linear OA vs. dendrimers)75. The scaling theory estimates the end-to-end distance R of grafted ligands from structural parameters, such as the core size, grafting density, the excluded volume of ligands, the shape of the core, etc. The free energy of the ligand at different sites on an anisotropic NC can be written as a function of R, which is then used to find the probability of the ligand on that site. The effective ligand corona around the NC can be computed from MC simulations based on the site-specific probability, The averaged configurations showed a preferred packing in the center on larger facets for linear chains, and branched ligands favor smaller facets and vertices. The multiscale framework further spans assembly prediction. Here, a ligand-coated NC can be represented by rigid beads with site-specific PMFs. The effective potentials depend on grafting ligand density and are approximated by Lennard-Jones (LJ) potentials, with ε (i.e., interaction strength) in accordance with scaling theory. The predicted assembly matched well with those observed in experiments, again demonstrating the power of carefully built multiscale frameworks in gaining a fundamental understanding of convoluted systems. The method was later employed to construct phase diagrams to provide guidance for future experiments72.

A major drawback of classical MD simulations is the incapability of capturing bond breaking/forming and electron transfer (i.e., chemical reactions), the basis of many phenomena, including oriented attachment, growth, core-shell formation, etc. In principle, this can be resolved in AIMD, but it will require enormous computation power and human time. Reactive MD simulations find their perfect placement here by providing a middle ground between the two. When reactions are involved in the system of interest, one can choose to employ AIMD or reactive MD based on the system size, complexity, and availability of FFs. AIMD does not require interatomic interaction input and, thus, is suitable for chemically complex systems likely lacking FFs, such as perovskite66. Although reactive MD simulations usually suffer from non-trivial FF fitting, transferability issues, and unavoidable inaccuracy compared to ab initio methods, they can probe much larger time and length scales than AIMD, therefore, have demonstrated their usefulness and have gained much popularity. For example, ReaxFF has been applied to study the oriented attachment of TiO2 anatase nanocrystals and revealed a zipping mechanism induced by surface hydroxyl groups71. Although this example takes an extreme case on the ligand species (i.e., use deprotonated solvent molecules as capping ligands), it very well demonstrates the versatility of MD simulations. It has and, hopefully, will continue to inspire other works.

Demand of suitable force fields for solid-liquid interfaces

The discussions so far address two points of view: that ab initio methods accurately describe ligand binding but are often limited to small systems, and while large-scale simulation methods can be versatilely used to evaluate complex systems and understand the roles of ligands, the current volume of MD-based studies has been largely suppressed by a lack of FFs. Even in the successful MD examples listed above, one may argue that the quality could be improved or more insight could be obtained if higher-quality FFs were used. This is why this perspective focuses more on the methods they used instead of the underlying physics. Force fields are a critical piece of input that determines the quality, or even validity, of MD simulations88. Popular FFs need to balance accuracy, for obvious reasons, and convenience, which means easy to use, being compatible with open-source simulation engines, and low computational cost. Most FFs are more or less non-transferrable across certain chemical groups. FF parameterization for complex systems can be very case-specific and not readily usable even for a slightly different system41,89; thus, the effort spent in training and the value of the work is sometimes underappreciated. However, to broaden the participation of computational approaches to study colloidal semiconductor NCs, this step cannot be skipped. In this section, we will list several current strategies in interfacial FF fitting, remind a few key factors we need to consider in this process, and look at the opportunity of machine learning to accelerate this process.

Depending on the types of scientific inquiries, FFs can be general, like DREIDING90 and UFF91, or specific, like CHARMM92 and AMBER93. With tolerable sacrifice on accuracy, general FFs can be highly transferrable and can be used in many generic cases. Other FFs are designed to attend to a high level of chemistry details in a specific molecular family by adding environment-specific functional forms, such as AMBER for proteins and nucleic acids. These FFs set the foundation for the popularity of MD simulations in organic, biological, and main-group chemistry.

Moving to solid-state materials with transition-metal elements needs to take extra care. In many cases, pairwise interactions, such as LJ, are insufficient to capture the complex interactions therein. A classic example is the embedded atom method (EAM) potential for metallic systems, which solves the strong many-body dependence of interatomic interactions by embedding a total electron density in the potential functional94,95,96,97,98. Pairwise LJ potentials sometimes cannot capture the DFT-validated facet-selectivity of ligands and has motivated works to develop semi-empirical FFs through creative routes, such as hybridizing and overlaying functions41,99,100. Drude oscillators and rigid-rod models were developed to accommodate instantaneous polarization, another important characteristic of metals due to induced charge101,102,103. These FFs reproduce quality bulk properties by training against DFT-obtained lattice parameters, defect energetics, elasticity, and other relative properties. If desired to be used to understand crystal growth, energetics on surface energy, adatom diffusion, and site adsorption need to be included in the training set104.

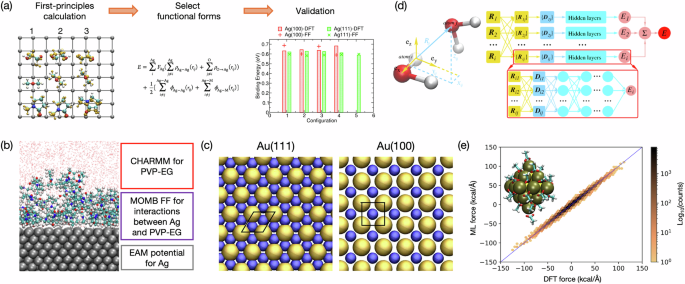

The interface between a solid-state material and an aqueous or organic solution connects intrinsically disparate chemicals and introduces challenges in simulation (e.g., simple mixing rules do not work between systems with different functional forms). These semi-empirical FFs are generally fitted against DFT-obtained adsorption configurations and energies. A brief illustration of the fitting process is depicted in Fig. 4a, and creative schemes are often adopted. For example, the MOMB FF takes a “sandwich” strategy, where multiple functional forms overlay only at the interface to match ligand adsorption assessed in DFT (Fig. 4b)41,89. At the same time, each phase is still described individually by the best FF for themselves(i.e., EAM for metals and CHARMM for the PVP-EG solution). In this way, the properties of individual phases are very well-preserved, making this FF appropriate for studying events like atom deposition and diffusion under the influence of ligands and solvents. Alternatively, GolP-CHARMM and AgP-CHARMM introduce virtual sites (i.e., the blue particles in Fig. 4c) on the metal surface to achieve DFT-quality adsorption energies of liquid-phase molecules on metals99,100. They showed that these virtual sites are necessary because simply summing up pairwise interaction between atoms cannot render the desired facet-selectivity and energetics. Similarly, adding additional functional forms in accordance with intermolecular interaction types identified in DFT has also been shown to be successful105. Note that interfacial FFs are nearly always trained against DFT data because experimental means with sufficient resolution are almost nonexistent. Nonetheless, experiments (e.g., dynamic force microscopy) are often employed to validate the MD studies by verifying key parameters, including binding energies106.

a A schematic workflow to fit first-principles-based semi-empirical FFs for organic-inorganic interactions at interfaces. Briefly, adsorption configurations and energetics are first optimized using first-principles DFT calculations. Then, proper functional forms are selected based on the types of interactions observed in first-principles methods, and sometimes, an overlay of multiple types of interactions is needed. The example here includes pairwise interactions between Ag atoms and organic atom types M and one-way electron-density function from an O atom to an Ag atom. Finally, validations are performed. Figures revised and reprinted with permission from ref. 136, Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society. b The illustration of how the hybridizing strategy in the MOMB FF is employed for a solid-liquid molecular interface. Reprinted with permission from ref. 31, Copyright 2017 Royal Society of Chemistry. c The GolP-CHARMM FF employs virtual sites (shown in blue) at specific locations between Au atoms (shown in golden) to achieve DFT-calculated adsorption energy of organic species. Reprinted with permission from ref. 99, Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society. d A schematic plot of a deep neural network model for MD simulations. Deep potential molecular dynamics (DPMD) employs a many-body-like strategy to characterize the local environment of an atom i, which serves as an input of a deep neural network to compute the energy Ei. Reprinted with permission from ref. 136, Copyright 2018 American Physical Society. e The configuration of acetate-coated PbS in MD with MLFF and the correlation between DFT and MD forces. Reprinted with permission from ref. 140, Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society.

The level of difficulty amplifies moving from metals to semiconductors. The variation in elements and bond types make the functional form selection step (i.e., the middle step in Fig. 4a) critical but, at the same time, utterly difficult. First of all, the involved elements in elemental and compound semiconductors widely span the periodic table. The variation in bonding challenges a universal approach in FF fitting. Also, for compound semiconductors, properties of both the pure forms of all composing elements and the compound should be preserved by a versatile FF, and the types of the bond may include metallic, covalent, and semimetallic107. Many functional forms other than two-body potentials have been explored to address this, including three-body potentials (e.g., Axilrod-Teller potential108,109), many-body potentials (e.g., MEAM potential)110, and bond-order-based potentials (e.g., Tersoff potential, Stillinger-Weber type, etc.)111,112. Force fields based on these approaches have been used extensively to study bulk (e.g., vibrational and elastic) and surface (e.g., adatom diffusion and surface reconstruction) properties and demonstrated robustness107,111,112. They serve as an excellent starting point for building accurate interfacial FFs to study the influences of ligands on surface thermodynamics and kinetics. Since these FFs adopt functional forms different from liquid-phase species (i.e., often pairwise), the aforementioned “sandwich” strategy, as in the MOMB FF, can be a suitable approach to fit interfacial interactions.

Hybridizing and overlaying FF undoubtedly result in MD simulations with high fidelity to DFT calculations; however, executing them is inevitably accompanied by increased computational demand. In some cases, simplified tools are more desirable if similar results are rendered at a much-reduced cost. Combinations of pairwise interactions, like LJ, Coulomb, and Buckingham potentials, have been used for bulk compound semiconductors and their interface with solutions113,114. For example, the MD simulation mentioned in the last section on CdSe QD was successfully conducted after a pairwise potential was developed115. Thanks to the simple form, some FFs are also compatible with other widely adopted FFs for solution-phase molecules, like CHARMM, via mixing rules116. Such user-friendly FFs certainly help MD gain popularity in computational studies on semiconductors117,118,119.

As mentioned in the previous section, reactions associated with growth, such as precursor reduction, can be modeled with reactive MD. ReaxFF has been one of the most successful reactive FFs for the range of systems it covers, including hydrocarbons, proteins, metals, metal oxides, etc120. Silicon was one of the first model systems in ReaxFF besides hydrocarbons121, followed by ZnO, TiO2, perovskite, etc122,123,124,125,126,127. ReaxFF that describes elements involved in other common compound semiconductors has been recently developed (e.g., trimethylgallium and trimethylindium)128. In addition, the late advancement of eReaxFF expanded its applications in explicit electron transfer, further reinforcing its future role in modeling semiconductors and ligands129.

Since the introduction of the Behler-Parinello neural network in 2007, machine learning force fields (MLFFs) have drawn enormous attention in the field as a new way to model dynamic systems with the highest level of ab initio accuracy130,131. While still being mostly compared to AIMD, they are believed to have unlimited potential in large-scale simulations. The current development of MLFF is so fast-paced that validations by users in the field cannot catch the speed of new MLFF generation. Thus, we have not reached a consensus on what MLFF-system match is the best, in contrast to classical FF. Nevertheless, most MLFF are based on one of the two methodologies, namely kernel-based132,133,134,135 and artificial neural networks136,137,138. The review by Unke et al. provides a comprehensive discussion about the foundations and should be referred to for further interest131. In short, successful applications of MLFFs in solid-state systems are not rare, but mostly for bulks139. Like classical FFs, interfaces are still challenging but not impossible137. Below, we list a few that are highly relevant to or promising for semiconductors and ligands.

In the most directly related example, Sowa and coworkers140 developed an MLFF for acetate adsorption on a PbS octahedron using the DeepMD package140,141. The DeePMD-kit, developed based on the originally introduced deep potential molecular dynamics (DPMD), is a neural network-based MLFF that shares the basic training scheme as shown in Fig. 4d. The MLFF from Sowa and coworkers was trained against DFT data and reproduced forces in high agreement with those obtained from DFT (Fig. 4e). The total simulation time in MD based on the MLFF reached an order of 10 ns, far exceeding the ordinary timescale in AIMD (on the order of 10−3 ns). Another neural network MLFF, Allegro138, has gained much attention since its debut and is believed promising in interfacial applications, such as heterogeneous catalysis142. On the other hand, kernel-based MLFFs stand out as they demand much less training data from DFT than neural network MLFF and are great for inverse design131,139. They can even be coupled with active learning to further accelerate the training process135. The most recent breakthrough is reactive MLFF for condensed-phase chemistry143. As an initial effort, the workflow was only applied to hydrocarbons, like ReaxFF in the early 2000s. Still, it serves as a remarkable step in expanding the versatility of MLFFs. Last but not least, smartly combining MLFFs and traditional FFs may be a solution for an optimized balance of accuracy and speed144. A proof-of-concept study was performed on a metal-organic framework (MOF) to investigate diffusion and adsorption. The idea is very similar to that of the MOMB FF, where the MOF was described using DeepMD, adsorbates were described in classical FF, and the adsorbate-adsorbent interactions were also obtained from classical FF via mixing rules. The validation of the hybridizing idea is inspiring and encourages other creative and effective approaches in the future.

Outlook

In summary, this perspective highlights the recent progress of computational approaches in understanding the roles of ligands in semiconductor NCs. Multiscale simulation frameworks have been demonstrated to be particularly useful in gaining physical insights as they bridge molecular-level driving forces to macroscopic-level observations. Regardless of the methodologies chosen to build the multiscale framework, being able to successfully model the NC-ligand-solvent systems in silico is a pre-requisite. We have reviewed works using ab initio methods, MD, and theory and identified scenarios when each method is suitable (Table 1). The most noticeable part of computational studies for semiconductor systems is the low volume of MD works compared to DFT, which is far lower than other systems, such as macromolecules and even metals. We argue that the limiting factor is FFs. Therefore, we enumerated a few available FFs for semiconductors and ligands and suggested FF fitting ideas inspired by other similar systems. After overcoming technical difficulties, more attention should be directed to designing systematic approaches to study the role of ligands145. The idea is not limited to multiscale theoretical frameworks; data science and artificial intelligence should be used synergistically to achieve computation-guided inverse design for functional semiconductor nanomaterials.

The focus of this perspective mainly addresses organic ligands in controlled NC growth and assembly. Ligands are way more diverse and versatile than this. In fact, many new properties were found to be dependent on ligand chemistry. Ligand exchange to displace OA is an important step in enabling these new functions. Moreover, large proteins, or even microorganisms, have also been combined with semiconductor NC for photosynthesis or biocatalysis. Considering the relevant scales, these examples encourage more MD simulations, both at atomistic and CG levels, in future computational studies for semiconductors, another motivation to devote effort to FF development to close the gap between quantum mechanics and molecular dynamics.

Responses