Optimizing the liver transplant candidate

Introduction

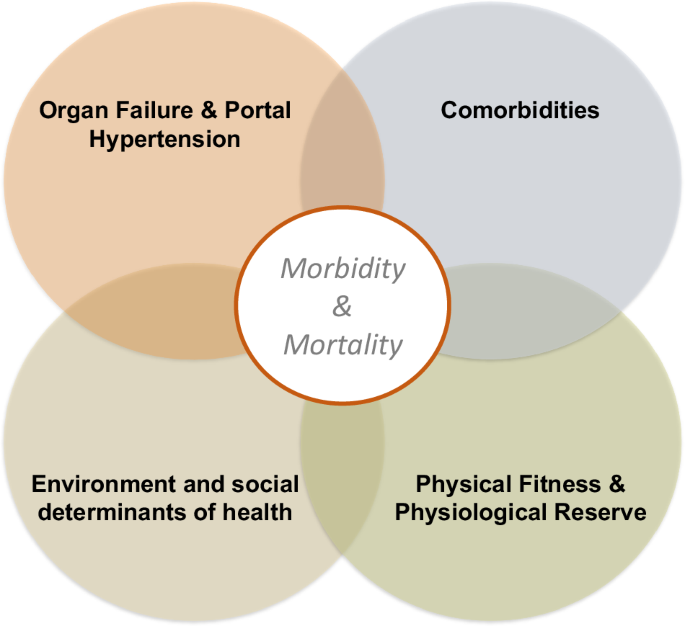

Liver transplant (LT) has forever changed the management of end-stage liver disease (ESLD)1,2. Advances in the care of ESLD and portal hypertension have allowed more patients to reach LT evaluation, and concomitant progress in transplant surgery now permits a growing proportion of potential candidates to undergo LT. However, LT candidates are becoming older and reaching transplantation with more severe comorbidities and at a lower physiological reserve, and since organ shortage is an unresolved problem, clinicians now face the utter need to orchestrate complex clinical care for sicker waitlisted candidates. These efforts require a multidisciplinary team to address a multifaceted care approach (Fig. 1). Using ESLD’s influencers of clinical course described herein, we provide a framework for optimizing the care of LT candidates to become successful organ recipients. We chose to use the term “influencers” rather than “determinants”, given that many of them are modifiable through healthcare and lifestyle interventions.

The multifaceted care approach aims to equally address a organ failure and the complications of portal hypertension; b relevant comorbidities affecting candidacy and posttransplant health; c environmental and social determinants of health; and d physical fitness or physiological reserve. Such comprehensive care is expected to improve overall health and translate into better quality of life and survival both pre- and posttransplant.

Organ failure and portal hypertension

Careful management of the complications of ESLD is essential to maximize the success of LT candidates. Complications of particular importance are hepatic encephalopathy, refractory ascites and its intimate link to renal function, as well as variceal hemorrhage.

Hepatic Encephalopathy (HE)

HE is one of the most debilitating complications of ESLD, manifesting as a broad spectrum of non-specific neurological and/or psychiatric abnormalities. High-grade HE is of particular interest as it results in hospitalization and can lead to severe complications (e.g., aspiration pneumonia) and death. Treatment for overt HE is summarized in Table 1. Lactulose is generally used as the initial treatment of HE and rather than a fixed dose, patients should be instructed to adjust as needed to target a bowel movement goal (2-3 per day) with extra doses to meet lucidity3. Bloating and abdominal distension limit tolerance and adherence. In such circumstances, polyethylene glycol can be used as a substitute as it comes with a better tolerated side effect profile and seems to be equally efficacious4,5. Rifaximin is routinely added to lactulose, though cost considerations can limit its use6. L-ornithine L-aspartate (LOLA), a mixture of two endogenous amino acids, is an agent that has shown favorable impact for the management of HE, however, lack of insurance coverage can limit its access in some countries7,8. Branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) are another therapeutic intervention infrequently explored, and it is particularly attractive for patients with sarcopenia9.

Special attention should be paid to recurrent (≥2 episodes in 6 months) or persistent HE (ongoing low-grade manifestations in between high-grade episodes), as these are the severest forms with highest mortality10. An additive pharmacologic strategy is necessary for these patients, where the laxative plus rifaximin base treatment is further supplemented with LOLA and/or BCAA, plus another agent; some patients need to be on three or four HE agents. The combination of BCAA with LOLA has the advantage of eliminating cataplerosis, a detrimental process negatively affecting the tricarboxylic cycle and energy formation through alpha-ketoglutarate consumption11. However, since spontaneous portosystemic shunts (SPSS) strongly associate with recurrent/persistent HE (present in 45–70% of patients), SPSS should be sought whenever precipitating factors for HE cannot be identified12 with triphasic cross-sectional imaging with attention to the portal phase. SPSS embolization results in clearance of HE for most cases, and although aggravation of portal hypertension is a concern (i.e., worsening ascites/bleeding), it is unlikely to be clinically meaningful13. In candidates with a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), a reduction in caliber is an essential part of their multidisciplinary management for recurrent/persistent HE. The improvement in cognition and self-efficacy following SPSS closure/TIPS caliber reduction allows waitlisted patients to stay out of the hospital and engage in other areas of self-care. Although fecal microbiota transplant is emerging as a viable therapeutic option for recurrent HE, confirmatory clinical trials are awaited and there are many challenges to its implementation14.

Refractory ascites (RA)

Ascites is commonly the first decompensation-defining event in ESLD, with reports of 3–5% of patients with compensated cirrhosis developing ascites per year15. Progression to RA is one of the most dreadful complications of ESLD as it is associated with a 1-year 50% mortality rate16. Also, RA is strongly associated with acute kidney injury (AKI), hepatorenal syndrome (HRS), and as such, clinicians need to maximize measures of nephroprotection for patients reaching this milestone. AKI entails a poor prognosis with a reported 30-day mortality rate of 29–44% and it is an independent negative predictor of transplant-free survival and post-LT outcomes17,18,19,20. Pre-renal AKI is the most common and it is related to over-zealous diuretic uptitration and/or association with dehydrating conditions (e.g., lactulose overutilization). Hence, the best treatment of this insult is prevention as a precipitating factor. We teach patients how to play an active role in diuretic titration by documenting their daily weight and provide them guidance to reach back to us to re-tailor dosing (e.g., 1 lb/day drop if only ascites vs. 2 lb/day if ascites+edema) to the lowest effective dose21.

Low-sodium diet and diuretics are the mainstay treatment options for the mobilization of ascites and edema/anasarca22,23. Particularly in the United States, where daily diet provides 4–6 g/d of sodium, it is very difficult for patients to adhere to a sodium restriction of ≤2 g/d, and there is tendency to put more weight on diuretic therapy vs. dietary education. Once RA ensues, either paracentesis or TIPS are the mainstay of treatment, however, most LT candidates have contraindications for a TIPS24,25. Standard recommendations for the management of RA cannot be overemphasized and should be addressed with LT candidates at each clinic visit: 1) low-sodium dietary education at every encounter; 2) “permissive edema”, especially for patients with intractable RA and those with prior AKI episodes; and 3) when doing a paracentesis, drain until dry and always followed by an IV albumin infusion. Importantly, there is evidence on evacuatory paracenteses improving liver/kidney perfusion whereas there is no evidence on the safety of skipping IV fluid/albumin replacement when draining <5 L of ascites26. AKI risk should not be increased when a proper dose of albumin is provided and hypotension is treated accordingly. Educating patients on a simple calculation for albumin replacement allows them to get involved with their care and favors compliance. For example, 25 g of 25% albumin per 3 L of ascites drained—if 2.5 L drained, give 25 g, if 4.5 L drained, give 50 g—grossly equates to 6–8 g/L across most body weights with current albumin commercial presentation. Given conflicting evidence from the ANSWER and the MACHT randomized clinical trials27, we do not provide outpatient intermittent IV albumin28,29, although beneficial effects could be observed if infusions are properly dose-adjusted to target a normal albumin blood level30. Since MELD 3.0 now includes albumin31, centers utilizing periodical albumin infusions will need to consider the potential for deprioritizing organ allocation to such patients as a result of improved blood albumin levels.

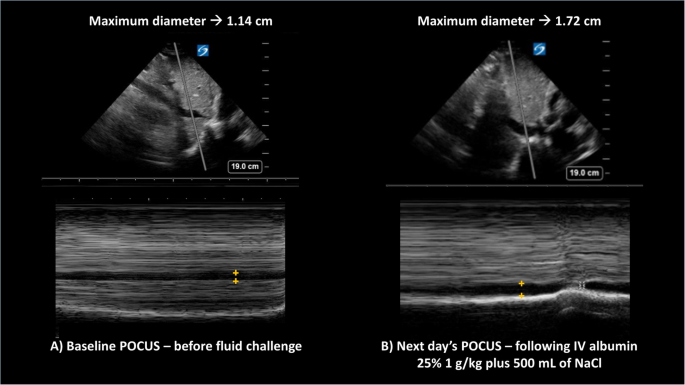

In inpatients with AKI, where intra-vascular volume status is uncertain, point-of-care-ultrasound (POCUS) plays a pivotal non-invasive role and helps formulate a sound clinical plan based on real-time physiologic evidence32. Routinely performing POCUS to evaluate the inferior vena cava (diameter/percent collapsibility) and lung edema (B-lines) can inform fluid resuscitation and prevent overt pulmonary edema in AKI (Fig. 2)33,34. Unlike outpatients where there is guidance on diuretics titration, in inpatients admitted for anasarca, it is unclear when rapid mobilization of fluid through forced diuresis can results in AKI. Here, POCUS might also become a useful tool to prevent prerenal AKI, maximize diuretic therapy, and reduce length of hospital stay. Finally, for patients with confirmed HRS, terlipressin should be started as soon as diagnosis has been made, with the understanding that there is a high risk of HRS recurrence in respondents and that the true definitive treatment is LT33. Patients with HRS-AKI should be prioritized for LT with the aim of preventing further renal disease progression in need for simultaneous liver-kidney transplant (SLKT). Undoubtfully, preventing recurrent AKI is a priority to decrease the chance of progressing to chronic kidney disease (HRS-CKD) and needing SLKT35.

For both panels, the top section shows the liver and the inferior vena cava (IVC) in B-mode ultrasound, whereas the bottom panels represent the M-mode trace for the superimposed gray line sampled from above. On the M-mode, the horizontal dark column represents the IVC maximum diameter (+orange marks). Panel A to the left corresponds to the baseline evaluation prior to starting the fluid challenge, when the maximum diabetes was 1.14 cm, whereas Panel B shows an increase in diameter to 1.72 cm following intravenous (IV) albumin and normal saline (NaCL). In both cases, the sniff test showed a calculated collapsibility ≥50%. The change from panel A to panel B suggests improved intravascular volume status.

Variceal Hemorrhage (VH)

VH is the second most frequent decompensating event and carries a mortality of approximately 20%15,36. In patients with clinically significant portal hypertension or known varices, primary prophylaxis of VH is the goal, and hence initiation of a non-selective beta-blocker (NSBB) should always be explored37,38. Among the NSBB available, carvedilol is the first choice due to higher rates of hemodynamic response than propranolol39. Starting at a low dose and titrating upwards to 12.5 mg bid or to the maximum tolerated dose is key, although blood pressure stopping rules should be followed; other NSBB can have better tolerance in ESLD (Table 1). It is critical to be mindful of patients who may be transitioning out of the “NSBB window” or past a point in their cardiac reserve (e.g., RA or high MELD)40,41,42 where NSBB can drop renal perfusion and facilitate AKI43. A careful medication reconciliation and updating of NSBB risk:benefit ratio at each encounter with providers is essential, along with a low threshold for switching to endoscopic band ligation (EBL) as prophylaxis—particularly for decompensated patients moving outside of NSBB window44. In the setting of acute VH, endoscopic stabilization should be followed by immediate consideration of pre-emptive TIPS (in Child-Turcotte-Pugh C10-13 or B8-9+active bleeding) to reduce the risk of rebleeding36,45. NSBB initiation at discharge complements VH secondary prophylaxis46, along with an outpatient EBL program.

Other ESLD complications

It is important to evaluate for the cardiopulmonary complications of ESLD in order to fully appreciate LT perioperative risk. Evaluation should commence with a contrast-enhanced transthoracic echocardiogram with global longitudinal strain and tissue doppler carefully reviewed to investigate cirrhotic cardiomyopathy47. Portopulmonary hypertension is associated with increased mortality, with old literature reporting 50% mortality when the mean pulmonary artery pressure is ≥35 mmHg and 100% when ≥50 mmHg48. There is, however, more recent evidence of successful LT in cases with severe portopulmonary hypertension following a successful response to vasoactive treatment (i.e., mean pulmonary artery pressure between 35 and 44 mmHg plus pulmonary vascular resistance <240 Wood units and preserved right ventribular function)49,50,51. Although medical treatment has greatly improved the transplant-free survival in these patients, timely LT continues to offer multiple benefits including the possibility of discontinuing vasoactive medications—reported for most patients in their first year post-LT—and eliminating the ongoing risk for further decompensation49,50,52. Despite various cutoff values described to screen for portopulmonary hypertension, most centers utilize a right ventricular systolic pressure ≥40 mmHg as an indication for right heart catheterization; the absence of a tricuspid regurgitant jet should not be considered evidence for lack of elevated pulmonary artery pressure53. Importantly, post-capillary pulmonary hypertension does not negatively impact LT outcomes and its presence should not affect transplant eligibility but be weighed against its possible reversibility, for example, if secondary to fluid overload or cirrhotic cardiomyopathy54.

Hepatopulmonary syndrome is first detected as a late right-to-left shunt on contrast-enhanced echocardiography. Relative or absolute hypoxemia is needed to establish the diagnosis. Ideally, arterial blood gases should be obtained on all patients with a pulse oximetry ≤95%, as this cutoff has a high negative predictive value to rule out severe hypoxemia (<60 mmHg) needing oxygen supplementation55. Rarely, embolization of large pulmonary shunts (type 2 HPS) is needed prior to or after LT56. For patients with ESLD-related cardiopulmonary complications, further evaluation and management should be undertaken with the assistance of cardiology, pulmonary, and transplant anesthesia colleagues.

Relevant comorbidities in LT candidates

With the increasing prominence of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), management of key risk factors is crucial in the pre-LT period, particularly diabetes mellitus (DM), as post-LT life-long immunosuppression need increases the risk of cardiometabolic disease57,58. When adjusting DM treatment, hemoglobin A1c is not a reliable metric for patients with ESLD59 and efforts should be redirected towards blood glucose monitoring (intermittent or continuous). In the selection of the management of hyperglycemia, when left to choose between insulin and oral hypoglycemic options, opting for the former needs to be emphasized due to risk of hypoglycemia with some oral agents. Over-aggressive glycemic control should also be avoided due to the risk of asymptomatic hypoglycemia (fasting glucose 115–140 mg/dL)59, which carries greater risk of harm. Recently, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists have been increasingly prescribed to this patient population, which have well-defined cardiovascular and weight loss benefits and should be considered for use in patients with MASLD60.

Unlike the general population, in ESLD it is low levels of cholesterol which are associated with increased mortality61, and although hyperlipidemia should in principle be treated as for the general population, statin use cannot be generalized. In fact, low/moderate-intensity statin therapy should be limited to ESLD patients with a Child-Pugh score of ≤7, as the experience in decompensated patients is quite limited and their initiation may cause more harm than benefit (i.e., liver and skeletal muscle toxicity) even at moderate intensity (e.g., simvastatin 40 mg daily)62,63. Given hemodynamic abnormalities seen in patients with ESLD, anti-hypertensive medications should be used with caution as they can further reduce effective circulating arterial volume and renal perfusion, resulting in AKI. This is particularly the case for angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor antagonists, which should be avoided once decompensation (particularly ascites) ensues21,64,65. Although the typical hemodynamic profile of a patient with ESLD results in a low prevalence of systemic hypertension and hyperlipidemia, cardiac perioperative risk assessment should be careful given a rather high prevalence of occult of coronary artery disease in ESLD66,67. In fact, cardiovascular complications are common after LT and constitute the main cause of non-graft related mortality, and why rigorous pre-LT evaluation and optimizations are absolutely necessary68,69,70,71. At our center, following anatomic characterization with a transthoracic echocardiogram (with bubble test), we continue with either a dobutamine stress echocardiogram (low pre-test risk assessment) or a computed tomography coronary angiogram (high risk, per presence of ≥3 standard cardiovascular risk factors). We adhere to this approach due to the lower sensitivity of dobutamine stress echocardiogram (37%), which becomes less clinically relevant for patients with a low pre-test probability72. For low-risk patients with an inadequate pharmacologic induced predicted maximal heart rate (<85%), further testing with cardiac stress positron emission tomography (PET/CT) or cardiopulmonary exercise testing may be subsequent or alternative options for evaluation. If significant coronary artery disease is identified, coronary artery revascularization may need to be performed72,73,74. We utilize drug-eluting stents only to minimize the risk of in-stent stenosis due to their superior clinical performance, and though this would necessitate longer duration of dual-antiplatelet therapy, a truncated treatment course may be acceptable to facilitate timely LT per recent data75.

The rising prevalence of the above metabolic risk factors has contributed significantly to the development of chronic kidney disease (CKD), with recent literature suggesting CKD present in approximately 47% of hospitalized patients with ESLD76. A significant number of CKD is also the result of AKI, and as previously described, the avoidance of any iatrogenic renal injury by careful detail to pharmacologic management of complications of decompensation is meant to avoid this development35. Increased recognition is also the result of a change in the definition of CKD in cirrhosis. Previously described as a serum creatinine level of ≥1.5 mg/dL up until 2011 (former HRS type 2), it is now defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for more than 3 months (HRS-CKD), now encompassing both renal disease due to structural injury as well as functional injury secondary to the aberrant hemodynamics associated with progressive renal dysfunction77,78. The recognition of renal dysfunction in a patient with ESLD has a dramatic effect on their prognosis, with pre-transplant renal dysfunction associated with persistently impaired renal function after LT79. This should always prompt us to consider a patient’s candidacy for SLKT. The decision to proceed with SLKT vs. kidney after LT in patients with prolonged AKI, HRS-CKD or acute-on-chronic kidney disease is a matter of debate and it widely varies depending on national organ prioritization policies, organ shortage, and predicted kidney function recovery. Kidney after LT is, however, a safe and effective strategy for most patients that reduces the time on the transplant waitlist and maximizes survival80,81.

Environmental and social determinants of health

Though the pre-LT process requires the care of a large multi-disciplinary medical group, it is important to add to the equation the expertise from support staff such as transplant coordinators, social workers, and mental health professionals. Patient and family education, as well as continuous open lines of communication with the LT-center, are the foundation to success. As part of our center’s evaluation, we ask the pre-LT patient’s support system to attend all clinic visits, which facilitates compliance with lifestyle changes and medication adherence, and serves as proof of their dedication to the patient in their transplant journey. The psychosocial evaluation is completed by our transplant social workers and psychiatrists. Evidence of compliance with medical directives, verification of adequate social and financial support from caregivers, as well as identification and treatment of any underlying psychiatric comorbidities is the focus of these individuals. Management of underlying psychiatric comorbidities and substance abuse disorders is paramount.

However, despite the myriad of resources invested into the transplant process and patient care, there is not a level playing field to LT access. Social determinants of health (SDoH), which encompass economic, social, environmental, and psychosocial factors that influence health, are becoming increasingly recognized as key factors that drive health inequities, including in LT. On a national level, the AASLD has sought the creation of several initiatives to help address these disparities and inequities related to SDoH82. While the national efforts are important to bring awareness and unity in these efforts, the true patient impact will be felt “on the ground”, at the local levels of our LT centers and with the outreach that we provide. Telemedicine provides, undoubtfully, an opportunity to bring LT expertise closer to home83 and ameliorate disparities related to geographic distance from LT center84,85.

One of the notable areas of inequity is with regards to racial disparities in access to the LT waitlist. Black and Hispanic patients have lower referral rates and inferior outcomes compared to white patients86,87,88. They are also frequently under-represented in the LT referral population relative to the liver disease-related health burden88. These findings are likely the results of available community resources (e.g., socioeconomic deprivation, education attainment), infrastructure-related (e.g., rurality, access to specialized care) and logistical access to care (e.g., lack of transportation, access to technology)88. Yet even when these hurdles can be overcome, further barriers in the form of health literacy and other aspects of deprivation need to be considered and identified if modifiable with proper support.

Physical fitness and physiologic reserve

As complications of portal hypertension in patients with ESLD have long-garnered refinement in therapeutic techniques that have achieved better treatment goals, there is a growing interest on the conditions indirectly resulting from ESLD, particularly in the areas of functional status and frailty89. Every year in the United States, 20–25% of LT candidates are removed from the waiting list due to clinical deterioration, with physical decline leading to frailty as a driving factor for this removal90,91. The effect is modified by the length candidates are expected to be on the transplant waitlist, such that the longer the expected waitlist time, the more important the effect and the lower the threshold that should be used for identifying frailty92,93,94. Importantly, frailty does not significantly affect posttransplant mortality, although it does prolong the transplant hospital length of stay and increase healthcare utilization93,94,95. Although favoring organ allocation for patients with frailty has been considered a strategy to decrease waitlist dropout, this is a debatable issue and it carries implementation, logistic and ethical implications (e.g., effect on equity and utility, and score dynamic adjustments with worsening/improving fitness). During discussions on the topic endorsed by the United Network for Organ Sharing in the United States in 2022, a committee of experts did not find sufficient evidence to include frailty in the upcoming continuous distribution allocation system (https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/policies-bylaws/a-closer-look/continuous-distribution/continuous-distribution-liver-and-intestine/).

The toolbox for assessing physical fitness in LT candidates is broad, but the two most studied methods are the liver frailty index (LFI) and the 6-minute walk test (6MWT)96,97. Though recommended by the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) and American Society for Transplantation (AST), the application of exercise training in patients with ESLD to avoid frailty is lacking98,99,100. Exercise and increasing physical activity are the foundation to improve frailty. Further, a supervised exercise program stabilizes ESLD by decreasing the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) and comes with significant self-reported measures of physical/mental health, as well as improved quality of life101,102,103. In all patients who undergo LT evaluation at our center, dedicated physical therapists measure physiologic reserve through LFI at baseline, and provide a personalized exercise prescription. Then, selectively afterwards on follow-up visits, LFI is monitored as a guide to prehabilitation. Our trigger for prehabilitation is an LFI ≥ 4.2.

Prehabilitation

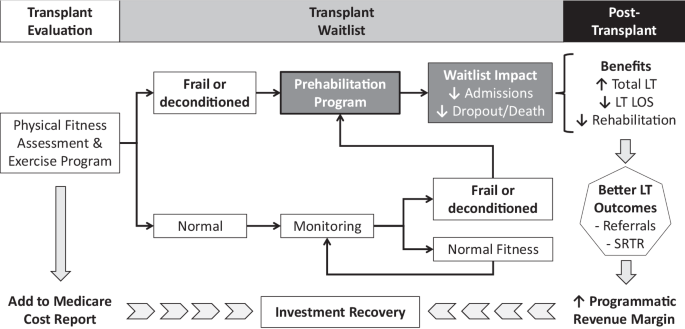

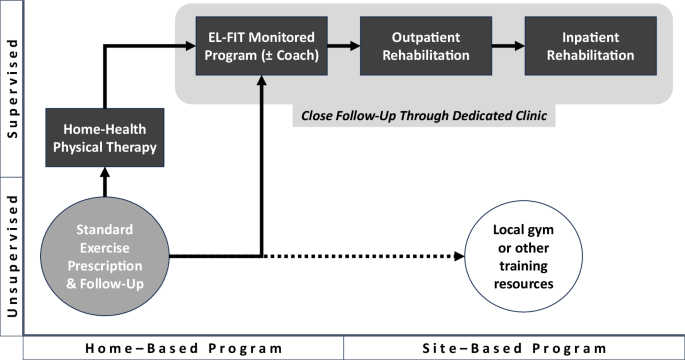

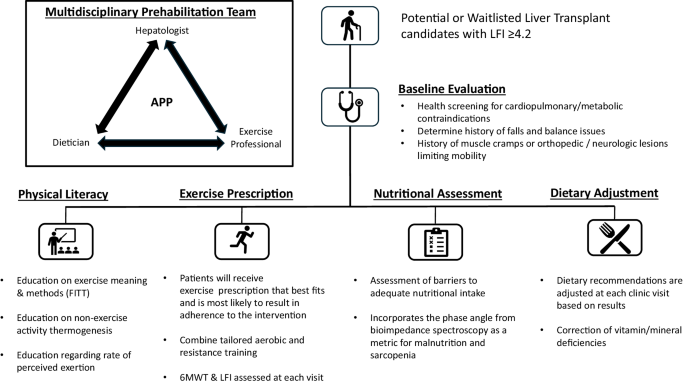

Ideally, every pre-LT patient should have ease of access to a certified exercise professional for embarking on a tailored exercise program. Although setting up a prehabilitation program seems to be an onerous commitment for a transplant center, if properly set up, it should be both financially and clinically beneficial (Fig. 3). The exercise prescription is an essential part of the prehabilitation process, and the intervention can be delivered through a combination of two formats: 1) unsupervised vs. supervised, and 2) home based vs. site/facility based. Figure 4 shows the prescription intensity augmentation sequence we follow in our clinic, which is a trial-and-error adaptive program. What perhaps constitutes the first intervention of any prehabilitation program is to clarify that exercise is a subtype of planned physical activity that aims to improve physical fitness. This simple task unmasks the lack of physical literacy in most individuals: Physical activity does not equal exercise, yet both are needed to grow in autonomy and self-efficacy. Apart from a physical literacy session, we recently incorporated physical activity as a vital sign (ACSM – Exercise is Medicine) during a candidate’s transplant clinic rooming to further bring awareness to patients and clinicians regarding physical fitness.

Baseline evaluation and monitoring of physical fitness allows referral of candidates to the prehabilitation program. Through improved physical fitness, patients are expected to have fewer hospital admissions and dropout risk from waitlist. By increasing the pool of liver transplant (LT) candidates, prehabilitation should facilitate more LT with a shorter length of stay (LOS) and less need for rehabilitation at hospital discharge. Reputational benefits from better outcomes (e.g., SRTR or Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients) should translate into more LT referrals and programmatic growth. In the end, an increased revenue margin and partial reimbursement through cost report should result in investment recovery, thus making prehabilitation a sustainable initiative.

Following a baseline assessment with liver transplant physical therapists, all potential candidates get a home-based tailored exercise prescription. Local gyms or other training resources are explored and incentivized for patients who have the autonomy to attend those places. At each follow-up visit, providers reassess and adjust prescription, augmenting to a home-based supervised program, and for those who fail to get stronger with this intervention, to a site-based supervised program (we usually start with an outpatient facility). Some of these patients need to attend a dedicated clinic able to handle frequent and personalized follow-up appointments. Importantly, patients with ESLD-related cardiopulmonary complications should be referred to their corresponding specialist (e.g., pulmonary hypertension rehabilitation or heart failure rehabilitation).

Exercise recommendations from corresponding professional societies (AST/AASLD/ACSM) mainly derive from expert opinion given the lack of large, randomized trials in ESLD. The limited evidence from heterogeneous trials had made it difficult to draw conclusions that lead to a change in practice and third-party payor coverage. Following some general principles and from small trials’ findings, it is possible to dissect the main components of an exercise prescription in ESLD using the FITT format (Table 2). Of note, since LT candidates commit to a thorough medical evaluation, it is unlikely for them to bear any limitation related to cardiopulmonary or other comorbidities for moderate-intensity physical training104. The corollary “start low and go slow” is, however, prudent advice since patients might not have objective expectations of their physiological reserve. Particularly in patients who suffer from HE, RA or frailty, it is important for their caregiver to help and supervise during exercising in order to maximize safety. Based on evidence from multiple clinical trials it is clear now that the risk for variceal bleeding is negligible, however, EBL for primary and secondary prophylaxis should be attempted if beta-blockers are to be stopped to facilitate cardiovascular adaptation during exercise103,105.

Monitoring adherence to the exercise prescription is paramount for success. Such monitoring will vary depending on the type of exercise delivery. In the case of unsupervised home-based exercise, we resource to commercially available personal activity trackers (PAT) which are good enough for the purposes of keeping patients accountable, particularly when brisk walking is the main intervention. PAT play also a central role whenever patients engage in tele-prehabilitation, which evolved from the limited availability of exercise professionals able to take care of sick ESLD patients and lack of insurance coverage for the less disabled (i.e., prefrail or early frailty). Using PAT, we have shown that patients with ESLD who walk <1200 steps/day have a higher risk for hospital admission and mortality. In fact, each additional 500-step/day decreases the risk of hospital admission by 5% and mortality by 12%106. In frail patients, we initially aim for patients to walk >1200 steps/day and we do it by asking them to add 250–500 steps to their daily walking every 1–2 weeks. Ideally, LT candidates should be walking more than 3000–5000 steps/day, depending on their baseline physical fitness.

The EL-FIT app (Exercise & Liver FITness) is a tele-(p)rehabilitation tool developed specifically for patients with cirrhosis which can provide an initial exercise prescription tailored to clinical parameters and risk of injury107. The prescription includes expert-curated resistance exercise videos in three training intensities: strength & mobility, low-, and moderate-intensity training, unlocked by the app for frail, prefrail, and robust patients, respectively. When linked to a PAT, EL-FIT can telemonitor steps, and provides a brisk-walking (i.e., aerobic) goal for each training intensity. By recording heart rate and sleep, the app further supports a trainer’s coaching efforts, and by generating a leaderboard from participants in the same category, patients can compare their efforts to that from other peers. Incorporating an exercise coach to an EL-FIT + PAT, supervised, telerehabilitation strategy recently showed clinically relevant improvements in physical fitness, as measured by LFI and 6MWT108.

All efforts above can be orchestrated from a dedicated prehabilitation clinic (Fig. 5). At our center, we follow a model centered on the efforts of a nurse practitioner to allow the complex care coordination in these patients. A cohort study following such model showed increased survival, particularly for adherent patients able to improve their physical fitness109. A registered dietician is key to further expand on ESLD recommendations while focusing on sarcopenia. Although skeletal muscle index from CT scan yields reliable sarcopenia assessment, it is not practical and rarely if ever can it be done for the purpose of monitoring skeletal muscle mass. Phase angle from bioelectrical impedance/spectroscopy is a readily available and reliable sarcopenia metric that improves along with physical fitness (data not shown) and can help target dietary protein (1.2–1.5 g/kg/day)110,111. Further supplementation with BCAA (5–10 g/d) is also beneficial per some published clinical trials. Although the combination of a BCAA with an alpha-ketoglutarate donor (e.g., LOLA) would support anaplerosis for the betterment of sarcopenia—discussed in HE section—this needs confirmation in clinical trials. In addition, as cirrhosis impairs glycogen storage, leading to an accelerated breakdown of fat and muscle, the dietary intervention should include a “late-night snack” containing 20–40 g of protein and 50 g of complex carbohydrates as a proven intervention to help maintain and increase muscle mass112. Access to healthy food is an important SDoH that needs to be addressed in patients with sarcopenia and for those with MASLD. Our nutritional intervention as part of prehabilitation does not aim for candidates to lose weight due to the risk of negatively affecting sarcopenia, and instead, we coordinate efforts with our bariatric surgeons as needed (for patients with BMI > 40–45). Despite the lack of evidence in the literature, we do not encourage transplantation in frail patients with grade 3 obesity who, in our experience, run a complicated posttransplant course with high morbi-mortality. In these circumstances, successful prehabilitation is necessary113.

The upper left pane shows members of the multidisciplinary prehabilitation team, which is coordinated by an advanced practice provider (APP). Flowchart describes the steps followed in the prehabilitation clinic, from referral indication to the end-product delivered by the members of the multidisciplinary team. The exercise professional could be represented by a physical therapist, an exercise physiologist or another sports certified trainer who has experience with patients with advanced chronic liver disease. 6MWT 6-minute walk test, FITT frequency, intensity, time and type, LFI liver frailty index.

Conclusion

An increasing number of patients with ESLD is reaching LT evaluation, and are now more medically complex than ever, thus requiring a true multi-disciplinary approach in their pre-LT care. As we acquire new treatments, both procedural and pharmacologic in the management of the complications of ESLD, a careful balance in their implementation is paramount to prevent iatrogenic complications and risk decompensation or elimination of their status as a LT candidate. Aside from management of physiologic complications, increasing attention is being paid to external influencers of clinical course. Prehabilitation can increase physiologic reserve in anticipation of LT. Social determinants of health are becoming increasingly recognized as barriers to equitable LT access and have prompted national and local efforts to improve LT access to all.

Responses