piRNA28846 has the potential to be a novel RNA nucleic acid drug for ovarian cancer

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death among gynecologic cancers wordwide1. Notwithstanding significant advancements in research, screening and treatment, survival rates for ovarian cancer have seen limited improvement over decades2. While early-stage ovarian cancer is curable in 90% of patients, most women are diagnosed at a later stage. Each year, there are ~239,000 new cases and 152,000 deaths from ovarian cancer globally3. This late diagnosis poses significant challenges to the effectiveness of surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapies.

Targeted therapy, known for its precision, high efficacy, and minimal side effects, is gradually being introduced into clinical trials. Traditional targeted drugs primarily consist of small molecules and proteins, which mainly target cell surface receptors and circulating proteins. However, these drugs often struggle to enter specific protein conformations, limiting their ability to target many disease-causing proteins and, consequently, restricting their therapeutic effectiveness4.

RNA therapeutics are emerging as a more precise and effective targeting strategy5. Its natural biocompatibility and low immunotoxicity provide RNA with a significant advantage in tumortherapy6.

Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are the two most commonly used types of nucleic acid therapy7. Both ASO and siRNA drugs are highly specific and selective, allowing them to precisely target oncogenes in tumor cells. They achieve this by complementing the target mRNA, leading to its degradation and a subsequent reduction in protein expression8. However, these therapies also have drawbacks. ASO has a short half-life and can exhibit some toxicity, which typically manifests as inflammation, thrombocytopenia, and hepatorenal toxicity9,10. On the other hand, siRNA can give rise to off-target effects, resulting in unintended silencing of genes that should remain active. This not only diminishes the silencing efficacy of target genes but can also lead to undesirable effects by silencing genes that should not be affected.

Therefore, we are trying to find the small RNAs that are naturally present in human cells and exhibit anti-cancer effects, with the aim of inhibiting the occurrence and progression of cancer by increasing their expression. Unlike the off-target effects associated with siRNA, since RNA itself exerts an anti- cancer function in vivo through a complex mechanism of action. Thus, theoretically, enhancing the expression of these small RNAs will strengthen their overall anti-cancer efficacy. To investigate this, we performed Pandora sequencing on four pairs of clinical samples from ovarian cancer and normal tissues. Through differential analysis, we discovered that piR-28846 was expressed at low levels in ovarian cancer tissues. By further increasing our sample size, we confirmed that the expression of piR-28846 in ovarian cancer tissue was indeed lower than that in normal ovarian tissue.

To further investigate whether overexpressing piR-28846 has a therapeutic effect in ovarian cancer. We introduced a piR-28846 mimic, which mimics the function of naturally occurring piRNA in the body, into ovarian cancer cells. Our findings indicate that overexpressing piR-28846 inhibits ovarian cancer cell growth and promote apoptosis. piRNAs are small non-coding RNA molecules of ~24–31 nucleotides in length11,12, processed from single-stranded RNA precursors that are mainly transcribed from specific intergenic repeat elements known as piRNA clusters13. The eukaryotic Argonaute family is divided into AGO-branched and PIWI-branched subfamilies14, AGO proteins universally express and bind miRNAs or siRNAs, while PIWI proteins specifically interact with piRNAs15. Unlike siRNAs, piRNAs are produced independently of Dicer from single-stranded precursor14,15 transcripts with 2′-O- methyl (2′-O-Me) modification at their own 3’ end16,17,18. The presence of 2′-O-methyl (2′-O-Me) modification makes them more stable. However, delivering nucleic acids to other organs remains a challenge. It has been reported that cholesterol siRNAs coupling can deliver siRNAs into cells without the use of transfection agents and is more effective than other lipophilic ligands in participating in RNA interference. Thus, we added cholesterol modification to the 5’ end of piR-28846, creating the chemical modifier agopiR-28846. We then administered agopiR-28846 to the ovarian cancer xenograft tumors and 3D ovarian cancer organoid model. The results demonstrated that the growth of both the xenograft tumors and ovarian cancer organoids was effectively inhibited. Therefore, agopiR-28846 may serve as a potential nucleic acid drug with therapeutic applications in ovarian cancer.

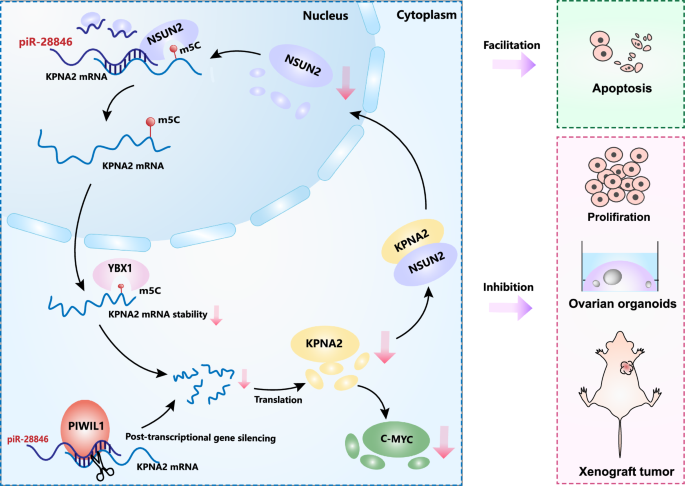

To further explore the mechanism of action, we performed an in-depth study of how piR-28846 exerts its anticancer effect in cells. We discovered that piR- 28846 binds to NSUN2 and down-regulates its expression, which simultaneously reduces the modification level of m5C. Additionally, the stability of KPNA2 mRNA is decreased, resulting in lower KPNA2 protein expression. Furthermore, there is feedback regulatory relationship between KPNA2 and NSUN2, ultimately leading to decreased KPNA2 expression and exerting the inhibitory effect on ovarian cancer.

Results

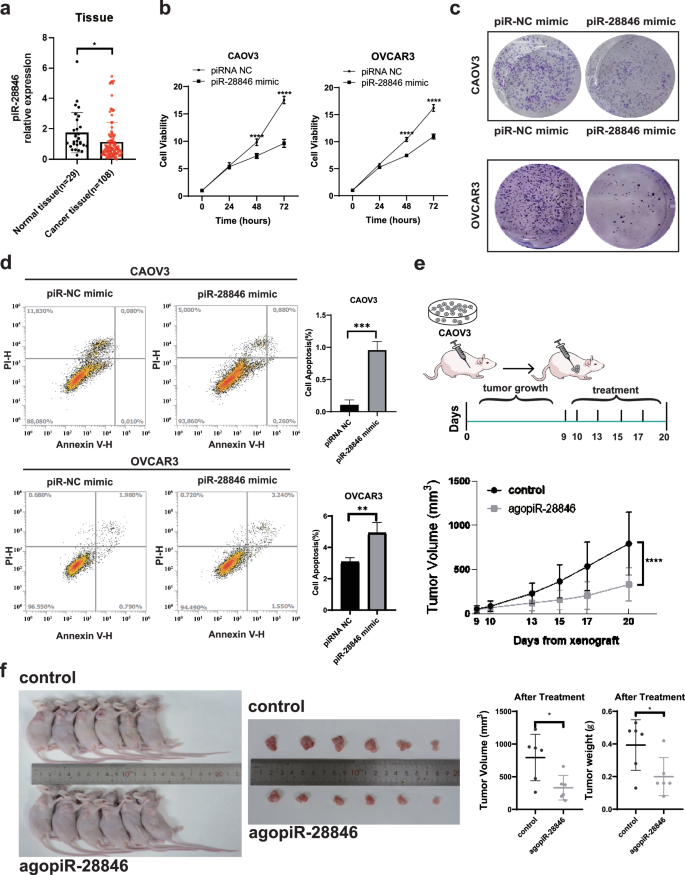

piR-28846 expression was low in clinical ovarian cancer tissue samples

Tumor formation is driven by the dysregulation of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. ASOs and siRNA are the two most commonly used methods of nucleic acid therapy7, both of which achieve gene therapy by inhibiting the expression of target genes4,19. We aimed to look for small RNAs that are naturally present in human cells and possess inhibitory effects on cancer. By enhancing their inhibitory effect, we can achieve our goal of effective gene therapy. Our screening for differentially expressed piRNAs in ovarian cancer using Pandora-Seq differential analysis revealed decreased expression of piR-28846 in ovarian cancer [Supplementary Fig. 1a]. Through RIP experiments, we found that piR- 28846 binds to PIWIL1, which is also known as PIWIL1-interacting RNA [Supplementary Fig. 1b]. Furthermore, Q-PCR analysis of piRNA levels in normal tissue (n = 29) and ovarian cancer samples (n = 108) collected from the Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University demonstrated that the expression level of piR-28846 in normal ovarian tissue was significantly higher than that in ovarian cancer tissue (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1a). These results suggest that the down-regulation of piR-28846 expression may be associated with the occurrence of ovarian cancer.

aThe expression levels of piR-28846 in ovarian cancer tissue specimens (n = 108) and normal ovarial tissue specimens (n = 29) was detected by q-PCR. b The effect of piR-28846 expression on cellular growth was detected by CCK-8 assay. c Community aggregation experiments showed that overexpression of piR-28846 inhibited the formation of ovarian cancer cell communities. d piR-28846 overexpression promoted apoptosis. e CAOV3 was inoculated into nude mice, and the growth rate of the tumor was significantly slowed down after agopiR-28846 treatment compared with control group. f The volume and weight of the xenograft tumor.

piR-28846 inhibits the proliferation and promotes apoptosis of ovarian cancer cells

To further investigate whether the expression of piR-28846 is related to the occurrence and development of ovarian cancer, we overexpressed piR-28846 mimic in ovarian cancer cell lines (CAOV3 and OVCAR3, which showed lower piR-28846 expression, Supplementary Fig. 1c, d). The overexpression of piR- 28846 significantly decreased the proliferation of CAOV3 and OVCAR3 cells, as demonstrated by CCK-8 assays (Fig. 1b). Colony formation assays yielded similar results (Fig. 1c). Additionally, the overexpression of piR-28846 induced apoptosis in both cell lines (Fig. 1d). These observations suggested that piR- 28846 effectively inhibits the development of ovarian cancer cells.

piR-28846 has a therapeutic effect

An increasing number of approved RNA nucleic acid therapies are making disease treatment more precise and personalized20. The antitumor effect of piR- 28846 in ovarian cancer cells suggests that it may be a potential small nucleic acid drug.

It is a challenge to deliver naked RNA into the bloodstream, where it can be degraded by serum nucleases21,22. A common strategy to address this issue is the chemical modification of the siRNA backbone, typically by incorporating 2’- O-methyl (2’-O-Me) or 2’-F modification23,24. Unlike siRNAs, piRNAs are produced from single-stranded precursor transcripts independently of Dicer14,15 and possess 2’-O-methylation at their 3’ end16,17,18, which contributes to their stability. However, delivering nucleic acids to other organs remains a challenge. Literature suggests that coupling cholesterol to siRNAs can facilitate their delivery into cells without the use of transfection agents25 and is more effective than other lipophilic ligands in participating in RNA interference26. Intramuscular or subcutaneous injection of cholesterol couplers ensures retention and slow diffusion at the local site of administration27. This approach not only increases the hydrophobicity of the coupler28,29 that is conducive to avoiding rapid clearance from the bloodstream via renal filtration but also leverages natural cholesterol transport mechanisms into cells30.Therefore, we added a cholesterol modification to the 5’ end of piR-28846, which itself contains 2’-O- methyl (2’-O-Me), creating the chemical modifier agopiR-28846.

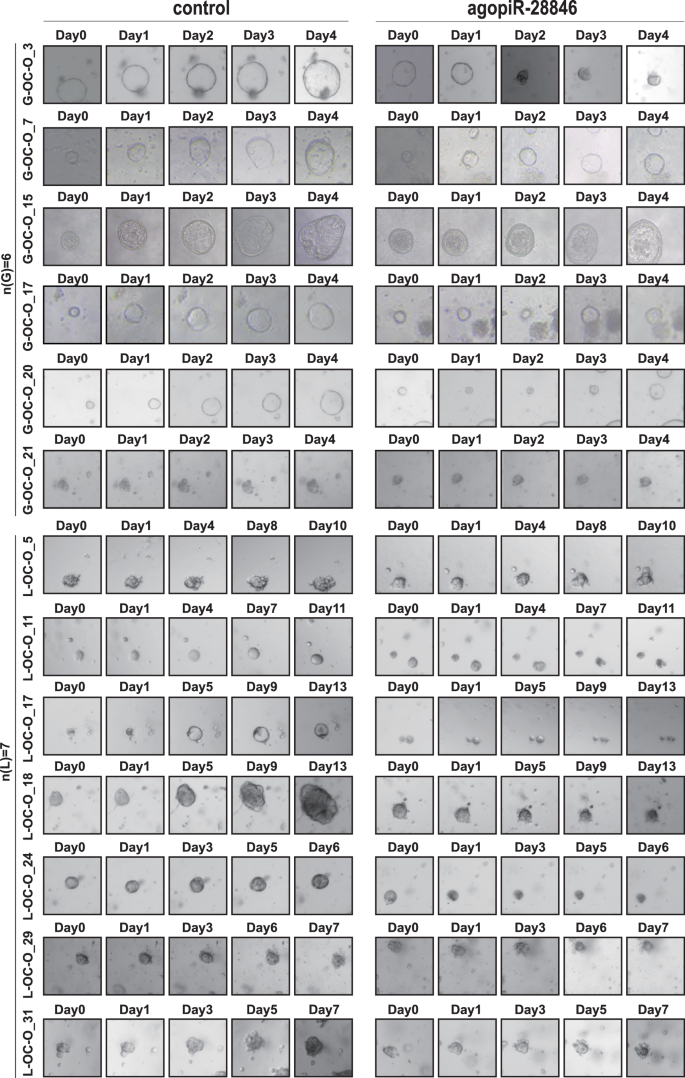

To further investigate whether agopiR-28846 can function therapeutically as a small nucleic acid drug, we established a xenograft model using CAOV3 ovarian cancer cells in nude mice to further research its therapeutic effect. Once the xenograft tumors reached a certain size, we injected agopiR-28846 into the xenograft tumors. We found that agopiR-28846-treated xenograft tumors grew significantly slower compared to tumors (Fig. 1e). The volume and weight of agopiR-28846-treated xenografts were significantly smaller than those of the controls (Fig. 1f). Additionally, we also collected tissue samples from 13 ovarian cancer cases, constructed corresponding ovarian cancer organoid models. We observed that the growth rate and the size of agopiR-28846-treated ovarian cancer organoids were significantly smaller than those of untreated ovarian cancer organoids (Fig. 2). These results indicate that agopiR-28846 has a significant therapeutic effect in both the ovarian cancer organoid model and xenograft tumor model.

Addition of agopiR-28846 to the ovarian cancer organoid model for treatment resulted in a significant reduction in growth rate in the treated group compared to the control group(n = 13).

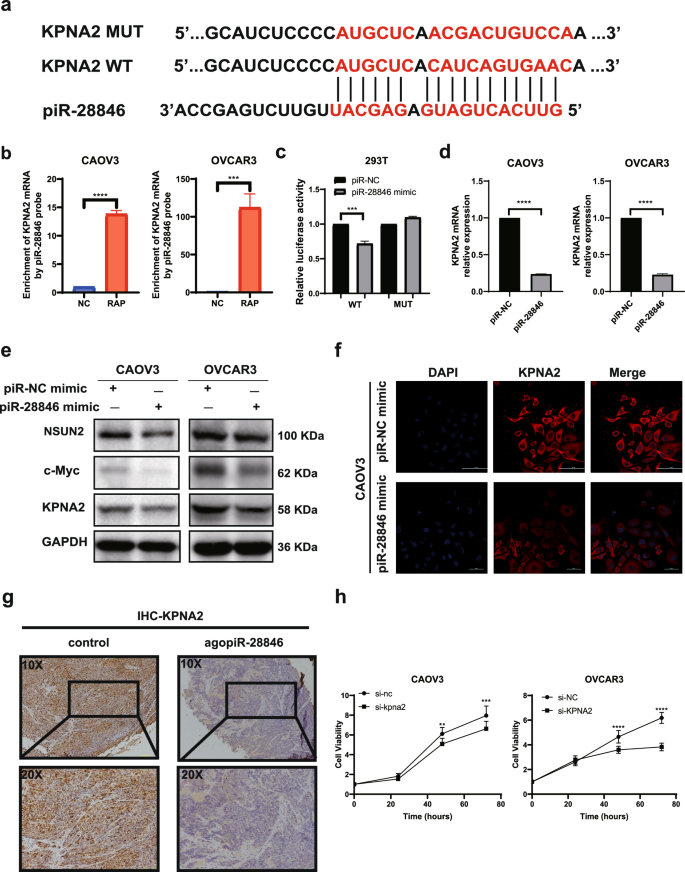

piR-28846 binds to KPNA2 mRNA and affects its protein expression

Various studies indicated that piRNA-PIWI complex can be involved in post-transcriptional networks in the cytoplasm, and regulate post-transcr iptional networks through piRNA-RNA interaction. An effective piRNA-RNA interaction requires strict base pairing within 2–11nt at the 5′ end of the piRNA, while base pairing within 12-21nt31 is less stringent. To identify co mplementary genes with the piR-28846 base sequence (5’-GTTCACTGAT GAGAGCATTGTTCTGAGCCA-3’), we used the BLAST website (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). KPNA2 exhibited the highest ratio of compl ementary base pairing ratio with piR-28846, showing only one consistent site with the strict base pairing within 2–11nt at the 5’ end of piRNA (Fig. 3a).

a piR-28846 is paired with KPNA2 mRNA bases. b RNA antisense Purification test verified that piR-28846 was bound to KPNA2 mRNA. c Reporter gene experiments showed that piR-28846 was bound by complementary base pairing sequences. d The expression levels of KPNA2 mRNA after overexpression of piR-28846. e Related proteins expressed following overexpression of piR-28846. f Immunofluorescence showed that the intracellular expression of KPNA2 decreased after overexpression of piR-28846 in CAOV3. g Compared with the control group, the expression of KPNA2 in xenografts treated with agopiR-28846 was significantly reduced. h Effect of KPNA2 expression on the growth of ovarian cancer cells.

First, we used the piR-28846 probe to confirm the binding of piR-28846 to KPNA2 mRNA through RAP experiments (Fig. 3b). We constructed a plasmid that predicted the binding site mutation, and further validated the interaction between piR-28846 and the presumed KPNA2 mRNA binding site using a dual luciferase reporter gene assay (Fig. 3c). Overexpression of piR-28846 significantly decreased the luciferase activity of the reporter construct containing wild-type KPNA2 compared to the control. However, mutating the putative binding site abrogated this decrease. Q-PCR experiments indicated that overexpressing piR-28846 decreased KPNA2 mRNA expression (Fig. 3d). Additionally, western blotting (Fig. 3e) and immunofluorescence experiment (Fig. 3f) demonstrated that overexpressed piR-28846 in ovarian cancer cell lines led to decreased expression of KPNA2 compared with the control group. Furthermore, in xenograft models treated with agopiR-28846, immunohistochemistry revealed a significant reduction in KPNA2 expression (Fig. 3g).

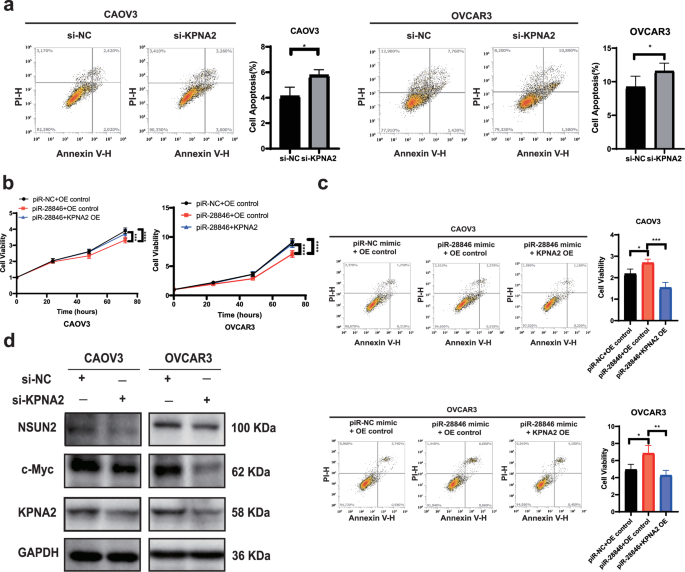

KPNA2 has been implicated in the development of several cancers, including breast, lung and ovarian cancer32,33,34. Previous studies have found that overexpression of KPNA2 in ovarian cancer is associated with poor prognosis35,36. To investigate this further, we knocked-down KPNA2 in ovarian cancer cell lines. Compared to the control group, we observed a decrease in cell proliferation (Fig. 3h) and an increase in apoptosis (Fig. 4a), which aligned with the cell phenotype observed when piR-28846 was overexpressed. Additionally, we overexpressed KPNA2 in ovarian cancer cell lines that also overexpressed piR-28846 and found that the effects of piR-28846 on cell proliferation (Fig. 4b) and apoptosis (Fig. 4c) were reversed. These results suggest that piR-28846 plays a role in inhibiting cancer by regulating the expression of KPNA2.

a Down-regulated KPNA2 expression promotes the apoptosis of ovarian cancer cells. b Overexpression of KPNA2 can reverse the inhibitory effect of piR-28846 on ovarian cancer cells. c Overexpression of KPNA2 can reverse the apoptosis level of piR-28846 on ovarian cancer cells. d Expression of related proteins after KPNA2 knock-down in ovarian cancer cells.

Previous studies have demonstrated a close association between KPNA2 and c-Myc. For example, KPNA2 promotes metabolic reprogramming of glioblastoma by regulating c-Myc37; and it enhances the proliferation and tumorigenicity of epithelial ovarian cancer cells by upregulating c-Myc34. The products of c-Myc expression play a crucial role in cell growth, proliferation, and tumorigenesis. In our experiments, we observed that c-Myc protein levels decreased when KPNA2 was knocked down in ovarian cancer cells (Fig. 4d), which is consistent with previous reports.

In conclusion, the overexpression of piR-28846 in ovarian cancer cells resulted in decreased levels of KPNA2 and downregulated c-Myc expression, thereby exerting a tumor suppressive effect.

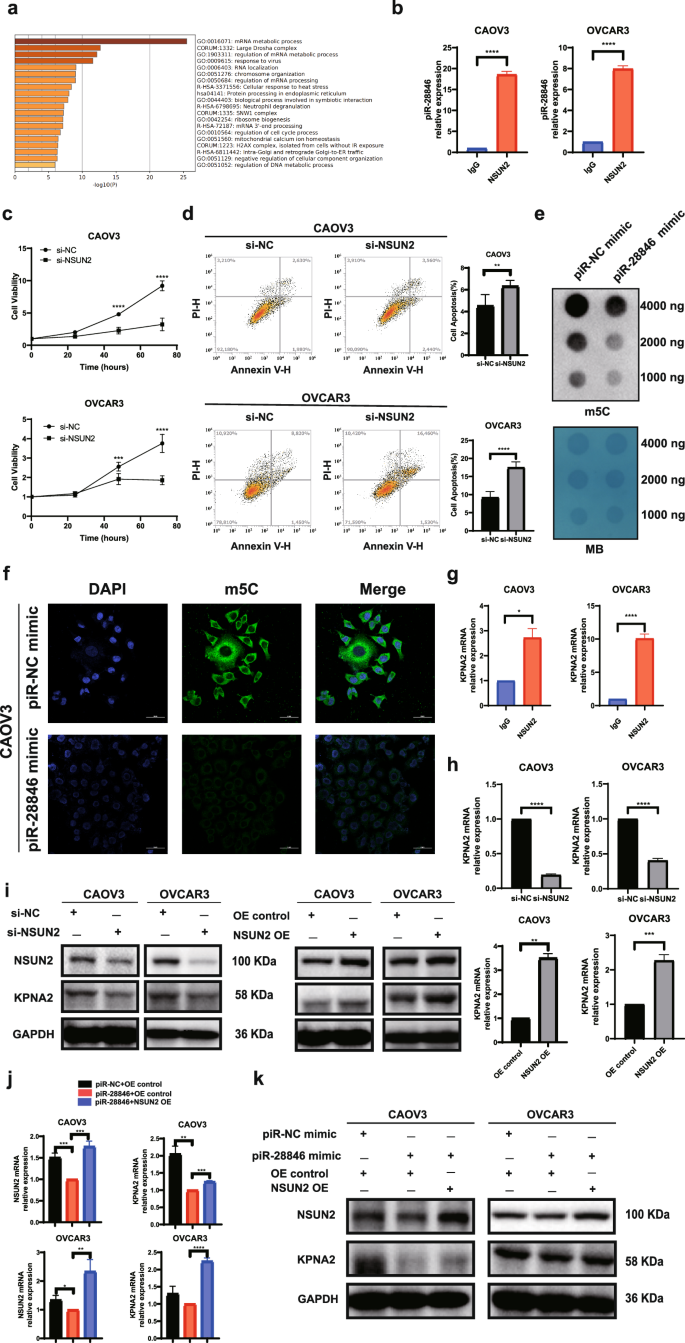

Binding of piR-28846 to NSUN2 downregulates its expression and downregulates m5C modification levels

piRNAs exhibit a complex molecular mechanism. They not only mediate post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) but can also participate in protein interactions31. we observed distinct specific bands corresponding to the piR- 28846 probe during the piR-28846 pull-down and Coomassie blue staining experiments. We selected the bands where the piR-28846 probe was located for MS analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1e). KEGG enrichment analysis (Metascape) of the mass spectrometry results of the bands with significant differences revealed that the pathway with the highest correlation was the mRNA metabolism pathway, which contains the NSUN2 protein (Fig. 5a). NSUN2 is a key enzyme in mRNA m5C modification38,39. This epigenetic modification of mRNA is closely linked to tumor development and progression40. Additionally, previous studies have shown that piRNAs are significantly related to epigenetics41, prompting us to select NSUN2 as a target for in-depth study.

The binding of piR-28846 to the NSUN2 protein was reconfirmed through RNA immunoprecipitation experiments (Fig. 5b). Western blot analyses demonstrated that the expression level of NSUN2 was decreased upon overexpression of piR-28846 (Fig. 3e). Additionally, CCK-8 assay and apoptosis assay showed that down-regulation of NSUN2 inhibited cell proliferation (Fig. 5c) and promoted cell apoptosis (Fig. 5d), consistent with the cell phenotype observed with piR-28846 overexpression.

a The mass spectrum results were performed by KEGG enrichment analysis. b The binding of piR-28846 to NSUN2 protein. c Down-regulating the expression of NSUN2 in ovarian cancer cells can inhibit cell proliferation. d Down-regulating the expression of NSUN2 in ovarian cancer cells can promote apoptosis. e Dot blot assay showed that the expression level of m5C decreased after overexpression of piR-28846 in ovarian cancer cells. f Immunofluorescence staining of m5C in CAOV3. g The binding of KPNA2 mRNA to NSUN2 protein. h The expression levels of KPNA2 mRNA after knocking down NSUN2 or overexpressing NSUN2. i The expression levels of associated proteins after knocking down or overexpressing NSUN2. j When NSUN2 was overexpressed in cells that overexpressed piR-28846, KPNA2 mRNA expression was reversed. k When NSUN2 was overexpressed in cells that overexpressed piR-28846, KPNA2 protein expression was reversed.

NSUN2 is a key enzyme involved in m5C modification of mRNA. when the expression of piR-28846 was overexpressed, the expression level of NSUN2 was decreased, which was accompanied by a reduction in m5C modification levels, as shown by m5C dot blot (Fig. 5e) and immunofluorescence assays (Fig. 5f). To determine whether NSUN2 can modify the target mRNA of piR- 28846, we conducted an RIP assay and found that NSUN2 protein binds to KPNA2 mRNA (Fig. 5g). Upon knocking down NSUN2 expression (Supplementary Fig. 1f), we observed decreased levels of both KPNA2 mRNA and protein (Fig. 5h, i). Conversely, overexpression of NSUN2 led to increased levels of KPNA2 mRNA and protein (Fig. 5h, i). Furthermore, when NSUN2 was overexpressed in an ovarian cancer cell line that also overexpressed piR-28846, we found that KPNA2 mRNA (Fig. 5j) and protein levels (Fig. 5k) were higher than those in the control group, effectively reversing the expression changes induced by piR-28846 overexpression.

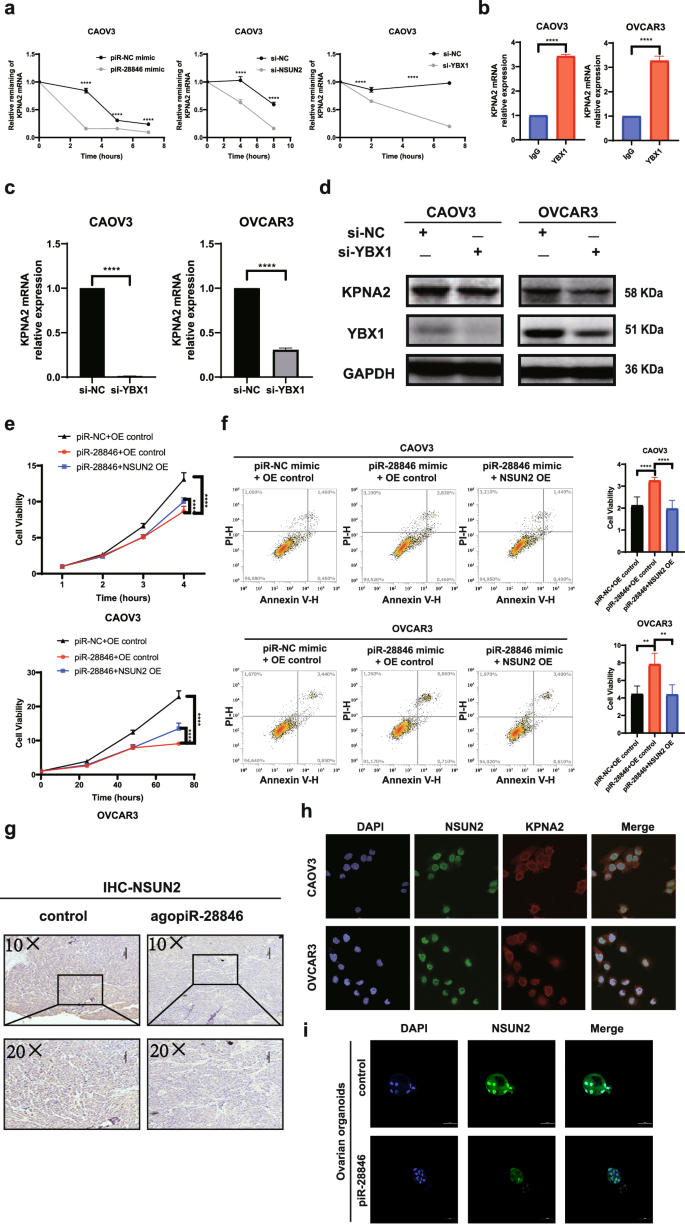

To further investigate the effect of NSUN2 on KPNA2 levels, mRNA stability experiments revealed that knocking down NSUN2 decreased the stability of KPNA2 mRNA (Fig. 6a). In the context of m5C mRNA modification, YBX1 serves as an m5C reader that plays a crucial role in maintaining the stability of target mRNA, with its binding affinity dependent on the methyltransferase activity of NSUN224. RIP experiments demonstrated that both NSUN2 and YBX1 proteins bind to KPNA2 mRNA (Figs. 5g, 6b). When YBX1 was knocked down, we observed a decrease in the stability of KPNA2 mRNA (Fig. 6a), along with reductions in both the mRNA and protein levels of KPNA2 (Fig. 6c, d and Supplementary Fig. 1g). Additionally, overexpression of piR-28846 led to decreased stability of KPNA2 mRNA in conformity with the effects observed upon knocking down NSUN2 and YBX1 (Fig. 6a). The above experiments indicate that KPNA2 mRNA is a target mRNA of NSUN2 and YBX1, with NSUN2 mediating YBX1 recognition and maintaining mRNA stability. When NSUN2 was overexpressed in the ovarian cancer cell line that also overexpressed piR- 28846, the effects of piR-28846 on cell proliferation and apoptosis were reversed (Fig. 6e, f). These results indicate that piR-28846 binds to NSUN2 and down-regulates its protein level and the modification level of m5C, and regulates the stability of target KPNA2 mRNA through YBX1. This interaction ultimately leads to reduced stability of KPNA2 mRNA and downregulation of its protein level, exerting an inhibitory effect on ovarian cancer cells.

a Stability of KPNA2 mRNA when the expression of piR-28846, NSUN2, and YBX1 is changed. b The binding of KPNA2 mRNA to YBX1 protein. c KPNA2 mRNA expression levels after knocking down YBX1. d The expression levels of associated proteins after knocking down YBX1. e Overexpression of NSUN2 reversed the effect of piR-28846 on ovarian cell proliferation. f Overexpression of NSUN2 reversed the effect of piR-28846 on ovarian cell apoptosis. g Compared with the control group, the expression of NSUN2 in xenografts treated with agopiR-28846 was significantly reduced. h Immunofluorescence assay showed the localization of NSUN2 and KPNA2 proteins in ovarian cancer cells. i Immunofluorescence showed the changes of NSUN2 expression in ovarian cancer organoids after ago piR-28846 treatment.

KPNA2 and NSUN2 are mutually regulated

The experiments indicated that overexpression of piR-28846 led to a decrease in both the expression level of NSUN2 and the modification level of m5C, thereby affecting its regulation of target mRNA. Additionally, immunohistochemistry revealed that NSUN2 expression was significantly reduced in ovarian cancer xenograft models after treatment with agopiR-28846 (Fig. 6g).

As an m5C methyltransferase, NSUN2 has been shown in previous studies to be mainly localized in the nucleus or cytoplasm, playing a role in various biological functions, depending on its subcellular localization42,43. During the cell cycle, its distribution shifts from the nucleus to the mitotic spindle44. In osteosarcoma cells, NSUN2 is predominantly found in the nucleus, with some NSUN2 proteins co-localizing with mitochondria43. A recent study in gastric cancer revealed that SUMO2/3 can regulate the protein stability and subcellular localization of NSUN245. To further investigate the localization of NSUN2 in ovarian cancer cells, we conducted immunofluorescence experiments in CAOV3 and OVACR3. Our findings showed that NSUN2 was expressed in both the nucleus and cytoplasm, with a highly expression level observed in the nucleus (Fig. 6h). After treatment with agopiR-28846, the expression level of NSUN2 in the nucleus of ovarian cancer organoids was significantly reduced (Fig. 6i). Additionally, Dot-blot experiments indicated that overexpression of piR- 28846 in ovarian cancer cells led to a decrease in the overall m5C modification level. These results suggest that piR-28846 can alter both the expression level and subcellular localization of NSUN2, hereby impacting its modification activity.

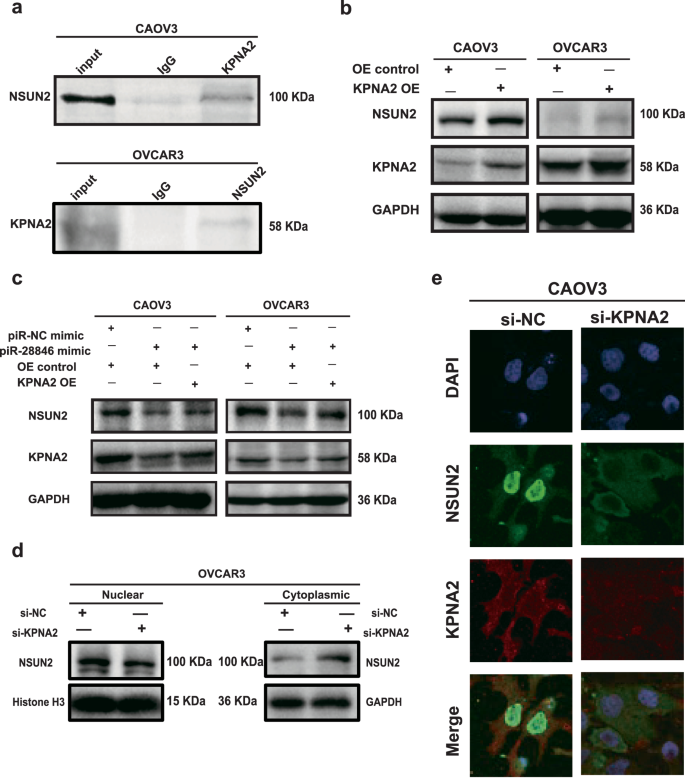

KPNA2 is a nuclear import protein that regulates the nuclear transport of proteins and has been shown to interact with various cancer-related proteins46,47,48,49. CO-IP experiment demonstrated that KPNA2 protein binds to the NSUN2 protein (Fig. 7a). We observed that NSUN2 protein levels decreased when KPNA2 was knocked down (Fig. 4d), while overexpression of KPNA2 led to an increase in NSUN2 protein levels (Fig. 7b). Additionally, KPNA2 was overexpressed in ovarian cancer cell lines that also overexpressed piR-28846 (Fig. 7c), resulting in a reversal of NSUN2 protein expression levels. Furthermore, immunofluorescence and nuclear-cytoplasmic protein isolation experiments showed that knocking down KPNA2 affected the distribution of NSUN2 within the cells (Fig. 7d,e). In summary, KPNA2 protein binds to NSUN2 protein, and changes in KPNA2 levels not only influence NSUN2 protein levels but also its localization within the cell. Additionally, alterations in NSUN2 expression and modification levels can impact KPNA2 expression. These results suggest a feedback regulatory relationship between KPNA2 and NSUN2 (Fig. 8).

a The binding of KPNA2 protein to NSUN2 protein. b Overexpressing KPNA2 affects the expression of associated proteins. c The levels of associated protein expression following KPNA2 overexpression in cells with stable overexpression of piR-28846. d Nucleus and cytoplasm expression levels of NSUN2 proteins after KPNA2 knockdown. e Immunofluorescence assay showed that the localization of NSUN2 in cells changed after KPNA2 knockdown.

piR-28846 binds to NSUN2 and downregulates its expression, thereby affecting the stability of target KPNA2 mRNA and reducing KPNA2 protein levels. Changes in KPNA2 levels will subsequently alter the cellular localization and expression of NSUN2, creating a feedback regulatory loop. piR-28846 also plays a role of post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) in cytoplasm. Through the NSUN2-YBX1-KPNA2 axis and the PTGS, the expression level of KPNA2 is further decreased, contributing to the anti-cancer effect.

Discussion

Recently, an increasing number of approved nucleic acid therapies have demonstrated their potential to target the genetic blueprint in vivo for disease treatment11. While nucleic acid drugs show great promise in development, both intracellular and extracellular barriers limit their widespread clinical use. Unmodified nucleic acids are unstable in the bloodstream and can be degraded by serum nucleases shortly after entering circulation21,22. Currently, the most commonly used nucleic acid drugs are ASOs and siRNAs. A prevalent strategy for enhancing the stability of siRNA drugs involves adding 2’-O-methyl (2’-O- Me) or 2’-fluoro (2’-F) modifications to their backbone. In contrast, piRNAs inherently possess the 2’-O-Me modification, which is one of their advantages. Moreover, ASOs and siRNAs are designed as small RNAs that do not naturally occur in human cells, which can lead to mismatches and unwanted silencing alongside their intended target gene silencing. In contrast, the piRNA we identified is a naturally occurring small RNA suppressor in human cells, that can be amplified to inhibit cancer through overexpression in vivo, representing another significant advantage.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in which we identified that piR-28846 functions as a tumor suppressor RNA in ovarian cancer. We found that its chemically modified form, agopiR-28846 exhibits an effective therapeutic effect on xenograft tumors and ovarian cancer organoid models. Additionally, we elucidated, the molecular mechanism by which piR-28846 exerts its effects in ovarian cancer.

Many piRNAs have been reported to regulate post-transcriptional networks to inhibit target functions through piRNA-RNA interactions50. We found that piR- 28846 and KPNA2 mRNA exhibit strict base pairing at the 5’ end of the piRNA, specifically within the 2–11 nt. Dual luciferase reporter assays confirmed the interaction between piR-28846 and KPNA2 mRNA. The KPNA2 protein, also known as importin α-1, is a member of the nuclear import protein family that can influence in the nuclear levels of certain proteins46,47. In recent years, elevated levels of KPNA2 have been observed in various of malignancies, including lung, ovarian, breast cancer32,33,34. Previous studies have shown that KPNA2 promotes the proliferation and tumorigenicity of ovarian cancer cells by upregulating c-Myc34. Increased expression of KPNA2 is associated with poor prognosis in ovarian cancer patients35,36, and it has also been linked to enhanced migration and invasion of epithelial ovarian cancer cells51. These findings indicate that KPNA2 is closely related to the occurrence and progression of ovarian cancer. Changes in c-Myc expression are associated with cell proliferation and differentiation, playing a crucial role in regulating cell growth, differentiation, or malignant transformation52. Therefore, KPNA2 may contribute to carcinogenesis in ovarian cancer by regulating c-Myc expression. Our results show that overexpression of piR-28846 in ovarian cancer cells effectively inhibited cell proliferation compared to the control group while promoting apoptosis. When KPNA2 was knocked down in ovarian cancer cells, the levels of proliferation and apoptosis mirrored those observed with piR- 28846 overexpression, accompanied by a decrease in c-Myc expression, consistent with previous findings. These results suggest that piR-28846 can inhibit the malignant phenotype of ovarian cancer cells by downregulating KPNA2 expression.

piRNAs may also bind to proteins to exert their functions. To investigate this, we conducted mass spectrometry analysis on piR-28846 RNA-pulldown experiment, and identified several proteins that may bind to piR-28846 within the mRNA metabolism pathway, including NSUN2, a major methyltransferase responsible for m5C modification of mRNA. The binding of piR-28846 to NSUN2 was further confirmed by RIP experiment. Through Q-PCR and western blot experiments. We found that knocking down NSUN2, resulted in decreased expression of both KPNA2 mRNA and protein conversely, overexpression of NSUN2 increased their levels. In the context of m5C modification, YBX1 acts as a reader the stability of target mRNA, with its binding affinity on the methyltransferase activity of NSUN253. Through RIP experiments, demonstrated that KPNA2 mRNA binds to both NSUN2 and YBX1. Further mRNA stability experiments revealed that knocking down NSUN2 and YBX1, resulted in decreased stability of KPNA2 mRNA, similar to the effects observed when piR-28846 was overexpressed. Moreover, overexpression of piR-28846 in ovarian cancer cells led to a decrease in NSUN2 levels. These findings indicate that piR-28846 can mediate the regulation of YBX1 on KPNA2 mRNA stability by interacting with NSUN2. While NSUN2 primarily exerts its modification role in the nucleus, KPNA2 is a nuclear import protein, that regulates the nuclear transport of various proteins45,46,47. COIP experiment showed that NSUN2 binds to KPNA2. When KPNA2 was knocked down, we observed changes in the expression levels of NSUN2 both inside and outside the nucleus, suggesting that KPNA2 may play a role in regulating NSUN2 protein localization. Additionally, knocking down KPNA2 resulted in decreased levels of NSUN2 protein. Therefore, KPNA2 may influence NSUN2 protein expression by regulating its nuclear transport, thus establishing a feedback regulation regulatory mechanism.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that piR-28846 inhibits the expression of target KPNA2 mRNA through PTGS. In addition, piR-28846 binds to NSUN2 and downregulates its expression, thereby affecting the stability of target KPNA2 mRNA and reducing KPNA2 protein levels. Changes in KPNA2 levels will subsequently alter the cellular localization and expression of NSUN2, creating a feedback regulatory loop. Through the NSUN2-YBX1-KPNA2 axis, the expression level of KPNA2 is further decreased, contributing to the anti-cancer effect. Additionally, agopiR- 28846 may offer a novel approach for treating ovarian cancer as a potential small nucleic acid drug.

Methods

Ovarian cancer and normal tissue samples

Overall, 29 normal ovarian tissue and 108 ovarian cancer tissue specimens were collected from patients who had gynecological surgery at the Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (Guangzhou, China). The specimens were frozen in liquid nitrogen as soon as they were excised and stored at −80 °C. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (Number 2020-066) and adhered to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 amendment).

Cell culture and transfection

We conducted the expression analysis of piR-28846 for four common cell lines in ovarian cancer (A2780, CAOV3, OVCAR3, and SKOV3, Supplementary Fig. 1c). Through repeated experiments, we found that the expression of piR- 28846 was relatively lower in ovarian cancer cell lines CAOV3, OVCAR3. Therefore, we chose these two cell lines to overexpress piR-28846 and analyzed its mechanism. The human ovarian cancer cell lines (CAOV3, OVCAR3) and tool cell (293T) were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) or Cell Bank, Chinese Academy of Sciences (China). CAOV3 and OVCAR3 cells in RPMI Medium 1640 basic (gibco), 293T cells were cultured in DMEM basic (gibco). Both culture mediums were supplemented with penicillin-streptomycin liquid (solarbio) and 10% fetal bovine serum (ExCell Bio).

Cell proliferation assay

Cells were inoculated in the 96-well plate sat a density of 2000 cells per well 100 μL, and transiently transfected with the corresponding constructs the next day. At 0 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h, 10 μL of CCK-8 reagent (Yeasen) was added to the cells. Two hours later, the absorbance of each hole was measured. The experiment was repeated three times.

Apoptosis assay

The cells were inoculated in the 6-well plate at a density of 3.5 × 105 cells per well/2 mL, and transient transfection was performed with the corresponding constructs the next day. After 48 h, the cells were collected and washed with PBS. After digestion, the cells were centrifuged with PBS and cleaned. The supernatant was removed, and then the cell precipitate was resuspended by 100 μL binding buffer containing 5 μL of Annexin V-FlTC and 5 μL of Pl (BD Pharmingen). The tubes were incubated in the dark for 15 min before the addition of 400 µL of binding buffer. A quantitative analysis of apoptosis was performed using flow cytometry. The experiment was repeated three times.

Colony formation assay

The cells were inoculated in a 6-well plate at a density of 1000 cells/2 mL per well, and once the cells adhered, transient transfection was performed with the corresponding construct. After 8 to 10 days, the colonies were washed with PBS, fixed with formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature, washed with PBS, and stained with 0.1% crystal violet (Solarbio). After rinsing the samples with running water and carefully removing any excess dye, the samples were allowed to dry. Following the drying process, the formation of colonies was observed. The experiment was repeated three times.

Western blotting

Total proteins were extracted from cultured cells or tissues with RIPA lysate (BestBio). Quantitation was performed using the BCA Kit (Beyotime). Protein samples were diluted to 2 μg/µL with appropriate loading buffer and PBS and denatured at 95 °C. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and were electrotransferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Amersham, Munich, Germany). After 2 h of sealed at RT with TBST containing 3% bovine serum albumin, antibodies were incubated at 4 °C overnight. These were washed with 1% TBST buffer. The membrane was then incubated with rabbit secondary antibody for 1.5 h and washed with 1% TBST buffer. The bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence system (NCM Biotech). The experiment was repeated for three times.

RNA antisense purification (RAP)

We designed a piR-28846 RNA probe (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., 482 Shanghai, China). For a group of RAP experiments, 4 × 107 cells were collected and washed by PBS. After centrifuging at room temperature at 1000 rpm, the supernatant was then discarded, and the cells were collected. 40 mL 1 × PBS (including 1.08 mL 37% methanol) was added into the cells, mixed vertically at room temperature, and then related reagents and piR-28846 RNA probe were added into the RNA antisense purification kit (BersinBio) according to the instructions. Finally, Trizol reagent was used to extract the final RNA, and the RNA bound to it was detected by q-PCR. The experiment was repeated three times.

Subcutaneous tumorigenesis experiment in nude mice

CAOV3 cells (1 × 107) were suspended in PBS and injected subcutaneously into 4-week-old female BALB/c nude mice to establish an in vivo ovarian cancer model. After a week, nude mice having tumors in the right shoulder and back were selected at random and separated into two groups. The experimental group was injected with PBS having agopiR-28846. The control group was injected with PBS. We used vernier calipers to measure the longest and shortest tumor sites every 3 days. V = 1/2*a*b*b (a is the long axis; b is the short axis), when the long axis of largest tumor reached 15 mm. Mice were euthanized (exposed to a visible euthanasia box filled with carbon dioxide gas), confirming animal immobility, lack of respiration, and dilated pupils. CO2 was then turned off, and animals were monitored for 2–3 min to confirm death for dissection, and tumor tissues from each group of mice were collected for subsequent experiments. All mice were sourced from the Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center and placed in a specific pathogen-free environment. All experiments involving live vertebrates were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and approved by the Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center, and conducted in strict accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health, ensuring all efforts were made to minimize animal suffering (Approval Number: B202208-8).

Organoid culture and experiment

Fresh tissue samples of ovarian cancer were collected and immediately placed into tissue protective fluid. The ovarian cancer specimens were cut into 1–2 mm fragments with surgical scissors on PBS containing 1% cyanostreptomycin. After washing with PBS containing 1% streptomycin, the super serum was discarded, and organoid digestive fluid was added according to the tissue volume and digested on a shaking table at 37 °C for 1–2 h. After complete digestion, the supernatant was removed with a 100 pm cell filter and centrifuged. The precipitate was resuspended by 5 mL DMEM/f12++. After centrifugation, the supernatant was removed. According to the precipitation amount, the corresponding volume of ovarian cancer organoid medium and matrix gel suspension was added in a ratio of 1:1. The mixture (50 pL) was added to the 24-well plate, incubated upside down at 37 °C for 5 min, and cured for 20 min. After curing, 500 pL ovarian cancer organoid medium was added and cultured in an incubator. Organoid growth was observed every day, and the medium was changed every 2–3 days. Approximately the same number of ovarian cancer organoids were placed in 96-well plates. On the 2nd day, ovarian cancer culture medium containing agopiR-28846 (100 pL/well) without transfected reagents was added as the experimental group, and ovarian cancer culture medium containing the same amount of PBS was added as the control group. The medium containing PBS and agopiR-28846 was replaced once a day, and organoid growth was observed. In the 3D organoid models, five ovarian cancer samples were obtained from the Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, and seven ovarian cancer samples were obtained from the Liaoning Cancer Hospital. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (No. 2020-066) and the Liaoning Cancer Hospital (Number 20220320G), following the guiding principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (amended in 2013).

Human tissues specimens

Clinical samples were collected at the Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University and the Liaoning Cancer Hospital with written informed consent from all human participants, as approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Institute.

RNA stability assay

CAOV3 cells transfected with piR-28846 mimic, si-NSUN2, and si-YBX1 were treated with 4 μg/mL Actinomycin D (Selleck). After adding Actinomycin D, cells were collected at different periods to add the RNAiso Plus reagent. In the last group, after adding the RNAiso Plus reagent, total RNA was extracted from cells of different periods at the same time for RT-qPCR analysis.

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay

Cells were washed with PBS, scraped, and centrifuged. Lysis was performed overnight at 4 °C using Celllysis buffer for Western and IP (Beyotime). On the 2nd day, the cell lysates were centrifuged. The supernatant (20 pL) was taken as the input group, and equally divided with 4 pg IgG (R, Proteintech) or 4 pg anti-NSUN2 antibody (R, Proteintech) and anti-YBX1 antibody (R, Proteintech) and incubated on a vertical shaker at 4 °C for 16 h. Each sample was mixed with magnetic bead suspension (50 pL) and incubated continuously at 4 °C for 4 h. The EP tube was placed on a magnetic scaffold, the super serum was carefully aspirated, and the magnetic bead was washed thrice with TBST containing RNase inhibitor (1:1000, Beyotime). RNA bound to magnetic beads was extracted with RNAiso Plus reagent (1 mL) and amplified by RT-qPCR as described above. The experiment was repeated three times.

Protein-protein immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) experiment

COIP assay requires cells >2 × 107. We usually use a petri dish with a diameter of 10 cm for culture. When the cells grow to 90%, 3–5 plates of cells are usually collected for experiment. It was added to IP lysate according to the amount of protein for dissolution overnight at 4 °C. The cell lysate was centrifuged the next day. The supernatant (20 pl) was taken as the input group, and equally divided into 4 pg IgG (R, Proteintech) or 4 pg anti-NSUN2 antibody (R, Proteintech) and incubated on a vertical shaker at 4 °C for 16 h. Subsequently, each sample was mixed with magnetic bead suspension (50 µL) and incubated continuously at 4 °C for 4 h. The EP tube was placed on a magnetic scaffold to carefully aspirate the supernatant, and the magnetic bead was washed with TBST containing protease inhibitor. After aspirating the supernatant, each sample was denatured in 60 µL 2× loading buffer, and western blotting was performed. The luminescence of the membrane coated with anti-KPNA2 antibody (Proteintech) was observed and recorded. These were washed with 1% PBST buffer. The membrane was then incubated with mouse secondary antibody (1:8,000, Proteintech) for 1 h. The experiment was repeated three times.

m5C dot blot

Sufficient RNA was collected. mRNA was isolated from total RNA using the Dynabeads® mRNA Purification Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The mRNA was heated at 95 °C for 3 min. Then, 2 µL of mRNA was dropped directly onto the Hybond-N+ membrane optimized for nucleic acid transfer. The membrane was UV-crosslinked twice. After blocking in PBST containing 5% Blotting Grade (Beyotime) for 1 h, the anti-m5C antibodies (1:2500, Proteintech) were incubated at 4 °C overnight. The membrane was then washed with 0.02% PBST buffer. The membrane was then incubated with mouse secondary antibody (1:8,000, Proteintech) for 1.5 h. These were washed with 0.02% PBST buffer. The membrane was visualized. Then, the membrane was stained with methylene blue for 30 min, and washed with ribonuclease-free water for 10 min. The experiment was repeated three times.

Luciferase reporter assay

To confirm KPNA2 as a piR-28846 target, a set of dual luciferase reporter plasmid was constructed in which wild-type plasmid (KPNA2-WT) covered a potential piR-28846 binding fragment in KPNA2. The plasmid with a mutation in the potential binding fragment of KPNA2 and piR-28846 was a mutant (KPNA2-MUT) as a negative control. The 293T cells (1 × 105 cells/well) were inoculated into a 24-well plate, and the WT or MUT structures were co-transfected into the piR-28846 mimic or piR-NC mimic with Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen). Cells were harvested at 48 h and luciferase activity was detected using the Luciferase® Reporting Kit (Promega). The experiment was repeated three times.

RNA pull-down assay and MS analysis

A 3’-terminal biotinized piR-28846 RNA probe (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was designed. Cells were lysed and added to the piR-28846 RNA probe according to the RNA pull-down Kit (Bersinbio) to extract the protein. The final sample was boiled with SDS-PAGE loading buffer and loaded onto SDS-PAGE gel. Coomassie Blue’s staining revealed protein bands, and the pull-down material gel channel of piR-28846 was excised and sent to a commercial facility (Guangzhou Promegene Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for MS analysis.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) experiment

Mouse tumor xenografts were excised, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned. The sections were dewaxed with xylene and hydrated with alcohol. After antigen recovery, sections were treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide to block endogenous peroxidase activity, followed by incubation with 5% bovine serum albumin to block non-specific binding. The section staining was performed with anti-KPNA2 antibodies (1:100, Proteintech) and anti-NSUN2 antibodies (1:100, Proteintech), washed thrice with TBST and an enzyme-labeled anti-rabbit antibody probe for 1 h. After washing TBST thrice, the pigment 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) was used for development, and hematoxylin was used for reverse staining. The stained sections were dehydrated with an ethanol gradient, and the staining was observed with an upright microscope.

Immunofluorescence (IF) assay

The cells were seeded into a 6-well plate containing a slide with a density of 1 × 105 cells/2 mL per well, and after cell adhesion, transient transfection was performed with the corresponding construct. The organoids are inoculated in 24-well plates containing slides. After 48 h, the colonies were washed with PBS, fixed with formaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature, washed with PBS, and perforated with Triton X-100 (Beyotime) for 20 min. After 2 h of sealed at RT with TBST containing 5% bovine serum albumin, primary antibodies were incubated at 4 °C overnight. These were washed with PBST buffer. The membrane was then incubated with 488 or 594 antibodies (1:500, Proteintech) for 1 h in the dark and washed with PBST buffer. Finally, 10 µL of DAPI was dropped onto the slide and it was covered with a cover slide in the dark. The fluorescence results were observed under the confocal microscope. The experiment was repeated three times.

Quantitative reverse transcription–PCR (qRT-PCR)

To the RNA extracted with RNAiso Plus (1 mL, Takara, Shiga, Japan), 200 μL chloroform was added, thoroughly mixed, and left for 3 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and the RNA was precipitated with an equal amount of isopropyl alcohol. It was allowed to stay overnight at −20 °C and centrifuged, retaining the precipitation and cleaning with 75% ethanol. The water filter paper was used to dry, and the residue was dissolved with diethyl sodium pyrocarbonate water. Spectrophotometry was used to measure the total RNA concentration (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The copied DNA (Yeasen) was reverse-transcribed by a reverse transcription kit. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed using the qPCR Kit (Yeasen). The piR-28846 was tested using the miRNA qRT-PCR Starter Kit (RIOBIO) for reverse transcription and quantitative real-time PCR. Finally, the cycle threshold (Ct) values of target genes and control genes were compared according to the 2 − ΔCt method to calculate the relative expression of genes. The experiment was repeated three times.

Screening of piR-28846

We performed Pandora-Seq on four groups of ovarian cancer tissues and normal ovarian tissues, and comparing the sequencing data with the piRNA bioinformatics database (Pandora-Seq result), we can obtain the expression information of the existing piRNAs in the database, including the structure, length, and expression level. We performed a differential analysis of piRNA expression and screened the P-values of the differential analysis results from low to high. Among the several piRNAs with low P-value values, we filtered the first six (piR-32199, piR-32198, piR-32176, piR-24360, piR-28845, piR-28846) that were significantly highly expressed in normal ovarian tissues as well as those that were significantly low expressed in ovarian cancer tissues. In the pre-experiment of the functional experiments on these piRNAs, we found that piR-28846 had a significant inhibitory effect and the most significant function in ovarian cancer cells, and therefore chose piR-28846 for further study.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism was used for graph and data analysis. According to the data, statistical analysis methods of t-tests or Two-way ANOVA were selected for analysis. Relevant data were expressed as mean ± standard mean error, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Responses