Pilot-scale partial nitrification and anaerobic ammonium oxidation system for nitrogen removal from municipal wastewater

Introduction

In the face of global targets for carbon reduction, wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), which account for 2–5% of total carbon emissions in China, are particularly prominent1,2. Carbon emissions from WWTPs mainly include biogenic carbon emissions (organic matter degradation) and indirect carbon emissions (electrical energy consumption, mainly aeration energy consumption), therefore, both parts can be used as ways to reduce carbon emissions3,4. In addition, the discharge standards for WWTPs are becoming more stringent, especially for the discharge of nitrogen in the effluent5,6. Currently, insufficient carbon source is a common situation in municipal WWTPs, which adversely affects the removal of total nitrogen and leads to the failure of the effluent to meet the standard stably7. Most municipal WWTPs operate with a conventional nitrogen removal process, including nitrification (oxidation of ammonia to nitrite and then to nitrate through aeration using oxygen as an electron acceptor) and denitrification (reduction of nitrate to nitrite and then to nitrogen using organic matter as an electron donor)8,9. Therefore, the development of a nitrogen removal process that economized on energy and carbon sources was urgently demanded.

Partial nitrification + denitrification as a nitrogen removal process is when ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) use oxygen as the electron acceptor to oxidize ammonia to nitrite, and then denitrifying bacteria use organic matter as the electron donor to reduce nitrite to nitrogen10,11. Compared to complete nitrification (ammonia → nitrite → nitrate), the partial nitrification process only required the oxidation of ammonia to nitrite, which according to theoretical calculations could save 25% of aeration energy. Meanwhile, during the denitrification process, the reduction of nitrite to nitrogen could theoretically save 40% of carbon source consumption compared to the reduction of nitrate to nitrogen12,13. In high ammonia-nitrogen wastewater treatment, partial nitrification could be started up and maintained by precisely controlling strategies such as low dissolved oxygen (DO) and ammonium remaining14,15,16,17. However, in low ammonia-nitrogen municipal wastewater treatment, the startup and maintenance of partial nitrification remained a global challenge18,19. Meanwhile, strategies such as precise control of DO and ammonium remaining not only increased the operational difficulty and cost, but the remaining ammonium would be detrimental to the effluent total nitrogen. In addition, nitrite in partial nitrification effluent needed to be further treated to meet stringent effluent standards, which typically required additional carbon sources to be removed by denitrification, but this would result in higher costs and carbon emissions.

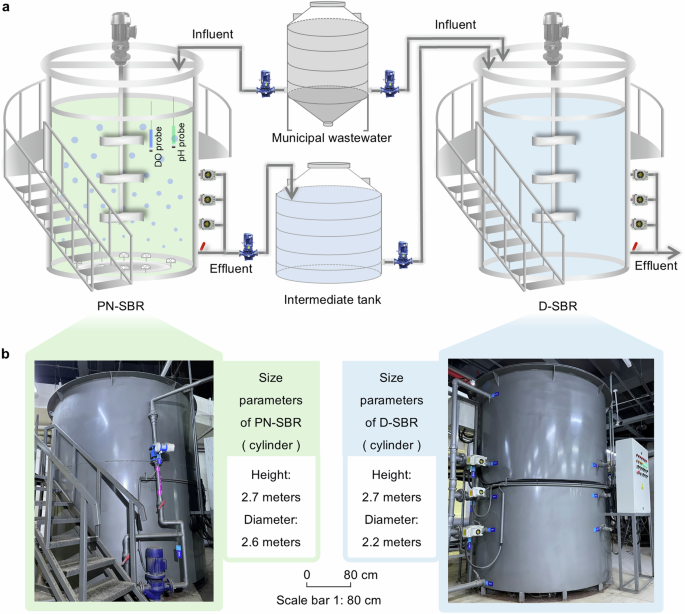

In this study, a pilot-scale double sludge system (partial nitrification + denitrification/anammox) consisting of two sequencing batch reactors for partial nitrification (PN-SBR) and denitrification/anammox (D-SBR) was started up and operated stably (Fig. 1). The strategy of rapid start-up of partial nitrification and stable maintenance were investigated during long-term operation. Dissolved organic matter in municipal wastewater, double sludge system effluent was analyzed by liquid chromatography-organic carbon and organic nitrogen detections (LC-OCD-OND). Long-term operating performances, and typical cycle variations of the double sludge system were analyzed. Finally, microbial community evolution in the partial nitrification system and denitrification/anammox system were investigated by high-throughput sequencing to decipher the high level of nitrogen removal in this double sludge system. Overall, this study provided fresh insights into the stable operation of partial nitrification in municipal wastewater treatment and innovatively proposed a process for low carbon and stably high levels of nitrogen removal.

a The model diagram includes the internal and external structures of the partial nitrification sequencing batch reactor (PN-SBR) and denitrification/anammox sequencing batch reactor (D-SBR). b Field pictures of PN-SBR and D-SBR.

Results

Rapid start-up and stabilization of partial nitrification in PN-SBR

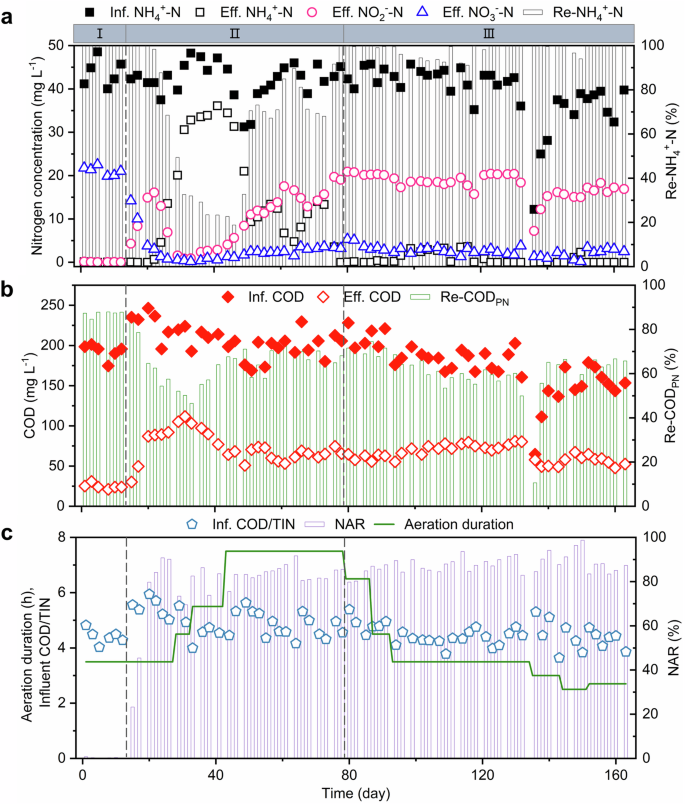

In phase I (days 1–13), a complete nitrification process was carried out in the PN-SBR under aeration duration of 3.5 h (Fig. 2c). Ammonia was almost completely oxidized to nitrate in aerobic stage, the effluent nitrate (NO3−-N) was 21.1 mg L−1, and both ammonium (NH4+-N) and nitrite (NO2−-N) was less than 0.1 mg L−1, and nitrite accumulation rate (NAR) was less than 1.0% (Fig. 2a). Additionally, influent chemical oxygen demand (COD) was 192.7 mg L−1 and COD to total inorganic nitrogen ratio (COD/TIN) was 4.4, and effluent COD was 24.8 mg L−1 and COD removal efficiency was 75.9% in phase I (Fig. 2b). Overall, favorable NH4+-N and COD removal performance was observed in the PN-SBR.

a Influent NH4+-N (Inf. NH4+-N, black solid squares), effluent NH4+-N (Eff. NH4+-N, black hollow squares), effluent NO2−-N (Eff. NO2−-N, pink hollow circles), effluent NO3−-N (Eff. NO3−-N, blue hollow triangles), NH4+-N removal efficiency of PN-SBR (Re-NH4+-N, gray columns). b Influent chemical oxygen demand (Inf. COD, red solid rhombus), effluent chemical oxygen demand (Eff. COD, red hollow rhombus), chemical oxygen demand removal efficiency of PN-SBR (Re-CODPN, olive-green columns). c Influent chemical oxygen demand to total inorganic nitrogen ratio of PN-SBR (Inf. COD/TIN, light blue pentagons), nitrite accumulation rate (NAR, light purple columns), and aeration duration (green lines). I, II, and III at the top of the figure represent phase I, phase II, and phase III in the long-term operation of the system, respectively.

In phase II (days 14–79), complete nitrification was gradually transformed into partial nitrification in the PN-SBR. During days 14–22, the average influent COD increased to 237.6 mg L−1 due to fluctuations in influent characteristics. Also, in this study, during days 1–20, the mixed liquor volatile suspended solid (MLVSS) was reduced from 4.5 g L−1 to 3.5 g L−1 by discharging 150 L of mixed sludge per day at the end of the aerobic stage. The increase in influent COD and reduction in MLVSS resulted in an increase in the organic loading rate from 22.1 (day 1) to 35.2 mg of COD per g of MLVSS per d (day 20). The increased organic loading rate of the PN-SBR allowed the heterotrophic microorganisms to compete with the AOB and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB) for DO. Organic loading shock negatively affected the activity of both AOB and NOB but more on NOB, which also resulted in an accumulation of nitrite in the effluent, with NAR of 84.2% at day 22 (Fig. 2a). In a previous study, partial nitrification was achieved by the strategy of sludge discharge to reduce the sludge concentration and thus increase the organic loading rate of the sludge16.

In phase III (days 80–163), partial nitrification was stably maintained at a condition with no ammonium remaining by the strategy of stopping aeration in time when NH4+-N degradation was complete. The NH4+-N removal efficiency was 98.1% and NAR was 87.7% (Fig. 2a, c). With influent NH4+-N of 39.1 mg L−1, effluent NH4+-N, NO2−-N, NO3−-N were 0.8 mg L−1, 17.8 mg L−1, and 2.6 mg L−1, respectively (Fig. 2a). Under the influent COD of 173.3 mg L−1 in phase III, the effluent COD of 64.9 mg L−1 was higher than that of 24.8 mg L−1 in phase I (Fig. 2b). This study found that the effluent COD of the partial nitrification process was higher than the effluent COD of the complete nitrification process. In addition, this study demonstrated that stable partial nitrification was maintained with no ammonium remaining. Therefore, ammonium remaining was not the key to partial nitrification stabilization, but rather the strategy of stopping aeration in time when NH4+-N degradation was complete. This strategy differed from the previous study16.

Further nitrogen removal in D-SBR without carbon addition

The D-SBR was installed as a separate sludge system behind the PN-SBR to further treat its effluent. In phase I, the effluent was almost entirely nitrate, and effluent COD was low at 24.8 mg L−1 due to the complete nitrification process of the PN-SBR. Therefore, the influent to the D-SBR included not only the PN-SBR effluent, but also a portion of municipal wastewater which provided organic matter for the denitrification process to reduce nitrate. Subsequently, denitrification was coupled with anammox for synergistic nitrogen removal8. However, the inflow of municipal wastewater not only provided organic matter but also increased NH4+-N. Due to the limitation of anammox activity, the NH4+-N removal performance was unsatisfactory with effluent NH4+-N of 9.4 mg L−1.

In phase III, the influent of D-SBR was only the PN-SBR effluent (Supplementary Fig. S1). The effluent characteristics of PN-SBR were as follows NH4+-N (0.8 ± 1.3 mg L−1), NO2−-N (17.8 ± 2.7 mg L−1), NO3−-N (2.6 ± 1.1 mg L−1), and COD (64.9 ± 9.8 mg L−1). In D-SBR, denitrifying bacteria reduced nitrite and nitrate using the remaining organic matter in the PN-SBR effluent as electron donors. And high nitrogen removal performance was obtained, the effluent NH4+-N, NO2−-N, COD were 2.0 mg L−1, 0.6 mg L−1, 39.1 mg L−1, and NO3−-N was less than 0.1 mg L−1, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1). The long-term anoxic environment of D-SBR as a separate sludge system allowed it to be enriched with particular functional microorganisms. Moreover, the particular functional microorganisms allowed D-SBR to achieve a high level of nitrogen removal.

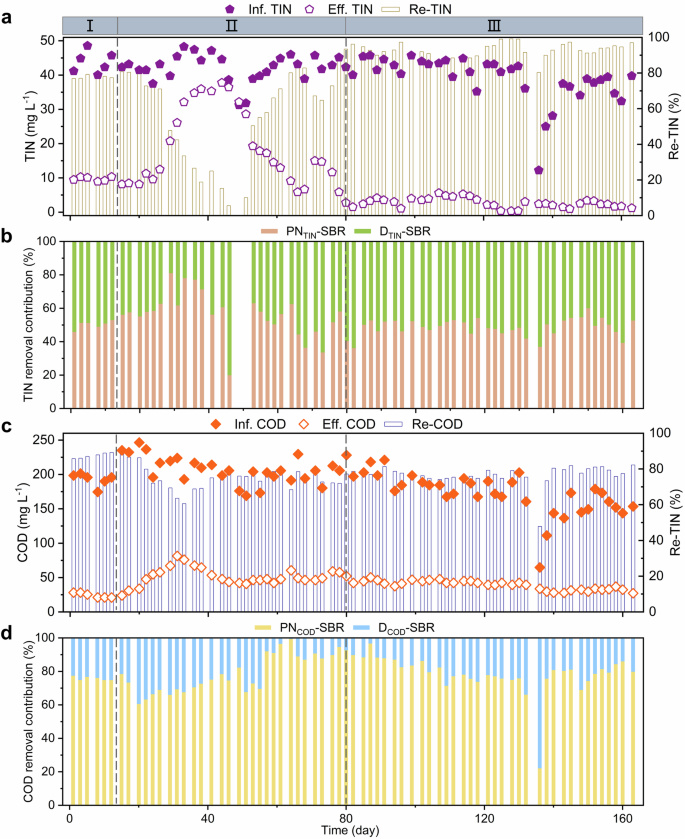

Nitrogen and COD removal contributions in PN-SBR and D-SBR

The double sludge system exhibited an effluent total inorganic nitrogen (TIN) of 9.7 ± 0.6 mg L−1 at an influent TIN of 43.8 ± 3.2 mg L−1 and TIN removal efficiency (Re-TIN) was 77.8 ± 0.8% in phase I. The PN-SBR and D-SBR contributed 50.4% and 49.6% to the TIN removal, respectively (Fig. 3a, b). Similarly, the effluent COD was 24.1 ± 3.5 mg L−1 at an influent COD of 192.7 ± 9.6 mg L−1, and the contributions of PN-SBR and D-SBR to COD removal were 75.9% and 24.1%, respectively (Fig. 3c, d).

a Influent total inorganic nitrogen (Inf. TIN, purple solid pentagons), effluent total inorganic nitrogen (Eff. TIN, purple hollow pentagons), total inorganic nitrogen removal efficiency (Re-TIN, deep yellow columns). b Contribution of partial nitrification sequencing batch reactor (PN-SBR) to TIN removal (PNTIN-SBR, light orange columns) and contribution of denitrification/anammox sequencing batch reactor (D-SBR) to TIN removal (DTIN-SBR, light green columns). c Influent chemical oxygen demand (Inf. COD, orange solid rhombus), effluent chemical oxygen demand (Eff. COD, orange hollow rhombus), chemical oxygen demand removal efficiency (Re-COD, navy blue columns). d Contribution of PN-SBR to COD (PNCOD-SBR, light yellow columns) and contribution of PN-SBR to COD (DCOD-SBR, light blue columns). I, II, and III at the top of the figure represent phase I, phase II, and phase III in the long-term operation of the system, respectively.

The partial nitrification + denitrification/anammox system was successfully started up and operated stably in phase III. The effluent TIN was decreased to 2.7 ± 1.4 mg L−1 at the influent TIN of 39.1 ± 6.6 mg L−1 and Re-TIN was increased to 92.8 ± 3.9%. The contributions of PN-SBR and D-SBR to TIN removal were 48.9% and 51.1%, respectively (Fig. 3a, b). Similarly, the effluent COD was 39.1 ± 6.8 mg L−1 at an influent COD of 173.3 ± 31.2 mg L−1, and the contributions of PN-SBR and D-SBR to COD removal were 79.0% and 21.0%, respectively (Fig. 3c, d). D-SBR accounted for only 21.0% of the COD removal, but contributed more to TIN removal than PN-SBR. The reduction of nitrite to nitrogen required 40% less carbon source than nitrate. This was the key to high-level nitrogen removal under low-carbon sources.

Nutrient transformation in the double sludge system

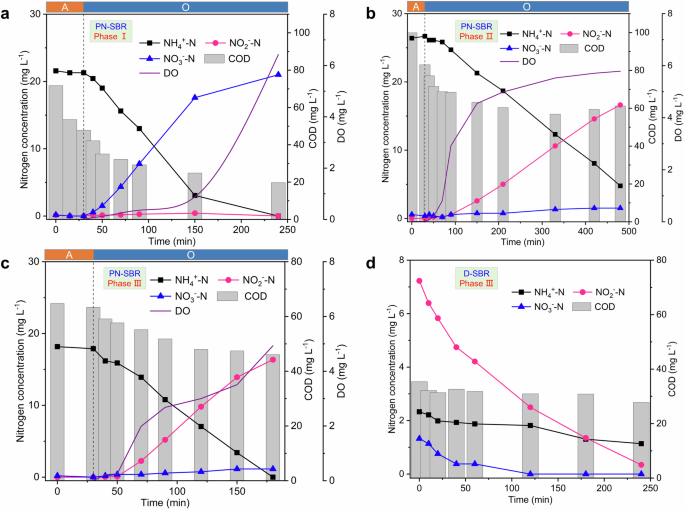

To obtain insights into nutrient transformations of the double sludge system (partial nitrification + denitrification/anammox), in-situ typical cycles of PN-SBR and D-SBR were analyzed (Fig. 4). The initial nutrient concentrations of a typical cycle were the concentrations of the mixed after feeding.

a Partial nitrification sequencing batch reactor (PN-SBR) in phase I. b PN-SBR in phase II. c PN-SBR in phase III. d Denitrification/anammox sequencing batch reactor (D-SBR) in phase III. NH4+-N (black solid squares), NO2−-N (pink solid circles), NO3−-N (blue solid triangles), chemical oxygen demand (COD, gray columns), and dissolved oxygen (DO, purple lines). For a–c a at the top of the figure represents the anoxic stage and O represents the aerobic stage.

The aerobic duration of the PN-SBR at phase I was 3.5 h. The oxidation of ammonia to nitrate without nitrite accumulation in the aerobic stage was observed in the typical cycle (Fig. 4a). NH4+-N was decreased from 21.6 mg L−1 to below the detection limit, and NO3−-N was increased to 21.0 mg L−1 in the aerobic stage. Additionally, COD was decreased from 47.8 mg L−1 to 19.7 mg L−1 in the aerobic stage.

Due to the organic loading shock, the activities of both AOB and NOB were inhibited, therefore, the aeration duration was extended to 7.5 h to enhance the nitrification activity. However, NOB was inhibited more than AOB, which contributed to the accumulation of nitrite in the aerobic stage (Fig. 4b). In phase III, the nitrification activity was gradually regained, and partial nitrification was stably maintained by the strategy of stopping aeration in time when NH4+-N degradation was complete. This strategy deprived the NOB of further growth. However, the DO was not controlled and increased to 4.9 mg L−1 at the end of the aerobic stage. NH4+-N was decreased from 18.0 mg L−1 to below the detection limit, and NO2−-N and NO3−-N were increased to 16.4 mg L−1 and 1.1 mg L−1 within 2.5 h of aeration duration, respectively. Similarly, a previous study had realized partial nitrification in a laboratory-scale SBR (working volume: 3 L) under a supply strategy of saturated DO with a DO concentration of about 7.2 mg L−1 20. COD was decreased from 63.4 mg L−1 to 46.1 mg L−1 in the aerobic stage, and COD was only reduced by 17.3 mg L−1 (Fig. 4c). The effluent COD of the PN process was higher than that of the complete nitrification process, and the effluent COD was attributed to the complex organic matter in the municipal wastewater and the soluble microbial products produced by the activated sludge. The mechanism responsible for the high effluent COD needed to be further investigated. In the D-SBR, NO2−-N was decreased from 7.2 mg L−1 to 0.3 mg L−1, and NO3−-N was decreased from 1.3 mg L−1 to below the detection limit within 4 h (Fig. 4d). COD was decreased from 35.4 to 27.8 mg L−1. Additionally, the typical cycle of D-SBR exhibited a decrease in NH4+-N from 2.3 mg L−1 to 1.1 mg L−1. Since the D-SBR had been operated as an anoxic process, the NH4+-N loss was considered to be attributed to anammox8. Of course, the typical cycle indicated that the reduction of NH4+-N was lower than that of NO2−-N. The reason for this was that nitrite was removed mainly by the denitrification process and a little by the anammox process. In conclusion, the presence of multiple nitrogen removal pathways contributed to a high level of nitrogen removal in D-SBR.

Transformation of organic matter

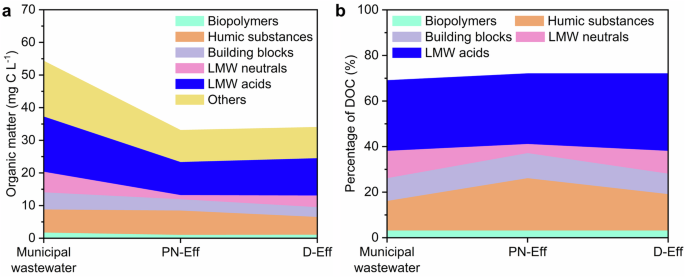

The transformation of dissolved organic matter was analyzed by LC-OCD-OND. The main dissolved organic matter were biopolymers, humic substances, building blocks, LMW neutrals, and LMW acids. Biopolymers, humic substances, building blocks, LMW neutrals and LMW acids in municipal wastewater were 1.64 mg C L−1, 7.08 mg C L−1, 5.24 mg C L−1, 6.32 mg C L−1, 16.92 mg C L−1, respectively (Fig. 5a). Among them, LMW neutrals and LMW acids with low MW accounted for the largest percentage of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) at 43%, while biopolymers with high MW accounted for the smallest percentage of DOC at 3% (Fig. 5b). After municipal wastewater was treated in the PN-SBR, humic substances increased from 7.08 mg C L−1 in municipal wastewater to 7.46 mg C L−1 in PN-SBR effluent, while all other components decreased. This suggested that the activated sludge in the PN-SBR produced soluble microbial products including humic substances. Previous studies indicated that humic substances were recognized in soluble microbial products produced by activated sludge21.

a Content of each organic component. b Percentage of each organic component in dissolved organic carbon (DOC). For a, b, Biopolymers (light cyan), Humic substances (light orange), Building blocks (light purple), LMW neutrals (light pink), LMW acids (blue), and others (light yellow). Municipal wastewater, PN-Eff, and D-Eff represent organic matter in municipal wastewater, partial nitrification sequencing batch reactor effluent (PN-Eff), and denitrification/anammox sequencing batch reactor effluent (D-Eff), respectively.

After D-SBR, humic substances decreased from 7.46 mg C L−1 to 5.44 mg C L−1 and building blocks decreased from 3.48 mg C L−1 to 3.00 mg C L−1. Building blocks were considered to be degradation products of humic substances. LMW neutrals and LMW acids increased from 10.14 mg C L−1 and 1.26 mg C L−1 to 11.46 mg C L−1 and 3.56 mg C L−1, respectively (Fig. 5a). The percentage of humic substances and building blocks in DOC decreased from 23% and 11% to 16% and 9%, respectively. In contrast, the percentage of LMW neutrals and LMW acids in DOC increased from 31% and 4% to 34% and 10%, respectively (Fig. 5b). Overall, the microorganisms in the D-SBR were able to degrade humic substances and building blocks with high MW.

Microbial community evolution in PN-SBR and D-SBR

Microbial community evolution of PN-SBR and D-SBR were analyzed to decode the variations in functional microorganisms and the causes of high levels of nitrogen removal in the double sludge system.

In microbial alpha diversity, both Shannon and Sobs indexes in both PN-SBR and D-SBR exhibited reductions concomitant with the successful start-up of the partial nitrification + denitrification/anammox system. The Shannon and Sobs indexes of PN-SBR decreased from 5.62 and 1784 to 4.38 and 959, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S2). The Shannon and Sobs indexes of D-SBR decreased from 6.11 and 2197 to 5.29 and 1541, respectively.

In PN-SBR, Proteobacteria was the most dominant phylum and the relative abundance further increased to 60.83% in phase III (Supplementary Fig. S3). In D-SBR, the main phylum included Proteobacteria, Chloroflexi, Bacteroidota, and Acidobacteriota. Chloroflexi was reported to utilize organic matter including microbial products of biomass decay22,23. Bacteroidota and Acidobacteriota played a role in degrading complex organic matter24. In this study, the relative abundance of Chloroflexi increased from 18.27% to 24.72% and the relative abundance of Acidobacteriota increased from 6.68% to 9.14%. This contributed to the fact that D-SBR could utilize complex organic matter for nitrogen removal.

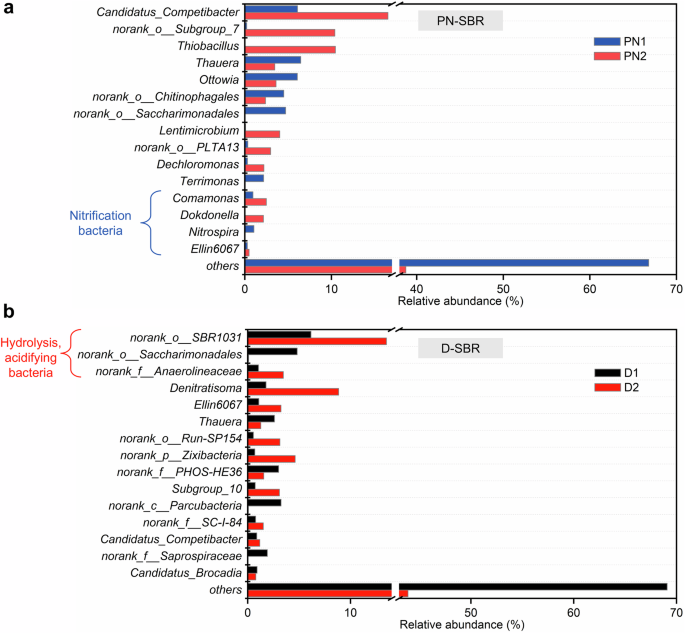

At the genus level, Nitrospira, a known NOB, was almost entirely eliminated as its relative abundance decreased from 1.05% to less than 0.01% in PN-SBR (Fig. 6a). The almost entire elimination of Nitrospira contributed to the accumulation of nitrite and was critical for the stable maintenance of the partial nitrification. In addition, other ammonia removal bacteria Comamonas and Dokdonella were also enriched, increasing in relative abundance from 0.93% and 0.03% to 2.49% and 2.15%, respectively. Previous studies showed that Comamonas was necessary for heterotrophic ammonia removal and had the potential for ammonia assimilation25. Dokdonella was not only a nitrifying microorganism but also an aerobic denitrification microorganism. Previous studies showed that the aerobic denitrifying microorganism Dokdonella would compete for nitrite and DO with NOB26,27. This may lead to the elimination of NOB. Candidatus_Competibacter and Thiobacillus belonging to denitrifying bacteria were enriched in PN-SBR. The previous study showed that Thiobacillus was enriched when nitrification deteriorated28. In this study, the relative abundance of Thiobacillus increased from less than 0.01–10.46%. In PN-SBR, the organic loading shock deteriorated the nitrification activity, which may have led to the enrichment of Thiobacillus.

a Evolution of microbial community in the partial nitrification sequencing batch reactor (PN-SBR) at the genus level, with PN1 representing phase I (dark blue columns) and PN2 representing phase III (light red columns), respectively. b Evolution of microbial community in the denitrification/anammox sequencing batch reactor (D-SBR) at the genus level, with D1 representing phase I (black columns) and D2 representing phase III (red columns), respectively.

In D-SBR, the relative abundance of norank_o__SBR1031 and norank_f__Anaerolineaceae increased from 6.16% and 1.05% to 13.50% and 3.46%, respectively (Fig. 6b). Both norank_o__SBR1031 and norank_f__Anaerolineaceae were fermentative bacteria involved in the process of hydrolysis and acidification of organic matter29,30,31. The enrichment of hydrolyzing and acidifying bacteria contributed to the full utilization of organic matter to achieve a high level of nitrogen removal. The relative abundance of Denitratisoma increased from 1.78% to 8.84%, and Denitratisoma became the most dominant denitrifying bacteria genus. Previous studies indicated that Denitratisoma can also be involved in the degradation of organic matter32. In addition, the relative abundance of Thauera decreased from 2.60% to 1.28% and the relative abundance of norank_o__Run-SP154 increased from 0.55% to 3.13%. Previous studies indicated that Thauera was a typical denitrifying bacteria and norank_o__Run-SP154 was a denitrifying phosphorus-accumulating bacteria (endogenous denitrifying bacteria)33,34. The enrichment of endogenous denitrifying microorganisms allowed the D-SBR to utilize endogenous carbon sources for denitrification to contribute to nitrogen removal. In addition, Candidatus_Brocadia, a known anammox bacteria, was consistently found in the D-SBR8. Its relative abundance was 0.79% in phase III. This also explained the anammox observed in the D-SBR.

In conclusion, this double sludge system enabled the PN-SBR and D-SBR to individually enrich functional microorganisms, which in combination with each other resulted in a high level of nitrogen removal.

Discussion

Advantages and feasibility of the double sludge system

This double sludge system consisted of pilot-scale PN-SBR and D-SBR, and its high level of nitrogen removal was attributed to the close cooperation between these two sludge systems. In phase I, the complete nitrification + denitrification/anammox process was operated resulting in effluent TIN of 9.7 mg L−1. In phase III, the partial nitrification + denitrification/anammox system was operated stably to obtain effluent TIN of 2.7 mg L−1 (Fig. 3). The realization of partial nitrification in PN-SBR reduced the carbon source required for the subsequent denitrification process in D-SBR, which contributed to improvement in the nitrogen removal performance of the system. Additionally, previous studies indicated that suitable ecological conditions for both nitrifying and denitrifying bacteria needed to be created in an integrated simultaneous nitrification and denitrification (SND) process. This required suitable reactor operating conditions including DO, pH (about 7.5), food/microorganism (F/M) ratio, and carbon/nitrogen (C/N) ratio35. Previous studies showed that low DO and high influent organic matter were favorable for simultaneous nitrification and denitrification processes. However, denitrification rates were slower in the simultaneous nitrification and denitrification system compared to the single sludge system. Similarly, in integrated simultaneous partial nitrification-denitrification (SPND) systems, low DO control was also required to improve system performance36. In addition, the simultaneous partial nitrification-denitrification system treating domestic wastewater had a high concentration of nutrients (effluent TIN of 35.2 mg L−1, effluent COD of 47.9 mg L−1) in the effluent, and its effluent would need further treatment37. In this study, the separate D-SBR sludge system could fully utilize organic matter for denitrification. In addition, a previous study showed that partial nitrification was maintained stably by the strategy of controlling the remaining NH4+-N to 8.3 mg L−1, but an external polishing device was generally required in order to meet the required emission standards16. This study excluded ammonium remaining as a control strategy, which would meet the standard for NH4+-N in effluent. Overall, the double sludge system proposed in this study provided advantages and feasibility for the treatment of municipal wastewater. Limited to manual working conditions and self-control of the equipment, this system was operated for one cycle per day. Therefore, the performance and stability of this system needed to be further investigated in the engineering application, when the operation mode of one cycle per day was shifted to full load operation. In addition, experiencing complex influent conditions including high salinity and heavy metals in the influent, the performance and stability of this system would still need to be further investigated.

Key factors of the double sludge system

On the one hand, the transformation from complete nitrification to partial nitrification in PN-SBR was the key factor to the high level of nitrogen removal. Firstly, partial nitrification was started up by simultaneous inhibition of AOB and NOB activity in response to organic loading shock, with AOB being recovered but not NOB by the strategy of extending the aeration duration. Secondly, partial nitrification was stably maintained by the strategy of stopping aeration in time when NH4+-N degradation was complete. Specifically, aerobic duration was determined based on the profile of NH4+-N in the full cycle in this study. However, the PN-SBR was not equipped with real-time NH4+-N monitoring equipment. However, when real municipal wastewater NH4+-N (39.1 ± 6.6 mg L−1) and COD/TIN (4.5 ± 0.4) fluctuations were low, the duration of aeration required was approximately the same (Table 1). In the partial nitrification stabilization phase, the almost entire elimination of Nitrospira, a known NOB, contributed to the accumulation of nitrite and was critical for the stable maintenance of the partial nitrification. Either an excessive or short aeration duration would be detrimental to the TIN removal performance of the system, thus adapting the appropriate aeration duration by monitoring the profile of NH4+-N would be critical. In addition, this study found that effluent COD from partial nitrification (64.9 ± 9.8 mg L−1) was much higher than that from complete nitrification (24.8 ± 3.3 mg L−1). This provided D-SBR with organic matter for denitrification.

On the other hand, the long-term anoxic operating conditions of D-SBR resulted in high microbial alpha diversity, and the cooperation of multiple microorganisms allowed it to achieve a high level of nitrogen removal. In addition, Candidatus_Brocadia, a known anammox bacteria, was consistently found in the D-SBR. Moreover, anammox contributed 26.1% of nitrogen removal in D-SBR based on typical cycle nitrogen variation. Therefore, the presence of multiple nitrogen removal pathways contributed to a high level of nitrogen removal in D-SBR.

Implications of the double sludge system

Compared to conventional nitrification/denitrification, this double sludge system (partial nitrification + denitrification/anammox) can reduce the aeration energy consumption and achieve high nitrogen removal without carbon addition. The AOB oxidized ammonia to nitrite instead of nitrate during the partial nitrification process using the oxygen from the aeration equipment, thus the partial nitrification process theoretically saved 25% of the aeration energy consumption13. This study provided ideas for upgrading municipal WWTPs to meet more stringent effluent nitrogen standards and carbon emission reductions, as well as insights into the stable maintenance of partial nitrification in mainstream municipal wastewater. Importantly, since the aeration time was adjusted based on manual measurement of the full cycle, the time when NH4+-N degradation was complete was not accurately captured. In future engineering applications, the use of real-time NH4+-N measurement devices to control the aeration duration, the system would be expected to achieve even better performance.

Methods

Pilot-scale reactors and operations

The pilot-scale double sludge system (partial nitrification + denitrification/anammox) consisted of two sequencing batch reactors for partial nitrification and denitrification/anammox, respectively (Fig. 1). The PN-SBR and D-SBR were both operated at ambient temperature in Beijing, China (March–August). The working volumes of the PN-SBR and D-SBR were 12 m³ and 8.4 m³, respectively, with a discharge ratio of 50% per cycle.

Restricted to working conditions, both the PN-SBR and D-SBR were operated for one cycle per day. The operation of PN-SBR consisted of feeding (1/3 h), anoxic stage (0.5 h), aerobic stage (2.5–7.5 h), settling (2.5 h), supernatant discharge (2/3 h), and the rest of the day was idle (12.5–17.5 h). Full cycle measurements were conducted every two weeks, and the aerobic stage duration was determined based on the NH4+-N profile during the full cycle. The hydraulic retention time (HRT) of PN-SBR was 13–23 h, with anoxic HRT of 1 h and aerobic HRT of only 5–15 h. The supernatant from the PN-SBR was discharged to an intermediate tank, which would be pumped into the D-SBR for further treatment. During the long-term operation, a blower was used to supply DO to the PN-SBR through microporous diffusers. The aeration volume of PN-SBR in the aerobic stage was maintained at 15 m3 h−1, and the DO concentration at the end of the aerobic stage was more than 4.9 mg L−1. The inoculum of the PN-SBR was activated sludge with complete nitrification and denitrification functions8. After inoculation, the MLVSS of the PN-SBR was 4.5 g L−1. According to the transformation of the PN-SBR from complete nitrification to partial nitrification, the long-term operation was divided into three phases, phase I (complete nitrification, days 1–13), phase II (gradual realization of partial nitrification, days 14–79), and phase III (stabilization of partial nitrification, days 80–163). During days 1–20, MLVSS was reduced from 4.5 g L−1 to 3.5 g L−1 by discharging 150 L of mixed sludge per day at the end of the aerobic stage. During days 21–163, MLVSS was maintained at about 3.5 g L−1, and no sludge was discharged.

The operation of D-SBR consisted of feeding (1/5 h), anoxic stage (10 → 4 h), settling (2.5 h), supernatant discharge (4/5 h), and the rest of the day was idle (10.5-16.5 h). The HRT of D-SBR was 15-27 h, with anoxic HRT of 8–20 h. During days 1–56, the influent to the D-SBR included not only the PN-SBR effluent, but also a portion of municipal wastewater. During days 57–163, the D-SBR influent was only the PN-SBR effluent. The D-SBR consistently did not discharge sludge during long-term operation, but its MLVSS was reduced from 2.9 g L−1 to 2.5 g L−1. Systematic sludge reduction required further research.

Wastewaters

This pilot-scale double sludge system was located in a municipal WWTP in Beijing, China, and its influence was consistent with the WWTP’s influent as actual municipal wastewater. Municipal wastewater was characterized as follows NH4+-N (40.7 ± 5.7 mg L−1), NO2−-N and NO3−-N (<0.1 mg L−1), COD (188.4 ± 30.1 mg L−1). The specific characteristics of each phase are shown in Table 1.

Analytical methods and calculations

Sampling time for influent was 9:00 a.m.–10:00 a.m. BST. The effluent was collected from the supernatant of the settling stage. Then the samples were measured. NH4+-N, NO2−-N, NO3−-N, and COD in all water samples were detected by standard methods, and all water samples were filtered through medium-rate qualitative filter paper before detection38. Specifically, NH4+-N was measured with Nano reagent spectrophotometry, NO2−-N was measured photometrically with N-(1-naphthyl)-ethylenediamine spectrophotometric, NO3−-N was measured with ultraviolet spectrophotometry. NH4+-N, NO2−-N, NO3−-N were measured by DR6000 UV spectrophotometer (HACH, America). COD was measured using a 5B-3(C) COD Rapid Analyzer (Lianhua Technology Co., Ltd., China). DO in typical cycles was detected by a DO probe (Multi 3420, WTW Company).

NAR was used to characterize the performance of partial nitrification according to Eq. (1).

Where NO2−-NPN-e and NO3−-NPN-e represent NO2− and NO3− concentration in PN-SBR effluent.

The contribution of PN-SBR to TIN removal (PNTIN-SBR) and the contribution of D-SBR to TIN removal (DTIN-SBR) of the double sludge system (partial nitrification + denitrification/anammox) was determined as follows Eqs. (2 and 3). The contribution of PN-SBR to COD removal (PNCOD-SBR) and the contribution of D-SBR to COD removal (DCOD-SBR) of the double sludge system (partial nitrification + denitrification/anammox) were determined as follows Eqs. (4 and 5).

Where NH4+-Ni represents NH4+ concentration in municipal wastewater and NH4+-NPN-e represents ammonium concentration in PN-SBR effluent. TINi represents TIN concentration in municipal wastewater and TINe represents TIN concentration in partial nitrification + denitrification/anammox system effluent. V-PNE represents the volume of PN-SBR effluent in the D-SBR influent. V-M represents the volume of municipal wastewater in the D-SBR influent. CODi represents COD concentration in municipal wastewater and CODPN-e represents COD concentration in PN-SBR effluent. CODe represents COD concentration in partial nitrification + denitrification/anammox system effluent.

Organic carbon analysis

DOC in municipal wastewater, PN-SBR effluent, and D-SBR effluent was analyzed for an operating cycle in phase III. All water samples were filtered through a 0.22 μm filter membrane before analysis. Then, the DOC of samples was detected by LC-OCD-OND39. Dissolved organic carbon was grouped according to molecular weight (MW) in the detection results as biopolymers (MW > 20,000 Da), humic substances (MW 1000–20,000 Da), building blocks (MW 300–500 Da), and LMW neutrals and LMW acids (MW < 350 Da)40.

16S rRNA high-throughput sequencing

The evolution of microbial communities in the double sludge system was revealed by 16S rRNA high-throughput sequencing. Sludge samples were collected for lyophilization using a lyophilizer from phase I (day 10) and phase III (day 151) in PN-SBR and D-SBR, respectively. DNA was extracted from sludge samples and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the V3 and V4 regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA genes was performed using forward primer 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3′) and reverse primer 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′)41. The amplification products were analyzed on the Illumina Miseq PE300. The OTU (operational taxonomic units) clustering was performed using Usearch 7.1 software according to 97% similarity, and similar sequences were grouped into one OTU. The OTU representative sequences were matched with sequences from the silva database using the RDP classifier Bayesian algorithm, and microbial communities were analyzed at the phylum and genus level in the samples. The raw data had been uploaded to the SRA database at NCBI (accession no. SRP507907).

Responses