Perspectives of chiral nanophotonics: from mechanisms to biomedical applications

Introduction

Chirality, a geometric property observed in objects that cannot be superimposed on their mirror images, is a fundamental characteristic prevalent across various natural and synthetic systems. This phenomenon is most commonly exemplified by our own hands, where the left and right hand are mirror images yet cannot be aligned to overlap completely. In the molecular realm, chirality plays a crucial role, particularly in the structure and function of biomolecules such as proteins, DNA, and many pharmaceutical compounds1. The handedness of these molecules, known as molecular chirality, can significantly influence biochemical interactions, with profound effects on biological processes, including drug efficacy and metabolism. Beyond molecular chirality, chirality is also evident at the cellular level. Cellular chirality refers to the asymmetric organization of cellular structures2 and functions3, which is critical for understanding asymmetric shape and position of internal organs, and related diseases4. The interplay between molecular and cellular chirality underpins many biological phenomena and has important implications for the development of chirality-based biomedical applications.

In the context of nanophotonics, chirality presents unique opportunities and challenges. The ability to detect and manipulate chiral signals at the nanoscale has profound implications for advancing our understanding of molecular interactions and developing novel applications, particularly in biomedical fields. Despite the established utility of chiral nanostructures in enhancing chiral signals, the intricate mechanisms underlying these enhancements remain only partially understood. Whether chirality is induced by asymmetric electron distributions5,6, superchiral field7,8,9,10,11, near-field enhancement12,13,14, or thermally induced refractive index changes affecting far-field properties15,16,17,18,19,20—all these factors are closely interconnected, making them difficult to distinguish from one another. This review seeks to bridge this knowledge gap by exploring various nanophotonic strategies designed to amplify and detect chiral signals with high sensitivity.

In this review, we will discuss traditional approaches to measuring chirality and contrast these with advanced techniques that leverage near-field interactions, such as plasmon-enhanced methods, chiral optical cavities, and photothermal approaches. Additionally, we will delve into the emerging use of tip-enhanced spectroscopy for localized chirality detection, which promises to overcome the limitations of ensemble measurements by providing spatially resolved insights into chiral behavior at the molecular level. Furthermore, we describe the potential applications in the biomedical domain. By elucidating the connections between different nanophotonic approaches and their corresponding mechanisms, we hope to pave the way for future innovations in this rapidly evolving field.

Traditional chiroptical approaches in measuring chirality

Optical activity refers to the ability of a chiral material to rotate the plane of polarized light. This phenomenon is intimately linked to the inherent asymmetry in the molecular structure. Circular dichroism (CD) is an absorption spectroscopy that measures the absorption differences between right- and left-handed circularly polarized light. Chiral molecules and nanostructures exhibit different absorption spectra depending on the light polarization. CD is defined as:

where ALCP and ARCP are the absorbance of left-handed and right-handed circularly polarization, respectively. The unpolarized light absorption is the averaged absorption in two circular polarizations.

In addition, the dissymmetry factor, anisotropy factor, or g-factor, which indicates the signal-to-noise ratio, was defined to normalize the small value of CD21, as described in Eq. (2). Another method to evaluate chirality is optical rotatory dispersion (ORD), which is defined as wavelength-dependent optical rotation, which is the rotation of polarization after light passes through the sample. Linearly polarized light can be decomposed into the sum of left- and right-handed circularly polarized light. When linearly polarized light travels through a chiral material, decomposed lights pass at different speeds, leading to phase differences between left- and right-handed circularly polarized light. These phase differences are called optical rotation or circular birefringence. Interestingly, CD is related to the imaginary part of the refractive index, while ORD is related to the real part of the refractive index. This implies that if we have the CD of a sample, we can derive its ORD and vice versa. CD is determined by a property known as absorption in the far-field. It can be measured through either transmission or reflection. For transparent substances like aqueous solutions, transmission is the primary method of measurement, while for opaque substances like metallic thin films, reflection-mode is widely used. Depending on the origin of CD, it can be categorized as either electronic or vibrational CD. CD occurring mainly in the ultraviolet region is called electronic CD (ECD) because it is caused by electronic transition. On the other hand, vibrational CD (VCD) is associated with vibrational transition in molecules and can be observed in the infrared region. In particular, infrared absorption reflects the vibration of chemical bonds in molecules, providing valuable molecular information. Therefore, visualizing VCD provides chemical information about the sample, similar to chemical imaging systems utilizing infrared absorption and Raman scattering22.

Unlike elastic scattering, such as Rayleigh and Mie scattering, where the frequency of light does not change when light is scattered, Raman scattering, which is molecular vibration-induced inelastic scattering, shifts the frequency of light. Raman scattering indicates vibrational modes of the molecules within materials, making it a widely used technique for investigating the intrinsic material properties23. Its ability to characterize the molecular bonds from vibrational fingerprint information in chirality detection has led to its widespread use in Raman optical activity24,25,26. Despite its high selectivity for distinguishing molecules within a compound, Raman scattering signals are often too weak to detect small amounts of chiral molecules. To address this, various methods have been developed to enhance Raman scattering, such as surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS)27,28,29, coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering30, stimulated Raman scattering31, and Tip-enhanced Raman scattering (TERS)32,33,34.

These traditional chiroptical approaches generally have lower sensitivity and selectivity than techniques such as chromatography and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, which are commonly used to detect chiral molecules as biomarkers, and often require a large volume of test samples1. Despite these disadvantages, chiroptical methods are more cost-effective than high-selective techniques and provide extremely fast responses to optical activities. If sensitivity and selectivity can be improved, chiroptical methods could become game-changers in biomedical diagnostic applications. In the next section, we briefly describe how nanophotonic approaches can enhance chirality detection.

How to enhance chirality detection using nanophotonics?

The optical activities discussed in the previous section arise from the electronic transition of a molecule and are fundamentally far-field characteristics. Chirality is dependent on a chiral molecule’s chemical and physical structure. However, far-field approaches only detect ensemble signals of the chiral molecules35,36, thereby limiting measurements to the concentration or dominance of chiral molecules in aqueous solution. This methodology provides insufficient information to fully understand the behavior and reactions of chiral molecules. To address this limitation, near-field characteristics must be employed to detect individual chiral molecules.

In recent decades, near-field optics have been developed to enhance optical responses at the nanoscale by leveraging light-matter interaction. When light interacts with a metallic nanoparticle or a dielectric/metal interface, it generates quasiparticles known as surface plasmons37. These surface plasmons create highly localized electromagnetic fields near the nanostructure, depending on the geometry of the structure and the incident light conditions38. This effect is known as light confinement. Various methods have been developed to achieve a small mode volume, which involves confining light in a space, and is commonly used in resonators39. For example, surface plasmon polaritons on a metallic film are confined along the z-axis40, resulting in one-dimensional confinement similar to a Fabry-Perot cavity41 and nanograting42. Whispering gallery modes43 and nanoslit44 can be viewed as types of 2D confinement, while near-fields formed in gaps such as dimers45, nanoparticles on a mirror (NPoM)46, and tip-enhanced near-fields47 can be considered as types of 3D confinement. This localized electromagnetic field is also amplified in intensity, which is called near-field enhancement. Near-field enhancement can amplify weak optical signals48,49 and has been utilized to detect particles with a high signal-to-noise ratio, as it can significantly enhance scattering signals from very small particles50,51,52. In addition, specific vibrational modes of molecules attached to a metallic surface have been augmented by surface electromagnetic fields53, leading to the development of highly selective sensing technologies such as SERS and surface-enhanced infrared absorption (SEIRA)54,55. In near-field optics, one important aspect to consider is light absorption. Near-field enhancement occurs when the energy from a photon is transferred to an electron, leading to the issue of Joule heating due to light absorption. This heat generation can cause unexpected noise and performance degradation, and has often been overlooked or evaded. Recently, thermal effects on plasmonics and metamaterials have been widely investigated for applications such as a nano heat source56, nonlinear effects57,58,59, and photoacoustics60,61.

Similarly, optical signals arising from chiral molecules can be enhanced through near-field enhancement. Interacting with molecular dipole and plasmon can enhance the intrinsic chirality of chiral molecules. In addition, new CD spectra formed by the interference between external and internal fields can appear at the plasmon resonance band, which has raised expectations for chiral sensing62. A strong electromagnetic field confined to the nanometer scale is able to measure a small amount of chiral molecule that endows local chirality in the racemate environment63,64. In particular, circular dichroism can be explained by the Born-Kuhn model, which is made of two orthogonally aligned oscillators coupled to each other65,66. The metallic nanorods can function as a dipolar antenna67, replacing oscillators to interpret chirality in plasmonic nanostructure. When the nanorods are coupled, they display bonding and antibonding modes based on the polarization of light excitation. The difference in energy levels between bonding and antibonding modes causes varying light absorption, resulting in circular dichroism. In addition to the simple explanation that near-field enhancement leads to strong chirality enhancement, plasmonic hybridization can result in different energy levels, which in turn lead to different light absorption depending on polarization68. This hybridization is one of the mechanisms for plasmon-coupled circular dichroism (PCCD). In addition, the chirality-enhanced electromagnetic field, known as a superchiral field, provides enhanced signals corresponding to the specific handedness of the chiral molecules7,8,9 compared to circular polarization. Chiral molecules exhibit different absorption characteristics depending on light polarization, resulting in different thermal responses that can be used to distinguish the handedness of chiral molecules. The various aspects of nanophotonics, such as near-field enhancement, light confinement, and light absorption, can be effectively used for chirality detection. However, due to the interdependence of these properties, it is challenging to ascertain one primary mechanism at play. In the following sections, we will review several nanophotonic strategies to enhance and measure chirality, including the structural aspect of plasmonic approaches, tip-enhanced chirality detection, chiral optical cavities with chiral mirrors, and photothermal approaches.

Nanoparticle resonator-based chirality sensing

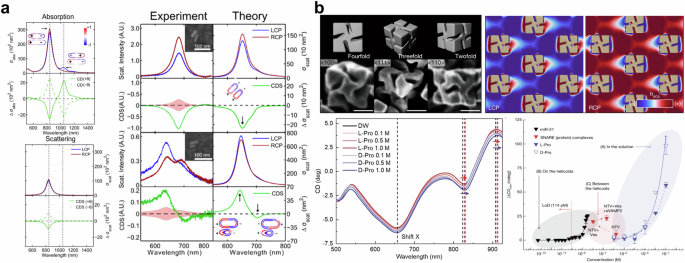

The chirality of small molecules is typically determined using absorption CD spectroscopy. However, larger macromolecules such as proteins and plasmonic nanostructures exhibit differences in scattering due to their size. The Link group reported the use of circular differential scattering to investigate the CD of a single nanoparticle69. This method is based on the dark field measurement combined with the spectral imaging technique70. They investigated the circular differential scattering of gold nanorod dimers, which is induced by a dipolar mode of surface plasmon. The results supported the prediction that the chirality induced by gold nanorod dimers is described with plasmon hybridization theory, which describes the coupling of different plasmonic modes68,71,72,73. As presented in Fig. 1a (left), the absorption spectrum has two resonant modes at 843 (antibonding) and 1049 nm (bonding mode), while the scattering spectrum shows only one resonance at 843 nm. At the bonding mode, anti-symmetric aligned charge density may cancel out scattering effects due to lower polarizability65,72. As shown in Fig. 1a (right-bottom), the bisignate circular differential scattering line can be only observed in the heterodimer, which is formed by different sizes of nanorods, whereas the homodimer has no bisignate response (Fig. 1a (right-top)). This indicates that symmetry breaking from an aligned angle and size mismatch of nanorods induces chirality. Using identical measurements, Zhang et al. investigated the optical characteristics of gold nanorods-albumin complexes63. Their observation showed that a single nanorod with albumin has inactive circular differential scattering, whereas the dimer and trimer of gold nanorods show chiroptically activated responses, which were frequently observed in twisted structures. Furthermore, they have quantitated the contribution of transverse and longitudinal plasmonic modes in inducing plasmonic chirality in achiral geometry. Theoretical prediction for asymmetric dimer shows circular differential scattering at bonding modes of the plasmon, whereas longitudinal bonding modes in the experiment are weak. Interestingly, unexpected circular differential scattering, which was not predicted in simulations, was observed in the experiment for the achiral dimer due to the high near-field enhancement at transverse bonding mode74. The results suggested that interaction between local chirality at the gap and plasmonic near-field induces a new chiral response, which was widely known as PCCD65,71,74,75,76.

a (left) Calculated absorption and scattering spectra of gold nanorods dimer. (right) Theoretical and experimental results of circular differential scattering of homodimer (upper) and heterodimer (lower). Adapted with permission from ref. 69. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society. b (top) Schematic, SEM image, and optical chirality density of the hexagonally aligned gold helicoid nanoparticle. (bottom-left) The spectra of the hexagonally aligned gold helicoid nanoparticles with various concentrations of deionized water, L-proline, and D-proline. (bottom-right) A detection limit of the hexagonally aligned gold helicoid nanoparticles for microRNA-21, soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor complex, L-proline, and D-proline. Adapted with permission from ref. 80. Copyright 2022 Springer Nature.

The synthesis of chiral nanoparticles using the enantioselective interaction between chiral amino acids and inorganic surfaces has seen rapid development in recent times77,78,79. Differences in growth rates based on the handedness of chiral molecules at the surface of the seed lead to asymmetric structure. Nam and colleagues have used chiral gold nanoparticles for chiral sensing80. The hexagonally aligned helicoid gold chiral nanoparticles (refer to Fig. 1b (top)) create additional momentum matching conditions for the excitation of surface waves in TE and TM polarized light, resulting in the collective spinning of induced dipole moment on the helicoid gold nanoparticle. The spinning-induced dipole moment forms a unique optical chiral density (as shown in Fig. 1b (top-right)). When a chiral molecule is placed in the field, a spectral shift of the collective resonance occurs. As illustrated in Fig. 1b (bottom-left), the authors measured the spectral changes based on the concentration of proline and confirmed that there was no spectral shift in the LSPR dip located at a wavelength of 651 nm, whereas the collective resonance spectrum in the NIR region was redshifted. Consequently, they were able to confirm a detection limit of 10−4 M for D-proline. The hexagonally aligned gold helicoid nanoparticles were also used for the detection of microRNA-21 and the soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor complex. Notably, a detection limit of 114 pM was confirmed for microRNA-21, and conformational changes due to the binding of biomolecules could be monitored in the soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor complex.

Recently, high-index dielectric material-based nanostructures have gained significant attention for their ability to enhance light-matter interaction through Mie resonance81,82,83. While plasmonic nanostructures exhibit intense electric dipole and quadrupole modes84 but lack magnetic multipole modes, high-index dielectric nanostructures induce magnetic multipolar modes that enhance chiral signals85. Specifically, the strong magnetic multipolar feature induces the asymmetry between electric and magnetic multipolar modes to generate significant chirality86. In contrast to plasmonic nanostructures, Mie-resonant dielectric nanostructure has low loss, thereby avoiding thermal artifacts. For example, Quidant and coworkers reported silicon nanoresonator-based chiral sensing87. The silicon nanoresonator exhibits both electric and magnetic dipole resonance, resulting in larger CD enhancement than plasmonic nanostructure. Although Mie-resonant nanostructures present a promising field for enhancing and detecting chirality, this review does not cover them in depth.

Surface-enhanced chirality sensing

In this section, we will begin by discussing periodic plasmonic nanostructures, which are commonly designed to induce extremely localized near-field effects. Unlike individual plasmonic nanoparticles, periodicity imparts a new type of resonance. By appropriately controlling the period of a well-designed structure, the induced plasmon resonance in each structure can lead to the generation of new resonance phenomena. The combination of localized surface plasmon and periodicity results in a Fano-like sharp resonance spectrum, known as surface lattice resonance (SLR). This approach can also be found in metamaterials, where extraordinary optical phenomena are achieved through the periodic arrangements of single resonant structures. Moreover, periodic plasmonic nanostructures also exhibit surface-enhanced signal enhancement due to a significant increase in the near-field on the structure’s surface. For instance, SERS experiences a 4-fold enhancement factor due to local and radiation field enhancement, while SEIRA sees a 2-fold enhancement due to local field enhancement55,88. Hence, periodic plasmonic nanostructures have been extensively studied for their ability to enhance and detect weak signals from the target sample.

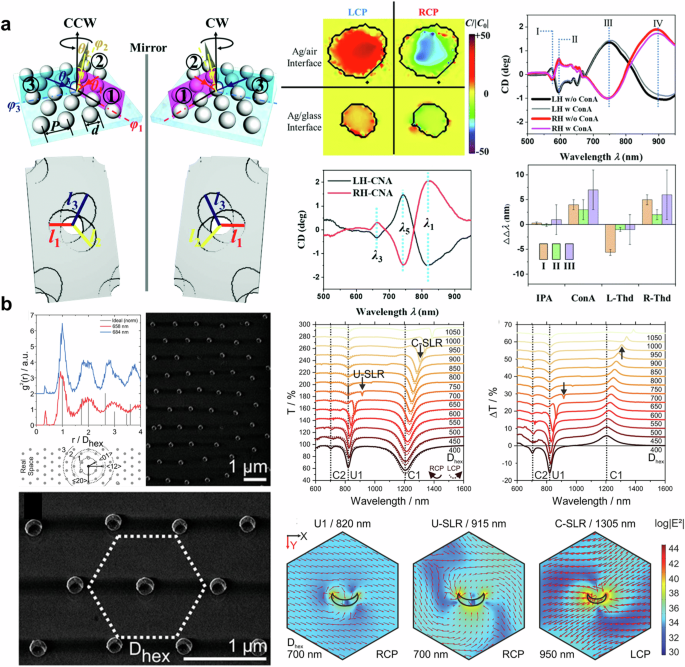

In 2012, Markovich and colleagues reported on the chiroptical response of plasmonic nanohole arrays89. Although the nanohole arrays they reported are symmetric, they exhibit a chiroptical response when subjected to oblique incidence along the radial and azimuthal directions. Compared to gammadion arrays, the sharper circular dichroism spectrum observed in these arrays indicates a combination of asymmetric surface plasmon and periodicity. Additionally, the sensing of chiral molecules via chiroptical reactions in asymmetric nanohole structures has been reported90. Ai et al. used shadow sphere lithography, a glancing angle deposition technique with a polystyrene nanosphere monolayer, to create chiral nanohole arrays by varying deposition angles in three directions as shown in Fig. 2a (left). Since the chiral nanohole array has different length diameters in three directions, it exhibits three major peaks in the CD spectrum. In particular, the second peak at the wavelength of 764 nm is close to the (1,0) Wood’s anomaly, therefore, the authors argued that the chiroptical response at 764 nm comes from localized surface plasmon resonance (See Fig. 2a (middle-bottom)) Furthermore, the local chiral density is induced at the wavelength of 764 nm as shown in Fig. 2a (middle-top). They applied their structure to detect chiral molecules, such as concanavalin A and thalidomide, at the picogram level as shown in Fig. 2a (right). Meanwhile, around the same time, research was published in which a periodic bimaterial nano crescent array was fabricated using a type of glancing angle deposition called colloid lithography91,92, and the chiral SLR phenomenon was observed. The bimetal nano crescent structures are arranged in a hexagonal periodic structure, which gives them additional periodic resonance effects (Bragg mode) due to diagonal components as well as multiples of the period, as shown in Fig. 2b (left). The nano crescent structure has a short axis (referred to as U) and a long axis (referred to as C). When light is incident parallel to the short axis, localized surface plasmon resonance is observed at a wavelength of 830 nm (U1). When light is incident parallel to the long axis, the dipole mode (1250 nm, C1) and quadruple mode (677 nm, C2) are excited. This can be verified through the transmission spectrum results for circular polarization as shown in Fig. 2b (right-top). As the size of the nano-crescent grating increases, diffraction occurs. The combination of diffraction order and localized surface plasmon gives rise to a new resonance phenomenon (SLR) in a location different from the previously mentioned resonance band. What’s interesting is that C-SLR and U-SLR have different signs for the same mirror image structure, which is expected to be applied for chiral sensing. The near-field distributions of the SLR mode exhibit a continuous twisting electric field, while the localized surface plasmon mode shows a confined electric field at the vertex as presented in Fig. 2b (right-bottom). Furthermore, 3D twisted periodic metamaterial is fabricated by nanospherical-lens lithography and holo-mask lithography, one of the glancing angle depositions, for molecular chirality sensing83.

a (left) Illustration of shadow sphere lithography. (right) Chiral density and experimental results of chiral nanohole. Adapted with permission from ref. 90. Copyright 2020 The Royal Society of Chemistry. b (left) Averaged radial distribution function according to the nearest-neighbor distance and SEM image of hexagonal crescent array. (right) Spectra and electric field distribution of hexagonally aligned nano crescent arrays. Reprinted under the terms of the Creative Commons CC-BY License from ref. 91. Copyright 2020 John Wiley and Sons.

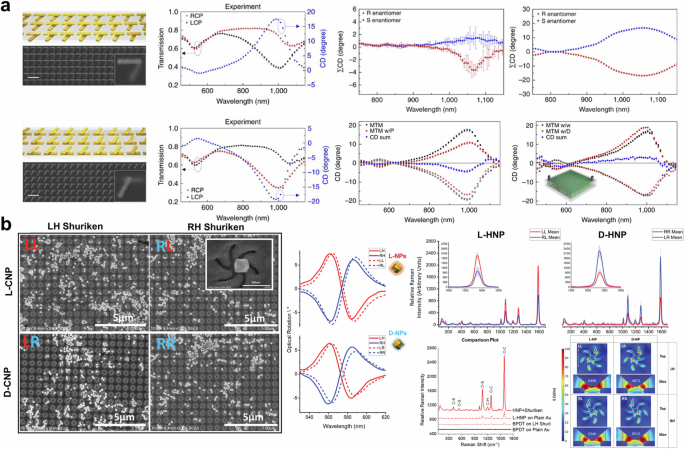

In 2017, Zhao et al. demonstrated a method for chirality detection using bi-layered twisted gold nanoorods93. Several twisted angles of nanorods were simulated, fabricated, and evaluated. Among the configurations tested, a twisted angle of 60° exhibited the largest CD (see Fig. 3a (left)) and was subsequently used to detect enantiomers. The results suggest that the near-field chiral enhancement, which is defined as the ratio of near-field chirality and far-field chirality, is more critical for detecting and distinguishing enantiomers than near-field enhancement94. Similar to ensemble measurement, which cancels out intrinsic linear dichroism, summing the measured CD can delete the intrinsic CD of nanostructures, resulting in a unique CD related to the target analytes as shown in Fig. 3a (right). The detection limit of the proposed system is as low as 55 zeptomoles, which is 1015 times lower than that of ensemble-based typical CD spectroscopy. Kartau et al. reported a “shuriken” nanohole array with chiral nanoparticles as shown in Fig. 3b (left)95. They fabricated helicoid nanoparticles and attached them to the surface of the shuriken nanohole array using biphenyl-4,4’-dithiol. The ORD spectrum before and after functionalization is presented in Fig. 3b (middle). After functionalization, all combinations exhibited broadened due to damping96 and redshifted ORD. In Fig. 3b (middle), L-cysteine-supported nanoparticles show signal augmentation, while ORD of D-cysteine-supported nanoparticles with a shuriken nanohole array decreased. The author attributed this difference to the number of attached helicoid nanoparticles and sample inhomogeneity. The mismatch between chiroptical resonant wavelength and excitation wavelength appears to be one of the reasons for the discrepancy. Nonetheless, a strong near-field is created in the gap between the shuriken structure and the helicoid nanoparticle, leading to enhanced Raman signals, as shown in Fig. 3b (right).

a (left) SEM image and transmittance of twisted bilayered nanorods array. (right) Experimental and theoretical CD spectra of enantiomers on twisted bilayered nanostructure, Concanavalin A measurement results. Reprinted under the terms of the Creative Commons CC-BY License from ref. 93. Copyright 2017 The Author(s). Published by Springer Nature. b (left) SEM image and (middle) optical rotatory dispersion of chiral nanoparticle and shuriken nanohole arrays. (right) Raman scattering results and electric distribution of shuriken nanohole arrays. Reprinted under the terms of the Creative Commons CC-BY License from ref. 95. Copyright 2023 John Wiley and Sons.

Gap-based chirality sensing

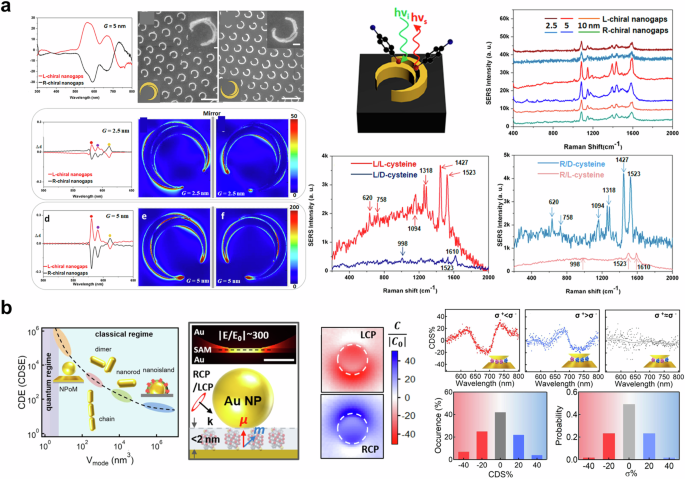

In Fig. 4a, a periodic nano crescent array with a nanogap is displayed. This structure was fabricated by Zhang and colleagues using glancing angle deposition and the nanoskiving technique97. The SEM image in Fig. 4a (top left) shows the nano crescent array with gap sizes of 2.5 nm and 5 nm. The CD spectra of the nano crescent array with a 5 nm gap display distinct peaks and dips at wavelengths over 500 nm. Additionally, the absorption difference and near-field enhancement at the 5 nm gap nano crescent, as a result of Landau damping98, are found to be greater than those at the 2.5 nm gap nano crescent. This makes the 5 nm gap nano crescent suitable for enhancing SERS signals. Furthermore, the right-handed nanocrescent strongly enhances the signal of D-cysteine, while L-cysteine is not significantly enhanced, and vice versa. This demonstrates the strong coupling of chiral molecules with chiral nano crescents, indicating that chiral nano crescents with a nanogap can be used to identify and distinguish enantiomers of chiral molecules without the need for chiral labels or circular polarization. Figure 4b exhibits the results of chirality detection using NPoM64, which has been widely utilized in the recent nanophotonic field63,99. Nanoparticles on a mirror system generate highly localized near-fields at the gap, which are challenging to achieve through rod100, dimer101, chain14, and nanoisland101. The near-field enhancement of 300 was calculated at the gap, and the volume of localized light was estimated to be 37 nm3, containing approximately four or more helices. By utilizing the extremely squeezed light, the local chiral density within racemates was measured as presented in Fig. 4b. Although the racemic mixture exhibits an achiral response, the sufficiently improved sensitivity enabled the detection of chirality induced by local enantiomer excess. In addition, the authors employed a quantum-correlated model102 to assess the contribution of quantum tunneling on circular differential scattering enhancement. Furthermore, plasmon-based approaches, including particle, surface, and gap are widely applied to SERS with amino-acid-driven chiral nanoparticle103, chiral nano helices104,105, and chiral molecular imprinting106. In summary, the plasmon-enhanced mechanism offers a promising unachievable sensitivity up to tens of zeptomole93 for chiral sensing. The near-field enhancement at extremely narrow gaps, such as nanocrscent97, dimer63, and NPoM64, allows to detect local chirality arising from local enantiomer excess. These plasmon-based chiral sensing technologies can be combined with recently reported CPL emission metasurfaces107,108,109,110 to develop compact-size chiral sensors.

a (left-top-left) CD spectra of nano crescent array with a gap size of 5 nm. (left-top-center, right) SEM image of nano crescent with the nanogap size of 2.5 nm and 5 nm. (left-middle, bottom) Calculated absorption difference and electric distribution of nano crescent with the nanogap size of 2.5 nm and 5 nm. (right) Experimental results of Raman spectrum. Adapted with permission from ref. 97 b Circular differential scattering enhancement versus light mode volume (left), the optical response of gold nanoparticles on the mirror system (middle), circular differential scattering spectrum of the racemate (right-top), and probability of enantiomeric excess (right-bottom). Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons CC By License from ref. 64. Copyright 2024 The Author(s). Published by Springer Nature.

Tip-enhanced chirality sensing and imaging

Tip-enhanced measurement techniques represent a transformative advancement in the field of microscopy and spectroscopy, enabling unprecedented spatial resolution and sensitivity that surpass the traditional diffraction limit of light33. These methodologies leverage the unique properties of sharp tips to enhance local electromagnetic fields and facilitate nanoscale investigations111. The traditional limitations of optical microscopy, governed by the diffraction limit, impose constraints on the resolution achievable in imaging and spectroscopic analysis, prompting the development of advanced light-matter interaction techniques to overcome these barriers. Tip-enhanced techniques capitalized on the dipole interaction, lightning rods effect, and localized surface plasmon, where the interaction of light with a sharp tip induces a confined electromagnetic field, thereby amplifying the signal from the sample32,33,34,112,113. This enhancement facilitates the detection of subtle spectroscopic features and structural details that would otherwise be elusive. Similar to plasmon-enhanced chirality detection, tip-enhanced chirality detection is based on light-matter interaction to enhance the optical response of a chiral molecule. The main difference between plasmon-enhanced and tip-enhanced chirality detection lies in the ability to perform measurements at a targeted location. Tip-enhanced measurement offers the advantage of obtaining information at a specific target by positioning the tip at the observation position. Furthermore, a tip located in the vicinity of the near-field can indirectly measure the near-field by detecting the scattered field strongly enhanced by the tip apex (apertureless-type, scattering-type)112,114,115,116, or directly measure the near-field by capturing the photoelectric signals coupled to the aperture through fiber optics (aperture-type, collection-type)117,118,119. In addition, tips endowed with chiral properties can distinguish enantiomers and their interaction120,121,122. In this section, we describe several examples of chirality detection and visualization of chiral optical fields using tip-enhanced measurement techniques.

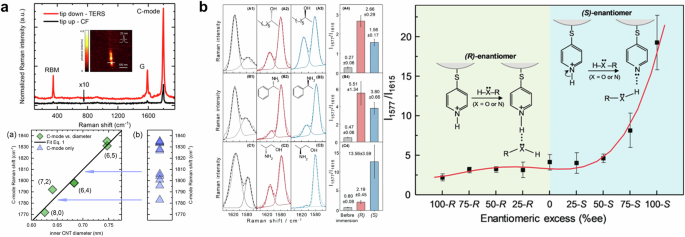

Chirality changes in a single-wall carbon nanotube were reported by the acquisition of spatial distribution of changes in the resonant frequency of the radial breathing mode using near-field Raman spectroscopy123. This approach has been developed to visualize a tip-enhanced Raman scattering image of a linear carbon chain124. The presence of a linear carbon chain was observed by carbyne Raman mode (C-mode), which is related to bond-length changes in the chain. The radial breathing mode, associated with chirality-specific Raman features, and C-mode are invisible without tip-enhanced measurement as shown in Fig. 5a (top). To reveal a linear carbon chain in the double-wall carbon nanotube, a tip-enhanced Raman scattering image was obtained as presented in Fig. 5a (top-inset). The authors observed 14 different chain nanotubes with the radial breathing mode, indicating chirality from a radial displacement of the carbon atoms, and C-mode, a longitudinal optical phonon. As shown in Fig. 5a (bottom), C-mode Raman scattering was dependent on the diameter of the carbon nanotube, whereas it had no dependency on the length of the carbon chain. The findings suggest that the C-mode Raman shift decreases linearly with the reduction in the nanotube’s diameter, implying that the primary interaction between the nanotube and the carbon chain is van der Waals force.

a Tip-enhanced Raman scattering spectra (top) and correlation plot with carbon nanotube diameter and Raman shift (bottom). Adapted with permission from ref. 124. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society. b (left) Tip-enhanced Raman scattering spectra of chemically modified silver tip with enantiomers. (right) The relation between enantiomeric excess and the ratio of Raman scattering signal at the peaks. Reprinted with permission from ref. 120. Copyright 2020 John Wiley and Sons.

Figure 5b shows the results of discriminating enantiomers using chemically modified tip-enhanced Raman scattering. They utilized para-Mercaptopyridine to modify the surface of a silver-tip, where the interaction between para-Mercaptopyridine and chiral molecules induces a charge-transfer transition measurable by tip-enhances Raman scattering. In addition, a chemically modified silver tip offers an amplified asymmetric electric field, proving invaluable in distinguishing between two enantiomers. The ratio between tip-enhanced Raman scattering at 1577 cm−1 (right peak) and 1615 cm−1 (left peak) was used as an indicator to evaluate enantiomer discrimination. As presented in Fig. 5b (left), the ratio dramatically changed after immersing enantiomer solutions, including 2-octanol, α-methylbenzylamine, and 2-amino-1-propanol. With the presence of hydrogen bonding groups, the ability to quantitate the 2-amino-1-propanol enantiomers is attributed to the greater asymmetric near-field effect from multimer complexes near the tip. They also provided the ratio changes with regard to the enantiomeric excess of 2-amino-1-propanol as shown in Fig. 5b (right).

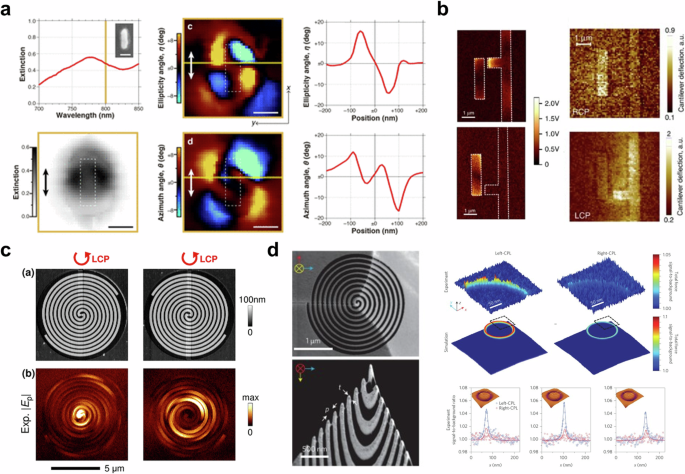

Meanwhile, despite concerns about the limited effectiveness of the superchiral optical field10,85, which means the light has much larger chiral asymmetry than the asymmetry of circular polarization, it is widely investigated to enhance optical enantioselectivity for detecting chiral molecules7,8,9,125,126,127. In the early days of the superchiral field, it was believed that only chiral nanostructure8 or the combination of imperfect standing waves9 could generate a superchiral field. However, it has been discovered that even achiral nanostructure may induce optical chirality without any chiral molecules11,128,129,130. To elucidate superchiral near-fields and their interaction with nanostructures and chiral molecules, it is necessary to visualize the local optical fields. Figure 6a shows the near-field polarimetric imaging of a gold nanorectangle128. The tip of aperture-type near-field scanning optical microscopy was used as a light source to excite optical chirality. Their experiments observed a local circularly polarized field at the corners of a nano rectangle with strong local chirality as shown in Fig. 6a. The circularly polarized light on the achiral gold nanostructure is excited by the dipolar plasmon mode131,132. In addition, planar asymmetric nanostructures were investigated to enhance CD in mid-infrared region133,134. Although the proposed linearly asymmetric feature of the orthogonally elongated rods may exhibit more pronounced characteristics under linearly polarized light, it also shows unusual differences induced by circularly polarized light135. Namely, CD can be observed in an orthogonally aligned nanostructure, caused by phase retardance at resonance. Khanikaev et al. argued that the origin of CD in 2D nanostructure is ohmic heating133. The proposed structure consists of an asymmetric arrangement of monopole and dipole antennas with grounded wire for the monopole antennas. Without ohmic heating, CD cannot be shown in orthogonally aligned nanostructure while the near-field distributions are different. Because the transmission conversion efficiency in the absence of ohmic loss for each circular polarization is equal, resulting in identical light absorption for each circular polarization. The theoretical prediction with both monopole and dipole theory of plasmonic nanoantenna has been verified by tip-based measurement as shown in Figure 6b133. The spiral-shaped nanostructure makes it possible to generate a chiral near-field depending on its rotating direction122,134,136. The charge distribution along a spiral-shaped structure may induce an extraordinary chiroptical response137. Scattering-type near-field scanning optical microscopy has measured a chiral near-field hot spot on a spiral-shaped nanostructure as shown in Figure 6c134. The left-handed circularly polarized light excites the focused near-field hot spot at the center of a spiral antenna while right-handed circularly polarized light does not. In their study, it was discovered that the monopole antenna only responds to left-handed circularly polarized light, while the dipole antenna exhibits a robust resonant effect for both circularly polarized light.

a Near-field polarimetric imaging results. Reprinted with permission from ref. 128. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society. b Scattering-type near-field scanning optical microscopy (left) and AFM-IR image of planar-chiral nanostructure. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY License from ref. 133. Copyright 2016 The Author(s). Published by Springer Nature. c Topography and near-field distribution of the spiral-shaped antenna. Reprinted with permission from ref. 134. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society. d SEM image of a chiral tip (left) and experimental and simulation results of enantioselective optical force (right). Adapted with permission from ref. 122. Copyright 2017 Springer Nature.

Enantioselective optical force, which is induced by chiral light-matter interaction, can be used for molecular trapping138,139, and sorting140,141, which enables us to separate chiral molecules142,143,144. Even though tip-based measurement techniques enable us to measure local optical forces including photothermal, optical gradient, optical scattering, and photoacoustic force145,146,147,148, detecting enantioselective optical forces is challenging due to their extremely weak intensity149. One interesting approach to detecting enantioselective optical forces with tip-based measurement is using a spiral-shaped tip to enhance chiroptical forces122. Zhao et al. implemented a spiral-shaped atomic force microscopy probe (see Fig. 6d (left)) with a plasmonic optical tweezer138 to amplify and visualize enantioselective optical forces. In their study, the researchers utilized focused ion beam milling to fabricate a spiral-shaped gold-coated silicon tip and coaxial nano-aperture, which was instrumental in producing enantioselective optical force. First, they measured the optical response of the achiral tip (a typical AFM tip) to evaluate the strengthened optical force from coaxial nano-aperture, which is formed by a concentric bull’s eye grating. The impact of a chiral tip (spiral-shaped tip) on circularly polarized illumination was compared with the response of an achiral tip. Significant differences between the chiral and achiral tips were observed with both left- and right-handed circularly polarized light. With the achiral tip, there was little difference in the force depending on each circular polarization. However, with the chiral tip, which was designed for a left-handed spiral shape, a greater force was measured in left-handed circular polarization than in right-handed circular polarization. Furthermore, the spatial distribution of enantioselective optical force was also obtained with 2 nm as shown in Fig. 6d (right).

Tip-enhanced measurement techniques have revolutionized microscopy and spectroscopy by achieving spatial resolution and sensitivity beyond the diffraction limit of light. These methods utilize sharp tips to enhance local electromagnetic fields, enabling detailed nanoscale investigations and detection of subtle spectroscopic features. Tip-enhanced Raman scattering, in particular, has proven effective in visualizing molecular chirality and distinguishing enantiomers through chemically modified tips. Additionally, advancements such as spiral-shaped tips have facilitated the measurement of enantioselective optical forces, enhancing the study of chiral interactions at the nanoscale.

Chiral optical cavity

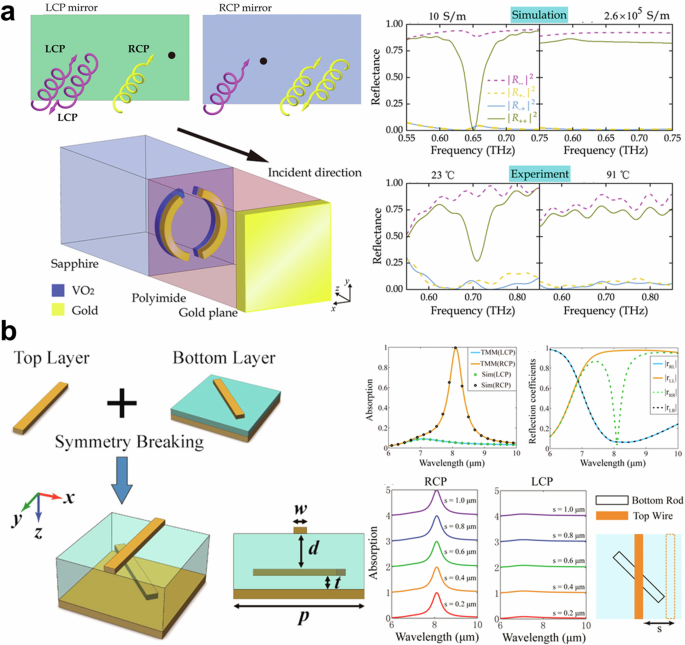

Mirrors are essential optical components used to reflect images of objects. When light is incident on a mirror, it behaves like a wave traveling from a sparse to a dense medium. As a result, the reflected light has its phase and polarization reversed when it emits from the mirror surface. This means that reflected circularly polarized light has the opposite polarization of the incoming light. Meanwhile, circular polarization of light has significant interactions with chiral molecules and artificially designed chiral nanostructures. The strong light-matter interaction has been widely applied to create polaritons that are used for sensing37,50,71. Likewise, the interaction between circularly polarized light and chiral molecules is expected to create chiral polariton150,151,152,153. To enhance and select specific circular polarization, there is a growing need for mirrors that do not change the polarization of incident light154. Different types of mirrors are being considered to address this need, such as handedness-preserving mirrors, perfect absorbers, and chiral mirrors (right- and left-handed circularly polarized mirrors)155,156 as depicted in Fig. 7a (left-top). Chiral optical cavities can generate chirality-preserved light sources and manipulate the chiroptical response of chiral molecules, enhancing chirality detection methods154,157. For these reasons, several researchers have focused on the design methods and potential applications of chiral optical cavities, including chiral mirrors.

a (left-top) Schematic of chiral mirror. Schematic (left-bottom) and experimental results (right) of split-ring based chiral mirrors. Adapted with permission from ref. 155. Copyright 2020 John Wiley and Sons. b (left) Schematic of twisted rods-based chiral mirror. (right-top) Transfer matrix and fullwave simulation results. (right-bottom) The absorption spectrum with regard to a lateral offset between twisted rods. Adapted with permission from ref. 158. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

The simplest idea for implementing a handedness-preserving mirror for circular polarizations is a combination of a quarter-wave plate and a conventional mirror. Circularly polarized light that passes through the quarter-wave plate is converted to linearly polarized light, which is then reflected from the mirror. Since the polarization of the reflected light remains in same plane (e.g., x-polarization to x-polarization) with a phase difference of π, the original circular polarization is restored through the quarter-wave plate. Selective handedness preserving mirrors, also known as chiral mirrors, have been designed using symmetry-breaking methods, for example, 2-dimensional split ring155,156, twisted nanorods158, and anisotropic fish-scale159. As shown in Fig. 7a (left-bottom), a chiral mirror was implemented using gold and VO2 split rings with symmetry-breaking155. Similar to the role of the quarter-wave plate, the presence of 2-dimensional 2D split rings placed in front of the conventional mirror reflects right-handedness (left-handedness) circular polarized light according to the split side of the rings. Despite the size of the split rings, the operating frequency is in the microwave region. Furthermore, VO2, a temperature-dependent phase transition material, was utilized to switch the type of chiral mirror. In 2016, Wang et al. reported the design of chiral mirror with near-perfect extinction using twisted gold rods combined with a metallic reflector158 as presented in Fig. 7b (left). The mirror and the rotational symmetry were broken by twisting the rods at a 45° angle. The symmetry breaking induces CD, resulting in 94.7% reflection of left-handed circularly polarized light while 99.3% of right-handed circularly polarized light is absorbed at a wavelength of 8.1 μm as shown in Fig. 7b (right-top). The results were reproduced by both the transfer-matrix method and full-wave numerical simulations. Furthermore, due to the weak-coupling regime, the characteristics of metamirror are maintained at a lateral offset of 1 μm as shown in Fig. 7b (right-bottom).

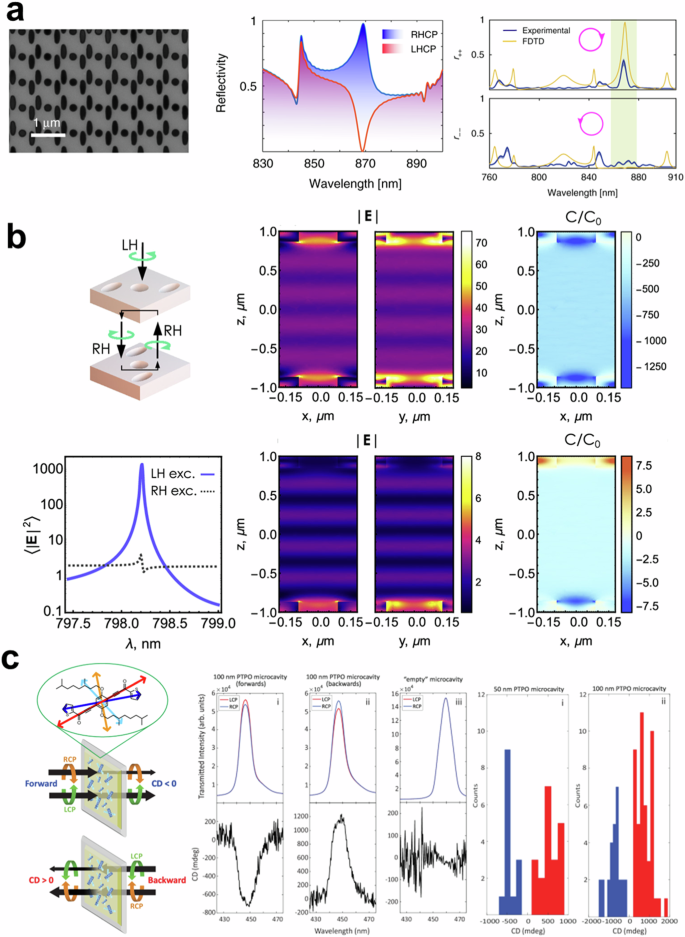

Semnani and coworkers implemented a chiral mirror without symmetry-breaking160. Interestingly, the proposed chiral mirror, formed by elliptical and circular holes in silicon nitride film, shows point symmetry, whereas previous chiral structures aimed to break symmetry. The principle of this chiral mirror is guided-mode resonance by Bloch modes in a photonic crystal161. The designed photonic crystal with the incident light excites magnetic dipole moments to induce intrinsic chirality. As shown in Fig. 8a, the reflection spectrum of the chiral mirror shows a near-perfect response at the wavelength of 870 nm, where TE and TM modes are hybridized, resulting in the excitation of electromagnetic dipole moments5. Using this structure, the Baranov group numerically calculated a handedness-selective chiral cavity as presented in Figure 8b162. The designed chiral mirrors are positioned at equal intervals in opposite directions to form a Fabry-Perot cavity. The region inside the cavity maintains a constant chirality, demonstrating the potential to generate chiral polaritons, which are interactions between chirality and matter150,151.

a SEM image (left), numerical (center), and experimental reflection spectrum (right) of a spin-preserving chiral mirror. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY License from ref. 160. Copyright 2020 The Author(s). Published by Springer Nature. b Fullwave simulation results of single-handedness chiral optical cavity. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY License by ref. 162. Copyright 2022 The Author(s). Published by American Chemical Society. c Schematic and experimental results of Fabry-Perot cavity with apparent circular dichroism. Reprinted under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY License from ref. 152. Copyright 2024 The Author(s). Published by Springer Nature.

Furthermore, there have been works to make chiral optical cavities without chiral mirrors, which are hard to design and fabricate. Yuan et al., suggested a chiral laser using stimulated chiral light-matter interaction in dielectric mirror-based Fabry-Perot cavity163. They used green fluorescent protein and rhodamine-B as a gain medium and reported enhanced lasing dissymmetric factors. The idea of placing chiral materials inside a Fabry-Perot cavity evolved as follows. Genet and coworkers have designed a chiral optical cavity by positioning a polystyrene layer between two metallic mirrors164. The torsional shear stress endows the polystyrene layer with chirality. Due to the torsional sheared polystyrene film, the cavity interacts with oblique illumination. In an analogous approach, Tempelaar, Goldsmith, and coworkers investigated Fabry-Perot cavities with an organic film165, which shows apparent circular dichroism. Unlike conventional CD, apparent circular dichroism arises from the interference between linear birefringence and linear dichroism of a sample166. The researchers have explored 2D chiral polariton theoretically using achiral Fabry-Perot cavity with an apparent circular dichroism153. Furthermore, the experimentally implanted chiral optical cavity has verified asymmetric transmission, which is a different transmission regarding the polarization and direction of illumination as shown in Fig. 8c152. The apparent circular dichroism from phenylene bis-thiophenylpropynone (PTPO) film shows asymmetric transmission by itself. The PTPO film is embedded in a Fabry–Perot microcavity. The cavity allows light to bounce back and forth multiple times, increasing the interaction path between the light and the film. It amplifies the ACD effect, enhancing the asymmetric transmission of LCP and RCP light as shown in Figure 8c.

In summary, the development of chiral optical cavities is an emerging area driven by advancements in spin-preserving mirrors. Recent progress includes the use of chiral optical cavities to improve chirality detection and the creation of chiral mirrors using symmetry-breaking methods and guided-mode resonance, which have shown promising results in the selective reflection and absorption of circularly polarized light.

Photothermal approaches

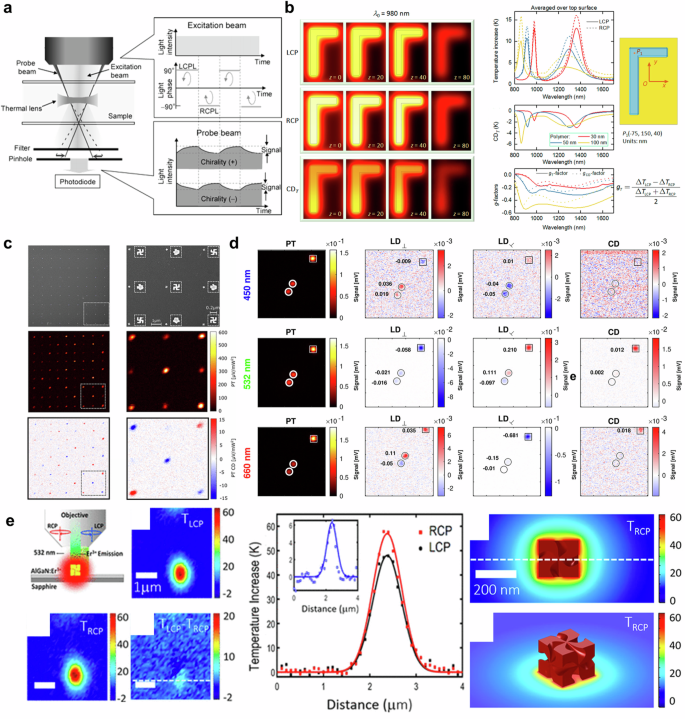

Temperature is an indicator of the energy possessed by a substance. Therefore, it is evident that the temperature of a substance will increase as it absorbs more energy through light. From a classical perspective, an increase in temperature causes the atoms of a substance to move further apart, leading to thermal expansion and a reduction in density. The lower density allows light to pass through the substance more quickly, resulting in a lower refractive index. Since changes in refractive index are temperature-dependent, the thermal lens effect can be achieved by generating a local temperature distribution167,168. Photothermal microscopy, which utilizes the thermal lens effect, has been developed to detect and visualize light absorption in various media169,170. This technique employs two light sources: a heating beam (pump beam) to induce the thermal lens effect, and a probe beam to detect changes in optical properties caused by the thermal lens effect. To identify chiroptical response, photothermal microscopy utilizes photothermal circular dichroism (PTCD), which is defined as the difference between temperature increment induced by left and right-handed circularly polarized light as below15,20.

The chiral nanostructure absorbs light differently depending on the polarization of the incident light, leading to variations in temperature rise and enabling polarization-sensitive signal detection. Unlike conventional CD measurement, this method allows for the detection of single nanostructures by identifying temperature changes in each nanostructure. In 2006, the Kitamori group first reported CD thermal lens spectroscopy based on the idea of using periodic polarization manipulation of excitation beam to detect polarization-sensitive photothermal signals on microchips as shown in Figure 9a171. This approach successfully measured the concentration difference between the enantiomers of tris(ethylenediamine)cobalt(III) [Co-(en)3]3+ without the need for separation of the aqueous solution. However, it was limited by its non-scanning methodology and insufficient sensitivity, which prevented the visualization of molecule distribution. Despite its significance as a pioneering work in reporting a photothermal approach to detecting chirality172, it did not attract much attention.

a Schematic of CD thermal lens microscopy (photothermal microscopy). Reprinted with permission from ref. 171. Copyright 2006 American Chemical Society. b Photothermal response of gamma-shape nanostructures under left- and right-handed circularly polarized light. Adapted with permission from ref. 15. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society. c SEM (top), Photothermal (middle), and PTCD image of nanogammadia arrays. Reprinted under the terms of CC-BY-NC-ND License from ref. 16. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society. d Photothermal, linear-dichroism, and circular-dichroism image of nanoparticles. Reprinted under the terms of CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 License from ref. 18. Copyright 2021 The Author(s). e Temperature distribution (left) and profile (right) of gold nanoparticle helicoid. Adapted with permission from ref. 17. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

In 2018, Govorov and coworkers reported an asymmetric chiral plasmonic absorber using numerical analysis15. They defined PTCD as in Eq. (3) and numerically calculated the temperature increment of a gamma-shaped plasmonic nanostructure under circularly polarized incident light. The gamma-shaped plasmonic nanostructure consists of orthogonally aligned silver nanorods, with a height of 40 nm, width of 50 nm, and length of 200 nm and 350 nm respectively. As a result, it absorbs light energy from left- and right-handed circularly polarized light differently. The spatial distribution of photo-induced temperature increment with different circularly polarized light at a wavelength of 980 nm is presented in Fig. 9b (left). The illumination wavelength was selected as the plasmonic resonant frequency, corresponding to the coupled mode of the orthogonally aligned nanorods. The work demonstrates that CD and the g-factor exhibit large values at the plasmonic resonant frequency due to plasmonic resonance induced by multipolar excitation. The temperature distribution was taken at t = 8 ns and different vertical planes of z = 0, 20, 40, and 80 nm. The thermal conductivity of the metal is high enough for all photo-induced heat to diffuse inside the metal within 8 ns, resulting in a uniform temperature distribution. The thermal g-factor, which is defined with temperature (Eq. (4)), exhibits a larger value than the traditional g-factor with broader spectral features due to heat diffusion as depicted in Fig. 9b (right). Although the results showed the potential to utilize the chiral plasmonic absorbers for inducing a giant CD effect, the study has limitations as it was a computational study and used short pulsed illumination instead of continuous wave illumination173, which is more commonly used in experiments. In addition, the temperature-induced nonlinearity was not considered59,174.

The idea of utilizing photothermal response as an indicator of CD has been realized with a photothermal imaging system to visualize the PTCD of nanoparticles16. The Orrit group combined an electro-optical modulator and quarter-wave plate to modulate the polarization of the heating beam between left- and right-handed circular polarization. To investigate PTCD, gold gammadion nanostructures, formed of four gamma-shape nanostructures and widely used for chirality detection8,13, were fabricated on a glass substrate as shown in Fig. 9c (Top). The gammadion nanostructures exhibit CD depending on the rotating direction of the gamma-shape nanostructures. Furthermore, the structures eliminate the linear dichroism due to their four-fold symmetry, which cancels out symmetric components. The photothermal image of the gammadion nanostructure arrays shows different response intensities with regard to the handedness of the gammadion nanostructures as presented in Fig. 9c (middle). Figure 9c (bottom) shows the photothermal dichroism image obtained by subtracting two photothermal images excited by two circular-polarized illuminations. The results indicate that achiral nanostructure had no PTCD while right- and left-handed gammadion showed opposite signals. The work successfully distinguished the asymmetric nanostructures with PTCD and reported improved sensitivity of chirality measurements for the detection limit for the dissymmetric factor gT of 0.004. However, nanostructures also exhibit linear dichroism which can strongly influence photothermal response more than CD. In contrast to ensemble CD measurement, individual plasmonic nanoparticles may cause crosstalk between linear and CD due to their high linear dichroism. To avoid crosstalk in PTCD measurement using photothermal microscopy, Spaeth et al. have implemented a dual modulation system of the heating beam by using a combination of a photoelastic modulator and an electro-optical modulator18. This approach shifts the CD signal by quarter-wave plate to the sum and difference of modulator frequencies. On the other hand, a circular birefringent plate shifts linear dichroism signals to the desired lock-in frequency. Therefore, they could differentiate linear dichroism and CD of an individual nanoparticle as shown in Fig. 9d. The methodology has been applied to investigate magnetic CD175,176 and morphological chiral features with electron tomography19. While this method promises the sensitive measurement of an individual nanostructure, it may be challenging to obtain an accurate photothermal signal if the temperature distribution is similar due to environmental and structural characteristics, even if the thermal responses are different. Furthermore, heat dissipation within the surrounding medium makes it difficult to distinguish between two adjacent nanostructures.

The Richardson group reported PTCD measurement based on Er3+ photoluminescence emission17. Since the intensity and spectrum of Er3+ photoluminescence depend on temperature, the temperature can be extracted by analyzing the emission band of photoluminescence with careful calibration177. As presented in Fig. 9e, the authors have investigated the PTCD of gold nanoparticle helicoids. The temperature difference of 6 K between two circularly polarized illuminations was observed. The findings show that the chirality of a single gold helicoid is three times larger than the ensemble measurement. Recently, photothermal effects on asymmetric photothermal switching20 and photothermal effect-based chiral molecule sensing in aqueous solution have been reported178,179.

Overall, photothermal approaches offer a simple mechanism for chirality detection. One of the significant advantages of photothermal approaches is acquiring spatial distribution of the chirality with high temperature sensitivity (~0.1 K)180. The photothermal response can be controlled by manipulating the conditions of the heating beam, such as polarization, power of incident light, and wavelength59. Therefore, it is expected to be utilized for controlling chiroptical chemical or biological reactions via light-induced temperature in various pharmaceutical and biological fields. However, it requires an environment with a high thermo-optic coefficient, which is the rate of change in refractive index with the temperature, to detect photothermal response, and distinguishing between two adjacent absorbers can be challenging due to heat dissipation. Namely, the nanoparticles/structures that serve as heat sources must be sufficiently far apart from each other.

Table 1 provides a comprehensive insight into nanophotonic approaches for chirality detection. These approaches include nanoparticle resonator-based, surface-enhanced, tip-enhanced, and photothermal effect-based technologies. The variety of the samples, including single plasmonic nanoparticles, chiral molecules in solution, monolayer of chiral molecules, and carbon nanotubes, are underlined to showcase the versatility of nanophotonic methods. Many approaches could achieve notable sensitivities, reaching tens of zeptomole and single-particle detection levels. The table also highlights remarkable detectable g-factors, detection limits, and enantiomeric excess achieved in these methods, providing insight into how the optimization of nanostructures can extensively enhance chiral interactions.

Biomedical applications

As a reminder, chirality, or handedness, plays a significant role in biological reactions. For instance, the well-known chiral molecule thalidomide shows different effects depending on its enantiomers: R-thalidomide is effective for morning sickness in pregnant women, while S-thalidomide suppresses angiogenesis181,182. This underscores the importance of detecting and distinguishing enantiomers, particularly in bio-industries such as the pharmaceutical sector. Chirality detection in biomedical applications using nanophotonics has shown great promise in improving the sensitivity of detection methods. Nanophotonics has shown promise in improving the sensitivity of chiral molecule detection in biomedical applications, particularly for biomolecules like proteins, amino acids, and DNA. Nanophotonics focuses on enhancing the sensitivity of chirality detection, which is crucial for reliable detection even with limited sample volumes. This capability is especially valuable in scenarios where sample availability is restricted or when rapid on-site analysis is required.

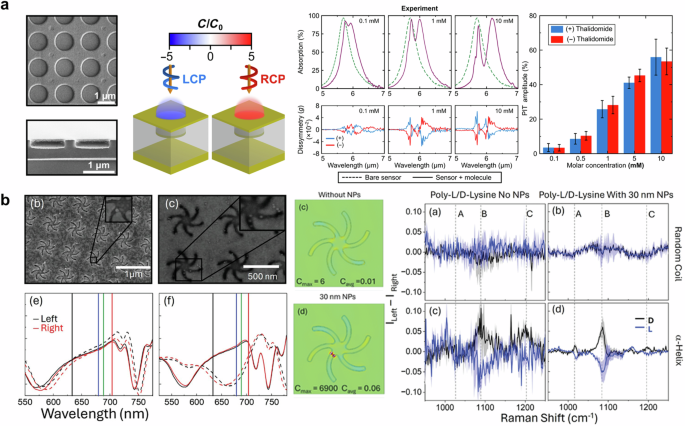

In this section, we focus on the recent advances in chiral sensing based on nanophotonic approaches. Chanda and his colleagues reported using an achiral plasmonic cavity structure to enhance VCD signals, enabling them to distinguish the handedness of thalidomide183. As illustrated in Fig. 10a (first and second), the achiral plasmonic cavity coupled with circularly polarized excitation provides consistent chiral density enhancement, maximizing the interaction with molecules. This interaction manifests as plasmon-induced transparency184,185. Since plasmon-induced transparency results from the destructive interference of plasmon mode and dipolar mode, its amplitude increases with molar concentration. The dip in absorption shows plasmon-induced transparency as depicted in Fig. 10a (third). The authors assessed the concentration and enantiomeric excess of thalidomide using plasmon-induced transparency amplitude, demonstrating a detection limit of 50 μM for molar concentration (See Fig. 10a (fourth)). Their system achieved a 13 order of magnitude increase in detection sensitivity compared to conventional VCD techniques.

a SEM image (first) and density of chirality simulation results (second) of plasmonic cavity. Absorption (third) and Plasmon-induced transparency (fourth) results with regard to molecular concentration. Adapted under the terms of Creative Commons CC-BY-NC License from ref. 183. Copyright 2024 The American Association for the Advancement of Science. b (first) SEM image and reflectance of shuriken chiral nanostructures with nanoparticles. (second) Comparison of simulated results for an optical chirality of shuriken without and with nanoparticle. (third) Experimentally acquired Raman spectra. Adapted under the terms of Creative Commons CC BY License from ref. 186. Copyright 2024 The Author(s). Small Published by Wiley-VCH GmbH.

Figure 10b shows the use of plasmonic “shurikens” nanostructures to enhance Raman signals for the detection of chiral molecules186. Although previous studies have employed shuriken structures for chiral sensing, the study incorporated nanoparticles to further enhance the signal. The SEM images of incorporated nanoparticles on shuriken nanocavity can be found in Fig. 10b (first), along with significant changes in reflectance according to the size of nanoparticles (left: 30 nm, right: 20 nm). The authors confirmed the extremely enhanced optical chirality using optical simulations, resulting in the maximum optical chirality of 6900 as presented in Fig. 10b (second). While the local chirality enhancement appears quite dramatic, authors noted that it led to only a small increase in signal. However, the presence of nanoparticles provides a high signal-to-noise ratio for Raman scattering signals of poly-L/D-lysine as depicted in Fig. 10b (third). Furthermore, plasmonic “shurikens” nanostructure can excite plasmonic circularly polarized luminescence (PCPL). Tabouillot et al. investigated the use of PCPL to detect chiral responses from peptides at the monolayer level, which are not visible through traditional light scattering methods187. By leveraging near-field effects, PCPL demonstrated enhanced sensitivity for small biomolecules, surpassing the capabilities of far-field techniques. This method holds significant potential for applications in nanometrology and point-of-care diagnostics, where detecting low concentrations of biomolecules with high precision is critical.

Beyond the examples presented in this section, several other biomedical applications using nanophotonics for chirality detection have been explored. For instance, Lee et al. utilized nanoparticles on a mirror system to enhance Raman optical activities188. The nanoparticles on a mirror system localize a strong electromagnetic field at the narrow gap, effectively eliminating unexpected ECD and Raman optical activity signals. In 2021, Liu et al. developed plasmonic moiré chiral metamaterials to generate superchiral field and photothermal-induced microbubbles simultaneously189. The convection flow induced by the microbubbles trapped target molecules in the near-field region, leading to enhanced signals. The detection limit for glucose was reported as 100 pM. Based on recent advancements, label-free SERS platforms have been created to detect biomarkers for neurodegenerative diseases. For example, Wang et al. used chiral plasmonic triangular nano-rings to detect amyloid-β proteins associated with Alzheimer’s disease with high sensitivity, down to picogram quantities190. These nano-rings make use of the SERS-chiral anisotropy effect, providing a strong optical response with significant selectivity over both fibrils and amyloid-β monomers. This approach has the potential to expand traditional applications in monitoring protein misfolding and aggregation, which are crucial processes in diseases like Huntington’s and Parkinson’s. Furthermore, several self-assembly nanoparticles and clusters have been widely investigated and developed in the chemistry field191. Chiral nanoparticles can be easily synthesized using chiral biomolecules like cysteine, DNA, and glutathione. These nanoparticles, which possess structural chirality, have attracted significant attention due to their high chirality. Unlike technologies based on nanostructures on substrates, these chiral nanoparticles can be injected into living organisms and used for applications such as photothermal therapy192. Meng et al. reported an ultrasensitive microRNA detection method in living cells using a DNA-driven two-layer core-satellite gold nanostructure that is constructed by various radii of gold nanoparticles193. Their approach utilizes a dual-signal method that leverages enhanced signal amplification and selectivity from both CD and SERS. The detection limit of 0.0051 amol/ngRNA was reported. This method enables dynamic, real-time monitoring of biomolecules in situ, providing a versatile platform for detecting microRNA in oncological investigations.

Conclusion and outlook

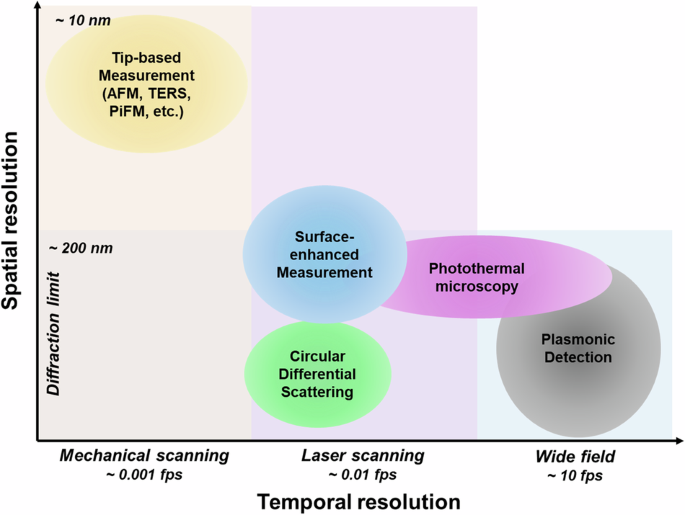

In summary, chirality detection based on nanophotonics has been extensively explored due to its ability to enhance signals through highly localized electromagnetic field, strong near-field enhancement, polarization-selective light absorption, and sensitive response to the surrounding media. The sensitivity of chiral molecules has been improved up to the zeptomole scale93. In contrast to traditional chiral sensors, such as chromatography and nuclear magnetic resonance, nanophotonic approaches allow us to visualize the distribution of chirality. Figure 11 illustrates the temporal and spatial resolution of imaging techniques based on nanophotonics. The spatial resolution of tip-based measurements is typically determined by the tip size, usually ranging from 10 nm to 100 nm. Despite having spatial resolution beyond the diffraction limit, these measurements rely on mechanical scanning to capture images, resulting in typical image acquisition times that can vary from several minutes122 to hours194. Raman imaging requires integration time to accumulate weak signals from the sample. While surface-enhanced techniques enhance Raman scattering signals, real-time wide-field imaging is challenging195. Consequently, point or line scanning methods are often employed to excite and acquire Raman scattering signals with image acquisition times of up to 1 frame per minute196. Similarly, circular differential scattering spectroscopy takes 108 s to collect a hyperspectral image with a 60-second equilibration time197. Photothermal microscopy also relies on laser scanning methods, leading to an image acquisition time of several seconds, which is longer than wide-field imaging170.

Temporal and spatial resolution of nanophotonic methods for chirality detection.

In this review, we have explored various nanophotonic strategies for enhancing and detecting chirality, including nanoparticle resonator-based, surface-enhanced, gap-enhanced, tip-enhanced, chiral optical cavities, and photothermal approaches. Since these mechanisms are fundamentally linked to light-matter interaction, particularly through induced near fields, it is challenging to distinguish their individual effects as listed in Table 2. The concept of near-field enhancement, which refers to the ratio of electric-field intensity, is commonly used to explain chirality enhancement. However, it’s important to address this concept delicately because it amplifies all signals, not just chiral ones. One proposed mechanism in chirality enhancement comes from the coupling effect between the evanescent electric field and the incident magnetic field198. Because the phase difference between the induced electric field and the incident electric field is 90° in linear polarization at the resonance condition199. However, this interpretation is not sufficient because the phase retardation effect may be altered by damping and multipole effects in various structures, which involve complex fields that affect the local chiral density. In the case of plasmonic nanostructures, electric dipole and quadruple modes are primarily excited rather than magnetic dipole and quadruple modes83,84, making it challenging to distinguish between the effects of near-field enhancement and chiral near-field enhancement. Moreover, in the case of the SERS signal, the Raman scattering signal is first enhanced by near-field enhancement and then secondarily enhanced upon radiation, making the influence of the electric field more dominant and difficult to trace back to its origin55. In other words, numerous theoretical predictions and explanations offer insights into the origin of inherent and induced chirality62,65,74,76,86,200,201, distinguishing between these in experiments remains challenging. To fully harness the potential of chirality enhancement, it is essential to clearly identify and elucidate the underlying mechanisms. Single particle spectroscopy techniques such as circular differential scattering could help address this issue63. Nonetheless, far-field measurements often suggest the involvement of multiple mechanisms, complicating their disentanglement. On the other hand, tip-enhance techniques capable of directly measuring chirality in the near-field region may provide solutions to these challenges. Lastly, we discussed recent biomedical applications of chiral nanophotonics. These techniques allow for high sensitivity, real-time detection of chirality. However, it remains imperative to overcome extant challenges associated with selectivity. In the future, we anticipate that chiral nanophotonics will find increasing applications in biomedicine, owing to its unmatched advantages, such as high sensitivity, cost-effective, and rapid diagnosis capabilities.

Responses