Pathogenesis of aquatic bird bornavirus 1 in turkeys of different age

Introduction

Aquatic bird bornavirus 1 (ABBV1) is a neurotropic virus classified in the genus Orthobornavirus and family Bornaviridae1,2. First identified in Canada geese (Branta canadensis) from Southwestern Ontario, Canada, it has now been described in a variety of wild waterfowl from North America and Europe3,4,5,6,7,8. ABBV1 has been occasionally identified in taxonomically distant species, such as gulls (order Charadriiformes)9, a bald eagle (Hallaeetus leucocephalus)6, and an emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae)10.

The pathogenic potential of ABBV1 remains unclear. Case series and reports have identified the virus in the central nervous tissue (CNS) of Canada geese and trumpeter swans (Cygnus buccinator) that presented with a history of neurological signs, proventricular dilatation/impaction, and variable inflammation of the nervous system3,4,11. While these studies implicated ABBV1 as a possible cause of neurological disease, a direct causal relationship could not be proven. The reported signs and lesions appear similar to what is seen in psittacine birds with proventricular dilatation disease (PDD), a syndrome caused by parrot bornaviruses (PaBVs), another group of extant viruses in the orthobornavirus genus12,13,14.

Given the broad host range and potentially pathogenic role of ABBV1, infection trials have been performed by our research group to assess the susceptibility of poultry species to become infected with ABBV1 and develop disease. Using a similar protocol in 1- to 2-day-old birds, we have shown that Muscovy ducks (Cairina moschata)15, Pekin ducks (Anas platyrhynchos domesticus)16, and chickens (Gallus gallus)17 could become infected by intracranial (IC) and intramuscular (IM) inoculation, albeit less efficiently in chickens, which were less susceptible to virus dissemination. While most infected birds developed lymphocytic perivascular cuffs in the CNS, neurological signs were uncommon15,16,17.

Currently, it remains unknown why neurological impairment would be so limited in the face of robust CNS inflammation, however, since orthobornaviral disease is primarily immune-mediated18,19,20,21, it is possible to hypothesize that the early age at infection could lead to immune tolerance to the virus, resulting in a less severe disease phenotype. Indeed, neonatal rats (under 48 h old) inoculated with a mammalian orthobornavirus (Borna disease virus 1; BoDV1) developed persistent CNS infection with no clinical disease or inflammation, while older (>28 days) rats died of encephalitis22. Similarly, young (1–6 days old) cockatiels inoculated with PaBV4 became persistently infected and developed CNS inflammation without clinical signs, while older cockatiels (1–5 years of age) progressed to PDD23.

The first objective of this study was to assess the susceptibility of turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo domesticus), an economically relevant species, to ABBV1 infection. As chickens are susceptible to infection17, it is reasonable to expect that turkeys, another gallinaceous bird, may also become infected and exhibit clinical disease. The second study objective was to evaluate the effect of age at the time of ABBV1 infection. We hypothesized that older turkeys would be more prone to develop overt clinical disease compared to birds infected at 1 day of age, as shown for other orthobornaviruses.

Results

Population demographics

A total of 196 turkeys were assigned to two age groups: young and old, which were inoculated at 1 day and 6 weeks of age, respectively. Each age cohort was inoculated intramuscularly with either the virus (virus-inoculated, VI) or carrier only (control, CO) in the left gastrocnemius muscle. Birds in the VI groups received 6.9 × 105 focus forming units (FFUs) of ABBV-1. In the young VI cohort, one bird died immediately after inoculation. In the young CO group, four died spontaneously and were too autolyzed for sampling and an additional 2 were in excess at the termination of the trial at 12 weeks post-infection (wpi) (none of these six birds was included in the study). Therefore, the final experimental cohort consisted of 189 birds, with 56 and 50 in the young VI and CO groups; and 40 and 43 in the old VI and CO groups (Supplementary Fig. 1). Post-mortem examination confirmed that all turkeys were male.

Clinical disease and gross lesions

General

A summary of the clinical signs and gross lesions identified throughout the study is reported in Table 1, with individual-animal data in Supplementary Table 1. Birds with severe clinical signs were humanely euthanized outside of sampling schedule, or intentionally selected at the scheduled time points (see Materials and Methods). Neurological signs were observed in six birds, while a considerable number of birds (78; 41%) developed clinical signs and/or presented with gross lesions not consistent with ABBV1 infection, and which were attributed to background diseases typically seen in commercial turkeys. Of these, cardiovascular (mainly dilated cardiomyopathy, DCM) and musculoskeletal (mainly angular limb deformities, ALD) diseases were the most common cause of mortality and/or culling. Overall, spontaneous death or culling outside of the sampling schedule in the young cohort accounted for a cumulative mortality of 25%, with a mortality rate of 4% per bird week (Supplementary Table 2). In the old cohort, since birds were inoculated, the total cumulative mortality was 12%, and the mortality rate was 1.9% per bird week (Supplementary Table 3). Across the entire study population, there was no significant difference (Fisher’s exact test) between the proportion of DCM or ALD frequency in birds that were infected (i.e., having ABBV1 RNA in brain and/or spinal cord) and those that were not. Additional details about non-neurological disease are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Neurological disease

Neurological signs were observed in 6 turkeys from the young VI treatment group (6/56, 11%) over the course of the trial (Tables 1 and 2). These included a combination of inability to stand, ataxia, and loss of balance, which prompted immediate euthanasia. Of these birds, 4 (T442-T445) were euthanized outside of the scheduled sampling time (defined as emergency birds), between 63 and 65 days post-inoculation (dpi), while the other 2 (T452, T454) displayed similar neurologic signs at the endpoint of the study (week 12 sampling). Since all these birds were euthanized after 8 wpi, their findings were tallied in the 12 wpi time point for analytical purposes.

Postmortem examination revealed no gross lesions in the nervous or musculoskeletal systems of these 6 birds. All (6/6) birds exhibited lymphocytic myelitis, and 4/6 also exhibited encephalitis in the brainstem and/or optic lobe (Table 2). All birds tested positive for ABBV1 RNA in the brain and spinal cord, and one bird (T452) was also positive in the gonad. Immunoreactivity against ABBV1 nucleoprotein (N) was assessed for all six birds in the brain and available segments of spinal cord. Three birds (two of which were sampled at 12 wpi) were immunoreactive in the brain (T445, T452, and T454); of these two also showed reactivity in the spinal cord (T445 and T454). A non-parametric Mann-Whitney test comparing the magnitude of virus RNA copies did not show significant differences in the brain or spinal cords of neurological birds with or without IHC reactivity. Serum was available for all six neurological turkeys (both emergency birds and those euthanized at 12 wpi), and of these, 3 (50%, T442, T452, T454) showed optical density (OD) values above the threshold (Table 2).

Microscopic pathology and immunohistochemistry for cellular markers

Lesions of the nervous system

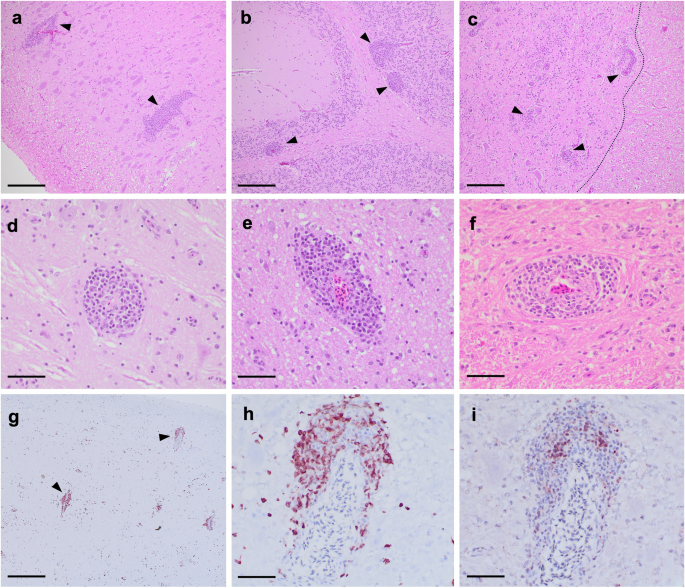

Lymphocytic inflammation of the brain (encephalitis) and spinal cord (myelitis), in the form of perivascular cuffs, was considered supportive of ABBV1 infection. Such lesions were present exclusively in young VI turkeys, with encephalitis identified in 88% (14/16) of birds at 12 wpi, and myelitis in 25% (1/4) and 100% (16/16) of birds at 8 and 12 wpi, respectively (Table 3). All these turkeys tested positive for ABBV1 RNA in the brain and/or spinal cord. No inflammation of the central nervous system (CNS) was identified at other time points in the young VI cohort, or in any bird from the young CO group. By 12 wpi, perivascular cuffs in the brain were randomly distributed and affected the brainstem (88%; 14/16) (Fig. 1a), optic lobe (75%; 12/16), cerebrum (56%; 9/16), and cerebellum (50%; 8/16) (Fig. 1b). Within the spinal cord (Fig. 1c), inflammation was predominantly associated with the junction of gray and white matter. Throughout the CNS, perivascular cuffs were composed of small lymphocytes arranged into 1–13 layers around meningeal, cerebral, and spinal cord blood vessels (Fig. 1d–f). Immunohistochemistry for CD3 and PAX5 highlighted the perivascular cuffs within the parenchyma and revealed that the inflammation was predominantly (>90%) composed of cells with finely granular and cytoplasmic to membranous reactivity for CD3+ (T cells; Fig. 1g, h), while only a minority of cells showed intranuclear reactivity for PAX5+ (B cells; Fig. 1i).

At low magnification (100×; a–c, bar = 400 µm), inflammatory cuffs are observed scattered throughout different regions of the CNS (arrows), as observed in a the brainstem of turkey T453 at 12 wpi (HE); b the cerebellum of turkey T454 at 12 weeks post-inoculation (wpi), where cuffs appear to localize mostly at the junction between the white matter and the granule cell layer (HE); and c the lumbar spinal cord of emergency turkey T445, euthanized at 9 wpi, where perivascular cuffs are observed mainly at the junction of the white and gray matter (dashed line, HE). At higher magnification (400×; d–f, Bar = 40 µm), cuffs appear composed of small cells with condensed chromatin and high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, consistent with lymphocytes. These cells are mainly confined to the leptomeninges, with minimal encroachment into the adjacent parenchyma, as observed in d the brainstem of turkey T450 (HE), e the optic lobe of turkey T450 (HE), and f the lumbar spinal cord of emergency turkey T444, which underwent emergency euthanasia at 9 wpi (HE). Immunohistochemistry for CD3 and Pax5 markers was carried out to assess the composition of the perivascular cuffs. g Brainstem of turkey T454. Strong immunolabelling for CD3 (red/brown) is observed in numerous perivascular cuffs (arrows) throughout the neuroparenchyma. NovaRED chromogen with hematoxylin counterstain, magnification 40× (Bar = 1 mm). h Brainstem of young VI turkey T454, higher magnification of previous panel. Immunoreactivity for CD3 (red/brown) is cytoplasmic to membranous and labels the majority of cells in the cuff, with only rare positive cells scattered in the adjacent neuroparenchyma. NovaRED chromogen with hematoxylin counterstain, magnification 400× (Bar = 40 µm). i Brainstem of young VI turkey T454, same field of previous panel. Rare perivascular mononuclear cells show intranuclear reactivity for Pax5. NovaRED chromogen with hematoxylin counterstain, magnification 400× (Bar = 40 µm).

In the old cohort, rare lymphocyte clusters (<5 cells) were identified in the optic lobe of an old VI turkey (T333) at 12 wpi, albeit only on the CD3-labeled slide, and not by hematoxylin-eosin stain (HE). One old VI turkey (T319) presented with mild, focal perineuritis of the brachial plexus at 4 wpi with no evidence of nerve damage (Table 3). These old birds were both negative for ABBV1 RNA in the brain or spinal cord.

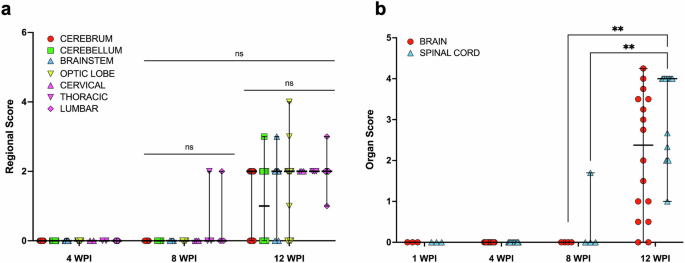

Considering the young VI group only, there was no significant difference in the proportion of inflammation between different CNS regions (including different segments of the spinal cord) at 12 wpi (Chi-square test = 0.78). Similarly, the average magnitude of inflammatory lesions in the different segments of the CNS (i.e., regional scores, RS) did not significantly differ at 8 or 12 wpi (p > 0.9999), or between 8 and 12 wpi (>0.1784) (Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons), despite an increase in the number of birds with inflammatory lesions between these time points (Fig. 2a). The average inflammatory score for the entire brain and spinal cord (i.e., organ scores, OS) showed that only the spinal cord was significantly higher at 12 wpi compared to both the brain (p = 0.0018) and spinal cord (0.0087) at 8 wpi (Fig. 2b).

Regional scores (RS, a) and organ scores (OS, b) for the brain and spinal cord sampled from young turkeys inoculated intramuscularly with aquatic bird bornavirus 1 (ABBV1) at 1 day of age, and sampled at 1, 4, 8, and 12 weeks post-inoculation (wpi). Tissues from the young control and the old groups are not plotted due to lack of inflammation, and the 1 wpi time point in graph a is not plotted due to lack of lesions. Represented are individual-animal data points with median (horizontal bar) and range (vertical bar). Differences between groups at the same time point, or within the same tissue across time points (only 8 and 12 wpi) were assessed by Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s correction for multiple comparisons. Differences between datasets are identified by binary connectors (p < 0.05 *; 0.01**; ns = nonsignificant).

Lesions not affecting the nervous system

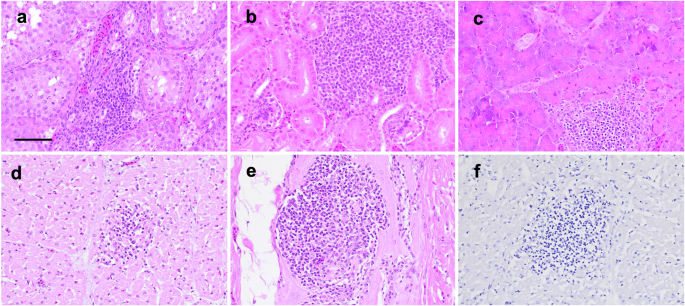

Small (<500 μm diameter) lymphocytic aggregates, which were not associated with tissue damage, were observed in the interstitium of the uropygial gland (26/31; 84%), skin (35/48; 73%; mainly adjacent to rare feather follicles and in the superficial dermis), testis (72/103; 70%; Fig. 3a), adrenal glands (31/52; 60%), thyroid gland (16/47; 34%), parathyroid gland (5/17; 29%), kidneys (29/109; 27%; Fig. 3b), pancreas (11/47; 23%; Fig. 3c), and liver (9/50; 18%). Small aggregates of lymphocytes were also detected in the myocardium of 4/49 birds (8%): 2 young VI turkeys at 4 (T429) and 12 wpi (T451), and in the myocardium and/or epicardium of 2 old CO birds sampled at 12 wpi (T136, and T141) (Fig. 3 d, e). While the VI birds were positive for ABBV1 RNA in the CNS, ABBV1 N protein was not detected by IHC in the 3 tested hearts (Fig. 3f; T429 had no more tissue available). Six turkeys (15%) from both the VI (n = 4) and CO (n = 2) groups had lymphocytic myositis of the gastrocnemius muscle, interpreted as damage from the site of inoculation. Fisher’s exact tests did not show significant differences in the proportion of inflammatory lesions between infected and non-infected birds (as defined by having ABBV1 RNA detected in brain or spinal cord) for kidneys (p > 0.99), liver (0.39), pancreas (>0.99), thyroid (0.07), parathyroid (0.53), adrenal (0.72) and uropygial (>0.99) glands, and skin (0.46). However, the proportion of interstitial inflammation in the gonads was significantly higher in birds that became infected, compared to those that did not (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.03). No association between presence of these inflammatory lesions and infectious status was observed by unconditional association analyses (see below).

a Focal lymphocytic inflammation in the testis of an old CO turkey (T133) sampled at 8 wpi; hematoxylin and eosin (HE). b Focal lymphocytic inflammation in the interstitium of the renal cortex of a young CO turkey (T203) sampled at 1 wpi (HE). c Focal lymphocytic inflammation in the pancreas of an old CO turkey (T133) sampled at 8 wpi (HE). d Focal lymphocytic myocarditis in the ventricle of a young VI turkey T451 sampled at 12 weeks post-inoculation (wpi) (HE). e Focus of lymphocytic epicarditis in the ventricle of old CO turkey T136 sampled at 12 wpi. Inflammatory cells also surround a segment of conduction fiber (HE). f Focal lymphocytic myocarditis in the ventricle of a young VI turkey T451 sampled at 12 wpi. There is no reactivity to ABBV1 nucleoprotein (N) in the myocytes adjacent to the inflammation; immunohistochemistry for ABBV1 N; NovaRED chromogen with hematoxylin counterstain. For all pictures, 200× magnification (Bar = 100 µm).

Microscopic lesions that were considered incidental were observed throughout the study. These included variable inflammation of Meckel’s diverticulum (luminal to mural accumulation of heterophils and development of heterophilic granulomas with mucosal ulceration) in ten birds from both experimental and age groups; presence of heterophils and cellular debris occasionally present within the cecal tonsils of 4 birds; mild cartilaginous metaplasia of the aorta at 4 wpi in one old CO bird; and an ectatic left ureter in an old VI bird.

ABBV-1 distribution in tissues

Distribution of ABBV-1 RNA

The concentration of ABBV1 RNA was measured by RT-qPCR in the brain, spinal cord, kidney, proventriculus, gonads, and choanal and cloacal swabs, in all birds that underwent in-time sampling (n = 155), and the VI turkeys that were euthanized outside of the sampling schedule (i.e., emergency birds) after 8 wpi (n = 5). For all the VI and CO emergency turkeys included in the 4 and 8 wpi time points, only brains were processed (n = 27; Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). A summary of RT-qPCR results is reported in Table 4.

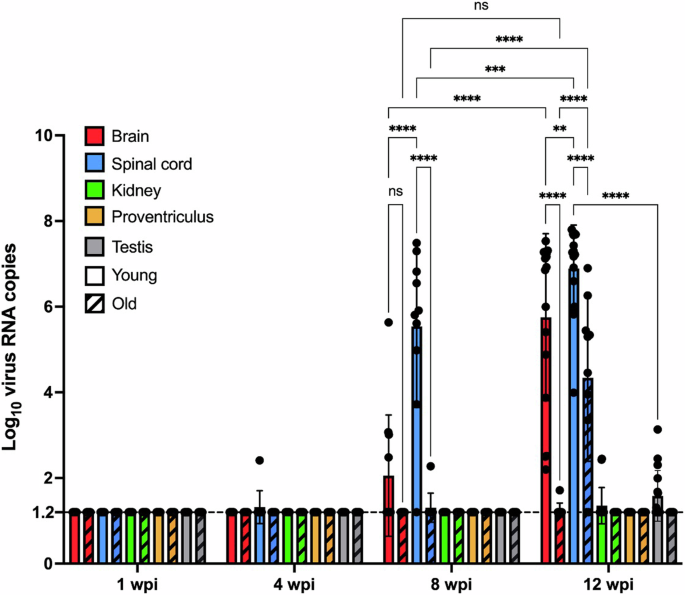

In the young VI group, viral RNA was first detected at 4 wpi in the lumbar spinal cord of a single poult out of the 10 tested (10%). The number of positive spinal cord samples increased over time, with 9/10 (90%) and 16/16 (100%) testing positive at 8 wpi and 12 wpi, respectively. In the same group, viral RNA was first detected in brains at 8 wpi, with 4/11 (36%) poults testing positive, a proportion that increased by 12 wpi to include all tested poults (16/16; 100%). Viral RNA was detected outside of the CNS only at 12 wpi, with 44% (7/16) and 13% (2/16) of the testicular and renal samples testing positive, respectively.

In the old VI group, virus RNA was not detected until 8 wpi, when a single bird (1/10; 10%) tested positive in the spinal cord. By 12 wpi, there were 8/10 (80%) positive spinal cord samples, and 1/10 (10%) positive brain samples. Viral RNA was not detected in the gonad, kidney or proventriculus of these birds at any time point (Table 4). No viral RNA was amplified in tissues from control birds or in proventriculus or swab samples at any time point, regardless of age cohort or experimental group.

The average ABBV-1 RNA concentration between tissues was compared at the same time point across age cohorts, or within the same age cohort across time points (8 and 12 wpi only) (Fig. 4). The viral RNA concentration in the spinal cord was significantly higher in young VI turkeys compared to old ones at both 8 and 12 wpi (p < 0.0001). In the brain, this difference was significant only at 12 wpi (p < 0.0001). The spinal cord in the young cohort had a higher virus concentration compared to the brain at both 8 wpi (p < 0.0001) and at 12 wpi (0.0011), as well as compared to the other tissues from the same age cohort, including testis (<0.0001). At 12 wpi, the spinal cord in the old cohort had higher RNA amounts compared to the brain (p < 0.0001) and all the other tissues from the same age cohort (not shown). When comparing across time points, in the young VI group the concentration of virus RNA significantly increased in the brain (p < 0.0001) and spinal cord (0.0004) between 8 and 12 wpi. In the old cohort, a significant increase was seen in the spinal cord only (p < 0.0001).

Samples were collected at 1, 4, 8, and 12 weeks post-inoculation (wpi). Samples from the control birds and swabs are not included in the graph as they were negative at all time points. The old cohort is identified by a bar filling pattern. For each tissue, represented are scatter plot of individual data with group average (columns) and standard deviation (SD; error bars). Differences between group means were tested by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons; differences between groups are identified by binary connectors (p < 0.05*, 0.01**, 0.001***, 0.0001****; ns = non-significant). Negative samples are plotted at the limit of detection of the RT-qPCR assay (log10 of 16 virus RNA copies/150 ug of total tissue RNA; dashed line).

Distribution of ABBV1 in tissues by immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry for ABBV1 N protein was performed on 4 young and 3 old VI birds that underwent full tissue sampling at 12 wpi, as well as 5 young VI birds that were euthanized between 8 and 12 wpi and underwent partial tissue sampling (i.e., T442–446; Table 5)

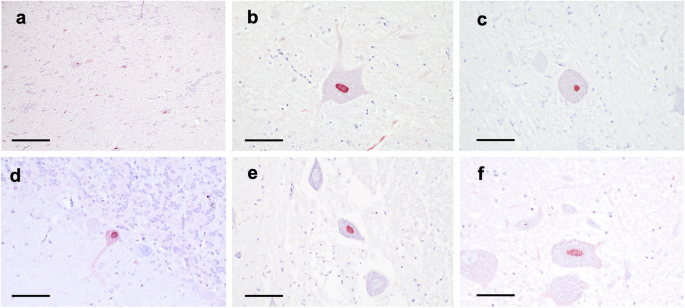

Of the nine young VI birds examined by IHC, which were all positive for ABBV1 RNA in the brain and/or spinal cord, 4 displayed immunoreactivity in both brain and spinal cord, one in the brain only, and 4 in neither location. Immunoreactivity was characterized by strong nuclear or nuclear and cytoplasmic immunoreactivity in the neurons of the brainstem, where the highest density of affected neurons was observed (Fig. 5a–c), and in the cerebrum, cerebellum (Fig. 5d), optic lobe, and spinal cord (Fig. 5e). Other than neurons, no other cells in the CNS were immunoreactive. Inflammation in the brain and /or spinal cord was observed in all 9 of these birds, although ABBV1 N immunoreactivity did not co-localize with lesions (Table 5). Birds that underwent full sampling showed no immunoreactivity in visceral organs, despite renal and testicular tissues being positive for ABBV1 RNA in one turkey (T451; data not shown).

Nuclear reactivity to ABBV1 antigen is observed (a) in the nuclei of scattered large neurons (arrows) in the brainstem of young turkey T454 at 12 weeks post-inoculation (40×, Bar = 500 µm); b in the brainstem of young VI turkey T450, where rare neuronal processes also appear reactive; c the brainstem of young VI turkey T445 (emergency bird); d the cerebellum of young VI turkey T454, where immunolabelling with ABBV1 antigen is observed in the neurons of scattered Purkinje cells; e in the ventral horns of the thoracic spinal cord of young VI turkey T450; and f in the brainstem of old VI turkey T339 (for b–f, magnification 400×, Bar = 40 µm). For all figures, NovaRED chromogen with hematoxylin counterstain was employed.

In the old VI group, 1/3 turkeys (T339) exhibited ABBV1 N immunoreactivity in the brainstem exclusively (Fig. 5f). This bird was positive for ABBV1 RNA in the brain and spinal cord, and no inflammation was present on HE in either tissue. None of the control birds tested had immunolabelling for ABBV1 N protein (Table 5).

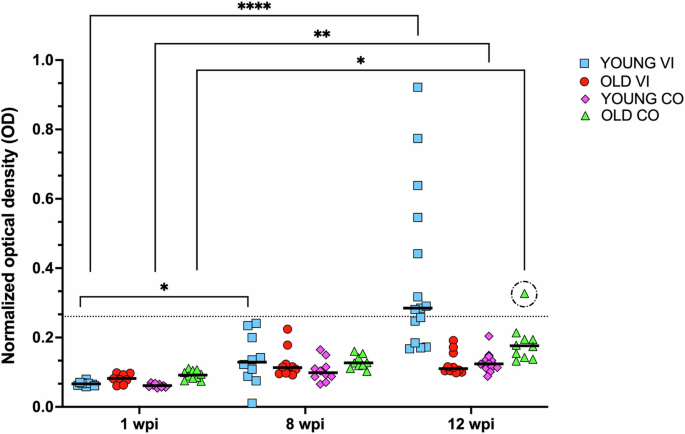

Serology

The concentration of serum IgY directed against the ABBV1 N was assessed by indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in the serum of turkeys from 1, 8, and 12 wpi (Fig. 6). Only the young VI group demonstrated evidence of seroconversion, as shown by 9/15 (60%) turkeys in the 12 wpi group that had optical density (OD) values greater than the calculated threshold (normalized OD = 0.261). Of these 15 birds, 5 were emergency turkeys sampled between 8 and 12 wpi, of which turkey T442 was the only one to seroconvert (this bird showed inflammation and had neurological sign). Of the remaining eight birds that seroconverted, all were collected at 84 dpi (12 wpi sampling), and all presented with myelitis and/or encephalitis, and had ABBV1 RNA in the brain and/or spinal cord, with five also positive in the gonad and one in the kidney. In the old cohort, no bird seroconverted, except for one old CO turkey (T143) with normalized OD value slightly above the threshold. This bird was negative for ABBV1 RNA in tissues, and was considered to be an outlier (above the 75th percentile of the interquartile range).

Reactivity was evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and reported as normalized optical density (OD). Young (Y) and old (O) cohorts of turkeys were inoculated intramuscularly at 1 day or 6 weeks of age, respectively, with either ABBV1 (virus-inoculated; VI) or carrier only (control; CO). Sera were collected at 1, 8, and 12 weeks post-inoculation (wpi). Threshold for seroconversion (OD = 0.26) was determined as the average optical density of all young and old CO birds, plus 3 times the standard deviation. Represented are scatterplots with data median (straight line). Differences between groups were tested by Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons, and are represented by connectors (p < 0.05*, 0.01**, 0.001***, 0.0001****). One old CO turkey had an OD value above the threshold (dotted circle); this datapoint was considered to be an outlier (Grubb’s test, see text). Inclusion or exclusion of this datapoint did not change the statistical analysis.

Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons was used to compare the normalized OD value group averages between all experimental groups and time points. There were no differences between any of the groups at the same time point (1 wpi, p > 0.99; 8 wpi, >0.99; 12 wpi, >0.16). Significant OD increases were identified in the young VI group between 1 wpi and 8 (p = 0.047) and 12 (<0.0001) wpi. Between 1 and 12 wpi, there was an increase in normalized OD values in both the old CO and young CO groups (p = 0.0234 and 0.0018, respectively), although the median of each group was maintained below the threshold calculated for all sampling points (Fig. 6).

Statistical analysis

Unconditional univariable association was first carried out to identify correlations between the bird infectious status (Model 1) or inflammation in the spinal cord (Model 2), and several explanatory variables (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). In Model 1, infectious status (defined as the presence of ABBV1 RNA in the brain and/or spinal cord) was associated exclusively with one variable (pathology score of the spinal cord) and therefore a multivariable model was not built. In this association for a unit increase of spinal cord pathology score, there was a 14.44 chance increase that the bird may have presented ABBV1 infection (p = 0.004). For Model 2, unconditional univariable association showed a significant positive association between inflammation in the spinal cord and the following predictor variables: age cohort (p = 0.002), virus RNA amount in the brain (0.001), virus RNA amount in the spinal cord (0.001), magnitude of seroconversion (OD value × 100; 0.001), and presence of any clinical signs (0.009). A multivariable regression model was therefore built using these five predictors. Results showed that virus RNA load in the spinal cord was significantly associated (p = 0.008) with spinal cord inflammation: for each tenfold increase (1 log10) in RNA copies in the spinal cord, the odds of having inflammation in the spinal cord were ~2 times higher. Additionally, for every 0.01 increase in the original OD value (or 1 unit increase in the scaled OD value), the odds of spinal cord inflammation increased by 20% (Table 6).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to expand upon the current understanding of ABBV1 pathogenesis by characterizing the susceptibility of domestic turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo domesticus) to infection with ABBV1 at one day (young) and 6 weeks (old) of age. Two ages were selected to test the hypothesis that older birds might develop more severe clinical signs and lesions, as observed in cockatiels infected with PaBV423.

Results showed that turkeys are susceptible to ABBV1 infection when inoculated through an intramuscular route, leading to infection rates of 100% and 80% in the young and old cohorts, respectively, by the end of the study (12 wpi). The high infection frequency in the young cohort (i.e., 100% in the group terminated at 12 wpi, and 56% overall from the beginning of the study) are roughly comparable to what was observed in day-old waterfowl species infected intramuscularly with a similar method by our group. Specifically, Pekin ducks (Anas platyrhynchos domesticus) had 100% infection rate at 12 wpi and 56% overall, and Muscovy ducks (Cairina moschata) 100% and 72%, respectively15,16. Interestingly, lower infection rates than turkeys were seen in Canada geese (77% infection rates by the end of the study and 39% overall24) and chickens (33% and 20%17). The higher susceptibility of turkeys to ABBV1 infection compared to chickens, another gallinaceous bird, may have been partly caused by the higher virus dose received by turkeys (6.9 ×105 FFUs/bird compared to 1.3 × 105 FFUs/bird17). Nonetheless, in our experience, this difference is unlikely to have significantly impacted infection take, especially over a multiple-week study. For instance, Pekin ducks receiving only 2.9 × 104 FFUs/bird yielded high infection rates16, while cockatiels and conures have been successfully infected with doses of PaBVs as low as 4–8 × 104 FFUs/bird25,26. Therefore, based on the experience from our previous studies15,16,17,24, a dose in the upper range of 105 FFU/bird was employed regardless of age, as successful infection was considered the most important goal for this study. There is no clear indication in the literature of how, and if, virus inoculum should have been adjusted to body weight (as a proxy for age), as infectious dose would not be dependent on bird size during natural infection. Furthermore, it was preferred to vary only one parameter (i.e., age), while keeping the inoculum dose constant.

While the old cohort presented an overall infection rate lower than the young cohort, by the end of the study there were no differences in the proportion of infected spinal cords between the two groups. Furthermore, the old VI birds showed a trend towards increasing virus RNA burden compared to the previous time point, suggesting that permissivity to ABBV1 infection did not differ between age groups, and that a longer time could have afforded higher rates of CNS infection also in older birds. This explanation is consistent with intra-axonal virus spread27, which could simply require longer time for the virus to move from the periphery to the CNS in birds of different sizes. Lack of inflammation in the older cohort further supports this explanation, as a delayed axonal spread could not be ascribed to tissue reaction. The faster virus spread observed in young birds might be also explained by the higher virus dose relative to their body mass, as the inoculum was not adjusted for weight. In this scenario, the relatively larger inoculum could have infected more nerve endings, potentially accelerating the progression of infection.

While centripetal spread was clearly present in both young and old turkeys, centrifugal dissemination (i.e., from the CNS to visceral organs) was detected exclusively in young VI turkeys at 12 wpi, with virus RNA detected in 44% of the gonads and 2% of the kidneys. Pekin and Muscovy ducks (inoculated intramuscularly at day of age) showed 56% and 100% rates of centrifugal spread by 12 wpi, respectively, while chickens inoculated in the same way showed none (consistent with the comparatively lower degree of CNS infection)15,16,17. Lack of ABBV1 visceral spread in the old cohort is likely caused by a delayed stage of infection, as evidenced by almost complete absence of ABBV1 RNA in the brain and spinal cord of old birds at 8 wpi, and a significantly lower magnitude of RNA concentration in these organs at 12 wpi, compared to young birds. The absence of perivascular cuffs in the CNS of birds in the old cohort further suggests that this limited virus spread was not caused by inflammation.

In partial agreement with the broader ABBV1 RNA distribution observed in young compared to old turkeys, and the overall higher virus RNA concentration in the CNS compared to the visceral organs, IHC signal for ABBV1 N protein at 12 wpi was detected exclusively in the CNS, and more frequently in the young cohort. As described in previous experiments15,16,17,24, immunoreactivity for ABBV1 N did not appear localized to specific areas, and was exclusively confined to neurons, albeit in Muscovy and Pekin ducks reactivity could also be observed in rare ependymal and glial cells.

While all birds showing IHC reactivity for ABBV1 N protein in the CNS were also positive for virus RNA, in 3 turkeys there was no immunoreactivity despite relatively high virus RNA loads in the brain and spinal cord. Similarly, while ABBV1 RNA was detected in the kidney and gonad of one of the birds tested for IHC, no immunoreactivity was observed in these organs. The presence of viral RNA without positive immunolabelling could be caused by a series of factors, including the lower sensitivity of IHC compared to RT-qPCR, the integrity and orientation of the tissues (which could miss a multifocal pattern of reactivity), and—for viscera—the relatively low magnitude of virus RNA burden compared to the CNS. Lack of visceral immunolabelling for ABBV1 is consistent with what was observed in similar experimental studies with chickens17, but contrasted with what was documented in Pekin ducks, Canada geese and Muscovy ducks (the latter inoculated intracranially instead of intramuscularly), all of which presented some combination of visceral labeling in the myenteric plexuses of the stomachs and intestine, ganglia adjacent to the adrenal glands, as well as in the testes and ovaries15,16,24.

In agreement with the relatively modest visceral dissemination observed by RT-qPCR and IHC, the choanal and cloacal swabs tested negative for ABBV1 RNA during the entire course of the study. These findings are consistent with absent to relatively low shedding instances observed in swabs from other tested species that were inoculated intramuscularly with ABBV1, including chickens (0% choanal; 0% cloacal), Canada geese (11%, 0%), and Muscovy ducks (0%, 13%); although choanal shedding was identified in a larger proportion of Pekin ducks (21%, 0%)15,16,17,24. It is unclear if a longer study could have allowed viral shedding due to a more widespread visceral infection.

One hypothesis driving this study was that ABBV1 might behave like other orthobornaviruses (e.g., PaBV4 in cockatiels and BoDV1 in rats), which typically cause asymptomatic, persistent CNS infections in hatchlings or neonates, but lead to clinical disease and severe inflammation in older animals21,22,23. This age-related difference is thought to result from very young animals developing immune tolerance and a weaker cell-mediated response to the persistent virus18. Therefore, it was hypothesized that older turkeys would show more severe clinical signs and lesions. In contrast to this hypothesis, clinical manifestations attributable to infection with ABBV1 were observed exclusively in the young cohort, where ~11% of young VI turkeys (all of which were infected) developed ataxia, recumbency and paresis between 9 and 12 wpi. The rate of neurological signs in the present study exceeds what has been documented in most ABBV1 infection trials conducted in our laboratory: intramuscularly inoculated Muscovy ducks, Canada geese, and chickens did not develop clinical signs by the end of the study at 12, 18, and 12 wpi, respectively15,17,24. Only Pekin ducks appeared more susceptible, with 6 of 30 (20%) birds inoculated by the intramuscular route developing ataxia (loss of balance) in a similar timeframe (≈7.5–11 wpi)16.

It is unclear why neurological signs were not observed in the old turkey cohort. While it is possible that the age hypothesis may not hold true for this species, it is important to consider that the young cohort was at a more advanced stage of infection by the end of the study. As discussed previously, in the old cohort, ABBV1 RNA was detected in fewer birds and at lower magnitude in the spinal cord, and especially brain, when compared to young birds. This difference may explain the reason why no inflammation was observed in old turkeys, ultimately leading to lack of neurological disease. Extending the duration of the study might have allowed for more extensive infection of the brain and spinal cord in the old cohort, potentially triggering an inflammatory response and the development of neurological signs. While this would have allowed a more accurate comparison between the two age groups, logistical constraints did not allow keeping turkeys beyond 18 weeks of age. Additionally, since all meloxicam-treated birds (n = 6) were exclusively in the control (non-inoculated) groups (three young and three old turkeys), the treatment for lameness could not have influenced disease progression in the infected birds.

Lymphocytic cuffs in the spinal cord and/or brain were observed exclusively in young turkeys, without predilection for a specific region, as evidence by lack of differences between regional pathology scores, or proportion of affected areas. All turkeys with myelitis and/or encephalitis had evidence of ABBV1 in the CNS, and inflammation seemed to parallel the magnitude of virus replication, with mild myelitis detected first at 8 wpi, and increasing in intensity by 12 wpi (albeit this difference was not significant). These findings are consistent with the multivariable regression analysis, which showed a positive correlation between presence of inflammation and the concentration of virus RNA in the spinal cord.

While all six birds with neurological signs in the current study presented with encephalitis and/or myelitis, another 11 young and one old turkey presented with CNS inflammation without evidence of neurological signs. This is consistent with previous studies, which showed that most birds did not present neurological signs despite morphological evidence of inflammation15,16,17,24. Similarly, while young cockatiels infected with PaBV4 presented with lymphocytic cuffs in the CNS, they did not develop clinical signs23. These data suggest that the observed lymphocytic infiltrate may not be functional. A transcriptomic study, done on the brain of chickens and Muscovy ducks infected with ABBV1 at 12 wpi, showed upregulation of immune-modulatory cytokines, such as PD-1, CTLA-4, and LAG3, suggesting a dampening of the immune response in ABBV1-infected tissues, despite morphological evidence of inflammation28.

While lesions in the CNS were consistent with what was reported in the context of ABBV1 infection in both experimentally15,16,17,24 and naturally infected birds3,11, inflammation of the peripheral nervous system, such as ganglionitis, was not observed3,4,11. Perineuritis of the brachial plexus was observed in a single old VI turkey. Since this bird was negative for ABBV1 viral RNA in all tissue tested (including brain and spinal cord), it is likely that this small focus of inflammation may represent an incidental finding, although an abortive infection cannot be fully excluded.

Only 60% of young VI turkeys seroconverted; these birds had presence of inflammation and virus RNA in the CNS, although not all birds with these findings (i.e., presence of virus RNA and inflammation) seroconverted. Like what was observed in previous studies15,16,17,24, turkey sera appeared to have increased non-specific reactivity as birds aged. The reason for this is unclear, but it may be related to increased IgY serum concentrations as birds become exposed to various environmental antigens with age, as seen with IgG concentrations in humans29.

Lack of seroconversion in old turkeys is consistent with no CNS inflammation, and it is likely a reflection of the less advanced stage of virus dissemination (as previously discussed). However, considering that 8/10 old VI birds had ABBV1 RNA in the spinal cord by 12 wpi, lack of myelitis and seroconversion argues against the notion that older birds may be more predisposed to develop immunopathology. On the other hand, seroconversion and inflammation in young VI turkeys suggest that inoculation of hatchlings did not induce complete tolerance. It is possible, however, that an offset of only 6 weeks might not have been sufficient to detect substantial differences in the immune response. While this is possible, by this age (i.e., 6 weeks) turkeys are commonly vaccinated and boosted several times in commercial practice30 indicating a functional immune system. It is also important to recognize that bornavirus-associated lesions are primarily mediated by a cytotoxic T-cell response, which was not tested in this study. Overall, the ambiguity in interpreting these immunological results stems from the absence of a clear operational method to define immune tolerance in the birds of this study. Peripheral tolerance, defined as the suppression of immune responses to self or non-harmful antigens by mechanisms such as regulatory T-cells, anergy, or deletion of reactive lymphocytes31, is particularly challenging to evaluate in birds due to the lack of reagents and standardized methodologies. Future studies employing transcriptomics or in situ hybridization to target cytokines associated with T-regulatory response development could provide more precise assessments of these mechanisms.

Throughout the study, turkeys presented with signs and gross lesions that are not attributable to orthobornavirus infection and are commonly described in commercial turkey flocks. These, therefore, were interpreted as incidental findings. Cardiovascular and musculoskeletal lesions, which either caused sudden death or prompted culling, were the most relevant contributors to the total cumulative mortality in this trial. A 2020 study of Canadian turkey farms demonstrated that in 27 flocks of tom turkeys between 7 to 14 weeks of age, the median of the cumulative mortality was 4.5% with an interquartile range of 2.8–6.3%32, a much lower figure than what was reported here. The reason for this discrepancy is unknown, although it is possible that different management styles between commercial flocks and isolation facilities might have increased the prevalence of such lesions. Maintaining adequate temperature despite appropriate ventilation, for instance, was a challenge throughout the study due to centralized temperature setting needed also for other animals. It is possible that suboptimal temperatures might have increased the rate of cardiovascular disease (especially DCM) in our cohorts33.

Despite this unexpected mortality, the number of extra birds acquired to account for attrition was sufficient to maintain the planned number of ten birds per time point. Importantly, the proportion of cardiovascular or musculoskeletal disease did not differ between infected and non-infected birds, suggesting that the infection status did not significantly affect these lesions. Nonetheless, since birds showing clinical signs were euthanized outside of the sampling schedule or were preferentially sampled at the scheduled sampling time points, bird collection in this study cannot be considered fully randomized. This may have affected the results, albeit there was no indication that incidental lesions were segregated by infectious status.

Several incidental histologic lesions were also observed. The most common consisted of small lymphocytic clusters in multiple organs with no associated tissue damage. These were interpreted as part of lymphopoiesis or ectopic lymphoid tissue and have been previously reported in several organs of poultry species and turkeys, including testis34. Except for lymphoid foci in the gonads, there was not a significant difference in the proportion of infected and non-infected birds with these inflammatory lesions. As virus RNA was detected in 7/16 gonadal tissues in the young VI cohort by 12 wpi, presence of virus infection might have promoted proliferation of already-present testicular lymphoid tissue. Overall, these lesions did not correlate with infectious status by logistic regression, suggesting that these findings were likely inconsequential to the overall pathogenesis of ABBV1.

The presence of lymphoid clusters in the heart of two young VI (positive in brain and/or spinal cord) and two old CO turkeys raised the suspicion that these might have been ABBV1-related lesions, as described in psittacines35. However, IHC for ABBV1 N protein tested negative in the available heart sections. A resolving bacterial infection (likely Escherichia coli) or reovirus infection (although no synovitis was observed) are more likely causes36,37.

In conclusion, this study indicates that turkeys are susceptible to infection with ABBV1 and occasionally develop associated clinical diseases. Viral infection appears to progress more slowly in older, larger turkeys and this could be due to the fixed rate of axonal transport of viral particles. No viral shedding was detected in this trial, but it is unclear whether this is due to the stage at which disease had progressed by the end of the study. Comparison with other similar experimental trials suggests that turkeys have an intermediate degree of susceptibility to ABBV1 infection (as evidenced by CNS and visceral dissemination), below anatids but markedly more than chickens (another gallinaceous species). Since clinical signs and inflammation of the CNS were observed exclusively in young turkeys, it seems unlikely that infection at early age may lead to an ABBV1-tolerant state, while there was no evidence that older birds may be more prone to develop immune-related disease. Future studies employing a larger time gap between age groups, or longer duration of infection, could provide more information regarding the role of age in the pathogenesis of ABBV1 in turkeys. Furthermore, transcriptomic analysis aimed at cytokines associated with development of a regulatory T-cell response could better define tolerance development in the context of ABBV1 infection.

Materials and methods

Production of infectious inoculum

The ABBV1 isolate utilized in this experiment was collected from the brain of a naturally infected Canada goose (GenBank number MK966418) and passaged in immortalized duck embryo fibroblasts (American Type Culture Collection CCL-141)38.

The infectious inoculum was produced as described previously15,16,17,24. Briefly, CCL-141 cells persistently infected with ABBV1 were grown to confluency in groups of 100 mm dishes, and the virus was released via osmotic shock (using distilled water) followed by one cycle of freeze/thaw in an ultra-cold freezer (−80 °C). The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 3000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant concentrated by precipitation with 30% w/v polyethylene glycol (PEG)-8000 overnight at 4 °C, followed by centrifugation at 3200 × g for 15 min. The pellet was resuspended in 1 × phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS) to obtain an original supernatant-to-final resuspended volume ratio of ~100:1, which was aliquoted and kept at −80 °C until inoculation. The amount of infectious virus present in the stock was quantified by preparing a series of tenfold dilutions in 2% FBS/Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; 200 µL/well, Corning, New York, United States) which were added to CCL-141 cells in an array of wells using a 96-well-plate format (100 µL per well), and incubated at 37 °C for 5–7 days. Due to the lack of cytopathic effects, the infection status of each well was determined by immunofluorescence assay, as previously described38. A 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) was calculated according to the Spearman-Karber method39 and converted into focus forming units (FFUs).

Animal experiment and sample collection

Experimental design

The layout of the experimental plan is summarized in Supplementary Fig. 1. A total of 205, 1-day-old domestic turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo domesticus) were purchased from a commercial hatchery in Ontario (Hendrix Genetics, Kitchener, Ontario, Canada) and delivered to the University of Guelph Production Animal Isolation Facility (Guelph, ON, Canada) in two groups, 6 weeks apart. The first cohort (old) consisted of 92, 1-day-old birds (80 birds plus 15% to account for attrition) that were randomly assigned into 2 rooms (virus-inoculated (VI) and control (CO), each n = 46. At 56 days of age, because of their larger size, CO birds were moved to a larger room, and those in the VI group were split between two rooms. The second cohort (young) consisted of 113, 1-day-old birds (80 birds plus 41% attrition), which were randomly assigned to an additional two rooms (VI and CO, respectively, n = 57 and 56). Increased poult numbers for attrition in the young cohort were based on increased unexpected mortality in the previous cohort. As these birds were kept for up to 12 weeks of age, additional room space was not needed.

All poults were housed in negative pressure rooms. Upon being received, poults were neck tagged, placed on the floor with wood shaving, and provided with a standardized photoperiod, as well as ad libitum access to feed and water, according to hatchery guidelines40. For the first 2 weeks, poults were kept in brooding rings and provided supplemental heat using heat lamps approximately half a meter from the floor. Feeders were checked daily and replenished as needed. Waterers were equipped with a trough, flushed daily, and refilled automatically.

In order to synchronize the time of inoculation between the two cohorts (Supplementary Fig. 1), the old cohort was kept for 6 weeks before inoculation (i.e., poults were inoculated at 6 weeks of age), while the young cohort was received from the producer 24 h before inoculation (i.e., poults were inoculated between ~24–48 h of age). A total of 40 old and 50 young turkeys were inoculated in the left gastrocnemius muscle with 6.9 × 105 FFUs of ABBV1 in 100 µL volume. The additional seven young turkeys were inoculated with the same amount of virus into 250 µL (due to a less concentrated batch of the stock), delivered in 100 and 150 µL aliquots in the left and right gastrocnemius muscle, respectively. The dose of the inoculum was selected based on previous studies from our laboratory that yielded a high degree of infection in multiple avian species15,16,17,24. The dose was maintained constant for both age cohorts, as there is no clear indication of how ABBV1 dose should be adjusted based on body mass of the birds, and it was preferred to change only one variable (age) while maintaining the dose equal. The control birds (43 old and 56 young) were inoculated with 100 µL of carrier only (PBS with 1% FBS). Intramuscular inoculation was selected as it has been demonstrated to be among the most effective methods for achieving high infection rates in animal studies involving orthobornaviruses. In contrast, mucosal inoculation consistently results in minimal to no infection41. It should be noted that the number of inoculated old turkeys is lower compared to the number initially purchased due to initial attrition before inoculation and sampling of bird sera for ELISA optimization (pre-inoculation mortalities are not reported).

Turkeys were monitored daily for the development of clinical signs for the entire duration of the study (18 weeks). Emergency euthanasia (i.e., humane euthanasia outside of the scheduled sampling time) was elected in cases of severe lameness, moderate lameness intractable to medical management, lethargy, moderate to marked decrease in body condition score, neurologic signs (any combination of head tremors, torticollis, paresis/paralysis), severe feather pecking, or ascites. These culls were classified as emergency birds. Animals with minor clinical signs, such as ruffled feathers, huddling with conspecifics, mild decrease in body condition score (based on breast muscle examination), feather pecking, mild to moderate lameness (but able to maintain access to feed and water) were monitored closely. Where medically appropriate (e.g., for lame animals), a small portion of the trial room was partitioned to create a separate pen where convalescent animals were placed and given ad libitum access to food and water. Lame animals were given daily meloxicam injections as needed (1 mg/kg, IM, alternating right and left pectoralis muscle). Pine tar was applied to animals experiencing mild to moderate feather pecking. During periods of feather pecking, photoperiod was temporarily reduced to 7 h of light per day with a light intensity of 10 lux.

Euthanasia

At 1, 4, 8, and 12 weeks post-inoculation (wpi), n = 10 turkeys from each treatment group were selected and euthanized for sample collection. At each sampling time, birds demonstrating mild to moderate signs of illness were intentionally selected, while the remaining turkeys were collected without specific criteria. Randomized selection based on neck tag number was not used to avoid the stress of handling and the occurrence of sudden deaths due to underlying cardiovascular issues (see incidental lesions). Poults that were less than or equal to 4-week-old were anesthetized with isoflurane in a 7 L vented induction chamber (VetEquip©, Livermore, California, USA) and then euthanized by carbon dioxide (CO2) inhalation. Older turkeys were weighed, and sedated (dexmedetomidine [0.03 mg/kg; Dexdomitor, Zoetis, Parsippany-Troy Hills, New Jersey, USA] and ketamine [30 mg/kg; Narketan, Vetoquinol, Lavaltrie, Québec, Canada] delivered intramuscularly), and euthanized by pentobarbital overdose (100 mg/kg; Euthasol, Virbac, Cambridge, Ontario, Canada) delivered intravenously in the right or left basilic vein.

Postmortem examination, swabs, and tissue collection

Immediately after euthanasia, 2–6 mL of blood was collected from the jugular vein using a 5–10 ml syringe, and injected into a serum-separating tube (BD Vacutainer cat#367820). Next, the choanal slit and cloaca were swabbed using sterile cotton-tipped applicators and separately placed in cryovials containing 0.7 ml of RNA preserving solution (20 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA], 25 mM sodium citrate, and 70% [weight per volume] ammonium sulfate with a pH of 5.2). For each turkey, a routine postmortem examination was conducted, gross lesions were recorded, and the following five tissues were sampled for both RNA extraction and histology (partial sampling, Supplementary Fig. 1): brain, lumbar spinal cord, kidneys, proventriculus, and gonads. Separate samples were collected either in 10% neutral buffered formalin or in 1 ml sterile screwcap tubes containing 0.7 mL of RNA-preserving solution. Samples in preserving solution were kept at −80 °C until needed for RNA extraction. For the brain, small portions of the cerebrum, cerebellum, and brainstem were collected from one half of the brain for RNA extraction, while the remaining tissue was fixed in formalin. For more complete histopathological assessment, several additional tissues were collected from three turkeys in each cohort per sampling point (full sampling). These tissues were directly fixed in formalin and included: globe, vagus nerve, brachial plexus, sciatic nerve, cervical spinal cord, thoracic spinal cord, skeletal muscle, bone marrow, spleen, skin, uropygial gland, trachea, lung, esophagus, crop, ventriculus, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, ceca, colon, cloaca, liver, bursa, thymus, Meckel’s diverticulum, thyroid gland, adrenal gland, pancreas, and heart.

Unexpected mortalities or turkeys euthanized outside of sampling schedule (emergency birds) underwent partial sampling, unless excessively autolyzed. For these birds, test results were added to those of the subsequent sampling time point for group data analysis.

Animal use approval

The Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Guelph granted approval for all experimental procedures (Animal Utilization Protocol #3978). The conducted activities adhered to the applicable regulations established by the Canadian Council on Animal Care, and are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Sample processing and data collection

Histological assessment and scoring

Tissues for histology were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and routinely processed for staining with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) by the Animal Health Laboratory histotechnology laboratory. Over the course of the trial, tissues were collected as follows: 34 birds prior to planned endpoint (20 emergency and 14 found dead birds) underwent partial sampling, 107 underwent partial sampling at the planned endpoint, and 48 underwent full sampling at the planned endpoint (Supplementary Fig. 1). Tissues were processed for histology from all the emergency birds, and all the turkeys euthanized in-time point that underwent full sampling. Of the birds euthanized in-time point that underwent partial sampling, all those euthanized at 12 wpi (n = 28) were processed, while tissues from 1, 4, and 8 wpi were not processed due to lack of CNS inflammation as seen in the full sampling birds from the same time point.

A member of the investigative team (LG) identified and tallied the microscopic lesions across all tissues and scored inflammation in the brain and spinal cord (CNS) in a blind fashion. Scoring was performed using the same rubric devised previously for chickens17. Briefly, four regions of the brain (cerebrum, cerebellum, optic lobe, and brainstem) and all available segments of the spinal cord (lumbar ± cervical and thoracic) were scored separately by assessing the average thickness of the perivascular cuffs (PVC; intensity of inflammation) and the average number of vessels affected (distribution of inflammation) in ten randomly selected 100× fields (one 100× field with F22 lens aperture = 3.80 mm2). Each region received a score (regional score, RS) that was the sum of the distribution (no PVCs, score 0; 1–10 PVCs, score 1; 11–20 PVCs, score 2; >21 PVCs, score 3) and intensity (no inflammation, score 0; 1–2 layers wide, score 1; 3–4 layers wide, score 2; >5 layers wide, score 3) scores, ranging between 0 and 6. The score for the brain and spinal cord (organ scores, OS) were calculated respectively as the simple average between all assessed brain regions (i.e., average of RS for cerebrum, cerebellum, optic lobe, and brainstem), or all assessed spinal cord segments (i.e., average RS for lumbar ± thoracic and cervical). Lesions outside the CNS were not scored, and their presence was arranged into contingency tables.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for ABBV1 nucleoprotein (N) was performed by the Animal Health Laboratory (Guelph, Ontario, Canada), and conducted in all of the tissues collected from the VI birds that underwent full sampling at 12 wpi, as well as the five young VI emergency birds collected between 8 and 12 wpi (Table 5). Immunohistochemistry for CD3 (cluster of differentiation 3; T cell marker) and PAX5 (paired box 5; B cell marker) was conducted on a single full sampling turkey sampled at 12 wpi from the young and old VI groups. These markers are commonly employed for lymphocyte identification in avian diagnostic pathology, and have been specifically shown to be expressed in tissues of chickens and turkeys42. Tissues from a single young and old control bird (T251 and T141, respectively) were used as negative controls. Positive controls, employed in each run, consisted of the brain of an ABBV1-infected Canada goose (for the N protein) and a canine lymph node (for the CD3 and PAX5 antigens). Information about the antibodies is summarized in Supplementary Table 6. Briefly, sections were mounted on positively charged slides (Fisherbrand™ Superfrost™ Plus Microscope Slides, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, United States), de-paraffinized and rehydrated, and antigens retrieved using either a citrate-based solution (pH 6) at 120 °C for 2 min, tris(hydroxymethyl)amino-methane-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (TRIS-EDTA) (pH 9) at 98 °C for 25 min, or Proteinase K (Dako, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, United States) at room temperature for 12 min. Endogenous peroxidases were quenched with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min, and non-specific binding was blocked with serum-free protein solution (Dako, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, United States). Primary antibodies were incubated at room temperature in a humid chamber, and after washes with Tris wash buffer (Dako, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, United States), sections were incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Dako, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, United States). The reaction was revealed by a chromogenic substrate (NovaRED Horseradish Peroxidase substrate; Vector Laboratories, Newark, California, United States), and sections counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted using Surgipath Micromount (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Viral RNA quantification in tissues and swabs

The presence of ABBV1 RNA in tissues and swabs was determined by RT-qPCR. RNA was extracted from ~300 µg of tissue sample and 150 µL of swab solution using the E.Z.N.A® RNA Kit II (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, Georgia, United States). The target segment of the ABBV1 N gene was amplified using a set of primers coupled with a fluorescent probe, using the Luna® Universal Probe One-Step RT- qPCR kit (New England Biolabs, Whitby, Ontario, Canada) as previously described15,16,17. Each sample was run in triplicate using a 96-well plate on a Roche LightCycler® System (Rotkreuz, Switzerland), and the cycle threshold (Ct) values were interpolated as copy numbers using a standard curve made of serial dilutions of a 500 basepair (bp) gBlock gene cassette (integrated DNA technologies) containing the target sequence of the ABBV1 N gene. A known positive sample and nuclease-free water were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The RT-qPCR output consisted of copy number per 150 ng of total RNA (for tissues), or copy number per 150 µL of swab fluid. Samples were considered positive for Ct < 35.

Serology

The blood collected from the jugular vein in the serum-separating tube was kept at room temperature and allowed to coagulate (up to 8 h post-collection). The serum was separated from the clot by centrifugation at 2000 × g for 10 min, pipetted into sterile 1 mL screw top vials, and preserved at −80 °C until used. As in previous trials, seroconversion was assessed by indirect ELISA across all groups and 1, 8, and 12 wpi time points15,16,17. A 96-well microtitre plate was coated for 2 h with recombinant full-length ABBV1 N protein (Biomatik, Kitchener, Ontario, Canada) at 25 ng/well at 37 °C and blocked overnight at 4 °C with 200 μL/well of 5% fish gelatin in PBS. Turkey serum (50 μL; diluted 1:200 in PBS-T with 1% fish gelatin) was added to the wells of the microtitre plate and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. After washes (three times with PBS-T and two times with water), a secondary goat anti-Turkey immunoglobulin Y (IgY) (H + L)-HRP conjugated antibody (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, Alabama, United States) was applied at 1:4000 dilution for 1 h at 37 °C. After a last series of washes (three times with PBS-T and two times with water) the chromogenic substrate (Pierce 1-Step Ultra TMB-ELISA Substrate Solution, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, United States) was added to the plate (50 μL/well) to detect bound serum antibodies. The chromogenic substrate reaction was stopped by addition of 0.2 N sulfuric acid solution (50 μL/well). The intensity of the signal (optical density, OD) was measured using an EnSpire multimode plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, Massachusetts, United States) at a wavelength of 450 nm. All samples were run in triplicate, and a single sample exhibiting moderate to high reactivity was run in triplicate for each plate, serving as a calibrator. To minimize variation across plates, the OD value of each well on a plate was divided by the average OD value of the calibrator wells on that plate, and then multiplied by the mean OD value of all calibrators across plates, to obtain normalized values. The threshold for classifying sera as positive, regardless of age cohort, was established as the average OD value calculated from all control sera of the young and old cohorts, plus three times the standard deviation (SD). All analyses were based on the averages from triplicate wells.

Statistical analysis

Week mortality rates were calculated using the total number of culled or spontaneously dead birds over the total number of at-risk bird weeks43. Proportions (contingency tables) were compared by Fisher’s exact test. Differences in the average pathology scores (RS and OS) or normalized (i.e., calibrated) OD values between groups and time points were tested using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by the post-hoc Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons. Group differences in the concentration of ABBV1 RNA copies (log-10 transformed) in tissues were tested by a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) fitting a full model (variables: age group and time post-inoculation), followed by Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. Analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism (version 9.5.1 for Windows, GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts USA, www.graphpad.com), with significance for all tests set at p < 0.05.

Multivariable regression analysis

Multivariable logistic regression analysis, implemented using Firth’s penalized likelihood method44, was conducted to evaluate the correlation between infectious status (Model 1) of the turkeys or inflammation (Model 2) in the spinal cord (outcome categorical variables; presence/absence), with a series of independent variables. These included age cohort (young/old, categorical variable), virus RNA amount in the bran/spinal cord (continuous), brain and spinal cord pathology scores (continuous), magnitude of seroconversion (OD values), clinical signs (categorical), and presence of incidental lesions (gross and microscopic; categorical). The magnitude of seroconversion was quantified using OD values multiplied by 100. This scaling was implemented because utilizing the raw OD values in the analysis yielded excessively large odds ratios and broad 95% confidence intervals, potentially compromising the reliability of statistical interpretations43. To avoid having categories with <5% frequency, clinical signs were grouped as a single category (presence/absence); for gross lesions, all cardiovascular and musculoskeletal lesions were merged, while DCM and ALD were kept separately. Microscopic incidental findings were classified in the following two categories: interstitial inflammation of the kidney, and interstitial inflammation of the gonads.

A relaxed p-value (p ≤ 0.2) was initially implemented to seek out explanatory variables, which were incorporated into the multivariable models if they were shown to be significantly associated with the dependent variable using univariable logistic models. Explanatory variables were assessed for collinearity by implementing pairwise Spearman’s correlation tests as in previous studies. In brief, the multivariable models were constructed with the variables with the smallest p-value when two variables were highly correlated (rho > 0.70; p < 0.05). Virus RNA concentration values were log10-converted, and all zero values (Ct value ≥ 35) were recorded as 1.0 × 10−5. Analyses were carried out using R (version 4.3.1, Vienna, Austria, http://www.r-project.org).

Responses