P4HB maintains Wnt-dependent stemness in glioblastoma stem cells as a precision therapeutic target and serum marker

Introduction

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) stands as a formidable challenge within neuro-oncology, primarily due to its aggressive nature and the limited efficacy of existing treatments [1,2,3]. The median survival rate for GBM patients remains critically low, underscoring an urgent need for innovative therapeutic strategies [4]. Recent advancements in targeted therapies have highlighted the potential of precision medicine to offer more tailored treatment options, improving patient outcomes [5]. The relentless progression of GBM is significantly driven by glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs), which are central to tumor recurrence and resistance to therapies like temozolomide (TMZ) and radiotherapy [6]. This has spurred interest in GSCs as critical targets for therapy, with the goal of eradicating these cells to prevent tumor regrowth and resistance [7,8,9].

Identifying robust biomarkers that precisely target GSCs is crucial, as they facilitate the development of targeted therapies and enable the monitoring of treatment responses and disease progression [10, 11]. Serum biomarkers are particularly desirable in clinical settings due to their non-invasive nature, making them ideal for early detection and screening [12]. The use of established tumor markers such as PSA for prostate cancer [13] and CA-125 for ovarian cancer [14], which have significantly enhanced clinical management. Current research into GBM blood biomarkers has identified several promising candidates, although none are yet fully established for clinical use. Proteins such as IGFBP-2, YKL-40, and MMP-9 have been identified in peripheral blood and glioma tissue [15], marking progress in this field.

P4HB, known as prolyl 4-hydroxylase subunit beta, plays a critical role in protein folding within the endoplasmic reticulum and is implicated in various cellular stress responses such as oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress [16, 17]. The secretory nature of P4HB [18] suggests its potential usefulness as a biomarker, which has drawn our interest. Its significance extends across numerous diseases, influencing tumor progression, treatment responses, and prognosis in cancers like prostate cancer, bladder tumor, and breast tumor by affecting tumor heterogeneity, and medication sensitivity [19]. In addition, P4HB is involved in key pathways such as cell proliferation, migration, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, often interacting with other molecular chaperones to promote cancer progression [20]. However, the specific roles and mechanisms of P4HB in GBM and its association with GSCs are less understood.

GBM represents the most severe form of glioma, classified as Grade IV according to the World Health Organization (WHO) grading system, which categorizes gliomas based on their malignancy and growth rate [21]. This classification highlights the significant challenges in treating GBM, attributable to its highly infiltrative nature and genetic heterogeneity. Treatment complexity is further exacerbated by the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which prevents more than 98% of small-molecule drugs and all macromolecular therapeutics from accessing the brain [22]. TMZ is the current standard chemotherapeutic agent for GBM but is often met with drug resistance, leading to fatal outcomes [23]. Developing new drugs for GBM is particularly challenging, candidates that perform well in other tumor types often fail in GBM due to its unique pathological environment [24]. In addition, de novo design and evaluation of drug candidates specific to GBM are burdened with high costs, lengthy development periods, and low success rates. Drug repurposing presents a promising strategy to potentially expedite the development of tumors [25]. However, the specific targeting requirements of GBM necessitate drugs that not only engage the correct molecular targets but also effectively cross the BBB.

In this study, we first evaluated the correlation of P4HB with patient therapy outcomes before exploring its potential as a therapeutic target and diagnostic marker for GBM.

Results

P4HB enrichment in GSCs associated with stemness and poor prognosis

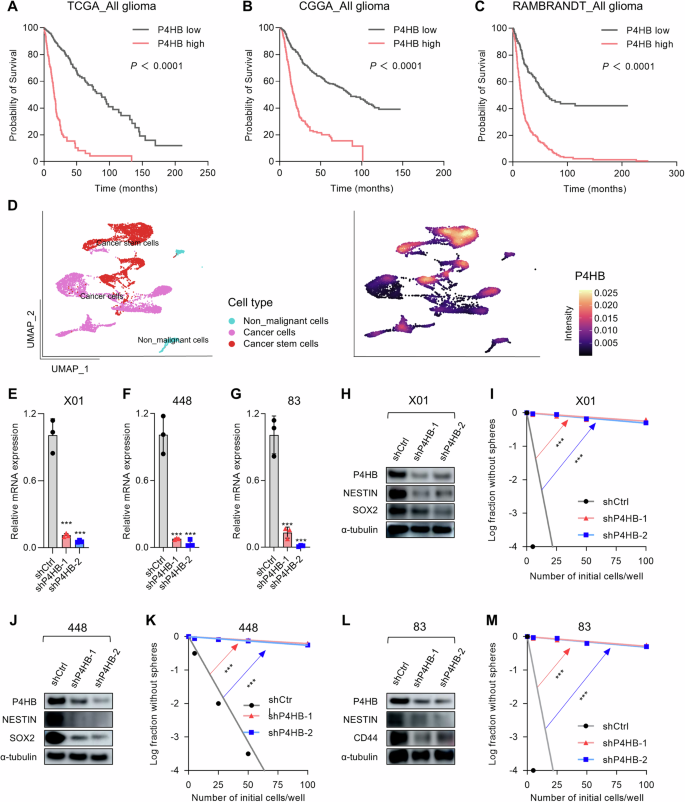

To determine whether P4HB expression is related to clinical prognosis in GBM, we analyzed data from the TCGA, CGGA, REMBRANDT, and CPTAC datasets. The results demonstrated that P4HB is highly expressed in tumor tissues compared to normal tissues both in RNA and protein levels (Supplementary Fig. S1A–E), and its high expression correlates with poor survival in patients (Fig. 1A–C). To better understand the expression pattern heterogeneity within the GBM tissue, a GBM single-cell RNA sequencing data mining was performed using a reported dataset [26]. We categorized the single-cell RNA sequencing dataset into three subsets: non-malignant cells, cancer cells, and cancer stem cells. Data revealed that P4HB expression is significantly higher in cancer stem cells compared to other cell subsets (Fig. 1D). Quantification of expression levels across clusters further demonstrated that P4HB is predominantly expressed in the GSCs cluster (cancer stem cell cluster, Supplementary Fig. S1F). According to the significant enrichment of P4HB in the cancer stem cell cluster, we further investigated its correlation with well-established stemness markers in multiple data portals, including NESTIN, CD44, CD15, and CD133 [6, 8, 9]. These results demonstrated a strong positive correlation between P4HB and the stemness markers, further supporting that P4HB could be a specific stem cell target (Supplementary Fig. S2).

A–C Kaplan–Meier survival curves for patients with glioma from the TCGA, CGGA, and REMBRANDT datasets, stratified by high and low expression of P4HB. P-values were calculated using the log-rank test and Wilcoxon test. D UMAP plot showing the clustering of different cell types within the GBM patients’ tissues, and the expression levels of P4HB across different cell clusters. E–G Relative mRNA expression levels of P4HB in X01, 448, and 83 GSCs, respectively, were measured by qRT-PCR after shRNA-mediated knockdown of P4HB. Data are presented as means ± SD, n = 3, ***P < 0.001, t-test. H Western blot analysis of P4HB, NESTIN, and SOX2 protein levels in X01 GSCs after shRNA-mediated knockdown of P4HB, α-tubulin was used as a loading control. I Limit-dilution assay for sphere-forming capacity in X01 GSCs following shRNA-mediated knockdown of P4HB. Log fraction without spheres is plotted against the number of initial cells per well. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, t-test. J Western blot analysis of P4HB, NESTIN, and SOX2 protein levels in 448 GSCs after shRNA-mediated knockdown of P4HB, α-tubulin was used as a loading control. K Limiting dilution assay for sphere-forming capacity in 448 GSCs following shRNA-mediated knockdown of P4HB. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, t-test. L Western blot analysis of P4HB, NESTIN, and CD44 protein levels in 83 GSCs after shRNA-mediated knockdown of P4HB, α-tubulin was used as a loading control. M Limiting dilution assay for sphere-forming capacity in 83 GSCs following shRNA-mediated knockdown of P4HB. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, t-test.

To understand whether the highly expressed P4HB is associated with the GSCs stemness, we constructed the P4HB knockdown lentiviral vectors and verified the robust silencing for P4HB in well-characterized patient-derived GSCs [27, 28], including proneural type X01, 448, and mesenchymal type 83 (Fig. 1E) [29]. GSCs are highly proliferating self-renewal cells and exhibit typical stem cell characteristics such as sphere-forming ability, reflecting the stemness. To this end, we initially evaluated the sphere formation capacity using a limiting dilution assay. The results indicated that knockdown of P4HB significantly diminished the sphere-forming ability across all three glioma stem cell lines (Fig. 1I, K, M). Data also showed P4HB knockdown led to a decrease in GSCs markers [27], including NESTIN in any of the three GSCs, and in the proneural GSCs lines X01 and 448, SOX2 expression was decreased, while in the mesenchymal GSCs line 83, CD44 expression showed a significant decrease (Fig. 1H, J, L). These data suggested the P4HB expression may have a critical role in maintaining GSCs stemness, thereby may function in occurrence or resistance, and consequently, potentially associated with patients’ poor prognosis.

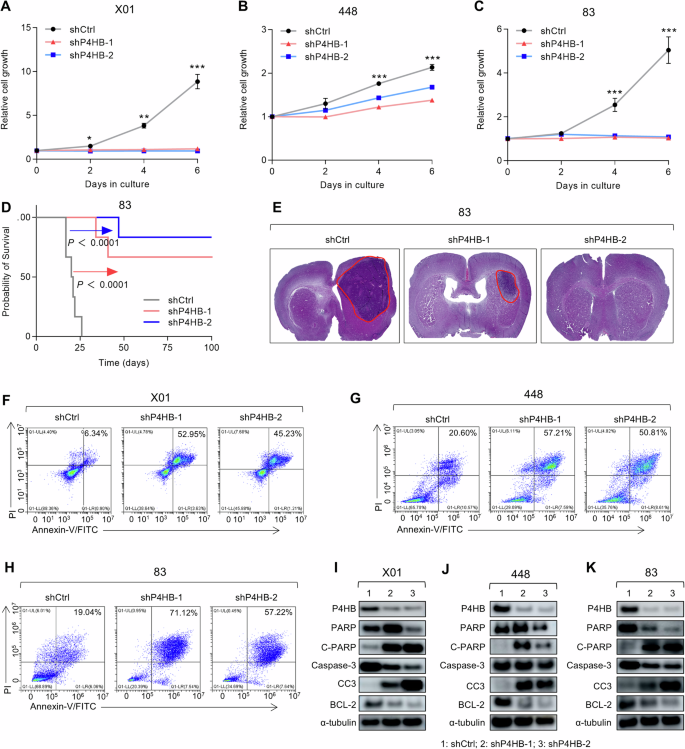

P4HB inhibition impedes GSCs progression and oncogenicity by inducing apoptosis

To evaluate whether interfering with P4HB expression can limit GSCs progression, we first assessed the proliferation of GSCs under P4HB knockdown conditions. Data collected from X01, 448, and 83 GSCs lines showed significant growth inhibition using two separate shRNAs (Fig. 2A–C). To further investigate whether reduced P4HB expression in GSCs can limit tumor progression in vivo, we employed a P4HB knockdown 83 GSCs-transplanted mice model. Results indicated significant survival prolongation in both shRNA treatment groups, with over half of the transplanted mice surviving beyond 100 days (Fig. 2D). Stable body weight in the P4HB knockdown groups, combined with the results from imaging luciferase-labeled GSCs, further suggests that silencing P4HB is sufficient to impede GSCs progression in vivo (Supplementary Fig. S3). The brain tissue H&E staining also demonstrated obvious tumor size reduction compared with the shRNA control vector, which indicates that P4HB may be possible as a therapeutic target (Fig. 2E). Given the observed inhibition of GSCs growth, we further examined whether this inhibition was associated with programmed cell death. Flow cytometry analysis for Annexin-V and PI co-staining confirmed a large Annexin-V staining positive cell population increase, suggesting the induction of apoptosis in all three GSCs lines (Fig. 2F–H). Elevated protein expression levels of cleaved PARP and cleaved Caspase-3, along with reduced BCL2 levels, further supported the conclusion that downregulation of P4HB effectively induces apoptosis in GSCs, thereby limiting their progression (Fig. 2I–K). Collectively, these data demonstrate that interference with P4HB expression is sufficient to inhibit GSCs progression by inducing apoptosis.

A–C Cell proliferation assay for X01, 448, and 83 GSCs infected with shCtrl, shP4HB-1, and shP4HB-2 lentiviral vectors. Data are presented as means ± SD, n = 3, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, t-test. D Kaplan–Meier survival curves of mice implanted with 83 GSCs infected with shCtrl or shP4HB lentivirus (n = 6 in each group, 1 × 104 GSCs/mouse), P < 0.0001, log-rank test. E H&E staining of the whole brain slides derived from the mice implanted with 83 GSCs infected with shCtrl or shP4HB lentivirus. F–H Flow cytometry analysis of Annexin V/PI staining for cellular apoptosis analysis of X01, 448, 83 GSCs infected with shCtrl or shP4HB lentivirus. I–K Western blot analysis of PARP, C–PARP, P4HB, Caspase-3, CC3, and BCL2 protein levels in X01, 448, 83 GSCs infected with shCtrl or shP4HB lentivirus, α-tubulin was used as a loading control.

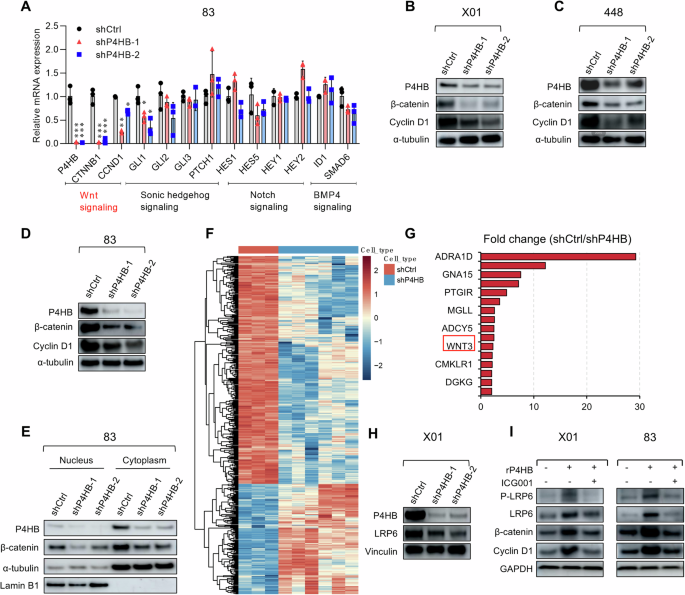

P4HB maintains GSCs stemness via the Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway

Further investigation into the regulatory mechanism of P4HB is crucial for understanding its role in GSCs. After validating that P4HB can induce GSCs apoptosis, we moved to investigate the response to P4HB knockdown. The stemness of GSCs is driven by multiple key regulation axes, such as Wnt, Sonic Hedgehog, Notch, and BMP [30]. Representative regulation key players from these pathways are first verified at the mRNA level. Data demonstrated that CTNNB1 and CCND1, which are closely related to the Wnt signaling pathway, were significantly decreased following P4HB gene silencing with shRNAs, showing more than a 10-fold reduction of CTNNB1 (Fig. 3A). Cyclin D1, coding by the CCND1 gene, is a cell cycle protein, is a downstream effector of the Wnt signaling pathway, and is associated with cancer development [31]. P4HB knockdown-induced decreases in β-catenin and Cyclin D1 and were confirmed at the protein expression level in both proneuronal and mesenchymal GSCs (Fig. 3B–D). The translocation of β-catenin from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, where it interacts with transcription factors to initiate the transcription and translation of target genes, is a hallmark of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. In this regard, we performed nuclear-cytoplasmic separation experiments on 83 GSCs with P4HB knockdown. Data showed a notable decrease in nuclear β-catenin protein levels after P4HB knockdown, while cytoplasmic β-catenin levels were only slightly affected, suggesting that P4HB may involve in the nuclear import of β-catenin (Fig. 3E).

A Relative mRNA expression levels of the indicated signaling pathways in 83 GSCs infected with shCtrl or shP4HB-1 and shP4HB-2 lentiviral vectors. Data are presented as means ± SD, n = 3, t-test. B–D Western blot analyses of P4HB, β-catenin, and Cyclin D1 protein levels in X01, 448, 83 GSCs infected with shCtrl or shP4HB-1 and shP4HB-2 lentivirus, with α-tubulin used as a loading control. E Western blot analysis of P4HB and β-catenin in isolated nuclear or cytosolic lysates from 83 GSCs infected with shCtrl or shP4HB-1 and shP4HB-2 lentivirus. Lamin B1 and β-actin were used as markers for the nucleus and cytoplasm, respectively. F Heatmap analysis of different gene expression clusters in X01 shCtrl and shP4HB GSCs by RNAseq analysis. G Differentially expressed genes were mapped by fold change between the shCtrl and shP4HB groups. H Western blot analysis of P4HB and LRP6 protein levels in X01 GSCs infected with shCtrl or shP4HB-1 and shP4HB-2 lentivirus, Vinculin was used as a loading control. I Western blot analysis of β-catenin, CyclinD1, and LRP6, P-LRP6 protein levels 3 in X01 and 83 GSCs treated with 10 μM ICG001, 25 ng/ml recombinant P4HB protein (rP4HB). GAPDH was used as a loading control.

To further elucidate the P4HB involving mechanisms and gain a more comprehensive understanding of the signaling networks regulated by P4HB silencing, we performed transcriptome sequencing of X01 GSCs with P4HB knockdown. Analysis revealed notable changes in Wnt3 (Fig. 3F, G), one of the major Wnt family signals. Data are also validated through quantitative RT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. S4A, B). Considering that P4HB can be secreted through exosomes [18] and potentially interact with other membrane proteins, while the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) is a receptor protein of Wnt, and its response to Wnt is involved in the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling [32], we hypothesize that P4HB may regulate the activation and transmission of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway via the LRP ligand Wnt3. Given that one of the previously identified ligands for LRP6 is Wnt3a [33], which shares high homology with Wnt3, we verified the expression of LRP6 under the P4HB knockdown condition and found a LRP6 decrease (Fig. 3H and Supplementary Fig. S4C). We further confirmed the involvement of the P4HB in LRP6-Wnt/β-catenin axis by utilizing the Wnt/β-catenin inhibitor ICG001 [34]. Moreover, when recombinant P4HB protein was given to X01, 448, and 83 GSCs, the stemness markers of GSCs including NESTIN, CD44, and SOX2 were up-regulated, and the upregulation of Cyclin D1, β-catenin, LRP6, and phosphorylated LRP6 (P-LRP6) was observed. However, when the Wnt/β-catenin inhibitor ICG001 was supplied to the recombinant P4HB-treated GSCs, the stemness markers of the GSCs decreased (Supplementary Fig. S4D–F). Moreover, upon treatment with the Wnt/β-catenin inhibitor ICG001, the upregulation of Cyclin D1, β-catenin, LRP6, and P-LRP6 driven by the recombinant P4HB protein treatment was suppressed (Fig. 3I). These findings confirm that P4HB activates the Wnt/β-catenin associated signaling pathway, indicating the existence of a P4HB-LRP6-Wnt/β-catenin axis.

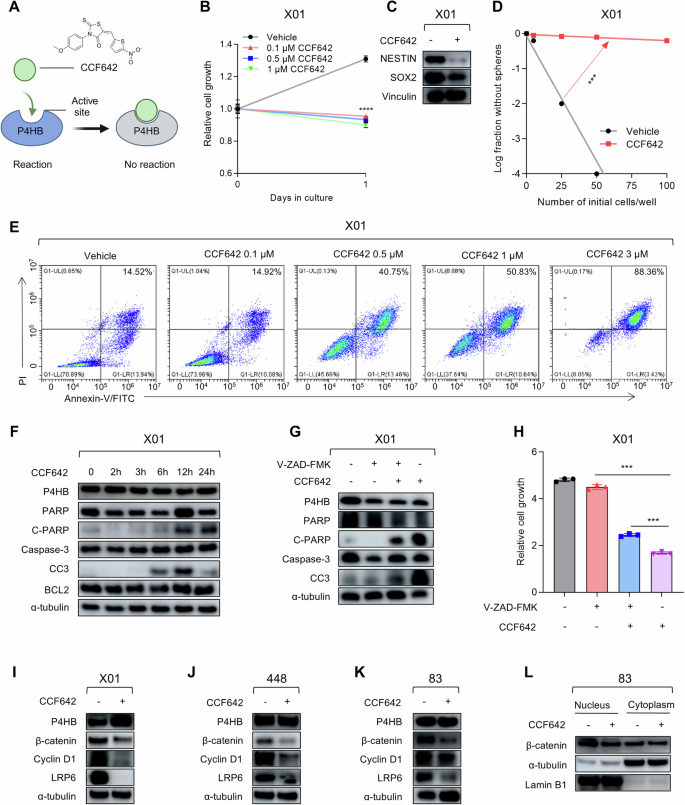

Pharmacological inhibition of P4HB triggers apoptosis in GSCs with Wnt/β-Catenin signaling response

Given that P4HB gene silencing greatly inhibits the progression of GSCs, we wonder whether small molecules can achieve pharmacological inhibition and explore the potential in Wnt/β-Catenin signaling intervention. CCF642, a small molecular inhibitor of P4HB, previously demonstrated potent efficacy in inducing apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells in vitro by binding to the CGHCK motif of the P4HB peptide thus inhibiting its reductase activity (Fig. 4A) [35]. In our study, we observed an obvious cell proliferation inhibition response in X01, 448, and 83 GSCs to the treatment of CCF642, with significant reductions in cell growth at the concentration starting from 0.1 µM (Fig. 4B, Supplementary Fig. S5A, B). However, CCF642 exhibited a narrow therapeutic window, as it inhibited the proliferation of normal human astrocytes (ASCR) at a concentration of 1 μM (Supplementary Fig. S5C). The stemness markers also showed a decrease in response to the CCF642 treatment (Fig. 4C, Supplementary Fig. S5D). At a concentration of 0.5 µM, CCF642 also markedly decreased the sphere formation ability in X01, 448, and 83 GSCs, suggesting inhibition of GSCs stemness (Fig. 4D, Supplementary Fig. S5E, F). Also, flow cytometry data suggested a dose-dependent Annexin-V positive population increase, suggesting apoptosis induction (Fig. 4E, Supplementary Fig. S5G). Further investigations confirmed that CCF642 activates classical apoptotic effectors, including Caspase-3 and PARP, in a time-dependent manner, leading to apoptosis (Fig. 4F, Supplementary Fig. S5H). The application of the broad-spectrum Caspase inhibitor V-ZAD-FMK also significantly mitigated apoptosis induced by CCF642 (Fig. 4G, H, Supplementary Fig. S5I, J), and Z-DEVE-FMK (Caspase-3 inhibitor) [36] also demonstrated a partial recovery of cell death. In contrast, other inhibitors for cell death-associated pathways such as dimethyl fumarate (Pyroptosis inhibitor) [37] and ferrostatin-1 (Ferroptosis inhibitor) [38] did not show an obvious impact on cell death, suggesting the primary CCF642-induced cell death mainly attributed to caspase-dependent apoptosis, instead of pyroptosis or ferroptosis (Supplementary Fig. S6). Similar to the effects of P4HB gene silencing, treatment with CCF642 reduced the expression of Cyclin D1, LRP6, and β-catenin in all three GSCs lines (Fig. 4I–K), and the decreased nucleus located β-catenin (Fig. 4L).

A Schematic illustration of CCF642 inhibiting P4HB reductase enzyme activity by sheltering the active enzyme site. B Cell proliferation assays for X01 GSCs treated with different doses of CCF642 after 24-h treatments. Data are presented as means ± SD, n = 3, ***P < 0.001, t-test. C Western blot analysis of stemness markers NESTIN and SOX2 protein level in X01 GSCs after treatment with 1 μM CCF642 for 48 h, Vinculin was used as a loading control. D Limit-dilution assay for sphere-forming capacity in X01 GSCs treated with 0.1 μM CCF642. ***P < 0.001, t-test. E Flow cytometry analysis of cellular apoptosis of X01 GSCs treated with different doses of CCF642 by Annexin V/PI staining. F Western blot analysis of PARP, C-PARP, P4HB, Caspase-3, CC3, and BCL2 protein levels in X01 GSCs treated with 1 μM CCF642 under different time points, α-tubulin was used as a loading control. G Western blot analysis of PARP, C-PARP, P4HB, Caspase-3, and CC3 protein levels in X01 GSCs treated with 1 μM CCF642 in the presence of 25 μM V-ZAD-FMK, α-tubulin was used as a loading control. H Cell proliferation assays for X01 GSCs treated with 1 μM CCF642 along with apoptosis inhibitor V-ZAD-FMK (25 μM). Data are presented as means ± SD, n = 3, ***P < 0.001, t-test. I–K Western blot analysis of P4HB, β-catenin, CyclinD1, and LRP6 protein levels in X01, 448, 83 GSCs treated with 1 μM CCF642, α-tubulin was used as a loading control. L Western blot analysis of β-catenin protein level in fractionated nuclear or cytosolic lysates from 83 GSCs treated with 1 μM CCF642, α-tubulin, and LaminB1 was used as loading control, respectively.

These results indicate that both small molecule inhibition and gene silencing of P4HB can effectively inhibit the GSCs progression and β-catenin signaling pathway response, offering potential strategies for intervening in GSCs.

P4HB is targetable by securinine repurposing and may act as a blood diagnostic biomarker for GBM progression

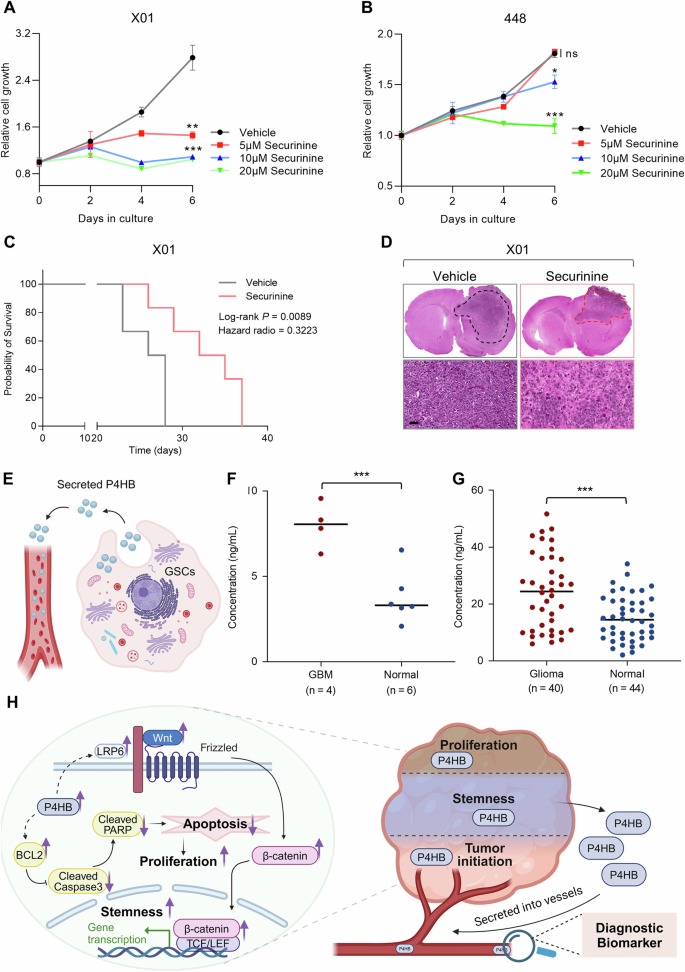

Data inspired us to further investigate P4HB intervention potential. Drug repurposing represents a strategy that finds new medical uses for existing drugs, offers a strategy to reduce development time and costs, lower risks, and potentially address unmet medical needs [25]. This approach could enhance the translation of P4HB-targeted therapies. To this end, we did a comprehensive literature review with the aid of the Human Protein Atlas database and literature searching engines and identified securinine and bacitracin as potential inhibitors [39, 40]. Securinine has been approved by the NMPA (H32023548) for neurological disorders, including poliomyelitis and facial paralysis [41]. In contrast, bacitracin, previously approved by the US FDA, was withdrawn from the market due to significant safety concerns, such as nephrotoxicity, and the availability of safer therapeutic alternatives [42]. Further investigation of drug molecular weights suggested that securinine (217.26 Da) is more likely to penetrate the blood-brain barrier compared to bacitracin (1408.67 Da). Therefore, securinine was selected for performance evaluation. Data from both 448 and X01 GSCs showed significant growth inhibition under a range of securinine treatments (Fig. 5A, B). Moreover, securinine consistently inhibits GSCs proliferation across a broader range of GSCs (Supplementary Fig. S7A, B), inhibition of GSCs proliferation was also observed across a wide range of securinine doses in different GSCs, demonstrating its potential for further experiments (Supplementary Fig. S7C–F). Encouraged by these in vitro results, we proceeded with in vivo evaluation using a patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model, wherein X01 GSCs were implanted into the brains of nude mice. Given that securinine is clinically used for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and poliomyelitis by activating GABA receptors, its safety and oral availability suggest that intraperitoneal injection is suitable for proof-of-concept experiments. The PDX model was established by implanting patient-derived X01 GSCs into nude mice, following our well-established protocol [27]. After 10 days post-implantation, mice were treated with either PBS (Control) or 15 mg/kg of securinine via intraperitoneal injection, five days a week for three consecutive weeks. Survival analysis showed a significant extension of survival in the securinine treatment group compared to the vehicle group (Fig. 5C). In addition, H&E staining of brain sections revealed marked inhibition of tumor progression in the securinine treatment group (Fig. 5D). It’s worth noting that securinine exhibited relatively high biocompatibility as determined by hematological parameters including blood cytotoxicity and liver or kidney burden (Supplementary Fig. S8A–J). Moreover, core pro-inflammatory cytokines such as Il-1β, Il-6, and Tnfα were measured in the liver and kidney to assess inflammatory responses, showing no significant elevation (Supplementary Fig. S8K, L). Moreover, histochemical staining results also revealed no obvious damage in major organs after securinine treatment (Supplementary Fig. S8M, N). Considering the securinine was reported have antitumor potential in a variety of tumors and can across the blood-brain barrier [43], these data indicate the potential of securinine as an anti-GBM agent with translational promise.

A, B Cell proliferation assays for X01 (A) and 448 (B) GSCs treated with P4HB inhibitor securinine in a dose-dependent manner. Data are presented as means ± SD, n = 4, no significant (ns), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, t-test. C Kaplan–Meier survival curves of mice implanted with X01 GSCs treated with Control or securinine (n = 6 in each group, 1 × 105 GSCs/mouse, 15 mg/kg, I.P. injection), P = 0.0089, log-rank test. D H&E staining of the whole brains of mice bearing orthotopic xenografts of X01 GSCs treated with securinine, scale bar, 50 μm. E Schematic diagram of the high level of intracellular P4HB secreted into blood vessels. F, G Measurement of the serum protein level of P4HB in GBM patients and healthy controls from Henan Provincial People’s Hospital and Chinese PLA General Hospital in Beijing. ***P < 0.001, t-test. H Comprehensive overview of P4HB roles in GSCs tumorigenesis and its secretion into blood vessels as a diagnostic biomarker in GBM patients.

To fully utilize the property of P4HB as a secretory protein also found in exosomes [18], which may be valuable for developing it as a GSCs biomarker (Fig. 5E), we engaged two independent patient groups for blood analysis. The first group consisted solely of WHO IV grade GBM patients, while the second group included a mixed population of glioma patients ranging from low to high grades. Data demonstrated that high-grade GBM patients exhibited significantly higher levels of P4HB detected via ELISA, with almost all tested GBM patients showing elevated serum P4HB levels. In the mixed population, a significant difference in serum P4HB levels was also observed (Fig. 5F, G). These findings suggest that P4HB could serve not only as a potential therapeutic target for GBM but also as a biomarker for auxiliary diagnosis and monitoring of disease progression (Fig. 5H).

Discussion

GSCs are increasingly recognized as key contributors to the initiation, maintenance, and recurrence of GBM. Their stem cell-like properties, such as self-renewal and differentiation potential, combined with their resilience against standard therapies like temozolomide and radiation, highlight the importance of developing therapeutic strategies that specifically target GSCs to improve patient outcomes [44, 45].

Previous studies have reported a correlation between P4HB and drug resistance in GBM and proposed the role of P4HB in therapeutic resistance [17, 46]. In this study, we identified P4HB as a specific diagnostic marker as well as a therapeutic target for GSCs and demonstrated the involving regulation axis, which expands the known characteristics of P4HB and is important for understanding the behavior of cancer stem cells.

In this study, our data revealed that P4HB is highly expressed in GSCs, and its silencing drives apoptosis in GSCs through the activation of classical apoptotic effectors, such as Caspase-3 and PARP, and reduces the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins like BCL2. In addition, P4HB is integral to the maintenance of GSCs stemness via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Our findings support the existence of a P4HB-LRP6-Wnt/β-catenin axis in GSCs, where P4HB modulates the β-catenin nucleus location through decreased LRP6, which is crucial for GSCs stemness and tumor progression. Furthermore, the pharmacological inhibition of P4HB using the small molecule inhibitor CCF642 and the repurposed clinically approved drug securinine demonstrated its effectiveness in inhibiting GSCs progression.

In the context of precision medicine, developing serum biomarkers such as P4HB for the clinical diagnosis of GBM requires rigorous validation. P4HB has been pinpointed as being highly expressed in TMZ-resistant GBM [17]. However, translating P4HB into a precise diagnostic marker necessitates extensive clinical validation to ensure its accuracy across diverse patient populations and clinical settings. It is vital to determine whether P4HB expression is influenced by individual patient conditions, which could lead to variability in diagnostic outcomes. The potential for false-positive or false-negative results must be carefully evaluated, and the sensitivity of P4HB detection in early-stage GBM must be enhanced. Moreover, exploring whether P4HB could serve as a predictive marker for GBM recurrence or as an indicator of residual GSCs post-surgery could be pivotal for patient management and long-term monitoring. Challenges in the clinical application of P4HB include standardizing detection assays to ensure reproducibility and correlating serum P4HB levels with clinical outcomes. High-throughput screening methods and advanced technologies such as digital PCR or next-generation sequencing could be employed to refine the sensitivity and specificity of P4HB-based diagnostics. Furthermore, understanding the role of P4HB in different stages of GSCs progression could illuminate its potential as both a therapeutic target and a biomarker, providing deeper insights into GBM pathophysiology and aiding in the development of more targeted therapeutic strategies.

In addition to its diagnostic potential, P4HB is involved in critical cellular processes such as the unfolded protein response and maintaining redox homeostasis, which is essential for cancer cell survival under metabolic stress [47]. These functions suggest that P4HB may be involved in metabolic reprogramming within GSCs, potentially offering new avenues for combined therapy approaches. Moreover, the secretion of P4HB through exosomes points to its role in modulating the tumor microenvironment, particularly in influencing immune responses, which could be pivotal in GBM invasion and metastasis. Investigating P4HB’s impact on the immune microenvironment, including its interactions with immune checkpoint inhibitors and other immunotherapies [48], could reveal synergistic effects that enhance the efficacy of GBM treatments.

Securinine, an alkaloid from Securinega suffruticosa, shows potential for repurposing in GBM treatment due to its ability to induce apoptosis and its clinical application to other neurological diseases [43]. Whether combining securinine with temozolomide may yield better outcomes and whether securinine might sensitize GBM cells to radiation is worth further investigation. To boost the translation of securinine to GBM, addressing challenges such as tumor heterogeneity, resistance mechanisms, and dose design for minimal side effects will be crucial for successful clinical translation.

In conclusion, elucidating the P4HB-LRP6-Wnt/β-catenin axis offers new insights into the molecular mechanisms driving GSCs maintenance and GBM progression. This research underscores the dual potential of P4HB as a therapeutic target and a diagnostic biomarker for GBM, providing precision medicine insights for the translation of GBM tailored to the genetic and molecular landscape into clinical practice.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Patient-derived GBM stem cells (448, 83, X01) [27] and (528, 022) [49] were cultured in DMEM/F-12 medium, enhanced with B27 supplement (Invitrogen), and further augmented with EGF (10 ng/ml, R&D Systems) and bFGF (5 ng/ml, R&D Systems). Meanwhile, 293T cells were maintained in DMEM medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich). CCF642, securinine, and V-ZAD-FMK were purchased from TOPSCIENCE. V-ZAD-FMK, Z-DEVE-FMK dimethyl fumarate, ferrostatin-1, and the recombinant P4HB protein were purchased from MedChemExpress. To ensure the integrity of the cultures, all cells were routinely screened for mycoplasma contamination. The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Bioinformatics analysis

Expression matrices for P4HB in glioma patient samples were sourced from the GlioVis data portal (http://gliovis.bioinfo.cnio.es/) [50], which aggregates processed datasets from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA), and Repository of Molecular Brain Neoplasia Data (REMBRANDT) and CPTAC (The Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium). Detailed methodologies for data processing are available on the GlioVis portal help page. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were constructed across each dataset to compare overall survival probabilities between groups characterized by high and low expression levels of P4HB. The statistical significance of differences in survival outcomes was evaluated using log-rank and Wilcoxon tests. The expression plots, gene correlation plots, and survival curves were visualized by GraphPad Prism (v8.0).

To further investigate the specific expression of P4HB in GBM cells and GBM stem cells in GBM, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data from human GBM samples were analyzed. This dataset was acquired from the GEO data portal and processed using R software (v4.1.3). The analysis workflow commenced with the loading of raw counts using the ‘Read10X()’ function in the SEURAT package (v4.3.0) [51], followed by the generation of a Seurat object. Data normalization was performed with ‘NormalizeData()’, and variable features were identified using ‘FindVariableFeatures()’. Subsequent data scaling was accomplished with ‘ScaleData()’. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was implemented via ‘RunPCA’, with visualization conducted using ‘RunUMAP’. Marker genes were identified with ‘FindMarkers()’, and cellular clusters were annotated. The expression of the P4HB gene was distinctly highlighted on the 2D UMAP plot to delineate its distribution among various cellular subpopulations.

Lentivirus construction and infection

The shRNA-expressing lentiviral constructs targeting P4HB were engineered by ligating annealed oligomers into the PLKO.1 puro vector (Addgene). The sequences of the P4HB shRNA oligos are listed in Supplementary Table 1. All constructs were confirmed via DNA sequencing (Tsingke Biotech). For lentivirus production, 293T cells (3 × 106) were seeded in 100-mm culture dishes and incubated for 24 h. Subsequently, the cells were co-transfected with 4.5 μg of target plasmids and 4.5 μg of helper plasmids (psPAX2, pMD2.G, Addgene) using 27 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The culture medium was replaced 6 h post-transfection. After 48 h, the medium containing the lentiviral particles was collected. The viral particles were then concentrated and purified using a PEG8000 concentrator (Sangon Biotech). For infection, GBM stem cells were exposed to lentivirus in the presence of 10 μg/ml polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich) to enhance viral entry.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from GSCs using the FastPure® Cell/Tissue Total RNA Isolation Kit (Vazyme). Subsequently, 1 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA utilizing the HiScript II One Step RT-PCR Kit (Vazyme). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was conducted on a LightCycler 480 II real-time PCR system (Roche) employing the HiScript II One Step qRT-PCR SYBR Green Kit (Vazyme). The expression levels of the target genes were quantified relative to the housekeeping gene GAPDH. Primer sequences are provided in the Supplementary information primer list.

Westernblot analysis

Protein samples were extracted from GSCs using RIPA buffer supplemented with complete protease inhibitors (Solarbio, R0010), followed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The protein samples were subjected to electrophoresis analysis, transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore), and blocked with 5% skim milk (Vazyme). For the inhibitor study, 1 μM of CCF642 was added to the cell culture medium the day after seeding. The cells were harvested at subsequent time points: 0, 2, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h. In the nuclear-cytoplasmic separation experiment, nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins were isolated using a nuclear-cytoplasmic separation kit (Beyotime), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Western blots were incubated with primary antibodies targeting P4HB (Proteintech, #D154013), α-Tubulin (Proteintech, #11224-1-AP), GAPDH (HUABIO, #EM1101), Vinculin (Proteintech, #26520-1-AP), Caspase-3 and Cleaved Caspase-3 (CC3, Cell Signaling Technology, #14220, #9664), PARP and Cleaved PARP (C-PARP, Cell Signaling Technology, #9542, #5625), BCL-2 (1:1000, Abcam, #ERP17509), β-catenin (Beyotime, #AC106), LRP6 (Cell Signaling Technology, #2560T), P-LRP6 (ZENBIO, R30284), Cyclin D1 (Proteintech, #60186-1-Ig), NESTIN (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #PA5-11887), SOX2 (R&D Systems, #AF2018-SP), CD44 (R&D Systems, #BBA10), and Lamin B1 (Proteintech, #12987-1-AP) overnight at 4 °C. The recombinant protein was purchased from MCE (HY-P71917). The immunoreactive bands were visualized using peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and detected with the Amersham ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare).

Limit-dilution assay

GSCs were incubated in 96-well plates containing DMEM/F-12 supplemented with B27, 10 ng/ml of EGF, and 5 ng/ml of bFGF at decreasing numbers (100, 50, 25, and 5 cells/well), and the tumorsphere-forming ability was determined by counting wells without tumorspheres after incubation for 1 week. For the inhibitor study, 0.1 μM of CCF642 was added to the cell culture medium the following day after seeding. The results were evaluated using the Extreme Limiting Dilution Analysis function (ELDA, http://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/software/elda/).

Cell proliferation assay

GSCs were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 1000 cells per well to assess their proliferation across various culture conditions. This study was conducted over a duration of either 24 h or 6 days, with assessments carried out on days 0, 2, 4, and 6. Cell proliferation was quantified using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay every two days. Absorbance OD values were obtained using a Multiskan molecular device (Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer’s protocols. Cell viability was determined by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm of the culture medium. The result was analyzed and visualized using GraphPad Prism (v8.0).

Cell apoptosis assay

To evaluate apoptosis in glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs) transfected with P4HB shRNA, the cells were plated at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well in 6-well plates. Two days post-transfection, GSCs were collected and dual-stained with Annexin-V and propidium iodide (PI) in the binding buffer. Apoptotic rates were quantified using flow cytometry (BD Biosciences). To assess apoptosis induced by the P4HB inhibitor CCF642, GSCs were seeded in 6-well plates and incubated overnight. Subsequently, various concentrations of CCF642 were administered, and the cells were incubated for an additional 24 h. Apoptosis was determined using the aforementioned staining and flow cytometry techniques. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software.

Mice model

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Laboratory Animal Center at Henan University, China (HUSOM2023-462). Mice were group-housed in ventilated cages under controlled temperature and humidity, with a 12-h light-dark cycle. Each animal was randomized by body weight before the experiments. For the orthotopic mouse model, 1 × 104 luciferin-labeling 83 shCtrl or shP4HB GSCs were first resuspended and then transplanted into the left striatum of 5-week-old female BALB/c nude mice via stereotactic injection. The injection coordinates were 2.2 mm to the left of the midline, 0.2 mm posterior to the bregma, and at a depth of 3.5 mm. In a similar procedure for the treatment assay, 1 × 105 X01 GSCs were transplanted into the mouse brain. After 10 days, the mice were treated with a control reagent (PBS) or 15 mg/kg of securinine via intraperitoneal (I.P.) injection, 5 days a week for 3 consecutive weeks. After the injection, the mice were anesthetized and their tumor luminescence intensity was monitored by the Lumina IVIS III system, the body weight of the mice was individually measured every 2 days. The mice were euthanized using CO2 by the animal center when a 20% reduction in body weight or severe neurological symptoms were observed, the brain of each mouse was harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h at 4 °C for subsequent analysis like Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining. To evaluate the safety and biocompatibility of securinine, a comprehensive study was conducted using healthy BALB/c female mice aged 6–8 weeks. Following 1-week securinine administration (15 mg/kg, 5 times, I.P.), routine hematological parameters were analyzed, including white blood cell (WBC), red blood cell (RBC), and platelet (PLT) counts, along with blood chemistry markers such as aspartate aminotransferas (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), albumin (ALB), urea (UREA), creatinine (CREA), and uric acid (UA). In addition, core pro-inflammatory cytokines (Il-1β, Il-6, and Tnf-α) were measured in the liver and kidney tissues to assess potential inflammatory responses. Histological analyses were performed to examine any necrosis or apoptosis in major organs. Survival data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (v8.0).

Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain

After fixation, the brains were processed through a series of alcohols, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut at 4 µm using a microtome and mounted on glass slides. For H&E staining, sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated through graded ethanol to water, and stained with hematoxylin to highlight nuclei. After rinsing and differentiating in acid alcohol, the sections were blued in alkaline water and counterstained with eosin to highlight cytoplasmic components. The slides were then dehydrated, cleared in xylene, and then coverslipped. Histological evaluation was performed under a light microscope to assess tissue architecture and cellular morphology.

RNA-seq analysis

Total RNA was extracted from X01 shCtrl and shP4HB GSCs using the TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA sequencing libraries were prepared from 1 µg of total RNA using the NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (NEB Biolabs), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, mRNA was purified and fragmented, followed by cDNA synthesis, end repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, and PCR enrichment. Library quality was assessed on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, and quantification was performed using the Qubit DNA HS Assay Kit (Invitrogen). Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform, using paired-end reads. Raw sequencing reads were first subjected to quality control using FastQC (Babraham Bioinformatics) to assess base quality and sequence contamination. After cleaning, reads were aligned to the human reference genome (GRCh38) using the STAR RNA-seq alignment tool (v2.7). Default parameters were used, with adjustments for known splice junctions to improve alignment accuracy. Differential expression analysis was conducted using the DESeq2 (v1.34.0) R package. Genes with an adjusted P-value < 0.05 and a log2 fold change greater than 1.5 were considered significantly differentially expressed.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Serum samples from glioma patients and non-patients were collected from Henan Provincial People’s Hospital and Chinese PLA General Hospital. Blood samples were centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 5 min at room temperature, and serum aliquots were subsequently stored at −80 °C. P4HB concentrations in both patient and non-patient serum samples were determined using a Human Protein Disulfide Isomerase (PDI) ELISA Kit (CUSABIO), following the manufacturer’s protocol. This study was approved by the Ethics Committees of Henan Provincial People’s Hospital (Approval No: 2020-107) and Chinese PLA General Hospital (Approval No: S2021-095-02), and all participants provided informed consent prior to sample collection.

Statistics and reproducibility

All data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method. Multiple datasets were compared using ANOVA, followed by the log-rank test for survival analysis. Two-group comparisons were made using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Responses