Perennial flower strips in agricultural landscapes strongly promote earthworm populations

Introduction

Soil is estimated to be the most biodiverse habitat on Earth, harboring approximately 59% of all species1. Soil organisms vary several orders of magnitude in body size and assemble in complex communities, which contribute to essential ecosystem functions2. Yet, the loss of biodiversity in agricultural soils through agricultural intensification3 threatens the provision of multiple ecosystem functions4,5. Consequently, restoration and protection of soils have become key objectives of political agendas6. Agricultural diversification is considered an effective leverage to achieve the goals of these agendas. For instance, spatial and temporal agricultural diversification measures have been shown to promote ecosystem services such as soil fertility, water regulation, nutrient cycling as well as biodiversity without compromising yield7. Integration of semi-natural habitats (e.g., ecological focus areas) into agricultural landscapes is a well-established spatial diversification measure that is financially supported by the European Union8. Especially the incorporation of flower strips has numerous aboveground benefits9, including increased natural pest control10, biodiversity11, and pollination services12. In 2018, flower strips covered approximately 1% of Germany’s total arable land13; however, their impact on soil communities remains largely unknown.

Soil microorganisms are key drivers of soil nutrient cycling and plant productivity14 and account for a large share of soil biodiversity. In 2016, D’Acunto and colleagues15 compared the functional diversity of heterotrophic soil bacteria in soybean fields to those in herbaceous and woody field margins. The authors found that functional diversity increased from soybean fields to herbaceous to woody field margins15. These findings agree with a recent review article that found that incorporating woody perennials into agricultural systems (i.e., agroforestry) benefits the abundance, diversity, and functions of soil microbial communities16. Compared to woody perennials, soil microbial communities in perennial flower strips received substantially less attention. In a recent study, we demonstrated that two years post establishment, the population size and alpha diversity of soil bacteria and fungi do not differ among annual and perennial flower strips, as well as field margins17. However, we were able to show substantial differences in microbial community composition among annual and perennial flower strips and grassy field margins, which we attributed to differences in tillage regime (tillage for the re-establishment of the annual flower strips vs. no tillage in the field margins and perennial flower strips), as well as plant diversity (field margins < annual flower strips < perennial flower strips)17.

Earthworms are an integral part of soil communities and contribute to numerous functions in agroecosystems. For instance, earthworms are known to enhance water infiltration18, increase aggregate formation19, and can improve plant health through their ability to increase soil nutrient availability20 and suppress phytopathogens21. Not unlike overall soil biodiversity, earthworms are threatened by agricultural intensification22 and their abundance and diversity in arable land declined over the last decades23. Since earthworms are negatively affected by narrow crop rotations24 and intensive soil tillage25,26, spatial diversification through the establishment of perennial semi-natural habitats can promote earthworm communities. For instance, in 2011 Nieminen et al.27 investigated earthworms in 50 field margins and adjacent croplands and found increased population densities as well as altered community compositions in the margins as compared to the croplands. Similarly, Crittenden et al.28 and Holden et al.29 reported increased earthworm population densities in field margins as compared to adjacent fields. Similarly, Smith et al.30 and Frazão et al.31 found overall positive effects of field margins on earthworm communities. Both studies, however, emphasized the importance of field margin management (e.g., mowing frequency) for earthworm communities30,31. Since perennial flower strips receive similar management as field margins, it is reasonable to assume that perennial flower strips benefit earthworm communities. Yet, studies confirming this assumption remain scarce. In 1999, Kohli and co-authors32 reported positive effects of a perennial wild flower strip on earthworms. Likewise, in a more recent study, we were able to show that perennial flower strips harbored more earthworms than grassy field margins and annual flower strips17. However, studies comparing soil communities in perennial flower strips to those in adjacent croplands are yet missing.

Here, we conducted the first study comparing earthworms and soil microorganisms in perennial flower strips to those in adjacent croplands. We investigated earthworm communities and soil microbial groups in paired croplands and perennial flower strips at 46 study sites across Germany covering a wide range of soil properties. We hypothesized that i) perennial flower strips harbor greater abundance of earthworms as compared to adjacent croplands and that ii) the composition of earthworm communities in perennial flower strips differed from those in adjacent croplands. Furthermore, we iii) expected no alteration of the population size of microbial groups in response to the incorporation of flower strips.

Results

Soil properties

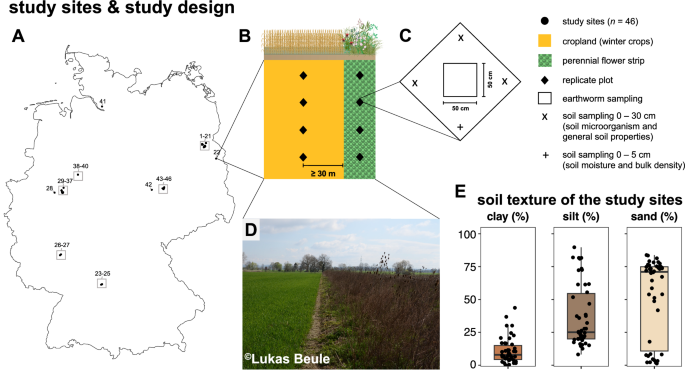

Our 46 study sites covered a wide range of soil texture classes ranging from 1.3 to 83.8% sand content (Fig. 1E). SOC and pH ranged from 0.46 to 3.79% and 4.86 to 7.65, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1A, C). Soil properties (SOC, total N, pH, and bulk density) did not differ between flower strips and adjacent croplands, except for slightly higher soil pH in the flower strips (6.39 ± 0.61) as compared to the croplands (6.24 ± 0.65) (Supplementary Fig. S1C), which is expected to be related to marginal within-site heterogeneity. Gravimetric soil water content in perennial flower strips was on average 14.1% greater than in adjacent croplands (p < 0.001).

Location of the 46 study sites across Germany (A), study design (B), schematic overview of soil and earthworm sampling at each replicate plot (C), exemplary photo of one of the studied perennial flower strips and its neighboring cropland (D), and the range of soil texture (i.e., clay, silt, and sand content) of the study sites (E). Illustrative icons are courtesy of the Integration and Application Network (ian.umces.edu/media-library). Map was created using Natural Earth (naturalearthdata.com).

Earthworm communities

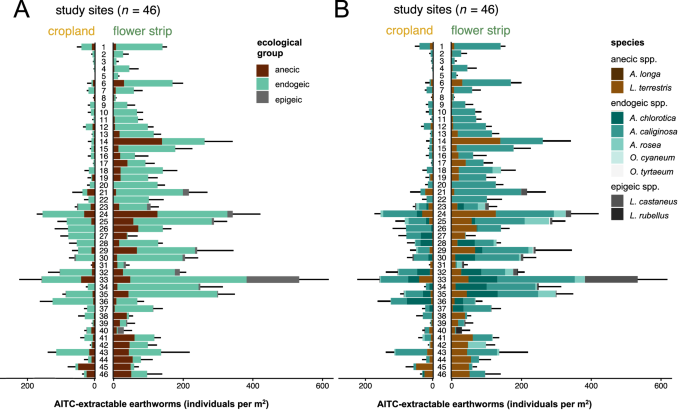

We collected 7526 earthworm individuals of nine different species across 46 study sites. Earthworms were classified into three ecological groups (i.e., anecic, endogeic, and epigeic) as introduced by Bouché33, which comprised two anecic species (Aporrectodea longa and Lumbricus terrestris), five endogeic species (Allolobophora chlorotica, Aporrectodea caliginosa, Aporrectodea rosea, Octolasion cyaneum, and Octolasion tyrtaeum), and two epigeic species (Lumbricus castaneus and Lumbricus rubellus) (Fig. 2B). While endogeic species were present at all 46 study sites, anecic and epigeic species were found at 42 and 14 sites, respectively (Fig. 2A). Anecic species were dominated by L. terrestris while A. longa was only found at two study sites (site 23 and 32). Endogeic communities were dominated by A. caliginosa and A. chlorotica, except for site 31 and 42 where A. rosea contributed the largest share of endogeics. O. cyaneum and O. tyrtaeum, however, were only found at sites 25 and 29 (Fig. 2B). Epigeic communities were dominated by L. castaneus, which was found at 12 study sites, while L. rubellus was only found at six sites (Fig. 2B).

Mean earthworm population density and standard deviation (n = 4) for all allyl isothiocyanate (AITC)-extractable earthworms in paired croplands and perennial flower strips over all 46 study sites. Opposing bars represent paired croplands and perennial flower strips (i.e., study sites) with different colors representing (A) different ecological groups (i.e., anecic, endogeic and epigeic) or (B) different species (Allolobophora chlorotica, Aporrectodea caliginosa, Aporrectodea longa, Aporrectodea rosea, Lumbricus castaneus, Lumbricus terrestris, Lumbricus rubellus, Octolasion cyaneum and Octolasion tyrtaeum).

At all study sites, earthworms were present both in the perennial flower strip and adjacent cropland, except at site 5 at which earthworms were only found in the flower strip but not in the adjacent cropland (Fig. 2). Across all study sites, total earthworm population density was on average 231% greater in the flower strips than in the adjacent croplands. We found a consistently positive effect of flower strips on total earthworm population density at 44 out of 46 sites (Fig. 3A).

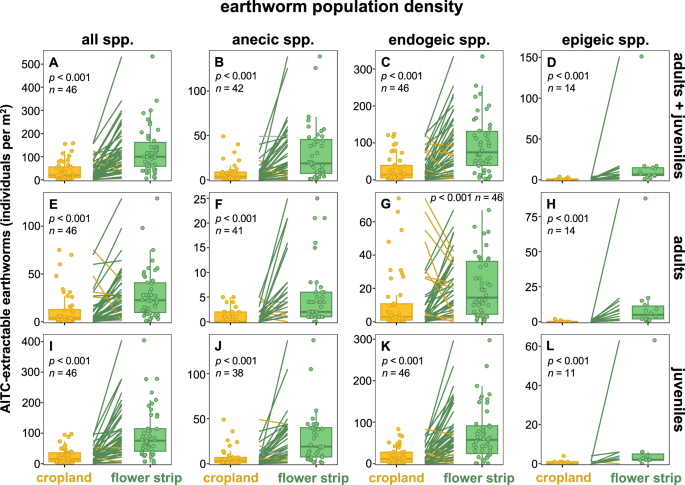

Population density of all (A, E, I), anecic (B, F, J), endogeic (C, G, K), and epigeic (D, H, L) allyl isothiocyanate (AITC)-extractable earthworms in paired croplands and perennial flower strips. Dots represent the mean of four replicate plots per site and management system (i.e., paired cropland or perennial flower strip) at which earthworms were extracted from ¼ square meter. Lines connect paired croplands and flower strips (i.e., study sites) with green lines indicating greater, yellow lines lower, and gray lines an identical population density in the flower strip as compared to the corresponding cropland. p-values were obtained from linear mixed effect models. n represents the number of study sites at which the respective ecological group and developmental stage of earthworms was present.

The increase in total population density through flower strips was consistent across developmental stages as adult and juvenile earthworms showed on average 2.3 and 3.9 times greater population densities in the flower strips as compared to the croplands, respectively (Fig. 3E, I). The same patterns were also observed for adult and juvenile earthworms of all three ecological groups (Fig. 3F–H, J–L). The juvenile-to-adult ratio of endogeic earthworms was on average 53% greater in perennial flower strips than in adjacent croplands across all 34 sites at which juvenile and adult endogeic earthworms were found in both management systems (Supplementary Fig. S2C). For anecic earthworms, no difference in the juvenile-to-adult ratio between paired flower strips and croplands was found (Supplementary Fig. S2B).

At nine study sites, anecic species were absent in croplands but present in flower strips where they established populations ranging from 1 to 71 individuals m−2 (Fig. 2A). Across all study sites, population density of anecic earthworms increased on average by 301% through flower strips (Fig. 3B). Similar patterns were observed for endogeic earthworms, which were present at all study sites but absent in the cropland of site 5, 8, and 31 at which they showed population densities of 13, 4 and 18 individuals m−2 in the corresponding flower strip, respectively (Fig. 2A). Across all study sites, flower strips harbored on average 208% more endogeic earthworms than adjacent croplands (Fig. 3C). At eight sites, epigeic species established populations ranging from 1 to 17 individuals m−2 in the flower strips but were absent in the corresponding croplands (Fig. 2A). At the 14 sites that harbored epigeic earthworms, population density was on average 23.6 times greater in the flower strip as compared to the adjacent cropland (Fig. 3D). This strong increase was driven by site 33 at which the population density of L. castaneus increased from 1 individual m−2 in the cropland to 133 individuals m−2 in the adjacent flower strip (Fig. 2B).

Earthworm biomass correlated strongly with earthworm population density (Supplementary Fig. S3, rho = 0.893, p < 0.001) and consequently showed similar patterns between flower strips and croplands across all ecological groups and developmental stages (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Soil microorganisms

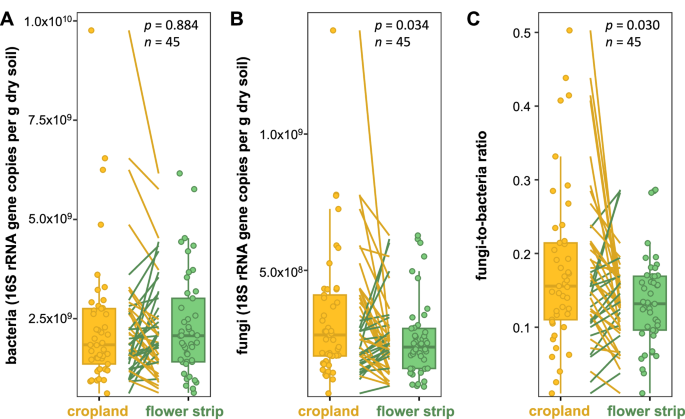

DNA was successfully extracted from soil samples of 45 out of 46 study sites. Across those 45 sites, soil bacterial and fungal gene abundance were positively correlated (rho = 0.434, p < 0.001). Population size of soil bacteria did not differ between flower strips and croplands (Fig. 4A). Likewise, no effect was observed for the abundance of N2O reducers (nosZ clade I and II genes, which were successfully quantified at 44 and 33 study sites, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. S5). Average population size of soil fungi was slightly greater in croplands compared to the adjacent flower strips (Fig. 4B), which led to a greater fungi-to-bacteria ratio in croplands than in flower strips (Fig. 4C). The fungi-to-bacteria ratio was negatively correlated with SOC (rho = −0.61, p < 0.001, Supplementary Fig. S6A) and soil pH (rho = −0.52, p < 0.001, Supplementary Fig. S6B).

Bacterial 16S rRNA (A) and fungal 18S rRNA gene abundance (B) and their ratio (fungi-to-bacteria ratio) (C) in paired croplands and perennial flower strips. Dots represent the mean of four replicate plots per site and management system (i.e., paired cropland or perennial flower strip). DNA was extracted from soil samples collected at 0–30 cm soil depth. Lines connect paired croplands and flower strips (i.e., study sites) with green lines indicating greater and yellow lines lower gene abundance (A, B) or fungi-to-bacteria ratio (C) in the flower strip as compared to the corresponding cropland. p-values were obtained from linear mixed effect models. DNA was successfully extracted from croplands and flower strips at 45 out of 46 study sites.

Discussion

General soil properties (SOC, total N, soil pH, and bulk density) did not differ between paired croplands and perennial flower strips, except for slight differences in soil pH, which are expected to be related to marginal within-site heterogeneity (Supplementary Fig. S1). A recent study by Harbo et al.34 determined SOC stocks in topsoil at 0–10 and 10–30 cm soil depth in 23 paired flower strips (four annual and 19 perennial flower strips) and croplands across Germany. While the authors reported greater SOC stocks in the flower strips than croplands at 0–10 cm soil depth, SOC of stocks at 0–30 cm (0–10 and 10–30 cm added) did not show statistically significant differences between flower strips and croplands. Nevertheless, at 15 out of 23 sites of Harbo et al.34, mean SOC stocks at 0–30 cm soil depth were greater in the flower strips than croplands, which is congruent with our findings where 24 out of 46 sites showed greater SOC concentrations at 0–30 cm soil depth in perennial flower strips as compared to croplands. It has to be noted though that in contrast to Harbo et al.34, we did not aim to quantify SOC stocks which would have required a different sampling strategy.

Soil moisture is a strong driver of soil microorganisms35 and earthworms36 as well as agricultural productivity. Projections of future soil moisture dynamics under different climate change scenarios predict that droughts will increase in duration and frequency in Europe and Germany37,38, making it ever more important to retain soil water within landscapes. At the time of sampling, we detected on average 14.1% greater gravimetric soil water content in perennial flower strips than croplands (Supplementary Fig. S1E), which suggests that perennial flower strips help to retain soil water in agroecosystems. It has to be noted though that although we collected samples at 46 study sites, our sampling of soil moisture content comprised the upper 5-cm topsoil only and was limited to a single sampling event in spring 2023. To understand changes in soil moisture in response to perennial flower strips, further studies that include measurements of soil moisture dynamics across soil depths and time are required.

Perennial flower strips had strong positive impact on the population density and biomass of earthworms (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Fig. S4), confirming our first hypothesis. We argue that the absence of soil management in the perennial flower strips mainly contributed to this promotion. For instance, reduced tillage is well-known to increase earthworm population density, biomass, and functional diversity25,39,40. The positive impact of reduced soil management on earthworms in perennial flower strips agrees with our previous findings, showing that compared to annually re-established flower strips, perennial flower strips and field margins strongly promote the population size of earthworms17. In the same study, we were able to show that perennial flower strips harbor more earthworms than grassy field margins, which we attributed to high plant diversity in the flower strips17. The beneficial effect of plant richness on the abundance and biomass of earthworm communities has been demonstrated before41,42 and may have contributed to the high population densities in the perennial flower strips in the present study. Since higher plant richness is generally associated with higher plant biomass43, we expect a greater provision of above- and belowground plant litter as a food source for earthworms in the flower strips as compared to the croplands. This may partly explain the observed promotion of earthworms in the perennial flower strips. Additionally, litter quality has been suggested to have an even bigger influence on soil decomposer communities than litter quantity44. Numerous studies pointed out the positive effect of plant material rich in N (e.g., legumes) on earthworm communities45,46,47. For instance, in a field trial investigating 12 cover crop and weed management combinations, Roarty et al. 48 were able to show that pea cover crops supported greater earthworm communities than other types of cover crops, underlining the importance of food quality on earthworm promotion. The strong impact of litter quality on earthworms raises questions regarding the importance of plant species composition of perennial flower strips for soil communities. Currently, efforts are undertaken to optimize floral compositions of perennial flower strips to overcome challenges related to aging (i.e., overgrowth of grasses and subsequent loss of the flowering aspect) for which wildflower mixtures with regional origin offer a promising solution49,50,51. Additionally, the floral composition of flower strips is crucial regarding their effectiveness in promoting beneficial arthropods. Consequently, tailoring flower strip mixtures towards beneficial arthropods has been a major focus of research in recent years11,52,53. For instance, Blümel and co-authors53 were recently able to show that different flower strip mixtures induce taxon-specific responses of natural enemies, highlighting the potential of optimizing flower strips for natural pest control. Yet, soil communities are not considered target organisms for optimizing the floral composition of flower strips.

Perennial flower strips increased the population density of all ecological groups of earthworms and were especially beneficial for epigeic earthworms. Population densities of anecic, endogeic, and epigeic species were increased by factor 4.0, 3.1, and 23.6, respectively (Fig. 3B–D). Furthermore, perennial flower strips led to the establishment of populations of anecic and epigeic species at 9 and 8 study sites, respectively (Fig. 2A), thereby confirming our second hypothesis. The absence of tillage in the perennial flower strips serves as a potential explanation for the promotion of anecic and epigeic species, as both ecological groups are regarded to benefit stronger from reduced tillage than endogeic species26. In addition, constant soil cover with plant material in the perennial flower strips is also likely to have contributed to this promotion as anecic and epigeic earthworms feed on organic material located at the soil surface unlike endogeic species which feed on organic material incorporated into the soil54. Indeed, constant soil cover with plant material benefits numerous earthworm species48, representing another mechanism by which perennial flower strips support earthworm communities. The promotion of anecic and epigeic species is in accordance with previous studies investigating earthworms in other perennial structures such as field margins27, and tree rows of alley-cropping systems55. Furthermore, perennial flower strips at our study sites showed greater juvenile-to-adult ratio of endogeic species than croplands (Supplementary Fig. S2C), suggesting that perennial flower strips serve as a habitat for reproduction of this ecological group of earthworms. The absence of tillage in the flower strips could again serve as an explanation for this observation. For instance, in a long-term field trial, Kuntz et al.56 found five times more earthworm cocoons as well as 1.8 times more endogeic juveniles under plots with reduced tillage as compared to conventionally tilled plots. Overall, our findings suggest that i) perennial flower strips promote the total earthworm community, ii) can induce the establishment of populations of anecic and epigeic earthworms, and iii) can serve as a habitat for the reproduction of endogeic earthworms.

Earthworms contribute to the provision of numerous ecosystem services57 and can increase crop yields58, raising the question if the high population densities under perennial flower strips benefit neighboring crops through spillover effects. Research on croplands with permanent field margins demonstrated that although field margins harbor large earthworm population densities, spillover effects into neighboring crops may be limited or absent (cf.27,59,28). Yet, studies investigating distance-effects of earthworms as well as their functions for crop production at the interface of croplands and perennial flower strips are missing. Crop yields, however, are influenced by a multitude of management (e.g. soil management, plant protection products) and environmental factors (e.g. weather conditions) as well as their interactions as recently discussed for crop yields in response to flower strips by Albrecht et al.10. The factors above may mask beneficial effects of flower strips on crop yields delivered by earthworms, which is in line with the data synthesis by Albrecht et al.10 who found on average no effect of flower strips on crop yields. Even if spillover effects of earthworms were identified, we expected them to have rather limited impact at field scale, as the vast majority of perennial flower strips are currently sown at the edges of fields. However, we propose that innovative spatial designs that integrate perennial flower strips into agricultural fields –such as strip cropping with flower strips as shown in Supplementary Fig. S7 – have the potential to enhance ecosystem services provided by flower strips at field scale. Furthermore, through spatial diversification beyond field edges, strip cropping systems that integrate perennial flower strips may facilitate earthworm recolonization of depleted croplands following disturbance events (e.g., droughts and soil mismanagement).

We further expect that the temporal continuity of the perennial flower strips is an important factor for soil communities. In the European Union, the life span of perennial flower strips is usually limited to five years as they lose their status as arable land after more than five years of not being part of the crop rotation. Additionally, farmers are only compensated for the implementation and maintenance of the perennial flower strips as well as yield losses for five years. Consequently, perennial flower strips are usually tilled after five years and brought back into cultivation. Given their importance as a food resource for numerous vertebrates (e.g., amphibians, birds, reptiles, and small mammals)60, large earthworm populations in perennial flower strips are expected to benefit higher trophic taxa. Since earthworms are relatively immobile and highly sensitive towards tillage, we expect that the conversion of perennial flower strips to cropland at the end of five-year funding schemes will result in a rapid decline in earthworms and consequently available food resources for higher trophic taxa in agroecosystems. Therefore, we agree with Haaland & Bersier61 that perennial flower strips in agroecosystems should be established and removed rotational or staggered in order to support large earthworm population densities across time and space.

A healthy soil microbiome can provide numerous functions that are crucial for agricultural production such as nutrient mobilization62 and suppression of soil-borne plant pathogens63. In the context of agroecology, beneficial microorganisms are of great importance as they can compensate for the reduction of external inputs, which is a key principle of sustainable agriculture. The utilization of the full potential of the soil microbiome requires the identification and application of agricultural practices that promote beneficial microorganisms (e.g. plant growth-promoting bacteria) and shift the microbial community towards increased functionality. Among agricultural practices, those that result in increased plant species richness are expected to increase soil multifunctionality through the promotion of microbial communities64,65,66.

Although flower strips are a common agricultural diversification measure, their impact on soil microbial communities and their functions still remains largely unexplored. As of writing and to our best knowledge, the works by Bednar et al.17 and Bullock et al.67 are the only studies investigating soil microorganisms in flower strips. Bednar and colleagues17 used real-time PCR to quantify soil microorganisms and were able to show that two years post establishment, perennial flower strips harbor the same population size as annual flower strips and field margins but did not consider cropland. In contrast, Bullock et al.67 analyzed phospholipid fatty acids and reported greater total microbial as well as fungal biomass in wildflower margins versus croplands. In the present study, the population size of soil bacteria and N2O reducers remained unaffected, whereas a slightly greater fungal population size was observed in the croplands as compared to the perennial flower strips (Fig. 4B, C), partly confirming our third hypothesis. Although we did not perform microbiome analysis, results from other linear perennial landscape elements suggest that soil microbial communities are highly distinct between perennial flower strips and croplands. For instance, a study that compared woody and herbaceous field margins to soy fields reported functionally distinct communities and decreasing functional diversity from woody to herbaceous field margins to soy fields15. Likewise, Holden et al.29 found distinct fungal communities in croplands, hedgerows, and grassy field margins. Furthermore, richness of arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi was lower in croplands than in hedgerows and grassy field margins29. Similarly, Bednar et al.17 found that grassy field margins, annual flower strips, and perennial flower strips harbor compositionally distinct soil bacterial and fungal communities. The authors further demonstrated a strong community shift towards higher relative abundance of AM fungi within the fungal community in non-tilled grassy field margins and perennial flower strips as compared to annually re-established flower strips17. In a recent study, colonization rates of winter wheat roots with AM fungi showed a decline with distance to semi-natural habitats68, demonstrating beneficial belowground effects beyond the borders of the semi-natural habitats. Whether perennial flower strips benefit neighboring crops through spillover of beneficial microorganisms remains yet to be investigated.

Conclusion

Perennial flower strips harbored greater earthworm population densities than croplands (on average +301% for anecic, +208% for endogeic, and +2263% for epigeic species) and in some cases provided habitat allowing for the establishment of anecic and epigeic communities that were otherwise absent in croplands. Our results further suggest that perennial flower strips provide habitat for the reproduction of endogeic earthworms. Since earthworms contribute to the provision of essential ecosystem functions, we believe their promotion through the establishment of perennial flower strips translates into improved soil functions in agroecosystems. Furthermore, we expect that the increase in earthworm density and biomass through perennial flower strips benefits higher trophic taxa in agroecosystems such as amphibians, birds, reptiles, and small mammals. In contrast to earthworms, the population size of soil bacteria and fungi remained mostly unaffected by the establishment of perennial flower strips. We suggest that future studies should investigate to which extent spillover effects of soil communities from perennial flower strips into the neighboring crops occur and if crops can benefits from such. Finally, we propose that optimized seed mixtures, improved spatial configuration (e.g., strip cropping), and the establishment of temporal continuity (e.g., rotational or staggered establishment and removal) of perennial flower strips can further promote soil functional biodiversity and its benefits for agroecosystems.

Methods

Study sites and study design

We selected 46 study sites with paired croplands and perennial flower strips in six federal states across Germany (Baden-Württemberg, Brandenburg, North Rhine-Westphalia, Rhineland-Palatinate, Saxony-Anhalt, Schleswig-Holstein) (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Table S1). The flower strips were established by converting cropland with annual crops to perennial flower strips. Samples were collected in spring 2023 from March 27 to May 9. Sampling was conducted in the perennial flower strips as well as at ≥30 meters distance from the flower strips within the croplands (Fig. 1B). In each perennial flower strip and cropland, we established four sampling locations (4 sampling locations × 2 management systems (i.e., perennial flower strip or cropland) × 46 sites = 368 sampling locations).

The perennial flower strips aged one to six and a half years during sampling and were established from different seed mixtures that were adapted to the regional conditions. Detailed information regarding the age of the flower strips can be found in Supplementary Table S1. The flower strips received no fertilization and plant protection products and were not tilled since their establishment. All adjacent croplands were cultivated with cover crops or winter crops (barley, oilseed-rape, rye, spelt, triticale, wheat) at the time of sampling. Information regarding the study sites can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

Earthworm extraction and species determination

At each sampling location, earthworm communities were extracted using chemical expulsion as described previously55. Briefly, 5 liter of a 0.01% (v/v) allyl isothiocyanate (AITC) solution were poured into a 50 × 50 cm metal frame that was embedded approx. 5 cm deep into the soil. Surfacing earthworms were collected for 30 min and immediately rinsed with tap water and stored at 5 °C in tap water until species and weight determination. Within 24 h post extraction, morphological identification to species level was performed according to Krück69 together with the determination of developmental stage (i.e., juvenile or adult) and biomass (fresh weight with gut content) of all individuals55. Individuals that were successfully determined based on morphology were released alive. Juvenile or damaged individuals that could not be determined morphologically were preserved in 60% (w/v) propylene glycol pre-cooled to −20 °C and stored at −20 °C for molecular analysis. Prior to the extraction of DNA, juvenile individuals were freeze-dried for 24 h. DNA of freeze-dried individuals was extracted using a cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)-based extraction protocol as described previously70. The quantity and quality of the extracted DNA was examined on 1% (w/v) agarose gels stained with SYBR Green I. Finally, individuals were determined by Sanger sequencing targeting the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (COI) gene using the primer pair LCO 1490/HCO 219871 or Sauron-S878/jgHCO219872,73. The composition of the PCR reaction mixtures and thermocycling conditions were identical to those used for Sanger Sequencing by Vaupel et al. 74.

Soil sampling

In order to account for spatial heterogeneity in the field, three soil subsamples at 0–30 cm soil depth were collected at each of the 368 sampling locations (Fig. 1C) using an auger (Ø 3.5 cm). At each sampling location, the three subsamples were pooled and thoroughly homogenized in a sterile polyethylene bag in the field. By this, we obtained one composite soil sample per sampling location for the subsequent analysis of soil microbial communities and general soil characteristics. For the determination of soil bulk density and gravimetric soil water content, an additional 250-cm3 soil sample of the upper 5-cm topsoil was collected at each sampling location using the soil core method75 (Fig. 1C).

Soil DNA extraction

In the field, an aliquot of approx. 50 g fresh soil from each composite soil sample (0–30 cm soil depth) per sampling location (see Soil sampling; Fig. 1C) was frozen in sterile 50-ml polypropylene tubes at −20 °C. Upon return to the laboratory, soil samples were stored at −20 °C until freeze-drying for 72 h. Freeze-dried soil samples were finely ground using a vortexer as described previously76. Soil DNA was extracted from finely ground soil following a CTAB-based extraction protocol76. Briefly, 50 mg soil were suspended in 1 mL CTAB buffer containing 2 µl Mercaptoethanol and 1 µl Pronase E (30 mg/ml). The suspension was incubated at 42 °C for 10 min followed by 65 °C for 10 min and 800 µL phenol were added. The mixture was shaken and centrifuged at 4600 × g for 10 min. The supernatant (800 µL) was transferred to a new 2-mL tube, 800 µL chloroform/isoamylalcohol (24:1 (v/v)) were added and the mixture was incubated on ice for 10 min and subsequently centrifuged at 4600 × g for 10 min. Following centrifugation, 700 µL of the supernatant was transferred to a new 2-mL tube and 700 µL chloroform/isoamylalcohol (24:1 (v/v)) were added. The mixture was incubated on ice for 10 min, centrifuged at 4600 × g for 10 min and 600 µL of the supernatant were transferred to a new 1.5 mL tube for DNA precipitation. After adding 200 µl PEG 6000 (30% (w/v)) and 100 µl 5 M NaCl, precipitation was allowed for 20 min. Following incubation, precipitated DNA was pelleted by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 15 min and washed with 500 µl 70% (v/v) EtOH twice to remove salts. Washed pellets were dried using vacuum centrifugation, resuspended in 50 µL 1× Tris-EDTA buffer and incubated at 42 °C for 2 h to facilitate resuspension. The quantity and quality of the extracted DNA was examined on 1% (w/v) agarose gels stained with SYBR Green I.

Real-time PCR assays for soil microbial groups

Soil bacteria, fungi, and functional genes involved in N2O reduction (nosZ clade I and II genes) were quantified using real-time PCR as per77. Prior to PCR, DNA extracts were tested for PCR inhibitors78 and diluted 1:50 (w/v) in double-distilled H2O (ddH2O). DNA amplification was performed in 5 µL reaction volumes in a qTOWER3 84 G (Analytik Jena GmbH+Co. KG, Jena, Germany) real-time PCR thermocycler. The reaction volume contained 4 µL of master mix and 1 µL of template DNA or ddH2O for negative controls. The composition of the master mix (including the choice of primers79,80,81,82,83) and the thermocycling conditions are given in Supplementary Table S2 (Additional File 2). Following amplification, melting curves were generated by step-wise increasing the temperature from 65 °C to 95° at a rate of 1 °C per step under continuous fluorescence measurement.

Determination of general soil characteristics and soil moisture

Soil pH, SOC, total N, and soil texture were determined from air-dried and sieved (<2 mm) aliquots of the composite soil sample (0–30 cm soil depth) per sampling location (see Soil sampling; Fig. 1C). Soil pH was determined in 0.01 M CaCl2 at a ratio of 1:2.5 (soil:0.01 M CaCl2). Prior to the determination of SOC, carbonates were removed using acid fumigation as described by Harris et al.84. Concentrations of SOC and total N were determined on a CNS elemental analyzer (Vario EL Cube, Elementar, Germany). Since the hydrometric determination of soil texture is laborious and not environmentally friendly85, all eight composite samples per study site (four sampling locations in the cropland and four in the flower strip) were pooled prior to texture analysis as per86. By this, the number of samples for soil texture analysis was reduced from 368 to 46 (i.e., one composite sample per study site). Soil bulk density at 0–5 cm soil depth was determined from 250-cm3 soil samples dried at 105 °C using the soil core method75 assuming a particle density of 2.65 g cm−3. Gravimetric soil water content was determined from the same samples.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in R version87. For earthworm population density data, differences between flower strips and croplands were tested with generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) using the ‘glmmTMB’ package (version 1.1.7). Differences in soil characteristics, earthworm biomass, and soil microbial groups were tested using linear mixed-effect models (LME) utilizing the ‘lme4’ package (version 1.1-33). In all models, management system (i.e., cropland or perennial flower strip) was set as a fixed effect while study site nested in the operating farmer was set as random effect. All models were manually inspected for overdispersion and all data were tested for normal distribution of the residues (Shapiro–Wilk’s test, QQ Plot) and homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test) using the packages ‘performance’ (version 0.10.4) and ‘DHARMa’ (version 0.4.6). Data that did not meet the criteria above were either log- (SOC, total N, soil microbial groups, fungi-to-bacteria ratio, and juvenile-to-adult earthworm ratio) or square root-transformed (earthworm biomass, gravimetric soil water content). Relations between parameters were analyzed with Spearman’s rank correlation test using the ‘stats’ package (version 4.3.0). For all statistical tests, statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05.

Responses