Physical principles and mechanisms of cell migration

Actin polymerization- and adhesion-based migration mechanism

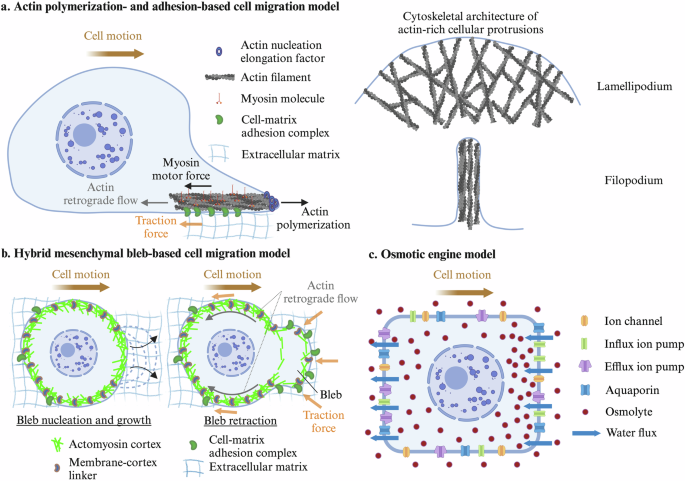

The standard mode of cell migration, extensively covered in numerous review articles1,2,3,4,5, relies on the formation of plasma membrane protrusions, driven by actin polymerization and the formation of complex adhesion structures6. Formins, the Arp2/3 complex and other actin regulatory components, activated by a myriad of signaling molecules7, coordinate the nucleation, elongation and bundling of actin filaments at the cell edge, giving rise to the formation of lamellipodial protrusions, characterized by a dense network of branched actin filaments8, and filopodial protrusions, which are slender, finger-like membrane extensions composed of long, bundled actin filaments9 (Fig. 1a). Adhesion complexes consist of up to hundreds of proteins10, that mechanochemically interact with one another11,12,13, functioning collectively as molecular clutches, which couple the actin cytoskeleton to the extracellular substrate through membrane-bound receptors. Actin filaments experience rearward forces generated by the leading-edge membrane due to actin polymerization14 and by myosin motors binding and pulling filaments away from the leading edge15. These combined forces result in the movement of actin filaments away from the leading edge, a process known as retrograde flow. These flows are restricted to the lamellipodium and typically decay in the lamella, a structurally and kinetically distinct actin network located just behind the lamellipodium that provides structural support to the cell and that is characterized by a more stable and organized actin cytoskeleton16,17. The mechanical coordination of actin polymerization and myosin forces, and adhesion formation enables cells to produce traction forces and migrate (Fig. 1a). These dynamics are described by the motor-clutch model, initially postulated by Mitchison and Kirschner6 and later mathematically formalized by Chan and Odde18, which is consistent with the pulling forces exerted by cancer cells at their leading edge as they migrate within brain tissue19.

a Actin polymerization and adhesion-based migration: Cells migrate through actin polymerization at the leading edge, coupled with myosin motor-driven contractility, which generates front-to-back pulling forces. These forces are transmitted to the extracellular matrix through adhesion complexes. b Hybrid mesenchymal bleb-based migration model: Rapid bleb expansion occurs at the leading edge, coupled with cell-matrix adhesion/friction interactions, integrating features of both bleb-based and mesenchymal motility. (c) Osmotic engine model: Cell migration is driven by osmotic pressure gradients, where local water flux and ion transport generate the forces for cellular movement. Created in Biorender. Alonso Matilla, R. (2024) BioRender.com/k70q271

Cell matrix adhesion begins with the formation of nascent adhesions, mediated by clutch-ligand binding, facilitated by actin polymerization, assembled independently of substrate rigidity or cell contractility, and responsible for the generation of weak traction forces20,21,22. While force generation is not necessary for the initial formation of these nascent adhesions, it is essential for their maturation, along with actin crosslinking23,24, often leading to the formation of focal adhesions. Cells can sense and respond to the mechanical features of their environment25. In this adhesion-based mode of migration, cells exhibit a biphasic dependence of traction force and cell migration on substrate adhesivity/stiffness and motor-to-clutch ratio26,27. Some cells deviate from the biphasic force-rigidity relationship at physiological substrate stiffnesses through force-mediated clutch reinforcement4,28. Force transmission can be limited by frictional slippage between the various constitutive adhesion proteins within clutch complexes29,30 and can be significantly affected by clutch stiffness31 and viscous stresses32, with increased cell migration speeds observed on fast stress relaxing soft substrates33. Different integrin heterodimers can associate with actin structures and compensate for the loss of others to maintain force transmission34. Cells also convert mechanical stimuli into biochemical signals, a process known as mechanotransduction2,35. Clutches consist of mechanosensitive proteins that can be stretched and transition into different functional states, triggering different biochemical signals dependent on the duration, frequency, and history of each mechanotransmission event1. Force transduction in response to external mechanical cues has been shown to be affected by environmental stiffness28,36,37 and viscosity38,39. In addition to mechanical forces, biochemical signaling can also regulate the spatiotemporal dynamics of cell adhesion and the actin cytoskeleton40,41.

A local increase in actin polymerization alone seems to be insufficient to initiate protrusion formation; instead, decreased membrane-cortex attachments are necessary to initiate actin-driven protrusions, like the initiation of pressure-driven protrusions42. Actin filaments serve as cellular mechanosensory elements by regulating force-mediated binding interactions through different mechanisms43. In addition, filaments push the plasma membrane forward according to a force-velocity relationship44, with faster polymerization kinetic rates and faster plasma membrane extension rates occurring when they grow against reduced load/membrane tension. During frictional slippage, such as from reduced ligand densities or clutch impairment, actin filaments experience weaker loads due to stronger actin retrograde flows, leading to increased actin polymerization rates45,46. Despite this compensatory response following clutch impairment, T cell migration remained slow due to poor force transmission45, while dendritic cell migration was unaffected46. The structure of lamellipodial actin networks undergoes significant changes under varying loads, with increased network density and wider orientational filament distribution against higher loads47,48, potentially enhancing network stiffness, force transmission and resistance to mechanical failure48,49. Consistently, in response to elevated extracellular viscosity39 or hydraulic resistance50, cancer cells exhibited an Arp2/3-dependent increase in actin network density at the leading edge. Cells migrated faster in elevated viscosities due to a more contractile and stable lamellipodium, despite potentially slower actin polymerization rates39.

Amoeboid bleb-based cell motility

Embryonic cells, cancer cells and immune cells, among others, often do not rely on the formation of polymerization-driven protrusions for their migration in low adhesive three-dimensional environments, under high confinement or in conditions of high cortical contractility. Instead, they frequently form hemispherical hydrostatic pressure-driven plasma membrane protrusions devoid of actin called blebs51, which are initiated by either a local membrane-cortex detachment or a local cortex rupture52,53, in regions with high actomyosin contraction and/or low membrane-cortex protein accumulation42,54,55, consistent with computational results56. The development of intracellular hydrostatic pressure gradients, caused by local actomyosin contraction and osmotic force generation, mediates bleb expansion. Bleb protrusion initiation is followed by a drop in local intracellular hydrostatic pressure, causing cytoplasmic material to flow through the detached actomyosin meshwork from the cell center to the low-pressure region, facilitating bleb expansion56,57. The poroelastic permeable cortex, unable to sustain pressure forces, moves retrogradely towards the cell center58,59. The bleb cycle concludes by recruitment of new actomyosin cortex underneath the bleb membrane, which transmits inward forces to the plasma membrane driving bleb retraction and cytoplasm from the bleb region to the cell center52. Bleb-based cell motility can be divided into two distinct regimes.

In the first bleb-based migration regime, the cell polarizes either a stable bleb60,61,62,63 or multiple blebs/blebs-on-blebs64 at its leading edge, resulting in minimal cell shape and directional changes. This regime is primarily observed in highly contractile cells under high confinement, high friction and weak adhesion, either within low adhesive channels or in poorly adherent cells. Force transmission is mediated by friction-like forces with the channel walls, driven by large-scale actin retrograde flows that typically encompass the whole cell body, powered by front-to-rear contractility gradients, with a high contractile region at the cell’s rear65. Cell-substrate friction forces, balanced by drag forces, mediate the migration of these cells in confinement. The same mechanism has been proposed for the migration of actomyosin biomimetic water-in-oil droplets in microfluidic channels66. Membrane-cortex detachment at the leading edge likely facilitates the development of stronger retrograde flows and the establishment of persistent polarity and rapid, directed cell motion55,67. The existence of long-range flows is regulated by the characteristic length of stress propagation or cortex hydrodynamic length68, facilitated by a highly crosslinked actin network69 or by a low actin-substrate drag coefficient54. This mode of migration has been associated with cells effectively exerting extensile forces on the surrounding gels64,70, in agreement with the stronger cortical flows observed near the cell’s rear64. However, stronger actin flows were observed at the leading edge of other migrating cells60,61, suggesting that these cells exert contractile forces on the substrate. Cell-matrix elastic interactions effectively behave as friction in scenarios where the dissociation rates of cell-matrix adhesion bonds are high71,72. Therefore, this friction-based migration regime can be achieved by cells embedded in extracellular matrix within in vitro or in vivo environments and falls under the broader adhesion-based motor-clutch framework. High actomyosin contractility and β1 integrin accumulation at the cell’s rear, potentially transported by actin retrograde flows, mediate integrin-dependent fast invasion of rounded cancer cells in three-dimensional Matrigel73.

In the second bleb-based migration regime, the cell periodically nucleates, expands and retracts blebs at multiple locations, leading to highly dynamic cell shape changes42,74,75. In the absence of cellular adhesion or friction-like forces with the environment, forward movement of cytoplasmic material shifts the center of mass of the cell forward in the direction of the bleb during its expansion phase and in the opposite direction during its retraction phase. A recent computational study56 examined the potential for adhesion-free bleb-based migration and showed that negligible net cellular displacements are achieved in Newtonian environments at the end of a single bleb cycle, and therefore sustained adhesion-free bleb-based cell motility in Newtonian environments requires simultaneous bleb nucleation events, consistent Purcell’s theorem76, and oscillatory cortical forces, where cells alternate between a high-contractility motility phase and a low-contractility intracellular pressure buildup phase. Given the rapid rate of bleb expansion compared to the slower rate of bleb retraction, the computational model also suggests that bleb-based cell swimming could be more effective in viscoelastic fluids rather than in purely viscous environments56, as observed in single-hinge microswimmers experiments moving through shear-thickening and shear-thinning fluids under reciprocal motion conditions77. Therefore, bleb-based cell swimming is possible, enhanced by viscoelasticity, and characterized by moderate cell speeds. A hybrid bleb- and adhesion-based migration mechanism is predicted to result in optimum cell motility, where blebbing allows cells to push their cell front forward at a very fast rate, much faster than F-actin polymerization rates, followed by formation of focal adhesions at the cell front, which prevents cell rearward motion during bleb retraction and mediates subsequent traction force generation and fast forward cell translocation56 (Fig. 1b). In this hybrid mode of migration, cells are predicted to advance in the same direction during both bleb expansion and retraction phases, achieving theoretical speeds that are comparable to physiological fast amoeboid cell migration speeds56. This mode of migration is supported by recent experimental observations, where blebbing melanoma cancer cells migrated through soft collagen matrices by pushing away collagen at the leading edge during bleb growth, and pulling it in during bleb retraction78. Large blebs and paxillin-containing adhesion complex formation biased towards high collagen density regions78. Similarly, fast β1 integrin dependent bleb-based breast cancer cell migration relied on extracellular matrix reorganization at membrane blebs79 with integrin clustering found at bleb sites. These studies are consistent with the fast hybrid adhesion-based bleb-based migration mechanism, whose effectiveness hinges on the predominant formation of cell-matrix adhesions at the leading edge of the cell56.

Osmotic engine model

Osmotic pressure gradients have been proposed to be the primary driving force behind a cell migration mechanism known as the osmotic engine model80 (Fig. 1c). Osmotic pressure can be described as a macroscopic mechanical force exerted by solute molecules, such as ions, sugars, and aminoacids, against a semipermeable membrane such as the plasma membrane. This force arises from the collision of these molecules with the membrane surface81. Following each collision, the solute particles experience an equal and opposite force directed away from the plasma membrane. This force is then transmitted to the solvent, causing a directed movement of water across the membrane from low to high osmotic pressure. Consequently, when a vesicle is exposed to an external solute gradient, it migrates from regions of high to low solute concentration82,83, while the movement of solvent across the plasma membrane occurs in the reverse direction84. This process, known as osmophoresis, leads to speeds of a few nanometers per second when convective flows are suppressed83, consistent with theory84. These speeds are expected to be even lower under the physiologically relevant osmotic pressure gradients typically found in extracellular environments85.

Biological cells are equipped with membrane transport proteins such as active ion pumps, ion channels, amino acid transporters, and aquaporins86,87,88,89. These proteins regulate local transmembrane solute and water fluxes and, if unevenly distributed, they can generate substantial intracellular osmotic pressure gradients, the primary driving force behind the osmotic engine model80,90, a mechanism of self-osmophoresis. This migration mode has been proposed as the cell migration mechanism used by cancer cells within microchannels80,91. It was proposed to be facilitated by local cell swelling and shrinkage at the cell leading and trailing edge, respectively, caused by transmembrane water fluxes. While the migration speed of sarcoma cells did not depend on actin and myosin80, the mean migration speed of breast cancer cells decreased approximately by half after treatment with a high dose of an actin depolymerization drug80,91, suggesting that these cells may use osmotic pressure gradients synergistically with an actin-dependent migration mechanism for efficient migration, consistent with92. In the study by Stroka et al.80, the sodium-hydrogen exchanger isoform-1 (NHE-1) and the water channel protein aquaporin-5 (AQP-5) were polarized at the front of the cell, promoting local cell swelling. Under isotonic conditions, cells migrated toward a chemoattractant. The application of a hypotonic shock at the cell’s leading edge or a hypertonic shock at the trailing edge repolarized NHE-1 and AQP-5 to the new leading edge and reversed the cells migration direction, an unexpected result from an osmophoresis standpoint, where migration towards the hypotonic medium would be anticipated. The authors propose that actin-dependent repolarization of NHE-1 increases the local cytosolic osmotic pressure, driving the cell toward the hypertonic side of the channel. Subsequently, Zhang et al.91 showed that NHE-1 repolarization is facilitated by the regulator Cdc42. In addition to NHE-1 accumulating at the cell’s front, the authors showed that the SWELL-1 chloride channel and the water channel protein aquaporin-4 (AQP-4) polarized at the rear of the cell promoting local cell shrinkage. SWELL-1 polarization was regulated by RhoA, a Rho GTPase and regulator of actin-based cytoskeletal dynamics, and it was required for efficient migration. Interestingly, the dependence of cancer cell migration on NHE-1 and SWELL-1 was also observed in 3D collagen matrices and spheroids, and their dual knockdown blocked cancer cell metastasis in mice91. Analysis of deformation in the pericellular environment to discriminate between the motor-clutch and osmotic engine mechanisms revealed that glioma cell migration is consistent with the motor-clutch migration mechanism while being inconsistent with the osmotic engine model19.

Nuclear piston mechanism

In mammalian cells, the nucleus not only serves as storage for genetic material and ensures its integrity while facilitating its transcription and replication but also plays a crucial role in cell migration. As the largest and stiffest cellular organelle, the nucleus constitutes an impediment to non-proteolytic cell migration within complex tissue microenvironments93. These crowded environments are often laden with a densely packed extracellular matrix and cellular aggregates, presenting challenges that require cells to squeeze their nucleus through constricted interstitial spaces, using the nucleus as a mechanical gauge to detect and move through the path of least resistance94. Misplacement of the nucleus, or its reduced deformability, due to factors such as elevated nuclear rigidity95,96,97, reduced cortical contractility98,99 or disruptions of the nucleo-cytoskeletal force transmission machinery100, have been associated with impaired three-dimensional (3D) migration.

Beyond the discussed roles on cell migration, the nucleus has been proposed as a central figure in a distinct cell migration mechanism known as the nuclear-piston mechanism101. This mechanism is characterized by the formation of blunt cylindrical pressure-driven protrusions, known as lobopodia, and nonpolarized cell signaling (PIP3, Rac1 and Cdc42)102. According to this model, the nucleus physically divides the cell into front (anterior) and back (posterior) compartments, with actomyosin-generated forces propelling the nucleus forward, causing pressurization of the cytoplasmic front compartment101, with the nucleus acting akin to a piston in this process. Consistent with this scenario, hydrostatic pressure measurements using the servo-null method on primary human fibroblasts migrating in a 3D cell-derived matrix revealed a non-uniform hydrostatic pressure throughout the cytoplasm, with values of ∼2400 Pa in the front and ∼900 Pa in the back101. This pressure gradient across the cell could arise due to mechanical compression of the anterior compartment caused by the piston-like nucleus itself, due to intracellular osmotic pressure gradients, or due to varying actomyosin forces throughout the cell. Irrespective of the origin of this gradient, slow hydrostatic pressure equilibration throughout the cytoplasm can be expected due to the high resistance to water flow offered by the soft and porous cytoplasmic structure103.

On one hand, multiple studies have identified increased cortical contractility at the rear of the cell104,105,106,107, suggesting that elevated hydrostatic pressure in the posterior compartment, contrary to experimental hydrostatic pressure measurements, push the nucleus forward aiding its movement through 3D constrictions. The question remains whether this increased hydrostatic pressure behind the nucleus can actually propel the nucleus forward, similar to the pressure driven transport observed in amoeboid cells during cytoplasmic streaming, or if it simply leads to a local nuclear volume expansion104. Conversely, a different body of research presents compelling evidence that the nuclear forward motion is mediated by actomyosin pulling forces in the anterior side facilitated by nucleoskeleton-cytoskeleton crosslinking proteins98,101, notably involving Myosin IIA, vimentin intermediate filaments, tropomyosin (Tpm 1.6/7) and nesprin-2, which are all concentrated in front of the nucleus98,101,108. In these studies, the nucleus moved forward independently of the cell’s trailing edge, and while inhibiting myosin II activity at the cell rear had no effect, inhibiting it in front of the nucleus prevented nuclear forward movement, decreased hydrostatic pressure at the front and caused the leading edge to retract101, supporting a mechanism where front-directed cytoskeletal forces drive nuclear movement.

This raises a crucial question regarding how these high-pressure protrusions contribute to protrusion expansion and effective lobopodial cell migration in complex 3D environments, given that high hydrostatic pressure at the forefront of the cell would lead to a transient expulsion of small amounts of water from the protrusion, causing its shrinkage, which contradicts with experimental observations. A recent study suggests that the forward motion of the nucleus elevates local hydrostatic pressure at the front, which in turn, triggers mechanosensitive ion channels to open, prompted by the stretching of the plasma membrane. This leads to an influx of ions into the protrusion, causing osmotic pressure to become the dominant force over hydrostatic pressure, thereby driving the expansion of the protrusion and enabling fast lobopodial migration105. The proposed mechanism through which elevated hydrostatic pressure in the protrusion activates mechanosensitive ion channels is not clear, since an initial elevated hydrostatic pressure within the protrusion will induce cell protrusion shrinkage, potentially reducing plasma membrane tension. An alternative mechanism could involve the nucleus moving forward in a piston-like manner, concentrating osmolytes at the front of the cell, thereby triggering an osmotic pressure-driven protrusion expansion. This initial expansion can activate mechanosensitive channels, consistent with the study by Lee et al.105, further increasing the local osmotic pressure, which drives rapid protrusion expansion and fast cell migration. The concept of osmotic pressure as the main driver of protrusion expansion in lobopodial cells, while not widely studied, is biophysically plausible and could be a potential opportunity for further experimental and theoretical work.

Alternative modes of migration

A recent study109 proposes a new cell migration mechanism, claiming that immune cells navigate serrated microfluidic channels without the aid of adhesion or friction-based forces. The ability of cells to migrate in non-adhesive microfluidic channels depended on the topology of the channel walls, where talin-deficient cells migrated efficiently in serrated-wall channels, but they were unable to translocate in smooth-wall channels. The study contends that cell migration is driven by intracellular pressure gradients, created by retrograde flows and actin flow curvature shaped by channel wall topography. The authors claim that in regions of high intracellular hydrostatic pressure, the channel walls experience a greater hydrostatic force, while in regions of low intracellular hydrostatic pressure, the force on the walls is reduced. This is said to generate a net hydrostatic force, propelling the cell opposite to that of actin flows. However, this theory conflicts established principles of plasma membrane physics, as intracellular hydrostatic forces cannot be directly transmitted to the channel walls. A local elevated cytosolic pressure causes minimal transmembrane water effluxes, slightly pulling the plasma membrane inward rather than significantly exerting any outward hydrostatic force on the channel walls as claimed by the authors. A more plausible explanation for their findings could be that the strength of adhesion and friction forces varies according to the topographical features of the channel. Another confinement-induced migration mechanism was proposed to rely on actin polymerization against channel walls and enhanced cell-wall friction forces due to intracellular hydrostatic pressure buildup110. Following the same physical reasoning, an elevated intracellular hydrostatic pressure will tend to pull the plasma membrane away from the channel walls, thereby reducing drag forces with the walls, contrary to the authors’ claims. An alternative adhesion-free swimming mechanism was proposed for macrophages suspended in a fluid, where membrane retrograde flows were linked with cell motility111. The authors concluded that cell migration is driven by slippage between the plasma membrane and the surrounding fluid112 possibly caused by the mechanical coupling of transmembrane proteins, powered by actin retrograde flows, with the surrounding fluid111,113. Other possible adhesion-free cell swimming mechanisms rely on Marangoni stresses114,115 or actomyosin-driven cell shape changes through peristaltic waves116.

Conclusions and future directions

In this review, we have provided an overview of the primary cell migration mechanisms that animal cells use to move through distinct cellular environments. Although each mechanism relies on distinct physical principles, cells may simultaneously employ multiple migration mechanisms or utilize a specific mechanism based on their internal state, environmental physicochemical conditions or in response to a cellular perturbation117,118,119,120,121. Phenotypic switching122, wherein cells alter their migration mechanisms, is particularly essential for cancer cells51 and immune cells117, which frequently encounter a myriad of physical and chemical barriers. This adaptive capability creates an environmentally dependent dynamic interplay between cancer cell dissemination and the antitumor immune response, with outcomes potentially heavily influenced by the surrounding microenvironment. It is important to note that the cell migration mechanism is dictated not by the formation of a given protrusion, but by the mechanism of force generation and transmission with the environment. For example, lamellipodial-like protrusions can act as exploratory sensors facilitating directional changes, aiding in cell migration through dense collagen gels, but are not essential for three-dimensional immune cell migration123,124. Similarly, blebbing is frequently observed at the forefront of lobopodial cells soon after the nucleus enters the protrusion105, though they might not contribute to force generation in this context. Although cell polarization has not been the focus of this review, for cells to undergo directed motion and effectively explore their environment, they must first establish polarity125,126. Various electrochemical and mechanical environmental cues can induce cell polarization and directed motion, including chemical cues127,128, mechanical cues129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137 and electric fields138,139,140. Understanding how these external cues affect cell responses in each mode of migration presents an exciting opportunity for further research. During confined migration, the nuclear envelope, composed of an outer nuclear membrane and an inner nuclear membrane that separates the nucleoplasm within the nucleus from the surrounding cytoplasm, is susceptible to rupture due to nuclear compression driven by its associated contractile actin bundles, a phenomenon observed in vitro and in vivo141,142,143. Such disruptions in nuclear integrity threaten genomic stability and may induce alterations in chromatin organization and gene expression profiles. Although mechanisms for rapid repair of the nuclear envelope are in place141,142, the consequences of these ruptures on the fate and migration potential of cells, such as metastatic cancer cells or rapidly moving immune cells, remain an area for further investigation.

Many additional questions remain unanswered. How do actin polymerization and myosin motor forces combine to drive architectural changes in the cytoskeleton and mechanotransduction events to facilitate adhesion-based migration? What is the molecular origin of cell-substrate frictional forces? Although these forces could be mediated through numerous weak clutches or involve van der Waals forces144, covalent bonds, hydrogen bonds, ionic bonds, and implicate the glycocalyx145, additional research is needed to clarify these interactions. While evidence indicates that the glycocalyx is involved as a sensor and transducer of mechanical and chemical signals during cell invasion146,147, the precise mechanisms underlying this process remain poorly understood. Also, blebbing cells can generate sufficient hydrostatic pressure gradients that enable them to push and pull on fibrous matrices, facilitating their movement through dense, tight spaces without relying on proteolytic matrix degradation78,148. How soft must the extracellular environment be for cells to generate sufficient pressure-driven forces to migrate in these crowded environments? Some studies suggest that cell migration can be achieved in the absence of specific adhesions46,149 or rely on transient, diffuse adhesions/low affinity interactions between the actin cytoskeleton and plasma membrane with the extracellular environment150,151. Do cells use the synergy between blebbing and adhesion formation for fast migration under poor adhesion conditions? What are the spatial and temporal dynamics of adhesion complexes in this hybrid adhesion- and bleb-based mode of migration? To date, there has been a notable absence of in vivo data demonstrating osmotic-driven migration, in stark contrast to the well documented evidence for mesenchymal and amoeboid migration modes. A critical question remains: do cells employ the osmotic engine model to navigate through complex and fibrotic biological tissues, or are intracellular osmotic pressure gradients generated by cells to facilitate their movement, potentially in synergy with other migration mechanisms? Addressing this gap in knowledge could significantly advance the field and confirm the relevance of osmotic-driven migration in physiological settings. In addition, the mechanisms behind the polarization of ion pumps and channels, and aquaporins are still not fully understood, although they appear to be influenced by the dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton91. While interactions, direct or indirect, between ion channels and the actin cytoskeleton do affect ion channel activity152,153,154, the specific role of the cell cortex in osmotically driven cells remains unclear. F-actin cellular content increases as cells shrink and decreases when cells swell155,156. Similarly, the local ionic strength and physical interaction between ion channels and adhesion molecules modulate the strength of cell adhesion, which in turn influences cell migration157,158,159,160,161. Exploring these interactions further represents a promising avenue for future research. Additionally, the mechanisms and specific contributions of each ion pump and channel to osmotic pressure and water fluxes are not well understood. For instance, although the antiporter NHE-1 is associated with cell volume increase, the specific mechanism by which it elevates local intracellular osmotic pressure, by catalyzing a net electroneutral sodium ion for proton exchange, remains unclear. Further research, both theoretical and experimental, is required to elucidate how the transport of ions−either slowly against their electrochemical gradients via ion pumps or rapidly down these gradients through ion channels87 −in conjunction with aquaporins, impacts cellular osmotic dynamics, localized transmembrane water fluxes, membrane potential, intracellular biochemical and biophysical signaling pathways and overall cell migration. Further studies are needed to elucidate the specific mechanisms behind the expansion of lobopodial cell protrusions. Effective cell migration through the nuclear piston mechanism requires integrin-mediated cell-matrix adhesion102,162, prompting further questions about the distinctions between lobopodial migration and other adhesion-dependent migration strategies.

Elucidating physiological cell migration mechanisms and identifying critical genetic, proteomic, metabolomic, and extracellular markers presents complex challenges due to the inherent limitations of both in vitro and in vivo studies. In vitro studies often fail to replicate the full spectrum of intricate cellular interactions and mechanochemical environments found in living organisms, exhibiting altered gene expression patterns and cell behavior. Conversely, the dynamic and complex nature of in vivo environments makes it difficult to measure three-dimensional viscoelastic forces, capture high temporal resolution of cellular dynamics at the molecular level, and isolate specific variables affecting cell behavior, complicating study replication and definitive conclusions. Advanced live imaging and genetic manipulation have provided tools to observe and manipulate cells in their natural context, enhancing our knowledge of cellular dynamics during development, disease progression, and response to therapy. However, translating these observations into a broader understanding of cell migration requires sophisticated analytical techniques and computational models to interpret complex data and simulate in vivo conditions. In the future, it will be crucial to develop and incorporate advanced imaging techniques to observe cells and sub-cellular dynamics in vivo. By integrating advanced imaging with reductionist environments and robust mathematical models, a more nuanced and precise analysis of cellular behavior can be achieved. This synergy between imaging and modeling will open new avenues for research and discovery. A collaborative approach among engineers, physicists, biologists, clinicians, immunologists, and imaging specialists will be essential to grasp the complexities of cell migration and translate findings into clinical research and potential therapies.

A deeper understanding of the mechanisms underlying cell migration holds significant promise for advancing targeted therapies across a broad spectrum of diseases. In the context of cancer, elucidating and suppressing cancer cell migration and invasion through surrounding tissues, along with enhancing the infiltration and migration potential of cytotoxic immune cells in tumors could lead to therapies that inhibit invasion and metastasis, preventing the spread of tumors to distant sites. Similarly, therapies that modulate immune cell migration could improve treatments for autoimmune diseases by regulating the excessive infiltration of immune cells into healthy tissues. In regenerative medicine, insights into stem cell migration could optimize tissue repair strategies by enhancing stem cell numbers in damaged areas. Additionally, therapies targeting chronic inflammatory disorders and wound healing could see significant improvements by controlling the migration of pro-inflammatory cells, thereby minimizing extended inflammation and accelerating tissue recovery.

Responses