Optimizing rabies mRNA vaccine efficacy via RABV-G structural domain screening and heterologous prime-boost immunization

Introduction

Rabies is a zoonotic disease that is caused by the rabies virus (RABV), a member of the genus Lyssavirus in the Rhabdoviridae family1,2. After infection, RABV mainly destroys the central nervous system in humans or animals and has a lethality rate of almost 100%3. RABV is an RNA virus that consists of a single-stranded negative-sense RNA, a protein capsid, and an envelope4,5. The genome of RABV encodes five major proteins: nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P), matrix protein (M), glycoprotein (G), and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp, L)6. As the only glycoprotein located on the viral envelope, RABV-G exerts a very important role in virus-host cell binding and infection. RABV-G interacts with receptors on the host cell surface, such as neural cell adhesion molecules or low-affinity nerve growth factor receptors (p75NTR), which facilitate RABV uptake and spread throughout the nervous system7,8,9,10. RABV-G is a major target of neutralizing antibodies and vaccine development11,12, which contains cytoplasmic domain (CD), transmembrane domain (TD), and ectodomain (ED). Previous studies have revealed the importance of TD in the maintenance of protein conformation and induction of neutralizing antibody. However, the role of the CD in protein immunogenicity and vaccine protection efficiency still remains unclear.

Although rabies is incurable, vaccine provides an effective strategy for this disease. As rabies virus usually remains in the infected area for weeks or months before spreading to the central nervous system, pre- or promptly post-exposure immunization will prevent the spread of rabies virus13. The first-generation rabies vaccines were derived from virus-infected brain neural or embryonic tissues through inactivation of the rabies virus via physical or chemical methods14,15. Due to insufficient safety, efficiency, and immunogenicity, these tissue-based vaccines have been suspended from use worldwide. Subsequently, the creation of cell culture systems for virus propagation has led to the second-generation cell culture-based rabies vaccines. Fixed rabies virus strains were propagated in cell culture systems (e.g., human diploid cells, Vero cells, and chick embryo cells) and then were inactivated using β-propiolactone or binary ethylenimine to eliminate infectivity while retaining antigenicity15. They are highly safe, avoiding the risks of residual virulence in live attenuated vaccines, and have proven effective in inducing durable neutralizing antibody responses. Currently, several culture-based rabies inactivated vaccines are available on the market, such as Sanofi’s Imovax® Rabies and GSK’s RabAvert®, which play a vital role in rabies prevention for both humans and pets. However, these vaccines are relatively expensive due to the complexity of production and typically require multiple doses to establish and maintain immunity13,16,17. Live attenuated vaccines could provide a long-lasting protection by one single dose, but some safety concerns, like possibility of reverting to pathogenic virus and potential interactions with other biological components limit its uses16,17. Therefore, it is greatly needed to develop a safe and cost-effective rabies vaccine that induce a long-lasting protective immunity with less inoculations. With the advancement of genetic and molecular technologies, various rabies vaccine platforms have been developed, including protein vaccines, genetically modified vaccines, recombinant rabies vaccines, viral vector-based vaccines and nucleic acid-based vaccines. For protein vaccines, RABV-G protein or its antigenic epitopes have been expressed in different recombinant systems, including recombinant bacteria, yeast, insect cells, or mammalian cells18. However, these vaccines were usually ineffective, primarily due to the misfolding of the RABV-G protein. It is well known that its native trimeric form is essential for inducing neutralizing antibodies19. Genetically modified vaccines are generated through genetic modification of the rabies viral genome, such as insert/deletion mutation, substitute mutation and so on. For example, RVG strain with mutations at positions 194 and 333 has been shown to be non-pathogenic, highly safe and highly efficient in protection against rabies virus challenge20. Recombinant rabies vaccines are developed by editing the rabies virus genome to encode two or more copies of the glycoprotein or using strategies to clone and express only RABV-G21,22. The previous studies reported that recombinant rabies virus with two copies of the glycoprotein gene demonstrated improved immunogenicity, higher viral neutralizing antibody levels, and reduced pathogenicity in mice and dogs, showing protection against the virulent CVS-11 strain23,24. The viral vector-based vaccines, which utilize modified non-rabies viruses to deliver rabies antigens, have become a promising platform for oral vaccinations in wild animals25. Currently, two viral vector-based vaccines, RABORAL V-RG (cowpox virus vector) and ONRAB (adenovirus vector), have been licensed and play a significant role in controlling rabies in wildlife26. The nucleic acid-based vaccines can be classified into DNA-based and RNA-based vaccines. DNA or mRNA used in these vaccines encodes antigen protein in cells, where the host machinery facilitates endogenous protein synthesis, mimicking a natural infection and triggering both cellular and humoral immune responses against the target antigen. Researchers have demonstrated the immune and protection efficiencies of DNA vaccine for rabies virus in mice. In addition, other studies report that mutation at amino acid residue 333 from arginine to glutamine (R333Q) would reduce viral pathogenicity and promote the protection efficiency of rabies DNA vaccine efficiency27,28. Although DNA vaccines have proven to be effective, their widespread application, particularly in post-exposure prophylaxis, remains limited due to their slow and low immune response.

mRNA technology, accompanied by the introduction of modified nucleotides and lipid nanoparticle (LNP) carriers, has been rapidly advancing in the field of vaccines against tumors and infectious diseases29,30. The success of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines Comirnaty (BNT162b2) and Spikevax (mRNA-1273) confirmed their great value in disease prevention31,32. In addition, other mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases such as influenza, herpes zoster, etc. are being investigated in many clinical trials33. The success of mRNA vaccines may be partly owing to the fact that mRNA vaccines, as a genetic drug, do not introduce any viral components into their preparation and production, and therefore avoid the safety risk of pathogenicity reversion and toxicity caused by host cell components34. In addition, mRNA vaccines can induce strong and balanced humoral and cellular immune responses, ensuring their effectiveness in anti-tumor and anti-viral applications35. From a manufacturing perspective, short design and production cycles and low-cost also endow mRNA vaccines great advantages36. Currently, there are several preclinical studies have demonstrated the rabies mRNA vaccines could induce the production of neutralizing antibodies and provide protection against rabies virus in multiple animal models, including dogs, pigs, rats and monkeys37.

A heterologous prime-boost immunization strategy, in which different vaccine platforms or antigen sequences were immunized sequentially, have been widely used for vaccine development. Previous studies have demonstrated that heterologous prime-boost immunization could promote vaccine immunogenicity, induce a broader spectrum of antibody and cellular responses, and improve protection efficiency against influenza, COVID-19, varicella-zoster virus, foot-and-mouth disease and so on38,39,40,41,42,43. With the outbreak of COVID-19, various vaccine types against this virus have been developed, including protein subunit vaccine, mRNA vaccine, inactivated virus vaccine and adenovirus vaccine. Heterologous immunization combinations of these vaccines are of great significance in practical application. For example, Zhang et al. demonstrated that ‘protein subunit vaccine prime and mRNA vaccine boost’ or a mixed formulation of both significantly enhanced the neutralizing antibody response against different COVID-19 strains42. Currently, there are no studies on the heterologous prime-boost immunization strategies for rabies virus.

In this study, we first investigated the optimal RABV-G mRNA sequence by constructing a series of C-terminally truncated RABV-G mRNA and assessing their immunogenicity and protection efficiencies. In addition, a R333Q mutation was also introduced into RABV-G mRNA to evaluate whether it could promote vaccine efficacy. Thereafter, a homologous or heterologous immunization with RABV-G mRNA vaccine and inactivated rabies virus (IRV) was performed to optimize the vaccination strategy.

Results

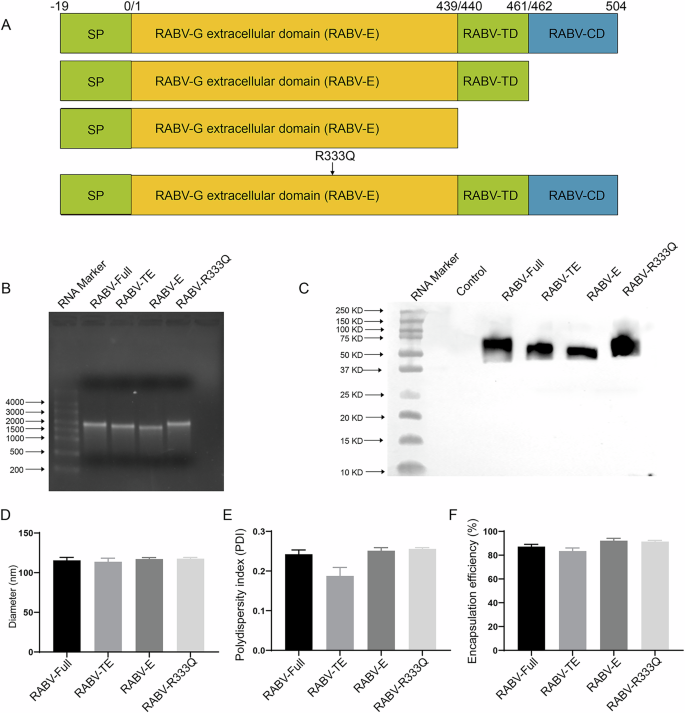

RABV-G mRNA encoding different structure domains were efficiently encapsulated into LNPs

The length of mRNA antigens encoding RABV-G full length (RABV-Full), ectodomain-transmembrane (RABV-TE) domain, ectodomain domain (RABV-E) or RABV-R333Q (Fig. 1A) were synthesized and characterized using an agarose gel electrophoresis. As shown in Fig. 1B, all mRNAs were located at 1500 bp–2000 bp and the lengths were as RABV-Full=RABV-R333Q > RABV-TE > RABV-E in order of size. The raw scan of agarose gel of mRNAs was showed in supplementary Fig. 1. The protein expression of all mRNAs was shown in Fig. 1C, which indicated that protein bands of RABV-Full and RABV-R333Q were higher than those of RABV-TE and RABV-E (Fig. 1C). The raw scan of western blot was shown in supplementary Fig. 2. Then these mRNAs were encapsulated into LNPs using a microfluidics approach, respectively. The sizes of LNPs encapsulating RABV-Full, RABV-TE, RABV-E and RABV-R333Q were 115.57 ± 3.79 nm,113.77 ± 4.53 nm, 117.17 ± 1.89 nm, and 117.7 ± 1.61 nm, respectively (Fig. 1D). All of the polydispersity indices (PDIs), which represented the uniformity of particle size, were lower than 0.3 (0.242 for RABV-Full, 0.188 for RABV-TE, 0.251 for RABV-E, and 0.256 for RABV-R333Q) (Fig. 1E). The encapsulation efficiency of all mRNAs was higher than 80% (Fig. 1F).

A Domain structure of full-length G protein: ectodomain was colored with yellow, TD colored with orange represented transmembrane domain and CD colored with green represented cytoplasmic domain. B Agarose gel electrophoresis showing the lengths of mRNA vaccines encoding different structural domains of RABV-G. C HEK293T cells were transfected with mRNA vaccines encoding different structural domains of RABV-G and protein expression was confirmed by western blot with a rabies virus glycoprotein polyclonal antibody (PA5-117507, Invitrogen, USA). D, E Size distribution and PDIs of LNPs encapsulating mRNA vaccines measured. F Encapsulation efficiency of mRNA vaccines in LNPs.

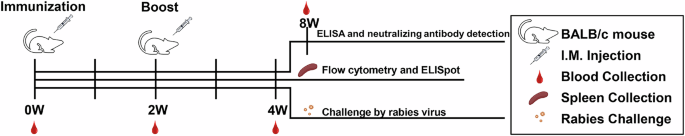

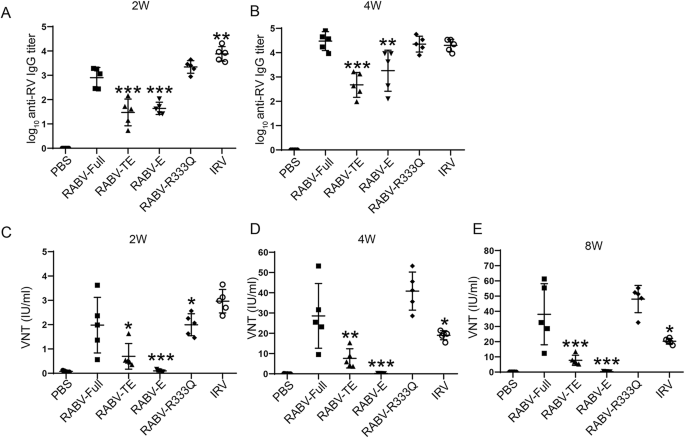

The binding and neutralizing antibody levels induced by rabies mRNA vaccine

To evaluate the effect of different structural domains on vaccine immunogenicity, mice were immunized intramuscularly with RABV-Full, RABV-TE, RABV-E, and RABV-R333Q at a dose of 5 μg. The experiment procedure for animal study was shown in Fig. 2. The binding antibody was detected using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). As shown in Fig. 3A, RABV-Full and RABV-R333Q groups induced lower IgG levels than IRV group 2 weeks after prime inoculation. The truncated mRNA vaccines, including RABV-TE and RABV-E, induced significant lower levels than others. After boosting, all groups showed increased antigen-specific antibody levels (Fig. 3B). RABV-Full and RABV-R333Q groups showed comparable antibody levels to IRV group, followed by RABV-TE and RABV-E groups. Virus-neutralizing titers (VNTs), determined by rapid fluorescent focus inhibition test (RFFIT) assay, is the gold standard for evaluating vaccine-induced protection against rabies virus. Similar tends were found between antigen-specific antibody levels and neutralizing antibody levels, except that IRV group showed lower neutralizing antibody levels than RABV-Full and RABV-R333Q groups at 2 and 6 weeks after booster shot (Fig. 3C–E). Notably, RABV-R333Q induced a higher VNTs than RABV-Full, although there was no significant difference (P > 0.05). The VNTs of RABV-TE was significantly lower than that of RABV-Full and RABV-R333Q (P < 0.05), while RABV-E group inoculated with mRNA encoding only extracellular structural domain, had almost no neutralizing antibody.

Mice were vaccinated twice (days 0 and 14) with 5 μg RABV-G mRNA, 1/10 human dose IRV, or PBS. The immune responses and protection efficiencies of mRNA vaccines were evaluated.

Mice were vaccinated twice (days 0 and 14) with 5 μg RABV-G mRNA, 0.1 human dose IRV or PBS. The blood was obtained from mice. A, B ELISA results showing binding antibody levels in immunized mice at Week 4 after first immunization. C–E RFFIT assay results demonstrating neutralizing antibody levels induced by rabies mRNA vaccine at Week 2, Week 4, and Week 8 after the first immunization. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 represent comparison with RABV-Full group.

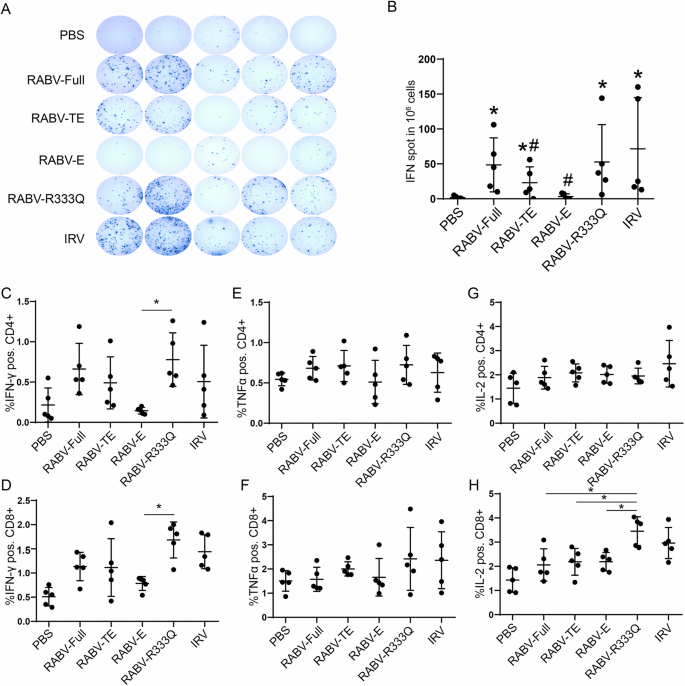

The cellular immune response induced by rabies mRNA vaccine

Although cellular immune response do not prevent initial viral infection of cells, animal experiments have revealed that it is important for rabies virus clearance in mice44. Furthermore, rabies-specific T cell clones were also detected in vaccinated individuals45. Thus, we compared the cellular immune response induced by different rabies mRNA vaccines. Two weeks after boost immunization, cellular immune response was evaluated using ELISpot assay. In rabies mRNA vaccines with different sequence designs, RABV-Full and RABV-R333Q produced the most IFN-γ-producing splenocytes (48.6 spots per 106 splenocytes for RABV-Full and 52 spots for RABV-R333Q), followed by RABV-TE (23 spots) and RABV-E (4.8 spots) (Fig. 4A, B). The frequencies of antigen-specific IFN-γ, TNFα or IL-2 positive CD4+ and CD8 + T cells were measured using flow cytometry. The results in Fig. 4C, D suggested that RABV-Full and RABV-TE induced a comparable level IFN-γ positive CD4+ and CD8 + T cells, which exceeded levels induced by RABV-E group, but was lower than that in RABV-R333Q group. Furthermore, RABV-E exhibited a significant reduction in IFN-γ positive CD4+ and CD8 + T cells compared with RABV-R333Q group. However, the frequencies of TNFα positive T cells and IL-2 positive CD4 + T cells exhibited no obvious differences among all groups (Fig. 4E–H). Except, for IL-2 positive CD8 + T cells, RABV-R333Q group exhibited a significantly higher frequency than other three mRNA vaccines (Fig. 4H).

Mice were vaccinated twice (days 0 and 14) with 5 μg RABV-G mRNA, 0.1 human dose IRV or PBS with equal volume. In Week 2, after the second immunization, mice were executed, and splenocytes were collected. After being stimulated by the inactivated rabies vaccine (1:100 dilution), activated T cells in splenocytes were analyzed using ELISpot and flow cytometry. A Representative pictures of ELISpot. B Number of IFN-γ-producing splenocytes in response to protein stimulation in different vaccine groups. *P < 0.05 represent comparison with PBS group. #P < 0.05 represented comparison with RABV-Full. C, D Frequencies of IFN-γ positive CD4+ and CD8 + T cells. E, F Frequencies of TNFα positive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. G, H Frequencies of IL-2 positive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. *P < 0.05.

In summary, these results implied that RABV-R333Q and RABV-Full induced a comparable cellular immune response, which was higher than both truncated mRNA vaccines (RABV-TE and RABV-E). Statistically significant differences were not found between them due to high intra-group variability.

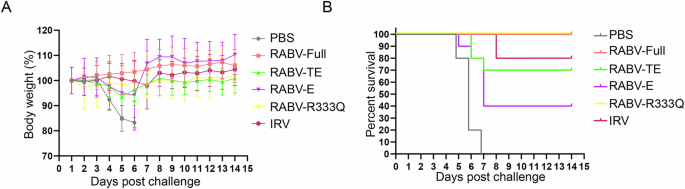

Comparison of protection efficiencies induced by rabies mRNA vaccine with different structural domains or R333Q mutation

In order to evaluate the vaccine efficiency in protecting mice from virus infection, mice were randomly assigned to six groups, each consisting of 10 mice. After vaccination, they were challenged by intracerebral injection with CVS (20LD50 per 0.03 ml), and were observed for two weeks. All mice survived the first 4 days after challenge. As shown in Fig. 5A, B, RABV-R333Q and RABV-Full provided an optimal protection against rabies virus. The survival rates of mice for both groups were 100% (10/10) and body weight exhibited no loss in two weeks. The survival rate of RABV-TE group was 70% (7/10) and body weight also exhibited a significant loss in experiment process, which suggested that RABV-TE provided a lower protection for rabies virus than RABV-R333Q and RABV-Full groups. The final survival rate of IRV vaccine was 80% (8/10). Finally, rabies mRNA vaccine with only extracellular structural domain could not provide effective protection for rabies virus infection, with a final survival rate of 40% (4/10).

A Body weight, B survival rates of immunized mice challenged with lethal rabies virus infection.

In summary, RABV-R333Q and RABV-Full conferred mice complete protection against the rabies virus, which was better than truncated mRNA vaccines (RABV-TE and RABV-E).

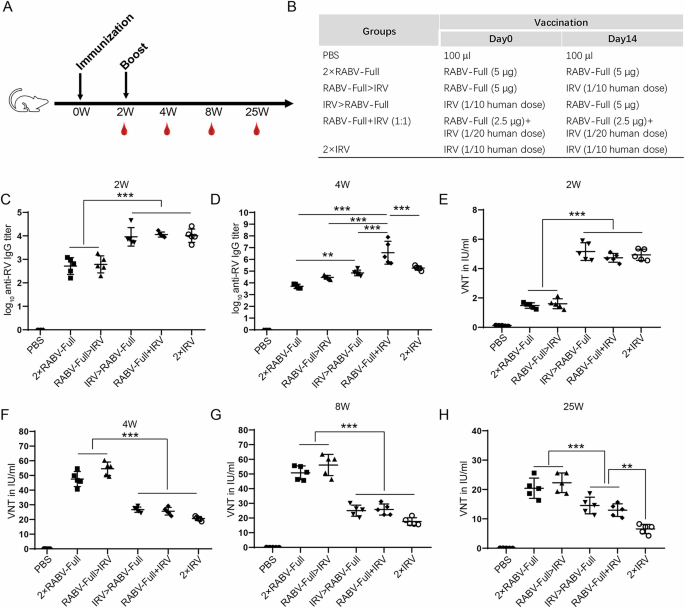

The immune evaluation for heterologous prime-boost immunization with RABV-Full and IRV

In the immune evaluation of rabies mRNA vaccine, we noticed that although mRNA vaccine produced high levels of VNTs after the second immunization, the early antibody levels at the first immunization were lower than those of the IRV at 1/20 human dose. Therefore, we wondered whether combined immunizations with RABV-Full and IRV could improve the early and long-lasting neutralizing antibody levels of rabies vaccines. The immunization procedure was shown in Fig. 6A, B. We found that the immune response induced by IRV (1/20 human dose) was too low compared to the mRNA vaccine. Therefore, the immunized dose of IRV was adjusted to 1/10 human dose. As shown in Figs 6C, 2 × IRV, IRV > RABV-Full, and RABV-Full+IRV induced comparable binding antibody levels, which are significantly higher than those of RABV-Full>IRV and 2 × RABV-Full mRNA vaccines at two weeks after prime immunization. After boost immunization, all groups showed increased antigen-specific antibody levels. Interestingly, RABV-Full+IRV elicited the highest binding antibody titer among all groups (Fig. 6D).

A, B Schematic representation of the immunization procedures. C, D Binding antibody titers measured 2 weeks after the first immunization and second immunization. E–H Neutralizing antibody activity (VNTs) was measured at various time points. *P < 0.05.

As for neutralizing antibody, 2 × IRV, IRV > RABV-Full, and RABV-Full+IRV induced comparable VNTs, which are significantly higher than those of RABV-Full>IRV and 2 × RABV-Full at 2 weeks after prime immunization (Fig. 6E). However, 2 weeks after boost immunization, mRNA-primed immunization regimen (2 × RABV-Full and RABV-Full>IRV) induced a higher VNTs than IRV-primed regimen (IRV > RABV-Full and 2 × IRV) or mixed formulation (RABV-Full+IRV, Fig. 6F). Similar phenomena remained at 6 and 23 weeks after boost inoculation (Fig. 6G, H). It was worth noting that, 25 weeks after boost immunization, VNTs of IRV > RABV-Full or RABV-Full+IRV group maintained higher VNTs than 2 × IRV group (Fig. 6H). The differences between IRV > RABV-Full (or RABV-Full+IRV) and 2 × IRV might be also affected by the dose of RABV-Full or IRV, which require further investigation.

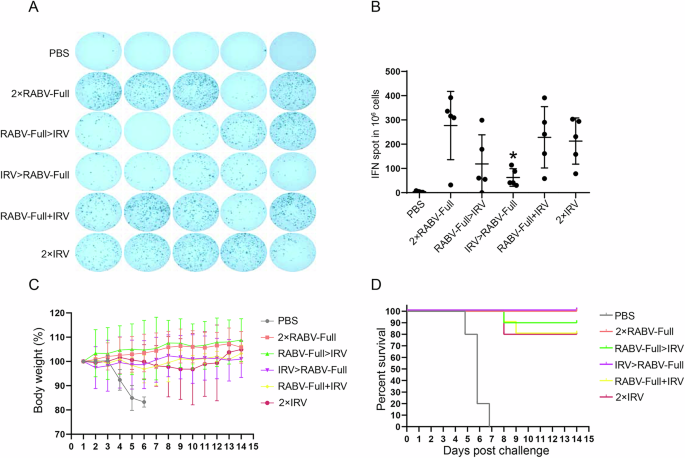

ELISpot results showed that the frequency of IFN-γ+ splenocyte cells in IRV > RABV-Full group was significantly lower than those in RABV-Full>IRV, 2 × RABV-Full and 2 × IRV groups. Notably, RABV-Full+IRV group showed comparable IFN-γ+ splenocyte frequency to that of 2 × IRV group (Fig. 7A, B). The protection efficiency of different immunization regimens was evaluated using an intracerebral virus challenge test for each group (n = 10). All mice survived the first 4 days after challenge. As shown in Fig. 7C, D, 2 × RABV-Full and IRV > RABV-Full provided a 100% (10/10) protection for virus-infected mice. The survival rates of RABV-Full>IRV, RABV-Full+IRV and 2 × IRV were respectively 90% (9/10), 80% (8/10) and 80% (8/10). The results suggested that IRV > RABV-Full provided a better protection for RABV-Full>IRV or RABV-Full+IRV.

A, B ELISpot analysis of IFN-γ-producing splenocytes. *P < 0.05 represented comparison with RABV-Full. *P < 0.05 represented comparison with RABV-Full. C, D Body weight and survival rates of immunized mice challenged with lethal rabies virus infection.

In summary, our results suggested that IRV > RABV-Full or mixed formulation triggered a higher short-term antibody level (week 2 after primary inoculation), while mRNA-primed regimens (2×RABV-Full and RABV-Full>IRV) had a higher neutralizing antibody levels after boost vaccination. The protection efficiency of IRV > RABV-Full was higher than RABV-Full>IRV.

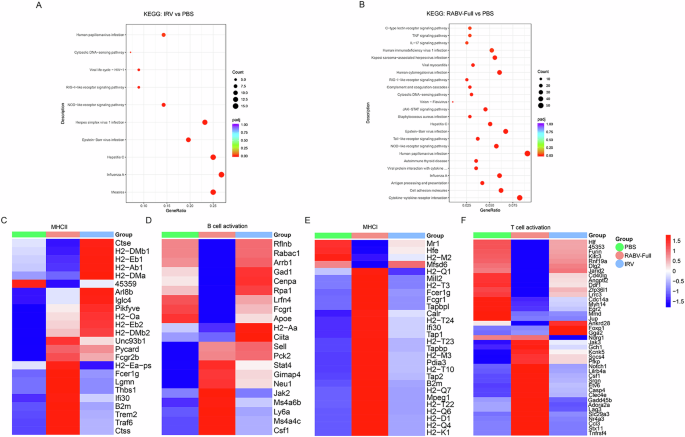

The transcriptomic analysis of rabies mRNA vaccine and IRV

The speed and magnitude of immune responses induced by vaccines are associated with the upregulation or downregulation of various immune-related signaling pathways. To better evaluate the impact of mRNA vaccines and IRV on the immune microenvironment of mice, we conducted transcriptome analysis on lymph nodes collected 24 h post-immunization. As illustrated in Fig. 8A, B, KEGG analysis revealed that the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the IRV group were primarily enriched in viral infection and innate immune response pathways, such as the RIG-1 receptor signaling pathway, NOD-1 receptor signaling pathway, and cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway. In contrast, DEGs in response to the mRNA vaccine were enriched not only in viral infection and innate immune responses (RIG-1, NOD-1) but also in cell adhesion, antigen processing and presentation, cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, TNF signaling pathway, and IL-17 signaling pathway. These results suggested that rabies mRNA vaccine could activate immune-related signaling pathways at the lymph node site more strongly compared to IRV. Further analysis focused on the expression of genes involved in antigen presentation and B/T cell activation, which were associated with vaccine-induced cellular and humoral immune responses. Notably, as shown in Fig. 8C–F, the IRV predominantly activates humoral immunity through the classical MHCII pathway and B cell activation. Key genes such as H2-Ab1, H2-Eb1, H2-DMa, Ciita, and Apoe are upregulated, enhancing antigen presentation and promoting B cell proliferation and antibody secretion. In contrast, the mRNA rabies vaccine not only activates MHCII-related genes like Ctss, Traf6, and Trem2 but also induces genes involved in antigen processing and immune regulation (Fcer1g, Pycard). Additionally, mRNA vaccines enhance metabolic adaptability in B cells (Pck2, Jak2), allowing for a more robust and efficient antibody response. While the IRV focuses on sustained classical humoral responses, the mRNA vaccine triggers a broader immune network. The mRNA rabies vaccine strongly stimulates cellular immunity by activating the MHC I pathway and promoting T cell activation. Genes such as Tap1, Tap2, H2-K1, and Calr are upregulated, enhancing intracellular antigen processing and presentation to cytotoxic T cells. Furthermore, T cell activation-related genes, including Tnfrsf4, Notch1, and Jak3, are highly expressed, leading to stronger effector and memory T cell responses. In contrast, the IRV shows limited activation of cellular immunity, with only a few regulatory genes (Foxp1, Ankrd28) expressed, primarily associated with T cell differentiation. This indicates that the mRNA vaccine provides a more comprehensive cellular immune response, critical for eliminating infected cells and establishing long-term immunity.

KEGG analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) was performed in A RABV-Full vs PBS and B IRV vs PBS. Heatmap analysis indicates the expression levels of genes involved in adaptive immunity, including C MHCII, D B-cell activation, E MHCI, and F T-cell activation.

Discussion

Rabies, caused by the rabies virus, remains a significant public health concern globally. At present, commercially available vaccines mainly include IRV, live attenuated vaccine, and virus-vectorized vaccine. The former can be used in both humans and animals, while the latter two can only be administered to domestic and wild animals. Although IRV has displayed acceptable efficacy in real-world applications, it usually requires multiple injections and results in low compliance and high costs. These factors limit its application to varying degrees, especially in less economically developed areas. In addition, residual host cell DNA has been an important safety concern in inactivated vaccine development. Many efforts have been made to reduce the pathogenicity of rabies virus vaccines and to increase their protective efficiency, such as genetically modified vaccines, recombinant rabies vaccines, and so on. For the recombinant rabies vaccines, cDNAs that contain two copy of RABV-G and other viral structural proteins were constructed and transfected into cells to acquire a rescued recombinant rabies virus21,46. The immunological assessment suggested that this vaccine has enhanced immunogenicity with higher viral neutralizing antibody production and decreased pathogenicity, which might be due to elevated G gene expression and inducing cell apoptosis of infected neuronal cells21,46. In contrast, in vitro transcribed mRNA-based rabies vaccine can not only avoid the above problems of safety and cost, but also has unique advantages in terms of product development cycle. Recently, few studies have investigated the potential of mRNA-based rabies vaccines in terms of production of neutralizing antibody and persistence in female BALB/c mice47,48. However, whether mRNA-based rabies vaccines could elicit fast, high and long-lasting neutralizing antibodies and therefore provide stronger protection when compared with traditional inactivated rabies vaccine remains unknown. In this study, we demonstrated that rabies mRNA vaccine with full-length could induce a potent humoral and cellular immune responses, providing a complete protection against lethal rabies virus. Several studies have investigated the application of mRNA vaccine in rabies prevention. For example, Bai et al. report that neutralizing antibody induced by a single RABV-G mRNA vaccination (1 μg or 3 μg) could last for 25 weeks and two-dose vaccination (10 μg + 1 μg or 10 μg + 10 μg) could extend the duration of neutralizing antibody to 1 year in female BALB/c mice47. Long et al. demonstrate that one single dose of rabies mRNA vaccine (20 μg) could induce an ≥100 IU neutralizing antibody in female BALB/c mice and this antibody titer could last for 240 days48. In the present study, our results suggested that two dose of rabies mRNA vaccine (5 μg) encoding the full length of RABV-G protein induced ~2 IU at 2 weeks after the first immunization and ~30 IU at two weeks after the secondary immunization. The two-dose vaccination (5 μg + 5 μg) could last at least for 25 weeks (~20 IU at 25 W). Overall, our mRNA vaccine had relatively low initial neutralizing antibody levels and a long duration than IRV. Although mRNA-based rabies vaccines have not been approved for marketing, several clinical trials are undergoing. mRNA sequence optimization has been utilized for improving the immunogenicity of rabies mRNA vaccines. For example, Cao et al.49 reported that the introduction of H270P mutation in rabies glycoprotein-encoding mRNA vaccine could induce stronger cellular and humoral immunity. This is because H270P stabilizes the pre-fusion conformation of rabies glycoprotein, which displays the major known neutralizing antibody epitopes49. RABV-G, as the major target for neutralizing antibodies and vaccine antigen, is a trimeric class III viral fusion protein that consist of cytoplasmic, transmembrane and ectodomains. Arginine at position 333 is important for the transmission and virulence of rabies virus in the nervous system. Mutations at this site, such as glutamine substitution, may reduce viral pathogenicity and lead to enhanced neutralizing antibody level and protection efficiency of DNA vaccine and inactivated rabies vaccine27,50. Here we demonstrated that R333Q mutation could increase the neutralizing antibody level of rabies mRNA vaccine, although the differences were not significant due to high within-group differences. The protection efficiencies of RABV-Full and RABV-R333Q were both 100%. For DNA vaccine, the intramuscular injection of pCDAG3-RABV-R333Q (100 μg) showed virus-neutralizing antibody induction by d30, and 100% protection efficiency. While DNA vaccine with unmodified G did not result in the production of detectable levels of virus-neutralizing antibody by d30 and the protection efficiency was 70%27. The lack of advantage of the R333Q mutation in mRNA vaccines compared to RABV-Full may be due to the fact that the immunological efficiency of the mRNA vaccine itself is already excellent. Koraka et al. constructed a trimeric RABV-G protein by combining a GCN4-based trimerization domain (GCN4-pII) with ectodomain. The immunization experiments demonstrated that trimeric RABV-G protein provided a performed superior to a predominantly monomeric form of RABV-G, suggesting that trimeric conformation is important for vaccine efficacy51. As TD is considered the main trimerization domain of RABV-G, we constructed a CD-truncated (RABV-TE) and a cytoplasmic/TD-truncated RABV-G (RABV-E) mRNA vaccine. The results demonstrated that although RABV-TE could induce neutralizing antibody and cellular immune response, they were significantly lower than those of RABV-G with full length. The protection experiments also demonstrated the superiority of RABV-G with full length to RABV-TE. A previous study reported that the CD of RABV-G is necessary for keeping the 1-30-44 epitope-positive mature form52. The researchers thought that 1-30-44 epitope might play an essential role in maintaining the strong immunogenicity of G proteins, because, among all 14 monoclonal antibodies, only mAb #1-30-44 can discriminate between authentic G proteins and non-immunogenic soluble G proteins52. It is worth noting that 1-30-44 epitope formation is independent of trimer formation, as the Triton-solubilized monomer form of G protein also has this epitope52. Therefore, we speculated that the deletion of CD led to defects in the 1-30-44 epitope, which reduces the level of neutralizing antibodies induced by mRNA vaccines. RABV-E induced a comparable binding antibody with RABV-TE, while neutralizing antibodies and cellular immune responses were almost absent. The results were consistent with previous adenoviruses or recombinant protein vaccines based on ectodomain of RABV-G53,54. It was worth noting that although the protein vaccine with only ectodomain of RABV-G was invalid in mice, it could induce a neutralizing antibody response in pigs54. This discrepancy may be associated with multiple factors, such as the instability of the RABV-G protein, variations in host responses, and variances in the adjuvant used54. Similarly, whether the RABV-E mRNA vaccine could induce neutralizing antibodies and provide protection in pigs or humans still remains unknown.

By searching the previous literature, we noticed that rabies mRNA vaccines prepared in different studies showed significant differences in neutralizing antibody levels47,48,55. At 2 W after immunization, rabies neutralizing antibody induced by 1 μg of mRNA vaccines ranges from 3.75 IU/ml to 68.78 IU/ml47,48,55. This difference in immunogenicity may be related to a variety of factors, such as optimization of mRNA sequences, modification of nucleotides, and lipid formulation. In the study reported by Qiao et al., three immunizations with 10 μg of rabies mRNA vaccine induced a 50 IU/ml of neutralizing antibodies at Day 35 after the first immunization, while it still resulted in >50% mortality in a post-exposure protection trial56. However, mRNA vaccine exhibited an excellent protection efficiency in pre-exposure immunization, with one dose of 1 μg or even 0.3 μg mRNA providing complete protection for challenged mice47,48. Here, we found that the rabies mRNA vaccine induced significantly higher VNTs after the secondary immunization. However, at 2 weeks after first immunization, the VNTs of IRV group (1/10 human dose) were significantly higher than that of mRNA vaccine group. We speculated that mRNA vaccine-induced immune responses require lysosomal escape and protein translation first, which leads to the possibility that antibody production, as well as viral neutralization, may take longer than with IRVs or protein subunit vaccine. Therefore, increasing the immunogenicity of mRNA vaccines, especially the short-term neutralizing antibody levels, is needed. In the current study, we attempted to combine the long-term protection capacity of mRNA vaccines with rapid antibody induction of IRV using a heterologous prime-boost immunization. The results showed that IRV > RABV-Full induced higher long-term VNTs than 2 × IRV and provided a better protection efficiency. Although the long-term VNTs of IRV > RABV-Full were lower than those of 2 × RABV-Full or RABV-Full>IRV, their short-term antibodies were significantly higher. Combining protection efficiency and short-term levels of VNTs, we think that IRV > RABV-Full is a superior immunization strategy to RABV-Full>IRV or RABV-Full+IRV. The transcriptomic analysis highlights the distinct immune responses induced by the rabies mRNA vaccine and IRV. While both vaccines activate innate immune pathways, including RIG-I and NOD-1 receptor signaling, the mRNA vaccine engages a broader range of pathways, such as antigen processing and presentation, cytokine interactions, and pro-inflammatory signaling, indicating a more diverse modulation of the immune microenvironment. IRV predominantly enhances humoral immunity through the classical MHCII pathway, upregulating genes like H2-Ab1 and Ciita, which promote B cell activation and antibody secretion. In contrast, the mRNA vaccine not only activates MHCII-related genes but also stimulates the MHC I pathway, significantly enhancing cytotoxic T cell activation via genes like Tap1 and H2-K1. Additionally, it improves B cell metabolic adaptability, supports robust antibody responses, and upregulates T cell activation-related genes such as Notch1 and Jak3, leading to stronger cellular immunity. This is in agreement with the previously published studies that mRNA vaccine induces both MHC I/II and B/T cell activation57,58. It is worth noting that SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine induces the expression of MHCI-related genes at 0–48 h, while genes encoding MHCII complex components are expressed mainly after 48 h in the dLNs. In the present study, our analysis was performed 24 h after inoculation. Therefore, we believe that conducting a kinetic transcriptomic analysis might provide deeper insights into the immune activation profiles of the rabies mRNA vaccine and IRV at different time points. In addition, the use of PBS as the control group may not reflect the activation of the immune system by rabies mRNA antigen due to the possible effect of LNPs. In future studies, non-functional scrambled mRNA-LNPs may be an ideal alternative as controls.

In conclusion, our results demonstrated that mRNA vaccines encoding the full length of RABV-G, either with or without the R333Q mutation, induced potent humoral and cellular immune responses, providing complete protection against lethal rabies virus challenge. Furthermore, our findings suggested that although the CD of RABV-G may not be indispensable for neutralizing antibody production, it played a crucial role in enhancing the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of the mRNA vaccine. Additionally, our study sheds light on the importance of structural domains in designing effective mRNA vaccines against rabies, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive understanding of antigen structure for optimal vaccine development.

Methods

mRNA synthesis and in vitro expression

The mRNA sequence of RABV-G was as described in a previous study59. A series of pET-28a (+) plasmids that harbored DNA sequences encoding full length of RABV-G protein (523 aa), protein without CD (1–480 aa), ectodomain (1–460 aa) or R333Q mutant were codon-optimized and synthesized with 5’, 3’ untranslated regions and 80-nt poly(A) tails (Nanjing Genscript Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China), respectively. For mRNA synthesis, DNA vectors were linearized and performed as a template for T7 polymerase transcription reaction by using a T7-FlashScribe™ Transcription Kit (Cat. No. C-ASF3507, Cellscript, USA). The UTP (uridine 5’-triphosphate) was replaced with N1-methylpseudouridine-5’-triphosphate (Cat. No. N-1081-5, Trilink, San Diego, CA) for mRNA modification. After DNA template was digested with DNase I interest mRNAs were purified using a MEGAclear transcription clean-up kit from Invitrogen. The capping reaction was performed using a ScriptCap™ Cap 1 Capping System (Cat. No. C-SCCS1710, Cellscript, USA). The length of RABV-G mRNA with different domains was characterized using a denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis.

The protein expressions of different mRNAs were detected using a western blot. In brief, HEK293T cells were planted into a 12-well plate at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well. After culturing for 24 h, 2 μg mRNA was transfected to cells in each well using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (L3000150, Invitrogen, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. After transfection for 48 h, cells were collected, lysed, and subjected to western blot analysis with RABV-G polyclonal antibody (PA5-117507, Invitrogen, USA).

Preparation of mRNA vaccines

The resultant mRNAs were encapsulated into LNP carriers using a modified method reported in the previous studies60,61. Briefly, RABV-G mRNAs of varying length and R333Q mutation were dissolved into a 100 mM citrate buffer (pH 4.0), respectively. The concentration of mRNA was adjusted to 0.17 μg/μl. A mixed lipid-ethanol solution containing SM-102, DSPC, cholesterol, and DMG-PEG2000 was prepared with a molar ratio of 50:10:38.5:1.5, with a total lipid concentration of 12.5 mM. SM-102 was purchased from AVT Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). DSPC, cholesterol, and DMG-PEG2000 were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). The mRNA-loaded LNPs were fabricated using a microfluidic mixer (Precision Nanosystems, Vancouver, BC, Canada). The volume of the mRNA solution and lipid mixture was set at a 3:1 ratio. After dialysis with PBS and concentration with Amicon ultra centrifugal filters (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), the resultant mRNA vaccines were stored at 4 °C until use. The size and zeta potential of mRNA-LNPs were detected using Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK). The encapsulated mRNA was analyzed using a Quant-iTTM RiboGreenR RNA Reagent Kit (Thermo Fisher, Eugene, OR, USA).

Animal studies

Thirty female BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks old, 15–18 g) were purchased from Liaoning Changsheng Biotechnology Co. Ltd (Liaoning, China). The mice were randomly divided into six groups (n = 5), including PBS group, 5 μg of RABV-G mRNA with full length (RABV-Full), 5 μg of RABV-G mRNA with cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains (RABV-TE), 5 μg of RABV-G mRNA with ectodomain (RABV-E), 5 μg of RABV-G mRNA with R333Q mutation (RABV-R333Q) and inactivated rabies vaccine (IRV) with a 1/20 human dose. The IRV was provided by Changchun BCHT Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Changchun, China). The potency of the vaccine was above 2.5 IU/ml. The animals were maintained at specific pathogen-free conditions with free access to food and water. Immunization was performed by intramuscular (i.m.) injection of mRNA-LNP vaccine (5 μg) or inactivated rabies vaccine at a volume of 100 μl. The prime and booster immunizations were performed at a 2-week interval. Blood samples were collected from immunized mice at 2, 4, and 8 weeks after prime immunization.

For heterologous prime-boost immunization, 30 female BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks old, 15–18 g) were randomly divided into six groups (n = 5): 1) PBS; 2) Two doses of RNA-Full (2 × RNA-Full); 3) RABV-Full prime and IRV boost (RNA-Full>IRV); 4) IRV prime and RABV-Full boost (IRV > RABV-Full); 5) RABV-Full+IRV (1:1); 6) Two doses of IRV (2 × IRV). The dose of RABV-Full was 5 μg, and IRV was at 1/10 human dose. For RABV-Full+IRV (1:1) group, RABV-Full (2.5 μg) and IRV (1/20 human dose) were mixed for immunization. The immunizations were performed twice at a two-week interval. Blood samples were collected from immunized mice at 2, 4, 8, and 25 weeks after prime immunization. Animal studies were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council), and all animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Animal Welfare and Research Ethics Committee at Jilin University (Ethical approval number 2022YNPZSY1007).

ELISA of antibody titers

The experiment procedure of ELISA was as described in previous studies62,63 The concentrated IRV solution was obtained from the aG strain64 of rabies virus grown in Vero cell culture. The titer of the virus collected was 108TCID50/ml. The virus was concentrated by ultrafiltration, inactivated with beta-propiolactone, and purified by column chromatography. The concentrated IRV solution was diluted in a Na2CO3-NaHCO3 buffer at 1:100 and added to a 96-well plate with a volume of 100 μl/well. Then, the 96-well plate was incubated at 4 °C for 12–16 h, followed by washing with 0.05% (v/v) polysorbate 20 in PBS (PBST) three times. After blocking with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h, the plates were incubated with a series of diluted serum samples for 1 h at 37 °C and washed with PBST three times. Then HR P-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG, IgG1, and IgG2c were added to 96-well plates and incubated for 1 h. After washed for another three times, TMB substrate (Solarbio, Beijing, China) was added at a volume of 50 μl/well and incubated for 25 min. OD values at 450 nm were measured by an ELISA plate reader (Gene Company, Beijing, China). The dilution factor and OD values were performed with a linear regression analysis. The antibody titer of each sample was defined as log10 of the highest serum dilutions, yielding a 2.1-fold OD value of negative controls.

Rapid fluorescent focus inhibition test

The rabies virus-neutralizing antibody levels of mouse serum were determined using RFFIT assay. In brief, BSR cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS, Thermo Fisher, Eugene, OR, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher). The tested mouse serum was heated at 56 °C for 30 min and three-fold serially diluted with DMEM containing 10% FCS (v/v) in a 96-well plate. The RABV strain CVS-11 (challenge virus standard-11) was provided by Changchun BCHT Biotechnology Co. Then challenge virus standard (CVS) was diluted to 4*107 FFU/ml with DMEM medium and then added into diluted serum at a volume of 100 μl/well. The serum-virus mixture was then incubated at 37 °C for 60 min. BSR cells were digested and added into the 96-well plate at a density of 5 × 104 per well. After culturing for 24 h, BSR cells were washed with PBS three times and fixed with 80% acetone solution. After washed with PBS for another three times, BSR cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-nucleoprotein antibody (1:200) for 60 min in the dark. The fluorescent foci observed in the microscope represented the residual rabies virus. The ratio of fluorescent foci to the area of whole wells was counted. The titers of rabies-neutralizing antibodies were calculated by the Reed and Muench method and expressed as international units per milliliter (IU/ml)62,65.

Enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISpot) of splenocytes

The spleens of immunized mice were collected at 2 weeks after boost immunization. Then spleens were ground on a 70 µm cell strainer (BD, USA) to prepare a monodispersed splenocyte solution. The cell solution was incubated with ammonium–chloride–potassium (ACK) lysis buffer for 5 min to remove red cells. After centrifugation at 300 g for 10 min, splenocytes were resuspended in a Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium with 10% FCS (v/v) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Thermo Fisher, USA). The cell density of splenocytes was determined using a cell counter and adjusted to 1 × 107 cells/ml. Then 100 μl of splenocytes were added into the 96-well plates of ELISpot assay kit (Cat. No. 3321-4HPW-10, Mabtech, Cincinnati, OH, USA) and incubated with inactivated rabies vaccine (1:100 dilution). After culture for 24 h at 37 °C, cells were processed as the protocols of ELISpot assay kit and IFNγ spots were visualized and counted in an ImmunoSpot S6 Universal Reader, CTL.

Intracellular cytokine staining

The activated T cells in spleens were detected using intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry. In brief, 1 × 106 splenocytes in 100 μl of RPMI 1640 (10% FCS) were stimulated with inactivated rabies vaccine (1:100 dilution) at 37 °C for 2 h, followed by incubation with protein transport inhibitor cocktail (500X, Cat. No. 00-4980-93, Thermo Fisher) for 6 h at 37 °C to block cytokine release. Then cells were incubated with Fc receptor blocking antibodies for 10 min at 4 °C and stained with anti-CD3-eFluor™ 506, anti-CD4-APC-eFluor™780 and anti-CD8-FITC for 30 min at 4 °C. For intracellular cytokine staining, splenocytes were fixed and permeabilized by using an intracellular Fixation & Permeabilization Buffer (Thermo Fisher). Then, cells were stained with eFluor 450-TNF, PE-IL-2, and APC-IFN-gamma for 30 min at room temperature and washed with permeabilization wash buffer. The proportion of activated T cells was analyzed using flow cytometry on a CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

Challenge infection

For sequence screening of rabies mRNA vaccine, female BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks old, 15–18 g) were randomly divided into six groups (n = 10). The mice were i.m. immunized with 100 μl of control buffer or vaccines, including PBS, 5 μg of RABV-Full, 5 μg of RABV-E, 5 μg of RABV-TE, 5 μg of RABV-R333Q and IRV with a 1/10 human dose. The immunizations were performed twice with a two-week interval. At two weeks after boosting immunization, the mice were injected with 25-fold 50% lethal dose (LD50) of CVS-11 intracerebrally. Animal survival and body weight were observed in the following 14 days. Mice that died on days 1–4 were excluded. For heterologous prime-boost immunization, female BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks old, 15–18 g) were randomly divided into six groups (n = 10), including PBS, 2 × RABV-Full (5 μg + 5 μg), RABV-Full>IRV (5 μg + 1/10 human dose), IRV > RABV-Full (1/10 human dose+5 μg), RABV-Full+IRV (2.5 μg/1/20 human dose+2.5 μg/1/20 human dose) and 2 × IRV (1/10 human dose+1/10 human dose). The immunizations were performed twice with a two-week internal. The challenge test was the same as above.

Lymphocyte isolation, RNA extraction, and transcriptome sequencing

C57BL/6 mice (n = 3 for each group) in PBS, RABV-Full, and IRV groups were euthanized by cervical dislocation at 24 h post-immunization. Bilateral inguinal draining lymph nodes (dLNs) were carefully dissected and immersed in PBS. The dLNs from each mouse were processed individually for RNA sequencing. To release the lymphocytes, the lymph nodes were gently squeezed using sterile techniques, and the cell suspension was filtered to eliminate debris and tissue fragments. The lymphocytes were then collected by centrifugation, resuspended in TRIzol reagent to stabilize the RNA, and counted to ensure a minimum of 1 × 106 cells for RNA extraction. Following this, RNA is extracted from the TRIzol-resuspended cell pellets according to the manufacturer’s protocol and analyzed qualitatively and quantitatively using a fragment analyzer. The quality-checked RNA is subsequently submitted for RNA-sequencing (RNA-Seq) using the DNBSEQ platform at BGI (Shenzhen, China), encompassing library preparation, sequencing, and raw data generation.

Transcriptomic analysis

Low-quality tags or sequences were removed from the raw sequencing data to guarantee the accuracy and reliability of subsequent analyses. The cleaned tags were then mapped to the reference genome of Mus musculus (NCBI: GCF_000001635.26_GRCm38.p6). Principal component analysis was performed on the mapped data to visualize and ensure the quality and reproducibility of the sequencing data. DEGs was analyzed using DESeq2, with |log2 (fold change)|>1, Padj value < 0.05. KEGG analysis was performed to investigate the biological processes of both mRNA vaccine and IRV. Expression levels of these genes, measured in fragments per kilobase of exon model per million mapped fragments, were normalized using z score transformation to generate heatmap figures, which visually represent the expression patterns of selected genes across different samples.

Statistics

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software. Comparisons between groups were performed with one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Responses