Photonic topological insulators in femtosecond laser direct-written waveguides

Introduction

Topological insulators (TIs) are unique physical structures that exhibit insulating properties in their interior while being conductive on their surface1. A key characteristic of TIs is the presence of edge states, which exhibits robust unidirectional transport without backscattering, even in the presence of defects or disorders. The concept of TIs originated from the discovery of the integer quantum Hall (IQH) effect in 19802, which holds that the edges of two-dimensional (2D) electron gases display quantized Hall conductance under intense magnetic fields, while the bulk material remains insulating. The TKNN model proposed by Thouless et al. established a connection between quantum Hall conductance and the topological properties of electron bands in a magnetic field3. Although an external magnetic field is crucial for inducing the IQH effect in 2D electron gases, the generation of nontrivial topological systems does not always require such a field. In 1988, Haldane introduced a model which can break the time-reversal symmetry of the system, allowing for a non-zero Chern number without an external magnetic field, which led to the anomalous quantum Hall effect4. In 2005, Kane and Mele discovered that, without breaking the time-reversal symmetry, Kramer’s theorem ensures the degeneracy of energy levels of electron spin states, which makes for the formation of paired topological edge states in the system, known as the quantum spin Hall effect5,6. The discovery of the quantum spin Hall effect enables the observation of topological edge states in systems preserving time-reversal symmetry. These findings established a theoretical foundation for further exploration in topology and facilitated the realization of various TIs in condensed matter systems. However, experimental realization of these TIs faces significant challenges due to limitations in experimental conditions and other factors. Notably, it has become clear that topological phases are not exclusive to electronic materials; they can also be realized in bosonic particles, such as photons. It is well known that electrons are fermions obeying Fermi-Dirac statistics, while photons are bosons governed by Bose-Einstein statistics. This distinction introduces new physics and unique challenges associated with the bosonic nature of light. These findings not only provide effective and convenient pathways to achieve topological phenomena in condensed matter systems but also revolutionize our fundamental understanding of how light can be manipulated in entirely new ways.

The field of topological photonics originated in a famous work by Haldane and Raghu in 2008, which proposed the utilization of light to replicate the quantum Hall effect observed in 2D electron gases under magnetic fields7. This idea was quickly put into practice by creating a gyromagnetic photonic crystal made of ferrite rods in the microwave range8,9, which inspired a series of studies on photonic TIs. However, the gyromagnetic materials exhibited limited magnetic-optical effects at optical frequencies. Thus, researchers began to explore the possibility of generating an artificial magnetic fields for photons10,11,12. In 2013, the first photonic TIs were successfully demonstrated in femtosecond laser direct-written (FLDW) photonic waveguides, demonstrating their ability to protect light transport against defects and disorder13. Concurrently, experiments on aperiodic coupled resonator systems also demonstrated topological protection against lattice disorder14,15. These studies have sparked a wave of research resulted in experimental demonstrations of topological phenomenon in different synthetic platforms ranging from electric circuits16,17 to acoustics18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 and photonics25,26,27,28,29,30. Meanwhile, the diverse landscape of topological physics in 3D condensed matter systems has opened up exciting new opportunities for 3D topological photonics, including the exploration of gapless topological materials characterized by their exotic band degeneracies. Recent experimental demonstrations of gapless photonic topological phases—related to Weyl points, Dirac points, and nodal lines—on optical artificial platforms have garnered significant attention in the field31,32,33. In addition to the optical platforms previously mentioned, photonic TIs have been successfully implemented in many other experimental platforms34,35, including plasmonic systems36,37,38,39,40,41, metamaterials42,43,44,45,46, and photorefractive waveguides47,48,49,50,51,52. For example, a valley-Hall photonic TI was demonstrated using a designer surface plasmon crystal, which consists of metallic patterns deposited on a dielectric substrate40. The topological edge states exhibiting valley-dependent transport were directly visualized in the microwave regime. Additionally, photonic topological surface-state arcs connecting topologically distinct bulk states were experimentally observed in a chiral hyperbolic metamaterial42. Furthermore, a square-root higher-order topological insulator was realized in photorefractive waveguides49. This topological structure supports two types of corner states that exist in different energy band gaps with distinct phase structures. The higher-order topological properties of this system are derived from one of its parent Hamiltonians, which features a breathing Kagome lattice.

As a significant class of topological systems for controlling light, FLDW photonic waveguides play an important role in the realization of topological phases and applications of topological photonics. The FLDW technique is an advanced and powerful material-processing method that utilizes the ultrashort pulse duration and ultrahigh peak power of femtosecond lasers for micro-/nanoscale processing53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69. The ultrashort pulse duration effectively minimizes heat-affected areas, while the ultrahigh peak power induces various nonlinear interactions like multiphoton absorption, tunneling ionization, and avalanche ionization53,54,55. Additionally, the FLDW technique offers truly-3D processing capabilities70, allowing for the creation of diverse 3D micro-/nanoscale photonic structures, such as 3D optical waveguides, in transparent optical materials71. The history of FLDW can date back to 1996 when Davis et al.72 successfully fabricated waveguide structures inside glasses using tightly focused femtosecond laser pulses. Subsequent researches mainly focused on the development of high-quality and multifunctional 3D optical waveguides55. FLDW technique offers numerous advantages for precision material machining, including flexibility in 3D waveguide fabrication, ultra-compact and large-scale integration of micro- and nanostructures on a chip, in situ rapid fabrication capabilities, and a wide range of adjustable processing parameters (such as central wavelength, pulse width, repetition rate, pulse energy, polarization direction, scanning velocity, and focusing depth) that can be tailored to meet specific fabrication requirements. Typically, a microscope objective can be used to focus the incident femtosecond laser onto transparent materials (e.g., dielectric crystals and optical glasses). By moving the femtosecond laser relative to these materials, and employing techniques like refractive index modification and ferroelectric domain inversion, various micro- and nanostructures can be created along the laser’s moving trajectory (i.e., in situ fabrication). Benefited by the ultra-high machining accuracy and flexible 3D processing capabilities of FLDW, ultra-compact and large-scale micro- and nanostructures (such as waveguide structures and devices) can be fabricated directly within transparent materials by simply designing and optimizing the writing path of the femtosecond laser in 3D space. Moreover, the central wavelength of the femtosecond laser is adjustable, which allows for potentially higher machining accuracy with shorter wavelength. For instance, when fabricating periodic surface structures (known as laser-induced periodic surface structures), shorter wavelength allows the periodicity to reach hundreds of nanometers or even smaller (such as the second or third harmonic generation from the fundamental femtosecond laser). Additionally, the switchable wavelength feature of FLDW enables the selection of an appropriate femtosecond laser wavelength based on the absorption and transmission properties of specific transparent materials, enhancing its applicability across diverse materials. Overall, the FLDW technique plays a crucial role in modern manufacturing due to its unique processing mechanism, high precision, 3D fabrication capabilities, and promising applications across various fields. With the development and innovation of FLDW technology, its application in many fundamental research fields and high-tech fields will become more extensive and in-depth.

In this review, we provide an overview of the rapid developments in topological phenomena in FLDW photonic waveguides, with a focus on photonic topological phases and their integration with non-Hermiticity, nonlinearity and quantum physics. This review is structured as follows: the “Femtosecond laser direct-written photonic waveguides” section covers the basics of FLDW photonic waveguides, including experimental fabrication and beam propagation behavior in photonic waveguides. The “Topological insulators in femtosecond laser direct-written photonic waveguides” section discusses the different categories of photonic TIs achieved through various lattice types, such as crystalline TIs in static FLDW waveguides and Floquet TIs in longitudinally modulated FLDW waveguides. The “Non-Hermitian topological states in femtosecond laser direct-written photonic waveguide” section explores the non-Hermitian topology characterized by distinct loss types in FLDW photonic waveguides. The “Nonlinear topological insulators in femtosecond laser direct-written photonic waveguide” section presents recent advancements in the interaction between nonlinearity and topology in FLDW photonic waveguides. The “Topological quantum photonics in femtosecond laser direct-written photonic waveguides” section presents recent advancements about topological quantum photonics in FLDW photonic waveguides. Finally, the “Conclusion and outlook” section offers a conclusion and discussion on future research directions of photonic TIs in FLDW photonic waveguides.

Femtosecond laser direct-written photonic waveguides

Fabrication of femtosecond laser direct-written photonic waveguides

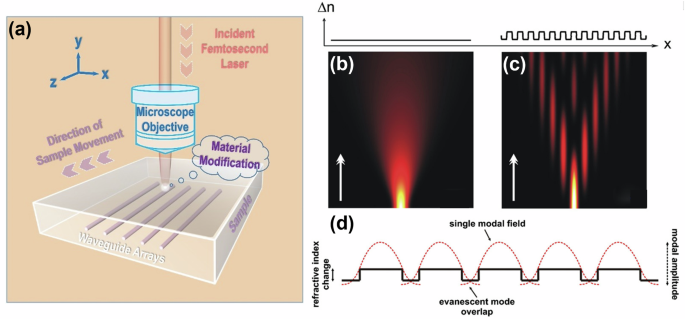

To fabricate high-quality 3D optical waveguides using the FLDW technique in transparent materials (e.g., glasses and dielectric crystals), a microscope objective is typically employed to tightly focus a femtosecond laser into the samples. At the focus of the femtosecond laser, a series of nonlinear interactions (e.g., multiphoton absorption, tunneling ionization, and avalanche ionization) can occur, leading to permanent modifications in the material. For example, the refractive index can be changed, and it can generally be divided into two categories: positive refractive index change (i.e., refractive index increase) and negative refractive index change (i.e., refractive index decrease). It should be noted that the types of the refractive index changes at the femtosecond laser focus are not only closely related to the femtosecond laser processing parameters, but also influenced by the properties of material itself. As for a specific transparent optical material, the desired type of refractive index change could be obtained by optimizing numerous processing parameters of femtosecond laser (e.g., center wavelength, repetition rate, pulse energy, polarization direction, scanning speed and focusing depth). Generally speaking, the 10−3–10−2 refractive index increment in waveguide core is enough for guiding light. In this review, the positive refractive index change (i.e., the guiding regions of optical waveguides are femtosecond-laser-irradiated areas) is primarily utilized to fabricate various and versatile waveguide arrays. Theoretically speaking, FLDW technique can fabricate arbitrary 3D waveguide structures in various different material systems, which is particularly important for on-chip 3D photonic integration. Figure 1a depicts the fabrication diagram of optical waveguides by FLDW technique, in which a microscope objective is used to focus the incident femtosecond laser (propagating along y axis) into a transparent sample. The femtosecond-laser-induced material modifications (i.e., positive refractive index change) can occur at the laser focus region. By moving the sample along a direction (e.g., z axis) vertical to the direction of incident femtosecond laser, the optical waveguides can be created at the femtosecond-laser-irradiated area. Besides, a kind of simple waveguide array is depicted in Fig. 1a as well, which is composed of 5 optical waveguides arranged along x axis. In Fig. 1a, the z-axis direction is the propagation direction of light beam in optical waveguides. The performance of the FLDW 3D waveguide devices is primarily affected by the propagation loss of each optical waveguide, which is closely related to the femtosecond-laser-induced refractive-index increment in the guiding region. Lower propagation loss allows for better guiding performance of optical waveguide. In general, the propagation loss of waveguide will decrease with the improvement of refractive-index increment. According to the published research results, the propagation loss of optical waveguide in nonlinear materials (e.g., lithium niobate crystals) is much higher than that in linear materials (e.g., optical glasses). Hence, as for general TI investigations, femtosecond-laser-written waveguides in optical glasses are preferred, due to more stable performance and larger femtosecond-laser parameter window. If involving nonlinearity, given that relatively in-depth studies conducted on fabricating and optimizing lithium niobate waveguides, the femtosecond-laser-written nonlinear optical waveguides in lithium niobate crystals may be a good choice. The FLDW technique is generally considered a cold (i.e., non-thermal) processing technique. In 2020, Jörg et al. investigated the influences of microscope-objective vignetting and proximity effect on refractive index profile at waveguide center and waveguide edge73. They demonstrated that a high laser power during waveguide fabrication can reduce the refractive index difference between center and edge of waveguide, thus increasing the refractive-index-profile uniformity of the whole waveguide, simultaneously improving the refractive index contrast between the waveguide and surrounding material. The effect of gradient refractive index at the waveguide edge is affected by both selected femtosecond-laser processing parameters and material properties, which is very complicated and will be gradually revealed with the deepening of the investigations on interaction processes between femtosecond laser and transparent materials. Moreover, researches on photonic TIs using FLDW technique are not limited to solid materials, FLDW-fabricated structures can also be created on substrate surfaces and in air. For example, Jörg et al. experimentally explored the impact of time-dependent defects on the robustness of edge transport in a Floquet system consisting of helically curved waveguides74. They fabricated these helically curved waveguides using a negative tone photoresist and demonstrated that single dynamic defects do not disrupt the chiral edge current, even under strong temporal modulation. For more information on FLDW-fabricated structures, we recommend a recent review by Wang et al.75.

a Diagram of optical waveguides fabrication using FLDW technique. The incident femtosecond laser (along y axis) is tightly focused into the transparent material by a microscope objective. Then, material modifications occur in the focus of femtosecond laser. By moving the material (along z axis) relative to femtosecond laser, the optical waveguides can be produced in femtosecond-laser-irradiated regions. b Beam diffraction in a continuous medium81. c Beam diffraction in a medium with periodically changing refractive index81. d Sketch of a waveguide array. The modal fields of the individual guide overlap, which causes an energy transfer between adjacent guides81.

Beam propagation in photonic lattices

Photonic lattice72,76,77,78,79,80, a waveguide coupling array with a periodically distributed refractive index, typically operates on micrometer scale with a refractive index modulation range of Δn = 10−5–10−3. The propagation of light in the photonic lattice follows the paraxial propagation equation:

where Ψ(x, y, z) is the electric field envelope of the probe beam, z is the longitudinal propagation distance, k0 is the wavenumber, and n0 is the background refractive index of the medium. Δn is the refractive index change that defines the photonic lattices. As is well known, the evolution of wave functions in quantum systems follows the Schrödinger equation:

Equations (1) and (2) share the same mathematical form, where the time variable t in the Schrödinger equation (Eq. (2)) corresponds to the propagation direction z in the paraxial propagation equation (Eq. (1)). This analogy suggests that the evolution of light in a photonic lattice is similar to the evolution of a wave function in a quantum system. Meanwhile, photonic lattices characterized by their periodic structure, exhibit energy band structures similar to electronic crystals. These unique properties of photonic lattices enable the observation of topological phenomena that are difficult to study in quantum systems due to experimental constraints. Meanwhile, the discrete diffraction behavior of the beam in the photonic lattice arises from the coupling between waveguides81, as shown in Fig. 1b–d. By comparing Fig. 1b, c, different transmission characteristics can be found between a continuous system (Fig. 1b) and a 1D waveguide array (Fig. 1c). When propagating in 1D waveguide array, the beam no longer maintains Gaussian distribution but is discretely coupled to the waveguides on both sides, leading to linear expansion of the transmission envelope. The maximum energy is consistently distributed in the outermost part of the discrete diffraction pattern. This phenomenon can be explained by the discrete Schrodinger equation. Utilizing the coupled mode theory, a nearest neighbor coupling approximation is applied to 1D photonic waveguide array, where the nth waveguide can only couple with the (n − 1)th and (n + 1)th waveguides. The coupling mode equation of the nth waveguide is:

Here φn is the electric field of nth waveguide, c is the coupling coefficient between nearest neighbor waveguides, βn is the lattice potential of nth waveguide. The discrete diffraction phenomenon shown in Fig. 1c can be obtained by solving Eq. (3). The modal fields of the individual guide overlap, which causes an energy transfer between adjacent guides, as shown in Fig. 1d. The analysis of simple 1D discrete diffraction reveals that the photonic waveguide system follows the coupling mode determined by the discrete Schrodinger equation. This characteristic allows the system to explore complex structures that are difficult to achieve in many quantum systems. For example, by adjusting the coupling coefficient c, researchers can achieve crystalline TIs. Varying the size of βn enables the introduction of a disordered lattice potential energy for studying Anderson localization. The inclusion of the imaginary component of βn enables the realization of a non-Hermitian optical system.

Topological insulators in femtosecond laser direct-written photonic waveguides

Topological crystalline insulators in 1D femtosecond laser direct-written photonic waveguide

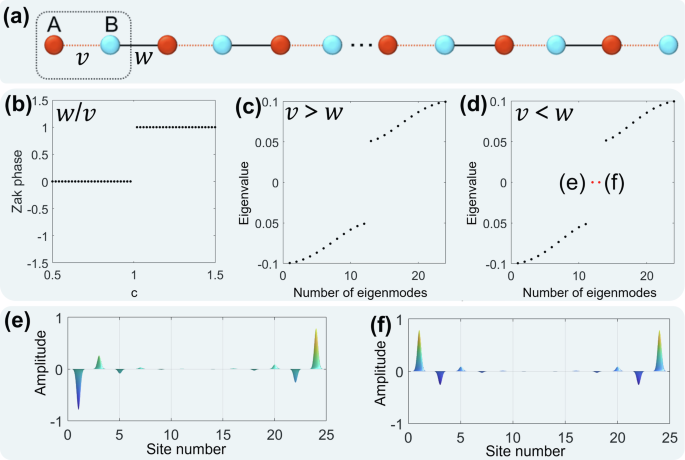

Topological crystalline insulators (TCIs) are well-known topological phases of matter characterized by nontrivial topology arising from lattice crystalline symmetries51,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94. The 1D Su-Schrieffer-Heeger (SSH) model is a representative example95, characterized by a periodic array with two sites per unit cell. The coupling between intracell sites alternates with the coupling between intercell sites, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. In 1989, Zak introduced the concept of the Zak phase to describe the topological properties of 1D lattices96. The Zak phase serves as a topological invariant for 1D lattices, defined as:

where |uk〉 represents the eigenstate of a particular band. In the SSH model, changing the values of v and w results in the Zak phase being either 0 or 1: it is 1 when w > v and 0 when w < v, as illustrated in Fig. 2b. Consequently, the SSH structure exhibits two distinct topological phases, with one being topologically trivial (Fig. 2c) and the other being nontrivial (Fig. 4d). In the topologically nontrivial case, the SSH lattice supports two degenerate zero-energy edge states, as depicted in Fig. 2e, f. The SSH model has found applications in various physical disciplines such as cold atoms97,98, acoustic99,100 and photonics101,102,103. Furthermore, discussions on the SSH model also extend to non-Hermitian104,105,106 and nonlinear regimes47,48,107,108,109.

a Scheme of a 1D SSH lattice consisting of two sites (A, B) per unit cell shown in a dark-dashed square. b Calculated Zak phase as a function of the dimerization parameter c, c = w/v. c Energy spectrum of a trivial SSH lattice with defined parameters (w = 0.25, v = 0.75). d Energy spectrum of a nontrivial SSH lattice with defined parameters (w = 0.75, v = 0.25). e, f Mode profiles of nontrivial edge states as marked in (d).

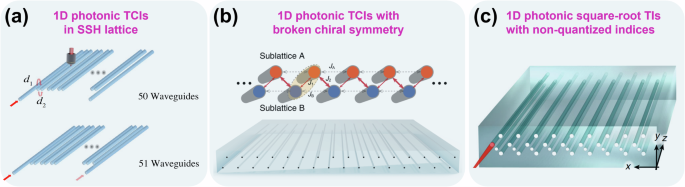

1D waveguide arrays can be fabricated using FLDW technology. The coupling coefficient can be adjusted by changing the distance between nearest neighbor waveguides, which enables effective and convenient realization of the 1D topological models. As shown in Fig. 3a, Wang et al. experimentally demonstrated a direct measurement of edge states, localization length, and critical exponent from survival probability in FLDW photonic waveguides103. Using FLDW technology, they created two types of finite photonic SSH lattices with chain lengths of M = 50 or 51, and measured the survival probability at the lattice boundary to determine the corresponding localization length. By comparing the localization length with the distance from transition point, they obtained a critical exponent of v = 0.94 ± 0.04 at the phase boundary. This work offers an alternative approach to characterize topological phase transitions and extract their key physical quantities. Additionally, Jiao et al. explored the significant role of lattice symmetry in 1D topological systems102. By engineering a 1D photonic lattice to introduce long-range hopping, they created a photonic extended SSH model that lacks chiral symmetry but maintains inversion symmetry, as shown in Fig. 3b. When the long-range hopping increases to a certain level, the edge states become delocalized, and their energies shift into the bands of the photonic lattice, even though the bulk topological invariant remains unchanged and non-zero. This indicates that while inversion symmetry protects the quantized Zak phase, the edge states can still disappear within the topologically nontrivial phase. Meanwhile, Queraltó et al. explored the potential of supersymmetric transformations in photonic topological systems110. By experimentally creating a 1D SSH lattice in FLDW photonic waveguides, they demonstrated topological phase transitions induced by discrete supersymmetry transformations. Their findings demonstrate that supersymmetric transformations can systematically modify and reconfigure the topological properties of a system. As shown in Fig. 3c, a new class of TIs, called square-root TIs, was experimentally demonstrated in a quasi-1D lattice made of Aharonov–Bohm cages111. This was achieved by introducing an auxiliary coupled waveguide into the double waveguides, which generated a flux ϕ in each plaquette. These TIs support multiple robust boundary states with a non-quantized topological index. Moreover, the presence of a pseudomagnetic field was experimentally demonstrated in inhomogeneous strained graphene compose of FLDW photonic waveguides112. This pseudomagnetic field results in photonic Landau levels that are separated by bandgaps, which offers a new method to induce the topological phase in a static manner.

a Photonic topological edge states in SSH lattice103. b Photonic TIs in the extended SSH lattice with broken chiral symmetry102. c Photonic square-root TIs with non-quantized indices in quasi-1D diamond lattice with an auxiliary waveguide in each plaquette111.

Higher-order topological insulators in 2D femtosecond laser direct-written photonic waveguides

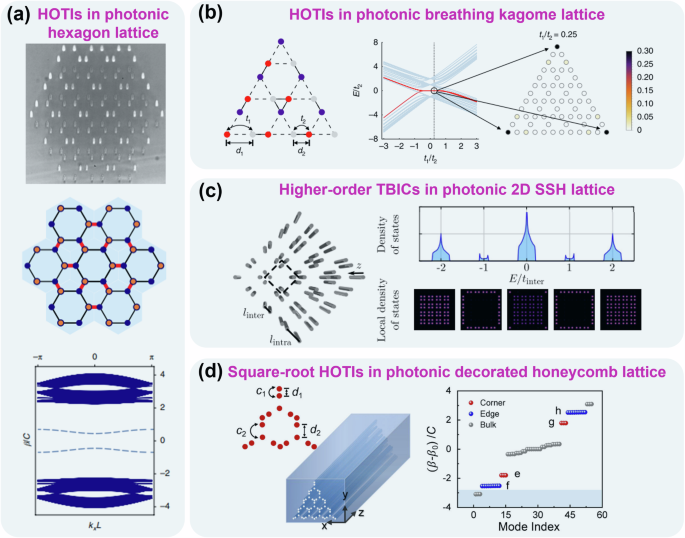

In recent years, TCIs have evolved from 1D to 2D even higher-dimensional forms, leading to the emergence of a new topological phase known as high-order topological insulators (HOTIs)84,90,113,114,115,116,117. A key characteristic of HOTIs is their ability to enhance our understanding of topological materials by going beyond the traditional bulk-boundary correspondence. Unlike conventional TIs, which support only (d−1) D boundary states, HOTIs can host both (d−1) D and (d−n) D boundary states (where n ≥ 2), including the emergence of 0D corner states in 2D systems. This phenomenon is linked to topologically quantized quadrupole and higher-order electric moments in electronic systems. The discovery of HOTIs has expanded the concept of symmetry-protected topological phases and refined our understanding of traditional TIs, sparking a surge of research across various fields. Notably, a variety of HOTIs have been successfully demonstrated in FLDW photonic waveguides118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125. For instance, Noh et al. experimentally confirmed the existence of photonic HOTIs in a C6v symmetric hexagon lattice by using the FLDW technique118, as shown in Fig. 4a. This allows to observe the 0D corner-localized mid-gap states which are topologically protected by chiral symmetry. Additionally, Hassan et al. demonstrated higher-order topological corner states in breathing Kagome lattices made of FLDW photonic waveguides119, as illustrated in Fig. 4b. Notably, by designing waveguide arrays with smaller lattice spacing and fewer waveguides, they successfully observed the ‘fractionalization’ of light at all three corners of the triangular sample, even in the presence of defects. Furthermore, Cerjan et al. made significant contributions to this field by revealing that protected boundary-localized states can exist within topological bands, rather than solely between them120. They experimentally confirmed the existence of higher-order topological bound states in the continuum (HOTBICs) within a nontrivial 2D SSH lattice formed by FLDW waveguides (Fig. 4c). Unlike traditional HOTIs in 2D systems, where corner states are located within the band gap, HOTBICs can exhibit unconventional corner states that remain isolated from the surrounding bulk states even in the absence of a band gap. By utilizing an auxiliary waveguide to excite zero-energy states that spatially overlap within the array, they demonstrated the surprising localized properties of HOTBICs. Moreover, Kang et al. demonstrated 2D square-root HOTIs in photonic waveguides fabricated in fused quartz glass using the FLDW technique (Fig. 4d)121. In contrast to conventional HOTIs, these square-root HOTIs present two types of corner states with in-phase and anti-phase mode profiles in two distinct band gaps. They directly observed a light beating pattern by exciting the superposition of both corner modes, and highlighted the protection of photonic square-root HOTIs by the symmetry of the crystalline lattice.

a Photonic topological mid-gap corner modes in a C6v symmetric hexagon lattice118. b Photonic topological corner states in breathing kagome lattice119. c Higher-order topological bound states in the continuum in the 2D SSH lattice120. d Square-root higher-order topological insulators in the decorated honeycomb lattice121.

Floquet topological insulators

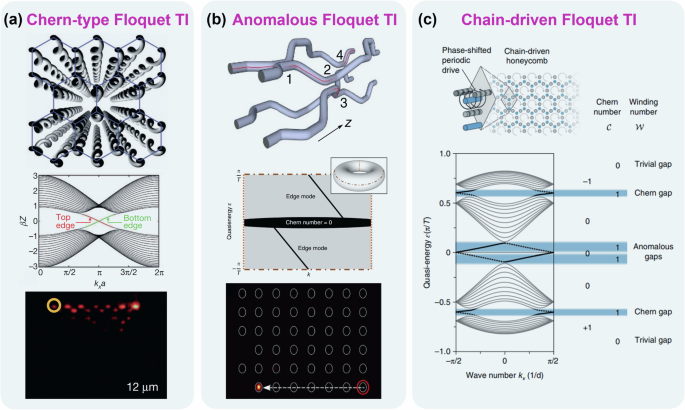

Over the past decade, there has been a significant emphasis on the utilization of periodic driving, known as Floquet systems, in the exploration of topological phases. This approach has demonstrated the capability to convert a traditional system into a topological one, unveiling distinct topological features that are absent in static systems. In 2013, Rechtsman et al. conducted the pioneering experimental showcase of TIs in photonic waveguide arrays13. Their design featured a pattern of helical waveguides arranged in a graphene-like honeycomb lattice, disrupting the time-reversal symmetry, which is a crucial aspect of Floquet TIs, as depicted in Fig. 5a. Meanwhile, they experimentally demonstrated that light transport exhibits topological protection against defects and disorders. The topological properties of these Floquet TIs are still characterized by the Chern number, for which they are also referred to as Chern-type Floquet TIs. Subsequently, in 2017, a new category of Floquet TIs emerged, known as anomalous Floquet TIs126,127. For which a specific theoretical approach was employed to induce Floquet topological phases through tailored discrete coupling protocols (Fig. 5b). An intrinsic characteristic of such Floquet TIs is their challenge to the conventional bulk-edge correspondence. Anomalous Floquet TIs support the existence of topological chiral edge modes even when the Chern numbers of all bands are zero. Moving forward to 2022, Pyrialakos et al. introduced an unconventional type of Floquet TIs termed Chain-driven Floquet TIs128, as illustrated in Fig. 5c. Unlike the previously mentioned Floquet TIs induced by helical lattice motions or tailored discrete coupling protocols, Chain-driven Floquet TIs employ connective chains with periodically modulated on-site potentials to establish a fascinating topological system, which accommodates multiple topological edge modes simultaneously, encompassing both Chern-type and anomalous chiral edge states. These studies serve as important references for research on Floquet TIs in various fields, revealing many intriguing advancements. For example, while previous work mainly focused on the differences in topological invariants between Chern-type Floquet TIs and anomalous Floquet TIs, Zhang et al. shifted their attention to the robustness differences between these two types129. They experimentally demonstrated an anomalous non-reciprocal topological phase, where edge transmission is quantitatively stronger than in the Chern phase, which remains resilient even against parametric fluctuations much larger than the bandgap size. They investigated the general conditions required to achieve this unusual effect in systems composed of unitary three-port non-reciprocal scatterers connected by phase links. They demonstrated that anomalous edge transmission modes exhibit superior robustness compared to Chern modes when subjected to phase-link disorder of arbitrary magnitude. Experimental confirmation of the exceptional resilience of the anomalous phase was achieved, demonstrating its functionality in various arbitrarily shaped disordered multi-port prototypes. These findings pave the way for efficient, arbitrary planar energy transport on 2D substrates for wave devices, offering full protection against significant fabrication flaws or imperfections.

a Chern-type Floquet TIs induced by helical lattice motions13. b Anomalous Floquet TIs induced by four different bonds cyclic driving protocol126,127. c Chain-driven Floquet TIs induced by periodically modulated on-site potentials128.

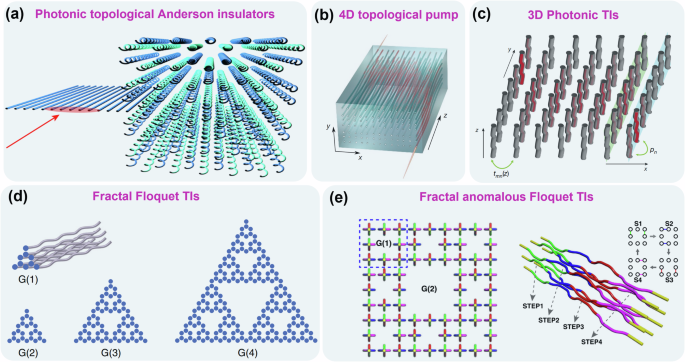

The shape of a waveguide can be easily controlled using FLDW technology, which facilitates the research and development of topological insulators based on the Floquet mechanism. For instance, Maczewsky et al. experimentally demonstrated fermionic time-reversal symmetry in photonic TIs130. By exploiting the bipartite substructure of the underlying photonic lattice to encode a pseudo-spin 1/2, they designed and established FLDW waveguides with a driving protocol that implements effective fermionic time-reversal symmetry. This approach enabled them to directly observe the resulting counter-propagating edge states and confirm the presence of fermionic time-reversal symmetry in the system through interferometric measurements. This finding allows for the utilization of fermionic properties in bosonic systems, offering new opportunities for applications in bosonic systems. Moreover, Stützer et al. conducted an experimental demonstration of a photonic topological Anderson insulator in helical waveguides array arranged in a honeycomb geometry with detuned sublattices (Fig. 6a)131. By introducing on-site disorder in the form of random refractive index variations in the waveguides, the system transitioned from a trivial phase to a topological one, which demonstrated experimentally that disorder can enhance transport rather than arrest it in topological Anderson insulator physics. Moreover, a dynamically generated 4D quantum Hall system was successfully realized in tunable 2D arrays of photonic waveguides, which incorporates two additional synthetic dimensions132, as illustrated in Fig. 6b. By constructing an inter-waveguide separation, Zilberberg et al. demonstrated the propagation of light through the samples in these two synthetic dimensions, achieving a 2D topological pump that operates from edge to edge and corner to corner. This work provides a platform for studying higher-dimensional topological physics. As shown in Fig. 6c, Lustig et al. experimentally demonstrated a photonic TI in synthetic dimensions133. Utilizing the FLDW technique, they created a photonic lattice in which photons experience an effective magnetic field within a space that combines one spatial dimension and one synthetic modal dimension. This lattice supports topological edge states in the spatial-modal framework, leading to a resilient topological state that spans the bulk of a 2D real-space lattice. Consequently, they directly observed the propagation of the topologically protected edge state, which do not exist at the spatial boundaries of the system, but at the edge of the synthetic space. Shortly thereafter, Lustig et al. made another significant advancement in the study of Floquet TIs at higher dimensions using FLDW photonic waveguides134. They introduced an additional modal dimension to transform a 2D photonic system into a 3D topological system. This innovation enabled them to successfully demonstrate a 3D photonic TI that supports topologically protected edge states propagating along 3D trajectories, facilitated by a dislocation. This achievement marks the first realization of a Floquet 3D TI and paves the way for exploring higher-dimensional topological phases in both theoretical and experimental contexts. It is worth mentioning that Yang et al. proposed Floquet fractal TIs: photonic TIs in a fractal-dimensional lattice (Sierpinski gasket) composed of helical waveguides (Fig. 6d)135. Building on this, in 2022, Biesenthal et al. fabricated a periodically driven photonic lattice with Sierpinski geometry in FLDW waveguide arrays, by which they observed robust light transport along the outer and inner edges of the fractal landscape136. Furthermore, in 2023, Li et al. experimentally demonstrated a fractal anomalous Floquet TIs based on dual Sierpinski carpets consisting of directional couplers137 (Fig. 6e). These fractal lattices support a variety of chiral edge states with fewer waveguides and facilitate near-perfect hopping of quantum states with high transfer efficiency.

a Photonic topological Anderson insulator in a Hybrid structure composed of a 1D straw and a 2D honeycomb lattice of helical waveguides131. b 2D topological pump in 4D quantum Hall system132. c Photonic TIs in synthetic dimensions133. d Fractal Floquet TIs135,136. e Fractal anomalous Floquet TIs137.

Non-Hermitian topological states in femtosecond laser direct-written photonic waveguides

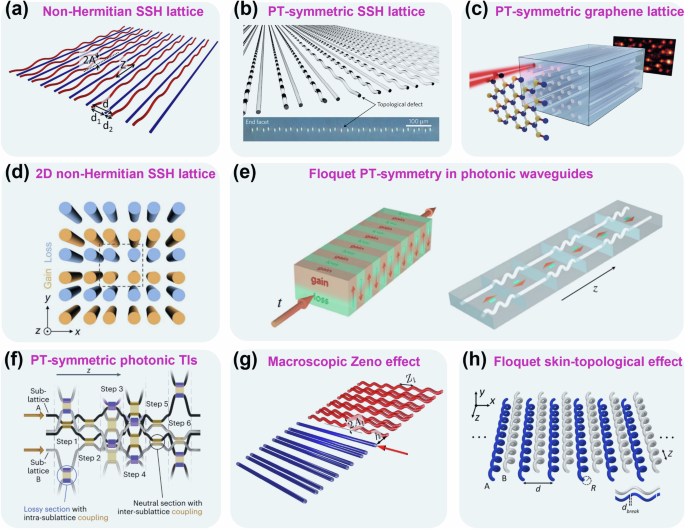

Recent advances in non-Hermitian physics opened numerous opportunities for a wide range of basic research and engineering applications138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145. In a Hermitian system, the total energy is conserved, and the associated Hamiltonian has a real eigenenergy spectrum, corresponding to the intuitive requirement that energy is a real-valued quantity. In non-Hermitian systems, on the contrary, energy exchanges with the environment, and the corresponding Hamiltonian generally features a complex spectrum. In particular, non-Hermitian systems exhibiting parity-time (PT) symmetry challenges the conventional notion that real eigenvalues are exclusively linked to Hermitian observables, thus have garnered significant interest141,142,144,146. In a PT-symmetric system, real eigenvalues can arise in the presence of gain and loss, provided that the relation [PT, H] = 0 holds. Notably, the transformation of eigenvalues from real to complex indicates the occurrence of a PT symmetry phase transition, which is invariably accompanied by the emergence of exceptional points. Recent advancements in non-Hermitian physics enable the manipulation of gain and loss in electromagnetic waves through the use of imaginary potentials. This development offers a potential framework for rethinking established platforms by incorporating gain and loss as a new degrees of freedom. Additionally, FLDW waveguides can easily introduce loss through the implementation of “wiggling” waveguides, “intermittent” waveguides, and artificial scatterers, providing an excellent platform for studying non-Hermitian physics. Moreover, the integration of topology and non-Hermiticity contributes to significant progress in complex systems, including PT-symmetric TIs, topological light steering, funneling, and the Floquet skin-topological effect, and so on. For instance, in 2015, Zeuner et al. reported the first experimental observation of a topological phase transition in a non-Hermitian system147, as illustrated in Fig. 7a. By spatially wiggling waveguide channels to induce bending losses yields highly tunable non-Hermiticity, they experimentally constructed a non-Hermitian SSH lattice in FLDW waveguides, thereby observed the topological transition in such non-Hermitian system through bulk measurements. As shown in Fig. 7b, Weimann et al. experimentally established a crossed SSH lattice with tailed loss using FLDW waveguides, thereby observed a PT symmetric topological defect state148. In 2019, Kremer et al. developed a new technology to introduce artificial losses into the photonic lattice by adding artificial scatterers to the waveguides, which induced bending losses during fabrication149. Using this approach, they designed and experimentally realized a 2D PT-symmetric model based on FLDW waveguides with engineered refractive index and alternating loss, as depicted in Fig. 7c. This work successfully demonstrated a non-Hermitian 2D topological phase transition associated with the emergence of topological mid-gap edge states. Moreover, Kang et al. conducted an experimental study showcasing a method to adjust the localization of HOTBICs through non-Hermiticity in a 2D SSH structure using FLDW waveguides150, as shown in Fig. 7d. They systematically explored the interplay between PT symmetry and higher-order corner states, shedding light on the physical mechanism behind mitigating finite-size effects. In 2024, Liu et al. utilized periodic spatial modulation of loss in FLDW waveguides to achieve Floquet PT-symmetry in integrated photonics (Fig. 7e)151. By appropriately tuning the Floquet period, they demonstrated PT-symmetry phase transitions with customizable levels of gain/loss. Additionally, they achieved precise control over the system’s response through excitation ports, enabling real-time switching between suppression and amplification regimes. Meanwhile, Fritzsche et al. experimentally developed a periodically driven Floquet model that dynamically distributed non-Hermitian components in both spatial and temporal dimensions (Fig. 7f), exhibiting a non-Hermitian TI with a purely real spectrum152. Moreover, Ivanov et al. demonstrated the macroscopic Zeno effect in a topological non-Hermitian system comprising two finite SSH waveguide arrays, where controllable dissipation was introduced in one of the arrays (Fig. 7g)153. Interestingly, Sun et al. achieved the non-Hermitian skin effect for the first time in photonic Floquet TIs based on FLDW waveguides154. Through the introduction of structured loss in periodically driven waveguides, they observed the topological funneling of light at the left boundary and corner of 1D and 2D waveguide arrays, respectively.

a Topological edge states in a non-Hermitian SSH lattice147. b Topologically protected bound states in photonic PT-symmetric lattice148. c Non-Hermitian topological phase in 2D PT-symmetric graphene lattice149. d Higher-order bound states in non-Hermitian photonic waveguides150. e Floquet PT-symmetry in photonic waveguides151. f PT -symmetric photonic topological insulator152. g Macroscopic Zeno effect in a topological non-Hermitian system comprising two finite SSH waveguide arrays153. h Floquet skin-topological effect in photonic waveguides154.

Nonlinear topological insulators in femtosecond laser direct-written photonic waveguides

In recent years, there has been growing interest in the relationship between nonlinearity and topological physics, leading to the emergence of nonlinear TIs. Unlike conventional linear TIs, nonlinear TIs exhibit inherent reconfigurability, allowing the dynamics of their boundary states to be influenced by excitation intensity. This feature enables unique external control over topological phase transitions and the properties of the topological boundary states. FLDW waveguides with the optical Kerr nonlinearity155 offer an effective and convenient platform to realize many novel nonlinear topological phenomena. In the presence of the optical Kerr effect, for the dimensionless light field amplitude (varPsi) propagating along the normalized longitudinal coordinate z, the wave dynamics in FLDW waveguides obey the normalized continuous nonlinear Schrödinger equation:

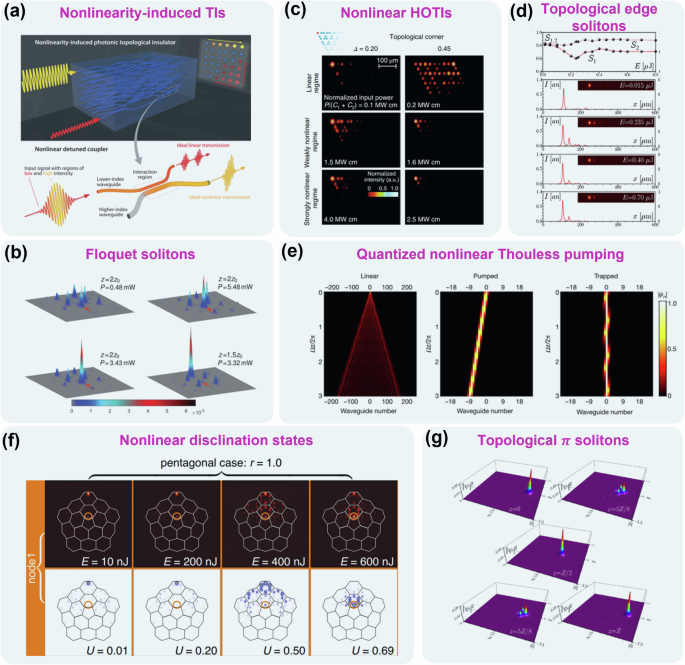

Here (p) represents the contrast of the refractive index modulation, and the lattice profile is defined by the function (R(x,y)). The term ({left|varPsi right|}^{2}varPsi) accounts for the intensity-dependent shift in the local propagation constant due to the optical Kerr nonlinearity. At low input powers, this term is minimal, resulting in linear light evolution. However, as the input power increases, the intensity-dependent phases can significantly alter the propagation dynamics at different lattice sites. Until now, a variety of nonlinear topological states have been successfully demonstrated in FLDW photonic waveguides. For instance, Maczewsky et al. conducted an experimental demonstration of a nonlinearity-induced photonic TI in a modified anomalous Floquet TI arrangement using FLDW waveguides (Fig. 8a)156. They revealed that the presence of nonlinearity can transform an initially topological trivial system into a nontrivial topological phase, thereby establishing nontrivial topology through the action of nonlinearity itself. Additionally, another intriguing phenomenon associated with nonlinear TIs was found by Mukherjee et al.157. They observed optical spatial solitons in an anomalous Floquet TI (Fig. 8b), which was achieved by employing periodically modulated FLDW waveguides. In the presence of nonlinearity, the optical Kerr effect facilitates the formation of an optical soliton-type wave that propagates along the edge of the topological structure without changing its shape. Furthermore, Kirsch et al. experimentally demonstrated a nonlinear photonic HOTI in a Kagome lattice created using FLDW technique (Fig. 8c)124. They systematically investigated the properties of the lattice in the topological phase and observed the formation of solitons and nonlinear topological corner states within this structure. In 2022, Kartashov et al. experimentally demonstrated two types of topological edge solitons emanating from different gaps in photonic trimer lattices that were created using FLDW technique (Fig. 8d)158. The out-of-phase and in-phase edge solitons can coexist in either different or the same topological gap, while showcasing qualitatively different intensity and phase structures that allow for their selective excitation with appropriately shaped inputs. Moreover, Jürgensen et al. conducted experiments that showcases quantized nonlinear Thouless pumping in a non-diagonal AAH lattice utilizing FLDW waveguides159, as shown in Fig. 8e. Their findings revealed that nonlinearity serves to quantize transport through soliton formation and spontaneous symmetry-breaking bifurcations. For weak nonlinearity, incident light formed a pumped soliton that travels across the lattice with a displacement matching the Chern number of the band from which it bifurcates. On the other hand, strong nonlinearity leads to nonlinear bifurcations of saddle-node, causing the solitons transition from the pumped state to the trapped state, which results in trapped solitons with a Chern number of zero. In 2023, Ren et al. observed nonlinear photonic disclination states in waveguide arrays with pentagonal or heptagonal disclination cores inscribed in a transparent optical medium160, as illustrated in Fig. 8f. They demonstrated that the robust nonlinear disclination states bifurcate from their linear counterparts, thus the location of their propagation constants in the gap, and consequently their spatial localization, can be controlled by their power. Additionally, Arkhipova et al. established a SSH array consisting of periodically wiggling waveguides, thereby observed photonic anomalous (pi) modes residing at the edge or in the corner of 1D or 2D FLDW waveguide arrays161. Furthermore, they demonstrated a new class of topological π solitons bifurcating from such modes in the topological gap of the Floquet spectrum at high powers. Such (pi) solitons are strongly wiggling nonlinear Floquet states, which exactly reproduce their profiles after each longitudinal period of the structure. Such kinds of nonlinear TIs pave the way for exciting applications, such as energy harvesting and lasing.

a Nonlinearity-induced photonic topological insulator in photonic waveguides156. b Floquet solitons in an anomalous Floquet topological insulator157. c Nonlinear second-order photonic topological insulators in photonic kagome lattice124. d Topological edge solitons in photonic trimer lattice158. e Quantized nonlinear Thouless pumping in a AAH lattice159. f Nonlinear disclination states in waveguide arrays with pentagonal or heptagonal disclination cores160. g (pi) solitons in oscillating waveguide arrays161.

Topological quantum photonics in femtosecond laser direct-written photonic waveguides

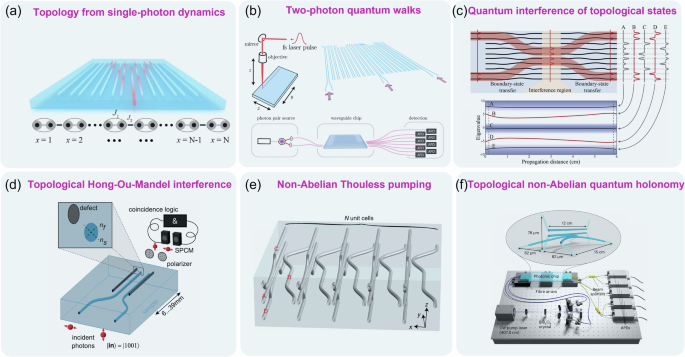

Quantum photonics is a rapidly developing field that merges fundamental science with technology, where quantum effects are central to its principles and applications29,162,163,164,165,166,167. At its core, quantum photonics explores the interactions between quantized light and matter, emphasizing the manipulation and active control of these interactions at the quantum level. Among various optical artificial platforms, FLDW photonic waveguides stand out for their true 3D processing capabilities and high-precision fabrication mechanisms. To date, successful demonstrations of quantum walks and quantum interference have been achieved in FLDW waveguides168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175. Additionally, the concept of topological photonics has been developed and applied in quantum photonics field, giving rise to a subdiscipline, namely, topological quantum photonics176,177,178,179, which focuses on the topological protection of photonic quantum states and their transport. As shown in Fig. 9a, Wang et al. extended the topological system and measurement into quantum regime101. By injecting single photons into the middle waveguide of SSH lattice fabricated by FLDW technique, they experimentally demonstrated a direct observation of the topological winding numbers. More importantly, they experimentally observed the topological phase transition points for the first time via single-photon dynamics. This approach based on single-particle dynamics in the real space provides a new route for direct measurement of topology, which complements the approach in ultracold atomic systems using Bloch state dynamics in the momentum space. As shown in Fig. 9b, two-photon quantum walks are also demonstrated in a photonic SSH lattice fabricated by FLDW technique, which suggests that the existence of the topological edge state has a significant influence on the quantum interference of indistinguishable photons180. At the trivial edge in the SSH lattice, the bunching behavior of the indistinguishable photons remains unchanged, whereas it becomes significantly distorted at the topological edge. Although one photon remains at the edge with high probability and the other mostly penetrates into the bulk, the probability of finding the photons close to each other after propagating through the sample has approximately the same magnitude as the probability that the photons leave the sample far away from each other. Meanwhile, the high-visibility quantum interference of two single photon topological boundary states were also demonstrated in FLDW photonic arrays181, as shown in Fig. 9c. Tambasco et al. engineered and realized a 50:50 topological beam splitter, which enables the measurement of the Hong-Ou-Mandel (HOM) interference with 93.1 ± 2.8% visibility. As shown in Fig. 9d, Ehrhardt et al. for the first time demonstrated topological HOM interference equipped with intrinsic topological protection against imperfections182. They fabricated a birefringent directional coupler made of two waveguides in fused silica using FLDW technique. By tailoring the birefringence of the waveguides within the coupler, they harnessed additional dynamics in the polarization degree of freedom to create artificial gauge fields with a quantized magnetic flux of π. As a result, they observed near-perfect HOM interference with −96.9 ± 0.8% visibility, confirming the predicted propagation-invariant suppression of coincidences. Furthermore, by comparing the two-photon suppression in the topological architecture to HOM interference in a conventional directional coupler that is subjected to similar perturbations, they experimentally demonstrated that their design effectively protects HOM interference from disturbances, such as impurities in the input states or variations in coupling strengths.

a Direct observation of topology from single-photon dynamics101. b Photonic two-particle quantum walks in SSH lattices180. c Quantum interference of topological states of light181. d Topological Hong-Ou-Mandel interference182. e Non-Abelian Thouless pumping in photonic waveguides184. f 3D non-Abelian quantum holonomy185.

Non-Abelian anyons have garnered increasing attention due to their unique properties and potential applications in quantum mechanics183. When non-Abelian anyons are exchanged through braiding along their world lines, their wave function exchange behavior can be described by a unitary matrix that is fundamentally different from that of fermions or bosons. Recently, the concept of non-Abelian topological charges was proposed and their non-commutative properties greatly enriched the classification of topological phases. In 2022, Sun et al. for the first time experimentally demonstrated non-Abelian Thouless pumping in a 1D Lieb lattice fabricated by FLDW technique184, as shown in Fig. 9e. By designing the coupling coefficients among the waveguides in the pumping direction, they made the system always supports degenerate flat bands that are protected by sublattice symmetry, which is the key to inducing non-Abelian topological physics. Therefore, they theoretically revealed the unitary matrix related to different pumping operations and verified them via experiment which measures the pumping sequence-dependent light diffraction patterns. Meanwhile, non-Abelian quantum holonomy has been experimentally realized in 2D and 3D using FLDW photonic waveguides185. Neef et al. designed the arrangement of these waveguides to create a star-graph configuration, which is characterized by a central mode and radial modes, as illustrated in Fig. 9f. They exploited a unique degree of freedom inherent to bosonic systems by utilizing either one or two indistinguishable photons as input states. This work paves the way for designing quantum optical analogs that can shed light on aspects of quantum chromodynamics and may also serve as valuable tools for the experimental investigation of gauge symmetries.

Conclusion and outlook

In summary, we have reviewed the recent developments of topological photonics in FLDW waveguides. Firstly, we discussed the SSH model as a paradigm for topological physics, highlighting its key features and exploring experimental demonstrations of novel topological phenomena in photonic 1D and quasi-1D lattices. Then, we introduce the realm of photonic HOTIs in 2D FLDW waveguides. Moving on, we categorized various types of photonic Floquet TIs in FLDW waveguides, including Chern-type Floquet TIs, anomalous Floquet TIs, chain-driven Floquet TIs, topological Anderson insulators, 2D topological pump, photonic TIs in synthetic dimensions, and fractal Floquet TIs. Additionally, we explored the emerging field of non-Hermitian topology, which challenges traditional notions of topology and is a forefront area of research in topological optics. We examined the intriguing physical effects resulting from the interplay of nonlinearity and topology, such as nonlinearity-induced photonic TIs, Floquet solitons, quantized nonlinear Thouless pumping, and topological edge solitons. Finally, we introduce the recent advancements about topological quantum photonics in FLDW photonic waveguides, such as topological quantum walk, topological quantum interference, non-Abelian Thouless pumping and 3D non-Abelian quantum holonomy.

Regarding future prospects, it has been firmly believed that FLDW technology, with its outstanding 3D processing capabilities, will significantly advance and revolutionize topological photonics, influencing both fundamental physics and practical applications. In terms of fundamental physics, FLDW technology offers a unique opportunity to explore new topological phenomena. For instance, it enables the realization of higher-order topological states in higher-dimensional photonic systems. Overcoming current limitations may involve utilizing synthetic dimensions in lower-dimensional photonic systems to mimic the topological behaviors found in higher dimensions. In terms of waveguide fabrication, the loss associated with FLDW waveguides is a critical issue, as the refractive index of waveguides and the long propagation distances of light will bring significant losses. Enhancements in fabrication technology and the doping of solid materials are expected to increase the refractive index difference, thereby reduce waveguide losses. Regarding potential applications, FLDW photonic topological waveguides hold great promise in areas such as topological quantum computation. Addressing how to utilize topological structures to enhance the resilience of quantum systems against interference is an important challenge. Additionally, the ability of photonic TIs to manipulate light paths while being robust against defects and disorder makes them vital for the development of integrated photonic devices. We expect that topological photonics, particularly driven by FLDW technology, will continue to attract researchers in the field, leading to a new era of discovery and innovation.

Responses