Photovoltaic bioelectronics merging biology with new generation semiconductors and light in biophotovoltaics photobiomodulation and biosensing

Introduction

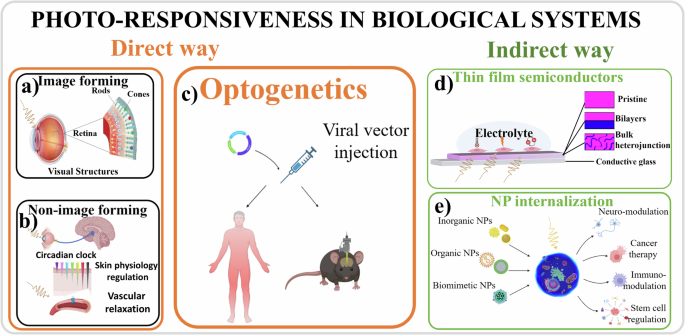

Understanding the interaction between light and biological materials has garnered significant interest due to its diverse applications in fields like medicine, biotechnology, biosensing, and bioelectronics. Light can stimulate cells either directly through naturally occurring opto-responsive proteins, such as opsins, or indirectly via non-biological materials, including thin films and nanoparticles (NPs). This interaction can be used to elicit cellular responses and has been foundational to the development of medical technologies like microscopes and X-rays. In particular, direct light stimulation can affect various tissues beyond the eye, such as the skin, blood vessels, and brain, through processes like melanogenesis, photorelaxation, and circadian rhythm regulation.

Semiconductors, being sensitive to light, can work as transducers for optical stimulation of biological entities, such as biomolecules, cells or tissues. Their properties can enable light-mediated stimulation, sensing, monitoring, and control of living systems. Currently, among semiconductors, silicon stands out as the most established technology for bioelectronics with notable applications such as photostimulation of neurons in mice1, artificial retina implantation in both humans2,3 (with clinical approval already achieved4) and animal models5 and implantable microdevice for deep tissue neuromodulation and measurement6. However, its inherent stiffness limits its widespread applicability, especially where flexibility is a requirement.

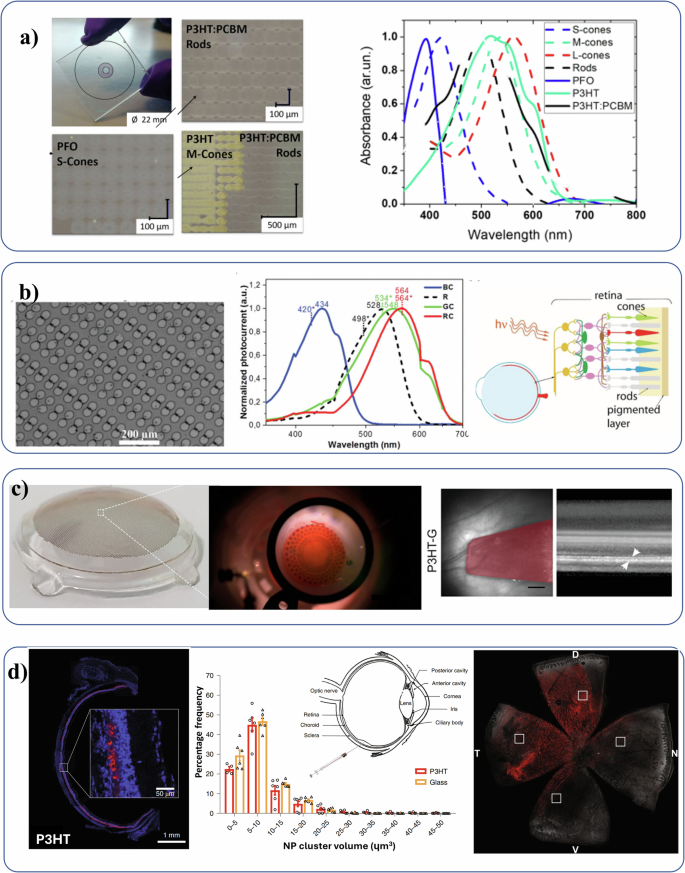

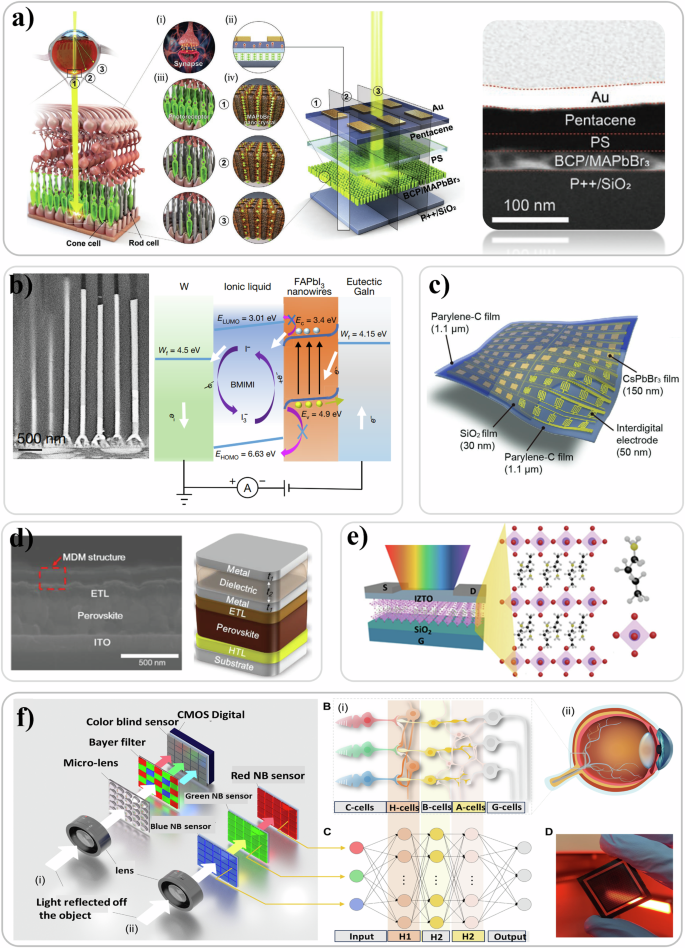

New generation semiconductors such as organic semiconductors (OSCs) share the advantages of traditional semiconductors in terms of electrical interaction with light, and polymer materials in terms of flexibility, while also offering advantages in the biological realm. OSCs show the unique capability to operate in biological aqueous electrolyte solutions conducting both electrons and ions7,8 thus bridging the typical transport mechanisms of biological systems, based on ionic transport, with the electron-based conduction of standard electronic devices. These advantages have led to their use in novel applications, including implantable artificial retinas in various animal models9,10, light stimulation of biological cells with OSC platforms11,12,13 and light-based biosensing applications14,15. OSCs, in their polymer form, can be deposited as films or even in small pixels with techniques such as ink jet printing and interfaced with biological systems16. Polymers have also been used in NP form, which are directly injectable either on the surface or inside living cells or tissues. Applications include retinas of mice17, light modulation of biological cells18 and biosensing and bio-detection (e.g. molecules, whole bacteria)19,20,21. Dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs), with their high sensitivity and electrical autonomy, are particularly promising for light-mediated biosensing applications22,23. Furthermore, a modified version of the DSSC architecture was the inspiration for developing organic semiconductor-based artificial retina devices16. Drawing inspiration from the human retina’s color perception and neuromorphic processing, even perovskite semiconductors were used for fabricating a narrowband power-free panchromatic imaging sensors based on R/G/B photodetectors without the need for complex optical filters24, or even R/G/B with the addition of either a broadband white perovskite sensor25 or a UV one26, and hemispherical nanowire array for biomimetic photosensing27,28. Although their stability in aqueous biological environments29,30,31, and potential toxicity remain challenging for widespread applicability and implantation, perovskites are known for their high efficiency in optoelectronics, offer exciting opportunities for future advancements in bio-photovoltaics and biosensing applications32,33,34.

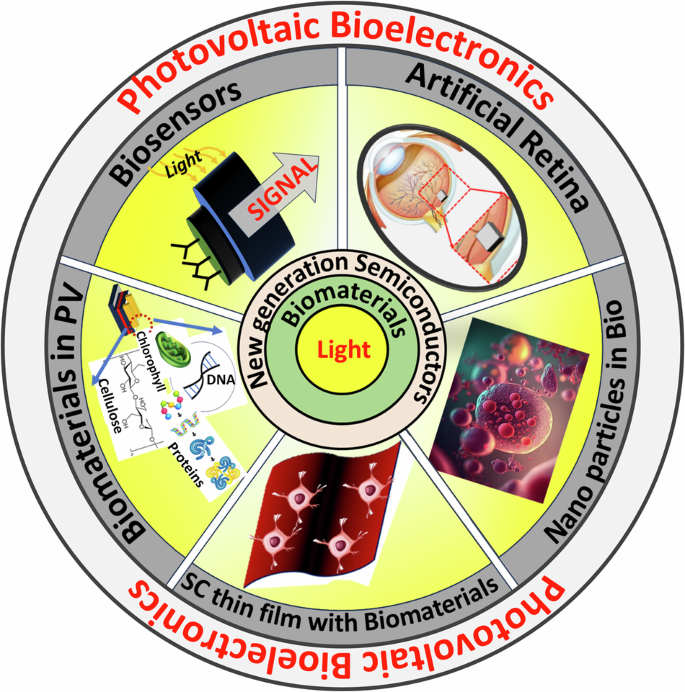

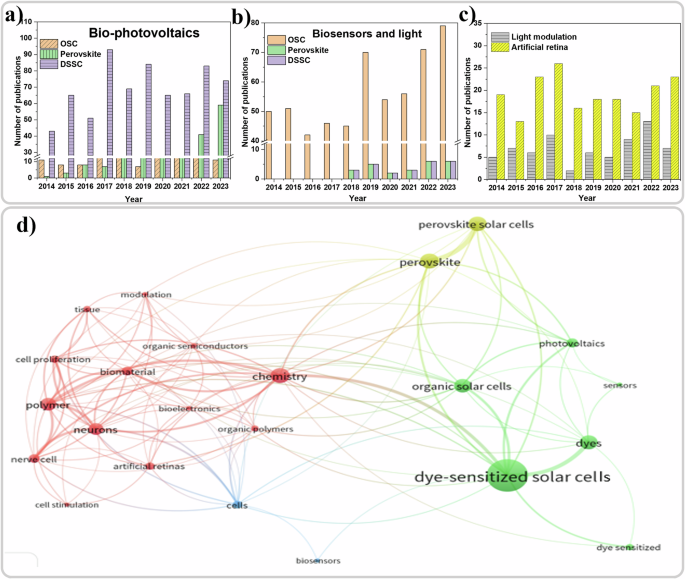

This review summarizes, as schematized in Fig. 1, the recent research progress of the new generation semiconductor photovoltaics (PV) in (i) biomaterial incorporated photovoltaics, (ii) light mediated bio-applications, iii) light-based biosensing applications, and (iv) artificial retina devices. Differently from previous reviews on biosensors that predominantly concentrated on a specific type of semiconductor35,36,37 or on a single biosensing application38,39, our focus herein is on the light-mediated bio-applications of new generation semiconductors, i.e. OSCs, DSSCs, and perovskites. We explore the integration of biomaterials into these device stacks for improved performance, modulation, and potential use in vision applications, including artificial retinas.

The interaction of light with biomaterials and new generation semiconductors is a dynamic field of research with numerous applications in various domains, such as biosensing, bio-photovoltaics, and biomedicine.

We begin the review by providing an overview of the field of photovoltaic bioelectronics, followed by a discussion on the incorporation of biomaterials into various photovoltaic technologies including OSCs, perovskites, and DSSCs, aimed at enhancing or modulating the current-voltage performance under illumination. In biophotovoltaics, the incorporated biomaterials are mostly inert, so we explore the basics of interaction between light, biological systems and new generation semiconductors. This section specifically spotlights the use of light for sensing and photo-stimulation in biological systems, focusing on interaction and transduction mechanisms of OSCs with biological materials, along with testing approaches, biocompatibility, and illumination schemes. Additionally, we also examine the photobiomodulation of behavior of living systems with OSCs. Furthermore, we explore biosensing applications of new generation semiconductors (OSCs, perovskites, and DSSCs) in light based biosensing. The subsequent section delves into the application of new generation semiconductors particularly OSCs, and perovskites, in the field of artificial retinas and vision applications, before finishing with the outlook and conclusions.

Overview

Bioelectronics is the field focused on developing electronic interfaces designed to monitor or regulate biological processes40. Photovoltaic bioelectronics, where biology, semiconductor technology and current/voltage responses to light come together, holds transformative potential not only in the research and development arena but also for future clinical applications. Bio-integrated PV devices, such as self-powered implantable biosensors, offer new approaches to healthcare, including continuous health monitoring powered by harvesting light, as well as advanced therapies that rely on non-invasive light as trigger or modulation. In fact, implantable biosensors powered by photovoltaic cells could harness ambient light41 or body heat to continuously monitor vital metrics, such as glucose levels in diabetic patients or cardiac activity, eliminating the need for invasive procedures or battery replacements42. These devices could enable real-time feedback and early medical intervention, significantly enhancing patient care43. Additionally, light-mediated bio-response modulation presents opportunities for precise drug delivery and non-invasive therapies. Photovoltaic systems can be engineered to trigger targeted drug release in response to specific wavelengths of light, providing localized treatment with reduced systemic side effects, particularly in oncology44. Similarly, optogenetics-based neuromodulation, where light-responsive materials interact with neural tissues to control neuronal activity, could lead to innovative treatments for conditions like epilepsy or chronic pain45, without the need for invasive electrodes46.

A prime example of PV bioelectronics is represented by devices that aim to mimic, restore or augment vision. Various implantable systems have been developed for clinical studies in humans, including Argus II47, Alpha IMS48, PRIMA bionic system49, EPIRET350, IRIS V251, Suprachoroidal prosthesis52, and Subretinal prosthesis51. These implants aim to restore partial vision in patients with end-stage disease who are either completely blind or have light perception without the ability to localize it. Most of these devices include a light-capturing component, either an external camera or an intraocular photodiode array, which communicates to an electrode array to stimulate retinal neurons, primarily in the inner retina. By electrically activating the remaining neurons, the implants create a visual perception, partially substituting the lost photoreceptor function with artificial vision48. PRIMA bionic system49 and Alpha IMS48 stand out as using silicon for the photodiode arrays in one of the implants. The biocompatibility, electrical safety and targeted location of the artificial silicon retina within the subretinal space has been reported in animal studies3,53,54,55. Subsequently, the safety of a microphotodiode array implants has also been shown in human clinical trials2,56. OSCs, on the other hand, have been implanted in animals such as rats57 only. POLYRETINA consisting of 10,498 photovoltaic pixels with active components made of OSCs on a polydimethylsiloxane PDMS substrate distributed over an active area of 13 mm in diameter58 has been implanted in Göttingen minipigs. These devices have restored light-evoked cortical responses in blind animals at safe irradiance levels, indicating that these OSC materials hold the potential for achieving artificial vision in totally blind patients affected by retinitis pigmentosa in the future. More recently, OSCs in the form of polymer NP, have been subretinally injected into blind mice retinas (sometimes referred to as liquid retina prothesis) restoring visual activities for at least 8 months after single injection17,59. These innovations have the potential to deliver safer solutions, not requiring invasive surgical procedures. In the arena of vision, perovskite semiconductors have been used to develop narrowband power-free panchromatic image sensors24,25,26 and hemispherical retinas made of a high-density array of nanowires mimicking the photoreceptors on a human retina27,28. Rather than for restoring vision via implantation or injection, due to their current poor stability and cytotoxicity, this exciting perovskite research has focused instead on advanced biomimetic applications28.

Such advancements underscore the huge potential of photovoltaic bioelectronics to revolutionize diagnostics, continuous monitoring, and therapeutic interventions. However, as clearly apparent from the artificial retina examples, several challenges must be addressed for its broader adoption, particularly in understanding the interactions between new-generation semiconductors and biological materials. Ensuring long-term biocompatibility and stability, especially during in vivo testing60, is critical for developing reliable systems. Biocompatibility will confirm the ability of the device to perform its desired function when in contact with biological cells/tissues without producing any adverse effects on the latter. Conducting in vitro biocompatibility assessments on semiconductor surfaces is crucial for understanding cytotoxicity and the possibility of safe in vivo applications. Biocompatibility tests on silicon substrates with various in vitro cell cultures, such as C2C12 mouse myoblasts61, rat neuronal cells (B50)62, and mouse fibroblasts (SC-1)63, have shown that cell viability remains above 80%61 on the semiconductor surface even after 7 days, confirming the non-cytotoxic nature of silicon63. The biocompatibility of OSCs, using primary human retinal cell cultures by systematic measurement of both cell viability and morphological analysis of retinal ganglion cell neurite elongation over time, was investigated by Sherwood et al.64. Six materials were deemed promising candidates for novel retinal prostheses. The authors note that the vast majority of studies examining biocompatibility use animal tissue rather than human tissue given the difficulty of obtaining human samples. In addition, cell survival and death mechanisms of neurons are different to those of non-neuronal cell types65. Cell death and cell survival mechanisms can even vary between different types of neurons66, and selection of a biological tissue source which matches the target tissue of the proposed therapeutic application is critical for its effectiveness. Subretinal injections of polymer NPs in rat models did not trigger trophic or pro-inflammatory responses, further demonstrating the biocompatibility of polymer-based NPs17. Cytotoxicity studies on perovskites have been carried out using human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cells (A549), SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells, and murine hippocampal neurons67. However, methylammonium lead iodide (MAPbI3) perovskites exhibited dose- and time-dependent toxicity in both SH-SY5Y and hippocampal neurons, causing plasma membrane damage and inducing cell death.

Even if the semiconductor shows in vitro biocompatibility, during in vivo testing interface between rigid semiconductor surfaces and soft biological tissues often creates mechanical mismatches, leading to fibrotic scarring and the formation of physical barriers that impair device functionality68. In case of OSCs, even though the semiconductor is soft, mechanical mismatches with the biological tissue can occur which can lead to adverse fibrotic scarring depending on the nature of the substrate10. To mitigate these effects while maintaining device functionality, advanced materials and design strategies are essential, with an emphasis on flexibility, bioinertness, softness, biocompatible substrates, and surface modifications that can enhance biocompatibility and reduce the risk of chronic immune reactions69. In addition to biocompatibility concerns of the semiconductor, the long-term stability of implanted devices in biological environments poses another significant barrier to the commercialization of new-generation semiconductors for in vivo applications.

Table 1 compares the properties of biotic living tissues/cells and the semiconductors they interface with, subject of this review: OSCs (in both film and NP form), perovskite, DSSCs, also silicon for comparison. The table clearly shows that certain physical properties, such as physical state, mechanical, and charge carriers types in OSC, more closely resemble those of biotic living tissues and cells compared to conventional semiconductors such as silicon. For example, Young’s modulus is many orders of magnitude smaller in OSCs compared to silicon, coming closer to that of living systems. OSCs are also able to conduct ions and their morphology can be textured to increase surface area and the adhesion/interaction with biological systems, offering distinct advantages over other semiconductors. DSSCs are especially apt at conducting both ions and charge carriers at their liquid/solid interfaces with high surface area resulting from the mesoporous nature of one of their key layers. Furthermore, they are able to operate in aqueous environment, even though stability over time should be investigated further. Although sharing similar fabrication processes to those of OSCs, perovskites have advantages related to the more efficient conversion of incident optical to electrical power (i.e. in performance). However, perovskites currently possess severe limitations due to the toxicity of their main formulations and lack of stability in aqueous media: these issues should be addressed, developing less toxic and more stable formulations in the future to unlock the potential of these new semiconductors for photovoltaic bioelectronics applications in vivo. Table 1 also provides some avenues for improving biocompatibility as well as the maturity and range of applications that have been developed for the different semiconductor devices as already highlighted at the beginning of this section.

Biophotovoltaics

Biomaterials in organic photovoltaics

The inherent chemical resemblance between OSCs and natural biological materials and compounds, owing to their shared conjugated carbon structures, underscores the potential for integrating biomaterials into OSC-based devices and materials for biomedical applications. This resemblance to biological molecules not only enhances the compatibility and versatility of OSCs but also unlocks new pathways for innovative biomedical and photovoltaic device applications70,71. The unique printability of OSCs, coupled with their ability to be finely tuned for optoelectronic properties through chemical design72 further strengthens their potential in these diverse applications.

Researchers are actively looking for bio-derived materials in the photovoltaic stack that can replace conventional materials to modulate and even improve the photo response of organic photovoltaics (OPV)73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82. Millions of years of evolution of living organisms have led to the design, synthesis, and utilization of materials with unique optoelectronic properties83. Biomaterials are naturally occurring84 and hence the incorporation of these materials in OPV can lead to more environmentally friendly devices. While the primary objective of this research has focused on identifying natural alternatives to synthetic materials in PV devices, the significance of studies in this domain extends far beyond. Through these investigations, valuable insights have emerged regarding the integration of biological materials with OSCs and the development of biohybrid devices aimed at modulating the photo response of photodiodes. Such advancements are fundamental for biosensing applications, underscoring the multifaceted impact of this research field. Plants, animals, and micro-organisms, are the main source of biomaterials that have been incorporated either in the active layer, charge transporting layers, substrates, light trapping layers, or electrodes of OPV85 as summarized in Table 2.

The biomaterials that are being utilized in the bulk of the active layer of OPV are proteins86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94, DNA95 and natural dyes96,97. Photosystem I (PSI) of the photosynthetic process that is able to convert photons into electrons with a nearly 100% quantum efficiency98, is stable and abundant and can be easily isolated and incorporated into the OPV device architecture as demonstrated by Das et al.79. PSI complex extracted from young spinach leaves was spin coated onto indium tin oxide (ITO) glass coated with the amino acid before a C60 layer was added on top by Ajeian’s86 group in 2017 for light harvesting, resulting in a power conversion efficiency (PCE) of 0.5%. It was demonstrated that DNA attached with fullerene, has a significant potential as key structural element as a structural scaffold in the bulk of the active layer. The devices reproducibly exhibited photovoltages of 670 mV95. Natural dyes have been explored as potential active materials in organic solar cells due to their low cost, renewable nature, and environmental friendliness. These dyes are typically extracted from plant materials or other natural sources and have been found to exhibit promising light-absorbing and electron-donating properties99,100. Chlorophyll, being one of the most abundant pigment which can be extracted from plants, has been coupled with P3HT97, and has shown to work as an electron acceptor in PV cells delivering a PCE of 1.48%.

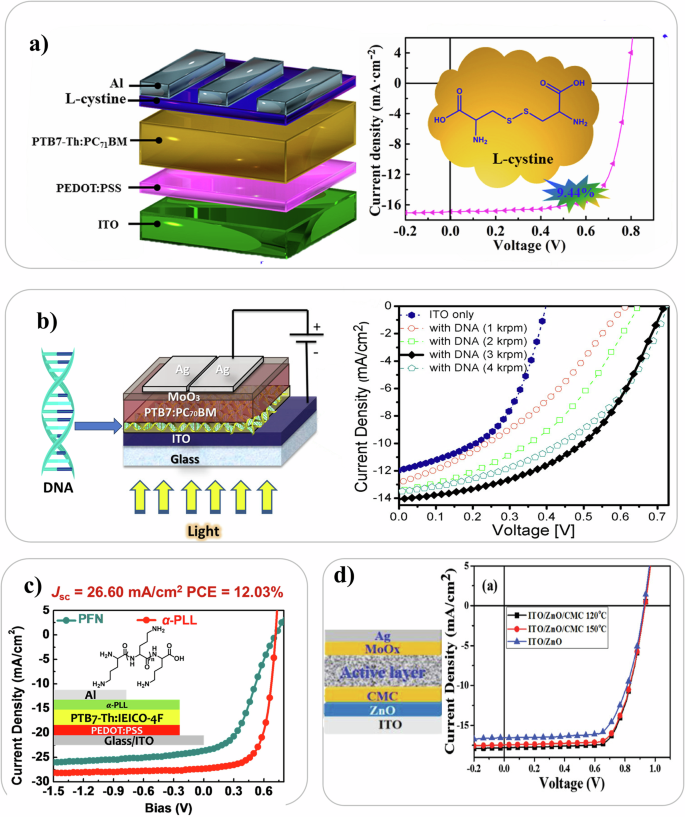

Notable cases of incorporation of biomaterials for modifying the interlayers between electrodes and the semiconductor in OPV are illustrated in Fig. 2. Biomaterials such as amino acids101,102,103,104,105,106, DNA107,108,109,110,111, polypeptides112,113,114, polysaccharides115,116,117,118,119, and catecholamine120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128 can improve charge transport in OSCs. Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins that make them ideal for assembly since they can assemble, and form ordered structures. One of the most promising amino acids for use as an interlayer in OPV is arginine. In 2020, Li et al. successfully introduced L-arginine as an ETL by spin coating it on ITO in an inverted organic solar cell. The PCE improved by a factor of 4 compared to ITO-only devices, reaching a PCE of 9% as a result of improved work function and increased interface conductivity101. Recently in 2023, a group of researchers used L-cystine as ETL improving efficiency by 68% compared to the reference device129. DNA exhibits excellent thermal stability up to 140 °C in its solid form130 and easy tunability via chemical and physical treatments. Dagar et al. were the first to employ DNA nanolayers by spin coating these over ITO determining an enhancement of the electron extraction capabilities of the cells108. DNA led to strong improvements in rectifying behavior (by 2 orders of magnitude with rectifying ratios larger than 103) and in photovoltaic parameters like the open-circuit voltage (VOC from 0.39 to 0.73 V) and power conversion efficiencies (PCEs from ∼2 to ∼5%)108. When coupled with inorganic interlayers over ITO/ZnO-NPs107 power conversion efficiency improved from 7.2% to 8.5% due to a lowering of the work function caused by DNA and its capability of imprinting a different long range order on photoactive blend110. DNA has in fact been used as a structural scaffold for supramolecular chromophore assemblies95. Also, polypeptides, which are biodegradable polymers composed of amino acids, have been incorporated in OPV. α- poly-lysine was the first polypeptide used as electron extraction layer to improve charge transport in fullerene-free OPV113. When used as an overlayer in ITO/ZnO ETLs, the PCE improved from 7.23% to 8.32% due to the lowering of the work function by 0.06 eV resulting from dipole formation arising from the arrangements of amino groups of poly-lysine112. In 2020, researchers used carboxymethyl cellulose sodium as a co-modifying layer with ZnO for the transfer and collection of electrons in OPV and the best device delivered a PCE of 11.96%. Again, this interlayer lowered the work function of ITO116. The presence of functional groups in the bio-derived materials, and their tendency to assemble, can be exploited to improve energy level alignment, morphology of the photoactive layer, and dissociation of excitons in polarons. Among these biomaterials, overlayers of amino acids, DNA, and catecholamine are the most promising.

a Device geometry of OPV with L-cystine as ETL. The JV curve is displayed. Reproduced with permission from ref. 129. b The device structure of an organic solar cell incorporated with DNA nano layer and the device performance (JV curves) variation with respect to the spin speed of DNA layer deposition. Reproduced with permission from ref. 108. c JV curve comparison of an OPV device incorporated with Polyamino acid and Poly [(9,9-bis(3′-(N,N-dimethylamino)propyl)-2,7-fluorene)-alt-2,7-(9,9–dioctylfluorene)] (PFN) as electron extraction layer. Reproduced with permission from ref. 113. d Carboxymethyl-cellulose (CMC) based OPV device. The effect of different annealing temperature of ITO/ZnO/CMC on the JV curve compared with ITO/ZnO device. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0116.

Biomaterials in perovskite photovoltaics

Perovskite solar cells (PSC) are new generation photovoltaic devices that use materials with a crystal structure similar to the mineral perovskite for harvesting light. They are one of the most promising PV technologies due to high photo conversion efficiency and low cost high-throughput fabrication processes. The solution processibility, band gap tuning, economic viability, and high efficiency are some of the qualities of the perovskites which make them desirable. Even though it is a highly promising and growing technology, there are still limited choices of perovskite materials, and their toxicity and instability remain challenging issues to be solved. A typical PSC comprises of five layers131,132 which are (i) transparent electrode, e.g., transparent conducting oxide (TCO)-coated glass/plastic, (ii) electron transport layer, e.g., a compact metal oxide layer (TiO2 or SnO2), (iii) a poly-crystalline metal halide perovskite layer as absorbing layer, (iv) an organic hole transport layer (HTL), and (v) a metallic top electrode.

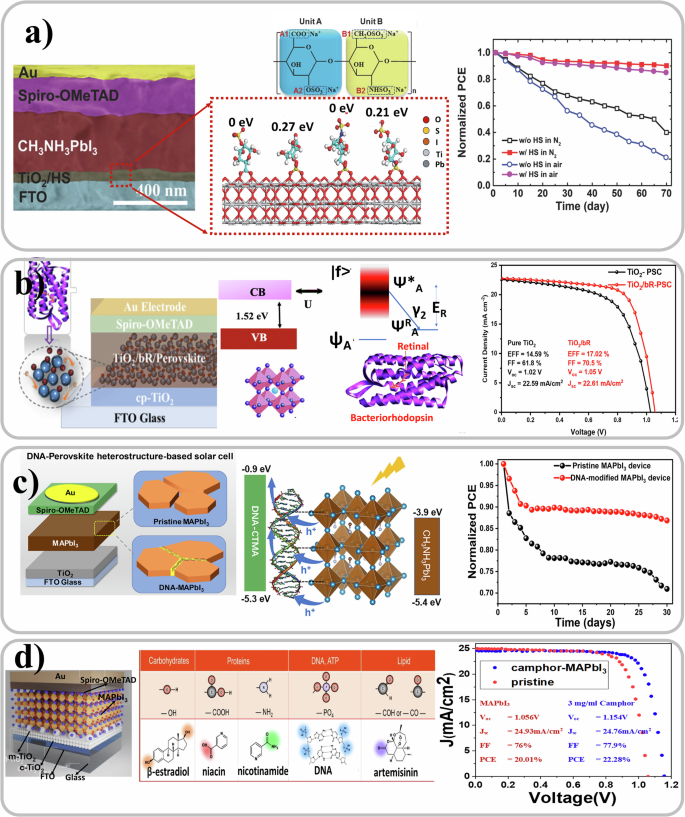

Even though perovskite materials are highly sensitive to environmental/water-led degradation, there are some reports of incorporation of biomaterials133,134 in the PV device stack in the literature. Biomaterials have been introduced at the charge transport layer and semiconductor interfaces as well as in their bulk to improve both efficiency and stability as tabulated in Table 3. Amino acids135,136,137, DNA138, and cellulose derivatives139,140 have been used in the active semiconductor. Biomaterials such as amino acids135,141,142,143,144, proteins145, DNA146,147, catecholamine148, dopamine149,150,151,152,153, and polydopamines154,155,156,157 have been incorporated at the charge transport layer interfaces with perovskite. And recently, “reverse micelle” like bio-structures have also been explored in perovskites134. Molecules with ambipolar moieties and other types of bio-derived materials such as capsaicin, betulin and biopolymer heparin sodium (HS) salt, have been shown to be effective interlayers. These materials improved the perovskite’s morphology, defect passivation, and enhanced the charge extraction due to the modified transport layer/perovskite heterojunction158. These modifications are accompanied by simultaneous increase in device stability, which is essential for scaling up of this technology. Bio-derived materials with polar groups, such as amino acids and catecholamines, have been mostly implemented to mitigate intrinsic instability and to modify the TiO2/perovskite heterojunction interfaces, even enhancing charge extraction77,159. You et al. demonstrated that biopolymer heparin interlayers anchoring TiO2 and MAPbI3 enhanced trap passivation and device stability. The PCE improved from 17.20% to 20.10% when this interlayer was introduced in the device stack. Furthermore hysteresis was suppressed and the PCE maintained more than 80 percent of the initial value even after 70 days compared to 10 days in case of devices without the interlayer160 as shown in Fig. 3a. In 2021 a group of researchers used a non-toxic and sustainable forest based biomaterial called betulin161 in PSCs improving the PCE from 19.14% to 21.15%. Proteins have been investigated as potential charge transport layers in perovskite solar cells due to their unique electronic properties, biocompatibility, and low-cost fabrication methods. As depicted in Fig. 3b Das et al. in 2019 reported on how to enhance the efficiency of PSCs from 14.59% to 17.02% through protein functionalization of the TiO2 electrode145. Similar to OSCs, DNA has also been used in PSCs as an interlayer. In fact, in 2019 researchers showed it was possible to increase the PCE up to 20.63% as well as the stability of solar cells with DNA-modified perovskite layers (Fig. 3c)138. More recently, Wu et al. utilized perovskite semiconductors as a platform to investigate whether specific biomolecules can modulate the lattice structure. Their study revealed a unique mechanism for stabilizing the metastable perovskite lattice, achieving a PCE of over 22% (Fig. 3d). Through systematic experimentation with three tiers of biomolecules incorporated into the perovskite, they unveiled insights into a fundamental mechanism underlying the formation of a “reverse-micelle” structure. A comprehensive exploration of a diverse array of biomolecules uncovered guiding principles for the selection of suitable biomolecules, effectively extending the classic emulsion theory to these hybrid systems. Furthermore, this research offered a fresh perspective on engineering synthetic materials, showcasing the potential for leveraging biological principles to enhance semiconductor properties134.

a Cross section of MAPbI3 perovskite solar cell with heparin sodium interlayer bridging TiO2 and perovskite layer. The functional groups attached to the TiO2 surface and chemical structure of heparin sodium salt with two repeating units are represented in the middle. The PCE plot shows that the solar cells with HS interlayer were more stable than the ones without. Reproduced with permission from ref. 160. b The image of bacteriorhodopsin functionalized TiO2 in the MAPbI3 solar cells stack is shown. This incorporation had improved the efficiency of the solar cell as shown in the JV graph. Reproduced with permission from ref. 145. c A DNA modified MAPbI3 perovskite solar cell with improved stability as shown in the PCE plot. Reproduced with permission from ref. 138. d Down-selection of biomolecules to assemble “reverse micelle” with perovskites. Reproduced with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 ref. 134.

Biomaterials have not only been incorporated at the interfaces of the solar cell stack but in the bulk of the perovskite film134. Hou et al. in 2019 demonstrated a core–shell heterostructure of perovskite wrapped by cetyltrimethylammonium chloride modified DNA to incorporate in the device stack. Such a design resulted in enhanced extraction and transport of holes in the bio-photovoltaic device and boosted the efficiency from 18.43% to 20.63%138. Amino acids have also been found to passivate the surface defects in perovskite materials, which can reduce non-radiative recombination and improve charge carrier lifetimes162. In 2020, Zhang et al. incorporated the amino acid L-lysine with two amino and one carboxyl groups as a chemical additive in the CsPbBr3 perovskite films to simultaneously anchor the uncoordinated Pb2+ (Cs+) and halogen ion defects. Furthermore grain size of CsPbBr3 perovskite is boosted from 688 nm to over 1000 nm as a result of the decreased nucleation rate and the sufficient growth of perovskite135. Amino acids have also been used to modify the surface of TiO2141,142 at the TiO2/MAPbI3 heterojunction improving cell performance. In 2023, Chen et al. reported the use an amino acid molecule to improve charge extraction of the ETL layer and the champion device had an efficiency of 24.71% and good stability163.

Biomaterials in dye-sensitized photovoltaics

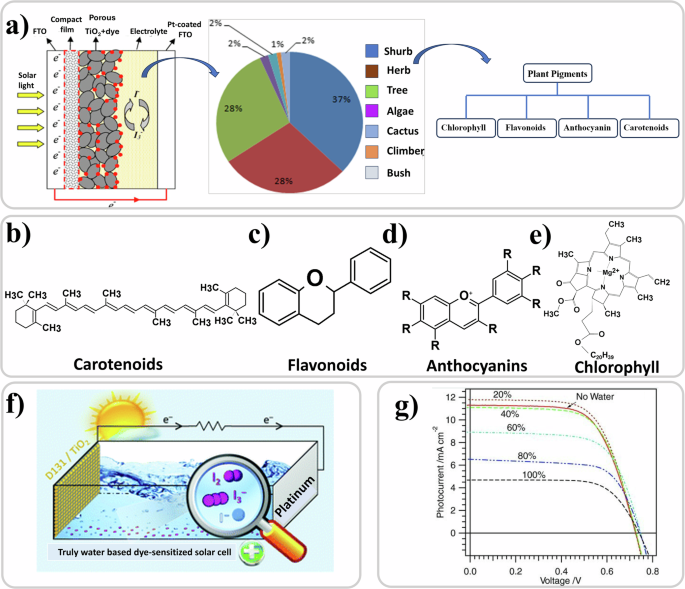

DSSCs164,165,166,167,168 are an interesting solar cell technology because of their simple preparation methodology, low toxicity, and the presence of an electrolyte as core constituent. The semi flexibility169 and semi transparency170 of the technology allows for a wide range of applications. It consists of a mesoporous nanostructured wide band gap oxide semiconductor, usually TiO2, with a monolayer of photoabsorbing dye anchored to it, deposited on a transparent anode, a counter electrode with a catalytic layer, and an electrolyte solution that fills the device structure171,172,173,174,175 as shown in Fig. 4a. Electrolytes used in DSSCs, being one of their main components, can be in solid176,177,178, liquid179,180, or quasi-solid state181 forms.

a The left part of the panel shows the structure of a typical DSSC, reproduced with permission from ref. 556, the middle part of the panel shows the pie chart of percentage of plant varieties used in DSSC applications, adapted with permission from ref. 185, and the right part of the panel shows the pigments from these plant varieties used as the dye184. Chemical structure of b Carotenoids172, c Flavanoids557, d Anthocyaninis172, and e Chlorophyll172. f The structure of a truly water based DSSC. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence558. g JV curves of the aqueous electrolyte-based DSSCs according to the content of water in the electrolyte. Reproduced with permission from ref. 227.

Since the first discovery182, much research has been focused in designing and synthesizing dyes and formulating electrolytes to maximize the conversion of photons into electrons and photovoltaic performance with certified records of 14.1% achieved183. Necessarily, devices with industrial potential rely on synthetic dyes and electrolytes based on organic solvents. Historically, related to the possibility of extracting a multitude of dyes from living systems with anchoring groups that can be easily attached to the mesoporous TiO2 layer, the literature on manufacturing DSSCs where the pigment is from natural living systems, plant-based in particular, has flourished184. A recent review study has shown that 37% of these pigments have been extracted from shrubs, followed by herbs and trees which contribute to more than 50% together185 (Fig. 4a). The main pigments (Fig. 4b–e) that have been extracted from these plant sources are chlorophyll186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194, anthocyanin15,186,187,189,195,196,197,198,199,200,201, betalains202,203,204, flavonoids186,205,206, anthraquinones205, rutin205,207, and carotenoids184. Natural dyes208,209, have also been derived from other sources such as bacteria210,211,212,213,214,215,216. Table 4 reports devices with natural dyes extracted from plants with an efficiency of at least 1%. As can be noted, the efficiencies from natural pigments are way off from those achieved with synthetic ones but the fascination remains of creating a photovoltaic device with natural biological components.

A significant push for selecting and investigating natural pigments is sustainability217. The same can be said for replacing conventional glass or plastic substrates with cellulose films218. Efforts in this direction on other constituent layers of the DSSC stack have mainly focused on the electrolyte which is generally based on organic solvents. Electrolytes have been modified with incorporation of biomaterials mainly for jellification, predominantly polysaccharides such as cellulose (in a standard liquid electrolyte containing 1-methyl-3- propylimidazolium iodide (MPII))219, starch (in a polymer electrolyte)220, chitosan (polymer electrolyte)221,222, gelatin223, and with ethyl cellulose, the latter being particularly stable224. Nanocellulose was also employed as an aerogel membrane for assisting in electrolyte filling. Nadia et al. used agar-based polymer electrolytes where they investigated the effect of sodium iodide and potassium iodide on ionic conductivity, the latter resulting in higher ionic conductivity225. Instead of the typical organic solvents used in electrolytes such as 3-methoxypropionitrile or acetonitrile226, the most eco-friendly ingredient for alternatives is water (Fig. 4f). Water-based DSSCs are usually assembled using solvent mixtures with varying percentages of water. Figure 4g shows that performance of the devices is reduced with increase in the content of water227. The lowering of efficiency and stability compared to conventional organic solvents is due to the dye desorption and the poor solubility of iodine in water226. Nevertheless, the fact that 100% H2O can be used in DSSC structures is an important factor in these architectures being used in biosensors or in artificial retina concepts as illustrated in future sections.

In summary, the integration of biomaterials in OPVs, PSCs, and DSSCs pursues similar objectives but employs distinct methodologies. In OPVs, biomaterials like proteins, DNA, and natural dyes have been shown to enhance light absorption, morphology, carrier transport and extraction, with notable efficiency improvements (with relative PCE increase of 20% for protein228, 18% for DNA229, and 15% natural dye101) with the highest reported efficiencies reaching around 18.35%76. In PSCs biomaterials have been mainly used for defect passivation not only at the layer interfaces but also at the grain boundaries and to improvement in charge extraction. Examples include perovskites modified with DNA, which boosted PCEs from 18.4% to 20.6%138, heparin sodium salt, raising efficiency from 17.2% to 20.1%160, and artemisinin affecting the colloidal-crystallization dynamics and boosting the PCE from 19.3% to 22.4%134. DSSCs, on the other hand, focus on the use of natural pigments like chlorophyll and anthocyanins, which are derived from plants and offer a sustainable alternative to synthetic dyes, but with lower efficiency (around 2% with highest reported of 4.6% with chlorphyll230). Biomaterials in DSSCs are also used to modify electrolytes, incorporating cellulose, starch, and chitosan to improve device stability. While all three technologies leverage the incorporation of biomaterials for improved performance and possible sustainability, PSCs have delivered the highest efficiencies and stabilization properties, OPVs the greater modulation of performance after incorporation, focusing more on environmental impact, and DSSCs presenting the highest number of publications using natural dyes (at the cost of lower efficiency).

Basics of the interaction of light, biological systems and new generation semiconductors

Light for sensing and photo-stimulation in biological systems

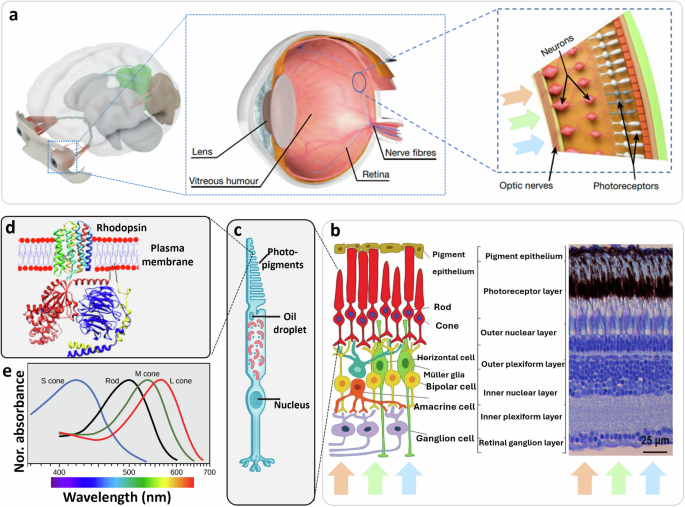

Light has always been a widely used tool for the control and stimulation of cells and living systems. For example, light was first used to control biological systems such as muscle tissue in 1891231, and ganglion cells of Aplysia californica in 1968232, while in 1971 selective stimulation of neurons via laser radiation was carried out233. Research has progressed tremendously since then234,235,236,237,238. The reason is that light can, depending on wavelength, selectively be absorbed, or propagated through different biological tissues and membranes. Thus, it exerts its effect without a direct physical contact that could damage the biological entity under investigation239,240,241. With respect to the standard approaches (e.g., electrical, chemical, and mechanical), light stimulation shows several advantages: it not only is a contactless probe, but also a probe that can be shaped in desired patterns to target specific areas. Its high selectivity and spatio-temporal resolution enables the targeting of even single cells and subcellular components242. In recent years, different techniques exploiting the interaction of light with biological systems have been demonstrated, showing an increasing trend towards the optical approach for stimulation and sensing of living systems. The methods for light interaction or light manipulation of biological systems are classified in two categories243:

-

i.

Endogenous light-sensitive methods: exploiting photoactive mediators that are naturally expressed by or located within the living systems, such as those in the opsin family—proteins that bind to light-reactive chemicals involved in vision, phototaxis, circadian rhythms, and other light-mediated responses in organisms244. For example, it is well known that light acts directly in the eye. Photoreceptive cells, namely cones and rods, respond to light differently depending on their structure and the opsins they carry (Fig. 5a). It is less known, however, that light also plays a direct role in the skin245,246 and in other unconventional tissues where specific opsins can respond to light247, such as in blood vessels248, in white adipose tissue249, and in the brain250,251. In these extraocular sites, the capability to detect light is not utilized for image capture but serves other functions, such as ultraviolet radiation-induced melanogenesis in the skin252, photorelaxation of smooth muscle cells in blood vessel walls248 and airways253, reduction in lipid content and adipokines secretion by adipocytes249, and regulation of circadian rhythms in the brain (Fig. 5b). Moreover, the setting of the circadian clock has also been attributed to specialized “intrinsically photosensitive” cells present in the eye, distinct from cones and rods, which are a subset of retinal ganglion cells254,255, and sphincter muscle cells of the iris that control pupillary constriction256,257. In addition to naturally occurring photo responsive molecules, advances in (opto)genetics (Fig. 5c) based on molecular biology and biotechnology258 have allowed the introduction of photo responsive molecules inside cells259,260. With these new approaches, degenerated retinal cells can partially recover their functions, enabling photo response261.

Fig. 5: Schematic illustration of the two different ways through which light can affect cell behavior.

In the direct way, photo responsive proteins physiologically present in a cell, that are image-forming (a), and non-image forming (b), or transfected with a viral vector (c), can respond directly to light stimuli. In the indirect way, photo responsive materials present in the form of a thin film outside the cells (d) or in the form of NPs inside the cells (e), are responsible for absorbing light, transducing the excitation to the biological system thus affecting its response (created with BioRender.com).

-

ii.

Exogenous light-sensitive methods: converting the light excitation into electrical, chemical, or thermal stimuli associated with the presence of non-biological materials, either in close proximity (Fig. 5d), or integrated within the cell through the injection of NPs (Fig. 5e), enabling them to respond to incident light262. This stimulus can induce ionic or chemical changes in the cellular microenvironment, thus modulating the activity of responsive biomolecules such as voltage-gated ionic channels. The integration of these new materials with biological systems has enabled light to activate and deactivate biological processes in cells that were previously not photosensitive, thereby providing a degree of control over these processes through light. For instance, the proliferation rate of a neuroblastoma cell line cultured on polymer semiconductors was significantly influenced by periodic light pulses directed onto the system13. These approaches expand the possibility of controlling and modulating cellular responses, as optical stimulation addresses two important challenges: spatial resolution and response specificity. This ability of light to interact with biomaterials linked with non-biological materials has various applications, including modulation of the performance of photovoltaic (PV) devices, bioelectronics, and biosensing.

-

i.

Photobiomodulation is a well-established endogenous light stimulation technique for therapeutic targets263. By activating naturally expressed light-sensitive proteins (photons of light are absorbed by chromophore present within tissues) this technique induces beneficial effects on cells and tissues (e.g., wound healing and tissue regeneration264) by generating photochemical reactions employing low-power density lasers or light-emitting diodes (LEDs)265. Light-sensitive proteins present in biological systems are rhodopsin in the retina photoreceptor cells, and also other opsins outside the eye, such as phytochrome in plants, and bacteriorhodopsin and bacteriophytochromes in some bacteria. While photobiomodulation exploits the direct interaction of light radiation with cells and tissues, optogenetics is an endogenous optical approach based on the engineering design of light-sensitive proteins and photoactive molecules266. Although photosensitive complex, usually introduced in living cells through viral transfection, are necessary, the biological processes in response to light are generated by the cell itself. Optogenetics is a very promising approach. However, several ethical and safety issues related to the need of viral-gene transfer strongly limit in vivo therapeutic applications.

-

ii.

Due to the relatively limited existence and non-specific interaction between light and biological systems with notable exceptions such as the retina and photosynthetic units – research has focused on identifying and developing photosensitive transducers designed to interact optoelectronically with biological systems. Examples of these exogenous photoabsorbers267, either organic or inorganic, are micro and NPs268,269, quantum dots (QDs)270, and semiconductors271. Rigid semiconductor interfaces such as monolithic silicon-based devices have been recently used for high spatiotemporal resolution photostimulation. These innovations enhance the precision and control of light-based stimulation in biological tissues, with potential applications in neuroscience and medical therapies272. Despite ongoing efforts, concerns exist on the biocompatibility of inorganic exogenous materials used in photo-stimulation due to the intrinsic material stiffness, the possible cellular damage caused by the exposure to an excessive required light intensity and the necessity of an externally applied bias via electrical wiring which leads to tissue heating273,274 and cellular injury275,276. The new generation of thin-film semiconductors emerges as particularly promising due to their potential for interfacing with biological materials with good biocompatibility at both the mechanical and electronic levels277,278 (see previous section). These encouraging characteristics position these semiconductors as noteworthy subjects for detailed examination in the upcoming sections.

Interaction and transduction mechanisms between organic semiconductors and biological matter/cells

The fundamental component of the semiconductor’s interface with biological systems is the photoactive material acting as both absorber of light and transducer. OSCs have a broad range of physical and chemical features that can influence cell growth and function. The biological materials are very sensitive to the environment, therefore it is important to make sure of the fabrication of semiconductors in sterile conditions which can ensure the supporting/interfacing material do not adversely affect (but even improve, sustain, or enhance) biological standard behavior279. Surface properties of materials, such as roughness and surface-energy, can influence protein adsorption from a solution occurring within seconds. Adsorbed proteins consequently contribute to cell-substrate interactions280.

Biocompatibility is a crucial aspect to consider when working in bioelectronics, at macro-, micro-, and nano-scale levels. The forefront of bioelectronics based on OSCs is focused on the control of cell adhesion, growth, and differentiation as well as the stimulation and inhibition of bioelectrical signals. First, for each material used in bio-interfaces, it is vital to take into account the level of purity as well as the sterilization step to avoid potentially cytotoxic compounds and/or pathogens that can be hazardous for biological systems. Subsequently, the step of cell adhesion is an important issue that deserves consideration. In this context, not only is the type of material important, but also the characteristics of the surface, that is its topography (roughness, presence of pores, cavities), its chemical nature (surface energy and charge) and its physical characteristics (stiffness and wettability). Moreover, the material surface when utilized in vivo, is rapidly covered by adhesion proteins present in body fluids, like fibronectin and vitronectin that facilitate cell adhesion; for this reason, when working in vitro, it is necessary to mimic this adsorption step by pre-adsorbing adhesion molecules onto the material surface281.

Based on these considerations, OSCs have been proved highly suited for application in biological interfaces (at different levels of complexity, from animal cells and tissues to plant cells) because of their physical and chemical features282,283,284,285. Compare with inorganic photovoltaic material such as silicon, OSCs show soft nature, high efficiency of light absorption, tunable optical and electronic properties, and a superior capability of mixed, ionic and electronic, conductivity when interfaced with aqueous electrolyte as required in bio-hybrid interfaces286.

Biological systems primarily communicate through bioelectrical signals, which consist of ion movements (currents) and local variations in ion concentrations (potentials). In contrast, conventional electronics operate based on electron conduction. Thus, the fundamental divergence between these two domains lies in the nature of conductivity: extracellular and intracellular ionic conductivity in biology versus electronic conductivity in electronics. The interaction between OSCs and biological systems can function bidirectionally:

-

i.

As (bio)sensors, where a biological process or reaction transmits signals to an organic electronic device, thereby transducing the biological process into an electrical output.

-

ii.

As (bio)actuators, where an organic electronic device stimulates a biological process, facilitating the electrical stimulation of said process.

Conjugated polymer being inherently hydrophobic in nature, have to be prepared as NPs, such as P3HT-NPs, and have been employed in bio-photonic applications287. In 2016, a research team explored these NPs for interaction with Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK-293) cells. The NPs were observed to be internalized within the cytosol of live cells, demonstrating the potential of P3HT-NPs as light-sensitive actuators. Notably, the photophysical properties of the NPs were maintained without impairing the physiological functions of the cell18. In 2018, the same group used P3HT-NPs to modulate the intercellular Ca2+ dynamics of the same cellular line. With this method they opened the possibility of gene-less approach for studying cellular processes288. Recently, thiophene based core@shell NPs were used to photo-generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) without harmful singlet oxygen. It was showed that these NPs are fully biocompatible and can be used as exogenous photo-actuators, which can potentially operate through two different mechanisms based on charge capacitive effects and/or ROS generation inside living organisms289. Lately, porous semiconducting polymer nanoparticles have been designed and synthetized to be employed as intracellular wireless mediators for light-induced intracellular ROS production and modulation in vascular tissue290.

Concerning light-mediated exogenous methods with semiconductor thin films, they are based on the interaction of the photo-generated charges in the organic material and the living systems57. The basic idea is that the light-generated electrical charges in the film can modulate the membrane potential of a cell grown on top of it or can elicit some electrical activity in tissues placed on it. Unlike endogenous light stimulation where the focus is at the molecular scale, in exogenous stimulation the interface between the OSCs (mostly in the form of thin films) and the biological structures plays a crucial role in determining the excitation pathway. Most importantly, in light-mediated exogenous methods with bio-interfaces, OSCs show low production of heat, very specific absorption of photons because of the tuning of their optoelectronic properties, and a different range of charge transfer processes occurring with electrolytes that are useful for ionic mediated electric signaling. These interactions have been utilized, for example, in stimulation of retinal cells10 and in the modulation of ion channels in neuroblastoma cells13.

Several possible mechanisms are involved in the coupling process between optically excited OSCs and living systems. The general underlying principle is linked to the light-induced formation of long-lived excited states in the active photosensitive layer. These polaron states are responsible for interactions with the cells through the electrolytic environment present in the cleft, the narrow gap ( < 100 nm) separating the device from the cellular membrane. Immersed in electrolyte solution, OSCs convert absorbed light into heat via photothermal conversion, into electricity via photovoltaic (capacitive and reversible Faradaic) processes, and into chemical species via photocatalytic reactions271. In more detail, three different photo-stimulation mechanisms, at the OSCs/biological systems interface, proposed so far are the following242.

-

i.

Thermal coupling: light stimulation causes a local temperature to increase in the extracellular bath solution in proximity of the OSC layer. Photothermal OSCs mediated neuromodulation was demonstrated for inhibition or excitation of neuronal firing via temperature-dependent cellular membrane channels291.

-

ii.

Electrical coupling: light induces an electrical phenomenon, Faradaic and/or capacitive coupling, generated at the OSC/electrolyte interface. Upon light stimulation of the photoactive OSC layer, a local rearrangement of the charges is promoted in the ionic double Helmholtz layer present at the liquid/solid interface. This determines a sustained current and/or a variation of the capacitance of the electrical double layer compared to dark conditions. The carrier separation induces a change in the potential of the electrolyte solution. The capacitive coupling or reversible Faradaic process occurs at the OSC surface or within the bulk material. The capacitive coupling is characterized by the redistribution of charges causing the generation of local and transient electric field close to the polymer/electrolyte interface whereas the Faradaic coupling involves the electrochemical oxidation or reduction reaction caused by electron transfer between the polymer and the electrolyte292.

-

iii.

Photo-electrochemical coupling: this mechanism considers the possible redox reaction occurring at the interface. Under illumination, the OSC interface can be employed to trigger water reduction leading to the generation of gaseous hydrogen for energy production. The photoelectrochemical reaction promotes a local variation of extracellular and/or intracellular pH and the production of ROS, at a nontoxic concentration, and intracellular calcium (Ca2+) modulation288. Photocatalytic reactions have been observed under high intensity light exposure (AM 1.5 G, 100 mW/cm2)293, as well as during extended light stimulation.

The three processes usually coexist. However, the ideal scenario would be an exogenous optoelectrical stimulation via a capacitive coupling between semiconducting polymers and living cells294,295. The capacitive and Faradaic contribution of the electrical stimulation process depends on the materials, the electrolyte, and the device structure used that can favor the former or the latter mechanism296,297,298. Transient, photo-capacitive stimulation mechanism is considered one of the most biologically safe stimulation mechanism used to electrically stimulate cells and tissues299,300,301 because the electric field produced in this way stimulate the cells without causing any damage. Moreover, considering the interface with cells, targeting voltage-gated ion channels by a pure photo-capacitive stimulation is a preferred therapeutic approach as it avoids Faradaic charge injection302 through which ROS303, and changes in the pH value in the cellular environment304 occur which can cause damage to cells and tissues.

Testing approaches, biocompatibility, and illumination schemes

Significant research in the field aims to apply its methods in vivo. It should be considered that, due to the multiplicity of materials in use and the great variety of cells present in the human body, in vivo studies must be preceded always by in vitro studies that are based, as described above, on the evaluation of biocompatibility of the studied material compared to a material used as control, for example polystyrene, normally used for the fabrication of cell culture Petri dishes. Standardized protocols are crucial for evaluating the biocompatibility and stability of these devices, ensuring consistency and reliability across studies64. Equally important is the development of robust in vivo models that accurately replicate real physiological conditions. When conducting in vivo evaluations on animal models, in fact, a detailed description of the operating protocol is essential for reproducibility, along with the definition of the sample size that depends on the level of variability present in the system, to allow for a robust statistical analysis. In general, in vivo studies are particularly susceptible to pitfalls and biases due to the complexity of biological systems and individual variability, making data interpretation more challenging. Issues like small sample sizes, observer bias, and the difficulty in isolating specific effects further complicate outcomes. To overcome these challenges, the use of standardized protocols can minimize procedural variability, while rigorous statistical analysis ensures that sample sizes are sufficient and complex interactions are accounted for. Implementing appropriate control groups, blinding techniques, and automated data collection reduces bias, and replication of experiments across diverse models enhances the reliability of results. These strategies collectively lead to more accurate, reproducible, and generalizable findings in in vivo research. However, despite the complexity and economic cost of organizing in vivo experiments, they certainly add important information on: 1) long-term efficiency of the material which in vitro tests cannot completely reproduce due to the lack of a tissue microenvironment, and 2) possible inflammatory and/or immune reactions linked to the presence of a defense system that is impossible to reproduce in vitro since it is formed by various migratory cells present in the body (leukocytes, macrophages, mast cells, and lymphocytes). Therefore, due to the complexity of these issues, biocompatibility of materials and safety of implantable devices have to rely on detailed guidelines and regulations which are also continuously updated305,306. Moreover, for the specific application of photovoltaic bioelectronics one must also consider light as an important variable of the system. In fact, to study the stability under light, protocols should refer to the existing consensus statements for stability assessment of new generation photovoltaics also known as ISOS protocols307,308,309. These publications suggest a number of tests such as ISOS-D dark storage tests (the main ones being at normal environmental conditions and the damp heat test at high relative humidity of 85% and temperatures of 65 or 85 °C), ISOS-L light soaking tests (the main one at 1000 W/m2 under simulated AM1.5 G spectral irradiance), and ISOS-T thermal cycling tests (the main one from −40 to + 85 °C). The time required to drop to 80% of the initial efficiency of the PV cell, commonly denoted T80, is the main parameter reported serving as a figure of merit for solar cell stability. T80 of cells incorporating biological materials should be compared with controls without these, in order to understand their role in affecting positively or negatively device stability and the mechanisms underlying degradation.

According to ocular safety standards for ophthalmic applications the maximum permissible radiant power that could enter the pupil chronically or in a single short exposure (between 50 μs and 70 ms) at 532 nm is 146.17 mW310. The irradiance levels57 that have been generally used for in vitro retinal stimulation experiments span from around 1 mW/cm2 (~103 lx) to ~100 mW/cm2 (~105 lx)311,312,313 representing the optical power density range typically experienced in human photopic vision during daylight outdoors (1-100 ×103lx)16. Note that the light in homes and offices which is lower, is generally between 100–500 lx (10-1–100mW/cm2) as reported in a recent review on indoor photovoltaics314, and that the 100 mW/cm2 value is equivalent of looking straight at the sun which is known to damage the eye even after few seconds16,315,316. Compared to the PV cell, the artificial retina technology lacks a standardized protocol to carry out aging tests, to verify the long-term stability of the device in biological environments.

Photobiomodulation of the behavior of living systems with organic semiconductors

A recent new strategy for light-mediated exogenous control/stimulation of biological systems focuses on the use of OSCs. These have been used in the last decade for photo-stimulation of excitable and non-excitable cells, in the form of thin films, microstructured platforms, and NPs299,317,318. Their presence has induced neural differentiation, directed growth319, and enhanced tubulogenesis of endothelial colony-forming cells (ECFCs)320, and the correlated stimulation of pro-angiogenic Ca2+ signals in ECFCs through activation of Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) channels useful for vascular regeneration and tissue repair in case of cardiovascular diseases321. Moreover, OSCs were also successfully employed for optoelectrical control of neurogenesis and neuromodulation322, and for sight restoration purposes since they have been shown to stimulate photoreceptors and retinal tissue both in vitro311 and in vivo59. OSCs can be used as pristine materials323 or as multilayer64 or mixed with others in a bulk heterojunction324 to further tune their capability for interaction with biological media as well as their optoelectronic properties. OSCs were also exploited as photosensitive and light-harvesting material to augment photosynthesis of chloroplasts325 and to regulate signaling (carbon dioxide uptake, oxygen release, etc.) in plants326. Here we will highlight the use of OSCs for light-modulation of biological systems, describing the biophysical interaction between OSCs-light-biosystems.

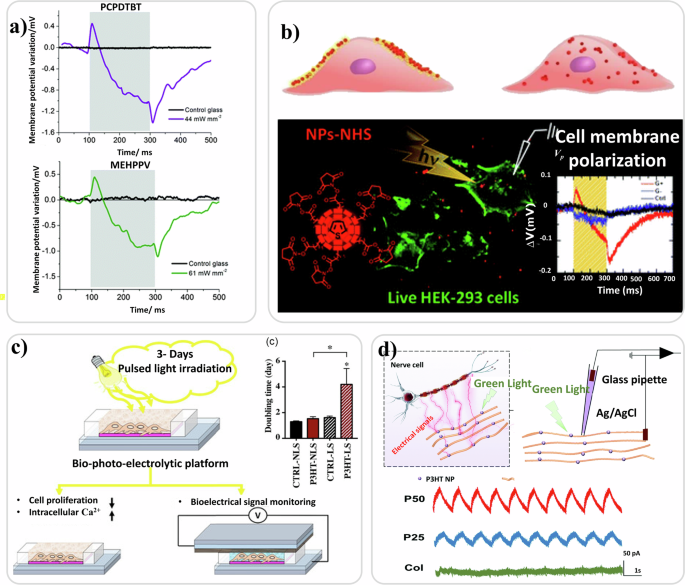

In 2014, Benfenati et al. grew primary neocortical astrocytes of rats on the top of a light-sensitive, organic P3HT:PCBM polymer films11. Patch clamp analysis showed that shining visible light on the system caused a significant depolarization of astroglial resting membrane potential. The effect was associated to an increase in whole-cell conductance at negative potentials. The ion channel likely to mediate the photo-transduction mechanism was identified as the ClC-2 chloride channel. Recently, Borrachero-Conejo et al. showed that pulsed infrared light can modulate astrocyte function through changes in intracellular Ca2+ and water dynamics, providing unique mechanistic insight into the effect of pulsed infrared laser light on astroglial cells, even without the presence of light mediating polymer films327. Thin films based on different OSCs (poly[2,1,3-benzothiadiazole-4,7-diyl[4,4-bis(2-ethylhexyl)-4H-cyclopenta[2,1-b:3,4-b’]dithiophene-2,6-diyl]] – PCPDTBT, rr-P3HT, poly[2-methoxy-5-(2-ethylhexyloxy)-1,4-phenylene-vinylene] – MEH-PPV, poly[9,9-dioctylfluorenyl-2,7-diyl] – PFO) characterized by different absorption spectra, morphology, light emission efficiency and charge transport properties have been investigated as photoactive bio-interfaces323. All the considered polymers, interfaced with human embryonic kidney cells (HEK-293), showed good biocompatibility and cell seeding properties, while electrochemical stability and cell photo-stimulation efficacy differ among them. In particular, the high band gap polymer (PFO), in the work from Vaquero and co-authors323, appeared not appropriate in establishing functional coupling with living cells due to phototoxicity with illumination of blue light. Electrophysiological measurements via patch-clamp under light stimuli (tens of mW/mm2, 200 ms, different wavelengths [see Table 5]) demonstrated that polymer-mediated (PCPDTBT, rr-P3HT, MEH-PPV, PFO) photoexcitation of in vitro HEK-293 cell cultures was possible. In fact, the well-known membrane potential variation with an initial depolarization when light was shone followed by a hyperpolarization effect when light was tuned off was observed323. Bioelectrical polymer light-mediated cell activity was recently linked to the effects on intracellular Ca2+ signaling triggered by OSCs (namely P3HT) upon excitation with light in human adipose-derived stem/stromal cells (hASC)317 which is shown in Fig. 6a. Aziz and co-authors showed that when cells were chronically exposed to light irradiation during the culture time, their responsivity, involving Ca2+ ion trafficking, increased, in comparison with cells kept in dark. This increase was attributed to the light-mediated polymer trigger effect on the Ca2+ ion influx from the extracellular medium, possibly due to the Ca2+ channels expressed on the plasma membrane. Ciocca and co-authors13 developed a compact bio-photo-electrolytic platform (Fig. 6c) based on P3HT thin films in contact with the electrolyte solution/medium. They demonstrated that when neuroblastoma cells were cultured on the OSC thin film and subjected to periodic light stimulation (1.26 mW/cm2, 30 min twice a day 10 h apart, LED with warm white spectra), an increase in intracellular Ca2+ level occurred. The intracellular Ca2+ increase was most likely the result of cell membrane Ca2+ channels being activated by the light stimulus transduced by the photoabsorbing P3HT layer. Moreover, on neuroblastoma cells cultured on P3HT under light-irradiation, proliferative activity was reduced by about 50% with respect to cells cultured in dark condition (either on standard glass or OSC thin films). These results demonstrating that the proliferation rates of cells interfaced with photoabsorbing polymers can be affected greatly by light stimuli, open up novel possibilities for more effective Photo-Dynamic Therapy (PDT) for cancer treatment and for in vitro cellular photo-manipulation in the fields of regenerative medicine and tissue engineering.

a Light modulation of membrane potential in HEK-293 cells cultured on PCPDTBT and MEHPPV polymers photo excited with light sources of 635 nm and 475 nm respectively. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence323. b Pictorial representation of NPs with pendant N-succinimidyl-ester groups docking on the surface of the cells and P3HT-NPs internalized by the cells. Engineered thiophene based NPs for phototransduction in live HEK-293 cells. Reproduced with permission from ref. 329. c Representation of polymer bio-photoelectric platform for electrical signal measurement and light modulation of cell proliferation and ion fluxes. The graph shows the cell proliferation evaluated during the 3 days of culture and expressed as cell doubling time. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.013. d Schematic representation of photoelectric effect-integrated PCL scaffold. Photocurrent curve measurement of the PCL -P3HT-Col scaffold and photocurrent curves of different scaffolds measured during green pulsed LS. Reproduced with permission from ref. 330.

In the form of 3D micro/nano scale bio-hybrid interfaces fabricated by self-assembling of nanofibers, electrospinning or lithographically patterned stripes, OSCs have been used for light-mediated electrical stimulation of neuron-like cells leading to neuronal differentiation and directed neurite outgrowth. Wu and co-authors328 demonstrated that neuron-like cells seeded on OSC thin films (namely P3HT) presenting specific structures and dimensions and cultured under green LED light irradiation (power 2 W) presented longer neuritis compared to those grown on a blank substrate. This cell behavior was mainly attributed to the photoconductive effect of P3HT, that is an increase of charge production by the semiconductor under light illumination that influence cell growth depending on the topographical features of the substrate itself. Moreover, it was directly proportional to the intracellular Ca2+ levels that was verified by monitoring the changes of Fluo-4 AM, a fluorescent Ca2+ indicator. The intracellular Ca2+ level increased for cells plated on P3HT thin film when illuminated by a green LED for 30 min328.

Polythiophene NPs, synthesized as poly(3-octylthiophenes) functionalized with the amine-reactive N-hydroxysuccinimidyl ester group (NHS), were used as photoactive materials inducing phototransduction and polarization of cell membrane under light irradiation. In this work, authors also showed that NPs-NHS attached to the cell membrane, while P3HT-NPs were internalized by the cell329 as shown in Fig. 6b. It has been challenging to provide electrical signals to nerve cells non-invasive/wireless mode, accompanied by the construction of a biomimetic cell microenvironment for supporting nerve cell survival and functional expression. P3HT-NPs were used as photoelectric material to fabricate a self-powered bioactive oriented scaffold for the wireless-light control of nerve cellular behavior in 2022330 as shown in Fig. 6d. A pioneering work recently introduced a 3D bio-printed light-sensitive cell scaffold for bio-photonic applications, based on P3HT-NPs|hydrogel novel bio-ink. The light-sensitive cell scaffold can be used for light control and modulation of cellular activities with several applications in neural engineering and regenerative medicine331. These studies have shown not just that bio-interfaces based on OSCs do not negatively affect biological functions, but that their physico-chemical and structural features can be exploited to sustain and potentially enhance bioactivities.

Biosensing using new generation semiconductors and light

Biosensing, defined by the precise detection of specific bio-compounds or bioelectrical activity, plays a critical role in understanding complex biological processes within living systems. It has found wide-ranging applications in fields such as biomedicine, pharmaceutical drug discovery, food safety, defense, security, environmental monitoring, and basic science332. A biosensor, the core of this technology, integrates a biological element with a physicochemical detector to produce measurable signals in response to target molecules333. These detectors are typically made from a variety of materials, both inorganic and organic, and can be conductive, insulating, or semiconducting334. The primary function of this union is to quantify signals generated by specific biological interactions335.

Key considerations in biosensing are detection specificity and sensitivity336,337. The detection limit in biosensing varies significantly based on the measurement principle, which is broadly categorized into optical and electrical methods. Optical methods, which include fluorescence detection and chemiluminescence with labels, offer relatively high detection sensitivity338. In contrast, electrical methods rely on the amount of electrical current generated from electron transfer between electrodes and molecules in electrochemical measurements, typically exhibiting lower sensitivity compared to optical methods339.

Biosensors, categorized based on their physicochemical transduction mechanisms into distinct groups such as electrochemical340,341, thermal342, piezoelectric343 and optical344 devices, offer diverse capabilities for precise detection in various applications. In optical biosensors, modulation of the optical transduction—through changes in absorbance345, fluorescence346, or refractive index347—regulates the optoelectronic response of the device348. This modulated light signal generates electric output, which is then utilized for biosensing tasks349. For the subject of this review, light-mediated biosensing is especially interesting, and refers to the utilization of light to detect biological processes, leveraging the electric response of the device through photoelectrochemical reactions.

Among the possibilities for biosensing are devices based on semiconducting materials, such as silicon350 or gallium arsenide351, which serve as transducer to detect the biological analytes. There are several types of semiconductor-based biosensors, including field-effect transistor biosensors, electrochemical biosensors, and optical biosensors. Recently, new generation semiconductors such as OSCs that can be deposited in thin film form, and as NPs19,20,21 are being researched to be used for biosensing applications352,353. OSCs, especially solution processed conjugated polymers, have attracted great interest in bioelectronics, due to their outstanding electrical and optical features and their significant bio-interfacing capabilities. Bioelectronics based on OSCs is a rapidly growing field354,355,356,357,358,359,360 that bridges the gap between biology and electronics361. The number of papers published annually on the topic, identified by the keyword ‘organic bioelectronics,’ has increased from one paper in 2002 to 153 in 2023359.

Although detection techniques rooted in photo-electrochemistry have been documented since the 1980s, the concept of “photo-electrochemical (PEC) biosensing” is relatively recent. PEC biosensing is fundamental across various fields, including healthcare, environmental monitoring, food safety, biomedical research, security, and defense. Its paramount significance is within biomedical applications, particularly in healthcare for medical diagnosis. PEC biosensing is crucial for disease monitoring, drug discovery, identifying pathogenic microorganisms, and detecting markers indicative of various health conditions in bodily fluids335,362. PEC biosensing harnesses light to prompt electron transfer between photo-electrochemically active species and electrodes. It operates by tracking changes in the resulting photocurrent363,364 or photovoltage signals induced by biological interactions between recognition elements (such as enzymes, nucleic acids, antibodies) and their targets. This process converts bioanalytical data (like target analyte concentration) into changes in photocurrent or photovoltage339,365.

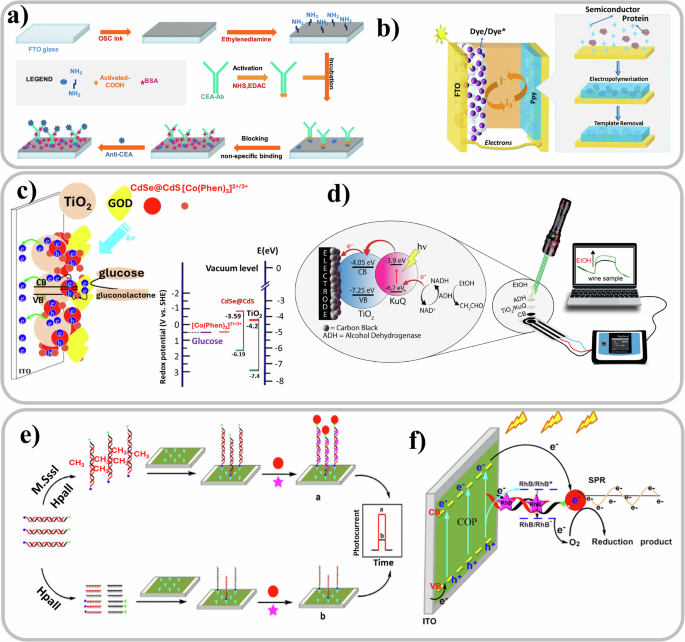

The major components of PEC biosensors include the transducer, target analytes, receptors or biorecognition elements, the electrolyte or electrolyte solution, the light source, and the electrodes. The choice and quality of the transducer are crucial. The transducer’s function is to transform the biorecognition event into a quantifiable signal, usually an electrical signal, reflecting the presence of the chemical or biological target. Transducers in PEC biosensors encompass a range of materials, classified as follows: a) inorganic semiconductors, including titanium dioxide (TiO2), cadmium sulfide (CdS), zinc oxide (ZnO), cadmium telluride (CdTe), and bismuth sulfide (Bi2S3); b) OSCs, such as phthalocyanine complexes, graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4), porphyrin and its derivatives, and polymers such as phenylenevinylene (PPV), poly(thiophene), and various conducting polymers; c) hybrid semiconductors, which combine inorganic semiconductors with differing band gaps or merge organic and inorganic semiconductors, as well as integrate diverse metal or carbon nanomaterials with inorganic/organic semiconductors366. This section will concentrate only on the application of new generation semiconductors for light-based biosensing, first OSCs, then perovskites, and DSSCs providing some significant examples.

Biosensing with organic semiconductors and light

OSCs are among the most promising materials for light-modulated biosensing applications due to their high biocompatibility, tunable absorption, biofunctionalization capabilities, and adjustable electronic properties367,368,369. When integrated into biosensing platforms, OSCs interact effectively with biological analytes, converting these interactions into measurable electrical or optical signals. These signals can be modulated by light to enhance detection capabilities. In light-modulated biosensing, OSCs are commonly used as active layers in devices such as photodetectors and field-effect transistors. By introducing biological recognition elements like enzymes, antibodies, or DNA probes onto the surface of the OSC, specific interactions with target analytes can be achieved. When exposed to specific wavelengths of light, these interactions induce changes in the electronic or optical properties of the OSC, resulting in a detectable signal370,371.

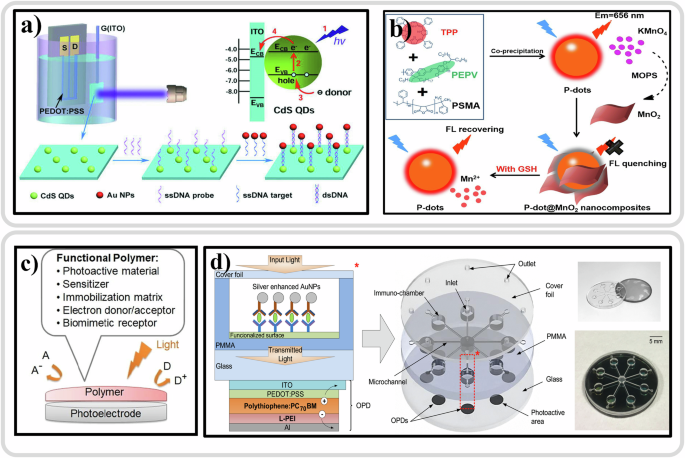

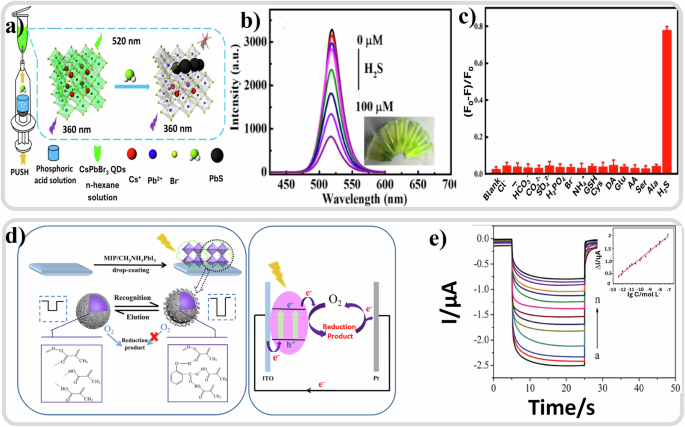

Recently, PEC biosensors with OSCs have garnered significant interest, particularly in enzymatic analysis372, immunoassay14, and DNA sensing373. Among these, PEC DNA biosensors are notable for their ability to provide sensitive, selective, and rapid detection of DNA sequences. A DNA biosensor typically includes a probe DNA as the biorecognition element and an electrode as the signal transducer, with the biorecognition event based on complementary DNA base pairing374. Feng Yan and coworkers in 2018 introduced a new type of organic transistor, known as organic photo-electrochemical transistor (OPECT), to create a groundbreaking DNA sensor with exceptional performance. OPECT is a combination of organic electrochemical transistor and a photo-electrochemical (PEC) gate375. Figure 7a displays the schematic representation of the device configuration of an OPECT. Here, poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrene sulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) served as the active layer of the device, while ITO glass, modified with CdS quantum dots (QDs), acted as the gate electrode, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) along with 0.1 m ascorbic acid (AA) served as the electrolyte. Upon exposure to 420 nm light (intensity: 0.2 mW cm−2), CdS QDs absorbed photons exceeding their bandgap energy, prompting the generation of electron-hole pairs as electrons transition from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB). The presence of AA, a potent electron donor, effectively suppressed electron-hole recombination, ensuring stable electron transfer to the ITO gate. The detection capability of this DNA sensor reached an impressive limit of 1 × 10−15 M, surpassing traditional PEC bioanalysis by several orders of magnitude. OPECT, as an innovative biosensor, holds promise for a wide array of biosensing applications including enzymatic sensors, immunosensors, and cell-based biosensors375.

a Schematics of an OPECT-based biosensor, the charge transfer between CdS QDs and ITO gate electrode and their fabrication method. Reproduced with permission from ref. 375. b Schematic representation of the fabrication of the Pdot@MnO2 nanocomposite-based sensing platform for GSH detection. Reproduced with permission from ref. 388. c Illustration of functional polymers in photoelectrochemical biosensing. Reproduced with permission from ref. 366. d Layout of the optical microfluidic biosensor with L-PEI modified polythiophene-C70 OPDs, includes a schematic overview of the biosensor including layout details for the OPD, tridimensional scheme, and photographs of device layers. Reproduced with permission from ref. 378.