Perimenopause symptoms, severity, and healthcare seeking in women in the US

Introduction

Perimenopause is the time leading up to and around menopause and is associated with a wide variety of physical and psychological symptoms. Many women feel unprepared for this phase, as well as menopause itself, and feel that they are not adequately supported by healthcare systems or workplaces during this time1,2,3. Furthermore, there is a distinct lack of research on perimenopause and the experiences of women during this transition to menopause3. Consequently, there is an urgent need for robust research to better understand the symptoms and experiences of women during perimenopause and to improve support for them before and during this period. The terminology around menopause and perimenopause can be confusing. Colloquially, “menopause” is often used to describe both the period of time leading up to the final menstrual period (FMP) and after. This does not align with widely agreed medical definitions. According to the STRAW + 10 criteria4, menopause, the time of the FMP, marks the end of the monthly menstrual cycles. Perimenopause is the transition through menopause. It covers the years leading up to the FMP and the 12 months after the FMP. Post-menopause is the time after the FMP, and, therefore, may overlap with the final 12 months of perimenopause.

Perimenopause is variable in its onset, overall length, severity of symptoms, and impact on functioning5, but is generally understood to last between 5–10 years. Perimenopause can be broadly split into early and late stages5, where the early stage is defined by occasional missed cycles or cycle irregularity, while the later stage is characterized by greater menstrual irregularity, with longer periods of amenorrhea, ranging from 60 days to one year. As stated above, 12 or more months of amenorrhea defines the FMP and, subsequently, menopause. While the primary symptoms of the early stage of perimenopause are related to cycle irregularity, the later stage is associated with a greater number of physiological changes as a result of the decline in ovarian function that occurs6.

As many as 90% of women may seek medical care for symptoms in perimenopause7, meaning an understanding of these symptoms is important for providing care and education. The symptoms associated with perimenopause fall into many domains8. Vasomotor symptoms, including hot flashes or night sweats, are classic symptoms associated with perimenopause9,10. Other physical symptoms can include genitourinary problems such as urinary incontinence or vaginal dryness and reduced libido11. Sleep12,13 changes are common, with increased reports of insomnia and sleep difficulty, which are often associated with vasomotor symptoms5. There are also changes in mood and mental health with an increased risk of depression and anxiety in perimenopause, with perimenopausal people being 2–4 times more likely to experience an episode of major depressive disorder14. Cognitive complaints, such as confusion, brain fog, or decreased concentration, are also commonly reported15,16,17. However, this list of symptoms is not exhaustive, with a wide variety of symptoms and severity of symptoms reported worldwide.

Rating scales exist to measure the severity of symptoms of perimenopause, such as the Menopause Rating Scale18 (MRS). The MRS is well-validated and widely used in international populations. However, it is unclear how well the MRS performs at ages younger than 40 years, and how well the MRS correlates with perimenopause or menopause status. Additionally, even though perimenopause symptoms can occur in women younger than 40 years, there are few studies in samples that include women below this age.

In this study, we aimed to describe perimenopause symptom severity and rates of confirmed perimenopause as determined by a medical professional in a sample of women aged 30 years and older. We also investigated the relationship between MRS score or severity categories and the presence or absence of perimenopause as confirmed by a healthcare provider.

Results

A total of 5136 individuals accessed the survey. Out of these, 4624 consented to participate, and 4432 participants completed all survey sections and were included in the final analysis. A breakdown of perimenopause status, and the presence of a 12-month absence of periods is provided in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 42.6 years (standard deviation (SD) = 9.4 years), with the majority of respondents reporting being White, European American, or Caucasian (60.3%).

Analysis 1—perimenopause status by age group

A total of 908 (20.7%) respondents had consulted a medical professional about perimenopause or menopause. Among the respondents who had seen a medical professional, 275 (30.3%) were aged under 46 years. The rates of seeing a medical professional about menopause or perimenopause differed by age group (χ2 = 803.98, p < 0.001), with the respondents in the 56+ years age group having the highest rate of consultations (51.5%) (Table 1). Of the respondents who consulted a medical professional about menopause, 612 (70.8%) were told they were in perimenopause at the time of consultation. Overall, perimenopause status differed by age group (χ2 = 227.79, p < 0.001), with the highest rate of confirmed perimenopause received in the 51–55 year-olds (42.6%), Table 1.

Analysis 2—perimenopause symptoms by perimenopause status

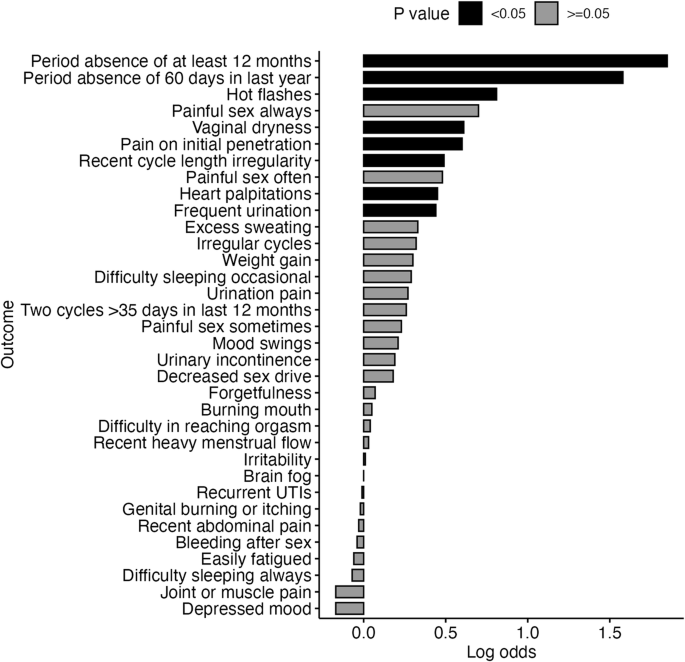

Certain symptoms were more likely to be reported by participants with confirmed perimenopause as determined by a medical professional compared to those without. The unadjusted log odds ratios and corresponding confidence intervals (CI) and p values for these symptoms were as follows: absence of a period of at least 12 months (log odds = 1.85; 95% CI = 1.38–2.38; p < 0.001), a period absence of 60 days in the last year (log odds = 1.58; 95% CI = 1.19–1.98; p < 0.001), hot flashes (log odds = 0.81; 95% CI = 0.45–1.17; p < 0.001), vaginal dryness (log odds = 0.61; 95% CI = 0.25–0.97; p = <0.001), pain on initial penetration during sexual activity (log odds = 0.60; 95% CI = 0.23–0.98; p < 0.001), recent cycle length irregularity (log odds = 0.49; 95% CI = 0.11–0.87; p = 0.012), heart palpitations (log odds = 0.45; 95% CI = 0.06–0.85; p = 0.028), and frequent urination (log odds = 0.44; 95% CI = 0.08–0.82; p = 0.019). Other symptoms did not differ between the two groups, as can be seen in Fig. 1.

Unadjusted log odds for symptoms in the respondents with confirmed perimenopause compared to respondents who saw a doctor but were not perimenopausal. (UTI: Urinary tract infection).

Analysis 3—MRS score by age group

We used the MRS to measure symptom burden in respondents. The median total score (H = 91.50, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.02), and the medians of the three domain scores of urogenital symptoms (H = 177.17, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.04), psychological symptoms (H = 55.70, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.01), and somato-vegetative symptoms (H = 209.07, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.05) differed by age group. The MRS total score and the somato-vegetative domain score were highest in the 51–55 years age group, while the psychological domain score was highest in the 41–45 years age group and the urogenital domain score was highest in the 51–55 years and 56+ years age groups (Table 2).

The MRS score has cutoffs to indicate categorical levels of severity of menopause-related symptoms. The proportion of respondents falling into the different severity categories differed by age, with the highest percentage (39.0%) of individuals falling into the severe category being 51–55 years old. Notably, in this survey, high rates of moderate or severe symptoms are seen even in the youngest age groups, with 55.4% of 30–35 year-olds falling into the moderate or severe categories (Table 2).

Analysis 4—MRS scores and severity by perimenopause status

Kruskal Wallis Tests indicated that MRS total (H = 190.46, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.04), urogenital (H = 251.82, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.06), psychological (H = 45.37, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.01) and somato-vegetative domain scores (H = 254.98, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.06) differed by perimenopause status. Median MRS total score and psychological domain scores were highest in the “premature menopause” group. Median urogenital scores were highest in the “I was diagnosed with something else”, “perimenopausal” and “post-menopausal” groups. The median somato-vegetative domain score was highest in the perimenopausal and premature menopause groups (Table 3).

Post-hoc Dunn tests (Supplementary Table 2) indicated that the “Did not see a clinician” group had a lower MRS total score than the “not perimenopausal”, “perimenopausal”, and “premature menopause” groups.

The “did not see a clinician group” also had a lower urogenital domain score than the “not perimenopausal”, “I was diagnosed with something else,” “perimenopausal”, “post-menopausal”, and “premature menopause” groups. In addition, the non-perimenopausal group had a lower urogenital domain score than the perimenopausal group.

For the psychological domain score, the “did not see a clinician” group had a lower score than the “not perimenopausal”, “perimenopausal” and “premature menopause” groups.

Finally, for the somato-vegetative domain score, the “did not see a clinician” group had a lower somato-vegetative symptom score than all other groups, and the “not perimenopausal” group had a lower score than the “perimenopausal” group.

When considering the categorical symptom severity thresholds, we found an overall difference in MRS symptom severity across perimenopause status groups (Table 3). A chi-squared test between the not perimenopausal and perimenopausal groups revealed no difference in the proportion of individuals in each of the MRS severity categories between the two groups (χ2 = 0.075, p = 0.784). However, there was a higher proportion of individuals in the severe and moderate categories in the perimenopausal group compared to the “did not see a clinician” group (χ2 = 149.41, p < 0.001).

Analysis 5—MRS scores and severity by cycle symptom categories

Cycle irregularity and amenorrhea are key indicators of perimenopause. A “persistent” variation of 7 or more days in consecutive cycle lengths is indicative of early perimenopause, while amenorrhea of at least 60 days in the last year is indicative of late perimenopause. The absence of a period for at least 12 months indicates that a person is post-menopausal. When using these criteria to categorize respondents, we observed differences in MRS scores between these groups (Table 4). Kruskal Wallace tests revealed that the MRS total score (H = 118.85, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.03) and all domain scores (Urogenital: H = 193.65, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.04; Psychological: H = 45.37, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.004, Somato-vegetative: H = 183.91, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.04) differed between individuals with no-cycle symptoms, irregular cycles, a 60-day absence or a 12-month absence (Table 4).

Total MRS scores were highest in the 12-month absence, 60-day absence, and irregular cycles groups with post-hoc Dunn tests showing that the irregular cycles (Z = 6.35, adj.p < 0.001), 60-day absence (Z = 6.39, adj.p < 0.001), or 12-month absence (Z = 8.69, adj.p < 0.001) group scores differed from the no-cycle symptoms group.

Median urogenital scores were highest in the 60-day absence and 12-month absence groups, with the 12-month absence group differing from the 60-day absence (Z = 6.71, adj.p < 0.001), irregular cycles (Z = 4.01, adj.p < 0.001) and no-cycle symptoms group (Z = 13.04, adj.p < 0.001), while the 60-day absence (Z = 6.71, adj.p < 0.001) and irregular cycles (Z = 4.81, adj.p < 0.001) groups differed from the no-cycle symptoms group.

The median psychological score was highest in the irregular cycles and 60-day absence group, with the irregular cycles group differing from the no-cycle symptoms group (Z = 4.15, adj.p < 0.001), and the 12-month absence group (Z = 3.04, adj.p = 0.012).

Finally, somato-vegetative scores were highest in the irregular cycles, 60-day absence, and 12-month absence groups, with the no-cycle symptoms group having lower somato-vegetative scores than the 12-month absence (Z = 11.15, adj.p < 0.001), 60-day absence (Z = 8.08, adj.p < 0.001), and irregular cycles groups (Z = 7.17, adj.p < 0.001).

The percentages of individuals falling into MRS symptom severity categories differed by cycle irregularity (χ2 = 114.91, p < 0.001), with more individuals reaching criteria for moderate or severe symptoms in the irregular cycles (76.5%; χ2 = 40.23, p < 0.001), 60-day absence (73.7%; χ2 = 70.94, p < 0.001), or 12-month absence (χ2 = 12.11, p = 0.007) groups than in the no-cycle symptoms group (60.9%) (Table 4).

Discussion

In this large sample of US-based women aged over 30 years, we explored rates of clinical help-seeking for perimenopause, investigated which symptoms were most associated with perimenopause status, and estimated symptom severity of perimenopause and menopause-related symptoms using the MRS.

Overall, we found that the rate of visits to a medical professional about perimenopause increases with age, along with a higher rate of perimenopause and menopause diagnoses. However, we also demonstrated that over a quarter of respondents in the youngest age group (30–35 years) had been told by a medical professional they were perimenopausal. A total of eight symptoms were found to be associated with a perimenopause status, including a period absence of 12 months or 60 days, hot flashes, pain on initial penetration during intercourse, vaginal dryness, frequent urination, irregular cycles, and heart palpitations. In line with increasing rates of help-seeking with age, we also find that total MRS scores tended to be higher in older age groups, peaking in the 51–55 years age group. However, we found little evidence that the MRS scores were associated with medically confirmed perimenopause, as only scores in the urogenital and somato-vegetative domains differed between the perimenopause and not perimenopausal groups. This may suggest that the MRS score alone is not a good marker of perimenopause status. We did find differences in MRS score by cycle symptoms indicative of perimenopause or post-menopause status.

Unsurprisingly, we found that rates of consulting a clinician or doctor about perimenopause or menopause increased with age. Rates of consultations increased from 4.3% in the 30–35 year-olds to 51.5% in the 56+ years age group. Overall, 30.2% of the respondents who had consulted a doctor about perimenopause were aged 30–45 years, and while rates of medically confirmed perimenopause were highest in the 51–55 years age group, over a quarter of 30–35 year-olds and 40% of 36–40 year-olds had been told they were perimenopausal. This suggests that there is a significant proportion of women who are concerned about perimenopause or may even reach the criteria for perimenopause despite being younger than the average age of onset of perimenopause of 47.5 years19,20,21. Previous literature shows that perimenopause is variable for individuals5,22,23, with a wide range of durations and symptom severities. It may be the case that the first symptoms of perimenopause are present long before this estimated average onset. These findings highlight the need for holistic perimenopause care and education, even at ages generally thought to be part of the reproductive phase, as the onset and presentation of perimenopause can vary so greatly.

A logistic regression analysis revealed that only certain symptoms were associated with perimenopause status, namely a period absence of 12 months or 60 days, hot flashes, pain on initial sexual penetration, vaginal dryness, frequent urination, irregular cycles, and heart palpitations. It may be that these symptoms represent some of the most troubling symptoms for individuals, as these symptoms were associated with perimenopause status in those individuals who went to a doctor about perimenopause symptoms. It is unsurprising that cycle absences and irregularity feature in the list of symptoms associated with perimenopause status, as these are part of the definition of perimenopause and, eventually, menopause4. However, due to limitations in the survey methodology, we cannot be sure when an individual spoke to a clinician in relation to when they completed the survey. It is, therefore, possible that the symptoms that were present when the individual visited a doctor were different from those that the respondent reported during the survey. The symptoms highlighted here as being associated with a perimenopause status correlate with lists of symptoms commonly reported in perimenopause5,24. Cycle irregularity and absence of a period are part of the definitions of early and late perimenopause, vasomotor symptoms such as hot flashes and heart palpitations are common, and vaginal dryness and bladder or urinary symptoms are often of concern to women when experiencing perimenopause. However, mood symptoms are also often reported in perimenopause25,26,27, but do not feature in those symptoms that are associated with a perimenopause status in this analysis. This could be for several reasons. Patients may not be aware that these mood and cognitive changes can occur due to perimenopause, such as forgetfulness or brain fog. Clinicians may put less weight on complaints of this type, and there is a lack of standardized mood assessments during perimenopause28. Or the preexisting presence of mental health conditions such as depression or anxiety may provide better explanations for the symptoms than perimenopause. Finally, survey respondents may have been reluctant to discuss mood symptoms with their clinician. Clinicians should ensure to take any changes in mood or psychological symptoms into account when assessing individuals for perimenopause.

In addition to asking about the presence of specific symptoms associated with perimenopause, we also used the MRS to measure the severity of menopause-related symptoms. Overall, we found that the impact of perimenopause symptoms peaks in the 51–55 year-olds. This supports the idea that symptoms may be worse in late perimenopause and that some symptoms may improve post-menopause. We also found that over half of the individuals in the youngest age group (30–35 years) were classified as having moderate or severe symptoms using the MRS. This highlights the need for greater awareness of the changes that can occur in perimenopause-related symptoms, even at relatively young ages. While some of the symptoms asked about in the MRS, such as mood and cognitive changes, may have alternative explanations, such as an established diagnosis of a mental health condition, it may also be the case that some individuals aged 30–40 years are experiencing symptoms as a result of premature menopause, iatrogenic menopause, or misunderstanding the questionnaire. Nevertheless, the high endorsement of the impact of perimenopause-related symptoms in this age group warrants further research.

While we see clear trends of an increase in perimenopause symptoms with age, the picture for MRS scores between perimenopause status groups is more complicated. Overall, we observed differences in MRS scores between individuals with different outcomes when they visited a doctor about perimenopause. However, when we compared individuals with perimenopause status to individuals who saw a doctor about perimenopause but were told they were not perimenopausal, we found that they only differed in urogenital and somato-vegetative domain scores and not in the overall MRS score. This aligns with our findings of vasomotor and urogenital symptoms being associated with perimenopause status and, again, may highlight that these symptoms are the most troublesome for individuals experiencing perimenopause. The lack of difference in MRS total score between individuals with a perimenopause status and those without, along with the lack of differences in the severity categories between these groups, might suggest that the MRS total score alone is not a good indicator of perimenopause status. This could be for a number of reasons. As perimenopause is a natural life stage, a clinician may indicate everything is fine for the individual’s age and that symptoms are expected, which might be interpreted by a patient as perimenopause symptoms not being a problem. The MRS scale also does not consider cycle irregularity or absence, which are traditionally used as key markers for perimenopause staging. However, the lack of association between MRS symptom scores and perimenopause status should not take away from the potential disruption that physical, cognitive, and mood symptoms experienced during perimenopause can cause.

Notably, the MRS does not ask about cycle symptoms. Cycle irregularity and cycle absence are part of the definitions used by the STRAW + 10 criteria for early and late perimenopause. Using the STRAW + 10 criteria, where persistent cycle irregularity of ≥7 days is indicative of early perimenopause, an absence of a period for at least 60 days in the last year is indicative of late perimenopause, and an absence of a period for 12 months is the criterion for being post-menopausal, we assessed how MRS scores changed over these phases. Overall, we found that MRS total and subscale scores were higher in those individuals who were in early or late perimenopause or post-menopausal than those with no-cycle symptoms. In terms of the individual domains, urogenital and somato-vegetative domain scores were higher in post-menopausal individuals as compared with both early and late perimenopausal individuals, while psychological domain scores were higher in individuals in early perimenopause as compared with post-menopausal individuals. This may indicate that the profile of symptoms seen over perimenopause may change over time. For example, mood symptoms may be worse early in perimenopause, while urogenital symptoms may get progressively more impactful as an individual approaches their FMP. Further research into the temporal profile of symptoms associated with perimenopause will help individuals be informed about what to expect during this critical time period.

To our knowledge, this is one of the largest studies to report on rates of help-seeking for perimenopause symptoms, the associations between individual perimenopause symptoms and perimenopause status, and the patterns of symptom severity by age, perimenopause status, and by cycle symptom staging. A strength of the study is the use of the MRS, a validated tool to measure perimenopausal symptom severity. In addition, the study included information from a wide range of individuals, including respondents as young as 30 years, to ensure that early-onset perimenopause symptoms were captured.

Limitations of the study include the reliance on self-reported symptoms and perimenopause status, which may not be accurate. Additionally, the survey did not ask about the timeframe of reported symptoms, and therefore, we cannot be sure that the symptoms reported by survey respondents at the time of the survey were present when they spoke to a doctor about their concerns about perimenopause. There may also be ambiguity in what individual respondents understand about terms such as menopause, perimenopause, and post-menopausal. Colloquially, menopause is often used to describe the entire period defined as perimenopause by the STRAW + 10 criteria. In addition, perimenopause is not really a “diagnosis” as it is a natural life stage. Therefore, it may be that individuals were not told they were perimenopausal, that what they were experiencing was normal, and that there was no need for concern unless specific symptoms were impacting daily life. This limits our ability to compare differences in symptoms and symptom severity between individuals who were told they were perimenopausal and those who were told they were not perimenopausal. For the analyses investigating associations between medically confirmed perimenopause status and symptoms, individuals who had not consulted a medical professional were not included, as we had no information about their perimenopause status. This may mean we are only considering individuals with relatively severe symptoms, as individuals with mild symptoms may not visit a clinician. However, other reasons for not consulting a clinician would include a lack of access and a lack of understanding about what is normal or abnormal in perimenopause and what treatments are available. Future research should attempt to obtain other information about perimenopause status, in addition to diagnosis information from clinicians, in order to better capture these groups. There are also limitations in the sample used. We only surveyed women in the US, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other populations. There are known ethnic and geographical differences in perimenopause symptoms and the onset of symptoms29,30, meaning that further research in other samples is needed. In addition, due to recruitment taking place remotely and online, either through the Prolific website or in the Flo app, older individuals may have been less likely to be recruited to the study. Further work should ensure equitable recruitment across age groups.

Here, we present the findings of one of the largest studies to date of perimenopause help-seeking, medical confirmation of perimenopause, symptoms, and symptom severity. Rates of seeking help for perimenopause increase with age, but symptom burden remains high, even in individuals aged 30–45 years. Further research is needed to understand the temporal patterns of perimenopause symptoms across age groups and to understand whether our findings of significant symptoms in individuals younger than 45 years and psychological symptoms being more common in early perimenopause can be replicated.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Study participants were recruited either through the online recruitment platform Prolific or were users of the Flo app. To be eligible, participants were required to be at least 30 years of age. Participants responded to a questionnaire via SurveyMonkey, provided by a weblink between November 2023 and March 2024. Study participants provided informed electronic consent before completing screening questions and the survey. The survey was only advertised to individuals who indicated that they were female, aged over 30 years, and located in the US on either the Prolific platform or in the Flo app. Users from the US were recruited as they represent the app’s primary English-speaking userbase.

Those who consented and met the inclusion criteria (female, aged over 30 years, located in the US) could complete the survey electronically. This study was approved by the Independent Ethical Review Board: WIRB-Copernicus Group Institutional Review Board (IRB number 20231821). The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study protocol was approved by an independent ethics review board (Western Copernicus Group Independent Review Board—WCG IRB, number 20231821).

Materials

Participants self-reported age and ethnicity. Participants were also asked about common perimenopause symptoms through a set of questions designed with input from Flo Health’s medical advisors and, in addition, completed the MRS. The MRS18 consists of 11 questions, which are rated for symptom severity by the respondent between 0 (no, little) to 4 (severe). The questions are divided into 3 domains: psychological, somatic-vegetative (including hot flashes, excess sweating, sleep problems, heart problems, and muscle and joint problems), and urogenital symptoms, with scores for each domain obtained by adding the scores for each of the questions in a domain. A total composite score is obtained by adding the domain scores together. Higher domain or composite scores indicate a greater severity of symptoms. Total Composite Score cutoffs can be used to assign respondents to symptom severity categories. These categories are no or little severity (0–4 points), mild (5–8), moderate (9–16), and severe (17+). Domain-specific cutoffs can also be applied. For the psychological domain, the cutoffs are no or little severity (0–1 points), mild (2–3), moderate (4–6), and severe (7+). For the tomato-vegetative domain, they are no or little severity (0–2 points), mild (3–4), moderate (5–8), and severe (9+). Finally, for the urogenital domain, the cutoffs are no or little severity (0 points), mild (1), moderate (2–3), and severe (4+). The symptom questionnaire can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis included descriptive statistics of ethnicity, rates of visiting a doctor and perimenopause status, and period absences of at least 12 months. Chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables between groups. The association between different symptoms reported and perimenopause status (Analysis 2) was tested with logistic regression, where the perimenopause status was predicted only by the presence or absence of the symptom of interest. Only individuals who had seen a doctor and either been told they were perimenopausal or were not perimenopausal were included in the logistic regression analyses. Confirmed perimenopause, as determined by a medical professional group, refers to those individuals who were told they were in perimenopause by a medical professional. Group differences in MRS scores were analyzed using Kruskal Wallis tests, with post-hoc Dunn tests to investigate pairwise differences between individual group levels.

Statistical analysis was conducted using R version 4.4.031, on OS X 14.4.1.

Responses