Patterns of spatial concentration and drivers of China’s migrant population: evidence from the Greater Bay Area hinterland

Introduction

Rapid urbanization and industrialization complement each other and have driven the urbanization rate in China to increase from less than 20% in the 1980s to more than 60% at present (He et al., 2023). In the process of industrialization, many laborers left the countryside in search of employment opportunities, forming a migrant population that accounts for 26.04% of the country’s population and has reached a total of 376 million (National Bureau of Statistics, 2021). The movement of the migrant population to economically developed areas and large cities reflects the great influence of the economic development level and employment opportunities on the spatial distribution of the population (Liang et al., 2014).

The Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA) is one of the most economically dynamic regions in China. At the beginning of the reform and opening-up period, to introduce advanced manufacturing industries from abroad and achieve rapid industrialization, mainland China adopted a form of enterprise and trade in which factories were first established, followed by processing and assembling operations supported by foreign investors. This was commonly known as the “three-plus-one” trade mix (custom manufacturing with supplied materials, designs or samples and compensatory trade)Footnote 1, which laid the industrial foundation of the GBA with manufacturing at the core (Qian et al., 2022). Moreover, small private enterprises that can quickly respond to market demand and produce labor-intensive products, such as clothing, electronic products, and toys, have become the main enterprises that lead to concentration of the migrant population, which provides labor at a low cost (Yang et al., 2021). These enterprises also became the main body of large-scale production, leading to a very dynamic economy in the GBA (Luo et al., 2022). Recently, the industrialization characteristics of the GBA have undergone great changes. On the one hand, many high-quality, talented individuals have gathered in the GBA, which has promoted the development of high-tech industries, and the traditional low-end manufacturing industry has gradually transformed into high-end manufacturing and emerging industries (Zhou et al., 2022). On the other hand, the hinterland cities of the GBA, which are dominated by labor-intensive manufacturing industries, face social governance issues in areas, such as housing, social security, educational resources and public services, for the large migrant population (He et al., 2024).

The spatial agglomeration of the migrant population is an important factor affecting the supply of public services by local governments. China’s migrant population includes adults of childbearing age who leave their place of household registration to work and live in another place. Individuals in the migrant population usually choose where to live on the basis of the available employment opportunities and income level (Huang and Cheng, 2023). These individuals then face challenges associated with tasks such as adapting and integrating (Xu et al., 2023), establishing social relationship networks (Zhang et al., 2020), developing cultural identities (Wang et al., 2020), and achieving a sense of belonging (Cormoș, 2022). Areas with a concentrated migrant population often face problems associated with the insufficient and heterogeneous distribution of public service resources (He et al., 2024).

The inclusiveness and sustainability of cities (Camerin et al. (2024)) are the basis for the localization of migrant populations. In recent years, the migration and settlement decisions of the migrant population have been influenced by three main factors. First, economic factors are considered the main drivers of migration. Huang et al. noted that members of the migrant population tend to settle in areas with many employment opportunities and high expected income (Huang and Chen, 2022). Second, the social environment, such as family relationships and education levels, often influences the migration and settlement decisions of the migrant population (Panichella et al., 2021). In addition, social networks play a role in channeling the choices of the migrant population. Good social relationships significantly increase individuals’ willingness to settle (Blumenstock et al., 2023), and support from family and friends yields information and reduces potential risks and uncertainties in the new environment (Merisalo and Jauhiainen, 2021), facilitating individuals’ rapid integration into the local community (Cimpoeru et al., 2023). Third, the level and allocation of urban amenities are important in the settlement decisions of the migrant population (Wang et al., 2021). For example, areas with convenient transportation usually attract more members of the migrant population (Reyes, 2023). The accessibility of public services (e.g., healthcare, education, and social security) is also an influential factor in the settlement of migrant populations (Cabieses and Oyarte, 2020).

Related research has several limitations. On the one hand, research on urban hinterland areas and analyses of the border areas of urban administrative districts are insufficient, and the internal mechanism underlying the agglomeration of the migrant population in urban peripheral areas has not been determined. On the other hand, in research focusing on grassroots governance units, the mechanism of grassroots governance and the effect of population agglomeration need to be further explored. That is, research focusing on the characteristics of grassroots governance units and industrial and migrant population agglomerations in urban hinterlands has important theoretical and practical value. For this reason, Dongguan, a megacity, is chosen as the empirical research object in this study. On the basis of multisource data on urban and rural grassroots governance units, this study reveals the characteristics and influencing mechanisms of the agglomeration of the migrant population in the urban hinterland of Dongguan through a theoretical analysis linking the migrant population, grassroots governance, and industrial characteristics.

Data and methods

Study area

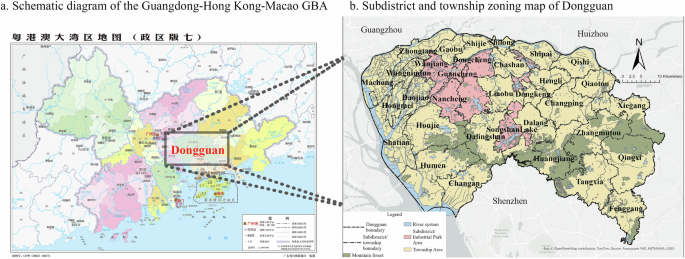

The area of Dongguan, a megacity in the hinterland of the GBA, was chosen as the study area. Dongguan is known as a “world factory” and an “international manufacturing city” and is an important manufacturing base for China and the world. Rapid development driven by foreign capital makes it a typical representative of “export-oriented urbanization” (Deng and Yang, 2021) and the earliest beneficiary of the “three-processing and one compensation” policy (Lo, 1989). As of 2021, Dongguan’s resident population was 10.5368 million, of which the migrant population was 9.0588 million, accounting for 85.97%. Among the migrant population, the number of people engaged in industry reached 7.1269 million (Dongguan Bureau of Statistics, 2022).

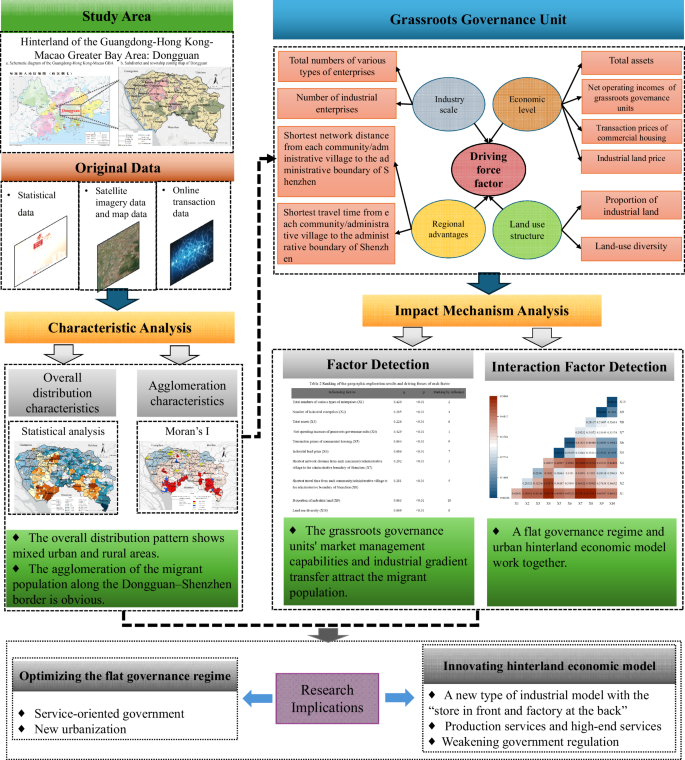

Dongguan is divided administratively at the city and township levels and is one of the four prefecture-level cities in China that do not have counties. It includes 4 subdistricts and 28 townships. This model is known as China’s Desakota model (Liao and Wei, 2014). Communities and administrative villages not only represent grassroots governance institutions but also assume the role of collective asset managers, actively participate in market economic activities, and absorb the large migrant population as the labor force. In this study, the spatial agglomeration of the migrant population is analyzed; an analytical perspective linking the migrant population, grassroots governance, and industrial characteristics is explored; the relevant influence mechanisms are analyzed in terms of economic, social, and location factors and corresponding practical policy recommendations are proposed (Fig. 1).

a Schematic diagram of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao GBA (Drawing review number: GS粤 (2023) 1023号). b Subdistrict/township zoning map of Dongguan City.

Data sources

① Statistical data. Data regarding the transient population of each community and administrative village were obtained from the official websites of Dongguan’s subdistricts and towns and from the “Digital Archives” (Dongguan Municipal People’s Government Office of Local Chronicles, 2022). Socioeconomic data for each community and administrative village were obtained from the statistical yearbook (Dongguan Bureau of Statistics, 2022). ② Satellite imagery data and map data. Electronic maps of the administrative divisions of the GBA and Dongguan city were obtained from the Guangdong Provincial Geographic Information Public Service Platform (https://guangdong.tianditu.gov.cn/, 2024/2/02), and the boundaries of each community and administrative village governed by Dongguan city were obtained from the Open Street Map (OSM) (https://www.openstreetmap.org/, 2024/3/12). Point of interest (POI) data for each community and administrative village were obtained from the Baidu Maps open platform (https://lbsyun.baidu.com/, 2024/3/20), and urban land area of interest (AOI) data were obtained from the “AOI Area Boundary Query” module (https://lbsyun.baidu.com/faq/api?title=webapi/region-search/, 2024/3/25). ③ Online transaction data. A Python tool was used to download files from Anjuke (https://m.anjuke.com, 2024/3/15) to obtain the unit price and latitude and longitude coordinates of preowned commercial housing in Dongguan in 2021. The unit price of industrial land was obtained from the Dongguan Natural Resources Bureau (Dongguan Bureau of Natural Resources, 2021).

According to the most recent official document on this subject from Guangdong Province, the definition of “migrant population” is broader than that of the “transient population”; however, the transient population is the type of migrant population that is the focus of this study, so data pertaining to the transient population are used. In summary, the basic data for 247 community units (urbanized areas) and 350 administrative village units (rural areas) in Dongguan in 2021 were obtained. However, the original data for 37 community/administrative villages were missing; thus, 560 community/administrative villages were identified as the research samples (Fig. 2).

Schematic of the study design, illustrating the multi-stage analytical framework from data collection (study area selection and original data sources) through characteristic analysis, factor detection and impact mechanism analysis. Key findings are marked with ◆, and arrows indicate the flow of analytical steps.

Variable selection and calculation

Studies show that the type of industry and the scale of development influence the number of jobs in an area (Fareri et al., 2020), which has a strong influence on the agglomeration of the migrant population (Msuya et al., 2021). Individual and household decisions are highly dependent on employment opportunities and income expectations (Chen et al., 2020), and the characteristics of employment groups are closely related to their cost of living and needs. The provision of housing and social services by the government also significantly affects the spatial distribution of the migrant population (Liang et al., 2021). Transportation accessibility should not be neglected when determining the employment-housing relationship (Yu and Zhao, 2021). On the basis of residence, living, employment, and commuting characteristics of the migrant population, ten additional factors were selected for analysis in the four areas of industrial scale, economic level, regional advantage, and land use structure.

First, the industrial scale is characterized by two factors, the total numbers of various types of enterprises and the number of industrial enterprises, which reflect the industrial status and development level of each community and administrative village. The total numbers of various types of enterprises include all registered enterprises and self-employed businesses, reflecting the overall number of employment opportunities.

Second, the economic level is characterized by four factors: total assets, the total operating income of grassroots governance units, the transaction prices of commercial housing, and the industrial land price. Dongguan’s grassroots governance entities have high autonomy in terms of business models, land use and resource allocation. The total assets refer to the sum of all assets owned by the grassroots governance units during a certain period and are used to measure the scale and comprehensive strength of the grassroots governance units participating in market economic activities. The total operating revenue of grassroots governance units is often used to support infrastructure improvement, public service provision and the enhancement of residents’ quality of life, which attracts additional private enterprises and members of the migrant population. In addition, “web transaction data” are used, and the unit prices are corrected with reference to the officially released unit price of a preowned house in Dongguan in 2021 (Dongguan Bureau of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, 2021). The benchmark land price is officially released every 3 years, and the benchmark land price of urban state-owned construction land in Dongguan city in 2019 was chosen (Dongguan Bureau of Natural Resources, 2021). According to the level and scope of industrial land, the unit price of industrial land in each community and administrative village was manually extracted to represent the industrial land price in 2021.

Third, the shortest network distance and the shortest travel time from each community and administrative village to the administrative boundary of Shenzhen were used to represent regional advantages. Using the ArcGIS pro network analysis extension module, the POIs of village and community groups were included as event points and the 31 intersections of the Dongguan–Shenzhen administrative boundary with secondary roads were selected as facility points, to calculate the shortest network distance and the shortest travel time between certain features. This can reflect the ability of grassroots governance units to obtain and utilize economic resources and services in the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone, attract inward investment and members of the migrant population, and achieve cross-border integration (Zhang et al., 2022).

Fourth, the proportion of industrial land and the Shannon index were used to represent the land use structures of the community and administrative villages. The proportion of industrial land in the total area of each community and administrative village was calculated in ArcGIS Pro, and the Shannon index was calculated to measure land use diversity (Li et al., 2023) (Table 1).

Research methods

Spatial autocorrelation analysis

Global spatial autocorrelation analysis is used to determine whether there is an overall spatial correlation associated with the distribution of the migrant population. Local spatial autocorrelation analysis was used to determine the agglomeration or dispersion of the migrant population in specific areas and to identify areas with a high- or low-density migrant population. To effectively capture the spatial continuity of the migrant population distribution, the inverse-distance spatial weight matrix was employed (Gan et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2022), which assigns greater weights to nearby communities while progressively reducing weights with increasing distance. The formula is as follows:

where wij represents the spatial weight between area i and area j, and dij denotes the Euclidean distance between the two areas.

The global Moran’s index is subsequently calculated as follows:

where N is the number of communities/villages; xi and xj denote the number of members of the migrant populations in the ith and jth communities/villages; x̄ is the overall mean of the migrant population; wij indicates the spatial weight between communities/administrative villages i and j; and W indicates the sum of the spatial weights. When the Moran’s I value is close to +1, the distribution of the migrant population has a positive spatial correlation, i.e., agglomeration; if it is close to −1, it indicates a negative correlation, i.e., dispersed population; and if it is close to 0, it indicates that the distribution is random.

The localized Moran’s I index is given by:

where Ii denotes the local Moran’s I value for the ith community/administrative village; ({sum }_{j=1}^{N}{W}_{ij}({x}_{j}-bar{x})) indicates the weighted sum of the differences between the neighboring communities/villages around the ith community/village and the overall average; and ({sum }_{i=1}^{N}{({x}_{j}-bar{x})}^{2}/N) represents the overall variance of migrant population values for all “communities/villages”.

Analysis of the association mechanism of spatial elements

Geographical detectors were used to analyze the independent effects of various quantitative factors on the spatial distribution of the migrant population. Using interaction analysis, we explored and evaluated the interactions among different factors and their common influence on the spatial distribution of the migrant population (Wang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2010).

First, with the migrant population in the research sample of 560 community/administrative villages as the explained variable and 10 specific individual factors, a geographic detector was used to analyze the influence of each factor on the spatial agglomeration of the migrant population, and the effect intensity index (q-value) and significance level (p value) of each factor in relation to the spatial agglomeration of the migrant population were obtained. The q-values were then ranked to determine the size of the univariate driving force. The q-value is calculated as follows:

where h denotes the hth class of the region; Nh and N denote the number of samples in the hth class and the overall sample size, respectively; and ({sigma }_{h}^{2}) and ({sigma }^{2}) denote the variance of the variable for category h and the whole population, respectively. The Q-values range from 0 to 1, with larger values indicating that the factor explains more of the spatial distribution.

Second, interaction factor detection was used to quantitatively describe the interactions between different factors and the effects of those interactions on the degree of migrant population agglomeration. By comparing the q-values of individual and interacting factors, it is possible to determine whether the factors enhance each other, weaken each other or are independent. This is done by first calculating the q-values of the individual factors (e.g., X1 and X2) for attribute Y, i.e., q(X1) and q(X2). Then, the interactions among these factors are assessed. For example, the layers of X1 and X2 are superimposed to form a new polygonal distribution, and the q-values after the interaction are calculated as q(X1 ∩ X2). Finally, by comparing q(X1), q(X2), and q(X1 ∩ X2), it is possible to assess the extent to which the interaction affects attribute Y and whether the explanatory power of the factor is increased or decreased after the interaction.

Study results

The distribution of the migrant population varies significantly

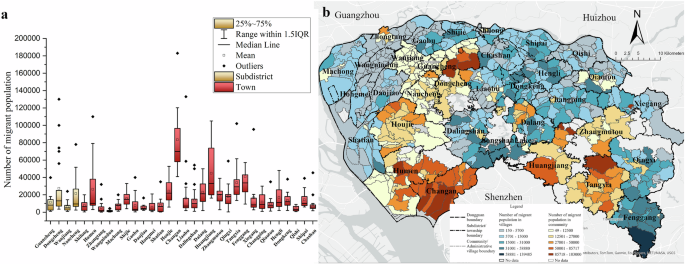

In general, the migrant population is concentrated in the central part of Dongguan, where the municipal capital is located, and along the southern edge of Dongguan, which is covered by regional transportation corridors. The density of agglomeration is lower in the western, eastern, and northern parts of the city and in the mountainous and forested areas. Chang’an town, which is adjacent to Shenzhen in southern China, has a large migrant population in all communities and administrative villages, with an average size of 83,365. In some towns, there are large differences in the number of members of the migrant population in communities and administrative villages. For example, in Fenggang town, Huangjiang town, and Humen town, the migrant population in communities/administrative villages ranges from 3000 to 105,000. Some communities/administrative villages have extremely large migrant populations, far exceeding those of other communities/administrative villages in the same town or subdistrict. For example, the Shatou community in Chang’an town and the Zhushan community in Dongcheng subdistrict have migrant populations of 183,000 and 130,000, respectively. (Fig. 3a).

a Characteristics of size differences of the migrant population in subdistricts/townships in Dongguan (2022). b Distribution of the migrant population in Dongguan by community/administrative village (2022).

Communities tend to have a slightly larger migrant population than administrative villages do. Although the Seventh Census shows that the urbanization rate of Dongguan’s 10,466,600 permanent residents is 92.1%, among the migrant population, 4,204,900 people are distributed in administrative villages in rural areas, accounting for 46% of the total migrant population. This finding indicates that the integration of “three-plus-one-supplement” enterprises with rural collectives and private enterprises has been successful, creating many employment opportunities. Moreover, the cost of living in rural areas is relatively low, which meets the needs of the migrant population, and the mixing of urban and rural spaces is conducive to the development of a diversified economy and a vital local economy (Fig. 3b).

Clear agglomeration of the migrant population along the Dongguan–Shenzhen border

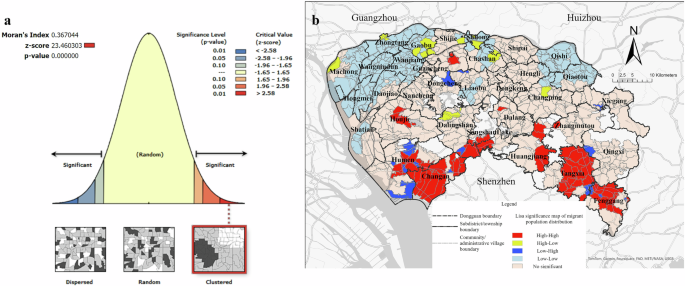

The global Moran’s I for the migrant population in Dongguan’s communities/administrative villages is 0.37, the p value is less than 0.01, and the z value is 23.46. These results suggest that the spatial distribution of the migrant population in Dongguan has a significant agglomeration value; spatial units with large geospatial agglomeration values are associated with large population agglomerations (Fig. 4a).

a Global Moran’s I result. b Local Moran’s I result.

The local Moran’s I was also calculated. High values of migrant population agglomeration are mainly observed in the eight towns in the southern part of Dongguan, near the boundary of Shenzhen (Humen, Chang’an, Dalang, Dalingshan, Huangjiang, Tangxia, Fenggang, and Zhangmutou), whereas the low values are distributed mainly in the towns in the northwest (Machong, Zhongtang, Wangniudun, Gaobu, Wanjiang, Daojiao, Hongmei, and Shatian) and northeast (Qishi, Qiaotou, Shilong, and Chashan), which are adjacent to Guangzhou and Huizhou. The outliers (LH and HL) have irregular distributions. These results suggest that, compared with Guangzhou and Huizhou, the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone and its industries have greater spatial spillover effects on townships in the southern part of Dongguan. With good industrial and supporting resources and the advantage of inexpensive land, this area attracts a large migrant population and maximizes the advantages of an inexpensive labor force (Fig. 4b).

Factors and mechanisms influencing the distribution of the migrant population

Impact analysis of major factors

-

1.

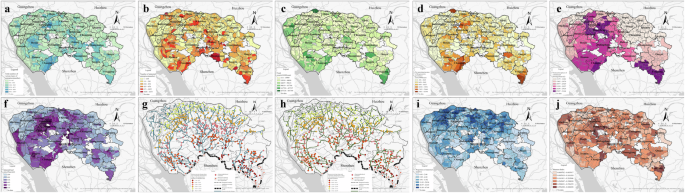

The “total numbers of various types of enterprises” indicates the attractiveness of an area to the migrant population. The Dongcheng subdistrict, where the central city is located, has a relatively high concentration of enterprises of all types, with an average of 8051 to 16,087 businesses. There is a positive correlation between the number and size of the enterprises and the size of the migrant population (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5: Analysis of influencing factors with the community/administrative village as the statistical unit.

a Total numbers of various types of enterprises. b Number of industrial enterprises. c Total assets. d Net operating incomes of the grassroots governance units. e Transaction prices of commercial housing. f Industrial land price. g Shortest network distance from each community/administrative village to the administrative boundary of Shenzhen. h Shortest travel time from each community/administrative village to the administrative boundary of Shenzhen. i Proportion of industrial land. j Land use diversity.

-

2.

The “number of industrial enterprises” reflects the characteristics of Dongguan as a “world factory” that is involved in international industrial transfer. At present, more than 20 townships with specialized industries have been established in Dongguan, such as the clothing industry in Humen, the shoes industry in Houjie, the furniture industry in Dalingshan, and the molding industry in Hengli. Communities and administrative villages can have as many as 1036 to 1673 industrial enterprises; such communities with many enterprises include the Jiangnan community in Zhongtang town, the Changtang community in Dalang town, the Meitang community in Huangjiang town and the Shigu community in Tangxia town. Communities under the jurisdiction of subdistricts tend to attract more enterprises than administrative villages under the jurisdiction of townships do, reflecting the fact that the levels of infrastructure and public services affect the distributions of industrial enterprises and the migrant population (Fig. 5b).

-

3.

The “total assets” at the community/administrative village level reflect the scale of collective assets. These total assets, which can range from 170 million to 810 million yuan, are the basis on which grassroots governance actors participate in the market economy and obtain various types of rents and fees, and they are correlated with the operational effectiveness of the enterprises that have been attracted to the area and the scale of job creation (Fig. 5c).

-

4.

The “net operating incomes of the grassroots governance units” reflect the level of marketization and services provided by the grassroots governance units. This measure is highly correlated with the total assets at the community/administrative village level, which are 250 million to 650 million yuan at most. As grassroots governance actors in Dongguan are both public service providers and participants in the market economy, their ability and effectiveness in managing collective assets are often among the factors attracting businesses and the migrant populations to an area (Fig. 5d).

-

5.

The “transaction prices of commercial housing” reflects the cost of living and the level of various facilities in an area. The commercial housing in Dongguan’s central city (including the four subdistricts of Nancheng, Guancheng, Dongcheng, and Wanjiang) and in the areas adjacent to Shenzhen has a higher price than in other regions, with average unit prices ranging from RMB 25,827 to RMB 31,144 (Fig. 5e).

-

6.

The “industrial land price” reflects the development potential of industrial enterprises. The four subdistricts in the central city and the townships of Liaobu and Dalang around Songshan Lake Science and Technology Industrial Park have the highest industrial land price. In 2017, the industrial land bidding, auction, and listing system was first implemented in Dongguan city, marking an important stage of China’s land system reform (Zhang et al., 2017). The “zero land value” investment strategy for industrial land is prohibited (Zhang et al., 2017). The “industrial land price” reflects the continued attractiveness of industrial firms to the migrant population (Fig. 5f).

-

7.

The “regional advantage” reflects the industrial characteristics and development patterns of the hinterland of the GBA. The shortest network distance from each community/administrative village to the administrative boundary of Shenzhen ranges from 1.1 to 49.86 km. The communities/administrative villages in the nine southern townships are generally within 15 km of the Shenzhen administrative boundary. The Yongtou community resident committee of Chang’an township in southern China is only 1 kilometer away from the Shenzhen Bao’an district boundary, and it takes only 2 min to drive there. Through the influence of the Special Economic Zone’s policies and industrial spillover effects, coupled with low land price and rents and relatively loose government controls, the eight southern townships have attracted many enterprises and a large migrant population (Fig. 5g, h).

-

8.

The “proportion of industrial land” reflects the main types of industries in an area. The proportion of industrial land is ~30%; the communities and administrative villages with relatively high proportions are located in northwestern and northeastern Dongguan, with maximum proportions of 41.04–67.68%. This reflects the fact that Dongguan has a high degree of industrialization and a relatively homogeneous economic structure, with manufacturing as the main industry. Small, diversified private and collective economies, together with a large migrant population, form a typical economic model in the urban hinterland (Fig. 5i).

-

9.

The “land use diversity” reflects the degree of urbanization and the level of community services. The Shannon index is positively correlated with the level of urbanization, and both indices are high in the Xiaobian community in Chang’an town, the Xianxi community, and the Jinxia community. Areas with low land use diversity are more suitable for manufacturing agglomeration and generally face environmental and public service level problems. The distribution of the migrant population is not entirely consistent with this trend (Fig. 5j).

Explanatory ranking of the main factors

The p-value of each factor is less than 0.01, indicating that the influence of each factor passes the significance test. Second, on the basis of the q-value, the 10 main factors can be ranked from greatest to least explanatory power (Table 2).

The factor of the “net operating incomes of the grassroots governance units” (0.429) has the strongest explanatory power and thus has the largest influence on the distribution of the migrant population.

Next, the “total numbers of various types of enterprises” (0.420) and the “number of industrial enterprises” (0.285) rank second and fourth, respectively. This indicates that Dongguan’s grassroots governance subjects have created many jobs by concentrating on labor-intensive industrial enterprises, and the large number of enterprises indicates a high degree of flexibility and variability in economic development. Moreover, the threshold requirements for such jobs are low, and the migrant population is a suitable labor resource.

The third, fifth and sixth highest-ranked factors are the “shortest network distance from each community/administrative village to the administrative border of Shenzhen” (0.292), “shortest travel time from each community/administrative village to the administrative border of Shenzhen” (0.281) and “total assets” (0.226), respectively. Dongguan’s economy is strongly influenced by Shenzhen, which is a typical model in the urban hinterland economy. On the one hand, Dongguan enjoys the spatial spillover of Shenzhen’s policy effects, and on the other hand, the two have a certain degree of complementarity. The industrial land in Shenzhen is constrained by the scale of spatial resources, which can no longer meet the needs of enterprises seeking to expand production (Liu and Liu, 2020), and some enterprises have gradually moved to Dongguan. The research and development (R&D) headquarters of these enterprises remain in Shenzhen, whereas their manufacturing facilities are located in Dongguan. Such changes have formed a new type of industrial model with the “store in front and factory at the back” (Wang et al., 2024).

Fourth, the explanatory power of “industrial land price” (0.086), “land use diversity” (0.069), and “proportion of industrial land” (0.063) in relation to the spatial distribution of the migrant population is low. This means that there are still many low-end manufacturing industries in Dongguan, and they are located in relatively remote areas, where much industrial upgrading and economic restructuring are necessary.

Finally, the explanatory power of the “transaction prices of commercial housing” (0.064) is also low. Owing to their profitability, grassroots governance bodies take the initiative to improve the quality of service and livability to attract better enterprises and skilled labor, which objectively increases the price of commercial housing. In contrast, members of the migrant population, who have a low income level, choose to live in houses with low rents and rely on commuting to solve the problem of work-living separation (Peng, 2021). In addition, many members of the migrant population choose to live in factory dormitories and do not desire to become “citizens”.

Enterprise size, grassroots governance capacity, and regional advantages are key factors

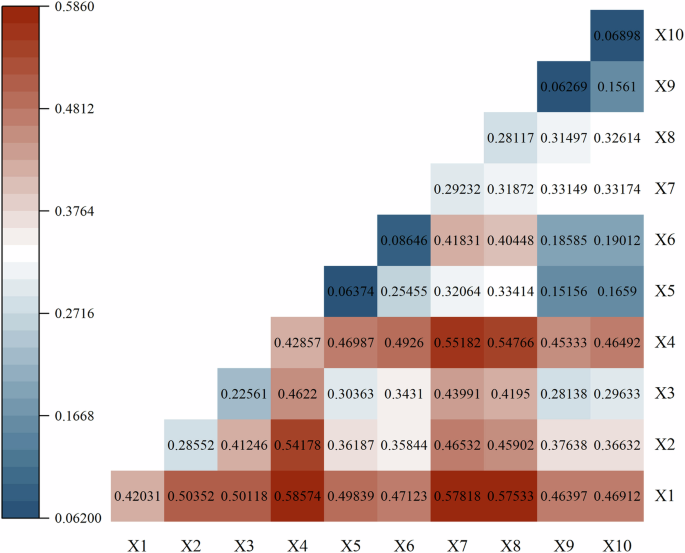

The effect of interaction between the driving factors on the spatial distribution of the migrant population indicates two-factor enhancement and a nonlinear enhancement relationship. The influence of any two selected influencing factors after they interact has greater explanatory power than the influence of the two original individual factors (Fig. 6).

Matrix showing pairwise interactions among ten driving factors (X1–X10) related to the spatial distribution of the migrant population. The color scale indicates the magnitude of interaction between each pair of factors, with darker shades representing stronger interaction effects.

The interaction effect between the “total numbers of various types of enterprises” and the “net operating incomes of the grassroots governance units” is the strongest (0.58574). The effects of these two factors are enhanced via interactions with other factors, such as interactions with the “shortest network distance from each community/administrative village to the administrative border of Shenzhen”, the “shortest travel time from each community/administrative village to the administrative border of Shenzhen”, the “number of industrial enterprises” and the “total assets”.

In addition, the “shortest network distance from each community/administrative village to the administrative border of Shenzhen” and the “shortest travel time from each community/administrative village to the administrative border of Shenzhen” have strong interactions with the “total numbers of various types of enterprises”, “net income of grassroots governance units”, “number of industrial enterprises”, “total assets” and “industrial land price”, with the explanatory power regarding the migrant population distribution exceeding 40%. This suggests that the grassroots governance units neighboring Shenzhen have attracted more enterprises, gained higher revenues, and become more attractive to the migrant population than other parts of Dongguan.

Discussion and conclusions

Main conclusion

First, the distribution of Dongguan’s migrant population is generally concentrated in the city center and southern areas adjacent to Shenzhen, with a higher density in the central and southern parts of the city and a lower density in the northwest and eastern areas. Moreover, the migrant population shows a mixed distribution pattern between urban and rural spaces.

Second, the grassroots governance bodies of communities/administrative villages actively participate in market economic activities by utilizing their collective assets, attracting industrial enterprises, and increasing the comprehensive capacity of the district service level and supporting facilities on the basis of the revenue gained. These factors have become the main factors attracting the migrant population. The governance regime with two levels of urban government provides the institutional framework for this process.

Third, Dongguan has industrial characteristics typical of the urban hinterland. Owing to its location adjacent to Shenzhen and convenient regional transportation, Dongguan has a unique regional advantage. With the advent of the “store in front and factory at the back” industrial model in Shenzhen, business operations are becoming more flexible and diversified, offering unique industrial advantages. The profit model and income expectations have attracted a large transregional migrant population.

Challenges for grassroots governance in Dongguan

Dongguan has a larger migrant population than other cities do; 98% of this population is engaged in industrial production, and it is mainly distributed in the southern townships near the Dongguan–Shenzhen administrative boundary. This confirms the observed pattern that the migrant population tends to agglomerate at city boundaries (MacLachlan and Gong, 2022; Xu et al., 2022). Moreover, even though Dongguan has a high urbanization rate, the migrant population still displays localized urban-rural spatial intermixing and mixed agglomeration under the general trend of urban agglomeration (Qiang and Hu, 2022). This pattern is related to Dongguan’s unique flat government governance structure.

The flat government governance structure overcomes the “isolation” between urban and rural areas. Dongguan is one of the four prefecture-level cities in China that do not have a county (district) administrative level. Instead, the city government directly manages grassroots governance units, reducing the need for district-based administrative management. The grassroots “community/village” governance unit organically integrates the governance body and the collective economic management body and thus has greater power and space for free development; through active participation in economic activities, such as industrial production, the rural areas of Dongguan have developed in a way comparable to that of urbanized areas, resulting in the same manufacturing capacity and vitality (Pugh and Dubois, 2021), creating many job opportunities (Huang et al., 2021) and promoting urban‒rural integration (Yang et al., 2020). This governance structure has promoted the free flow of capital, enterprises, and population, making Dongguan a suitable space for absorbing a specific type of migrant population.

Grassroots governance units must balance the responsibilities of participating in the market economy and providing public services, which causes them to prioritize the principle of “efficiency first” in resource allocation. Although the market economy and services of a community may be thriving, there may be deficiencies in ensuring a fair and just public service supply. Not only are there limitations in resolving unbalanced regional development, but it is also difficult to find a balance between promoting rural development and protecting the basic rights and interests of urban and rural residents (Zhao and Wang, 2022). To better adapt to ensure the long-term sustainable development of cities, public service mechanisms must be adjusted and optimized in future development efforts.

Dongguan’s flexible and diversified collective economy

The collective economy in Dongguan has developed in specific ways. Grassroots governance units have the flexibility to formulate development strategies on the basis of market needs and government policies, with the following results. First, they can quickly adjust and optimize the allocation of resources to be the first to attract enterprises and investments. For example, in Yantian village, Fenggang town, 60 modern industrial parks have been built, and more than 5800 mu of “industrial-to-industrial park” renovation projects have been completed, attracting many enterprises. As a result, many members of the migrant population have come to these areas to work and have sought places to live nearby. Second, although an enterprise may be small, its overall employment capacity can be large. The presence of many small enterprises and microenterprises leads to more diversified commercial and economic activities and the formation of a business cluster with diverse and evolving effects, which increases economic vitality and improves the ability to adapt to development risks, forming an intrinsic positive growth mechanism, and naturally promoting job opportunities (Du et al., 2021). Third, improvements in the level of industrialization have driven the service industry and other related industries. Local governments have further implemented policy guidance and model-driven and performance-driven measures to create a virtuous economic cycle. For example, by revitalizing inefficient idle land and asset properties, the Shangjia community in the Wanjiang subdistrict achieved a significant increase in total income and paid dividends to shareholders for the first time, further enhancing the attractiveness of rural communities to the migrant population.

This study also shows that only when multifactor interactions occur can Dongguan’s advantages be fully utilized (Ma et al., 2022). For example, the proportion of industrial land use and land use diversity significantly positively influence the explanatory power of the spatial distribution of the migrant population when these factors interact with variables such as the total numbers of various types of enterprises and the net operating incomes of grassroots governance units. This suggests that the grassroots governance units in Dongguan play a large role in economic and social development because they are the holders of collective assets, and the most important collective asset is collective land. This autonomy over collective land transfer, leasing, and value sharing enables rapid local development, and the attraction of investment brings about economic development and optimization of the industrial structure (Yang et al., 2022). In other words, a large amount of industrial land leads to the a concentration of industrial enterprises with sufficient job opportunities and positions available (Guo et al., 2024). High land use diversity refers to industrial diversification, which involves not only diversified enterprise categories but also the development of various service industries; thus, regional competitiveness and attraction are strong (Xia et al., 2020).

In general, the high mobility of capital, enterprises, and the population, which fits the development pattern of “people, land and wealth” at the level of grassroots governance units, forms an integrated development model for Dongguan as a megacity, with the characteristics of high economic vitality and a large migrant population. The typical characteristics of urban development are evident in the hinterland of the GBA.

Research limitations

Although we use data from the country’s first community/administrative village level township yearbook, the short and asynchronous release of continuous multiyear data for the whole region prevented the implementation of a study based on panel data to reveal detailed impact mechanisms. Additionally, the use of precise and effective spatial analysis methods adapted to the characteristics of the data was limited. To address this limitation, first, longitudinal studies targeting specific and typical subdistricts, towns and enterprises could be conducted. Second, migrant populations often exhibit highly complex economic, social, and cultural dynamics at the micro level, and fine-scale and real-time data are needed for related analyses. To address this limitation, statistical data, mobile phone signaling data, and objective sensing data can be combined to form a big data foundation that can significantly contribute to identifying the spatiotemporal clustering characteristics of the migrant population and their associations with individual social attributes, ultimately supporting detailed structural analysis. Furthermore, to improve both the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the data, it is crucial to optimize research methods, such as spatial analysis, to better align with the specific characteristics of the data. Techniques based on deep learning and neural networks, for instance, can be used to identify complex underlying driving mechanisms by identifying patterns within large-scale datasets. Finally, future studies could focus on governance measures with local characteristics, for example, by examining the problems faced by the migrant population in terms of employment, residence and economic activities in the “new types of communities” established in various subdistricts and towns.

Prospects

Dongguan, a city in the hinterland of the GBA, provides strong evidence validating the usefulness of the analytical framework linking the migrant population, governance, and industrial characteristics. The migrant population is an important component of regional development and is closely related to local governance patterns and industrial development characteristics; these three factors are mutually reinforcing and cyclical. Providing comprehensive local public services for the migrant population and industrial development is a major task for governments at all levels in the hinterland cities of the GBA. With the continuous iteration of information technology, smart cities and big data technology will provide new ways to increase the level of public services. Achieving cross-regional collaborative governance, improving social security for the migrant population, and improving the living environment and quality of life are the basis for increasing the economic vitality and attractiveness of the GBA and promoting social progress, harmony, and sustainable development.

Responses