Poleward displacement of the Southern Hemisphere Westerlies in response to Early Holocene warming

Introduction

The recent intensification and southward migration of the Southern Hemisphere Westerlies (SHW) since the 1950s has resulted in important changes to the southern high latitudes1,2. These include, among others, increased drought and wildfires along the continental margins of the South Atlantic and South Pacific (e.g. South Africa, Australia, Chile and Argentina3,4,5,6; increased ice shelf instability resulting from the advection of warmer waters onto the Antarctic continental shelf7,8,9,10; and changes to Southern Ocean circulation and its ability to sequester heat and atmospheric CO211,12,13). Each of these has potentially large future impacts on both ecosystems and humans globally.

Despite the well-documented history of the SHW over the satellite period, little is known about their natural behaviour over longer timescales. This is especially critical since our understanding of the SHW is based only on the last several decades, coincident with the era of stratospheric ozone depletion, which has amplified their recent intensification14. As a result, we have little understanding of the natural range of variability of the SHW during relatively warmer or colder periods, or how anticipated future warming in the absence of ozone depletion will affect the SHW and their impacts on climates, ecosystems, ocean circulation and Antarctic Ice Sheet stability.

Palaeoclimate archives from within the present-day core belt of the SHW (45-60°S) offer an opportunity to understand the natural range of variability of the SHW over century-millennial timescales. This is especially true for records from lakes and peatlands, which are widely dispersed in the ice-free areas of the high latitude Southern Hemisphere and can provide continuous records of SHW following deglaciation after the last glacial period.

Because South America extends into the core belt of the SHW, and lake, bog, and fjord sediment records from Patagonia are plentiful, much of our collective understanding of the SHW hinges on this critical region. In southern South America, changes to the SHW and their control on moisture balance have shaped the evolution of the landscape, including the spread of forests, distribution of wetlands and frequency of wildfires15,16,17,18,19. However, despite the high density of postglacial paleoclimate records in this region, questions remain about how changes to the moisture balance, vegetation dynamics, and landscape change in different locales (particularly west and east of the Andes) reflect broader scale changes in the strength and position of the SHW over the Holocene. The conflicting inferences of SHW behaviour make efforts at regional syntheses over the Holocene complicated16,20,21,22.

Two main theories of SHW behaviour in South America drive the debate: The first is that the SHW have moved little over the Late Glacial-Holocene but have changed markedly in intensity. Lines of evidence for this are based along the interior and eastern flank of the Andes in Patagonia ( ~ 52°S) where drying recorded in bog and fen pollen suggest that the SHW were completely absent from these locations during the early Holocene: so-called “missing winds”22. Additionally, other sites at similar latitudinal bands across the Pacific show a reduction in SHW between 11-7.5 calibrated thousands of years before present (cal ka BP), reinforcing the idea that the winds were greatly diminished across mid-latitude sites in the early Holocene21,22.

The second, opposing theory is that the changes to the SHW recorded at different sites in Patagonia reflect the contraction/extension of the wind belt in response to warmer (poleward) and colder (equatorward) climate that mirror modern-day seasonal trends20. Ocean, fjord, lake, and bog records from mostly west of the South American Cordillera from 30-54°S document antiphasing of strong and weak winds to the north and in the core of the current wind belt, depending on the location of the winds throughout the Holocene, which mirrors the changes in location and intensity of the SHW through the austral winter and summer seasons in the present day.

Over glacial and interglacial timescales, paleoceanographic records describe different SHW dynamics, with winds shifting significantly to the north and south of their current range in response to global temperature and ocean dynamics23. Southern Ocean records suggest a ~ 5° poleward shift in the SHW with the last deglaciation, accompanied by a migration of the sea surface temperature front24 and an increase in deglacial upwelling25. At the northern margins of the modern SHW core belt in South America, fluctuations in lake level and vegetation over the last glacial period can also be explained by larger-than-present meridional shifts in the SHW26,27, but not all agree to the sign of the shift (e.g.28,29).

Here, we present an 11 kyr diatom-based sea salt aerosol and multiproxy environmental record from a small cirque lake (“Isla Hornos Lake”; IHL) on Cape Horn (56°S), which traces the evolution of the SHW in the core belt over millennial timescales and helps to refine their behaviour over the Holocene. Uniquely, the sea salt aerosol record is directly linked to wind strength, averaging the undisturbed and large-scale open ocean westerlies at the entrance to the Drake Passage. With this record, we help resolve the nature of changes in the SHW during the Holocene in this critical region and what they mean for the behaviour of the SHW under future warming scenarios.

Modern climate setting

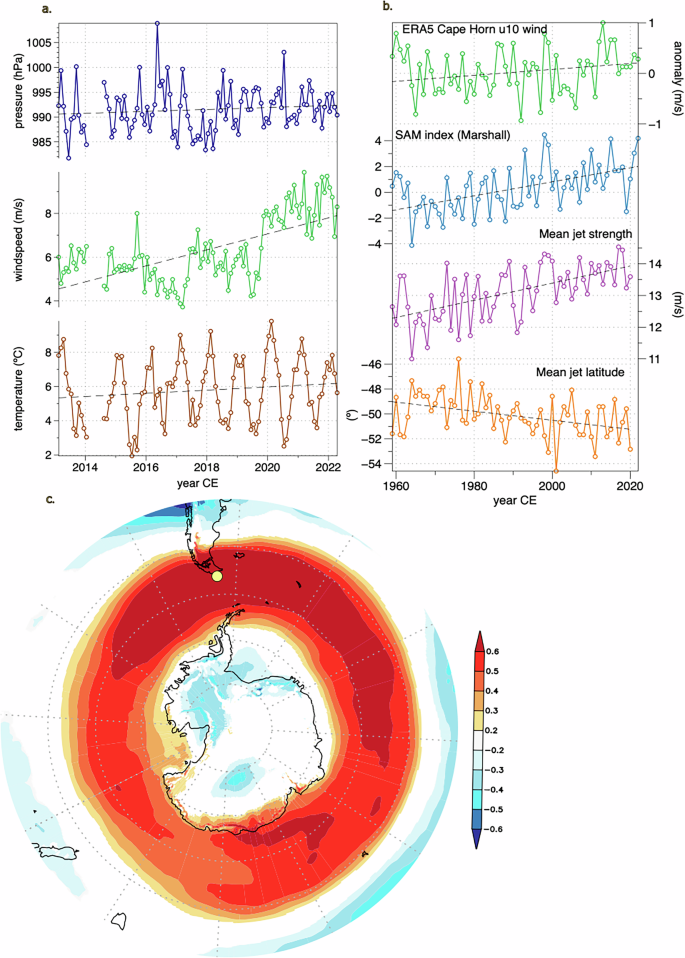

Our study lake (“IHL”, 55°58’ S, 67°17’W, 156 m asl; Fig. 1) is situated on a promontory at Cape Horn, on the southern tip of Hornos Island (Isla Hornos) which is the southernmost island in the Tierra del Fuego Archipelago and the southernmost island in South America. The lake (1.28 ha) is small and relatively deep (10.7 m), which prevents wind-mixing of the sediments. The glacial history of the archipelago is poorly constrained30, but far-field relative sea level histories show that the lake at its cliff-top location sits well above past shoreline incursions (see Supplementary figure 1.4). As with other sites abutting the Southern Ocean, Hornos Island has a subpolar oceanic climate which is dominated by the effects of the SHW, including high precipitation ( ~ 1565 mm yr −1), relatively stable cool mean air temperature (MAT) that reflect adjacent ocean sea surface temperature (SST) (MAT = 5°C, <40 days below freezing per year), and high winds predominantly from the west (average wind speeds are >30 km h−1, gusting over >200 km h−1 during storms)31,32,33 (See Supplementary Note 1). These winds are the primary sea salt aerosol delivery mechanism responsible for changes in salinity in the study lake. Recent instrumental records (2013-2022) from the Cape Horn lighthouse (3 km to the east of our site) document a doubling of wind speed as well as a steady increase in pressure and temperature over the last decade ( ~ 1°C)(Fig. 2a). These changes are consistent with climate trends across the subantarctic, which correlate with an increasingly positive Southern Annular Mode (SAM) index34 and the steady southward displacement of the Southern Hemisphere (SH) mean jet position since the 1960s35 (Fig. 2b). Modern surface zonal winds at Cape Horn are representative of the SHW across a broad swath of the Southern Ocean between roughly 50–65°S with strongest correlations between the Eastern Pacific and South Atlantic sectors (see correlations with 850 hPa winds Fig. 2c). Reanalysis products (ERA5) perform a reasonably good job of estimating climate variability over the observational period31, but underestimate the recent (last 5 years) increase in wind speed at the site.

Location maps showing (a) Hornos Island relative to the Southern Ocean and the SHW. Annual sea surface-level (10 m) mean wind speeds are based on NOAA blended high resolution (0.25 degree grid) vector data downloaded from (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/data-access/marineocean-data/blended-global/blended-sea-winds). DP marks the location of the Drake Passage. b The location of “Isla Hornos Lake” (IHL) and the lighthouse. The satellite photo is from Sentinel 08/08/2022. Note the wind and wave action (white fringe of surf) along the western (windward) margin of the island. This is the primary method of salt delivery to our site.

a Monthly averaged observations from Cape Horn lighthouse meteorological station (2013-2022) show an increase in pressure, wind speed, and temperature since 2013 (data courtesy of the Chilean Armada, 2023). b Reanalysis data (ERA5; 1960-2022) show an increase in Hornos Is. zonal (u10) wind speed consistent with an increase in the Southern Annular Mode (SAM) index34, and an increase in the mean jet strength and increased poleward movement of the mean jet latitude since the 1960s35. Note that the current mean jet latitude (54°S) sits equatorward of our site (56°S). c Spatial correlation between summer (DJF) zonal surface winds (u10) at Hornos Is. with zonal 850 HPa (u850) winds within the broader mid- to high-latitude Southern Hemisphere (ERA5; 1950–2024).

Results and discussion

Paleoenvironmental changes at Cape Horn

The sediments from IHL are formed of faintly laminated, organic-rich gytjja (10–40% total carbon) and span the last 11 cal ka BP, with no evidence of glacial activity within the cirque over the sedimentation period. (see Methods and Supplementary Note 2 for more information on chronological controls and sedimentology).

Wind-borne sea-salt aerosol deposition is tracked by fossil lacustrine (lake) diatom assemblages in the sediments, which respond to changes in lake-water conductivity over time36,37 (Fig. 3, see supplementary Note 3). Despite the lake’s proximity to the coast, true marine diatom taxa are rare to absent, and far-field relative sea level history suggests that the lake would have been buffered from the effects of major shoreline changes over the last 11 cal ka BP38,39. In the sediments, anti-phasing of organic and lithogenic-materials track quiescent periods and intervals of higher precipitation and catchment erosion via surface runoff from higher SHW, respectively. Together, the palaeoenvironmental proxies in the core document changes over the last 11 cal ka BP which we interpret to directly reflect the strength of the SHW at this site. Three main climate periods can be identified.

Diatom relative species abundance and significant biostratigraphic zones from IHL. Diatom taxa are colour-coded according to habitat: green taxa prefer benthic, vegetation-rich substrates; orange planktonic taxa are associated with high salinities in Patagonian lakes, and blue are benthic and planktonic taxa associated with a range of salinities in the subantarctic. Significant biostratigraphic zones (1–5) are delineated. See Supplementary Note 5 for documentation of taxa.

Weak winds and possible seabirds: 11–10 cal ka BP

This initial lake phase records two important features: (1) a period of low wind-influence recorded by predominantly low-conductivity benthic diatoms and low concentrations of lithogenic elements, and (2) indicators of a possible seabird colony within the catchment.

The dominant diatom taxa at this time are freshwater benthic species, e.g. Pinnularia acidicola, Psammothidium germainii, and Platessa oblongellum associated with lower water levels and submerged aquatic macrophytes (Fig. 340). Total carbon (C%) is high (Fig. 4c), as are possible seabird colony (guano) indicators (e.g. P, Cd, Se, and Sr) (Fig. 4a)41,42; see Supplementary Note 4. Lithogenic markers of wind- and precipitation-based erosion are low (Fig. 4d, e). TEX86-based reconstructed lake water temperatures are at their highest, reflecting somewhat higher than present adjacent ocean SSTs as seen in the Southeast Pacific and the Antarctic Peninsula20,43 (Fig. 4b; see Supplementary Note 6). Together, these parameters suggest a productive, possibly rookery-proximal lake that is receiving relatively low sea-spray inputs from the SHW, both in terms of aerosols and precipitation. The core of the SHW was not centered on the Hornos Is. region at this time.

a Cd content in the sediment suggesting the presence of seabirds in the catchment; (b) the TEX86-based lake water temperature reconstruction (the shaded blue band shows modern air temperature variability); (c) Total carbon (%); the combined lithogenic elements (d) ICP-derived geochemical data PCA 1 axis scores and (e) magnetic susceptibility) and (f) salinity-tolerant planktonic diatom indicator taxa. The arrow marks the direction in which these proxies are used to infer increased strength of the SHW at this site. The red shaded bar represents the period of highest inferred winds at Hornos Is.

Maximum (higher than present) SHW: 10–7.5 cal ka BP

A transition to strong SHW influence occurs at ~10 cal ka BP (9.75 cal ka BP). Wind indicators increase markedly which is shown most clearly in the threshold-type shift from freshwater to saline diatom species Stephanocyclus aff. meneghiniana and Thalassiosira patagonica (Figs. 3, 4f). Both are associated with high conductivity lake environments, especially T. patagonica, which has populations in present day Patagonian lakes with conductivities >3 mS cm −1 (see supplementary Note 5)44. Lithogenic erosional inputs (e.g. PCA1, magnetic susceptibility, Ca, K, etc.) increase as well, and proportions of sedimentary carbon decrease due to the loss of benthic productivity and the possible loss of the seabird colony (Fig. 4c–e). At the same time, the diatoms also show a shift to deeper water with the dominance of open water planktonic saline diatom taxa over benthic macrophyte-associated freshwater forms, reflecting the increase in both sea salt aerosols and precipitation associated with the SHW at this site. Lake water temperature cooling likely reflects the influence of regional SST cooling (See Supplementary Note 6) given the lake’s proximity to the coast, the modulating effect of the wind, and enhanced advective cooling of the lake. These extreme wind conditions are unique in the context of the last 11,000 years and show stronger SHW at this site than the present.

Stable Holocene SHW: 7.5–0 cal ka BP

The shift to a Discostella sp.-dominated water column ( ~ 80% of the diatom population) marks the switch to the more stable lake environment that carries through to the present. Over the last 7.5 cal ka BP, the diatoms slowly transition to more benthic taxa, with higher proportions of Fragilaria s.l. forms in the last 3500 years (e.g. Staurosirella pinnata, Stauroforma exiguiformis; Fig. 3, diatom Zone 5). Magnetic susceptibility declines over this period, as do most lithogenic elements, likely reflecting a decrease in catchment erosion, whereas carbon increases (Fig. 4c, d, e). Lake water temperatures increase steadily over this period reflecting a rise in adjacent SSTs, likely amplified by local and in-lake factors (Fig. 4b). Together, these proxies suggest a gradual weakening of SHW/Antarctic influence at this site over the late Holocene and/or a long term stabilization of the catchment from the Early Holocene.

Regional changes to SHW over the Holocene

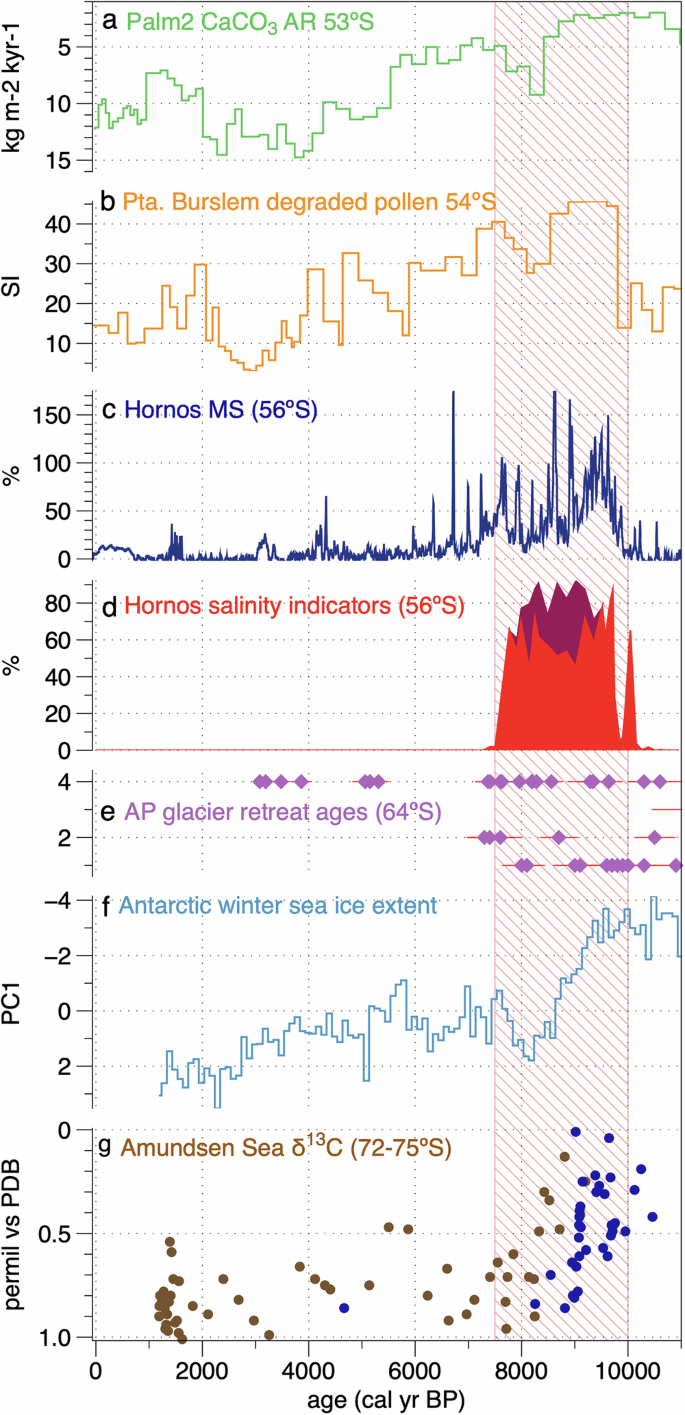

The 11 cal ka BP salt-spray record from IHL presented here provides a critical link between the Antarctic Peninsula and southern South America and helps establish an emerging picture of past westerlies the high southern latitudes (Fig. 5). Records from nearby Punta Arenas, Navarino Is. and Isla de los Estados confirm the pattern shown from Hornos Is (see Fig. 6 for locations). In both records from Punta Arenas and Isla Navarino, post-glacial Nothofagus woodlands were established 12.2 cal ka BP, and a wet climate until 9.7 cal ka BP. Degraded pollen grains and charcoal attest to an invigoration of the SHW with an intensely dry, windier phase beginning 9.7 until 7 cal ka BP (Fig. 5b)17,18,19. On Isla de los Estados to the NE of Hornos and in the lee of the Andes, conditions were dry from 10.6–8.5 cal ka BP, after which higher precipitation and surface runoff became established44. During this Early Holocene period ( ~ 10-8 cal ka BP), records from southernmost South America together show a pattern of high precipitation and wind on the windward side of the Andes, e.g. at Hornos Is. and windy/dry conditions on the leeward and foehn-influenced side of the Andes (e.g. Punta Arenas, Navarino Is., Is. de los Estados), consistent with the present-day spatial correlations between wind and precipitation (Fig. 6).

Summary diagram showing the relationship between different wind proxies over the Holocene on a transect from 51°S to 75°S showing the northward migration of the westerlies over this period. a Palm2 CaCO3 accumulation rate (reversed axis) showing the decline in marine productivity associated with Early Holocene (EH) stronger SHW in the Chilean inner fjords at 53°S20; (b) pollen preservation from Pta. Burslem on Navarino Is showing wind-associated pollen degradation during the EH18, (c–d) the magnetic susceptibility and salinity-associated diatom percentages (% Thalassiosira patagonica (dark red) and % Stephanocyclus aff. meneghiniana (lighter red) from our study on Hornos Is. (56°S) showing maximum winds during the EH, (e) Antarctic Peninsula glacier melt as a result of southward intensified SHW during the EH51; (f) Antarctic winter sea ice extent (Ross and Weddell Seas) minima in the EH measured from ice core sea salt (note reversed axis)58; g) δ13C of foraminifera documenting the incursion of warmer waters into the Amundsen Sea Embayment as a result of more southerly SHW during the EH (note reversed axis, colours are the different cores)57.The shaded bar marks the maximum Holocene winds at Hornos Is. (56°S).

ERA5 annual (J-D) correlation between Hornos Is. surface zonal winds (U10) and precipitation in the Southern Ocean and Patagonia between 1961-2021. Note the strong positive spatial correlation between wind at our sites and precipitation on the western flank of the Andes including sites GC2, Palm2, TML1 and TM1 from ref. 20 as well as the Antarctic Peninsula. Less positive correlations exist further north and inland at sites L. Cipreses and L. Pintito22,45. Correlations become negative on the leeward side of the Andes at L. Cardiel27 and even at nearby Punta Arenas19 and Navarino Is. including Pta Burslem17,18, as well as Isla de los Estados63 and the Falkland Islands48. Shaded (open) circles represent sites with higher (lower) winds in the Early Holocene, shaded (open) squares represent higher (lower) precipitation at those sites in the Early Holocene. Dashed lines for the AP represent insufficient precipitation data. Note that Cardiel received easterly-, not westerly-derived precipitation in the Early Holocene27. Plot from KNMI Explorer68.

Further north along the Andean cordillera, the SHW reconstructions become more complicated. Coastal fjord sediment and bog records from the windward side of the Andes ~53°S all show maximum SHW-borne precipitation in the early Holocene between 12.5 and 8.5 cal ka BP, with lesser wind conditions thereafter until 5.5 cal ka BP, and reduced SHW in the late Holocene (Fig. 5a)20. These results are largely consistent with the record presented here. On the leeward and foehn-influenced side of the Andes, records show opposite precipitation regimes, with an early Holocene warm and dry period marked by an increase in non-arboreal pollen between 10.5 and 7.5 ka cal BP at Lago Cipreses (51°S)45. Other regional records (e.g. Lago Pintito) with similar placement along the eastern spine of the Andes show increases in non-arboreal pollen, higher frequencies of charcoal resulting from forest fires, and macrophyte and algal changes indicative of lowered water levels between 11.5–7.5 cal ka BP22. Together they show dramatically reduced effective precipitation during this time and provide evidence for a so-called Early Holocene westerly minimum, a period of reduced SHW intensity, consistent across Southern Hemisphere mid-latitudes (reviewed in ref. 22). These records agree with other Patagonian records (reviewed in refs. 16,46). Temporally coherent records of early Holocene drying/SHW reduction/lake desiccation are also present from the Pacific sector islands of the Southern Ocean such as Macquarie36 and Campbell47 as well as in the Atlantic sector, e.g. Falkland Islands48. Southward displaced westerlies are also documented in the Early Holocene on Kerguelen Island, with warming and the long-range deposition of African pollen49. At the northern margin of the present-day SHW core belt, Early Holocene records from Lakes Cardiel (49°S) and Espejo (43°S) show an increase in Easterly-borne Atlantic precipitation from the southwards displaced SHW during this time27,50.

Towards Antarctica, paleoclimate records indicate both strong warmth and SHW during the early Holocene in the Antarctic Peninsula (AP), the Amundsen Sea and continental ice core records (Fig. 5e–g). Glaciers in the northern AP receded markedly between >11–8 cal ka BP likely resulting from warming related to a southward displacement of the SHW51. Marine records from the western AP suggest maximum water temperatures and minimum sea ice during the early Holocene (12-7 cal ka BP) are tied to the poleward displacement and intensification of the SHW43,52. These echo the maximum air temperatures reconstructed from James Ross Island ice core from c.12.5 – 9.2 cal ka BP and other ice core sites over the same period53,54, as well as warmer Southern Ocean SSTs55,56. Further to the south, marine sediments also document southward-displaced SHW which forced the incursion of warm water into the Amundsen Sea Embayment during the early Holocene57. Ice cores record winter sea ice minima during this time58. Together these records show a strong and poleward displacement of the SHW during the early Holocene, which is consistent with model results showing SHW intensification and southward migration during globally warmer periods, such as the Early Holocene Thermal Maximum, the 21st C, and future warming scenarios59,60,61,62.

Most records along broad latitudinal and longitudinal bands show a shift to more or less modern conditions beginning ~8–7 cal ka BP, and a slow migration of SHW northwards through the late Holocene. This is consistent with records in the Antarctic51,52, in southernmost Patagonia18,19,63, in Andean records27,50,64 and also further afield in the Falkland Islands48,65 South Georgia66,67, Macquarie Island36, Kerguelen Islands49. This is also consistent with Hornos Is., where the lake reaches relatively more stable conditions at 7.5 cal ka BP.

Present trends as analogue for past SHW migration

Understanding current trends in SHW in the mid- to high- southern latitudes gives us insight into possible analogues for past SHW behaviour on millennial timescales. Over the satellite observation period, wind, precipitation and temperature have all increased in the vicinity of Hornos Is. (ERA5 reanalysis data68), consistent with positive SAM phasing34. The recent poleward migration and intensification of the SHW are well documented in instrumental and satellite records across the mid-latitudes of the Southern Ocean in response to stratospheric ozone depletion and 20th and 21st Century climate warming35,69. For Patagonia (as well as other southern continental regions) this poleward intensification has resulted in increased fire activity and drought in the last several decades3,6. For Antarctica, this has resulted in higher air temperatures along the Antarctic Peninsula70 and the destabilization of ice shelves as warmer waters are forced onto the continental shelf8,10.

Reanalysis data (ERA568) also demonstrate these spatial patterns, where current wind trends (U10, 1990-2020) at Hornos Is. are strongly correlated with precipitation up along the western flank of the Andes >50°S and around the Antarctic Peninsula and Weddell Sea, but also with drought and/or reduced precipitation on the leeward/foehn side of the Cordillera including adjacent Tierra del Fuego, Navarino Is., Isla de los Estados as well as the Falkland Islands (Fig. 6). Increased winds at Cape Horn are also correlated with higher temperatures along the Antarctic Peninsula (ERA568). This spatial pattern matches records from the Early Holocene, where maximum winds at Hornos Is. are coincident with records of reduced precipitation/enhanced foehn winds in Tierra del Fuego, Navarino, and Isla de los Estados63, but also with higher than normal precipitation along the western flank of the Andes >52°S20 and warmth in the Antarctic Peninsula43,51,54. However, the higher-than-present wind conditions at Hornos Is. and unprecedented warmth/SHW in the Antarctic in the Early Holocene (10–7.5 cal ka BP) also suggest that the core of the wind belt was likely sitting further to the south than its current SAM-positive 21st C location.

Refining SHW behaviour

The seeming discrepancy between the Early Holocene period of lowest SHW recorded in Patagonia <53°S and across the Pacific sector of the Southern Ocean (e.g. Macquarie Is., Campbell Is.) and, conversely, the highest winds recorded from Hornos Is. and the Andean paleoclimate archives >53°S, allows us an opportunity to help refine our understanding of the behaviour of the westerlies during the Holocene. Rather than a change in intensity during the Early Holocene as proposed by Moreno et al.22, we demonstrate here the meridional displacement of the winds out of their normal mid-latitudinal bands deeper into the Drake Passage and towards the Antarctic in response to the early Holocene warming. This would have led to the appearance of “missing winds” across mid-latitude bands during this time seen in many records22. Also, rather than a pattern that mirrors the current seasonal contraction and expansion of the winds over millennial timescales20 we find that the maximum southern extent and intensity of Early Holocene winds are unique for the last 11,000 years, implying a greater range of latitudinal variability than currently captured by SHW movement. These conclusions confirm the southward displacement of the SHW in the Early Holocene >55°S hypothesized by Quade and Kaplan27 and by climate observations and high-resolution studies of wind response of the past millennium37. They are also in keeping with paleoceanographic data and model simulations which reveal ~5° N-S shifts in the mean latitude of the winds over the last glacial-interglacial transition29 and with modelling studies of past and future SHW dynamics61.

Implications of future warming and SHW migration

Our findings here show that the SHW were at their maximum southern extent in the Early Holocene, with a greater southward/poleward intensification and displacement than today, even despite the increasingly SAM-positive conditions of the last several decades. Future warming is expected to exacerbate current SHW and SAM trends, with further poleward migration of the SHW resulting from mid-latitude warming despite initial (in the next decades) stratospheric ozone recovery61,62,71,72. High emission models currently anticipate a significant poleward shift of the SHW (0.8–1.5°S/100 yrs) as well as an intensification ( ~ 0.8 m/s) by the end of the 21st C, with the largest amplitude changes centered around the East Pacific Margin and the Drake Passage (CMIP5/CMIP671,72). The Early Holocene SHW record from Hornos Is. offers an analogue for plausible near-future scenarios, where SHW are more intense and poleward than present, and possibly more than future high emission models predict. These future trends will magnify changes already underway in the Southern Ocean and Antarctic including, but not limited to, higher-than-average sea and air temperatures, ecosystem disruption, glacier melt, ice shelf and ice sheet instability, changes to ocean circulation and uptake of atmospheric heat and CO2, as well as drought and wildfires in the southern continental regions (e.g. Patagonia, South Africa, Australia).

Conclusions

The wind-derived sea spray record from Hornos Is. gives us a rare and strategic insight into the Holocene dynamics of the SHW at the western entrance of the Drake Passage. Without the complications of Patagonian orography, or vegetation- and catchment-mediated responses to wind strength, we can more clearly define the relative location of the SHW throughout this critical time. When taken together, the records of SHW minima in the Early Holocene from the mid-latitudes, our IHL record presented here, and the records from elsewhere in the Southern Ocean and around the Antarctic Peninsula and Amundsen Sea, argue strongly in favour of migratory westerlies, which were located further south during the Early Holocene in response to peak warmth, returning to near their current position 8–7.5 cal ka BP. This SHW migration and the “tipping point”-type environmental responses to it portend large and sudden shifts in the southern high latitudes in the coming decades in the absence of, or in spite of, substantive global action on greenhouse gas emissions.

Methods and materials

Coring

Sediment cores were taken in March 2016 from the deepest part of Isla Hornos Lake (IHL; Zmax = 10.7 m) from a floating platform using both piston and gravity corers to create a composite core length of 4.13 m73. Cores were packed onboard the Polarstern and brought back to Germany. At the Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research the cores were split lengthwise, photographed and scanned for μXRF and magnetic susceptibility. Later, the working halves were subsampled at 1.0 cm intervals for diatoms and other analyses.

Dating

We dated 24 samples using multiple fractions from the sediments of IHL. These include humin and humic acids from the bulk sediment and one paired wood macrofossil sample. A composite age depth model of both cores was generated using Bayesian statistical software Bacon 2.274 in R version 4.2.375. See Supplementary Note 2 for 14C information.

Diatoms as a past salt spray proxy

We used a diatom-based sea salt aerosol proxy methodology employed at other subantarctic sites (e.g. Macquarie Island36,76, Marion Island37) to track changes in relative wind strength at this location (See Supplementary Note 3). Diatoms were prepped from freeze dried sediments77, where samples were oxidized with 30% hydrogen peroxide, repeatedly rinsed and diluted aliquots were left to dry on plain glass coverslips. Dried smear slides were permanently mounted using Naphrax mounting medium and at least 400 valves were counted per slide at 100x under oil immersion and DIC optics. Difficult taxonomic attributions were made using a JEOL JSM-6610LV scanning electron microscope.

Diatoms were identified to species level where possible, using reference literature40 as well as by consultation and reference material from other subantarctic and Patagonian diatom papers44,78. However, several species encountered at Hornos Is. were hitherto unknown. These include Discostella sp. 1 and as well as Surirella sp.1 here (see Supplementary Note 5 for plates).

Downcore changes were separated into zones using constrained hierarchical cluster analysis in R using the broken stick model79 to find significant biostratigraphic zones.

CNS

Bulk sediment TC, TN and TS were measured at the IOW, Germany, with a EA1110 CHN (CE instruments) elemental analyser. The analytical precision was better than 1%.

Inorganic geochemistry

Inorganic geochemical data for the cores were generated through 2 methods: (1) semi-quantitative and high-resolution XRF scanning (see Supplementary Note 4); and (2) lower resolution, and fully quantitative ICP MS/OES analysis presented here.

ICP MS/OES

After freeze-drying, the sediment samples were homogenized with an agate ball mill. About 50 mg of the ground material was digested in closed Teflon vessels at 180 °C for 12 h using a HNO3-HF-HClO4 mixture. After evaporation of the acids to near-dryness, the digestions were fumed off 3 times with 6 M HCl and finally filled up with 2 vol% HNO3 to 50 mL. The concentrations of major elements (Ti, Al, Fe, Mg, Ca, Na, K, P and S) in the acid digestions were determined by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES, iCAP 7400 Duo, Thermo Fisher Scientific) using external calibration and Sc (2 ppm) as internal standard. Following automated online dilution (5-fold) of the digestions and addition of the internal standards Be, Rh and Ir by a PrepFAST system (Elemental Scientific), the trace metal (As, Ba, Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Mn, Mo, Ni, Rb, Sc, Se, Sr, Th, U, V, Zn and REEs) concentrations were measured by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, iCAP Q, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in KED mode using He as collision gas (except for Se measured with a He/8% H2 mixture), which efficiently reduced potential polyatomic interferences. Precision and trueness of the ICP measurements were checked with the international reference material SGR-1b (USGS) and were better than 6.1% and -8.6% for major and 2.7% and 7.6% for trace elements, respectively. ICP data were log-transformed and centered prior to PCA analysis on C2 software80.

Magnetic susceptibility

High-resolution magnetic susceptibility data was accomplished using a Bartington MS2E/1 spot-reading sensor integrated into an automatic logging system. The cleaned and foil-covered archive half of the split core was measured in steps of 1 mm with determination of the sensor’s drift every 10 mm by air-readings. A subsequent 3-point moving average takes into account the response function of the sensor with half-width of slightly less than 4 mm.

TEX86

The method for glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraether (GDGT) lipid extraction and separation has been previously described in ref. 81. Briefly, lipids were extracted from freeze-dried and homogenized sediments with a mixture of dichloromethane and methanol (DCM/MeOH 9:1, v:v) using an accelerated solvent extraction device (Thermo Scientific™ Dionex™ ASE™ 350). After adding a C46 GDGT as internal standard for quantification, the polar fraction containing GDGTs was isolated by microscale flash column chromatography using silica gel as solid stationary phase and a DCM/MeOH (1:1, v:v) mixture as eluent. The fraction was then filtered through a 0.45 μm polytetrafluorethylene filter. GDGTs were analysed by high performance liquid chromatography atmospheric pressure chemical ionization mass spectrometry (HPLC APCI-MS; Thermo Scientific™) as described in ref. 81 except for a small modification. The separation of the individual GDGTs was achieved on two UHPLC silica columns (BEH HILIC, 2.1 mm × 150 mm, 1.7 μm; Waters™) in series, fitted with a pre-column of the same material (Waters™), and maintained at 30 °C82. Using a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min, the gradient of the mobile phase was first held isocratic for 25 min with 18% solvent B (n-hexane:isopropanol, 9:1, v:v) and 82% solvent A (n-hexane), followed by a linear gradient to 35% solvent B in 25 min, followed by a linear gradient to 100% solvent B in 30 min. The GDGTs were identified by single-ion monitoring (SIM). TEX86 was defined as in Schouten et al.83. The global lake calibration with error bars of ±3.7 °C was used to convert TEX86 values into mean annual lake surface temperature estimates84. The repeatability of the method was estimated to 0.008, or 0.4 °C.

Responses