Piezo1 promotes the progression of necrotizing enterocolitis by activating the Ca2(+)/CaMKII-dependent pathway

Introduction

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in very preterm infants worldwide and is characterized by the acute onset of intestinal inflammation and necrosis, with limited therapeutic approaches1,2. Notably, NEC develops in the context of preterm birth, wherein the immature gut responds abnormally to formula feeding and intestinal bacterial colonization, leading to aberrant epithelial-mesenchymal-immune interactions that are associated with inflammation in intestinal mucosa1,3. Intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) play a crucial role in maintaining gut homeostasis and barrier function, acting as the first line of defense against luminal pathogens. The disruption of IEC integrity and function is a hallmark of NEC, leading to increased intestinal permeability and subsequent inflammatory cascades3,4,5,6,7. Recent studies have highlighted the significance of mechanotransduction pathways in regulating the integrity of the intestinal epithelium, which experiences various mechanical stimuli, including osmotic pressure, gut peristalsis and villous motility.

In clinical settings, various factors associated with NEC are believed to influence the intestinal mechanical microenvironment, which in turn may influence the regulation of intestinal epithelial function. For example, the osmolarity of different enteral contents can alter the tension on epithelial cell membranes; feeding practices, such as the type of milk and milk-feeding rates, may play roles in modulating the intestinal mechanical forces8,9,10. Piezo type mechanosensitive ion channel component 1 (Piezo1), a mechanosensitive ion channel widely expressed in IECs11,12,13,14, translates mechanical forces into cellular responses. In IECs, Piezo1 senses the mechanical forces of the formation of epithelium membrane ruffles induced by bacterial invasion and subsequently reprograms inflammatory gene expression of IECs with Ca2+ influx as an intermediate pathway15; IEC-specific Piezo1 deficiency significantly reduced the production and secretion of inflammatory mediators in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and alleviated sepsis-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction, whereas Piezo1-specific activation increased the release of proinflammatory cytokines14,16,17. Considering its role in regulating epithelial barrier function, inflammation, and cellular homeostasis, Piezo1 is likely pivotal in the development of NEC; however, how Piezo1 affects NEC progression remains unexplored.

Here we sought to explore the role of Piezo1 in regulating IEC response during the progression of NEC. We demonstrated that the cation-channel Piezo1 was expressed in both neonatal and murine IECs. Furthermore, mice lacking Piezo1 in IECs exhibited resistance to NEC owing to the impaired inflammatory mediators, and pathological Piezo1 activation exacerbates intestinal inflammation through the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII)-dependent signaling pathway. Finally, we evaluated the inhibitory effects of a CaMKII inhibitor, suggesting that Piezo1 may be a potential therapeutic target for this devastating disease.

Results

Piezo1 is dynamically expressed in the developing intestinal mucosa of neonatal mice and neonates and NEC is associated with increasing intestinal epithelial Piezo1 expression

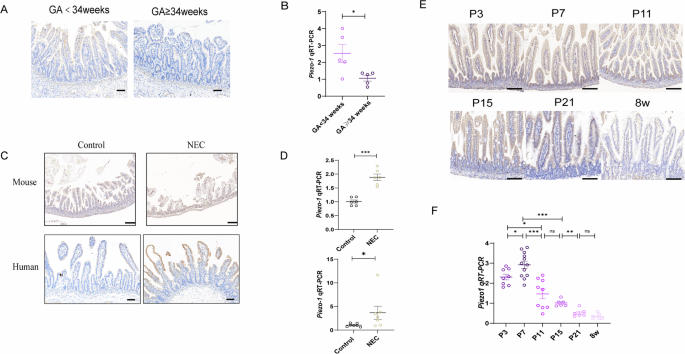

To examine the potential involvement of Piezo1 in the pathogenesis of NEC, we first investigated the expression of Piezo1 in human preterm infants and neonatal mice. As revealed by immunohistochemistry (IHC), Piezo1 was expressed throughout the cellular membrane of epithelium (Fig. 1A). As preterm infants with lower GA are susceptible to NEC, we measured the expression of Piezo1 at different GAs during intestinal development. We found that Piezo1 expression was lower in preterm infants with GA ≥34 weeks than in those with GA <34 weeks (Fig. 1A, B). Also, Piezo1 was significantly increased in both humans and mice with NEC compared with that in controls (Fig. 1C, D). Most studies used mice at postnatal day 3 (P3) -P10 to establish murine NEC models18. We found that Piezo1 expression in neonatal mice before P10 was significantly higher than that in neonatal mice at P21 (the murine intestine reaches the structural/functional maturity of the term human neonate19) and adult mice (Fig. 1E). Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) revealed that the mRNA level of Piezo1 in neonatal mice peaked at P7 (Fig. 1F), which is consistent with that at the start time of the recently proposed unifying model for the pathogenesis of NEC based on the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) receptor TLR4. These results suggested that Piezo1 expression may be relevant to the occurrence of NEC during the premature stage and NEC is associated with increasing intestinal epithelial Piezo1 expression.

A Representative images of IHC analysis of Piezo1 expression in neonates with different GA (Scale bar: 100 μm). B qRT-PCR showing the expression of Piezo1 in neonates with different GA (n = 5 biologically independent samples). C Representative images of Piezo1 immuno-stained sections of human and mouse intestinal specimens from control and NEC patients or animals (Scale bar: 100 μm). D Expression of Piezo1 by qRT-PCR in the small intestine of mouse (n = 6 mice) and human (n = 7 biologically independent samples). E Representative images of IHC analysis of Piezo1 expression in the intestine of mice during the postnatal period at the indicated times. F qRT-PCR showing the expression relative to GAPDH of Piezo1 in the intestine of mice during the postnatal period at the indicated times (n = 8,12,9,6,6,6 mice). P values were determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test and Mann–Whitney U test, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Data are mean ± SEM.

Piezo1 deficiency reduces NEC severity in mice

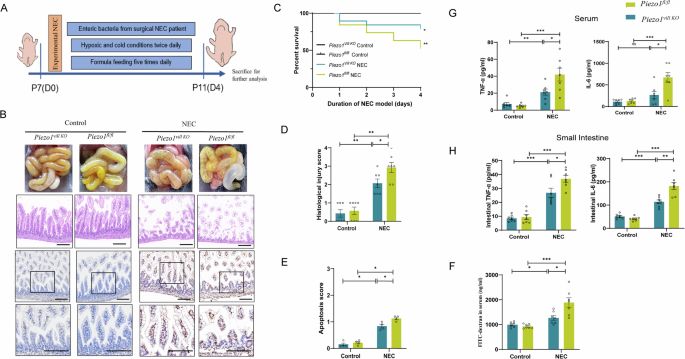

Next, we aimed to evaluate the role of Piezo1 in experimental NEC models (Fig. 2A). Piezo1 deficiency had no effect on the overall structures of the small intestine, as no significant changes were observed in the length of small intestine, villus length, and depth of crypts of villin-specific Piezo1 knockout mice (Piezo1flox/floxVillinCre + , Piezo1vill KO) and Piezo1flox/flox littermates (Piezo1fl/fl) (Supplementary Fig. 1A–D). Intestinal injury was observed based on gross inspection and histological changes of the small intestine in NEC models, as revealed by edema, air-filled loops of bowel, the shedding of epithelial cells, and necrosis of the entire villus (Fig. 2B). The survival rate was significantly higher in Piezo1vill KO mice than in Piezo1fl/fl mice, and the severity score of NEC was significantly lower in Piezo1vill KO mice (Fig. 2C, D). The degree of apoptotic IECs significantly decreased in Piezo1vill KO NEC mice compared with that in Piezo1fl/fl NEC mice, as indicated by the TUNEL assay and the apoptosis score (Fig. 2B, E). Moreover, the degree of impaired intestinal barrier function was also reduced in this group, as revealed by the reduced serum levels of orally administered fluorescein-isothiocyanate-conjugated dextran (FITC-dextran) (Fig. 2F). The levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the serum and ileum of Piezo1fl/fl mice were significantly increased, and such increases were reduced by Piezo1 knockout (Fig. 2G, H). Intestine inflammation affects intestine length, and the small intestine length of NEC-induced Piezo1vill KO mice was significantly longer than that of Piezo1fl/fl mice (Supplementary Fig. 1E, F). These results further confirmed that Piezo1 is critical for the development of NEC.

A Schematic illustrating the experimental NEC induction. B Representative images of gross intestinal morphology, H&E-stained and cell apoptosis measured by TUNEL assay in Piezo1fl/fl and Piezo1vill KO intestines after NEC induction (Scale bar: 100 μm). C Kaplan–Meier estimates and log-rank tests were used to analyze the survival rates of Piezo1fl/fl and Piezo1vill KO mice in the control group and NEC group (n = 6,6,19,19 mice). D Quantification of the histological injury of NEC (n = 7 mice). E Intensity-based apoptosis score of Piezo1fl/fl and Piezo1vill KO mice in the control group and NEC group (n = 4). F Fluorescence readings in plasma 4 h after gavage with FITC-dextran from Piezo1fl/fl and Piezo1vill KO mice in the control group and NEC group (n = 7 mice). G, H TNF-α and IL-6 levels of serum and intestinal tissue lysates were detected by ELISA in Piezo1fl/fl and Piezo1vill KO mice (n = 7 mice). P values were determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test and Mann–Whitney U test, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Data are mean ± SEM.

Piezo1 activation aggravates LPS-induced inflammatory response in Caco-2 cells

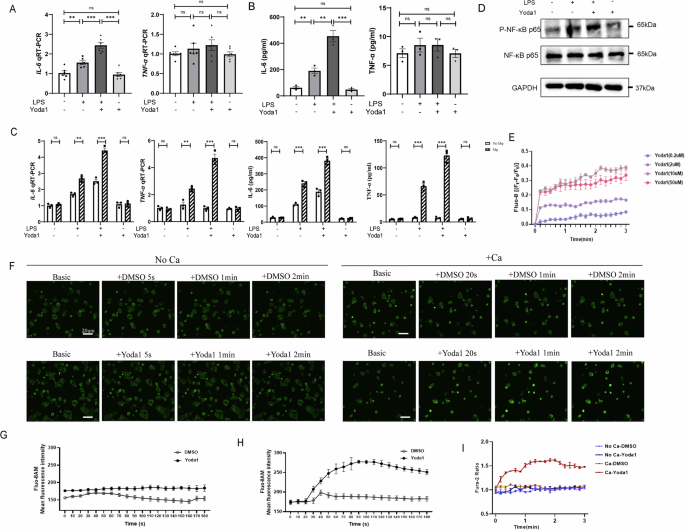

We investigated the role of Piezo1 in regulating the LPS-induced inflammatory response of IECs, and the pro-inflammatory phenotype was examined by measuring the production and secretion of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)-6 in Caco-2 cells using qRT-PCR and Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Notably, the application of 10 μM of Yoda1 (a Piezo1 activator) during LPS priming resulted in increased IL-6 production, without affecting TNF-α production (Fig. 3A, B). This may be because Caco-2 cells alone may not fully represent the complexity of intestinal inflammation, so we performed the co-culture experiments of Caco-2 cells and macrophages, and we observed that Caco2 cells co-cultured with macrophages secreted more inflammatory cytokines, particularly with increased secretion of TNF-α (Fig. 3C). In addition, the addition of Yoda1 alone didn’t mediate the secretion of TNF-α and IL-6. LPS had individual capacities to induce NF-κB and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines20. Therefore, we examined the effects of the application of Yoda1 on NF-κB activation in LPS-primed Caco-2 cells. Yoda1 during LPS priming increased p65 phosphorylation but not p65 protein expression, and Yoda1 alone didn’t increased p65 phosphorylation (Fig. 3D).

A qRT-PCR showing the expression of TNF-α and IL-6 in Caco-2 cells exposure to LPS, Yoda1 or LPS with Yoda1 for 24 h (n = 6). B TNF-α and IL-6 released from Caco-2 cells were measured by Elisa method (n = 3). C qRT-PCR and Elisa showing the expression of TNF-α and IL-6 in Caco-2 cells co-cultured with or without macrophages exposure to LPS, or LPS with Yoda1 for 24 h (n = 3). D Representative Western blots showing protein expression in control Caco-2 cells and cells primed with 100 μg/ml LPS after treatment without or with 10 μM Yoda1 for 24 h. E Effects of Yoda1 at different concentrations (0.2, 2, 10 and 50 μM) on Caco-2 cells (n = 3). F Live microscopy of Ca2+ influx (green) in Caco-2 cells stimulated with Yoda1 in the presence or absence of extracellular calcium. The summary of fluorescence intensity of Ca2+ influx in Caco-2 cells stimulated with Yoda1 in the absence (G) or presence (H) of extracellular calcium. I Summary of mean peak intracellular Ca2+ responses to 10 μM Yoda1 in Caco-2 cells with or without extracellular calcium (n = 3). P values were determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Data are mean ± SEM.

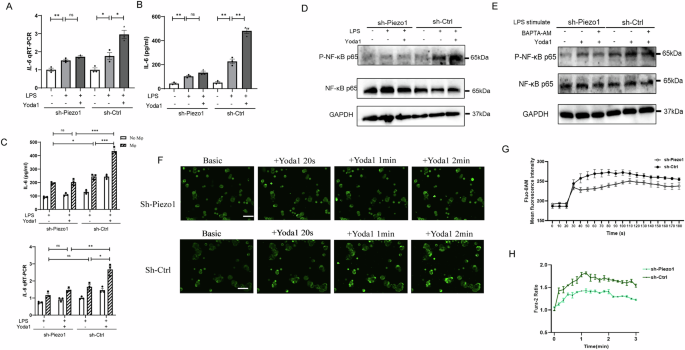

To further validate the role of Piezo1 in mediating LPS-induced inflammatory responses in Caco-2 cells, we compared NF-κB activation and cytokine production in Caco-2 transfected with sh-Ctrl and sh-Piezo1 treated with LPS and Yoda1, respectively. The application of Yoda1 significantly promoted LPS-induced IL-6 production in sh-Ctrl transfected Caco-2 cells, but not in sh-Piezo1 transfected Caco-2 cells, and this effect was consistent whether or not the Caco-2 cells were co-cultured with macrophages (Fig. 4A–C). Consistently, Yoda1 still strongly promoted LPS-induced p65 phosphorylation in untransfected cells, and Yoda1-induced enhancement of NF-κB activation was largely attenuated in Caco-2 cells transfected with sh-Piezo1 or supplemented with BAPTA-AM (Fig. 4D, E). These results indicated that Piezo1 channel activation aggravates LPS-induced NF-κB activation in IECs.

A, B qRT-PCR and Elisa showing the expression and secretion of IL-6 in Caco-2 cells transfected with sh-Ctrl or sh-Piezo1 exposure to LPS, or LPS with Yoda1 for 24 h (n = 3). C qRT-PCR and Elisa showing the expression of IL-6 in Caco-2 cells co-cultured with or without macrophages exposure to LPS, or LPS with Yoda1 for 24 h (n = 3). D Representative Western blots showing the phosphorylated form of NF-κB p65 in Caco-2 cells transfected with sh-Ctrl or sh-Piezo1 exposure to LPS, or LPS with Yoda1 for 24 h. E Representative Western blots showing the phosphorylated form of NF-κB p65 in Caco-2 cells transfected with sh-Ctrl or sh-Piezo1 exposure to LPS, or LPS with Yoda1 or LPS with BAPTA-AM for 24 h. F, G Live microscopy and the summary of fluorescence intensity of Ca2+ influx (green) in Caco-2 cells transfected with sh-Ctrl or sh-Piezo1 in the presence of Yoda1. H Summary of mean peak intracellular Ca2+ responses to 10 μM Yoda1 in Caco-2 cells transfected with sh-Ctrl or sh-Piezo1 (n = 3). P values were determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Data are mean ± SEM.

To determine if Piezo1 activation influences the change of intracellular calcium in Caco-2 cells, we examined the effects of Yoda1, a Piezo1-specific activator. As shown in Fig. 3E–I, Yoda1 increased the intracellular calcium concentration of Caco-2 cells loaded with the calcium indicator Fluo-8 or Fura-2 acetoxymethyl ester (AM) in a dose-dependent manner. The specificity of this effect was further confirmed by the change of intracellular calcium induced by Yoda1 in Caco-2 cells through short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated knockdown of Piezo1 expression (Fig. 4F–H).

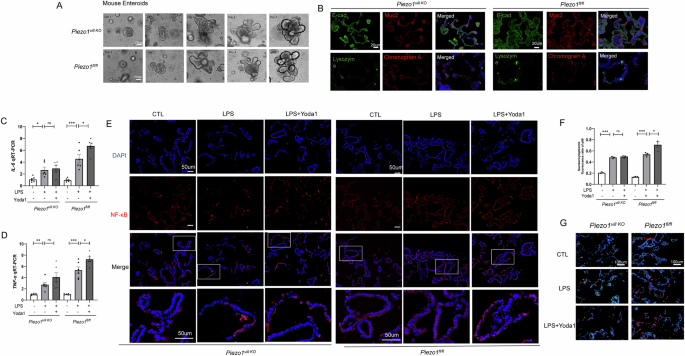

Expression of Piezo1 plays an important role in mediating LPS-induced inflammatory response in primary intestinal organoid cultures (enteroids)

Although Caco-2 cells can be used to elucidate the molecular and signaling mechanisms regulating the function of IECs, they cannot reflect the normal physiology and lineage development of the native intestinal epithelium21. Therefore, to directly investigate whether Piezo1 activation could promote inflammatory response in the intestinal epithelium, we subsequently investigated primary enteroids derived from both Piezo1vill KO and Piezo1fl/fl mice (Fig. 5A, B). Treatment of enteroids with Yoda1 significantly increased the LPS-mediated induction of Tnf-α and IL-6 in Piezo1 fl/fl but not in Piezo1vill KO enteroids (Fig. 5C, D), and the inflammatory response in enteroids was more intense than that of Caco-2 cells in vitro. Yoda1 treatment significantly increased the LPS-induced translocation of the downstream transcription factor NF-κB nuclear translocation in Piezo1fl/fl enteroids, and the Yoda1-induced enhancement of NF-κB activation was largely attenuated in Piezo1vill KO enteroids (Fig. 5E, F). In addition, LPS significantly increased IEC apoptosis in Piezo1fl/fl enteroids, and the degree of intestinal damage increased after Yoda1 stimulation, which was attenuated in Piezo1vill KO enteroids (Fig. 5G).

A Representative images of the growth status in primary enteroids of Piezo1vill KO and Piezo1fl/fl mice. B Representative confocal images of enteroids harvested from Piezo1vill KO and Piezo1fl/fl mice after 7 days of culture on Matrigel, and stained with the epithelial markers and nuclei (DAPI, blue signal). C, D qRT-PCR showing the expression of TNF-α and IL-6 in the enteroids exposure to 100 ug/ml LPS, or LPS with Yoda1 for 6 h (n = 6). E, F Representative confocal images and quantification of fluorescent intensity of NF-κB translocation in the enteroids exposure to LPS or LPS with Yoda1. Magnified images of the boxed areas are presented. G LPS-induced apoptosis in enteroids measured by TUNEL assay in Piezo1vill KO and Piezo1 fl/fl mouse enteroids revealed by confocal microscopy. P values were determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Data are mean ± SEM.

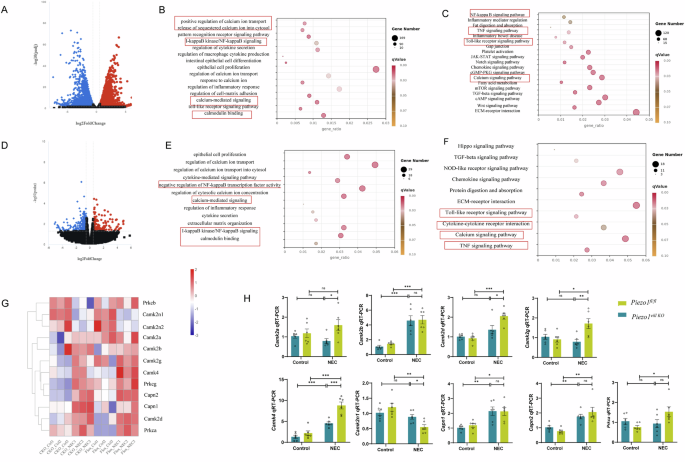

Piezo1 deficiency protects against NEC-induced intestinal injury through inhibiting Ca2(+)/CaMKII-dependent pathway

We demonstrated that calcium influx plays an important role in Yoda1-induced IEC inflammation in vitro. To investigate the possible roles of the decrease of calcium influx induced by the inactivation of Piezo1 in vivo, we performed RNA-sequencing to profile the transcriptomes of Piezo1vill KO and Piezo1fl/fl intestines at 4 days after NEC induction. In Piezo1fl/fl mice, we found a total of 7239 differentially expressed genes after NEC induction (3561 and 3678 upregulated and downregulated genes, respectively; Fig. 6A). Compared with the Piezo1fl/fl -NEC group, 509 differentially expressed genes were observed in Piezo1vill KO-NEC intestines (163 and 346 upregulated and downregulated genes, respectively; Fig. 6D). For subsequent analysis, we only considered at least 1.5-fold differentially expressed genes. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis revealed pathways related to the inflammatory response, impaired intestinal barrier restitution, and haematological impairment are important in NEC pathogenesis (Fig. 6B, C). Genes enriched in Ca2+-mediated signaling pathways and inflammatory response were mostly downregulated during NEC development owing to Piezo1 deletion (Fig. 6E, F), which was consistent with the in-vitro outcomes observed in this study. Combined with the evidence that Piezo1 is directly related to extracellular Ca2+ influx, we focused on the changes in intracellular Ca2 + homeostasis-related genes between the Piezo1fl/fl and Piezo1vill KO groups (Fig. 6G), indicating that Piezo1 mediates NEC in vivo through a Ca2+-dependent manner, one of which activates the downstream calmodulin binding-related signaling pathway. To confirm the expression profiling of downstream proteins directly related to the change of intracellular Ca2+ concentration, we performed qRT-PCR for CaMK, calpain, and protein kinase C. These data indicated that Piezo1 loss-of-function in IECs not only resulted in a significant decrease in mRNA levels of CaMK2a, CaMK2g, CaMK2d, and CaMK4 but also in a significant increase in CaMK2n1 (Fig. 6H).

A Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes (|log2(FoldChange)|>1, P value < 0.05) in the control group and NEC group. B, C GO and KEGG annotation of the differentially expressed genes in the control group and NEC group. D Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes (|log2(FoldChange)|>0.585, P value < 0.05). E, F GO and KEGG annotation of the differentially expressed genes from the Piezo1vill KO and Piezo1 fl/fl intestine after NEC induction. G Heatmap of genes participated in the Ca2+ homeostasis in Piezo1vill KO and Piezo1fl/fl groups after NEC induction. H The expression of Ca2+ homeostasis related genes in Piezo1fl/fl and Piezo1vill KO mice with or without NEC induction was verified by qRT-PCR (n = 6 mice). P values were determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Data are mean ± SEM.

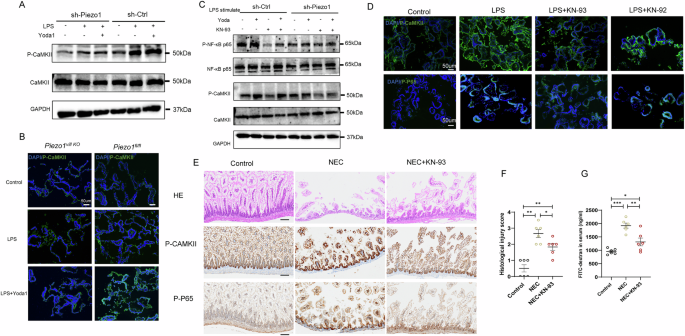

Pharmacological inhibition of CaMKII suppresses NEC severity

To confirm the role of the calmodulin binding-associated signaling pathway in the loss-of-function of NEC caused by Piezo1 deficiency, we conducted western blotting and immunofluorescence staining for CaMKII in Caco-2 cells and enteroids, respectively. We found that CaMKII activation and NF-κB phosphorylation in LPS-induced Caco-2 cells and organoids were reduced in Piezo1-deficient group, and in control group, Yoda1 stimulation significantly increased the activation of these two molecules (Figs. 4C and 7A, B). Consistently, the pre-treatment of KN-93 decreased CaMKII and NF-κB activation in intestinal epithelial inflammation induced by LPS and Yoda1 (Fig. 7C, D). In addition, the KN-92 treatment did not affect the above effects in LPS -induced enteroids (Fig. 7D), confirming the results obtained using KN-93, the inhibition of CaMKII activity could modulate intestinal inflammation.

A Representative Western blots showing the activation of CaMKII in Caco-2 cells transfected with sh-Ctrl or sh-Piezo1 exposure to LPS, or LPS with Yoda1 for 24 h. B Representative confocal images of the expression of p-CaMKII in the enteroids exposure to LPS or LPS with Yoda1. C Representative Western blots showing the activation of CaMKII and NFκB p65 in Caco-2 cells transfected with sh-Ctrl or sh-Piezo1 exposure to LPS, or LPS with Yoda1 or LPS with Yoda1 and KN-93 for 24 h. D Representative confocal images of the expression of p-CaMKII and p-NFκB p65 in the enteroids exposure to LPS or LPS with KN-93 and KN-92. E Representative images of H&E staining and IHC analysis of p-CaMKII and p-NFκB p65 levels in control samples and NEC samples from the KN-93 treatment experiments, Scale bar: 100 μm. F Quantification of the severity of NEC (n = 6 mice). G Fluorescence readings in plasma 4 h after gavage with FITC-dextran from the control samples and NEC samples from the KN-93 treatment experiments (n = 6 mice). P values were determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test and Mann–Whitney U test, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Data are mean ± SEM.

Finally, we evaluated the effect of KN-93 in vivo using the experimental NEC model. The wild-type (WT) mice were intraperitoneally administered injections of either a mock agent or KN-93 at 1 mg/kg once daily for 4 days. Intestinal tissues from mock agent- and KN-93-treated mice were subjected to IHC analysis, and we found that the administration of KN-93 reduced NEC severity, as revealed by the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) score and serum levels of FITC (Fig. 7E–G). In addition, the phosphorylation levels of CaMKII and NF-κB p65 in KN-93-treated NEC mice were significantly decreased compared with those in mock agent-treated NEC mice (Fig. 7E).

Discussion

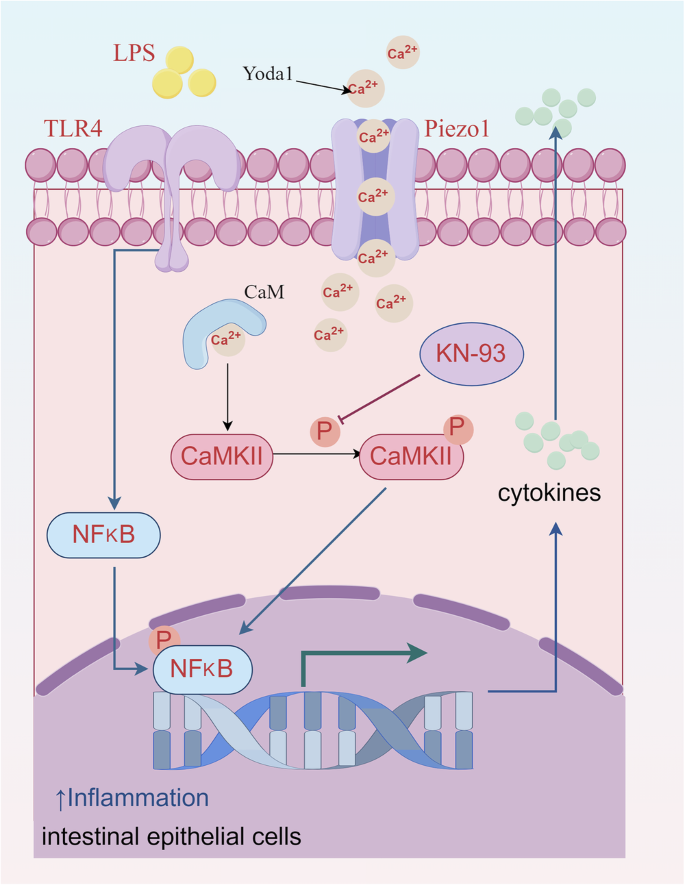

The critical contribution of intestinal epithelial Piezo1 in the development of NEC is substantiated in our study (Fig. 8). First, a positive correlation was observed between increased Piezo1 expression and NEC in both neonatal and mouse samples. Second, the absence of IEC-specific Piezo1 regulates the intestinal barrier function, restricts cytokine secretion, and diminishes the inflammatory response in NEC models. Third, the activation of intestinal epithelial Piezo1 boosts the activity of CaMKII/NF-κB signaling through Ca2+ influx, thereby aggravating intestinal epithelial inflammation, but the pro-inflammatory effect of Piezo1 is suppressed by a CaMKII inhibitor. Our results suggest that Piezo1 inhibition may be a potential therapeutic strategy for NEC patients.

Summary of the regulation and mechanism of intestinal epithelial Piezo1 in intestinal epithelial inflammation during NEC development (This figure was drawn by Figdraw).

Premature infants are susceptible to NEC, which may be due to the abnormal gene expression patterns caused by the forced interruption of normal gut development in the uterus. TLR4, a central bacterial signaling receptor that plays a crucial immunomodulatory role in the development of NEC, is expressed at high levels in the premature gut due to its critical role in intestinal organogenesis and in the regulation of intestinal stem cell differentiation22,23; however, the Gram-negative bacteria that colonize the premature gut in the postnatal period activated excessive inflammatory signaling cascades. Likewise, Piezo1 also plays a pivotal role in the formation and development of organs, for example, Piezo1 contributed to the mechanical regulation of intestinal epithelium and the differentiation of intestinal stem cells in the gut24,25. We speculate that Piezo1 expression in the developing gut may fulfill a role independent of its postnatal role in innate immunity.

Consistent with previous studies15,16,26, we found that Piezo1 was up-expressed in cells of epithelial lineage in the context of intestinal inflammation, and the activation of Piezo1 in IECs results in calcium influx, leading to the activation of inflammatory mediators in the acute phase. IECs are regarded as important regulators in the early stages of NEC, including the regulation of transport between the intestinal lumen and circulation, defense against pathogens, and release of immune signals3,27. IECs can activate cellular functions and gene expression programs not only through pattern-recognition receptor (PRR)-binding microbial molecules, but also by sensing the invasion of microbial molecules through Piezo1 on their membrane surface15,27. This provides a rationale for the involvement of Piezo1 in the pathogenesis of NEC. Piezo1 has been identified as a key regulator of cell extrusion and epithelial stability under steady-state conditions28,29, and our study highlights its pivotal role during inflammation, particularly in NEC. In our study, we observed that conditional knockout of Piezo1 alleviates the severity of NEC, a result partially attributed to changes in intestinal structure and enhanced epithelial stability. However, the underlying mechanisms remain to be fully elucidated. For instance, whether Piezo1 regulates epithelial cell numbers, cell extrusion, or cell division during NEC warrants further investigation.

Notably, Piezo1 is active in many tissues and cell types, where it can contribute to immune responses and inflammation in various ways. In the circulatory system, Piezo1 was activated by disturbed blood flow-regulated inflammatory signaling and pathological angiogenesis to cause vascular endothelial inflammation30. Piezo1 participated in the sustained elevation in intracellular calcium in the acute phase of inflammation, which leads to intracellular organelle dysfunction and induces pancreatic acinar cell necrosis/trypsin activation31,32. Piezo1 can be activated by microenvironment stiffness caused by tissue remodeling at advanced stages of inflammation to regulate the macrophage polarization response, enhance phagocytic and bactericidal activity, and exacerbate autoinflammatory fibrosis33,34,35. In the case of tissue edema in the acute phase or stiff fibrosis in the chronic phase during inflammation, Piezo1 can mobilize extracellular and intracellular Ca2+ stores to disrupt calcium homeostasis and induce inflammation and other cellular events through calcium signaling cascades. NEC, an acute intestinal epithelial injury, has an upregulated calcium signaling pathway compared with the control group, as revealed by RNA-sequencing. Li et al. reported that transient receptor potential melastatin channel-mediated calcium flux activated the NLRP3 inflammasome, and exacerbated the inflammatory response in NEC patients36. Alganabi et al. demonstrated that the activation of CaMKIV participated in Th17 differentiation and IL17 production by modulating the cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element modulators, thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of NEC37. Our RNA-sequencing also indicated that the participation of Ca2+ related signaling genes participated in the downregulation mechanisms in Piezo1vill KO group, suggesting that Piezo1 also acts through the downstream Ca2+ signaling pathway in NEC development. The cue that triggers the opening of Piezo1 in the gut is unknown, but the possible activation may occur downstream of inflammation- or injury-induced changes in mechanical properties, which further exacerbates the inflammatory response in NEC samples. In addition, the gastrointestinal tract is enriched with mechanosensitive ion channels, including TRP channels, K2P channels, and voltage-gated Na+ channels38. Inhibition of transient receptor potential vanilloid type 4 has been demonstrated to suppress the development of colon cancer through activation of the PTEN signaling pathway39. Meanwhile, Piezo2, activated by mechanical forces, promotes the release of serotonin and enhances mucosal secretion40. These findings suggest that the role of gastrointestinal ion channels in NEC may represent a highly promising and intriguing area for future research.

Next, we examined downstream regulators of Piezo1 in the IECs. The data indicated that the NEC-induced elevation of Piezo1 increased the levels of phosphorylated CaMKII; subsequently, CaMKII was response to the increased cytosolic calcium levels. Ma et al. reported that CaMKIIγ in IECs regulated inflammatory signaling and promoted colitis-associated cancer41, and Ye et al. reported that CaMKIIδ could be as a potential response signature to infliximab in ulcerative colitis42; in addition, mounting evidence supported direct interaction between CaMKIIδ and NF-κB signaling in cardiovascular inflammation43,44. However, the mechanism through which the levels of CaMKIIγ and CaMKIIδ, but not other CaMKII isoforms, may act as downstream regulators is currently unknown, pending on the determination in future studies. Currently, most studies focused on the role of the CaMKII family in specific diseases. It is reported that the adhesion of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli adhesion to IECs activated CaMKII, induced oxidative stress, and then affected the NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase (MAPK) pathways and to induce inflammation45, and in IECs, the activation of Piezo1 participated in NF-kB-, MAPK-, Ca2+−, and PI3K/AKT-dependent signaling, which are all known modulators of inflammation response15. Therefore, to verify Piezo1-induced intestinal impairment in mice and the potential mechanism of the activated signaling pathway of Piezo1/CaMKII/NF-κB, we injected the CaMKII inhibitor into the WT mice and found that the mucosa injury of these mice was partly ameliorated, as evidenced in vitro. Overall, these findings suggested that activated Piezo1 should be the trigger of signaling pathways of the cytosolic calcium oscillation and CaMKII phosphorylation, and thereafter promote NF-κB from the cytoplasm into the nucleus, which was responsible for inflammation and cell death.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, we did not detect intracellular calcium levels in enteroids or determine the dose-effect relationship for calcium oscillations of the developing gut in vivo. Nevertheless, our current results, including immunoblotting analysis and injection of KN-93 into the peritoneal cavity of mice, illustrate the impact of activation of Piezo1/CaMKII/NF-κB signaling on the severity of NEC. Future studies can focus on the potential value of calcium channels in NEC, and the development of in vivo calcium imaging technology will help to explore this direction. Secondly, we observed that co-culture with macrophages led to a more pronounced inflammatory response in Caco-2 cells, particularly with increased secretion of TNF-α. This suggests that macrophages, as key immune cells in NEC, might contribute significantly to the inflammatory process through mechanisms involving Piezo1 on their surface. Due to the scope of this work, we did not expand further into macrophage-specific mechanisms but these findings strongly indicate that macrophage Piezo1 may also play a significant role in NEC pathogenesis. Finally, although more and more evidences show that Piezo1 plays an important role in intestinal inflammatory diseases46,47, current studies mainly focus on the effects of Piezo1 agonists or knockdown of Piezo1 in vitro, lacking direct evidence simulating the changes of real mechanical microenvironment in vivo, and further exploration of clinical translation of Piezo1 in specific intestinal mechanical microenvironment is still needed.

Conclusion

In summary, our study indicated that intestinal epithelial Piezo1 is important in the development of NEC through Ca2+/CaMKII/NF-κB signaling. These findings complement the uniqueness of PRRs as the core link of NEC pathogenesis and will help broaden our understanding of the relative role of mechanical sensor Piezo1 in NEC development, which may offer the prospect of a renewed approach to this devastating disease.

Methods

Animal experiments

The mice were housed in a specific-pathogen-free facility within the Experimental Animal Center (12-h light-dark cycle to mimic natural daylight conditions, temperature of 22 ± 2°C), and they were housed in a colony (5 mice per cage) with ad libitum access to food and water. Animal experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of The First Hospital of Jilin University (No.2021-0493). We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use.

C57BL/6J WT mice were acquired from Beijing Vital River Lab Animal Technology Co., Ltd. To obtain tissue specific knockouts of Piezo1 from IECs, Piezo1vill KO on C57BL/6J background generated with CRISPR/Cas9 were purchased from Cyagen (Suzhou, China), and their littermates (Piezo1fl/fl mice) served as the controls. The genotyping primers for Piezo1fl/fl are forward primer 5’-AGCAAGGCCAATGTAGTATCTGG-3’ and reverse primer 5’-CTATTGGTGCCTAGTTGGCAGAC-3’; those for villin-Cre are forward primer 5’-CCATAGGAAGCCAGTTTCCCTTC-3’ and reverse primer 5’-TTCCAGGTATGCTCAGAAAACGC-3’.

Experimental NEC models

Experimental models were constructed using 7-day-old mice of either gender (3–3.5 g body weight), and NEC was induced as described in previous reports48,49. In brief, the mouse pups were fed (five times per day) formula containing Similac Advance infant formula (Abbott Nutrition, Columbus, OH, USA): Esbilac (PetAg, Hampshire, IL, USA) canine milk replacer at a ratio of 2:1 supplemented with enteric bacteria (12.5 µL original stool slurry in 1 mL formula) that were obtained from a preterm infant with surgical NEC (Supplementary Fig. 2). The cecal contents of the infant with surgical NEC were collected during surgery, aseptically weighed, and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer at a concentration of 1 g/mL. The original stool slurry was prepared by thorough vortex mixing and subsequent filtration through a 100 μm sterile cell strainer. Newborn mice were simultaneously exposed to hypoxia (5% O2 and 95% N2 for 10 min twice daily) and cold stress (4 °C for 10 min twice daily) for 4 days. The mice in the same litter were randomly divided into NEC group and control group, and all mice were sacrificed at P11.

To test the effect of the inhibition of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase on the development of NEC, the experimental pups were either intraperitoneally injected with either 1 mg/kg of KN-93 (MCE, Shanghai, China, HY-15465) or an equal volume of vehicle (2% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) + 30% PEG400) once daily until the end of the experiment. Littermates of breast milk-fed newborn mice were used as controls.

Tissue collection and injury evaluation

The terminal ileum 3 cm proximal to the cecum was harvested for further analysis, and the ileal histology by H&E staining was used to determine disease severity. The severity of intestinal injury was graded by two blinded reviewers on a scale of 0–450: 0 indicates no damage; 1 indicates slight separation of the submucosa and/or lamina propria; 2 indicates moderate separation of submucosa and/or lamina propria, and/or edema in the submucosal and muscular layers; 3 indicates severe separation of the submucosa and/or lamina propria, and/or severe edema in the submucosal and muscular layers, along with villous sloughing; and 4 indicates complete loss of villi and necrosis. To measure gut mucosal permeability, we administered FITC-dextran (440 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich, Cat#FD4) to mice by gavage 4 h before their sacrifice and measured the serum levels of the FITC fluorescence signal51.

Human intestinal sample collection

Human neonatal small intestinal samples were obtained during surgery for NEC or less-severe diseases of the intestine (intestinal atresia, Hirschsprung’s disease, meconium ileus, etc.), and the Research Ethics Board of The First Hospital of Jilin University approved the collection and use of samples for the study (No.21K008-001). This study was performed in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and informed consent was obtained from all enrolled participants’ parents. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed.

Fresh intestinal tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for over 48 h, embedded in paraffin, and the paraffin blocks were stored until sectioned for analysis. For RNA isolation and qRT-PCR analysis, fresh intestinal tissues were cut into sub-centimeter pieces and immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Culture of enteroids from mouse ileum

Eenteroids were established from the isolated crypts of neonatal (P7–P11) Piezo1vill KO and Piezo1fl/fl mice as previously described52. The proximal small intestine was chemically and mechanically dissociated to separate crypts from villi, and the crypt fragments were filtered through a 75-μm strainer; Finally, the crypt cultures were maintained in Matrigel (Corning, Cat#356231) (defining passage P0) and cultured in IntestiCultTM Organoid Growth Medium (Stem Cell, Cat#06005). The enteroids were digested and passaged using Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent (Stemcell, Cat#07174) weekly, and after passage 3, the enteroids were used for all the experiments. Intestinal epithelial marker E-cadherin, muc-2 Lysozyme, and chromograin A were used for the verification of isolated enteroids. The enteroids were pre-treated with KN-93(10 μM for 2 h), KN-92(10 μM for 2 h; MCE, Shanghai, China, HY-15517) or Yoda1(10 μM for 2 h, Sigma-Aldrich, Cat#SML1558), and then treated with LPS (100 μg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich, Cat#L2880,Cat#L2630) for 6 h for further analysis.

Cell preparation

Caco-2 cells (ATCC, HTB-37) were maintained under standard cell culture incubators in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat#F0193) and 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat#V900929) in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C with 5% CO2. To obtain non-polarized Caco-2 cells, cells were seeded the day before the experiment; Caco-2 cells (0.5-1 × 105 cells/ml) was cultured in the Transwell system (Corning 3460, 12 inserts, 0.4 μm pore size, Corning NY, USA) for 21 days to obtain polarized IECs, and 1.5 mL of culture medium was added to the lower chamber. In addition, the Transwell system was also employed for the co-culture of macrophages and Caco-2 cells. In brief, Caco-2 cells (1 × 105 cells/ml) were seeded on 12-mm permeable Transwell inserts and allowed to differentiate for 14 days before initiating basolateral co-culture with 5 × 105 macrophages. THP-1 cells (ATCC, TIB-202) were maintained under standard cell culture conditions in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat#F0193) and 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat#V900929) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. For non-polarized (M0) macrophage differentiation, THP-1 cells treated with 50 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; MCE, Cat#HY-18739) for 12 h, followed by washing and seeding into 12-well plate. After 48 h, the medium was replaced with serum-free RPMI-1640, and Transwell inserts containing polarized IECs were transferred into the corresponding wells for co-culture. All experiments were performed within passages 20–40.

For the stable knockdown of Piezo1 in Caco-2 cells, either a scrambled shRNA or an shRNA specific for Piezo1 was delivered to Caco-2 cells by lentiviral infection, followed by puromycin selection. To establish the in-vitro NEC model, Caco-2 cells were treated with 100 μg/mL of LPS under serum-free conditions. Moreover, to modulate Piezo1 activation, Caco-2 cells were treated with 10 μM Yoda1 to activate Piezo1. BAPTA-AM (10 μM, Shanghai, China, HY-100545), a calcium chelator, was used to deplete intracellular calcium. The cells and culture supernatants were collected after 24 h.

Quantification of intracellular calcium changes and calcium imaging

To measure changes intracellular calcium induced by Piezo1 activation, we used the Fura-2 AM (Molecular Probes, AAT Bioquest, Cat#21020) and Fluo-8 Medium Removal Calcium Assay Kit (AAT Bioquest, Cat#36308).

Non-polarized Caco-2 cells were seeded into a 96-well plate (1 × 105 cells per well), and cultured for 12–24 h. All wells were seeded from the same batch of cells at approximately 80% confluency, ensuring they were in the logarithmic growth phase. Cells were passaged using trypsin according to standard protocols and the cell suspension was counted using a hemocytometer with trypan blue exclusion to ensure viability and accurate cell counts. The cells were then loaded with 5 μM Fura-2 AM or Fluo-8 NW in Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution buffer. After loading, the cells were stimulated with Yoda1 or DMSO (control) and the fluorescence intensity was monitored at excitation wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm (Fura-2)/490 nm (Fluo-8) and an emission wavelength of 510 nm (Fura-2)/525 nm (Fluo-8), which was read on a Synergy 2 Microplate Reader. For calcium imaging, cells were seeded into a confocal dish; 5 μM of Fluo-8 NW was added and incubated for 30 min; and the stimulant was added as desired, and the fluorescence was simultaneously measured under a confocal microscope (Nikon A1). Images were captured every 10 s for 3 min.

IHC and immunofluorescence

For IHC, intestinal sections from neonates or mice were immersed in EZ-AR Common buffer (pH 9.0) for antigen retrieval. The sections were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies: Piezo1, phospho-NF-κB p65 (Ser536), and phospho-CaMKII-β/γ/δ (Thr286). The details regarding the use of primary antibodies are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The stain tissues were captured using an Olympus microscope (the gain, saturation, and gamma were set to 1.0×, 1.00, and 1.00, respectively).

For immunofluorescence, PFA-fixed frozen enteroid sections or cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 min and blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 min to 1 h. Subsequently, the slides were incubated with primary antibodies targeting NF-κB p65, phospho-CaMKII-β/γ/δ (Thr286), and phospho-NF-κB p65 (Ser536), respectively, or in combination at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with corresponding secondary antibodies (Abcam, ab150077, ab150080) for 1 h. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Thermo Fisher, Cat#62247) was used for nuclear staining. All images were captured under a confocal microscope (Leica or Nikon A1). Fluorescence was quantified using the ImageJ/Fiji software.

For TUNEL staining of the enteroids and intestinal sections, the TUNEL Apoptosis Detection Kit (Beyotime, Cat#C1090, C1091) was used following the manufacturer’s protocol. The apoptosis scores were semiquantitatively evaluated using the H-score via classification of staining intensity53: no staining (0), weakly positive (1), moderately positive (2), and strongly positive (3), and were calculated by two blinded investigators. The H-score was calculated by multiplying the percentage of stained cells (ranging from 0% to 100%) by the staining intensity (ranging from 0 to 3), resulting in scores from 0 to 3.

Immunoblotting

Intestinal tissues and cells were lysed, and protein concentrations were determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher, Cat#23225). The samples were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. After being blocked in 5% fat-free milk or BSA for 1-2 h, membranes were immunoblotted for different proteins using NF-κBp65, phosphor-NF-κBp65, CaMKII, phospho-CaMKII or GAPDH antibodies, combined with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) or anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (Proteintech, Cat# RGAM001, RGAR001).

ELISA

The levels of TNF-α and IL-6 in the serum, cell culture supernatant and small intestine were measured by ELISA kits (Biolegend, Cat# 430904, 431304,430204, 430504) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Whole blood was collected by cardiac puncture during sacrifice, after which the serum was obtained by centrifugation in serum separators. The harvested intestinal tissues were cut longitudinally and flushed with PBS to remove feces, and sonicated on ice in ELISA standard buffer. Readings of the intestinal samples were normalized to total protein concentrations as detected by the BCA protein assay.

qRT-PCR analysis

RNA was extracted from the cells, enteroids and intestinal tissues with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen,15596018) and reverse transcribed into cDNA with TransScript® One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, AT341-01). qRT-PCR was performed using the SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Roche, 4913914001) on a StepOne Real-Time PCR System to determine gene expression. The mRNA expression levels were determined using the 2−ΔΔCt method and normalized to GAPDH. The primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

RNA- sequencing profiling

RNA-sequencing of intestinal samples was conducted in Novogene on Illumina Hiseq 6000 platform as previously described54. Trizol was used to isolate the RNA of intestinal tissues, and NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, E7770) was used to construct the sequencing libraries. Transcript expression with |log2(FoldChange)| > 0.585 and P value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. KEGG enrichment analysis and GO enrichment analysis were conducted by R software.

Statistics and reproducibility

All data are expressed as the means ± standard errors of the mean (SEMs) of at least three independent repeated experiments. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test the normality of data. Two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests (parametric) and Mann–Whitney U test (nonparametric) were used to perform statistical comparisons between the two groups. All statistical analyses were preformed using GraphPad Prism V8.0 (San Diego, CA, USA) and SPSS 23.0 (Inc, Chicago, IL). A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses