Overview and recommendations for research on plants and microbes in regolith-based agriculture

Introduction

Crewed space missions depend upon the control and integration of a tremendous number of systems and features simultaneously, with the ultimate goal of establishing a sustainable artificial ecosystem despite being surrounded by an environment ill-suited for human life. Among the numerous mission-critical components which need to be considered in the development of this artificial ecosystem, consistent access to a safe, sustainable, and sufficiently nutritious food supply is one of the highest priorities1. Absolute dependence on resupply missions from Earth is expensive, risky, and would continue to deplete resources from our own planet, all factors which would ultimately jeopardize any established colony. With estimates that continuous off-world settlements will be a reality within 50 years, temporary habitats will be established far sooner, and a reliable supply of nutrition will be crucial to support these missions.

The development of bioregenerative food systems (BFS) have been proposed as the most cost-effective approach for reducing the frequency of resupply missions and are crucial to enabling sustainable planetary colonization2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Current food production systems can supplement present day missions within low Earth orbit (LEO) but are neither sustainable nor up to the task of supporting the future demands of deep space exploration3,6. Existing BFS such as Veggie growth chamber and the APH (Advanced Plant Habitat) employ hydroponic strategies that have proven effective in the microgravity environment of the International Space Station (ISS)9. However, different solutions will be required to support long-term surface settlements off-world.

Unlike the ISS, lunar and planetary settlement efforts can utilize additional in situ (i.e., on-site) resources (ISR) available including water, atmospheric components (e.g., O2 and/or CO2), and most notably, the regolith that comprises their surfaces. In situ resource utilization (ISRU) of regolith as a substrate for plant growth has been widely regarded as potentially valuable for food production as regolith is a physical substrate and a potential source of plant nutrients (Iron, Potassium, Magnesium, etc.). This substrate does not need to be shipped from Earth reducing total costs and labor. Moreover, regolith-based agriculture (RBA) leverages centuries of agricultural knowledge and the evolutionarily adapted relationship between plants, microorganisms, and soil to support plant growth and food production. RBA can incorporate sustainable agricultural approaches that we use on Earth to minimize fertilizer consumption, avoid the spread of pathogens, promote nutrient cycling, and support interactions with beneficial microorganisms10. Furthermore, RBA can operate in parallel with other agricultural approaches (e.g., hydroponics, soilless substrates, etc.), enabling us to design a more diverse, secure, and sustainable approach for off-world food production, instead of a one-size-fits-all system.

However, despite the potential of RBA to serve as a major component in lunar and planetary-based food systems, efforts to develop and evaluate the viability of this approach have faced a number of challenges. Chief among these is the fact that little or no supply of actual lunar or Martian regolith is available for this research, forcing a reliance upon terrestrially or anthropogenically sourced proxies (termed regolith simulant’). This alone has created considerable variability in conclusions made about the viability of RBA. Additionally, studies vary widely in approach, growing conditions, plant selection, metrics for success, etc. This is not unexpected as emerging research areas, like all new frontiers, are fueled by innovation and marked by rapid, often unrestrained growth. Therefore, as the number of researchers and projects associated with any field continues to grow, it becomes necessary to establish specific conventions and best practices.

We stand at this point in the regolith community, where a critical mass of researchers has developed, and our capacity to successfully evaluate the true in situ resource potential of the lunar and Martian surface depends on establishing common protocols and terminology to effectively communicate and more objectively evaluate our work collectively. Herein we provide an extensive review of Martian and lunar regolith simulants applied to agricultural research in support of future off-world colonies. Drawing from this substantial, yet disparate, body of work we propose a ranked set of “best practices” for RBA research.

Our goals are to: (i) to inform researchers at multiple institutional levels and from various fields of expertise, (ii) to improve efforts to compare and communicate results of RBA research including increased collaboration and consultation, (iii) identify critical knowledge gaps in RBA research, (iv) and ultimately provide a more accurate assessment of the viability and technology readiness level (TRL) of RBA as a component of food-systems and bioregenerative-life support for off-world colonization. The writing of this document has been a collaborative exercise, one which has inspired new projects between the authors. In this spirit, we hope the readers will be similarly inspired to seek out collaborative approaches to best leverage expertise and produce the deliverables necessary to support sustainable food production on lunar or Martian colonies.

Properties and challenges of regolith as a growth substrate

The Moon and Mars have always been a subject of human fascination providing a wealth of data obtained through remote sensing and robot missions11,12 and returned or soon to be returned samples for terrestrial-based analysis13,14. The regoliths of both surfaces could potentially provide multiple agriculturally relevant resources. For example, Mars provides access to carbonate and acidic sulfate materials potentially useful in the regulation of pH of nutrient fluids applied to agricultural systems. The Moon similarly provides potentially useful substrates and additionally serves as a testing ground for the first suite of off-world agricultural systems used to develop similar systems for Mars.

However, lunar and Martian regolith are also very different: The lunar regolith is created through space weathering (impact processes, radiation, no atmosphere) over billions of years in a reducing, vacuum environment15,16. while Martian regolith results from various impact, eolian, aqueous and other processes acting over billions of years on a globally basaltic crust12,17. This has produced two very different regolith substrates that present unique challenges for agriculture.

Analysis of the overall chemical makeup represented as elemental oxides alone is insufficient to fully describe or predict regolith viability (i.e., fertility). In evaluating the viability of soil, soilless media, or regolith as a growing medium, a variety of characteristics are considered including nutrient content and mobility, pH, salinity, contaminants/toxins, organic content, texture, density, porosity, strength (shear and compressive), etc. Thus, to understand the potential of Martian or lunar regolith as a growth medium (and appropriately mimic it) a variety of characteristics that more fully describe (or mimic) this should be applied. Here we provide an overall summary of lunar and Martian regolith-fertility as currently understood. This includes a summary of the overall chemistry, mineralogy, and physical characteristics (texture, soil strength, etc.), a comparison of overall elemental abundance to plant requirements (Table 1), and how well constrained/understood these aspects are currently and what relevance these hold to the application of regolith as a growing medium.

Defining regolith

To address the challenges facing RBA for successful implementation, it is essential to accurately simulate relevant characteristics of the target regolith. Indeed, even the term “regolith“ can introduce confusion into the discussion depending on the definition applied and the common practice of interchangeably using terms such as “regolith“ and “soil”, or even referring to non-regolith materials (e.g., bed-rock deposits) as regolith. Regolith is defined as the “unconsolidated material covering bedrock and can include dust, broken up rocks, soil and other related materials”18,19,20. Thus, regolith incorporates a variety of unconsolidated materials on the surface separating it from consolidated units that would be termed bedrock. However, weathering produces a gradation from un-weathered bedrock to fully developed soils and it can be difficult to pinpoint the exact point at which the material is unconsolidated enough to be considered regolith and no longer bedrock.

As regolith encompasses a broad range of materials, it is useful to distinguish different fractions of the regolith using terms such as soil and dust, depending on the particular context. For example, when examining the pedological history of the regolith, distinguishing among dust, soil, etc. is practical as different processes (i.e., eolian-wind and fluvial-river) affect these portions differently. Such variations provide important distinctions in interpreting the resulting history recorded in the materials. Similarly, from an engineering perspective “soil” and “dust” represent behaviorally and physically separable portions of the regolith21,22. For these and other examples, it is useful and appropriate to refer to a particular portion of the regolith as soil.

However, this “soil-like” portion of lunar and Martian regolith is distinctly “unsoil-like” from an agricultural perspective, in particular in its lack of well-developed soil horizons, absence of organic matter, and other characteristics more typical of common “agricultural soils”, making the term “soil” less useful in an agricultural context. Soil is a complex matrix, and details of its components can be found in Table S1. Due to the distinct agriculturally relevant differences between agricultural earth soils and extra-terrestrial “soils”, it is useful to use the term regolith when speaking of extra-terrestrial “soils” as an agricultural material. Thus, this work will use the term regolith to refer to the unconsolidated “soil-like” materials or in other words material one could readily scoop off the surface, not necessarily including or excluding dust (SI Section Table S1). The term bedrock or other appropriate terms are used for non-regolith materials, and the term surface materials refers to any surface/near surface material: both regolith and non-regolith.

Lunar regolith characteristics

Lunar regolith composition and chemistry

The lunar surface can be divided into two main, distinct geologic provinces: the felsic lunar highlands and the mafic lunar mare23. The lunar highlands are dominantly anorthositic11,24 with up to 98% anorthite content25. The lunar highlands regolith (e.g., Apollo 16 and Luna 20) is dominantly felsic, composed of calcium-rich plagioclase with little pyroxene and other mafic, magnesium- and iron-rich mineral content13,15,24. It is assumed that the mixing of basaltic materials with the felsic highlands material is due to impact gardening and ejecta being distributed around the surface of the Moon due to the low gravity and high energy nature of impacts. The lunar mare is thought to have formed from basaltic volcanic materials rising from the lunar mantle after the initial formation of the Moon26. The mineralogy of the lunar mare regolith (e.g., Apollo 11, 12 and Luna 16, 24) is nominally basaltic, containing mostly ferromagnesian minerals with clinopyroxenes, olivine, ilmenite, and lesser amounts of calcium-rich plagioclase relative to the highlands24,27,28. Though the composition of regolith in the lunar mare is generally consistent from site to site, the youngest regions have unusually high concentrations of potassium (K), rare earth elements (REE), and phosphorus (P); these regions are called the Procellarum KREEP Terrane29. Apollo 15 and 17 landings were made in areas marginal to highlands and mare and have compositions intermediate to both with rock fragments derived from both provinces13,15. Phosphorus is found in relatively minor, but consistent, amounts in the lunar regolith30 and particularly in the KREEP terranes in minerals such as schreibersite31. Potassium is an incompatible trace element in the lunar regolith30, and the potassium content of the lunar regolith is mostly found in the KREEP regolith. The lunar regolith has a negligible nitrogen content, and the nitrogen that is present was mostly deposited by solar winds30. This makes lunar KREEP materials potential sources of nutrients for plant growth (Table 1).

The lunar surface is significantly altered by space weathering, creating nanophase iron particles and glassy agglutinates in its regolith due to the Moon’s lack of atmosphere and vacuum conditions15,32; Most lunar agglutinates are enriched in iron, magnesium, titanium, manganese, chromium, and scandium and other lithophile elements such as potassium, lanthanum, and cerium, but are depleted in elements compatible with plagioclase relative to bulk regolith regardless of formation in mare or highlands regions33, but the lunar mare is noted to have a higher agglutinate content than the highlands. The abundance of agglutinates and the ratio of nanophase iron concentration to the total iron content of lunar regolith is the maturity index of the regolith32,34 in the lunar regolith and is a function of the duration of surface exposure35,36. The enrichment in ferromagnesian and lithophile elements is more pronounced in immature regolith and as regolith maturity increases, an increased proportion of plagioclase is observed in agglutinitic materials33,34. This maturity affects the regolith’s composition, especially in finer fractions, where the resemblance to agglutinate glasses increases and presence of nanophase iron increases, highlighting the dynamic nature of the lunar surface composition.

The composition described provides a medium rich in calcium, aluminum, magnesium, iron, and titanium but with much smaller amounts of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and sodium30,37. The high calcium, aluminum, magnesium, iron, and titanium content of the lunar regolith is potentially useful for plant growth, as these elements play roles in nutrient supply, growth, growth stimulation, and photosynthesis. However, these elements are not guaranteed to be bioavailable to plants and may require additional effort to mobilize these elements for use. The lack of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium also represents a significant challenge as these are major elements required for plant growth. This means that the lunar regolith will need to be processed and amended to increase mobility of certain nutrients and incorporate missing nutrients to enable optimal plant growth (see Table 1). What exactly these processing needs entail and what nutrients this will affect them is an area of needed research.

Lunar regolith physical properties and implications for plant growth

The particle size distribution and specific surface area of a medium for plant growth influence the permeability and fluid retention properties of the material38, and thus directly impact plant growth. Particle size analysis of lunar regolith shows that the mean grain size of returned samples ranges from 40 µm to 800 µm, with a lunar global average between 60 and 80 µm15,39. The wide range of particle sizes in lunar regolith allows for smaller particles to nest between larger ones, causing more complete filling of void space and decreasing permeability. Since the lunar regolith and appropriate simulants are composed of igneous mineral grains, water retention is controlled by the bulk porosity and the pore content of individual grains (measured by specific surface area), which is low compared to soils and other carbon-rich materials38. These properties of the lunar regolith imply that there are particle sizes and particle size distributions that give the required porosity and permeability for plant growth in lunar regolith that must be carefully balanced in regolith-soil mixes to allow for the most efficient delivery of water and nutrients.

In order to seek out local resources (e.g., water and other nutrients), plant roots grow and push their way through the growing medium. The compressive and shear strength of a plant growing medium determines the relative ease of penetration; a stronger material is harder for roots to push through. The shear and compressive strength of a material increases with increasing relative density and decreasing porosity. The density and porosity of lunar regolith have been shown to vary from site to site on the Moon and increase with depth within a single site, implying that mechanical strength varies in the same manner40. From a low relative density, the lunar regolith compresses significantly due to the high initial porosity and the crushing of weak, glassy grains during compression, but a minor change in initial relative density during compression leads to differing compressive strength estimates, especially in the relatively less dense upper 30 meters of regolith40. These results have strong implications for acceptable densities and amounts of compression of lunar regolith mixes for plant growth in terms of both root penetration and permeability for water delivery. Lunar regolith has high cohesive and frictional strength40,41 making penetration (whether instrumentation or plant roots) difficult, and increasing the required amount of energy a plant must expend to reach nutrients as the root system expands.

Martian regolith characteristics

Martian regolith composition and chemistry

The Martian regolith has a generally basaltic mineralogical profile that thus far has been globally homogenous (though there are locally altered soils that deviate from this)12,42,43,44,45,46,47 The mineralogical profile of the regolith includes plagioclase, pyroxenes and olivine as major phases and magnetite, ilmenite, quartz, potassium feldspars and various salts as minor phases48,49,50,51. Two specific sites with samples taken by Curiosity from which this data is available include Rocknest and Gobabeb, both basaltic sands sampled within Gale Crater49.

In addition to identified mineral phases, all of Mars surface materials so far examined using XRD have included what has been termed an amorphous fraction consisting of crystallographically disordered materials that make-up ~20 to 50% of the sample52,53. The exact compositional make-up of this amorphous fraction is poorly constrained and variable among different surface materials, but a general chemical make-up of a particular sample can be understood with the application of multiple instruments and techniques54. It is thought to include materials like basaltic glass, nanophase iron oxides (e.g., ferrihydrite and maghemite), proto-phyllosilicates, carbonate and sulfate and other highly disordered materials (e.g., allophane or hesingerite)48,54,55,56,57,58,59. Such disordered phases are often the most reactive in Earth soils and can greatly influence overall soil fertility60. Thus, although poorly constrained, to the greatest extent possible it is important to appropriately represent these phases in regolith-based agricultural experiments19,61,62.

The compositional profile from both crystalline and non-crystalline phases provides an abundance of P, Mg, Ca, Fe, Na, Cl and Si moderate amounts of K and only trace amounts of N, relative to plant’s needs. Of course, this does not take into account the bioavailability of these nutrients but many of the minerals these are found in tend to be more bioavailable forms so at least some portion is expected to be plant extractable. Another important caveat is that some micronutrients (in particular Fe, Na, Cl, or Mg) may be present at phytotoxic levels. However, it must be noted that the amount of any micronutrient required to cause phytotoxicity varies depending on the plant species, substrate pH, and other synergistic or antagonistic nutrients present in the substrate. Additionally, though the overall chemistry and mineral profile (outside of the amorphous fraction) is fairly well understood for present day Mars soil42,61,63, other characteristics are less well-constrained or can only be inferred from indirect analysis based on available data. This includes features such as pH, salinity (including the implications of perchlorates/chlorates), nutrient content and mobility. All the major macronutrients and most required by plants have been detected in Mars regolith or meteorites63,64 and the mobility and bioavailability of these can be inferred to some extent but is generally not well understood.

The Mars Phoenix Lander mission provides the only direct measurements of pH and salinity to present-day Mars soil providing one location and three samples of direct measurement65,66,67, though pH and other geochemical aspects can be somewhat inferred from other mission such as the Viking Landers. More recent analysis of soils at Gale crater provide enough information that we can indirectly infer that the overall characteristics are likely to carry over, though there is variation in the ratio of salts found68. The pH of Mars soil measured by Phoenix Lander averaged ~7.7 ± 0.3 indicating an alkaline soil67,69. It should be noted that this pH is within the acceptable range for most crop plants (~5 to ~8), and that at this pH most nutrients are bioavailable for plant uptake. Data from multiple missions (including Phoenix and Curiosity) provide an estimate of about 1–3 wt% salts in the regolith dominated by various Mg, Ca, and Na perchlorate, sulfate and carbonates65,67,70,71,72, though some regolith and bedrock salt concentrations can be much higher73. The ratio does vary (there is a higher proportion of perchlorates from Phoenix Lander samples than from Gale crater samples) though Mg and Ca tend to be much more dominant over Na salts67,71,72.

The presence of so much salt in the regolith makes salinity one of the major concerns for Martian regolith in growing plants (among other important potential applications). Preliminary regolith experiments that used high concentrations of perchlorates (2 wt%) resulted in no plant germination, where other experiments with lower concentrations resulted in plants with a significantly lower dry biomass and smaller leaf area overall10,74. Visscher et al. demonstrated severely limited growth of Arabidopsis thaliana in response to Mars-like levels of magnesium sulfate73. Thus, the overall salinity is high enough to be problematic for salt sensitive crops, but the most prominent concern is the perchlorate, as it can also induce molecular oxidative stress75. Perchlorates likely occur at high enough concentrations to create concerns for toxicity of food sources (however this depends on the extent that it is taken up into the edible organs, which depends on the crop), though a more precise understanding of the potential for bioaccumulation has not been established76,77.

Martian regolith physical properties and implications for plant growth

Much like the lunar regolith, Martian regolith has been subjected to a long history of impact processes which influence particle size frequency and other grain characteristics. Eolian and fluvial processes additionally sort and alter grain characteristics and the balance of these are key in the resulting grain characteristics and thus the resulting cohesive and shear strength of the regolith. For present day regolith eolian and impact processes are the dominant processes of concern78. Impact processes tend to have poorly sorted, angular materials which can increase cohesion while eolian processes tend to increase sorting and rounding of grains, decreasing cohesion. Particle size frequencies also differ: eolian ripples are often bimodal (occasionally multimodal) likely indicating the involvement of multiple processes79. Herkenhoff et al. measured bedforms in Gusev crater to have one mode dominated by grains between 1 and 2 mm and the other dominated by grains below 210 µm79. Outside the bedforms, a mixture of grain sizes and clasts was observed.

Thus, the cohesive and shear strength of Mars regolith resulting from grain characteristics can vary depending on which processes dominate. This is seen in recent challenges of “drilling” into the surface faced by the InSight mission “mole” probe designed to function in a cohesionless material (such as a basaltic sand) but failed to penetrate to adequate depth due in part to the higher than expected cohesion80. Like lunar regolith, these physical properties of the regolith limit the ability of root penetration and development making plant development difficult in the regolith without appropriate treatment.

In addition to the physical and mechanism contributions contributed by particle size, density, and angularity to the cohesion and shear strength of Martian regolith, the aggregational nature of certain materials in Mars regolith, namely salts, increase the regolith’s cohesive aspects78. The precipitation of salts in the regolith help to cement the soils together and the occurrence of cemented chunks or even duricrusts has been observed during the course of multiple missions including InSight and Curiosity51,81,82. Because this cement is at least partially soluble in water, any treatments or processing with water (including watering plants) can also affect the distribution or extent of cementation within a sample, perhaps decreasing it with rinsing. Thus, appropriate processing of Martian regolith must take these both the physical and chemical (cementing) aspects into account when considering effective approaches to addressing the regolith strength for agricultural applications.

Overview and current state of the challenges of lunar and Martian regolith as a growing medium

The above discussion presents both benefits and limitations for using regolith on the Moon and Mars for growing plants. The challenge for current and future research is to present ways in which limitations may be ameliorated, benefits maximized, and the overall result compared with other avenues to determine the most sustainable agricultural approaches to apply.

Since the Moon is Earth’s nearest cosmologic neighbor, human infrastructure that is developed on the lunar surface will benefit from the comparatively easy and quick access to terrestrial resources, even though established lunar colonies are intended to be mostly self-sustaining. This means that it is more feasible to supplement the lunar regolith with fertilizers from Earth or from waste and recycling if there are vital nutrient deficiencies that cannot be addressed using in situ lunar materials. This convenience is exclusive to the Moon because of the small distance to Earth, so other planetary settlements (e.g., Mars) will need to be able to supply the necessary nutrients with little to no material input from Earth.

In general, those nutrients required to supply fertilizer could be provided from in situ or waste materials efficiently recycled. Macronutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium are of particular concern as they would be required at volumes that would be difficult to supply from Earth64. Phosphorus is relatively abundant on Mars and at least some fraction in plant extractable form83. Potassium is not particularly high in the Martian soil, but is present in bedrock units and could potentially be obtained from other surface materials in situ84. However, Potassium and Phosphorus are limited on the Moon and would likely need to be supplemented from Earth-based sources, or provided by plants and people pseudo-in situ85. Nitrogen has been detected on both the Moon and Mars, but only in trace amounts and no reserves large enough to support in situ supplies has been detected68,86. Micronutrients like iron, boron, and chloride are frequently detected on Mars and likely available in situ, but may also be problematic if present at too high of concentration of a bioavailable form to become toxic87. The Moon contains an abundance of metallic nanophase iron that depending on mobility may have concerns for iron toxicity as well, though studies are needed to establish the expectant mobility within closed systems presented by lunar colony habitats. Calcium, magnesium, and sulfur are very abundant on Mars and expected to be plant extractable through salts. Salts present a problem in and of themselves66,67,88, but even the issues of salinity on Mars have potential solutions73.

One potential solution is to genetically modify crop plants to tolerate higher concentrations of perchlorates, which has been somewhat effective in Arabidopsis73, however this has only been demonstrated in Arabidopsis, and will likely not be developed in larger crops within a reasonable timeframe, if at all. Another commonly cited solution is rinsing of the regolith as each of the problematic salts are readily soluble and could potentially be rinsed out of the soil. However, initial experiments from Oze et al. demonstrate limitations to this approach74. Perchlorate may also play a role as a resource as various biogenic reactions can degrade perchlorate to chloride producing oxygen as abyproduct77. However, even though potentially useful, there are many aspects of such an approach that need to be addressed: e.g., to what extent biogenic reactions would be effective, how much oxygen could be expected, and what to do with the chloride that results which is also problematic at those concentrations for the plants.

Lunar and Martian regolith simulants and agriculture research

In order to identify appropriate methods for processing regolith for agricultural applications, potential methods must be tested. However, samples of regolith are not generally available for use in agricultural research. Instead, regolith simulants are created that attempt to mimic the characteristics of actual regolith. In order for results to accurately reflect plant response to regolith-based growing mediums, they must accurately mimic agriculturally relevant characteristics of actual regolith19,22,61,89,90,91. Multiple regolith simulants have been produced for both the Moon and Mars and a summary of these is available from a recent review by ref. 22.

The accuracy of a regolith simulant is limited by many factors including the availability of data for the target regolith, materials that resemble the target regolith, and feasibility of mimicking particular characteristics on a large scale91. For example, lunar regolith contains agglutinates and nanophase iron that are likely to have significant effects for agriculture, but very few simulants mimic these characteristics due to the difficulty of reproducing them on even a small scale. Martian regolith contains salts and other components relevant to agriculture identified in recent missions such as Curiosity. However, the most widely used Martian regolith simulants (JSC Mars 1a and Mars Mojave Simulant (MMS-1 and MMS-2)) do not contain these components as they were developed early in the exploration of Mars before such characteristics were well understood19,61,89,92. As data and methods improve, so does the need to create new simulants that more accurately mimic the target regolith. Indeed, the last few years have seen great efforts in increasing the accuracy of both lunar and Martian simulants including a few higher-quality commercially available options19,61,93,94. However, it is not feasible to mimic every aspect of regolith so even the more accurate simulants are often more accurate in features particular to a specific application. The review provided above and best practices recommended below do not intend to sponsor or promote any particular simulant. Rather we emphasize the need to ensure the accuracy of relevant characteristics for simulants aspects applied to RBA research to the extent possible and relevant for addressing the fundamental questions intended in the study.

A brief history of regolith-based agriculture research

Over decades, researchers have theorized about growing crops on the Moon and Mars.

-

As early as 1970, Walkinshaw and his collaborators analyzed plant physiology and productivity when exposed to lunar materials from the Apollo missions95,96,97.

-

Baur et al. and Milov and Rusakova, built on these preliminary studies, with the latter adapting a more applied view by suggesting a closed greenhouse system as a possible solution98,99.

-

The closed greenhouse idea would be later explored by Walkinshaw in 1986 while he tried to fully understand the interaction between plants, regolith, and microorganisms in an enclosed system100.

-

Mashinskiy and Nechitaylo’s “The Birth of Space Agriculture” was the first organized review on the subject101.

-

Ming and Henninger published a book that directly addressed this subject in a compilation of articles that discussed the feasibility of off-world Agriculture102. In this book, Fairchild and Roberts103 contemplated options for human settlement on the Moon and Mars in a detailed way and divided their narrative into four scenarios entitled “The 1988 Case Studies”102. The first scenario was a human expedition to Phobos that did not involve ISRU utilization. The second was a human expedition to Mars with a crew of eight, where four crew members would reach the surface to collect data with heavy orbital support and some IRSU utilization. The third case study was a lunar observatory outpost that would switch categories and be classified as a science outpost in the resource allocation category. The outpost would house a crew of 4 for 20 days while all the resources would be provided in situ to the crew during this period but still with partial orbital support. The fourth and last case, the Lunar Outpost to Early Mars Evolution scenario, would be an ISRU-based, self-sustaining station housing a crew of eight over a period from 24 to 52 weeks between rotations103. The concerns and possible solutions to the technical, economic, political, and cultural issues that acted as barriers to permanent settlement beyond LEO in their time remain relevant to this day.

-

However, case studies like those listed above-inspired researchers to overcome these challenges and ultimately provided the foundational data to begin the discussion of ISRU for life support systems and led to the creation of NASA’s Controlled Ecological Life Support System program. Ripples of this movement were fast to follow, with publications focused on integrating ISRU with Regenerative Life Support Systems (RLSS) and the discussion of possible agricultural scenarios for lunar and Martian outposts37,104,105,106.

-

As knowledge progressed, researchers saw the necessity to develop more reliable tools to mitigate plant stress and thus improve crop productivity. One of these first approaches was by ref. 107, who emulated ecological substrate colonization phases in regolith using pioneer species (e.g., Tagetes patula L.) associated with root-colonizing microorganisms. Kozyrovska observed that it took a long time until the substrate was ecologically stable enough to support full crop cycles, though this work did eventually grow plants107. These results further strengthen the idea that some regolith amendment was needed to make regolith-based agriculture possible, which steered the scientific community to explore several approaches to “hack” off-world agriculture.

In recent years, exploration of the topic has continued with a broad focus of applications from experiments that explore small-scale early exploration possibilities, challenges, and conditions74,108 to long-term exploration that considers potential of much larger-scale agriculture (e.g., 61). Though, even after showing promising potential64,109,110, regolith amendment technologies still seem unable to create a sustainable crop rotation system. These challenges underscore the need for further investigations, especially when it comes to controlling severe pH shifts around the rooting zone stratification (either acidic or alkaline) that directly affect the plant’s physiology111, by the presence of elevated or trace levels of perchlorate in Martian regolith-based trials10,74,112 or by the need of an active microbiome that is capable of surviving in a regolith substrate, utilizing the substrate and other in situ resources, and reverting them in a continuous way to create a closed nutrient cycle that has both plants and microbiome as the primary energy providers at each end of the spectrum. Most recently, small portions of lunar regolith collected during the Apollo Program were used to successfully germinate and grow Arabidopsis thaliana113. This study provided crucial confirmation that lunar regolith does indeed have the potential to function as a substrate for plant growth, albeit with significant stress to this model plant.

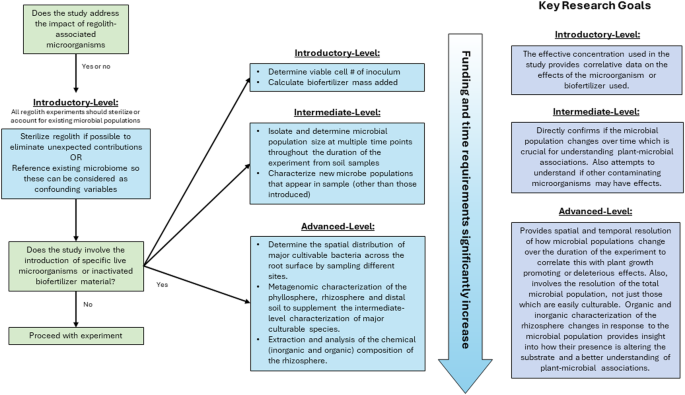

Applications and sources of microorganisms in regolith-based agriculture

Sterilization of nearly all surfaces, including biological ones like seeds, is a common strategy in space exploration for a variety of reasons. However, an axenic approach to sustainable agriculture i.e., one in which the plant(s) is/are the sole constituent step of a BFS, is not a reasonable, nor desirable approach in any environment. The origin and success of terrestrial plants are intimately coupled to the microbial cohorts that populate their surroundings and surfaces, affecting them physiologically, genetically, and biochemically throughout their life114,115,116,117. Indeed, the region of soil within 1 cm of the root surface, known as the rhizosphere, often contains a significantly more dense and diverse population of microorganisms than bulk soil. With estimates as high as ≈1011 microbial cells/gram of host tissue with over 10,000 different species present roots are a “hotspot” of bio- and metabolic diversity117,118,119,120. These diverse microorganisms impact agricultural yields, plant disease resistance, nutrient utilization, nutrient uptake, ecological robustness, and secondary metabolite production114,121,122,123,124,125,126,127. So crucial is this relationship, that both plants and microbes have evolved a variety of biochemical pathways to drive the selection and maintenance of these interactions. This population adapts to and influences their host plants both spatially and temporally, making them crucial players which must be incorporated into any model for sustainable agriculture regardless of the ecosystem they will ultimately inhabit114,122,124,128,129,130.

Understanding and manipulating the holobiont, the total collection of the host plant and its microbial cohorts, is key to optimizing plant growth especially in challenging substrates like lunar or Martian regolith. While hormone manipulation, such as the reduction of ethylene production, is a generally useful feature conveyed by some plant growth-promoting (PGP) bacteria, activities that directly modify the growth substrate and/or nutrient availability are likely to be of greater utility in regolith-based agriculture114,117. PGP phenotypes that could directly impact nutrient availability or regolith composition include: (i) phosphate solubilization, (ii) nitrogen fixation, (iii) iron sequestration and redistribution, and (iv) the formation of soil organic matter (SOM). Phosphate solubilization is a common PGP phenotype observed in the rhizosphere performed by both fungi as well as bacteria. Similarly, bacteria-derived chelators known as siderophores can sequester and redistribute the rich iron deposits within regolith, improving availability of this important micronutrient to host plants. Nitrogen fixation by free-dwelling or nodulating species of bacteria is of particular interest given the limited amounts of this important macronutrient observed in regolith to date, as well as the costs (and risks) associated with shipping solid nitrogen-based fertilizers to a lunar or Martian colony86. Finally, rhizosphere bacteria can utilize root derived exudates as well as other exogenous sources of carbon to facilitate the conversion of regolith to SOM.

Though important differences exist between the microgravity environment of LEO and the hypogravity environments of the Moon and Mars, studies aboard the ISS can inform our understanding of some aspects of growth in regolith, such as the composition of available bacteria for formation of a robust microbiome at plant surfaces131,132. The present approach of seed surface and growth substrate sterilization means that the plant microbiome which does form in these isolated environments will be almost entirely derived from the microbiome of the colonists, or the endophytic bacteria safely protected within the seed coat133,134. However, even from within this population of primarily human-derived microorganisms, a number of potential PGP microbes have been identified135. This underscores the potential to select and develop beneficial microbiomes from the populations most likely to develop in these isolated environments and which have established spaceflight histories. While such studies are ongoing, an alternative or complementary approach will be the introduction of specific microbial cohorts to facilitate RBA, an approach which has been explored in a variety of regolith simulants. Here we review these initial efforts to exploit microorganisms to improve the ISRU viability of Martian and/or lunar regolith with a particular interest in their potential to support plant growth.

Establishing a baseline—microbial composition of regolith simulants

Both environmentally and anthropogenically sourced regolith simulants are likely to harbor microorganisms which can influence the results of RBA research. Sterilization of these simulants to remove these initial populations is problematic due to the limited ability to sterilize bulk quantities for larger research, as well as the potential for various sterilization methods to alter the composition of the regolith simulant. Yet little characterization of the initial microbial composition of these simulants has been conducted to date, despite their potential to impact the results of work conducted therein. Studies by Allen et al. examined the microbial profile of JSC Mars-1A, an early and heavily utilized MRS136 and identified a number of bacterial and fungal species present in untreated simulant137,138. Among the eight species of Bacillus they identified were B. megaterium and B. licheniformis, both of which are potential PGP species via improved nutrient solubilization or gibberellic acid production, respectively. Several species from the order Actinomycetales were also identified, including at least one species of Streptomyces. Several fungi from the genera Aspergillus, Penicillium, and Fusarium were also isolated. Aspergilli and Penicillium species may have PGP potential via phosphate solubilization as well as the production of antimicrobial agents to control microbiome composition139,140. Meanwhile, the presence of Fusarium species is of significant interest, given they are well-associated with a variety of crop diseases141. Similar efforts to characterize the initial microbial load and composition of other regolith simulants have yet to be performed, but are important to adequately establish the starting microbiome for plant-microbial associations in RBA research. While standard enumeration assays could provide quick insight into the total number of microorganisms in these samples, species/genus resolution would help identify the potential for PGP phenotypes already present among these populations.

Microorganisms viability in and utilization of regolith simulants

Regolith simulants have been extensively used in research for astrobiology as well as planetary protection, as substrates for a variety of microorganisms exposed to the harsh environments of Mars. For example, several species of methanogenic Archaea introduced into a variety of regolith simulants can survive both desiccation and the hypobaric (low-pressure) environment associated with the surface of Mars142,143. In these species, metabolic activity, specifically methane production, was restored by rehydration suggesting a model for how microscopic life on Mars could persist via rounds of desiccation and rehydration via intermittent flows of water.

Similar studies were conducted with a variety of bacterial species and confirmed that strains of B. subtilis and Enterococcus faecalis suspended in a variety of regolith simulants were also resistant to extreme desiccation, perchlorate exposure, reduced atmospheric pressure, and Mars-equivalent UV exposures144. Regolith analogs have also been used for planetary protection studies, specifically to observe whether bacteria could be transferred from the wheels of a rover to the Martian surface145. Taken together, these studies further establish regolith as a viable substrate and reservoir for microorganisms, one that could protect some species over short durations in the case of life support system failures, a potential benefit to RBA efforts.

Based on existing data, both lunar and Martian regolith contain many macro- and micronutrients of benefit to the health of plants and humans, as well as potential industrial applications. In our discussion of existing microorganisms in regolith simulants above we identified several species with the potential to improve plant growth, based on their ability to improve the solubilization of important materials such as phosphate. However, the use of microorganisms to improve the extraction of other essential elements from regolith simulants has also been explored. Work by Cousins et al. explored the potential of JSC-Mars-1A as a biomining substrate for the extraction of iron by several species of bacteria including Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, Shewanella oneidensis, and Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense146,147. In most cases, the cost-benefit analysis confirmed that the nutrient inputs required exceeded the value of the iron extracted in these studies. However, S. oneidensis did emerge as a promising candidate for the extraction of iron for a variety of applications in a cost-effective manner and could be utilized in an early pre-treatment step.

Further work with A. ferrooxidans utilizing both LMS-1 and MGS-1 as substrates confirmed their ability to improve the solubilization of Si1+, Mn2+, Mg2+, and iron (as Fe2+) suggesting this microorganism may also be of benefit depending on the simulant and growth conditions employed148. In this latter study, cultures grown in a clinostat showed a significant increase in mineral solubilization relative to 1G controls. However, given that the microgravity conditions simulated by clinostats can vary significantly from the partial gravity environments on Mars and the Moon, the importance of these enhancements is unclear. Ultimately, the ability to mine essential minerals from regolith could be of considerable benefit to RBA.

Plant growth-promoting microorganisms in regolith

The studies above support the potential of microorganisms to transform regolith into substrates better suited for plant growth. While such bioweathering/bioleaching may occur with greater frequency within the rhizosphere and could provide inorganic nutrients in support of plant growth, they are not due directly to interactions with a host. Yet, the importance and potential benefits of plant-microbial associations are becoming increasingly clear in the development of next generation agricultural solutions here on Earth and will almost certainly be part of a strategy for successful RBA systems off-world. Here we will discuss preliminary regolith-based research which incorporated the two most well-established plant-microbial associations: nodulation and mycorrhizal fungi into regolith studies.

The legume-rhizobia symbiosis supports plant growth via nitrogen-fixation in ~20% of all land plant species and represents a crucial interaction which could minimize potentially damaging environmental inputs of fertilizers149. As a result, there is considerable interest in whether lunar or Martian regolith could support this mutualistic symbiosis. Seeds of Melilotus officinalis (sweet clover) have recently been shown to support the formation of active N-fixing nodules in conjunction with Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021 in MMS-1150. This study confirmed that nodulation was sufficient to increase total plant biomass accumulation by an order of magnitude relative to uninoculated controls. Species like clover are routinely used to introduce nitrogen and organic matter into soils and could be used to convert regolith into soil prior to farming attempts. Similarly, Rainwater and Mukherjee confirmed nodulation as well as increased growth in seedlings of Medicago truncatula, a model system for symbiosis research, in both MMS-1 and MMS-2 by three different species of rhizobia151. While both of these studies have been conducted in regolith simulants of lesser accuracy, they underscore the potential to capture this important symbiosis for sustainable agriculture. Notably, successful nodulation under hydroponic conditions is less established and their benefits on growth are poorly characterized in contrast to a wealth of information from soil research.

While nodulation represents an important and relatively common plant-microbial symbiosis it is far from being the most common of these associations. Indeed, an estimated 75% or more of terrestrial plants are capable of forming associations with mycorrhizal fungi to improve nutrient uptake, sensing, and disease resistance152. Such associations are presumed to be among the earliest plant-microbial symbioses to have evolved in terrestrial plants and harnessing this activity would be immensely useful for RBA systems. Preliminary efforts confirm that the lunar regolith simulant JSC-1A is capable of supporting the growth of the mycorrhizal fungi in association with prickly pear seeds (Opuntia ficus-indica)153. Specifically, Trichoderma viride as well as one or more isolates of the genus Glomus, both of which can improve host plant nutrient uptake and/or limit pathogenic infections by deleterious fungi. The addition of mixed cultures of these fungi significantly improved the germination of seeds of O. ficus-indica underscoring the potential for such microbial amendments as a tool for improving cultivation at an additional point (germination) not just in support of vegetative or reproductive growth.

While specific plant-microbial interactions are beneficial, an approach that leverages species and functional diversity is more robust and sustainable over the life of a single host plant as well as for the substrate (regolith) that will sustain crop growth over multiple generations. Decomposers are an excellent example of such microbial systems, functioning similarly to the biomining species described above, but primarily liberating organic material from dead tissues. This activity is a crucial aspect of bioregenerative life support and will become increasingly important as researchers begin to incorporate crops with significant amounts of inedible biomass into our models for off-world food production. With this in mind, Gilrain et al. incorporated decomposers into their food production system by generating compost to supplement the growth of Beta vulgaris (Swiss chard) in JSC-Mars-1A154. Duri et al. utilized such decomposers to generate compost as a supplement for samples of butterhead lettuce (Lactuca sativa) grown in MMS-1109. Their findings suggested that compost may help to modulate cation release, limiting the phytotoxicity of elements like Al3+ while limiting runoff loss to others like Ca2+ and Mg2+. Complementary studies confirmed that the addition of composted material impacted hydrological parameters of the regolith, further limiting the risk of leaching of potential phytotoxins111.

Lytvynenko et al. made one of the first attempts to assemble an engineered microbiome for lunar regolith using anorthosite as a lunar regolith proxy107,155,156. These studies envisioned the use of this consortium to extract beneficial nutrients from regolith to support plant growth, in this case Tagetes patula (French marigolds). Among these were an isolate from the genus Paenibacillus (sp. IMBG156) which formed biofilms on the surface of sterilized anorthosite particles. In these biofilms, this strain liberated both Ca2+ and Si4+as well as oxidizing Fe (II) to Fe (III), improving plant access to all three of these ions under conditions that would also support plant growth. Pioneering strains like these could be used to begin remodeling regolith in advance of planting facilitating the first round of growth. Other members of this consortium included known plant growth promoting microorganisms Klebsiella oxytoca IMBG26, Pseudomonas sp. IMBG163, P. aureofaciens IMBG164, and Pantoea agglomerans IMV56. This consortium supported T. patula growth in anorthosite improving germination, survival, and growth, most notably allowing plants to flower, which did not occur without the engineered microbiome in anorthosite.

While preliminary, these various lines of evidence support the potential of incorporating a variety of the plant-microbial associations that began with the earliest terrestrial plants. Ultimately, a systems or holobiont approach to RBA which incorporates select microbial cohorts will integrate more efficiently with any bioregenerative life support system at work in an off-world colony. This would replace the existing strategy of the indiscriminate elimination of all microorganisms which has proven remarkably unsuccessful though clearly, further work in this area is required.

“Best practices” for the future of research in regolith-based agriculture

The body of RBA research available to date consists mostly of preliminary plant growth experiments addressing fundamentally basic topics of agricultural science applied to the Moon or Mars. While this provides important groundwork and insights into the potential for RBA, many of these studies, including our own works, still fail to provide a clear picture of the precise procedures capable of providing successful approaches for regolith-based agriculture beyond Earth. In order to be successful, off-world we need to be able to accurately predict crop yield, even under potentially disastrous situations. Yet there is a significant gap between current research and the successful realization of an RBA system with such reliability. We can summarize these gaps into four broad areas for improvement: 1) Regolith simulant preparation, amelioration, and alteration, 2) evaluating plant growth and response, 3) microbial identification, community development, and response, and 4) environmental controls of the experiments themselves.

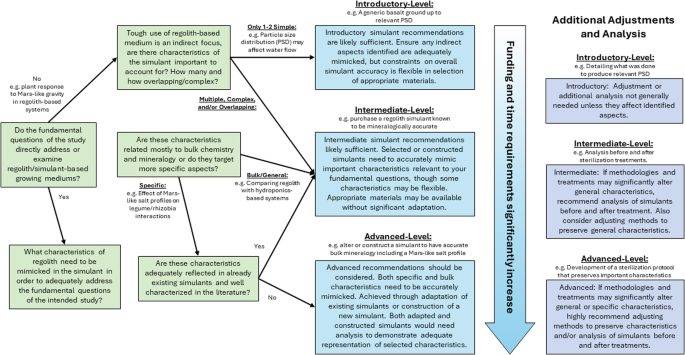

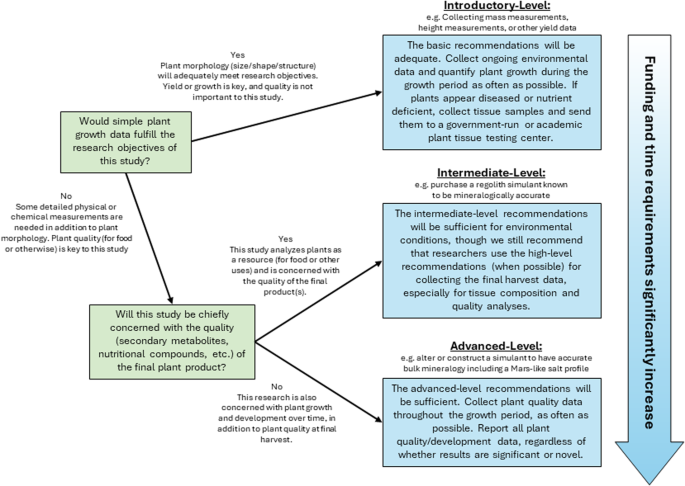

However, providing a tightly controlled environment, making accurate regolith simulants, testing plant physiology and genetics, and assessing microbial status all require specialized knowledge and training, can be very expensive, and the equipment needed is often difficult to access. Depending on access to funding and expertise, it may not be feasible to do all these aspects at the same time in every experiment. We highly recommend collaboration as a solution to this issue; however, this option is not necessarily available in every scenario. To help address the gaps both in knowledge and accessibility, we begin by identifying key knowledge gaps in the form of specific questions. We follow these questions with tiered recommendations for experimental design and reporting of results that will assist in filling these gaps. These tiers (Introductory, Intermediate, and Advanced levels) establish the experimental rigor dedicated to each of the 4 areas and are intended to be deployed in a “mix and match” fashion, permitting researchers to address specific RBA knowledge gaps with their research while meeting certain minimum requirements. The distinctions help guide researchers through a structured progression in their work, ensuring that basic concepts are mastered before more complex, nuanced, or technologically advanced investigations are undertaken.

Introductory

These are foundational research activities designed for new entrants into the field. They focus on basic principles and simple experiments that are critical for understanding the fundamentals of regolith-based agriculture. This level is meant to build a solid base of knowledge and skills.

Intermediate

At this stage, the research delves into more complex interactions within regolith agriculture, such as chemical properties and plant responses. It assumes a certain level of foundational knowledge and aims to expand on that by exploring more detailed aspects of plant growth and soil interaction.

Advanced

This highest level involves sophisticated research methodologies and experiments. It’s aimed at those with a strong background in the field, looking to push the boundaries of current understanding. Advanced recommendations often involve integrating multiple complex factors or innovative technologies to address the challenges of growing plants in regolith.

These tiers are intended to be inclusive, not prohibitive, by providing clear standards and practices for experimental design and publication, that will make it easier for new researchers and their projects to join the RBA community. To better illustrate our intentions and provide some guidance, following this list of recommendations we have also provided a series of decision trees as well as an illustrative case study evaluating the four key areas of RBA questions and their specific tier. Through the act of asking “what is best?” we hope to help establish the current boundaries of our understanding, recommend research practices that bring coherence and an ability to communicate results more effectively in the community, and illustrate examples of some of the ways these recommendations can be applied. Together these key questions, recommendations, and illustrative examples can provide a set of “best practices” intended to help provide greater coherence and focus for RBA research that can begin to fill the gap and bring it to a TRL at which it becomes a reliable component of sustainable off-world agriculture.

Key questions and knowledge gaps

Here is a list of key questions or needs that make up the current knowledge gap of RBA research. This is not an exhaustive list, but a starting point that helps to inform the recommendations that follow. The authors have written this list with their expertise informed by literature and have refined into the questions they deem more pressing. Indeed, some of these questions represent noticeable knowledge gaps which must be addressed before all of our best practices can be implemented as well as questions for which the implementation of the recommended best practices can help provide more coherent answers. Additionally, microbes, plants, and regolith all interact within their environment, thus some overlap exists among questions approached from the perspective of each aspect. This merely underscores the utility of this effort. Even if it were possible to list all the current key questions, the very act of addressing these questions will bring forth more questions all of which will inform the recommendations that follow allowing them to evolve as the knowledge gap is filled. This exercise represents a starting point from which more questions must be asked, research approaches and practices can evolve and knowledge gaps can be filled. Here are specific questions that emerged from this exercise:

Regolith and regolith simulants

Q1. How accurately do regolith simulants currently developed represent actual Regolith?

Motivation: A few disparate studies that evaluate simulant accuracy are available, but most only examine a few simulants and use vastly different approaches for this evaluation. There are also a few reviews that list available simulants for the Moon and Mars covering many simulants (e.g., Duri et al.) but have limited exploration of simulant accuracy to actual regolith109. A more thorough evaluation of developed simulants that includes both a more extensive number of simulants and a thorough evaluation of simulant accuracy would be a valuable resource for understanding current simulant limitations, recommendations in simulant development, and a list from which researchers can select simulants most appropriate for the intended study. Though it is also recognized this represents a significantly challenging endeavor as published data or simulant samples are not always readily accessible.

Q2. What data is needed about actual lunar and Martian regolith to better evaluate regolith fertility and how these be measured by current and future robotic missions?

Motivation: Though we do understand much about lunar and Martian regolith mineralogy and chemistry, certain aspects relevant to agriculture are not well constrained. In particular the amount and bioavailability of plant relevant nutrients and phytotoxins, direct measurements of soil pH and salinity, the composition and geochemistry of poorly understood components of lunar and Mars regolith (for example the amorphous portion of Mars regolith and other surface materials), presence of minable in situ resources of fertilizer components not available in the regolith directly. Many of these aspects are difficult to apply to robotic exploration and thus have limited or no data available, but advances in engineering and technology have increased and will continue to increase the ability to measure such characteristics.

Q3. What non-regolith materials may also have agricultural applications and what data is needed to understand potential contribution to viability and fertility

Motivation: This is a continuation of question 2, but applied to other surface materials that could be processed or applied as well. For example, acidic-sulfates on Mars could help regulate the pH of soils or hydroponic fluid, however to adequately understand the viability of such techniques we need data from actual surface materials to better characterize them and simulants that accurately mimic their characteristics in order to test them.

Q4. What agriculturally relevant characteristics are lacking in available regolith simulants and are there viable techniques that can accurately replicate them at appropriate scales?

Motivation: If the comparisons suggested in question 1 can be more thoroughly established, that leads to consideration for simulants applied to RBA studies and what characteristics are not mimicked that may have important agricultural implications. To what degree is it possible to adapt current simulants or develop new simulants that do mimic these characteristics. It is also important to realize that the degree to which this question can be answered is limited by our current understanding of actual regolith and as that knowledge increases it is useful to reevaluate current simulants.

Q5. Which nutrient extraction methods are best correlated and calibrated for regolith materials, or are any of them?

Motivation: Nutrient extraction is used to evaluate not just the amount of nutrient in soil, but the amount of plant extractable nutrient157. These tests are not based on direct measures but rather known correlations among certain extracting materials and plant uptake that have been calibrated to fertilization recommendations. However, this correlation is not very consistent among different soil types as the extractants can behave very differently in differing soil conditions, thus different locations often select tests most applicable to major soils in their region. However, such correlations and calibrations have not been established for regolith simulants thus any nutrient or fertility evaluations may or may not provide viable results. A study that examines different extraction methods on different simulants and if they correlate with plant uptake or not is needed for such fertility tests to be accurately evaluated and for resulting recommendations for increasing fertility to be viable.

Q6. What effects do sterilization, and other pre-processing techniques, have on Regolith Simulant composition? How effective are these techniques at sterilizing regolith simulant materials?

Motivation: There are many situations in which it may be useful to sterilize regolith simulants (or at least attempt to) in order to provide a sterile medium for which to begin a study. However, many of these techniques can drastically alter mineral materials. The potential for alteration will differ among mineral type and sterilization method, but we are not aware of any studies that directly evaluate these alterations and the implications on simulant composition and its relevance to actual regolith. It is also difficult to truly sterilize soil-materials and it would be useful to examine the effectiveness of a method compared to the degree of alteration it induces. Though sterilization would be among the most commonly applied processing techniques expected, the same concerns hold true for any processing applied to a simulant to prepare it for a particular study.

Q7. How well do the many ameliorative techniques proposed improve the regolith fertility and how variable is this success among different regolith types?

Motivation: There are many approaches that have been proposed for developing viable materials from regolith. For example, rinsing Martian regolith to remove salts including perchlorates. However, testing such techniques on a Martian regolith simulant that does not contain salts would provide completely useless results. But even simulants that accurately represent Mars regolith salinity would need approaches and evaluations that are comparable among studies or studies that examine multiple simulants. This overall concept holds true for any ameliorative technique attempted: i.e., first and foremost such studies must use a simulant that accurately mimics the relevant characteristics seeking to be ameliorated, and even when that is the case comparison to other studies or among multiple simulants allows provides a more broadly applicable ameliorative solution.

Q8. How does exposure to the experimental conditions alter regolith simulants, how are the alterations evaluated and what implications does this have for actual regolith and how is that evaluated?

Motivation: Similar to the alterations that can be induced from processing techniques referred to in question 6, the alterations that occur as a result of the experiment are also important, though they depend on the intent of the study. However, as weathering or alteration of mineral materials can be slow these changes may be subtle (though not insignificant) and commonly applied techniques (like XRF or XRD) may not be able to measure some changes that are important for plant response. However, XRF and XRD are highly useful in that (partly because they are so common) can provide results more comparable among different studies while techniques more sensitive to small alterations may be more limited in their comparability. Simulants (and indeed most growing mediums) can be highly heterogeneous and thus insufficient replication or sample size can limit the ability to detect patterns. Thus a combination of techniques and adequate sample size are important to consider in determining how to measure changes in simulant characteristics.

Plant response to regolith-based substrates

Q9. In what ways are plant tissues chemically affected as a result of being grown in regolith or regolith simulant, and how might this affect edible and non-edible yield and quality. Which tissues are most and least affected by plant growth in regolith or regolith simulant?

Motivation: Photosynthesis is inhibited158 and plant morphology and physiology are affected159 by heavy metals, so both ultimate yield and plant quality varies depending on the elements (and elemental forms) taken up by plants. However, plant translocation of elements is complex, and depends on plant species, environmental content of elements, oxidation/reduction potential, pH, and other factors. Therefore we must explore these effects in regolith to understand how regolith may affect plant and human health in the long term.

Q10. When grown in regolith or regolith simulant based growing mediums, in what ways would plants alter the medium? How might root exudates alter regolith properties over the short-term and long-term? How might regolith simulants alter plants’ relationships with root-colonizing (especially root nodulating) microorganisms, and what key factors could cause these effects?

Motivation: We have established that soil quality has direct effects on plant physiology, growth, and quality, however plants also have reciprocal effects on the rhizosphere. Plant roots produce exudates that contain metabolites and a wide variety of compounds, which alter chemical and physical properties of soil, help maintain and support microbes, and have critical impacts on long-term plant health160,161. Therefore, to understand the long-term effects of using regolith for agriculture, we must elucidate how regolith may change over time as a result of agricultural use.

Q11. What avenues are most appropriate to increase organic carbon content in regolith or regolith simulant based growing mediums? What stable organic amendments are most effective at both supplying organic carbon for plants and improving the texture of the substrate for supporting plants? Are the avenues actually helpful at improving the viability of the mediums?

Motivation: Soil carbon is required for plant and microbial growth, however its availability in the soil is affected by soil amendments, root exudates, microbial activity, and other factors162. Therefore we must find methods to supply enough carbon to regolith to meet the needs of plants and the rhizosphere microbiome, and understand how organic amendments affect RBA.

Q12. Do current soil nutrient extraction tests applied to regolith or regolith simulants correlate sufficiently with plant uptake to determine reliable fertilization recommendations?

Motivation: fertilizer recommendations are made using soil/nutrient testing; however these tests may not provide accurate or adequate fertilizer recommendations when used on regolith. Therefore, we must examine whether these tests are accurate and work to optimize them for regolith applications, such as by using regolith simulants with known chemical properties to calculate the ideal dose of each nutrient.

Q13. As we consider RBA compared to hydroponic methods, what crop species may be particularly well-suited for RBA? Do these crops fulfill the needs of astronauts, or is further crop selection necessary? Are these crops that meet current crop selection criteria feasible to use in RBA, when other considerations (such as the need for food processing) are considered?

Motivation: Multiple studies have established a consensus of logical plant choices that fill nutrient requirements for future off-world agricultural efforts131. However, these are based on the assumption of fully hydroponic systems, and use of regolith may alter what considerations are most relevant. Therefore we must reconsider crop selection needs and reevaluate whether these crop lists are usable with RBA.

Microbial community identification and response to regolith-based substrates

Q14. What is the endogenous microbial composition of the common regolith simulants?

Motivation: A basic understanding of the existing microbiome of regolith simulants would help distinguish between substrate effects and microbial ones. As sterilization of large amounts of regolith simulants for scale-up studies is not possible, identifying these microbes becomes an important step moving forward.

Q15. Does this endogenous population significantly alter these simulants post-acquisition?

Motivation: Over time, the endogenous microbiome of the simulants may alter regolith composition. In other words, regolith simulants, stored under Earth conditions, will age differently than regolith on Mars or the Moon. Although such changes are likely to be slow it should still be part of our consideration as regolith becomes soil, in part, through the actions of microorganisms.

Q16. Do these simulants contain plant growth promoting microorganisms?

Motivation: The potential that plant growth promoting bacteria are already in regolith simulants may be impacting plant growth studies already and a baseline needs to be established.

Q17. How well can plant-associated microorganisms be cultivated in regolith?

Motivation: At present, there is no information on how the rhizosphere and phyllosphere of plants grown in regolith simulants may vary from controls grown in more traditional soil substrates, or how this affects plant-associated microorganisms. Low nitrogen levels in both Martian and lunar simulants, for example, may select for nitrogen-fixing microbes from the surroundings, even if they are not already present in the simulant. Understanding how these microbiomes vary as a function of substrate is crucial to implementing a cultivation program that utilizes microorganisms.

Q18. Does regolith alter the phenotypic behavior of plant-associated microorganisms?

Motivation: Closely related to Question 4, not only may there be differences in microbiome composition, but the phenotypes of specific microorganisms may vary based on regolith compositions. For example, the low nitrogen, high iron concentrations found in Martian regolith and its simulants may alter the behavior of non-nodulating nitrogen-fixing bacteria.

Q19. What challenges does regolith pose to the extraction and identification of organic compounds for evaluating the chemical composition of the rhizosphere?

Motivation: Regoliths (and simulants) are composed of materials which tend to complicate the extraction of organic compounds. This can complicate analysis of the rhizosphere chemicals both from plants as well as bacteria. Refined protocols are needed for this process for the different stimulants.

Q20. What challenges does regolith pose to the extraction and identification of bacteria or environmental DNA for evaluating the chemical composition of the rhizosphere?

Motivation: The challenges associated with the extraction of organics from the simulants will be similar for the extraction of DNA and possibly intact bacteria. This would represent an extra challenge for metagenomics and other microbial characterization approaches. Refined protocols are required for this process for the different simulants.

Q21. How does the microbiome of adjacent surfaces influence the endogenous microbiome of regolith (and simulants)?

Motivation: Off world-agriculture, regardless of its site, will occur in highly enclosed spaces for the foreseeable future. Such environments are prone to significant mixing of microbial populations between the inhabitants (human, plant, etc.) as well as the surfaces they encounter. Migration of microorganisms to regolith (and simulants) from biotic and abiotic sources in the environment could be an important source of both mutualistic as well as pathogenic cohorts. Indeed, prior studies have already identified migration from the human microbiome into the rhizo- and phyllosphere of plants aboard the ISS.

The growth environment

Q22. What is an acceptable balance of atmospheric conditions (composition, atmospheric pressure, humidity, etc.) for off-world closed food systems in a hypogravity environment such as the Moon or Mars? What considerations are needed for the interactions among plants, microbes, regolith, crew members, and the outside environment?

Motivation: The conditions conducive for agriculture in off-world systems must be investigated in order for researchers to, 1) create accurate cost projections, 2) to methods for maximizing yield, and 3) to enable engineers to design the systems that will support these crops. Researchers on Earth must also consider the air environment, especially the carbon dioxide concentration and volatile organic compounds, when undertaking analog experiments that include plants.

Q23. Similar to the aforementioned atmospheric conditions, which irrigation strategies are most effective for maintaining optimal hydration for growing plants in regolith simulant? What trade-offs exist for each irrigation strategy, and how can the effects of these trade-offs be minimized?

Motivation: Irrigation can have drastic effects on plant growth and development, and optimizing irrigation strategies for RBA will be vital. Water will be a limiting resource in space environments, making water conservation a high priority. Furthermore, the leaching proprieties of water should also be considered. Heavy or low-flow systems, systems that will only affect the rooting zone or the bulk area of the substrate, and strategies that are either bottom-up or surface sprays will have different impacts on nutrient leaching rates. Each approach will have different effects on the overall nutrient accessibility to the plants and will alter the substrate’s pH, thus influencing microbiome recruitment.

Q24. What sustainable management practices (e.g., no-till vs conventional till, or other cultural practices) applied to terrestrial agriculture may also be applicable to RBA? What are the direct and indirect effects of these management practices when applied to RBA?

Motivation: Thus far, no study has evaluated the potential benefits of conventional agriculture practices in RBA systems. Tilling is an excellent example as it may be a necessary strategy for lunar and Martian agriculture due to the low granulometry of each substrate. One downside of tilling is that nitrogen-fixing bacteria are exposed by revolving the lower tiers of the substrate, and this exposure could cause microorganism death, which would threaten the balance of the nitrogen cycling system. As tilling may be an early strategy for planting seeds in an RBA scenario before a microbiome is introduced, further studies are necessary to use conventional agriculture techniques and evaluate their transferability benefits to RBA systems. Other management practices must be explored to identify areas for improvement in RBA. Furthermore, research should prioritize practices that are realistic and feasible for use in real off-world settings.

Q25. What technology advancements would need to be developed or adapted in order to create these systems and how might multiple technologies be integrated while minimizing the risk of system failure?