Peripheral nerve-derived CSF1 induces BMP2 expression in macrophages to promote nerve regeneration and wound healing

Introduction

The skin is the largest organ of the human body. It acts as the first barrier against the external environment and is the most frequently injured organ. Skin wound healing is a highly coordinated process in which different cell types are dynamically and orderly repair damaged tissue; this process involves the production of multiple growth factors and cytokines. In most cases, acute skin injury triggers an urgent response, creating an enclosed environment that stops blood loss and infection and promotes tissue repair over time1,2. However, chronic nonhealing wounds can cause chronic inflammation, hypoxia, vascular damage, infection, and peripheral neuropathies3. The lack of understanding of the roles of the different cell types involved and the interactions between cells has hindered the development of effective treatments for wound healing. Previous studies have reported that the mechanisms of wound repair involve many key processes, including increased angiogenesis, the proliferation of fibroblasts and keratinocytes, inflammation, and nerve regeneration4.

The inflammatory response plays a key role in wound healing. Skin injury triggers a series of dynamic and orderly inflammatory cell repair programs, including a pro-inflammatory program that plays an antibacterial role in the early stage of the repair, and a pro-resolution program that plays a role in tissue growth and differentiation in the late stage of the repair5. Macrophages are an important component of the body’s ability to restore tissue function after injury6. Previous studies have demonstrated that macrophages are activated by specific cell types in the microenvironment following tissue injury. In brief, after monocytes in the blood are recruited to sites of tissue damage, they differentiate into proinflammatory M1 type macrophages to support microbial resistance, inflammation, and tissue growth in the early phase7. Subsequently, these macrophages are transformed into pro-repair M2 type macrophages to enhance tissue regeneration and skin reconstruction5,8. However, the processes that regulate the coordinated transition from proinflammatory macrophages that combat foreign material to prorepair macrophages that rebuild tissue structure and restore homeostasis remain unresolved.

A growing body of research suggests that the peripheral nervous system (PNS) is extremely critical for a variety of tissue regeneration processes, such as bone regeneration and wound healing9,10,11. Regardless of if the wound is caused by traumatic or pathological means, impairment of the PNS can result in abnormal tissue repair or failure to heal. The primary functions of innervation during wound healing include axonal sprouting and secretion of growth factors that act in conjunction with other cells12. Studies have shown delayed inflammatory infiltration, decreased macrophage counts, and ultimately delayed wound healing during denervated wound healing13. It has been shown that CGRP from sensory nerves promotes wound healing by regulating the repair function of macrophages during wound healing14. In addition, in the process of skin tissue repair, sensory nerves communicate with immune cells through pathways such as IL-17 to promote tissue repair15. Previous literature has shown that crosstalk between muscularis macrophages and enteric neurons regulates gastrointestinal motility through CSF1/BMP216. Sensory neuron-derived TAFA4 has been shown to regulate macrophage tissue repair to promote skin reconstruction in a sunburn model8. All these results indicate the important role of neuroimmune interaction in skin tissue repair. In the process of wound healing, sensory nerves may communicate with immune cells in various ways to promote wound healing. However, how the peripheral nervous system regulates macrophages and nerve-macrophage interactions during skin wound healing is still unclear.

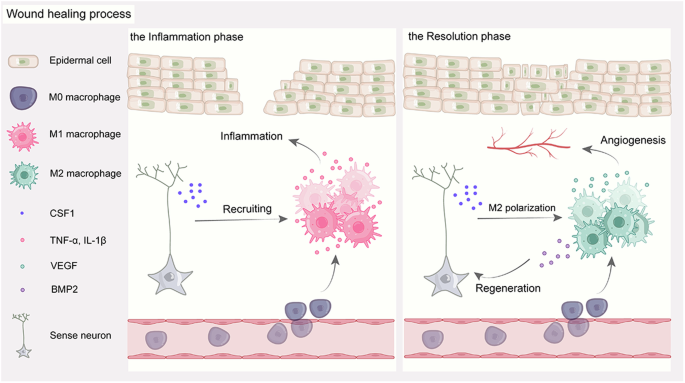

To further elucidate the role of crosstalk between neurons and macrophages in skin wound healing, we used a denervated wound model to observe changes in macrophages and their subpopulations and analyzed related molecular alterations by bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). In this study, we revealed a neuroimmune regulatory pathway driven by peripheral nerve-derived CSF1 that induces BMP2 expression in prorepair macrophages and enhances nerve regeneration. Crosstalk between neurons and macrophages facilitates the healing process of wounds and provides a potential strategy for wound healing therapy (Fig. 1).

Schematic illustration of how peripheral nerve-derived CSF1 induces BMP2 expression in macrophages to promote nerve regeneration and wound healing.

Results

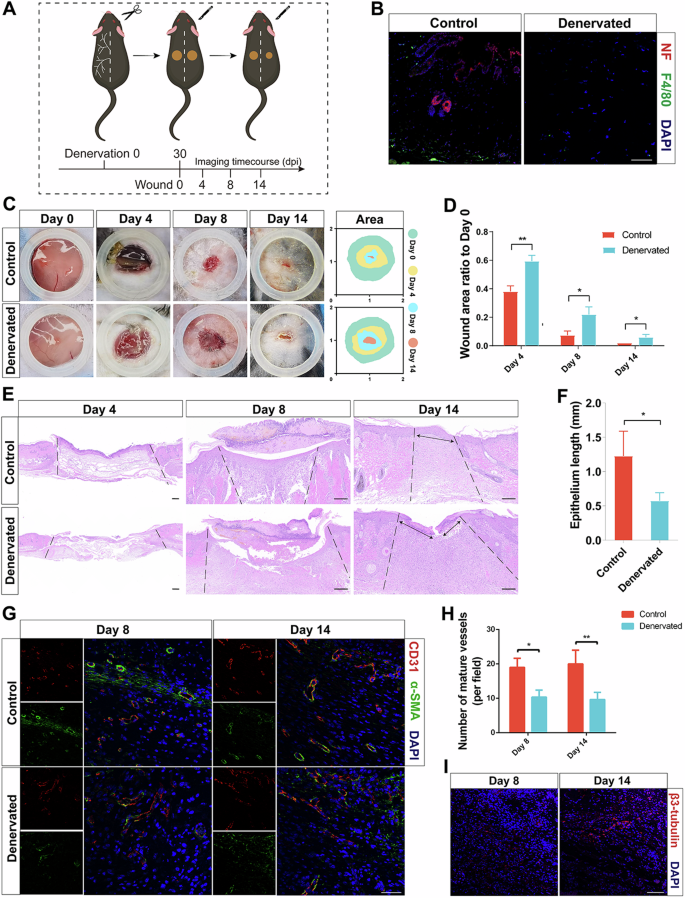

Skin denervation impairs wound angiogenesis and re-epithelialization

To elucidate the role of nerve innervation on skin wound healing, we used a denervated wound model to study the process of wound healing. The unilateral dorsal skin was denervated, leaving the left side of the skin with intact innervation as the control group, and only the nerves emanating from the right side of the spinal cord (T3-T12) were removed (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. 1). The mice were then allowed to recover for 1 month to allow any transient inflammation from the procedure to subside. To analyze the effect of sensory nerve ablation on wound healing, we created full-thickness wounds of equal size on the denervated and intact sides of the dorsal skin. Skin biopsies were also collected from the wounds and evaluated histologically, confirming the effective removal of the nerves (Fig. 2B). Quantification of the wound healing rate showed that wound healing was significantly delayed on the denervated side of the dorsal skin (Fig. 2C,D). More importantly, the difference in wound healing rates between these two regions was greatest during the first 8 days after injury, which may reflect the lack of some biological processes early in wound healing after denervation (Fig. 2C).

A Experimental schematic of denervation wound healing. B IF of NF and F4/80 in the skin of Control and Denervated wounds. Scale bar, 100 μm. C Photographs of Control and Denervated wounds at different time points. D Quantitative analysis of the relative wound areas at different times. E Representative H&E staining images of wounds at different times. Scale bar, 200 μm. F Quantitative analysis of the epithelium length at different times. G IF of CD31 and α-SMA in the skin of Control and Denervated wounds at different times. Scale bar, 200 μm. H Quantitative analysis of the number of mature vessels (per field) at different times. I IF of β3-tubulin in the skin of Control wounds on day 14. Scale bar, 200 μm. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m.

To explore the causes of delayed wound healing, we performed histological and immunological evaluations of the wound samples. Quantification of the wound epidermal length revealed a significantly longer wound epidermal length in the denervated group than in the control group on Days 8 and 14 and lower and discontinuous epithelialization in the denervated group (Fig. 2E, F). The IF staining results for the epidermal stem cell marker CK15 also supported the delayed wound healing (Supplementary Fig. 2). In addition, Sirius red staining revealed no significant difference in the collagen I/III ratio between the denervated and control groups (Supplementary Fig. 3A, B). Quantification of the number of blood vessels showed that the number of mature blood vessels in the denervated group was significantly less than that in the control group, which may partly explain the delay in wound healing (Fig. 2G,H). In addition, the number of regenerated nerves in the control group increased over time (Fig. 2I). These results suggest that the cause of delayed wound healing after skin denervation may be a decrease in the number of mature blood vessels. Importantly, previous literature suggests that macrophages play a key role in angiogenesis during wound healing17. Therefore, macrophages may play an important role in wound healing after skin denervation.

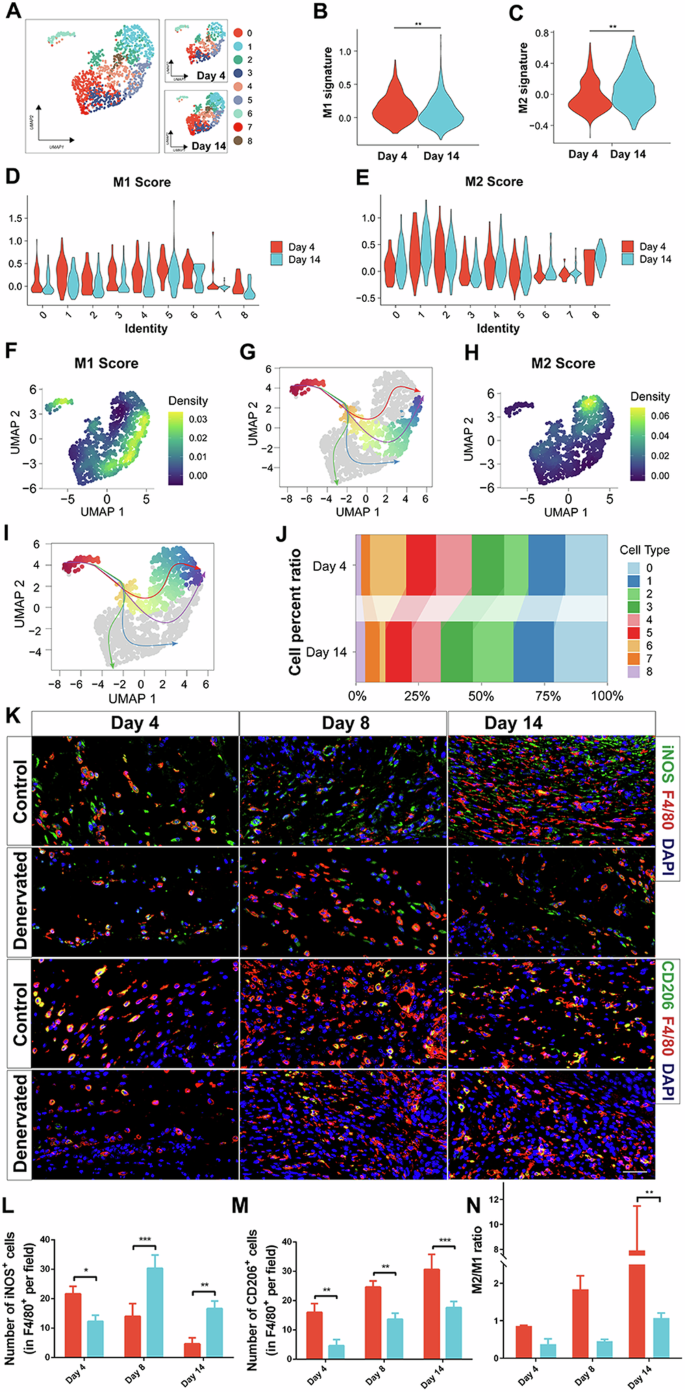

The fate of macrophages is altered upon loss of nerve interactions

To investigate the heterogeneity of macrophage subtypes in different stages of wound healing, we obtained a single-cell dataset (GSE183489) from the GEO database, which included macrophage data from Day 4 and Day 14 wound sites. Following stringent quality control measures, we applied dimensionality reduction and clustering techniques to identify distinct macrophage clusters. A total of nine macrophage clusters were selected for further analysis (Fig. 3A), and the proportions of these clusters at different time points were visualized (Fig. 3J).

A The UMAP plot illustrates the distribution of macrophage clusters. B−E Violin plots depict the expression profiles of M1 and M2 macrophages at days 4 and 14, respectively. F, H Boxplots display the distribution of M1 and M2 scores within the macrophage clusters. G, I The differentiation trajectories of macrophages are visualized. J A proportion plot represents the distribution of macrophage clusters. K IF of iNOS, CD206, and F4/80 in the skin of Control wounds on day 14. Scale bar, 200 μm. L Quantitative analysis of the number of iNOS+ cells (in F4/80+ per field) at different times. M Quantitative analysis of the number of CD206+ cells (in F4/80+ per field) at different times. N Quantitative analysis of M2 to M1 ratio at different times. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; **** < 0.0001. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m.

Furthermore, we explored the activation status of M1 and M2 macrophages at different time points. The results revealed that M1 macrophage scores were greater for macrophages from the Day 4 wound site than for those from the Day 14 wound site, while M2 macrophage scores were greater for macrophages from the Day 14 wound site than for those from the Day 4 wound site (Fig. 3B−E). We also visualized the distribution of M1 and M2 signatures within the identified cell subgroups. Clusters 3, 5, and 6 exhibited predominant enrichment of the M1 signature, whereas Clusters 1 and 2 showed prominent enrichment of the M2 signature (Fig. 3F, H). Furthermore, through pseudotime analysis, we discovered four differentiation trajectories of macrophages (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). We visualized two of these trajectories, corresponding to high M1 and M2 scores (Fig. 3G, I).

To further confirm the changes in macrophage phenotype in denervated wounds during the healing process, we observed the distribution of macrophage subpopulations at different time points by IF staining (Fig. 3K). Like in previous studies, macrophage infiltration was delayed, and macrophage numbers were reduced during denervation-related wound healing18. Consistent with the results of the scRNA-seq data described above, proinflammatory macrophages, or M1 macrophages, predominated in the early stages of wound healing, and repaired macrophages, or M2 macrophages, predominated in the late stages of wound healing. As shown in Fig. 3D, compared with that of M1 macrophages in the control wounds, the number of M1 macrophages was significantly lower in the denervated wounds on Day 4, but the number of M1 macrophages was significantly greater on Days 8 and 14 (Fig. 3L). In addition, compared with on the number of M2 macrophages in the control wounds, the number of M2 macrophages on Days 4, 8, and 14 was significantly lower in denervated wounds (Fig. 3M). The M2-to-M1 ratio did not significantly differ between the denervated wounds and control wounds in the early stage of wound healing, but in the late stage of wound healing, the control wounds were significantly dominated by prorepair macrophages, thus leading to significantly better wound healing than that of the denervated wounds (Fig. 3N). These results indicate that peripheral nerves not only promote early macrophage infiltration in wounds but also regulate M2 macrophage polarization to promote wound healing.

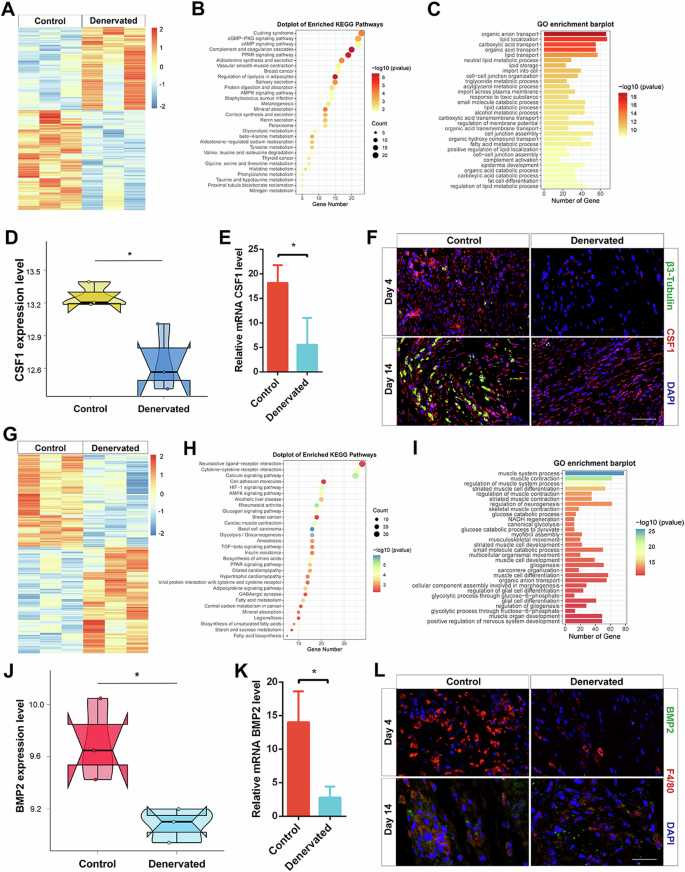

CSF1 from peripheral nerves in the early stage and BMP2 from macrophages in the late stage are required for wound healing

To further analyze the transcriptional profiles of denervated wound healing at different time points, we isolated wound tissues at the early (Day 4) and late (Day 14) stages of healing for bulk RNA-seq analysis (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7).

According to the literature, CSF1, a signaling molecule released after peripheral nerve injury, regulates the activation and proliferation of spinal microglia, thereby signaling to nonneurons and promoting the transmission of pain, which plays an important role in the development and maintenance of neuropathic pain19. In addition, CSF1 can promote the generation of a new subset of tissue repair macrophages in traumatic brain injury, thereby accelerating tissue repair20. Based on the results in Fig. 3, which show a decrease in the number of denervated wound macrophages and a delay in the inflammatory phase, we examined the expression of CSF1, which is of peripheral nerve origin and associated with macrophage recruitment, in the sequencing data.

By comparing the gene expression profiles between the Day 4 denervated wound group and the control group, we identified numerous significant differentially expressed genes. Specifically, we selected 708 upregulated and 590 downregulated genes (Fig. 4A). We performed KEGG and GO enrichment analyses on these DEGs and presented the top 30 enriched pathways for each analysis (Fig. 4B,C). KEGG enrichment analysis revealed significant enrichment of pathways such as the PPAR signaling pathway, complement and coagulation pathway, and AMPK signaling pathway. Additionally, the GO enrichment analysis highlighted prominent enrichment in processes such as neutral lipid metabolic process, cell‒cell junction organization, and lipid localization.

A Heatmap displaying the distribution of DEGs between the day 4 control group and the denervated group. B KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs between the control and denervated groups at day 4 wound tissues. C GO enrichment analysis of DEGs between the control and denervated groups at day 4 wound tissues. D Quantitative analysis of CSF1 expression level in bulk RNA-seq data on day 4. E qRT-PCR analysis of mRNA CSF1 expression level in Control and Denervated wound tissues on day 4. F IF of β3-tubulin and CSF1 in the skin of Control and Denervated wounds on day 4 and 14. Scale bar, 200 μm. G Heatmap displaying the distribution of DEGs between the day 14 control group and the denervated group. H KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs between the control and denervated groups at day 14 wound tissues. I GO enrichment analysis of DEGs between the control and denervated groups at day 14 wound tissues. J Quantitative analysis of BMP2 expression level in bulk RNA-seq data on day 14. K qRT-PCR analysis of mRNA BMP2 expression level in Control and Denervated wound tissues on day 14. L IF of BMP2 and F4/80 in the skin of Control and Denervated wounds on day 4 and 14. Scale bar, 200 μm. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m.

CSF1 expression in the bulk RNA-seq data on Day 4 was significantly higher in the control group than in the denervated group (Fig. 4D). Total RNA was extracted from the wound tissue on Day 4 to determine the CSF1 mRNA expression level, and the results were consistent with the results of the bulk RNA-seq data (Fig. 4E). In addition, the IF results also showed downregulated peripheral nerve-derived CSF1 expression in the denervated group compared with the control group during early wound healing (Fig. 4F).

Previous literature has shown that M2 macrophages can promote nerve regeneration during tissue repair16. Therefore, in conjunction with the conclusion that the late stages of healing in normal skin wounds are dominated by M2 macrophages. Previous literature has shown that BMP2 can regulate nerve regeneration, which has been widely demonstrated in the field of tissue regeneration16,21,22. As shown in Fig. 3, we investigated the role of BMP2 expression in M2 macrophages in nerve regeneration by sequencing.

To identify the DEGs between the Day 14 denervated wound group and the control group, we selected 737 upregulated and 642 downregulated genes as DEGs (Fig. 4G). Subsequently, we performed KEGG and GO enrichment analyses on these DEGs and presented the top 30 enriched pathways for each analysis (Fig. 4H, I). KEGG enrichment analysis revealed significant enrichment of pathways related to neuroactive ligand‒receptor interactions, cell adhesion molecules, and the TGF-beta signaling pathway. These findings suggest the involvement of these pathways in the denervated wound healing response on Day 14. Furthermore, the GO enrichment analysis highlighted prominent enrichment in processes such as the regulation of neurogenesis, muscle system processes, and muscle contraction. These results provide insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying neuronal and muscular changes during the denervated wound healing process on Day 14.

Analysis of BMP2 expression in the bulk RNA-seq data on Day 14 showed that BMP2 expression was significantly higher in the control group than in the denervated group (Fig. 4J). Total RNA was extracted from the wound tissue on Day 14 to determine the BMP2 mRNA expression level, and the results were consistent with the results of the bulk RNA-seq data (Fig. 4K). In addition, the IF results also showed reduced levels of macrophage-derived BMP2 expression in the denervated group compared to the control group during late wound healing (Fig. 4L).

CSF1 from neurons induces M2 macrophage polarization in vitro

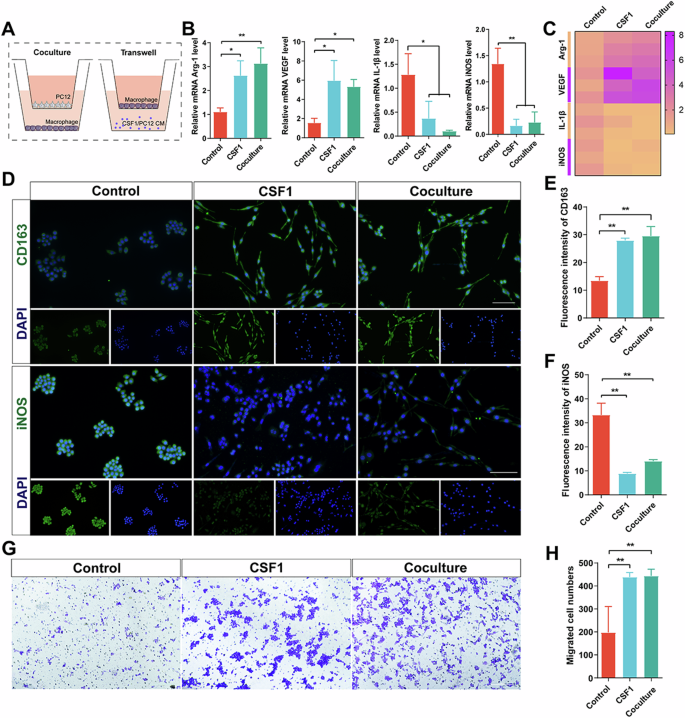

To further elucidate the relationship between peripheral nerve-derived CSF1 and macrophages, we validated the results in coculture plates by using Transwell chambers (Fig. 5A). An ELISA was used to measure the secretion levels of CSF1 in the supernatants of PC12 cells, and the results showed that the level of CSF1 in the conditioned medium of PC12 cells was higher than that in the control group (Supplementary Fig. 8A). We first inoculated macrophages in the lower chamber and PBS. PC12 cells and CSF1 (100 ng/mL) were added to the upper chamber and then cultured in the incubator for 48 h. qRT‒PCR revealed elevated expression levels of Arg-1 and VEGF and decreased expression levels of IL-1β and iNOS in the coculture and CSF1 groups compared to the control group (Fig. 5B). It is also evident from the mRNA expression heatmap that the coculture and CSF1 groups exhibited altered expression of M2 macrophage-related markers (Fig. 5C). Next, immunofluorescence staining was used to verify the expression of the M2 macrophage marker CD163 and the M1 macrophage marker iNOS (Fig. 5D). As shown in Fig. 5D, macrophages in the coculture and CSF1 groups were polarized with elongated cell projections, yet macrophages in the control group remained round. Quantitative analysis of the coculture and CSF1 groups revealed significantly higher CD163 expression and significantly lower iNOS expression in the co-culture and CSF1 groups than the control group (Fig. 5E, F). We then inoculated macrophages in the upper chamber, and PBS, PC12 cells, and CSF1 (100 ng/mL) were added to the lower chamber and cultured in the incubator for 48 h. The Transwell migration assay was used to assess the migration of cells after different treatments (Fig. 5G). Quantitative analysis of the coculture and CSF1 groups revealed an increase in the number of cells that migrated compared to that in the control group (Fig. 5H). The above in vitro results tentatively suggest that neuronal cells can induce M2 macrophage polarization by secreting CSF1.

A Experimental schematic of coculture and transwell assay. B qRT-PCR analysis of expression level of mRNA Arg-1, VEGF, IL-1β, and iNOS in macrophages of different treatments. C The heatmap of expression level of mRNA Arg-1, VEGF, IL-1β, and iNOS. D IF of CD163 and iNOS in macrophages of different treatments. Scale bar, 100 μm. E Quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity of CD163. F Quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity of iNOS. G Transwell assay of macrophages of different treatments. Scale bar, 100 μm. H Quantitative analysis of migrated cell numbers. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m.

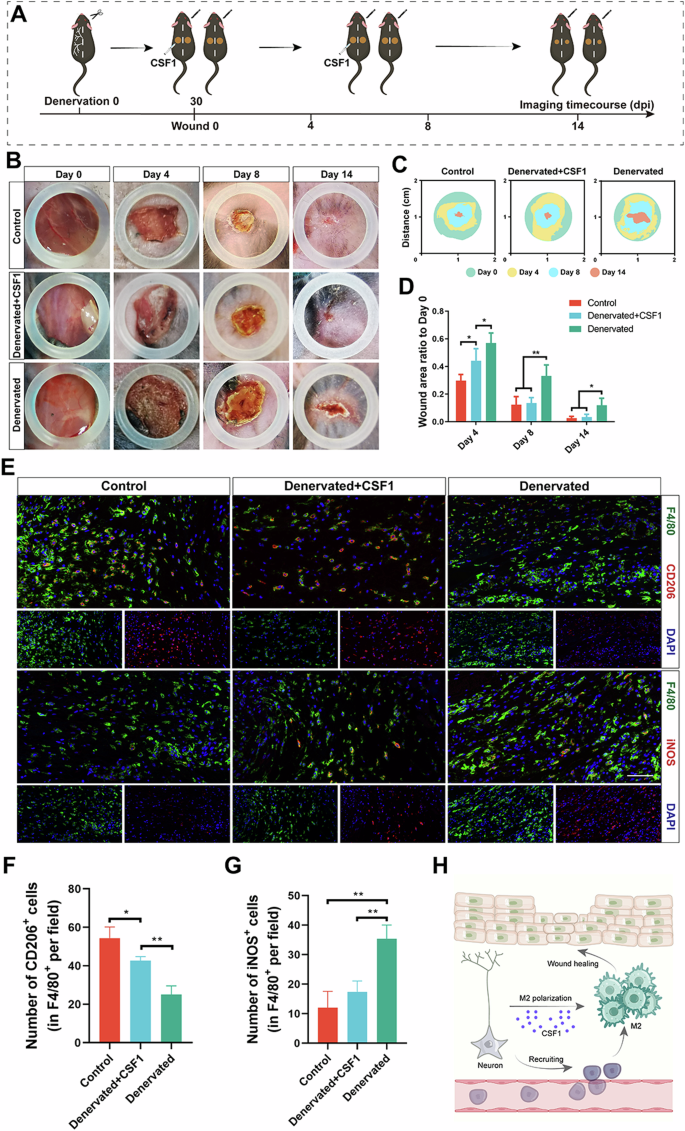

CSF1 promotes wound healing by inducing M2 macrophage polarization

To test whether CSF1 is a key factor in peripheral nerves influencing macrophage polarization and wound healing, we investigated the role of CSF1 in a denervated wound model. After the denervated wound model was established, CSF1 was used to treat the wound in the early stage of healing (Fig. 6A). As shown in Fig. 6B, treatment of denervated wounds with CSF1 significantly accelerated wound healing. In the early stage of wound healing, the control group healed faster than the denervated group (Fig. 6C). However, the addition of CSF1 to denervated wounds accelerated wound healing, possibly through the promotion of macrophage proliferation in the early stage of healing and the induction of macrophage polarization in the late stage of healing (Fig. 6D). To explore the causes of accelerated wound healing, we performed an immunological evaluation of the wound samples (Fig. 6E). As shown in Fig. 6E, compared with that in the denervated group, the number of macrophages was significantly increased on Day 14 after the addition of CSF1 to the denervated wound, the number of M2 macrophages was significantly increased (Fig. 6F), and the number of M1 macrophages was significantly decreased (Fig. 6G). There was no difference in the degree of macrophage polarization between the denervation plus CSF1 group and the control group. In conclusion, peripheral nerves regulate M2 macrophage polarization by secreting CSF1 to accelerate wound healing (Fig. 6H).

A Experimental schematic of denervated wound healing with CSF1 treatment. B Photographs of Control, Denervated+CSF1, and Denervated wounds at different time points. C Superimposed wounds images of Control, Denervated+CSF1, and Denervated wounds at different time points. D Quantitative analysis of the relative wound areas at different times. E IF of CD206 and iNOS in macrophages of different treatments. Scale bar, 200 μm. F Quantitative analysis of the number of CD206+ cells (in F4/80+ per field) on days 14. G Quantitative analysis of the number of iNOS+ cells (in F4/80+ per field) on days 14. H Schematic representation of the mechanism by which peripheral nerve-derived CSF1 regulates M2 macrophage polarization. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m.

BMP2 in M2 macrophages promotes nerve regeneration in vitro

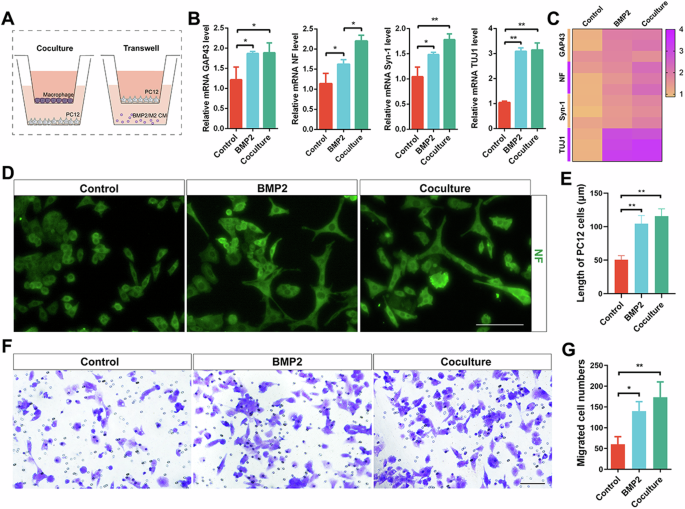

To further elucidate the relationship between macrophage-derived BMP2 and peripheral nerves, we validated the results using Transwell assays (Fig. 7A). An ELISA was used to measure the secretion levels of BMP2 in the supernatants of M2 macrophages induced by CSF1, and the results showed that the level of BMP2 in the conditioned medium of M2 macrophages was higher than that in the control group (Supplementary Fig. 8B). We first inoculated PC12 cells in the lower chamber, and PBS, macrophages, and BMP2 (100 ng/mL) were added to the upper chamber and then cultured in the incubator for 48 h. The qRT‒PCR results revealed upregulated expression of GAP43, NF, Syn-1, and TUJ1 in the coculture and BMP2 groups compared to the control group (Fig. 7B). It is also evident from the mRNA expression heatmap that the coculture and BMP2 groups exhibited altered expression of PC12 cell-related markers (Fig. 7C). Next, immunofluorescence staining was used to verify the expression of the PC12 cell marker NF (Fig. 7D). As shown in Fig. 7D, PC12 cells in the coculture and BMP2 groups exhibited an elongated macrophage-like morphology, yet PC12 cells in the control group remained round. Quantitative analysis revealed that the PC12 cells in the coculture and BMP2 groups were significantly longer than those in the control group (Fig. 7E). We then inoculated PC12 cells in the upper chamber, and PBS, macrophages, and BMP2 (100 ng/mL) were added to the lower chamber and cultured in the incubator for 48 h. The Transwell migration assay was used to assess the migration of cells after different treatments (Fig. 7F). Quantitative analysis of the coculture and BMP2 groups revealed an increase in the number of cells that migrated compared to that in the control group (Fig. 7G). The above in vitro results suggest that M2 macrophages can induce PC12 cell regeneration by secreting BMP2.

A Experimental schematic of coculture and transwell assay. B qRT-PCR analysis of expression level of mRNA GAP43, NF, Syn-1, and TUJ1 in PC12 cells of different treatments. C The heatmap of expression level of mRNA GAP43, NF, Syn-1, and TUJ1. D IF of NF in PC12 cells of different treatments. Scale bar, 100 μm. E Quantitative analysis of length of PC12 cells. F Transwell assay of PC12 cells of different treatments. Scale bar, 100 μm. G Quantitative analysis of migrated cell numbers. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m.

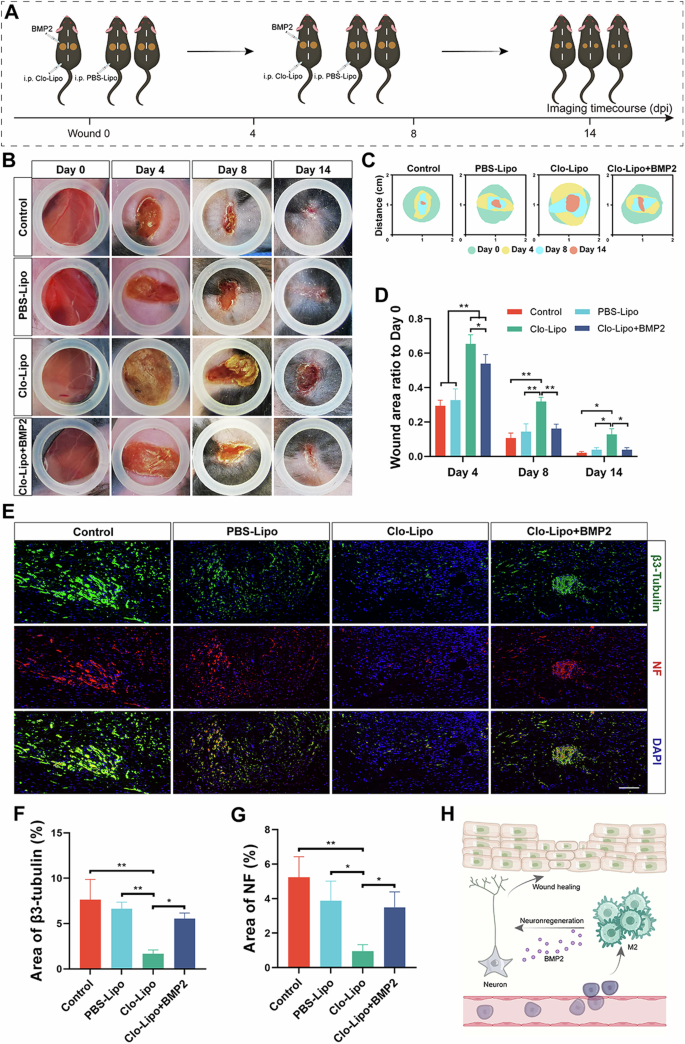

BMP2 promotes wound healing by inducing nerve regeneration

To test whether BMP2 contributes to the effects of M2 macrophages on peripheral nerve regeneration and wound healing, we investigated the effects of BMP2 using a macrophage depletion wound model. After the macrophage depletion wound model was established, BMP2 was used to treat the wound in the early stage of healing (Fig. 8A). As shown in Fig. 8B, treatment of the Clo-Lipo group with BMP2 significantly accelerated wound healing. In the early stage of wound healing, the wounds in the control group healed faster than those in the Clo-Lipo group (Fig. 8C). However, the addition of BMP2 to the wounds of the Clo-Lipo group accelerated wound healing, possibly through the promotion of nerve regeneration during the process of healing (Fig. 8D). To explore the causes of accelerated wound healing, we performed an immunological evaluation of the wound samples (Fig. 8E). As shown in Fig. 8E, compared with that in the Clo-Lipo group, the number of regenerated nerves was significantly greater on Day 14 after the addition of BMP2 to the wounds in the Clo-Lipo group, and the areas of positive β3-tubulin and NF staining were significantly increased (Fig. 8F, G). There was no difference in the degree of macrophage polarization between the Clo-Lipo plus BMP2 group and the PBS-Lipo group. In conclusion, M2 macrophages regulate peripheral nerve regeneration by secreting BMP2 to accelerate wound healing (Fig. 8H).

A Experimental schematic of macrophage depletion wound wound healing with BMP2 treatment. B Photographs of Control, PBS-Lipo, Clo-Lipo, and Clo-Lipo+BMP2 wounds at different time points. C Superimposed wounds images of Control, PBS-Lipo, Clo-Lipo, and Clo-Lipo+BMP2 wounds at different time points. D Quantitative analysis of the relative wound areas at different times. E IF of β3-tubulin and NF in nerves of different treatments. Scale bar, 200 μm. F Quantitative analysis of the area of β3-tubulin on days 14. G Quantitative analysis of the area of NF on days 14. H Schematic representation of the mechanism by which M2 macrophages-derived CSF1 regulates peripheral nerves regeneration. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m.

Discussion

We revealed a neuroimmune regulatory pathway driven by peripheral nerve-derived CSF1 that induces BMP2 expression in prorepair macrophages and enhances nerve regeneration. Crosstalk between neurons and macrophages facilitates the healing process of wounds and provides a potential strategy for wound healing therapy. The role of macrophages in tissue regeneration has been the subject of intense research for decades. Macrophages are a special type of immune cell that play key roles in a variety of physiological and pathological processes. These cells are not only involved in the immune response but also closely related to the normal functions of many tissues and organs. In-depth studies of macrophages will not only help us to better understand their role in health and disease but also may provide important clues for the development of new therapeutic strategies17. At present, the mainstream view is that M1 macrophages are the main type of macrophage in the early stage of wound healing and promote inflammation, inflammatory cells, and angiogenesis, while M2 macrophages are the main type of macrophage in the late stage of wound healing. and promote vascular maturation, regulate collagen remodeling, and accelerate nerve repair4,23,24. After skin injury, the body reacts quickly to close off the wound and induce vasoconstriction, and then inflammatory cells subsequently enter the injured area in large numbers. Tissue-resident macrophages and monocyte-derived macrophages jointly form the innate immune system in the early stage of wound healing to affect the process of wound healing25. However, how macrophages are recruited and regulated to exert their corresponding functions in the process of wound healing is unclear.

Wound healing is an extremely complex process, which is not a physiological process that can be determined by any cell or molecular mediator, but a process that all cells and related molecular mediators interact and cooperate to promote skin tissue. CSF1 and BMP2 of interest in this study were the key molecular mediators screened by sequencing, and their roles in wound healing and neuroimmune interactions were verified by relevant experiments. Previous literature has shown that peripheral nerves play important roles in tissue regeneration, including immune regulation, collagen remodeling regulation, angiogenesis, and re-epithelialization16,26,27,28. The regulation of peripheral nerves by the immune system plays an important role in various systems of the body. Peripheral nerves can regulate the phenotype of macrophages. In addition, macrophages also play important roles in physiological and pathological processes involving peripheral nerves29,30,31. In this study, the peripheral nerve was removed by surgery to construct a wound model. This method can completely remove the subcutaneous peripheral nerve, which is beneficial for studying the role of peripheral nerve in wound healing and how it regulates other cell subsets. However, this approach does not distinguish between sympathetic or sensory neuronal subsets, and it is not clear which type of neuron regulates macrophages. Chemical ablation methods such as 6OHDA and gene knockout mice can more clearly observe the effect of certain types of neurons on wound healing14,32. The purpose of this study is to explore the effect of peripheral nerves on wound healing and the regulation of macrophages, so the selected surgical removal of peripheral nerves can meet the needs. Our results suggested that peripheral nerves could promote wound healing by regulating M2 macrophage polarization through CSF1 secretion. According to the literature, CSF1, a signaling molecule released after peripheral nerve injury, regulates the activation and proliferation of spinal microglia, thereby signaling to nonneurons and promoting the transmission of pain, which plays an important role in the development and maintenance of neuropathic pain19. In addition, CSF1 can promote the generation of a new subset of tissue repair macrophages in traumatic brain injury, thereby accelerating tissue repair20. However, CSF1 can significantly affect macrophage differentiation, proliferation and activity33,34. In this study, we found that the expression of CSF1 in the control group was significantly upregulated compared to that in the denervated group by bulk RNA-seq, indicating that peripheral nerves can affect the expression of CSF1 in wound tissue. Furthermore, we verified that peripheral nerve-derived CSF1 can regulate the polarization of M2 macrophages. In the early stage of wound healing, the differentiation, proliferation, and migration of macrophages are mediated by CSF1, and importantly, this process is regulated by peripheral nerves.

It has been reported that macrophages play a critical role in physiological and pathological processes involving peripheral nerves. During nerve injury, macrophages not only phagocytose cell debris but also activate M2 macrophages to regulate the regeneration of peripheral nerve axons35,36,37. In addition, macrophages can secrete a variety of cytokines to regulate angiogenesis to provide nutrients and regulate Schwann cells to promote nerve regeneration38,39,40. Previous literature has shown that BMP2 can regulate nerve regeneration, which has been widely demonstrated in the field of tissue regeneration16,21,22. In this study, we found that the expression of BMP2 in the control group was significantly upregulated compared with that in the denervated group by bulk RNA-seq, and further, we verified that M2 macrophage-derived BMP2 can regulate peripheral nerve regeneration. In the late stage of wound healing, peripheral nerve regeneration is mediated by BMP2, and importantly, this process is regulated by macrophages.

In this study, we revealed a neuroimmune regulatory pathway driven by peripheral nerve-derived CSF1 that promotes the prorepair functions of macrophages and upregulates BMP2 expression in prorepair macrophages to enhance nerve regeneration. Crosstalk between neurons and macrophages facilitates the healing process of wounds and provides a potential strategy for wound healing therapy. Considering our findings and the previous literature, we showed that simultaneous activation of peripheral nerves and macrophages is a very promising strategy for promoting wound healing. However, this study only used surgical denervation and bulk RNA-seq to explore the mechanism, which cannot reflect the neuronal subsets and macrophage subsets that play key roles in the process of wound healing, and did not use cell-specific gene ablation to explore the mechanism of neuroimmune interaction. In the future, we will further explore the role of neuroimmune regulation in wound healing using cell-specific gene ablation and single-cell RNA-seq in vivo validation. Meantime, RAW 264.7 cell line and PC12 cell line representing macrophages and neurons, respectively, were used to validate the key mechanisms of the obtained neuroimmune regulation in this study. At the same time, due to the use of cell lines, it is not very accurate to reflect the phenotypic changes of the primary cells themselves, resulting in the limitation of the conclusions. In the future, it is highly desirable to use DRG neurons and primary macrophages to validate the key mechanisms of neuroimmune regulation in vitro to eliminate the limitations imposed by cell lines.

Methods

Animals

All animal surgical procedures and protocols used were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Fourth Military Medical University. All animal experiments should comply with the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Wild-type C57BL/6J mice aged 6−8 weeks were used for animal experiments, and all the mice were fed a diet under standard conditions.

Denervation surgery

The peripheral nerves of the dorsal skin were severed using microsurgery41,42. Briefly, mice were anesthetized via isoflurane inhalation. The plane of surgical anesthesia was confirmed by the absence of a pedal reflex response after physical stimulation. An incision of approximately 4.5−5 cm was made along the dorsal midline using surgical scissors, and the skin of the right dorsum was bluntly detached to expose the cutaneous nerves (T3-T12) on the right side of the animal. The right cutaneous nerve was then removed by blunt dissection approximately 0.5 cm below the skin incision near the right side. All nerves on the left side were left intact with only blunt subcutaneous detachment. Finally, the initial dorsal skin incision was closed with sutures. Wound experiments were performed 1 month after the end of the denervation procedure.

Wound healing assays

Mice that were at least eight weeks old were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation. The plane of surgical anesthesia was confirmed by the absence of a pedal reflex response after physical stimulation. A full-thickness skin wound approximately 1 cm in diameter was constructed with a biopsy punch on each side of the midline of the back of each mouse in the experiment. The denervation wound model was constructed 1 month after completion of the denervation procedure by constructing a full-thickness skin wound as described above. CSF1 (MedChemExpress) recombinant protein (100 ng) was injected subcutaneously into the wounds on Days 0, 2, 4, and 6 early in the denervation surgery. Moreover, a macrophage depletion model was established in mice without denervation. After the full-thickness skin wounds were constructed as described above, the mice were randomly divided into four groups and injected intraperitoneally with 100 μL of clodronate liposomes (Clo-Lipo, Yeasen), plain control liposomes (PBS-Lipo, Yeasen), or PBS in the early stage of wound healing on Days 0, 2, 4, and 643. Next, 100 ng of recombinant BMP2 (MedChemExpress) protein was injected subcutaneously in the left side of the clodronate-liposome group in the late stage of wound healing on Days 6, 8, 10, and 12. After the mice were sacrificed, full-thickness skin approximately 1.5 cm in diameter was collected from the wound and surrounding area for subsequent analysis.

RNA extraction and library construction

Full-thickness puncture biopsies were performed on the skin of denervated wounds and control wounds from 3 wounds of 3 mice for quantitative RNA sequencing on Days 4 and 14. RNA extraction was carried out using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol to isolate and purify total RNA from the wound tissues. The quantity and purity of the extracted RNA samples were assessed using a NanoDrop ND-1000 (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE, USA). The integrity of the RNA was evaluated using a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, CA, USA) based on an RNA integrity number (RIN) greater than 7.0. Additionally, electrophoresis with a denaturing agarose gel was performed to confirm RNA integrity.

Poly(A) RNA enrichment was carried out using Dynabeads Oligo (dT) 25-61005 (Thermo Fisher, CA, USA) through two rounds of purification from 1 μg of total RNA. Subsequently, the poly(A) RNA was fragmented using the Magnesium RNA Fragmentation Module (NEB, cat. e6150, USA) at 94 °C for 5–7 minutes. The resulting fragmented RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA with SuperScript™ II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, cat. 1896649, USA). To generate U-labeled second-stranded DNAs, E. coli DNA polymerase I (NEB, cat. m0209, USA), RNase H (NEB, cat. m0297, USA), and dUTP Solution (Thermo Fisher, cat. R0133, USA) were used. An A-base was then added to the blunt ends of each strand in preparation for ligation to indexed adapters. The adapters contained T-base overhangs for ligating to the A-tailed fragmented DNA. Single- or dual-index adapters were ligated to the fragments, and size selection was performed using AMPureXP beads. After treatment with the heat-labile UDG enzyme (NEB, cat. m0280, USA) to remove the U-labeled second-strand DNA, the ligated products were subjected to PCR amplification under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min; 8 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 15 s, annealing at 60 °C for 15 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s; and a final extension step at 72 °C for 5 min. The resulting cDNA libraries had an average insert size of 300 ± 50 bp. Finally, paired-end sequencing (PE150) was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq™ 6000 platform (LC-Bio Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) according to the vendor’s recommended protocol.

Bulk RNA sequencing data analysis

The raw reads obtained from the bulk RNA sequencing were initially processed using fastp software (https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp) with default parameters to remove reads containing adaptor contamination, low-quality bases, and undetermined bases. The quality of the processed sequences was further assessed using fastp. To align the clean reads to the Homo sapiens GRCh38 reference genome, we employed HISAT2 (https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/hisat2). The mapped reads from each sample were subsequently assembled using StringTie (https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/stringtie) with default settings. Subsequently, all of the transcriptomes generated from individual samples were merged using gffcompare (https://github.com/gpertea/gffcompare/) to reconstruct a comprehensive transcriptome. Following the construction of the final transcriptome, the expression levels of all the transcripts were estimated using StringTie. Specifically, StringTie calculates the Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads (FPKM) to quantify mRNA expression levels (FPKM = [total_exon_fragments/mapped_reads(millions) × exon_length(kB)]. Differentially expressed mRNAs were identified using the R package DESeq2, with a significance threshold set at a p < 0.05. Finally, to gain insight into the biological functions of the differentially expressed genes, Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses were conducted using the clusterProfiler package.

Single-cell RNA sequencing data analysis

We conducted an analysis of the single-cell RNA sequencing dataset GSE183489, which comprises macrophage data from wound sites at 4-day and 14-day time points. The analysis was performed using the Seurat v.4 package in R v.4.3.1 (R Core Team, 2013), a widely used tool for processing, analyzing, and visualizing count matrices. Default parameters were employed for all functions unless otherwise specified. During the data processing, we excluded low-quality cells defined by their expression of fewer than 200 genes, more than 5000 genes, or a mitochondrial gene content exceeding 10%. Ultimately, a total of 1245 cells were retained for subsequent analysis. In the principal component analysis, we identified the top 3000 highly variable genes and utilized 15 principal components for dimensionality reduction and clustering. To mitigate batch effects, we applied the ‘harmony’ function to integrate the samples. By utilizing a graph-based clustering approach with a resolution set at 0.5, we derived unsupervised cell clusters and visualized the results using UMAP plots. To assess the scores of specific gene sets within each cell, we employed the ‘AddModuleScore’ function with default parameter settings. Additionally, we used the ‘Nebulosa’ R package to visualize the distribution of gene sets across the cell clusters. Finally, the ‘Slingshot’ R package was employed to investigate the differentiation status of the macrophage clusters.

Histological analysis and immunostaining

The skin wound tissue from mice was collected and fixed overnight with 4% paraformaldehyde. The fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin and then cut into 6 μm thick tissue sections for subsequent experiments. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Sirius red for histological analysis. For histologic analysis, the stained sections were viewed with an automated section scanner. Sirius red staining was visualized under a polarized light microscope. The ratio of collagen I/III in the tissue was quantified using ImageJ software.

For immunofluorescence (IF), tissues or cells were fixed for 30 min with 4% formaldehyde, blocked for 1 h with 5% BSA, and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS. The sections were incubated with anti-F4/80 (1:200, Abcam), anti-iNOS (1:200, Abcam), anti-CD206 (1:200, Abcam), anti-β3-tubulin (1:200, Abcam), anti-NF (1:200, Bioss), anti-α-SMA (1:50, Abcam), anti-CD31 (1:200, Abcam), anti-CSF1 (1:200, Affinity), anti-BMP2 (1:200, Affinity), and anti-CD163 (1:200, Affinity) antibodies overnight at 4 °C (1% BSA in PBS) and for 1 h at room temperature with secondary antibodies and DAPI. The following secondary antibodies were used: Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse (1:300; Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:400; Invitrogen), and goat anti-rabbit IgG Cy3 (1:400; Invitrogen).

Cell culture

Macrophages were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in DMEM (HyClone) containing 10% FBS (Gibco) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin solution (Gibco). PC12 cells were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 (HyClone) medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin solution (Gibco).

Cell migration assay

Transwell assays were performed to evaluate cell migration. Macrophages/PC12 cells (5 × 104 cells/well) were added to the upper chamber (8 μm) in 500 μL of DMEM/RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with serum-low medium. Approximately 600 μL of culture supernatant from the various samples was added to the lower chamber. After cultivation in an incubator at 37 °C for 48 h, the cells were stained with crystal violet.

Quantitative real-time PCR

TRIzol was used to extract total RNA from cells, after which PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Yeasen) was used to reverse transcribe the RNA into cDNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A Bio-Rad RT‒PCR system (Bio-Rad) was used to perform real-time PCR with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) serving as the internal reference; CSF1, BMP2, TUJ1, Syn-1, NF, GAP43, the M1 markers iNOS and IL-1β; and the M2 markers Arg-1 and VEGF. The sequences of primers used are provided in Table S1.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

After treating RAW 264.7 macrophages with PC12 cells and PBS for 48 h, the supernatant was collected. The secretion levels of the cytokine BMP2 were measured with commercial ELISA kits (Multisciences) following the manufacturer’s instructions. After RAW 264.7 macrophages were treated with PC12 cells and PBS for 48 h, the supernatant was collected. The secretion levels of the cytokine CSF1 were measured with commercial ELISA kits (Multisciences) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analyses

The data from three individual experiments are expressed as the means ± standard deviations (SD). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc test was performed for pairwise comparisons. To compare the means, two groups were analyzed with independent sample tests. A value of p < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Responses